Abstract

Although earlier studies have demonstrated promising effects of relationship education for military couples, these studies have lacked random assignment. The current study evaluated the short-term effects of relationship education for Army couples in a randomized clinical trial at two sites (476 couples at Site 1 and 184 couples at Site 2). At both sites, participant satisfaction with the program was high. Intervention and control couples were compared on relative amounts of pre-intervention to post-intervention change. At Site 1, not all variables showed the predicted intervention effects, although we found significant and positive intervention effects for communication skills, confidence that the marriage can survive over the long haul, positive bonding between the partners, and satisfaction with sacrificing for the marriage or the partner. However, at Site 2, we found significant and positive intervention effects for communication skills only. Possible site differences as moderators of intervention effects are discussed.

Keywords: relationship education, military couples, communication skills, sacrifice

As the Global War on Terror enters its tenth year, a great deal of public concern has focused on the stress experienced by military families. Military service, particularly in times of war, includes a number of stressors for marriage, including extended separations, frequent deployments, risk of injury and death, and frequent moves (Karney & Crown, 2007). These types of stressors, in addition to selection factors (e.g., younger age at marriage for military compared to civilian couples), may contribute to marital distress and instability for Army couples (Hogan & Seifert, 2010, Karney & Crown, 2007). While strengthening marriages has a number of positive effects in general, studies with military spouses have found that better marital functioning is strongly associated with lower stress and better coping related to deployment (Allen, Rhoades, Stanley, & Markman, in press; Orthner & Rose, 2006).

A number of programs have been developed to help military couples and families. Strong Bonds is a system of relationship support programs offered in the Army by Army Chaplains, with a number of specialized programs for unmarried soldiers, military couples, and military families, including programs on deployment and reintegration (www.strongbonds.org). Strong Bonds includes an adaptation of the Prevention and Relationship Education Program (PREP; Markman, Stanley, & Blumberg, 2010). PREP for Strong Bonds is an educational, group format program for couples designed to prevent or ameliorate marital distress and divorce by helping couples lessen risks and increase protective factors empirically related to marital outcomes. PREP for Strong Bonds teaches couples critical communication and problem solving skills, how to work more effectively together as a team, and promotes couples’ fun, friendship, and commitment. The adaptation used in the Army includes material on how to manage deployment and re-integration. While the focus on the current paper is on PREP for Strong Bonds, the findings should be relevant for other programs that teach couples similar skills and principles.

As noted above, marital quality relates to lower stress and better coping with military stressors. Thus, learning skills and principles associated with having a happy marriage could help Army couples cope with a range of stressors and adjustments, and help maintain strong relationships, even during deployment. For example, having strong communication skills is important during deployment, as modern technology allows frequent and/or interactive communication such as email, instant messaging, phone calls, and video chat. Thus, communication and conflict management skills can affect the day-to-day life of a military couple, even while partners are geographically separated.

The general literature on couple education suggests that couple education is an effective approach to strengthening marriages (Hawkins, Blanchard, Baldwin, & Fawcett, 2008). Additionally, there have been a number of specific studies focused on PREP and variations of PREP. The preponderance of evidence shows a range of positive effects of variations of PREP (e.g., Halford, Markman, Kline, & Stanley, 2003), resulting in PREP being classified as an efficacious marriage enrichment program (Institute of Medicine, 1994; Jakubowski, Milne, Brunner, & Miller, 2004) that is listed in the SAMHSA National Registry of Promising Practices.

While this literature is encouraging, there has been limited evaluation of the effects of couple education for military couples in particular. The impact of an earlier version of PREP for Strong Bonds on Army couples was evaluated by Stanley et al. (2005). The intervention showed positive pre-post effects on a range of marital variables, such as improved relationship satisfaction, communication, and confidence in the marriage to survive over time. These positive effects held for husbands and wives, racially and ethnically diverse couples, and couples of different incomes. However, this study lacked a control group, making it difficult to isolate intervention effects from confounding variables such as time and Hawthorne effects. It also did not have randomized assignment, raising the issue of selection effects.

The current study presents outcome data from a larger, randomized clinical trial of PREP for Strong Bonds delivered to Army couples by Army Chaplains. In addition to being an important extension of Stanley et al.’s (2005) earlier investigation, this study also is an important contribution to the general literature on couples education by including both a diverse sample and a wide array of measures that reflect the dimensions targeted in the intervention. In their reviews of the field, Hawkins et al. (2008) and Markman and Rhoades (2010) note the need for studies of couple education to include diverse couples and to expand the outcomes assessed beyond satisfaction and communication, to other important aspects of marriage such as commitment, sacrifice, and forgiveness.

We evaluated the intervention for Army couples at two separate Forts (Site 1 and Site 2). We present pre to post findings, comparing the group receiving PREP for Strong Bonds with a control group in a randomized controlled trial on a variety of relationship outcomes and satisfaction with the program. Overall, we hypothesize that couples will report satisfaction with the program, and that couples assigned to the intervention will manifest greater improvements in relationship functioning relative to control couples over the same period of time.

