Abstract

Recently, we identified a population of Oct4+Sca-1+Lin-CD45- very small embryonic-like stem cells (VSELs) in murine and human adult tissues. VSELs can differentiate in vitro into cells from all 3 germ layers and in vivo tissue-committed stem cells. Open chromatin structure of core pluripotency transcription factors (TFs) supports the pluripotent state of VSELs. However, it has been difficult to determine how primitive VSELs maintain pluripotency, owing to their limited number in adult tissues. Here, we demonstrate by genome-wide gene-expression analysis with a small number of highly purified murine bone marrow–derived VSELs that Oct4+ VSELs (i) express a similar, yet nonidentical, transcriptome as embryonic stem cells (ESCs), (ii) highly express cell cycle checkpoint genes, (iii) express at a low level genes involved in protein turnover and mitogenic pathways, and (iv) highly express enhancer of zeste drosophila homolog 2 (Ezh2), a polycomb group protein. Furthermore, as a result of high expression of Ezh2, VSELs, like ESCs, exhibit bivalently modified nucleosomes (trimethylated H3K27 and H3K4) at promoters of important homeodomain-containing developmental TFs, thus preventing premature activation of the lineage-committing factors. Notably, spontaneous or RNA interference-enforced downregulation of Ezh2 during VSEL differentiation removes the bivalent domain (BD) structure, which leads to de-repression of several BD-regulated genes. Therefore, we suggest that Oct4+ VSELs, like other pluripotent stem cells, maintain their pluripotent state through an Ezh2-dependent BD-mediated epigenetic mechanism. Furthermore, our global survey of VSEL gene expression signature would not only advance our understanding of biological process for their pluripotency, differentiation, and quiescence but should also help to develop better protocols for ex vivo expansion of VSELs.

Introduction

Pluripotent stem cells (PSCs), as demonstrated for embryonic stem cells (ESCs) [1], epiblast stem cells [2,3], embryonic germ cells [4], and induced PSCs [5], differentiate in vitro and in vivo into cells from all 3 germ layers. PSCs commonly express pluripotent core transcription factors (TFs; i.e., Oct4, Nanog, and Sox2) that are involved in maintaining their pluripotent state [6]. PSC pluripotency is also critically dependent on several signaling pathways such as LIF/Stat3, PI3K, Wnt, and BMP pathways [7]. In addition, a defined epigenetic signature could contribute to PSC identity [8]. Accordingly, the promoter regions of homeodomain-containing developmental master TFs, such as Dlx, Irx, Lhx, Pou, Pax, and six family proteins, are physically co-occupied in pluripotent ESCs by both transcriptionally active histones [trimethylated lysine4 of histone3 (H3K4me3)] and repressive ones [trimethylated lysine27 of histone3 (H3K27me3)] [9–13]. The promoters marked by these types of epigenetic modifications are called bivalent domains (BDs) and, due to the overwhelmingly repressive activity of H3K27me3, they show little transcription activity. This prevents the premature expression of cell fate–determining factors. However, in response to differentiation cues, BDs become monovalent, which leads to activation of the TFs responsible for lineage commitment. Therefore, the BDs are essential not only to keep ESCs undifferentiated but also to enable them to respond dynamically to developmental stimuli.

To maintain BDs, the undifferentiated ESCs highly express polycomb group (PcG) and Trithorax group (TrxG) proteins, which are responsible for modification of transcription-repressive H3K27me3 and transcription-promoting H3K4me3 histones, respectively [14]. The essential role of the PcG proteins in the stability of BDs was confirmed by gene-targeting and RNA interference (RNAi) studies [10,11].

PcG proteins repress transcription by involving 2 distinct repressive complexes: polycomb repressive complex 1 (PRC1) and PRC2 [15]. PRC1 consists of core members—chromobox homologue (Cbx), polyhomeotic-like (Phc), Bmi1, Mel18, Ring1A, and Ring1B, which are homologous to the Drosophila melanogaster polycomb, polyhomeotic, Posterior sex combs, and RING. PRC1 is responsible for monoubiquitination of lysine119 of H2AK and chromatin condensation. In contrast, PRC2, which consists of core members such as embryonic ectoderm development (Eed), suppressor of zeste 12 (Suz12), and enhancer of zeste drosophila homolog 2 (Ezh2), exhibits histone methyltransferase (HMTase) activity for H3K27. As previously demonstrated, the PRC-mediated repressive chromatin state is reversed by TrxG proteins [14]. The epigenetic histone code and marks generated by PcG and TrxG proteins are stably inherited during cell proliferation and are considered to be a major mechanism of “cellular memory.” Thus, the balance between PcG and TrxG protein activity establishes transcriptional memory that decides cell fate.

Recently, a population of very small embryonic-like stem cells (VSELs) was identified in murine adult tissues, including bone marrow (BM), fetal liver, testes, ovaries, and human umbilical cord blood [16–20]. VSELs are smaller than erythrocytes and express several markers of (i) pluripotency (Oct4, Nanog, Sox2, and SSEA-1), (ii) epiblast (Gbx2, Fgf5, and Nodal), and (iii) epiblast-derived migratory primordial germ cell (PGC) (Stella, Blimp1, and Prdm14) [21]. The true expression of Oct4, Nanog, and Stella in murine BM-derived VSELs was confirmed by demonstrating the demethylated state of the DNA and enrichment for transcriptionally active histone codes in the promoters of these genes. Furthermore, epigenetic changes in expression of some imprinted genes that are paternally (Igf2-H19 and RasGRF1) and maternally methylated/imprinted (Igf2R and KCNQ1) maintain the quiescence of VSELs [22]. VSELs can differentiate into cells from all 3 germ layers in vitro culture condition [16]. Employing several in vivo tissue regeneration animal models, we have proved that VSELs can be specified in vivo into mesenchymal stem cells [23], cardiomyocyte [24,25], and long-term engrafting hematopoietic stem cells (HSCs) [26,27]. However, the precise molecular mechanism of how primitive VSELs control their pluripotency and differentiation potential remains to be determined.

In this article, to better characterize the murine VSELs, we employed global transcriptome analysis with cDNA libraries derived from 20 highly purified cells. We report that VSELs highly express E2F pathway, as well as some PcG and TrxG proteins, but express at a low level several genes involved in protein turnover and growth factor or mitogen stimulation. Furthermore, we found that VSELs highly express a PRC2 complex member, Ezh2, which is indispensible for maintaining BD structure. We propose that an Ezh2-dependent BD mechanism, similar to that in ESCs, contributes to VSEL pluripotent state.

Materials and Methods

Isolation of VSELs from murine BM and VSEL-DS formation

The current study was performed in accordance with the guidelines of the Animal Care and Use Committee of the University of Louisville, School of Medicine, and with the Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals (Department of Health and Human Services, Publication No. NIH 86–23). The BM tissue was prepared from pathogen-free, 4- to 5-week-old female and male C57BL/6 or C57BL/6-Tg(ACTB-EGFP)1Osb/J mice (Jackson Laboratory). The preparation of MNCs from murine BM, the isolation of VSELs (Sca-1+Lin−CD45−) and HSCs (Sca-1+Lin−CD45+) by multiparameter live-cell sorting (MoFlo, Dako), and the formation of VSEL-derived spheres (VSEL-DSs) cultured over a C2C12 murine myoblast feeder layer were performed as previously described [16].

Cell culture

Murine ESC-D3 cells (ATCC) were grown in a 0.1% gelatin-coated dish, as described in Supplementary Materials and Methods (Supplementary Data are available online at www.liebertonline.com/scd).

Reverse transcriptase and real-time quantitative PCR

Total RNA from fluorescence-activated cell sorting (FACS)-sorted (∼20,000 cells) or cultured cells was isolated using the RNeasy Mini Kit (Qiagen, Inc.) with removal of genomic DNA using the DNA-free™ Kit (Applied Biosystems). cDNA was prepared with Taqman Reverse Transcription Reagents (Applied Biosystems), according to the manufacturer's instructions. Real-time quantitative PCR (RQ-PCR) was performed as previously described [21]. All primer sequences used in RQ-PCR are available upon request.

