SUMMARY

Background

Individuals with end-stage renal disease (ESRD) manifest a chronic inflammatory state. Serum albumin, C-reactive protein (CRP), interleukin-6 (IL-6) and serum amyloid A (SAA) have been associated with mortality in ESRD, although reports vary as to whether they are true independent markers of mortality. We undertook a prospective study to determine whether these markers could predict mortality in ESRD.

Methods

A cohort of individuals on haemodialysis was followed prospectively for a mean of 2.1 years. Albumin, CRP, IL-6 and SAA were drawn at enrolment. Association between mortality and serum markers was assessed using Cox proportional hazards regression. A trend analysis was undertaken to establish the functional form of the association between serum markers and outcome.

Results

After multivariable adjustment, IL-6 was most strongly associated with mortality, followed closely by albumin (P = 0.0002 and P = 0.0005, respectively). CRP was marginally associated with mortality (P = 0.046), and SAA was not independently associated with mortality. In the final model adjusting for the effects of both IL-6 and albumin simultaneously, both markers remained associated with mortality (P = 0.003 and P = 0.011).

Conclusion

IL-6 had the strongest independent association with mortality, followed closely by albumin. CRP and SAA were not associated with mortality when measured at single time points. Increasing levels of IL-6 and decreasing levels of albumin were associated with increased mortality. IL-6 and albumin may be capturing different aspects of the inflammatory burden observed in haemodialysis patients.

Keywords: albumin, CRP, dialysis, IL-6, mortality, serum amyloid A

Inflammation is a cardinal pathophysiologic phenomenon associated with renal failure.1 Individuals with end-stage renal disease (ESRD) on chronic outpatient haemodialysis (HD) have elevated serum indices of inflammation such as C-reactive protein (CRP),2–7 interleukin-6 (IL-6),7–9 serum amyloid A (SAA)4 and tumour necrosis factor-α.10 Inflammatory stimuli such as the dialysis treatment itself,11,12 overt or subclinical infection such as in malfunctioning HD accesses,13 and uraemia itself, as demonstrated in individuals with varying degrees of renal insufficiency,14,15 are the factors that most likely contribute to the inflammatory milieu in HD patients.

Inflammation, formerly considered an ‘emerging’ risk factor for cardiovascular disease (CVD), is now fully appreciated as a deleterious process in the development of CVD.16,17 Inflammation is associated with all-cause mortality in both the HD and general populations. However, it has been difficult to determine the significance of inflammatory markers in ESRD because of the potential confounding related to malnutrition in this population. Hypoalbuminemia, a key index of malnutrition in HD patients, has been associated with increased mortality in ESRD,5,18,19 which initially led to the hypothesis that poor nutritional status was responsible for the high observed mortality rates. However, albumin is an acute-phase reactant that decreases in the face of inflammatory stimuli, and subsequent investigations have demonstrated that inflammation and malnutrition are linked processes.2,15

C-reactive protein has been widely studied, and CRP levels have been demonstrated to predict hypoalbuminemia.20 While the association of albumin with mortality has been reported to be accounted for by elevated CRP levels in many studies,5,7,21–23 others have concluded that, taken independently, CRP adds little to albumin in prediction models for mortality.17,24 A few studies have even failed to demonstrate an association of CRP with mortality.25,26 Complicating attempts to draw definitive conclusions from the literature is the fact that studies before 2001 did not utilize the now-standard high-sensitivity (hs) CRP assay. Additionally, in most studies examining the relationship of CRP (and other inflammatory markers) with mortality, the racial composition of study subjects was either not specified or appeared to be relatively homogenous.

Interleukin-6, a major cytokine regulator of malnutrition in ESRD,9,27 has also been examined in several studies for its association with mortality. Blood levels of IL-6 are elevated in many individuals on HD,28 and IL-6 has been proposed to contribute to alterations in acute-phase reactants,29 such as albumin, in response to inflammatory stimuli. While IL-6 has been demonstrated to predict mortality in HD patients in several studies,7,17,24,26,30–32 in at least two studies no association was found.23,33

Serum amyloid A is another inflammatory cytokine with potential associations with mortality in HD patients. SAA, produced in the liver, is a member of the family of acute-phase proteins which includes CRP and other less widely recognized proteins (e.g. α1 acid-glycoprotein).34 There appears to be only a single report of SAA levels in HD patients, in which SAA levels was an independent predictor of inflammatory status.35

Because reports differ concerning the association between mortality and inflammatory markers such as IL-6 and CRP, and because SAA has rarely been specifically examined in this context, we designed a prospective study in HD patients. We sought to determine which inflammatory markers were associated with mortality, and whether any of them contributed substantially more to prediction models than readily available serum albumin measurements. Our goal was to design a parsimonious model predicting mortality, demonstrating the relative strength contributed by each marker to the model. A racially diverse cohort was established; blood samples for albumin, IL-6, hs-CRP and SAA were collected; and the cohort was followed prospectively for a mean of 2.1 (median, 2.5) years. Inflammatory markers were then analysed for their association with mortality. Finally, the functional forms of important associations were assessed in trend analyses to determine how changes in the levels of the serum markers affected the risk of mortality.

