Abstract

Chemical biology promises discovery of new and unexpected mechanistic pathways, protein functions and disease targets. Here, we probed the mechanism-of-action and protein targets of 3,5-disubstituted isoxazoles (Isx), cardiomyogenic small-molecules that target Notch-activated epicardium-derived cells (NECs) in vivo and promote functional recovery after myocardial infarction (MI). Mechanistic studies in NECs led to an Isx-activated Gq protein-coupled receptor (GqPCR) hypothesis tested in a cell-based functional target screen for GPCRs regulated by Isx. This screen identified one agonist hit, the extracellular proton/pH-sensing GPCR GPR68, confirmed through genetic gain- and loss-of-function. Overlooked until now, GPR68 expression and localization were highly regulated in early post-natal and adult post-infarct mouse heart, where GPR68-expressing cells accumulated subepicardially. Remarkably, GPR68-expressing cardiomyocytes established a proton sensing cellular “buffer zone” surrounding the MI. Isx pharmacologically regulated gene expression (mRNAs and miRs) in this GPR68 enriched border zone, driving cardiomyogenic and pro-survival transcriptional programs in vivo. In conclusion, we tracked a (µM) bioactive small-molecule’s mechanism-of-action to a candidate target protein, GPR68, and validated this target as a previously unrecognized regulator of myocardial cellular responses to tissue acidosis, setting the stage for future (nM) target-based drug lead discovery.

Chemical biology promises discovery of new and unexpected functions for cells, genes, proteins and biochemical pathways using small-molecule probes that are unbiased with regard to mechanistic preconceptions. Treating bioactive small-molecules as mechanistic “black boxes” heightens their discovery promise. Yet, despite advances in chemical informatics, proteomics and affinity chromatography technologies, target identification (target ID) remains a major bottleneck in chemical biology science (1, 2). Successful target ID is particularly important if the goal is drug discovery/development because identifying synthetic small-molecule protein targets or receptors allows structure-activity relationship (SAR) studies and pharmacological optimization, moving forward, to be based on direct binding assays or target biochemistry rather than downstream cellular events like reporter gene assays. Target ID is a crucial intermediary and enabling step for advancing primary µM hits, which are useful as chemical probes but unlikely to become drugs, towards “druggable” nM leads recovered from chemical structure focused and target-based secondary screens (Supplemental Fig. 1a).

Our stem cell-modulator (gene-activating) small-molecules remain mechanistic black boxes (3). Among our most promising drug-like hits is a family of 3,5-disubstituted isoxazole small-molecules (Isx) with differentiating function in hippocampal neural progenitors (4), malignant glioma (5) and pancreatic β (6) as well as P19CL6 embryonal carcinoma cells (7). Most recently, despite requiring µM concentrations for function in cell-based assays and non-ptimal pharmacokinetics properties, we confirmed Isx efficacy in vivo in mice. Delivered as a once daily intra-peritoneal (ip) injection, Isx activated distinctive muscle transcriptional programs in Notch-activated epicardium-derived cells (NECs) – a rare endogenous adult cardiac progenitor-like cell population (7–9). Moreover, Isx improved ventricular function in the early phase (1st week) after myocardial infarction (MI) (9). Discovering Isx’s mode-of-action and target is the critical next step for advancing this promising small-molecule towards drug discovery.

Myocardial acidosis is a central pathophysiological feature of ischemic heart disease. Occluding a major coronary vessel gives rise to focal infarction with cardiomyocyte death in a core region and partially reversible ischemic injury at the infarct’s leading edge (the border zone or BZ). Salvaging BZ cardiomyocytes is the fundamental goal of early invasive revascularization strategies in acute coronary care. Falling pH is one of the earliest (within seconds) biomarkers of myocardial ischemia and is caused by cardiomyocytes rapidly switching to anaerobic (lactate-producing) metabolism, coupled with decreased circulatory clearance of lactate and other acidic metabolic byproducts. Protons accumulating with tissue acidosis can function as signaling molecules through a family of proton sensing G protein-coupled receptors (GPCRs) activated by acidic extracellular pH (~6.4–6.8); this receptor family includes G2A, GPR4, TDAG8 and OGR1 (also known as GPR68) (10–13). Myocardium’s metabolic properties make it one the most acidic (and acidosis prone) tissues in the body, yet proton sensing GPCRs have never been studied in this tissue (14).

Here, our mechanistic and target ID studies pointed towards a proton sensing GPCR that, remarkably, was highly regulated in ischemic myocardium, upregulated precisely when and where an acidosis-sensing (and Isx small-molecule targeted) pro-survival function would be critically needed. Our results validate the promise of the chemical biology discovery cycle (Supplemental Fig. 1a) for identifying new mechanisms and disease targets.