Single-cell gene expression profiling

Single-cell cDNA library synthesis was performed with a slight modification of previously described protocol [28]. FACS-sorted Sca-1+Lin−CD45− VSELs, Sca-1+Lin−CD45+ HSCs, or trypsinized ESC-D3 cells were distributed into each well of a 384-well plate (Thermo Scientific) containing 4.5 μL of lysis buffer per well using a MoFlo cell sorter. Detailed procedures for synthesizing the T7-primed single-cell cDNA libraries from FACS-sorted cells are described in Supplementary Materials and Methods. For initial screening of the quality of the cDNA libraries derived from 20 purified cells, PCR products were diluted 20-fold and examined for the expression of the indicated genes by employing RQ-PCR. All primers were designed to recognize the 3′ region within 400 bp from mRNA terminal to cover most synthesized single-cell cDNA library products [28]. All primers were designed with Primer Express software (Applied Biosystems) and they were available upon request. The gel-eluted T7-primed libraries were biotin labeled using the GeneChip® 3′ in vitro transcription kit (Affymetrix), starting from “In vitro Transcription to Synthesize Labeled aRNA.”

Microarray hybridization and data processing

The biotin-labeled aRNA was fragmented and hybridized to the GeneChip® 3′ Mouse Genome 430 2.0 array (Affymetrix), according to the manufacturer's instructions. The microarray image data were processed with the GeneChip Scanner 3000 7G (Affymetrix) using the GeneChip Command Console 1.0 (Affymetrix). The CEL files for 9 cell samples (3 VSELs, 3 HSCs, and 3 ESC-D3) were imported into Partek software Version 6.5 (Partek, Inc.) and normalized using Robust Multi-Array normalization. A one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) was set up for the different cell types with contrasts comparing VSELs versus HSCs, ESCs versus HSCs, and VSELs versus ESCs.

Accession numbers

The microarray datasets discussed in current study have been deposited in NCBI's Gene Expression Omnibus (GEO; www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/geo) and are accessible through GEO Series accession number GSE29281.

Analysis of gene expression profiles

Detailed procedures for principal component analysis (PCA) plot, scatter-plot, and heatmap with hierarchical clustering of the microarray data from VSELs, HSCs, and ESC-D3 cells were described in Supplementary Materials and Methods. Functional analysis of the transcriptomes of indicated stem cells was performed using Ingenuity Pathway Analysis (IPA) software version 8.7 (Ingenuity Systems, Inc.) by core and comparison analysis for gene networks, biofunctions, and canonical pathways. Detailed settings for each stem cell population in comparison with the global transcriptome (Fig. 1) and unique VSEL candidates (Fig. 2) are described in Supplementary Materials and Methods.

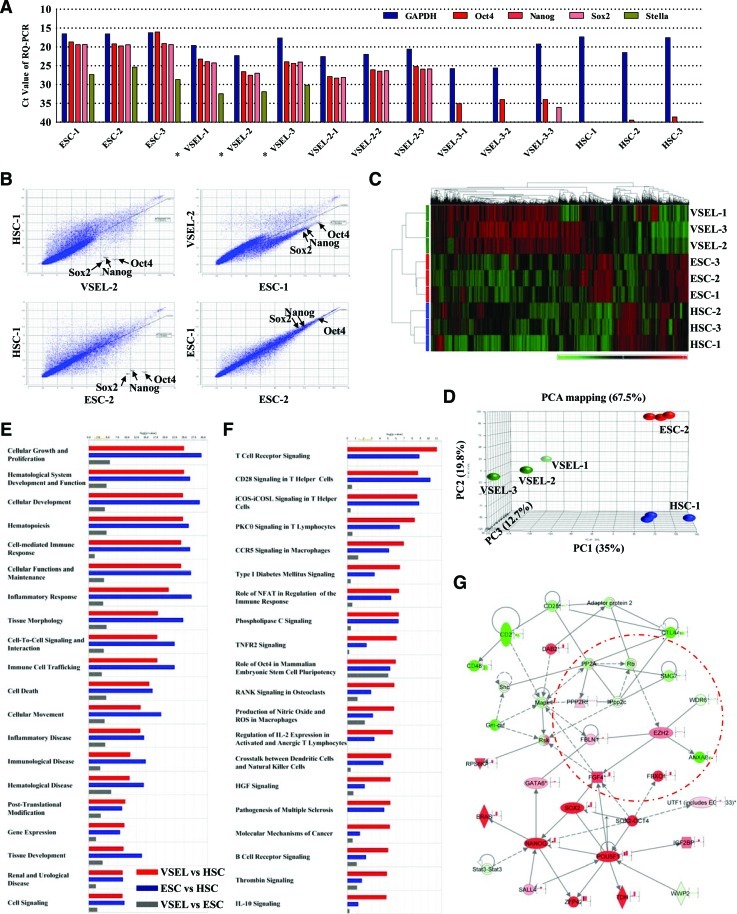

FIG. 1.

Global transcriptome analysis from 20 purified VSELs. (A) Ct value from RQ-PCR analysis (in triplicate) for stemness genes using the indicated cDNA libraries from 20 purified cells: ESC-1∼3 (ESC-D3), VSEL-1∼3, VSEL-2-1∼3, VSEL-3-1∼3 (3 different groups of VSELs), and HSC-1∼3 (HSCs). Asterisk (*) indicates VSEL libraries that were employed for microarray assays. Scatter plot (B), heatmap with hierarchical clustering (C), and PCA mapping (D) of microarray results. The points corresponding to Oct4, Nanog, and Sox2 are indicated in the scatter plot. The top 20 lists for biofunctions (E) and canonical pathways (F) that are most highly represented in VSEL microarray chip versus HSC (red), ESC versus HSC (blue), and VSEL versus ESC (gray) IPA comparisons. The graphs are ordered by the experimental P value in the VSEL versus HSC comparison and the yellow line indicates the threshold (0.05). (G) Gene pluripotency network with overlay of all experimental values for the VSEL versus HSC comparison dataset. Bar graphs next to genes indicate the fold change for each comparison (for VSEL vs. HSC, ESC vs. HSC, and VSEL vs. ESC). The Ppp2r5b-Pp2a-Rb-Ezh2 pathway is represented in the Oct4-Sox2–containing cellular/embryonic development network (red circle). High and low expressions in heatmap and gene network analysis are indicated by red and green, respectively. RQ-PCR, real-time quantitative PCR; VSELs, very small embryonic-like stem cells; ESC, embryonic stem cell; HSCs, hematopoietic stem cells; Ezh2, enhancer of zeste drosophila homolog 2; PCA, principal component analysis; IPA, ingenuity pathway analysis. Color images available online at www.liebertonline.com/scd

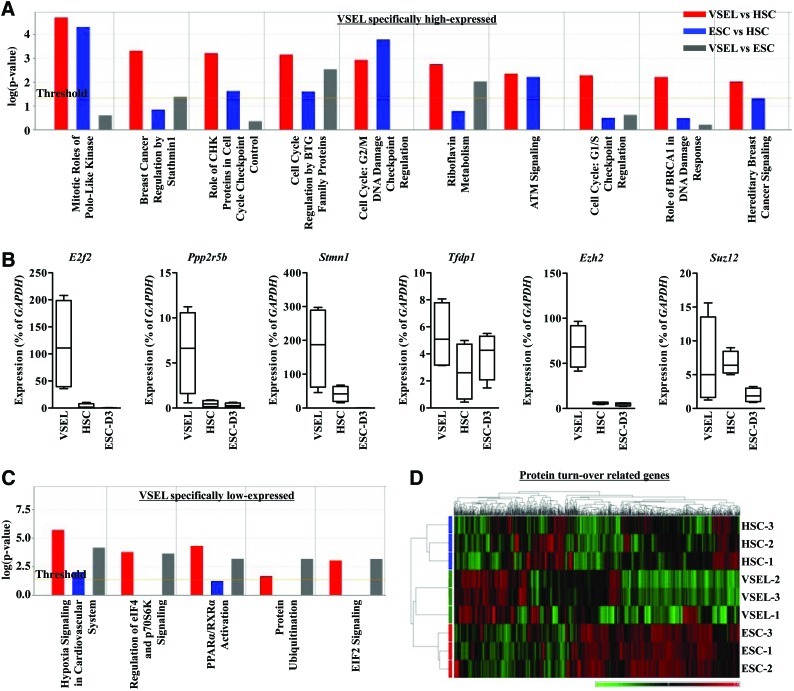

FIG. 2.

