Abstract

Objective

This study aimed to test whether aortic valve calcium (AVC) is independently associated with coronary and cardiovascular events in a primary-prevention population.

Background

Aortic sclerosis is associated with increased cardiovascular morbidity and mortality among the elderly, but the mechanisms underlying this association remain controversial and it is unknown if this association extends to younger individuals.

Methods

We performed a prospective analysis of 6,685 participants in the Multi-Ethnic Study of Atherosclerosis. All subjects, aged 45-84 years and free of clinical cardiovascular disease at baseline, underwent computed tomography for AVC and coronary artery calcium (CAC) scoring. The primary, pre-specified combined endpoint of cardiovascular events included myocardial infarctions, fatal and non-fatal strokes, resuscitated cardiac arrest and cardiovascular death, while a secondary combined endpoint of coronary events excluded strokes. The association between AVC and clinical events was assessed using Cox proportional hazards regression with incremental adjustments for demographics, cardiovascular risk factors, inflammatory biomarkers and subclinical coronary atherosclerosis.

Results

Over a median follow up of 5.8 [IQR 5.6, 5.9] years, adjusting for demographics and cardiovascular risk factors, subjects with AVC (n=894, 13.4%) had higher risks of cardiovascular (HR, 1.50; 95% CI, 1.10-2.03) and coronary (HR, 1.72; 95% CI, 1.19-2.49) events compared to those without AVC. Adjustments for inflammatory biomarkers did not alter these associations, but adjustment for CAC substantially attenuated both cardiovascular (HR, 1.32; 95% CI: 0.98-1.78) and coronary (HR, 1.41; 95% CI, 0.98-2.02) event risk. AVC remained predictive of cardiovascular mortality even after full adjustment (HR, 2.51; 95% CI, 1.22-5.21).

Conclusions

In this multiethnic MESA cohort, free of clinical cardiovascular disease, AVC predicts cardiovascular and coronary event risk independent of traditional risk factors and inflammatory biomarkers, likely due to the strong correlation between AVC and subclinical atherosclerosis. The association of AVC with excess cardiovascular mortality beyond coronary atherosclerosis risk merits further investigation.

Introduction

Calcific aortic valve disease is common in older adults, with an estimated prevalence of 25% in individuals over 65 years of age.(1) Thought previously to be a degenerative disorder, the disease now is recognized to be an actively-regulated biological process sharing many epidemiologic(1-4) and histopathologic(5) similarities to coronary atherosclerosis.

In older adults without known cardiovascular disease, aortic sclerosis (the presence of valve calcium without hemodynamic obstruction) is associated with a 50% increase in risk for cardiovascular events.(6) Hypothesized mechanisms underlying this association include inflammation, subclinical atherosclerosis, or other shared biological mechanisms.

To determine whether the presence of aortic valve calcium (AVC), detected from computed tomography scans, predicts cardiovascular events in a younger cohort, and to identify mechanisms underlying this association, we performed a prospective analysis in the Multi-Ethnic Study of Atherosclerosis (MESA).

Methods

Study Population

The Multi-Ethnic Study of Atherosclerosis (MESA) is an NHLBI-sponsored, population-based investigation of subclinical cardiovascular disease and its progression.(7) In this study, a total of 6,814 individuals, aged 45 to 84 years, were recruited from six US communities (Baltimore City and County, MD; Chicago, IL; Forsyth County, NC; Los Angeles County, CA; New York, NY; and St. Paul, MN) between July 2000 and August 2002. Pre-specified recruitment plans targeted four ethnic groups (White, Black, Hispanic, and Chinese). Participants were excluded if they had physician-diagnosed cardiovascular disease prior to enrollment, including angina, myocardial infarction (MI), heart failure, stroke or TIA, resuscitated cardiac arrest or a cardiovascular intervention (e.g., CABG, angioplasty, valve replacement, or pacemaker/defibrillator placement). Subjects with subclinical aortic valve disease (e.g., bicuspid valves) were thus eligible for participation. The institutional review boards at each participating institution approved MESA and each individual participant provided informed written consent prior to enrollment.

Demographic and Covariate Data

The comprehensive baseline MESA examination included a clinic visit, serum analyses, and computed tomography (CT) examination of the chest and heart. Information regarding the participants’ demographic data and medical history, including medication use, was obtained by questionnaire. Ethnicity was self-reported. Baseline testing for, and definitions of, cardiovascular risk factors have been described previously.(8) Serum samples were obtained following a 12-hour fast and analyzed in a central laboratory (University of Vermont, Burlington, VT). C-reactive protein (CRP) concentrations were analyzed using the BNII high sensitivity nephelometer (Dad Behring, Inc., Deerfield, IL). Diabetes and impaired fasting glucose were defined according to the 2003 American Diabetes Association fasting criteria algorithm, or a history of diabetes treatment. Renal function was estimated using the Modification of Diet in Renal Disease (MDRD) equation.