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

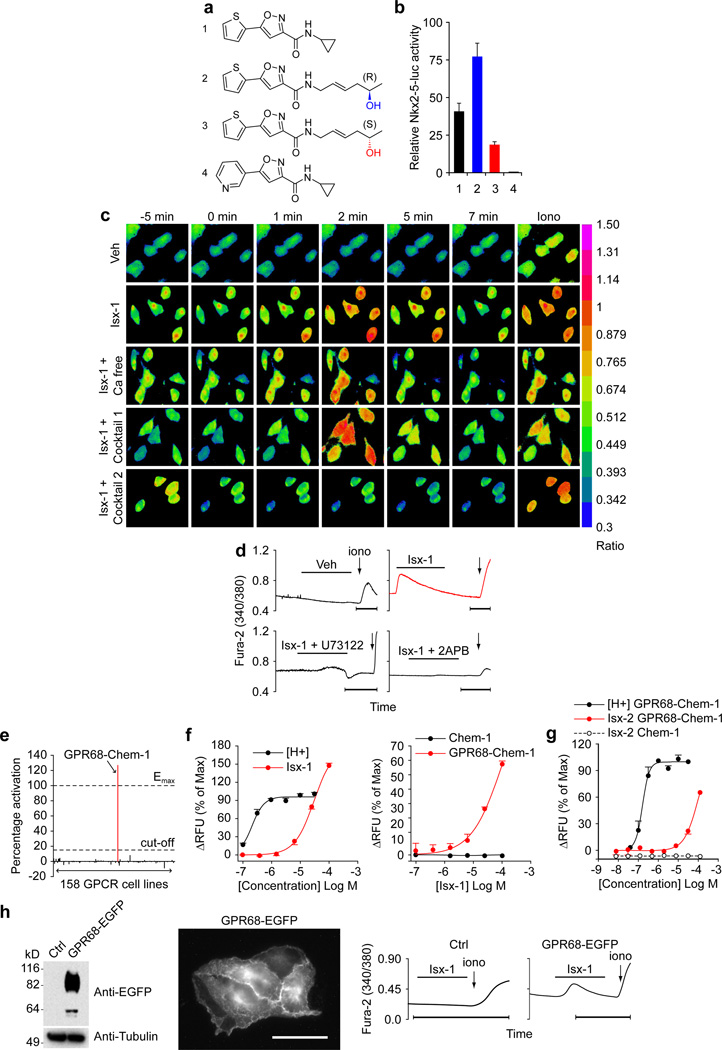

Isx stereoselectivity implies a ligand-receptor mechanism in target cells

Despite defining several important pharmacological functions in a broad spectrum of progenitor-like cells (3–6), even in vivo (9), Isx’s precise mechanism-of-action has remained elusive. Ncyclopropyl-5-(thiophen-2-yl)-isoxazole-3-carboxamide, our top Isx lead (henceforth referred to as “Isx-1”; Fig. 1a), robustly activated Nkx2-5-luc-BAC in NECs, increasing luciferase specific activity (per µg protein) ~40-fold (Fig. 1b). In a concerted effort to identify more potent leads, we synthesized a library of Isx analogs (~100 compounds) based on the structure of Isx-1 through an iterative ligand-based medicinal chemistry approach. Out of this focused library, we identified a new lead containing a chiral (R)-homo-allylic alcohol amide side chain (Isx-2) (Fig. 1a) that was even more effective than Isx-1 in Nkx2-5-luc-BAC NECs, activating the reporter gene ~75-fold over vehicle (Fig. 1b). Realizing that enantiomers can have significantly different affinities for a given biological target (15), we also synthesized the corresponding (S)-enantiomer of this new lead (Isx-3) (Fig. 1a) and compared both enantiomers in Nkx2-5-luc-BAC NECs (Fig. 1b). Indeed, under identical experimental conditions, Isx-3 had markedly reduced bioactivity compared to Isx-2 (Fig. 1b). Additionally, from our library we also identified an analog suitable as a negative control for our assays by demonstrating that substituting a pyridine for the thiophene ring in Isx-1 (Isx-4) (Fig. 1a) abolished function (Fig. 1b). Thus, otherwise identical stereoisomers (Isx-2 and -3) had substantially different biological activities providing strong evidence of a very discrete and stereoselective ligand/receptor interaction between Isx and its cognate target protein.

Figure 1. Isx-triggered endoplasmic reticulum Ca2+ release and GPCR screen that identified candidate Isx target GPR68 and independent validation.

(a) Chemical structures of Isx compounds used in this study: lead-cyclopropyl compound (Isx-1), chiral (R)-homo-allylic alcohol (Isx-2) and chiral (S)-homo-allylic alcohol (Isx-3), and the non-active pyridine analog (Isx-4). (b) Differential activity of Isx compounds shown in (a) in Nkx2-5-luc-BAC NECs. (c) [Ca2+]i signaling triggered by Isx-1 in NECs using Fura-2AM ratiometric imaging (Ca free = Ca2+ free media; Cocktail 1 = 10 µM Nifedipine, 100 µM La3+ and 10 µM SKF-96365; Cocktail 2 = 100 µM Ryanodine, 30 µM 2-APB and 5 µM U73122). (d) Examples of Fura-2AM ratiometric [Ca2+]i tracings of NECs treated with vehicle, Isx-1 or Isx-1 plus inhibitors 5 µM U73122 or 30 µM 2-APB (bar = 1 minute). (e) Identification of GPR68-Chem-1 cells as unique agonist hit in Fluo-4 Ca2+ flux screen of 158 different recombinant GPCR expressing cell lines (FLIPR TETRA, Millipore GPCR-Profiler) (Emax is maximal activation by control ligand (low pH/protons in this case) and “cut-off” is percentage activation criteria for positive hit in screen). (f) Fluo-4 Ca2+ flux signaling activated by Isx-1 is dose-responsive, distinctive from activation by low pH (protons, H+), and is absent in parental Chem-1 cells lacking GPR68. (g) Fluo-4 Ca2+ flux signaling is also activated by Isx-2 ((R)-enantiomer) and is dose-responsive, with activation curve that is distinctive from low pH/protons. (h) Characterization of a GPR68-EGFP fusion protein-expressing HeLa cell line by protein blot (1st panel) and EGFP fluorescence (2nd panel; scale bar = 20 µm); Fura-2AM ratiometric tracing of Isx-1 triggered [Ca2+]i signaling in GPR68-EGFP fusion protein expressing (4th panel) but not parental HeLa cells (Ctrl) (3rd panel).