VSEL-specific gene expression profiles. (A) Top 10 canonical pathways that are most highly represented in IPA analysis for genes specifically expressed at a high level in VSELs. Graph bars are ordered by the experimental P value in the VSEL versus HSC comparison. The yellow line indicates the threshold (0.05). (B) RQ-PCR for some genes specifically highly expressed in VSELs (E2f2, Ppp2r5b, Stmn1, Tfdp1, Ezh2, and Suz12) using a single-cell cDNA library (24-cycle PCR product). Expression level (% of GAPDH) is shown as the boxed region with the median line and the “whiskers” for the extreme values, n=4. (C) Top 5 canonical pathways in IPA analysis for genes specifically expressed at a low level in VSELs. Graph bars are ordered by the experimental P value in the VSEL versus ESC comparison. (D) Heatmap analysis with hierarchical clustering for protein turnover-related genes. Red and green indicate high and low expressions, respectively. Suz, suppressor of zeste. Color images available online at www.liebertonline.com/scd

Chromatin immunoprecipitation assay

To overcome the problem of low VSEL number, we performed the carrier chromatin immunoprecipitation (ChIP) assay using human hematopoietic cell line THP-1 as carrier [29]. ChIP analysis was performed using 2×104 FACS-isolated VSELs, HSCs, MNCs, and ESC-D3 cells mixed with 5×106 THP-1 cells as a source of carrier chromatin. The ChIP procedures were performed as previously described [22]. For sequential ChIP analysis, 100 μL of chromatin eluted from the first immunoprecipitation against H3K4me3 was used as the input for the second ChIP against H3K27me3. The enrichment of each histone modification was calculated as the ratio of bound-to-unbound amplicon fractions and represented as mean±S.D. from at least 4 independent experiments. All primers used in the ChIP assay are specific to mouse sequences and they are available upon request.

RNAi

The shRNA designed against Ezh2 was used for knockdown experiments. The shRNA target sequences for LacZ and Ezh2 indicated in Fig. 6A were constructed and cloned into the pENTR™/U6 vector (Invitrogen), according to the manufacturer's instructions. The corresponding shRNA constructs were transfected into mouse embryonic fibroblast (MEF) or freshly isolated VSELs using Lipofectamine™ 2000 (Invitrogen), and 2 days (MEF) or 3 days (VSELs) after transfection, the effect of RNAi was examined by RQ-PCR and Western blotting. The antibodies specific for Ezh2 (clone AC22, monoclonal; Cell Signaling Technology), Suz12 (clone D39F6, monoclonal; Cell Signaling Technology), and β-actin (clone AC-15, monoclonal; Santa Cruz Biotechnology) were used to detect the proteins. Following shRNA construct transfection, VSELs were maintained under the same conditions described for ESC-D3 culture.

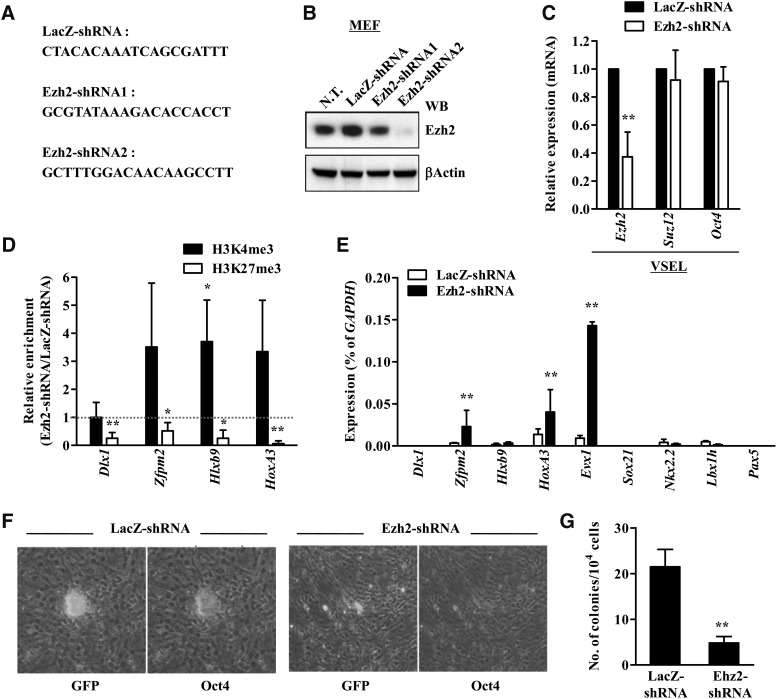

FIG. 6.

Ezh2 is essential for maintaining BD structure in VSELs. (A) The targeting sequences for the indicated shRNA constructs. (B) The knockdown effect of Ezh2-shRNA in mouse embryonic fibroblast (MEF). Western blot (WB, B) for Ezh2 expression at 2 days after transfection of the indicated shRNA constructs into MEF. (C) RQ-PCR results at 3 days after Ezh2-shRNA2 transfection into VSELs. The expression level of Ezh2, Suz12, and Oct4 transcripts was represented as a fold change between Ezh2-shRNA2–transfected and LacZ-shRNA–transfected VSELs and shown as mean±S.D. (n=4). *P<0.05, **P<0.01 as compared with LacZ-shRNA (two-way ANOVA with Bonferroni posttests). qChIP (D) and RQ-PCR (E) analysis for Ezh2 knockdown VSELs. The enrichment of H3K4me3 and H3K27me3 is depicted as the fold change between Ezh2-shRNA2–transfected and LacZ-shRNA–transfected VSELs (set as 1, dotted line) and shown as the mean±S.D. (n=4). *P<0.05, **P<0.01 compared with LacZ-shRNA (Student's t-test). The transcript level for BD is represented as the % of GAPDH and shown as the mean±S.D. (n=4). *P<0.05, **P<0.01 compared with LacZ-shRNA (two-way ANOVA with Bonferroni posttests). The Oct4 protein staining (F) and number of embryoid body-like VSEL-DSs (G) formed by freshly sorted from the bone marrow of GFP transgenic mice VSELs plated over the C2C12 myoblast. N.T., not transfected.

Immunocytochemistry

Immunocytochemistry for Oct4 (clone 9E3.2, mouse monoclonal IgG1; Millipore) and Ezh2 (clone AC22, mouse monoclonal IgG1K; Cell Signaling Technology) proteins was performed as previously described [16].

Statistical analysis

All the data in quantitative ChIP and gene expression analyses were analyzed using one-way or two-way ANOVA with Bonferroni posttests. We used the GraphPad Prism 5.0 program (GraphPad Software) and statistical significance was defined as P<0.05 or P<0.01.

Results

Global transcriptome analysis of libraries derived from 20 purified murine Oct4+ VSELs

To better characterize VSELs, we employed single-cell gene expression profiling, which was previously successfully employed for gene expression analysis in PGCs [28]. Accordingly, cDNA libraries were created from RNA isolated from single FACS-sorted, BM-derived, Sca-1+Lin−CD45− VSELs by employing (i) a reverse transcriptase step, (ii) priming with poly-A-tailed primers at both termini of the cDNA, followed by (iii) PCR amplification. We found that at least 20 singly sorted cells were required to create a cDNA library sufficient for microarray analysis.

VSEL-derived cDNA libraries created by employing this approach were first screened for expression of ESC markers, and basically 3 different types of libraries were identified based on the gene expression pattern: (i) ESC-like Oct4+Nanog+Sox2+Stella+ libraries (VSEL-1, -2, and -3), (ii) epiblast-like Stella−Prdm14− libraries (VSEL-2–1, -2–2, -2–3) [30], and (iii) libraries enriched mostly for the Oct4 transcript (VSEL-3–1, -3–2, -3–3) (Fig. 1A). Of note, none of these stemness genes was expressed in cDNA libraries created from 20 purified HSCs (Sca-1+Lin−CD45+) or bone marrow mononuclear cells (BMMNCs). These results show that FACS-isolated VSELs, as a population of Sca-1+Lin−CD45− cells, are different from other BM-derived cells; however, they seem to show some differences in gene expression.

Subsequently, for our Affymetrix microarray analysis-based global gene expression profiling, we employed 20-cell cDNA libraries from (i) Oct4+Nanog+Sox2+Stella+ ESC-like VSELs (VSEL-1, -2, and -3), (ii) Sca-1+Lin−CD45+ HSCs, and (iii) ESCs from the established cell line, ESC-D3.

First, our scatter plot and heatmap analysis with hierarchical clustering demonstrated that in addition to high expression of Oct4, Nanog, and Sox2, the VSEL transcriptome is tightly clustered with that of ESCs, while at the same time distant from HSCs (Fig. 1B, C and Supplementary Fig. S1). However, we also observed that VSELs exhibit some distinct gene expression patterns compared with both ESCs and HSCs. To illustrate this, we performed PCA mapping, which reduces the dimensionality of the data matrix by performing a covariance analysis between factors and finding new variances [31]. When VSELs, HSCs, and ESCs were projected with first 3 principal components (PCs), the total variance accounted for 67.5% with 35% for PC1, 19.8% for PC2, and 12.7% for PC3 (Fig. 1D). The differences in transcriptome between VSELs, HSCs, and ESCs were further demonstrated by the projection of each of the 3 stem cell populations as distinct clusters in PCA mapping (Fig. 1D). Comparison of cDNA libraries derived from 20 purified VSELs revealed that VSEL-2 and VSEL-3 are tightly clustered but distinct from VSEL-1 both in heatmap (Fig. 1C) and PCA analysis (Fig. 1D and Supplementary Fig. S1B). This observation indicates that VSELs seem to be somehow heterogeneous.