Method: Site 1

Procedures

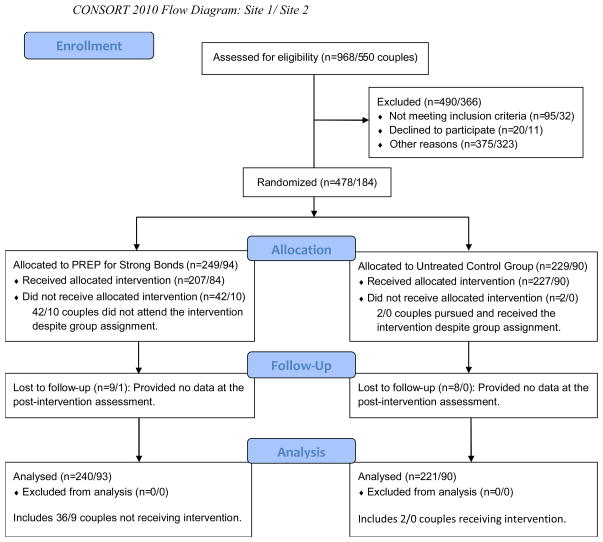

A detailed review of procedures, participants, and the intervention for Site 1 can be found in Stanley et al. (2010). In brief, to be eligible for the study, couples had to be married, age 18 or over, fluent in English, with at least one spouse in active duty with the Army. Couples could not have already participated in PREP for Strong Bonds, and they had to be willing to be randomly assigned to intervention or to an untreated control group, which can be considered treatment as usual. Recruitment was conducted via brochures, media stories, posters, and referrals from chaplains. Prior to the intervention, couples completed baseline (pre) questionnaires under the supervision of study staff. After the couple completed pre-assessment, they were randomly assigned to the intervention group or the control group. In total, 249 couples were assigned to intervention and 229 were assigned to the control group. There were a total of 22 iterations of the intervention (that is, 22 repetitions of the program to accommodate multiple groups of couples). As much as possible, couples were assigned to an iteration led by their unit chaplain. After the intervention was complete, all couples completed another set of measures for post-assessment (post), also under the supervision of study staff. Figure 1 presents the flow chart for this study using the Consolidated Standards of Reporting Trials (CONSORT) guidelines for presentation of randomized trials (Moher, Schulz, & Altman, 2001). As seen in this figure, only 17 couples did not complete the post assessment at Site 1. Recruitment, enrollment, all iterations of the intervention, and pre and post assessments were conducted in 2007.

Figure 1.

CONSORT 2010 Flow Diagram: Site 1/ Site 2

Intervention

The intervention group received the latest version of PREP for Strong Bonds. The workshop structure consisted of two parts: a one-day training on post followed by a weekend retreat at a hotel off post with a total of 14.4 hours of content. Modules included communication and affect management skills, insights into relationship dynamics, principles of commitment, fun and friendship, forgiveness, sexuality, and deployment/reintegration issues. In addition to the standard training all Army Chaplains receive in PREP, the research team provided supplementary training regarding this latest version of PREP for Strong Bonds and all intervention materials (a detailed, scripted leader manual, PowerPoint slides, couple manuals, exercises, and video/audio components). Chaplains were asked not to significantly deviate from the manual either in terms of omitting material or adding extraneous material. There were no coaches, although chaplains often circulated during exercises to support couples’ practice.

In order to be able to code fidelity to the intervention, chaplains were instructed to record all portions of the intervention. However, not all portions were recorded, sometimes due to technical difficulties with the equipment and sometimes due to chaplain oversight. A total of 17 out of the 22 interventions were considered codable. Four lessons were selected for each iteration: the speaker/listener skills lesson (a core skills set) plus 3 other lessons chosen at random across the intervention. Each iteration’s selected lessons were rated for quality and adherence. The overall rating of the chaplain’s fidelity to the lesson material was coded, from 1 (Very poor) to 5 (Excellent). The inter-rater correlation for coding fidelity was .88, and the average fidelity rating was 3.98.

Participants

At the baseline (pre) assessment, husbands averaged 27.6 years of age (SD = 5.7); wives 26.9 (SD = 6.0). Seventy-one percent of wives were white non-Hispanic, 11% were Hispanic, 9% African American, 2.5% Native American/Alaska Native, 1% Hawaiian or Pacific Islander, and 4% endorsed mixed race/ethnicity. Sixty-nine percent of husbands were white non-Hispanic, 13% were Hispanic, 10% African American, 1.5% Native American/Alaska Native, 1% Asian, 1% Hawaiian or Pacific Islander, and 5% endorsed mixed race/ethnicity. Forty percent of the couples had one or both partners who were members of a minority group. Almost all husbands (97.5%) were Active Duty Army (2.5% were in the study due to the wife being Active Duty Army), whereas almost all wives (91%) were civilian spouses of Active Duty Army males (9% of wives were Active Duty Army or Reserves). Husbands’ modal income (endorsed by 36.8% of men) was between $20,000 and $29,999 a year, while wives’ modal income (endorsed by 69.8% of women) was under $10,000 a year. High school or an equivalency degree was the modal highest degree (67.8% of the husbands and 56.7% of wives). Couples had been married an average of 4.5 years, and 70% reported at least one child living with them at least part time. Sixty-nine percent of the males in the sample experienced a deployment in the year prior to pre-assessment.