Computed Tomography Analysis

All MESA participants underwent baseline CT scans, which were analyzed for both coronary artery calcium (CAC) and AVC. Three institutions used an electron beam tomography (EBT) Imatron C150 scanner (GE Medical Systems, Milwaukee, WI), while 3 institutions used 4-slice multidetector CT (MDCT) scanners. Spatial resolution was 1.38 mm3 for EBT (0.68 × 0.68 × 3.00 mm) and 1.15 mm3 for MDCT (0.68 × 0.68 × 2.50 mm). Full details concerning the equipment, scanning methods, and quality control, including image calibration, phantom adjustment and inter-scanner reproducibility, have been reported previously.(9,10)

All scans were sent to a central MESA CT reading center (Harbor-UCLA Research and Education Institute, Los Angeles, CA). Calcium strongly attenuates x-rays, appears bright on CT scans and is readily differentiated from surrounding tissue. The methods for CAC scoring in MESA have been described previously.(11) Consistent with accepted methodology,(10,12-14) lesions were classified as AVC if they resided within the aortic valve leaflets, exclusive of the aortic annulus or coronary arteries, and contained ≥3 contiguous pixels of ≥130 Hounsfield units brightness. Using Agatston methodology,(15) single lesion calcium content were summed to give a total AVC score. If no lesions reached threshold, the AVC score was zero.

Outcomes Assessment

MESA participants were followed prospectively from time of enrollment. To capture unreported events, telephone interviews were conducted every 9-12 months. Over 99% of self-reported hospitalizations and 97% of cardiovascular outpatient diagnoses and procedures were investigated through medical record review, and incident aortic valve disease and valve replacements were identified by IC9 diagnosis and procedure codes. Death investigations included examination of death certificates and next-of-kin interviews. Each event was adjudicated by two physicians, with committee review of disagreements. Deaths potentially due to cardiovascular causes were adjudicated by full committee.

The combined endpoints of major coronary events (MI, resuscitated cardiac arrest, and cardiovascular death) and major cardiovascular events (coronary events plus non-fatal or fatal stroke) were pre-specified by MESA. Definite or probable MIs were defined by symptoms, ECG findings, and abnormal cardiac biomarker levels (>2 times upper limits of normal). Strokes were defined as neurologic deficits lasting >24 hours, or lesions on brain imaging consistent with a localized ischemic or hemorrhagic event.

Data Analyses

MESA participants were categorized according to the presence (AVC score >0) or absence (AVC score = 0) of AVC on baseline examination. Differences in baseline demographic features were compared using χ2 test of proportions or the t-test comparison of means where appropriate. Event rates were described and displayed using Kaplan-Meier cumulative events methods. The risks associated with the presence of AVC, adjusted for baseline demographic features, were estimated using Cox proportional hazards regression. Schoenfeld residual and log-minus-log survival plots were utilized to confirm the proportional hazards assumptions of these models.

Incremental model building was performed to demonstrate the impact of baseline factors on overall risk. Model 1 included adjustments for age, sex and race. Model 2 additionally adjusted for body size, cardiovascular risk factors and renal function. Model 3 additionally included adjustment for CRP, which was log-transformed prior to inclusion due to its skewed distribution. Exploratory models adding fibrinogen and IL-6 were also performed, but did not substantively alter the results.

Model 4 included adjustment for baseline CAC score, modeled as a log-transformed variable using the sum of the CAC score plus 1 [i.e., Log(CAC+1)] to permit inclusion of subjects with CAC scores of zero. Exploratory analyses using alternative CAC transformations were performed, including Greenland categories (0, 1 to 100, 100 to 300, and >300),(16) and a square root transformation, but these did not substantively alter the analytical results.

All statistical analyses were performed with Stata 11.0 for Windows (Stata Corp, College Station, TX). Statistical significance was defined as p<0.05, and hazard ratios (HRs) are reported with 95% confidence intervals.

Results

Study Subjects

Of the 6,814 participants initially recruited into MESA, 6,685 were included in these analyses. Participants were excluded for cardiovascular events prior to enrollment (n=5, 0.1%), lost to follow-up (33, 0.5%), no baseline AVC scoring (n=1, 0.01%), and missing covariate data (n=90, 1.3%). Two excluded subjects had strokes during follow up, 1 each with and without AVC at baseline.

