Abstract

The purpose of this study was to assess lateral out-of-field doses in 6 MV IMRT (intensity modulated radiation therapy) and compare them with secondary neutron equivalent dose contributions in proton therapy. We simulated outof-field photon doses to various organs as a function of distance, patient's age, gender and treatment volumes based on 3, 6, 9 cm field diameters in the head and neck and spine region. The out-of-field photon doses to organs near the field edge were found to be in the range of 2, 5 and 10 mSv Gy−1 for 3 cm, 6 cm and 9 cm diameter IMRT fields, respectively, within 5 cm of the field edge. Statistical uncertainties calculated in organ doses vary from 0.2% to 40% depending on the organ location and the organ volume. Next, a comparison was made with previously calculated neutron equivalent doses from proton therapy using identical field arrangements. For example, out-of-field doses for IMRT to lung and uterus (organs close to the 3 cm diameter spinal field) were computed to be 0.63 and 0.62 mSv Gy−1, respectively. These numbers are found to be a factor of 2 smaller than the corresponding out-of-field doses for proton therapy, which were estimated to be 1.6 and 1.7 mSv Gy−1 (RBE), respectively. However, as the distance to the field edge increases beyond approximately 25 cm the neutron equivalent dose from proton therapy was found to be a factor of 2–3 smaller than the out-of-field photon dose from IMRT. We have also analyzed the neutron equivalent doses from an ideal scanned proton therapy (assuming not significant amount of absorbers in the treatment head). Outof-field doses were found to be an order of magnitude smaller compared to out-of-field doses in IMRT or passive scattered proton therapy. In conclusion, there seem to be three geometrical areas when comparing the out-of-target dose from IMRT and (passive scattered) proton treatments. Close to the target (in-field, not analyzed here) protons offer a distinct advantage due to the lower integral dose. Out-of-field, but within approximately 25 cm from the field edge, the scattered photon dose in IMRT turned out to be roughly a factor of 2 lower than the neutron equivalent dose from proton therapy for the fields considered in this study. At larger distances to the field (beyond~ 25 cm), protons offer an advantage, resulting in doses that are roughly a factor of 2–3 lower.

1. Introduction

Dose delivered to organs away from the primary treatment fields may cause late effects, e.g. second cancers. The magnitude of the risk is not well known as biological parameters are associated with large uncertainties. It has been argued that there should be a concern for highly conformal treatment delivery techniques, like IMRT (intensity modulated radiation therapy) or proton therapy (Hall 2006, Kry et al 2004, Palm and Johansson 2007). In IMRT, out-of-field photon dose primarily arises from the leakage through the accelerator head, leakage through the multi-leaf collimator (MLC) and the scatter within the patient. In proton treatments, secondary neutrons (neutrons produced in the treatment head and in the patient) are the primary source of secondary radiation (Zacharatou Jarlskog et al 2008, Newhauser et al 2009, Taddei et al 2009, Athar and Paganetti 2009). Experimental and simulated out-of-field doses in water phantoms from photon and proton therapies have been reviewed recently by Xu et al (2008).

Previously, our group has analyzed secondary doses from proton therapy considering different treatment volumes in the head and spine regions (Zacharatou Jarlskog et al 2008, Athar and Paganetti 2009). In this study, we have adopted a similar methodology to simulate IMRT treatments assuming the same target volumes and treatment sites. The goal was to compare out-of-field doses in IMRT with those in proton therapy. It is well known that proton therapy offers a distinct advantage (Mirabell et al 2002) over IMRT in the field (due to the much lower integral dose). However, we focus on doses out-of-field, i.e. in organs typically not imaged for treatment planning purposes. This is the first time that age-dependent whole-body computational phantoms were used to assess out-of-field doses from IMRT fields. Such phantoms are needed in particular for analyzing pediatric patients because whole-body CTs are typically not available.

2. Methods and materials

2.1. Whole-body voxelized phantoms and Monte Carlo

A set of adult (Xu et al 2000) and pediatric (Lee and Bolch 2003, Lee et al 2005) phantoms were applied within our computational framework, as described elsewhere (Athar and Paganetti 2009, Zacharatou Jarlskog et al 2008). The ages and genders simulated by the phantoms considered in this work were 9 month, 11 year, 14 year, and adult 39 year males and 4 year and 8 year old females. Dose calculations in the phantom geometries were all done within our implementation of the Geant4 Monte Carlo code by sampling source particles from phase space files (Paganetti et al 2004). The version 8.1.p01 of the Geant4 toolkit was used (Agostinelli 2003).

