SUMMARY

Active genes in yeast can be targeted to the nuclear periphery through interaction of cis-acting “DNA zip codes” with the nuclear pore complex. We find that genes with identical zip codes cluster together. This clustering was specific; pairs of genes that were targeted to the nuclear periphery by different zip codes did not cluster together. Insertion of two different zip codes (GRS I or GRS III) at an ectopic site induced clustering with endogenous genes having that zip code. Targeting to the nuclear periphery and interaction with the nuclear pore is a pre-requisite for gene clustering, but clustering can be maintained in the nucleoplasm. Finally, we find that the Put3 transcription factor recognizes the GRS I zip code to mediate both targeting to the NPC and interchromosomal clustering. These results suggest that zip code-mediated clustering of genes at the nuclear periphery influences the three-dimensional arrangement of the yeast genome.

INTRODUCTION

The nucleus is spatially organized. Chromosomes fold, occupy distinct “territories” and interact with stable nuclear structures such as the nuclear lamina and the nuclear envelope (Meldi and Brickner, 2011). Furthermore, the position of individual genes within the nucleus can both reflect and impact their expression; co-regulated genes can cluster together and physically interact to promote either expression or silencing (Brown et al., 2008; Brown et al., 2006; Schoenfelder et al., 2010). The co-localization of active, co-regulated genes has been proposed to occur at “transcription factories” and to promote the efficient recruitment of factors involved in their expression (Iborra et al., 1996; Schoenfelder et al., 2010; Xu and Cook, 2008a). However, the molecular mechanisms controlling gene positioning and clustering are still unclear.

As a model for these phenomena, we have studied the targeting of genes to the nuclear periphery upon activation (Brickner, 2009; Egecioglu and Brickner, 2011; Taddei, 2007). In yeast, many inducible genes, including GAL1, GAL2, INO1, HSP104 and TSA2, are targeted from the nucleoplasm to the nuclear periphery upon activation (Ahmed et al., 2010; Brickner and Walter, 2004; Cabal et al., 2006; Casolari et al., 2005; Casolari et al., 2004; Dieppois et al., 2006). Targeting is mediated by physical interaction of the promoters of these genes with the nuclear pore complex (NPC) and results in their constrained diffusion along the nuclear envelope (Ahmed et al., 2010; Cabal et al., 2006; Light et al., 2010; Luthra et al., 2007; Schmid et al., 2006). Targeting to the NPC promotes stronger transcription of these genes (Ahmed et al., 2010; Brickner et al., 2007; Brickner and Walter, 2004; Menon et al., 2005; Taddei et al., 2006). A similar phenomenon has been reported in Drosophila; interaction of nuclear pore proteins with genes promotes their transcription (Capelson et al., 2010; Kalverda et al., 2010). However, in Drosophila, many of these genes interact with nuclear pore proteins in the nucleoplasm, away from the NPC (Capelson et al., 2010; Kalverda et al., 2010).

Within the promoters of INO1 and TSA2, we have identified DNA elements that are necessary for targeting to the nuclear periphery and interaction with the NPC (Ahmed et al., 2010; Light et al., 2010). Importantly, these elements are distinct from the known Upstream Activating Sequences (UASs) that control transcription of these genes. These elements function as DNA zip codes: they are sufficient, when introduced at an ectopic locus, to induce targeting to the nuclear periphery (Ahmed et al., 2010; Light et al., 2010). These results suggest that the spatial organization of the genome is, to some extent, encoded in the DNA and that the utilization of positional information in the DNA can be regulated (Ahmed and Brickner, 2010).

To explore the role of DNA zip codes and interaction with the NPC in affecting the spatial organization of the genome, we asked if zip codes could cause an ectopic locus to co-localize with the endogenous gene. Here we show that endogenous genes with identical DNA zip codes cluster together, whereas genes with different zip codes do not. Two zip codes from different promoters (GRS I or GRS III), when inserted at an ectopic location, induce co-localization with the endogenous genes having these zip codes. Finally, GRS I-mediated clustering requires interaction with the Put3 transcription factor and interaction with the NPC. These results suggest that DNA zip codes can induce gene clustering at the nuclear envelope that has global effects on the spatial organization of the genome.

RESULTS

INO1 is targeted to a restricted portion of the nuclear envelope

We first asked if the INO1 gene was localized to the nuclear envelope generally or to a restricted portion of the nuclear envelope. Previous work localizing genes with respect to stable subnuclear structures found that genes in the yeast nucleus localized to restricted subnuclear “territories” (Berger et al., 2008). Using this high-resolution statistical mapping approach, we mapped the location of the INO1 gene with respect to the nucleolus, the nuclear envelope and the center of the nucleus under repressing and activating conditions (Figure 1A, B & C; Berger et al., 2008). In cells grown in repressing conditions, INO1 localized in the nucleoplasm with no obvious bias in its distribution (Figure 1D, left panel). In cells grown under activating conditions, INO1 localized at the nuclear periphery preferentially to a position corresponding to ~75° ± 31° acute angle between the line connecting the locus to the center of the nucleus and the axis connecting the center of the nucleus and the center of the nucleolus (α; Figure 1B & C, Figure S1 and Table S2). We also observed a population of cells in which INO1 was localized in the nucleoplasm, near the nucleolus (Figure 1C). This population might correspond to cells that are in S-phase, a period of the cell cycle in which peripheral targeting is temporarily lost (Brickner and Brickner, 2010). A similar bimodal distribution has been observed for GAL1 when it is targeted to the nuclear periphery (Berger et al., 2008). Regardless, when targeted to the nuclear periphery, INO1 localized to a restricted portion of the envelope.

Figure 1. INO1 is targeted to a limited region of the nuclear envelope.

(A) Representative micrograph of yeast nuclei having the lac repressor array integrated at INO1 and expressing GFP-LacI, GFP-Nup49 labeling the nuclear envelope and Nop1-mCherry labeling the nucleolus (maximum projection of 250nm Z stacks). Scale bar = 1µm.

(B) Coordinates used in this study: nucleolus and nucleus centroids (red and grey balls respectively), central axis (dashed line joining the two centroids), radial axis (dashed line joining the locus and the nuclear centroid), α, polar angle defined by these two axes.

(C) INO1 gene map based on the analysis of 2950 nuclei grown in the presence of inositol 100µM (repressed, left) or on the analysis of 2627 nuclei grown in the absence of inositol (active, right). Dashed red circle: ‘median’ nucleolus; red circle, median location of nucleolar centroid. The color scale indicates the probability that the locus is inside the region enclosed by the corresponding contour, which may include regions enclosed by other contours. The dark red contour corresponds to the localization observed in 10% of the population and the dark blue contour corresponds to the localization observed in 90% of the population. See also Figure S1.

Clustering of INO1 upon activation

If gene positioning is encoded in cis-acting DNA elements, it might be possible to either target an ectopic site to the same location as the endogenous gene or to induce clustering of genes. To test this idea, we integrated the INO1 gene from chromosome X beside the URA3 gene on chromosome V. Like the endogenous INO1 gene, this hybrid locus (URA3:INO1) is targeted to the nuclear periphery upon activation of INO1 (Ahmed et al., 2010; Light et al., 2010). This allowed us to compare the positions of the endogenous INO1 gene and the ectopic URA3:INO1 gene.

To determine if URA3:INO1 is targeted to the same region of the nuclear membrane as INO1, we compared the positions of these loci with respect to each other. We utilized a strain having an array of Lac repressor binding sites beside URA3, an array of Tet repressor binding sites beside INO1 and expressing LacI-RFP and TetR-GFP (Figure 2A). We measured the distance between the center of the red spot and the center of the green spot for ≥100 fixed cells in which the two dots were within the same confocal section (z depth ~ 0.7µm; Experimental Procedures; Figure 2B). The distances were binned into 0.2µm classes to generate a distribution of distances within the population, which we compared using a two-tailed t test. As a negative control, we determined the distribution of distances between active INO1 (at the nuclear periphery) and URA3 (in the nucleoplasm). We observed a normal distribution of distances between INO1 and URA3, with a mean distance of 1.08 ± 0.43µm (Figure 2C). In contrast, the distances between INO1 and URA3:INO1 (under activating conditions) were clearly shifted to shorter distances, with a mean distance of 0.48 ± 0.28µm (P < 0.0001; Figure 2C). Therefore, the introduction of INO1 at URA3 caused URA3 to localize to a similar portion of the nucleus as the endogenous INO1 gene.

