Abstract

In developing countries, Salmonella enterica serovar Enteritidis causes substantial illness and death, and drug resistance is increasing. Isolates from the United Kingdom containing virulence-resistance plasmids were characterized. They mainly caused invasive infections in adults linked to Africa. The common features in isolates from these continents indicate the role of human travel in their spread.

Keywords: hybrid plasmid, antimicrobial resistance, virulence, PFGE, MLST, Salmonella enterica serovar Enteritidis, Africa, salmonellosis, salmonellae

Worldwide, nontyphoidal Salmonella enterica is a major cause of foodborne illness, and Enteritidis is one of the most commonly reported serovars (www.who.int/salmsurv/links/GSSProgressReport2005.pdf). In industrialized countries, S. enterica serovar Enteritidis commonly causes self-limiting gastroenteritis, for which treatment with antimicrobial drugs is usually not needed. However, in developing countries, this serovar, together with serovar Typhimurium, frequently causes invasive infections and substantial illness and death among young children with underlying diseases and among adults with HIV infection (1). Although antimicrobial drug resistance is not as high in S. enterica serovar Enteritidis as in other zoonotic disease serovars, multidrug-resistance (resistance to >4 antimicrobial drugs) has been increasingly reported (2), threatening treatment success for patients with severe infections. In recent years, in association with multidrug resistance, another trend has arisen: the emergence of virulence-resistance (VR) plasmids; these are hybrid plasmids that harbor resistance (R) and virulence (V) determinants. The appearance of these plasmids is of concern because they could lead to the co-selection of virulence (in addition to resistance) through the use of antimicrobial drugs (3,4). One such plasmid, pUO-SeVR1, has been recently reported in a multidrug-resistant (MDR) clinical isolate of S. enterica serovar Enteritidis (CNM4839/03) from Spain (5). This mobilizable plasmid of ≈100 kb derives from pSEV, the serovar-specific V plasmid of S. enterica serovar Enteritidis, and carries most of its V determinants, including the spvRABCD locus (Salmonella plasmid virulence). This plasmid greatly increases the ability of salmonellae to proliferate intracellularly and has been associated with severe infections in humans (6). The plasmid also harbors several R genes—blaTEM-1, catA2, strA-strB, sul1, sul2, tet(A)—and a class-1 integron with the 700-bp/dfrA7 variable region, which confer resistance to ampicillin, chloramphenicol, streptomycin, sulfonamides, tetracycline, and trimethoprim (R-type ACSSuTTm). To investigate their international spread, we studied the presence of S. enterica serovar Enteritidis isolates carrying pUO-SeVR1–like plasmids in the United Kingdom.

The Study

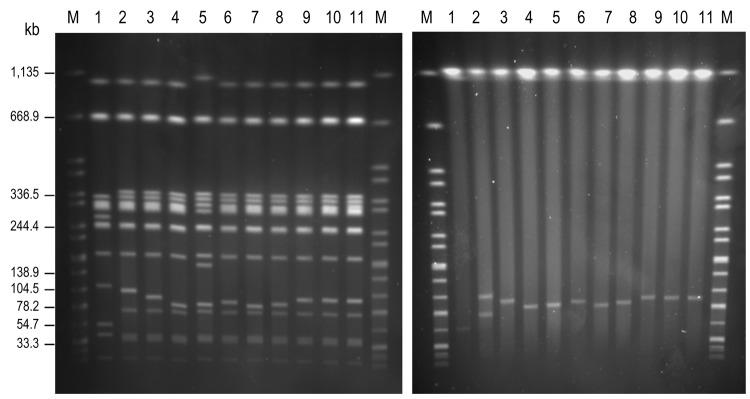

We screened 31,615 S. enterica serovar Enteritidis isolates that had been collected from clinical specimens during 2005–2010 and deposited in the culture collection of the Health Protection Agency Salmonella Reference Unit. We screened the isolates for R-type ACSSuTTm. A total of 14 serovar Enteritidis isolates showing this resistance phenotype were detected and subsequently examined for the presence of integron-located dfrA7. Of the 14 isolates, 11 were positive and their plasmid content was analyzed by S1 pulsed-field gel electrophoresis (PFGE) (2) and by the Kado and Liu methods (7); we used serovar Enteritidis strains NRL-Salm-PT4 and CNM4839/03 as controls for pSEV– and pUO-SeVR1–carrying isolates, respectively. The 11 isolates harbored 1 plasmid of variable size (60–95 kb); among these, 9 isolates hybridized with dfrA7-specific and spvC-specific probes (with plasmids of 85–95 kb) (Figure). These 9 isolates contained a VR-hybrid plasmid similar to pUO-SeVR1 and were selected for further analyses (Table 1, Table 2). The remaining 2 isolates carried the normal pSEV plasmid (60 kb), in which spvC hybridized; dfrA7 was chromosomally located.