METHODS

Study subjects

Patients were enrolled from four dialysis units within the San Francisco Bay Area: the San Francisco Veterans Affairs Medical Center, San Francisco General Hospital, University of California San Francisco-Mount Zion Dialysis Unit, and Satellite Dialysis Center-Greenbrae. The cohort was assembled as part of a prospective longitudinal cohort study investigating the association of genetic polymorphisms in inflammatory genes and mortality in HD patients.36 All ESRD patients at each HD unit over age 18 who had been dialyzing for at least 2 months were solicited. Exclusion criteria were evidence of active inflammation or infection, discharge from the hospital within the previous 3 weeks, presence of malignancy and use of corticosteroids. Of all subjects solicited to enrol, 93% elected to do so. Initially, 251 subjects were enrolled; as some data were missing on a small number of subjects, 236 individuals comprised the analysis cohort. The protocol was approved by the Institutional Review Boards of all study sites; patients provided written informed consent.

For purposes of the analysis, a history of coronary artery disease was defined as documented history of myocardial infarction, positive cardiac catheterization or nuclear medicine imaging study, coronary artery bypass surgery, or percutaneous coronary intervention; a history of cerebrovascular disease by documentation of a stroke or transient ischaemic attack, positive carotid artery imaging study (e.g. carotid ultrasonography) or cerebral imaging consistent with a previous stroke (e.g. by computed tomography or magnetic resonance imaging studies); and a history of peripheral vascular disease by vascular bypass surgery, angioplasty, non-traumatic amputation or vascular imaging (e.g. arteriogram). The criteria for imaging or other procedures were purely clinical; providers ordered various diagnostic tests and procedures according to individual clinical practice patterns. No subject was screened for any disease or condition for the purposes of the study. A diagnosis of dyslipidemia was made if the patient was taking lipid-lowering medications or if this diagnosis was documented in the medical chart.

Serum marker analysis

Whole blood was collected for IL-6, albumin, hs-CRP and SAA by the dialysis unit nursing staff coincident with the subject’s routine monthly laboratory blood draws. These were collected pre-dialysis before the midweek HD session. Ten mL was collected in Vacutainer gel separator tubes, placed on ice, cold-centrifuged and promptly stored at −70°C. Samples for CRP testing were shipped on dry ice to ARUP Laboratories (Salt Lake City, UT, USA) for analysis. The lower limit of detection for hs-CRP was 0.1 mg/L. IL-6 measurements were performed at the University of Maryland at Baltimore Cytokine Laboratory (Baltimore, MD, USA); lower limit of detection was 0.7 pg/mL. SAA was measured at the University of North Carolina Chapel Hill School of Dentistry, using the Tridelta Limited ELISA assay (Maynooth, Ireland); the lower limit of detection was 5 µg/L. Albumin was measured by either the bromcresol green (n = 219) or purple (n = 32) method by the commercial laboratories utilized by the respective HD units, as part of routine monthly laboratory testing. Those measured bromcresol purple were corrected;37 the normal range was 3.5–5.0 g/dL.

Clinical follow up

Clinical information on the subjects was obtained by examination of hospital medical records and the records from the dialysis units. Hospitalizations, discharge diagnoses and procedures were surveyed quarterly by a review of the medical records and dialysis charts, as well as by direct communication with patients. Death certificates were consulted where appropriate. Any ambiguities in written or electronic records were resolved by direct communication with the patient’s nephrologist. One investigator (JBW) collected all follow-up data to eliminate interobserver variability in attribution of events. The investigator was blinded to the results of serum marker testing.

Statistical analysis

Descriptive statistics for all variables were calculated for all subjects. Values of IL-6 below the detectable limit were given a value of 0.35 pg/mL. Sample means, medians, standard deviations and ranges were used to summarize continuous variables; frequencies and percentages were used to summarize categorical variables. Kaplan–Meier curves were generated stratified by quartiles of serum markers, respectively. The log-rank test for trend among the quartiles is shown with the plots.38 Cox proportional hazards regression was used to analyse association of all-cause mortality with the measured variables of interest. The primary variables of interest were serum levels of IL-6, albumin, hs-CRP and SAA. A natural log transformation was done on CRP, IL-6 and SAA to adjust for the skewedness in their distributions. Other variables considered for the models included age, sex, race (African American, Asian, Caucasian and Hispanic), time on dialysis before enrolment, hypertension, diabetes mellitus, coronary artery disease, cerebrovascular disease, peripheral vascular disease, dyslipidemia, body mass index, smoking status (never smoker, previous smoker, current smoker), haemoglobin, haematocrit, calcium x phosphorous product and urea reduction ratio.

The base model was built by determining which variables (exclusive of the four serum markers of interest) were significantly associated with the outcome (P < 0.05) in a univariate Cox regression model. A best-subset variable selection method, based on the score statistic for the model, was used while forcing age, race and sex into all models. The variables remaining significant after this base model selection process were age, race (Hispanic vs other), coronary artery disease, cerebrovascular disease, dyslipidemia and current smoking status. Each of the four serum markers were then added to these base covariates to determine their respective strength of association with mortality, adjusted for the base covariates but unadjusted for the other three markers. Next, the four serum markers were jointly added to the base covariates to assess their respective strengths of association, adjusted for both the other three markers and the base covariates. Any marker which demonstrated no significant association with mortality was removed with backward elimination.

Proportional hazards assumptions were checked for categorical covariates using stratified Kaplan–Meier log-log survival plots, and, for continuous covariates, by breaking follow-up time into discrete periods and assessing trends in the parameter estimates for the covariate over time. Weighted Schoenfeld residuals and time-dependent effects were also examined to assess proportional hazards.

Functional form was checked for the continuous covariates by performing a trend analysis,39 and by examining martingale residuals and deviance residuals for model fit and outliers. Quadratic terms and other interactions between variables in the final model were tested.