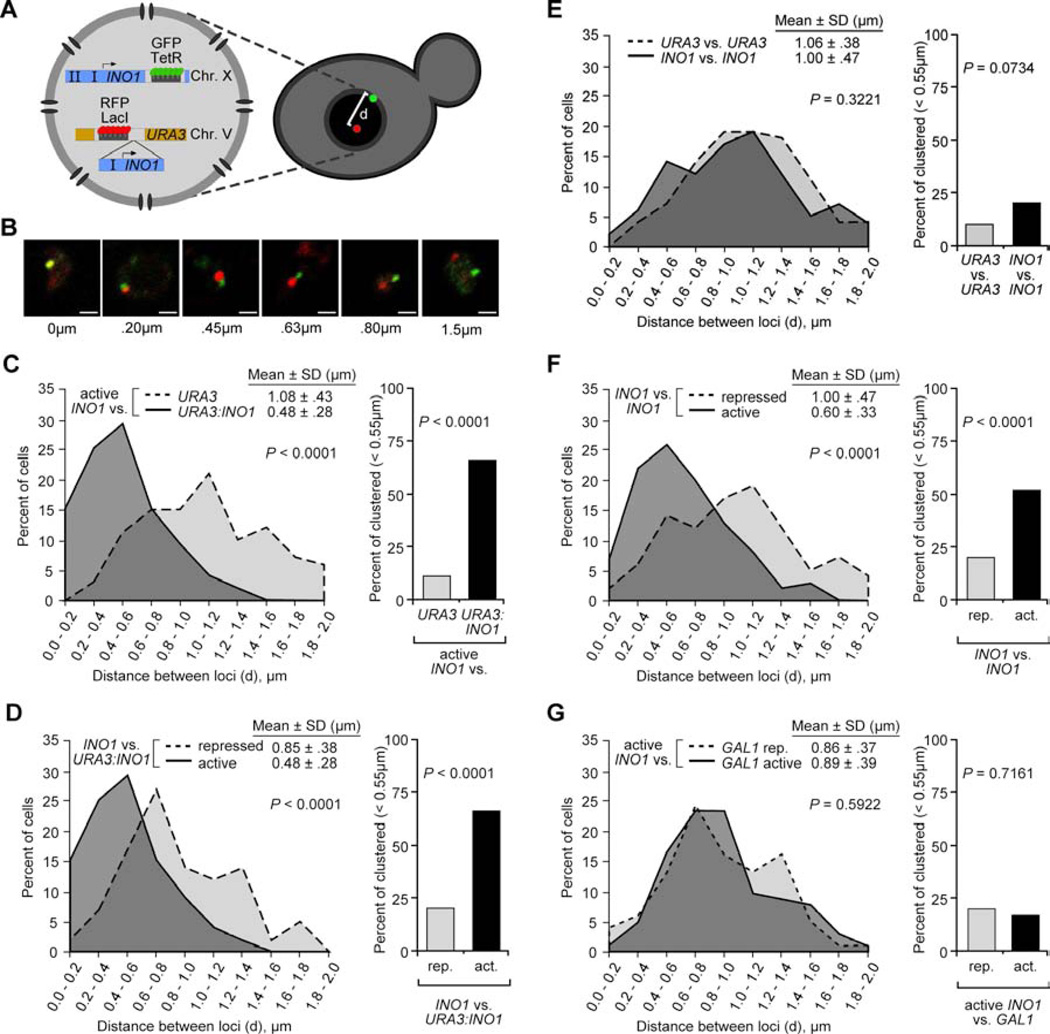

Figure 2. INO1 clustering.

(A) Schematic of experimental strategy. An array of 128 Lac repressor-binding sites was integrated beside URA3 on chromosome V and an array of 112 Tet repressor binding sites was integrated beside INO1 on chromosome X in a strain expressing GFP-LacI and RFP-TetR. The positions of GRS I and GRS II in the promoter of INO1 are indicated as I and II, respectively. To create URA3:INO1, the INO1 gene was integrated beside URA3.

(B) Example distances between two loci. Cells were fixed, stained with antibodies against GFP and RFP, visualized by line-scanning confocal microscopy and distances between the centers of the spots were measured using Zeiss LSM software. Scale bar = 1µm. For panels C–G: Left: plot of the distribution of the frequency of each distance between loci in the population (n ≥100 cells). Right: the fraction of cells in which the loci were < 0.55µm apart.

(C) Distribution of distances between active INO1 and URA3 or between active INO1 and URA3:INO1.

(D) Distribution of distances between INO1 and URA3:INO1 under activating (−inositol; same distribution as in panel C) and repressing (+inositol) conditions.

(E) Distribution of distances between either two alleles of URA3 or two alleles of INO1 in diploid cells in repressing conditions.

(F) Distribution of distances between two alleles of INO1 in diploid cells in repressing or activating conditions.

(G) Distribution of distances between INO1 and GAL1 in cells grown in activating conditions for INO1 and either repressing (glucose) or activating (galactose) conditions for GAL1.

The change in distances between these loci was highlighted when we plotted the fraction of the spot pairs that were qualitatively “clustered” (defined here as a distance < 0.55µm). The two dimensional area of a circle of diameter 0.55µm (0.24µm2) is ~8% of the two dimensional area of the typical haploid yeast nucleus (3.14µm2; diameter = 2µm). Clustering increased from 11% for INO1 vs. URA3 to 66% for INO1 vs. URA3:INO1 (P < 0.0001, Fischer’s exact test; Figure 2C). Clustering of the two loci was dependent on activation; INO1 did not cluster with URA3:INO1 under repressing conditions (Figure 2D). Therefore, activation of INO1 on chromosome X led to clustering with URA3:INO1 on chromosome V.

The mean distance and clustering between the INO1 and URA3 (1.08 ± 0.43µm & 11%) was significantly different than the mean distance and clustering between repressed INO1 and URA3:INO1 (0.85 ± .38µm & 20%; Figure 2C & D). This may reflect either the proximity of these two loci in the nucleoplasm when INO1 is repressed or a small amount of background expression of INO1 under repressing conditions. Consistent with this latter possibility, the localization of repressed INO1 or URA3:INO1 at the nuclear periphery is systematically higher than the localization of URA3 and the nuclear periphery (Ahmed et al., 2010; Brickner and Walter, 2004). For this reason, we compared against repressed URA3:INO1 for subsequent experiments.

To ask if the two endogenous alleles of INO1 in a diploid nucleus cluster upon activation, we used a diploid yeast strain having a Lac repressor array integrated beside one allele of INO1 and the Tet repressor array integrated beside the other allele. The mean distance and the clustering between the two copies of repressed INO1 were similar to that of two copies of URA3 (1.06 ± 0.38µm vs. 1.00 ± 0.47µm; P = 0.2998; Figure 2E). In contrast, upon activation of INO1, the mean distance between the two copies of INO1 was significantly reduced (0.60 ± 0.33µm; P < 0.0001) and the clustering was significantly increased (20% vs. 52%; P < 0.0001; Figure 2F). Thus, the clustering of active INO1 occurred both in haploid cells between the endogenous gene and an ectopic locus and in diploids between two alleles of the endogenous gene.

Clustering is gene-specific

To probe the specificity of gene clustering, we localized active INO1 with respect to GAL1, another gene that is targeted to the nuclear periphery upon activation (Berger et al., 2008; Cabal et al., 2006; Casolari et al., 2004; Schmid et al., 2006). The distributions of distances between INO1 and either active or repressed GAL1 were indistinguishable (Figure 2G) and were very similar to the distribution of distances between repressed INO1 and URA3:INO1 (P = 0.4635 for active GAL1). Thus, targeting to the nuclear periphery is not sufficient to induce gene clustering.

We performed a series of pairwise comparisons between HSP104 and GAL1, INO1 and GAL2, genes that localize at the nuclear periphery upon activation. For these experiments, we used a different experimental strategy (Figure 3A). A “large” array of 256 Lac repressor-binding sites was integrated adjacent to HSP104 and a “small” array of 128 binding sites adjacent to INO1, GAL1 or GAL2. This resulted in strains with a discernably larger green dot marking HSP104 and a small green dot marking INO1, GAL1 or GAL2 (Figure 3A). HSP104 is targeted to the nuclear periphery upon activation under heat shock or in the presence of 10% ethanol (Dieppois et al., 2006) and the GAL1 and GAL2 genes are induced by growth in galactose (Casolari et al., 2004). We measured the distance between the spots under both uninducing and inducing conditions for these genes. Because we used a different fixation method (methanol instead of formaldehyde; Experimental Procedures), which causes the cells to shrink slightly (Brickner et al., 2010), the distances between the spots under uninducing conditions were slightly smaller in these experiments than in the experiments using two different fluorescent proteins. However, for all three of these pairwise comparisons, we observed neither a significant change in the distribution of distances between the genes nor significant clustering upon activation (Figure 3B, 3C & 3D). This was not due to the difference in fixation conditions because we were able to observe clustering using this fixation method (see below). Therefore, INO1, GAL1 and GAL2 do not cluster with HSP104.

