Abstract

In continuation of a previous work that transgene expression of sonic hedgehog promoted neo-vascularization via netrin-1 release, the current study was aimed at assessing the anti-apoptotic and pro-angiogenic role of netrin-1 transgene overexpression in the ischemic myocardium. pLP-Adeno-X ViralTrak vectors containing netrin-1 cDNA amplified from rat mesenchymal stem cells (Ad-netrin) or without a therapeutic gene (Ad-null) were constructed and transfected into HEK-293 cells to produce Ad-netrin and Ad-null vectors. Sca-1+-like cells were isolated and propagated in vitro and were successfully transduced with Ad-netrin transduced Sca-1+ cells (NetSca-1+) and Ad-null transduced Sca-1+ cells (NullSca-1+). Overexpression of netrin-1 in NetSca-1+ was confirmed by reverse transcription–polymerase chain reaction and western blot. Neonatal cardiomyocytes and rat endothelial cells expressed netrin-1 specific receptor Uncoordinated-5b and the conditioned medium from NetSca-1+ cells was protective for both the cell types against oxidant stress. For in vivo studies, the rat model of myocardial ischemia/reperfusion injury was developed in female Wistar rats by left anterior descending coronary artery occlusion for 45 min followed by reperfusion. The animals were grouped to receive 70 μL of Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium without cells (group-1), containing 2×106 NullSca-1+ cells (group-2) and NetSca-1+ cells (group-3). NetSca-1+ cells significantly reduced ischemia/reperfusion injury in the heart and preserved the global heart function in group-3 (P<0.05 vs. groups-1 and group-2). Ex-vivo netrin-1 overexpression in the heart increased NOS activity in the heart. Blood vessel density was significantly higher in group-3 (P<0.05 vs. controls). We concluded that netrin-1 decreased apoptosis in cardiomyocytes and endothelial cells via activation of Akt. Netrin-1 transgene expression was proangiogenic and effectively reduced ischemia/reperfusion injury to preserve global heart function.

Introduction

Netrins comprise a family of laminin-related diffusible proteins that were recognized as axon guidance cue [1]. Recent studies have proposed their participation in embryonic and pathological angiogenesis [2,3]. Three secreted netrins (netrins-1, 3 and 4) have been identified in mammals, in addition to the two GPI anchored membranes proteins: netrin-G1 and netrin-G2. Netrin-1 is also a potent vascular mitogen and promotes proliferation, migration, and adhesion of endothelial cells and vascular smooth muscle cells [4]. The specific activity of netrin-1 on endothelial cells is comparable to vascular endothelial growth factor and platelet-derived growth factor (PDGF); and, therefore, netrin-1 is one of the most extensively studied members of the netrin family of proteins [3,5]. Secreted netrins function via interaction with the six specific receptors to mediate their physiological and pathological effects. The deleted in colorectal cancer (DCC) and neogenin mediate chemoattractant activity of netrin-1, whereas uncoordinated-5 (UNC5) family of receptors, including UNC5 a-d, mediate repulsion by forming a netrin-1 dependent complex either alone or with DCC family of receptors [6]. In addition to axon guidance, netrin-1/UNC5b ligand/receptor interaction is required during embryonic vascular patterning, thus suggesting that it may also contribute to postnatal and pathological angiogenesis [7]. In one of our recent studies, we have shown that transgenic overexpression of sonic hedgehog in the infarcted heart promoted netrin-1 mediated angiogenic response [8]. We also showed that recombinant netrin-1 protein administration stimulated angiogenic response in the infarcted heart, which was similar to transgenic shh overexpression. The prime objective of this study was to determine the effectiveness of ex-vivo delivery of netrin-1 transgene as an angio-competent factor in the heart and to elucidate its downstream signaling mechanism.

Materials and Methods

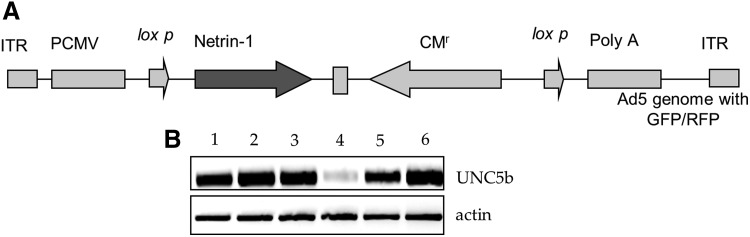

Construction and propagation of adenoviral vectors

pLP-Adeno-ViralTrak vector containing netrin-1 cDNA amplified from rat mesenchymal stem cells (MSCs) (Ad-netrin) was constructed by using a commercially available Adeno-X™ Expression System 2 kit. A vector without therapeutic gene (Ad-null) was also developed for use as a control. Description of the vector is shown in Figure 1A. Ad-netrin and Ad-null viral vectors were propagated in HEK-293 cells using Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium (DMEM; GIBCO Invitrogen) supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum [9]. The supernatants from the respective vector-transduced HEK-293 cells were collected, purified, and used in further experimentation.

FIG. 1.

Construction of Ad-netrin-1 vector and UNC5b expression on different cell types. (A) Construction of Ad-Netrin-1 vector with GFP reporter gene. (B) Reverse transcription–polymerase chain reaction (RT-PCR) showing distribution of netrin-1 receptor UNC5b in; lane-1=NullSca-1+ cells, lane-2=NetSca-1+; lane-3=neonatal cardiomyocytes; lane-4=HUVEC; lane-5=rat endothelial cells; and lane-6=heart as a positive control. NetSca-1+, Ad-netrin transduced Sca-1+ cells; NullSca-1+, Ad-null transduced Sca-1+ cells. UNC5, uncoordinated-5.

Isolation of the Sca-1+ like cell population

Sca-1+ like cell population (Sca-1+ cells) was isolated from male Wistar rat heart by using EasySep® isolation kit (Stem Cell Technology Inc.) as per instructions of the manufacturer. The cells were propagated in vitro and used for netrin-1 transgene transduction.