Measures

Abbreviated versions of previously established measures of marital functioning were often used to minimize subject burden, but all measures described below demonstrated adequate relevant psychometrics in the current sample (e.g., internal consistency, logical convergence among constructs). Additional details regarding any measure listed below are available from the first author.

Participants’ evaluation of program

For couples who attended the intervention, husbands and wives were asked to evaluate the program with a number of questions regarding positive program impact, program enjoyment, program helpfulness, overall satisfaction, whether they would recommend the program to a friend, and leader quality.

Marital satisfaction

The Kansas Marital Satisfaction Scale (KMS; Schumm et al., 1986) was used to assess marital satisfaction. This is a brief (3-item) scale assessing satisfaction with the marriage, the partner as a spouse, and the relationship with spouse. This scale has strong reliability and validity (Schumm et al.) and provides a pure global satisfaction rating without including other aspects of relationship functioning, which has been considered a potential problem with more omnibus measures of relationship adjustment (Fincham & Bradbury, 1987).

Communication skills

From the larger Communication Skills Test (Saiz & Jenkins, 1995), ten items were employed to measure the type of communication skills taught in PREP and other similar relationship education programs, while avoiding the specific jargon of PREP (e.g., “speaker-listener skills”). Example statements include “When discussing issues, I allow my spouse to finish talking before I respond,” “When our discussions begin to get out of hand, we agree to stop them and talk later.” Studies support the reliability and validity of this measure (Stanley et al., 2001; Stanley et al., 2005).

Confidence

Five items from the Confidence Scale (Stanley, Hoyer & Trathen, 1994) were selected to assess participants’ level of confidence in their marital strength and stability. Example items are “I believe we can handle whatever conflicts will arise in the future” and “I am very confident when I think of our future together.” The larger scale has shown good evidence of reliability and validity (e.g., Kline et al., 2004; Whitton, Rhoades, Stanley, & Markman 2008); these items are representative of the larger scale.

Positive bonding

The Positive Bonding Scale was adapted from the Couple Activities Scale (Markman, 2000). It consists of 9 questions assessing the friendship, intimacy, fun, felt support, and sensual/sexual relationship of the couple. Example questions include “We regularly have conversations where we just talk as good friends,” “We have a satisfying sensual or sexual relationship,” “I feel emotionally supported by my partner,” and “We regularly make time for fun activities together as a couple.” Stanley, Whitton, Kline, and Markman (2006) report logical convergence of the parent scale with other indices of individual and marital functioning.

Dedication

Based on the Dedication Scale from the multidimensional Commitment Inventory (Stanley & Markman, 1992), five items reflecting couple identity, long term view, and priority of the relationship were selected. Example items are: “My relationship with my spouse is more important to me than almost anything else in my life.” And “I want this relationship to stay strong no matter what rough times we may encounter.” Studies support the reliability and validity of variations of this scale (e.g., Stanley, Whitton, & Markman, 2004; Whitton et al., 2008).

Satisfaction with sacrifice

To assess this construct, we utilized three items from the Satisfaction with Sacrifice Scale, which is also part of the Commitment Inventory (Stanley & Markman, 1992). Items reflect positive feelings and satisfaction derived from sacrificing for the spouse (e.g., “It makes me feel good to sacrifice for my spouse”). The parent measure converges as expected with other relationship constructs; for example, predicting future marital adjustment and mediating the relationship between male dedication levels and future marital adjustment (Stanley, Whitton, Low, Clements, & Markman, 2006).

Forgiveness

4 items from the 6 item Marital Forgiveness Scale (Fincham & Beach, 2002) were used. We used 2 of the 3 positive items (When my partner wrongs me, I just accept their humanness, flaws and failures; I am quick to forgive my partner) and 2 of the 3 negative items (I think about how to even the score when my partner wrongs me; If my partner treats me unjustly, I think of ways to make them regret what they did.)

Negative communication

The 4-item version of the Communication Danger Signs Scale (Stanley & Markman, 1997) was used to assess problematic communication patterns. Items reflect escalation (“Little arguments escalate into ugly fights with accusations, criticisms, name calling, or bringing up past hurts”), invalidation (“My spouse criticizes or belittles my opinions, feelings, or desires.”), negative interpretation (“My spouse seems to view my words or actions more negatively than I mean them to be.”), and withdrawal (“When we argue, one of us withdraws…that is, does not want to talk about it anymore, or leaves the scene.”). Forms of this measure have demonstrated convergence with other theoretically related constructs and predicted changes subsequent to communication skill interventions (e.g., Stanley et al., 2005).

Results

Participants’ evaluation of program

Participants generally accepted the program very well, with average high ratings of the program as impactful, helpful, and enjoyable, and average high satisfaction with the program. Across these dimensions, the overall rating was 6.12 on a 7 point scale where higher scores indicate more positive impact. The average leader quality rating was 4.13 based on a scale from 1 (needs improvement) to 5 (excellent).

