Abstract

Background

Classification criteria for systemic sclerosis (SSc) are being updated jointly by ACR and EULAR. Potential items for classification were reduced to 23 using Delphi and Nominal Group Techniques. We evaluated the face, discriminant and construct validity of the items to be further studied as potential criteria.

Methods

Face validity was evaluated using the frequency of items in patients sampled from the Canadian Scleroderma Research Group, 1000 Faces of Lupus, the Pittsburgh, Toronto, Madrid and Berlin CTD databases. SSc (n=783) were compared to 1071 patients with diseases similar to SSc (mimickers): SLE (n=499), myositis (n=171), Sjögren’s syndrome (n=95), Raynaud’s phenomenon (RP) (n=228), MCTD (n=29), and idiopathic PAH (n=49). Discriminant validity was evaluated using odds ratios (OR). For construct validity, empiric ranking was compared to expert ranking.

Results

Compared to mimickers, SSc are more likely to have skin thickening (OR=427), telangiectasias (OR=91), anti-RNA polymerase III antibody (OR=75), puffy fingers (OR=35), finger flexion contractures (OR=29), tendon/bursal friction rubs (OR=27), anti-topoisomerase-I antibody (OR=25), RP (OR=24), finger tip ulcers/pitting scars (OR=19), anti-centromere antibody(OR=14), abnormal nailfold capillaries (OR=10), GERD symptoms (OR=8), and ANA, calcinosis, dysphagia, esophageal dilation (all OR=6), interstitial lung disease/pulmonary fibrosis (OR=5) and anti-PM-Scl antibody (OR=2). Reduced DLCO, PAH, and reduced FVC had OR<2. Renal crisis and digital pulp loss/acro-osteolysis did not occur in SSc mimickers (OR not estimated). Empiric and expert ranking were correlated (Spearman rho 0.53, p=0.01).

Conclusion

The candidate items have good face, discriminant and construct validity. Further item reduction will be evaluated in prospective SSc and mimicker cases.

Keywords: Systemic Sclerosis, Scleroderma, Classification Criteria, Validity, Bayesian

Systemic sclerosis (SSc) is a heterogeneous disease or possibly a family of closely related diseases characterized by vasculopathy, immune activation, and fibrosis. Its clinical manifestations vary across individuals, resulting in differences in organ system involvement, treatment regimens, and prognosis. In the absence of a diagnostic test for SSc, several sets of classification criteria have been developed and used to identify patients with similar features for recruitment into clinical studies.(1–4) The use of classification criteria as inclusion criteria for study participation has facilitated comparison of results across studies.

Existing classification criteria for SSc should be updated.(5–10) With improved understanding of the disease, the items regarded to be important for SSc have increased.(5, 11, 12) Goetz and Berne were among the first to describe gastrointestinal involvement in SSc, yet they did not incorporate this domain into their criteria.(13) It has also been recognized that use of the 1980 American Rheumatism Association (ARA) preliminary criteria(1–3) for recruitment into clinical trials results in the exclusion of up to 20% of patients with either early SSc or the limited cutaneous subtype of SSc.(8, 9, 14) The exclusion of the limited cutaneous SSc patients is likely due to the fact that a disproportionate number of diffuse cutaneous SSc patients were entered into the ARA prospective study. Thus the statistical analysis resulted in criteria that identified 100% of diffuse cutaneous SSc patients, but only 80% of limited cutaneous SSc patients. It has been demonstrated recently that the addition of nailfold capillary abnormalities and telangiectasias to the ARA SSc criteria improve their sensitivity.(6, 8)

Few criteria sets were developed for wide-scale application in classifying patients for clinical research studies.(15, 16) Most criteria sets were developed for use in the clinic or a study at hand, limiting their generalizability.(17, 18) Standards for devising classification criteria have evolved since the original criteria sets were proposed.(19) The methodologies used to develop previous criteria do not meet current standards.(20, 21) For example, one previous SSc criteria proposal utilized healthy subjects and rheumatoid arthritis patients as the comparator groups.(2) It has been argued that these patients are so different that they can nearly always be differentiated from SSc patients.(7) In keeping with the differential diagnosis faced by clinicians in practice, it has been suggested that criteria should be tested against control populations selected because they have SSc-like features.(7) Examples include other connective tissue diseases: mixed connective tissue disease (MCTD), Sjögren’s syndrome, systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE), dermatomyositis/polymyositis, undifferentiated CTD, other fibrosing syndromes (eosinophilic fasciitis, linear scleroderma, generalized morphea, scleromyxedema, nephrogenic systemic fibrosis), and Raynaud’s disease.

The Committee on Classification and Response Criteria, a subcommittee of the ACR Quality Measures Committee, has published recommendations for the development and validation of new criteria sets based on the current standards of measurement science,(19–21) which are complemented by recommendations from the European League Against Rheumatism (EULAR) Standing Committees of Clinical Epidemiology, and for International Studies Including Clinical Trials, respectively.(22, 23) Recommendations for modern criteria development include 1) collaboration between clinical experts and clinical epidemiologists in criteria development; 2) evaluation of the psychometric properties of each candidate criterion; and 3) description of the derivation sample (origin of the patients and control subjects), and gold standard.(21–23) Ideally, phases of criteria development should have a balance between expert opinion and data-driven methods.(21) Yet there should be avoidance of circularity of reasoning (a bias which can occur when the same experts developing the criteria are the ones contributing cases and comparison patients).(19) A joint international, collaborative initiative supported by EULAR and ACR is underway to develop revised classification criteria for SSc where the methodology has considered these issues.

During Phase 1 of the development process, potential items for revised SSc classification criteria were generated through two independent international consensus exercises performed by the Scleroderma Clinical Trials Consortium (SCTC) and the EULAR Scleroderma Trials and Research group (EUSTAR), resulting in a list of 168 potential items.(24) A Delphi exercise of 105 international SSc experts reduced the list of potential items to 102 items. The item list was again rated and subjected to a consensus meeting using nominal group technique by a separate group of European and North American SSc experts, further reducing the list to 23 items.(24) As recommended, the next phase of SSc criteria development requires evaluation of the psychometric properties of each candidate criterion.(21, 23) An important psychometric property of criteria is their validity – the degree to which their application corresponds to the truth. In this study we aimed to evaluate the validity of candidate items for revised SSc criteria. In particular, the objectives of this study were to evaluate the face, discriminant and construct validity of the candidate items. This knowledge will inform the subsequent phases of SSc criteria development.

METHODS

SSc patients and comparison subjects

SSc patients were identified from established, longitudinal cohorts that were not developed for the purpose of this study. Item definitions were often cohort specific and not necessarily identical between cohorts. Representatives of cohorts were invited to participate in this study based on geographic representation (North America and Europe), size, use of standardized data collection in both SSc and comparison patients, and willingness to participate. Comparison patients represented a spectrum of rheumatologic and non-rheumatologic diseases that share clinical manifestations with SSc. Patients with SSc that overlapped with another rheumatic disease were not included. In all cohorts, the diagnoses were based on the local center’s physican(s) judgment. Only a subset of each cohort was sampled (10% randomly selected from each database with the exception of the Pittsburgh cohort which was sampled by year) for this study, leaving the remainder available for future validation studies.