Next, to better characterize the VSEL transcriptome, we performed knowledge database-oriented analysis of our microarray results using IPA software, which allows one to evaluate important gene networks, biofunctions, and canonical pathways. Figure 1E showed that VSELs and ESCs had significant differences in expression of genes related to cell growth, development, and hematopoietic specification when compared with HSCs. At the same time, these differences were not significant when VSELs were compared with ESCs (Fig. 1E). Accordingly, both VSELs and ESCs showed a different expression pattern for canonical pathways involved in hematopoietic differentiation, phospholipase C (PLC)-, TNFR2-, and HGF-mediated signaling pathways, compared with HSCs (Fig. 1F). At the same time, VSELs expressed pathways related to Oct4 pluripotency and protein turnover at lower levels than ESCs (Supplementary Figs. S2 and S3). Intriguingly, we observed by gene network analysis, particularly when comparing VSELs with HSCs, that Ppp2r5 and Ezh2 genes were involved in the Oct4 pluripotency network (Fig. 1G and Supplementary Fig. S3). Taken together, these results demonstrate that primitive Oct4+ VSELs are very different from HSCs, and at the same time they have a similar, but nonidentical, gene expression profile as ESCs.

VSELs' unique pattern of gene expression

To demonstrate gene expression profiles unique to VSELs, we focused on genes that are highly or less expressed in VSELs compared with both HSCs and ESCs. This analysis revealed that several cancer (e.g., the Stathmin1 pathway) and cell cycle checkpoint-related biofunctions and canonical pathways were significantly highly expressed in VSELs (Fig. 2A). Accordingly, E2f2, Ezh2, cyclins (A2, B1, B2, D1, E1, and E2), and cell cycle checkpoint genes (e.g., Cdc20, Cdc26, Ccrn4l, Cdk1, Fzr1, Gadd45a, Hdac2, Kif11, Nbn, Ppp2r5b, Tfdp1, Rfc3, Rfc4, and Ywnhae) were highly expressed in VSELs. Interestingly, Ppp2r5b (protein phosphatase 2, regulatory subunit B56), E2f2, and Ezh2 were identified in several high-ranking target pathways specifically expressed at a high level in VSELs. The high expression of these genes in VSELs was subsequently confirmed by employing RQ-PCR (Fig. 2B).

Next, while evaluating genes that are specifically expressed at a low level in VSELs, we found that protein synthesis and ubiquitination (eIF2, eIF4, and p70S6K signaling) pathways were significantly less expressed in VSELs compared with ESCs (Fig. 2C). This was further supported by heatmap analysis indicating that VSELs exhibit distinct expression patterns for the protein translation- and ubiquitination-related genes compared with ESCs (Fig. 2D). Moreover, in addition to hematological development–related genes, VSELs significantly expressed at a low level genes encoding glucocorticoid receptor, prolactin, EGF, SAPK/JNK, and PLC signaling molecules, compared with HSCs (Supplementary Fig. S4). In support of this, transcripts for Hif1a, Tp53, Smad3, Jun, Cdc34, eIFs (eIF1, 3e, 3j, 4a2, 2b1, 4e, and 4g1), ubiquitin-conjugating enzyme (Ube2d2, Ube2e1, Ube2j1, Ube2l3, Ube2n, and Ube2q1), ubiquitin-specific peptidase (Usp3, Usp30, and Usp47), proteasome subunit (Psma4, Psmb3, Psmb6, Psmc2, Psmd12, and Psmd13), and Ras and MAPK signaling (Rras2, Kras, Nras, Map2k7, Map3k7, Map4k4, Mapk1, and Mapk14) were expressed at lower levels in VSELs. We assume that any of these pathways that are specifically less expressed in VSELs could be responsible for their quiescence, differentiation, or ageing. In sum, VSELs, in addition to Oct4 pluripotency network genes, expressed a unique transcriptome (e.g., E2fs, cell cycle checkpoint genes, and genes that regulate protein turnover).

VSELs highly express PcG and TrG proteins

Our 20-cell microarray results revealed that VSELs highly expressed E2f2-related pathways (Supplementary Fig. S5E), and Ezh2 is one of the E2fs' targets that directly interacted with the Oct4 pluripotency network (Fig. 1G). Since the promoters of the PRC2 core member target genes are occupied with Oct4 protein in murine and human ESCs [32], we have hypothesized that PcG proteins, especially Ezh2, could regulate VSEL pluripotency. Our RQ-PCR analysis of PcG genes, performed on cDNA libraries from 20 purified cells, revealed that the Ezh2 transcript was expressed at the highest level in VSELs (Fig. 3A, B). Ezh2 expression was subsequently confirmed at the protein level by immunohistochemical staining of these cells (Supplementary Fig. S5D). Ezh1 protein that is homologous to Ezh2 can form the PRC2 functional complex as HMTase for H3K27 in the absence of Ezh2 [33,34]. We noticed that VSELs show similar level of Ezh1 expression as other cells investigated in our studies (Fig. 3A, B).

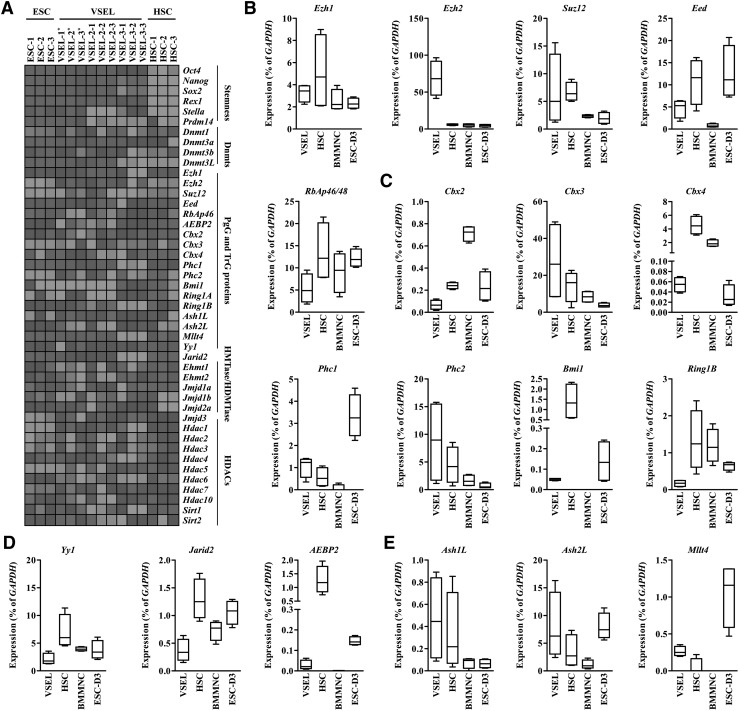

FIG. 3.

Expression of polycomb group and TrG transcripts in murine VSELs. (A) Heatmap analysis of Ct values from RQ-PCR experiments for stemness and chromatin-modifying factors using the indicated cDNA libraries from 20 purified cells. Asterisk (*) in Fig. 1A indicates VSEL libraries used for microarray analysis. Heatmap analysis of Ct values from RQ-PCR experiments was prepared employing Heatmap Builder® software (Stanford School of Medicine). The expression level is shown as dark (high expression) and light (low expression) gray. RQ-PCR results for PRC2 core members (B), PRC1 (C), PRC recruiting (D), TrG genes (E) using the indicated 20-cell cDNA libraries (24-cycle PCR product). Expression level (% of GAPDH) was shown as the boxed region with the black bar for the median and the “whiskers” for the extreme values; n=4. PRC, polycomb repressive complex.

Next, we observed that the Suz12 transcript, in particular, was highly expressed in Stella− VSELs. Furthermore, VSELs expressed Eed and RbAp46 transcripts, but at lower levels compared with HSCs and ESCs (Fig. 3B). Because PcG proteins lack their own DNA binding activity, they need binding partners (Yy1, AEBP2, and Jarid2 proteins) in order to be recruited to the target genes [35–37]. VSELs expressed transcripts for all these PRC recruiters, however, again at a lower level than HSCs and ESCs (Fig. 3D). Furthermore, as shown in Fig. 3C, while other PRC1 members (Cbx3 and Phc2) were expressed in VSELs at a high level, the genes for Ring finger–containing proteins (Ring1B and Bmi1) were expressed at a lower level. Interestingly, VSELs highly expressed some other cellular memory machinery transcripts from the TrG family, such as Ash1L, Ash2L, and Mllt4 (Fig. 3E).

