Abstract

Phosphite (Phi), a phloem-mobile oxyanion of phosphorous acid (H3PO3), protects plants against diseases caused by oomycetes. Its mode of action is unclear, as evidence indicates both direct antibiotic effects on pathogens as well as inhibition through enhanced plant defense responses, and its target(s) in the plants is unknown. Here, we demonstrate that the biotrophic oomycete Hyaloperonospora arabidopsidis (Hpa) exhibits an unusual biphasic dose-dependent response to Phi after inoculation of Arabidopsis (Arabidopsis thaliana), with characteristics of indirect activity at low doses (10 mm or less) and direct inhibition at high doses (50 mm or greater). The effect of low doses of Phi on Hpa infection was nullified in salicylic acid (SA)-defective plants (sid2-1, NahG) and in a mutant impaired in SA signaling (npr1-1). Compromised jasmonate (jar1-1) and ethylene (ein2-1) signaling or abscisic acid (aba1-5) biosynthesis, reactive oxygen generation (atrbohD), or accumulation of the phytoalexins camalexin (pad3-1) and scopoletin (f6′h1-1) did not affect Phi activity. Low doses of Phi primed the accumulation of SA and Pathogenesis-Related protein1 transcripts and mobilized two essential components of basal resistance, Enhanced Disease Susceptibility1 and Phytoalexin Deficient4, following pathogen challenge. Compared with inoculated, Phi-untreated plants, the gene expression, accumulation, and phosphorylation of the mitogen-activated protein kinase MPK4, a negative regulator of SA-dependent defenses, were reduced in plants treated with low doses of Phi. We propose that Phi negatively regulates MPK4, thus priming SA-dependent defense responses following Hpa infection.

Plants deploy an innate immune system including an array of preformed barriers and inducible responses for defense against invading pathogens. A type of induced resistance (IR) is the systemic acquired resistance (SAR) found in adjacent and distal plant parts after infection by a necrotizing pathogen, and it requires salicylic acid (SA; Delaney et al., 1994) and the presence of the defense regulatory protein Nonexpressor of Pathogenesis-Related protein1 (NPR1; Durrant and Dong, 2004). Another type of IR is induced by nonpathogenic growth-promoting rhizobacteria and is called induced systemic resistance, which requires jasmonate (JA) and ethylene (ET; van Loon et al., 1998).

IR is often associated with the priming phenomenon, the augmented capacity to mobilize cellular defense responses following challenge by a broad spectrum of pathogens (Conrath et al., 2002; Conrath, 2011). Thus, inoculation of Arabidopsis (Arabidopsis thaliana) leaves with the avirulent strain of Pseudomonas syringae pv tomato (Pst) DC3000 carrying the AvrRpm1 gene primes defense responses to subsequent challenge by the virulent strain Pst DC3000 (Kohler et al., 2002). Priming is also effective in plants after root inoculation with beneficial rhizobacteria (van Wees et al., 2000; Conrath et al., 2002; Verhagen et al., 2004). Similarly, treatments with natural or synthetic compounds enhance resistance responses only after pathogen challenge. Treatment of plants with SA, riboflavin (vitamin B2), thiamine (vitamin B1), menadione, 2,6-dichloroisonicotinic acid, benzo(1,2,3,)thiadiazole-7-carbothioc acid S-methyl ester (BTH), the nonprotein amino acid β-aminobutyric acid (BABA), or phosphite (Phi) has been shown to prime defenses for augmented responses to pathogens (Kauss et al., 1992; Kauss and Jeblick, 1995; Katz et al., 1998; Zimmerli et al., 2000; Ahn et al., 2007; Borges et al., 2009; Zhang et al., 2009; Eshraghi et al., 2011). Numerous studies have attempted to decipher the molecular components of defense priming (Zimmerli et al., 2000; Kohler et al., 2002; Ton et al., 2005; Zhang et al., 2009). BABA has been shown to prime defenses against Hyaloperonospora arabidopsidis (Hpa; formerly Peronospora parasitica or Hyaloperonospora parasitica) through an SA- and NPR1-independent signaling pathway (Zimmerli et al., 2000; Ton et al., 2005). BABA-IR involves increased deposition of callose at the site of attempted infection (Zimmerli et al., 2001; Ton and Mauch-Mani, 2004). However, the biochemical and molecular mechanism(s) of priming remained poorly understood until fairly recently. Beckers et al. (2009) demonstrated that defense priming resulted from the accumulation of inactive mitogen-activated protein kinases (MAPKs) following pathogen challenge, leading to the development of systemic immunity. The MAPK cascade involves three functionally linked protein kinases, a MAP kinase kinase kinase (MEKK), a MAP kinase kinase (MKK), and a MAP kinase (MPK; Colcombet and Hirt, 2008). The elevated accumulation of inactive forms of the MAPKs MPK3 and MPK6 in Arabidopsis exposed to BTH was proposed as a possible priming mechanism (Beckers et al., 2009). Chromatin modifications and alteration of primary metabolism have also been shown to be linked to priming (Schmitz et al., 2010; Jaskiewicz et al., 2011).

Phi (HPO32−/H2PO3−), an oxyanion of phosphorous acid (H3PO3), is the reduced form of phosphate (Pi) and as such may be considered as a structural analog of Pi. Phi, a phloem-mobile molecule, is especially effective against oomycete diseases (Guest and Bompeix, 1990; Guest and Grant, 1991). The mode of action of Phi is still unknown and debated. At high concentrations, Phi inhibits mycelial growth of Phytophthora species through direct toxicity (Fenn and Coffey, 1984) by inhibiting key phosphorylation reactions (Niere et al., 1994). Phi also activates plant defense responses (Saindrenan and Guest, 1994). Phi-induced resistance in cowpea (Vigna unguiculata) infected with Phytophthora cryptogea was suppressed by the application of a competitive inhibitor of Phe-ammonia lyase and isoflavonoid phytoalexin biosynthesis (Saindrenan et al., 1988). Similarly, Phi-induced resistance and localized cell death are inhibited by quenchers of superoxide anion in Phi-pretreated Arabidopsis seedlings inoculated with zoospores of Phytophthora palmivora (Daniel and Guest, 2006). Phi was recently shown to directly enhance the expression of defense genes and to prime callose deposition and hydrogen peroxide (H2O2) accumulation in Arabidopsis infected with Phytophthora cinnamomi (Eshraghi et al., 2011). All these results only provide correlative evidence for an indirect mode of action of Phi, and there is still no conclusive evidence on the mode of action of Phi and its potential target(s) in the plant.

The Hpa-Arabidopsis pathosystem is a suitable model to unravel the physiological and molecular mechanism(s) underlying Phi-IR. Effector-triggered immunity (ETI) in Arabidopsis against Hpa is mediated by the isolate-specific RPP resistance genes through SA-dependent or -independent pathways depending on the isolate used (McDowell et al., 2000; van der Biezen et al., 2002). Among the early signaling events and cellular responses in plants acting downstream of pathogen-associated molecular patterns or avirulence genes is the activation of the MAPK cascade (Asai et al., 2002; Nakagami et al., 2005). Thus, resistance to the Hpa avirulent isolate Hiks1 was compromised in MPK6-silenced Arabidopsis ecotype Columbia (Col-0) plants (Menke et al., 2004), and overexpression of the MKK7 gene enhanced resistance to the Hpa isolate Noco2 (Zhang et al., 2007). Reactive oxygen species (ROS) are part of the early components of defense responses in Arabidopsis. The plasma membrane NADPH oxidase enzyme Arabidopsis respiratory burst oxidase homolog D (ATRBOHD) was shown to be responsible for a stronger oxidative burst in ETI triggered by the Hpa isolate Emco5 (Torres et al., 2002). SA is a component essential in ETI and in basal resistance as the SA induction-deficient2-1 (sid2-1) mutant (Nawrath and Métraux, 1999), and SA hydroxylase (NahG) plants are impaired in resistance to virulent and avirulent isolates of Hpa. In addition, ETI as well as basal defense against Hpa in Arabidopsis involve Enhanced Disease Susceptibility1 (EDS1) and its interactor Phytoalexin Deficient4 (PAD4), two lipase-like proteins that are required for SA accumulation (Jirage et al., 1999; Feys et al., 2001), as well as NPR1 activation and accumulation of the Pathogenesis-Related protein1 PR1 (Durrant and Dong, 2004).

This study aims to dissect the mechanism(s) underlying Phi-IR in Arabidopsis against Hpa. Here, we show that Phi exerts a dual activity in a concentration-dependent manner with either a priming-inducing activity in the plant or direct inhibition of the pathogen. At low concentrations (10 mm or less), Phi primes defense responses against infection of Arabidopsis Col-0 by the normally virulent Hpa Noco2. Phi-induced priming depends on SA signaling and mobilizes EDS1-PAD4 and NPR1 but is independent of other known pathways of hormone signal transduction. Finally, we identify Phi as a negative regulator of the MAPK MPK4 and present evidence that decreased gene expression, accumulation, and phosphorylation of this kinase are part of Phi-induced priming against Hpa in Arabidopsis.

RESULTS

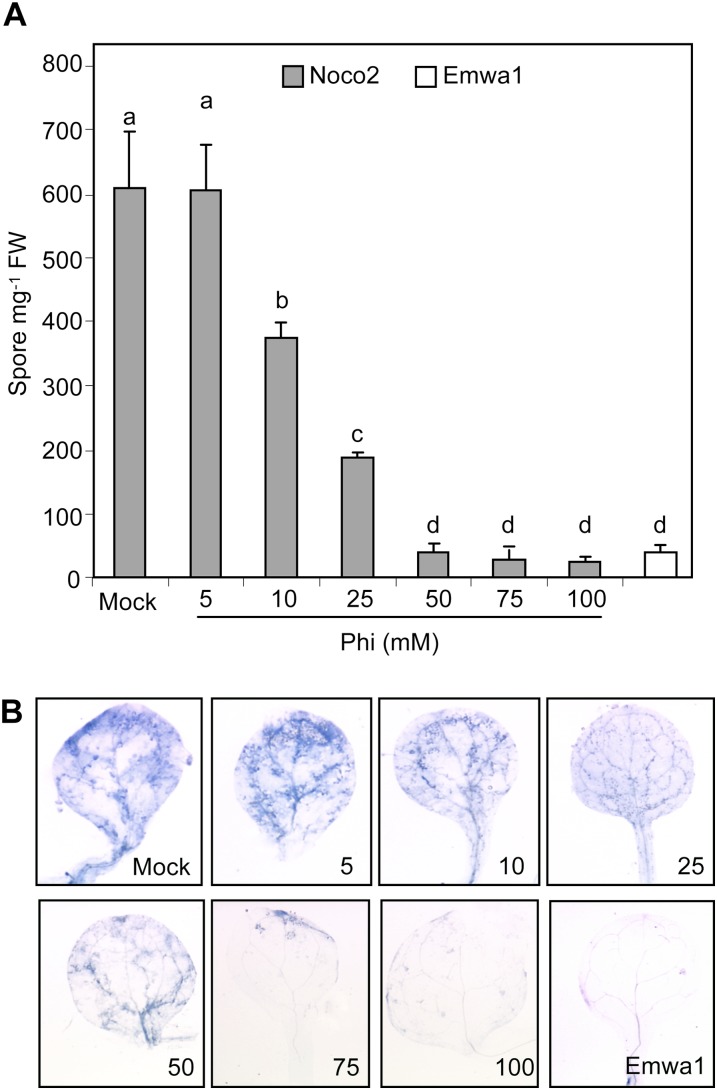

Phi Pretreatment Renders Arabidopsis More Resistant to Hpa

We inoculated Phi-pretreated Arabidopsis ecotype Col-0 with the virulent Hpa isolate Noco2 to assess the protective effect of Phi. The avirulent isolate Emwa1 interacts with Col-0 through the RPP4 resistance gene (van der Biezen et al., 2002) and was used to compare genetic and chemical-induced resistance. Plants were treated by soil drenching with Phi (5–100 mm) or with MES (mock) 72 h prior to inoculation with Hpa spores. Susceptibility was assessed by counting the number of pathogen spores formed on the leaf surface and by microscopically examining hyphal growth in inoculated leaves at 7 d post inoculation (dpi). There was no difference in the germination rate of inoculated spores on leaves of Phi-pretreated plants compared with mock-pretreated plants (data not shown). Sporulation of Hpa was not affected by 5 mm Phi treatment, whereas 10 and 25 mm Phi treatments proportionately decreased spore numbers, and 50 mm Phi or more inhibited sporulation as much as in the incompatible interaction with the avirulent Emwa1 (Fig. 1A). The effect of Phi treatments on hyphal growth in leaf tissues closely matched the reduction in Hpa spore production (Fig. 1B), indicating that spore number gives a valid estimate of susceptibility. Soil drenching with 10 mm Phi as soon as 24 h before Hpa inoculation reduced spore number by 35% compared with mock-inoculated plants, but the same concentration applied simultaneous to inoculation or 24 h post inoculation (hpi) had no effect (Supplemental Fig. S1). This indicates that Phi does not exhibit any curative effect once the infection is established in leaf tissues.