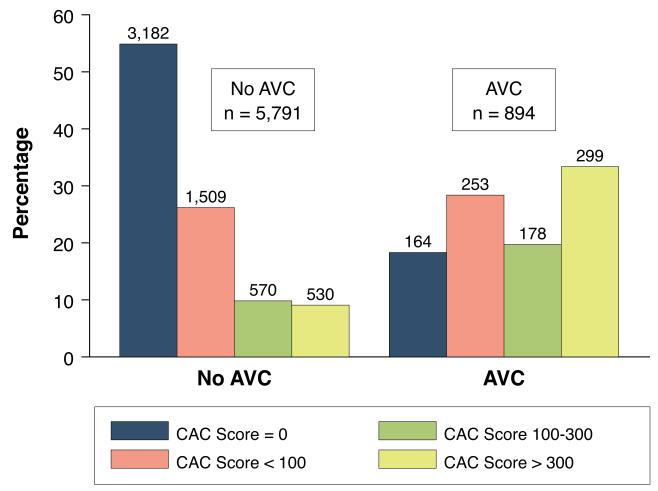

The baseline characteristics of the study cohort are shown in Table 1. AVC was observed in 13% of the cohort at baseline, with a median Agatston score of 58 [IQR: 20, 149]. Subjects with AVC were older, more likely to be male, and had worse overall cardiovascular risk factor profiles. Additionally, subjects with AVC were more likely to have CAC, and to have higher CAC scores (Figure 1).

Table 1.

Baseline Demographics and Risk Factors According to Presence of Aortic Valve Calcium.

| Characteristic | All Subjects (n=6,685) |

No AVC (n=5,791) |

AVC (n=894) |

P Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age, years (sd) | 62 (10) | 61 (10) | 70 (8) | <0.0001 |

| Male sex, n (%) | 3,157 (47) | 2,621 (45) | 536 (60) | <0.0001 |

| Race/Ethnicity, n (%) | <0.0001 | |||

| White | 2,583 (39) | 2,181 (38) | 402 (45) | |

| Chinese | 795 (12) | 729 (13) | 66 (7) | |

| Black | 1,832 (27) | 1,605 (28) | 227 (25) | |

| Hispanic | 1,475 (22) | 1,276 (22) | 199 (22) | |

| Body mass index, kg/m2 (sd) | 28.3 (5.5) | 28.3 (5.5) | 28.5 (5.0) | 0.26 |

| Hypertension, n (%) | 2,997 (45) | 2,421 (42) | 576 (64) | <0.0001 |

| Medical therapy, n (%) | 2,486 (37) | 1,991 (34) | 495 (55) | <0.0001 |

| Blood pressure | ||||

| Systolic, mmHg (sd) | 127 (22) | 125 (21) | 135 (22) | <0.0001 |

| Diastolic, mmHg (sd) | 72 (10) | 72 (10) | 72 (10) | 0.52 |

| Diabetes status, n (%) | <0.0001 | |||

| Normal | 4,922 (74) | 4,350 (75) | 572 (64) | |

| Impaired fasting glucose | 924 (14) | 783 (14) | 141 (16) | |

| Diabetes | 839 (13) | 648 (11) | 181 (20) | |

| Smoking status, n (%) | <0.0001 | |||

| Never | 3,362 (50) | 2,972 (51) | 390 (44) | |

| Former | 2,455 (37) | 2,044 (35) | 411 (46) | |

| Current | 868 (13) | 775 (13) | 93 (10) | |

| Pack-years smoking† | 16 [6, 32] | 15 [6, 31] | 20 [7, 44] | <0.0001 |

| Family history of MI, n (%) | 2,680 (40) | 2,277 (39) | 403 (45) | <0.0001 |

| Cholesterol, mg/dl (sd) | ||||

| Total | 194 (36) | 194 (35) | 195 (38) | 0.37 |

| Low density | 117 (31) | 117 (31) | 119 (35) | 0.11 |

| High density | 51 (15) | 51 (15) | 49 (14) | <0.0001 |

| Triglycerides* | 111 [78, 161] | 110 [77, 159] | 120 [83, 172] | 0.0006 |

| Cholesterol: HDL Ratio | 4.1 (1.2) | 4.0 (1.2) | 4.2 (1.2) | <0.0001 |

| Lipid lowering meds, n (%) | 1,088 (16) | 856 (15) | 232 (26) | <0.0001 |

| C-reactive protein, mg/dL* | 1.91 [0.84, 4.24] | 1.89 [0.82, 4.26] | 2.05 [0.95, 4.09] | 0.04 |

| Estimated GFR, ml/min | 81 (18) | 82 (18) | 76 (19) | <0.0001 |

| Coronary artery calcium, n (%) | 3,339 (50) | 2,609 (45) | 730 (82) | <0.0001 |

Abbreviations: AVC, aortic valve calcium; HDL, high density lipoprotein; GFR, glomerular filtration rate

SI conversion factors: to convert cholesterol concentrations to mmol/L, multiply by 0.0259; to convert triglyceride concentrations to millimoles/liter, multiply by 0.01129; to convert creatinine to micromoles per liter, multiply by 88.4.