Netrin-1 transgene transduction and in vitro characterization of cells

Transduction of the cells for netrin-1 overexpression was carried out using our standard protocol as described earlier with slight modifications [9]. The cells were cultured in DMEM containing 1×109 adenoviral particles/mL for 4 h. At the end of transduction, the cells were washed and cultured in DMEM containing 10% fetal bovine serum for 48 h after the last transduction before use for further experimentation. Successful transduction was evident from reporter gene expression in the Ad-netrin transduced Sca-1+ cells [(NetSca-1+); green fluorescence] and Ad-null transduced Sca-1+ cells [(NullSca-1+); red fluorescence] 48 h after the final transduction with their respective viral vectors. Netrin-1 transgene expression in NetSca-1+ was confirmed by reverse transcription–polymerase chain reaction (RT-PCR) and western blot.

Reverse transcription–polymerase chain reaction

Isolation of total RNA from different treatment groups of the cells and subsequent first-strand cDNA synthesis was performed on different samples using an RNeasy mini kit (Qiagen) and an Omni script Reverse Transcription kit (Qiagen), respectively, as per the manufacturer's instructions. Nucleotide sequence of primers used for PCR analysis included Unc5b (173 bp) for 5′- cggaaggttccc agacagta; rev 5′-tccaaagtcaccacctcctc; Netrin-1 (198 bp) for 5′-tactgcaaggcttcc aaagg; rev 5′—aacggatccacaaactctgg; Nos2 (443 bp) for 5′-aataacctgaagcccgagaccca; rev 5′-ttcaaagtggtagccacatcccga; Nos3 (210 bp) for 5′-tgaccctcaccgatacaaca; rev 5′-ctggccttctgctc attttc; Actin (228 bp) for 5′-agccatgtacgtagccatcc; and rev 5′-ctctcagctgtggtggtgaa. The thermocycle profile for RT-PCR was set at initial denaturation at 94°C for 1 min and annealing/extension at 55°C for 4 min, repeated twice; 30 cycles of denaturation at 94°C for 1 min and annealing/extension at 55°C for 2 min; and a final extension at 70°C for 10 min.

Western blotting

Western blotting was performed as described earlier [10]. Briefly, NetSca-1+, NullSca-1+ and nontransduced Sca-1+ cells (NatSca-1+) were lysed in the cell lysis buffer containing 50 mM 4-(2-hydroxyethyl)-1-piperazineethanesulfonic acid, 5 mM EDTA, 50 mM NaCl at pH 7.4 and substituted with 1% Triton X-100, protease inhibitors (10 μg/mL aprotinin, 1 mM phenylmethyl sulfonyl fluoride, and 10 μL/mL of leupeptin), and phosphatase inhibitors (50 mM sodium fluoride, 1 mM sodium orthovanadate, and 10 mM sodium pyrophosphate). The cell lysate samples were centrifuged at 14,000 rpm for 20 min at 4°C to remove cell debris, and protein concentration in the supernatant was measured using the Bio-Rad DC Protein Assay (BioRad Lab) using a spectrophotometer (Molecular Devices Spectra Max). The cell lysate samples (50 μg) were electrophoresed using 4–12% precast sodium dodecyl sufate-polyacrylamide gel (Invitrogen) and transferred on to Immunoblot polyvinylidene fluoride (PVDF) membrane (BioRad Lab). The membrane was blocked with 5% nonfat dried milk in TBST (20 mM Tris/HCl pH 7.5, 150 mM NaCl, and 0.2% Tween-20) for 1 h at room temperature with gentle agitation. The membrane was incubated overnight at 4°C with relevant primary antibody; rabbit anti total-Akt (Cell Signaling Tech; cat#9272; 1:1,000); rabbit anti phospho-Akt (p-Akt; Ser473) (Cell Signaling Tech; cat#9272; 1:1,000); and goat antiactin (Santa Cruz Biotechnology; cat# sc1616; 1:10,000). The membrane was washed ×4 and incubated with their respective IgG horse raddish peroxidase-conjugated secondary antibody (1:2,000) for 1 h at room temperature. Finally, the membrane was incubated in sufficient SuperSignal West Femto Maximum Sensitivity Substrate (Pierce) and exposed to Kodak Scientific Imaging Film for detection of the signals.

Tube formation assay

Matrigel (70 μL, BD-Pharmingen) was coated in a 96-well plate and incubated at 37°C for 30 min before adding 25×103 human umbilical vein endothelial cells (HUVECs) per well in serum-free media. After 45 min at 37°C and 5% CO2, serum-free media were removed and replaced with conditioned media from NatSca-1+ (NatCM), NullSca-1+ (NullCM), and NetSca-1+ cells (NetCM). Tube formation was assessed at 4 h after their respective treatment in triplicate. Phase-contrast photomicrographs of representative fields were taken at 200× magnification and counted for branch points per microscopic field. vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) treated cells were used as a positive control.

Cell migration assay

We investigated the ability of HUVECs and rat endothelial cells to migrate toward NullCM and NetCM using a Transwell system (Corning Scientific Products) as described earlier [8].

Cell survival and the downstream signaling pathway in netrin-1 treated cells

The cells were seeded in 10 cm dishes 24 h before experiments at 80% confluence and were subsequently starved for 18 h. Subsequently, the cells were treated with recombinant netrin-1 (100 ng/mL) for 1 h either with or without previous treatment with 50 μL/mL Wortmanin for 1 h. The cells without any treatment were used as a control. Subsequently, the cells from various treatments were harvested and used for western blot studies to determine Akt phosphorylation and downstream signaling and their effects on netrin-1 treatment. The pro-survival effects of netrin-1 treatment were assessed by lactate dehydrogenase (LDH) release assay using Homogeneous Membrane Integrity Assay kit (Promega) and terminal deoxynucleotidyl transferase dUTP nick end labeling (TUNEL) assay with in situ cell death kit, TMR Red (Roche Applied Science).