Because of the skewed distribution of the serum markers’ distributions, Spearman rank correlation coefficients were used to generate a correlation matrix between serum markers. All analyses were performed using SAS version 9.1 (SAS Institute, Inc., Cary, NC, USA). The Kaplan–Meier plots were generated using R version 2.6.2. The α-level was set a priori at 0.05.

RESULTS

A total of 236 HD patients were studied. Characteristics of the study subjects are shown in Table 1. The subjects were a racially diverse group, typical of the population of northern California. Subjects were followed for a mean of 2.1 (range 0.2–3.2) years; the median was 2.5 years. Eighty-eight individuals (36%) expired during the course of the study; 49% of the deaths were cardiovascular.

Table 1.

Study subject characteristics (n = 236)

| All subjects | Expired | Did | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age, year† | 62.7 ± 4.3 | 69.7 ± 12.6 | 59.0 ± 13.7 |

| Gender | |||

| Male, n (%) | 147 (62) | 56 (68) | 91 (59) |

| Race/ethnicity, n (%) | |||

| African American (Non-Hispanic) | 79 (33) | 28 (34) | 51 (33) |

| Asian American | 66 (28) | 22 (27) | 44 (29) |

| Caucasian | 65 (28) | 31 (38) | 34 (22) |

| Hispanic | 26 (11) | 1 (1) | 25 (16) |

| Dialysis duration, year† (range, month) | 5.4 ± 3.8 (2–350) | 4.3 ± 3.0 | 6.0 ± 4.0 |

| Cause of renal failure, n (%) | |||

| Diabetic nephropathy | 96 (41) | 34 (41) | 62 (41) |

| Nephrosclerosis | 62 (26) | 24 (29) | 38 (25) |

| Glomerulonephritis | 32 (14) | 7 (9) | 25 (16) |

| Other | 29 (12) | 13 (16) | 16 (10) |

| Unknown | 16 (7) | 4 (5) | 12 (8) |

| Hypertension, n (%) | 214 (91) | 72 (88) | 142 (92) |

| Diabetes, n (%) | 123 (52) | 45 (55) | 78 (51) |

| Coronary artery disease, n (%) | 99 (42) | 43 (52) | 56 (36) |

| Cerebrovascular disease, n (%) | 73 (31) | 42 (51) | 31 (20) |

| Peripheral vascular disease, n (%) | 47 (20) | 23 (28) | 24 (16) |

| Dyslipidemia, n (%) | 81 (34) | 9 (11) | 8 (5) |

| Body mass index, kg/m2† | 26.3 ± 14.1 | 26.9 ± 22.0 | 26.0 ± 6.5 |

| Current smokers, n (%) | 26 (11) | 10 (12) | 14 (9) |

| Haemoglobin, mg/dL† | 11.6 ± 1.4 | 11.6 ± 1.2 | 11.6 ± 1.5 |

| Calcium × phosphorous product, mg2/dL2† | 51.4 ± 17.2 | 50.7 ± 17.3 | 51.8 ± 17.2 |

| Urea reduction ratio, %† | 69.6 ± 8.2 | 70.3 ± 6.5 | 69.2 ± 9.0 |

| Albumin, g/dL† | 3.8 ± 0.5 | 3.6 ± 0.5 | 3.8 ± 0.4 |

| IL-6, pg/mL† | 13.0 ± 17.5 | 17.9 ± 20.3 | 10.4 ± 15.2 |

| CRP, mg/L† | 10.7 ± 14.9 | 14.0 ± 19.7 | 9.0 ± 11.3 |

| SAA, mg/L† | 10.0 ± 11.5 | 12.2 ± 14.3 | 8.8 ± 9.5 |

Mean ± standard deviation.

CRP, C-reactive protein; IL-6, interleukin-6; SAA, serum amyloid A.

