Abstract

Because of the growing concern that exposures to airborne pollutants have adverse effects on fetal growth and early childhood neurodevelopment, and the knowledge that such exposures are more prevalent in disadvantaged populations, we assessed the joint impact of prenatal exposure to environmental tobacco smoke (ETS) and material hardship on the 2-year cognitive development of inner-city children, adjusted for other sociodemographic risks and chemical exposures. The purpose was to evaluate the neurotoxicant effects of ETS among children experiencing different degrees of socioeconomic disadvantage, within a minority population. The sample did not include children exposed to active maternal smoking in the prenatal period. Results showed significant adverse effects of prenatal residential ETS exposure and the level of material hardship on 2-year cognitive development, as well as a significant interaction between material hardship and ETS, such that children with both ETS exposure and material hardship exhibited the greatest cognitive deficit. In addition, children with prenatal ETS exposure were twice as likely to be classified as significantly delayed, as compared with nonexposed children. Postnatal ETS exposure in the first 2 years of life did not contribute independently to the risk of developmental delay, over and above the risk posed by prenatal ETS exposure. The study concluded that prenatal exposure to ETS in the home has a negative impact on 2-year cognitive development, and this effect is exacerbated under conditions of material hardship in this urban minority sample.

Keywords: Environmental tobacco smoke, Material hardship, Neurodevelopment

1. Introduction

There is growing concern that exposures to ambient and indoor air pollutants have adverse effects on fetal growth and on early childhood neurodevelopment beyond the neonatal period [71]. Recent evidence suggests that such toxic exposures frequently occur in the context of multiple social disadvantages, many of which also impair child health and well-being [34,93]. Exposures to environmental tobacco smoke (ETS) and polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons (PAH), in particular, are high among low-income, urban and minority populations, both because of the uneven distribution of outdoor pollution sources [19,95] and the higher smoking rates in these populations [16,36,73,90,94]. Across the United States, 10 million children under the age of 6 years are exposed to residential ETS [1], including exposures in the homes of relatives and caregivers [40]. Elevated cotinine levels, indicative of ETS exposure, have been reported in 70–80% of inner-city children [92]. Furthermore, 60% of Hispanics and 50% of African Americans, compared with 33% of Caucasians, live in areas failing to meet two or more of the national ambient air quality standards [65,95]. These same minority populations are also more likely than others to experience poverty and a range of adversities that accompany poverty including substandard housing, poor nutrition, and inadequate health care [2,44,74]. In New York City, for example, it is estimated that 74% of the children in Central Harlem and 60% in Washington Heights live in fair to poor quality housing, as compared with 38% city wide [20].

ETS, a complex mixture of over 4000 chemicals including PAH and carbon monoxide [18,47], has been associated with reduced birth weight and length[48,58,59,75], preterm birth [101], fetal growth retardation (see, for review, Ref. [100]), and, in some studies, early cognitive functioning [29,54]. The PAH fraction of respirable particulate matter is also associated with growth and developmental deficits in infants. Specifically, transplacental exposure to PAH at relatively high concentrations (annual average airborne concentrations of 7–17 ng/m3 B[a]P in human studies) has been linked to decrements in head circumference and birth weight and length in highly exposed newborns [23,46,69,72,98]—decrements with potential longer term implications for lower cognitive functioning and school performance in childhood [35,51].

The consistent effects of adverse socioeconomic conditions on fetal and child neurodevelopment have been demonstrated in a range of populations [15,26], possibly mediated by nutrition, substance abuse, health service delivery, environmental agents, psychosocial stress [38, 52], or other health behavioral pathways [25]. Efforts to operationalize the hazards that accompany low income reveal considerable heterogeneity of material hardships and assets within low-income populations [56]. These conditions of daily living may mediate the adverse health and developmental effects of poverty [76], translating low income into illness and developmental delay. However, mechanisms underlying these pathways are not clear.

The co-occurrence and chronic nature of exposures to multiple chemical toxicants, as well as to socially adverse conditions, pose methodological challenges for risk assessment. In practice, few toxic exposures occur in isolation[18,47], and the unfavorable social conditions that underlie pollution typically generate many different kinds of environmental hazards, which tend to accumulate over time. For example, exposure to social stressors has been associated with increased rates of smoking [37]. Several studies have shown that the accumulation of multiple toxic exposures affects child development more strongly than any one specific exposure [9,67,93]. Similarly, child development studies indicate that the total number of social adversities predicts child intellectual functioning better than any single risk factor [79].

The present study evaluated the impact of prenatal exposure to residential ETS at three levels of material hardship in a predominantly low-income urban population, while adjusting for other toxicant exposures and social risk factors and excluding women who actively smoked during pregnancy. We tested the hypothesis that, after adjusting for other biomedical and demographic risks, prenatal exposure to ETS will negatively affect early child development and that adverse social conditions will exacerbate the harmful impact of ETS. We also assessed the contribution of postnatal ETS exposure to child cognitive functioning, beyond the effects of prenatal exposure.

2. Methods

2.1. Study participants

The participants for this report are 226 infants of Dominican and African American women residing in Washington Heights, Central Harlem, and the South Bronx, who delivered at New York Presbyterian Medical Center (NYPMC), Harlem Hospital (HH), or their satellite clinics, between 4/98 and 10/02, and enrolled in a cohort study concerning the impact of indoor and ambient pollutants undertaken by the Center for Children’s Environmental Health [69,70]. Ethnicity was based on self-identification. Only nonsmoking women (classified by self-report and validated by cotinine levels less than 25 ng/ml), aged 18–35, self-identified as African American or Dominican, and who registered at the OB/GYN clinics at NYPMC and HH by the 20th week of pregnancy were approached for consent to participate. Eligible women were free of diabetes, hyper-tension and known HIV, documented or reported drug or alcohol abuse, and had resided in the area for at least 1 year. Of 784 eligible consenting women, 593 completed the 48h antenatal personal air monitoring, and 507 completed all interviews and contributed a blood sample at the time of delivery. Of these, 236 had reached 24 months of age at the time of this report, and 226 had completed the data on all measures. The retention rate for the full cohort was 88% at the 2-year follow-up. There were no significant differences between women, in terms of maternal age, ethnicity, marital status, education, income, gestational age, or birth weight of the newborn, who were retained in the study versus those who were lost to follow-up. The study was approved by the Institutional Review Board of Columbia University, and informed consent was obtained from all participants.

2.2. Personal interview

A 45-min questionnaire was administered by a trained bilingual interviewer during the last trimester of pregnancy, at 6 months, 12 months, and 24 months postpartum. The content included socioeconomic and demographic information, residential history, living conditions during the current pregnancy (including housing quality and material hardship), history of exposure to active and passive smoking, alcohol, drugs, and PAH-containing foods (frequency of consumption of blackened meat, chicken, or fish). The questionnaire was based on one used in a prior study of women and newborns and adapted for the New York City population [72]. ETS exposure was measured by a set of questions about timing, frequency, and the amount of exposure to cigarette, cigar and pipe smoke in the home. High-, medium-, and low-exposure categories were collapsed into a dichotomous measure of self-reported ETS exposure, defined as present (coded 1) if the mother reported moderate or high exposure throughout pregnancy, or absent (coded 0) if the mother reported no exposure or very infrequent exposures in pregnancy. A measure of material hardship, originally developed by Mayer and Jencks [61], assessed the level of unmet basic needs in the areas of food, housing, and clothing. We defined material hardship as the total number of unmet basic needs, i.e., going without or having inadequate food, housing, or clothing at some point in the past year, each counted as one unmet need (0=no unmet needs, 1=one unmet need; 2=two or more unmet needs). Overall satisfaction with living conditions was self-assessed on a five-point scale ranging from very satisfied to very dissatisfied. The 27-item Psychiatric Epidemiology Research Instrument Demoralization Scale [28] was used to measure nonspecific psychological distress. It has been used with community samples as a measure of the total burden of stress [21,30,85] and, in relation to adverse environmental exposures [3,27], demonstrating high internal consistency reliability in white African American and Hispanic urban populations [88]. Maternal educational level at the time of the child’s second birthday was measured both continuously and dichotomously, using high school graduation and subsequent education or training as cut points. Prenatal alcohol consumption was assessed by a set of questions about frequency of ingesting an alcoholic drink in each trimester (<1/day, 1–2/day, 3–4/ day, ≥5/day); a drink being defined as 12 oz. beer, 5 oz. wine, or 2 oz. hard alcohol or mixed drink. High exposure was defined as ≥5 drinks per day in any trimester, moderate exposure was defined as <5 drinks per day but ≥1 drink per day, and low exposure was defined as <1 drink per day in any trimester.