In vivo studies

Experimental animal model and cell engraftment

The current study conformed to the Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals published by the US National Institutes of Health (NIH Publication No. 85-23, revised 1985) and protocol approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee, University of Cincinnati. An experimental animal model of ischemia-reperfusion injury was developed in young female Wistar rats each weighing (180–200 g) as previously described [11]. After tracheal intubation and ventilation using Harvard Rodent Ventilator (Model-683), the hearts were exposed by minimal left-sided thoracotomy. After the heart had been exposed, a Prolene #6–0 suture was passed around the left anterior descending coronary artery left anterior descending (LAD) 2–3 mm distal to its origin. Experimental ischemia-reperfusion injury was incurred by ligation of the LAD for 45 min, after which the snare was released for reperfusion. The animals were grouped to receive 70 μL of DMEM (group-1), containing 2×106 NullSca-1+ cells (group-2) and NetSca-1+ cells (group-3). These cells were fluorescently labeled with either PKH26 (group-2) or PKH67 (group-3) cell tracker dyes to determine the fate of cells postengraftment in the infarcted heart. The cells were intramyocardially injected at multiple sites (4 sites/heart on average) in the center and border zone of the infarct by using a 27G needle. The chest of the animals was closed, and the animals were allowed to recover. The animals were maintained on Buprinex after surgery for 24 h. The animals were euthanized at stipulated time points (n=2 per group on day 4 and n=8 per group at 6 weeks) for histological and molecular studies. For assessment of the heart function, transthoracic echocardiography was performed 6 weeks after cell engraftment before euthanasia.

Nitric oxide assay

Nitric oxide (NO) activity was determined in the Ad-netrin-1 and Ad-null treated animal hearts using Ultrasensitive Colorimetric NO assay kit (Oxford Biomedical Research) according to manufacturer's instructions. One hundred micrograms of the left ventricle tissue homogenate samples were used from each animal heart tissue for the assay.

The heart function studies

Transthoracic echocardiography was performed to assess global heart function before surgery (baseline), and 6 weeks after surgery using Echocardiography system HDI/5,000 SONOS CT (HP-Company). All hearts were imaged in 2D and M-mode from parasternal long axis view, and all measurements were obtained at the level of the largest left ventricular diameter as described earlier [9]. Indices of left ventricle (LV) systolic function including LV fractional shortening (LVFS) and LV ejection fraction (LVEF) were calculated using LVFS=(LVEDD−LVESD)/LVEDD ×100 and LVEF=[(LVEDD3−LVESD3)/LVEDD3]×100 relations respectively, and the results were expressed as percentage.

Histological studies

For measurement of infarction size and area of fibrosis, the hearts were arrested in diastole by intravenous injection of cadmium chloride and fixed in 10% buffered formalin. The hearts were then excised, cut transversely, and embedded in paraffin. Histological sections of 6 μm in thickness were cut and used for hematoxylin-eosin and Masson's trichrome staining for visualization of muscle architecture and area of fibrosis [11]. Infarct size was defined as sum of the epicardial and endocardial infarct circumference divided by sum of the total LV epicardial and endocardial circumferences using computer-based planimetry with Image-J analysis software (version 1.6065; NIH).

Blood vessel density was assessed as previously described [8]. Briefly, cryosections (6 μm thick) were immunostained using vonWillebrand Factor-VIII (vWF) specific primary antibody (1:100; Dako) and detected with fluorescently labeled secondary antibody (Invitrogen). The number of blood vessels positive for vWF-VIII were counted in both infarct and peri-infarct regions that were randomly selected and counted in different treatment group. Blood vessel density was expressed as the number of vessels per microscopic surface area (0.74 mm2) at 400× magnification. Blood vessel diameter was calculated by measuring the circumference of the blood vessels.

Statistical analysis

All data were described as mean±standard error of means. To analyze the data statistically, we performed Student's t-test and one-way analysis of variance with suitable post hoc analysis, and a value of P<0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

Construction of Ad-vector and isolation of Sca-1+ cells

Ad-netrin and Ad-Null were successfully constructed and used for transduction of the cells (Fig. 1A). We observed that UNC5b was expressed on Sca-1+ cells that remained unaltered during transduction of the cells with Ad-null and Ad-netrin-1 vectors besides its expression in the cardiomyocytes, endothelial cells, and HUVEC. The heart tissue was used as a positive control (Fig. 1B).