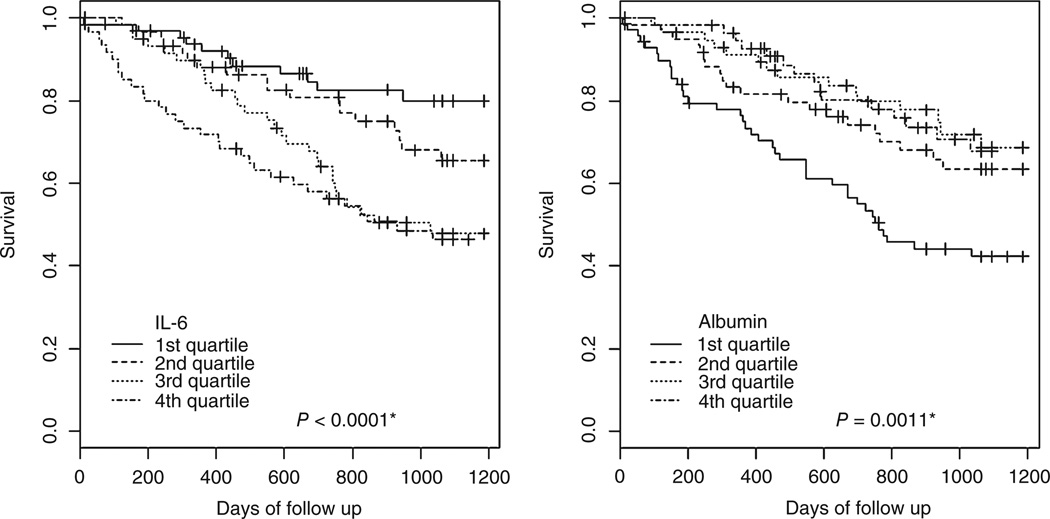

Cox regression modelling for mortality was undertaken. The results, in the form of successive models, are shown in Table 2. Age, race, coronary artery disease, cerebrovascular disease, dyslipidemia and current smoking status were independently associated with mortality (Model 1). Next, each serum marker (IL-6, albumin, CRP and SAA) was singly entered into the model. CRP was only marginally associated with mortality when entered into the base Model 1 (hazard ratio (HR) 1.212, 95% confidence intervals (CI) 1.003–1.464, P = 0.046). SAA was not associated with mortality when entered into the base Model 1 (HR 1.174, 95% CI 0.938–1.469, P = 0.161). IL-6 and albumin (inversely) were associated with mortality, as shown in Models 2 and 3, respectively. The final model, incorporating both IL-6 and albumin, is shown as Model 4. Both IL-6 and albumin retained significant associations with mortality in this final model (HR 1.411, P = 0.003 and HR 0.541, P = 0.011, respectively), with a one-unit increase of log IL-6 associated with a 41% increase in hazard of death, and a one-unit (linear) increase in albumin associated with a 46% decrease in hazard of death. The interaction between albumin and IL-6 was tested and found to be non-significant (P = 0.523). The log-rank test for trend from the Kaplan–Meier plot for IL-6 indicates an overall decreasing trend in survival by increasing quartile of IL-6 (P = 0.0001, Fig. 1). Analogously, the test for albumin indicated an increasing trend in survival for the higher quartile (P = 0.0011, Fig. 1).

Table 2.

Cox proportional hazard regression models predicting all-cause mortality

| Model 1 | Model 2 | Model 3 | Model 4 | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Variable | HR | P-value | HR | P-value | HR | P-value | HR | 95% CI | P-value |

| Age at enrolment† | 1.478 | 0.0002 | 1.375 | 0.0024 | 1.423 | 0.0012 | 1.349 | 1.211–1.502 | 0.0055 |

| Hispanic race | 0.090 | 0.0176 | 0.100 | 0.0232 | 0.090 | 0.0176 | 0.095 | 0.013–0.695 | 0.0204 |

| Cerebrovascular disease | 2.022 | 0.0029 | 2.116 | 0.0016 | 1.978 | 0.0043 | 2.067 | 1.294–3.303 | 0.0024 |

| Current smoker | 2.629 | 0.0066 | 2.065 | 0.0424 | 2.171 | 0.0310 | 1.869 | 0.924–3.780 | 0.0817 |

| Hyperlipidaemia | 2.105 | 0.0396 | 2.508 | 0.0115 | 2.990 | 0.0039 | 3.196 | 1.522–6.712 | 0.0021 |

| Coronary artery disease | 1.563 | 0.0488 | 1.516 | 0.0664 | 1.448 | 0.1032 | 1.457 | 0.934–2.271 | 0.0971 |

| IL-6, pg/mL‡ | – | – | 1.523 | 0.0002 | – | – | 1.411 | 1.124–1.771 | 0.0030 |

| Albumin, g/dL§ | – | – | – | – | 0.444 | 0.0005 | 0.541 | 0.336–0.870 | 0.0113 |

Model 1: Base model, excluding serum markers, employing demographic and clinical covariates associated with mortality; Model 2: Model ± plus log IL-6; Model 3: Model ± plus albumin; Model 4: Model ± with both IL-6 and albumin entered simultaneously. For simplicity, 95% confidence intervals (CI) are shown only for the final model.

Per 10 years.

Log-transformed with natural log (ln); HR is per one-unit log increase in IL-6.

HR is per one-unit increase of albumin in g/dL.

HR, hazard ratio; IL-6, interleukin-6.

Fig. 1.

Kaplan–Meier plots of survival by quartile of interleukin-6 (IL-6) and albumin. Asterisks denote log-rank test for trend.

A correlation matrix of the serum markers was generated using Spearman correlation coefficients (Table 3). Inflammatory markers were moderately (0.25–0.46) correlated with high significance (P < 0.0001), with the exception of SAA with albumin (although SAA was inversely correlated with albumin, as expected).

Table 3.

Spearman correlation matrix for IL-6, albumin, CRP and SAA

| IL-6 | Albumin | CRP | SAA | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| IL-6 | 1 | – | – | – |

| Albumin | −0.31 (P < 0.001)* | 1 | – | – |

| CRP | 0.44 (P < 0.001) | −0.23 (P < 0.001) | 1 | – |

| SAA | 0.41 (P < 0.001) | −0.11(P = 0.106) | 0.46 (P < 0.001) | 1 |

P-values are for tests of the null hypothesis of no correlation.

CRP, C-reactive protein; IL-6, interleukin-6; SAA, serum amyloid A.

DISCUSSION

In this study, we replicate and extend the findings of previous work, and contribute several new insights. First, as with several other studies,7,17,24,26,30–32 we found a strong independent association of IL-6 levels with mortality, further establishing IL-6 as a potent marker of inflammation. After examining a wide range of clinical and laboratory variables which have been suggested or demonstrated in other reports to be associated with inflammatory status and mortality, the ‘parent’ model, which included all variables with univariate mortality associations, was then repeatedly modified by entering IL-6, albumin, CRP and SAA levels individually into the model. This approach demonstrated that, among these four markers, only IL-6 (Model 2) and albumin (Model 3) were associated with mortality. The final model revealed that IL-6 had the strongest statistical association with mortality (slightly more so than albumin).