Treatment head simulations and phantom simulations for protons were done with Geant4 as described elsewhere (Athar and Paganetti 2009, Zacharatou Jarlskog et al 2008). In our analysis of proton irradiation we differentiated between external neutrons (from the treatment head) and internal neutrons (from the patient) as the two sources of secondary neutrons. The relative biological effectiveness (RBE) for protons in the field was assumed to be 1.1. For neutrons, we applied the ICRP-recommended energy-dependent radiation weighting factors (ICRP 2003). Weighting factors were applied on the fly during the simulation at each energy deposition event depending on the energy and the particle history as described previously (Zacharatou Jarlskog et al 2008). For IMRT, photon phase spaces were generated downstream of the multi-leaf collimator (MLC) using the Monte Carlo code MCNPX (MCNPX 2002). This code was used so as to utilize a detailed simulation of the Varian Linac (2100 Clinac C) treatment head along with the 80-leaf (MLC) model developed at Rensselaer Polytechnic Institute RPI (Bednarz and Xu 2009). The phase spaces were then applied to simulate organ doses within the Geant4 implementation of the phantoms.

2.2. Field characteristics and beam parameterization

For the proton therapy fields, the beam energies at the treatment head entrance were 196.2 MeV and 178.3 MeV for range/modulation width combinations of 10 cm/5 cm and 15 cm/10 cm, respectively (Athar and Paganetti 2009).

An attempt was made to match the IMRT treatment fields as closely as possibly to the proton therapy fields. The fields used in this study had a circular shape of diameters 3 cm, 6 cm and 9 cm (see table 1). The jaw settings were matched to circumscribe the circular apertures. Proton and IMRT doses were normalized to the dose in 1.5 cm radius water spheres at depths of 7.5 cm and 10 cm, resembling the centers of the proton SOBPs in depth.

Table 1.

Field diameter and depth of dose normalization.

| Field | Aperture diameter (cm) | Normalization depth (cm) |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | 3 | 7.5 |

| 2 | 6 | 7.5 |

| 3 | 9 | 7.5 |

| 4 | 3 | 10 |

| 5 | 6 | 10 |

| 6 | 9 | 10 |

Because we focused on doses deposited outside of the primary radiation field, the doses experienced by organs lateral to the field directions are more or less independent of the coplanar beam angle. We therefore were able to limit the simulations to one gantry angle. We used the same gantry angle and beam setup for proton and IMRT irradiations. For the setup in the case of brain fields, the beams were positioned lateral to the head (i.e. gantry angle at 90°). In the spine field setup, the beams were positioned posteriorly pointing toward a location between vertebrae-t and vertebrae-l (centered around vertebrae T12) with the gantry angle at 180°. Because this study focused on out-of-field doses, we did exclude the entire coplanar treatment `slice' of the patient in the data analysis. Consequently, the number of organs included in our analysis depends on the field size (and on the patient geometry). Table 2 shows the total number of organs simulated for two of the fields and for two geometries as an example, whereas table 3 lists all organs considered in the computational phantoms.

Table 2.

Number of organs simulated in the 8 year old female, the 11 year old male and the adult phantom for the 3 cm diameter field.

| Phantom | Number of organs considered when analyzing brain fields | Number of organs considered when analyzing spine fields |

|---|---|---|

| Adult male | 20 | 24 |

| 11 year old male | 47 | 38 |

| 8 year old female | 48 | 38 |

Table 3.

List of all organs considered for brain and spine field simulations. In younger patients and for large field sizes, the number of organs considered was less than that listed below.

| Adult male brain field | Thyroid, thymus, esophagus, spine, kidneys, large intestine, small intestine, adrenal, pancreas, gall bladder, bladder, prostate, rectum and testes. |

| 11 year old male brain field | Vertebrae-c, pharynx, larynx, thryoid, clavicle, sternum, trachea, scapulae, thymus, bronchi, humerus, esophagus, heart, lung, spleen, ribs, liver, vertebrae-t, vertebrae-l, spinal chord, kidneys, aorta, adrenal glands, stomach wall, small intestine wall, pancreas, colon wall, gall bladder wall, rectosimoid wall, radii ulnae, sacrum, prostate, testes, bladder wall, os coxae, hands, femur, patellae, fibula and ankle feet |

| 8 year old female brain field | Vertebrae-c, pharynx, larynx, thryoid, clavicle, sternum, trachea, scapulae, thymus, bronchi, breasts, humerus, esophagus, heart, lung, spleen, ribs, liver, vertebrae-t, vertebrae-l, spinal chord, kidneys, aorta, adrenal glands, stomach wall, small intestine wall, pancreas, colon wall, gall bladder wall, rectosimoid wall, radii ulnae, sacrum, uterus, ovaries, bladder wall, os coxae, hands, femur, patellae, fibula and ankle feet |

