Abstract

To determine effects of pandemic (H1N1) 2009 on children in the tropics, we examined characteristics of children hospitalized for this disease in Malaysia. Of 1,362 children, 51 (3.7%) died, 46 of whom were in an intensive care unit. Although disease was usually mild, >1 concurrent conditions were associated with higher death rates.

Keywords: Children, Malaysia, tropical, hospitalized, co-morbidities, death, influenza, viruses, pandemic (H1N1) 2009, dispatch

Transmission of pandemic (H1N1) 2009 in the Northern and Southern Hemispheres has been well documented (1–12). These reports described a relatively mild and self-limited clinical illness for most cases. However, data on disease prevalence and severity in children in the tropics are scarce. Malaysia has 132 public and 214 private hospitals. We examined the demographics, clinical presentation, and outcomes of children hospitalized for pandemic (H1N1) 2009 in 68 Ministry of Health–affiliated public hospitals in Malaysia that offered pediatric services. These 68 hospitals provide 3,757 beds for children and 101 beds in pediatric intensive care units; each year they serve ≈7,898,700 children <12 years of age. During the pandemic (H1N1) 2009 containment phase, May–July 2009, the Ministry of Health mandated that all patients with influenza-like illness (ILI) be admitted to government (public) hospitals for observation and management. During the mitigation phase from August 2009 on, only patients with moderate to severe cases of ILI were hospitalized (13). Influenza vaccine is used in the private sector only, and during the study period, only health care workers were vaccinated against pandemic (H1N1) 2009.

The Study

We enrolled children <12 years of age who were hospitalized for ILI from June 18, 2009, through March 1, 2010, and for whom pandemic (H1N1) 2009 infection was confirmed by real-time reverse transcription–PCR. This study was reviewed and approved by the Malaysian Research and Ethics Committee. Informed consent was provided for patients with confirmed diagnoses.

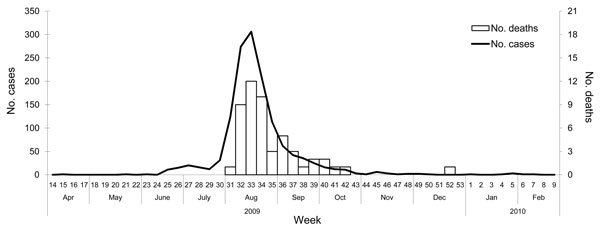

During the study period, 1,362 children were hospitalized for ILI. The first case was diagnosed and confirmed as pandemic (H1N1) 2009 during the third week of June 2009; the number of cases peaked at week 33 and declined until week 43 of 2009 and weeks 1–9 of 2010 (Figure). The rapid decline of cases after week 33 may have resulted from a change in hospitalization criteria recommendations. From June 18 through July 2009, hospitalization rates among children <12 years, <5 years, and <2 years of age were 1.4, 1.0, and 1.1 per 100,000 children in each age group, respectively. From August 2009 through February 2010, corresponding hospitalization rates were 15.9, 23.8, and 33 per 100,000 children, respectively.

Figure.

Distribution of laboratory-confirmed cases of pandemic (H1N1) 2009 and deaths in 1,362 hospitalized children, Malaysia, June 18, 2009–March 1, 2010.

Overall median age of the hospitalized children was 3 years (interquartile range [IQR] 1–6 years); 861 (63.2%) were <5 years and 536 (39.4%) were <2 years of age. Among those who died, median age at time of death was 2 years (IQR 0–6 years). Other demographic characteristics of the cohort are shown in Table 1.

Table 1. Characteristics of 1,362 hospitalized children with pandemic (H1N1) 2009, Malaysia, June 18, 2009–March 1, 2010.