Intent to treat analyses

The analyses examining changes from pre to post were examined by a 2 (gender) by 2 (time) repeated measures analysis of variance (ANOVA), with both time and gender treated as within-subjects factors (hence, dependency among partners is accounted for by treating gender as a repeated measurement). Group (i.e., PREP for Strong Bonds versus Control) is a between-subjects factor. This analytic approach handles any group differences at pre-assessment by simply comparing amount of change from the respective baseline scores. Couples were analyzed according to the group they were assigned to, regardless of whether they actually did or did not attend the intervention, consistent with rigorous intent-to-treat procedures (Hollis & Campbell, 1999). This method of analysis preserves the random assignment of the groups. Figure 1 shows the number of couples assigned to Strong Bonds who did not attend any part of the program (17%), as well as the number of control couples who actually ended up attending the program (1%).

For the current paper, we were uninterested in pure time effects (i.e., whether or not the variable changes over time collapsed across group and gender) or gender effects (i.e., whether or not the absolute levels of the variable differ for men and women, collapsed across time and group). Rather, the primary effect of interest for the current paper is the time by group interaction. A significant time by group interaction would indicate that the change from pre to post is different for the intervention group compared to the change for the control group. Although this is not a central focus of the paper, we also evaluated the time by group by gender interaction to check on gender as a moderator of effects. Hawkins et al. (2008) found that gender effects in relationship education research are not substantial overall.

Table 1 provides the means for husbands and wives, pre and post, for the two groups, as well as results for the time by group interaction effect for the relationship outcomes analyzed using intent to treat groups. For those variables where a significant (or trend) time by group effect was found, we also present effect sizes for husbands and wives from pre to post for the two groups. As hypothesized, significant time by group interaction effects were found for communication skills, confidence, positive bonding, and satisfaction with sacrifice. There was also a trend for marital satisfaction. As evident in Table 1, at times the interaction effect indicated that the PREP for Strong Bonds group improved more from pre to post relative to the Control group (trend for marital satisfaction, significantly for communication skills), whereas other times the interaction effect indicated that the PREP for Strong Bonds group improved slightly or maintained levels of the construct, while the Control group declined from pre to post (confidence, positive bonding, satisfaction with sacrifice). However, contrary to hypotheses, forgiveness, dedication, and negative communication did not manifest significant interaction effects. Although only positive bonding manifested a significant 3-way gender by time by group effect, wherein only control men declined from pre to post, the power to detect significant 3 way interactions is relatively low. The effect sizes in Table 1 suggest the relative decline for control men was also evident in confidence.

Table 1.

Means and (standard deviations) for Site 1 before and after intervention

| PREP for Strong Bonds | Control | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||||||||

| Husbands | Wives | Husbands | Wives | Time by Group | |||||

|

| |||||||||

| Pre | Post | Pre | Post | Pre | Post | Pre | Post | F (1,457)/Overall d | |

| Marital Satisfaction | 5.63 (1.26) | 5.78 (1.25) | 5.56 (1.30) | 5.81 (1.18) | 5.94 (1.11) | 5.92 (1.13) | 5.64 (1.38) | 5.79 (1.37) | 3.49+/ .11 |

| d = .12 | d = .20 | d = − .02 | d = .11 | ||||||

|

| |||||||||

| Communication Skills | 3.98 (1.13) | 4.39 (1.22) | 4.06 (1.19) | 4.38 (1.22) | 4.25 (1.12) | 4.37 (1.06) | 4.12 (1.16) | 4.28 (1.09) | 11.27**/.20 |

| d = .35 | d = .27 | d = .11 | d = .14 | ||||||

|

| |||||||||

| Confidence | 5.99 (1.10) | 6.03 (1.05) | 5.94 (1.26) | 5.99 (1.15) | 6.21 (1.00) | 6.07 (1.11) | 6.06 (1.05) | 6.02 (1.18) | 4.16*/.11 |

| d = .04 | d = .04 | d = −.13 | d = −.04 | ||||||

|

| |||||||||

| Positive Bonding | 5.44 (1.07) | 5.48 (1.07) | 5.52 (1.26) | 5.54 (1.18) | 5.78 (.97) | 5.58 (1.06) | 5.59 (1.14) | 5.60 (1.18) | 4.38*/.11 |

| d = .04 | d = .02 | d = − .20 | d = .01 | ||||||

|

| |||||||||

| Forgiveness | 5.32 (1.18) | 5.32 (1.11) | 5.22 (1.21) | 5.23 (1.09) | 5.37 (1.21) | 5.42 (1.10) | 5.24 (1.22) | 5.32 (1.17) | .86/−.05 |

|

| |||||||||

| Dedication | 6.50 (.75) | 6.45 (.81) | 6.59 (.73) | 6.54 (.76) | 6.56 (.70) | 6.43 (.83) | 6.59 (.62) | 6.48 (.76) | 2.48/.09 |

|

| |||||||||

| Satisfaction with Sacrifice | 5.96 (1.03) | 5.96 (1.00) | 6.04 (1.01) | 6.02 (.99) | 6.21 (.87) | 6.08 (.98) | 6.04 (.97) | 5.89 (1.07) | 4.79*/.13 |

| d = .00 | d =− .02 | d = −.14 | d = −.15 | ||||||

|

| |||||||||

| Negative communication | 2.00 (.51) | 1.93 (.49) | 1.88 (.52) | 1.88 (.52) | 1.85 (.50) | 1.81 (.51) | 1.86 (.54) | 1.84 (.53) | .06/−.01 |

= p < .10,

= p < .05,

= p < .01

d = In columns for husband and wife values, Cohen’s d was calculated comparing magnitude of changes for pre to post values for husbands and wives in PREP and Control condition. “Overall d” represents the overall effect size of the intervention on the target variable.