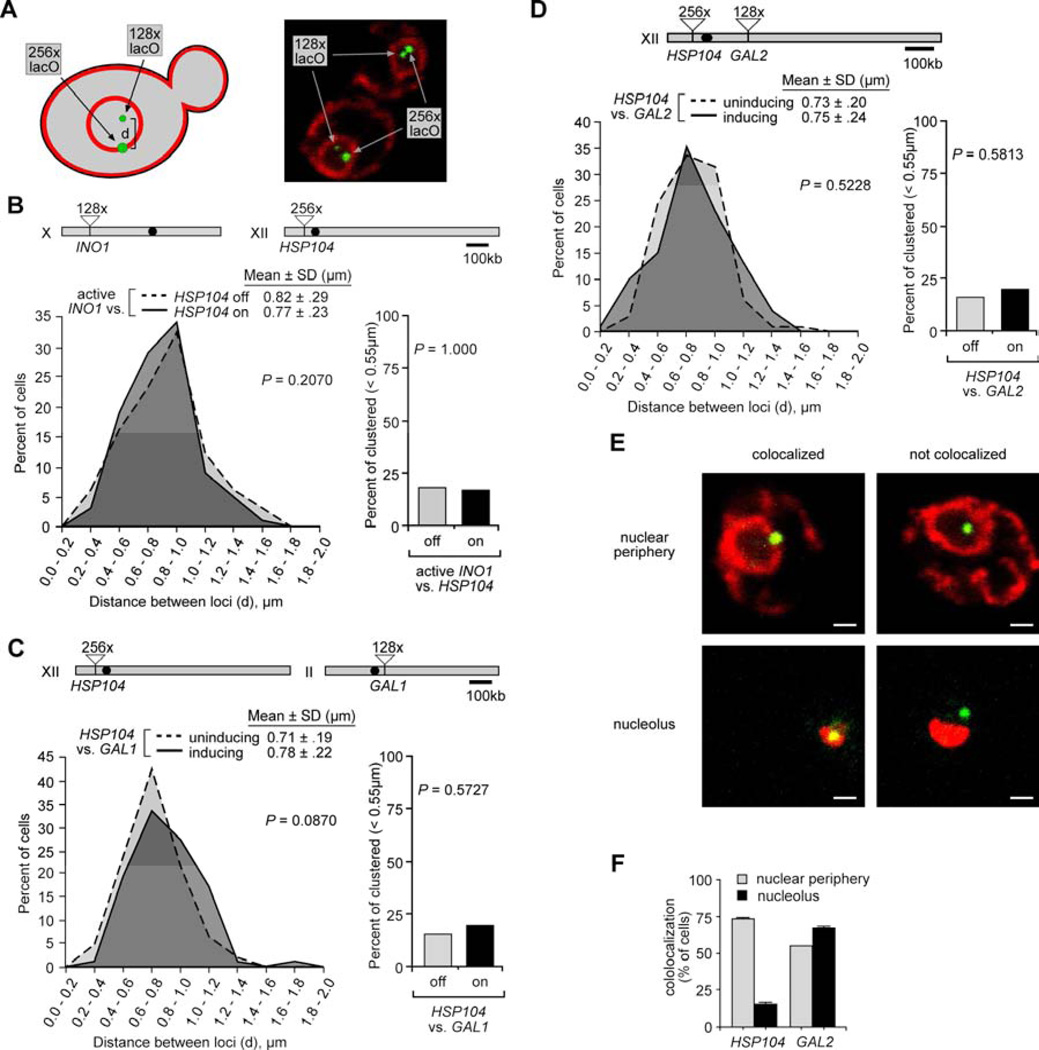

Figure 3. Gene clustering is specific.

(A) Left: schematic of two green dot experimental strategy. An array of 256 Lac repressor-binding sites was integrated beside HSP104 and an array of 128 Lac repressor-binding sites was integrated beside other loci. Right: representative confocal micrographs of a strain having a large array and a small array, stained with anti-GFP and anti-myc (to stain myc-tagged Sec63 in the endoplasmic reticulum and nuclear envelope). Scale bar = 1µm. For panels B, C & F, Top: chromosomal locations of genes. Left: plot of the distribution of the distances between loci in the population. Right: the fraction of cells in which the loci were <0.55µm apart.

(B) Distribution of distances between HSP104 and INO1, under conditions in which only INO1 is active (−inositol) or conditions in which both genes are active (−inositol + 10% ethanol).

(C) Distribution of distances between HSP104 and GAL1, under uninducing (glucose) or inducing (galactose +10% ethanol) conditions.

(D) Representative images scored for co-localization of HSP104 or GAL2 with either the nuclear envelope (stained with anti-myc for Sec63-myc) or the nucleolus (stained with anti-Nop5/6). Scale bar = 1µm.

(E) The fraction of cells in which HSP104 or GAL2 co-localized with the nuclear envelope or the nucleolus (n = 3; 30–50 cells per biological replicate; error bars = SEM).

(F) Distribution of distances between HSP104 and GAL2, grown in uninducing or inducing conditions.

HSP104 and GAL2 are ~290kb apart and on left and right arms of chromosome XII, separated by ~107 genes (Figure 3D). HSP104 and GAL2 localize to different parts of the nucleus. Whereas GAL2 co-localized with the nucleolus (Berger et al., 2008; Brickner et al., 2010; Gard et al., 2009), presumably because of its proximity to the rDNA genes on the right arm of chromosome XII, HSP104 did not (Figure 3E & 3F). Therefore, within chromosome XII, the positioning of HSP104 and GAL2 at the nuclear periphery is distinct and is likely impacted by neighboring elements such as the centromere and the rDNA locus, which have strong, stable localization patterns (Duan et al., 2010).

Targeting of INO1 to the nuclear periphery is a prerequisite for clustering

Targeting of genes to the nuclear periphery involves the interaction between the nuclear pore complex (NPC) and their promoters (Ahmed et al., 2010; Brickner et al., 2007; Cabal et al., 2006; Casolari et al., 2005; Casolari et al., 2004; Light et al., 2010; Schmid et al., 2006; Taddei et al., 2006). Repressed INO1 co-localizes with the nuclear envelope in ~30% of the cells in the population and active INO1 co-localizes with the nuclear envelope in ~65% of the cells in the population (Brickner et al., 2010; Brickner and Walter, 2004). Similar localization frequencies are seen for other genes that are targeted to the nuclear periphery (Brickner et al., 2007; Casolari et al., 2004). Thus, targeting to the nuclear periphery does not result in localization of a gene to the nuclear periphery in 100% of the cells. This reflects both the dynamic nature of localization - even when localized at the nuclear periphery, genes continue to move (Cabal et al., 2006) - and the regulation of gene localization during the cell cycle; genes like INO1, GAL1 and HSP104 lose peripheral localization during S-phase (Brickner and Brickner, 2010, 2011). Therefore, clustering of active INO1 could occur at the nuclear periphery, in the nucleoplasm or both.

If targeting to the nuclear periphery were involved in gene clustering, we expected that clustering would be disrupted by mutations in the nuclear pore that block targeting to the NPC. Nup2, part of the nucleoplasmic basket of the NPC, interacts with the active INO1 promoter by ChIP and is required for targeting of INO1 to the nuclear periphery (Ahmed et al., 2010; Brickner et al., 2007; Light et al., 2010). In cells lacking Nup2, we did not observe clustering of active INO1 and URA3:INO1 (Figure 4A). Therefore, interaction of genes with the NPC is required for both peripheral targeting and interchromosomal clustering.

Figure 4. Clustering of INO1 requires targeting to the nuclear pore complex.

(A) Distribution of distances between INO1 and URA3:INO1 in NUP2 (data from Figure 2C) and nup2Δ cells grown under activating conditions (−inositol).

(B) Clustering of active INO1 and URA3:INO1 in cells in which the nuclear envelope was also stained. Clustering of the two loci was determined in ~30 cells of each of the three classes: both genes on the nuclear envelope (on/on), one gene on the nuclear envelope (on/off) or both genes off the nuclear envelope (off/off). In all cases where the locus was scored as peripheral, the center of the green dot was < 0.25µm from the cytoplasmic edge of the nuclear envelope.

(C) Cells having the Tet repressor array at INO1 and the Lac repressor array at URA3:INO1 were arrested with hydroxyurea either after activating INO1 or before activating INO1.

We next asked if clustering of active INO1 was strictly correlated with localization at the nuclear periphery. We compared clustering of INO1 with URA3:INO1 in three classes of cells: cells in which both genes co-localized with the nuclear envelope (on/on), cells in which neither locus co-localized with the nuclear envelope (off/off) and cells in which one of the loci co-localized with the nuclear envelope (on/off). Clustering was highest in the population of cells in which both loci co-localized with the nuclear envelope (72% clustering; mean distance = 0.40 ± 0.25µm) and was not apparent in cells in which only one locus co-localized with the nuclear envelope (12.5% clustering; mean distance = 0.75 ± 0.33µm). In contrast, if we compared two genes that did not show clustering (INO1 and HSP104) in the cells in which both loci were at the nuclear periphery, they did not cluster (mean distance = 0.88 ± 0.24µm; data not shown). Thus, for genes that cluster, we observe the highest level of clustering when both loci are at the nuclear periphery.

Surprisingly, we also observed significant clustering in the cells in which both loci localized in the nucleoplasm (59% clustering; mean distance = 0.49 ± 0.32µm; Figure 4B). This was true when we compared active INO1 with URA3:INO1, but was not true when we quantified the clustering of repressed INO1 with URA3:INO1, URA3 or a second allele of INO1 in the nucleoplasm (Figure 2). Therefore, although clustering correlated with activation and occurred between loci that are targeted to the nuclear periphery by the same mechanism, the clustering can also occur in the nucleoplasm.

