Abstract

Diagnoses of prostatic carcinoma (PCa) have increased with widespread screening. While the use of α-methylacyl coA racemase (AMACR) and high-molecular-weight cytokeratins (HMCKs) have aided in distinguishing benign mimics from malignancy, their sensitivity and specificity are limited. We studied 6C4, a monoclonal antibody to glutamate receptor 2 (GluR2), an excitatory amino acid receptor subunit distributed throughout the central nervous system, on benign prostatic epithelium, high grade prostatic intra-epithelial neoplasia (HGPIN), and prostatic carcinoma. 10 cases with post-atrophic or adenosis-like prostate glands were also stained with PIN4 (Prostatic Intra-epithelial Neoplasia 4), an immunostain cocktail against AMACR, p63, and high molecular weight cytokeratin, in parallel with C64. Immunoreactivity for C64 was graded as negative (0-10%), +1 (11%-50%), and +2 (>50%). Malignant epithelium was classified by Gleason patterns. Gleason patterns 4 and 5 were subdivided into cribriform or non-cribriform type. Its utility in distinguishing post-atrophic or adenosis-like glands from prostate cancer, both of which show absence of basal cells on PIN4 immunostain, was also investigated. Our results revealed a statistically significant difference in staining of benign secretory prostatic epithelium, HGPIN, and low Gleason pattern carcinomas. The results also showed C64 is a sensitive marker in separating basal cell negative post-atrophic or adenosis-like glands from prostate carcinoma. Additionally, there was a statistically significant difference between staining of cribriform versus non-cribriform Gleason pattern 4 and 5 carcinomas. A limited number of lymph node metastases from cribriform and non-cribriform carcinomas were studied, and they stained the same as the primary tumor in the majority of cases. In conclusion, our preliminary data demonstrated potential diagnostic utility of C64 in the pathologic evaluation of prostatic carcinoma.

Keywords: Prostate cancer; 6C4, glutamate receptor 2; cribriform; high-grade prostatic intra-epithelial neoplasia; HGPIN; GluR2

INTRODUCTION

With the increasing public awareness of prostatic carcinoma (PCa), the widespread use of prostate-specific antigen (PSA) serum levels as a screening modality, and trans-rectal ultrasonography to target specific lesions, prostatic needle core biopsies (PNBX) have resulted in increased clinical detection of cancer. Pathologists are evaluating increased quantities of PNBX with fewer and smaller foci of PCa. Immunohistochemistry has emerged as a valuable aid in differentiating PCa from its benign mimics. Although there are increased diagnoses of prostate cancer, the majority of tumors will have indolent behavior. We studied the immunohistochemical staining of 6C4, a monoclonal antibody to glutamate receptor 2 (GluR2) on prostatic specimens. GluR2 is an excitatory amino acid receptor subunit distributed throughout the central nervous system with sites including the hippocampus, cortex, and spinal cord [1, 2, 3]. GluR2 is critical for the regulation of α-amino-3-hydroxy-5-methyl-4-isoxazolepropionic acid (AMPA) receptor properties as well as synaptic plasticity, however, its exact mechanisms are unclear [4]. In this paper, we explore the utility of 6C4 in the diagnosis of prostate carcinoma.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Tissue Samples

Specimens for this study consisted solely of tissue processed at the Mount Sinai Hospital pathology department. We studied 113 prostate carcinomas: 77% were PNBx, and 23% were radical prostatectomy specimens. Exclusion criteria included consult cases and cases with only benign tissue.

Analysis with 6C4

After deparaffinization and rehydration, slides were treated with 3% hydrogen peroxide (H2O2) to eliminate endogenous peroxidase activity, then processed for antigen retrieval with 10 mM citrate buffer pH 6.0 using a pressure cooker (Pascal; Dako Cytomation) for 4 minutes at 125°C, followed by slow cooling. All sections were rinsed with PBS (137 mM NaCl, 2.7 mM potassium chloride, 4.2 mM sodium phosphate, and 1.5 mM potassium phosphate)briefly. The sections were given a two-hour incubation with glutamate receptor subunit protein (GluR2) antibody (6C4; monoclonal), a gift of Dr. John H. Morrison (Department of Neuroscience, The Mount Sinai School of Medicine), at 0.8 microgram/ml diluted in 1% BSA and 5% normal goat serum in PBS at room temperture.UltraVision LP Detection System HRP Polymer & DAB Plus Chromogen (Thermo Fisher Scientific) was used as secondary antibody according to their manufacturer protocol. Immunoreactivity was visualized with diaminobenzadine (DAB), counterstained with hematoxylin, dehydrated, and mounted.