Method: Site 2

While we had a large sample from Site 1, we became aware of the opportunity to run the study at a second site where the couples would be trained by a small group of highly trained family life chaplains and where the couples were not as exposed to the stress of ramping up for a deployment due to the surge (the conditions at Site 1). The conditions at the base, the delivery of the intervention, and the couple demographics were different enough for the two sites to warrant examining them separately.

Procedures

The Site 2 sample was smaller than the Site 1 sample. A total of 184 couples participated: 94 assigned to intervention and 90 assigned to control (see Figure 1; note only 1 couple did not complete the post assessment). At this site we followed most of the methods used at Site 1. Specifically, eligibility requirements, recruitment procedures, assessment procedures, measures, and the intervention design and materials were as described above. Measures continued to demonstrate adequate psychometrics in this second sample. At Site 2, recruitment, enrollment, all iterations of the intervention, and pre and post assessments were conducted in 2008, a year after this phase was conducted at Site 1.

Another difference between sites was in the delivery of the interventions. At Site 1, research couples were included in the naturally occurring iterations of PREP for Strong Bonds being conducted by unit chaplains on base (thus, study couples were included along with other non-study couples in any given iteration and typically led by their unit chaplain). At Site 2, the research team worked closely with the LTC Chaplain who served as Director of the Family Life Chaplain Training Center at the site, as well as the Family Ministries Action Officer at the Office of the Chief of Chaplains in the Pentagon, to provide four unique study iterations of PREP for Strong Bonds, where only couples enrolled in the study attended. The Director of the Family Life Chaplain Training Center was one of the primary leaders in all four iterations, along with 10 other Family Life Chaplains trained in the intervention. Relationship skills coaches (approximately 1 coach per 3 to 5 couples) also rotated through the workshops at Site 2 to help couples as they practiced the exercises and skills. As at Site 1, a sampling of recorded iterations were coded for fidelity to the intervention on a scale from 1 (Very poor) to 5 (Excellent), with good inter-rater reliability. The average fidelity rating was 4.75, which showed a trend to be higher than the fidelity rating for Site 1 (t(18) = 1.88, p = .08).

Participants

At the baseline (pre) assessment, husbands averaged 31 years of age (SD = 6.04); wives 30 (SD = 6.12). Thirty nine percent of the couples had one or both partners who were members of a minority group. Seventy-one percent of wives were white non-Hispanic, 12% were Hispanic, 11.4% African American, 1.6% were Asian American, .5% Hawaiian or Pacific Islander, and 3.3% endorsed mixed race/ethnicity. Seventy percent of husbands were white non-Hispanic, 10.3% were Hispanic, 13.6% African American, 1.1% Native American/Alaska Native, 1.6% Asian, and 3.8% endorsed mixed race/ethnicity. Most couples (92.4%) consisted of an active duty husband with a civilian wife. Almost all husbands (96.7%) were active duty Army (2.2% were in the study due to the wife being Active Duty Army), whereas almost all wives (92.9%) were civilian spouses of Active Duty Army males (6% of wives were active duty Army or Reserves). In this sample, most husbands (54.4%) earned between $30,000 and $49,999 per year, while wives’ modal income (endorsed by 61.7% of women) was under $10,000 a year. High school or an equivalency degree was the modal highest degree (54.1% of the husbands and 43.5% of wives). Couples had been married an average of 5.6 (SD = 4.85) years, and 80.4% reported at least one child living with them at least part time. Forty-six percent of the males in the sample experienced a deployment in the year prior to pre-assessment.

Thus, relative to the sample at Site 1, the sample at Site 2 was significantly older, married longer, with higher income and husband military rank (all verified by independent samples t-tests, p < .01), and with lower rates of recent deployment (χ2 = 29.18, p < .001). This is consistent with the nature of the couples available for participation in the study at the two sites. That is, Site 2 is a major training installation, where many of the junior enlisted are there for training and are not allowed to bring their spouses. Those available for participation were mostly drill sergeants, instructors, soldiers in the Ranger Regiment (a more senior regiment), and senior enlisted soldiers or officers in training programs where spouses can accompany them. Thus, these individuals are typically more senior and involved in training operations than the population assessed at Site 1. While couples at Site 2 differed from couples at Site 1 in these contextual and socio-demographic variables, they did not differ from couples at Site 1 on baseline levels of the measured relationship constructs (with the exception of husbands at Site 2 reporting higher levels of baseline forgiveness, (t (659) = 2.95, p < .01).

Results

Participants’ evaluation of program

As with Site 1, participants generally accepted the program very well, with average program ratings of 6.05 (on same 7 point scale) and average leader quality rating was 4.31 (on same 5 point scale).