2.3. Prenatal personal air monitoring

During the third trimester of pregnancy, the women were asked to wear a small backpack containing a personal monitor during the daytime hours for two consecutive days and to place the monitor near the bed at night. The personal air sampling pumps operated continuously over this period, collecting vapors and particles of ≤2.5 Am in diameter on a precleaned quartz microfiber filter and a precleaned polyurethane foam (PUF) cartridge backup. The samples were analyzed at the Southwest Research Institute (SwRI) for eight carcinogenic PAH: benz(a)anthracene, chrysene, benzo(b)-fluroanthene, benzo(k)fluroanthene, B[a]P, indeno(1,2,3-cd)pyrene, disbenz(a,h)anthracene, and benzo(g,h,i)perylene as, described by Majumdar et al. [53] and Whyatt et al.[96,97]. To determine whether the participants complied with the requests to carry backpacks equipped with environmental monitoring devices, motion detectors were installed in the backpacks of randomly selected women. For the average woman, nearly 95% of the total number of motion detections occurred during the waking hours, consistent with the verbal reports of our participants that they were complying with our request to wear the backpacks during daytime hours over the environmental monitoring period. For quality control, each personal monitoring result was coded as to the accuracy in flow rate, time, and completeness of documentation. In addition, each personal air monitoring for PAH was checked for insufficient/unstable flow or leak, based on the use of a rotometer, and then coded as to the accuracy in flow rate, time, and completeness of documentation. A code of 0–1 indicated high quality, 2 intermediate quality, and 3 indicated unacceptable quality. We restricted the analysis to participants with high quality samples. Five samples had a QA score of 3 (unusable data) and 22 had a QA score of 2 (problematic data), resulting in the exclusion of 27 samples (or 27 women) from the sample.

As reported previously, the study cohort has substantial exposure to multiple airborne contaminants during pregnancy [70,97]. Specifically, almost half of the mothers and infants had cotinine levels indicative of ETS exposure (>0.025–25.00 ng/ml). The analysis of PAH in air samples from the first 250 pregnant women showed that all samples had detectable levels of one or more carcinogenic PAH, ranging over four orders of magnitude [70].

2.4. Biologic sample collection and analysis

Maternal blood (30–35 ml) was collected within one day postpartum, and umbilical cord blood (30–60 ml) was collected at delivery. The samples were immediately transported to the laboratory, where buffy coat, packed red blood cells, and plasma samples were separated and stored at —70°C. A portion of each sample was shipped to the Centers for Disease Control (CDC) for an analysis of plasma cotinine, using high-performance liquid chromatography atmospheric-pressure ionization tandem mass spectrometry [11]. The maternal and cord plasma concentrations of cotinine were significantly correlated (r=.88, P<0.001). The lead in the umbilical cord blood was analyzed by Zeeman graphite furnace atomic absorption spectrometry, using a phosphate/ Triton X-100/nitric acid matrix modifier.

2.5. Measures of fetal growth and child neurodevelopment

Gestational age, birth weight and length, and head circumference data were abstracted from the maternal and infant medical records by trained research workers. The Bayley Scales of Infant Intelligence [4] were used to assess cognitive development at 24 months of age. Each child was tested by a bilingual research assistant, trained and checked for reliability, under controlled conditions at the Children’s Center offices. Each scale provides a developmental quotient (raw score/chronological age), which generates a mental development index (MDI) and a corresponding psychomotor development index (PDI); only the results of the MDI were used for the present report. The Bayley scales were selected because of their widespread use, good psychometric properties, and increasingly accurate prediction for assessments made in the 2-year period, particularly for children performing in the subnormal range [39]. In addition, the Bayley scales have been shown to be sensitive to the effects of toxic exposures such as low-level intrauterine lead [6]. In the present study, the interrater reliability for the 24-month MDI was r =.92, based on double scoring of a random 5% of the sample. For the present report, in addition to the continuous MDI score, we also used the standardized cut point to classify children as significantly delayed (<80).

2.6. Statistical analysis

Chi-square analysis and logistic regression of self-reported ETS exposure on cotinine assay levels were used as tests of association for biological verification of the ETS measure. Because the eight PAH air concentration measures were significantly intercorrelated (r values ranging from .50 to .92; all P values <0.001 by Spearman’s rank), a composite PAH variable was computed and log (ln)-transformed to approximate the normal distribution. Intrauterine lead levels (umbilical cord blood samples) ranged from nondetectable to 7.6 μdl, with a mean of 1.209 μg/dl, and were log (ln)-transformed to approximate the normal distribution. Analysis of variance and chi-square analysis were used to evaluate the construct validity of the material-hardship measure. The stability of the socioeconomic indicators over time was determined by correlational analysis. The relationship between exposures and cognitive development was analyzed by multiple linear regression (for predicting continuous developmental scores) and logistic regression (for predicting risk of significant developmental delay), adjusted for known or potential confounders, and included all tests of 2-way interactions between exposures and sociodemographic conditions. The hardship measure was categorized into high/ low hardships for inclusion in multivariate tests of interactions with ETS. The criteria for selection of confounders were based on significant associations with either of the toxicant exposures (ETS or PAH) and cognitive development. Additional biomedical and demographic variables that were significantly associated with cognitive development in the present sample were included as covariates to reduce the error term.

2.7. Validation of measures

All women who self-reported a moderate or high exposure to ETS in the home during pregnancy were classified as ETS exposed. Of these, 72.8% screened positive for detectable levels of cotinine in the maternal or cord blood at the time of delivery (between 0.0250 and 25 ng/ml), indicating that they had been exposed to secondhand smoke within 48 h of delivery. Although we employed the most sensitive assay method currently available for the analysis of serum cotinine [11], cotinine is only a short-term dosimeter of ETS exposure and does not assess exposure throughout pregnancy [22,24,43,90]. Nevertheless, the association between self-reported ETS exposure and the cotinine assay in the present sample was highly significant (χ2=48.57, P<0.001). Table 1 shows the steady increase in proportion of self-reported ETS, with an increasing level of the cotinine assay distribution (the lowest level includes all women with non-detectable assays). The association between ETS and cotinine levels was significant and of comparable magnitude for both African American (χ2=26.89, P<0.001) and Hispanic women (χ2=19.16, P<0.001). In addition to the dichotomous measure of prenatal ETS exposure, mothers also reported the number of smokers in the home. As a further check on the validity of self-reported ETS, the association between the number of smokers in the home (0, 1, 2 or more) and the cotinine assay level was tested. Although fewer than 10% of the women reported more than one smoker in the home, the association was positive and significant overall (χ2=55.34, P<0.001), among African American (χ2=25.21, P<0.001), and among Hispanic women (χ2=24.60, P<0.001), further supporting the validity of self-report in this sample. Since self-report methods tend to under, rather than over, report ETS exposure, resulting in the classification of some true ETS-exposed women as unexposed [24], any potential bias, if present, would result in an underestimation of ETS effects.

Table 1.

Self-reported environmental tobacco smoke exposure by level of cord cotinine at delivery

| Cotinine level (ng/ml) |

Self-reported prenatal ETS exposure (% within cotinine level) |

n | |

|---|---|---|---|

| ETS No (%) | ETS Yes (%) | ||

| 1sta: ≤.0250 | 74.2 | 25.8 | 132 |

| 2nd: >.0250, ≤.0920 | 69.8 | 30.2 | 63 |

| 3rd: >.0920, ≤.3170 | 62.5 | 37.5 | 64 |

| 4th: >.3170, ≤25.00 | 23.8 | 76.2 | 63 |

| χ2=48.57, P<0.0001 | |||

Includes all women with nondetectable cotinine values (<0.0250 ng/ml).

The construct validity of material hardship in the present population was assessed using measures of poverty, satisfaction/dissatisfaction with living conditions (five-point scale, ranging from very satisfied to very dissatisfied), and the Psychiatric Epidemiologic Research Instrument Demoralization Scale, a standardized measure of nonspecific psychological distress, which has been used in a number of previous studies of stressful living conditions (e.g., Refs. [27,28]). Consistent with the literature linking psychological distress with measures of SES, the regression of demoralization on hardships showed that, after adjusting for income and race/ethnicity, the total number of hardships was significantly and positively associated with demoralization ( P<0.001). Chi-square analysis showed that the degree of dissatisfaction with living conditions was also significantly and positively associated with the level of material hardship (χ2=55.74, P<0.001). Based on the cross-sectional correlations between the measures of demoralization, poverty, and material hardships and the autocorrelations for each measure from pregnancy through the second postpartum year (see Table 2), we concluded that (1) material hardship was moderately, not highly, associated with poverty [r values ranged from .08 (NS) to .2, P<0.001], and associations were strongest at the same time point (all P values < 0.001); (2) material hardship was relatively stable over time, as indicated by the significant correlations of repeated measures from pregnancy through the child’s second year (rs ranged from .24 to .42, all P values <0.001); (3) psychological distress was a function of material hardship (all P values <0.001) to a greater degree than it was related to the income measure of poverty (rs ranged from .05 to .27, some P values <0.001), suggesting that some of the conditions that accompany poverty may be more important determinants of maternal adjustment than income alone.

Table 2.