Median [IQR]

Median [IQR] among current and former smokers

Figure 1. Distribution of Coronary Artery Calcium Scores, Stratified by Presence of Aortic Valve Calcium.

The prevalence of coronary artery calcium (CAC) categories (CAC score = 0; <100; 100-300; and >300) among MESA participants with (n=894) and without (n=5791) aortic valve calcium (AVC) at baseline. Participants with baseline AVC had a higher prevalence of CAC (87.1% vs. 45.1%, p<0.0001) compared to those without AVC, with skewing of the distribution of CAC scores towards more severe calcification.

Subjects were followed for a median of 5.8 [IQR: 5.6, 5.9] years, with maximal follow up of 7.1 years. During this period, there were 40 cases of incident aortic valve disease and 22 aortic valve replacements, as well as 160 coronary and 255 cardiovascular events.

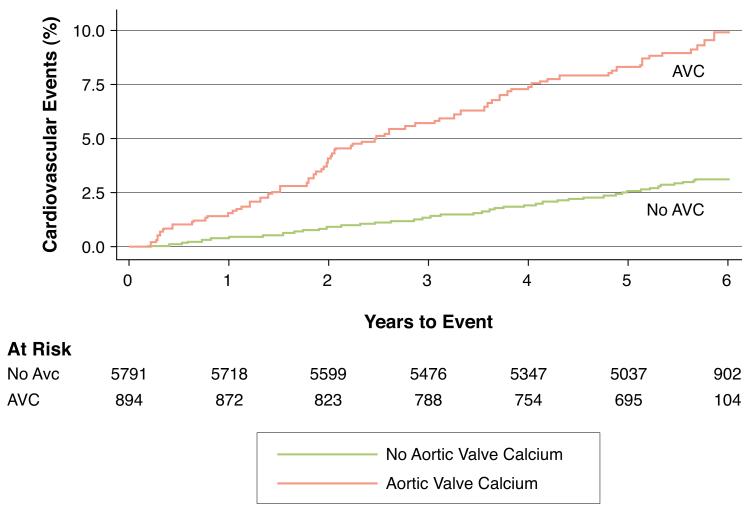

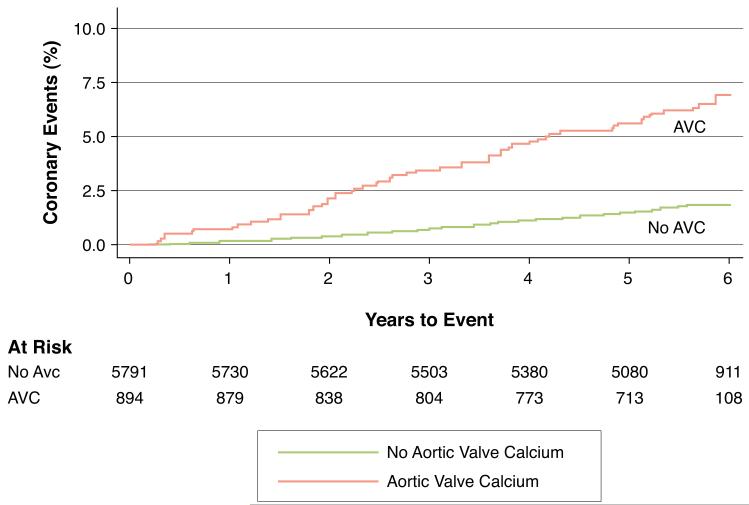

Risk of Coronary and Cardiovascular Events

Figure 2 depicts the unadjusted Kaplan-Meier cumulative event curves for major coronary and cardiovascular events, respectively. After adjusting for age, race and gender (Table 2, Model 1), the presence of AVC was a strong predictor of both cardiovascular and coronary events. Although these risks were attenuated after adjusting for known atherosclerotic risk factors (Table 2, Model 2), AVC remained predictive of both cardiovascular (HR, 1.50; 95% CI, 1.10-2.04) and coronary (HR, 1.72; 95% CI, 1.19-2.49) events.