We hypothesized that targeting to the nuclear periphery was a pre-requisite step to establish clustering, which could be maintained in the nucleoplasm. To test this idea, we asked if activation of INO1 under conditions when it does not localize at the nuclear periphery would lead to clustering. Treating cells with hydroxyurea traps cells in S-phase, a period of the cell cycle when peripheral localization of INO1 is lost (Brickner and Brickner, 2010). In cells in which INO1 and URA3:INO1 were already active before treating with hydroxyurea, they remained clustered after arrest (Figure 4C). Therefore, clustering was maintained in the nucleoplasm during S-phase in cells in which the two loci had previously been targeted to the nuclear periphery.

If clustering in the nucleoplasm requires previous targeting to the nuclear periphery, then inducing INO1 after they have been arrested in S-phase should not result in clustering. We found that INO1 and URA3:INO1 did not cluster in cells were starved for inositol after they were arrested with hydroxyurea (Figure 4C). This suggests that targeting to the nuclear periphery is a prerequisite for gene clustering and that, once established, clustering can be maintained in the nucleoplasm.

DNA zip codes control gene clustering

Given the importance of targeting to the nuclear periphery for gene clustering, we asked if DNA zip codes control the clustering of INO1 with URA3:INO1. Two redundant Gene Recruitment Sequences (GRS I and II) in the promoter of INO1 are responsible for targeting active INO1 to the nuclear periphery (Ahmed et al., 2010). Because the construct used to create URA3:INO1 possesses only the GRS I element (Figure 2A; Ahmed et al., 2010), we hypothesized that the GRS I element controlled clustering of INO1 and URA3:INO1. To test this idea, we compared the localization of grsImutINO1 with URA3:INO1. This mutation disrupts the GRS I element at the endogenous INO1 locus, but does not block targeting of INO1 to the nuclear periphery because GRS II is still functional (Ahmed et al., 2010). Mutation of the GRS I element in the INO1 promoter led to dramatic increase in the mean distance between INO1 and URA3:INO1 (1.03 ± .29µm) and abolished clustering of INO1 with URA3:INO1 (Figure 5A). Intriguingly, the clustering of grsImutINO1 with URA3:INO1 (3%) was lower than the clustering of either INO1 with URA3 (11%) or grsI,IImutINO1 with URA3:INO1 (9%; Figures 5A, 2C & S2A). This raises the possibility that grsImutINO1 and URA3:INO1 are targeted to distinct portions of the nuclear envelope. Together, these results suggest that the GRS I zip code is necessary for clustering of INO1 with URA3:INO1 and that the GRS I and GRS II zip codes mediate distinct targeting mechanisms.

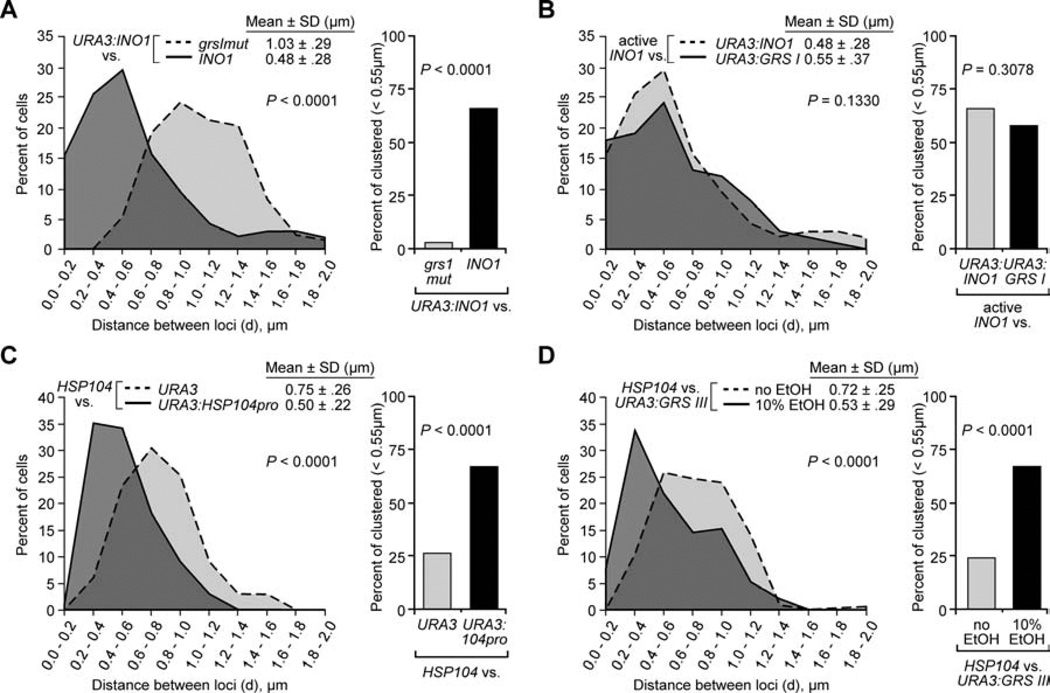

Figure 5. Gene clustering is controlled by DNA zip codes.

Panels A & B used the strategy described in Figure 2A. Panels C & D used the strategy described in Figure 3A.

(A) Distribution of distances between URA3:INO1 and either wild type INO1 (same data as Figure 2C) or grsImut INO1 (Ahmed et al., 2010) in cells grown under activating conditions (−inositol).

(B) Distribution of distances between active INO1 and either URA3:INO1 (same as Figure 2C) or URA3:GRS I.

(C) Distribution of distances between active HSP104 and either URA3 or URA3:HSP104prom.

(D) Distribution of distances between HSP104 and URA3:GRS III in cells grown in the presence or absence of 10% ethanol.

See also Figures S2 and S3.

The GRS I and GRS II elements are sufficient, when introduced at an ectopic location, to induce localization at the nuclear periphery (Ahmed et al., 2010). To test if the GRS I or GRS II elements were also sufficient to induce clustering, we compared the position of INO1 to either URA3:GRS I or URA3:GRS II. URA3:GRS I clustered with INO1 to an extent similar to the clustering of URA3:INO1 with INO1 (mean distance = 0.55 ± 0.37µm; 58% clustering; Figure 5B). However, URA3:GRS II did not cluster with INO1 (mean distance = 0.82 ± 0.40µm; 29% clustering; Figure S2B). This suggests that GRS I is the dominant zip code in controlling gene clustering and is sufficient to recapitulate the clustering of INO1 with URA3:INO1.

To explore the generality of our findings, we performed a similar analysis with the HSP104 promoter. HSP104 does not cluster with INO1 (Figure 3B). First, we asked if the localization of HSP104 was controlled by DNA zip codes in its promoter by integrating the HSP104 promoter (HSP104pro) adjacent to URA3. Under conditions that induce HSP104 transcription and targeting to the nuclear periphery, URA3:HSP104pro was also targeted to the nuclear periphery (Figure S3A). Therefore, the HSP104 promoter contains DNA zip code activity.

We next compared the localization of HSP104 and URA3:HSP104pro using the system described in Figure 3. Under non-inducing conditions, HSP104 did not cluster with URA3 (mean distance = 0.71 ± 0.19 µm; 23% clustering) or with URA3:HSP104pro (mean distance = 0.70 ± 0.19µm; 25% clustering; Figure S3B). However, under inducing conditions (10% ethanol), HSP104 clustered with URA3:HSP104pro (mean = 0.50 ± 0.22µm; 67% clustering; Figure 5C), but not with URA3 (mean = 0.75µm ± 0.26µm; 26% clustering). Furthermore, as with INO1 and URA3:INO1, the highest clustering of HSP104 with URA3:HSP104pro was observed in cells in which both loci were peripheral, and was not observed in cells in which one locus was peripheral and the other was nucleoplasmic (Figure S3C). Therefore, the HSP104 promoter is sufficient to cause URA3 to cluster with the endogenous HSP104 gene at the nuclear periphery.

We mapped the DNA zip code activity in the HSP104 promoter to a 30 base pair fragment (GRS III) within the HSP104 promoter that was sufficient to target URA3 to the nuclear periphery (Figure S3A). Targeting by GRS III was constitutive and independent of activation of HSP104 (Figure S3A), suggesting that, like the GRS elements in the INO1 promoter, the zip code activity of GRS III is negatively regulated in the context of the promoter (Ahmed et al., 2010). Under inducing conditions, HSP104 clustered with URA3:GRS III (Figure 5D; mean = 0.53 ± 0.29µm; 60% clustering), but not under non-inducing conditions (Figure 5D; mean = 0.72µm ± 0.25µm; 25% clustering; P < 0.0001). Therefore, two different DNA zip codes are sufficient to mediate clustering of URA3 with two different endogenous genes.