| Characteristic | No. (%) children |

|---|---|

| Demographic | |

| Male sex | 762 (55.9) |

| Age group | |

| 0–6 mo | 152 (11.2) |

| 7–12 mo | 182 (13.4) |

| 13–23 mo | 202 (14.8) |

| 2–4 y | 325 (23.9) |

| 5–8 y | 298 (21.9) |

| 9–12 y | 203 (14.8) |

| Ethnic group | |

| Malay | 995 (73.1) |

| Chinese | 109 (8.0) |

| Indian | 83 (6.1) |

| Native East Malaysian* | 99 (7.3) |

| Indigenous native | 24 (1.8) |

| Other |

52 (3.8) |

| Clinical sign or symptom | |

| Fever | 1313 (96.4) |

| Cough | 1237 (90.8) |

| Runny nose | 794 (58.3) |

| Nausea | 346 (25.4) |

| Poor feeding | 310 (22.8) |

| Labored breathing | 293 (21.5) |

| Diarrhea | 177 (13.0) |

| Sore throat | 164 (12.0) |

| Seizure | 117 (8.6) |

| Fatigue | 94 (6.9) |

| Headache | 30 (2.2) |

| Abdominal pain | 30 (2.2) |

| Altered consciousness | 13 (1.0) |

| Vomiting |

6 (0.4) |

| Disease severity/treatment needed | |

| Admission to intensive care unit | 134 (9.8) |

| Mechanical ventilation | 101 (7.4) |

| Supplemental oxygen† | 317 (23.3) |

| Noninvasive ventilation‡ |

4 (0.3) |

| Complication | |

| Shock | 57 (4.2) |

| Acute respiratory distress syndrome | 41 (3.0) |

| Encephalitis/encephalopathy§ | 21 (1.5) |

| Myocarditis | 8 (0.6) |

| Disseminated intravascular coagulation | 7 (0.5) |

| Liver impairment | 32 (2.3) |

| Multiple organ failure | 12 (0.9) |

| Myoglobinuria | 1 (0.07) |

*Kadazan/Dusun, Melanau, Bajau, Bidayuh, Iban, Orang Ulu, Lundayeh, Kayan, Kedayan, Sabahan, Kadayan, Suluk, Tidung, Bisaya. †Oxygen delivered by nasal cannula, nasal prong, or face mask. ‡Mechanical ventilation that does not use an artificial airway such as endotracheal tube. §Inflammation of brain or degeneration of brain function.

A total of 602 (44.2%) children were admitted to hospital within 48 hours of onset of clinical signs. Median interval from onset of signs to hospitalization was 3 days (IQR 1–5 days) for the overall cohort, 3 days (IQR 1–5 days) for those who survived, and 4 days (IQR 2–6 days) for those who died. Among 120 (8.8%) children whose clinical condition worsened during hospitalization, deterioration occurred within the first 24 hours after admission for 67 (55.9%). Among 657 (48.2%) patients for whom blood cultures were performed, results were positive for only 29 (4.4%). The most common pathogen isolated was Streptococcus pneumoniae (n = 6), followed by coagulase-negative Staphylococcus spp. (n = 5), Burkholderia cepacia (n = 4), Klebsiella pneumoniae (n = 2), and Pseudomonas spp. (n = 2). Of 6 S. pneumoniae isolates, 5 were documented within 48 hours of admission, including 2 from children who died. Laboratory parameters at time of admission did not differ significantly between those who survived and those who died, except for hemoglobin (odds ratio [OR] 0.71, 95% confidence interval [CI] 0.59–0.87, p = 0.001), arterial bicarbonate (OR 0.81, 95% CI 0.72–0.91, p<0.001), and serum albumin (OR 0.90, 95% CI 0.87–0.94, p<0.001). Among 1,049 children for whom chest radiographs were taken at time of admission, infiltrates were noted for 643 (61.3%), consolidation for 254 (24.2%), and pleural effusion for 4 (0.4%). No radiographic abnormalities were detected for 173 (16.5%) children. Antiviral drugs had been given to 78 (5.7%) children before admission and to 1,306 (95.6%) children after admission. The most common antiviral drug used was oseltamivir, followed by zanamivir (received by 2 [0.2%] children). An antiviral drug was given within 48 hours of onset of signs for 388 (28.5%) children, including 382 (29.1%) who survived and 6 (11.7%) who died. An antiviral drug was given >48 hours after onset of signs for 783 (57.5%) children, including 748 (57.1%) who survived and 35 (68.6%) who died. Administration of an antiviral drug within 48 hours of onset of signs was associated with a lower risk for death (OR 0.4, 95% CI 0.2–0.9; p = 0.02). Median duration of oseltamivir administration was 5 days (IQR 4–7 days). Among 1,306 children for whom data were available, 982 (75.2%) also received antibacterial drugs.