Intent to treat analyses

These analyses were conducted in the same manner as described for Site 1 (see Table 2). A time by group interaction was found only for communication skills, in which couples assigned to the intervention increased significantly more in these skills relative to control couples. There was a trend for forgiveness, in which couples assigned to the intervention increased while control couples declined slightly. There were no significant 3 way (gender by time by group) interaction effects, although again this is partly a function of low power for detecting 3 way interaction effects. For example, in forgiveness it does appear the trend is attributable to Strong Bonds wives increasing while control husbands decrease. In no case did intervention appear related to worsened functioning over time relative to control couples. There were some significant time effects wherein intervention and control couples both improved significantly over time (i.e., significant increases in marital satisfaction and positive bonding over time, significant declines in negative communication over time).

Table 2.

Means and (standard deviations) for Site 2 before and after intervention

| PREP for Strong Bonds | Control | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||||||||

| Husbands | Wives | Husbands | Wives | Time by Group | |||||

|

| |||||||||

| Pre | Post | Pre | Post | Pre | Post | Pre | Post | F (1,180)/Overall d | |

| Marital Satisfaction | 5.71 (1.14) | 6.00 (1.06) | 5.72 (1.31) | 5.90 (1.27) | 5.79 (1.16) | 6.00 (1.02) | 5.58 (1.34) | 5.78 (1.27) | .14/.03 |

|

| |||||||||

| Communication Skills | 4.00 (1.20) | 4.40 (1.19) | 4.14 (1.12) | 4.63 (1.15) | 4.08 (1.17) | 4.22 (1.08) | 4.13 (1.18) | 4.26 (1.19) | 9.43**/.27 |

| d = .34 | d = .43 | d = .12 | d = .11 | ||||||

|

| |||||||||

| Confidence | 6.03 (1.05) | 6.08 (1.05) | 6.03 (1.23) | 6.14 (1.24) | 6.12 (1.09) | 6.20 (.88) | 5.92 (1.27) | 5.96 (1.26) | .06/.02 |

|

| |||||||||

| Positive Bonding | 5.56 (1.09) | 5.62 (1.04) | 5.57 (1.20) | 5.68 (1.26) | 5.62 (1.07) | 5.69 (.98) | 5.38 (1.34) | 5.51 (1.22) | .02/−.01 |

|

| |||||||||

| Forgiveness | 5.59 (1.09) | 5.58 (.97) | 5.03 (1.26) | 5.30 (1.09) | 5.67 (.98) | 5.51 (1.03) | 5.28 (1.20) | 5.34 (1.10) | 3.38+/.17 |

| d = −.01 | d = .23 | d = −.16 | d = .05 | ||||||

|

| |||||||||

| Dedication | 6.54 (.58) | 6.49 (.67) | 6.57 (.64) | 6.51 (.96) | 6.66 (.47) | 6.53 (.55) | 6.55 (.80) | 6.56 (.66) | .01/−.01 |

|

| |||||||||

| Satisfaction with Sacrifice | 6.13 (.75) | 6.19 (.86) | 6.03 (.93) | 6.15 (.98) | 6.13 (.84) | 6.12 (.95) | 5.95 (.99) | 5.94 (.90) | 1.39/.11 |

|

| |||||||||

| Negative communication | 1.99 (.57) | 1.88 (.50) | 1.86 (.53) | 1.82 (.53) | 2.01 (.57) | 1.83 (.49) | 1.97 (.57) | 1.88 (.54) | 1.54/−.11 |

= p < .10,

= p < .01

d = In columns for husband and wife values, Cohen’s d was calculated comparing magnitude of changes for pre to post values for husbands and wives in PREP and Control condition. “Overall d” represents the overall effect size of the intervention on the target variable.

Discussion

The current paper examined effects of PREP for Strong Bonds, as delivered by Army chaplains, for couples with at least one active duty Army spouse. We examined this question for samples at two different sites. For both samples, chaplains evidenced good adherence to the intervention curriculum, and couples’ satisfaction with the program and leader appeared high. The procedures employed here included the most systematic analysis of adherence by instructors of any prior study of PREP in a community based setting. The high fidelity ratings suggest the chaplains were well able to present the materials as intended by the developers.

The main focus of the current paper was analyses of changes over time for couples randomly assigned to PREP for Strong Bonds as compared to changes over time for couples randomly assigned to a no treatment control group. In the sample of couples from Site 1, we found significant and positive intervention effects for communication skills, confidence that the marriage can survive over the long haul, positive bonding between the couple (e.g., fun, friendship, intimacy), and satisfaction with sacrificing for the marriage and partner. However, we did not see unique intervention effects for forgiveness, dedication, and negative communication.

These initial positive findings are consistent with earlier, uncontrolled, pilot work on PREP with Army couples (Stanley et al., 2005), as well as other analyses showing that, 1 year after the intervention, these couples at Site 1 assigned to the intervention have a significantly lower divorce rate compared to couples assigned to the control group (Stanley et al., 2010). Marital status data one year after intervention were available for Site 1 prior to the data sets required for the current study. That is, the positive findings on self-report at the post intervention assessment for couples at Site 1 may be the precursor to the reductions in divorce seen one year later for this sample. Future reports with long-term analyses of all of these self-report variables will investigate such questions.

