Abstract

Cone photoreceptors in fish are typically arranged into a precise, reiterated pattern known as a ‘cone mosaic’. Cone mosaic patterns can vary in different fish species and in response to changes in habitat, yet their function and the mechanisms of their development remain speculative. Zebrafish (Danio rerio) have four cone subtypes arranged into precise rows in the adult retina. Here we describe larval zebrafish cone patterns and investigate a previously unrecognized transition between larval and adult cone mosaic patterns. Cone positions were determined in transgenic zebrafish, expressing green fluorescent protein (GFP) in their UV-sensitive cones, by the use of multiplex in situ hybridization labelling of various cone opsins. We developed a ‘mosaic metric’ statistical tool to measure local cone order. We found that ratios of the various cone subtypes in larval and adult zebrafish were statistically different. The cone photoreceptors in larvae form a regular heterotypic mosaic array, i.e. the position of any one cone spectral subtype relative to the other cone subtypes is statistically different from random. However, the cone spectral subtypes in larval zebrafish are not arranged in continuous rows as in the adult. We used cell birthdating to show that the larval cone mosaic pattern remains relatively disorganized, or perhaps is somewhat remodeled, within the adult retina. The abundance of cone subtypes relative to other subtypes is different in this larval remnant compared to that of larvae or canonical adult zebrafish retina. These observations provide baseline data for understanding the development of cone mosaics via comparative analysis of larval and adult cone development in a model species.

Keywords: heterotypic cell mosaic, row mosaic, metamorphosis, opsin, multiplex in situ hybridization, teleost

INTRODUCTION

Homotypic mosaics of cells, in which the spatial arrangement of cells of a given type is regular, are common. Examples include the equal spacing of bird feathers on the skin and the distribution of photoreceptors and other types of neurons in the retina (Cameron and Carney, 2004; Eglen et al., 2003; Reese et al., 2005; Tyler and Cameron, 2007). Heterotypic arrangements of cells, in which different cell types are arranged in a pattern relative to each other that is statistically different from random ( e.g. , different types of photoreceptors within fly ommatidia), are not as readily observable in vertebrates (Eglen and Wong, 2008). Arguably, the importance of spatial relationships amongst heterotypic cell types in the vertebrate central nervous system has been underappreciated: likely roles include both proper neuron differentiation and functional connectivity (Eglen and Galli-Reta, 2006; Eglen et al., 2008; Fuerst et al., 2008). The cone photoreceptor mosaics in teleost fish represent a uniquely accessible example of vertebrate heterotypic neuronal mosaics.

Cone photoreceptors in teleost fish are similar to those of other vertebrates, with multiple subtypes varying in their spectral sensitivity due to differential expression of opsin genes. The differing spectral sensitivities of individual cones underpins colour vision (Risner et al., 2006). One of the striking features of teleost cone photoreceptors that differentiates them from those of other vertebrates is their spatial arrangement into regular, heterotypic mosaics: reiterated patterns of cone spectral subtypes precisely arranged relative to one another across the retina. The only other group of vertebrates that is thought to have a heterotypic mosaic are some diurnal geckos which display regular patterns of photoreceptors at least at the mmorphological level (Dunn 1966; Cook and Noden 1998). Different teleost species have variations on this mosaic pattern (Ali and Antcil, 1976; Collin, 2008; Collin and Shand, 2003), generally categorized as row and square mosaics, in which double and single cone photoreceptors are arranged in parallel rows or in a lattice arrangement of squares, respectively. Some species appear to transition between row and square mosaics during ontogenies (Lyall; shand et al 1999), and several other variations on the mosaic geometry have been identified (Collin 2008, Anctil & Ali). Both the adaptive value (Collin, 2008) and developmental mechanisms (Raymond and Barthel, 2004) of the cone mosaic remain hypothetical.

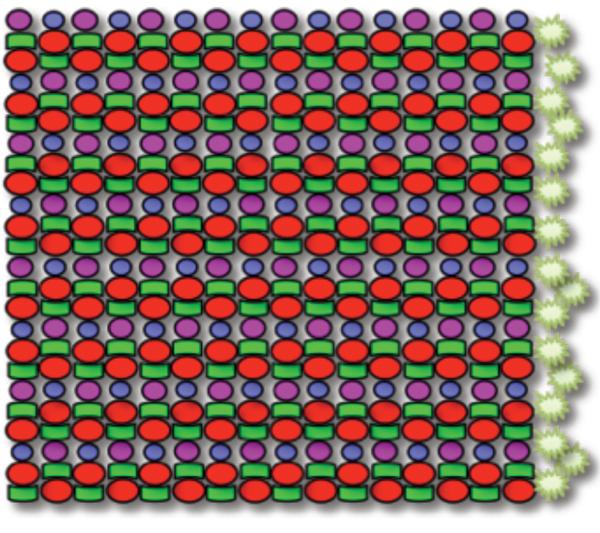

Amongst teleost species investigated (Engstom, 1960; 1963), the row mosaic in zebrafish, Danio rerio, is one of the most precise in its arrangement of cones with photoreceptors rarely out of register with the pattern. Zebrafish possess four cone spectral subtypes: ultraviolet (UV)-, blue-, green-, and red-sensitive cones that express SWS1 (also known as opn1sw1), SWS2 (also known as opn1sw2), RH2 (also known as opn1mw1, opn1mw2, opn1mw3, opn1mw4), or LWS (also known as opn1lw1, opn1lw2) cone opsin genes, respectively (Allison et al., 2004; Cameron, 2002; Chinen et al., 2003; Raymond et al., 1993; Raymond et al., 1996; Vihtelic et al., 1999). This stereotyped pattern of cones (Figure 1) includes a fixed ratio of cones from each subtype, wherein red- or green-sensitive cones occur twice as often as UV-or blue-sensitive cones. Rows of red-/green-sensitive double cone pairs alternate with rows of blue- and UV-sensitive single cones, and these cone rows radiate outward as meridians orthogonal to the retinal perimeter. The morphology of this mosaic has been established using histology (Engstom, 1960) and the identity of the cone subtypes has been established through opsin gene expression analysis (Raymond et al., 1993; Raymond et al., 1996; Takechi and Kawamura, 2005), opsin immunohistochemistry (Vihtelic et al., 1999), and by matching cone morphology to spectral absorbance measured by microspectrophotometry (Allison et al., 2004; Cameron, 2002; Nawrocki et al., 1985; Robinson et al., 1993).

Figure 1.

Schematic of the planar mosaic arrangement of cone photoreceptors in zebrafish: a heterotypic mosaic of cone subtypes organized in a precise, reiterated row pattern. Four cone photoreceptor subtypes are present, including UV (magenta), B (blue), G (green), and R (red) in a precise ratio: twice as many R or G cones relative to UV or B cones, and equal numbers of R and G cones, and equal numbers of B and UV cones. The spatial arrangement is highly stereotyped, with alternating rows of R/G double cones and B/UV single cones. The starbursts represent proliferating cells that give rise to new cone photoreceptors throughout the life of the fish in the marginal germinal zone -- an annulus orthogonal to the cone rows and at the boundary between neural retina and ciliary epithelium.

In this study we used zebrafish as a model to gain insights into formation of the vertebrate cone mosaic. Because the retina of teleosts continues to grow by addition of new cells throughout the life of the fish, some developmental mechanism must also allow the pattern and/or identity of differentiating cones to be continuously replicated (Raymond and Barthel, 2004). Addition of new cells at the retinal periphery is analogous to addition of rings on a tree; thus when viewed in flat-mount, retina that was generated in the embryo and larva is in the center of the retina near the optic nerve head, whereas more recently generated retina is towards the tissue periphery (the outermost ‘rings’). We anticipate that the specification of cone identity and position are closely intertwined, consistent with the spatiotemporal relationship of cone differentiation and selective expression of opsin genes (Stenkamp et al., 1997; Stenkamp et al., 1996). Zebrafish are a premier genetic and developmental model for understanding both cone mosaic formation (Cameron and Carney, 2000; Raymond and Barthel, 2004; Raymond and Hitchcock, 2004; Stenkamp and Cameron, 2002) and vertebrate cone subtype specification/differentiation (Adler and Raymond, 2008; Takechi et al., 2008).