| Adult male spine field | Brain, skull, corpus callosum, fornix, thalamus, optic nerve, optic chiasma, pons, vestibulochlear, eyes, mandible, thyroid, thymus, esophagus, heart, lungs, liver, spleen, adrenal, gall bladder, bladder, prostate, rectum and testes |

| 11 year old male spine field | Brain, pituitary glands, cranium, lenses, tongue, salivary glands, mandible, tonsils, pharynx, larynx, thyroid, vertebrae-c, clavicle, sternum, trachea, scapulae, thymus, bronchi, radii ulnae, esophagus, heart, lung, spleen, adrenal glands, rectosimoid wall, gall bladder wall, stomach wall, sacrum, prostate, testes, bladder wall, os coxae, hands, humerus, femur, patellae, fibula and ankle feet |

| 8 year old female spine field | Brain, pituitary glands, cranium, lenses, tongue, salivary glands, mandible, tonsils, pharynx, larynx, thyroid, vertebrae-c, clavicle, sternum, trachea, scapulae, thymus, bronchi, breasts, radii ulnae, esophagus, heart, lung, spleen, adrenal glands, rectosimoid wall, sacrum, uterus, ovaries, bladder wall, os coxae, hands, humerus, femur, patellae, fibula and ankle feet |

When treating with IMRT, the number of monitor units is typically increased compared to 3D conformal treatments because part of the beam is blocked by the MLC. The blocked primary beam may cause scattered doses due to head leakage and MLC scattering. We assumed that on average 3.5 times more MUs are delivered for the same prescribed dose as in a 3D conformal treatment. The only exception was the small 3 cm diameter field where we did not consider a MU correction factor because such a small field would presumably be delivered with only very few segments. Note that the scaling factor of 3.5 was only applied to the scattered portion of the beam. Thus, areas in the patient irradiated by the primary beam only and thus the scattered dose generated in the target itself were not scaled. The leakage part of the simulation was therefore performed separately from the primary beam simulations.

For the analysis of the IMRT scenario, we included MLC and head leakage and scattered doses. The contribution from the MLC leakage is expected to be small and should typically only affect organs close to the field edge. In contrast, head leakage contributes predominantly at large distances from the isocenter. The term out-of-field dose refers to dose outside the primary radiation field independent of the origin.

3. Results

Absorbed doses were simulated for six different phantoms. In the interest of space, we only present the results for the 8 year old female phantom. The graphs and tables shown throughout our analysis are approximately arranged in an increasing distance of the organ from the field edge.

3.1. Brain fields

Table 4 shows (8 year old female phantom only), for selected organs, the absorbed dose assuming an IMRT treatment (given as equivalent doses using a radiation weighting factor of 1). Organs near the field edge receive most of the doses from the patient scatter and MLC leakage while organs further away from the field edge receive secondary doses mainly from the treatment head leakage. In general, organs near the field edge receive doses around 10 mSv per treatment Gy. Large treatment volumes contribute large scattered doses to organs close to the field edge. Our analysis shows a significant impact of the patient's age. For example, organs in a 4 year old patient would receive higher doses compared to organs in an 8 year old patient because of differences in stature and organ position relative to the field. Due to the close proximity of organs in the 4 year old phantom the dose fall-off to lateral organs is not as rapid as in the bigger 8 year old phantom.

Table 4.

Out-of-field doses for six different cranial treatment fields in mSv Gy−1 for organs lateral to the field for an 8 year old female patient assuming an IMRT treatment. Hphot is the organ equivalent dose and ΔHphot = δHphot/Hphot is the statistical error in %.

| Female organs | Field 1 |

Field 2 |

Field 3 |

Field 4 |

Field 5 |

Field 6 |

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Hphot | Δ Hphot | Hphot | Δ Hphot | Hphot | Δ Hphot | Hphot | Δ Hphot | Hphot | Δ Hphot | Hphot | Δ Hphot | |

| Thyroid | 1.3 × 100 | 2.9% | 9.9 × 10−1 | 1.7% | 2.0 × 100 | 1.3% | 1.2 × 100 | 2.9% | 1.2 × 100 | 1.7% | 2.5 × 100 | 1.3% |

| Breasts | 6.6 × 10−1 | 6.4% | 3.7 × 10−1 | 5.2% | 7.1 × 10−1 | 3.8% | 9.4 × 10−1 | 6.4% | 1.1 × 100 | 0.6% | 7.9 × 10−1 | 3.8% |

| Lung | 1.1 × 100 | 0.5% | 5.5 × 10−1 | 0.4% | 7.1 × 10−1 | 0.3% | 1.1 × 100 | 0.5% | 6.2 × 10−1 | 0.4% | 7.9 × 10−1 | 0.3% |

| Liver | 1.0 × 100 | 0.8% | 3.0 × 10−1 | 0.5% | 2.9 × 10−1 | 0.4% | 1.2 × 100 | 0.8% | 3.8 × 10−1 | 0.5% | 3.5 × 10−1 | 0.4% |