Because chromatin-modifying proteins are essential for defining the cell type–specific signature of gene expression, we focused on expression of these regulatory molecules. Accordingly, as shown in Supplementary Fig. S5A–C, VSELs highly expressed Dnmt1, Dnmt3L, Jmjd2a, Jmjd3, HDAC1, HDAC2, HDAC3, SIRT1, and SIRT2, but both Ehmt1 and Ehmt2 were expressed at a lower level. Taken together, these results demonstrate that VSELs exhibit a unique expression pattern for chromatin regulatory factors.

VSELs repress expression of some developmental genes in a BD-dependent manner

It is well-known that PcG proteins play an essential role for maintaining BD in which both transcriptionally active histones (H3K4me3) and repressive ones (H3K27me3) are physically colocalized in the same promoter region [9,12]. The PcG-regulated, BD-mediated transcriptional silencing of important homeodomain-containing developmental genes is essential for maintaining PSCs in an undifferentiated state [9–12]. Based on the fact that Ezh2 is highly expressed in VSELs, to examine its potential involvement in BD maintenance as an H3K27me3 histone modifier, we examined the status of the H3K27me3 histone modification in the promoters of several developmental master TFs by carrier ChIP [22]. Figure 4A shows that for most of the TFs tested, all 3 stem cell populations (VSELs, HSCs, and ESCs) showed similar levels of the H3K27me3 modification. We also observed that VSELs showed the highest levels of H3K27me3 at the promoters encoding Hlxb9, Pax5, and HoxA3 genes, and the lowest levels at the Irx2 promoter.

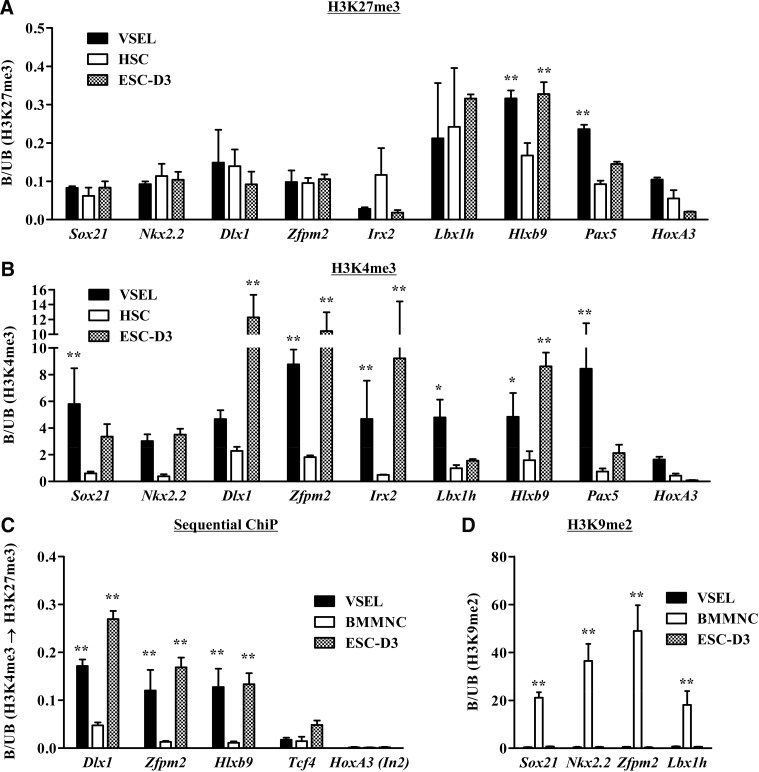

FIG. 4.

BD structures in the promoters of developmental master TFs in murine VSELs. qChIP analysis for H3K27me3 (A), H3K4me3 (B), and H3K9me2 (D) for the promoters of the BD target genes in the indicated cells. The enrichment of the indicated histone codes was shown as the mean±S.D. (n=4). *P<0.05, **P<0.01 compared with HSCs (A, B) or BMMNCs (D). (C) Sequential ChIP analysis for H3K4me3, followed by H3K27me3 for BD target genes. Note that low level of sequential ChIP product has been detected in the H3K4me3-modified locus (Tcf4) and no sequential ChIP product in H3K27me3-modified (intron 2 [In2] in HoxA3) locus. All experiments are shown as the mean±S.D. (n=4). *P<0.05, **P<0.01 compared with BMMNCs. Two-way ANOVA with Bonferroni posttests was used for statistical analysis. BD, bivalent domain; TFs, transcription factors; ChIP, chromatin immunoprecipitation; H3K27me3, trimethylated lysine27 of histone3; BMMNCs, bone marrow mononuclear cells; ANOVA, analysis of variance.

At the same time, similarly as reported for ESCs, all these TF promoters in VSELs were highly enriched for the opposite, transcription-activating histone modification, H3K4me3 (Fig. 4B). In contrast, HSCs and BMMNCs did not show this ESC-like BD structure in respective promoters. To confirm the physical co-occupancy of 2 transcriptionally opposite histone marks, we performed the sequential ChIP assay, in which the chromatin of interest was first immunoprecipitated by anti-H3K4me3 antibodies and subsequently pulled down by employing anti-H3K27me3 antibodies. As shown in Fig. 4C, like ESCs, VSELs showed the physical co-occupancy of H3K4me3 and H3K27me3 histone codes only at the promoter region of BD-targeted TFs, but not at the promoter of Tcf4 and intron region of HoxA2, which show only H3K4me3 and H3K27me3 modifications, respectively (Supplementary Fig. S6).

As mentioned previously, the BD structure, as a transiently repressive epigenetic mark, is less associated with histone codes that stably repress transcription (e.g., H3K9me2 or me3), and thus is poised for easy activation in response to developmental cues [38]. In support of this, Fig. 4D and Supplementary Fig. S7 show that in contrast to BMMNCs, the promoters for BD-regulated TFs in VSELs and ESCs were less enriched for H3K9me2- and H3K9me3-modified histones. Next, to test the functional role of BD structure found on VSELs, we examined the expression level of genes that are regulated in a BD-dependent manner. As shown in Supplementary Fig. S8, most of the BD-targeted genes tested were not transcribed in VSELs and ESC-D3 cells. In sum, our results demonstrate that undifferentiated VSELs maintain their primitive state through BD-mediated transcriptional silencing of some important TFs that are master regulators of development.

Role of Ezh2 in the maintenance of BD in VSELs

We have reported that VSELs, when plated over C2C12 cells, proliferate and form characteristic spheres. We also reported that cells isolated from VSEL-DSs become not only progressively enriched for more differentiated stem cells but also show progressive DNA methylation of the Oct4 promoter and reverse their genomic imprinting to the normal somatic pattern [22]. In support of the previous report, we observed that the Oct4 promoter in 7-day-old VSEL-DS became enriched for H3K27me3, and that this phenomenon was paralleled by a decrease in promoter-associated H3K4me3-modified histones (Fig. 5A). Consistent with these epigenetic changes, we demonstrated here that the expression of other stemness genes (except Stella) also progressively decreased during VSEL-DS formation (Fig. 5C).

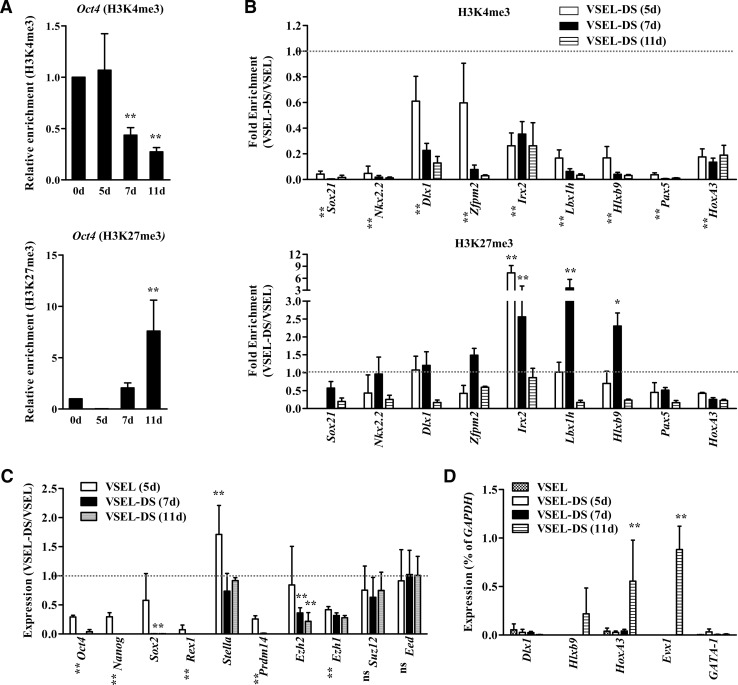

FIG. 5.