Two pathologists evaluated the immunohistochemical staining in each Gleason pattern of each PCa without knowledge at analysis of diagnosed Gleason pattern. Staining was estimated as a percentage for each Gleason pattern and specific morphologic variants. Staining was grouped as negative (0% to 10%), +1 (11% to 50%), and +2 (>50%). Cytoplasmic and membranous staining was considered positive immunostaining. Slides with differing estimations between the two pathologists were re-reviewed, and differences were resolved with consensus interpretation.

Immunohistochemical Staining with PIN4 (Prostatic Intra-epithelial Neoplasia 4) immunohistochemistry cocktail

Ten cases which contained post-atrophic or adenosis-like prostate glands were also stained with PIN4, in parallel with C64. The PIN4 cocktail consists of a polyclonal antibody against p504S (Biocare Medical, Concord, CT, USA) in a ready to use preparation in addition to a basal cell cocktail. The basal cell cocktail consists of an anti-cytokeratin 1, 5, 10, and 14 antibody (34βE12) as well as an anti-p63 antibody (4A4) (Ventana Medical Systems, Tucson, AZ, USA) in a ready to use preparation.

Statistical Analysis

The differences between groups were evaluated by the Fisher exact test. A P value < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

RESULTS

A total of 113 prostatic carcinomas were reviewed for 6C4 staining. Benign prostatic epithelium was also present in each case. All benign prostatic secretory epithelium showed immunoreactivity of virtually 100% for 6C4 antibody (Fig. 1). There were 35 HGPINs, all of which showed negative immunoreactivity (Fig. 2). Of the 59 Gleason pattern 3 prostate carcinomas, 57 showed negative immunoreactivity (Fig. 3), one showed +1 immunoreactivity, and one showed +2 immunoreactivity. Of the 41 non-cribriform Gleason pattern 4 carcinomas, 11 showed negative immunoreactivity, 19 showed +1 immunoreactivity, and 21 showed +2 immunoreactivity (Fig. 4). Among the ten Gleason pattern 5 non-cribriform carcinoma, four had negative immunoreactivity, none had +1 immunoreactivity, and six had +2 immunoreactivity (Fig.4). Cribriform variant of Gleason pattern 4 carcinoma was identified in 45 carcinomas, 43 of which showed negative immunoreactivity (Fig. 5), two which had +1 immunoreactivity, and none with +2 immunoreactivity. Gleason pattern 5 cribriform variant was identified in four carcinomas, 100% of which had negative immunoreactivity (Fig. 6). The immunoreactivity results of benign, HGPIN, cribriform, and non-cribriform PCa are summarized in Table 1. Two carcinomas had signet ring cell features. Both of these areas of signet ring features showed negative immunoreactivity. Also studied were eight prostatic carcinomas metastatic to lymph nodes. These metastases followed the trend of the primary carcinoma staining patterns. Six of eight had areas of cribriform carcinoma, which has negative immunoreactivity. Five of eight metastases had Gleason pattern 5 carcinoma. Of the five, two had negative immunoreactivity and three had +2 immunoreactivity.

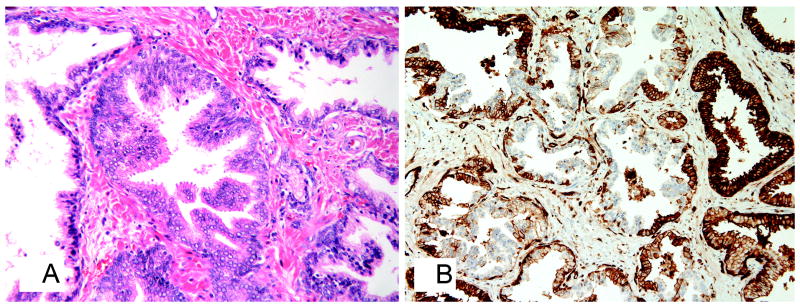

Figure 1.

Benign prostatic epithelium A. stained with H&E, original magnification x100; B. with strong (+2) membranous and cytoplasmic staining for 6C4 monoclonal antibody, immunostaining, original magnification x100.

Figure 2.

Micropapillary structures, large nuclei, and prominent nucleoli in HGPIN A. stained with H&E, original magnification x200; B. with focal immunoreactivity for 6C4 monoclonal antibody and uninvolved benign glands (far left and far right) with +2 membranous and cytoplasmic staining, immunostaining, original magnification x200.

Figure 3.

Small, crowded, angulated glands with intervening stroma of Gleason pattern 3 A. stained with H&E, original magnification x100; B. with negative immunostaining for 6C4 monoclonal antibody, immunostaining, original magnification x100.

Figure 4.

Fused, poorly-defined glands with occasional lumen formation (Gleason pattern 4) admixed with solid cords (Gleason pattern 5) non-cribriform PCa A. stained with H&E, original magnification x100; B. showing +2 membranous and cytoplasmic immunreactivity for 6C4 monoclonal antibody, immunostaining, original magnification x100.