The Canadian Scleroderma Research Group (CSRG) database patients were compared with the 1000 Faces of Lupus database patients. Both are Canadian, multi-center cohorts which recruit patients from academic and community settings. The University of Pittsburgh Connective Tissue Disease Database, the Toronto Scleroderma Database and the Toronto Pulmonary Hypertension in the Connective Tissue Diseases Database, the Madrid Scleroderma cohort and the Berlin Scleroderma cohort are single-center, academic hospital based cohorts. SSc patients were compared to the patients who did not have SSc but had a disease similar to SSc (non-SSc comparisons), within each database. In the case of the CSRG patients and the 1000 Faces of Lupus patients, the items of interest were compared between the databases, where available.

Candidate items

The 23 candidate items were: anti-topoisomerase-I antibody; scleroderma (skin thickening on examination); abnormal nailfold capillary pattern; anticentromere antibody or centromere pattern on antinuclear antibody test; anti-RNA polymerase III antibody; finger tip and/or periungal ulcers or pitting scars; Raynaud’s phenomenon; interstitial lung disease or pulmonary fibrosis; renal crisis; reduced carbon monoxide diffusion capacity (DLCO); reduced forced vital capacity (FVC); dysphagia for solid food by history, esophageal dilation on radiograph, barium swallow or high resolution computerized tomography; telangiectasias; finger flexion contractures; antinuclear antibody (ANA); anti-PM-Scl antibody; pulmonary arterial hypertension; puffy fingers; digital pulp loss or acro-osteolysis; persistent, recurrent gastro-esophageal reflux disease (GERD) by history; calcinosis; and tendon or bursal friction rubs.(24) All items were defined using the local research protocols and harmonized across databases where possible. For example, DLCO and FVC abnormalities were defined as <70% or <80% predicted, depending on the cohort. The same definitions were applied for within group comparisons. These definitions can be found in the footnotes accompanying each table. Serologies were identified based on local laboratory assays. The response for each candidate item was dichotomized as present or absent.

Validity

Face validity is present if the items measure what they purport to measure.(25, 26) Typically this is assessed using expert judgment, but should be complemented by data driven methods.(26) Face validity was evaluated using the occurrence of positive responses to each item in patients with SSc. For items with a dichotomous response, this is the proportion of patients who give a positive response (having the item in question).(26) It is suggested that items with positive rates less than 20% may be eliminated.(26) When the majority of patients do not have the item, very little is gained by retaining the item in a criteria set. The item may not improve the psychometric properties of the criteria set and may actually detract from it by making it longer.(26) However, a low frequency item may still be retained if it confers other beneficial properties. For example, a low frequency item may differentiate SSc patients from mimicking conditions very well.

Discriminative validity of each item was evaluated using SSc patients and patients with a disease similar to SSc (non-SSc comparison patients) from the same centre. Using the positive rates, the odds ratio (OR) for each item was calculated, for each cohort separately and aggregated into a pooled OR. The candidate items were ranked from highest to lowest based on the pooled OR. It has been recommended that items with an OR less than 2 be eliminated.(27) In the setting of classification, OR greater than 2 provide better accuracy.(27)

Construct validity evaluates the relationship of the item to other measures that are believed to be part of the same phenomenon or ‘construct’.(28) In this study, construct validity was assessed using the strength of association between the empiric ranking based on the pooled OR and the ranking based on expert judgment from a previous Delphi exercise.(24)

Statistical analysis

Summary statistics were used to describe the data. Odds ratios (OR) were calculated to analyze the association between of each item with case or comparison status, for each cohort separately. Bayesian statistics were used to calculate the pooled mean OR and 95% credible interval (CrI). This approach was taken as it provides the reader the interval for which there is a 95% probability that the true OR falls within.(29) The Bayesian analyses used an uninformative normal prior distribution with mean 0 and variance 10,000; and Monte Carlo Markov Chain (MCMC) to sample from the posterior distribution of the items. Starting at 3 randomly generated initial values, the chains were run for a 5,000 iteration ‘burn-in’ period where the chain moved from the starting value toward the correct posterior distribution. The Brooks-Gelman-Rubin statistic was used to verify convergence at this point, that is, that all 3 chains were sampling from the same distribution. Then 10,000 new sampled values were collected and used to estimate the properties of the posterior distribution – OR and 95% CrI. Reporting of the analysis and results are in accordance with the ROBUST criteria.(33) The code for analyses is available from the authors upon request. The strength of association between the empiric ranking based on the pooled OR and the ranking based on expert judgment was analyzed using the Spearman’s rho rank correlation coefficient. Given variations between experts in their rankings, and variation in measurement of criteria across cohorts, we hypothesized a priori a ‘moderate’ correlation (rho 0.4 – 0.6) between the two rankings would be significant. Analyses were performed using R (version 2.2.1, The R Foundation for Statistical Computing) and WinBUGS (version 1.4.3, Imperial College and Medical Research Council, United Kingdom).

RESULTS

Patients and comparison subjects

Data on 783 SSc patients (CSRG n = 127, Pittsburgh cohort n = 326, Toronto cohort n = 86, Madrid cohort n = 175, Berlin cohort = 69) and 1071 comparison subjects were evaluated in this study. The comparison subjects included 499 SLE patients (1000 Faces of Lupus cohort n = 127, Pittsburgh cohort n = 113, Toronto cohort n = 36, Madrid cohort n = 223), 171 inflammatory myositis patients (Pittsburgh cohort n = 118, Madrid cohort n = 53), 95 Sjögren’s syndrome patients (Pittsburgh cohort), 228 Raynaud’s syndrome patients (Pittsburgh cohort n = 93, Madrid cohort n = 135), 29 mixed connective tissue disease patients (Toronto cohort), and 49 idiopathic pulmonary arterial hypertension patients (Toronto cohort).

Face Validity

Rates of positive responses for the candidate items in each SSc cohort are summarized in Tables 1 – 5. The presence of renal crisis and digital pulp loss or acroosteolysis each occurred in less than 20% in all cohorts, where measured. Anti-topoisomerase-I antibody, anti-PM-Scl antibody, calcinosis, reduced FVC, pulmonary arterial hypertension, and finger flexion contractures variably had positive occurrence frequencies less than 20%, depending on the cohort. The other candidate items were consistently positive in >20% of SSc patients.

Table 1.