Isx triggers endoplasmic reticulum Ca2+ release through GPCR activation

While systematically surveying candidate modes-of-action, we asked whether Isx-1 regulated intracellular Ca2+ flux in NECs. Indeed, Isx-1 triggered an intracellular Ca2+ transient [Ca2+]i in NECs that was rapid in upstroke, high in amplitude and short in duration, with [Ca2+]i quickly returning to baseline (without drug-washout) (Fig. 1c and d). Importantly, this intracellular Ca2+ transient was distinctive from the signal previously reported in adult hippocampal neural progenitors (4). We localized the source of this Ca2+ release by removing Ca2+ from the media (Ca free), adding Ca2+ influx inhibitors (cocktail 1: Nifedipine, La3+ and SKF96365) or blockers of Ca2+ release from intracellular stores (cocktail 2: U73122, 2-APB and Ryanodine). Only cocktail 2 blocked the Isx-1 triggered [Ca2+]i spike in NECs (Fig. 1c). More specifically, 2-APB (an inositol 1,4,5-triphosphate receptor antagonist) and U73122 (a GqPCR signaling inhibitor) each independently blocked the Isx-1 induced [Ca2+]i spike in NECs (Fig. 1d), mapping the origin of Isx-1’s signal to endoplasmic reticulum Ca2+ release through GPCR activation. These results strongly suggested an Isx-GPCR mechanistic pathway.

Functional target screen for GPCRs regulated by Isx identifies GPR68

We tested the Isx-GPCR hypothesis by screening a library of recombinant GPCR over-expressing cell lines in a functional assay based on Fluo-4 Ca2+ flux (FLIPRTETRA; Millipore GPCR-Profiler). Millipore’s GPCR-Profiler screen, covering all receptor classes and ligand families, simultaneously evaluated 158 cell lines for Isx-1 mediated agonist, antagonist and allosteric modulator Ca2+ signaling activity. The Isx-1 agonist screen yielded a single hit: GPR68-Chem-1 cells engineered to over-express human GPR68 (a Gq protein-coupled receptor) in rat Chem-1 cells (which express Gα15, a promiscuous G protein that enhances GPCR coupling to downstream Ca2+ signaling pathways) (Fig. 1e). The kinetics of Isx-1 mediated Ca2+ signaling in GPR68-Chem-1 cells was most consistent with a direct agonist rather than a downstream effect. Importantly, Isx-1 is a neutral molecule (Fig. 1a), so its effects were not mediated through pH changes. We did a number of secondary experiments to confirm and validate this screen hit. For example, we demonstrated dose-responsive activation of GPR68-Chem-1 cell Ca2+ signaling by Isx-1 (compared side-by-side with protons [H+], the control ‘ligand’ for this pH sensing GPCR) (Fig. 1f). In addition, we demonstrated that Isx-1 triggered Ca2+ signaling in GPR68-Chem-1 cells, but not in parental Chem-1 cells (lacking over-expressed GPR68) (Fig. 1f). We independently confirmed that a second structurally distinct Isx analog, Isx-2, the chiral (R)-homo-allylic alcohol amide (Fig. 1a), activated Ca2+ signaling in this cell line (Fig. 1g). Like Isx-1, Isx-2’s activity was dose-responsive in GPR68-Chem-1 but not parental Chem-1 cells (Fig. 1g). Thus, our cell-based screen for GPCRs regulated by Isx identified a single hit, GPR68, an unexpected candidate target with no known function in the heart.

Genetic gain-of-function validates Isx candidate target

We confirmed and extended the Millipore GPCR-Profiler and follow-up studies by independently establishing our own HeLa cell line that over-expressed a GPR68-EGFP fusion protein (11), which localized predominantly to plasma membrane (Fig. 1h). Isx-1 activated Ca2+ signaling (increased [Ca2+]i) in GPR68-EGFP HeLa but not in control (parental) cells (Fig. 1h). Notably, the morphology and kinetics of the Isx-1 triggered [Ca2+]i release in GPR68-EGFP HeLa cells (Fig. 1h) was indistinguishable from the native Isx-1 triggered [Ca2+]i signal in NECs (Fig. 1d). These gain-of-function experiments in HeLa cells independently corroborated the results of the Millipore GPCR-Profiler screen.