Figure 2. Kaplan-Meier Event Curves for Primary and Secondary Outcomes.

Unadjusted Kaplan-Meier cumulative event curves depicting the Cardiovascular (Figure 2A) and Coronary (Figure 2B) events rates among participants with (red curve) and without (blue curve) aortic valve calcium (AVC) at baseline. At the median 5.8 years of follow up, participants with AVC had higher unadjusted rates of both Cardiovascular (3.2% vs. 10.2%, p<0.0001) and Coronary (1.9% vs. 6.9%, p<0.0001) events compared to participants without AVC.

Table 2.

Incrementally adjusted risks of cardiovascular events associated with the presence of aortic valve calcification.

| Major Cardiovascular Event (n=255) | Major Coronary Event (n=160) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Hazard Ratio (95% CI) | P Value | Hazard Ratio (95% CI) | P Value | |

| Model 1 | 1.82 (1.37, 2.42) | <0.001 | 2.07 (1.45, 2.95) | <0.001 |

| Model 2 | 1.50 (1.10, 2.04) | 0.009 | 1.72 (1.19, 2.49) | 0.004 |

| Model 3 | 1.50 (1.10, 2.03) | 0.01 | 1.72 (1.19, 2.49) | 0.004 |

| Model 4 | 1.32 (0.98, 1.78) | 0.07 | 1.41 (0.98-2.02) | 0.07 |

Model 1: included adjustments for age, gender and race.

Model 2: included all variables in Model 1 plus adjustments for BMI, systolic and diastolic blood pressure, diabetes status, use of antihypertensive therapy, smoking status, family history of heart attack, total cholesterol, HDL cholesterol, triglycerides, use of cholesterol lowering medications, and renal function.

Model 3: included all variables in Model 2 plus adjustment for Log(C-reactive protein).

Model 4: included all variables in Model 3 plus adjustment for Log(CAC score +1).

The inclusion of CRP in the model (Table 2, Model 3) did not alter these findings. However, in the fully adjusted model that included adjustments for both CRP and CAC scores (Table 2, Model 4), AVC demonstrated a borderline association with cardiovascular (HR, 1.32; 95% CI, 0.98-1.78) and coronary (HR, 1.41; 95% CI, 0.98-2.02) events. Additionally, there was no significant trend in risk across AVC tertiles for either outcome (HR 1.17, p=0.32 and HR=1.09, p=0.66, respectively).

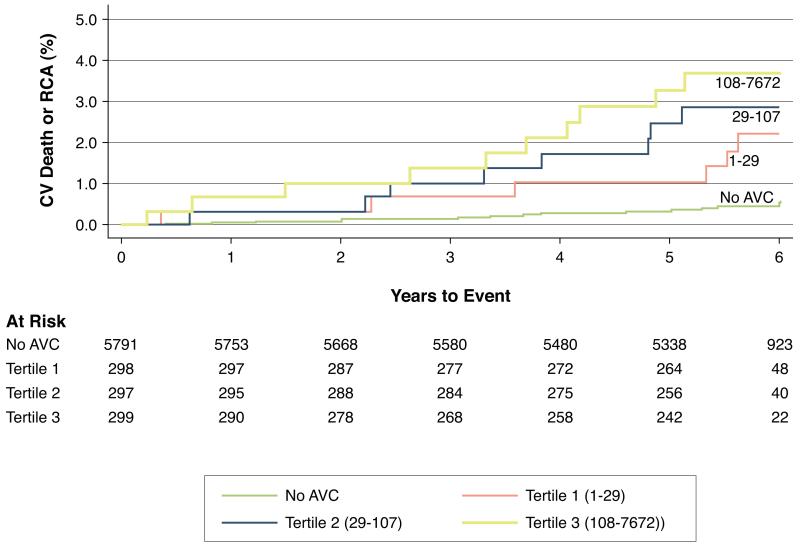

Risk by Event Type

In fully-adjusted models incorporating demographics, cardiovascular risk factors, inflammatory biomarkers and CAC scores, the presence of AVC was not associated with increased risks for MI or stroke (Table 3), but was associated with a 2.76 (95% CI, 1.44-5.30)-fold higher risk for cardiovascular death or resuscitated cardiac arrest. These results were unaltered (HR, 2.72; 95% CI: 1.37-5.40, P=0.004) when subjects with clinical progression (incident clinical valve disease or valve replacement, n=54) or higher baseline calcium (AVC score >100, n=293) were excluded. Increasing tertiles of AVC were observed to have increased event rates (Figure 3). Compared to those without AVC, those with AVC scores 1.9-29.2, 29.4-107, and 107.5-7,672 had a 2.18 (95% CI, 0.93-5.12), 3.10 (95% CI, 1.31-7.37) and 3.02 (95% CI, 1.22-7.43)-fold higher risk of cardiovascular death, respectively, after full adjustment.