Figure 1.

Phi effectiveness against Hpa. Two-week-old plants of the Col-0 wild type were treated by soil drenching with MES (as mock) or Phi (5–100 mm) at 72 h prior to being inoculated by Hpa isolate Noco2 or Emwa1 (5 × 104 spores mL−1). The level of infection was evaluated at 7 dpi by quantifying the number of pathogen spores on aerial tissues (A) and histochemical staining of pathogen mycelium in leaves with lactophenol-trypan blue (B). For inoculation with the Emwa1 isolate, plants were pretreated with MES. Values in A are means ± se of 15 replicates from five biological independent experiments. Letters indicate significant differences between values (ANOVA, Newman-Keuls test; P < 0.05). The experiments in B were repeated three times with similar results. FW, Fresh weight.

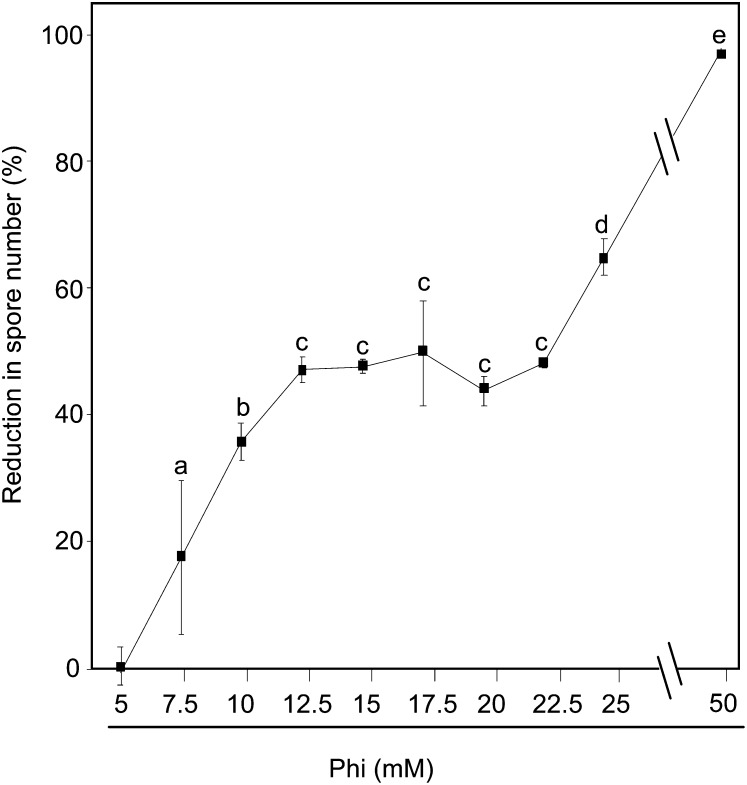

The Inhibition of Hpa by Phi Exhibits a Biphasic Dose-Dependent Response Curve

The effectiveness of Phi on Hpa Noco2 infection was analyzed in more detail at concentrations of 5 to 50 mm. Plants were inoculated 72 h after soil drenching with Phi, and spore number was determined at 7 dpi. Response curves were derived from the percentage inhibition of sporulation at each concentration of Phi relative to mock-pretreated plants. The dose-dependent response curve appears biphasic (Fig. 2). In the first phase, sporulation was inhibited linearly from 5 to 12.5 mm Phi, then it stabilized between 12.5 and 22.5 mm at approximately 43% inhibition across the range of doses. In the second phase, inhibition increased linearly to 97% from 22.5 to 50 mm Phi, consistent with a direct dose-related response to a toxicant. This biphasic dose response suggests the additive effect of independent responses to Phi. Thus, in contrast to most conventional fungicides, Phi exhibits a dual mode of action.

Figure 2.

Dose-response curve of Phi toward Hpa. Col-0 wild-type plants were treated and inoculated by Hpa isolate Noco2 as described in the legend of Figure 1. The effectiveness of Phi was calculated as a percentage of the reduction in spore number caused by Phi treatment. Values are means ± se of nine replicates from three biological independent experiments. Letters indicate significant differences between values (ANOVA, Newman-Keuls test; P < 0.05).

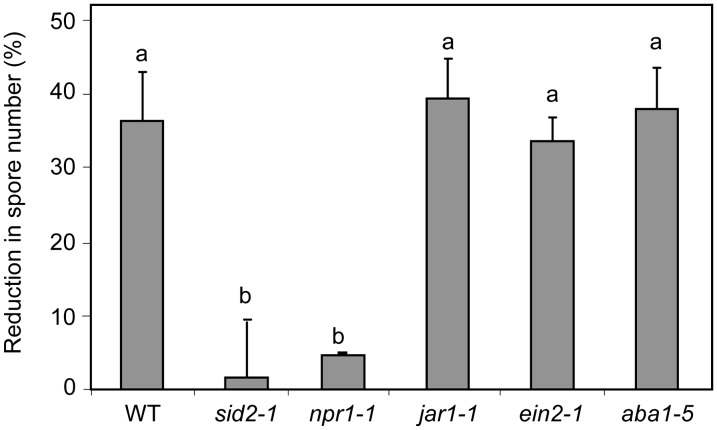

The Phi Effect at 10 mm Is Abolished in Arabidopsis Plants Defective in SA Signaling But Not in Mutants Impaired in JA- or ET-Dependent Signals and Abscisic Acid Biosynthesis

Mutants or transgenic plants impaired in signal transduction and biosynthesis pathways involved in IR were used to investigate the role of Phi-induced plant defenses in the inhibition of Hpa Noco2. The effectiveness of Phi against Hpa was first tested in the SA-deficient mutant sid2-1 (Nawrath and Métraux, 1999) treated with 10 mm Phi (Fig. 3), a dose that inhibited sporulation by 35% compared with mock-pretreated plants (Fig. 2). Spore number on the sid2-1 mutant was 2-fold higher (1,200 ± 48 spores mg−1 fresh weight) than on wild-type plants (610 ± 30 spores mg−1 fresh weight; data not shown), confirming that suppression of SA production in Col-0 affects basal resistance to Hpa isolate Noco2. More importantly, 10 mm Phi failed to reduce spore production on the sid2-1 mutant, indicating that SA signaling is essential for the 35% reduction in sporulation afforded by Phi in the Col-0 wild type (Fig. 3).

Figure 3.

Phi effectiveness against Hpa in different Arabidopsis-deficient signaling mutants. Col-0 wild-type plants (WT) as well as sid2-1, jar1-1, ein2-1, aba1-5, and npr1 mutants were treated with MES (as mock) or Phi (10 mm) and inoculated as described in the legend of Figure 1. The effectiveness of Phi was calculated as in the legend of Figure 2. Values are means ± se of 15 replicates from five biological independent experiments. Letters indicate significant differences between values (ANOVA, Newman-Keuls test; P < 0.05). Means ± se of spore numbers quantified on mock-pretreated plants of the wild type and sid2-1, npr1, jar1-1, ein2-1, and aba1-5 mutants were 610 ± 18, 1,200 ± 25, 625 ± 12, 610 ± 16, 595 ± 15, and 554 ± 13 spores mg−1 fresh weight, respectively.

NPR1 regulates SA-induced defenses downstream of SA and upstream of PR genes (Cao et al., 1994). Phi treatment reduced spore number by only 4.6% in npr1-1 compared with 35% in the wild type (Fig. 3). The response to 10 mm Phi treatment in the mutants jasmonate resistant1 (jar1-1), ethylene-insensitive2-1 (ein2-1), and abscissic acid-deficient1-5 (aba1-5), impaired in ET and JA signaling and abscisic acid (ABA) biosynthesis, respectively, was not compromised (Fig. 3), indicating that Phi-IR is independent of JA and ET signaling and ABA biosynthesis.

Overall, these findings indicate that 10 mm Phi partly protects Arabidopsis against Hpa through SA- and NPR1-dependent defense mechanisms. In NahG plants, the effect of 10 mm Phi is also totally suppressed, whereas it is only partially abolished at 25 mm (Supplemental Fig. S2), suggesting that the protection afforded at this concentration partly resulted from SA-independent factors. The response to increasing Phi was linear up to 50 mm (Supplemental Fig. S2), where sporulation was inhibited at similar levels in wild-type and NahG plants, indicating a direct toxicity to the pathogen. Unless otherwise stated, plants were treated with Phi at 10 mm throughout the following experiments.