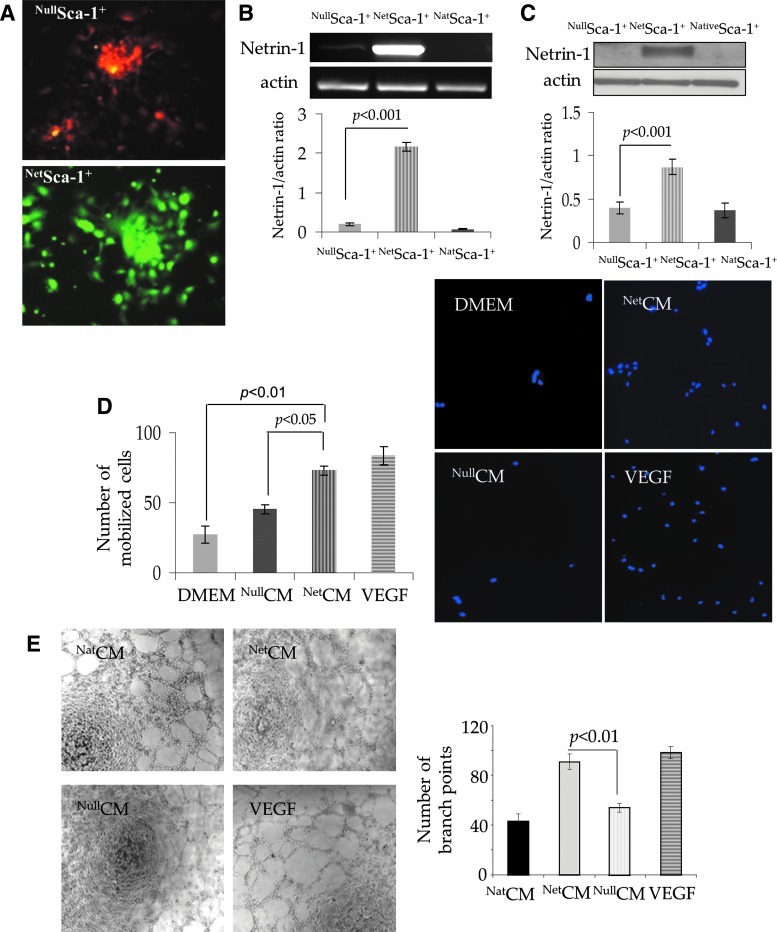

Transgenic overexpression of netrin-1

We successfully transduced the cells for netrin-1 transgene overexpression using our optimized transduction protocol, which was evident from RFP (red fluorescence) and GFP (green fluorescence) expression in NullSca-1+ and NetSca-1+ cells respectively (Fig. 2A). Netrin-1 transgene expression was 200-fold higher in NetSca-1+ cells as compared with NullSca-1+ cells and untreated Sca-1 (NativeSca-1+) cells (Fig. 2B). Western blotting of cell lysate showed significant increase in netrin-1 protein expression in NetSca-1+ cells as compared with NullSca-1+ cells and NativeSca-1+ cells controls (P<0.01, Fig. 2C). We investigated the ability of rat endothelial cells to migrate in response to NullCM and NetCM in a Transwell invasion assay system (Fig. 2D). Although poor migration of rat endothelial cells was observed in response to NullCM, cell migration was higher in response to NetCM (P<0.05 vs. NullCM). Basal DMEM and VEGF were used as negative and positive controls, respectively. In vitro angiogenic potential of NetCM was determined by tube formation assay on matrigel, which showed a significantly higher number of branch points per microscopic field (200×) as compared with NullCM. VEGF treated cells were used as a positive control (Fig. 2E).

FIG. 2.

In vitro characterization of NetSca-1+-like cells. (A) Fluorescence microscopic images of Sca-1+ cells successfully transduced with Ad-null (red) and Ad-netrin (green) 48 h after transduction with the respective viral vector. Overexpression of netrin-1 transgene was confirmed by (B) RT-PCR. (C) Western blot showed significantly higher netrin-1 protein expression in NetSca-1+ cells as compared with NullSca-1+ and NatSca-1+ cells. (D) Transwell migration of rat endothelial cells (DAPI labeled; blue fluorescence) in response to conditioned medium from NetSca-1+ (NetCM) was significantly higher as compared with the conditioned medium obtained from NullSca-1+ cells (NullCM) and basal DMEM, using VEGF as a positive control. (E) Tube formation assay on matrigel using HUVECs treated with NetCM showed significantly higher number of branch points per microscopic field (200×) as compared with NativeCM and NullCM controls (P<0.01 vs. controls). VEGF treated cells were used as positive control. HUVECs, human umbilical vein endothelial cells; DMEM, Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium. Color images available online at www.liebertpub.com/scd

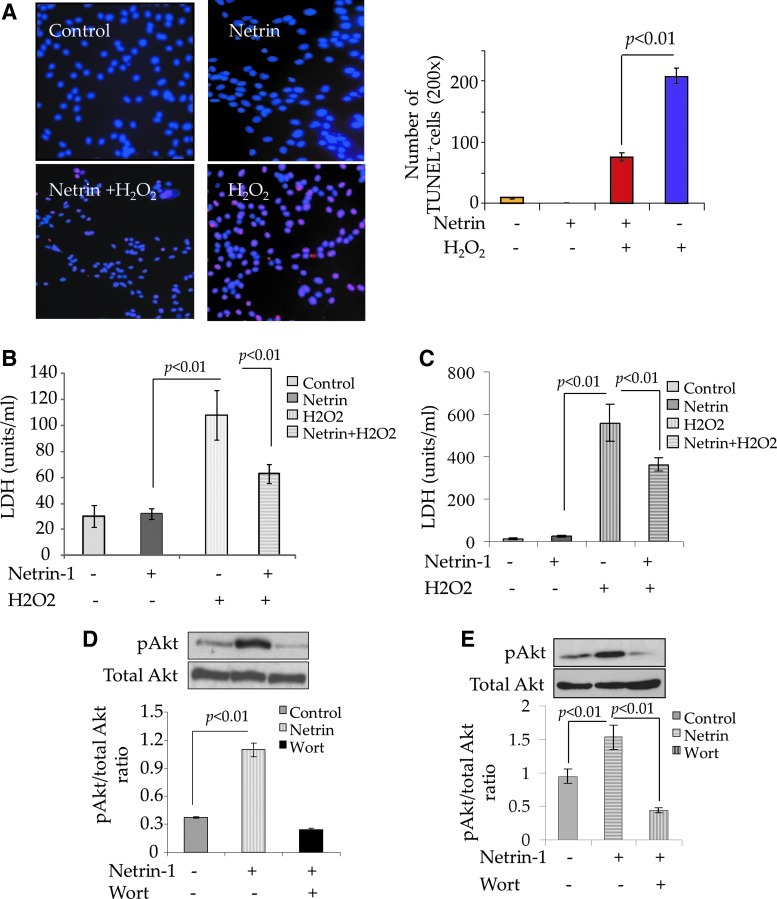

Cytoprotective effects of netrin-1 on rat endothelial cells and cardiomyocytes

In order to assess the cytoprotective effects of netrin-1 on rat neonatal cardiomyocytes and endothelial cells, the cells were treated with recombinant netrin-1 (100 ng/mL) separately in a parallel set of experiments (Fig. 3). Such treatment was without any cytotoxic effects on the cells; however, our data showed significantly enhanced survival of neonatal cardiomyocytes (Fig. 3A, B). TUNEL staining showed increased number of TUNEL+ cardiomyocytes exposed to 100 μM H2O2 for 4 h without netrin-1 pretreatment as compared with netrin-1 pretreated cells (Fig. 3A, P<0.01). These results were confirmed by measuring release of LDH as a marker of cellular injury, which was significantly reduced in the cells pretreated with netrin-1 as compared with the cells without pretreatment with netrin-1 (Fig. 3B, P<0.01). Similar observations were also made with rat endothelial cells when netrin-1 pretreatment significantly protected the cells against oxidant stress (Fig. 3C). Western blot studies showed higher phosphorylation of Akt in both cardiomyocytes (Fig. 3D) and rat endothelial cells (Fig. 3E) treated with recombinant netrin-1, which was abrogated by pretreatment of the cells with 40 μM wortmannin.

FIG. 3.