Unadjusted associationsa between material hardships, income, and psychological distress

| Condition | Material hardshipsb |

Psychological distressc |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Prenatal | 12 months |

24 months |

Prenatal | 12 months |

24 months |

|

| Material Hardships (four-point scale, 0 – 3) | ||||||

| Prenatal | 1.00** | .42** | .24** | .35** | .30** | .30** |

| 12 months | – | 1.00** | .39** | .25** | .36** | .36** |

| 24 months | – | – | 1.00** | .24** | .40** | .45** |

| Psychological distress | ||||||

| Prenatal | – | – | – | 1.00** | .60** | .60** |

| 12 months | – | – | – | – | 1.00** | .70** |

| 24 months | – | – | – | – | – | 1.00** |

| Annual income (≤US$10,000, >US$10,000) | ||||||

| Prenatal | .21** | .11 | .08 | .05 | .09 | .07 |

| 12 months | .24** | .22** | .17* | .26** | .27** | .17* |

| 24 months | .19* | .16* | .24** | .07 | .17* | .09 |

Pearson correlation for continuous scales; Spearman for categorical scales.

Total unmet basic needs in the areas of food, housing, and clothing.

Demoralization Scale from the Psychiatric Epidemiology Research Instrument (Ref. [28]).

P<0.01.

P<0.001.

3. Results

Prenatal ETS exposure in the home was highly prevalent, occurring in 40.2% of the children with 24-month Bayley scores. Detectable inhalation levels of one or more PAH were found in 100% of the sample (total PAH exposures averaged 3.62 ng/m3, range=0.27 to 36.47 ng/m3), while regular ingestion of dietary PAH (via charred foods) was uncommon (4.9%). Umbilical cord lead levels ranged from nondetectable to 7.6 μdl, with a mean of 1.275 μdl, and were not significantly associated with prenatal ETS. One or more material hardships were reported by 37.7% of the women during pregnancy, 27.3% during the first postpartum year, 22.7% during the second postpartum year, and 9.2% at all three assessments. Regular alcohol ingestion in pregnancy was reported by only 2.1% of the sample. As shown in Table 3, prenatal ETS exposure was significantly associated with a number of demographic variables, such that the prevalence of self-reported ETS exposure was higher among African Americans (χ2=5.24, P<0.05), unmarried women (χ2=4.30, P<0.05), younger women ( F=7.44, P<0.01), and those with lower income (χ2=7.28, P<0.01). Prenatal exposures to ambient and dietary PAH were not significantly associated with ETS exposure. Postnatal ETS exposure over the first 2 years of life was reported by 37.6% of the mothers (n=85), both pre- and postnatal exposure was reported by 26.5% (n=60), and 11.1% (n=25) had postnatal ETS exposure only.

Table 3.

Characteristics of the study population by ETS exposure (N=226)

| Characteristic | Prenatal environmental tobacco smoke exposure level |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Exposed (n=91) |

Unexposed (n=135) |

P value | |||

| % | Mean (S.D.) | % | Mean (S.D.) | ||

| Maternal Characteristics | |||||

| Ethnicity | |||||

| African American | 49.0 | 51.0 | |||

| Latino | 33.8 | 66.2 | <0.05 | ||

| Annual income <US$10,000 |

53.6 | 38.1 | <0.01 | ||

| Age (years) | 23.62 (05.0) |

25.22 (4.98) |

<0.01 | ||

| Primiparous | 55.2 | 46.2 | |||

| Married | 17.1 | 28.1 | <0.05 | ||

| Psychological distress scorea |

30.78 19.0) |

28.95 (16.4) |

NS | ||

| More than 12 years of education |

23.8 | 33.2 | =0.07 | ||

| One or more material hardshipsb |

24.8 | 21.3 | NS | ||

| Prenatal | 39.5 | 36.0 | NS | ||

| 12 months | 28.2 | 25.9 | NS | ||

| 24 months | 24.4 | 21.2 | NS | ||

| Infant characteristics | |||||

| Birthweight (grams) |

3355.8 (491.5) |

3416.2 (487.6) |

NS | ||

| Birth length (cm) |

50.67 (2.49) |

51.00 (2.83) |

NS | ||

| Birth head circumference (cm) |

33.94 (1.47) |

34.21 (1.51) |

NS | ||

| 5-min Apgar (%≥9) |

86.6 | 90.9 | NS | ||

| Gestational age (weeks) |

39.34 (1.30) |

39.36 (1.53) |

NS | ||

| Male | 50.0 | 47.4 | NS | ||

| Birth complications (5-min Apgar) |

8.90 (0.44) |

8.95 (0.50) |

NS | ||

| Age at 24-month testing (weeks) |

24.46 (1.52) |

24.47 (1.28) |

NS | ||

| 24-Month Bayley Mental Development Score (MDI) |

82.02 (13.0) |

86.61 (12.3) |

<0.01 | ||

| Developmentally delayed (<80 on MDI) |

41.9 | 25.9 | <0.01 | ||

| Exposures | |||||

| Airborn PAHc (ng/m3) |

3.66 (3.04) |

3.51 (4.03) |

NS | ||

| Dietary PAH (charred food) |

4.9 | 4.9 | NS | ||

| Cord blood lead (μg/dl) |

1.39 (1.17) |

1.19 (0.81) |

NS | ||

| Postnatal ETSd | 65.9 | 18.5 | <0.001 | ||

| Alcohol consumption (beer, wine, or liquor)e |

1.8 | 2.3 | NS | ||

Notes to Table 3:

Psychiatric epidemiology research instrument; 27-item scale; Dohrewend et al. ([28]).

Total unmet needs in areas of food, housing, clothing, characterized into high=1 and low=0.

Natural log total PAH.

Defined as any ETS in the home in first 2 years; yes=1; no=0.

Defined as ≥one drink per day throughout pregnancy (includes high and moderate exposure).

3.1. Predictors of 2-year MDI

The overall mean 24-month MDI Bayley score was 84.31 (S.D.=12.91), and African American children had significantly higher mean MDI scores (mean=87.55; S.D.=12.31) than Dominican children (mean=82.77; S.D.=12.68; P<0.01). The lower scores on the Bayley scales by the Dominican children were largely a function of failed language items, possibly related to bilingual practices in the home. The proportion of children with significant delay (MDI<80) was 32.3% overall (27.3% of African Americans and 36.1% of Dominicans).

The mean unadjusted 2-year cognitive development score of the children who were exposed to prenatal ETS (mean =82.02; S.D.=13.01) was significantly lower than the mean score for children who were not exposed (mean=86.61; S.D.=12.30; F=7.41, P=0.007). Total number of material hardships in the postpartum period was significantly associated with 24-month development ( P<0.05) and income (χ2=13.658, P<0.05), but not significantly associated with race/ethnicity, marital status, maternal education, or ETS exposure. The significant associations of race, marital status, and maternal educational level with both ETS exposure and 2-year cognitive scores identified these demographic variables as true confounders of the ETS–cognitive development relationship, and they were included in all subsequent multivariate models. Extreme poverty (<US$10,000 per year) was significantly associated with ETS exposure ( P<0.01), but not with 24-month development. Gender was significantly associated with MDI (F=5.703, P= 0.002), such that girls scored significantly higher than boys (mean=87.52, S.D.=12.17 vs. mean=81.63, S.D.=12.85, respectively; P<0.001). The age of administration of the Bayley test (measured in weeks) was also significantly associated with continuous cognitive score ( P<0.001) and developmental delay ( P<0.001), suggesting that the test is sensitive to relatively small changes in maturation around the 24-month period, with substantial variability at the low end of the range. Gestational age was significantly associated with MDI (r =.13, P<0.05) despite the computation of the standardized Bayley scores based on the birthdate, adjusted for gestational age. Gender, gestational age, and infant age at test administration together accounted for 11.1% of the variance in the 24-month cognitive scores and were included as covariates. The reported frequency of dietary PAH (ingestion of blackened or charred foods) was low (only 4.9% of the sample reported ingestion of any blackened food at any time during pregnancy, and no participants reported frequent ingestion throughout pregnancy) and was not significantly associated with either airborne exposures or cognitive outcome. Cord blood lead was not significantly associated with airborne exposures or cognitive outcome.

Although the lead levels were low in this sample (mean=1.25 μdl), lead was included in subsequent multivariate analyses because a threshold has not been established for lead neurotoxicity, and because of possible synergistic effects of lead with ETS and PAH. Maternal alcohol consumption during pregnancy was not a significant predictor of cognitive development, in part, because the women with alcohol abuse were not included in the sample. Airborne PAH was not significantly associated with 24-month MDI, but was retained in subsequent multivariate analyses because it was associated with birth weight in this population [69] and others [72], and, hence, is an exposure of interest. Although PAH is a constituent of ETS, in the present sample, there were no significant differences in mean PAH for ETS-exposed as compared with unexposed participants (see Table 3), nor was there a significant association between prenatal PAH exposure and cord blood cotinine. These observations suggest that no significant amounts of emissions from nearby cigarettes were measured during our PAH monitoring.