| Kidneys | 2.6 × 100 | 2.4% | 7.0 × 10−1 | 1.3% | 5.1 × 10−1 | 1.2% | 3.0 × 100 | 2.4% | 9.4 × 10−1 | 1.3% | 6.5 × 10−1 | 1.2% |

| Colon Wall | 3.9 × 100 | 3.1% | 1.2 × 100 | 1.8% | 8.2 × 10−1 | 1.6% | 4.0 × 100 | 3.1% | 1.3 × 100 | 1.8% | 9.5 × 10−1 | 1.6% |

| Uterus | 2.0 × 100 | 32.0% | 7.5 × 10−1 | 16.0% | 5.7 × 10−1 | 10.5% | 1.9 × 100 | 32.0% | 7.6 × 10−1 | 16.0% | 6.2 × 10−1 | 10.5% |

| Ovaries | 2.0 × 100 | 38.6% | 8.0 × 10−1 | 23.0% | 5.6 × 10−11 | 15.4% | 1.9 × 100 | 38.6% | 6.7 × 10−1 | 23.0% | 6.0 × 10−1 | 15.4% |

3.2. Spine fields

The out-of-field photon doses in IMRT to selected organs as a function of the lateral distance from the field edge for spinal treatment fields are shown in table 5 (8 year old female phantom only). As described above, the organs considered per field and phantom depend on the field size because our focus was on the out-of-field contributions only. With increasing field opening (aperture size) the scattered absorbed doses to organs at larger distances from the target increase. Fields 4, 5 and 6 (see table 1), assuming a deep-seated tumor, show larger out-of-field doses than fields 1, 2 and 3, assuming a more shallow tumors. In IMRT this is primarily due to increased MUs (deep-seated tumors need more MUs to deliver a same prescribed dose). As with the brain fields, we also see a dosimetric effect of the patient geometry, i.e. his/her age. For instance, the heart, which is close to the spinal field, receives photon doses ranging from 1.0 to 5.7 mSv Gy−1 from the six fields considered assuming a 9 month old patient. However, for an adult, the scattered photon doses range only from 0.5 to 1.0 mSv Gy−1 for the six fields considered.

Table 5.

Out-of-field doses for six different spinal fields in mSv Gy−1 for organs in an 8 year old female patient assuming an IMRT treatment. Hphot is the organ equivalent dose and ΔHphot = δHphot/Hphot is the statistical error in percent.

| Female organs | Field 1 |

Field 2 |

Field 3 |

Field 4 |

Field 5 |

Field 6 |

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Hphot | Δ Hphot | Hphot | Δ Hphot | Hphot | Δ Hphot | Hphot | Δ Hphot | Hphot | Δ Hphot | Hphot | Δ Hphot | |

| Brain | 4.5 × 100 | 5.6% | 1.2 × 100 | 1.2% | 7.9 × 10−1 | 1.2% | 5.0 × 100 | 3.8% | 1.5 × 100 | 1.2% | 1.0 × 100 | 1.2% |

| Thyroid | 1.4 × 100 | 1.9% | 7.0 × 10−1 | 1.3% | 7.9 × 10−1 | 1.7% | 1.1 × 100 | 0.9% | 5.9 × 10−1 | 1.5% | 8.1 × 10−1 | 1.6% |

| Breasts | 7.7 × 10−1 | 1.5% | 6.7 × 10−1 | 1.8% | 1.3 × 100 | 1.9% | 8.6 × 10−1 | 1.4% | 7.2 × 10−1 | 1.9% | 1.3 × 100 | 1.9% |

| Esophagus | 1.1 × 100 | 1.5% | 6.5 × 10−11 | 1.6% | 1.0 × 100 | 1.5% | 1.1 × 100 | 1.4% | 7.4 × 10−1 | 1.5% | 1.1 × 100 | 1.5% |

| Lung | 1.2 × 100 | 1.9% | 9.0 × 10−1 | 2.6% | 1.7 × 100 | 2.6% | 1.2 × 100 | 1.9% | 1.0 × 100 | 2.6% | 1.9 × 100 | 2.6% |

| Uterus | 1.2 × 100 | 1.4% | 9.8 × 10−1 | 1.6% | 2.0 × 100 | 1.6% | 1.3 × 100 | 1.5% | 1.1 × 100 | 1.7% | 2.3 × 100 | 1.6% |

| Ovaries | 1.2 × 100 | 1.8% | 8.9 × 10−1 | 1.7% | 1.9 × 100 | 1.7% | 1.1 × 100 | 1.4% | 8.9 × 10−1 | 1.8% | 2.0 × 100 | 1.7% |

4. Discussion

4.1. Comparison between brain and spine fields in IMRT

In general, out-of-field doses increase as a function of field size and tumor volume. There is about a twofold increase in the absorbed scattered photon doses to the organs in the immediate vicinity of the field as the treatment field size is increased from 3 cm to 9 cm in diameter.