Figure.

Genomic macrorestriction of Salmonella enterica serovar Enteritidis isolates: pulsed-field gel electrophoresis profiles for XbaI (left panel) and S1 (right panel). Lane M, XbaI-digested DNA of S. enterica serovar Braenderup H9812, used as size standard; lane 1, NRL-Salm-PT4; lane 2, CNM4839/03; lane 3, H051860415; lane 4, H070360201; lane 5, H070420137; lane 6, H073180204; lane 7, H091340084; lane 8, H091800482; lane 9, H095100307; lane 10, H100240198; lane 11, H101700366. The strain NRL-Salm-PT4 was used as control for the most commonly found XbaI-profile in S. enterica serovar Enteritidis.

Table 1. Epidemiologic information for multidrug-resistant Salmonella enterica serovar Enteritidis isolates, 2005–2010, UK*.

| Isolate no. | Date of isolation | Source | Recent travel history | African patient name | Patient age, y |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CNM4839/03† | 2003 | Feces | Unknown | No | 3 |

| H051860415 | 2005 Apr 19 | Blood | Nigeria | No | 38 |

| H070360201‡ | 2007 Jan 14 | Blood | Unknown | Yes | 35 |

| H070420137‡ | 2007 Jan 15 | Feces | Unknown | Yes | 35 |

| H073180204 | 2007 Jul 31 | Blood | Unknown | Yes | 34 |

| H091340084 | 2009 Mar 15 | Feces | Uganda | No | 59 |

| H091800482 | 2009 Apr 17 | Blood | Unknown | Yes | 30 |

| H095100307§ | 2009 Dec 7 | Blood | Unknown | Yes | 68 |

| H100240198§ | 2010 Jan 9 | Blood | Unknown | Yes | 68 |

| H101700366§ | 2010 Apr 22 | Blood | Unknown | Yes | 68 |

*All isolates contained a virulence-resistance hybrid plasmid similar to pUO-SeVR1. †Control isolate from Spain. ‡Recovered from the same patient. §Recovered from the same patient.

Table 2. Characteristics of Salmonella enterica serovar Enteritidis isolates harboring pUO-SeVR1-like plasmids, 2005–2010, UK*.

| Isolate no. | Phage type | Resistance phenotype/ genotype | Class 1 integron† | pSEV genes‡ | MLVA | MLST | VR plasmid, kb |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CNM4839/03 | PT 14b | AMP, CHL, STR, SUL, TET, TMP/blaTEM-1, catA2, strA-strB, sul1, sul2, tet(A), dfrA7 | 700 bp/dfrA7 | spvA, spvB, spvC, spvR, rsk, rck, mig-5, srgB, srgC, pefA, pefB, pefC, pefD | 2-12-9-4-4-3-NA-8-8 | ST11 | 100 |

| H051860415 | PT 42 | AMP, CHL, STR, SUL, TET, TMP/blaTEM-1, catA2, strA-strB, sul1, sul2, tet(A), dfrA7 | 700 bp/dfrA7 | spvA, spvB, spvC, spvR, rsk, rck, mig-5, srgB, srgC, pefA, pefB, pefC, pefD | 2-13-9-4-4-3-NA-8-8 | ST1479 | 95 |

| H070360201 | PT 42 | AMP, CHL, STR, SUL, TET, TMP/blaTEM-1, catA2, strA-strB, sul1, sul2, tet(A), dfrA7 | 700 bp/dfrA7 | spvA, spvB, spvC, spvR, rsk, rck, mig-5, ΔsrgA, srgB, srgC, pefA, pefB | 2-15-9-4-4-3-NA-8-8 | ST1479 | 88 |

| H070420137 | PT 42 | AMP, CHL, STR, SUL, TET, TMP/blaTEM-1, catA2, strA-strB, sul1, sul2, tet(A), dfrA7 | 700 bp/dfrA7 | spvA, spvB, spvC, spvR, rsk, rck, mig-5, ΔsrgA, srgB, srgC, pefA, pefB | 2-15-9-4-4-3-NA-8-8 | ND | 88 |