Frequency of positive responses and odds ratios for candidate items in the Canadian Scleroderma Research Group and 1000 Faces of Lupus Cohorts.

| Criterion | Scleroderma N = 127 |

SLE N = 127 |

ORf |

|---|---|---|---|

| Abnormal nailfold capillary pattern | 93/126 (74%) | NA | NA |

| Anti-centromere antibody | 32/109 (29%) | 1/126 (0.8%) | 52 |

| Anti-topoisomerase-I antibody | 18/103 (17%) | 1 (0.8%) | 27 |

| Antinuclear antibody | 101/109 (93%) | 125 (98%) | 0.2 |

| Anti-PM-Scl antibody | 9/80 (11%) | NA | NA |

| Anti-RNA polymerase III antibody | 15/83 (18%) | NA | NA |

| Calcinosis | 43/125 (34%) | NA | NA |

| Reduced DLCOa | 51/106 (48%) | NA | NA |

| Digital pulp loss or acro-osteolysis | 55/124 (44%) | 0 (0%) | NE |

| Dysphagia for solids | 74/116 (64%) | NA | NA |

| Esophageal dilation | 14/125 (11%) | NA | NA |

| Finger flexion contractures | 37 (29%) | NA | NA |

| Finger tip ulcers or pitting scars | 76/126 (60%) | 2/126 (2%) | 94 |

| Reduced FVCb | 8/90 (9%) | NA | NA |

| Interstitial lung disease or pulmonary fibrosisc | 44/122 (36%) | 1/125 (0.8%) | 66 |

| Gastro-esophageal reflux diseased | 106/126 (84%) | NA | NA |

| Puffy fingers | 65/125 (52%) | NA | NA |

| Pulmonary arterial hypertensione | 8/107 (7%) | 3/124 (2%) | 3 |

| Raynaud phenomenon | 123 (97%) | 56 (44%) | 39 |

| Renal crisis | 6/126 (5%) | NA | NA |

| Scleroderma skin changes | 118/124 (95%) | NA | NA |

| Telangiectasias | 90/119 (76%) | 0 (0%) | NE |

| Tendon or bursal friction rubs | 18/125 (14%) | NA | NA |

NA Not available, SLE Systemic lupus erythematosus, NE Not estimated

Notes:

DLCO Carbon monoxide diffusion capacity, DLCO < 70% predicted

FVC Forced vital capacity; FVC < 70% predicted

ILD (CSRG data): ILD was considered present if a HRCT lung was interpreted by an experienced radiologist as showing interstitial lung disease or, in the case where no HRCT was performed, if either a chest x-ray was reported as showing either increased interstitial markings (not thought to be due to congestive heart failure) or fibrosis, and/or if a study physician reported findings indicative of ILD on physical examination.

Gastro-esophageal reflux disease was defined as the patient having reported a history of heartburn, regurgitation of acid, and/or nocturnal choking, and/or ever taking gastroprotective agents.

Pulmonary hypertension was defined as an estimated systolic pulmonary artery systolic pressure > 45 mmHg (CSRG data)

Odds Ratios can be read as SSc patients have OR times the odds of having candidate criteria than a mimicker patient

Table 5.

Frequency of positive responses for candidate items in the Berlin cohort.

| Criterion | Scleroderma N = 69 |

|---|---|

| Abnormal nailfold capillary pattern | NA |

| Anti-centromere antibody | 19 (28%) |

| Anti-topoisomerase-I antibody | 15 (22%) |

| Antinuclear antibody | 63 (91%) |

| Anti-PM-Scl antibody | 3 (4%) |

| Anti-RNA polymerase III antibody | 4 (6%) |

| Calcinosis | NA |

| Reduced DLCOa | 53 (77%) |

| Digital pulp loss or acro-osteolysis | NA |

| Dysphagia for solids | 47 (68%) |

| Esophageal dilation | NA |

| Finger flexion contractures | 32 (46%) |

| Finger tip ulcers or pitting scars | 22 (32%) |

| Reduced FVCb | 26 (38%) |

| Interstitial lung disease or pulmonary fibrosis | 31 (45%) |

| Gastro-esophageal reflux disease | 52 (75%) |

| Puffy fingers | NA |

| Pulmonary arterial hypertensionc | 25 (36%) |

| Raynaud phenomenon | 61 (88%) |

| Renal crisis | 3 (4%) |

| Scleroderma | 56 (81%) |

| Telangiectasias | NA |

| Tendon or bursal friction rubs | 8 (12%) |

NA Not available

Notes:

DLCO Carbon monoxide diffusion capacity; DLCO < 80%

FVC Forced vital capacity; FVC< 80%

Discriminant validity

The ORs for candidate items, comparing SSc to non-SSc comparison patients, are summarized in Tables 1– 4. The pooled mean OR and 95% CrI for the candidate items are presented in Table 6. Pulmonary arterial hypertension (OR 1.9, 95% CrI 1.4 – 2.4), reduced DLCO (OR 1.5, 95% CrI 1.1 – 2.0), and reduced FVC (OR 0.9, 95% CrI 0.6 – 1.3) had ORs less than 2. Renal crisis and digital pulp loss or acro-osteolysis did not occur in any of the non-SSc comparison patients in any of the cohorts and consequently the OR were not estimated. If an infinitely small numeric adjustment were added to facilitate estimation, the result would be an infinitely large odds ratio.

Table 4.

Frequency of positive responses and odds ratios for candidate items in the Madrid cohort.

| Criterion | Scleroderma N = 175 |

Non-SSc comparisons | Combined Non-SSc comparisons |

OR | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| SLE N = 223 |

Myositisa N = 53 |

Raynaud’s Disease N = 135 |

N = 411 | |||

| Abnormal nailfold capillary pattern | 113/137 (83%) | NA | NA | 3 (2%) | 3/135 | NAb |

| Anti-centromere antibody | 45/167 (27%) | 3/203 (2%) | 1 (2%) | 1 (1%) | 5/391 | 28 |

| Anti-topoisomerase-I antibody | 59/167 (35%) | 2/103 (1%) | 1/53 (2%) | 0 (0%) | 3/291 | 24 |

| Antinuclear antibody | 158/169 (94%) | 197/203 (97%) | 25/49 (47%) | 18 (13%) | 240/387 | 9 |

| Anti-PM-Scl antibody | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA |

| Anti-RNA polymerase III antibody | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA |

| Calcinosis | 10/56 (18%) | NA | 5/53 (9%) | 0 (0%) | 5/188 | 8 |

| Reduced DLCOb | 55/93 (59%) | NA | 12/38 (32%) | NA | 12/38 | 3 |

| Digital pulp loss or acro-osteolysis | 21/48 (25%) | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA |

| Dysphagia for solids | NA | NA | 17/53 (32%) | NA | 17/53 | NA |

| Esophageal dilation | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA |

| Finger flexion contractures | 23/123 (19%) | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA |

| Finger tip ulcers or pitting scars | 77/173 (45%) | NA | 6/53 (11%) | 3 (2%) | 9/188 | 16 |

| Reduced FVCc | 24/95 (25%) | NA | 20/44 (46%) | NA | 20/44 | 0.4 |

| Interstitial lung disease or pulmonary fibrosis | 49/173 (28%) | 7/54 (13%) | 18/48 (38%) | 1/135 (1%) | 26/237 | 3 |

| Gastro-esophageal reflux disease | 115/174 (66%) | NA | 16/52 (31%) | 5 (4%) | 21/187 | 15 |

| Puffy fingers | 73/124 (59%) | NA | NA | 9 (7%) | 9/135 | 20 |

| Pulmonary arterial hypertension | 36/170 (21%) | 3/223 (2%) | 2/52 (4%) | NA | 5/275 | 14 |

| Raynaud phenomenon | 168/174 (97%) | 30/60 (50%) | 14/52 (27%) | 135 (100%) | 179/247 | 14 |

| Renal crisis | 13/174 (8%) | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | 0 | NE |

| Scleroderma skin changes | 154 (88%) | 2/200 (1%) | NA | 4 (3%) | 6/335 | 402 |

| Telangiectasias | 31/65 (48%) | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA |

| Tendon or bursal friction rubs | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA |

NA Not available, SLE Systemic lupus erythematosus, OR Odds ratio, NE Not Estimated

Notes:

Patients with inflammatory myopathy fulfilling criteria of Bohan and Peter, excluding those with overlap myopathy with systemic sclerosis or SLE

DLCO Carbon monoxide diffusion capacity, DLCO < 70% predicted

FVC Forced vital capacity; FVC < 70% predicted

Table 6.

