Abstract

Although voluntary enrollment by abusive men in domestic violence perpetrator treatment programs occurs, most men enter treatment only after they have injured a partner or family member and have been arrested, convicted and sentenced. This leaves a serious gap for those who engage in abusive behavior but who have not been served by the legal or social service systems. To address this gap, the researchers applied social marketing principles to recruit abusive men to a telephone-delivered pre-treatment intervention (the Men’s Domestic Abuse Check-Up—MDACU), designed to motivate non-adjudicated and untreated abusive men who are concurrently using alcohol and drugs to enter treatment voluntarily. This article discusses recruitment efforts in reaching perpetrators of intimate partner violence, an underserved population. Informed by McGuire’s communication and persuasion matrix, the researchers describe three phases of the MDACU’s marketing campaign: (1) planning, (2) early implementation, and (3) revision of marketing strategies based on initial results. The researchers’ “lessons learned” conclude the paper.

Keywords: Abusive men, Social marketing, Recruitment, Early intervention, Prevention

Most abusive men enter treatment after a prolonged history of abusive behavior, usually following arrest and adjudication (Gondolf 2002). Although research has found engagement in and completion of domestic violence treatment to be strongly associated with reduced recidivism, participants often drop out prematurely (Daly and Pelowski 2000). The Men’s Domestic Abuse Check-Up (MDACU), an intervention being tested in a three year randomized controlled trial funded by the National Institute on Drug Abuse, was designed to reach non-adjudicated, untreated, substance-using men who abuse their female or male partners. Participating in the check-up was intended to motivate them to talk about their behaviors, learn about treatment options, and voluntarily enter treatment. (See Neighbors et al. (2008) and Roffman et al. (2008) for detailed discussions of the theoretical and conceptual foundations of this brief intervention.) The study called for a 14-month recruitment window in which 124 participants were to be enrolled. The taboo nature of the issue and its widespread presence in nearly all demographic niches required recruitment from the general population using a unique marketing campaign.

In this paper we discuss the initial phases of the participant recruitment marketing campaign for this project: (1) planning, (2) early implementation, and (3) revision of marketing strategies based on initial results. First, however, we draw on models of substance abuse intervention and consider a conceptual framework for social marketing.

A Model of Early Intervention

A brief intervention first developed for alcohol abusers offers a potentially effective model to motivate abusive men to seek and complete treatment. Recognizing that many who abuse alcohol neither seek treatment voluntarily nor self-initiate change, researchers in New Mexico developed an innovative approach called The Drinkers’ Check-Up (DCU). Their program offered adult alcohol consumers the opportunity to be assessed and then receive non-confrontational feedback about their drinking (Miller et al. 1988). Publicity emphasized that the check-up was a respectful and non-pressured chance to evaluate one’s drinking experiences, weigh the pros and cons, and consider future options. The DCU was successful in both eliciting voluntary participation by untreated alcohol abusers and in prompting subsequent treatment enrollment or self-initiated change (Miller et al. 1988). It stimulated researchers focusing on other problems and populations to test adaptations of this approach (Walker et al. 2007) that has come to be known as motivational enhancement therapy (MET). The DCU and MET were the bases of the model being used in the MDACU.

A Conceptual Framework for Social Marketing

McGuire’s (1985) communication and persuasion matrix offers a useful framework to inform social marketing strategies to stimulate recruitment for an intervention with abusive men. The matrix served as an important heuristic device that prompted us to seek answers to such questions as: Who are we trying to reach? What is a man engaging in abusive behavior thinking and feeling about his abusive behaviors? What message will likely resonate with him and prompt an inquiry? What words and images will likely be counterproductive with this man? What means of delivering a message is most likely to reach him? Just as the designers of the Drinkers’ Check-Up were faced with challenges in reaching untreated alcohol abusers, our goal of reaching untreated and non-adjudicated abusive men required accurate conclusions concerning the target population.

Social marketing is the use of communication strategies to increase knowledge and change thoughts or behaviors (Kotler and Roberto 1989). McGuire’s (1985) communication and persuasion matrix describes inputs that consist of five communication components and outputs, that indicate successful outcomes.

With reference to inputs, the Receiver is the intended recipient of the message, and includes characteristics such as gender, age, education, and held attitudes. The Message is the content being communicated, including message appeal and style (e.g., focusing on the negative impact of domestic violence or highlighting benefits of ceasing abusive behaviors). A Channel is a medium used to deliver the message to the receiver (e.g., advertisements, news coverage, posters, word of mouth, etc.). The Source is the person or institution that sends the message, including that person’s or institution’s credibility or expertise.