| H073180204 | PT 42 | AMP, CHL, STR, SUL, TET, TMP/blaTEM-1, catA2, strA-strB, sul1, sul2, tet(A), dfrA7 | 700 bp/dfrA7 | spvA, spvB, spvC, spvR, rsk, rck, mig-5, srgB, srgC, pefA, pefB, pefC, pefD | 2-13-9-4-4-3-NA-8-8 | ND | 92 |

| H091340084 | PT 42 | AMP, CHL, STR, SUL, TET, TMP/blaTEM-1, catA2, strA-strB, sul1, sul2, tet(A), dfrA7 | 700 bp/dfrA7 | spvA, spvB, spvC, spvR, rsk, rck, mig-5, ΔsrgA, srgB, srgC, pefA, pefB, pefC, pefD | 2-9-9-4-4-3-NA-8-8 | ST11 | 90 |

| H091800482 | PT 42 | AMP, CHL, STR, SUL, TET, TMP/blaTEM-1, catA2, strA-strB, sul1, sul2, tet(A), dfrA7 | 700 bp/dfrA7 | spvA, spvB, spvC, spvR, rsk, rck, mig-5, srgB, srgC, pefA, pefB, pefC, pefD | 2-13-9-4-4-3-NA-8-8 | ND | 92 |

| H095100307 | PT 42 | AMP, CHL, STR, SUL, TET, TMP/blaTEM-1, catA2, strA-strB, sul1, sul2, tet(A), dfrA7 | 700 bp/dfrA7 | spvA, spvB, spvC, spvR, rsk, rck, mig-5, ΔsrgA, srgB, srgC, pefA, pefB, pefC, pefD | 2-13-9-4-4-3-NA-8-8 | ND | 95 |

| H100240198 | PT 42 | AMP, CHL, STR, SUL, TET, TMP/blaTEM-1, catA2, strA-strB, sul1, sul2, tet(A), dfrA7 | 700 bp/dfrA7 | spvA, spvB, spvC, spvR, rsk, rck, mig-5, ΔsrgA, srgB, srgC, pefA, pefB, pefC, pefD | 2-13-9-4-4-3-NA-8-8 | ND | 95 |

| H101700366 | PT 42 | AMP, CHL, STR, SUL, TET, TMP/blaTEM-1, catA2, strA-strB, sul1, sul2, tet(A), dfrA7 | 700 bp/dfrA7 | spvA, spvB, spvC, spvR, rsk, rck, mig-5, ΔsrgA, srgB, srgC, pefA, pefB, pefC, pefD | 2-13-9-4-4-3-NA-8-8 | ND | 95 |

*pSEV, serovar-specific V plasmid of S.enterica serovar Enteritidis; MLVA, multilocus variable number tandem repeat analysis; MLST, multilocus sequence typing; VR, virulence-resistance; PT, phage type; NA, no amplification from this locus; AMP, ampicillin; CHL, chloramphenicol; STR streptomycin; SUL, sulfonamides; TET, tetracycline; TMP, trimethoprim; ST, sequence type; ND, not done. †Size of the variable region amplified with the 5′CS and 3′CS primers (2). ‡All plasmids were positive for IncFIIA, IncFIB and the par locus. Two new primer pairs were devised for detection of srgA: srgAB-Fw1/Rv1 (5′-CGCCTTCCGTGTATGTCC/GCGAGTCACTCACCGACAG-3′) and srgAB-Fw2/Rv2 (5′-GTTGCACAGGAGTGGGAGTC/GTCCGGGTTCCATGTCAG-3′). The forward primers anneal at different positions within srgA; the reverse primers anneal at different positions within srgB.

In the 9 isolates carrying VR-hybrid plasmids, the R-type ACSSuTTm was encoded by the R-genes blaTEM-1, catA2, strA-strB, sul1, sul2, tet(A), and dfrA7, which were located on the pUO-SeVR1–like plasmids as determined by Southern blot hybridization. By PCR amplification, using previously described primers and conditions (5,8) (Table 2), and by Southern blot hybridization (5), we tested for the presence of IncFII and IncFIB replicons, parAB (partition), spvRABCD, rck (resistance to complement killing), mig-5 (macrophage-induced gene), pefABCDI (Pef fimbriae operon), and srgA (SdiA-regulated gene; next to orf7), all carried by pSEV. The 9 plasmids were positive for the 2 replicons and for all genes screened except pefC and pefD (absent in H070360201 and H070420137), pefI-orf7 (absent in all), and srgA (either absent [H051860415, H073180204, and H091800482] or truncated [in the remaining isolates]) (Table 2).