Endogenous GRS I genes cluster

Because the GRS I element was necessary and sufficient to induce clustering with active INO1, we tested if other genes with the GRS I element would also cluster with INO1. TSA2 on chromosome IV has a GRS I element in its promoter that is required for targeting TSA2 to the nuclear periphery (Ahmed et al., 2010). Therefore, we asked if TSA2 and INO1 cluster at the nuclear periphery when active. When INO1 was active and TSA2 was not (Figure 6A), the mean distance (0.83 ± 0.41µm) and the clustering (25%) between the genes was similar to the mean distance and clustering between repressed INO1 and URA3:INO1 (mean = 0.85 ± 0.38µm; 20% clustering). However, in cells in which both TSA2 and INO1 were active (Figure 6A), we observed a significant decrease in the mean distance between the genes (mean = 0.58 ± 0.38µm; P < 0.0001) and a significant increase in the fraction of the population in which they are clustered (54%; P < 0.0001). Therefore, two endogenous GRS I-targeted genes on different chromosomes cluster together in the nucleus.

Figure 6. Clustering of endogenous GRS I-targeted genes.

(A) Distribution of distances between TSA2 and INO1 in cells grown under activating conditions for INO1 (−inositol) or activating conditions for INO1 and TSA2 (−inositol +10% ethanol).

(B) Distribution of distances between TSA2 and either wild type INO1 (same data as in panel A) or grsImutINO1 in cells grown under activating conditions.

To confirm that clustering of active INO1 with active TSA2 is due to GRS I-mediated targeting to the nuclear periphery, we compared the localization of active grsImutINO1 with TSA2. The distribution of distances between active grsImutINO1 and TSA2 revealed that the mean distance (0.91µm ± 0.42µm) and the clustering (25%) were very similar to the mean distance and clustering of active INO1 with uninduced TSA2 (Figure 6B). Thus, clustering of INO1 and TSA2 requires the GRS I zip code.

The Put3 transcription factor recognizes the GRS I zip code to mediate gene targeting and clustering

Given the importance of the GRS I zip code in controlling gene targeting to the nuclear periphery and clustering, we sought to identify protein(s) that recognize GRS I to mediate targeting and clustering. We observed two activities from yeast lysates in electrophoretic mobility shift assays that bound to a 4× GRS I probe (band A and band B; Figure 7A). These activities were sensitive to heat, SDS and proteinase digestion, suggesting that they represent proteins (Figure S4A). Competition with unlabeled wild type and mutant 1× GRS I demonstrated that binding of band A was specific (Figure S4B). Also, whereas band A was able to bind both the multimerized 4× GRS I and a single copy 1× GRS I, band B was able to bind to multimerized GRS I probe only, suggesting that band B was an in vitro artifact (Figure S4C). Therefore, we identified the protein responsible for band A by enriching for this activity using DNA affinity chromatography, followed by mass spectrometry (Experimental Procedures). This experiment identified 50 candidate proteins that were enriched in the eluate from 4× GRS I beads relative to control beads (Table S2). Lysates from strains either expressing tagged versions of these proteins or lacking these proteins were tested using the EMSA (Experimental Procedures; data not shown). Only one of the 50 proteins affected band A activity; lysates from strains lacking the transcription factor Put3 exhibited band B activity, but not band A activity (Figure 7A, lanes 3 & 4). This defect was complemented by expression of GST-Put3 (Figure 7A, lane 5). In the put3Δ strain expressing GST-Put3, band A was super-shifted into the well in the presence of anti-GST antibody (Figure 7A, lane 6), suggesting that GST-Put3 is in complex with GRS I.

Figure 7. The Put3 transcription factor mediates GRS I-dependent clustering.

(A) An electrophoretic mobility shift assay of yeast lysates incubated with radiolabeled 4×GRS probe. Lysates were prepared from either a wild type strain (lanes 1 & 2) or a put3Δ mutant strain (lanes 3–6). The put3Δ strain was transformed with a plasmid expressing GST-PUT3 under the control of the ADH1 promoter (lanes 5&6). Anti-GST antibody was added to reactions in lanes 2, 4 and 6.

(B) Localization of repressed and active INO1 and URA3:INO1 in PUT3 and put3Δ mutants with respect to the nuclear envelope. The dynamic range of this assay is from 20%–85% and the blue, hatched line represents the distribution of the URA3 gene with respect to the nuclear envelope (Brickner et al., 2010; Brickner and Walter, 2004).

(C) Localization of TSA2 in PUT3 and put3Δ cells before or after heat shock (30 minutes).

(D) ChIP against GST or GST-Put3 from cells grown in the presence or absence of inositol.

(E) ChIP against Nup2-TAP from PUT3 and put3Δ strains grown in the presence or absence of inositol. For panels C – E, the immunoprecipitated DNA was quantified relative to input by real-time quantitative PCR.

(F) mRNA levels for INO1, URA3:INO1 or URA3:grsImut INO1 in PUT3 or put3Δ strains, quantified by RT-qPCR relative to ACT1 mRNA. For panels B–F, error bars = SEM.

(G) Left: distribution of distances between Tet repressor-marked INO1 and Lac repressor-marked URA3:INO1 in wild type (same data as in Figure 2A) and put3Δ cells grown under activating conditions (−inositol). Right: the fraction of cells in which the loci were < 0.55µm apart.

See also Figure S4.

To test if Put3 plays a role in GRS I-dependent targeting to the nuclear periphery, we localized INO1, URA3:INO1 and TSA2 in strains lacking Put3 (Figure 7B & 7C). In strains lacking Put3, targeting of URA3:INO1 and TSA2 to the nuclear periphery was lost, but targeting of INO1 (which possesses GRS II) to the nuclear periphery was maintained (Figure 7B & 7C). Likewise, Put3 was also required for targeting of URA3:GRS I to the nuclear periphery (Figure S4E). Loss of Put3 also resulted in a defect in the expression URA3:INO1 very similar to the effect of mutation of the GRS I element, but did not affect expression of INO1 (Figure 7F). Therefore, Put3 is required for GRS I-, but not GRS II-, mediated targeting to the nuclear periphery and transcription. Consistent with this conclusion, GRS II did not compete with GRS I for binding to Put3 in EMSA experiments (Figure S4D).

Put3 is a Zn2-Cys6 zinc finger transcription factor that regulates expression of genes involved in proline metabolism (Siddiqui and Brandriss, 1989). Put3 binds to the UASPUT element in the promoters of PUT1 and PUT2 (Siddiqui and Brandriss, 1989). This element (CGG-N10-GCC) is not obviously related to the GRS I element defined by zip code activity at URA3 (GGGTTGGA; Ahmed et al., 2010). To confirm that Put3 interacts with the GRS I element in vivo, we performed chromatin immunoprecipitation (ChIP) using GST-Put3. Whereas GST-Put3 interacted constitutively with the PUT2 promoter by ChIP (Figure 7D), it interacted with the INO1 and TSA2 promoters only under activating conditions (Figure 7D & S4F). GST-Put3 did not interact with RPA34, an intergenic locus ~4.5kb upstream of the INO1 promoter (Figure 7D). Thus, Put3 specifically binds to active GRS I-containing promoters in vivo in a manner that correlates with targeting to the nuclear periphery.

Targeting to the nuclear periphery involves a physical interaction of genes with the NPC. The GRS I is sufficient to induce a ChIP interaction with the NPC (Ahmed et al., 2010). To ask if interaction of the NPC with the GRS I requires Put3, we performed ChIP with Nup2-TAP in the put3Δ mutant strain and quantified the recovery using primers flanking the GRS I element. Interaction of Nup2-TAP with the GRS I element in the INO1 promoter was lost in the put3Δ strain (Figure 7G). Therefore, Put3 is necessary for GRS I-mediated targeting to the nuclear periphery and interaction with the nuclear pore complex.

Finally, loss of Put3 led to loss of clustering between INO1 and URA3:INO1 (Figures 2A and 7G; P < 0.0001 for both mean distance and clustering compared with the PUT3 strain). Therefore, Put3 physically binds to the GRS I in vivo and in vitro and is required for GRS I-mediated targeting and clustering at the nuclear periphery.

DISCUSSION

Here we demonstrate that genes that localize at the nuclear periphery through interaction with the NPC can cluster together with genes on other chromosomes. This property is controlled by DNA zip codes in their promoters that can be transplanted to an ectopic site on another chromosome. Clustering mediated by DNA zip codes requires trans-acting factors and interaction with the nuclear pore. This suggests that DNA zip code-encoded positioning of individual genes impacts the proximity of loci on different chromosomes within the nucleus and the folding of the genome as a whole.

Interchromosomal clustering of loci is a common theme and has been observed in many cell types and under many conditions. Telomeres cluster in most cells and this has been proposed to favor repression of subtelomeric genes (Bass et al., 1997; Cooper et al., 1998; Dernburg et al., 1996; Gotta and Gasser, 1996; Lanzuolo et al., 2007; Scherthan et al., 1996; Tolhuis et al., 2011). Likewise, Polycomb-repressed genes in Drosophila cluster at Polycomb bodies (Lanzuolo et al., 2007; Tolhuis et al., 2011). In budding yeast, many of the 274 tRNA genes cluster into a small number of foci within the nucleolus (Gard et al., 2009; Thompson et al., 2003). Loss of the transcriptional repressor protein Dig1 results in increased interchromosomal clustering of its target genes (McCullagh et al., 2010). In mammalian cells, co-regulated genes that are induced during erythropoiesis cluster together at “transcription factories” (Brown et al., 2006; Schoenfelder et al., 2010; Xu and Cook, 2008b). And in Schizosaccharomyces pombe, genome-wide chromosome conformation capture studies suggest that many genes of related function cluster in the nucleus (Tanizawa et al., 2010). Although clustering of these loci in some cases requires DNA binding proteins (Laroche et al., 1998; Schoenfelder et al., 2010) and is correlated with shared DNA elements (Gotta et al., 1996; Molnar and Kleckner, 2008; Schoenfelder et al., 2010; Tanizawa et al., 2010) or sequence homology (Molnar and Kleckner, 2008), it is unclear if these factors mediate clustering or regulate clustering. Here we find that small DNA zip codes in the promoters of genes that are targeted to the nuclear periphery are both necessary and sufficient to confer interchromosomal gene clustering.