Finally, the Target concerns the intended outcome of the message, i.e., what the receiver should know or do based on the communication. Marketing campaigns vary in their targets. Cognitive change campaigns are designed to educate or increase public awareness, while value change campaigns are meant to influence beliefs or values. Behavior change campaigns attempt to alter a particular behavior, and action change campaigns are designed to facilitate a directed response among receivers (Kotler 1982). Cognitive and action change campaigns are often used to recruit participants for intervention outcome trials (Campbell et al. 2004). McGuire’s matrix guided the research team as it reviewed pertinent social marketing literature in the domestic violence field, sought the input of consultants, and made decisions about the construction of the recruitment campaign.

Social Marketing Efforts with Abusive Men

In the initial planning phase we conducted an extensive search for previous or existing marketing campaigns that focused on influencing abusive men to take action. We identified three relevant efforts that contributed to the development of our marketing strategies: a needs assessment conducted in Seattle (The Anonymous Abuse Helpline), a Western Australia campaign (Freedom from Fear), and a confidential 24-h phone line for men in Minnesota (The Men’s Line). In all three campaigns, the message encouraged abusive men to call a hotline number. Callers were assessed and given referrals to domestic violence services.

The Anonymous Abuse Helpline was a pilot study conducted in 1993 by the current research team. Designed to recruit adults who were concerned about their behaviors in their intimate relationships, this hotline was staffed by trained volunteers, most of whom were practitioners in the domestic violence field. An advertising firm donated time and creative staff effort to develop recruitment billboard ads, brochures, and television public service announcements. Additional channels included newspaper articles, and radio and television interviews. The billboard’s design portrayed an anniversary card that read: “Has she stayed with you out of love or fear?”

The Helpline received 79 calls in five weeks, with 30 callers completing the interviews and then being offered referrals to community programs. The investigators were heartened to see that people called and expressed interest in a project that gave them the opportunity to discuss their concerns about being abusive. While callers were offered anonymity, the researchers noted that 58% gave their names and mailing addresses in order to receive educational materials about local treatment resources by mail. The majority of the men (87%) who completed the interview said they would participate in a hypothetical phone intervention program to help abusive men talk to a counselor to sort out their relationship concerns.

Freedom from Fear (http://www.freedomfromfear.wa.gov.au), launched in 1998 in Western Australia, was designed to encourage abusive men to alter their violent behaviors and to seek help by calling a hotline number (Department of Community Development, Western Australia, 1998). The campaign’s channels included 30-s television commercials, newspaper advertisements, radio commercials, and public relations activities. The campaign’s messages, based on input from men in the general public and abusive men in treatment, avoided a confrontational or blaming tone. In addition, focus groups convened during the planning period stressed the need for the campaign to emphasize the impact of domestic violence on children, and to have a call-to-action: “Help is available” via the Men’s Domestic Violence Helpline. Almost two years after the campaign launched, a total of 2,543 men had called the helpline and self-identified as being at risk for domestic violence. Just over half (53%) accepted voluntary referral to domestic violence perpetrator treatment programs.

The Men’s Line, funded by the Minnesota Department of Public Safety, was initiated in 1997 and provides a free, confidential 24-h phone line for men, answered by trained counselors through the Twin Cities Crisis Line. Between 1997 and 2002 the Men’s Line had received 3,000 calls, mostly from men seeking advice on a number of issues including domestic abuse (visit http://www.co.ramsey.mn.us/ph/hb/initiative_mens_messages_action_team.htm for more information on the Men’s Line).

The findings from these three projects supported the notion that some abusive men are concerned about their behaviors and can be motivated through a marketing campaign to voluntarily seek support in discussing their concerns. The central question in the current check-up study is whether a discussion guided by motivational enhancement therapy principles will lead participants to initiate steps toward voluntarily entering domestic violence or substance abuse treatment.

Planning a Marketing Campaign for Abusive Men

Prior to the start of enrollment for the MDACU trial, 8 months were devoted to planning recruitment strategies that would reach adult males (18 years of age or older) who were: (a) being abusive to their spouses or partners, (b) using alcohol or other drugs, (c) concerned about their behavior in their intimate relationships, (d) concerned about their substance use, (e) not currently in treatment or being adjudicated for domestic violence, and (f) from diverse socio-demographic backgrounds.