Pooled odds ratios and ranking of candidate criteria.

| Criterion | Pooled mean OR (95% CrI) |

Empiric ranking |

Expert based ranking |

|---|---|---|---|

| Renal crisis | NE | 1ab | 9 |

| Digital pulp loss or acro-osteolysis | NE | 1ab | 13b |

| Scleroderma skin changes | 426.7 (256.5, 691.2) | 2 | 1 |

| Telangiectasias | 91.4 (57.6, 154.5) | 3 | 11 |

| Anti-RNA polymerase III antibody | 75.4 (13.2, 312.6) | 4 | 6 |

| Puffy fingers | 34.9 (24.0, 49.2) | 5 | 12 |

| Finger flexion contractures | 29.0 (17.8, 46.2) | 6 | 19 |

| Tendon or bursal friction rubs | 26.81 (2.4, 91.9) | 7 | 10 |

| Anti-topoisomerase-I antibody | 24.9 (12.7, 48.0) | 8 | 2 |

| Raynaud phenomenon | 24.1 (15.3, 37.5) | 9 | 7 |

| Finger tip ulcers or pitting scars | 19.3 (12.7, 28.8) | 10 | 5 |

| Anti-centromere antibody | 13.8 (9.0, 21.0) | 11 | 3 |

| Abnormal nailfold capillary pattern | 10.4 (6.9, 15.1) | 12 | 4 |

| Gastro-esophageal reflux disease | 7.6 (5.9, 9.7) | 13 | 17 |

| Antinuclear antibody | 6.06 (4.1, 8.8) | 14 | 13b |

| Calcinosis | 6.05 (3.4, 10.5) | 15 | 18 |

| Dysphagia | 5.7 (4.2, 7.7) | 16 | 19 |

| Esophageal dilation | 5.6 (2.9, 10.2) | 17 | 14 |

| Interstitial lung disease or pulmonary fibrosis | 4.5 (3.4, 5.8) | 18 | 8 |

| Anti-PM-Scl antibody | 2.4 (1.9, 7.1) | 19 | 20b |

| Pulmonary arterial hypertension | 1.2 (0.9, 1.5) | 20 | 15 |

| Reduced DLCO | 1.5 (1.1, 2.0) | 21 | 16 |

| Reduced FVC | 0.9 (0.6, 1.3) | 22 | 20b |

CrI Credible Interval, NE Not estimated, DLCO Carbon monoxide diffusion capacity, FVC Forced vital capacity

Renal crisis, digital pulp loss or acro-osteolysis did not occur in any mimicker patients, therefore odds ratios were not estimated. An infinitely small numeric adjustment would result in an infinitely large odds ratio.

Tied rankings

Some of the Raynaud’s syndrome patients from the Pittsburgh cohort had the presence of antinuclear antiboidies, abnormal nailfold capillaries and positive serology suggesting that they may represent pre-SSc or pre-other connective tissue diseases. The pooled OR analysis was repeated excluding these patients, and there was no substantial difference in the results.

Construct validity

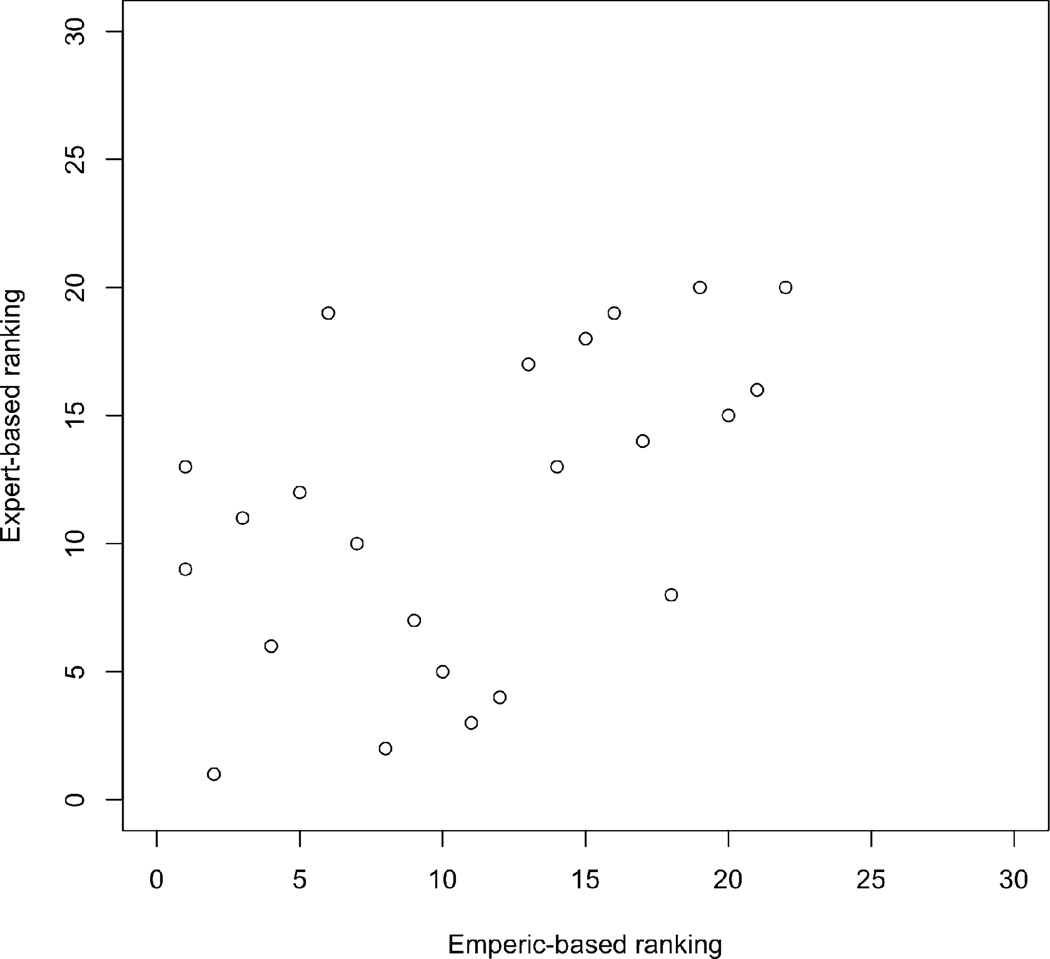

The empiric-based and expert-based ranking of the candidate criteria are presented in Table 6. There was moderate correlation between the 2 rankings with a Spearman rho 0.53, p = 0.01. Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Scatter plot of the empiric-based ranking and the expert-based ranking of the candidate items. The correlation between the 2 rankings was Spearman rho 0.53, p=0.01.