3.2. Multivariate analyses

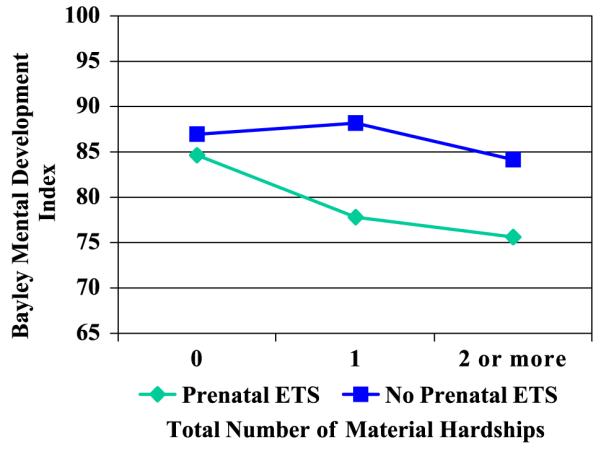

To assess the impact of ETS on 24-month child cognitive development, while adjusting for confounders and covariates (including other chemical exposures), linear regression models were constructed. Multivariate results are presented in Table 4, where Model 1 includes only main effects and Model 2 tests the significance of interaction term(s). In Model 1, the main effect of ETS was highly significant (P=0.005), such that exposure was associated with a 4.8-point deficit in cognitive score. Maternal education/training beyond high school (>12 years) was significantly associated with cognitive development, and a married status was positively associated, with borderline significance (P= 0.099). The total number of material hardships was negatively, yet only marginally, associated with MDI (P=0.064). The main adverse effect of ETS remains significant when material hardship is included in the model, suggesting that both risk factors contribute independently to cognitive deficit. In Model 2, the interaction between ETS and material hardship was tested and found to be significant, such that the adverse impact of prenatal ETS exposure on child development was greater among children whose mothers reported greater material hardship (P=0.03), resulting in a cognitive deficit of approximately seven points. Fig. 1 illustrates this interaction by showing the adjusted mean MDI scores at three levels of material hardship for ETS-exposed and unexposed children.

Table 4.

Regression models testing main and interactive effects of prenatal ETS, and material hardships on 24-month Bayley Cognitive Development Score, adjusted for race, gender, marital status, maternal age, PAH, and age at test administration in an inner-city minority sample (N=226)

| Variable | Model 1: No interaction |

Model 2: Interaction |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| B | S.E. | P value | B | S.E. | P value | |

| Prenatal chemical exposures | ||||||

| ETSa | −4.777 | 1.58 | 0.003 | −2.647 | 1.86 | 0.155 |

| Airborn PAHb | 0.824 | 1.12 | 0.492 | 0.799 | 1.11 | 0.517 |

| Leadc | 1.061 | 1.06 | 0.317 | 0.984 | 1.05 | 0.350 |

| Covariates | ||||||

| Race/Ethnicityd | 6.518 | 1.71 | <0.001 | 6.488 | 1.69 | <0.001 |

| Gendere | −6.457 | 1.54 | <0.001 | −6.551 | 1.53 | <0.001 |

| Gestational age (weeks) |

1.599 | 0.53 | 0.003 | 1.560 | 0.53 | 0.004 |

| Age at test administration |

1.212 | 0.48 | 0.013 | 1.195 | 0.48 | 0.014 |

| Maternal educationf |

3.329 | 1.63 | 0.042 | 3.138 | 1.62 | 0.054 |

| Marriedg | 3.322 | 1.75 | 0.099 | 3.545 | 1.73 | 0.042 |

| Material hardshiph | −3.230 | 1.74 | 0.064 | −0.421 | 2.17 | 0.846 |

| Interaction term: | −7.116 | 3.33 | 0.034 | |||

| Material | ||||||

| Hardship× ETS | ||||||

| R2 | .250 | .266 | ||||

Prenatally exposed=1; Not exposed=0.

Natural log total PAH.

Natural log cord blood lead.

African American=1; Hispanic=0.

Male=1; Female=0.

Additional education/training beyond the high school degree: <HS=1; ≤HS=0.

Married=1; Unmarried=0.

Total unmet needs in areas of food, housing, clothing; categorized into high=1 and low=0.

Fig. 1.

Regression of 24-month cognitive development on parenatal ETS exposure, by level of material hardship (n=226). (The regression was adjusted for race/ethnicity, gender gestational age at delivery, age at testing, marital status, maternal age, and level of PAH exposure.)

aAdjusted for race/ethnicity, gender, gestational age at delivery, age at testing, marital status, maternal age, and level of PAH exposure.

Although African American children scored significantly higher on the measure of cognitive development as compared with Latino children (P<0.001), there were no race/ethnic group differences in effect sizes for ETS, material hardships, or the ETS-material hardship interaction (all tests of interactions with race were nonsignificant). There were no other significant interactions of exposure variables with demographic factors or material hardships, nor were there any significant interactions among the exposure variables. Since PAH is one of the constituents of ETS, the finding that airborne PAH is not significant in the full model suggests that the ETS effect on cognitive development is not explained by the contribution of airborne PAH.

An additional model was run, including a term for postnatal ETS exposure (over the first two years of life), to assess the impact of postnatal ETS exposure on cognitive development, over and above the prenatal effect. In this sample, 65.9% of the mothers with prenatal ETS exposure reported continued smoking exposure in the home during the first 2 years of life, a potentially vulnerable period. Postnatal exposure did not significantly contribute to 24-month development, after controlling for prenatal exposure, and the postnatal term was not included in the final model. Since postnatal ETS, in the absence of prenatal ETS, was reported by only 11.1% of mothers, no additional analyses were done to test the effects of postnatal ETS exposure in the absence of prenatal exposure.

To determine whether the impact of ETS and the significance of the interaction term were mediated or explained by fetal growth parameters, all regression models were rerun, including the terms for birth weight, birth length, and head circumference. No fetal growth parameter effect was significant, and the inclusion of each of these parameters in separate models did not substantially alter the magnitude or significance of the ETS exposure term or the ETS-hardship interaction term.

Table 5 shows the results of a logistic regression analysis, evaluating the impact of exposures and covariates on the risk of developmental delay (<80 on the Bayley). The main effect of ETS was again significant (OR=2.36; 95% CI=1.22, 4.48), such that children with ETS exposure were more than twice as likely to show developmental delay as compared with unexposed children (Model 1). As seen in Model 2, the interaction of ETS and material hardships just missed significance at the .05 level.

Table 5.

Logistic regression models testing effects of ETS and material hardship on the odds of developmental delay at 24 months of age, adjusted for race, gender, marital status, maternal age, PAH, and age at test administration in an inner-city minority sample (N=226)

| Variable | Dependent variable: Significant delay (MDI <80) |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Model 1: Main effects |

Model 2: Interaction |

|||

| Odds ratio | 95% C.I. | Odds ratio | 95% C.I. | |

| Prenatal chemical exposures | ||||

| ETSa | 2.364 | 1.22, 4.58 | 1.610 | 0.73, 3.57 |

| Airborn PAHb | 0.942 | 0.59, 1.50 | 0.956 | 0.60, 1.52 |

| Leadc | 0.918 | 0.59, 1.43 | 0.948 | 0.60, 1.49 |

| Covariates | ||||

| Race/Ethnicityd | 0.485 | 0.23, 1.02 | 0.497 | 0.24, 1.04 |

| Gendere | 3.608 | 1.89, 6.90 | 3.783 | 1.96, 7.31 |

| Gestational age (weeks) |

0.867 | 0.70, 1.08 | 0.874 | 0.71, 1.09 |

| Age at test administration |

0.594 | 0.59, 0.99 | 0.765 | 0.59, 0.99 |

| Maternal educationf |

0.725 | 0.36, 1.45 | 0.746 | 0.37, 1.50 |

| Marriedg | 0.447 | 0.21, 0.97 | 0.417 | 0.19, 0.92 |

| Material hardshiph | 1.886 | 0.93, 3.81 | 1.136 | 0.45, 2.89 |

| Interaction term: | 3.254 | 0.82, 12.98 | ||

| Material | ||||

| Hardship×ETS | ||||

Prenatally exposed=1; Not exposed=0.

Natural log total PAH.

Natural log cord blood lead.

African American=1; Hispanic=0.

Male=1; Female=0.

Additional education/training beyond the high school degree: >HS=1; ≤HS=0.

Married=1; Unmarried=0.

Total unmet needs in areas of food, housing, clothing; categorized into high=1 and low=0.