These criteria required that the marketing be universal (i.e., broadly directed at men in the general population). Men who engage in domestic violence represent every occupational and educational niche; every racial, ethnic and cultural group; every socioeconomic stratum; every religious persuasion; every sexual orientation; and every geographical location. Given continued stigma and shame associated with domestic violence and the absence of a specific profile for this target population, developing a universal recruitment campaign presented a substantial challenge.

The campaigns discussed above suggested that eliciting phone calls from abusive men for the purpose of talking about a taboo topic requires marketing that would appeal to men who are in an early phase of readiness to change. A stages of change model (DiClemente et al. 1991), initially developed to discuss the phases of change in smoking behavior, conceptualized two early stages for which the check-up intervention seemed appropriate: pre-contemplation and contemplation. Thus, we elected to focus on pre-contemplators (men who are experiencing adverse consequences due to their domestic abuse and substance use, but do not recognize their behavior as problematic or are not considering making changes) and contemplators (those who are considering reducing or eliminating their abusive behaviors, but are ambivalent or not ready to make a commitment).

A contract was awarded to a local marketing firm with extensive experience developing advertisements on social issues, and equipped with creative staff, designers, and media relations experts. Further, a number of human services professionals, including seven domestic violence intervention professionals, aided the research team. In addition to specialists who work with abusive men, it was important to have practitioners who work with victims to help ensure that the project’s marketing strategies would not inadvertently compromise the victims’ safety. To enhance inclusiveness in the study’s marketing campaign, consultants were selected whose clientele represented populations diverse in race, ethnicity, socio-economic background, and sexual orientation. Finally, nine men who had successfully completed a domestic violence perpetrator treatment program participated in two focus groups. They ranged in age from those in their twenties to some in their fifties, and were diverse in terms of marital status, parenthood, and ethnicity. Modest honorarium payments ($75) were given to each participant.

Following McGuire’s (1985) matrix, the processes of obtaining feedback in individual and group discussions were structured to obtain data on: message (language, content, and appeal), channel (most effective methods for conveying the message to the intended recipients), and receiver/target (attitudes of abusive men, perceptions of seeking help, and relevant behavior and action change messages). Working as focus group participants, the consultants initially brainstormed a wide variety of potential messages (project names, logo designs, images, and text). During later focus group sessions, participants reviewed draft iterations of the project’s marketing products that had been developed based on their earlier input.

The participants used a structured, numeric protocol to rate the marketing products individually and then discussed their ratings as a group. Focus group participants rated the impact of 10 initial ads using a five-point Likert scale (“Very Poor” to “Very Good”): the message, photo, name, logo, impact and relevance of the ad for our target audience. Participants then ranked each ad on its overall impact. Descriptive analyses using SPSS yielded three highest rated photos and messages that were also unanimously endorsed by focus group participants during a follow-up discussion (see the following section for a discussion of the three final ads).

Early Implementation of the Marketing Campaign

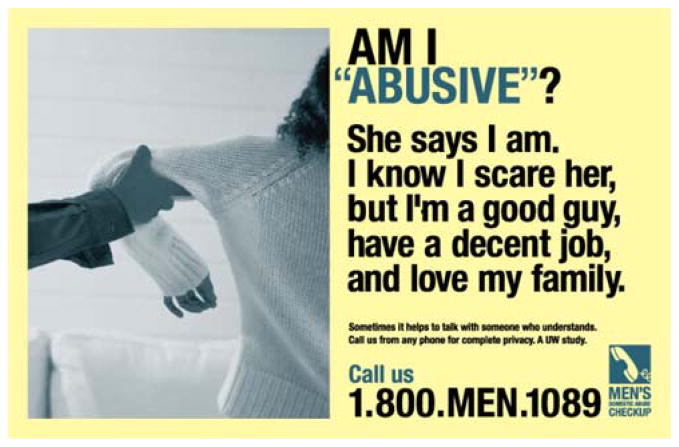

The planning process resulted in the articulation of each element in the campaign. Figures 1 and 2 are examples of a display advertisement and the text of a radio ad that were used in the campaign’s early implementation.

Fig. 1.