BD structure disappears during VSEL differentiaton. qChIP analysis for Oct4 (A) and BD target gene (B) promoters for cells isolated from VSEL-DSs on the indicated days. The enrichment of H3K4me3 (upper panel) and H3K27me3 (lower panel) is depicted as a fold change between the indicated days of VSEL-DS and freshly isolated VSELs day 0 (set as fold change of 1, dotted line) and shown as mean±S.D. (n=4). *P<0.05, **P<0.01 compared with day 0 (two-way ANOVA with Bonferroni posttests). Genes that show a statistically significant P value (<0.01) in all the experimental groups are shown by an asterisk to the left of each gene. RQ-PCR for stemness, PRC2 core member (C), and BD genes (D) on the indicated days for VSEL-DSs. The expression level was calculated as the ratio of the value of VSEL-DS to VSEL (set as 1, dotted line, C) or as the % of GAPDH (D) and is shown as mean±S.D. (n=4). *P<0.05, **P<0.01 compared with day 0 (two-way ANOVA with Bonferroni posttests). VSEL-DSs, VSEL-derived spheres.

Interestingly, we also observed that of all the PRC2 core members, the Ezh1 and Ezh2 genes were specifically downregulated during VSEL-DS formation (Fig. 5C). Based on this observation, we became interested in whether the decrease in Ezh2 expression could affect the presence of BDs at promoters of developmentally important TFs. Interestingly, we observed that the H3K4me3 histone mark was rapidly removed beginning at day 5 of VSEL-DS formation, and at day 11 most of the promoters of BD-regulated gene promoters have lost this epigenetic mark in cells isolated from VSEL-DSs (Fig. 5B, upper panel). In particular, H3K4me3 was rapidly eliminated in the Sox21, Nkx2.2, and Pax5 promoters. Furthermore, the H3K27me3 mark was also progressively lost in most BD-containing gene promoters during VSEL-DS formation; however, it showed in developing VSEL-DSs, at day 7, elevated association with promoters of some genes (Fig. 5B, lower panel). Finally, in cells isolated from day-11 VSEL-DS, which were already highly enriched for differentiated cells, most of the TF gene promoters lost their BD character and become unmarked for both histone codes.

Moreover, although most BD target genes became repressed at early stages of VSEL-DS formation (Supplementary Fig. S9), the expression of some BD-regulated genes, like Hlxb9, HoxA3, and Evx1, which were highly enriched for H3K27me3 in VSELs (Fig. 4A), were first de-repressed on day 11 of VSEL-DS formation (Fig. 5D). In control experiments, no changes were detected in non-BD–regulated target genes, such as GATA1. Therefore, our results suggest that downregulation of Ezh2 during VSEL-DS formation could destabilize BD structures, leading to de-repression of some BD target genes and promoting cell differentiation.

Finally, to better support a potential role for Ezh2 in maintaining the stability of BD structures in VSELs, we employed RNAi-based approach using shRNA against Ezh2. As shown in Fig. 6A, B, we designed 2 shRNA constructs for Ezh2 and examined their knockdown effect in MEF by RQ-PCR and Western blot. Both shRNA constructs significantly reduced the transcript and protein of Ezh2 (Fig. 6B). The Ezh2-shRNA2 construct was used for further transfection experiments for VSELs since its knockdown effect was more than that of Ezh2-shRNA1. As shown in Fig. 6C, by day 3 after shRNA transfection of freshly isolated VSELs, the Ezh2 transcript level decreased ∼50%; however, the expression of Suz12 and Oct4 mRNAs was almost unaffected. Interestingly, when we examined the histone modifications in the promoters for selected relevant BD-containing genes, Ezh2 knockdown significantly decreased their association with H3K27me3, and resulted in enrichment for H3K4me3 (Fig. 6D). Most importantly, loss of BDs induced by Ezh2 knockdown coincided with the de-repression of Zfpm2, HoxA3, and Evx1 (Fig. 6E).

Next, to examine whether the Ezh2 knockdown could affect the developmental potential of VSELs, we employed sphere formation assay in cocultures with myoblastic C2C12 cells. In this coculture system as reported [16], VSELs form embryoid body-like structures called VSEL-DSs. VSEL-DSs contain primitive stem cells that are able to differentiate into cells from all 3 germ layers. To address effect of Ezh2 knockdown on formation of VSEL-DSs, VSELs were freshly isolated from the BM of GFP transgenic mice and transfected with Ezh2-shRNA or LacZ-shRNAs for 1 day, followed by the coculture over C2C12 cells for further 4 days. As shown in Fig. 6F and 6G, VSELs treated with LacZ-shRNAs formed characteristic Oct4+ VSEL-DSs, which contain cells able to differentiate into all 3 germ layers. In contrast, Ezh2 knockdown in VSELs significantly impeded their potential to form VSEL-DS formation. At the same time we observed that Oct4 protein was downregulated in the majority of GFP+ cells (Fig. 6F, G), indicating that Ezh2 could play an essential role on maintaining their pluripotency. Since downregulation of Ezh2 inhibited the ability of VSELs to form VSEL-DSs, we assume that this gene is not only critical to maintain pluripotentiality of VSELs but also plays an important role in their ex vivo expansion and differentiation. Taken together, these results demonstrate that Ezh2 expression in VSELs, as for ESCs, is responsible for maintaining the stability of BD in the promoters of important developmental TFs and thus regulates the pluripotent state of VSELs.

Discussion

In the current study, for the first time we demonstrate the global gene expression profile of murine BM-purified Oct4+ VSELs by employing a single-cell approach. Our transcriptome comparison analysis followed by functional studies demonstrates that VSELs, like ESCs, regulate their pluripotent state in Ezh2-dependent manner by maintaining (i) the Oct4 pluripotency network and (ii) BD structures at developmentally important TFs (Fig. 7). We also found that VSELs express at a low level genes that encode proteins involved in protein turnover (e.g., eIF4 and mTOR signaling, proteosome subunits, and ubiquitin-conjugating enzymes) and genes for growth factor/mitogen activated signaling proteins (e.g., K-Ras, N-Ras, PI3K, PKA, PKC, and PLC) (Supplementary Fig. S10). However, at the same time they express at a high level several cell cycle checkpoint-related genes, which could affect their quiescent state. In support of this, relative to HSCs, VSELs show a low expression of genes that govern the small G protein–related pathways at the level of guanine nucleotide exchange factors (e.g., RasGRF1), small G proteins themselves (Rac1, Rac2, RhoB, RhoF, and RhoT1), and effecter molecules (e.g., Rocks, Pak2, Ccd42EPs, and Cdc42SEs). Because G-protein–coupled signals are involved in cell trafficking and adhesion [39] and as previously demonstrated, VSELs are a mobile population of cells [40,41]. Further studies are needed to address changes in expression of these genes in the context of their high motility and mobilization into peripheral blood during various stress situations.

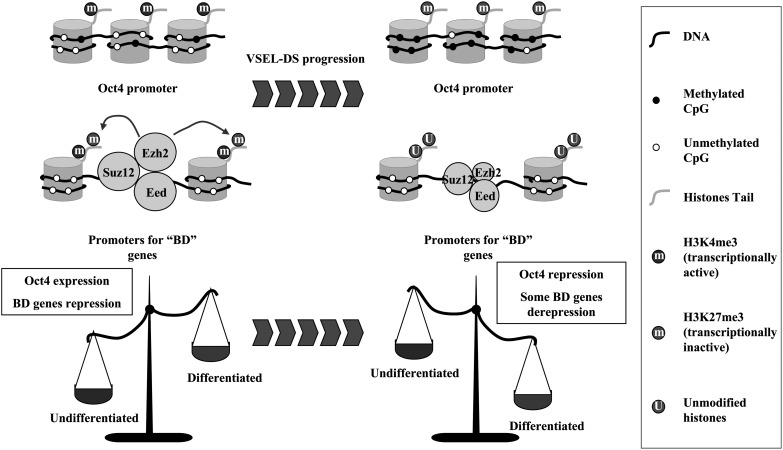

FIG. 7.