Our observations support the notion that genomes code for positioning of genes to restricted “territories” within the nucleus (Berger et al., 2008). We have found that two different DNA zip codes from the INO1 and HSP104 promoters, when integrated adjacent to the URA3 gene, are sufficient to cause URA3 to cluster with the genes from which they came. Because INO1 and HSP104 do not localize to the same portion of the nuclear envelope (Figure 3), this suggests: 1) that URA3 is not highly constrained, 2) that these DNA zip codes are able to override any local positioning information to induce clustering with either INO1 or HSP104 and 3) that INO1 and HSP104 may be targeted to distinct portions of the nuclear envelope.

The transcription factor Put3 binds to the GRS I zip code and is necessary for GRS I-mediated targeting to the nuclear periphery and clustering. This suggests that transcription factors can affect both transcription and gene localization. Although physical interaction with the NPC has been correlated with transcription factor binding sites (Casolari et al., 2004; Schmid et al., 2006) and clustering of co-regulated genes at transcription factories requires the transcription factor Klf1 (Schoenfelder et al., 2010), it is still unclear if these transcription factors regulate gene localization or mediate gene localization. Put3 is required for GRS I zip code activity both in the context of promoters where gene localization is regulated and when inserted at URA3, where it is not. This suggests that Put3 mediates the GRS I-dependent effects on localization and clustering.

A role for Put3 in controlling gene localization and clustering is unanticipated. Put3 is a nucleoplasmic protein with no obvious bias in its localization (our unpublished data; Huh et al., 2003). Furthermore, the sequence to which Put3 binds in the context of the PUT1 and PUT2 promoters (the UASPUT; CGG-N10-GCC) does not resemble the sequence of the core GRS I (GGGTTGGA), deduced by mapping zip code activity by insertion at URA3 (Ahmed et al., 2010). However, the binding specificity of Put3 is still incompletely understood. A genome-wide ChIP-chip study identified the Put3 motif as CGGAAGCC (MacIsaac et al., 2006). Two different studies using unbiased biochemical approaches found that the Put3 DNA binding domain interacts with the sequence TCCCGGG (Badis et al., 2008; Zhu et al., 2009). From a library of 32,897 8mers, the sequence CGGGGTTA, which resembles part of the GRS I in the INO1 promoter, ranks in the top 0.16% of sequences for binding to Put3 (Badis et al., 2008). Although each of these approaches has its limitations, it is clear that Put3 can recognize multiple sequences with a reasonable affinity. Therefore, it seems likely that Put3 plays two functionally distinct roles: one to control transcription of the PUT genes and another to control the interaction of stress-inducible genes with the NPC. Consistent with this hypothesis, the PUT1 or PUT2 promoters do not interact with the NPC by ChIP (Casolari et al., 2004), despite the fact that Put3 is bound to these promoters constitutively (Figure 7; Axelrod et al., 1991). Furthermore, the UASPUT, when inserted at URA3, does not function as a DNA zip code (S. A. and J.H.B., unpublished results). Finally, a fragment of Put3 that includes the amino terminal DNA binding domain and dimerization domain, but lacks the carboxy terminal 853 amino acids, supports GRS I-mediated targeting to the nuclear periphery (S. A. and J.H.B., unpublished results). This fragment lacks the activation domain and does not support PUT gene expression (des Etages et al., 1996). Together, these observations suggests that the Put3 DNA binding domain binds to these two sequences in two distinct conformations, allowing it to interact with distinct “effectors”.

Our results raise the possibility that genes are targeted to restricted portions of the nuclear periphery. INO1 localizes to a restricted band at the nuclear envelope (Figure 1). The zip code responsible for targeting INO1 to the nuclear periphery is also sufficient to induce interchromosomal clustering of an ectopic locus with the endogenous INO1 gene (Figure 5). This suggests that INO1 and other GRS I genes are targeted to the same portion of the nuclear envelope. We do not propose that genes that share zip codes are targeted to the same NPC; our data are consistent with genes being targeted to a portion of the nuclear envelope that would include a number of NPCs. How might this work? It is possible that zip code adaptor proteins such as Put3 interact with proteins that are stably and heterogeneously distributed at the nuclear envelope. However, there are very few yeast proteins that are heterogeneously distributed on the nuclear envelope and these are generally associated with telomeres (Gotta et al., 1996; Huh et al., 2003). Therefore, it is possible that the active forms of these hypotherical proteins, perhaps controlled by post-translational modifications, are heterogeneously distributed. Likewise, it is conceivable that the biochemical structure or arrangement of the subunits of NPC might be subtly different along different parts of the nuclear envelope, which would not be obvious from steady state concentrations of individual subunits. If so, it will be important to explain how the heterogeneous distribution of these activities is established or maintained.

Alternatively, perhaps gene targeting to the nuclear periphery is not precise. DNA zip codes could mediate both an interaction with the NPC and homotypic clustering between genes. Chromosomes are constrained by their size, folding and stable association with subnuclear structures. The subnuclear positioning of genes is a product of their position along these polymers. The NPC might serve as a stable surface on which homotypic interactions between genes could occur more efficiently. If so, then the apparently restricted localization of genes at the nuclear periphery might the constraints associated with their position along the chromosome, rather than zip code-mediated positioning. Consistent with the possibility that clustering and interaction with the NPC can be uncoupled, previous targeting to the NPC is sufficient to maintain clustering during S-phase, a period when peripheral localization is lost (Figures 4B & 4C; Brickner and Brickner, 2010).

The clustering we have observed is specific. We have observed clustering between genes that have identical zip codes and not between genes with different zip codes (Figure 3). It remains to be seen if there are zip codes with overlapping distributions. But the available data suggests that, although many genes interact with the NPC, they may be targeted to distinct populations of NPCs by distinct mechanisms. Furthermore, because endogenous genes on different chromosomes that share zip codes cluster together (e.g. INO1 with INO1 and INO1 with TSA2), it raises the fascinating possibility that genes that share a zip code also share factors important for their transcription or mRNA export. Alternatively, clustering of genes with related functions might allow better coordination of their expression. If so, then clustering of genes might serve to couple spatial compartmentalization with functional compartmentalization.

EXPERIMENTAL PROCEDURES

Strains and plasmids

Yeast strains and cloning are described in Extended Experimental Procedures.

Statistical mapping

Statistical mapping was carried out as described (Berger et al., 2008), with modifications detailed in Extended Experimental Procedures.

RFP-LacI + GFP-TetR two dot assay

Plasmid p15816-INO1 was digested with MscI and integrated downstream of INO1 in strains transformed with GFP-Tet repressor (integrated at LEU2; Grund et al., 2008). These strains were then transformed with plasmid pME08 expressing RFP-Lac I under the control of the AHD2 promoter (Jiang et al., 2009) and LacO array plasmids integrated either at TSA2 (p6LacO-TSA2) or at URA3 as follows: p6LacO128 (URA3), p6LacO128-INO1 (URA3:INO1) and p6LacOGRS I 41-75(URA3:GRS I;Ahmed et al., 2010; Brickner and Walter, 2004).

Except for the experiments in Figure 2E and 2F, all experiments were performed with haploid cells. Cells were grown overnight in SDC-Trp (+/− inositol) diluted into fresh media containing 2% ethanol as a carbon source to de-repress expression of RFP-LacI. Cells were fixed 2 times in 4% formaldehyde for 30min and prepared for immunofluorescence using rabbit polyclonal anti-GFP and mouse monoclonal anti-RFP (ab65856, Abcam) antibodies as described (Brickner et al., 2010). The distances between the centers of the dots was measured for ≥100 cells using Zeiss LSM software.

GFP-Lac I large and small dots assay

Plasmid pFS3013 having 256 Lac repressor binding sites was integrated at HSP104 as described (Dieppois et al., 2006) in a strain transformed with GFP-Lac I plasmid pAFS144 (Robinett et al., 1996) and one of the following plasmids having 128 lac repressor binding sites: p6LacO-INO1, p6LacO-GAL1 or p6LacO-GAL2, integrated at INO1, GAL1 or GAL2, respectively as described (Brickner et al., 2007; Brickner and Walter, 2004; Dieppois et al., 2006). Cells were fixed and processed for immunofluorescence against GFP as described (Brickner et al., 2010) and the distance between the two dots was measured using Zeiss LSM software.