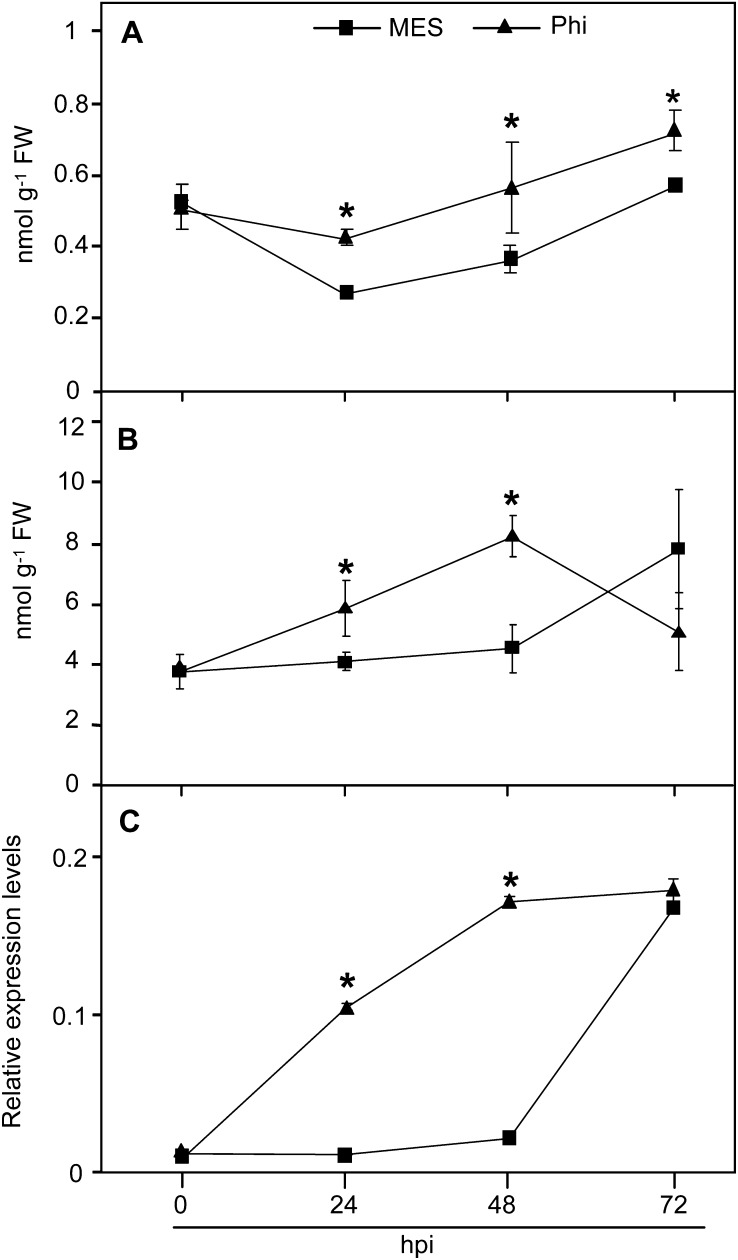

Phi Primes SA Accumulation and PR1 Expression

Priming only becomes apparent after pathogen challenge and may be monitored using markers of defense-associated cellular events (Conrath et al., 2002). As the SA signaling pathway was shown to be involved in the Phi-mediated protection of Arabidopsis against Hpa Noco2, we analyzed the impact of Phi treatment on the accumulation of free and total SA and on the expression of PR1, two important defense responses in our model system. No significant difference was observed in free and total SA levels between mock- and Phi-pretreated plants before inoculation (Supplemental Fig. S3). However, the levels of free SA detected in Phi-pretreated plants were significantly higher than in mock-pretreated plants at 24, 48, and 72 hpi (Fig. 4A). Total SA contents in Phi-pretreated plants were also significantly higher than those in mock-pretreated plants at 24 and 48 hpi (Fig. 4B). Phi-pretreated plants showed higher PR1 transcription earlier than did mock-pretreated plants, but the levels were similar to mock-pretreated plants at 72 hpi (Fig. 4C). Plant Defensin1-2 (PDF1-2), a biochemical marker of JA- and ET-induced defense responses against necrotrophs (Penninckx et al., 1996; Thomma et al., 1998), was weakly but not differentially induced in mock- and Phi-pretreated plants (Supplemental Fig. S4), confirming that Phi-IR is independent of JA/ET signaling in this pathosystem. Overall, these results indicate that Phi primes SA-dependent defenses for augmented responses against Hpa.

Figure 4.

Effects of Phi treatment on the accumulation of SA and PR1 transcripts in Arabidopsis in response to Hpa. Col-0 wild-type plants were treated and inoculated as described in the legend of Figure 3. A, Accumulation of free SA. B, Accumulation of total SA. C, Accumulation of PR1 transcripts normalized to the transcript level of the internal control gene ACTIN2. Levels of SA and PR1 transcripts were quantified by HPLC and qRT-PCR, respectively. Values in graphs are means ± sd of three replicates. The experiments were repeated twice with similar results. Asterisks indicate data that are significantly different between Phi and MES treatments (Mann-Whitney test; P < 0.05). FW, Fresh weight.

Phi-Induced Priming Is Independent of Phytoalexins and ATRBOHD-Dependent ROS

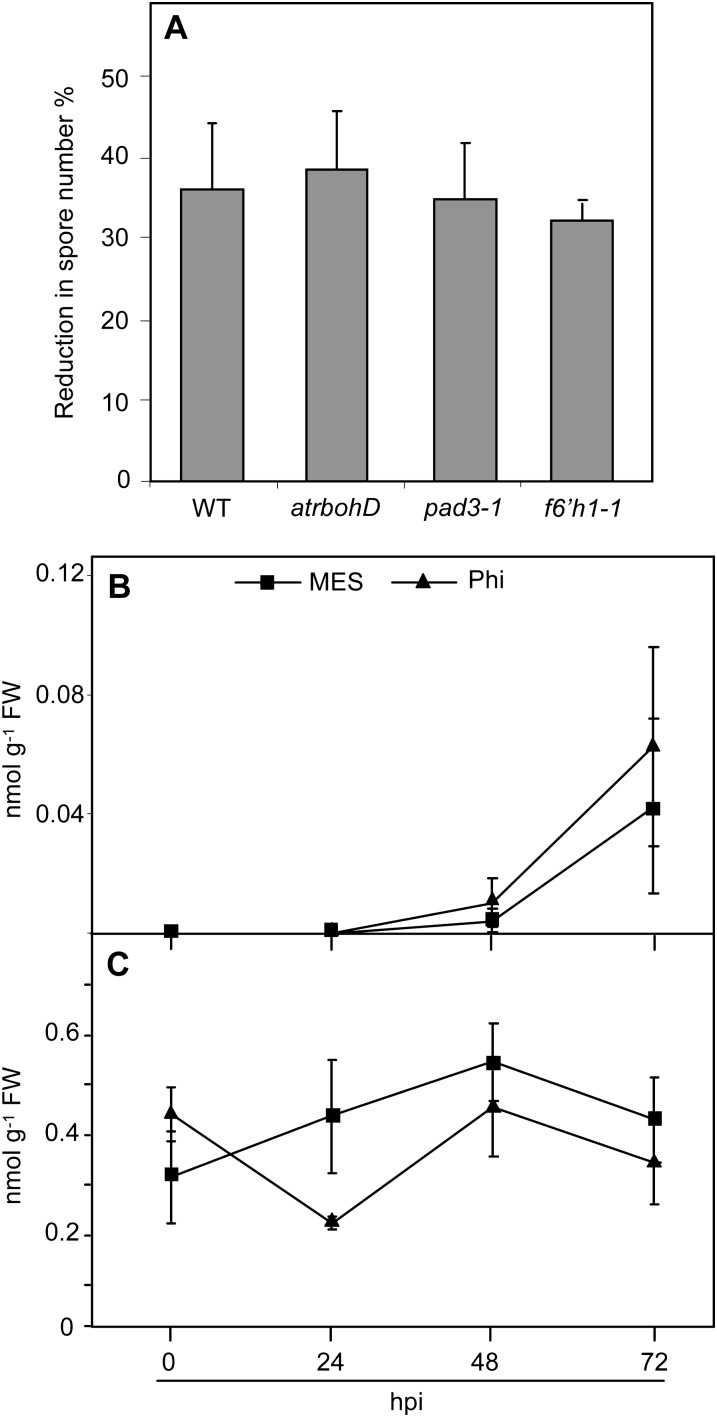

ROS produced by the membrane-associated ATRBOH NADPH oxidases play important roles in plant defense and are an early response to penetration of the Arabidopsis epidermis by an avirulent isolate of Hpa (Torres et al., 2002; Slusarenko and Schlaich, 2003). However, atrbohD mutants were equally responsive to 10 mm Phi as wild-type plants (Fig. 5A), suggesting that Phi-IR is independent of ROS produced by the membrane-bound ATRBOHD. As phytoalexins have been shown to be essential to Phi activity in other plant-oomycete interactions (Saindrenan et al., 1988; Nemestothy and Guest, 1990), we then examined the involvement of camalexin and scopoletin in Phi-induced priming using phytoalexin deficient3-1 (pad3-1; Böttcher et al., 2009) and feruloyl-CoA 6′hydroxylase1-1 (f6′h1-1; Kai et al., 2008) mutants. Phi-IR was not compromised in pad3-1 and f6′h1-1 mutants as in Col-0 wild-type plants (Fig. 5A), nor were levels of camalexin and scopoletin accumulation affected by Phi treatment, either before or after inoculation with Hpa (Fig. 5, B and C). These results indicate that ATRBOHD-dependent ROS, camalexin, and scopoletin are not components of Phi-induced priming against Hpa infection in Arabidopsis.

Figure 5.

Relationship between Phi effectiveness and ROS, camalexin, and scopoletin accumulation. Plants were treated and inoculated as described in the legend of Figure 3. A, Phi effectiveness in Col-0 wild-type plants (WT) and atrbohD, pad3-1, and f6′h1-1 mutants. Phi effectiveness was calculated as described in the legend of Figure 2. B, Levels of camalexin. C, Levels of total scopoletin. Values are means ± se of 15 replicates from five biological independent experiments in A and means ± sd of three replicates in B and C. No significant differences were found between values in A, B, and C (ANOVA, Newman-Keuls test; P < 0.05). The experiments in B and C were repeated twice with similar results. Means ± sd of spore numbers quantified on mock-pretreated plants of Col-0 wild-type plants and atrbohD, pad3-1, and f6′h1-1 mutants were 610 ± 75, 575 ± 46, 615 ± 40, and 680 ± 48 spores mg−1 fresh weight (FW), respectively.

Phi Primes Enhanced Expression of PAD4 and EDS1

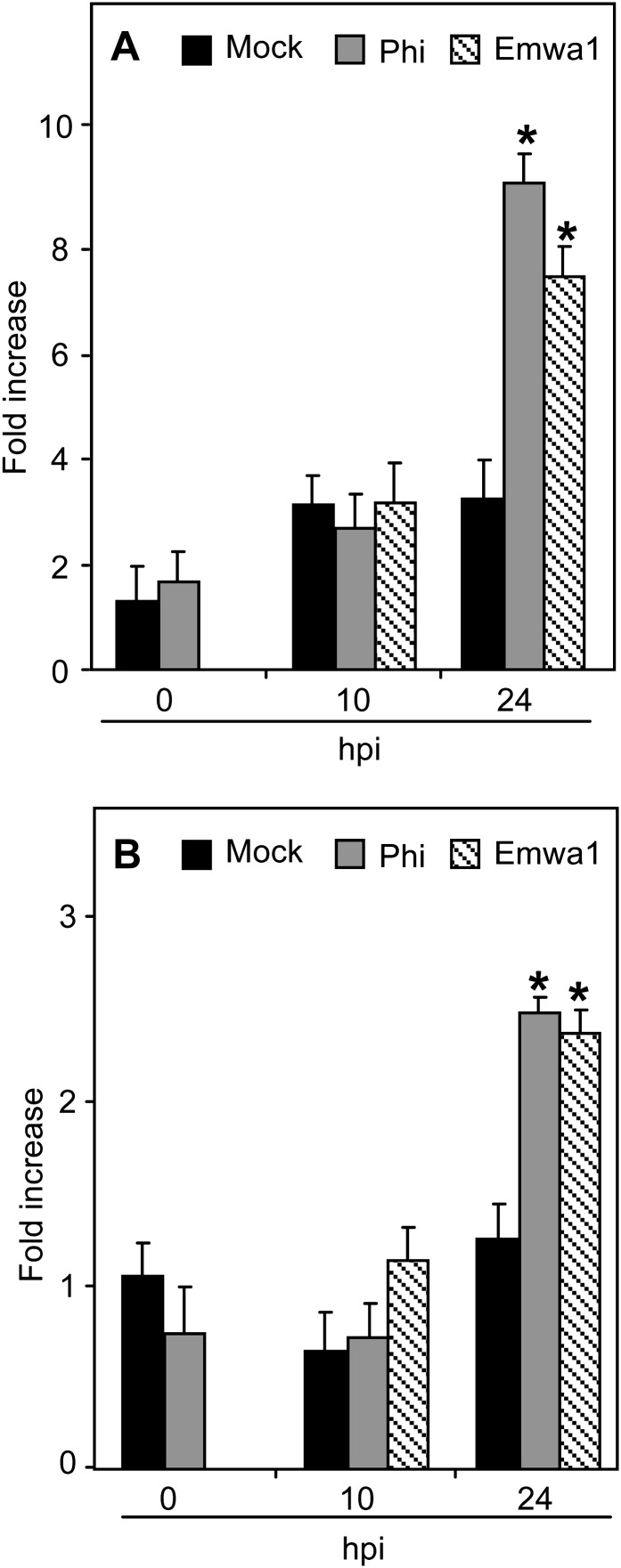

The interacting PAD4 and EDS1 proteins function upstream of SA and are required for SA signaling in ETI and basal resistance (Falk et al., 1999; Jirage et al., 1999; Brodersen et al., 2006), particularly in response to Hpa (Parker et al., 1996). Mutation in PAD4 impaired the response of Arabidopsis to Phi treatment after pathogen challenge, indicating that PAD4 is necessary for full Phi-IR (Supplemental Fig. S5). We monitored PAD4 and EDS1 expression in mock- and Phi-pretreated plants before and after inoculation with Noco2 using Emwa1-inoculated plants as positive controls. Levels of PAD4 and EDS1 transcripts were calculated relative to their expression at the time of Phi treatment (i.e. 72 h before inoculation with Hpa; Fig. 6). EDS1 and PAD4 were similarly expressed at the time of inoculation (0 hpi) in mock- and Phi-pretreated plants. Phi treatment enhanced the expression levels of PAD4 and EDS1 at 24 hpi, similar to those observed in Arabidopsis inoculated with Hpa Emwa1. These data indicate that PAD4 and EDS1 genes are primed upon Phi treatment.