Netrin-1 is cytoprotective for cardiomyocytes and endothelial cells. (A) TUNEL staining and (B) LDH release from the cardiomyocytes treated with 100 μM H2O2 for 4 h. The number of TUNEL+ cells (A; red fluorescence) and release of LDH were significantly reduced in the cardiomyocytes pretreated with 100 ng/mL recombinant netrin-1 as compared with the cardiomyocytes without netrin-1 pretreatment (P<0.01 vs. cardiomyocytes without netrin-1 treatment) after exposure to 100 μM H2O2. Netrin-1 treatment alone was well tolerated by the cells without any cytotoxicity as indicated by insignificantly lower TUNEL positivity and LDH release. (C) LDH release assay on rat endothelial cells treated with 100 μM H2O2 for 4 h. LDH release was significantly reduced in rat endothelial cells pretreated with 100 ng/mL recombinant netrin-1 as compared with the rat endothelial cells without netrin-1 pretreatment (P<0.01 vs. endothelial cells without netrin-1 pretreatment). Netrin-1 treatment alone was well tolerated by the cells without any cytotoxicity as indicated by insignificantly lower LDH release. (D, E) Western blot showed significantly higher phosphorylation of Akt in netrin-1 treated (D) cardiomyocytes and (E) rat endothelial cells as compared with the respective native cells without netrin-1 treatment. Phosphorylation of Akt was abrogated by pretreatment of both cardiomyocytes and rat endothelial cells with 40 μM wortmannin. LDH, lactate dehydrogenase. Color images available online at www.liebertpub.com/scd

In vivo studies in experimental animal model

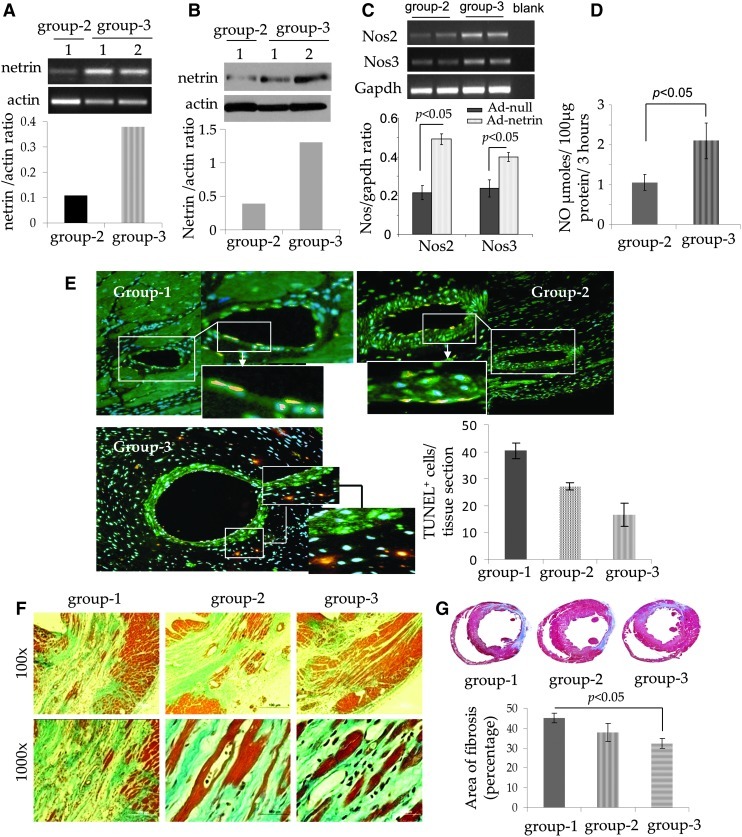

All animals after their respective treatment in different groups survived the full length of the experiment, and there were no animal deaths related with ex vivo netrin-1 transgene overexpression in the infarcted heart. Analysis of the LV tissue samples by quantitative (q)RT-PCR showed that the transplanted cells continued to overexpress netrin-1 at the site of the cell graft in the animal hearts. The level of netrin-1 transgene expression on day 4 was elevated in group-3 as compared with group 2 (Fig. 4A, P<0.01 vs. NullSca-1+ group-2). These results were confirmed by western blot studies for netrin-1 protein expression (Fig. 4B, P<0.01 vs. group-2). qRT-PCR showed significant expression of Nos2 and Nos3 in NetSca-1+ transplanted group-3 animal hearts (P<0.05 vs. NullSca-1+ transplanted hearts, Fig. 4C). On the same note, NOS activity was also significantly increased in NetSca-1+ transplanted group-3 animal hearts (Fig. 4D). A significantly higher number of TUNEL+ endothelial cells were observed in group-1 and group-2 animal hearts as compared with NetSca-1+ cell treated group-3 animal hearts (Fig. 4E).

FIG. 4.

Cardioprotective effects of transgenic netrin-1 expression. (A, B) quantitative (q)RT-PCR and western blot studies showing significantly higher expression of netrin-1 transgene in the left ventricle on day 4 after transplantation of NetSca-1+ (P<0.05 vs. NullSca-1+ injected control animal hearts). (C) qRT-PCR for Nos2 and Nos3 expression in the experimental animal hearts on day 4 after transplantation of NullSca-1+ cells (group-2) and NetSca-1+ cells (group-3). (D) Nitric oxide assay showing significantly higher Nos activity in NetSca-1+ transplanted animal hearts on day 4 after treatment (P<0.05 vs. NullSca-1+ transplanted group-2). (E) TUNEL on histological sections from different treatment groups of animals (red) counter stained for immmunodetection of the muscle architecture using cardiac actin (green). DAPI was used to visualize the nuclei. The number of TUNEL+ endothelial cells was significantly higher in groups 1 and 2 as compared with group 3. (F, G) Mason trichrome staining of the rat heart tissue samples from the three animal groups after 6 weeks of their respective treatment. Myocardial protection was markedly improved in the heart tissues in group-3 NetSca-1+ cell transplanted animal hearts as compared with NullSca-1+ transplanted animal group 2 and DMEM injected group-1 animal hearts.