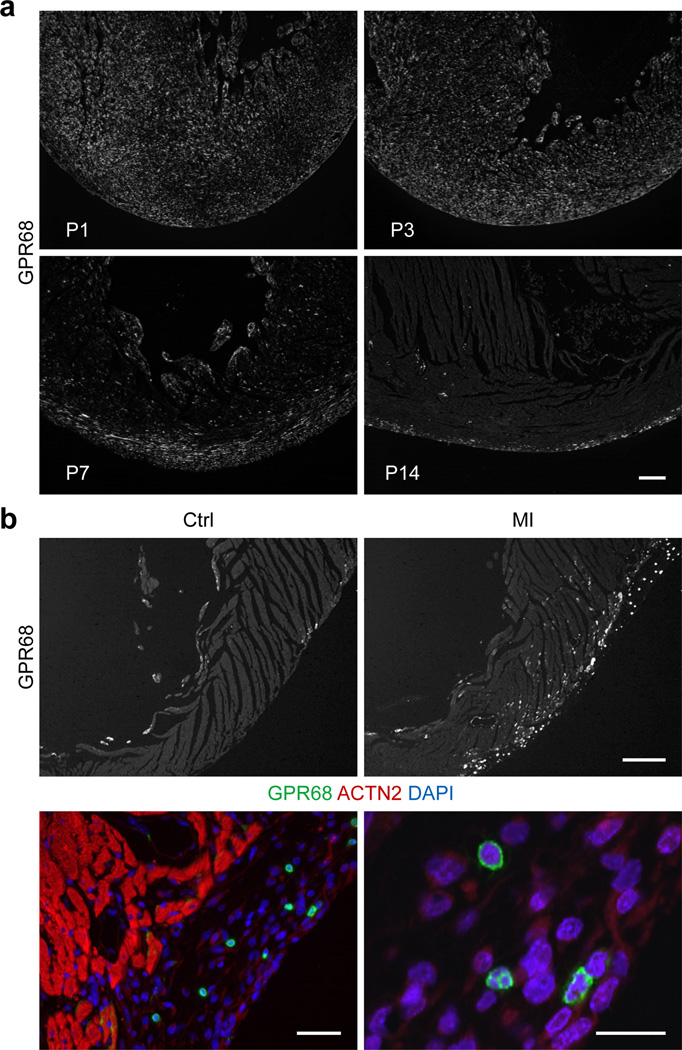

GPR68-expressing cells localize to postnatal and injury-activated subepicardium

Regulated expression of genes in developmental or pathophysiological time and space provides evidence of that gene product’s functional importance. GPR68 expression in myocardium – one of the most acidosis-prone tissues in the body (16) – had not been previously characterized. As a starting point, we evaluated GPR68 expression in mice during the first two weeks of postnatal life, a period of rapid structural and physiological maturation, using an antibody validated in GPCR immunohistochemistry (IHC). We observed widespread GPR68 staining in newborn mouse myocardium, which is comprised almost entirely of cardiomyocytes, at days 1 and 3 of postnatal life (Fig. 2a, upper panels). However, between postnatal days 7 and 14, mouse heart GPR68 staining increasingly concentrated in subepicardium (Fig. 2a, lower panels). Thus, GPR68-expressing cells progressively localized to neonatal mouse subepicardium.

Figure 2. Progressive accumulation of GPR68-expressing cells in neonatal and injury-activated subepicardium.

(a) IHC localization of GPR68-expressing cells in neonatal mouse heart at postnatal days 1, 3, 7 and 14 (from upper left to lower right panels) (scale bar = 50 µm). (b) Accumulation of GPR68-expressing cells in injury-activated subepicardium of adult mouse heart (upper right hand panel) compared to control/uninjured heart (upper left hand panel) by IHC (scale bar = 200 µm); higher magnification images of GPR68-expressing cells (green) in the injury-activated subepicardial region of day 7 post-infarct adult mouse heart, co-stained with ACTN2 (red) and DAPI (blue) (scale s = 20 µm).

MI “activates” subepicardium, amplifying and recruiting subepicardial cells like NECs into tissue repair pathways (7, 17). Therefore, to provide evidence for GPR68’s possible role in epicardium-mediated myocardial injury-repair, we studied GPR68-expressing cells in this tissue. Indeed, MI markedly increased the number of GPR68-expressing cells in the injury-expanded subepicardium (Fig. 2b, right upper panel). In control (uninjured) hearts, we detected rare GPR68-expressing cells and these localized mostly to endocardium (Fig. 2b, left upper panel). After MI, we observed numerous distinctive small round cells expressing high levels of GPR68 throughout the subepicardium (Fig. 2b, lower panels). Thus, GPR68-expressing cells localized to injury-activated subepicardium, implicating GPR68 – the proton sensing and candidate Isx receptor – in cardiac repair pathways that involve epicardium-derived cells.