Our second site showed positive effects of the intervention relative to the control condition on the types of communication skills taught in the intervention. However, the other relationship constructs evaluated here did not show significant intervention effects. In general, the literature on relationship education suggests that the context in which relationship education is offered, and the participant characteristics of those attending the program, often affects outcomes. We observed some differences at the two sites in terms of the type of base and the demographics of participants. Specifically, the couples at Site 2 were more established, older, with less deployment; these may be markers for less stress and risk. As such, the group at Site 2 may have shown less effect for the intervention, in the short run, because those couples simply needed the intervention less than those at Site 1 who were mostly members of a highly active combat unit that was heavily involved in the surge and other combat missions. This interpretation is consistent with recommendations by Halford et al. (2003) that higher risk couples benefit more from relationship education and that therefore scarce intervention resources be aimed at high risk couples. In the present case, while the couples at Site 1 do not score lower on relationship quality than couples at Site 2, they are in what we can only presume is a much more stressful context, which could raise their risks. Recall that some of the intervention effects at Site 1 related more to preserving marital adjustment (rather than increasing levels of adjustment), which may be consistent with the notion that the intervention provided support for these couples during a stressful time (e.g., high operational tempo and impending deployment). Even though the same range of intervention effects did not emerge at Site 2 at post-assessment, there was no case in which the intervention seemed to be associated with worse functioning over time for couples. The goals of prevention are long-term, and Blanchard et al. (2009) found evidence that relationship education can prevent deterioration in communication skills for non-distressed couples when measured at longer follow ups. While Blanchard et al. review preliminary, promising data regarding effects of relationship education over time, they note the need for additional long term data on relationship education outcomes. Our future investigations will evaluate longer term outcomes of this intervention with these samples, as well as potential moderators of effects. One potential moderator to examine in future investigations is race/ethnicity; although our sample overall was relatively diverse, we did not examine effects separately for diverse couples. There has been concern in the Relationship Education field about the extent to which programs have positive impacts on couples from diverse racial/ethnic backgrounds (Hawkins et al., 2008), although a growing body of studies that suggests that relationship education and support interventions are just as effective for minority participants as others (e.g., Wood et al., 2010), as well as potentially for couples with lower incomes (Hawkins & Fackrell, 2010; Stanley et al., 2006).

There are a number of important limitations of this study. The impacts assessed are limited to short-term, pre/post, effects, for what is inherently an intervention designed to lead to longer term preventive effects. In addition, the outcomes reported here are entirely based on self-report measures. Not only does this mean that method variance may influence the findings, but self report measures often show smaller effects of relationship education relative to observational assessments (Blanchard et al., 2009; Fawcett et al., 2010).

Overall, this study represents a number of significant methodological strengths. It uses random assignment and the most conservative and rigorous model of analysis for testing the intervention that has been disseminated in a naturalistic setting. Given the community setting, the internal validity of this study is high. There was good attendance from couples assigned to the intervention (cf. Wood et al., 2010), strong procedural adherence from instructors, and outcome data from virtually every participant. The sample was large and diverse, and the constructs assessed encompassed a number of key variables associated with relationship health over time. Thus, we have a strong foundation for continuing to assess intervention effects over time, and moderators of such effects, for these Army couples as they continue to experience the stressors of combat and deployment and/or move on to other Army assignments and civilian life.

Acknowledgments

This research is funded by a grant from The National Institute of Child Health and Human Development, awarded to Scott Stanley, Howard Markman, and Elizabeth Allen (R01HD48780). The contents are solely the responsibility of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official views of NIH or NICHD.

References

- Allen E, Rhoades GK, Stanley SM, Markman HJ. Hitting home: Relationships between recent deployment, post traumatic stress symptoms, and marital functioning for Army couples. Journal of Family Psychology. 2010;24:280–288. doi: 10.1037/a0019405. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blanchard VL, Hawkins AJ, Baldwin SA, Fawcett EB. Investigating the effects of marriage and relationship education on couples’ communication skills: A meta-analytic study. Journal of Family Psychology. 2009;23:203–214. doi: 10.1037/a0015211. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fawcett E, Hawkins A, Blanchard V, Carroll J. Do premarital education programs really work? A meta-analytic study. Family Relations: An Interdisciplinary Journal of Applied Family Studies. 2010;59(3):232–239. [Google Scholar]

- Fincham FD, Beach SRH. Forgiveness in marriage: Implications for psychological aggression and constructive communication. Personal Relationships. 2002;9(3):239–251. [Google Scholar]

- Fincham FD, Bradbury TN. The assessment of marital quality: a reevaluation. Journal of Marriage and the Family. 1987;49:797–809. [Google Scholar]

- Halford WK, Markman HJ, Kline GH, Stanley SM. Best practice in couple relationship education. Journal of Marital and Family Therapy. 2003;29(3):385–406. doi: 10.1111/j.1752-0606.2003.tb01214.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hawkins AJ, Blanchard VL, Baldwin SA, Fawcett EB. Does marriage and relationship education work? A meta-analytic study. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2008;76:723–734. doi: 10.1037/a0012584. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hawkins AJ, Fackrell TA. Does relationship and marriage education for lower-income couples work? A meta-analytic study of emerging research. Journal of Couple & Relationship Therapy. 2010;9:181–191. [Google Scholar]