3.3. Further exploration of the interaction between ETS and material hardship

The interaction effect was not explained by a higher likelihood of ETS exposure among women experiencing greater hardships; that is, the association between material hardship level and ETS exposure was nonsignificant (χ2=0.14, P=0.70). However, the interaction might occur if ETS-exposed women who reported high numbers of hardships actually experienced higher doses of residential ETS (e.g., more smokers or greater frequency of smoking behavior in the home), resulting in greater deficits in child cognitive development. There is some evidence in the literature that smoking practices among the more economically disadvantaged individuals involve more cigarettes [37], as compared with smoking practices among less disadvantaged individuals [14]. To rule out this possible explanation for the statistical interaction, we analyzed two biomarkers of exposure, maternal or fetal cotinine (short-term dosimeter) and cord 4-aminobiphenyl-hemoglobin adducts (longer term dosimeter than cotinine, available for a subset of women), in ETS-exposed individuals at different hardship levels. Among the 91 ETS-exposed women (whose children completed the 24-month Bayley), mean cotinine levels did not vary significantly by level of material hardship: 0.15 ng/ml (S.D.=.22) for high-hardship versus 0.53 ng/ml (S.D.=1.35) for low-hardship households. In a subset of 71 women with 4-ABP-Hb adducts, mean levels of adducts were not significantly different in the two hardship groups: 10.93 pg/g (S.D.=6.98) for the high-hardship group versus 10.60 pg/g (S.D.=7.09) for the low-hardship group. The lack of significant group differences by hardship level for either biomarker suggests that the significant interaction between ETS and hardships was not explained by higher dosage of ETS among ETS-exposed women in the more materially disadvantaged households.

4. Discussion

The finding of a significant negative association between prenatal ETS exposure in the home and 24-month child cognitive development provides evidence for a developmentally toxic effect of maternal exposure to secondhand smoke during pregnancy. The adjusted mean mental development score for infants who were prenatally exposed was approximately five points below the unexposed group mean, and those infants with prenatal ETS exposure were twice as likely to be classified as significantly delayed when compared with infants with no prenatal ETS exposure, after adjustment for confounders and covariates.

The main effect of ETS exposure on 2-year developmental scores was detected when exposure occurred prenatally. Additional exposure during the first two postnatal years, after controlling for prenatal exposure, was not associated with significantly lower developmental scores, nor did it add significantly to the risk of developmental delay. The number of children with postnatal ETS exposure, in the absence of prenatal ETS exposure, was small (n=25) and included children who were exposed at any time during the first 2 years of life, limiting our ability to further explore the possible impact of postnatal ETS.

The adverse impact of fetal exposure to ETS may be due to the diverse mechanisms exerted by the many ETS constituents such as the alteration of receptor-mediated cell signaling in the brain [83], antiestrogenic effects [17], induction of P450 enzymes [55], DNA damage resulting in activation of apoptotic pathways [68,102], and/or agents that bind to receptors for placental growth factors, resulting in decreased exchange of oxygen and nutrients [23]. Although previous findings showed a significant association between prenatal ETS exposure and head circumference at the time of birth [69], head circumference was not predictive of cognitive development at 24 months of age, and there was no evidence that the ETS effect on cognitive development was mediated by any fetal growth parameter. The lead literature has also demonstrated that the adverse neurocogntive effects of low-level exposures may appear at various ages as the child develops, with or without mediating effects of birth weight and length or head circumference[6,67,99].

The finding that children who were exposed to both prenatal ETS and material hardship scored, on average, 7.1 points lower on the Bayley MDI as compared with those with neither ETS nor hardship is provocative, but should be interpreted cautiously. It is possible that ETS is equally toxic under conditions of low and high hardship, but that low-hardship families have extra resources in the form of stimulation or positive parent–child interactions that enable the children to compensate for the adverse ETS effects, as has been shown in the lead literature. A limitation of the present analysis is the failure to measure the possible compensatory effects of family resources and supports.

As is the case with lead, ETS is only one of a multitude of influences on neurobehavioral development [42], making it difficult to detect true ETS-related decrements in populations where developmental risks are widespread [9].It is therefore possible that material hardship, as defined in this study, is merely a marker for exposure to other unmeasured toxicants [97], so that the apparent interaction with ETS reflects a biological synergism with other contaminants (e.g., drugs, pesticides, volatile organic chemicals, and other unmeasured ambient air pollutants). Mattson et al. [60] found that prenatal exposure to active maternal smoking strengthened (or increased the power to detect) the negative effects of intrauterine exposure to benzodiazepines on child cognitive development. Eyler et al. [31] reported significant interactive effects of prenatal active smoking and cocaine exposure on neurodevelopment. Although mechanisms may differ by class of teratogenic agent, the importance of considering the joint impact of ETS exposure with other intrauterine exposures, rather than simply controlling for the effects of one or the other, cannot be overstated. Given the high number of pollutants and other potentially toxic exposures in urban settings [34,45], the comorbidity of ETS and other neurotoxicants deserves further study[49,83].

Another possible explanation for the apparent interaction effect is that those children exposed to both prenatal ETS and conditions of material hardship may share a third common risk factor for adverse child developmental outcome: poor maternal dietary practices. Several studies have reported that active smoking among pregnant women is associated with lower intake of micronutrients and lower quality diet [57,84]. Rogers et al. [76] also reported significant differences in the types of food habitually eaten by smoking as compared with nonsmoking pregnant women, with smokers reporting a higher fat diet. Although a relationship between exposure to secondhand smoke and dietary practices has not been established, it is possible that members of smoking households share common dietary practices as a result of shared resources.

Not surprisingly, several population-based surveys have found a link between hardship and dietary practices, such that financial hardships are associated with lower quality diets, especially intakes of iron, folic acid, and micronutrients [13,76,82]. This suggests that the level of difficulty affording basic necessities, as measured by material hardship in the present study, may be a general indicator of the impact of poverty on diet. Deficient diets (among those who report having gone without food) may be characterized by lower intake of essential micronutrients (e.g., antioxidants, essential fatty acid), with implications for fetal growth and child development [12,89,102]. These reports lend support to the idea that adverse developmental effects of ETS exposure may be compounded by dietary deficits. But again, the specific biological mechanisms underlying such interactions have yet to be explored. In the present sample, co-exposure to both ETS and material hardship may be a marker for the most extreme dietary deficiencies, resulting in the greatest neurodevelopmental deficits in this group.

Evidence in the literature for the moderating effects of the social environment on prenatal toxicant effects is inconsistent, in part, because of differences in the definition and assessment of the social environment [8]. In the present study, material hardship likely serves as a marker for multiple economic and psychosocial disadvantages, any one of which might be considered a risk factor for aberrant child development. Some of the pathways by which socioeconomic disadvantage may affect child health and development have been extensively reviewed elsewhere [2]. The finding of a strong relationship between material hardship and psychological distress is consistent with other studies (e.g., Ref. [50]). Although maternal distress did not appear to have a mediational role in this population (no direct association between distress and cognitive development, and no reduction in the magnitude of the hardship effect with distress in the model), maternal distress is undoubtedly an important part of the caretaking environment and may play a role in the modulation of the prenatal toxicant effect, as seen for example in the cocaine literature [32].

With respect to toxicant effect modification by aspects of the social environment, Sadler et al. [78] have reported that prenatal ETS exposure was associated with small size-for-gestational-age only among low-income women, with no ETS effect for the higher income group. Weiss [93] compares the effects of lead toxicity in advantaged and disadvantaged communities and demonstrates how, while harmful lead effects may appear to be stronger among more socioeconomically advantaged children [8,80], the actual number of children added to the developmentally delayed category, as a result of lead exposure, is far greater (and more costly) in less advantaged populations. Jacobson and Jacobson [41] found that breast-fed children were less vulnerable to the adverse cognitive effects of prenatal consumption of PCBs, possibly because of higher quality parenting. They also found that the adverse neurobehavioral effects of prenatal PCB exposure were stronger among children with less verbal mothers. Other studies have reported a modulation of the teratogenic effects of antenatal cocaine exposure on a range of neurobehavioral outcomes by social factors [31] such as public assistance, multiparity [5], and caregiving or early intervention [32].

Such interactions may reflect a kind of cumulative risk whereby children who are exposed prenatally to single or multiple neurotoxicants are rendered more susceptible to the developmental challenges posed by deprivation and/or stressful living conditions in the early years of life [86]. In the present sample, material hardships may not be well-tolerated by children who have been prenatally exposed to chemical toxicants. Mayes [62] provides a relevant behavioral teratogenic model, in which prenatal cocaine exposure affects arousal regulatory mechanisms, resulting in the young child’s vulnerability to environments characterized by impaired parenting and other social stressors. According to this model, the adaptation to challenging situations depends on an individual’s threshold for activation of the catecholamine and norepinephrin arousal system, and this threshold may be impaired by the prenatal toxicant exposure. The ability to modulate arousal is a critical skill, with wide-ranging implications for development [10]. Animal models have also shown that prenatal and early postnatal exposure to nicotine can modulate catecholamine gene expression or neuroendocrine regulation [33,81], and recent evidence from animal and human studies has shown that maternal stress may mediate associations between socioeconomic adversity and early childhood cognition [52,63,64]. This model suggests that it may be important to identify early caretaking conditions that are developmentally protective, such that some children, despite prenatal toxicant exposure, are able to compensate and enjoy a more optimal developmental trajectory. In the present study, children with older and/or married mothers had slightly higher developmental scores, possibly indicating the protective or compensatory effect of more stable homes. Mechanisms underlying the exacerbation or amelioration of neurotoxicant effects by social conditions await further study.