EMSA

Cells were grown and permeablized as described (Brickner et al., 2001). After pelleting perimeablized cells, the supernatant was collected and 2µl was added to 20µl gelshift reaction mix (0.5mM DTT 20% glycerol 100mM KCl 20mM HEPES-KOH pH 6.8 0.2mM EDTA 50µg/ml Poly dIdC 0.5nM [32P]-labeled 4×GRS I probe 0.04% bromophenol blue), incubated 15min and separated on 6% native polyacrylamide gels in 0.5× TBE (Invitrogen). Gels were dried on whatman filter paper, exposed to phosphorimager screen overnight and imaged on a Typhoon phosphorimager. Sequences of the DNAs used: 4× GRS I: CTAG-[TCCGGGTTGGATG]4-AGCT; 1× GRS I: GTGTTCCGGGTTGGATGCGGC; 1× mutGRS I: GTGTTCCAAAACCAATGCGGC.

On-line Capillary LC-MS and LC-MS-MS Analysis

GRS I-binding proteins were enriched as described in Extended Experimental Procedures in the Supplementary Information. LC-MS and LC-MS-MS were performed as described previously (Chu et al., 2006) and as detailed in Extended Experimental Procedures.

LCMSMS RAW data files were processed using PAVA (Guan et al., 2011). The centroided peak lists of the CID spectra were searched against a database that consisted of the Swiss-Prot protein database, to which a randomized version had been concatenated (Elias and Gygi, 2007), using Batch-Tag, a program in the University of California San Francisco Protein Prospector version 5.9.2. A precursor mass tolerance of 15 ppm and a fragment mass tolerance of 0.5 Da were used for protein database search. Protein hits are reported with a Protein Prospector protein score ≥22, protein discriminant score ≥0.0 and a peptide expectation value ≤0.01 (Chalkley et al., 2005). This threshold of protein identification parameters did not return any substantial false positive protein hits from the randomized half of the concatenated database.

Chromatin Immunoprecipitation

ChIP of Nup2-TAP was carried out as described (Ahmed et al., 2010; Light et al., 2010) and as detailed in Extended Experimental Procedures.

RT-qPCR

INO1 and ACT1 mRNA levels were quantified by RT-qPCR as described (Brickner et al., 2007).

Highlights.

DNA zip codes are sufficient to target an ectopic locus to the nuclear pore complex

Two different zip codes cause gene-specific inter-chromosomal clustering at the NPC

Put3 transcription factor binds to a zip code to mediate targeting and clustering

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by NIH grant GM080484 and a W.M. Keck Young Scholars in Biomedical Research Award (JHB). SA and WL were each supported by a Rappaport Award for Research Excellence; AT was supported by an Northwestern Undergraduate Research Fellowship; MY was supported by NIH training grant T32 GM008061; FC is supported by the New Hampshire Agricultural Experiment Station and NIFA/USDA H00567; TH was supported by a UNH Summer Undergraduate Research Fellowship; EF is supported by CNRS, Institut Pasteur and ANR-PIRIBIO grant ANR-09-PIRI-0024. The authors thank Dr. Françoise Stutz (University of Geneva), Dr. James Hopper (The Ohio State University) and Dr. Ghislain Cabal (Instituto de Medicina Molecular, Lisboa, Portugal) for sharing plasmids, Daryl Staveness for technical assistance and Dr. Eric Weiss for help with the EMSA experiments.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Supplemental Information

Supplemental Information includes Extended Experimental Procedures, four figures and two tables.