Display advertisement—Partner print ad

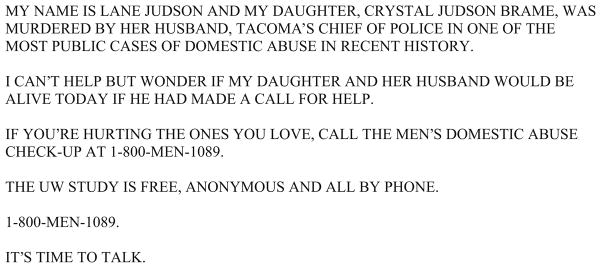

Fig. 2.

Script of 30-s radio ad—father of a murdered daughter

Receiver

The intended receivers were substance-using male abusers who are neither being adjudicated nor in counseling, and who may be struggling with mixed feelings about changing their behaviors. Because study participants were given the opportunity for an optional in-person session at the project office to learn about community agencies, the campaign sought to recruit receivers who lived within 45 miles of the University of Washington. Due to budget constraints, the first phase of the campaign was limited in focus to heterosexual men.

Finding the right photos for advertising that would portray abusive men in a manner consistent with the project’s intervention was a considerable challenge. Focus group participants stressed the importance of avoiding images that might arouse defensiveness in men who were ambivalent about making changes. Gory images of injured victims or portrayals of men engaging in violent acts were expected to draw out such defensiveness.

The marketing firm staff and research team reviewed close to 100,000 images on various stock photo websites. Initial images selected by the marketing team, while powerful, were found to be either too violent, too depressing, or have no obvious relevance (e.g., man looking very depressed in a dark room, or a child alone on a couch). Although the Freedom from Fear campaign found much success focusing on the impact of domestic violence on children, the MDACU focus group participants recommended including the image of a man and having at least one photo include a family unit to represent domestic violence within a relationship or family context. Two of the three chosen photos exhibited racial diversity.

Message

Following McGuire’s (1985) framework, the research team considered six elements of the message: (1) thoughts the receiver may have, (2) the source, (3) the nature of the program, (4) the benefits the receiver can expect to experience, (5) protections offered to the receiver, and (6) the target behavior intended for the receiver.

Thoughts the receiver may be having

Curiosity about one’s behaviors, being uncertain about the severity of consequences of those behaviors, and wondering about the possibility of change were among the receiver’s thoughts that the campaign was designed to reflect. As can be seen in the display ad in Fig. 1, phrases such as “Abusing your family? Abusing alcohol or drugs? Not sure?”; “She’s afraid of you, does it have to be that way?”; and “Ever wonder how to make the fear in their eyes disappear?” were meant to target receivers who at some level were motivated to make changes.

The source

Each product produced for the project’s marketing identified the University of Washington as the source. As will be noted below, the researchers recruited two individuals to serve as secondary sources by offering testimonials. See Fig. 2 for the text of a radio ad that featured one of these individuals.

The nature of the program

As had been the precedent in this type of motivational enhancement therapy program (Miller and Sovereign 1989), the term “check-up” was included in the project name to emphasize its differentiation from treatment. The intention was for the receiver to understand that the program involved an assessment and feedback, without expectations or pressure to commit to behavior change or treatment entry. The project name also needed to make it evident that the receiver was an abusive man, thus “The Men’s Domestic Abuse Check-Up.”

In order not to “turn off” potential participants, the logo used in display ads and other publicity materials emphasized the words MEN’S and CHECK–UP in larger, bolder type, with “domestic abuse” displayed in smaller, lighter font. Finally, to comply with Institutional Review Board requirements, each marketing product identified the project as a study.

The benefits that the receiver can expect to experience

It was important to emphasize that the program was neither confrontational nor burdensome in terms of time and effort required. MDACU was described as a brief and non-judgmental opportunity to take stock. The message was intended to convey the project staffs’ stance that participants would be responded to as regular guys who are concerned about their behavior toward their partners. The consultants recommended a tagline (“Let’s talk about your options”) to further emphasize that the project offered an invitation to have a conversation rather than requiring a commitment to behavior change.

Protections offered to the receiver

All marketing materials noted that the participant’s confidentiality would be assured. Moreover, the message conveyed the fact that callers had the option of retaining their anonymity (see Roffman et al. (2008) for a description of the study’s methodology).

The intended target behavior

To encourage men to initiate a phone call to the project, it was preferable that the number could easily be memorized or jotted down. Ideally, the phone number would convert to letters that represented the project name, i.e., check-up. To avoid possible confusion, using 800 or 888 rather than more recent toll-free area codes was also preferable. While options were limited, the phone number assigned to the project included “MEN” in the prefix: (800) MEN-XXXX.