Figure 5.

PCa with cribriform histology without necrosis A. stained with H&E, original magnification x100; B. showing negative immunostaining for 6C4 monoclonal antibody, immunostaining, original magnification x100.

Figure 6.

PCA with cribriform histology and intra-luminal necrosis A. stained with H&E, original magnification x100; B. showing negative immunostaining for 6C4 monoclonal antibody, immunostaining, original magnification x100.

Table 1.

6C4 Immunoreactivity in Prostatic Adenocarcinoma

| Negative (0-10%) | +1 (11-50%) | +2 (51-100%) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Benign | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | 113 (100%) |

| HGPIN | 35 (100%)* | 0 (0%)* | 0 (0%)* |

| Gleason 3 | 57 (97%)* | 1 (1%)* | 1 (1%)* |

| Gleason 4 or 5 cribriform | 47 (96%)* | 2 (4%)* | 0 (0%)* |

| Gleason 4 or 5 non-cribriform | 15 (25%)* | 19 (31%)* | 27 (44%)* |

P< 0.001 for benign in comparison with all non-benign, benign compared with HGPIN, gleason 3 PCa compared with the sum of all higher grade PCa, and Gleason 4+5 cribriform PCa compared with Gleason 4 or 5 non-cribriform PCa.

The post-atrophic or adenosis-like glands in the ten cases stained with PIN4 immunostain cocktail in parallel with C64 are shown in Figure 7. Briefly, post-atrophic glands with absence of basal cells on PIN4 immunostain displayed strongly positive reactivity with C64, supporting/confirming its benignity.

Figure 7.

Post-atrophic prostatic glands stained A. Cytologic atypia is appreciable in the glands (stained H&E, original magnification x100); B. These glands are weakly positive for α methyl acyl coA racemase and negative for basal cell markers including p63 and high molecular weight cytokeratin (immunostaining, original magnification x100); C. These glands are positive for C64 (immunostaining, original magnification x100).

DISCUSSION

Immunostaining in difficult cases has been used to distinguish benign from malignant prostate glands. A mainstay has been basal cell-associated markers including high molecular weigh cytokeratin (HMCK) 34βE12 as well as p63. While the absence of immunoreactivity supports carcinoma, benign diagnostic pitfalls that can have weak immunoreactivity include atrophy, atypical adenomatous hyperplasia, post-atrophic hyperplasia, nephrogenic adenoma, and mesonephric glandular hyperplasia [5, 6, 7].

To increase diagnostic accuracy, basal cell-associated markers are often used in conjunction with α-Methylacyl coA racemase (AMACR), which is positive in about 80% of PCa and high-grade prostatic intra-epithelial neoplasia (HGPIN) [8]. The positivity has its limitations in diagnosing PCa. AMACR may lack immunoreactivity in up to 30% of each of the following carcinoma variants: atrophic, foamy gland, and pseudohyperplastic [9].

AMACR may also be positive in benign prostatic secretory epithelium with results of up to 21% of benign prostatic epithelium staining positively for AMACR [8, 10, 11, 12].

In this study, strong immunopositivity for 6C4 was present in virtually 100% of benign prostatic epithelium while HGPIN and the large majority (97%) of low-grade invasive prostatic adenocarcinoma did not show any immunoreactivity.

The challenge urologic pathologists frequently face, particularly in biopsy specimens, is distinguishing benign glands from minute foci of prostatic cancer. It is not uncommon to see post-atrophic of adenosis-like prostatic glands present cytological atypia and negative immunostain for basal cells by high molecular weight cytokeratin and p63, which pose a diagnostic difficulty and might produce an ambiguous diagnosis. As shown in this study, the uniform positivity in benign glands, including post-atrophic and adenosis-type glands, readily separated them from prostate cancer with low Gleason’s score which are C64 negative, although both showed basal cell-negative in PIN4 immunostain. Therefore, C64 has a potential value in improving the diagnostic accuracy of prostate cancer, particularly in a subset of prostate biopsy specimens.

Additionally, as demonstrated in the table, there is a statistically significant difference in the staining pattern between cribriform and non-cribriform prostatic adenocarcinomas. While cribriform carcinomas lost immunoreactivity, non-cribriform pattern adenocarcinoma retained immunoreactivity. Rubin et al [13] found carcinomas with cribriform histology tend to present at a more advanced tumor stage than non-cribriform carcinoma and have higher tumor volume. In this study, of the cribriform carcinomas with known stage information, 81% presented at stage pT3 and 19% presented at pT2. It is possible that the loss of immunoreactivity in cribriform carcinoma may represent a genetic aberration. And thus, there may be a genotypic-phenotyic correlation in cribriform pattern PCa that lack of 6C4 expression potentially reflects.