Figure 6.

Effects of Phi treatment on PAD4 and EDS1 expression in Arabidopsis in response to Hpa. A, PAD4 expression. B, EDS1 expression. Plants were treated and inoculated as described in the legend of Figure 3. Samples were harvested at 0 h (before chemical treatment), 0 hpi (72 h post treatment), and 10 and 24 hpi. Levels of PAD4 and EDS1 transcripts were quantified by qRT-PCR, normalized to the level of the internal control gene ACTIN2, and expressed relative to their levels at 0 h. For inoculation with Emwa1, plants were pretreated with MES. For each time point, values are means ± sd of three replicates. Asterisks indicate significant differences between values (ANOVA, Newman-Keuls test; P < 0.05). The experiments were repeated three times with similar results.

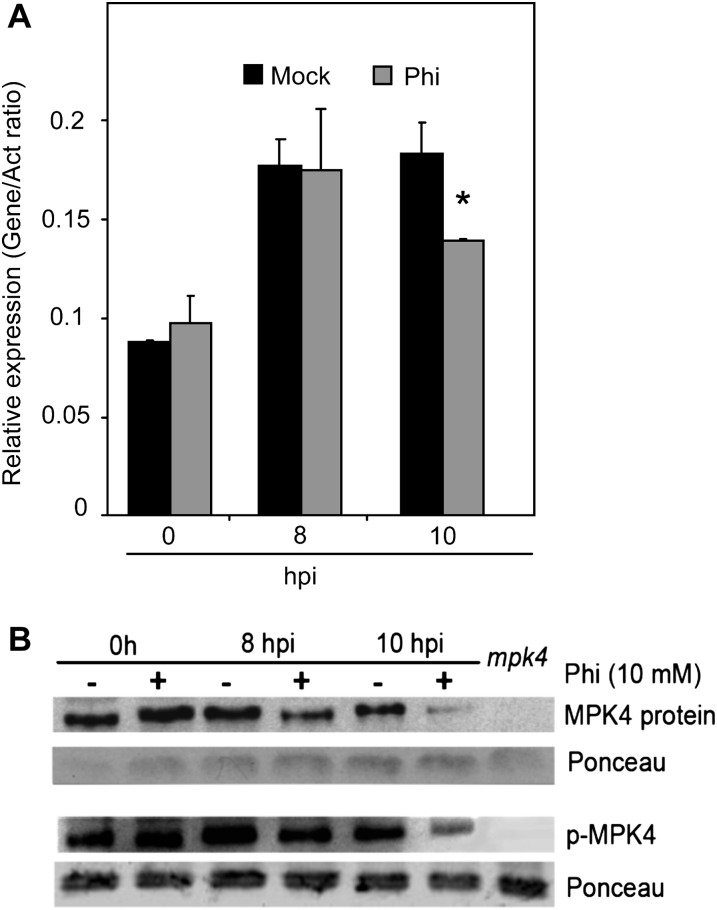

Phi Negatively Regulates MPK4 Transcription, MPK4 Protein Accumulation, and Phosphorylation

A genetic interaction between EDS1-PAD4 and the MAPK MPK4 regulates defenses against biotrophs (Brodersen et al., 2006). Loss-of function mpk4 mutants exhibit high levels of SA and PR1 transcripts and have increased resistance to the virulent pathogens Pst DC3000 and Hpa Noco2 (Brodersen et al., 2006). MPK4 expression was the same in mock- and Phi-pretreated plants at 8 and 24 h before inoculation and at the time of inoculation (Supplemental Fig. S6). Inoculation with Hpa induced similar levels of MPK4 expression at 8 hpi in mock- and Phi-pretreated plants (Fig. 7A), but by 10 hpi, MPK4 expression had declined in Phi-pretreated plants relative to mock-pretreated plants (Fig. 7A). The accumulation and phosphorylation state of MPK4 were monitored by western blotting leaf extracts with α-MPK4 and α-p44/42-ERK antibodies, respectively. MPK4 was present in similar levels in Phi- and mock-pretreated plants at 0 hpi (Fig. 7B). Importantly, upon challenge with the virulent pathogen, MPK4 levels significantly decreased at 8 and 10 hpi in Phi-pretreated plants. Phosphorylation of MPK4 was enhanced after inoculation in both mock- and Phi-pretreated plants (Fig. 7B), but to a lesser extent in Phi-pretreated plants (Fig. 7B; Supplemental Fig. S7). The signal that corresponds to the MPK4 protein was not detected in extract prepared from the mpk4 mutant.

Figure 7.

Effects of Phi treatment on gene expression, protein accumulation, and phosphorylation of MPK4 in response to Hpa. A, MPK4 expression. B, Accumulation and phosphorylation state of MPK4 protein. Plants were treated and inoculated as described in the legend of Figure 3. Samples were harvested at 0, 8, and 10 hpi. Two aliquots of leaf tissues were used for the quantification of MPK4 transcripts by qRT-PCR as for PR1 transcripts in the legend of Figure 4. Another aliquot of leaf tissues was used for protein extraction and SDS-PAGE. A polyclonal α-MPK4 antibody was used for the immunodetection of MPK4 protein. α-Phospho-p44/42 ERK antibody was used to check the phosphorylation state of MPK4. A leaf protein extract of the mpk4 mutant was used as a negative control for MPK4. The experiment was repeated three times with similar results. The asterisk indicates data that are significantly different between Phi and MES treatments (Mann-Whitney test; P < 0.05).

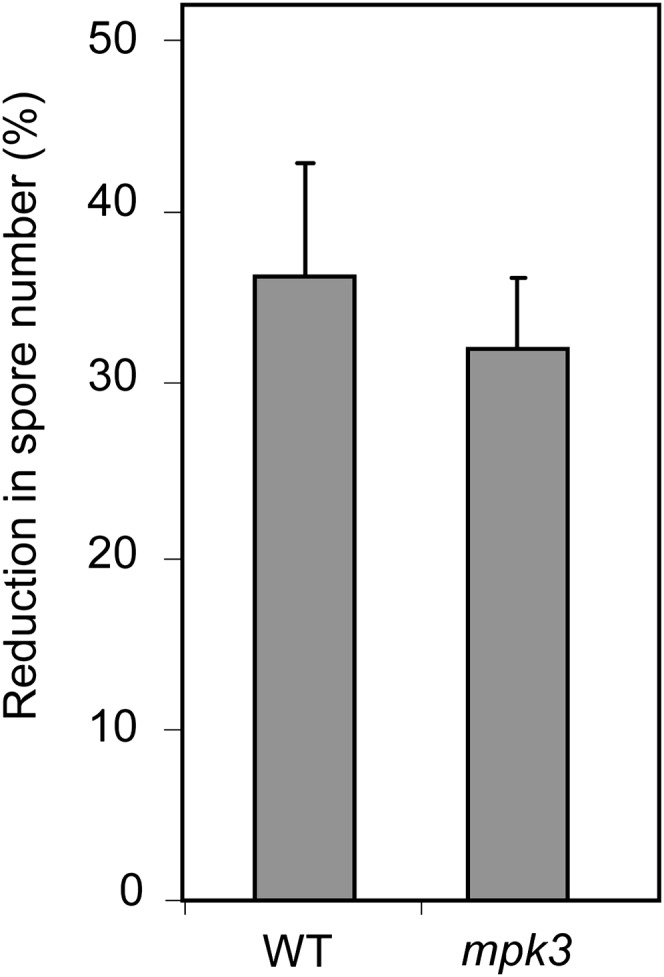

MPK3 was recently shown to be the major component for full priming of stress responses in Arabidopsis (Beckers et al., 2009). The involvement of MPK3 in Phi-induced priming to Hpa was tested using the mpk3 mutant. Mutation in MPK3 did not impair the response of Arabidopsis to Phi treatment after pathogen challenge, providing evidence that MPK3 is not required for Phi-IR (Fig. 8). Moreover, Phi did not modify MPK3 transcription, protein accumulation, or the phosphorylation state of MPK3 following pathogen challenge (Supplemental Fig. S8). Altogether, these results suggest that Phi specifically down-regulates MPK4 gene expression, MPK4 protein accumulation, and phosphorylation during the response of Arabidopsis to infection with Hpa Noco2.

Figure 8.

Phi effectiveness in mpk3 mutant and Col-0 wild-type (WT) plants against Hpa. Phi treatment, pathogen inoculation, and calculation of Phi effectiveness were performed as described in the legend of Figure 3. Values are means ± se of 15 replicates from five biological independent experiments. Phi effectiveness was not different between Col-0 and mpk3 plants (Mann-Whitney test; P < 0.05). Means ± se of spore numbers quantified in mock-pretreated plants of the Col-0 wild type and the mpk3 mutant were 600 ± 75 and 612 ± 62 spores mg−1 fresh weight, respectively.

DISCUSSION

Phi is extensively used to protect plants against diseases mainly caused by oomycetes (Lobato et al., 2010). The mode of action of Phi is unknown and remains controversial, given evidence for both direct and indirect modes of action (Guest and Grant, 1991). Here, we have dissected Phi-induced defense responses in the Arabidopsis-Hpa pathosystem to decipher the molecular mechanisms of Phi-IR. We show that Phi exerts a dual activity on Hpa infection in a concentration-dependent manner. Phi directly inhibits mycelial growth at high concentrations (50 mm or greater) but at low concentrations (10 mm or less) induces partial protection against Hpa by priming SA-dependent defenses and down-regulating MPK4.

Phi-Induced Protection Is Strictly Dependent on SA Signaling

Soil drenching Col-0 wild-type plants with 10 mm Phi at 72 h before inoculation with Hpa Noco2 reduced sporulation by 35% compared with mock-treated plants. Importantly, 10 mm Phi was completely ineffective in the sid2-1 mutant (Fig. 3), indicating that Phi inhibits pathogen growth via SA-dependent plant defenses at this concentration. It could be argued that Phi uptake and translocation in the leaves is modified by the absence of a functional SID2 protein, resulting in a lower concentration of the chemical at the site of infection. However, transgenic NahG plants also failed to respond to 10 mm Phi (Supplemental Fig. S2), independently confirming the involvement of SA-dependent defenses. Moreover, the npr1-1 mutant is insensitive to 10 mm Phi (Fig. 3), indicating that a functional NPR1 gene is required for IR and underscoring the importance of SA signaling in Phi-IR. Fosetyl-Al (aluminum Tris-O-ethyl phosphite; Aliette), an agrochemical that releases Phi, ethanol, and aluminum ions, was shown to protect Arabidopsis against Hpa when sprayed at high concentrations, and its effectiveness was only partially impaired in NahG plants and the non inducible immunity1 (nim1)/npr1 mutant (Molina et al., 1998). However, fosetyl-Al directly induced PR1 expression as a consequence of the chemical toxicity (Molina et al., 1998), confounding the identification of the precise function of Phi as a SAR activator.