To reinforce the message that the services were delivered by phone, the icon of the phone in the advertising logo was designed to be easily recognizable at a quick glance (see Figs. 1 and 3). The choice to use a rather old-fashioned phone with the spiral cord was intentional; it gave the image a kinetic feel. The researchers intended this to be interpreted as an invitation to pick up a phone and call, making the ad seem a literal “call to action.”

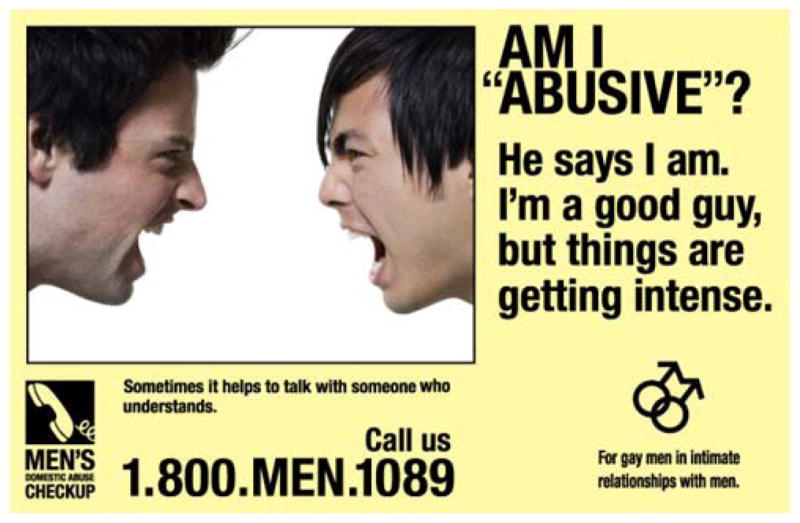

Fig. 3.

Display advertisement—for men in relationships with men

Channel

The channels initially selected for marketing included: news stories; paid ads in print media and radio; advertisements in buses; a website; brochures and flyers disseminated via community agencies, corporations, clinics, bars, coffee shops, and law enforcement precincts; and staff presentations to human services professionals. Each channel had been used successfully in similar recruitment efforts, including Freedom from Fear.

News coverage and feature stories in the mainstream press are effective in reaching ambivalent men who may otherwise not be reached (Campbell et al. 2004; Stephens et al. 2000). The researchers contracted with the marketing firm’s media relations department to design and execute a press conference to launch the study. The media relations manager widely disseminated a press release the day before the press conference, and personally contacted select television and print reporters. A press kit was put together for the media that included: the study’s three photo ads in postcard sizes, biographical sketches of the panelists speaking at the press conference, pertinent national and local domestic violence statistics, and a press release.

Panelists at the press conference included domestic violence researchers, educators, and practitioners providing perpetrator and victim services. Two additional panelists were a man who had completed a domestic violence perpetrator treatment program, and the father of a local woman murdered by her abusive husband in front of their children that had received extensive media coverage. This father’s comments emphasized the seriousness of failing to intervene early in domestic violence. Media coverage following the press conference and launch led to requests for interviews by a columnist (local daily newspaper) and radio reporters (talk show and local public radio station). Project staff continued to solicit coverage of the project by seeking radio interviews and news stories. Opinion essays describing the project were submitted by staff to local newspapers for publication on their op-ed pages. Often, press interviews and opinion essays were linked to current events (e.g., the arrest of a prominent athlete).

Paid ads (display and classified ads) were placed in the daily newspapers (Seattle Times and Seattle Post-Intelligencer) (see Fig. 1). Although more expensive than alternative weekly newspapers, ads were placed in the weekend magazine sections of daily newspapers to give the ads more shelf life. Other daily newspaper ads were varied in their placement among the sports, local, and business sections. In addition, a weekly alternative newspaper (The Stranger) initially was chosen to complement the daily newspapers, and later became the main print ad channel because of its popularity with men in their 20s and 30s, its affordability, and a longer shelf life compared to the daily newspapers.

The photographic display ads, modified for bus interiors, were placed on 80 metro routes. Two 30-s radio spots featuring the murdered woman’s father and the abusive man who had completed treatment were run during drive times (mostly during the evening commute, 3–7 p.m.). (See Fig. 2 for the text of one radio ad.)