DISCUSSION

Evaluation of the validity of candidate SSc items is an important and necessary phase of classification criteria development. Our results demonstrate that the candidate SSc items are valid – they have good face, discriminant and construct validity. Our study results also provide valuable insights that should be considered in the subsequent phases of criteria development which will include: collecting item frequencies on SSc and mimickers at multiple sites in North America and Europe, using programs for item reduction, and then testing the validity of final criteria in databases.

When there is face validity, motivation, cooperation and satisfaction among classification criteria users increases.(26) The demonstration of face validity requires more than peer judgments; empirical evidence is also required to show that a criterion is measuring what is intended.(26) In the case of SSc, this has an important pragmatic implication. A proportion of SSc patients (approximately 20%) who have the disease have been excluded from participation in some clinical trials as they do not meet existing classification criteria. This is a problem when a rare disease is being studied and a significant minority is excluded.(6, 9) It has been argued that important domains of the disease have been left out of previous criteria (such as antibodies and vascular complications). If the revised SSc classification criteria incorporate items that improve the specificity of the criteria, then more SSc patients can be included into studies from which they may derive a benefit. In this study, the majority of candidate items have excellent face validity with endorsement frequencies greater than 20%. Renal crisis, finger pulp loss or acro-osteolysis, anti-topoisomerase-I antibody, anti-PM-Scl antibody, calcinosis, reduced forced vital capacity, pulmonary arterial hypertension, and finger flexion contractures had lower endorsement frequencies. The value of retaining these candidate criteria will need to be carefully evaluated in the next phase of criteria development. It is uncertain if combining uncommon features in revised SSc classification criteria would improve the sensitivity and/or specificity. The utility of criteria with negative responses will also need to be considered. There could be criteria where a negative response makes SSc unlikely (such as absence of ANA or Raynaud’s phenomenon). Furthermore, the value of including criteria that rarely occur in SSc patients will need to be balanced by the impact of including too many criteria on the feasibility and reliability the final criteria set. If a criterion is irrelevant, then users may omit it.(26)

The majority of candidate criteria have excellent discriminant validity with high pooled odds ratios. They effectively discriminate patients with SSc from non-SSc comparison patients included in this study. The utility of a few candidate criteria will require added scrutiny in the next phase of criteria development. Renal crisis and digital pulp loss or acro-osteolysis occur uncommonly in SSc. However, they had the strongest discriminating ability, as they never occurred in any of the non-SSc comparison patients in any of the cohorts. These criteria are very good at discriminating patients with SSc from patients with other diseases. Criteria that are rare but unique to SSc may be very specific for ruling in the disease, but do not assist in the objective of being more inclusive of those with the disease. Pulmonary arterial hypertension, reduced DLCO and reduced FVC had OR<2, indicating a weak discriminating ability. The value of retaining these items will need to be evaluated.

The candidate criteria also had good construct validity. There was good agreement between the empiric-based ranking and the expert-based ranking of the importance of the candidate items. Both methods highlight those criteria that should be considered very important and those that can be considered less important in criteria set development. In this case, the empiric data complements and verifies the expert based data, indicating that criteria development is evolving in the right direction.

This study has a number of strengths. First, our validation study has used large numbers of patients (for an uncommon disease). It has been recommended that a sample size of at least 50 patients be used to evaluate the frequency of an item.(26) Other criteria sets have been criticized for using inadequate numbers of patients and controls.(21, 23) The comparator groups reflect other connective tissue diseases, comparisons with non-rheumatic diseases and non-rheumatology settings.(21, 23) Patients included in this study were recruited from multiple sites in North America and Europe. Previous SSc criteria development did not have such broad geographic representation.(14) Experts involved in generating the candidate criteria were different than those supplying patients (with exception of 1 expert, TAM), thereby reducing potential bias from circularity of reasoning.(21, 23)

There are limitations to consider in the interpretation of this study. One limitation to consider is missing data. This is partially related to the fact that data were not collected specifically for this study, but rather had been previously collected for other purposes. As a result, not all sites collect the same variables. To overcome this challenge, we included multiple sites so that there were sufficient data to evaluate each candidate criterion. Not all sites categorized the variable in the same manner in which the candidate criteria have been proposed. This has introduced some variability in comparisons across sites. However, the same definition for each criterion was applied for within-site comparisons. Furthermore, despite the variability in definitions of items across sites, we were able to demonstrate moderate correlation between the empiric and expert rankings. Many sites were academic medical centers. However, the CSRG and 1000 Faces of Lupus databases enroll patients from both academic and community sites, so the generalizability to other non-academic practices is likely present (especially due to the fact that the ORs were similar among the various databases used for this study).

The ethnic background of patients was not evaluated in this study. There may be an over-representation of Caucasian patients. Given variations in the frequency of specific criteria (e.g. autoantibodies, lung disease) across ethnic groups, this may affect the external validity of the developed criteria.(30) In this study, there is some ethnic variation across databases we used. The Pittsburgh cohort includes African-American patients.(31) The 1000 Faces of Lupus database includes Asian and First Nations and African-American patients.(32) The Toronto cohort includes African-American and Asian (East Asian and South-East Asian) patients.(33) Subsequent phases of criteria development will need to consider the performance of classification criteria in different ethnic groups.

A potential limitation is that the investigators ascertaining the criteria knew the diagnoses. Criteria were evaluated based on local research protocols or local standard of care. This may introduce verification bias. Verification bias occurs when disease status is not determined in all subjects who are evaluated for a criteria and when the probability of verification depends on the criteria result and/or other clinical variables. When verification of disease status is more likely among patients with positive criteria, a bias is introduced that can increase the sensitivity of the criteria and reduce its specificity.(34) In our study, the majority of SSc patients underwent evaluation of all criteria (e.g. echocardiogram and pulmonary function tests). However, in the case of SSc comparator patients, evaluation of many of the criteria is not routinely done in asymptomatic patients and even in symptomatic patients; performing invasive tests such as right heart catheterization or high resolution CT thorax scans may not be done on mimickers as often as SSc patients. Subsequent phases of criteria development may need to consider design or analytic techniques to account for verification bias.(34) It would not be likely that within a database the investigators did not have a working definition of the disease(s) studied but the criteria used to make the diagnosis may have been formal criteria or expert opinion. A future prospective data collection that compares patients with SSc and mimickers may reduce this bias when cases are then re-analyzed by experts blinded to the diagnosis.

Our study results provide sufficient fidelity to justify proceeding with the next phase of criteria development, which is prospective case and control ascertainment. During the next phase, the same definitions of items will be applied to all patients, and multiple sites will test each item. Given the high discriminating ability of the items using the non-SSc comparisons in this study (e.g. SLE), the next phase of development should include non-SSc comparisons that more closely resemble SSc such as eosinophilic fasciitis, generalized morphea and nephrogenic systemic fibrosis. During the next phase, the scaling of the criteria will need to be considered. The criteria could be additive (e.g. SLE classification criteria(35, 36)), hierarchical (e.g. 1980 SSc classification criteria(2, 3)) or weighted (e.g. rheumatoid arthritis classification criteria(37)).