Among the same 1,306 children for whom data were available, 461 (35.3%) had a concurrent illness (Table 2); 416 (31.9%) had 1 concurrent illness and 65 (4.9%) had 2. Presence of >1 concurrent conditions was associated with a 4-fold increased risk for death (OR 4.4, 95% CI 2.4–8.1; p<0.001). Risk for death was higher for those with chronic lung disease (OR 2.5, 95% CI 1.1–5.6; p<0.02) than for those with other concurrent conditions. Among the 64 (4.7%) children who required inotropic support, 23 (34.3%) survived. Among all 1,362 hospitalized children, 51 (3.7%) died, including 46 (90.2%) in intensive care units and 25 (49%) who were <2 years of age (OR 1.51, 95% CI 0.86–2.64), p = 0.15). Among the 101 children who required mechanical ventilation, 49 (48.5%) died. Among the 1,352 children for whom follow-up data were available, 1,285 (95%) recovered fully and had no sequelae at time of hospital discharge, and 12 (0.9%) recovered but had sequalae (5 pulmonary, 4 neurologic, 2 renal, and 1 pulmonary and neurologic). The mortality rate for children who were <12, <5, and <2 years of age during June–July 2009 was 0.1 death per 100,000 children. Corresponding rates for August 2009–February 2010 were 0.6, 0.9, and 1.3 per 100,000 children, respectively.

Table 2. Concurrent conditions in children hospitalized for pandemic (H1N1) 2009, Malaysia, June 18, 2009–March 1, 2010*.

| Condition | No. (%) children |

OR (95% CI) | p value | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total | Survived | Died | |||

| None | 860(63.1) | 845 (64.7) | 15 (29.4) | 0.2 (0.1–0.4) | <0.001 |

| Chronic lung disease | 258 (18.9) | 246 (18.8) | 12 (23.5) | 2.5 (1.1–5.6) | 0.02 |

| Neuromuscular disease | 33 (2.4) | 27 (2.1) | 6 (11.8) | 2.5 (4.5–34.8) | <0.001 |

| Cardiovascular disease | 54 (4.0) | 46 (3.5) | 8 (15.7) | 9.8 (3.9–24.3) | <0.001 |

| Renal disease | 18 (1.3) | 16 (1.2) | 2 (3.5) | – | – |

| Immunosuppression | 18 (1.3) | 15 (1.1) | 3 (5.9) | – | – |

| Obesity | 14(1.0) | 13 (1.0) | 1 (2.0) | – | – |

| Malnutrition | 14 (1.0) | 13 (1.0) | 1 (2.0) | – | – |

*OR, odds ratio; CI, confidence interval; –, numbers too small to infer from study sample.

Conclusions

In the tropics, pandemic (H1N1) 2009 is a relatively mild illness in children who have no concurrent condition. Serious complications such as shock and acute respiratory distress syndrome were relatively rare. However, among the small proportion for whom disease was severe, progression was rapid and death occurred within a short period. The case-fatality rate for the hospitalized cohort reported here was 3.7%, comparable to the rates of 0.1%–5.1% documented by others (4,9,14). Hospitalization and mortality rates were proportionally higher for children <2 years of age than for children in other age groups. Severe disease leading to death was more likely for patients who had >1 concurrent condition. Other studies have demonstrated similar findings (3,4,7,11).

Data on concurrent conditions can help identify and prioritize patients who need prompt antiviral drug therapy and vaccination in countries with limited resources. Our finding that early administration of an antiviral drug was associated with a lower risk for death concurs with findings of other studies (3). Study limitations include the facts that patients with mild cases may not seek (or be brought for) medical attention and that not all cases of ILI were laboratory confirmed as pandemic (H1N1) 2009. Early initiation of antiviral therapy, especially for children with concurrent conditions, may improve outcomes.

Acknowledgment

We thank the Director General of Health, Ministry of Health Malaysia, for permission to publish this study and members of the Malaysian Paediatric 2009 Pandemic Influenza A (H1N1) Study Team for their invaluable cooperation and partnership.

This study was funded by a grant (NMRR-09-589-4324) from the Ministry of Health Malaysia.

Biography

Dr Ismail is head of the Paediatric Institute, Hospital Kuala Lumpur, Ministry of Health Malaysia. His research interest is infections of the central nervous system.