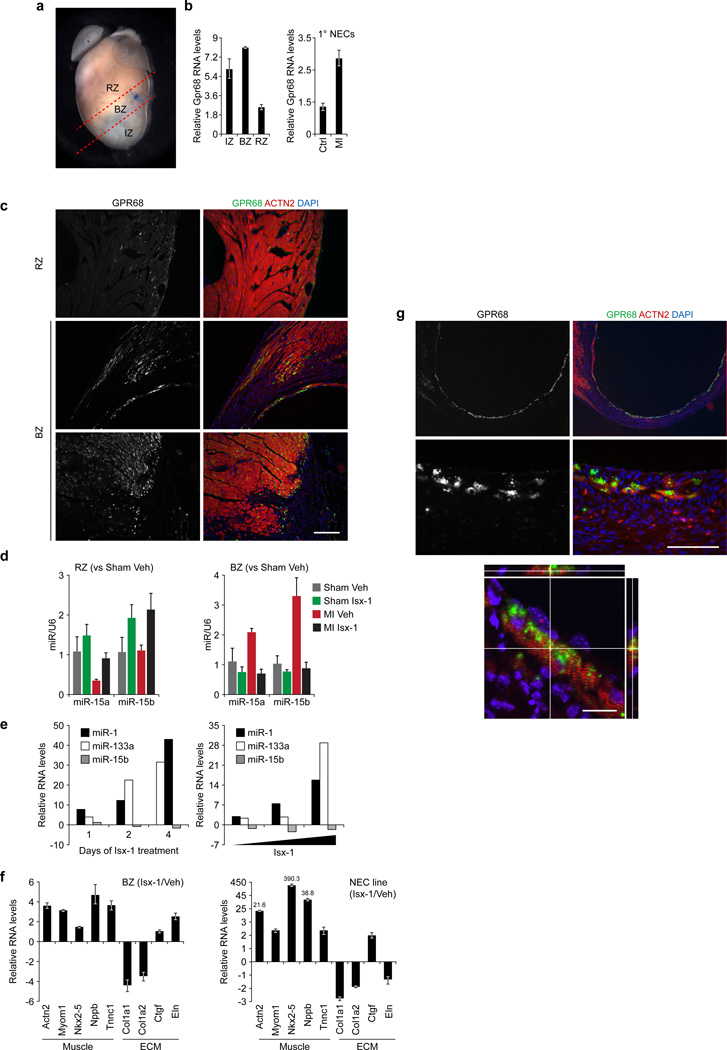

A GPR68-expressing buffer zone encapsulates the ischemic/acidic infarct

The adult mouse heart’s response to experimental left anterior coronary artery ligation MI is a complex and dynamic. We expanded our analysis of GPR68 in MI injured myocardium by dividing post-infarct tissue into three discrete zones, by convention – the ischemic (IZ), border (BZ) and remote zones (RZ) (Fig. 3a). When compared to normal myocardium, at one week after injury, all three zones had increased Gpr68 mRNA levels, more than 5-fold in IZ and BZ, measured by quantitative polymerase chain reaction (QPCR) (Fig. 3b, left hand graph). We reinforced this result by examining NECs from post-infarct or control hearts. Indeed, compared with uninjured controls, NECs from day 7 post-infarct hearts had increased Gpr68 mRNA levels by QPCR (Fig. 3b, right hand graph). Thus, at the gene expression level, MI increased Gpr68 in BZ and, more specifically, in NEC heart-repair cells (18).

Figure 3. Isx targets the GPR68-enriched MI BZ and drives cardiomyocyte-sparing gene programs.

(a) Post-MI adult mouse heart demonstrating conventional subdivision of heart into remote zone (RZ), border zone (BZ), which includes the suture on the left anterior descending coronary artery, and infarct zone (IZ). (b) Upregulation of Gpr68 mRNA by QPCR in IZ, BZ and RZ of the adult mouse heart at day 7 post-MI (compared to sham operation) (left hand panel) and upregulation of Gpr68 mRNA in primary NECs at day 7 post-MI (right hand panel). (c) IHC localization of GPR68 in the RZ (top panels) and BZ (middle and bottom panels) in MI injured adult mouse heart (left hand panels – GPR68 alone; right hand panels – GPR68 (green) costained with ACTN2 (red) and DAPI (blue)) (scale bar = 50 µm). (d) Regulation of miRs-15a and -15b by QPCR in RZ (left hand graph) or BZ (right hand graph) tissues of 4 mouse cohorts (sham or MI treated with Isx-1 or vehicle; sham-vehicle n = 2, sham-Isx-1 n = 3, MI-vehicle n = 3 and MI-Isx-1 n = 5) at day 7. (e) Time- (left hand panel) and dose-dependent (right hand panel) regulation of myogenic miRs-1 and -133a and pro-apoptotic miR-15b in Isx-1 treated NECs. (f) Reciprocal regulation of cardiomyogenic (Actn2, Myom1, Nkx2-5, Nppb and Tnnc1) and extracellular matrix remodeling/fibrosis (Col1a1 and Col1a2, Ctgf and Eln) genes by QPCR in BZ tissue RNA from Isx-1 versus vehicle treated MI mice (n=2 mice per group) (left panel); expression analysis of same gene set in vitro in 4-day Isx-1 treated versus untreated NECs (right panel). (g) IHC localization of GPR68-expressing cardiomyocytes in the infarct zone in MI adult mouse heart (left hand panels – GPR68 alone; right hand panels – GPR68 (green) co-stained with ACTN2 (red) and DAPI (blue)), at low (top panels) and high (bottom panels) magnification (scale bar = 200 µm) and confocal microscopy of single GPR68-expressing cardiomyocyte (bottom panel, scale bar = 20 µm).

Returning to GPR68 IHC, we corroborated these QPCR data by localizing GPR68 in post-MI adult mouse heart, comparing RZ and BZ. At 7 days post-infarct, compared with RZ (Fig. 3c, upper panels), BZ had markedly increased GPR68 expression (Fig. 3c, remaining panels). The majority of GPR68-expressing BZ cells appeared to be cardiomyocytes, confirmed by confocal microscopy (see below). This unique distribution of GPR68-expressing cells in the BZ and injury-activated epicardium established a proton sensing “cellular buffer zone” at the boundary of spared myocardium, three-dimensionally shielding viable myocardium from the ischemic/acidic infarct zone (see model, Supplemental Fig. 1b).