Table 3.

Number of Pre-Specified Events by Event Type, Stratified by Presence or Absence of Aortic Valve Calcium at Baseline.

| Event | Total (n=6,685) |

No AVC (n=5,791) |

AVC (n=894) |

Hazard Ratio (95% CI) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age, Race, Gender |

Fully Adjusted† | ||||||

| Cardiovascular Events | Coronary Events | Myocardial Infarction, n (%) | 126 (1.9) | 87 (1.5) | 39 (4.3) | 1.67 (1.11, 2.52) | 1.11 (0.73, 1.68) |

| Resuscitated cardiac arrest, n (%) | 17 (0.3) | 8 (0.1) | 9 (1.0) | 5.94 (2.05, 17.2) | 5.37 (1.43, 20.1) | ||

| Cardiovascular death*, n (%) | 36 (0.5) | 18 (0.3) | 18 (2.2) | 3.66 (1.79, 7.48) | 2.51 (1.22, 5.21) | ||

| Any Stroke, n (%) | 103 (1.5) | 71 (1.2) | 32 (3.6) | 1.75 (1.11, 2.74) | 1.38 (0.84, 2.27) | ||

| Fatal stroke, n (%) | 13 (0.2) | 10 (0.2) | 3 (0.4) | 0.74 (0.19, 2.82) | 0.59 (0.14, 2.51) | ||

Abbreviations: AVC, Aortic Valve Calcium

Events may not sum due to synchronous events (e.g., myocardial infarction resulting in cardiovascular death would be classified as a single coronary event).

Cardiovascular deaths excluding strokes.

Hazard ratios are adjusted for age, race, gender, body mass index, systolic and diastolic blood pressure, use of antihypertensive medication, diabetes status, smoking status, pack years smoked, total cholesterol, HDL cholesterol, triglycerides, use of lipid lowering medications, renal function, C-reactive protein and log of coronary calcium scores.

Figure 3. Kaplan Meier Event Curves for Cardiovascular Mortality.

Unadjusted Kaplan-Meier cumulative event curves for the combined endpoint of cardiovascular (CV) death or resuscitated cardiac arrest (RCA), stratified by tertiles of baseline aortic valve calcium (AVC) score. At the median 5.8 years of follow up, the unadjusted event rate for participants without baseline AVC was 0.5%, compared with event rates of 2.1% (tertile 1), 3.2% (tertile 2), and 3.7% (tertile 3) for those with increasing severity of baseline AVC. After full adjustment for age, sex, cardiovascular risk factors, renal function and coronary artery calcium scores, there remained a 1.48-fold (95% CI: 1.14, 1.95; p=0.004) increase in risk of CV death or RCA per tertile-increase in AVC score.

Risk by Race/Ethnicity

After adjustment for demographics, cardiovascular risk factors, inflammation and CAC score, there were no significant differences by race/ethnicity in the association of AVC with either cardiovascular (P-interaction=0.12) or coronary (P-interaction=0.13) events.

Discussion

Calcific aortic valve disease begins in midlife as a clinically latent but progressive disorder, and often is detected incidentally. Yet even in this latent, pre-obstructive phase, the presence of aortic valve calcium appears to be a marker of increased cardiovascular risk. Prior results from the Cardiovascular Health Study (CHS) showed that, among adults >65 years, echocardiographically-detected aortic sclerosis was associated with a 50% increased risk of cardiovascular mortality.(6) In that study, aortic sclerosis also was associated with a 42% increase in risk of MI. However, these analyses were unable to control for the presence of subclinical atherosclerosis and systemic inflammation, plausible mediators of these associations.

Our results extend these prior findings to a younger, healthier and multiethnic population, and offer a partial explanation for the observed association between aortic sclerosis and coronary events. Among participants aged 45-84 years and free of cardiovascular disease at baseline, and after adjustment for demographics and cardiovascular risk profiles, the presence of AVC on CT scan was associated with significant 50% higher risk of cardiovascular events and a 72% higher risk of coronary events. Notably, these results are similar in magnitude to echocardiographically detected aortic sclerosis in CHS. These risk estimates were unaltered by adjustment for inflammatory biomarkers, suggesting that systemic inflammation did not account for these associations.