References

- Ahmed S, Brickner DG, Light WH, Cajigas I, McDonough M, Froyshteter AB, Volpe T, Brickner JH. DNA zip codes control an ancient mechanism for gene targeting to the nuclear periphery. Nat Cell Biol. 2010;12:111–118. doi: 10.1038/ncb2011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ahmed S, Brickner JH. A role for DNA sequence in controlling the spatial organization of the genome. Nucleus. 2010;1:402–406. doi: 10.4161/nucl.1.5.12637. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Axelrod JD, Majors J, Brandriss MC. Proline-independent binding of PUT3 transcriptional activator protein detected by footprinting in vivo. Mol Cell Biol. 1991;11:564–567. doi: 10.1128/mcb.11.1.564. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Badis G, Chan ET, van Bakel H, Pena-Castillo L, Tillo D, Tsui K, Carlson CD, Gossett AJ, Hasinoff MJ, Warren CL, et al. A library of yeast transcription factor motifs reveals a widespread function for Rsc3 in targeting nucleosome exclusion at promoters. Mol Cell. 2008;32:878–887. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2008.11.020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bass HW, Marshall WF, Sedat JW, Agard DA, Cande WZ. Telomeres cluster de novo before the initiation of synapsis: a three-dimensional spatial analysis of telomere positions before and during meiotic prophase. J Cell Biol. 1997;137:5–18. doi: 10.1083/jcb.137.1.5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berger AB, Cabal GG, Fabre E, Duong T, Buc H, Nehrbass U, Olivo-Marin JC, Gadal O, Zimmer C. High-resolution statistical mapping reveals gene territories in live yeast. Nat Methods. 2008;5:1031–1037. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.1266. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brickner DG, Brickner JH. Cdk phosphorylation of a nucleoporin controls localization of active genes through the cell cycle. Mol Biol Cell. 2010;21:3421–3432. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E10-01-0065. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brickner DG, Brickner JH. Gene positioning is regulated by phosphorylation of the nuclear pore complex by Cdk1. Cell Cycle. 2011;10:392–395. doi: 10.4161/cc.10.3.14644. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brickner DG, Cajigas I, Fondufe-Mittendorf Y, Ahmed S, Lee PC, Widom J, Brickner JH. H2A.Z-mediated localization of genes at the nuclear periphery confers epigenetic memory of previous transcriptional state. PLoS Biol. 2007;5:e81. doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.0050081. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brickner DG, Light W, Brickner JH. Quantitative localization of chromosomal loci by immunofluorescence. Methods Enzymol. 2010;470:569–580. doi: 10.1016/S0076-6879(10)70022-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brickner JH. Transcriptional memory at the nuclear periphery. Curr Opin Cell Biol. 2009;21:127–133. doi: 10.1016/j.ceb.2009.01.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brickner JH, Blanchette JM, Sipos G, Fuller RS. The Tlg SNARE complex is required for TGN homotypic fusion. J Cell Biol. 2001;155:969–978. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200104093. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brickner JH, Walter P. Gene recruitment of the activated INO1 locus to the nuclear membrane. PLoS Biol. 2004;2:e342. doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.0020342. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown JM, Green J, das Neves RP, Wallace HA, Smith AJ, Hughes J, Gray N, Taylor S, Wood WG, Higgs DR, et al. Association between active genes occurs at nuclear speckles and is modulated by chromatin environment. J Cell Biol. 2008;182:1083–1097. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200803174. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown JM, Leach J, Reittie JE, Atzberger A, Lee-Prudhoe J, Wood WG, Higgs DR, Iborra FJ, Buckle VJ. Coregulated human globin genes are frequently in spatial proximity when active. J Cell Biol. 2006;172:177–187. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200507073. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cabal GG, Genovesio A, Rodriguez-Navarro S, Zimmer C, Gadal O, Lesne A, Buc H, Feuerbach-Fournier F, Olivo-Marin JC, Hurt EC, et al. SAGA interacting factors confine sub-diffusion of transcribed genes to the nuclear envelope. Nature. 2006;441:770–773. doi: 10.1038/nature04752. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Capelson M, Liang Y, Schulte R, Mair W, Wagner U, Hetzer MW. Chromatin-bound nuclear pore components regulate gene expression in higher eukaryotes. Cell. 2010;140:372–383. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2009.12.054. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Casolari JM, Brown CR, Drubin DA, Rando OJ, Silver PA. Developmentally induced changes in transcriptional program alter spatial organization across chromosomes. Genes Dev. 2005;19:1188–1198. doi: 10.1101/gad.1307205. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Casolari JM, Brown CR, Komili S, West J, Hieronymus H, Silver PA. Genome-wide localization of the nuclear transport machinery couples transcriptional status and nuclear organization. Cell. 2004;117:427–439. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(04)00448-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chalkley RJ, Baker PR, Huang L, Hansen KC, Allen NP, Rexach M, Burlingame AL. Comprehensive analysis of a multidimensional liquid chromatography mass spectrometry dataset acquired on a quadrupole selecting, quadrupole collision cell, time-of-flight mass spectrometer: II. New developments in Protein Prospector allow for reliable and comprehensive automatic analysis of large datasets. Molecular & cellular proteomics : MCP. 2005;4:1194–1204. doi: 10.1074/mcp.D500002-MCP200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chu F, Nusinow DA, Chalkley RJ, Plath K, Panning B, Burlingame AL. Mapping post-translational modifications of the histone variant MacroH2A1 using tandem mass spectrometry. Molecular & cellular proteomics : MCP. 2006;5:194–203. doi: 10.1074/mcp.M500285-MCP200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cooper JP, Watanabe Y, Nurse P. Fission yeast Taz1 protein is required for meiotic telomere clustering and recombination. Nature. 1998;392:828–831. doi: 10.1038/33947. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dernburg AF, Broman KW, Fung JC, Marshall WF, Philips J, Agard DA, Sedat JW. Perturbation of nuclear architecture by long-distance chromosome interactions. Cell. 1996;85:745–759. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81240-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- des Etages SA, Falvey DA, Reece RJ, Brandriss MC. Functional analysis of the PUT3 transcriptional activator of the proline utilization pathway in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Genetics. 1996;142:1069–1082. doi: 10.1093/genetics/142.4.1069. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dieppois G, Iglesias N, Stutz F. Cotranscriptional recruitment to the mRNA export receptor Mex67p contributes to nuclear pore anchoring of activated genes. Mol Cell Biol. 2006;26:7858–7870. doi: 10.1128/MCB.00870-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Duan Z, Andronescu M, Schutz K, McIlwain S, Kim YJ, Lee C, Shendure J, Fields S, Blau CA, Noble WS. A three-dimensional model of the yeast genome. Nature. 2010;465:363–367. doi: 10.1038/nature08973. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Egecioglu D, Brickner JH. Gene positioning and expression. Curr Opin Cell Biol. 2011;23:338–345. doi: 10.1016/j.ceb.2011.01.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Elias JE, Gygi SP. Target-decoy search strategy for increased confidence in large-scale protein identifications by mass spectrometry. Nature methods. 2007;4:207–214. doi: 10.1038/nmeth1019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gard S, Light W, Xiong B, Bose T, McNairn AJ, Harris B, Fleharty B, Seidel C, Brickner JH, Gerton JL. Cohesinopathy mutations disrupt the subnuclear organization of chromatin. J Cell Biol. 2009;187:455–462. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200906075. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gotta M, Gasser SM. Nuclear organization and transcriptional silencing in yeast. Experientia. 1996;52:1136–1147. doi: 10.1007/BF01952113. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gotta M, Laroche T, Formenton A, Maillet L, Scherthan H, Gasser SM. The clustering of telomeres and colocalization with Rap1, Sir3, and Sir4 proteins in wild-type Saccharomyces cerevisiae. J Cell Biol. 1996;134:1349–1363. doi: 10.1083/jcb.134.6.1349. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grund SE, Fischer T, Cabal GG, Antunez O, Perez-Ortin JE, Hurt E. The inner nuclear membrane protein Src1 associates with subtelomeric genes and alters their regulated gene expression. J Cell Biol. 2008;182:897–910. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200803098. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guan S, Price JC, Prusiner SB, Ghaemmaghami S, Burlingame AL. A data processing pipeline for mammalian proteome dynamics studies using stable isotope metabolic labeling. Mol Cell Proteomics. 2011 doi: 10.1074/mcp.M111.010728. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huh WK, Falvo JV, Gerke LC, Carroll AS, Howson RW, Weissman JS, O'Shea EK. Global analysis of protein localization in budding yeast. Nature. 2003;425:686–691. doi: 10.1038/nature02026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Iborra FJ, Pombo A, Jackson DA, Cook PR. Active RNA polymerases are localized within discrete transcription "factories' in human nuclei. J Cell Sci. 1996;109(Pt 6):1427–1436. doi: 10.1242/jcs.109.6.1427. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jiang F, Frey BR, Evans ML, Friel JC, Hopper JE. Gene activation by dissociation of an inhibitor from a transcriptional activation domain. Mol Cell Biol. 2009;29:5604–5610. doi: 10.1128/MCB.00632-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kalverda B, Pickersgill H, Shloma VV, Fornerod M. Nucleoporins directly stimulate expression of developmental and cell-cycle genes inside the nucleoplasm. Cell. 2010;140:360–371. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2010.01.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lanzuolo C, Roure V, Dekker J, Bantignies F, Orlando V. Polycomb response elements mediate the formation of chromosome higher-order structures in the bithorax complex. Nat Cell Biol. 2007;9:1167–1174. doi: 10.1038/ncb1637. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Laroche T, Martin SG, Gotta M, Gorham HC, Pryde FE, Louis EJ, Gasser SM. Mutation of yeast Ku genes disrupts the subnuclear organization of telomeres. Curr Biol. 1998;8:653–656. doi: 10.1016/s0960-9822(98)70252-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Light WH, Brand V, Brickner DG, Brickner JH. Interaction of a DNA zip code with the nuclear pore complex promotes H2A.Z incorporation and INO1 transcriptional memory. Mol Cell. 2010;40:112–125. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2010.09.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luthra R, Kerr SC, Harreman MT, Apponi LH, Fasken MB, Ramineni S, Chaurasia S, Valentini SR, Corbett AH. Actively transcribed GAL genes can be physically linked to the nuclear pore by the SAGA chromatin modifying complex. J Biol Chem. 2007;282:3042–3049. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M608741200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MacIsaac KD, Wang T, Gordon DB, Gifford DK, Stormo GD, Fraenkel E. An improved map of conserved regulatory sites for Saccharomyces cerevisiae. BMC Bioinformatics. 2006;7:113. doi: 10.1186/1471-2105-7-113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McCullagh E, Seshan A, El-Samad H, Madhani HD. Coordinate control of gene expression noise and interchromosomal interactions in a MAP kinase pathway. Nat Cell Biol. 2010;12:954–962. doi: 10.1038/ncb2097. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meldi L, Brickner JH. Compartmentalization of the nucleus. Trends Cell Biol. 2011;21:701–708. doi: 10.1016/j.tcb.2011.08.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Menon BB, Sarma NJ, Pasula S, Deminoff SJ, Willis KA, Barbara KE, Andrews B, Santangelo GM. Reverse recruitment: the Nup84 nuclear pore subcomplex mediates Rap1/Gcr1/Gcr2 transcriptional activation. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2005;102:5749–5754. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0501768102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Molnar M, Kleckner N. Examination of interchromosomal interactions in vegetatively growing diploid Schizosaccharomyces pombe cells by Cre/loxP site-specific recombination. Genetics. 2008;178:99–112. doi: 10.1534/genetics.107.082826. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Robinett CC, Straight A, Li G, Willhelm C, Sudlow G, Murray A, Belmont AS. In vivo localization of DNA sequences and visualization of large-scale chromatin organization using lac operator/repressor recognition. J Cell Biol. 1996;135:1685–1700. doi: 10.1083/jcb.135.6.1685. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scherthan H, Weich S, Schwegler H, Heyting C, Harle M, Cremer T. Centromere and telomere movements during early meiotic prophase of mouse and man are associated with the onset of chromosome pairing. J Cell Biol. 1996;134:1109–1125. doi: 10.1083/jcb.134.5.1109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schmid M, Arib G, Laemmli C, Nishikawa J, Durussel T, Laemmli UK. Nup-PI: the nucleopore-promoter interaction of genes in yeast. Mol Cell. 2006;21:379–391. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2005.12.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schoenfelder S, Sexton T, Chakalova L, Cope NF, Horton A, Andrews S, Kurukuti S, Mitchell JA, Umlauf D, Dimitrova DS, et al. Preferential associations between co-regulated genes reveal a transcriptional interactome in erythroid cells. Nat Genet. 2010;42:53–61. doi: 10.1038/ng.496. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Siddiqui AH, Brandriss MC. The Saccharomyces cerevisiae PUT3 activator protein associates with proline-specific upstream activation sequences. Mol Cell Biol. 1989;9:4706–4712. doi: 10.1128/mcb.9.11.4706. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Taddei A. Active genes at the nuclear pore complex. Curr Opin Cell Biol. 2007;19:305–310. doi: 10.1016/j.ceb.2007.04.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Taddei A, Van Houwe G, Hediger F, Kalck V, Cubizolles F, Schober H, Gasser S. Nuclear pore association confers optimal expression levels for an inducible yeast gene. Nature. 2006;441:774–778. doi: 10.1038/nature04845. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tanizawa H, Iwasaki O, Tanaka A, Capizzi JR, Wickramasinghe P, Lee M, Fu Z, Noma K. Mapping of long-range associations throughout the fission yeast genome reveals global genome organization linked to transcriptional regulation. Nucleic acids research. 2010;38:8164–8177. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkq955. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thompson M, Haeusler RA, Good PD, Engelke DR. Nucleolar clustering of dispersed tRNA genes. Science. 2003;302:1399–1401. doi: 10.1126/science.1089814. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tolhuis B, Blom M, Kerkhoven RM, Pagie L, Teunissen H, Nieuwland M, Simonis M, de Laat W, van Lohuizen M, van Steensel B. Interactions among Polycomb domains are guided by chromosome architecture. PLoS Genet. 2011;7:e1001343. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1001343. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xu M, Cook PR. The role of specialized transcription factories in chromosome pairing. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2008a;1783:2155–2160. doi: 10.1016/j.bbamcr.2008.07.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xu M, Cook PR. Similar active genes cluster in specialized transcription factories. J Cell Biol. 2008b;181:615–623. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200710053. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhu C, Byers KJ, McCord RP, Shi Z, Berger MF, Newburger DE, Saulrieta K, Smith Z, Shah MV, Radhakrishnan M, et al. High-resolution DNA-binding specificity analysis of yeast transcription factors. Genome Res. 2009;19:556–566. doi: 10.1101/gr.090233.108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.