Here we report our observation that all spectral subtypes of cone photoreceptors in larval zebrafish are distributed in a regular heterotypic mosaic, but the precise row mosaic pattern of adult fish is lacking; further, the ratio of cone spectral subtypes in the larva differs from the adult retina. We then asked whether the cone photoreceptors generated during larval development later reorganize into the adult row mosaic, or instead retain the larval pattern. Our analyses using birthdating techniques to identify the larval photoreceptors showed that the latter was true, i.e. the remnant of larval retina in the adult fish retains the less organized mosaic pattern characteristic of the larval retina. Our observations provide a unique opportunity to examine mechanisms of heterotypic mosaic formation through comparing ontogenetic stages within the zebrafish model organism.

Materials and Methods

Animal Care and Use

Zebrafish (Danio rerio) were raised and maintained using standard protocols (Westerfield, 1995) in E3 media and aquaria system water at 28.5 °C with or without PTU (1-phenyl-2-thiourea ) to block formation of melanin pigment. Most experiments used transgenic zebrafish Tg(−5.5opn1sw1:EGFP)kj9 expressing GFP in the UV cones, driven by SWS1 opsin (ZFin ID: ZDB-GENE-991109-25) promoter in a WIK genetic background (Takechi et al., 2003). To isolate neural retina in adults, the fish were dark-adapted overnight, the neural retina was dissected away from other ocular tissues and fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde with 5% sucrose in phosphate buffered saline (pH 7.4). To visualize larval retina, 3 or 4 days post-fertilization fish were fixed in this same fixative and dissected to remove lenses and eyes were mounted to visualize cones through the sclera. Tissues were mounted in a glycerol-based p-phenylenediamine antifade medium (Johnson and Araujo, 1981). All procedures were approved by the Use and Care of Animals in Research Committee at the University of Michigan.

Cell Birthdating

Thymidine analogs 5-bromo-2′-deoxyuridine (BrdU; Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis MO; #B5002) and/or 5-iodo-2′-deoxyuridine (IdU; MP Biochemicals, Solon, OH: #100537) were diluted in E3 media at 10mM and fish were maintained in this water overnight at 28.5 °C (Westerfield, 1995). BrdU was detected using rat-anti-BrdU antibody (raised against BrdU, Accurate Chemical, Westbury NY; # OBT0030S; diluted 1:50) that labels BrdU (but not IdU) and/or mouse-anti-BrdU (raised against BrdU, BD Pharmingen, San Diego, CA; #555627; diluted 1:50) that labels both BrdU and IdU (Vega and Peterson, 2005). These antibodies failed to label the retina if BrdU or IdU were not applied to the animal (data not shown). The detection of BrdU and/or IdU was carried out following in situ hybridization with labelled cone opsin riboprobes, if appropriate, and was preceded by treatment with 2N HCl for 30 minutes. Immunohistochemistry was performed on isolated neural retinas. A blocking step consisted of incubating retinas in 10% normal goat serum diluted in Phosphate Buffered Saline containing 1% Tween 20, 1% Triton X-100 and 1% dimethyl sulphoxide at pH 7.2 (PBS-TTD). Antibodies were diluted in 2% heat-inactivated goat serum diluted in PBS-TTD. Secondary antibodies were anti-mouse and anti-rat conjugated to AlexaFluor fluorochromes 488, 568 or 647 (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA) diluted in the same buffer at 1:1000.

Multiplex in situ hybridization to detect cone positions

The location of blue-, greenand red-sensitive cones (B, G and R cones) utilized previously established (Raymond and Barthel, 2004; Takechi and Kawamura, 2005) in situ hybridization riboprobes against appropriate opsins, in combination with multiplex fluorescent detection technology. To ensure detection of all green-sensitive cones, we used a cocktail of digoxigenin-labelled riboprobes against the four medium wavelength sensitive opsins of zebrafish (opn1mw1, opn1mw2, opn1mw3, & opn1mw4, accession numbers AF109369, AB087806, AB087807, & AF109370, ZFin ID: ZDB-GENE-990604-42, ZFIN:ZDB-GENE-030728-5, ZFIN:ZDB-GENE-030728-6, & ZDB-GENE-990604-43). Fluorescein-labelled riboprobes against the blue-sensitive opsin (opn1sw2, accession number AF109372, ZDB-GENE-990604-40) was synthesized as previously described (Barthel and Raymond, 2000). To ensure detection of all red-sensitive cones, we applied riboprobes against both long wavelength sensitive opsins (opn1lw1 & opn1lw2, accession numbers AF109371 & AB087804, ZDB-GENE-990604-41 & ZDB-GENE-040718-141) labelled with dinitrophenol. Dinitrophenollabelled riboprobes were synthesized using unlabelled ribonucleotides (Roche Diagnostics, Indianapolis, IN; #11-277057-001) in an in vitro transcription reaction and these riboprobes were then covalently linked to dinitrophenol using a kit (Mirus Corporation, Madison, WI; # MIR 3800) as per the manufacturer’s instructions. Full-length anti-sense riboprobes (varying in length, see accession numbers) were synthesized from linearized plasmid in each case. These seven individually-synthesized riboprobes have each been used in previously published papers (Barthel and Raymond, 2000; Raymond and Barthel, 2004; Takechi and Kawamura, 2005) and were mixed into a cocktail and applied in excess to isolated retinas as described previously (Barthel and Raymond, 2000) except that hybridization temperatures and post-hybridization washes were 65°C. Riboprobes were detected serially using anti-digoxigenin (antibody produced by direct immunization of digoxigenin into sheep, then ion-exchange chromatography and immunosorption were used to isolate IgG; Roche Diagnostics; # 11207733910), anti-fluorescein (antibody produced by direct immunization of fluoroscein into sheep, then ion-exchange chromatography and immunosorption were used to isolate IgG; Roche Diagnostics; #11426346910) or anti-dinitrophenol antibodies (Perkin-Elmer; # NEL747A001KT) conjugated to peroxidase. These antibodies failed to label retina in any recognizable pattern if riboprobes were not applied during hybridizations (data not shown). Following application of the antibody as described previously (Barthel and Raymond, 2000), the tissue was incubated in tyramide conjugated to AlexaFluor 350, 568 or 647 (Invitrogen # T20917, T20914 or T20926) or conjugated to biotin (Perkin-Elmer; #NEL700) as per manufacturer’s protocols. The latter was detected with streptadvidin-conjugated-AlexaFluor405 (Invitrogen # S32351). After development of each fluorescent signal, the antibody was deactivated by incubating the tissue in 1.5% H2O2 for 30 minutes at room temperature. After several washes with PBS-TTD the tissue was processed with next antibody and the appropriate tyramide-conjugated-fluorochrome. Variations in the order of the fluorescent detection did not produce noticeably different results. Application of full length sense riboprobes failed to produce any recognizable signal. Following in situ hybridization and visualization of all signals, the GFP within UV-sensitive cones was detected using immunocytochemistry with rabbit-anti-GFP (1:500, IgG fraction of antibody raised against GFP isolated directly from Aequorea Victoria, Invitrogen; # A11122) and anti-rabbit-AlexaFluor488 (1:1000, Invitrogen # A21441). These antibodies failed to label the retina if the animal lacked the expression of GFP (data not shown). Images were collected on a Zeiss Axio Image.Z1 Epifluorescent Microscope (Carl Zeiss MicroImaging Inc., Thornwood, NY) including using the Mosaix function to collect multiple high-magnification images for reconstruction into an image of the entire retina. All images presented are a single focal plane except in Figure 6, which stitches together multiple images collected at several focal planes.