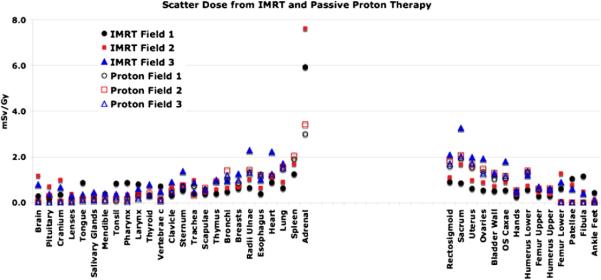

The distance between the brain field edge and the organs in the lower extremities is almost twice the distance between the spine field edge and the organs in the lower extremities. Therefore, the out-of-field doses to extremities from spine fields are in general higher than those from the brain fields. For example, gonads receive higher doses from the spine fields relative to the corresponding brain fields. In the 14 year old male phantom, the out-offield doses to prostate from brain fields are around 0.2 mSv Gy−1, whereas for the spine fields the prostate receives around 1.0 mSv Gy−1. In contrast, the thyroid receives around 0.5–2.5 mSv Gy−1 and 0.3–0.8 mSv Gy−1 when treating lesions in the brain and spine, respectively. Figure 1 shows the out-of-field doses as a function of the field index averaged over all six phantoms. Because of the location in the body, brain fields result in lower total doses compared to spine fields.

Figure 1.

Out-of-field doses from IMRT as a function of field index averaged over all phantoms. Open circles and solid squares represent brain and spine fields, respectively. The results are averaged over all segmented organs outside of the radiation field (see table 3).

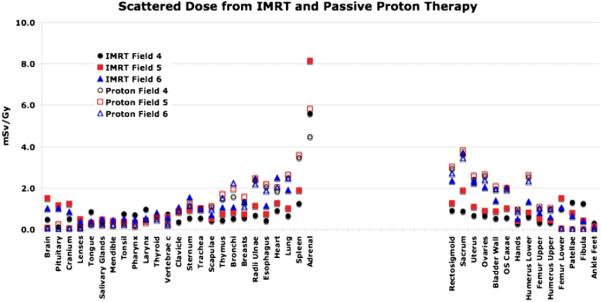

4.2. Comparison between protons therapy and IMRT fields

Figures 2 and 3 show the out-of-field doses from IMRT and the secondary neutron equivalent doses from proton therapy (Athar and Paganetti 2009) for various out-of-field organs assuming an 8 year old female for the fields given in table 1. In general, for organs near the field edge, deep-seated tumors with larger treatment volumes show higher doses compared to more shallow treatment volumes. This holds for both treatment modalities primarily due to large contribution of patient scatter. When simulating IMRT, we have matched the jaws to the MLC shape, i.e. organs close to the field edge are shielded by the collimating jaws.

Figure 2.

Out-of-field photon and neutron equivalent doses (in an 8 year old female phantom) for various organs as a function of lateral distances from the treatment site for fields 1, 2 and 3 (see table 1). Fields 1, 2 and 3 represent 3 cm, 6 cm and 9 cm diameter apertures, respectively.

Figure 3.

Out-of-field photon and neutron equivalent doses (in an 8 year old female phantom) for various organs as a function of the lateral distances from the treatment site for fields 4, 5 and 6 (see table 1). Fields 4, 5 and 6 represent 3 cm, 6 cm and 9 cm diameter apertures, respectively.

Breast cancers in women and prostate cancers in men are most prevalent. In the spine treatment fields these organs are located close to the field edge. For IMRT treatments, the out-of-field doses to breasts from the spine field 6 (assuming a 4 and an 8 year old female) are estimated to be 2.8 and 1.3 mSv Gy, respectively. The corresponding neutron equivalent doses from passive proton therapy are very similar, i.e. 2.6 and 1.2 mSv Gy (RBE) (Athar and Paganetti 2009), respectively. The prostate gland in the 11 year and the 14 year old male patients receives 1.0 and 0.8 mSv Gy from the IMRT treatment field 6. The corresponding doses to the prostate gland from the passive proton therapy are 1.2 and 1.2 mSv Gy (RBE) for the 11 year old and 14 year old male phantoms, respectively. Thus, the secondary doses are comparable.