Isolate subtyping was conducted by phage typing, multilocus variable number tandem repeat analysis (MLVA), multilocus sequence typing (MLST), and XbaI-PFGE (9,10) (http://mlst.ucc.ie/mlst/dbs/Senterica; www.pulsenetinternational.org). The 9 S. enterica serovar Enteritidis isolates belong to phage type (PT) 42, in contrast with CNM4839/03, which belongs to PT14b (Table 2). We identified 4 MLVA profiles, which were all single-locus variants of the highly variable locus SENTR5, indicating that the isolates are closely related (Table 2). The isolate from Spain and 3 of the 9 isolates from the United Kingdom, selected as representative of each MLVA profile, were also analyzed by MLST (Table 2). CNM4839/03 and H091340084 were assigned to sequence type (ST) 11, the most commonly found ST in serovar Enteritidis (http://mlst.ucc.ie/mlst/). The remaining 2 isolates could be ascribed to ST1479, the first examples of this single-locus variant of ST11 in the MLST database (Table 2). According to XbaI-PFGE, the control strain NRL-Salm-PT4 showed a clearly distinct profile in comparison with CNM4839/03 and the 9 isolates containing pUO-SeVR1–like plasmids, which generated 6 closely related patterns (Figure). Most isolates differed by 1 band of variable size (85–95 kb), which corresponded to the XbaI-linearized VR-hybrid plasmids. As an exception, isolate H070420137 showed additional differences in chromosomal bands of ≈150 and ≈300 kb. Because isolates H070420137 and H070360201 came from the same patient (Table 1) and shared the same V and R genotypes and other typing markers, 1 isolate could have evolved from the other; however, co-infection of the patient with 2 closely related strains cannot be ruled out. In addition, considering the typing results of H095100307, H100240198, and H101700366, the identical size of their plasmids, and the fact that they were isolated from the same patient (Table 1), these 3 isolates can be considered the same strain.

All except 2 of the UK isolates carrying pUO-SeVR1–like plasmids were recovered from the blood of patients who had recently returned from an African country or who had an African name (Table 1). Supporting the possible African origin, similar XbaI-PFGE profiles and MDR phenotypes (ampicillin, trimethoprim, sulfonamides, and tetracycline) have been identified in clinical S. enterica serovar Enteritidis isolates involved in outbreaks and community infections in different African countries. These isolates caused bacteremia, meningitis, diarrhea (11–13), and high case-fatality rates; they affected mainly children, whereas most clinical isolates analyzed in our study were obtained from adults with bacteremia (Table 1). The detection of the 700-bp/dfrA7 integron in S. enterica serovar Enteritidis isolates from Africa (14) also supports an African origin of the MDR serovar Enteritidis isolates harboring pUO-SeVR1–like plasmids. Of note, resistance derivatives of pSLT, the V-plasmid specific to S. Typhimurium, have been found in the epidemic ST313 clone of this serovar, which has been considered a major cause of invasive disease in sub-Saharan Africa (15).

Conclusions

Closely related MDR S. enterica serovar Enteritidis isolates carrying pUO-SeVR1–like plasmids were recovered in the United Kingdom. Most were isolated from the blood of patients linked to Africa, and they showed common features with serovar Enteritidis isolates involved in outbreaks on that continent. The possibility that this potentially invasive clone of S. enterica serovar Enteritidis can be spread through human travel, together with the detection of VR-plasmids in the serovar most frequently associated with human infections, is of public health concern and requires surveillance.

Acknowledgments

We thank B. Malorny and E. Junker for help with MLVA typing; A. Schroeter, J. Ledwolorz, and staff of the Health Protection Agency Salmonella Reference Unit for phage typing; and I. Montero for help with MLST. We are grateful to R. Helmuth for his advice and critical reading of the manuscript.

This study was supported by the Health Protection Agency, the Federal Institute for Risk Assessment (BfR-46-001; 45-005), and the “Fondo de Investigación Sanitaria” of the “Instituto de Salud Carlos III” of Spain (project FIS PI11/00808, cofunded by the European Regional Development Fund of the European Union: a Way of Making Europe). I.R. received a postdoctoral grant from Fundación Ramón Areces, Madrid, Spain.

For strain requests, contact the Health Protection Agency Colindale, email: katie.hopkins@hpa.org.uk.