Conversely, the risk estimates were attenuated substantially after adjusting for the severity of subclinical atherosclerosis, as estimated by CAC scores. CAC has been strongly and independently associated with cardiovascular events across a range of age, ethnic and risk profiles.(8,16-18) We found a strong association between presence of AVC and both the prevalence and severity of CAC in MESA (Figure 1), and after adjusting for CAC, the observed risk of MI approached unity. These findings suggests that CAC scores are an effective marker of coronary event risk and that a substantial portion of the increased risk of cardiovascular morbidity seen with AVC is due to coexistent subclinical atherosclerosis.

To test whether AVC was associated with clinical events, we performed extensive adjustments beyond the standard Framingham risk factors, including adjustments for body mass index, diabetes, impaired fasting glucose, pack years smoking, family history of MI, use of lipid lowering therapy, and renal function. Thus our findings do not preclude the possibility that AVC adds to Framingham risk prediction. Among 5,877 non-diabetics in MESA, AVC remained strongly associated with coronary events after adjustment for Framingham risk factors alone (HR, 1.85; 95% CI 1.33-2.59) and Framingham risk factors plus CAC (HR, 1.42; 95% CI, 1.02-1.98). Whether AVC improves risk categorization beyond Framingham risk calculations requires more detailed analyses beyond the scope of the present investigation.

In pre-specified exploratory analyses, AVC remained an independent predictor of cardiovascular mortality after adjustment for risk factors and CAC severity. Given the low event rate, this finding must be interpreted with caution. Nonetheless, this finding is intriguing, as this excess mortality may be unrelated to progressive valve disease. Participants with substantial calcium progression likely would have developed symptoms and undergone valve replacement, whereas death from asymptomatic aortic stenosis is relatively uncommon,(19) even in very severe aortic stenosis.(20) Prior studies have suggested aortic stenosis is uncommon with AVC scores <150,(13,14) and exclusion of those with known progression and those with AVC scores >100 did not alter the risk association. The mechanisms underlying this observed association remain unexplained, and further investigations are warranted.

Study Limitations

This study has several limitations. First, AVC was not a pre-specified variable within MESA and CT scans obtained for the purpose of CAC scoring were analyzed retrospectively. Second, only baseline risk factor profiles were included as covariates, and change in profiles were not evaluated. Third, the rate of cardiovascular events in MESA was low, reducing the power to detect risk associations. Finally, participants and their physicians were informed of high CAC scores, knowledge that may have prompted therapy to reduce cardiovascular risk; however, such treatment would likely bias results towards the null.

Conclusion

In a multiethnic cohort without clinical cardiovascular disease at baseline, AVC was associated with risks for coronary and cardiovascular events beyond those predicted by traditional risk factors. These risk-associations were attenuated after adjustment for CAC but not for inflammatory markers, suggesting that AVC partly serves as a marker of subclinical atherosclerosis severity. Whether AVC adds to cardiovascular risk prediction beyond Framingham risk categorization merits additional investigation. Finally, through mechanisms yet to be elucidated, the association of AVC with excess cardiovascular mortality remained, even after adjustment for risk factors, inflammation and subclinical atherosclerosis.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank the other investigators, staff, and participants of the MESA study for their valuable contributions. A full list of participating MESA investigators and institutions can be found at http://www.mesa-nhlbi.org.

Funding/Support: This research was supported by R01-HL-63963-01A1, and by contracts N01-HC-95159 through N01-HC-95165 and N01-HC-95169 from the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute.

Role of the Sponsor: The NHLBI participated in the design and conduct of the MESA study, but did not take part in manuscript preparation or the decision to submit for publication. The NHLBI did not review this manuscript prior to submission.

Abbreviation List

- AVC

aortic valve 3calcium

- CAC

coronary artery calcium

- CHS

Cardiovascular Health Study

- CRP

C-reactive protein

- CT

computed tomography

- EBT

electron beam tomography

- MDCT

multidetector computed tomography

- MESA

Multi-Ethnic Study of Atherosclerosis

- MI

myocardial Infarction

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Financial Disclosures: Dr. Budoff has received speaking honoraria from General Electric. Dr. O’Brien has received speaking honoraria from AstraZeneca and Merck.