Putative model for VSEL pluripotency. Both Oct4 expression due to open chromatin structure in its promoter and Ezh2-mediated BD structure maintain VSELs as ESC-like pluripotent status. During differentiation (e.g., VSEL-DS formation), the expression of pluripotency-specific genes disappears and at the same time, the decrease of Ezh2 expression leads to the de-repression of corresponding developmental TFs.

Interestingly, compared with ESCs and HSCs, VSELs exhibit the highest expression of Ppp2r5b, E2f2, and Ezh2 transcripts (Fig. 2B), and indeed these genes are frequently observed in several high-ranking VSEL canonical pathways, specifically highly expressed pathways. Consistent with high expression of E2f2, VSELs also show the highest expression of Ezh2, together with PRC proteins (Fig. 3B, C), which explains why they, like ESCs, exhibit BDs in development-related TFs (Fig. 4). By employing a VSEL-DS formation assay combined with direct Ezh2 knockdown experiments, we further confirmed that high expression of Ezh2 is crucial for maintenance of BD structure and transcriptional repression of promoters of several development-related TFs (Figs. 5 and 6). Therefore, we propose that the Ezh2-mediated presence of BD structures is one of the mechanisms that both VSELs and ESCs share to maintain their pluripotent character. Because most primitive VSELs exhibit strikingly high expression of Ezh2, we propose that mice that express GFP under the Ezh2 promoter would be a useful model, both to isolate these rare cells by FACS as well as to visualize and track in vivo–transplanted VSELs.

We observed that following transfection with Ezh2-shRNA, VSELs lose BDs in promoters of developmentally important TFs and de-repress some of the BD-regulated genes, including Zfpm2, HoxA3, and Evx1 (Fig. 6D, E). However, for VSELs in which Ezh2 was downregulated, the depletion of H3K27me3 histone and enrichment for H3K4me3 in promoters of Dlx1 and Hlxb9 genes was not significantly correlated with increased transcription of these genes. Because the expression of many genes is regulated by their own transcriptional activators and/or repressors, it is possible that, in addition to abrogation of H3K27me3, the upregulation of gene-specific activators and/or downregulation of repressors is required for proper gene induction, as seen for the Dlx1 and Hlxb9 genes.

We were aware from the beginning of our studies that phenotypically similar VSELs may be heterogeneous. To address this issue, in the current study, we established several Oct4-positive cDNA libraries from 20 BM-sorted Sca-1+Lin−CD45− VSELs. We observed that these libraries differ in expression of some crucial stemness genes and 3 patterns of gene expression were identified (Fig. 1A). The first group, which we employed for microarray analysis in the current study, is similar to cells from the inner cell mass and PGCs, since they express both stemness (e.g., Oct4 or Nanog) and germ-line markers (e.g., Stella and Prdm14). The second group, which expresses stemness genes (e.g., Oct4 or Nanog), but lack germ-line markers (Stella and Prdm14), resembles the population of epiblast cells. The third group expressing Oct4, however, is further differentiated and lacks several genes that are present in other VSELs [42]. Thus, these different gene expression patterns in VSELs support our previous observations that these cells express molecular characteristics in common with epiblast and migrating PGCs [21]. At the same time, we provide molecular evidence that despite displaying similar morphology and expressing similar surface markers, VSELs differ between themselves in expression of several genes (Fig. 3A). We are currently trying to address the biological implications of this heterogeneity by comparing the global transcriptomes of all 3 types of libraries representing these different suites of VSEL molecular characteristics. The comparison of the libraries from 20 purified VSELs representing epiblast-like (2nd group) and from 20 purified Oct4-positive VSELs (3rd group) will be a subject of the separate study.

In conclusion, our global transcriptome analysis demonstrates that VSELs highly express E2F pathways, as well as some PcG and TrxG proteins, but express at a low level several genes involved in protein turnover and growth factor/mitogen stimulation. We also provide evidence that like ESCs, the Ezh2-dependent BD mechanism contributes to the pluripotent state of VSELs. Finally, changes in expression of some crucial genes identified in VSELs (e.g., E2f2, Ppp2r5b, Stmn1, Jun, Fos, Fyn, Jak1, Stat1, and Kras) will be essential for optimizing their expansion protocols, which is of critical importance for their potential application in the clinic.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The authors thank V. Arumugam and Y. Chen for technical support in the Affymetrix microarray analysis. This work was supported by NIH P20RR018733 from the National Center for Research Resources to Magda Kucia and NIH R01 DK074720, EU Innovative Economy Operational Program POIG.01.01.02-00-109/09 and the Henry M. and Stella M. Hoenig Endowment to Mariusz Z. Ratajczak. Part of this work was performed with the assistance of the University of Louisville Microarray Facility, which is supported by NCRR IDeA Awards INBRE-P20 RR016481 and COBRE-P20RR018733, the James Graham Brown Foundation, and user fees.

Author Disclosure Statement

The authors declare that they have no competing financial interests.

References

- 1.Evans MJ. Kaufman MH. Establishment in culture of pluripotential cells from mouse embryos. Nature. 1981;292:154–156. doi: 10.1038/292154a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Brons IGM. Smithers LE. Trotter MWB. Rugg-Gunn P. Sun B. Chuva de Sousa Lopes SM. Howlett SK. Clarkson A. Ahrlund-Richter L. Pedersen RA. Vallier L. Derivation of pluripotent epiblast stem cells from mammalian embryos. Nature. 2007;448:191–195. doi: 10.1038/nature05950. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Tesar PJ. Chenoweth JG. Brook FA. Davies TJ. Evans EP. Mack DL. Gardner RL. McKay RDG. New cell lines from mouse epiblast share defining features with human embryonic stem cells. Nature. 2007;448:196–199. doi: 10.1038/nature05972. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Matsui Y. Zsebo K. Hogan BLM. Derivation of pluripotential embryonic stem cells from murine primordial germ cells in culture. Cell. 1992;70:841–847. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(92)90317-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Takahashi K. Yamanaka S. Induction of pluripotent stem cells from mouse embryonic and adult fibroblast cultures by defined factors. Cell. 2006;126:663–676. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2006.07.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Niwa H. How is pluripotency determined and maintained? Development. 2007;134:635–646. doi: 10.1242/dev.02787. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Shenghui H. Nakada D. Morrison SJ. Mechanisms of stem cell self-renewal. Annu Rev Cell Dev Biol. 2009;25:377–406. doi: 10.1146/annurev.cellbio.042308.113248. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Pietersen AM. van Lohuizen M. Stem cell regulation by polycomb repressors: postponing commitment. Curr Opin Cell Biol. 2008;20:201–207. doi: 10.1016/j.ceb.2008.01.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bernstein BE. Mikkelsen TS. Xie X. Kamal M. Huebert DJ. Cuff J. Fry B. Meissner A. Wernig M, et al. A bivalent chromatin structure marks key developmental genes in embryonic stem cells. Cell. 2006;125:315–326. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2006.02.041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Boyer LA. Plath K. Zeitlinger J. Brambrink T. Medeiros LA. Lee TI. Levine SS. Wernig M. Tajonar A, et al. Polycomb complexes repress developmental regulators in murine embryonic stem cells. Nature. 2006;441:349–353. doi: 10.1038/nature04733. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Stock JK. Giadrossi S. Casanova M. Brookes E. Vidal M. Koseki H. Brockdorff N. Fisher AG. Pombo A. Ring1-mediated ubiquitination of H2A restrains poised RNA polymerase II at bivalent genes in mouse ES cells. Nat Cell Biol. 2007;9:1428–1435. doi: 10.1038/ncb1663. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lee TI. Jenner RG. Boyer LA. Guenther MG. Levine SS. Kumar RM. Chevalier B. Johnstone SE. Cole MF, et al. Control of developmental regulators by polycomb in human embryonic stem cells. Cell. 2006;125:301–313. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2006.02.043. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Azuara V. Perry P. Sauer S. Spivakov M. Jorgensen HF. John RM. Gouti M. Casanova M. Warnes G. Merkenschlager M. Fisher AG. Chromatin signatures of pluripotent cell lines. Nat Cell Biol. 2006;8:532–538. doi: 10.1038/ncb1403. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ringrose L. Paro R. Epigenetic regulation of cellular memory by the polycomb and trithorax group proteins. Annu Rev Genet. 2004;38:413–443. doi: 10.1146/annurev.genet.38.072902.091907. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Simon JA. Kingston RE. Mechanisms of Polycomb gene silencing: knowns and unknowns. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2009;10:697–708. doi: 10.1038/nrm2763. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kucia M. Reca R. Campbell FR. Zuba-Surma E. Majka M. Ratajczak J. Ratajczak MZ. A population of very small embryonic-like (VSEL) CXCR4+ SSEA-1+Oct-4+stem cells identified in adult bone marrow. Leukemia. 2006;20:857–869. doi: 10.1038/sj.leu.2404171. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kucia M. Halasa M. Wysoczynski M. Baskiewicz-Masiuk M. Moldenhawer S. Zuba-Surma E. Czajka R. Wojakowski W. Machalinski B. Ratajczak MZ. Morphological and molecular characterization of novel population of CXCR4+ SSEA-4+Oct-4+very small embryonic-like cells purified from human cord blood—preliminary report. Leukemia. 2006;21:297–303. doi: 10.1038/sj.leu.2404470. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Zuba-Surma EK. Kucia M. Rui L. Shin D-M. Wojakowski W. Ratajczak J. Ratajczak MZ. Fetal liver very small embryonic/epiblast like stem cells follow developmental migratory pathway of hematopoietic stem cells. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2009;1176:205–218. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.2009.04562.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Parte S. Bhartiya D. Telang J. Daithankar V. Salvi V. Zaveri K. Hinduja I. Detection, characterization, and spontaneous differentiation in vitro of very small embryonic-like putative stem cells in adult mammalian ovary. Stem Cells Dev. 2011;20:1451–1464. doi: 10.1089/scd.2010.0461. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar] [Retracted]