As noted in a review by Stenvinkel et al.,9 there are numerous reasons why IL-6 would demonstrate such a potent association. First, IL-6 functions primarily as an endocrine (as opposed to paracrine or autocrine) agent,40 and thus may have more disparate pro-inflammatory effects on the organism. Elevated IL-6 may be related to the uraemic state itself, both in CKD28,41,42 and dialysis43 patients. Numerous comorbidities present in HD patients, such as hypertension,44,45 CHF46 and the metabolic syndrome,44,47 are also associated with elevations in IL-6. Dialysis itself appears to contribute as well, giving rise to the hypothesis that exposure of blood to dialysis membranes is an inflammatory stimulus.48 The recent finding by Liu et al.49 that functional allelic variants in the IL-6 gene are associated with CVD in dialysis patients further supports this hypothesis.

We also sought to determine the contribution of other inflammatory markers to all-cause mortality. Given the importance that albumin has in predicting mortality,5,18,19 we considered it important to include albumin in the analysis. Conceptualization of the insights that albumin levels provide is challenging: inflammation and malnutrition are interlinked processes, the independent effects of which are difficult to separate. However, it is possible that contribution of albumin, (independent of other inflammatory mediators) to a model of mortality may, at least in part, represent the residual effects of malnutrition on mortality. In our model, albumin levels still contribute some information to a parsimonious model of all-cause mortality. Other authors have also noted preserved contributions of albumin after adjustment for IL-6,8,26 although this is not a universal finding.30 It is possible that analysis of other novel cytokines involved in inflammation would have eroded the independent effects of albumin in our cohort, but this is only speculative.

The role that CRP plays in independently predicting mortality is not fully understood. We did not note an independent effect of CRP on mortality. This finding is contrary to most,4,5,7,22–24 but not all3,26 studies. However, interpretation of reported associations of CRP with clinical outcomes may be complex. First, in several of these studies, CRP’s association with mortality was rather modest7,23 or in evidence only in a subset of the most inflamed subjects;24 it is important to consider the issue of multiple comparison testing in the settings of modest associations. Another possibility is that CRP measured at single time points may be an unreliable indicator of inflammatory status over a period of years. CRP fluctuates considerably in HD patients when examined longitudinally.22 In a study of individuals for whom there were three determinations of CRP over a 7 month period, 62% occupied different tertiles of serum CRP at different times during the observation period.2 It is reasonable to expect that, over a period of several years, there would be considerable variation of CRP within most individuals. Thus, the predictive ability of any single determination of CRP may have limited value, and this variability could be responsible for contradictory findings in the literature.

Another possible reason why IL-6 might be more strongly associated with mortality than CRP is that IL-6 is a more ‘proximal’ marker of inflammation, which is ‘upstream’ to CRP in the inflammatory cascade, and is a more constant and reliable indicator of an individual’s inflammatory status. IL-6 is known to promote synthesis of CRP29,50 and as such may be more fundamental to the processes of inflammation and cachexia in ESRD. IL-6 appears to have a direct effect on experimental cachexia,51 a phenomenon which can be inhibited experimentally by IL-6 blockade.52 Another possibility is that our subjects were in some way different from other study cohorts. This seems unlikely, however, because the median value for CRP in our subjects was 11.1 mg/L, in the middle of the range reported in three other studies (6.4, 7.5, 16.2).4,5,7

An additional contribution to the literature is that SAA was not associated with mortality in our cohort. To our knowledge, SAA has been examined prospectively for its association with mortality in another cohort. In a report from China, 158 HD patients were followed for a maximum of 36 months for mortality; SAA was not associated with mortality in multivariate modelling.53 Our results bolster these findings and extend them to a racially diverse Western HD population. The effects of SAA were also investigated by Tsirplanis et al.,35 who evaluated SAA as a measure of microinflammation (defined as elevated inflammatory cytokines in the absence of clinically evident). They noted wide intra-individual longitudinal variation in SAA levels in ostensibly ‘healthy’ dialysis patients, but their study was not designed to examine the effect of these markers on mortality. SAA was clearly the least potent (and a non-significant) contributor to the predictive power of our model, and was the least-correlated with albumin as demonstrated in the correlation matrix. SAA does not appear to be an important marker of mortality in dialysis patients based on our results.

We acknowledge several important limitations to our study. First, baseline clinical characteristics were not identified prospectively. For example, no subjects were deliberately screened for CVD, and no diagnostic tests were ordered outside of routine clinical practice. We identified comorbidities based on an extensive review of the medical record, meaning it is likely that some individuals had subclinical comorbidities that were missed. Second, all serum markers were obtained only once at the beginning of the study, and are unlikely to provide a true picture of inflammatory status over the entire study period, especially in the well-studied case of longitudinal CRP levels,22,54 but almost certainly in the case of other markers (e.g. IL-6) as well. Future studies should emphasize time-averaged values of serum markers. Another limitation is that we did include individuals irrespective of dialysis access. Our goal was to recruit a high percentage of eligible HD patients in an attempt to draw broad conclusions about prevalent patients dialyzing in our city across racial, geographic and socioeconomic strata; we were largely successful in this, recruiting fully 93% of eligible individuals. As such, we did not limit the study to individuals with well-functioning, primary arteriovenous (AV) fistulas, as would be completely ideal. Individuals with tunnelled dialysis lines, or even AV grafts, are likely to harbour a greater inflammatory burden than those with AV fistulas. One might limit inclusion only to those with AV fistulas, but this would have substantially limited our statistical power and attenuated our ability to draw ‘real-world’ conclusion about the patients dialyzing in our units. Many patients with AV fistulas may have required tunnelled catheters over the course of the study, and many with indwelling lines would have had more permanent accesses placed; this highlights the limitations of single-measurement determinations of serum inflammatory markers. The conclusions we propose must be considered within the confines of the experimental design and the aforementioned limitations. Finally, it is possible that other unexamined serum markers (e.g. tumour necrosis factor-α or fetuin A) might have captured the association between mortality and inflammatory status as well as, or better than, the markers we chose to examine. It is possible that ascertainment of other inflammatory marker levels would have altered our observed associations of albumin and IL-6 with mortality.

