We present a case of delayed takotsubo cardiomyopathy caused by accidental overadministration of exogenous epinephrine. This case highlights some of the prototypical features of takotsubo cardiomyopathy in an unusual clinical scenario.

CASE REPORT

A 44-year-old African American woman with previous hypertension, depression, and hyperlipidemia presented to an outside hospital with a 6-hour history of lower lip edema. Her medications included lisinopril 10 mg daily, which she had been taking for 1 year, and escitalopram 20 mg daily. She had no known drug allergies or previous operations. She had a 10 pack-year history of tobacco, but had quit 1 week prior to admission. Her family history was significant for coronary artery disease, hypertension, and diabetes mellitus.

Her initial blood pressure was 124/98 mm Hg, her pulse was 105 beats a minute and regular (Figure 1a), and her respiratory rate was 20 breaths a minute. She had edema of the lower lip, face, and oropharynx. Her lungs were clear to auscultation. She had normal heart sounds and no precordial murmur. He white blood count was 13,900/mm3; hemoglobin, 12,700 g/dL; and troponin, 0.83 mg/mL.

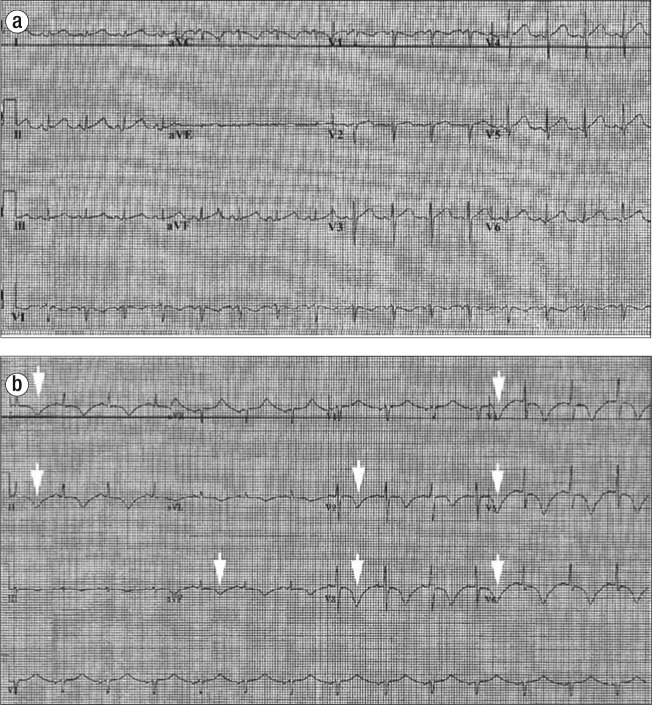

Figure 1.

Twelve-lead electrocardiogram shown at (a) baseline and (b) after reaction to exogenous epinephrine. Deep T-wave inversions are seen (arrows), concerning for ischemia.

In the emergency department, the patient was given methylprednisolone sodium succinate 125 mg ×2 intravenously, dexamethasone 4 mg intravenously every 6 hours, and diphenhydramine. She was initially given epinephrine 0.3 mg subcutaneously. The patient's lip edema did not abate, and the oropharyngeal edema worsened. A second dose of epinephrine was ordered, but the patient was incorrectly given 3 mg subcutaneously. Over the next 10 minutes, she became hypotensive and more tachycardic and developed pulmonary edema. She was transferred to the intensive care unit and started on norepinephrine bitartrate. During the next 24 hours, her blood pressure rose and she was weaned from norepinephrine. She was continued on dexa-methasone 4 mg every 12 hours and diphenhydramine 25 mg intravenously every 6 hours. A transthoracic echocardiogram showed a left ventricular ejection fraction of 67% with no wall motion abnormalities.

On day 3, the patient's dyspnea increased, and midsubsternal chest pain appeared. An electrocardiogram now showed deep T-wave inversions in the precordial leads (Figure 1b). Her troponin level was now 3.97 ng/mL. She was transferred to Baylor University Medical Center at Dallas.

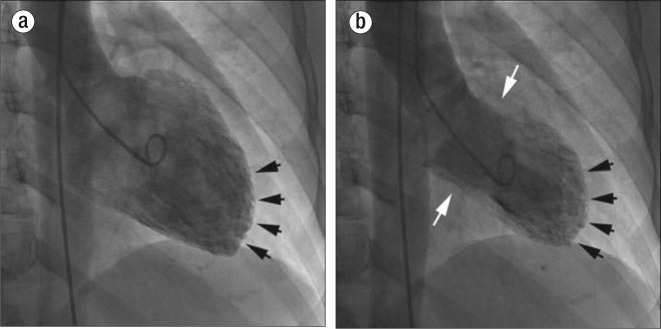

Cardiac catheterization showed “apical ballooning” without evidence of epicardial narrowing, a picture consistent with tako-tsubo cardiomyopathy (Figure 2). Her blood pressure remained stable, and she was ultimately discharged home on carvedilol 6.25 mg twice a day. A year later, the patient's dyspnea is gone, her cardiomyopathy has resolved, and she has had no recurrence of chest pain.

Figure 2.

Left ventriculogram in (a) diastole and (b) systole from the patient with exogenous epinephrine–induced takotsubo cardiomyopathy. The apical segments show essentially no movement (black arrows) relative to the basal segments (white arrows), reproducing the classic “ballooning” that looks like a Japanese “takotsubo,” or octopus trap.