Clinical Trial Registration: ClinicalTrials.gov Registry Unique Identifier: NCT00005487; URL: http://www.clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/NCT00005487

Trial Name: Multi-Ethnic Study of Atherosclerosis (MESA)

References

- 1.Stewart BF, Siscovick D, Lind BK, et al. Clinical factors associated with calcific aortic valve disease. Cardiovascular Health Study. J Am Coll Cardiol. 1997;29:630–4. doi: 10.1016/s0735-1097(96)00563-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Agmon Y, Khandheria BK, Meissner I, et al. Aortic valve sclerosis and aortic atherosclerosis: different manifestations of the same disease? Insights from a population-based study. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2001;38:827–34. doi: 10.1016/s0735-1097(01)01422-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Lindroos M, Kupari M, Valvanne J, Strandberg T, Heikkila J, Tilvis R. Factors associated with calcific aortic valve degeneration in the elderly. Eur Heart J. 1994;15:865–70. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.eurheartj.a060602. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Owens DS, Katz R, Takasu J, Kronmal R, Budoff MJ, O’Brien KD. Incidence and progression of aortic valve calcium in the Multi-ethnic Study of Atherosclerosis (MESA) Am J Cardiol. 2010;105:701–8. doi: 10.1016/j.amjcard.2009.10.071. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.O’Brien KD. Pathogenesis of Calcific Aortic Valve Disease. A Disease Process Comes of Age (and a Good Deal More) Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2006 doi: 10.1161/01.ATV.0000227513.13697.ac. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Otto CM, Lind BK, Kitzman DW, Gersh BJ, Siscovick DS. Association of aortic-valve sclerosis with cardiovascular mortality and morbidity in the elderly. N Engl J Med. 1999;341:142–7. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199907153410302. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bild DE, Bluemke DA, Burke GL, et al. Multi-ethnic study of atherosclerosis: objectives and design. Am J Epidemiol. 2002;156:871–81. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwf113. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Detrano R, Guerci AD, Carr JJ, et al. Coronary calcium as a predictor of coronary events in four racial or ethnic groups. N Engl J Med. 2008;358:1336–45. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa072100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Budoff MJ, Katz R, Wong ND, et al. Effect of scanner type on the reproducibility of extracoronary measures of calcification: the multi-ethnic study of atherosclerosis. Acad Radiol. 2007;14:1043–9. doi: 10.1016/j.acra.2007.05.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Budoff MJ, Takasu J, Katz R, et al. Reproducibility of CT measurements of aortic valve calcification, mitral annulus calcification, and aortic wall calcification in the multi-ethnic study of atherosclerosis. Acad Radiol. 2006;13:166–72. doi: 10.1016/j.acra.2005.09.090. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Carr JJ, Nelson JC, Wong ND, et al. Calcified coronary artery plaque measurement with cardiac CT in population-based studies: standardized protocol of Multi-Ethnic Study of Atherosclerosis (MESA) and Coronary Artery Risk Development in Young Adults (CARDIA) study. Radiology. 2005;234:35–43. doi: 10.1148/radiol.2341040439. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Budoff MJ, Mao S, Takasu J, Shavelle DM, Zhao XQ, O’Brien KD. Reproducibility of electron-beam CT measures of aortic valve calcification. Acad Radiol. 2002;9:1122–7. doi: 10.1016/s1076-6332(03)80513-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Shavelle DM, Budoff MJ, Buljubasic N, et al. Usefulness of aortic valve calcium scores by electron beam computed tomography as a marker for aortic stenosis. Am J Cardiol. 2003;92:349–53. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9149(03)00646-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Messika-Zeitoun D, Aubry MC, Detaint D, et al. Evaluation and clinical implications of aortic valve calcification measured by electron-beam computed tomography. Circulation. 2004;110:356–62. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.0000135469.82545.D0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Agatston AS, Janowitz WR, Hildner FJ, Zusmer NR, Viamonte M, Jr., Detrano R. Quantification of coronary artery calcium using ultrafast computed tomography. J Am Coll Cardiol. 1990;15:827–32. doi: 10.1016/0735-1097(90)90282-t. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Greenland P, LaBree L, Azen SP, Doherty TM, Detrano RC. Coronary artery calcium score combined with Framingham score for risk prediction in asymptomatic individuals. Jama. 2004;291:210–5. doi: 10.1001/jama.291.2.210. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Raggi P, Gongora MC, Gopal A, Callister TQ, Budoff M, Shaw LJ. Coronary artery calcium to predict all-cause mortality in elderly men and women. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2008;52:17–23. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2008.04.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Nasir K, Shaw LJ, Liu ST, et al. Ethnic differences in the prognostic value of coronary artery calcification for all-cause mortality. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2007;50:953–60. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2007.03.066. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Rosenhek R, Binder T, Porenta G, et al. Predictors of outcome in severe, asymptomatic aortic stenosis. N Engl J Med. 2000;343:611–7. doi: 10.1056/NEJM200008313430903. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Rosenhek R, Zilberszac R, Schemper M, et al. Natural history of very severe aortic stenosis. Circulation. 2010;121:151–6. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.109.894170. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]