Histological studies at 6 weeks showed extensive myocardial injury that was typically characterized by loss of myocardial architecture (Fig. 4F, G). Mason's trichrome staining of the histological sections, cut at the level of papillary muscle, from three different treatment groups of animals showed that the injured myocardium was replaced by granulation tissue (Fig. 4F, G). However, marked preservation of myocardial tissue was observed in NetSca-1+ cells treated group-3 animal hearts as indicated by the presence of islands of healthy myocardium, stained positively for eosin, interspersed in the granular tissue. The presence of eosin positive myofibers indicative of living residual/newly generated myocardium was apparently marked in the netrin-1 treated group-3 animal hearts as compared with NullSca-1+ cells group 2 and DMEM without cells treated group-1 animals (Fig. 4F). Percent area of fibrosis was significantly reduced in group 3 (32.3±2.4) as compared with group 1 (45.1±2.5; P<0.05 vs. group-3) and group 2 (37.8±4.4; P<0.05 vs. group 3, Fig. 4G).

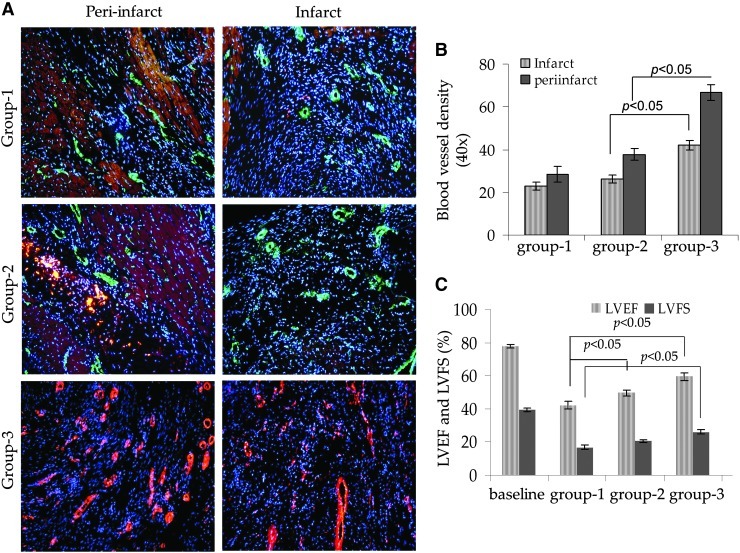

Histological sections immunostained for vonWillebrand Factor-Vlll antigen showed that blood vessel density was significantly increased in group-3 animal hearts. We observed a clear intra-group and inter-group difference between the blood vessel density observed in the infarct and per-infarct regions (Fig. 5A, B). The blood vessel density in group 3 in the peri-infarct region (66±4) was higher as compared with the infarct area (42±3; P<0.01 vs. peri-infarct region). Similarly, group 3 had the highest blood vessel density in both infarct and peri-infarct areas as compared with group 2 (38±3 and 26±4; P<0.05) and group 1 (28±4 and 23±3; P<0.05), respectively (Fig. 5A, B).

FIG. 5.

(A) Fluorescence immunostaining of the rat heart tissue sections from different treatment groups of animals for expression of vonWillebrand Factor-VIII for blood vessel density determination. (B) Blood vessel density was significantly higher in group-3 animal hearts in both infarct and peri-infarct regions as compared with groups 1 and 2. (C) Transthoracic echocardiography was performed to assess global heart function. Both LV ejection fraction and fractional shortening were significantly preserved in groups 2 and 3 as compared with group-1. LV, left ventricle; vWF, vonWillebrand Factor.

Heart function studies

Transthoracic echocardiography showed that indices of LV contractile function were significantly preserved in NetSca-1+ transplanted group 3 (Fig. 5C). The baseline values of LVEF and LVFS were 77.68±1.2 and 39.5±1.1, respectively, in the normal animals without surgery. The LV function indices were significantly more preserved in NetSca-1+ transplanted group 3 (59.3±2.1 and 26.2±1.3) as compared with NullSca-1+ transplanted group 2 (49.7±2 and 20.5±1.3; P<0.05 vs. group 3) and DMEM injected group-1 animals (42.06±2.5 and 16.83±1.1; P<0.05 vs. group 3) (Fig. 5C).

Discussion

The complex cascade of angiogenesis involves vascular endothelial cell differentiation, proliferation, migration, and maturation, influenced by a delicate balance and an intricate interaction between multiple pro- and anti-angiogenic factors [12]. Among these factors, VEGF, angiopoietins, PDGF, and fibroblast growth factor families of growth factors have been extensively studied for their participation in angiogenesis [13]. More so, the safety and effectiveness of some of these growth factors have already been assessed in various clinical studies with limited success [14]. Nevertheless, due to the therapeutic significance of angiogenic response either alone or in combination with stem cell therapy [9,15–17], pursuit for novel biomolecules with better angiogenic activity and higher safety index is continuing. Given that both neuronal and vascular systems are superimposed in the biological system and their development requires guidance to establish a precise branching pattern, it is generally considered that their development may share some common guidance mechanism [18,19]. Netrin-1 in this regard is being assessed for its role as an endothelial cell and vascular smooth muscle cell mitogen besides its well-established position as a bifunctional axon guidance cue, as it is capable of attracting or repelling the developing axons via interaction with its receptors of DCC and Uncb5 families [20]. Netrin-1 has structural homology with the endothelial cell mitogens and with an emerging role of netrin-1 in angiogenesis, the current study was designed to show that ex-vivo transgenic overexpression of netrin-1 in the ischemic myocardium may be a safer and an effective option for biological bypass by development of new vascular structures. The important findings of our study were (1) Unc5b receptor was highly expressed in the heart, the cardiomyocytes, and endothelial cells. (2) Netrin-1 transgene overexpression was cytoprotective for the cardiomyocytes and endothelial cells and supported the endothelial cell migration. (3) Cell-based transgenic overexpression of netrin-1 attenuated infarct size expansion and promoted angiogenesis in the infarcted heart with concomitant preservation of heart function indices.