DISCUSSION

Takotsubo cardiomyopathy (“broken heart syndrome”) is a clinical entity that mimics acute myocardial infarction in the setting of normal or near normal epicardial coronary arteries (1). Its exact mechanism is unknown, but these events appear to be temporally related to stressful situations where there are high levels of adrenergic stimulation (2). It is known that endogenous adrenergic stimulation (e.g., pheochromocytoma) can result in manifestations of this entity (3). A previous case occurring after administration of epinephrine has been reported (4).

Myocardial biopsies of takotsubo patients demonstrate contraction-band necrosis, a unique form of myocyte injury characterized by hypercontracted sarcomeres, dense eosinophilic transverse bands, and an interstitial mononuclear inflammatory response that is distinct from polymorphonuclear inflammation seen in the usual myocardial infarct (5). Follow-up studies of these patients show resolution of the contraction-band necrosis, which correlates with the resolution of symptoms in the patient (6).

The treatment of patients with takotsubo cardiomyopathy includes beta-blockers and angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors, and in most cases there is complete resolution of cardiac dysfunction (7). During the period of time when the cardiomyopathy is most severe, heart failure and arrhythmias can occur. Severe complications such as myocardial rupture and death have also been reported (8–10).

The exact time course between exposure to the stressful event, catecholamine surge, or exposure to exogenous catecholamines and the resultant end-organ damage is not well described. In our case, there was a lag time of at least 48 hours between exposure to the epinephrine and the resultant cardiomyopathy. No documented cases have demonstrated such a delayed time course. It is important to recognize the signs and symptoms of this entity, as the treatment is different from that of an acute ischemic event or myocarditis. In general, if the patient has no complications related to the acute cardiomyopathy, typically the cardiac dysfunction rapidly resolves with no further sequelae.

References

- 1.Tsuchihashi K, Ueshima K, Uchida T, Oh-mura N, Kimura K, Owa M, Yoshiyama M, Miyazaki S, Haze K, Ogawa H, Honda T, Hase M, Kai R, Morii I. Transient left ventricular apical ballooning without coronary artery stenosis: a novel heart syndrome mimicking acute myocardial infarction. Angina Pectoris-Myocardial Infarction Investigations in Japan. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2001;38(1):11–18. doi: 10.1016/s0735-1097(01)01316-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Wittstein IS, Thiemann DR, Lima JA, Baughman KL, Schulman SP, Gerstenblith G, Wu KC, Rade JJ, Bivalacqua TJ, Champion HC. Neurohumoral features of myocardial stunning due to sudden emotional stress. N Engl J Med. 2005;352(6):539–548. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa043046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Takizawa M, Kobayakawa N, Uozumi H, Yonemura S, Kodama T, Fukusima K, Takeuchi H, Kaneko Y, Kaneko T, Fujita K, Honma Y, Aoyagi T. A case of transient left ventricular ballooning with pheochromocytoma, supporting pathogenetic role of catecholamines in stress-induced cardiomyopathy or takotsubo cardiomyopathy. Int J Cardiol. 2007;114(1):e15–17. doi: 10.1016/j.ijcard.2006.07.125. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Winogradow J, Geppert G, Reinhard W, Resch M, Radke PW, Hengstenberg C. Tako-tsubo cardiomyopathy after administration of intravenous epinephrine during an anaphylactic reaction. Int J Cardiol. 2011;147(2):309–311. doi: 10.1016/j.ijcard.2010.12.063. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Fineschi V, Silver MD, Karch SB, Parolini M, Turillazzi E, Pomara C, Baroldi G. Myocardial disarray: an architectural disorganization linked with adrenergic stress? Int J Cardiol. 2005;99(2):277–282. doi: 10.1016/j.ijcard.2004.01.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Nef HM, Mollmann H, Kostin S, Troidl C, Voss S, Weber M, Dill T, Rolf A, Brandt R, Hamm CW, Elsasser A. Tako-tsubo cardiomyopathy: intraindividual structural analysis in the acute phase and after functional recovery. Eur Heart J. 2007;28(20):2456–2464. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehl570. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bybee KA, Kara T, Prasad A, Lerman A, Barsness GW, Wright RS, Rihal CS. Systematic review: transient left ventricular apical ballooning: a syndrome that mimics ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction. Ann Intern Med. 2004;141(11):858–865. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-141-11-200412070-00010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Barrera-Ramirez CF, Jimenez-Mazuecos JM, Alfonso F. Apical thrombus associated with left ventricular apical ballooning. Heart. 2003;89(8):927. doi: 10.1136/heart.89.8.927. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Matsuoka K, Okubo S, Fujii E, Uchida F, Kasai A, Aoki T, Makino K, Omichi C, Fujimoto N, Ohta S, Sawai T, Nakano T. Evaluation of the arrhythmogenecity of stress-induced “takotsubo cardiomyopathy” from the time course of the 12-lead surface electrocardiogram. Am J Cardiol. 2003;92(2):230–233. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9149(03)00547-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Villareal RP, Achari A, Wilansky S, Wilson JM. Anteroapical stunning and left ventricular outflow tract obstruction. Mayo Clin Proc. 2001;76(1):79–83. doi: 10.4065/76.1.79. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]