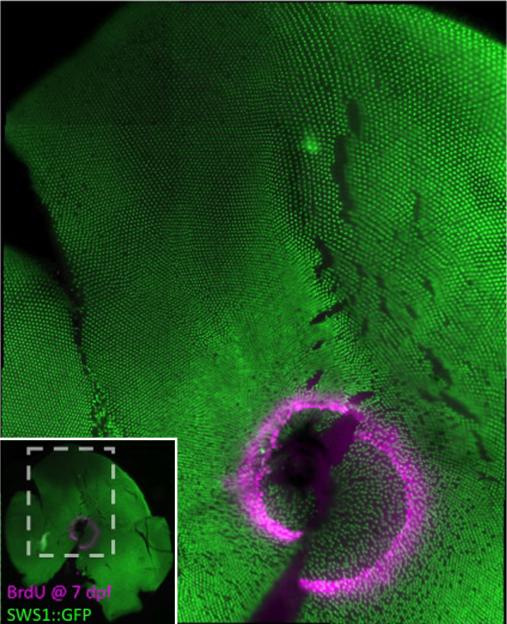

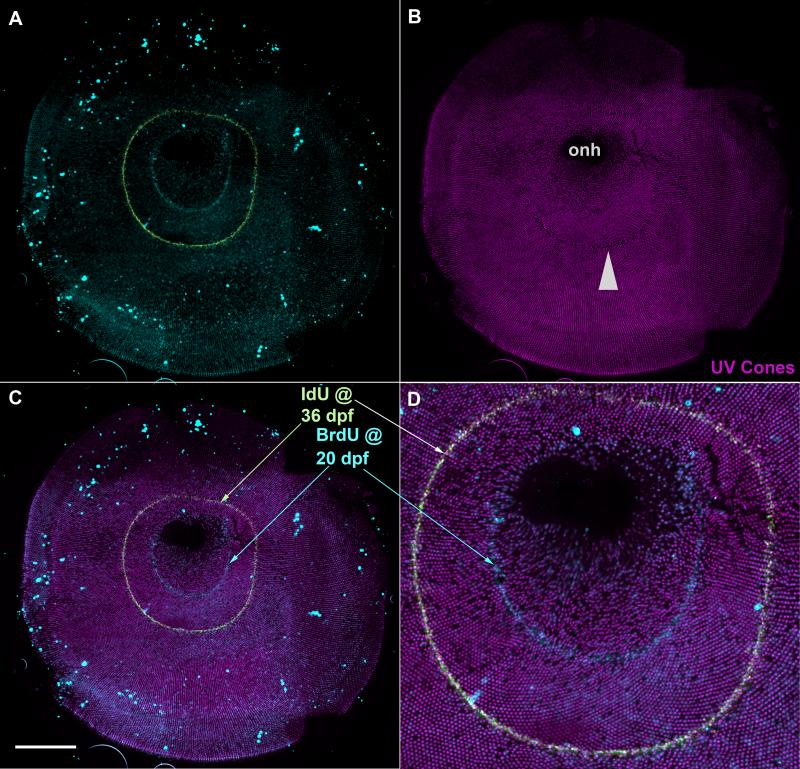

Figure 6.

Flat-mounted retina demonstrates that the retina that was generated in the larval zebrafish is retained as a ‘larval remnant’, i.e. a relatively disorganized region of cone mosaic in the adult fish. The pattern of UV cones is more regular in the retina that was generated later, by continuous retinal growth in the adult. This transgenic zebrafish (UV cones labeled with GFP) was treated with BrdU at 7 dpf and sacrificed when 3-months-old. The lack of a row pattern of UV cones within and immediately adjacent to the ring of BrdU indicates that this ‘larval remnant’ of retina remains less organized in the adult fish. Inset shows location of the main image (gray dashed lines) within the entire retinal flat-mount.

Image manipulation and identifying centers of cones

In determining the location of each cone class we found that relatively automated detection of fluorescent signal was adequate for the UV-and blue-sensitive cones. Here we utilized thresholding functions in Zeiss AxioVision software (Release 4.5) to outline the fluorescent signal from either of the cone subtypes, with some adjustments by hand, and recorded the x-y coordinates of the center of each cone as determined by the Zeiss AxioVision software function. For the red- and green-sensitive cones we found the thresholding functions were not as reliable in representing cone positions; this is likely due to anatomical features of the red- and green-sensitive cones (elongated apical-basal axis) and their higher density, which sometimes resulted in a lack of physical separation between the signals from individual cells when viewed in flat-mount preparations. Thus we outlined the fluorescent signal from red and green cone opsin by hand with a digitizing tablet (Intuos2 Graphics Tablet, Wacom Ltd., Tokyo, Japan; model # XD-0912-U) and recorded the x-y coordinates of the centers of the profiles. We note that these methods do not necessarily determine the morphological centers of the cone profiles but rather the centers of the opsin mRNA or GFP localization. The x-y coordinates of the centers were plotted (Microsoft Excel) for visualization. Images were merged in Axioimager such that the fluorescent signals representing red-, green-, blue- and UV-sensitive opsins were pseudocoloured red, green, cyan and magenta, respectively. Images presented were merged, cropped, pseudocoloured and adjusted for brightness and contrast using Zeiss AxioVision software (Release 4.5) and/or Adobe Photoshop CS3 10.0.1.

Statistical analysis of cone patterns

To quantify the patterns of distribution of cone photoreceptors we calculated several indices. These included the ratio of each cone subtype relative to other cone subtypes in a given retinal area. For this purpose we counted the number of labelled cones and compared the ratio of cones using heterogeneity χ2 tests to the expected frequencies in the canonical zebrafish row mosaic: an equal number of R and G cones, an equal number of UV and B cones, and twice as many R or G compared with B or UV. To analyze the homotypic regularity of cones, i.e. the regularity in spacing of one cone subtype relative to others of the same subtype, we used the x-y coordinates of the centers of the cone opsin signals. Heterotypic regularity of cones, i.e. the regularity in spacing of one cone subtype in relationship to another subtype, was similarly calculated using the Pythagorean distance between the centers of two cones of different types. Mean nearestn-eighbor distances of cones were determined and conformity ratios were calculated (Cameron and Carney, 2000; Cook and Chalupa, 2000) to assess the amount of variance in cone spacing. Statistical significance of the conformity ratio as a measure of regularity of cone spacing was determined as recommended (Cook, 1996). The individual conformity ratios and cone ratios from multiple images were then compared by Kruskal-Wallis analysis of variance by ranks test calculated in SPSS (Statistical Package for the Social Sciences, Chicago IL).

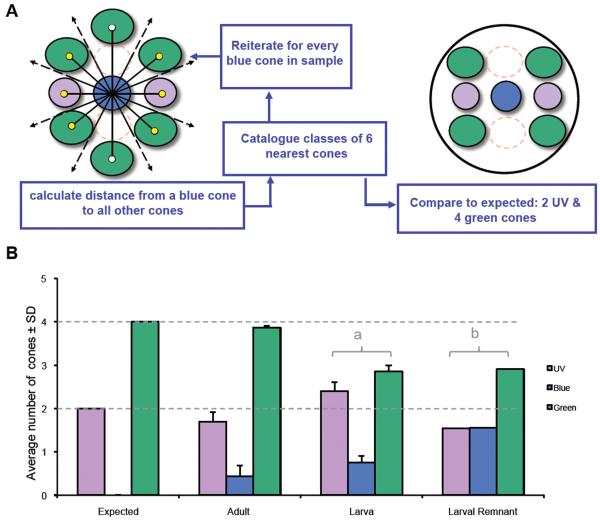

We also developed a novel index of local cone pattern that we have termed a ‘mosaic metric’. We reasoned that local variations in the heterotypic mosaic pattern would change the identity of the cone neighbors. We chose to assess the identity of the cones nearest to a given B cone, reiterate the process for every B cone in a sample, and report the averages of the neighboring cone subtypes in a given retinal region. For example, considering the schematic of the row mosaic in Figure 1, one expects that the eight closest neighbors to any blue cone would consist of two UV cones, two R cones, four G cones, and zero B cones. Due to sample availability, our analysis focused on triple-labelled material; R cones were not labelled and we noted the identity of the six cones closest to each B cone, expecting them to include two UV cones, four G cones and zero B cones. To perform this calculation we created algorithms in MatLab that 1) calculated the Pythagorean distance between the center of a given B cone and the center of every other cone in the array; 2) ranked these distances to calculate which were the six nearest cones; 3) reported the identity of these six cones in terms of cone opsin expression; 4) reiterated steps 1-3 for every blue cone in the sample; 5) calculated the mean number of each neighbor subtype for a given region. These means were expressed as ratios and compared to the expected values using a χ2 test as calculated in SPSS.