Netrin-1 and its receptors DCC, Unc5b and A2B adenosine receptor, exhibit a discrete pattern of distribution in the biological system, and the biological functions of netrin-1 vary with their localization [21]. Endogenous netrin-1 is released from the floor plate cells at the ventral midline of the embryonic neural tube during embryonic development of the nervous system [22]. With identification of the newer roles for netrin-1 other than its involvement in nervous system development, research is currently focused on understanding the mechanism of netrin-1 induction. More recent studies have reported the critical role of hypoxia inducible factor-1α (Hif-1α) in regulating endogenous netrin-1 expression [23]. Transcription factor Hif-1α is translocated into the cell nuclei in response to tissue hypoxia where it regulates expression of a plethora of genes that help cellular and tissue responses to low oxygen presence to maintain oxygen homeostasis in the biological system [24–26]. Netrin-1 is one of these genes, the expression of which is significantly enhanced in response to tissue hypoxia in Hif-1α dependent fashion and that attenuates a hypoxia-induced inflammatory response [23]. Interaction between secretable netrin-1 and its trans-membrane receptor Unc5b critically participates in multiple cell functions including axonal guidance, angiogenesis, proliferation, and apoptosis [22,27]. More recent studies have defined a critical role for interaction between Unc5 and netrin during cardiac tubulogenesis in Drosophila melanogaster, whereas loss of either Unc5 or netrin blocks heart lumen formation [28]. On the same note, netrin-1 has cardioprotective role via activation of NO production in the ischemic myocardium in a DCC-Erk1/2 dependent fashion [29]. Interaction of netrin-1 with A2B adenosine receptor has been shown to induce cAMP accumulation and mediate axon outgrowth [30]. Given the broad distribution and predominant expression of A2B adenosine receptor on the cells involved in inflammatory response in the biological system [31], recent studies have reported that netrin-1 interaction with A2B adenosine receptors is protective and prevents leukocyte tissue infiltration and recruitment during acute inflammation [32].

Although various groups have reported angiogenic activity of netrin-1 in vitro, there are very few reports that have shown angiogenic activity of netrin-1 either alone or in combination with stem cell transplantation in experimental animal models. In a recent report, transplantation of MSCs with recombinant netrin-1 augmented blood vessel density and angiogenic score in a rat model of hind limb ischemia [3]. Concomitant administration of netrin-1 with MSC transplantation regulated VEGF expression in MSCs, which remained significantly elevated for 28 days of observation in the netrin-1/MSC treated animals as compared with the controls. Similarly, delivery of recombinant netrin-1 in the infarcted heart stimulated NO production via a DCC-ERK1/2 dependent mechanism and prevented cardiomyocyte apoptosis besides increasing blood vessel density in the infarcted heart. We have already shown that activation of sonic hedgehog signaling in the ischemic heart enhanced netrin-1 expression with a resultant increase in functional blood vessel formation [8]. Intramyocardial delivery of recombinant netrin-1 protein to the ischemic myocardium elicited a potent angiogenic response in the ischemic heart [8]. Our current study exploits netrin-1 transgene overexpression for preservation of ischemic heart function. The transplanted cells served as a reservoir of netrin-1 release that acted in paracrine fashion for cardioprotection and significantly enhanced myocardial blood vessel density in the netrin-1 expressing cell transplanted region. These data were supported by in vitro experiments which showed that netrin-1 treatment of cardiomyocytes and endothelial cells, two of the main constituent cell types in the myocardium, protected these cells from ischemic injury subsequent to restoration of coronary blood flow in the ischemic heart. In vivo data were in agreement with the in vitro results showing extensive emigrational activity of endothelial cells in response to conditioned medium obtained from the cells with netrin-1 overexpression.

Despite these interesting data, there are some limitations of this study. It would be interesting to determine the anti-inflammatory effects of netrin-1 transgene overexpression on the infarcted heart in comparison with the infarcted animal hearts without netrin-1 treatment. Second, in-depth genetic studies would be required to show that the therapeutic effects observed during ex-vivo overexpression of netrin-1 in the infarcted heart were mediated via netrin-1/UNC5b ligand/receptor interaction. In conclusion, our data clearly supported the importance of netrin-1 in angiogenesis, and prevention of apoptosis induced cell death in the ischemic myocardium.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by National Institutes of Health Grants# R37HL074272; HL-080686; HL-087246 (M.A) and HL-087288; HL-089535; HL106190-01 (Kh.H.H).

Author Disclosure Statement

The authors declare that they have nothing to disclose.