As is typical of the general population in our area, the dialysis population had substantial racial diversity; it is conceivable that different inflammatory phenomena occur in different races. This was also a strength of our study, however, as the racial diversity of our cohort permits greater generalizability of our findings. Finally, measurement error and other limitations of measurement may also have played a role, particularly in the case of IL-6. Individuals with levels below the detectable range (0.7 pg/mL), were assigned a value of 0.35 pg/mL, a common practice. We then recoded these individuals as having a level of 0.1 pg/mL, and found virtually no change to our final model (data not shown).

In conclusion, IL-6 has previously been cited as a strong marker for mortality in HD patients. Our findings further support the body of literature associating IL-6 with mortality in HD patients. Although IL-6 is more strongly associated with mortality than albumin, we demonstrate that serum albumin still contributes substantially relative to IL-6. Albumin levels may capture ‘residual’ effects of poor nutrition, which are not fully explained by IL-6, but the distinction between the nutritional and inflammatory components represented in serum albumin levels have yet to be fully elucidated. As such, our findings on albumin should be considered hypothesis-generating. The role of CRP, which may represent a ‘final common pathway’ of inflammation, remains somewhat more problematic, and its association with mortality may be more modest than commonly appreciated. There is no evidence as yet that SAA is independently associated with mortality.

While albumin remains a useful and clinically ‘intuitive’ marker of inflammatory status at the bedside, we believe that IL-6, by virtue of its strength of association with mortality, has additional clinical utility beyond that of albumin alone, and should be considered a candidate for broader clinical use. Although routine ascertainment of large numbers of inflammatory marker levels is probably clinically unwieldy and financially prohibitive, future research efforts should seek to determine whether perhaps one or two markers, in addition to albumin, might be suitable candidates for routine clinical application. Future research efforts should be directed at elucidating which markers might be particularly suited to this role, and whether any such markers are truly predictive of mortality in a prospective fashion.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

This study was supported by NIH grants DK 39776 (DHL), DK 56182 (KLJ), DK 07219 (JBW), UCSF Foundation Greenberg Awards #80357 and #60519 (DHL, KLJ), Amgen Grant #20010180 (AMH, DHL, KLJ) and National Kidney Foundation Fellow Grants (AMH, JBW). We thank Satellite Dialysis for assistance in patient recruitment.