In regards to terminology used, we characterized the cone photoreceptors in larval retina, and adult retinas. In adults, we discriminate between the retina generated during larval development and that retina generated later in life. The former we denote as ‘larval remnant’. For simplicity we denote the latter, which represents cones that are not positioned near the optic nerve head, as ‘adult’.

Results

Multiplex in situ hybridization of opsins is effective for analysis of cone patterns

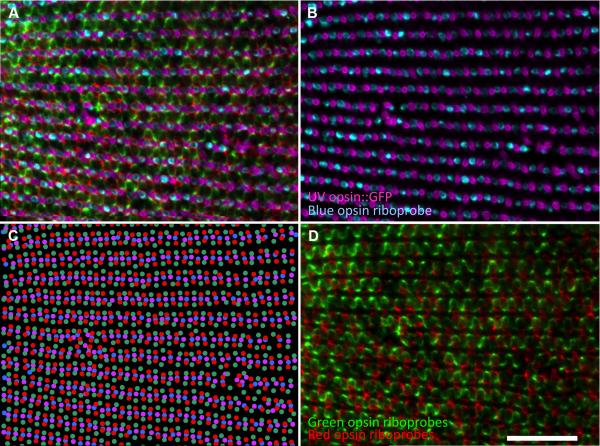

To understand how the heterotypic mosaic of cells is patterned we first developed methods based on a combination of histological, in situ hybridization and immunocytochemical analysis to identify multiple cone subtypes in a single retinal preparation and to analyze their local spatial relationships. We assessed our methods in adult zebrafish cone mosaics, where a canonical ‘row mosaic’ is known to be present (Figure 1). To reveal the complete mosaic pattern we used in situ hybridization labelling of opsins for three cone subtypes (blue-, green- and redsensitive opsins) in retinas from transgenic fish that express GFP in the UV-sensitive cones (Figure 2). This image is representative of the labelling throughout the adult zebrafish retina in locations that develop in post-larval stages of fish life, i.e., regions that are not adjacent to the optic nerve head. Rows of single blue- and UV-sensitive cones alternating with rows of double red- and green-sensitive cones radiate outward from the posterior pole, and to accommodate the increasing circumference, additional cone rows are periodically added, creating Y-junctions (Nishiwaki et al., 1997). Multiple opsin subtypes were not detected within individual cone photoreceptors, and the similarity of the labelling pattern to the canonical row mosaic pattern further confirms the specificity of each of these riboprobes (Barthel and Raymond, 2000; Raymond and Barthel, 2004; Takechi and Kawamura, 2005).

Figure 2.

Cone photoreceptor subtype positions in a retina from an adult zebrafish determined by markers for opsin expression. A. Triple-label multiplex in situ hybridization using riboprobes against blue-, green- and red-sensitive opsins on a transgenic retina expressing GFP in UV-sensitive cones. Fluorescent signals are pseudo-coloured cyan, green, red and magenta, respectively. Panel B is the same field as A with only UV and B channels; D is the same field as A with only the G and R channels. C. Excel plot of experimental data presented in panel A. Note the central retina (i.e., optic nerve head) is to the left in this image and the retinal periphery is to the right, such that the rows of cones are slightly further apart towards the periphery. Panel C and D are replicated as Supplemental Figure in magenta-green. Scale bar represents 50 μm.

We plotted the centers of each of the cone spectral subtypes to reveal their spatial patterns (Figure 2C). The resemblance of this pattern to the schematic version of the canonical row mosaic is apparent (compare Figures 1 and 2C). The distance between the rows of red-green cones is greater than in our schematic. This may be due to the presence of rods and/or the fact that our method defines the centre of the cones based on the centre of the riboprobe labelling not the center of the cone defined by morphology. Note the reiterated mirror-symmetry of the cone mosaic pattern in the direction orthogonal to the rows of double and single cones: blue cones are flanked by red cones and UV cones are flanked by green cones. The ratios of cone subtypes in various retinal areas (dorsal, ventral, temporal, nasal) of adult fish, excluding the region near the optic nerve head, are not significantly different from the expected ratios of 1:1 for R:G or U:B and 2:1 for R or G:B or UV (Table 1 and Figure 3).

Table 1.

Cone photoreceptor occurrence in zebrafish retina comparing cone subtype ratios in various areas and developmental stages to expected cone distributions.

| Retinal Area |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Expected1 |

Adult |

Larvae |

Larval Remnant in Adult |

|

|

Cone Ratios2 |

||||

| U:B | 1.0 | 0.83 ± 0.22 (22) | 1.15 ± 0.24 (11) | 0.35 ± 0.21 (4) |

| U:G | 0.5 | 0.49 ± 0.08 (17) | 0.87 ± 0.22 (11) | 0.64 (1) |

| U:R | 0.5 | 0.31 ± 0.20 (4) | 0.87 ± 0.36 (4) | 0.15 ± 0.36 (3) |

| B:R | 0.5 | 0.47 ± 0.04 (4) | 0.66 ± 0.11 (12) | 0.54 ± 0.11 (3) |

| B:G | 0.5 | 0.54 ± 0.06 (17) | 0.83 ± 0.15 (19) | 1.08 (1) |

| R:G | 1.0 | 0.99 ± 0.06 (3) | 1.27 ± 0.27 (13) | nd |

Based on schematic representations and histology of adult fish, see Introduction and Figure 1.

Cone names abbreviated U, B, G, & R refer to ultraviolet-, blue, green- & red-sensitive cones respectively. Results for cone ratios presented ± standard deviation. Within brackets is number of larvae sampled or number of regions examined in adults. nd, not determined.

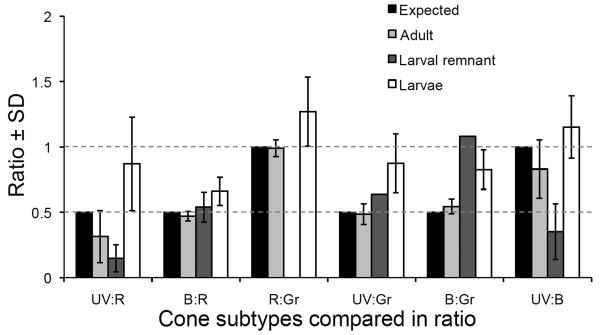

Figure 3.

Ratios of cone photoreceptor subtypes in various stages of zebrafish development. The canonical row mosaic of adult zebrafish predicts ratios of cones (black bars and dotted lines, e.g. see Figure 1). The ratios observed in adults are not significantly different from expected (χ2, p> 0.05). Cone ratios in larvae are significantly different from expected (χ2, p< 0.03), with an excess of UV cones relative to other types, and an excess of B cones relative to R or G cones compared to that expected from the canonical row mosaic. Cone ratios within the region of retina surrounding the optic nerve head that was generated during larval development (the larval remnant) are also different from expected (χ2, p< 0.03). See also Table 1. Data is represented as ratios ± standard deviation.