References

- 1.Baioni L. Basini G. Bussolati S. Cortimiglia C. Grasselli F. Netrin-1: just an axon-guidance factor? Vet Res Commun. 2010;34(Suppl 1):S1–S4. doi: 10.1007/s11259-010-9366-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Nguyen A. Cai H. Netrin-1 induces angiogenesis via a DCC-dependent ERK1/2-eNOS feed-forward mechanism. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2006;103:6530–6535. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0511011103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Li Q. Yao D. Ma J. Zhu J. Xu X. Ren Y. Ding X. Mao X. Transplantation of MSCs in Combination with Netrin-1 Improves Neoangiogenesis in a Rat Model of Hind Limb Ischemia. J Surg Res. 2009;166:162–169. doi: 10.1016/j.jss.2009.08.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Castets M. Mehlen P. Netrin-1 role in angiogenesis: to be or not to be a pro-angiogenic factor? Cell Cycle. 2010;9:1466–1471. doi: 10.4161/cc.9.8.11197. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Castets M. Coissieux MM. Delloye-Bourgeois C. Bernard L. Delcros JG. Bernet A. Laudet V. Mehlen P. Inhibition of endothelial cell apoptosis by netrin-1 during angiogenesis. Dev Cell. 2009;16:614–620. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2009.02.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Freitas C. Larrivee B. Eichmann A. Netrins and UNC5 receptors in angiogenesis. Angiogenesis. 2008;11:23–29. doi: 10.1007/s10456-008-9096-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bradford D. Cole SJ. Cooper HM. Netrin-1: diversity in development. Int J Biochem Cell Biol. 2009;41:487–493. doi: 10.1016/j.biocel.2008.03.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ahmed RP. Haider KH. Shujia J. Afzal MR. Ashraf M. Sonic Hedgehog gene delivery to the rodent heart promotes angiogenesis via iNOS/netrin-1/PKC pathway. PLoS One. 2010;5:e8576. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0008576. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Jiang S. Haider KH. Idris NM. Salim A. Ashraf M. Supportive interaction between cell survival signaling and angiocompetent factors enhances donor cell survival and promotes angiomyogenesis for cardiac repair. Circ Res. 2006;99:776–784. doi: 10.1161/01.RES.0000244687.97719.4f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Niagara MI. Haider KH. Jiang S. Ashraf M M. Pharmacologically preconditioned skeletal myoblasts are resistant to oxidative stress and promote angiomyogenesis via release of paracrine factors in the infarcted heart. Circ Res. 2007;100:545–555. doi: 10.1161/01.RES.0000258460.41160.ef. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Okumura H. Nagaya N. Itoh T. Okano I. Hino J. Mori K. Tsukamoto Y. Ishibashi-Ueda H. Miwa S. Tambara K. Adrenomedullin infusion attenuates myocardial ischemia/reperfusion injury through the phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase/Akt-dependent pathway. Circulation. 2004;109:242–248. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.0000109214.30211.7C. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Rosinberg A. Khan TA. Sellke FW. Laham RJ. Therapeutic angiogenesis for myocardial ischemia. Expert Rev Cardiovasc Ther. 2004;2:271–283. doi: 10.1586/14779072.2.2.271. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Sodha NR. Chu LM. Boodhwani M. Sellke FW. Pharmacotherapy for end-stage coronary artery disease. Expert Opin Pharmacother. 2010;11:207–213. doi: 10.1517/14656560903439737. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Atluri P. Woo YJ. Pro-angiogenic cytokines as cardiovascular therapeutics: assessing the potential. BioDrugs. 2008;22:209–222. doi: 10.2165/00063030-200822040-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ye L. Haider KH. Tan R. Toh W. Law PK. Tan W. Su L. Zhang W. Ge R, et al. Transplantation of nanoparticle transfected skeletal myoblasts overexpressing vascular endothelial growth factor-165 for cardiac repair. Circulation. 2007;116(11 Suppl):I113–I120. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.106.680124. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Yau TM. Kim C. Li G. Zhang Y. Fazel S. Spiegelstein D. Weisel RD. Li RK. Enhanced angiogenesis with multimodal cell-based gene therapy. Ann Thorac Surg. 2007;83:1110–1119. doi: 10.1016/j.athoracsur.2006.10.050. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ye L. Zhang W. Su LP. Haider HK. Poh KK. Galupo MJ. Songco G. Ge RW. Tan HC. Sim EK. Nanoparticle based delivery of hypoxia-regulated VEGF transgene system combined with myoblast engraftment for myocardial repair. Biomaterials. 2011;32:2424–2431. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2010.12.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Park KW. Crouse D. Lee M. Karnik SK. Sorensen LK. Murphy KJ. Kuo CJ. Li DY. The axonal attractant Netrin-1 is an angiogenic factor. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2004;101:16210–16215. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0405984101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Larrivee B. Freitas C. Suchting S. Brunet I. Eichmann A. Guidance of vascular development: lessons from the nervous system. Circ Res. 2009;104:428–441. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.108.188144. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Larrivee B. Freitas C. Trombe M. Lv X. Delafarge B. Yuan L. Bouvree K. Breant C. Del Toro R. Brechot N. Activation of the UNC5B receptor by Netrin-1 inhibits sprouting angiogenesis. Genes Dev. 2007;21:2433–2447. doi: 10.1101/gad.437807. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Dakouane-Giudicelli M. Duboucher C. Fortemps J. Missey-Kolb H. Brule D. Giudicelli Y. de Mazancourt P. Characterization and expression of netrin-1 and its receptors UNC5B and DCC in human placenta. J Histochem Cytochem. 2010;58:73–82. doi: 10.1369/jhc.2009.953463. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Moore SW. Tessier-Lavigne M. Kennedy TE. Netrins and their receptors. Adv Exp Med Biol. 2007;621:17–31. doi: 10.1007/978-0-387-76715-4_2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Rosenberger P. Schwab JM. Mirakaj V. Masekowsky E. Mager A. Morote-Garcia JC. Unertl K. Eltzschig HK. Hypoxia-inducible factor-dependent induction of netrin-1 dampens inflammation caused by hypoxia. Nat Immunol. 2009;10:195–202. doi: 10.1038/ni.1683. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Eltzschig HK. Carmeliet P. Hypoxia and inflammation. N Engl J Med. 2011;364:656–665. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra0910283. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Semenza GL. Oxygen homeostasis. Wiley Interdiscip Rev Syst Biol Med. 2011;2:336–361. doi: 10.1002/wsbm.69. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Eckle T. Kohler D. Lehmann R. El Kasmi K. Eltzschig HK. Hypoxia-inducible factor-1 is central to cardioprotection: a new paradigm for ischemic preconditioning. Circulation. 2008;118:166–175. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.107.758516. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Wang W. Reeves WB. Ramesh G. Netrin-1 increases proliferation and migration of renal proximal tubular epithelial cells via the UNC5B receptor. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol. 2009;296:F723–F729. doi: 10.1152/ajprenal.90686.2008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Albrecht S. Altenhein B. Paululat A. The transmembrane receptor Uncoordinated5 (Unc5) is essential for heart lumen formation in Drosophila melanogaster. Dev Biol. 2011;350:89–100. doi: 10.1016/j.ydbio.2010.11.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Zhang J. Cai H. Netrin-1 prevents ischemia/reperfusion-induced myocardial infarction via a DCC/ERK1/2/eNOS s1177/NO/DCC feed-forward mechanism. J Mol Cell Cardiol. 2010;48:1060–1070. doi: 10.1016/j.yjmcc.2009.11.020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Corset V. Nguyen-Ba-Charvet KT. Forcet C. Moyse E. Chedotal A. Mehlen P. Netrin-1-mediated axon outgrowth and cAMP production requires interaction with adenosine A2b receptor. Nature. 2000;407:747–750. doi: 10.1038/35037600. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Hasko G. Pacher P. A2A receptors in inflammation and injury: lessons learned from transgenic animals. J Leukoc Biol. 2008;83:447–455. doi: 10.1189/jlb.0607359. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Aherne CM. Collins CB. Masterson JC. Tizzano M. Boyle TA. Westrich JA. Parnes JA. Furuta GT. Rivera-Nieves J. Eltzschig HK. Neuronal guidance molecule netrin-1 attenuates inflammatory cell trafficking during acute experimental colitis. Gut. 2011 doi: 10.1136/gutjnl-2011-300012. [Epub ahead of print]; [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]