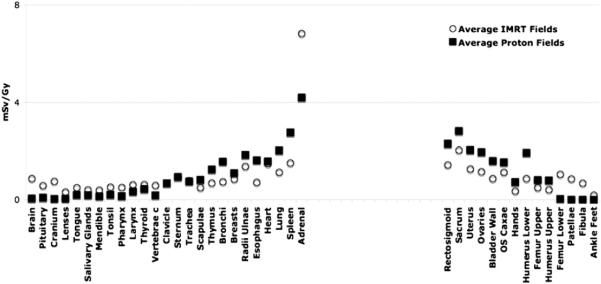

Independent of modality, large treatment volumes result in more patient scatter compared to small treatment volumes. However, the treatment head contribution decreases with the treatment volume as there is less scattering material in the beam path for the smaller field, both for IMRT and proton therapy. For example, considering 6 MV IMRT of a brain lesion in an 8 year old patient using field 1, the photon doses received by the thyroid (near the tumor site) and the kidneys (distant from the field edge) are estimated to be 0.53 and 0.3 mSv Gy−1, respectively. On the other hand, the out-of-field photon doses to thyroid and kidneys from field number 6 are found to 2.5 and 0.65 mSv Gy−1, respectively. For the largest field diameter of 9 cm (fields 3 and 6), the out-of-field IMRT doses are found to be comparable to the neutron equivalent doses from proton therapy considering similar fields. This is illustrated in figures 2 and 3. Relatively close to the field edge (but out of the main field) the secondary dose in proton therapy seems to be higher than the scattered dose in IMRT. For example, for spine fields treating an 8 year old patient, the neutron doses to the spleen (near the field egde) from proton therapy range from 2.0 to 4.0 mSv Gy−1 (RBE) as opposed to 1.0–2.0 mSv Gy−1 from similar IMRT fields. The situation turns in favor of proton therapy as the distance to the field edge is increased. The out-of-field doses from IMRT fields are higher than the neutron equivalent doses in passive scattered proton therapy for organs located at larger distances (25 cm or more) from the field edge. Photon doses resulting from head leakage at these distances are a factor of 2–3 higher compared to secondary neutron equivalent doses in proton therapy. This is illustrated in figure 4. Similarly, for cranial fields, the thyroid in the 8 year old patient receives doses around 3.0 mSv Gy−1 (RBE) from passive proton therapy as opposed to doses around 2.0 mSv Gy−1 from similar IMRT fields (averaged over all field considered). Organs at large lateral distances from the treatment fields, like ovaries and uterus, received equivalent doses around 0.005 mSv Gy−1 (RBE) from proton fields and around 1.0 mSv Gy−1 from IMRT fields considering cranial fields (averaged over all field considered). While for proton therapy the secondary doses decreases with increasing distance to the field edge, IMRT fields show a rise in the absorbed photon doses at large distances due to accelerator head leakage.

Figure 4.

Out-of-field scattered photon (open circles) and neutron equivalent doses (solid circles) averaged over all six fields considered (in an 8 year old female phantom) for various organs as a function of the lateral distance from the treatment site.

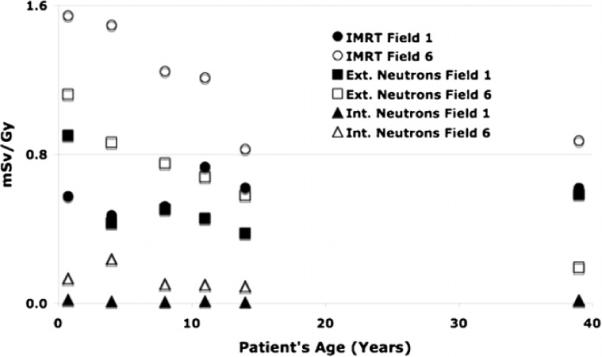

Figure 5 shows the out-of-field photon and neutron equivalent doses for spine fields as a function of the patient's age. Interestingly, for small stature patients, the secondary neutron equivalent doses are higher than the out-of-field doses in IMRT for small fields (e.g., field 1). The figure also demonstrates the importance of external neutrons compared to internal neutrons.

Figure 5.

Out-of-field photon and neutron equivalent doses as a function of the patient's age averaged over all spine fields. Field properties for field numbers 1 and 2 are listed in table 1.