Larval cone photoreceptors have heterotypic mosaic patterns but lack the canonical row mosaic of adults

In multiplex preparations of whole-mount larval zebrafish retinas the canonical row mosaic described in Figure 1 is not apparent (Figure 4). We first examined the homotypic mosaic patterns for each spectral subtype in the larval retina by analyzing the conformity ratios, a ratio of the average nearest-neighbour distance to the standard deviation. The values of conformity ratios obtained for the various cone subtypes measured in larvae (Table 2) indicate the spacing of each cone subtype is highly regular (i.e., significantly different from a random or clumped distribution). Notably, the conformity ratios of the UV cones were significantly lower in the larvae compared with adults (p=0.002) as determined by one-way ANOVA. Thus homotypic cone relationships are highly regular in zebrafish larvae, but not as regular as in the adult.

Figure 4.

Cone photoreceptor subtype positions in a retina from a larval zebrafish (four days post-fertilization) determined by markers for opsin expression. A. Double-label in situ hybridization using riboprobes against blue- and greensensitive opsins on a transgenic retina expressing GFP in UV-sensitive cones. Fluorescent signals are pseudo-coloured cyan, green, and magenta, respectively. The areas not occupied by fluorescent signal can be expected to predominantly contain red-sensitive cones and a few rods (data not shown). Panels B thru F are the same field as A, with only subsets of the channels displayed. Panel B displays B and G channels; Panel C displays UV and B channels; Panel D displays UV and G channels; Panel E displays the G channel; Panel F displays the B channel. Figure 4 is replicated as the Supplemental Figure 2 with the same data represented in magentagreen. Scale bar represents 50 μm.

Table 2.

Regularity of spacing of cone photoreceptor subtypes in zebrafish retina comparing various areas and developmental stages.

| Retinal Area |

|||

|---|---|---|---|

| Adult |

Larvae |

Larval Remnant in Adult |

|

|

Conformity Ratio1 |

|||

| U | 10.6 ± 0.83 (4)a | 6.91 ± 0.40 (11)a | 4.39 ± 1.32 (4)a |

| B | 8.10 ± 1.19 (5)a | 5.19 ± 1.79 (6)a | 4.39 (1)a |

| G | 6.47 ± 0.73 (6)a | 5.19 ± 1.94 (4)a | 6.22 (1)a |

| R | 6.96 (1)a | 5.38 ± 1.67 (5)a | 2.52 ± 1.40 (2)a,e |

| U→B | 4.04 ± 1.18 (5)a | 3.56 ± 0.78 (6)5a,1c | 3.28 ± 0.30 (2)a,d |

| B→U | 3.23 ± 1.12 (5)a | 2.83 ± 0.62 (6)3a,3d | 1.93 ± 0.29 (2)c,d |

| U→G | 3.05 ± 0.69 (4)a | 3.35 ± 0.75 (6)5a,1e | 4.48 (1)a |

| B→R | 4.40 (1)a | 3.22 ± 0.59 (5)a | 2.45 (1)c |

| B→G | 4.13 ± 0.72 (4)a | 3.97 ± 0.62 (6)a | nd |

Data presented as mean of conformity ratios for multiple samples and the standard deviation around this mean. Bracketed number represents the number of fish sampled. Conformity ratio is a measure of the regularity of cone spacing within each sample (Nearest-neighbour distance / Standard deviation) with higher ratios indicating more regularity. Where a single cone type is listed, homotypic conformity ratios are reported. Where two cone types are listed, the distance from each of the first cone subtype to the nearest neighbor of the second subtype was calculated. Cone names abbreviated U, B, G, & R refer to ultraviolet-, blue, green- & red-sensitive cones respectively. Nd, not determined.

Significant non-randomness of cone spacing towards regularity is indicated as

= <0.0001

= p<0.001

= p<0.01

= p<0.05

= p>0.05

(not significant). Where one superscript is listed, each individual fish met this significance criterion. Where multiple subscripts are listed this represents significance for different individual fish. Where a superscript is preceded by a number, this represents the number of fish in the treatment that reached this level of significance.

We next asked whether the ratio of cone subtypes in larval retinas was the same as in the adult and we found that it was not. We counted the number of each cone subtype in whole-mount preparations with two, three or four cone subtypes labeled and found the ratios are significantly different from ratios in adult retinas (p<0.001) and from the expected ratio in the row mosaic (p<0.02), and the variances of the larval cone ratios are greater (Table 1, Figure 3). Compared to the expected or adult retina, the larval retinas have an excess of UV cones relative to all other subtypes, and an excess of B cones relative to R and G cones.

The mosaic metric tool also revealed a difference between the larvae and adult (Figure 5) that is consistent with an excess of UV cones in larvae. We assessed the fidelity of the mosaic metric tool by applying it to adult fish: this produced numbers that are not significantly different from expected (χ2, p>0.25; 17 images from n=3 fish). In larval fish (four days post-fertilization) the local order of cones assessed by the mosaic metric was significantly different from expected (χ2, p<0.025; 6 images from 6 fish). The mosaic metric data from larvae were also significantly different from adults (using the assumption in the statistical test that the mean of the data from adults is the expected ratio).

Figure 5.

The mosaic metric index reveals local cone patterns in adult retinas consistent with the canonical row pattern, whereas larval retinas show more variability. A. The mosaic metric catalogues the identity of the six cones closest to each B cone in the sample by first finding the distance from a B cone to every cone (lines with empty circles or arrowheads) and indentifying the six closest cones (yellow circles). This is then reiterated for every B cone and data is compiled for comparison to expected values. The samples are labelled for B, UV and G cones only, thus R cones are represented by dashed circles. For the canonical row mosaic we expect the result to be 2 UV cones, 0 B cones and 4 G cones. B. Mosaic metric analysis: Cone patterns in adult retinas are not significantly different from expected (χ2, p>0.25; 17 images from n=3 fish). Cone patterns in a larval retina are significantly different from expected (χ2, p<0.025, n= 6 fish; labeled on figure by ‘a’). Cone patterns in a remnant of larval retina retained in the adult (n=149 blue cones in one retina) are also significantly different from expected (χ2, p<0.0001, noted on figure by ‘b’), although the nature of the difference is distinct in the larvae and larval remnant. Dotted lines note expected values, which are also indicated by the data set on the left of the graph.

Despite the lack of a regular row pattern in the larval retina, the arrangement of cone subtypes relative to one another is not random. We assessed the regularity of spacing between heterotypic cones by calculating the conformity ratios of cone subtype pairs (Table 2). Larval heterotypic conformity ratios (higher numbers indicating regularity) are significantly different from random, towards regularity, regardless of cone types being compared. We further assessed the regularity of the larval mosaic cone by adapting our mosaic metric algorithm to report the identity of the nearest neighbor (rather than the six nearest neighbours, see above). The identity of the nearest neighbor is not random: the nearest neighbour to a green cone in larval retina is typically a red cone (71.0% ± 10.6, n=8, red, green and blue cone positions considered) whereas in a random distribution of neighbours it would conservatively be expected to be less than 40%. The regularity of the cone mosaic in larval retinas is also observable based on the small variance between samples (Figure 5). Thus the larval cone mosaic of zebrafish does not have the canonical row mosaic, but nor are the homotypic mosaics uncorrelated. Instead, the larval cone positions of blue cones with respect to UV, red and green cones all satisfy the definition of a heterotypic mosaic of cells.