Isx drives cardiomyocyte-sparing gene programs in GPR68-expressing BZ in vivo

As a myocardial region enriched with GPR68-expressing cells, MI BZ should be highly responsive to Isx’s in vivo pharmacological actions. We focused here on pro-apoptotic miR-15, a key regulator of ischemic cardiomyocyte death in the MI BZ (19). We evaluated miR-15a and miR-15b levels in RNA isolated from RZ and BZ tissues of a cohort of mice, using QPCR to measure transcript levels. We compared 4 treatment arms: sham operation versus MI and Isx-1 versus vehicle treatment for 7 days, starting on post-operative day 1 (Fig. 3d). After 7 days, Isx-1 upregulated miRs-15a and -15b in RZ, in sham and MI mice (Fig. 3d, left hand panel). In contrast, in MI BZ, Isx-1 completely blocked the normally observed induction of miRs-15a and - 15b (19). Correspondingly, Isx-1 negatively regulated pro-apoptotic miR-15b and reciprocally increased myogenic miRs-1 and -133a in a time (Fig. 3e, left hand panel) and dose dependent manner (Fig. 3e, right hand panel). These data demonstrated that Isx pharmacologically regulated miR gene expression – in a direction that favored cardiomyocyte survival – in the proton sensing “cellular buffer zone” surrounding the infarct in vivo.

Next, we focused on Isx-1’s cardiomyogenic pharmacological signal in MI BZ in vivo. Isx-1 therapy for 7 days post-infarct increased muscle [α-actinin (Actn2), myomesin-1 (Myom1), Nkx2-5, brain natriuretic peptide (Nppb) and troponin C (Tnnc1)] and, conversely, decreased collagen (Col1a1, Col1a2) transcript levels in vivo (Fig. 3f, left hand panel). As controls, we observed unchanged connective tissue growth factor (Ctgf) or increased elastin (Eln) extracellular matrix (ECM) transcript levels in Isx-1 treated MI BZ tissue in vivo (Fig. 3f, left hand panel). Furthermore, we confirmed these in vivo results in cultured NECs (Fig. 3f, right hand panel). With the exception of elastin, the direction of gene expression changes induced by Isx-1 in NECs mirrored the QPCR results observed in MI BZ (Fig. 3f, right and left hand panels). Confirming that Isx-1 induced mRNA changes indeed translated into changes in protein levels, Isx-1 concordantly upregulated CTGF protein and mRNA in cultured NECs (Fig. 3f, right hand panel and Supplemental Fig. 2). Taken together, these data demonstrated that Isx-1 indeed targeted GPR68-expressing MI BZ in vivo, driving pro-survival and cardiomyogenic transcriptional programs, and that cultured NECs, for the most part, modeled these Isx-1 mediated transcriptional effects in vitro.

MI-spared cardiomyocytes express high levels of GPR68

Our data thus far suggested that GPR68 – normally expressed at only very low levels but upregulated following injury, specifically in BZ – transduced pro-survival and cardiomyogenic signals in the heart. We obtained additional evidence for GPR68’s cardioprotective function by IHC in MI mice (Fig. 3g). We observed a thin rim of surviving cardiomyocytes near the endocardial surface of a large transmural apical MI (Fig. 3g, upper panels). When viewed at increasingly higher magnification (Fig. 3g, lower panels), it became evident that each and every surviving cardiomyocyte in this region expressed high levels of GPR68. These expression data suggested that GPR68 conferred a survival advantage to cardiomyocytes at the MI frontier. We used confocal microscopy to confirm that GPR68 localized to cardiomyocytes (Fig. 3g, bottom panel). Thus, MI-spared cardiomyocytes expressed high levels of GPR68, providing a mechanistic hypothesis for how Isx-1 might have regulated cardiac function after MI in vivo(9).