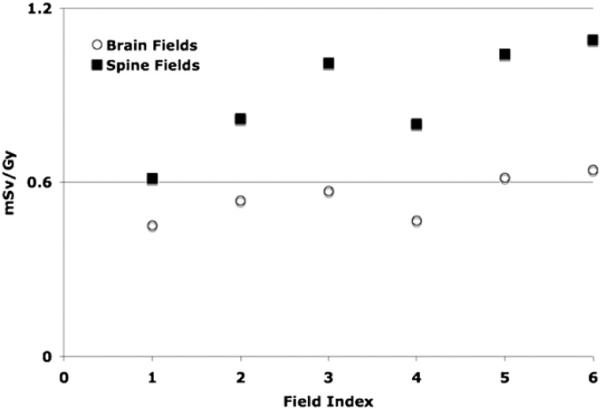

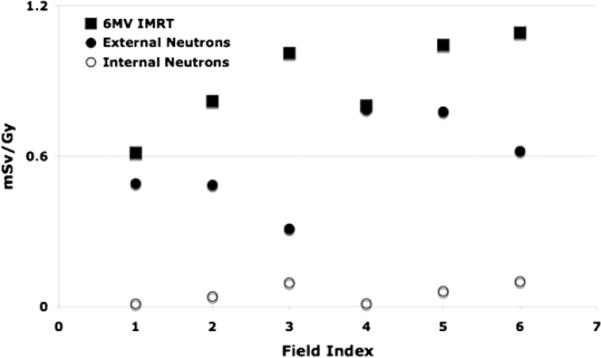

In proton therapy, the secondary neutron dose is caused by proton interactions in the treatment head and proton interactions in the patient. The treatment head contribution typically dominates (figure 5). Assuming ideal proton beam scanning (no scattering material in the beam path), we can estimate the neutron equivalent dose considering only internal neutrons (neutron produced inside the patient). Figure 6 shows a comparison between out-of-field photon (IMRT) and secondary neutron (proton therapy) equivalent doses as a function of field indices, averaged over all considered patient ages. The neutron equivalent doses (averaged over all considered out-of-field organs (see table 3)) assuming proton beam scanning delivery of field 6 range from 0.02 to 0.3 mSv Gy−1 (RBE), whereas for 6 MV IMRT the scattered doses would range from 0.8 to 1.5 mSv Gy−1. Obviously, organ doses are much lower (up to two orders of magnitude) for proton beam scanning as compared to the other two modalities, namely, passive proton therapy and IMRT.

Figure 6.

Out-of-field photon and neutron equivalent doses as a function of field index summed over out-of-field organs (see table 3) and averaged over all patient ages.

Recently, Fontenot et al (2009) have shown a comparison of second cancer risks arising from IMRT and proton therapy. A direct comparison of their results with ours is difficult. First of all, they compared risk, not dose. Second, their field characteristics are different than ours as they analyzed prostate cases. Further, they did not distinguish between the contribution from the primary radiation field and the scattered/secondary radiation field, while our analysis does focus on the latter.

4.3. Uncertainties

The estimated statistical uncertainties in most of the organ-specific doses are small and are in the range of 0.2–5%. For organs located further away from the field edge, the statistical errors can reach up to 10%. For small distant organs, these statistical errors are estimated to be around 40%. For large fields, the errors go down owing to more patient scatter. For example, the statistical errors in thyroid absorbed doses from the cranial fields 1, 2 and 3 (see table 1) with increasing diameters are estimated to be 2.9%, 1.7% and 1.3%, respectively. Additional uncertainties for the proton therapy result from radiation weighting factors. Our results are based on the application of ICRP-recommended radiation weighting factors for neutrons. The absolute values as well as the procedure are certainly not beyond dispute. Further uncertainties arise from the fact that we did not consider a full IMRT plan but delivered a nominal dose to the center of the proton therapy treatment volume. Thus, our results are valid only for an average treatment volume.

5. Conclusion

We have simulated organ-specific out-of-field photon doses considering patients of different ages treated with 6 MV IMRT for brain or spine lesions. Further, we have compared our results with secondary neutron equivalent doses in passive scattered and scanned proton therapy. The relative doses can be separated into three regions (one in-field and two out-of-field). In field, the scattered or secondary dose from proton therapy is roughly a factor of 2–3 smaller than that in IMRT (ICRU Report 78). Next, close to the field, organs receive higher secondary neutron equivalent doses from passive proton therapy relative to the scattered photon or leakage photon dose in IMRT. Further, organs located at larger distances from the field edge receive higher doses in IMRT than those in passive scattered proton therapy. Overall, protons offer a distinct advantage in-field while the out-of-field doses from proton treatments seem to be comparable to scattered doses received from 6 MV IMRT fields. Proton beam scanning would be advantageous for all regions. However, we have to keep in mind that the differences in absolute dose do not necessarily translate into similar differences in second cancer risk due to nonlinear dose–response relationships in particular at higher dose levels. A risk analysis is beyond the scope of this paper.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by institutional funds (ECOR award by Partners Health Care Inc., Ira Spiro award for translational research by the Department of Radiation Oncology at Massachusetts General Hospital (MGH)) and an NIH/NCI grant (CO6-CA059267).