REFERENCES

- 1.Stenvinkel P, Alvestrand A. Inflammation in end-stage renal disease: Sources, consequences, and therapy. Semin. Dial. 2002;15:329–337. doi: 10.1046/j.1525-139x.2002.00083.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kaysen GA, Chertow GM, Adhikarla R, Young B, Ronco C, Levin NW. Inflammation and dietary protein intake exert competing effects on serum albumin and creatinine in hemodialysis patients. Kidney. Int. 2001;60:333–340. doi: 10.1046/j.1523-1755.2001.00804.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Owen WF, Lowrie EG. C-reactive protein as an outcome predictor for maintenance hemodialysis patients. Kidney. Int. 1998;54:627–636. doi: 10.1046/j.1523-1755.1998.00032.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Zimmermann J, Herrlinger S, Pruy A, Metzger T, Wanner C. Inflammation enhances cardiovascular risk and mortality in hemodialysis patients. Kidney. Int. 1999;55:648–658. doi: 10.1046/j.1523-1755.1999.00273.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Yeun JY, Levine RA, Mantadilok V, Kaysen GA. C-reactive protein predicts all-cause and cardiovascular mortality in hemodialysis patients. Am. J. Kidney. Dis. 2000;35:469–476. doi: 10.1016/s0272-6386(00)70200-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Stenvinkel P. Inflammation in end-stage renal failure: Could it be treated? Nephrol. Dial. Transplant. 2002;17(Suppl 8):33–38. doi: 10.1093/ndt/17.suppl_8.33. discussion 40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Tripepi G, Mallamaci F, Zoccali C. Inflammation markers, adhesion molecules, and all-cause and cardiovascular mortality in patients with ESRD: Searching for the best risk marker by multivariate modeling. J. Am. Soc. Nephrol. 2005;16(Suppl 1):S83–S88. doi: 10.1681/asn.2004110972. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bologa RM, Levine DM, Parker TS, et al. Interleukin-6 predicts hypoalbuminemia, hypocholesterolemia, and mortality in hemodialysis patients. Am. J. Kidney. Dis. 1998;32:107–114. doi: 10.1053/ajkd.1998.v32.pm9669431. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Stenvinkel P, Barany P, Heimburger O, Pecoits-Filho R, Lindholm B. Mortality, malnutrition, and atherosclerosis in ESRD: What is the role of interleukin-6? Kidney. Int. Suppl. 2002;80:103–108. doi: 10.1046/j.1523-1755.61.s80.19.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kimmel PL, Phillips TM, Simmens SJ, et al. Immunologic function and survival in hemodialysis patients. Kidney. Int. 1998;54:236–244. doi: 10.1046/j.1523-1755.1998.00981.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Dinarello CA. Cytokines and biocompatibility. Blood. Purif. 1990;8:208–213. doi: 10.1159/000169968. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Memoli B, Postiglione L, Cianciaruso B, et al. Role of different dialysis membranes in the release of interleukin-6-soluble receptor in uremic patients. Kidney. Int. 2000;58:417–424. doi: 10.1046/j.1523-1755.2000.00181.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ayus JC, Sheikh-Hamad D. Silent infection in clotted hemodialysis access grafts. J. Am. Soc. Nephrol. 1998;9:1314–1317. doi: 10.1681/ASN.V971314. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Nakanishi I, Moutabarrik A, Okada N, et al. Interleukin-8 in chronic renal failure and dialysis patients. Nephrol. Dial. Transplant. 1994;9:1435–1442. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Stenvinkel P, Heimburger O, Paultre F, et al. Strong association between malnutrition, inflammation, and atherosclerosis in chronic renal failure. Kidney. Int. 1999;55:1899–1911. doi: 10.1046/j.1523-1755.1999.00422.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ross R. Atherosclerosis – An inflammatory disease. N. Engl. J. Med. 1999;340:115–126. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199901143400207. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Zoccali C, Mallamaci F, Tripepi G. Inflammatory proteins as predictors of cardiovascular disease in patients with end-stage renal disease. Nephrol. Dial. Transplant. 2004;19(Suppl 5):V67–V72. doi: 10.1093/ndt/gfh1059. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Owen WF, Jr, Lew NL, Liu Y, Lowrie EG, Lazarus JM. The urea reduction ratio and serum albumin concentration as predictors of mortality in patients undergoing hemodialysis. N. Engl. J. Med. 1993;329:1001–1006. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199309303291404. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kopple JD. Effect of nutrition on morbidity and mortality in maintenance dialysis patients. Am. J. Kidney. Dis. 1994;24:1002–1009. doi: 10.1016/s0272-6386(12)81075-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kaysen GA, Stevenson FT, Depner TA. Determinants of albumin concentration in hemodialysis patients. Am. J. Kidney. Dis. 1997;29:658–668. doi: 10.1016/s0272-6386(97)90117-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Racki S, Zaputovic L, Mavric Z, Vujicic B, Dvornik S. C-reactive protein is a strong predictor of mortality in hemodialysis patients. Ren. Fail. 2006;28:427–433. doi: 10.1080/08860220600683581. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Nascimento MM, Pecoits-Filho R, Qureshi AR, et al. The prognostic impact of fluctuating levels of C-reactive protein in Brazilian haemodialysis patients: A prospective study. Nephrol. Dial. Transplant. 2004;19:2803–2809. doi: 10.1093/ndt/gfh493. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kalantar-Zadeh K, Brennan ML, Hazen SL. Serum myeloperoxidase and mortality in maintenance hemodialysis patients. Am. J. Kidney. Dis. 2006;48:59–68. doi: 10.1053/j.ajkd.2006.03.047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Panichi V, Maggiore U, Taccola D, et al. Interleukin-6 is a stronger predictor of total and cardiovascular mortality than C-reactive protein in haemodialysis patients. Nephrol. Dial. Transplant. 2004;19:1154–1160. doi: 10.1093/ndt/gfh052. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Stenvinkel P, Wang K, Qureshi AR, et al. Low fetuin-A levels are associated with cardiovascular death: Impact of variations in the gene encoding fetuin. Kidney. Int. 2005;67:2383–2392. doi: 10.1111/j.1523-1755.2005.00345.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Honda H, Qureshi AR, Heimburger O, et al. Serum albumin, C-reactive protein, interleukin 6, and fetuin a as predictors of malnutrition, cardiovascular disease, and mortality in patients with ESRD. Am. J. Kidney. Dis. 2006;47:139–148. doi: 10.1053/j.ajkd.2005.09.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kaysen GA. Inflammation: Cause of vascular disease and malnutrition in dialysis patients. Semin. Nephrol. 2004;24:431–436. doi: 10.1016/j.semnephrol.2004.06.