Footnotes

Suggested citation for this article: Ismail HIM, Tan KK, Lee YL, Pau WSC, Razali KAM, Mohamed T, et al. Characteristics of children hospitalized for pandemic (H1N1) 2009, Malaysia. Emerg Infect Dis [serial on the Internet]. 2011 Apr [date cited]. http://dx.doi.org/10.3201/eid1704101212

References

- 1.Novel Swine-Origin Influenza A (H1N1) Virus Investigation Team, Dawood FS, Jain S, Finelli L, Shaw MW, Lindstrom S, Garten RJ, et al. Emergence of a novel swine-origin influenza A (H1N1) virus in humans. N Engl J Med. 2009;360:2605–15. 10.1056/NEJMoa0903810 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Chowell G, Bertozzi SM, Colchero MA, Lopez-Gatell H, Alpuche-Aranda C, Hernandez M, et al. Severe respiratory disease concurrent with the circulation of H1N1 influenza. N Engl J Med. 2009;361:674–9. 10.1056/NEJMoa0904023 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Jain S, Kamimoto L, Bramley AM, Schmitz AM, Benoit SR, Louie J, et al. Hospitalized patients with 2009 H1N1 influenza in the United States, April–June 2009. N Engl J Med. 2009;361:1935–44. 10.1056/NEJMoa0906695 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Libster R, Bugna J, Coviello S, Hijano DR, Dunaiewsky M, Reynoso N, et al. Pediatric hospitalizations associated with 2009 pandemic influenza A (H1N1) in Argentina. N Engl J Med. 2010;362:45–55. 10.1056/NEJMoa0907673 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Cao B, Li XW, Mao Y, Wang J, Lu HZ, Chen YS, et al. Clinical features of the initial cases of 2009 pandemic influenza A (H1N1) virus infection in China. N Engl J Med. 2009;361:2507–17. 10.1056/NEJMoa0906612 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Perez-Padilla R, de la Rosa-Zamboni D, Ponce de Leon S, Hernandez M, Quinones-Falconi F, Bautista E, et al. Pneumonia and respiratory failure from swine-origin influenza A (H1N1) in Mexico. N Engl J Med. 2009;361:680–9. 10.1056/NEJMoa0904252 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Jouvet P, Hutchison J, Pinto R, Menon K, Rodin R, Choong K, et al. Critical illness in children with influenza A/pH1N1 2009 infection in Canada. Pediatr Crit Care Med. 2010. Mar 19. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 8.Louie JK, Acosta M, Winter K, Jean C, Gavali S, Schechter R, et al. Factors associated with death or hospitalization due to pandemic 2009 influenza A(H1N1) infection in California. JAMA. 2009;302:1896–902. 10.1001/jama.2009.1583 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Donaldson LJ, Rutter PD, Ellis BM, Greaves FE, Mytton OT, Pebody RG, et al. Mortality from pandemic A/H1N1 2009 influenza in England: public health surveillance study. BMJ. 2009;339:b5213. 10.1136/bmj.b5213 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Domínguez-Cherit G, Lapinsky SE, Macias AE, Pinto R, Espinosa-Perez L, de la Torre A, et al. Critically ill patients with 2009 influenza A(H1N1) in Mexico. JAMA. 2009;302:1880–7. 10.1001/jama.2009.1536 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kumar A, Zarychanski R, Pinto R, Cook DJ, Marshall J, Lacroix J, et al. Critically ill patients with 2009 influenza A(H1N1) infection in Canada. JAMA. 2009;302:1872–9. 10.1001/jama.2009.1496 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.O'Riordan S, Barton M, Yau Y, Read SE, Allen U, Tran D. Risk factors and outcomes among children admitted to hospital with pandemic H1N1 influenza. CMAJ. 2010;182:39–44. 10.1503/cmaj.091724 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ministry of Health Malaysia. Management guidelines for influenza A-H1N1 for pediatric patients. 2009. Aug 26 [cited 2010 Dec 1]. http://h1n1.moh.gov.my/PediatricPatients.php

- 14.Reyes L, Arvelo W, Estevez A, Gray J, Moir JC, Gordillo B, et al. Population-based surveillance for 2009 pandemic influenza A(H1N1) virus in Guatemala, 2009. Influenza Other Respir Viruses. 2010;4:129–40. 10.1111/j.1750-2659.2010.00138.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]