While the adjusted mean MDI scores of the ETS-exposed and unexposed groups differed by only five points, the proportion of children in the ETS-exposed group with cognitive scores <80 was two times greater than among the unexposed children. This suggests that twice as many exposed children may need (and are eligible for) early intervention services, an intervention designed for children who are at potential risk for early school failure. The stability of cognitive assessments during the first few years of life is limited, yet, the predictive power increases after two years, suggesting that children with MDI <80 at 24 months are potentially at risk for performance deficits (language, reading, and math) in the early school years. A comparison of studies of the long-term cognitive effects of active versus passive smoking in pregnancy on children’s neurobehavioral functioning indicates that ETS has smaller effects than active smoking, suggesting a continuum of effects with possible dose-response characteristics ([54; see, for review, Ref. [94]. Despite the dilution of ETS exposure, there is some evidence that certain toxic chemical constituents of tobacco smoke are higher in sidestream as compared with mainstream smoke, possibly boosting their neurotoxic impact [66]. The magnitude of the ETS effect on early cognitive development in this study is comparable with low-level lead exposure effects [80] ranging from 3.4 to 6.6 points, depending upon pre- or postnatal exposure assessment [91,99], dietary factors [77], and length of follow-up [6,7].

According to a recent report by the Surgeon General, smoking is “the most important modifiable cause of poor pregnancy outcome among women in the United States” [87], with serious implications for subsequent neurobehavioral development. The present results suggest that cautions against antenatal maternal smoking should be extended to include fetal exposure to secondhand smoke. In this predominantly low-income minority population, especially among those with high material hardship/deprivation, even a small increase in risk associated with ETS exposure was sufficient to move significant numbers of children into the developmentally delayed range, resulting in a greater need for early intervention services and, perhaps, special education classes in the early school years. Although the educational disadvantages experienced by children in northern Manhattan are undoubtedly multiply determined, residential tobacco smoke exposure does appear to be a source of significant, highly prevalent, and largely preventable risk for child cognitive delay in this population.

Acknowledgements

We gratefully acknowledge the contributions of Darrell Holmes, Mejico Borjas, Judy Ramirez, Yesenia Cosme, Susan Illman, and Eric Evans from Columbia University; Larry Needham and Richard Jackson from CDC; the OBGYN staffs at Harlem Hospital, Allen Pavillion, and New York-Presbyterian Hospital; and the laboratory work of Xinhe Jin, Lirong Qu, and Jing Lai, under the direction of Dr. Deliang Tang. Grant Support was provided by the National Institute of Environmental Health Sciences (NIEHS; 5P01 ES09600, 5 RO1 ES08977, RO1ES111158, RO1 ES012468), the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency (EPA; R827027, 8260901), Irving General Clinical Research Center (RR00645), Bauman Family Foundation, Gladys and Roland Harriman Foundation, Hansen Foundation, W. Alton Jones Foundation, New York Community Trust, Educational Foundation of America, The New York Times Company Foundation, Rockefeller Financial Services, Horace W. Smith Foundation, Beldon Fund, The John Merck Fund, September 11th Fund of the United Way and New York Community Trust, The New York Times 9/11 Neediest Fund, and V. Kann Rasmussen Foundation.

References

- [1].ACS (American Cancer Society) Cancer Facts and Figures, 2001. National Media Office; New York, NY: 2001. Cancer Facts and Figures. ACS (American Cancer Society) [Google Scholar]

- [2].Adler NE, Marmot M, McEwen BS, Stewart J, editors. Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences. vol. 896. New York Academy of Sciences; New York, NY: 1999. Socioeconomic Status and Health in Industrial Nations: Social, Psychological and Biological Pathways. [Google Scholar]

- [3].Bachrach KM. Coping with a community stressor: the threat of a hazardous waste facility. J. Health Soc. Behav. 1985;26:127–141. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [4].Bayley N, editor. The Psychological. 2nd Edition San Antonio, TX: 1993. Bayley Scales of Infant Development. [Google Scholar]

- [5].Beeghly M, Frank DA, Rose-Jacobs R, Cabral H, Tronic E. Level of prenatal cocaine exposure and infant – caregiver attachment behavior. Neurotoxicol. Teratol. 2003;25:23–38. doi: 10.1016/s0892-0362(02)00323-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [6].Bellinger D, Leviton A, Waternaux C, Needleman H, Rabinowitz M. Longitudinal analyses of pre- and postnatal lead exposure and early cognitive development. N. Engl. J. Med. 1987;316:1037–1044. doi: 10.1056/NEJM198704233161701. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [7].Bellinger D, Sloman J, Leviton A, Rabinowitz M, Needleman HL, Waternaux C. Low-level lead exposure and children’s cognitive function in the preschool years. Pediatrics. 1991;87:219–227. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [8].Bellinger DC. Effect modification in epidemiologic studies of low-level neurotoxicant exposures and health outcomes. Neurotoxicol. Teratol. 2000;22(1):133–140. doi: 10.1016/s0892-0362(99)00053-7. (review) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [9].Bellinger DC, Stiles KM. Epidemiologic approaches to assessing the developmental toxicity of lead. Neurotoxicology. 1993;14:151–160. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [10].Bendersky M, Lewis M. Arousal modulation in cocaine-exposed infants. Dev. Psychol. 1998;43:555–564. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [11].Bernert JT, Turner WE, Pirkle JL, Sosnoff CS, Akins JR, Waldrep MK, et al. Development and validation of sensitive method for determination of serum cotinine in smokers and nonsmokers by liquid chromatography/atmospheric pressure ionization tandem mass spec-trometry. Clin. Chem. 1997;43:2281–2291. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [12].Bjerve KS, Brubakk AM, Fougner KJ, Johnsen H, Midthjell K, Vik T. Omega-3 fatty acids: essential fatty acids with important biological effects, and serum phospholipid fatty acids as markers of dietary omega-3 fatty acid intake. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 1993;57(Suppl. 5):801S–805S. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/57.5.801S. (discussion 805S–806S. 1993) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [13].Block G, Abrams B. Vitamin and mineral status of women of child-bearing potential. Ann. N.Y. Acad. Sci. 1993;678:244–254. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.1993.tb26126.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [14].Bobak M. Outdoor air pollution, low birth weight, and prematurity. Environ. Health Perspect. 2000;108:173–176. doi: 10.1289/ehp.00108173. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [15].Bradley RH, Corwyn RR. Socioeconomic status and child development. Annu. Rev. Psychol. 2002;53:371–399. doi: 10.1146/annurev.psych.53.100901.135233. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [16].Brownson RC, Figgs LW, Caisley LE. Epidemiology of environmental tobacco smoke exposure. Oncogene. 2002;21(48):7341–7348. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1205809. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [17].Bui QQ, Tran MB, West WL. A comparative study of the reproductive effects of methadone and benzo(a)pyrene in the pregnant and pseudopregnant rat. Toxicology. 1986;42:195–204. doi: 10.1016/0300-483x(86)90009-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [18].Centers for Disease Control Cigarette smoking among adults—United States, 2000. MMWR. 2002;51(29):642–645. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [19].Chuang JC, Callahan PJ, Lyu CW, Wilson NK. Polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbon exposures in low-income families. J. Exp. Anal. Environ. Epidemiol. 1999;9(2):85–98. doi: 10.1038/sj.jea.7500003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [20].Citizen’s Committee for Children of New York Inc. Keeping Track of New York City’s Children. 5th ed NY: 1999. [Google Scholar]