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Herbelin A, Urena P, Nguyen AT, Zingraff J, Descamps-Latscha B. Elevated circulating levels of Interleukin-6 in patients with chronic renal failure. Kidney. Int. 1991;39:954–960. doi: 10.1038/ki.1991.120. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Wang Y, Ripperger J, Fey GH, et al. Modulation of hepatic acute phase gene expression by epidermal growth factor and Src protein tyrosine kinases in murine and human hepatic cells. Hepatology. 1999;30:682–697. doi: 10.1002/hep.510300318. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Rao M, Guo D, Perianayagam MC, et al. Plasma Interleukin-6 predicts cardiovascular mortality in hemodialysis patients. Am. J. Kidney. Dis. 2005;45:324–333. doi: 10.1053/j.ajkd.2004.09.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Pecoits-Filho R, Barany P, Lindholm B, Heimburger O, Stenvinkel P. Interleukin-6 is an independent predictor of mortality in patients starting dialysis treatment. Nephrol. Dial. Transplant. 2002;17:1684–1688. doi: 10.1093/ndt/17.9.1684. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kimmel PL, Chawla LS, Amarasinghe A, et al. Anthropometric measures, cytokines and survival in haemodialysis patients. Nephrol. Dial. Transplant. 2003;18:326–332. doi: 10.1093/ndt/18.2.326. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Chauveau P, Level C, Lasseur C, et al. C-reactive protein and procalcitonin as markers of mortality in hemodialysis patients: A 2-year prospective study. J. Ren. Nutr. 2003;13:137–143. doi: 10.1053/jren.2003.50017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Ceciliani F, Giordano A, Spagnolo V. The systemic reaction during inflammation: The acute-phase proteins. Protein. Pept. Lett. 2002;9:211–223. doi: 10.2174/0929866023408779. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Tsirpanlis G, Bagos P, Ioannou D, et al. The variability and accurate assessment of microinflammation in haemodialysis patients. Nephrol. Dial. Transplant. 2004;19:150–157. doi: 10.1093/ndt/gfg486. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Wetmore JB, Hung AM, Lovett DH, Sen S, Quershy O, Johansen KL. Interleukin-1 gene cluster polymorphisms predict risk of ESRD. Kidney. Int. 2005;68:278–284. doi: 10.1111/j.1523-1755.2005.00403.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.McGinlay JM, Payne RB. Serum albumin by dye-binding: Bromocresol green or bromocresol purple? The case for conservatism. Ann. Clin. Biochem. 1988;25(Pt 4):417–421. doi: 10.1177/000456328802500417. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Klein JP, Moeschberger ML. Survival Analysis: Techniques for Censored and Truncated Data. 2nd edn. New York: Springer Sciences+Business Media; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Rothman KJ, Greenland S. Modern Epidemiology. 2nd edn. Philadelphia, PA: Lippincott-Raven; 1998. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Yudkin JS, Kumari M, Humphries SE, Mohamed-Ali V. Inflammation, obesity, stress and coronary heart disease: Is Interleukin-6 the link? Atherosclerosis. 2000;148:209–214. doi: 10.1016/s0021-9150(99)00463-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Cavaillon JM, Poignet JL, Fitting C, Delons S. Serum Interleukin-6 in long-term hemodialyzed patients. Nephron. 1992;60:307–313. doi: 10.1159/000186770. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Panichi V, Migliori M, De Pietro S, et al. C reactive protein in patients with chronic renal diseases. Ren. Fail. 2001;23:551–562. doi: 10.1081/jdi-100104737. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Pereira BJ, Shapiro L, King AJ, Falagas ME, Strom JA, Dinarello CA. Plasma levels of IL-1 beta, TNF alpha and their specific inhibitors in undialyzed chronic renal failure, CAPD and hemodialysis patients. Kidney. Int. 1994;45:890–896. doi: 10.1038/ki.1994.117. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Fernandez-Real JM, Vayreda M, Richart C, et al. Circulating interleukin-6 levels, blood pressure, and insulin sensitivity in apparently healthy men and women. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 2001;86:1154–1159. doi: 10.1210/jcem.86.3.7305. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Chae CU, Lee RT, Rifai N, Ridker PM. Blood pressure and inflammation in apparently healthy men. Hypertension. 2001;38:399–403. doi: 10.1161/01.hyp.38.3.399. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Anker SD, Ponikowski P, Varney S, et al. Wasting as independent risk factor for mortality in chronic heart failure. Lancet. 1997;349:1050–1053. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(96)07015-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Mohamed-Ali V, Goodrick S, Rawesh A, et al. Subcutaneous adipose tissue releases Interleukin-6, but not tumor necrosis factor-alpha, in vivo. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 1997;82:4196–4200. doi: 10.1210/jcem.82.12.4450. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Takahashi T, Kubota M, Nakamura T, Ebihara I, Koide H. Interleukin-6 gene expression in peripheral blood mononuclear cells from patients undergoing hemodialysis or continuous ambulatory peritoneal dialysis. Ren. Fail. 2000;22:345–354. doi: 10.1081/jdi-100100878. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Liu Y, Berthier-Schaad Y, Fallin MD, et al. IL-6 haplotypes, inflammation, and risk for cardiovascular disease in a multiethnic dialysis cohort. J. Am. Soc. Nephrol. 2006;17:863–870. doi: 10.1681/ASN.2005050465. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Heinrich PC, Castell JV, Andus T. Interleukin-6 and the acute phase response. Biochem. J. 1990;265:621–636. doi: 10.1042/bj2650621. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Strassmann G, Fong M, Kenney JS, Jacob CO. Evidence for the involvement of interleukin 6 in experimental cancer cachexia. J. Clin. Invest. 1992;89:1681–1684. doi: 10.1172/JCI115767. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Tsujinaka T, Fujita J, Ebisui C, et al. Interleukin 6 receptor antibody inhibits muscle atrophy and modulates proteolytic systems in interleukin 6 transgenic mice. J. Clin. Invest. 1996;97:244–249. doi: 10.1172/JCI118398. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Hung CY, Chen YA, Chou CC, Yang CS. Nutritional and inflammatory markers in the prediction of mortality in Chinese hemodialysis patients. Nephron. Clin. Pract. 2005;100:c20–c26. doi: 10.1159/000084654. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Kaysen GA, Greene T, Daugirdas JT, et al. Longitudinal and cross-sectional effects of C-reactive protein, equilibrated normalized protein catabolic rate, and serum bicarbonate on creatinine and albumin levels in dialysis patients. Am. J. Kidney. Dis. 2003;42:1200–1211. doi: 10.1053/j.ajkd.2003.08.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]