References

- Agostinelli S. GEANT4—a simulation toolkit. Nucl. Instrum. Methods Phys. Res. A. 2003;506:250–303. [Google Scholar]

- Athar SB, Paganetti H. Neutron equivalent doses and associated lifetime cancer incidence risks for head & neck and spinal proton therapy. Phys. Med. Biol. 2009;54:4907–26. doi: 10.1088/0031-9155/54/16/005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bednarz B, Hancox C, Xu XG. Calculated organ doses from selected prostate treatment plans using Monte Carlo simulations and an anatomically realistic computational phantom. Phys. Med. Biol. 2009;54:5271–86. doi: 10.1088/0031-9155/54/17/013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bednarz B, Xu XG. Monte Carlo modeling of a 6 and 18 MV Varian Clinac medical accelerator for in-field and out-of-field dose calculations: development and validation. Phys. Med. Biol. 2009;54:43–57. doi: 10.1088/0031-9155/54/4/N01. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fontenot JD, Lee AK, Newhauser WD. Risk of secondary malignant neoplams from proton therapy and intensity-modulated x-ray therapy for early-stage prostate cancer. Int. J. Radiat. Oncol. Biol. Phys. 2009;74:616–22. doi: 10.1016/j.ijrobp.2009.01.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hall EJ. Intensity-modulated radiation therapy, protons, and the risk of second cancers. Int. J. Radiat. Oncol. Biol. Phys. 2006;65:1–7. doi: 10.1016/j.ijrobp.2006.01.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- ICRU ICRU Report No 78: prescribing, recording, and reporting proton-beam therapy. J. ICRU. 2007;7(No 2) [Google Scholar]

- ICRP . ICRP Publication 92. Pergamon; Oxford: 2003. Relative biological effectiveness (RBE), qualityfactor (Q), and radiation weighting factor (WR) [Google Scholar]

- Jiang H, Paganetti H. Adaption of GEANT4 to Monte Carlo dose calculations on patient CT data. Med. Phys. 2004;31:2811–8. doi: 10.1118/1.1796952. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kry SF, et al. Out-of-field photon and neutron dose equivalent from step-and-shoot intensity-modulated radiation therapy. Int. J. Radiant. Oncol. Biol. Phys. 2004;62:1204–16. doi: 10.1016/j.ijrobp.2004.12.091. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee C, Bolch W. Construction of a tomographic computational model of a 9-month old and its Monte Carlo calculation time comparison between the MCNP4C and MCNPX codes. Health Phys. 2003;84:S259. [Google Scholar]

- Lee C, Williams JL, Lee C, Bolch WE. The UF series of tomographic computational phantoms of pediatric patients. Med. Phys. 2005;32:3537–48. doi: 10.1118/1.2107067. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MCNPX . Technical Report LA-CP-02-408. Los Alamos National Laboratory; Los Alamos, NM: 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Newhauser WD, et al. The risk of developing a second cancer after receiving craniospinal proton irradiation. Phys. Med. Biol. 2009;54:2277–91. doi: 10.1088/0031-9155/54/8/002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paganetti H, Jian H, Lee S-Y, Kooy H. Accurate Monte Carlo for nozzle design, commissioning, and quality assurance in proton therapy. Med. Phys. 2004;31:2107–18. doi: 10.1118/1.1762792. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Palm A, Johansson KA. A review of the impact of photon and proton external beam radiotherapy treatment modalities on the dose distribution in field and out-of-field; implications for the long-term morbidity of cancer survivors. Acta Oncol. 2007;46:462–73. doi: 10.1080/02841860701218626. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mirabell R, et al. Potential reduction of the incidence of radiation-induced second cancers by using proton beams in the treatment of pediatric tumors. Int. J. Radiat. Oncol. Biol. Phys. 2002;54:824–9. doi: 10.1016/s0360-3016(02)02982-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Taddei PJ, Mirkovic D, Fontenot JD, Giebeler A, Zheng Y, Kornguth D, Mohan R, Newhauser WD. Stray radiation dose and second patient receiving craniospinal irradiation with proton beam. Phys. Med. Biol. 2009;54:2259–75. doi: 10.1088/0031-9155/54/8/001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xu XG, Bednarz B, Paganetti H. A review of dosimetry studies on external-beam radiation treatment with respect to second cancer induction. Phys. Med. Biol. 2008;53:193–241. doi: 10.1088/0031-9155/53/13/R01. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xu XG, Chao TC, Bozkurt A. VIP-MAN: an image-based whole-body adult male model constructed from color photographs of the Visible Human Project for multi-particle Monte Carlo calculations. Health Phys. 2000;78:476–85. doi: 10.1097/00004032-200005000-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zacharatou Jarlskog C, et al. Assessment of organ specific neutron doses in proton therapy using whole-body age-dependent voxel phantoms. Phys. Med. Biol. 2008;53:693–717. doi: 10.1088/0031-9155/53/3/012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]