- [21].Cohen P. Community stressors, mediating conditions and well-being in urban neighborhoods. J. Commun. Psychol. 1982;10(4):377–391. doi: 10.1002/1520-6629(198210)10:4<377::aid-jcop2290100408>3.0.co;2-t. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [22].Crawford FG, Mayer J, Santella RM, Cooper T, Ottman R, Simon-Cereijido WY, Simon-Cereijido G, Wang M, Tang D, Perera FP. Biomarkers of environmental tobacco smoke in preschool children and their mothers. J. Natl. Cancer Inst. 1994;(86):1398–1402. doi: 10.1093/jnci/86.18.1398. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [23].Dejmek J, Solansky I, Benes I, Lenicek J, Sram RJ. The impact of polycylic aromatic hydrocarbons and fine particles on pregnancy outcome. Environ. Health Perspect. 2000;108:1159–1164. doi: 10.1289/ehp.001081159. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [24].DeLorenze GN, Kharrazi M, Kaufman FL, Eskenazi B, Bernert JT. Exposure to environmental tobacco smoke in pregnant women: the association between self-report and serum cotinine. Environ. Res., Sect. A. 2002;90:21–32. doi: 10.1006/enrs.2001.4380. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [25].DiPietro JA. Baby and the brain: advances in child development. Annu. Rev. Publ. Health. 2000;21:455–471. doi: 10.1146/annurev.publhealth.21.1.455. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [26].DiPietro JA, Costigan KA, Shupe AK, Pressman EK, Johnson TRB. Fetal neurobehavioral development: associations with socioeconomic class and fetal sex. Dev. Psychobiol. 1998;33:79–91. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [27].Dohrenwend BP. Stress in the community: a report to the president’s commission on the accident at three mile island. Ann. N.Y. Acad. Sci. 1981;365:159–174. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.1981.tb18129.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [28].Dohrenwend BS, Krasnoff L, Askenacy A, et al. Exemplification of a method for scaling life events: the PERI life events scale. J. Health Soc. Behav. 1978;19:205–229. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [29].Eskenazi B, Castorina R. Association of prenatal maternal or post-natal child environmental tobacco smoke exposure and neurodevelop-mental and behavioral problems in children. Environ. Health Perspect. 1999;107(12):991–1000. doi: 10.1289/ehp.99107991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [30].Evans GW, Palsane MN, Lepore SJ, Martin J. Residential density and psychological health: the mediating effects of social support. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 1989;57:994–999. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.57.6.994. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [31].Eyler FD, Behnke M, Conlon NS, Woods K. Birth outcome from a prospective, matched study of prenatal crack/cocaine use: interactive and dose effects on health and growth. Pediatrics. 1998;101:229–237. doi: 10.1542/peds.101.2.229. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [32].Frank DA, Jacobs RR, Beeghly M, Augustyn M, Bellinger D, Cabral H, Heeren T. Level of prenatal cocaine exposure and scores on the Bayley Scales of Infant Development: modifying effects of care-giver, early intervention, and birth weight. Pediatrics. 2002;110:1143–1152. doi: 10.1542/peds.110.6.1143. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [33].Gauda EB, Cooper R, Akins PK, Wu G. Prenatal nicotine affects catecholamine gene expression in newborn rat carotid body and petrosal ganglion. J. Appl. Physiol. 2001;91(5):2157–2165. doi: 10.1152/jappl.2001.91.5.2157. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [34].Guillette EA. Examining childhood development in contaminated urban settings. Environ. Health Perspect. 2000;108(Suppl. 3):389–393. doi: 10.1289/ehp.00108s3389. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [35].Hack M, Breslau N, Weissman B, Aram D, Klein N, Borawski E. Effect of very low birth weight and subnormal head size on cognitive ability at school age. N. Engl. J. Med. 1991;325:231–237. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199107253250403. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [36].Heritage J. Environmental protection—has it been fair? EPA. 1992:18. [Google Scholar]

- [37].Heslop P, Smith G. Davey, Carroll D, et al. Perceived stress and coronary heart disease risk factors: the contribution of socio-economic position. Br. J. Health Psychol. 2001;6:167–168. doi: 10.1348/135910701169133. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [38].Hoffman S, Hatch MC. Stress, social support and pregnancy outcome: a reassessment based on recent research. Paediatr. Perinat. Epidemiol. 1996;10:380–405. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-3016.1996.tb00063.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [39].Honzik MP. Advances in Infancy Research. vol. 5. Elsevier/JAI Press Inc.; USA: 1988. The constancy of mental test performance during the preschool period; pp. xv–xxxi. [Google Scholar]

- [40].Hopper JA, Craig KA. Environmental tobacco smoke among urban children. Pediatrics. 2000;106(4):47. doi: 10.1542/peds.106.4.e47. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [41].Jacobson JL, Jacobson SW. Breast-feeding and gender as moderators of teratogenic effects on cognitive development. Neurotoxicol. Teratol. 2002;24:349–358. doi: 10.1016/s0892-0362(02)00197-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [42].Jacobson SW, Fein GG, Jacobson JL, Schwartz PM, Dowler JK. Neonatal correlates of prenatal exposure to smoking, caffeine, and alcohol. Infant Behav. Dev. 1984;7(3):253–265. [Google Scholar]

- [43].Jedrychowski W, Whyatt R, Cooper T, Flak E, Perera F. Exposure misclassification error in studies on prenatal effects of tobacco smoking in pregnancy and the birth weight of children. J. Exp. Anal. Environ. Epidemiol. 1998;8(3):347–357. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [44].Kahn AJ, Kamerman SB, editors. Beyond Child Poverty: The Social Exclusion of Children. Institute for Child and Family Policy at Columbia University; New York, NY: 2002. [Google Scholar]

- [45].Landrigan PJ, Schechter CB, Lipton JM, Fahs MC, Schwartz J. Environmental pollutants and disease in American children: estimates of morbidity, mortality, and costs for lead poisoning, asthma, cancer, and developmental disabilities. Environ. Health Perspect. 2002;110(7):721–728. doi: 10.1289/ehp.02110721. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [46].Legraverend C, Guenthner TM, Nebert DW. Importance of the route of administration for genetic differences in benzo(a)pyrene-induced in utero toxicity and teratogenicity. Teratology. 1984;29:35–47. doi: 10.1002/tera.1420290106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [47].Lewtas J. Human exposure to complex mixtures of air pollutants. Toxicol. Lett. 1994;72:163–169. doi: 10.1016/0378-4274(94)90024-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [48].Leslie GB, Fave A. Effects of environmental tobacco smoke on prenatal development. J. Toxicol. Clin. Exp. 1992;12:155–177. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [49].Lester BM, Tronick E, Lagasse LL, Seifer R, Bauer CR, Shankaran S, Bada HS, Wright LL, Smiriglio VL, Finnegan LP, Maza PL. The maternal lifestyle study (MLS): effects of substance exposure during pregnancy on one-month neurodevelopmental outcome. Pediatrics. 2002;110:1182–1192. doi: 10.1542/peds.110.6.1182. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [50].Linares LO, Heeren T, Bronfman E, Zuckerman B, Augustyn M, Tronick E. A mediational model for the impact of exposure to community violence on early child behavior problems. Child Dev. 2001;72(2):639–652. doi: 10.1111/1467-8624.00302. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [51].Lucas A, Morley R, Lister G, Leeson-Payne C. Effect of very low birth weight on cognitive abilities at school age. N. Engl. J. Med. 1992;326:202–203. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199201163260313. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [52].Lupien SJ, King S, Meaney MJ, McEwen BS. Can poverty get under your skin? Basal cortisol levels and cognitive function in children from low and high socioeconomic status. Dev. Psychopathol. 2001;13(3):653–676. doi: 10.1017/s0954579401003133. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [53].Majumdar TK, Camann DE, Geno PW. Analytical method for the screening of pesticides and polynuclear aromatic hydrocarbons from house dust. A&WMA Publication. 1993;34:685–690. [Google Scholar]

- [54].Makin J, Fried PA, Watkinson B. A comparison of active and passive smoking during pregnancy: long-term effects. Neurotoxicol. Teratol. 1991;13(1):5–12. doi: 10.1016/0892-0362(91)90021-n. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [55].Manchester DK, Gordon SK, Golas CL, Roberts EA, Okey AB. Ah receptor in human placenta: stabilization by molybdate and characterization of binding of 2,3,7,8-tetrachlorodibenzo-p-dioxin, 3-methylcholanthrene, and benzo(a)pyrene. Cancer Res. 1987;47:4861–4868. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [56].Manfredi C, Lacey L, Warnecke R, Buis M. Smoking-related behavior, beliefs and social environment of young black women in subsidized public housing in Chicago. AJPH. 1992;82:267–272. doi: 10.2105/ajph.82.2.267. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [57].Margetts BM, Jackson AA. Interactions between people’s diet and their smoking habits: the dietary and nutritional survey of British adults. BMJ. 1993;307:1381–1384. doi: 10.1136/bmj.307.6916.1381. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [58].Martin TR, Bracken MB. Association of low birth weight with passive smoke exposure in pregnancy. Am. J. Epidemiol. 1986;124:633–642. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a114436. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [59].Martinez FD, Wright AL, Taussig LM. The effect of paternal smoking on the birthweight of newborns whose mothers did not smoke. Am. J. Public Health. 1994;84:1489–1491. doi: 10.2105/ajph.84.9.1489. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [60].Mattson SN, Calarco KE, Chambers CD, Jones K. Lyons. Interaction of maternal smoking and other in-pregnancy exposures: analytic considerations. Neurotoxicol. Teratol. 2002;24:359–367. doi: 10.1016/s0892-0362(02)00198-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [61].Mayer S, Jencks C. Poverty and the distribution of material hardship. J. Hum. Resour. 1988:88–112. [Google Scholar]