ET, JA, and ABA were shown to be involved in activating certain defense responses in Arabidopsis (van Loon et al., 1998; Ton et al., 2009; Ballaré, 2011). Mutants of Arabidopsis affected in JA and ET perception and ABA biosynthesis were not impaired in their responsiveness to 10 mm Phi treatment after Hpa inoculation (Fig. 3). Moreover, transcriptional analysis of the JA- and ET-inducible PDF1.2 gene did not reveal any correlation with Phi-induced responses (Supplemental Fig. S4). Therefore, in this pathosystem, the effectiveness of Phi is strictly dependent on SA signaling.

Phi Exhibits a Dual Function in a Concentration-Dependent Manner

The inhibition of Hpa Noco2 by Phi exhibited an unusual biphasic dose-response relationship, suggesting that two independent factors contribute to pathogen restriction in this pathosystem. The first sigmoid in Figure 2 reflects the SA-dependent indirect mode of action of the chemical below 12.5 mm. Interestingly, the Phi effect is abolished in sid2-1 and NahG plants (Fig. 3; Supplemental Fig. S2). The second sigmoid, comprising between 22.5 and 50 mm Phi, reflects the direct toxicity of Phi to the pathogen, as Phi effectiveness is not compromised in NahG plants (Supplemental Fig. S2). Phi treatments between 12.5 and 22.5 mm induce a complex interaction combining indirect and direct modes of action and result in a 43% inhibition of the pathogen across the range of concentrations. This plateau might result from a saturation of Phi target(s) in the plant and/or in the pathogen, or it might indicate the maximal augmented capacity to express the IR (Ahmad et al., 2010). Beyond 22.5 mm Phi, the direct inhibition of mycelial growth overshadows the contribution of Phi-induced plant defenses to pathogen inhibition. Contrasting conclusions on the mode of action of Phi can be explained by understanding this bimodal activity. Phi exerts a dual activity in a concentration-dependent manner through either an SA signaling-dependent activity in the plant or a direct action on the pathogen.

Phi-Induced Resistance to Hpa Is Accomplished by Priming of a Subset of Defense Responses

Some chemicals do not trigger molecular defense responses per se, although they confer resistance to virulent pathogens by enhancing or priming plant capacity to express defense responses. Thus, the synthetic compounds 2,6-dichloroisonicotinic acid, BTH, and BABA and the natural compound SA are all potent inducers of priming and augmented defense-related gene expression and disease resistance at low concentrations (Kauss et al., 1992; Mur et al., 1996; Katz et al., 1998; Zimmerli et al., 2000). Noteworthy, Phi alone at 10 mm did not induce SA accumulation before inoculation with Hpa (Supplemental Fig. S3). However, SA accumulation and PR1 expression were augmented following pathogen challenge (Fig. 4). Thus, this clearly indicates that Phi primes defense responses in Arabidopsis, resulting in enhanced disease resistance to Hpa.

Phi was shown to induce an oxidative burst and phytoalexin accumulation associated with a hypersensitive-like response in cowpea and Arabidopsis infected with P. cryptogea and P. palmivora, respectively (Saindrenan et al., 1988; Daniel and Guest, 2006). The response of atrbohD mutants infected with Hpa to Phi was similar to that in the Col-0 wild type (Fig. 5), indicating that ROS produced from the plasma membrane NADPH oxidase do not contribute to the Phi-IR to Hpa in Arabidopsis. Camalexin and scopoletin are two phytoalexins that accumulate in Arabidopsis in response to pathogen challenge (Glawischnig, 2007; Simon et al., 2010) through PAD3 and F6′H1 activities, respectively (Kai et al., 2008; Böttcher et al., 2009). Recently, it was shown that the disease resistance of Arabidopsis to Phytophthora brassicae is established by the sequential action of indole glucosinolates and camalexin (Schlaeppi et al., 2010). However, it is not clear whether camalexin accumulation is a cause or a consequence of IR in the Arabidopsis-Hpa pathosystem (Mert-Türk et al., 2003). The expression of Phi-IR was unaffected in pad3-1 and f6′h1-1 mutants (Fig. 5A) and did not correlate with phytoalexin levels (Fig. 5, B and C), demonstrating that neither phytoalexin contributes to Phi-IR. Recently, it was reported that Phi elicited the accumulation of PR proteins associated with SA and JA/ET signaling pathways in noninoculated leaves of Arabidopsis and primed callose deposition and H2O2 accumulation after inoculation with P. cinnamomi (Eshraghi et al., 2011). It remains puzzling how Phi can prime for SA-inducible PR1 expression but not for ROS production in the Hpa-Arabidopsis interaction and enhanced production of H2O2 in the P. cinnamomi-Arabidopsis interaction. The differences observed between Phi-IR to Hpa and to P. cinnamomi might reflect the different lifestyles of biotrophic and hemibiotrophic oomycete pathogens and/or the recognition of different pathogen-associated molecular patterns by the plant, leading to the activation of different signaling pathways (Baxter et al., 2010).

Phi Mobilizes EDS1 and PAD4 Expression for Priming

EDS1 and PAD4 proteins are essential components of basal resistance and ETI to biotrophic pathogens (Parker et al., 1996; Jirage et al., 1999) and are required for SA accumulation following pathogen challenge (Falk et al., 1999; Jirage et al., 1999; Feys et al., 2001). Our data reveal that PAD4 and EDS1 expression is primed by Phi (Fig. 6). EDS1 and PAD4 are transcriptionally and posttranscriptionally regulated (Feys et al., 2001). Both proteins have been shown to be present in healthy plants (Feys et al., 2001), and after pathogen infection, gene expression changes dependent on EDS1 and PAD4 take place at early time points (Bartsch et al., 2006) before any reported protein up-regulation (Feys et al., 2001; Bartsch et al., 2006). This implies the activation of preexisting EDS1-PAD4 protein complexes and the existence of translational regulatory protein mechanisms. A common regulatory posttranslational modification is phosphorylation (Peck, 2003). However, changes in the phosphorylation state of either PAD4 or EDS1 in challenged plants have not yet been reported. It could be hypothesized that Phi activates preexisting EDS1 and/or PAD4 proteins. Thus, a possible mechanism of Phi-induced priming could be to modify normal EDS1 and/or PAD4 relocalization or redistribution between cytoplasmic and nuclear compartments after pathogen challenge (Feys et al., 2005; Rietz et al., 2011), as signaling through relocalization may be central to EDS1-PAD4 function (Feys et al., 2005; Bartsch et al., 2006). Phi treatment reduced sporulation by only 10% in the pad4 mutants compared with 35% in the Col-0 wild type (Supplemental Fig. S5), underlining that this lipase-like protein is a component of the Phi signal transduction pathway leading to IR. However, the delayed effect of Phi on the enhanced expression of EDS1 and PAD4 after pathogen challenge suggests a more likely target(s) upstream of EDS1-PAD4.

Phi-Induced Priming Involves the Negative Regulation of the MAPK MPK4

The MAPK MPK4 is required for normal plant growth and functions in a variety of physiological processes (Gao et al., 2008; Kosetsu et al., 2010). MPK4 is a negative regulator of SAR that is upstream of, but dependent on, EDS1 and PAD4 (Petersen et al., 2000). EDS1 and PAD4 are up-regulated in mpk4 mutants (Cui et al., 2010) that are also fully resistant to Hpa and Pst DC3000 (Brodersen et al., 2006; Gao et al., 2008). However, loss-of-function mpk4 mutants exhibit a dwarf phenotype, making it difficult to more directly address the role of MPK4 in Phi-induced priming. The Arabidopsis genome encodes more than 20 MPKs, including MPK3, MPK4, and MPK6, which are involved in innate immunity (Petersen et al., 2000; Asai et al., 2002; Menke et al., 2004). While Phi has no effect on MPK4 expression before inoculation (Supplemental Fig. S6), our data show that Phi induces the down-regulation of MPK4 gene expression, protein level, and phosphorylation at 10 hpi, indicating that Phi-IR is regulated at the transcriptional level (Fig. 7). It is of note that Phi does not affect MPK4 transcript accumulation at 8 hpi, while MPK4 protein levels and protein phosphorylation decreased (Fig. 7; Supplemental Fig. S7). It is possible that Phi induces an immediate degradation of MPK4 protein following pathogen inoculation that leads to later down-regulation of MPK4 gene expression. As MPK4 represses the expression of defense against Hpa (Brodersen et al., 2006), we propose that Phi-induced priming of Arabidopsis against Hpa involves the specific negative regulation of MPK4. BTH priming against the virulent Pst DC3000 strain was shown to be associated with increased activity of MPK3 and MPK6 (Beckers et al., 2009), two closely related proteins exhibiting a high level of functional redundancy (Colcombet and Hirt, 2008). It was assumed that MPK3 was the major component in primed defense gene activation by BTH, while MPK6 served a minor role (Beckers et al., 2009). MPK4 has an opposing effect to MPK3/MPK6 in the regulation of plant defense responses (Nakagami et al., 2005). MPK4 negatively regulates biotic stress signaling, while MPK3 and MPK6 act as positive components of defense responses (Pitzschke et al., 2009). Noteworthy, Phi-IR was not compromised in the mpk3 mutant (Fig. 8) and Phi did not modify MPK3 transcription, protein accumulation, or the phosphorylation state of MPK3 following pathogen challenge (Supplemental Fig. S8), suggesting that Phi-IR is rather linked to MPK4 activity. Future analyses with plants overexpressing MPK4 should help to specify the precise role of this MAPK in Phi-IR.