The researchers developed informational materials for display and distribution in informal community settings: conferences, coffee shops, libraries, community centers, etc. (For examples of the display materials, visit http://www.menscheckup.org.) These informal placements required much networking and outreach to a variety of organizations and service providers. The research team’s pre-existing connections in the community and new connections made as the project developed contributed to expanding opportunities. Based on earlier experiences (Campbell et al. 2004; Fisher et al. 1996), the researchers decided to deliver materials personally instead of sending them in the mail. The project director with available staff and volunteers literally canvassed local establishments in busy neighborhoods placing ads in such places as men’s restrooms, on bar counters, and bulletin boards.

A website was designed as an additional channel for the study. Intended to inform service providers, family members, and potential participants who want more information on the project, the website includes a brief overview, the study’s newspaper ads, featured news articles, and radio ads that can be easily downloaded. The website also includes materials for project participants to download through a password-protected login.

The researchers sought to mobilize two additional channels: installations of the U.S. Navy in the region and Seattle-area police departments. While local Navy personnel (e.g., domestic violence counselors and other human services professionals) were enthusiastic about publicizing the Men’s Domestic Abuse Check-Up via Navy hospitals, clinics, and newspapers, official approval for this was denied. Approximately 50 law enforcement agencies in the Seattle area were sent materials about the project and asked to offer the resource when officers made domestic disturbance calls. A small percentage of these departments agreed to do so. The Seattle Police Department declined.

Revisions in the Marketing Campaign Based on Initial Findings

Prompted by a sluggish rate of screened calls (82 calls and 24 enrolled participants over a period of 22 weeks, resulting in a rate of four calls and one enrolled participant per week), several shifts in the marketing campaign were made approximately 5 months after recruitment began. Project staff brainstormed alternative marketing messages and channels and were able to move ahead with the awarding of supplemental funds.

Receiver

Funding limitations had initially prevented the development of specific ads targeting subpopulations of abusive men. Securing additional funding made it possible to create a photo and text ad specifically targeting gay men (see Fig. 3), and to place display ads in newspapers written primarily for specific racial and ethnic populations (African American, Latino, Asian American, Jewish).

Message

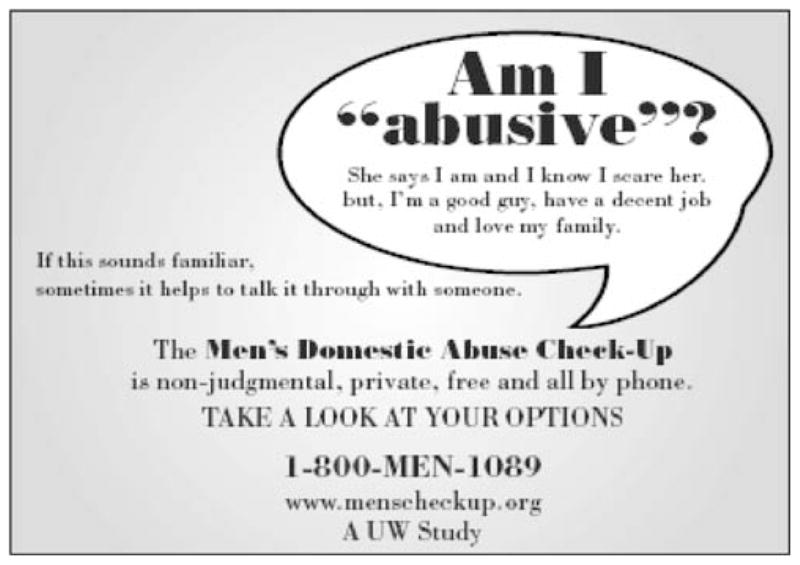

A new display ad focused on what a potential caller to the project may be thinking: “Am I abusive? She says I am. I know I scare her, but I’m a good guy, have a decent job, and love my family.” Creative staff at a local newspaper serving the Jewish community, JT News, placed this message within a thought bubble, a catchy way to illustrate what a caller might be saying to himself (see Fig. 4). The research team liked the new design and subsequently incorporated it into all print ads. “Sometimes it helps to talk to someone,” was placed above the telephone number to reinforce the call-to-action.

Fig. 4.

Newspaper text advertisement

Incentive payments, while described during the informed consent process, had not been mentioned in the initial ads. The new ads mentioned compensation for participating. Incentive payments are commonly given to research participants, but their existence may raise a question concerning what actually motivates participants in clinical trials. Therefore, the researchers added a question to an already established project evaluation survey for the purpose of measuring the compensation’s influence in motivating receivers to call, participate in, and complete the project.