- [62].Mayes LC. A behavioral teratogenic model of the impact of prenatal cocaine exposure on arousal regulatory systems. Neurotoxicol. Teratol. 2002;24:385–395. doi: 10.1016/s0892-0362(02)00200-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [63].McEwen BS. Protective and damaging effects of stress mediators. N. Engl. J. Med. 1998;338(3):171–179. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199801153380307. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [64].McEwen BS, Stellar E. Stress and the individual: mechanisms leading to disease. Arch. Intern. Med. 1992;153:2093–2101. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [65].Metzer R, Delgado JL, Herrell R. Environmental health and Hispanic children. Environ. Health Perspect. 1995;103:25–32. doi: 10.1289/ehp.95103s625. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [66].National Research Council . Environmental Tobacco Smoke, Measuring Exposures and Assessing Health Effects. National Academy Press; Washington, DC: 1986. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [67].Needleman HL, Gatsonis CA. Low level lead exposure and the IQ of children: a meta-analysis of modern studies. JAMA. 1990;263:673–678. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [68].Nicol CJ, Harrison ML, Laposa RR, Gimelshtein IL, Wells PG. A teratologic suppressor role for p53 in benzo[a]pyrene-treated transgenic p53-deficient mice. Nat. Genet. 1995;10:181–187. doi: 10.1038/ng0695-181. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [69].Perera F, Rauh VA, Tsai WY, Kinney P, Camann D, Barr D, Bernert T, Garfinkel R, Tu YH, Diaz D, Dietrich J, Whyatt RM. Effects of transplacental exposure to environmental pollutants on birth outcomes in a multi-ethnic population. Environ. Health Perspect. 2003;111(2):201–205. doi: 10.1289/ehp.5742. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [70].Perera FP, Illman SM, Kinney PL, Whyatt RM, Kelvin EA, Shepard P, Evans D, Fullilove M, Ford J, Millere RL, Meyer IH, Rauh VA. The challenge of preventing environmentally related disease in young children: community-based research in New York City. Environ. Health Perspect. 2002;110:197–204. doi: 10.1289/ehp.02110197. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [71].Perera FP, Whyatt R, Rauh V, Jedrychowski W. Molecular epidemiologic research on the effects of environmental pollutants on the fetus. Environ. Health Perspect. 1999;107:451–460. doi: 10.1289/ehp.99107s3451. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [72].Perera FP, Whyatt RM, Jedrychowski W, Rauh V, Manchester D, Santella RM, et al. Recent developments in molecular epidemiology: a study of the effects of environmental polycylic aromatic hyrdrocarbons on birth outcomes in Poland. Am. J. Epidemiol. 1998;147:309–3014. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a009451. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [73].Pirkle JL, Flegal KM, Bernert JT, Brody DJ, Etzel RA, Maurer KR. Exposure of the US population to environmental tobacco smoke: the Third National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey, 1988 to 1991. JAMA. 1996;275:1233–1240. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [74].Polednak AP. Segregation, Poverty and Mortality in Urban African Americans. Oxford Univ. Press; New York: 1997. [Google Scholar]

- [75].Rebagliato M, Florey C.d.V., Bolumar F. Exposure to environmental tobacco smoke in nonsmoking pregnant women in relation to birth weight. Am. J. Epidemiol. 1995;142:531–537. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a117671. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [76].Rogers I, Emmett P, Baker D, J. Goldingthe ALSPAC Study Team Financial difficulties, smoking habits, composition of the diet and birthweight in a population of pregnant women in the South West of England. Eur. J. Clin. Nutr. 1998;52:251–260. doi: 10.1038/sj.ejcn.1600544. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [77].Ruff HA, Markowitz M, Bijur PE, Rosen JF. Relationships among blood lead levels, iron deficiency, and cognitive development in two-year-old children. Environ. Health Perspect. 1996;104(2):180–185. doi: 10.1289/ehp.96104180. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [78].Sadler L, Belanger K, Saftlas A, Leaderer B, Hellenbrand K, Mcsharry JE, Bracken MB. Environmental tobacco smoke exposure and small-for-gestational-age birth. Am. J. Epidemiol. 1999;150(7):695–705. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a010072. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [79].Sameroff AJ, Seifer R, Bartko WT. Environmental perspectives on adaptation during childhood and adolescence. In: Luthar SS, Burack JA, Cicchetti D, Weisz JR, editors. Developmental Psychopathology, Perspectives on Adjustment, Risk and Disorder. Cambridge Univ. Press; Cambridge, UK: 1997. pp. 507–526. [Google Scholar]

- [80].Schwartz J. Low-level lead and children’s I.Q.: a meta-analysis and search for a threshold. Environ. Res. 1994;65:42–55. doi: 10.1006/enrs.1994.1020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [81].Serova L, Danailov E, Chamas F, Sabban EL. Nicotine infusion modulates immobilization stress-triggered induction of gene expression of rat catecholamine iosynthetic enzymes. J. Pharmacol. Exp. Ther. 1999;291(2):884–892. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [82].Simon JA, Schreiber GB, Crawford PB, Frederick MM, Sabry ZI. Income and racial patterns of dietary vitamin C among black and white girls. Public Health Rep. 1993;108:760–764. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [83].Slotkin TA. Fetal nicotine or cocaine exposure: which one is worse? J. Pharmacol. Exp. Ther. 1998;285:931–945. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [84].Thornton A, Lee P, Fry J. Differences between smokers, ex-smokers, passive smokers and non-smokers. J. Clin. Epidemiol. 1994;47:1143–1162. doi: 10.1016/0895-4356(94)90101-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [85].Travis R, Velasco SC. Social structure and psychological distressamong blacks and whites in America. Soc. Sci. J. 1994;31(2):197–201. [Google Scholar]

- [86].Tronick EZ, Beeghley M. Prenatal cocaine exposure, child development and the compromising effects of cumulative risk. Clin. Perinatol. 1999;26:151–171. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [87].U.S. Department of Health and Human Services . Women and Smoking: A report of the Surgeon General. U.S. D.H.H.S, Public Health Service, Centers for Disease Control, Center for Chronic Disease Prevention and Health Promotion, Office on Smoking and Health; Rockville, MD: 2001. A report of the surgeon general. [Google Scholar]

- [88].Vernon S, Roberts RE. Measuring nonspecific psychological distress and other dimensions of psychopathology; further observations on the problem. Arch. Gen. Psychiatry. 1981;38(11):1239–1247. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1981.01780360055005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [89].Voigt RG, Jensen CL, Fraley JK, Rozelle JC, Brown FR, III, Heird WC. Relationship between omega3 long-chain polyunsaturated fatty acid status during early infancy and neurodevelopmental status at 1 year of age. J. Hum. Nutr. Diet. 2002;15(2):111–120. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-277x.2002.00341.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [90].Wagenknecht LE, Manolio TA, Sidney S, Burke GL, Haley NJ. Environmental tobacco smoke exposure as determined by cotinine in black and white young adults: the CARDIA study. Environ. Res. 1993;63:39–46. doi: 10.1006/enrs.1993.1124. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [91].Wasserman GA, Liu X, Popovac D, Factor-Litvak P, Kline J, Waternaux C, LoIacono N, Graziano JH. The Yugoslavia prospective lead study: contributions of prenatal and postnatal lead exposure to early intelligence. Neurotoxicol. Teratol. 2000;22:811–818. doi: 10.1016/s0892-0362(00)00106-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [92].Weaver VM, Davoli CT, Murphy SE, Sunyer J, Heller PJ, Colosiano SG, Groopman JD. Environmental tobacco smoke exposure in inner-city children. Cancer Epidemiol. Biomark. Prev. 1996;5:135–137. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [93].Weiss B. Vulnerability of children and the developing brain to neurotoxic hazards. Environ. Health Perspect. 2000;108(Suppl. 3):375–381. doi: 10.1289/ehp.00108s3375. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [94].Weitzman M, Byrd RS, Aligne A, Moss M. The effects of tobacco exposure on children’s behavioral and cognitive functioning: implications for clinical and public health policy and future research. Neurotoxicol. Teratol. 2002;24:397–406. doi: 10.1016/s0892-0362(02)00201-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [95].Wernette DR, Nieves LA. Breathing polluted air: minority disproportionately exposed. EPA J. 1992;18:16–17. [Google Scholar]

- [96].Whyatt RM, Bell DA, Jedrychowski W, Santella RM, Garte SJ, Cosma G, Manchester DK, Young TL, Cooper TB, Ottman R, Perera FP. Polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbon-DNA adducts in human placenta and modulation by CYP1A1 induction and genotype. Carcinogenesis. 1998;19(8):1389–1392. doi: 10.1093/carcin/19.8.1389. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [97].Whyatt RM, Camann DE, Kinney PL, Reyes A, Ramirez J, Dietrich J, Diaz D, Holmes D, Perera FP. Residential pesticide use during pregnancy among a cohort of urban minority women. Environ. Health Perspect. 2002;110:507–514. doi: 10.1289/ehp.02110507. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [98].Whyatt RM, Jedrychowski W, Garte SJ, Bell DA, Ottman R, Gladek-Yarborough A, Cosma G, Young TL, Cooper TB. Relationship between ambient air pollution and procarcinogenic DNA damage in Polish mothers and newborns. Environ. Health Perspect. 1998;106(Suppl. 3):821–826. doi: 10.1289/ehp.98106821. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]