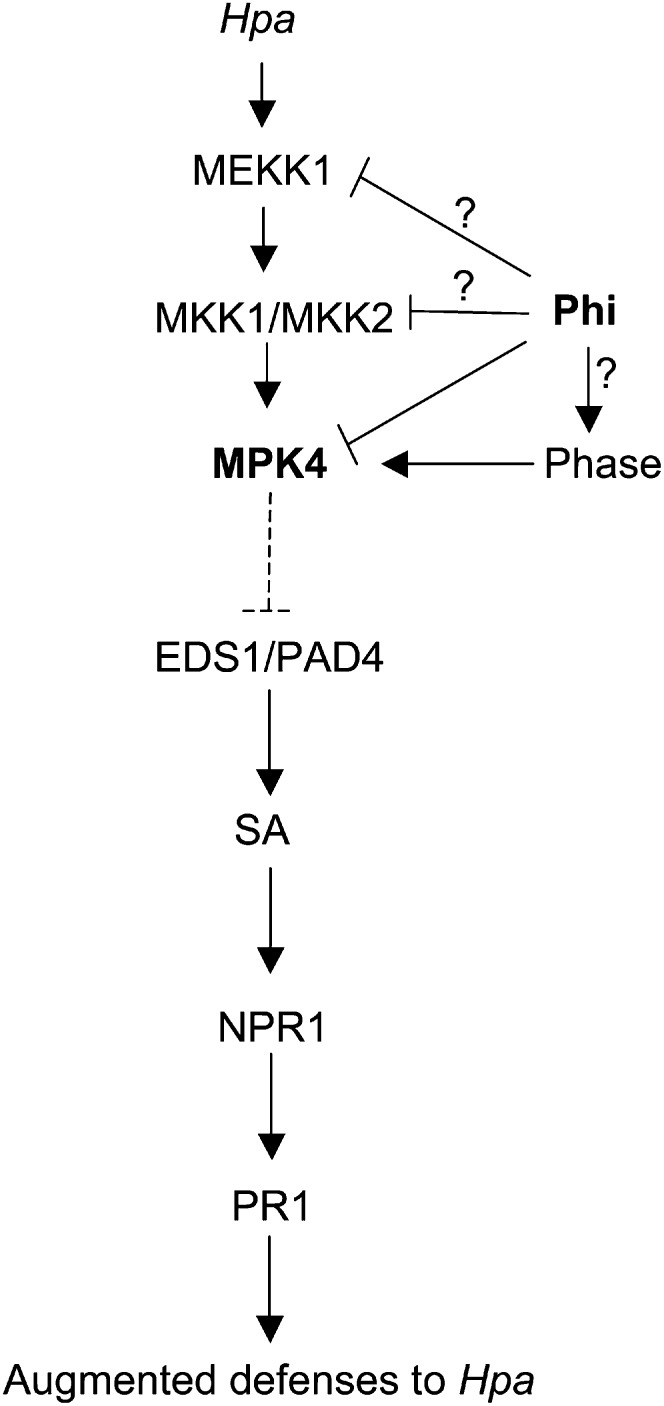

Phi-Induced Resistance to Hpa Involves Major Components of SA Signaling

Our data suggest a model of how Phi primes defense responses against Hpa (Fig. 9). Phi-IR involves EDS1 and PAD4 downstream of MPK4 (Fig. 6). MPK4 negatively regulates SA accumulation (Petersen et al., 2000), and the repression of MPK4 expression/MPK4 activity by Phi following pathogen infection results in enhanced accumulation of PAD4 and EDS1 transcripts, leading to augmented levels of SA and enhanced expression of PR1 (Fig. 4). Moreover, Phi primes SA-related defenses in response to Hpa infection through a NPR1-dependent signaling pathway (Fig. 3). Although NPR1-independent defense responses involving the transcription factor WHY1 have been described (Desveaux et al., 2004), we could not detect any change in WHY1 transcript accumulation in Phi-pretreated plants at 24 hpi (data not shown). While we suggest that Phi-induced priming results from the repression of an active MPK, an alternative, but not exclusive, explanation would be that priming could originate from one or more factor(s) upstream of MPK4. MPK4 functions in a cascade that includes the MAP kinase kinase kinase MEKK1 and the MAP kinase kinases MKK1 and MKK2 (Ichimura et al., 1998). Hence, it remains conceivable that Phi may target one of these components of the MAPK module. The single mkk1 and mkk2 T-DNA insertion mutants were as susceptible as the wild-type plants to the virulent strain Hpa Noco2, while mkk1/mkk2 double mutants were found to be highly resistant to the virulent oomycete pathogen (Qiu et al., 2008). Hence, plants expressing a constitutively active version of MKK1 and/or MKK2 would be more appropriate to improve Phi-IR in such a pathosystem.

Figure 9.

Model for priming by Phi for augmented defense responses in Arabidopsis infected with Hpa. Treatment with Phi inhibits the accumulation and phosphorylation of MPK4 after Hpa inoculation. The exact target(s) of Phi could be MPK4 or upstream components of the MAPK cascade as MEKK1 and MKK1/MKK2. Inactivation of MPK4 may also be mediated by Phase (for phosphatase protein[s]). Repression of MPK4 expression/MPK4 activity enhances PAD4 and EDS1 accumulation (dashed line) and triggers SA signaling-dependent priming for enhanced resistance through the defense regulatory protein NPR1.

Phi interferes with the Pi-sensing machinery in plants and suppresses plant responses to Pi deprivation (Varadarajan et al., 2002), but it does not affect cellular metabolism on Pi-sufficient medium (Ticconi et al., 2001). As Phi interferes with Pi metabolism (Danova-Alt et al., 2008), this suggests that its effect may be at the plant-pathogen interface, where the chemical would disrupt Pi homeostasis. Phosphatase genes are induced by Pi limitation at the transcriptional level (Misson et al., 2005; Thibaud et al., 2010) but also are repressed in high Pi. In Arabidopsis, regulated dephosphorylation and inactivation of MAPKs is mediated by MAPK phosphatases and PP2C-type phosphatases (Andreasson and Ellis, 2010). Inactivation of MPK4 was shown to be mediated by the Tyr-specific phosphatase PTP1 (Huang et al., 2000), the dual specificity (Thr/Tyr) protein phosphatase MKP1 (Ulm et al., 2002), or the PP2C-type phosphatase AP2C1 (Schweighofer et al., 2007). Upon pathogen infection, down-regulation of MPK4 by enhanced protein phosphatase activity derepresses the SA signaling pathway (Fig. 9). Therefore, Phi may prime the plants for augmented defense responses upon biotroph challenge by mimicking Pi starvation and inducing protein phosphatase activity(ies). This possibility can only be resolved by identifying the precise molecular target(s) of Phi.

CONCLUSION

It appears that signaling components like MPK4 and MPK3/MPK6 (Beckers et al., 2009) play a role in Arabidopsis in the priming phenomenon induced by Phi and BTH, respectively. In addition, it was shown that the Arabidopsis impaired BABA-induced setrility1 (ibs1) mutant, affected in a cyclin-dependent kinase-like protein, was impaired in BABA-induced priming of SA-dependent defenses (Ton et al., 2005). Overall, this underscores the importance of protein phosphorylation cascades in priming for enhanced defense responses in Arabidopsis.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Plant Materials

Arabidopsis (Arabidopsis thaliana) Col-0 and ecotype Wassilewskija-0 were used in this work. The mutants sid2-1 (Wildermuth et al., 2001), jar1-1 (Staswick et al., 2002), ein2-1 (Guzmán and Ecker, 1990), aba1-5 (Koornneef et al., 1982), npr1-1 (Cao et al., 1994), pad3-1 (Glazebrook and Ausubel, 1994), atrbohD (Torres et al., 2002), and f6′h1-1 (Kai et al., 2008) and transgenic NahG plants (Delaney et al., 1994) were all in the Col-0 background. Plants were grown in controlled-environment chambers under an 8-h/16-h day/night regime with temperatures of 20°C/18°C, respectively; light intensity was 100 μE m−2 s−1, and relative humidity was 65%. Plants were grown on 12-well plates filled with soil (2.5 mg of seeds per well). Two-week-old plants were used for experiments and pathogen maintenance.

Chemical Treatment

Seedlings were treated with potassium Phi or MES (27 mm; Sigma-Aldrich; http://www.sigmaaldrich.com/) as a control (2 mL per well) at 3 d prior to pathogen inoculation. Phosphorous acid (99%; Sigma-Aldrich) used in this study was partially neutralized with potassium hydroxide prepared in 27 mm MES to yield Phi (HPO32−/H2PO3−) at pH 6.3.

Pathogen Maintenance

Hyaloperonospora arabidopsidis isolates Noco2 and Emwa1 were obtained from Harald Keller and maintained weekly by transferring spores onto healthy seedlings of Col-0 and Wassilewskija-0 accessions, respectively. Spores were harvested by vortexing infected seedlings in water. Healthy seedlings were inoculated by spraying with spore suspension.

Pathogen Assay

Soil-grown seedlings on 12-well plates were inoculated by spraying with a 2-mL suspension of 5 × 104 spores mL−1. Inoculated seedlings were kept under high relative humidity for 1 dpi, returned to normal conditions, and then placed again at high humidity between 5 and 7 dpi. Spore production was evaluated at 7 dpi. Seedlings of each well were removed, weighed, and then vortexed in 5 mL of water for 10 min to liberate pathogen spores. Spores from three samples of each treatment were counted using a Nageotte chamber, and the means were converted to spore number mg−1 fresh weight.

Histochemical Staining

To visualize pathogen mycelium at the cellular level, infected plants were stained with trypan blue in lactophenol and ethanol at 7 dpi as described by Cao et al. (1998). The seedlings were destained overnight in saturated solution of chloral hydrate and imaged using a light macroscope (AZ100; Nikon).

Quantification of SA, Camalexin, and Scopoletin

SA, camalexin, and scopoletin were extracted and quantified as described by Simon et al. (2010). Standards of SA and scopoletin were from Sigma-Aldrich, whereas authentic camalexin was a kind gift of A.J. Buchala.

Analysis of Gene Expression

Total RNA was extracted from seedling tissue using Extract All Reagent according to the manufacturer’s recommendations (Eurobio; http://www.eurobio.fr/). Samples were subjected to RNase-free DNase I treatment (DNA-free kit; Ambion, Applied Biosystems; http://www.ambion.com/) for 30 min. Total RNA was determined at 260 nm using a spectrophotometer (NanoDrop; Thermo Scientific; http://www.nanodrop.com/). Reverse transcription reaction for cDNA synthesis was performed on 2 μg of RNA using oligo(dT) primers and the ImProm-II kit (Promega; http://www.promega.com/) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Quantitative reverse transcription (qRT)-PCR experiments were performed with 8 μL of a 1:10 dilution of cDNA and LightCycler 480 SYBR Green I Master (Roche; http://www.roche.fr/) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Relative transcript levels were determined by normalizing the PCR threshold cycle number of each gene with that of the ACTIN2 reference gene. The qRT-PCR primer sequences used in this work are supplied in Supplemental Table S1.

Protein Extraction and Immunodetection

Fifteen micrograms of total soluble protein extracted from Arabidopsis seedlings was separated by SDS-PAGE (12% acrylamide) as described (Conrath et al., 1997). Equal loading of protein was confirmed by Ponceau S staining. After transfer to a polyvinylidene difluoride membrane, immunodetection of MPK4 and MPK3 was performed with the SNAPid system (Millipore; http://www.millipore.com/) using anti-rabbit polyclonal antibodies raised against MPK4 and MPK3 (a kind gift from H. Hirt) at a 1:1,500 dilution. To detect phosphorylated MPK4 and MPK3, α-phospho-p44/42-ERK antibodies (α-P-MAPKact; Cell Signaling Technology; http://www.cellsignal.com/) were used at a 1:1,000 dilution (Heese et al., 2007). Antigen-antibody complexes were detected using horseradish peroxidase-conjugated anti-rabbit secondary antibody (Pierce; http://www.piercenet.com/) used at a 1:10,000 dilution and an enhanced chemiluminescence kit (Perkin-Elmer; http://las.perkinelmer.com/).

Statistical Analyses

All experiments were repeated at least two times with similar results. Means of acquired data were compared using ANOVA, Newman-Keuls, or Mann-Whitney test as indicated in the figure legends.

Supplemental Data

The following materials are available in the online version of this article.

Supplemental Figure S1. Incidence of timing of treatment on Phi effectiveness.

Supplemental Figure S2. Phi effectiveness in Col-0 wild-type and NahG plants against Hpa Noco2.

Supplemental Figure S3. Effect of Phi treatment on SA accumulation in Arabidopsis before inoculation with Hpa.

Supplemental Figure S4. Impact of Phi on PDF1.2 transcript accumulation in Arabidopsis in response to Hpa Noco2.

Supplemental Figure S5. Phi effectiveness in Col-0 wild-type and pad4 plants against Hpa Noco2.

Supplemental Figure S6. Impact of Phi on MPK4 expression in Arabidopsis before inoculation with Hpa.

Supplemental Figure S7. Quantification of immunodetection signals of MPK4 activity in Figure 7B.

Supplemental Figure S8. Effect of Phi treatment on gene expression, protein accumulation, and phosphorylation of MPK3 in response to Hpa Noco2.