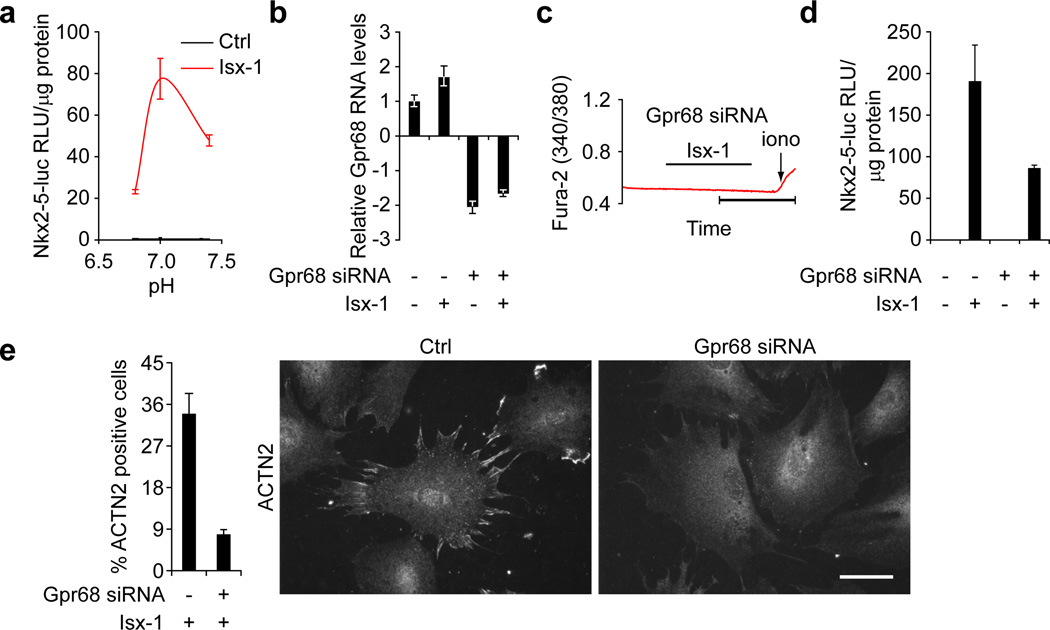

GPR68 is required for Isx’s cardiomyogenic function in NECs

We used genetic loss-of-function in NECs to confirm GPR68’s role in Isx-1 triggered Ca2+ signaling, transcriptional activation and cardiomyogenic differentiation. First, moderate extracellular acidosis (pH 7.0) mimicked Isx-1’s effects on NEC morphology (flattening), suggesting that protons and Isx were acting through a convergent mechanistic pathway (data not shown). Moreover, extracellular acidosis (pH 7.0) sensitized NECs to Isx-1 mediated Nkx2-5-luc-BAC activation, although, importantly, low pH alone did not transduce sufficient signal to activate the reporter gene in these cells (Fig. 4a). We confirmed GPR68’s role in normal Isx function using small interfering RNAs (siRNA), which knocked-down Gpr68 mRNA levels by ~50% in Nkx2-5-luc-BAC reporter NECs, independent of Isx (Fig. 4b). GPR68 knockdown by siRNA completely abolished the Isx-triggered Ca2+ spike in NECs (Fig. 4c) and, further downstream, strongly attenuated (by almost two thirds) the Isx-1 induced transactivation of the Nkx2-5-luc-BAC in reporter NECs (Fig. 4d). Finally, we studied the effects of Gpr68 on Isx-1 mediated cardiomyogenic differentiation in NECs by evaluating the biosynthesis and assembly of α-actinin pre-sarcomeres (Fig. 4e). Specific downregulation of GPR68 by siRNA dramatically inhibited Isx-1’s cardiomyogenic differentiation activity in NECs Taken together, these data demonstrate that GPR68 is an important mediator of Isx-1 triggered Ca2+ fluxes, downstream transcriptional regulatory circuits and differentiation programs in NECs.

Figure 4. GPR68 is required for Isx’s cardiomyogenic function in NECs.

(a) Activation of Nkx2-5-luc-BAC by Isx-1 in NECs is regulated by pH (maximal activity @ pH~7.0) but low pH/protons alone (Ctrl) does not activate this reporter gene. (b) siRNA-mediated Gpr68 mRNA knockdown by QPCR in NECs. siRNA-mediated Gpr68 mRNA knockdown abolished Isx-1 triggered Ca2+ signaling by Fura-2AM ratiometric tracing (c), attenuated Isx-1 mediated Nkx2-5-luc-BAC reporter gene activation (d), and decreased Isx-1 induced biosynthesis and assembly of α-actinin pre-sarcomeres in NECs shown graphically (left hand graph) and in representative Ctrl or Gpr68 siRNA ACTN2 IHC images (scale bar = 50 µm) (e).

CONCLUSION

Identifying the mechanism-of-action and targets of bioactive synthetic small-molecules is a crucial bottleneck for advancing primary (µM) hits useful as chemical probes towards target-based (nM) leads suitable for drug discovery and development. The unbiased nature of primary hits from cell-based “black box” screens can make traversing this chemical biology bottleneck an “aha” moment of surprise and mechanistic clarity. Here, we probed the mechanism-of-action and protein targets of our Isx small-molecule drivers of cardiomyogenic differentiation in NECs and enhancers of post-MI ventricular function in mice (9). We tested our Isx-GPCR hypothesis in a functional target screen that identified GPR68, a proton sensing GPCR highly regulated in ischemic myocardium. Conceptually, GPR68 provide an ideal (disease-specific) target for future drugs intended to enhance myocardial cell survival and function in the context of ischemic acidosis. GPR68 joins an elite class of myocardial GqPCRs that includes angiotensin-II (AT1R), adrenergic (α-1AR) and endothelin-1 (ET1R) receptors (20). Connecting GPR68 to ischemic heart disease through Isx chemical probes validates chemical biology’s promise to discover new and unexpected disease targets.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

We acknowledge J. Shelton for tissue processing and sectioning, H. May and W. Tan for animal surgeries, M. Cobb, E. Dioum, J. Hill, E. Olson and T. Wilkie for helpful discussions, S. Ludwig for reading the manuscript and O. Witte for the GPR68-EGFP expression plasmid.

SOURCES OF FUNDING

This work was supported by the American Heart Association-Jon Holden DeHaan Cardiac Myogenesis Research Network, NIH/NHLBI U01 Progenitor Cell Biology Consortium (HL100401) and Lone Star Heart Sponsored Research Agreement to JWS and NIH/NHLBI predoctoral NRSA fellowship (#F31HL110598) to HRA.

Footnotes

ASSOCIATED CONTENT

Supporting Information Available: This material is available free of charge via the Internet at http://pubs.acs.org.