In conclusion, our study has demonstrated that the candidate SSc items have good face, discriminant and construct validity. These items should be tested in the next phases of SSc classification development.

Table 2.

Frequency of positive responses and odds ratios for candidate items in the University of Pittsburgh Connective Tissue Disease cohort.

| Criterion | Scleroderma N = 326 |

Non-SSc comparisons | Combined Non- SSc comparisons |

ORj | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

SLE N =113 |

PM/DM N = 118 |

SJOG N = 95 |

Raynaud’s Disease |

||||

| Abnormal nailfold capillary pattern | 18/26 (69%) | NA | 21/42 (50%) | 3/5 (60%) | 20/36 (56%) | 44/83 (53%) | 2 |

| Anti-centromere antibody | 95/313 (21%) | 2/110 (2%) | 1/82 (1%) | 2/51 (4%) | 11/84 (13%) | 16/327 (5%) | 8 |

| Anti-topoisomerase-I antibody | 63/313 (19%) | NA | 0/82 (0%) | 0/51 (0%) | 4/84 (5%) | 4/217 | 18 |

| Antinuclear antibody | 298/313 (98%) | 64/72 (89%) | 60/82 (74%) | 35/51 (69%) | 63/84 (75%) | 222/289 | 6 |

| Anti-PM-Scl antibody | 9/313 (3%) | NA | 2/82 (2%) | 0/51 (0%) | 1/84 (1%) | 3/217 | 2 |

| Anti-RNA polymerase III antibody | 81/313 (25%) | NA | 1/82 (1%) | 0/51 (0%) | 0/84 (0%) | 1/217 | 75 |

| Calcinosis | 35/241 (15%) | NA | 6/75 (8%) | 1/15 (7%) | 0/36 (0%) | 7/126 | 3 |

| Reduced DLCOa | 118/190 (62%) | 2/7 (29%) | 44/59 (75%) | 2/11 (18%) | 6/14 (43%) | 54/91 | 1 |

| Digital pulp loss or acro-osteolysisb | 12/125 (10%) | NA | 0/18 (0%) | 0/11 (0%) | 0/9 (0%) | 0/38 | NC |

| Dysphagia for solids | 139/325 (43%) | 6/106 (6%) | 23/117 (20%) | 15/95 (16%) | 14/93 (15%) | 58/411 | 10 |

| Esophageal dilationc | 106/163 (65%) | NA | 5/19 (26%) | 6/25 (24%) | 6/23 (26%) | 17/67 | 5 |

| Finger flexion contracture | 203/324 (63%) | 8/112 (7%) | 5/117 (4%) | 7/95 (7%) | 3/92 (3%) | 23/416 | 29 |

| Finger tip ulcers or pitting scars | 149/324 (46%) | 4/107 (4%) | 2/116 (2%) | 1/95 (1%) | 12/92 (13%) | 19/410 | 18 |

| Reduced FVCd | 61/204 (30%) | NA | 25/62 (40%) | 0/12 (0%) | 3/15 (20%) | 28/89 | 0.9 |

| Interstitial lung disease or pulmonary fibrosise | 106/259 (41%) | 1/50 (2%) | 40/71 (56%) | 4/46 (9%) | 2/30 (7%) | 47/197 | 2 |

| Gastro-esophageal reflux diseasef | 234/325 (72%) | 28/106 (26%) | 39/117 (33%) | 30/95 (32%) | 37/93 (40%) | 134/411 | 16 |

| Puffy fingers | 285/325 (88%) | 14/111 (13%) | 12/117 (10%) | 8/95 (8%) | 13/92 (14%) | 47/415 | 56 |

| Pulmonary arterial hypertensiong | 28/326 (9%) | 3/113 (3%) | 2/118 (2%) | 0/95 (0%) | 1/93 (1%) | 6/419 | 6 |

| Raynaud’s phenomenon | 318/326 (98%) | 67/113 (59%) | 44/117 (38%) | 42/95 (44%) | 93/93 (100%) | 246/418 | 47 |

| Renal crisis | 22/326 (7%) | 0/113 (0%) | 0/118 (0%) | 0/95 (0%) | 0/93 (0%) | 0/419 | NA |

| Scleroderma | 314/326 (96%) | 1/93 (1%) | 7/109 (6%) | 0/92 (0%) | 0/92 (0%) | 8/386 | 1190 |

| Telangiectasiash | 180/325 (55%) | 2/107 (2%) | 1/115 (1%) | 8/95 (8%) | 2/92 (2%) | 13/409 | 38 |

| Tendon or bursal friction rubsi | 95/323 (29%) | 0/75 (0%) | 0/111 (0%) | 1/91 (1%) | 0/90 (0%) | 1/367 | 153 |

NA Not Available, SLE Systemic lupus erythematosus, PM/DM Polymyositis or Dermatomyositis, SJOG Sjögren syndrome, OR Odds ratio, NE Not Estimated

Notes:

DLCO Carbon monoxide diffusion capacity, DLCO < 70% predicted

Acroosteolysis on physical examination or radiographically

Esophageal dysmotility by barium swallow or manometry

FVC Forced vital capacity; FVC < 70% predicted

Pulmonary fibrosis radiographically

Heartburn by history

Pulmonary arterial hypertension by clinical features (physical examination, echocardiogram) or right heart catheterization

Telangiectasias at any site which are believed due to connective tissue disease finger contractures recorded by the examining physician on physical exam and, separately

1 or more rubs, including the following sites; shoulders, olecranon bursae, wrists (flexor or extensors), fingers (flexor or extensor), knees, ankles (Achilles, peroneal, posterior tibial, or anterior tibial tendons)

Odds Ratios can be read as SSc patients have OR times the odds of having candidate criteria than a mimicker patient

Table 3.

Frequency of positive responses and odds ratios for candidate items in the Toronto cohorts.

| Criterion | Scleroderma N = 86 |

Non-SSc comparisons | Combined Non-SSc comparisons |

ORe | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| SLE N = 36 |

MCTD N = 29 |

IPAH N= 49 |

N = 114 |

|||

| Abnormal nailfold capillary patterna | 31 (36%) | 0 (0%) | 4 (14%) | 0 (0%) | 4% | 16 |

| Anti-centromere antibody | 14 (16%) | 0 (0%) | 4 (14%) | 0 (0%) | 4% | 5 |

| Anti-topoisomerase-I antibody | 15 (17%) | 1 (3%) | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | 0.9% | 24 |

| Antinuclear antibody | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA |

| Anti-PM-Scl antibody | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA |

| Anti-RNA polymerase III antibody | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA |

| Calcinosis | 23 (27%) | 0 (0%) | 3 (10%) | 0 (0%) | 3% | 14 |

| Reduced DLCOb | 30 (35%) | 13 (36%) | 15 (52%) | 17 (35%) | 39% | 0.8 |

| Digital pulp loss or acro-osteolysis | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA |

| Dysphagia or Gastro-esophageal reflux disease | 71 (83%) | 4 (11%) | 20 (69%) | 0 (0%) | 21% | 18 |