Supplemental Table S1. Primers used in this work.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank David Guest (University of Sydney), Séjir Chaouch (CNRS-Université Paris-Sud 11), and Serge Kauffmann (CNRS, Strasbourg) for helpful discussion and comments on the manuscript. We are grateful to Harald Keller (INRA, Sophia-Antipolis), Heribert Hirt and Jean Bigeard (Unité de Recherche en Génomique Végétale, INRA, Evry), and Antony Buchala (University of Fribourg) for providing Hyaloperonospora isolates, MPK4/MPK3 antibodies, mpk3 mutant, and camalexin, respectively. Prof. Gilles Bompeix (Xeda International S.A., Saint Anidol) is particularly acknowledged for pioneering research on the mode of action of Phi.

Glossary

- Phi

phosphite

- Pi

phosphate

- Hpa

Hyaloperonospora arabidopsidis

- SA

salicylic acid

- MAPK

mitogen-activated protein kinase

- IR

induced resistance

- SAR

systemic acquired resistance

- JA

jasmonate

- ET

ethylene

- Pst

Pseudomonas syringae pv tomato

- BTH

benzo(1,2,3,)thiadiazole-7-carbothioc acid S-methyl ester

- BABA

β-aminobutyric acid

- H2O2

hydrogen peroxide

- ETI

effector-triggered immunity

- Col-0

ecotype Columbia

- ROS

reactive oxygen species

- dpi

d post inoculation

- hpi

h post inoculation

- ABA

abscisic acid

- qRT

quantitative reverse transcription

References

- Ahmad S, Gordon-Weeks R, Pickett J, Ton J. (2010) Natural variation in priming of basal resistance: from evolutionary origin to agricultural exploitation. Mol Plant Pathol 11: 817–827 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ahn IP, Kim S, Lee YH, Suh SC. (2007) Vitamin B1-induced priming is dependent on hydrogen peroxide and the NPR1 gene in Arabidopsis. Plant Physiol 143: 838–848 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Andreasson E, Ellis B. (2010) Convergence and specificity in the Arabidopsis MAPK nexus. Trends Plant Sci 15: 106–113 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Asai T, Tena G, Plotnikova J, Willmann MR, Chiu WL, Gomez-Gomez L, Boller T, Ausubel FM, Sheen J. (2002) MAP kinase signalling cascade in Arabidopsis innate immunity. Nature 415: 977–983 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ballaré CL. (2011) Jasmonate-induced defenses: a tale of intelligence, collaborators and rascals. Trends Plant Sci 16: 249–257 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bartsch M, Gobbato E, Bednarek P, Debey S, Schultze JL, Bautor J, Parker JE. (2006) Salicylic acid-independent ENHANCED DISEASE SUSCEPTIBILITY1 signaling in Arabidopsis immunity and cell death is regulated by the monooxygenase FMO1 and the Nudix hydrolase NUDT7. Plant Cell 18: 1038–1051 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baxter L, Tripathy S, Ishaque N, Boot N, Cabral A, Kemen E, Thines M, Ah-Fong A, Anderson R, Badejoko W, et al. (2010) Signatures of adaptation to obligate biotrophy in the Hyaloperonospora arabidopsidis genome. Science 330: 1549–1551 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beckers GJ, Jaskiewicz M, Liu Y, Underwood WR, He SY, Zhang S, Conrath U. (2009) Mitogen-activated protein kinases 3 and 6 are required for full priming of stress responses in Arabidopsis thaliana. Plant Cell 21: 944–953 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Borges AA, Dobon A, Expósito-Rodríguez M, Jiménez-Arias D, Borges-Pérez A, Casañas-Sánchez V, Pérez JA, Luis JC, Tornero P. (2009) Molecular analysis of menadione-induced resistance against biotic stress in Arabidopsis. Plant Biotechnol J 7: 744–762 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Böttcher C, Westphal L, Schmotz C, Prade E, Scheel D, Glawischnig E. (2009) The multifunctional enzyme CYP71B15 (PHYTOALEXIN DEFICIENT3) converts cysteine-indole-3-acetonitrile to camalexin in the indole-3-acetonitrile metabolic network of Arabidopsis thaliana. Plant Cell 21: 1830–1845 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brodersen P, Petersen M, Bjørn Nielsen H, Zhu S, Newman MA, Shokat KM, Rietz S, Parker J, Mundy J. (2006) Arabidopsis MAP kinase 4 regulates salicylic acid- and jasmonic acid/ethylene-dependent responses via EDS1 and PAD4. Plant J 47: 532–546 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cao H, Bowling SA, Gordon AS, Dong X. (1994) Characterization of an Arabidopsis mutant that is nonresponsive to inducers of systemic acquired resistance. Plant Cell 6: 1583–1592 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cao H, Li X, Dong X. (1998) Generation of broad-spectrum disease resistance by overexpression of an essential regulatory gene in systemic acquired resistance. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 95: 6531–6536 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Colcombet J, Hirt H. (2008) Arabidopsis MAPKs: a complex signalling network involved in multiple biological processes. Biochem J 413: 217–226 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Conrath U. (2011) Molecular aspects of defence priming. Trends Plant Sci 16: 524–531 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Conrath U, Pieterse CM, Mauch-Mani B. (2002) Priming in plant-pathogen interactions. Trends Plant Sci 7: 210–216 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Conrath U, Silva H, Klessig DF. (1997) Protein dephosphorylation mediates salicylic-induced expression of PR-1 genes in tobacco. Plant J 11: 747–757 [Google Scholar]

- Cui H, Wang Y, Xue L, Chu J, Yan C, Fu J, Chen M, Innes RW, Zhou JM. (2010) Pseudomonas syringae effector protein AvrB perturbs Arabidopsis hormone signaling by activating MAP kinase 4. Cell Host Microbe 7: 164–175 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Daniel R, Guest D. (2006) Defence responses induced by potassium phosphonate in Phytophthora palmivora-challenged Arabidopsis thaliana. Physiol Mol Plant Pathol 67: 194–201 [Google Scholar]

- Danova-Alt R, Dijkema C, de Waard P, Köck M. (2008) Transport and compartmentation of phosphite in higher plant cells: kinetic and P nuclear magnetic resonance studies. Plant Cell Environ 31: 1510–1521 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Delaney TP, Uknes S, Vernooij B, Friedrich L, Weymann K, Negrotto D, Gaffney T, Gut-Rella M, Kessmann H, Ward E, et al. (1994) A central role of salicylic acid in plant disease resistance. Science 266: 1247–1250 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Desveaux D, Subramaniam R, Després C, Mess JN, Lévesque C, Fobert PR, Dangl JL, Brisson N. (2004) A “Whirly” transcription factor is required for salicylic acid-dependent disease resistance in Arabidopsis. Dev Cell 6: 229–240 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Durrant WE, Dong X. (2004) Systemic acquired resistance. Annu Rev Phytopathol 42: 185–209 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eshraghi L, Anderson J, Aryamanesh N, Shearer B, McComb J, Hardy GEStJ, O’Brien PA. (2011) Phosphite primed defence responses and enhanced expression of defence genes in Arabidopsis thaliana infected with Phytophthora cinnamomi. Plant Pathol 60: 1086–1095 [Google Scholar]

- Falk A, Feys BJ, Frost LN, Jones JD, Daniels MJ, Parker JE. (1999) EDS1, an essential component of R gene-mediated disease resistance in Arabidopsis has homology to eukaryotic lipases. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 96: 3292–3297 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fenn ME, Coffey MD. (1984) Studies on the in vitro and in vivo antifungal activity of Fosetyl-Al and phosphorus acid. Phytopathology 74: 606–611 [Google Scholar]

- Feys BJ, Moisan LJ, Newman MA, Parker JE. (2001) Direct interaction between the Arabidopsis disease resistance signaling proteins, EDS1 and PAD4. EMBO J 20: 5400–5411 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feys BJ, Wiermer M, Bhat RA, Moisan LJ, Medina-Escobar N, Neu C, Cabral A, Parker JE. (2005) Arabidopsis SENESCENCE-ASSOCIATED GENE101 stabilizes and signals within an ENHANCED DISEASE SUSCEPTIBILITY1 complex in plant innate immunity. Plant Cell 17: 2601–2613 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gao M, Liu J, Bi D, Zhang Z, Cheng F, Chen S, Zhang Y. (2008) MEKK1, MKK1/MKK2 and MPK4 function together in a mitogen-activated protein kinase cascade to regulate innate immunity in plants. Cell Res 18: 1190–1198 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Glawischnig E. (2007) Camalexin. Phytochemistry 68: 401–406 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Glazebrook J, Ausubel FM. (1994) Isolation of phytoalexin-deficient mutants of Arabidopsis thaliana and characterization of their interactions with bacterial pathogens. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 91: 8955–8959 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guest D, Bompeix G. (1990) The complex mode of action of phosphonates. Australas Plant Pathol 19: 113–115 [Google Scholar]

- Guest D, Grant B. (1991) The complex action of phosphonates as antifungal agents. Biol Rev Camb Philos Soc 66: 159–187 [Google Scholar]

- Guzmán P, Ecker JR. (1990) Exploiting the triple response of Arabidopsis to identify ethylene-related mutants. Plant Cell 2: 513–523 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heese A, Hann DR, Gimenez-Ibanez S, Jones AM, He K, Li J, Schroeder JI, Peck SC, Rathjen JP. (2007) The receptor-like kinase SERK3/BAK1 is a central regulator of innate immunity in plants. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 104: 12217–12222 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang Y, Li H, Gupta R, Morris PC, Luan S, Kieber JJ. (2000) ATMPK4, an Arabidopsis homolog of mitogen-activated protein kinase, is activated in vitro by AtMEK1 through threonine phosphorylation. Plant Physiol 122: 1301–1310 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ichimura K, Mizoguchi T, Irie K, Morris P, Giraudat J, Matsumoto K, Shinozaki K. (1998) Isolation of ATMEKK1 (a MAP kinase kinase kinase)-interacting proteins and analysis of a MAP kinase cascade in Arabidopsis. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 253: 532–543 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jaskiewicz M, Conrath U, Peterhänsel C. (2011) Chromatin modification acts as a memory for systemic acquired resistance in the plant stress response. EMBO Rep 12: 50–55 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jirage D, Tootle TL, Reuber TL, Frost LN, Feys BJ, Parker JE, Ausubel FM, Glazebrook J. (1999) Arabidopsis thaliana PAD4 encodes a lipase-like gene that is important for salicylic acid signaling. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 96: 13583–13588 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kai K, Mizutani M, Kawamura N, Yamamoto R, Tamai M, Yamaguchi H, Sakata K, Shimizu B. (2008) Scopoletin is biosynthesized via ortho-hydroxylation of feruloyl CoA by a 2-oxoglutarate-dependent dioxygenase in Arabidopsis thaliana. Plant J 55: 989–999 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Katz VA, Thulke OU, Conrath U. (1998) A benzothiadiazole primes parsley cells for augmented elicitation of defense responses. Plant Physiol 117: 1333–1339 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kauss H, Jeblick W. (1995) Pretreatment of parsley suspension cultures with salicylic acid enhances spontaneous and elicited production of H2O2. Plant Physiol 108: 1171–1178 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kauss H, Theisingerhinkel E, Mindermann R, Conrath U. (1992) Dichloroisonicotinic and salicylic acid, inducers of systemic acquired resistance, enhance fungal elicitor responses in parsley cells. Plant J 2: 655–660 [Google Scholar]