- Hogan PF, Seifert RF. Marriage and the military: Evidence that those who serve marry earlier and divorce earlier. Armed Forces & Society. 2010;36:420–438. [Google Scholar]

- Hollis S, Campbell F. What is meant by intention to treat analysis? Survey of published randomised controlled trials. British Medical Journal. 1999;319:670– 674. doi: 10.1136/bmj.319.7211.670. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Institute of Medicine. Reducing risk factors for mental disorders: Frontiers for preventive intervention research. Washington, D.C: National Academy Press; 1994. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jakubowski SF, Milne EP, Brunner H, Miller RB. A review of empirically supported marital enrichment programs. Family Relations: An Interdisciplinary Journal of Applied Family Studies. 2004;53(5):528–536. [Google Scholar]

- Karney BR, Crown JS. Families under stress: An assessment of data, theory, and research on marriage and divorce in the military. Santa Monica, CA: Rand Co; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Kline GH, Stanley SM, Markman HJ, Olmos-Gallo PA, St Peters M, Whitton SW, Prado LM. Timing is everything: Pre-engagement cohabitation and increased risk for poor marital outcomes. Journal of Family Psychology. 2004;18(2):311–318. doi: 10.1037/0893-3200.18.2.311. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Markman H. Unpublished measure. University of Denver; 2000. Couple Activities Scale. [Google Scholar]

- Markman H, Rhoades G. Relationship Education Research: Current Status and Future Directions. (under review) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Markman H, Stanley S, Blumberg S. Fighting for Your Marriage: A Deluxe Revised Edition of the Classic Best-seller for Enhancing Marriage and Preventing Divorce. Jossey-Bass; San Francisco, CA: 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Moher D, Schulz KF, Altman DG. The CONSORT Statement: Revised recommendations for improving the quality of reports of parallel-group randomized trials. Annuls of Internal Medicine. 2001;134:657–662. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-134-8-200104170-00011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Orthner DK, Rose R. Deployment and separation adjustment among Army civilian spouses. Washington, DC: Army Research Institute for the Behavioral and Social Sciences; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Saiz CC, Jenkins N. Unpublished measure. University of Denver; 1995. The Communication Skills Test. [Google Scholar]

- Schumm WR, Paff-Bergen LA, Hatch RC, Obiorah FC. Concurrent and discriminant validity of the Kansas Marital Satisfaction Scale. Journal of Marriage & the Family. 1986;48(2):381–387. [Google Scholar]

- Stanley SM, Allen ES, Markman HJ, Rhoades GK, Prentice D. Decreasing divorce in Army couples: Results from a randomized clinical trial of PREP for Strong Bonds. Journal of Couple and Relationship Therapy. 2010;9:149–160. doi: 10.1080/15332691003694901. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stanley SM, Allen ES, Markman HJ, Saiz CC, Bloomstrom G, Thomas R, Baily AE. Dissemination and evaluation of marriage education in the Army. Family Process. 2005;44:187–201. doi: 10.1111/j.1545-5300.2005.00053.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stanley SM, Amato PR, Johnson CA, Markman HJ. Premarital education, marital quality, and marital stability: Findings from a large, random, household survey. Journal of Family Psychology. 2006;20:117–126. doi: 10.1037/0893-3200.20.1.117. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stanley SM, Hoyer Trathen DW. Unpublished measure. University of Denver; 1994. Confidence Scale. [Google Scholar]

- Stanley SM, Markman HJ. Assessing commitment in personal relationships. Journal of Marriage & the Family. 1992;54(3):595–608. [Google Scholar]

- Stanley SM, Markman HJ. Marriage in the 90s: A nationwide random phone survey. Denver, Colorado: PREP, Inc; 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Stanley SM, Markman HJ, Prado LM, Olmos-Gallo PA, Tonelli L, St Peters M, Whitton SW. Community-based premarital prevention: Clergy and lay leaders on the front lines. Family Relations: An Interdisciplinary Journal of Applied Family Studies. 2001;50(1):67–76. [Google Scholar]

- Stanley SM, Whitton SW, Kline GH, Markman HJ. Helping couples go beyond “good enough” in marriage. M. Whisman (Chair), Interpersonal flourishing: The positive side of close relationship functioning; Paper presented at the meeting of the Association for Behavioral and Cognitive Therapies; Chicago, IL. 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Stanley SM, Whitton SW, Low SM, Clements ML, Markman HJ. Sacrifice as a predictor of marital outcomes. Family Process. 2006;45:289–303. doi: 10.1111/j.1545-5300.2006.00171.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stanley SM, Whitton SW, Markman HJ. Maybe I do: Interpersonal commitment and premarital or nonmarital cohabitation. Journal of Family Issues. 2004;25:496–519. [Google Scholar]

- Whitton SW, Rhoades GK, Stanley SM, Markman HJ. Effects of parental divorce on marital commitment and confidence. Journal of Family Psychology. 2008;22(5):789–793. doi: 10.1037/a0012800. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wood RC, McConnell S, Moore Q, Clarkwest A, Hsueh J. Strengthening unmarried parents' relationships: The early impacts of Building Strong Families. Administration for Children and Families, Office of Planning, Research, and Evaluation; Washington D. C: 2010. The Building Strong Families Project. [Google Scholar]