| Esophageal dilation | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA |

| Finger flexion contractures | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA |

| Finger tip ulcers or pitting scars | 28 (33%) | 1 (3%) | 7 (24%) | 0 (0%) | 7% | 6 |

| Reduced FVCc | 11 (13%) | 5 (14%) | 8 (28%) | 4 (8%) | 15% | 0.8 |

| Interstitial lung disease or pulmonary fibrosis | 32 (37%) | 6 (17%) | 15 (52%) | 1 (2%) | 19% | 3 |

| Gastro-esophageal reflux disease | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA |

| Puffy fingers | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA |

| Pulmonary arterial hypertensiond | 27 (31%) | 36 (100%) | 22 (76%) | 49 (100%) | 94% | 0.03 |

| Raynaud’s phenomenon | 83 (97%) | 15 (42%) | 26 (90%) | 3 (6%) | 39% | 44 |

| Renal crisis | 6 (7%) | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | 0% | NE |

| Scleroderma | 83 (97%) | 0 (0%) | 15 (52%) | 0 (0%) | 13% | 183 |

| Telangiectasias | 71 (83%) | 0 (0%) | 11 (38%) | 0 (0%) | 10% | 44 |

| Tendon or bursal friction rubs | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA |

NA Not Available, SLE Systemic lupus erythematosus, MCTD Mixed Connective Tissue Disease, IPAH Idiopathic pulmonary arterial hypertension, OR Odds ratio, NE Not Estimated

Notes:

Abnormal nailfold capillaries with enlargement or dropout by visual inspection or ophthalmascope

DLCO Carbon monoxide diffusion capacity, DLCO < 70% predicted

FVC Forced vital capacity; FVC < 70% predicted

Mimicker patients come from the pulmonary hypertension database resulting in a high frequency of pulmonary hypertension within one cohort. The results presented are thus conservative.

Odds Ratios can be read as SSc patients have OR times the odds of having candidate criteria than a mimicker patient.

Significance and Innovation.

The candidate items for systemic sclerosis classification criteria have good face, discriminant and construct validity

This study reflects a joint collaboration between the ACR and EULAR, involved a large number of connective tissue disease patients, that were recruited from multiple sites in North America and Europe.

The results justify proceeding with the next phase of criteria development, which is prospective case and control ascertainment.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

This research was supported by the American College of Rheumatology (ACR) Classification and Response Criteria Subcommittee of the Committee on Quality Measures and the European League Against Rheumatism (EULAR).

Dr. Johnson is supported by a Canadian Institutes of Health Research Clinician Scientist Award and the Norton-Evans Fund for Scleroderma Research. Dr. Khanna was supported by the Scleroderma Foundation (New Investigator Award), and a National Institutes of Health Award (NIAMS K23 AR053858-05).

The authors thank Dr. Hector Arbillaga, Dr. Mike Oliver Becker, Dr. Sasha Bernatsky, Mr. Ashley Bonner, Dr. Gaelle Chedéville, Dr. Ann Clarke, Dr. Peter Docherty, Dr. Paul R. Fortin, Dr. Marvin Fritzler, Dr. Dafna Gladman, Dr. John Granton, Dr. Tamara Grodzicky, Dr. Carol A. Hitchon, Dr. Adam Huber, Dr. Marie Hudson, Dr. H. Niall Jones, Dr. Elzbieta Kaminska, Dr. Nadir Khalidi, Dr. Peter Lee, Dr. Sophie Ligier, Dr. Janet Markland, Dr. Ariel Masetto, Dr. Jean-Pierre Mathieu, Dr. Ross Petty, Dr. Christian Pineau, Dr. Suzanne Ramsey, Dr. David Robinson, Dr. Earl Silverman, Dr. C. Douglas Smith, Dr. Virginia Steen, Dr. Evelyn Sutton, Dr. J. Carter Thorne, Dr. Lori Tucker, Dr. Murray Urowitz, Dr. Michel Zummer for their assistance with this study.

Footnotes

DISCLOSURES

Sindhu R. Johnson has no financial or other conflicts of interest in relation to this manuscript.

Jaap Fransen has no financial or other conflicts of interest in relation to this manuscript.

Dinesh Khanna has no financial or other conflicts of interest in relation to this manuscript.

Murray Baron has no financial or other conflicts of interest in relation to this manuscript.

Frank van den Hoogen has no financial or other conflicts of interest in relation to this manuscript.

Thomas A. Medsger Jr. has no financial or other conflicts of interest in relation to this manuscript.

Christine A. Peschken has no financial or other conflicts of interest in relation to this manuscript.

Patricia E. Carreira has no financial or other conflicts of interest in relation to this manuscript.

Gabriela Riemekasten has no financial or other conflicts of interest in relation to this manuscript.

Alan Tyndall has no financial or other conflicts of interest in relation to this manuscript.

Marco Matucci-Cerinic has no financial or other conflicts of interest in relation to this manuscript.

Janet E. Pope has no financial or other conflicts of interest in relation to this manuscript.