Loss of 6C4 immunoreactivity was also found in signet ring cell PCa. Reviews of the literature on this variant have revealed that the prognosis of signet ring cell adenocarcinomas is comparable to high-grade adenocarcinomas carcinomas. [14, 15].

Future studies are needed to assess a correlation between these staining patterns and clinical follow-up. Also under current investigation are the potential uses of 6C4 for various other carcinomas. In conclusion, 6C4 is a potentially diagnostically useful immunohistochemical marker in improving the diagnostic accuracy, particularly in distinguishing prostatic carcinoma from benign diagnostic pitfalls. In terms of its prognostic value, further assessment is warranted.

Acknowledgments

This work was funded in part by National Institute of Health (NIH) grant #UL1 RR029887.

References

- 1.Siegel SJ, Janssen WG, Tullai JW, et al. Distribution of the excitatory amino acid receptor subunits GluR2(4) in monkey hippocampus and colocalization with subunits GluR5-7 and NMDAR1. J Neurosci. 1995;15(4):2707–2719. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.15-04-02707.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Vissavajjhala P, Janssen WG, Hu Y, et al. Synaptic distribution of the AMPA-GluR2 subunit and its colocalization with calcium-binding proteins in rat cerebral cortex: an immunohistochemical study using a GluR2-specific monoclonal antibody. Exp Neurol. 1996;142(2):296–312. doi: 10.1006/exnr.1996.0199. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Morrison BM, Janssen WG, Gordon JW, et al. Light and electron microscopic distribution of the AMPA receptor subunit, GluR2, in the spinal cord of control and G86R mutant superoxide dismutase transgenic mice. J Comp Neurol. 1998;395:523–534. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Zhou Z, Hu J, Passafaro M, et al. GluA2 (GluR2) Regulates Metabotropic Glutamate Receptor-Dependent Long-Term Depression through N-Cadherin-Dependent and Cofilin-Mediated Actin Reorganization. J Neurosci. 2011;31(3):819–833. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.3869-10.2011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Paner GP, Luthringer DJ, Amin MB. Best practice in diagnostic immunohistochemistry: prostate carcinoma and its mimics in needle core biopsies. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 2008;132(9):1388–1396. doi: 10.5858/2008-132-1388-BPIDIP. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Zhou M, Shah R, Shen R, et al. Basal cell cocktail (34betaE12 + p63) improves the detection of prostate basal cells. Am J Surg Pathol. 2003;27(3):365–371. doi: 10.1097/00000478-200303000-00010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Shah RB, Zhou M, LeBlanc M, et al. Comparison of the basal cell-specific markers, 34βE12 and p63, in the diagnosis of prostate cancer. Am J Surg Pathol. 2002;26(9):1161–1168. doi: 10.1097/00000478-200209000-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Beach R, Gown AM, Peralta-Venturina MN, et al. P504S immunohistochemical detection in 405 prostatic specimens including 376 18-gauge needle biopsies. Am J Surg Pathol. 2002;26:1588–1596. doi: 10.1097/00000478-200212000-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hameed O, Humphrey PA. Immunohistochemistry in diagnostic surgical pathology of the prostate. Semin Diagn Pathol. 2005;22(1):88–104. doi: 10.1053/j.semdp.2005.11.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Jiang Z, Woda BA, Rock KL, et al. P504S: a new molecular marker for the detection of prostate carcinoma. Am J Surg Pathol. 2001;25:1397–404. doi: 10.1097/00000478-200111000-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Jiang Z, Wu CL, Woda BA, et al. P504S/alpha-methylacyl-CoA racemase: a useful marker for diagnosis of small foci of prostatic carcinoma on needle biopsy. Am J Surg Pathol. 2002;26:1169–1174. doi: 10.1097/00000478-200209000-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Boran C, Kandirali E, Yilmaz F, et al. Reliability of the 34βE12, keratin 5/6, p63, bcl-2, and AMACR in the diagnosis of prostate carcinoma. Urol Oncol. 2010 doi: 10.1016/j.urolonc.2009.11.013. in process. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Rubin MA, de La Taille A, Bagiella E, et al. Cribriform carcinoma of the prostate and cribriform prostatic intraepithelial neoplasia: incidence and clinical implications. Am J Surg Pathol. 1998;22(7):840–848. doi: 10.1097/00000478-199807000-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Fujita K, Sugao H, Gotoh T, et al. Primary signet ring cell carcinoma of the prostate: report and review of 42 cases. Int J Urol. 2004;11(3):178–181. doi: 10.1111/j.1442-2042.2003.00763.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Warner JN, Nakamura LY, Pacelli A, et al. Primary signet ring cell carcinoma of the prostate. Mayo Clin Proc. 2010;85(12):1130–1136. doi: 10.4065/mcp.2010.0463. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]