The radio ad length was expanded from 30 to 60 s giving more time to repeat the phone number and to emphasize the non-judgmental, respectful nature of the program. The researchers also developed a new theme for the radio ads that reflected the current season or a current event. The first seasonal ad after the winter holidays was followed by Super Bowl, Valentine’s Day, Mother’s Day, and Father’s Day themed ads. Another new ad portrayed a hypothetical project caller’s thoughts about his experience as a participant (see Fig. 5).

Fig. 5.

Script of 60-s radio advertisement—hypothetical participant

Channel

Display ads were run in other culturally-specific newspapers or magazines, including Colors (multi-racial monthly magazine), Seattle Gay News (weekly newspaper), JT News serving the Jewish community in Washington (twice a month newspaper), Asian Pacific Weekly (weekly newspaper), The Seattle Medium (African-American weekly newspaper), and SEA Latino (weekly newspaper). After the first four months, the bus advertisements were discontinued due to extremely low generation of calls from this channel. The new radio advertisements were placed on stations with a large percentage of male listeners. After initially focusing on a Seattle-area sports talk station, radio advertising was expanded to stations that emphasized news and current events programming.

When the campaign was initially planned, the researchers specifically avoided any attempt to encourage women who were victims of domestic abuse to serve as channels. The risk of harm was considered to be substantial. However, as callers mentioned that they learned about the project through a newspaper clipping sent to them anonymously or through another indirect hint from a friend or family member, the staff revised the marketing efforts to include agencies that provide services only to women (e.g., victim/survivor services). The researchers have increasingly reached out to colleagues in the domestic violence field to help spread the word.

Following the revisions to the marketing campaign discussed above, the rate of screened calls and enrolled participants increased from four calls and one enrolled participant per week to eight calls and three enrolled participants per week. The project reached its enrollment target of 124 enrolled participants over a total period of 55 weeks, sooner than anticipated.

Conclusions

Revisions to the marketing strategies discussed above jump-started a steady flow of calls to the project. Although a later manuscript will compare the relative effectiveness of specific marketing strategies, the following section shares lessons learned thus far.

A universal marketing campaign is expensive

Project team members who were involved with the 1993 Anonymous Abuse Helpline were pleasantly surprised then at their ability to reach and engage 79 callers over a period of only 5 weeks. That success may have given the current team false encouragement for the project’s marketing efforts, particularly in terms of cost. Moreover, the researchers substantially underestimated the cost of marketing.

The “it doesn’t happen here” belief can obstruct marketing

Staff hit several unexpected barriers when simply trying to place recruitment materials in waiting rooms in health care settings or men’s restrooms in a variety of locations. While the researchers expected most establishments and institutions to find the project a worthwhile resource for their customers or employees and to agree that domestic violence is a bad thing and should be stopped, significant resistance was voiced. Responses such as: “lack of space” (some health care facilities), “legal department said ‘No’” (military), or “it would send a different message” (law enforcement), blocked efforts in a number of key venues. The belief that “it doesn’t happen here,” may have played a role in the reluctance of institutions to accept our materials, amplified by the concern that such materials may send the unintended message that domestic violence perpetrators are among their employees or customers.

Some radio talk show hosts use attack strategies in interviews

The day after the project’s press conference launch, the project director was invited to give a radio interview and was caught off guard by talk show commentators debating and challenging tangential aspects of the project. Domestic violence is a demanding and often politically-charged topic. Some media professionals tend to shift the focus onto women as perpetrators, and seek an outrageous morsel that will keep listeners tuned in. No one is interested in hearing about a dog biting a man. It is “Man Bites Dog!” that gets attention. Subsequently, staff carefully reviewed media requests for interviews to evaluate whether the project’s aims would be well served or damaged by such exposure.

Finally, two results of the project’s marketing have been highly encouraging. First, the study has been successful in meeting its enrollment target and appears to be on course in being able to answer its key research questions. Second, the nature of the callers’ experiences and the eagerness many are voicing to end their violence in their relationships suggests that a brief telephone intervention may hold promise as an innovative approach to ending violence earlier (see Roffman et al. (2008) for a description of the intervention).

A successful marketing campaign is crucial in reaching otherwise underserved populations such as non-adjudicated and untreated abusive men. The high cost of marketing may yield priceless benefits in terms of saving lives and guiding people to effective services. The MDACU project demonstrates how McGuire’s (1985) communication and persuasion matrix can be a useful framework for any agency planning a marketing campaign to recruit hard-to-reach populations.