REFERENCES

- 1.Masi AT, Medsger TA, Jr, Rodnan GP, Fries JF, Altman RD, Brown BW, et al. Methods and Preliminary Results of the Scleroderma Criteria Cooperative Study of the American Rheumatology Association. ClinRheumDis. 1979;5(1):27–48. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Preliminary criteria for the classification of systemic sclerosis (scleroderma). Subcommittee for scleroderma criteria of the American Rheumatism Association Diagnostic and Therapeutic Criteria Committee. Arthritis Rheum. 1980 May;23(5):581–590. doi: 10.1002/art.1780230510. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Preliminary criteria for the classification of systemic sclerosis (scleroderma) BullRheumDis. 1981;31(1):1–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Nadashkevich O, Davis P, Fritzler MJ. A proposal of criteria for the classification of systemic sclerosis. MedSciMonit. 2004;10(11):CR615–CR621. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Walker JG, Pope J, Baron M, Leclercq S, Hudson M, Taillefer S, et al. The development of systemic sclerosis classification criteria. Clin Rheumatol. 2007 Sep;26(9):1401–1409. doi: 10.1007/s10067-007-0537-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hudson M, Taillefer S, Steele R, Dunne J, Johnson SR, Jones N, et al. Improving the sensitivity of the American College of Rheumatology classification criteria for systemic sclerosis. Clin Exp Rheumatol. 2007 Sep-Oct;25(5):754–757. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Johnson SR, Feldman BM, Hawker GA. Classification criteria for systemic sclerosis subsets. J Rheumatol. 2007 Sep;34(9):1855–1863. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lonzetti LS, Joyal F, Raynauld JP, Roussin A, Goulet JR, Rich E, et al. Updating the American College of Rheumatology preliminary classification criteria for systemic sclerosis: addition of severe nailfold capillaroscopy abnormalities markedly increases the sensitivity for limited scleroderma. Arthritis Rheum. 2001;44(3):735–736. doi: 10.1002/1529-0131(200103)44:3<735::AID-ANR125>3.0.CO;2-F. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hachulla E, Launay D. Diagnosis and classification of systemic sclerosis. Clin Rev Allergy Immunol. 2011 Apr;40(2):78–83. doi: 10.1007/s12016-010-8198-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Avouac J, Fransen J, Walker UA, Riccieri V, Smith V, Muller C, et al. Preliminary criteria for the very early diagnosis of systemic sclerosis: results of a Delphi Consensus Study from EULAR Scleroderma Trials and Research Group. Ann Rheum Dis. 2011 Mar;70(3):476–481. doi: 10.1136/ard.2010.136929. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Winterbauer RH. Multiple Telangiectasia, Raynaud's Phenomenon, Sclerodactyly, and Subcutanious Calcinosis: A Syndrome Mimicking Hereditary Hemorrhagic Telangiectasia. Bull Johns Hopkins Hosp. 1964 Jun;114:361–383. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Nadashkevich O, Davis P, Fritzler MJ. Revising the classification criteria for systemic sclerosis. Arthritis Rheum. 2006;55(6):992–993. doi: 10.1002/art.22364. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Goetz R, Berne M. The pathophysiology of progressive systemic sclerosis (generalised scleroderma) with special reference to changes in the viscere. Clin Proc. 1945;4:337–392. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Wollheim FA. Classification of systemic sclerosis. Visions and reality. Rheumatology(Oxford) 2005;44(10):1212–1216. doi: 10.1093/rheumatology/keh671. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Maricq HR, Valter I. A working classification of scleroderma spectrum disorders: a proposal and the results of testing on a sample of patients. Clin Exp Rheumatol. 2004 Jan-Feb;22(3 Suppl 33):S5–S13. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.LeRoy EC, Black C, Fleischmajer R, Jablonska S, Krieg T, Medsger TA, Jr, et al. Scleroderma (systemic sclerosis): classification, subsets and pathogenesis. J Rheumatol. 1988 Feb;15(2):202–205. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Tuffanelli DL, Winkelmann RK. Diffuse systemic scleroderma. A comparison with acrosclerosis. Ann Intern Med. 1962 Aug;57:198–203. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-57-2-198. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ferri C, Valentini G, Cozzi F, Sebastiani M, Michelassi C, La Montagna G, et al. Systemic sclerosis: demographic, clinical, and serologic features and survival in 1,012 Italian patients. Medicine (Baltimore) 2002 Mar;81(2):139–153. doi: 10.1097/00005792-200203000-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Felson DT, Anderson JJ. Methodological and statistical approaches to criteria development in rheumatic diseases. Baillieres Clin Rheumatol. 1995 May;9(2):253–266. doi: 10.1016/s0950-3579(05)80189-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Singh JA, Solomon DH, Dougados M, Felson D, Hawker G, Katz P, et al. Development of classification and response criteria for rheumatic diseases. Arthritis Rheum. 2006 Jun 15;55(3):348–352. doi: 10.1002/art.22003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Johnson SR, Goek ON, Singh-Grewal D, Vlad SC, Feldman BM, Felson DT, et al. Classification criteria in rheumatic diseases: a review of methodologic properties. Arthritis Rheum. 2007 Oct 15;57(7):1119–1133. doi: 10.1002/art.23018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Dougados M, Betteridge N, Burmester GR, Euller-Ziegler L, Guillemin F, Hirvonen J, et al. EULAR standardised operating procedures for the elaboration, evaluation, dissemination, and implementation of recommendations endorsed by the EULAR standing committees. Ann Rheum Dis. 2004 Sep;63(9):1172–1176. doi: 10.1136/ard.2004.023697. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Dougados M, Gossec L. Classification criteria for rheumatic diseases: why and how? Arthritis Rheum. 2007 Oct 15;57(7):1112–1115. doi: 10.1002/art.23015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Fransen J, Johnson SR, van den Hoogen F, Baron M, Allanore Y, Carreira E, et al. Items for revised classification criteria in systemic sclerosis: results of a consensus exercise with the EULAR/ACR working group for classification criteria in systemic sclerosis. Arth Care Res. 2011 doi: 10.1002/acr.20679. Submitted. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Johnson SR, Hawker GA, Davis AM. The health assessment questionnaire disability index and scleroderma health assessment questionnaire in scleroderma trials: an evaluation of their measurement properties. Arthritis Rheum. 2005;53(2):256–262. doi: 10.1002/art.21084. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Streiner DL, Norman GR. A Practical Guide to their Development and Use Fourth ed. Oxford: Oxford Universit Press; 2008. Health Measurement Scales. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Pepe MS, Janes H, Longton G, Leisenring W, Newcomb P. Limitations of the odds ratio in gauging the performance of a diagnostic, prognostic, or screening marker. Am J Epidemiol. 2004 May 1;159(9):882–890. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwh101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Fletcher RH, Fletcher SW. The Essentials. Fourth ed. Baltimore: Lippincott Williams and Wilkins; 2005. Clinical Epidemiology. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Spiegelhalter D, Abrams K, Myles J. Bayesian approaches to clinical trials and health-care evaluation. Chichester: John Wiley & Sons, Ltd; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kuwana M, Kaburaki J, Arnett FC, Howard RF, Medsger TA, Jr, Wright TM. Influence of ethnic background on clinical and serologic features in patients with systemic sclerosis and anti-DNA topoisomerase I antibody. Arthritis Rheum. 1999 Mar;42(3):465–474. doi: 10.1002/1529-0131(199904)42:3<465::AID-ANR11>3.0.CO;2-Y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Steen VD, Medsger TA. Changes in causes of death in systemic sclerosis, 1972–2002. Ann Rheum Dis. 2007 Jul;66(7):940–944. doi: 10.1136/ard.2006.066068. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Peschken CA, Katz SJ, Silverman E, Pope JE, Fortin PR, Pineau C, et al. The 1000 Canadian faces of lupus: determinants of disease outcome in a large multiethnic cohort. J Rheumatol. 2009 Jun;36(6):1200–1208. doi: 10.3899/jrheum.080912. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Low AH, Johnson SR, Lee P. Ethnic influence on disease manifestations and autoantibodies in Chinese-descent patients with systemic sclerosis. J Rheumatol. 2009 Apr;36(4):787–793. doi: 10.3899/jrheum.080915. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Punglia RS, D'Amico AV, Catalona WJ, Roehl KA, Kuntz KM. Effect of verification bias on screening for prostate cancer by measurement of prostate-specific antigen. N Engl J Med. 2003 Jul 24;349(4):335–342. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa021659. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Tan EM, Cohen AS, Fries JF, Masi AT, McShane DJ, Rothfield NF, et al. The 1982 revised criteria for the classification of systemic lupus erythematosus. Arthritis Rheum. 1982;25(11):1271–1277. doi: 10.1002/art.1780251101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Hochberg MC. Updating the American College of Rheumatology revised criteria for the classification of systemic lupus erythematosus. Arthritis Rheum. 1997;40(9):1725. doi: 10.1002/art.1780400928. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Aletaha D, Neogi T, Silman AJ, Funovits J, Felson DT, Bingham CO, 3rd, et al. 2010 Rheumatoid arthritis classification criteria: an American College of Rheumatology/European League Against Rheumatism collaborative initiative. Arthritis Rheum. 2010 Sep;62(9):2569–2581. doi: 10.1002/art.27584. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]