Biography

Dr Rodríguez is a postdoctoral fellow at the Federal Institute for Risk Assessment in Berlin, Germany, in the Unit of Antimicrobial Resistance and Resistance Determinants of the Department of Biological Safety. Her research focuses on the genotypic characterization of antimicrobial drug resistance and the molecular epidemiology of gram-negative drug-resistant bacteria.

Footnotes

Suggested citation for this article: Rodríguez I, Rodicio MR, Guerra B, Hopkins KL. Potential international spread of multidrug-resistant invasive Salmonella enterica serovar Enteritidis. Emerg Infect Dis [serial on the Internet]. 2012 Jul [date cited]. http://dx.doi.org/10.3201/eid1807.120063

References

- 1.Graham SM. Nontyphoidal salmonellosis in Africa. Curr Opin Infect Dis. 2010;23:409–14. 10.1097/QCO.0b013e32833dd25d [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Rodríguez I, Rodicio MR, Herrera-León S, Echeita A, Mendoza MC. Class 1 integrons in multidrug-resistant non-typhoidal Salmonella enterica isolated in Spain between 2002 and 2004. Int J Antimicrob Agents. 2008;32:158–64. 10.1016/j.ijantimicag.2008.03.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Chu C, Chiu CH. Evolution of the virulence plasmids of non-typhoid Salmonella and its association with antimicrobial resistance. Microbes Infect. 2006;8:1931–6. 10.1016/j.micinf.2005.12.026 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Rodicio MR, Herrero A, Rodríguez I, García P, Montero I, Beutlich J, et al. Acquisition of antimicrobial resistance determinants by virulence plasmids specific for nontyphoid serovars of Salmonella enterica. Rev Med Microbiol. 2011;22:55–65. 10.1097/MRM.0b013e328346d87d [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Rodríguez I, Guerra B, Mendoza MC, Rodicio MR. pUO-SeVR1 is an emergent virulence-resistance complex plasmid of Salmonella enterica serovar Enteritidis. J Antimicrob Chemother. 2011;66:218–20. 10.1093/jac/dkq386 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Fierer J. Extraintestinal Salmonella infections: the significance of the spv genes. Clin Infect Dis. 2001;32:519–20. 10.1086/318505 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kado CI, Liu S-T. Rapid procedure for detection and isolation of large and small plasmids. J Bacteriol. 1981;145:1365–73. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Carattoli A, Bertini A, Villa L, Falbo V, Hopkins KL, Threlfall EJ. Identification of plasmids by PCR-based replicon typing. J Microbiol Methods. 2005;63:219–28. 10.1016/j.mimet.2005.03.018 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ward LR, de Sa JD, Rowe B. A phage-typing scheme for Salmonella enteritidis. Epidemiol Infect. 1987;99:291–4. 10.1017/S0950268800067765 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Malorny B, Junker E, Helmuth R. Multi-locus variable-number tandem repeat analysis for outbreak studies of Salmonella enterica serotype Enteritidis. BMC Microbiol. 2008;8:84. 10.1186/1471-2180-8-84 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Vaagland H, Blomberg B, Krüger C, Naman N, Jureen R, Langeland N. Nosocomial outbreak of neonatal Salmonella enterica serotype Enteritidis meningitis in a rural hospital in northern Tanzania. BMC Infect Dis. 2004;4:35. 10.1186/1471-2334-4-35 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kariuki S, Revathi G, Kariuki N, Kiiru J, Mwituria J, Hart CA. Characterisation of community acquired non-typhoidal Salmonella from bacteremia and diarrhoeal infections in children admitted to hospital in Nairobi, Kenya. BMC Microbiol. 2006;6:101. 10.1186/1471-2180-6-101 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Akinyemi KO, Philipp W, Beyer W, Böhm R. Application of phage typing and pulsed-field gel electrophoresis to analyse Salmonella enterica isolates from a suspected outbreak in Lagos, Nigeria. J Infect Dev Ctries. 2010;4:828–33. 10.3855/jidc.744 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Krauland MG, Marsh JW, Paterson DL, Harrison LH. Integron-mediated multidrug resistance in a global collection of nontyphoidal Salmonella enterica isolates. Emerg Infect Dis. 2009;15:388–96. 10.3201/eid1503.081131 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kingsley RA, Msefula CL, Thomson NR, Kariuki S, Holt KE, Gordon MA, et al. Epidemic multiple drug resistant Salmonella Typhimurium causing invasive disease in sub-Saharan Africa have a distinct genotype. Genome Res. 2009;19:2279–87. 10.1101/gr.091017.109 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]