- 20.Bhartiya D. Kasiviswanathan S. Unni SK. Pethe P. Dhabalia JV. Patwardhan S. Tongaonkar HB. Newer insights into premeiotic development of germ cells in adult human testis using Oct-4 as a stem cell marker. J Histochem Cytochem. 2010;58:1093–1106. doi: 10.1369/jhc.2010.956870. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Shin DM. Liu R. Klich I. Wu W. Ratajczak J. Kucia M. Ratajczak MZ. Molecular signature of adult bone marrow-purified very small embryonic-like stem cells supports their developmental epiblast/germ line origin. Leukemia. 2010;24:1450–1461. doi: 10.1038/leu.2010.121. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Shin DM. Zuba-Surma EK. Wu W. Ratajczak J. Wysoczynski M. Ratajczak MZ. Kucia M. Novel epigenetic mechanisms that control pluripotency and quiescence of adult bone marrow-derived Oct4+very small embryonic-like stem cells. Leukemia. 2009;23:2042–2051. doi: 10.1038/leu.2009.153. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Taichman RS. Wang Z. Shiozawa Y. Jung Y. Song J. Balduino A. Wang J. Patel LR. Havens AM, et al. Prospective identification and skeletal localization of cells capable of multilineage differentiation in vivo. Stem Cells Dev. 2010;19:1557–1570. doi: 10.1089/scd.2009.0445. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Dawn B. Tiwari S. Kucia MJ. Zuba-Surma EK. Guo Y. SanganalMath SK. Abdel-Latif A. Hunt G. Vincent RJ, et al. Transplantation of bone marrow-derived very small embryonic-like stem cells attenuates left ventricular dysfunction and remodeling after myocardial infarction. Stem Cells. 2008;26:1646–1655. doi: 10.1634/stemcells.2007-0715. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Zuba-Surma EK. Guo Y. Taher H. Sanganalmath SK. Hunt G. Vincent RJ. Kucia M. Abdel-Latif A. Tang X-L, et al. Transplantation of expanded bone marrow-derived very small embryonic-like stem cells (VSEL-SCs) improves left ventricular function and remodeling after myocardial infarction. J Cell Mol Med. 2010;15:1319–1328. doi: 10.1111/j.1582-4934.2010.01126.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ratajczak J. Zuba-Surma E. Klich I. Liu R. Wysoczynski M. Greco N. Kucia M. Laughlin MJ. Ratajczak MZ. Hematopoietic differentiation of umbilical cord blood-derived very small embryonic/epiblast-like stem cells. Leukemia. 2011;25:1278–1285. doi: 10.1038/leu.2011.73. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ratajczak J. Wysoczynski M. Zuba-Surma E. Wan W. Kucia M. Yoder MC. Ratajczak MZ. Adult murine bone marrow-derived very small embryonic-like stem cells differentiate into the hematopoietic lineage after coculture over OP9 stromal cells. Exp Hematol. 2011;39:225–237. doi: 10.1016/j.exphem.2010.10.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kurimoto K. Yabuta Y. Ohinata Y. Saitou M. Global single-cell cDNA amplification to provide a template for representative high-density oligonucleotide microarray analysis. Nat Protoc. 2007;2:739–752. doi: 10.1038/nprot.2007.79. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.O'Neill LP. VerMilyea MD. Turner BM. Epigenetic characterization of the early embryo with a chromatin immunoprecipitation protocol applicable to small cell populations. Nat Genet. 2006;38:835–841. doi: 10.1038/ng1820. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Hayashi K. Lopes SMCdS. Tang F. Surani MA. Dynamic equilibrium and heterogeneity of mouse pluripotent stem cells with distinct functional and epigenetic states. Cell Stem Cell. 2008;3:391–401. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2008.07.027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Raychaudhuri S. Stuart JM. Altman RB. Principal components analysis to summarize microarray experiments: application to sporulation time series. Pac Symp Biocomput. 2000:455–466. doi: 10.1142/9789814447331_0043. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Squazzo SL. O'Geen H. Komashko VM. Krig SR. Jin VX. Jang S-W. Margueron R. Reinberg D. Green R. Farnham PJ. Suz12 binds to silenced regions of the genome in a cell-type-specific manner. Genome Res. 2006;16:890–900. doi: 10.1101/gr.5306606. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Shen X. Liu Y. Hsu Y-J. Fujiwara Y. Kim J. Mao X. Yuan G-C. Orkin SH. EZH1 Mediates methylation on histone H3 lysine 27 and complements EZH2 in maintaining stem cell identity and executing pluripotency. Mol Cell. 2008;32:491–502. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2008.10.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Margueron R. Li G. Sarma K. Blais A. Zavadil J. Woodcock CL. Dynlacht BD. Reinberg D. Ezh1 and Ezh2 maintain repressive chromatin through different mechanisms. Mol Cell. 2008;32:503–518. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2008.11.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Peng JC. Valouev A. Swigut T. Zhang J. Zhao Y. Sidow A. Wysocka J. Jarid2/Jumonji coordinates control of PRC2 enzymatic activity and target gene occupancy in pluripotent cells. Cell. 2009;139:1290–1302. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2009.12.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Kim H. Kang K. Kim J. AEBP2 as a potential targeting protein for Polycomb repression complex PRC2. Nucleic Acids Res. 2009;37:2940–2950. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkp149. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Caretti G. Di Padova M. Micales B. Lyons GE. Sartorelli V. The Polycomb Ezh2 methyltransferase regulates muscle gene expression and skeletal muscle differentiation. Genes Dev. 2004;18:2627–2638. doi: 10.1101/gad.1241904. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Ohm JE. McGarvey KM. Yu X. Cheng L. Schuebel KE. Cope L. Mohammad HP. Chen W. Daniel VC, et al. A stem cell-like chromatin pattern may predispose tumor suppressor genes to DNA hypermethylation and heritable silencing. Nat Genet. 2007;39:237–242. doi: 10.1038/ng1972. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Gu Y. Filippi M-D. Cancelas JA. Siefring JE. Williams EP. Jasti AC. Harris CE. Lee AW. Prabhakar R, et al. Hematopoietic cell regulation by Rac1 and Rac2 guanosine triphosphatases. Science. 2003;302:445–449. doi: 10.1126/science.1088485. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Wojakowski W. Tendera M. Kucia M. Zuba-Surma E. Paczkowska E. Ciosek J. Halasa M. Król M. Kazmierski M, et al. Mobilization of bone marrow-derived Oct-4+SSEA-4+very small embryonic-like stem cells in patients with acute myocardial infarction. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2009;53:1–9. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2008.09.029. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Paczkowska E. Kucia M. Koziarska D. Halasa M. Safranow K. Masiuk M. Karbicka A. Nowik M. Nowacki P. Ratajczak MZ. Machalinski B. Clinical evidence that very small embryonic-like stem cells are mobilized into peripheral blood in patients after stroke. Stroke. 2009;40:1237–1244. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.108.535062. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Surani MA. Hayashi K. Hajkova P. Genetic and epigenetic regulators of pluripotency. Cell. 2007;128:747–762. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2007.02.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.