Transition to the adult pattern

We next addressed the timing of the transition between the larval and adult mosaics. We used cell birthdating to mark the developmental age of cone photoreceptors; we exposed zebrafish larvae to BrdU at seven days postfertilization and allowed the fish to grow for several months and then prepared retinal flat-mounts. Figure 6 demonstrates the pattern of UV cones in a representative example. Inspection of the image reveals regular rows of UV cones throughout most of the retina with the exception of the region within the ring of BrdU labeling and immediately adjacent to it. Conformity ratios of UV cone spacing (Table 2) confirm that the distribution of UV cones in this larval ‘remnant’ within the BrdU ring is significantly less regular (p< 0.001) than in more peripheral regions, but not different from the larval retina (p= 0.112). Our analysis of cone ratios and mosaic metric (Figure 3 and 5) also support our observation that the distribution of cones in the larval remnant of retina is less regular than in the latergenerated retina. Interpretations of the mosaic metric data must consider the changing ratios of cone abundance that are evident in the larval remnant (e.g. lower abundance of UV cones compared to blue cones); indeed the differences in mosaic metric output between the larval remnant and other tissues could be driven by changes in cone ratios. This does not affect the primary observation that the larval mosaic is not remodeled to be indistinguishable from that of the adult; i.e. a larval remnant can be recognized. This conclusion is qualitatively apparent (Figure 6 and 7) and quantitatively supported by differences in cone ratios (e.g. an abundance of blue cones compared to green cones, see Table 1) and conformity ratios (e.g. heterotypic regularity of red cone spacing relative to blue cones, see Table 2) that do not include the UV cones.

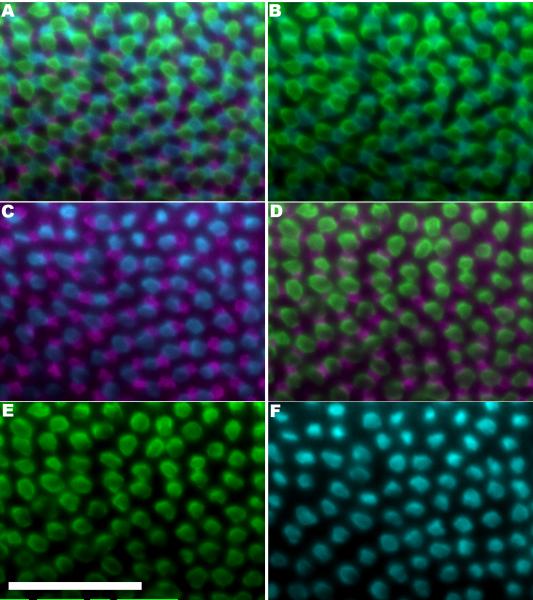

Figure 7.

Flat-mounted retina demonstrates that the row pattern appears in the retinal region that is generated after larval stages. This transgenic zebrafish (UV cones labeled with GFP, pseudocoloured magenta) was treated with BrdU at 20 dpf, and IdU at 36 dpf, and sacrificed when 8-months-old. A. Rings of BrdU (blue) or IdU (yellowish-green) mark the extent of the retina at the time of treatment; the retina within the BrdU ring was generated when the fish was younger than 20 dpf and includes the optic nerve head (onh). B. UV cones expressing GFP (pseudocoloured magenta) are aligned in regular rows throughout most of the retina. C. Merge of UV cone and thymidine analogues reveals timing of change in cone pattern. D. Higher magnification view: UV cones begin to be patterned into rows between the BrdU and IdU rings. The pattern of UV cones was transiently disrupted by IdU treatment (arrowhead in B) however it is apparent that the cones were patterned prior to this (D). Scale bar represents 500 μm.

To determine when the row mosaic appears, we applied thymidine analogues BrdU or IdU at different developmental stages: we exposed fish near the end of larval development (20 days-post-fertilization, dpf) to BrdU and then to IdU at 36 dpf (Figure 7 and data not shown). The larval stage in zebrafish is complete at approximately 3 weeks depending on the characters used in its definition (Brown, 1997; Parichy and Turner, 2003). The row mosaic pattern becomes apparent between the BrdU and IdU rings in Figure 7, which suggests that cones generated in the postlarval retina become organized into rows. Note that the application of IdU appears to have transiently caused a loss of UV cones; gaps in the regular array occur in and immediately peripheral to the IdU ring (Fig. 7D). Although we are uncertain of the reason for this disruption, it may be a result of toxicity of the IdU label. Regardless, this does not affect our conclusion that UV cones had become regularly patterned prior to IdU application.

DISCUSSION

For this morphometric, quantitative analysis of the spatiotemporal pattern of the cone mosaic in zebrafish, we used three separate indices of cone pattern: 1) The conformity ratio, which measures the local regularity of spacing of the mosaic pattern for a given spectral cone subtype(s); this index showed that cones in larvae are regularly spaced (see also (Raymond and Barthel, 2004)) but not as regularly as in adults. 2) Ratios of cone spectral subtypes confirmed that the cone mosaic of larvae is different from that of adults. 3) We developed a novel ‘mosaic metric’ algorithm to assess local and second-order cone spacing; this measure further confirmed our overall findings.

We offer the following general conclusions: 1) The cone photoreceptors in zebrafish larvae have a heterotypic mosaic array but lack the row mosaic pattern characteristic of the adult retina. 2) The ratio of cone spectral subtypes in the larval retina is different from the adult ratio (adults possess equal numbers of R and G cones, equal numbers of B and UV cones, and twice as many R and G as B and UV) — larvae have an excess of UV cones and a smaller excess of B cones. 3) The cones generated in the larval retina do not reorganize into a row mosaic pattern as the retina continues to grow; some remodeling of this larval mosaic may occur, however a ‘larval remnant’ that lacks the row mosaic can be identified adjacent to the optic nerve head in the adult retina. 4) The ontogenetic transition of zebrafish cone photoreceptors into the precise organization of the row mosaic provides baseline data to understand formation and refinement of heterotypic mosaics. 5) The ontogeny of the canonical row mosaic is approximately coincident with a metamorphic transition and may be associated with new visually-mediated tasks.

The absence of the canonical row cone mosaic had not previously been noted in larval zebrafish retina. This new observation raises the intriguing question of how the organization of larval cones might be transformed into the canonical, famously precise, pattern of the adult zebrafish retina. One possible mechanism for refining the cone mosaic pattern is cell death, a process that is known to model cone mosaics of developing salmonids (Allison et al., 2006); cell death has been reported in the larval zebrafish retina (Biehlmaier et al., 2001). Another mechanism might be cell movements, especially occurring in concert with cell death. Cell movements have been shown to play a role in forming heterotypic mosaics in other systems (Eglen, 2006). However, our analysis showed that remodeling of the larval cone mosaic pattern by cell death or cell movement is not required, since the precise row mosaic pattern of the adult retina is generated entirely by post-larval growth, and the larval mosaic pattern persists in the retina of the adult fish as a remnant surrounding the optic disc. Our analysis has not excluded cell death and cell movements as potential mechanisms shaping the cone mosaic pattern; indeed, our data suggest that differential loss of UV cones, differential addition of blue cones, and/or other remodeling might occur in the larval remnant. It remains to be determined if a larval remnant of cone mosaic pattern exists in other teleost species.

Previous studies have identified two phases of cone photoreceptor differentiation during zebrafish ontogeny. The first phase is a wave of cone photoreceptor differentiation that sweeps around the retina from the site of initial differentiation, which is confined to a small ventral patch of retina (Hu and Easter, 1999; Raymond and Barthel, 2004). The second phase involves retinal growth by addition of new cone photoreceptors, and other retinal neurons, at the periphery (Hu and Easter, 1999; Raymond and Barthel, 2004; Raymond and Hitchcock, 2004). We have now identified a third phase of cone differentiation in zebrafish, in which the positioning and choice of cell fate of newly generated cones assumes a greater level of precision. An unanswered but intriguing question is whether a correct ratio of cone subtypes (2 red : 2 green : 1 blue : 1UV) is sufficient to produce the canonical row mosaic or perhaps is not sufficient but necessary in combination with other factors such as differential cell adhesion (Mochizuki, 2002; Podgorski et al., 2007). Our analysis provides a quantitative, statistical description of cone mosaic order that will allow such hypotheses to be tested by mathematical modeling and biological experimentation.