- Kohler A, Schwindling S, Conrath U. (2002) Benzothiadiazole-induced priming for potentiated responses to pathogen infection, wounding, and infiltration of water into leaves requires the NPR1/NIM1 gene in Arabidopsis. Plant Physiol 128: 1046–1056 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koornneef M, Jorna ML, Derswan D, Karssen CM. (1982) The isolation of abscisic acid (ABA) deficient mutants by selection of induced revertants in non-germinating gibberellin sensitive lines of Arabidopsis thaliana (L.) Heynh. Theor Appl Genet 61: 385–393 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kosetsu K, Matsunaga S, Nakagami H, Colcombet J, Sasabe M, Soyano T, Takahashi Y, Hirt H, Machida Y. (2010) The MAP kinase MPK4 is required for cytokinesis in Arabidopsis thaliana. Plant Cell 22: 3778–3790 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lobato MC, Olivieri FP, Daleo GR, Andreu AB. (2010) Antimicrobial activity of phosphites against different potato pathogens. J Plant Dis Prot 117: 102–109 [Google Scholar]

- McDowell JM, Cuzick A, Can C, Beynon J, Dangl JL, Holub EB. (2000) Downy mildew (Peronospora parasitica) resistance genes in Arabidopsis vary in functional requirements for NDR1, EDS1, NPR1 and salicylic acid accumulation. Plant J 22: 523–529 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Menke FL, van Pelt JA, Pieterse CM, Klessig DF. (2004) Silencing of the mitogen-activated protein kinase MPK6 compromises disease resistance in Arabidopsis. Plant Cell 16: 897–907 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mert-Türk F, Bennett MH, Mansfield JW, Holub EB. (2003) Camalexin accumulation in Arabidopsis thaliana following abiotic elicitation or inoculation with virulent or avirulent Hyaloperonospora parasitica. Physiol Mol Plant Pathol 62: 137–145 [Google Scholar]

- Misson J, Raghothama KG, Jain A, Jouhet J, Block MA, Bligny R, Ortet P, Creff A, Somerville S, Rolland N, et al. (2005) A genome-wide transcriptional analysis using Arabidopsis thaliana Affymetrix gene chips determined plant responses to phosphate deprivation. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 102: 11934–11939 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Molina A, Hunt MD, Ryals JA. (1998) Impaired fungicide activity in plants blocked in disease resistance signal transduction. Plant Cell 10: 1903–1914 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mur LAJ, Naylor G, Warner SAJ, Sugars JM, White RF, Draper J. (1996) Salicylic acid potentiates defence gene expression in tissue exhibiting acquired resistance to pathogen attack. Plant J 9: 559–571 [Google Scholar]

- Nakagami H, Pitzschke A, Hirt H. (2005) Emerging MAP kinase pathways in plant stress signalling. Trends Plant Sci 10: 339–346 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nawrath C, Métraux JP. (1999) Salicylic acid induction-deficient mutants of Arabidopsis express PR-2 and PR-5 and accumulate high levels of camalexin after pathogen inoculation. Plant Cell 11: 1393–1404 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nemestothy GS, Guest DI. (1990) Phytoalexin accumulation, phenylalanine ammonia lyase activity and ethylene biosynthesis in fosetyl-Al treated resistant and susceptible tobacco cultivars infected with Phytophthora nicotianae var. nicotianae. Physiol Mol Plant Pathol 37: 207–219 [Google Scholar]

- Niere JO, Deangelis G, Grant BR. (1994) The effect of phosphonate on the acid soluble phosphorus components in the genus Phytophthora. Microbiology 140: 1661–1670 [Google Scholar]

- Parker JE, Holub EB, Frost LN, Falk A, Gunn ND, Daniels MJ. (1996) Characterization of eds1, a mutation in Arabidopsis suppressing resistance to Peronospora parasitica specified by several different RPP genes. Plant Cell 8: 2033–2046 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peck SC. (2003) Early phosphorylation events in biotic stress. Curr Opin Plant Biol 6: 334–338 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Penninckx IA, Eggermont K, Terras FR, Thomma BP, De Samblanx GW, Buchala A, Métraux JP, Manners JM, Broekaert WF. (1996) Pathogen-induced systemic activation of a plant defensin gene in Arabidopsis follows a salicylic acid-independent pathway. Plant Cell 8: 2309–2323 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Petersen M, Brodersen P, Naested H, Andreasson E, Lindhart U, Johansen B, Nielsen HB, Lacy M, Austin MJ, Parker JE, et al. (2000) Arabidopsis MAP kinase 4 negatively regulates systemic acquired resistance. Cell 103: 1111–1120 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pitzschke A, Schikora A, Hirt H. (2009) MAPK cascade signalling networks in plant defence. Curr Opin Plant Biol 12: 421–426 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Qiu JL, Zhou L, Yun BW, Nielsen HB, Fiil BK, Petersen K, Mackinlay J, Loake GJ, Mundy J, Morris PC. (2008) Arabidopsis mitogen activated protein kinase kinases MKK1 and MKK2 have overlapping functions in defense signaling mediated by MEKK1, MPK4, and MKS1. Plant Physiol 148: 212–222 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rietz S, Stamm A, Malonek S, Wagner S, Becker D, Medina-Escobar N, Vlot AC, Feys BJ, Niefind K, Parker JE. (2011) Different roles of Enhanced Disease Susceptibility1 (EDS1) bound to and dissociated from Phytoalexin Deficient4 (PAD4) in Arabidopsis immunity. New Phytol 191: 107–119 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saindrenan P, Barchietto T, Bompeix G. (1988) Modification of the phosphite induced resistance response in leaves of cowpea infected with Phytophthora cryptogea by α-aminooxyacetate. Plant Sci 58: 245–252 [Google Scholar]

- Saindrenan P, Guest DI. (1994). Involvement of phytoalexins in the response of phosphonate-treated plants to infection by Phytophthora species. In M Daniel, RP Purkayastha, eds, Handbook of Phytoalexin Metabolism and Action. CRC Press, New York, pp 375–390 [Google Scholar]

- Schlaeppi K, Abou-Mansour E, Buchala A, Mauch F. (2010) Disease resistance of Arabidopsis to Phytophthora brassicae is established by the sequential action of indole glucosinolates and camalexin. Plant J 62: 840–851 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schmitz G, Reinhold T, Göbel C, Feussner I, Neuhaus HE, Conrath U. (2010) Limitation of nocturnal ATP import into chloroplasts seems to affect hormonal crosstalk, prime defense, and enhance disease resistance in Arabidopsis thaliana. Mol Plant Microbe Interact 23: 1584–1591 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schweighofer A, Kazanaviciute V, Scheikl E, Teige M, Doczi R, Hirt H, Schwanninger M, Kant M, Schuurink R, Mauch F, et al. (2007) The PP2C-type phosphatase AP2C1, which negatively regulates MPK4 and MPK6, modulates innate immunity, jasmonic acid, and ethylene levels in Arabidopsis. Plant Cell 19: 2213–2224 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Simon C, Langlois-Meurinne M, Bellvert F, Garmier M, Didierlaurent L, Massoud K, Chaouch S, Marie A, Bodo B, Kauffmann S, et al. (2010) The differential spatial distribution of secondary metabolites in Arabidopsis leaves reacting hypersensitively to Pseudomonas syringae pv. tomato is dependent on the oxidative burst. J Exp Bot 61: 3355–3370 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Slusarenko AJ, Schlaich NL. (2003) Downy mildew of Arabidopsis thaliana caused by Hyaloperonospora parasitica (formerly Peronospora parasitica). Mol Plant Pathol 4: 159–170 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Staswick PE, Tiryaki I, Rowe ML. (2002) Jasmonate response locus JAR1 and several related Arabidopsis genes encode enzymes of the firefly luciferase superfamily that show activity on jasmonic, salicylic, and indole-3-acetic acids in an assay for adenylation. Plant Cell 14: 1405–1415 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thibaud MC, Arrighi JF, Bayle V, Chiarenza S, Creff A, Bustos R, Paz-Ares J, Poirier Y, Nussaume L. (2010) Dissection of local and systemic transcriptional responses to phosphate starvation in Arabidopsis. Plant J 64: 775–789 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thomma BP, Eggermont K, Penninckx IA, Mauch-Mani B, Vogelsang R, Cammue BP, Broekaert WF. (1998) Separate jasmonate-dependent and salicylate-dependent defense-response pathways in Arabidopsis are essential for resistance to distinct microbial pathogens. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 95: 15107–15111 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ticconi CA, Delatorre CA, Abel S. (2001) Attenuation of phosphate starvation responses by phosphite in Arabidopsis. Plant Physiol 127: 963–972 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ton J, Flors V, Mauch-Mani B. (2009) The multifaceted role of ABA in disease resistance. Trends Plant Sci 14: 310–317 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ton J, Jakab G, Toquin V, Flors V, Iavicoli A, Maeder MN, Métraux JP, Mauch-Mani B. (2005) Dissecting the β-aminobutyric acid-induced priming phenomenon in Arabidopsis. Plant Cell 17: 987–999 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ton J, Mauch-Mani B. (2004) β-Amino-butyric acid-induced resistance against necrotrophic pathogens is based on ABA-dependent priming for callose. Plant J 38: 119–130 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Torres MA, Dangl JL, Jones JD. (2002) Arabidopsis gp91phox homologues AtrbohD and AtrbohF are required for accumulation of reactive oxygen intermediates in the plant defense response. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 99: 517–522 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ulm R, Ichimura K, Mizoguchi T, Peck SC, Zhu T, Wang X, Shinozaki K, Paszkowski J. (2002) Distinct regulation of salinity and genotoxic stress responses by Arabidopsis MAP kinase phosphatase 1. EMBO J 21: 6483–6493 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van der Biezen EA, Freddie CT, Kahn K, Parker JE, Jones JD. (2002) Arabidopsis RPP4 is a member of the RPP5 multigene family of TIR-NB-LRR genes and confers downy mildew resistance through multiple signalling components. Plant J 29: 439–451 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van Loon LC, Bakker PA, Pieterse CM. (1998) Systemic resistance induced by rhizosphere bacteria. Annu Rev Phytopathol 36: 453–483 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van Wees SC, de Swart EA, van Pelt JA, van Loon LC, Pieterse CM. (2000) Enhancement of induced disease resistance by simultaneous activation of salicylate- and jasmonate-dependent defense pathways in Arabidopsis thaliana. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 97: 8711–8716 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Varadarajan DK, Karthikeyan AS, Matilda PD, Raghothama KG. (2002) Phosphite, an analog of phosphate, suppresses the coordinated expression of genes under phosphate starvation. Plant Physiol 129: 1232–1240 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Verhagen BW, Glazebrook J, Zhu T, Chang HS, van Loon LC, Pieterse CM. (2004) The transcriptome of rhizobacteria-induced systemic resistance in Arabidopsis. Mol Plant Microbe Interact 17: 895–908 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wildermuth MC, Dewdney J, Wu G, Ausubel FM. (2001) Isochorismate synthase is required to synthesize salicylic acid for plant defence. Nature 414: 562–565 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang J, Shao F, Li Y, Cui H, Chen L, Li H, Zou Y, Long C, Lan L, Chai J, et al. (2007) A Pseudomonas syringae effector inactivates MAPKs to suppress PAMP-induced immunity in plants. Cell Host Microbe 1: 175–185 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang S, Yang X, Sun M, Sun F, Deng S, Dong H. (2009) Riboflavin-induced priming for pathogen defense in Arabidopsis thaliana. J Integr Plant Biol 51: 167–174 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zimmerli L, Jakab G, Métraux JP, Mauch-Mani B. (2000) Potentiation of pathogen-specific defense mechanisms in Arabidopsis by β-aminobutyric acid. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 97: 12920–12925 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zimmerli L, Métraux JP, Mauch-Mani B. (2001) β-Aminobutyric acid-induced protection of Arabidopsis against the necrotrophic fungus Botrytis cinerea. Plant Physiol 126: 517–523 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.