Acknowledgments

This project is supported by a grant from the National Institute on Drug Abuse, 1 RO1 DA017873.

Contributor Information

Lyungai F. Mbilinyi, Email: Lyungai@u.washington.edu, School of Social Work, University of Washington, 909 NE 43rd Street, Seattle, WA 98105, USA

Joan Zegree, School of Social Work, University of Washington, 909 NE 43rd Street, Seattle, WA 98105, USA.

Roger A. Roffman, School of Social Work, University of Washington, 909 NE 43rd Street, Seattle, WA 98105, USA

Denise Walker, School of Social Work, University of Washington, 909 NE 43rd Street, Seattle, WA 98105, USA.

Clayton Neighbors, Department of Psychiatry and Behavioral Sciences, University of Washington, Seattle, WA, USA.

Jeffrey Edleson, School of Social Work, University of Minnesota, St. Paul, MN, USA.

References

- Campbell ANC, Fisher DS, Picciano JF, Orlando MJ, Stephens RS, Roffman RA. Marketing effectiveness in researching the non treatment-seeking marijuana smoker. Journal of Social Work Practice in the Addictions. 2004;4:39–59. [Google Scholar]

- Daly J, Pelowski S. Predictors of dropout among men who batter: A review of studies with implications for research and practice. Violence and Victims. 2000;15:137–160. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Department for Community Development: Family and Domestic Violence Unit, Government of Western Australia. Freedom from Fear: Development of the Campaign Advertising Strategy. Western Australia: Department of Community Development; 1998. Retrieved from: www.freedomfromfear.wa.gov.au. [Google Scholar]

- DiClemente CC, Prochaska JO, Fairhurst S, Velicer WF, Rossi JS, Velasquez M. The process of smoking cessation: An analysis of precontemplation, contemplation, & contemplation/action. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 1991;59:295–304. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.59.2.295. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fisher DS, Ryan R, Esacove AW, Bishofsky S, Wallis JM, Roffman R. The social marketing of project ARIES: Overcoming challenges in recruiting gay and bisexual males for HIV prevention counseling. Journal of Homosexuality. 1996;31:177–202. doi: 10.1300/J082v31n01_11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gondolf EW. Batterer Intervention Systems: Issues, Outcomes, and Recommendations. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Kotler P. Marketing for Nonprofit Organizations. 2. Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice-Hall; 1982. [Google Scholar]

- Kotler P, Roberto EL. Social Marketing. New York, NY: Macmillan; 1989. [Google Scholar]

- McGuire WJ. The nature of attitudes and attitude changes. In: Lindzey G, Aronson E, editors. Handbook of Social Psychology. New York, NY: Random House; 1985. pp. 233–346. [Google Scholar]

- Miller WR, Sovereign RG. The check-up: A model for early intervention in addictive behaviors. In: Loberg T, Miller WR, Nathan PE, Marlatt GA, editors. Addictive behaviors: Prevention and early intervention. Amsterdam: Swets and Zeitlinger; 1989. [Google Scholar]

- Miller WR, Sovereign RG, Krege B. Motivational interviewing with problem drinkers: II. The drinker’s check-up as a preventive intervention. Behavioural Psychotherapy. 1988;16:251–268. [Google Scholar]

- Neighbors C, Walker DD, Edleson JL, Roffman RA, Mbilinyi LF. Self-determination theory and motivational interviewing: Complementary models to elicit voluntary engagement by partner-abusive men. American Journal of Family Therapy. 2008 doi: 10.1080/01926180701236142. in press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roffman R, Edleson J, Neighbors C, Mbilinyi L, Walker D. The Men’s Domestic Abuse Check-up: A protocol for reaching the non-adjudicated and untreated Man who batters and abuses substances. Journal of Violence Against Women. 2008;14 doi: 10.1177/1077801208315526. in press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stephens RS, Roffman RA, Curtin L. Comparison of extended versus brief treatments for marijuana use. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2000;68:898–908. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Walker DD, Roffman R, Piciano J, Stephens R. The check-up: In-person, computerized, and telephone adaptations of motivational enhancement treatment to elicit voluntary participation by the contemplator. Substance Abuse Treatment, Prevention, and Policy. 2007;2:2. doi: 10.1186/1747-597X-2-2. http://www.substanceabusepolicy.com/content/2/1/2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]