The remodeling of cone mosaics in fish during ontogeny has been noted in the context of switching between row and square mosaics (Lyall, Malicki, Wan & Stenkamp, Salmo) and other types of mosaic (Beaudet). Movements of individual cones has been noted to be associated with a circadian rhythm (Walls). The functional significance of this is unclear, and speculations on the underlying developmental mechanisms are mostly limited to mathematical modeling. In sum, though, it can be concluded that cone mosaic rearrangements during ontogeny occur in a variety of teleosts.

In regards to the visual ecology of the zebrafish, this transition to a row mosaic of cone photoreceptors is coincident with a metamorphosis in fin morphology and body pigmentation (Brown, 1997; Parichy and Turner, 2003). In several other fish species, dramatic changes in life history stages, accompanied by changes in the photic environment and visual tasks, are associated with changes in opsin abundance (ref Carleton, Veldhoen) and/or cone photoreceptor complement (ref Cameron, Shand, Allison, Beaudet, perch). Thus we speculate that the changes in zebrafish visual system morphology are associated with changes in visuallymediated tasks involving feeding or interacting with conspecifics. These certainly could include changes in the fish mobility related to fin morphogenesis and/or detection of conspecifics associated with changes in pigmentation. Indeed the increased order in cone mosaic pattern reported here is coincident with an increased visually-mediated preference during shoaling behavior (Engeszer et al., 2007). Alternatively, an excess of UV- and blue-sensitive cones mediating increased short wavelength sensitivity may be adaptive in zebrafish larvae despite being incompatible with a canonical row mosaic. This timing is also coincident with changes in the spatial distribution of expression of the various representatives of the RH2 (green-sensitive; also known as opn1mw1, opn1mw2, opn1mw3, opn1mw4) and LWS (red-sensitive; also known as opn1lw1, opn1lw2) classes of opsin mRNAs in zebrafish retinas between two and four weeks of development (Takechi and Kawamura, 2005). Finally, the timing of this ontogenic switch suggests that thyroid hormone (Brown, 1997) or other metamorphic regulators might play a role in regulating cone differentiation and/or patterning. Indeed thyroid signalling plays important roles in photoreceptor patterning and retinal development in diverse vertebrate species (Allison et al., 2006; Applebury et al., 2007; Marsh-Armstrong et al., 1999; Ng et al., 2001; Roberts et al., 2006; Trimarchi et al., 2008) including modulating green-sensitive cone opsin expression in other fish (Temple et al., 2008) and mediating the visual sensitivity of adult zebrafish (Allison et al., 2004).

It will be of interest in future studies to investigate how the mechanisms of mosaic formation change during development. These mechanisms may include interactions of homotypic cells (including via telodendritic interactions), cell migration, cell death, and lateral induction of cell fates (Eglen and Galli-Reta, 2006; Raymond and Barthel, 2004; Stenkamp et al., 1997; Wikler and Rakic, 1991). Mathematical modeling of teleost cone mosaic formation has also been used to argue that differential cell adhesion could allow cone subtypes to adopt specific spatial relationships (Takesue et al., 1998).

In summary, we have identified a novel ontogenetic transition in cone photoreceptor patterning in zebrafish retina. The cone mosaic is an accessible example of an in vivo vertebrate heterotypic cell mosaic that can be assessed with robust cell-specific markers. Combined with the optical transparency, behavioural repertoire and genetic toolkit of the zebrafish, the current work establishes a model to understand the formation and refinement of heterotypic cell mosaics, as well as both the development and function of vertebrate cone photoreceptor mosaics.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

Supported by NIH R01 EY015509 to P.A.R. and NSERC PDF & Discovery Grant to W.T.A. We thank Dilip Pawar, Aleah McCorry and Adina Bujold for technical support.

Table of Abbreviations used in the Figures

- B

blue-sensitive cone

- BrdU

bromodeoxyuridine

- dpf

days post-fertilization

- G

green-sensitive cone

- GFP

Green Fluorescent Protein

- IdU

iododeoxyuridine

- onh

optic nerve head

- R

red-sensitive cone

- UV

ultraviolet-sensitive cone

Literature Cited

- Adler R, Raymond PA. Have we achieved a unified model of photoreceptor cell fate specification in vertebrates? Brain Res. 2008;1192:134–150. doi: 10.1016/j.brainres.2007.03.044. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ali MA, Antcil M. Retinas of fishes: an atlas. Springer-Verlag; Berlin: 1976. [Google Scholar]

- Allison WT, Dann SG, Veldhoen KM, Hawryshyn CW. Degeneration and regeneration of ultraviolet cone photoreceptors during development in rainbow trout. J Comp Neurol. 2006;499(5):702–715. doi: 10.1002/cne.21164. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Allison WT, Haimberger TJ, Hawryshyn CW, Temple SE. Visual pigment composition in zebrafish: Evidence for a rhodopsin - porphyropsin interchange system. Vis Neurosci. 2004;21:945–952. doi: 10.1017/S0952523804216145. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Applebury ML, Farhangfar F, Glosmann M, Hashimoto K, Kage K, Robbins JT, Shibusawa N, Wondisford FE, Zhang H. Transient expression of thyroid hormone nuclear receptor TRbeta2 sets S opsin patterning during cone photoreceptor genesis. Dev Dyn. 2007;236(5):1203–1212. doi: 10.1002/dvdy.21155. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barthel LK, Raymond PA. In situ hybridization studies of retinal neurons. Methods Enzymol. 2000;316:579–590. doi: 10.1016/s0076-6879(00)16751-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Biehlmaier O, Neuhauss SC, Kohler K. Onset and time course of apoptosis in the developing zebrafish retina. Cell Tissue Res. 2001;306(2):199–207. doi: 10.1007/s004410100447. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown DD. The role of thyroid hormone in zebrafish and axolotl development. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1997;94(24):13011–13016. doi: 10.1073/pnas.94.24.13011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cameron DA. Mapping absorbance spectra, cone fractions, and neuronal mechanisms to photopic spectral sensitivity in the zebrafish. Vis Neurosci. 2002;19(3):365–372. doi: 10.1017/s0952523802192121. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cameron DA, Carney LH. Cell mosaic patterns in the native and regenerated inner retina of zebrafish: implications for retinal assembly. J Comp Neurol. 2000;416(3):356–367. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chinen A, Hamaoka T, Yamada Y, Kawamura S. Gene duplication and spectral diversification of cone visual pigments of zebrafish. Genetics. 2003;163(2):663–675. doi: 10.1093/genetics/163.2.663. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Collin SP. A web-based archive for topographic maps of retinal cell distribution in vertebrates. Clinical and Experimental Optometry. 2008;91(1):85–95. doi: 10.1111/j.1444-0938.2007.00228.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Collin SP, Shand J. Retinal sampling and the visual field in fish. In: Collin SP, Marshall NJ, editors. Sensory processing in Aquatic Environments. Springer-Verlag; New York: 2003. pp. 139–169. [Google Scholar]

- Cook JE. Spatial properites of retinal mosaics: an empirical evaluation of some existing measures. Vis Neurosci. 1996;13:15–30. doi: 10.1017/s0952523800007094. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cook JE, Chalupa LM. Retinal mosaics: new insights into an old concept. Trends Neurosci. 2000;23(1):26–34. doi: 10.1016/s0166-2236(99)01487-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eglen SJ. Development of regular cellular spacing in the retina: theoretical models. Mathematical Medicine and Biology-a Journal of the Ima. 2006;23(2):79–99. doi: 10.1093/imammb/dql003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eglen SJ, Galli-Reta L. Retinal Mosaics. In: Sernagor E, Eglen SJ, Harris WA, Wong R, editors. Retinal Development. Cambridge University Press; Cambridge: 2006. pp. 193–207. [Google Scholar]