REFERENCES

- 1.Burdine L, Kodadek T. Target identification in chemical genetics: the (often) missing link. Chem Biol. 2004;11:593–597. doi: 10.1016/j.chembiol.2004.05.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Laggner C, Kokel D, Setola V, Tolia A, Lin H, Irwin JJ, Keiser MJ, Cheung CY, Minor DL, Jr., Roth BL, Peterson RT, Shoichet BK. Chemical informatics and target identification in a zebrafish phenotypic screen. Nat Chem Biol. 2011;8:144–146. doi: 10.1038/nchembio.732. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Sadek H, Hannack B, Choe E, Wang J, Latif S, Garry MG, Garry DJ, Longgood J, Frantz DE, Olson EN, Hsieh J, Schneider JW. Cardiogenic small molecules that enhance myocardial repair by stem cells. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2008;105:6063–6068. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0711507105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Schneider JW, Gao Z, Li S, Farooqi M, Tang TS, Bezprozvanny I, Frantz DE, Hsieh J. Small-molecule activation of neuronal cell fate. Nature chemical biology. 2008;4:408–410. doi: 10.1038/nchembio.95. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Zhang L, Li P, Hsu T, Aguilar HR, Frantz DE, Schneider JW, Bachoo RM, Hsieh J. Small-molecule blocks malignant astrocyte proliferation and induces neuronal gene expression. Differentiation. 2011;81:233–242. doi: 10.1016/j.diff.2011.02.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Dioum EM, Osborne JK, Goetsch S, Russell J, Schneider JW, Cobb MH. A small molecule differentiation inducer increases insulin production by pancreatic beta cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2011 doi: 10.1073/pnas.1118526109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Russell JL, Goetsch SC, Gaiano NR, Hill JA, Olson EN, Schneider JW. A dynamic notch injury response activates epicardium and contributes to fibrosis repair. Circulation research. 2011;108:51–59. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.110.233262. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Rentschler S, Epstein JA. Kicking the epicardium up a notch. Circ Res. 2011;108:6–8. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.110.237297. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Russell JL, Goetsch SC, Aguilar H, Frantz DE, Schneider JW. Targeting native adult heart progenitors with cardiogenic small-molecules. ACS Chem. Biol. 2012 doi: 10.1021/cb200525q. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ludwig MG, Vanek M, Guerini D, Gasser JA, Jones CE, Junker U, Hofstetter H, Wolf RM, Seuwen K. Proton-sensing G-protein-coupled receptors. Nature. 2003;425:93–98. doi: 10.1038/nature01905. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Radu CG, Nijagal A, McLaughlin J, Wang L, Witte ON. Differential proton sensitivity of related G protein-coupled receptors T cell death-associated gene 8 and G2A expressed in immune cells. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2005;102:1632–1637. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0409415102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Tomura H, Mogi C, Sato K, Okajima F. Proton-sensing and lysolipid-sensitive G-protein-coupled receptors: a novel type of multi-functional receptors. Cell Signal. 2005;17:1466–1476. doi: 10.1016/j.cellsig.2005.06.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Seuwen K, Ludwig MG, Wolf RM. Receptors for protons or lipid messengers or both? J Recept Signal Transduct Res. 2006;26:599–610. doi: 10.1080/10799890600932220. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Poole-Wilson PA. Acidosis and contractility of heart muscle. Ciba Found Symp. 1982;87:58–76. doi: 10.1002/9780470720691.ch4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Klabunde T, Hessler G. Drug design strategies for targeting G-protein-coupled receptors. Chembiochem. 2002;3:928–944. doi: 10.1002/1439-7633(20021004)3:10<928::AID-CBIC928>3.0.CO;2-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Xu Y, Casey G. Identification of human OGR1, a novel G protein-coupled receptor that maps to chromosome 14. Genomics. 1996;35:397–402. doi: 10.1006/geno.1996.0377. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Zhou B, Honor LB, He H, Ma Q, Oh JH, Butterfield C, Lin RZ, Melero-Martin JM, Dolmatova E, Duffy HS, Gise A, Zhou P, Hu YW, Wang G, Zhang B, Wang L, Hall JL, Moses MA, McGowan FX, Pu WT. Adult mouse epicardium modulates myocardial injury by secreting paracrine factors. J Clin Invest. 2011;121:1894–1904. doi: 10.1172/JCI45529. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Russell JL, Goetsch SC, Gaiano NR, Hill JA, Olson EN, Schneider JW. A dynamic notch injury response activates epicardium and contributes to fibrosis repair. Circ Res. 108:51–59. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.110.233262. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hullinger TG, Montgomery RL, Seto AG, Dickinson BA, Semus HM, Lynch JM, Dalby CM, Robinson K, Stack C, Latimer PA, Hare JM, Olson EN, van Rooij E. Inhibition of miR-15 Protects Against Cardiac Ischemic Injury. Circ Res. 110:71–81. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.111.244442. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Salazar NC, Chen J, Rockman HA. Cardiac GPCRs: GPCR signaling in healthy and failing hearts. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2007;1768:1006–1018. doi: 10.1016/j.bbamem.2007.02.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Livak KJ, Schmittgen TD. Analysis of relative gene expression data using real-time quantitative PCR and the 2(-Delta Delta C(T)) Method. Methods. 2001;25:402–408. doi: 10.1006/meth.2001.1262. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Luo X, Shin DM, Wang X, Konieczny SF, Muallem S. Aberrant localization of intracellular organelles, Ca2+ signaling, and exocytosis in Mist1 null mice. The Journal of biological chemistry. 2005;280:12668–12675. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M411973200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.