- Eglen SJ, Lofgreen DD, Raven MA, Reese BE. Analysis of spatial relationships in three dimensions: tools for the study of nerve cell patterning. BMC Neurosci. 2008;9:7. doi: 10.1186/1471-2202-9-68. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eglen SJ, Wong JCT. Spatial constraints underlying the retinal mosaics of two types of horizontal cells in cat and macaque. Vis Neurosci. 2008;25(2):209–214. doi: 10.1017/S0952523808080176. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Engeszer RE, Barbiano LA, Ryan MJ, Parichy DM. Timing and plasticity of shoaling behaviour in the zebrafish, Danio rerio. Anim Behav. 2007;74(5):1269–1275. doi: 10.1016/j.anbehav.2007.01.032. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Engstom K. Cone types and cone arrangements in the retina of some cyprinids. Acta Zoologica (Stockh) 1960;41:277–295. [Google Scholar]

- Engstom K. Cone types and cone arrangements in teleost retinae. Acta Zoologica (Stockh) 1963;44:179–243. [Google Scholar]

- Fuerst PG, Koizumi A, Masland RH, Burgess RW. Neurite arborization and mosaic spacing in the mouse retina require DSCAM. Nature. 2008;451(7177):470–474. doi: 10.1038/nature06514. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hu M, Easter SS. Retinal neurogenesis: the formation of the initial central patch of postmitotic cells. Dev Biol. 1999;207(2):309–321. doi: 10.1006/dbio.1998.9031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnson GD, Araujo GM. A simple method of reducing the fading of immunofluoresence during microscopy. J Immunol Methods. 1981;43:439. doi: 10.1016/0022-1759(81)90183-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marsh-Armstrong N, Huang H, Remo BF, Liu TT, Brown DD. Asymmetric growth and development of the Xenopus laevis retina during metamorphosis is controlled by type III deiodinase. Neuron. 1999;24(4):871–878. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(00)81034-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mochizuki A. Pattern formation of the cone mosaic in the zebrafish retina: A cell rearrangement model. J Theor Biol. 2002;215(3):345–361. doi: 10.1006/jtbi.2001.2508. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nawrocki L, BreMiller R, Streisinger G, Kaplan M. Larval and adult visual pigments of the zebrafish, Brachydanio rerio. Vision Res. 1985;25(11):1569–1576. doi: 10.1016/0042-6989(85)90127-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ng L, Hurley JB, Dierks B, Srinivas M, Salto C, Vennstrom B, Reh TA, Forrest D. A thyroid hormone receptor that is required for the development of green cone photoreceptors. Nat Genet. 2001;27(1):94–98. doi: 10.1038/83829. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nishiwaki Y, Oishi T, Tokunaga F, Morita T. Three-dimensional reconstruction of cone arrangement in the spherical surface of the retina in the medaka eyes. Zool Sci. 1997;14:795–801. [Google Scholar]

- Parichy DM, Turner JM. Zebrafish puma mutant decouples pigment pattern and somatic metamorphosis. Dev Biol. 2003;256(2):242–257. doi: 10.1016/s0012-1606(03)00015-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Podgorski GJ, Bansal M, Flann NS. Regular mosaic pattern development: a study of the interplay between lateral inhibition, apoptosis and differential adhesion. Theor Biol Med Model. 2007;4:43. doi: 10.1186/1742-4682-4-43. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Raymond PA, Barthel LK. A moving wave patterns the cone photoreceptor mosaic array in the zebrafish retina. Int J Dev Biol. 2004;48(8-9):935–945. doi: 10.1387/ijdb.041873pr. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Raymond PA, Barthel LK, Rounsifer ME, Sullivan SA, Knight JK. Expression of rod and cone visual pigments in goldfish and zebrafish: a rhodopsin-like gene is expressed in cones. Neuron. 1993;10(6):1161–1174. doi: 10.1016/0896-6273(93)90064-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Raymond PA, Barthel LK, Stenkamp DL. The zebrafish ultraviolet cone opsin reported previously is expressed in rods. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 1996;37(5):948–950. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Raymond PA, Hitchcock PF. The teleost retina as a model for developmental and regeneration biology. Zebrafish. 2004;1(3):257–271. doi: 10.1089/zeb.2004.1.257. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Risner ML, Lemerise E, Vukmanic EV, Moore A. Behavioral spectral sensitivity of the zebrafish (Danio rerio) Vision Res. 2006;46(17):2625–2635. doi: 10.1016/j.visres.2005.12.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roberts MR, Srinivas M, Forrest D, de Escobar G Morreale, Reh TA. Making the gradient: thyroid hormone regulates cone opsin expression in the developing mouse retina. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2006;103(16):6218–6223. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0509981103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Robinson J, Schmitt EA, Harosi FI, Reece RJ, Dowling JE. Zebrafish ultraviolet visual pigment: absorption spectrum, sequence, and localization. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1993;90(13):6009–6012. doi: 10.1073/pnas.90.13.6009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stenkamp DL, Barthel LK, Raymond PA. Spatiotemporal coordination of rod and cone photoreceptor differentiation in goldfish retina. J Comp Neurol. 1997;382(2):272–284. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1096-9861(19970602)382:2<272::aid-cne10>3.0.co;2-u. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stenkamp DL, Cameron DA. Cellular pattern formation in the retina: retinal regeneration as a model system. Mol Vision. 2002;8:280–293. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stenkamp DL, Hisatomi O, Barthel LK, Tokunaga F, Raymond PA. Temporal expression of rod and cone opsins in embryonic goldfish retina predicts the spatial organization of the cone mosaic. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 1996;37(2):363–376. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Takechi M, Hamaoka T, Kawamura S. Fluorescence visualization of ultravioletsensitive cone photoreceptor development in living zebrafish. FEBS Lett. 2003;553(1-2):90–94. doi: 10.1016/s0014-5793(03)00977-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Takechi M, Kawamura S. Temporal and spatial changes in the expression pattern of multiple red and green subtype opsin genes during zebrafish development. J Exp Biol. 2005;208(Pt 7):1337–1345. doi: 10.1242/jeb.01532. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Takechi M, Seno S, Kawamura S. Identification of cis-acting elements repressing blue opsin expression in zebrafish UV cones and pineal cells. J Biol Chem. 2008;283(46):31625–31632. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M806226200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Takesue A, Mochizuki A, Iwasa Y. Cell-differentiation rules that generate regular mosaic patterns: modelling motivated by cone mosaic formation in fish retina. J Theor Biol. 1998;194(4):575–586. doi: 10.1006/jtbi.1998.0777. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Temple SE, Veldhoen KM, Phelan JT, Veldhoen NJ, Hawryshyn CW. Ontogenetic changes in photoreceptor opsin gene expression in coho salmon (Oncorhynchus kisutch, Walbaum) J Exp Biol. 2008;211(Pt 24):3879–3888. doi: 10.1242/jeb.020289. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Trimarchi JM, Harpavat S, Billings NA, Cepko CL. Thyroid hormone components are expressed in three sequential waves during development of the chick retina. BMC Dev Biol. 2008;8:101. doi: 10.1186/1471-213X-8-101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vega CJ, Peterson DA. Stem cell proliferative history in tissue revealed by temporal halogenated thymidine analog discrimination. Nat Methods. 2005;2(3):167–169. doi: 10.1038/nmeth741. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vihtelic TS, Doro CJ, Hyde DR. Cloning and characterization of six zebrafish photoreceptor opsin cDNAs and immunolocalization of their corresponding proteins. Vis Neurosci. 1999;16(3):571–585. doi: 10.1017/s0952523899163168. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Westerfield M. The zebrafish book. University of Oregon Press; Eugene: 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Wikler KC, Rakic P. Relation of an array of early-differentiating cones to the photoreceptor mosaic in the primate retina. Nature. 1991;351(6325):397–400. doi: 10.1038/351397a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.