Abstract

The emergence of pandemic (H1N1) 2009 virus highlighted the need for enhanced surveillance of swine influenza viruses. We used real-time reverse–transcription PCR–based genotyping and found that this rapid and simple genotyping method may identify reassortants derived from viruses of Eurasian avian-like, triple reassortant-like, and pandemic (H1N1) 2009 virus lineages.

Keywords: Swine influenza, reassortment, genotyping, influenza, viruses, dispatch

Co-infection of influenza A viruses enables viral gene reassortments, thereby generating progeny viruses with novel genotypes. Such reassortants may pose a serious public health threat, as exemplified by the emergence of pandemic influenza (H1N1) in 2009 (1). Transmission of pandemic (H1N1) 2009 virus from humans to pigs has been reported (2–5). We recently identified a reassortment between pandemic (H1N1) 2009 virus and swine influenza viruses in pigs (6). These results emphasize the potential role of pigs as a mixing vessel for influenza viruses and the need for screening tests that can identify major reassortment events in pigs.

We previously developed 8 monoplex SYBR green–based quantitative reverse transcription–PCRs to detect all 8 gene segments derived from the pandemic (H1N1) 2009 virus or virus segments that are closely related to this lineage (i.e., neuraminidase [NA] and matrix protein from the Eurasian avian-like swine linage and polymerase basic protein [PB] 2, PB1, polymerase acidic protein [PA], hemagglutinin [HA], nucleocapsid protein [NP], and nonstructural protein [NS]) from triple reassortant swine linage (5). Using these PCRs, we identified swine viruses of atypical genotypes. However, with the exception of the HA-specific assay, the melting-curve signals of pandemic (H1N1) 2009 virus may be indistinguishable from the positive signals generated from its sister clade as indicated above. To differentiate between these closely related groups of viruses, we further optimized these assays by adding sequence-specific hydrolysis probes in the SYBR green assays.

The Study

For this study, all SYBR green assays were modified from the previously described assays (5), with the exception of the reverse primers for the newly designed PB1 and NS segments (Table 1). The subtype H1N1 swine influenza viruses isolated in Hong Kong during the past few years were mainly derived from the Eurasian avian-like swine lineage (6,7). To generate more precise genotyping data for our ongoing surveillance, the NA segment–specific assay was specifically designed to react with the pandemic (H1N1) 2009 virus and a portion of Eurasian avian-like swine viruses that are circulating in southeastern China ( Technical Appendix Figure 1). To avoid overlapping the emission spectrum of SYBR green, we labeled all pandemic (H1N1) 2009 virus–specific hydrolysis probes (Integrated DNA Technologies, Inc., Coralville, IA, USA) with cyanine 5 (Cy5) and Black Hole Quencher-2 dyes at their 5′ and 3′ ends, respectively (Table 1). To enable use of short oligonucleotide sequences without compromising the annealing temperature of these probes, we modified the probes with locked nucleic acids (7). RNA extraction and complimentary DNA synthesis were identical to the protocols described (5,8). One microliter of 10-fold diluted complimentary DNA sample was amplified in a 20-µL reaction containing 10 µL of Fast SYBR Green Master Mix (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA, USA) and the corresponding primer probe set (0.5 µmol/L each). All reactions were optimized and performed simultaneously in a 7500 Sequence Detection System (Applied Biosystems) with the following conditions: 20 s at 95°C, followed by 30 cycles of 95°C for 3 s and 62°C for 30 s. SYBR green and Cy5 signals from the same reaction were captured simultaneously at the end of each amplification cycle. The expected PCR results of virus segment derived from different swine viral lineages are shown in Table 2.

Table 1. Primer–probe sets selective for pandemic (H1N1) 2009 virus gene segments*.

| Segment | Primer and probe† | Sequence, 5′ → 3′‡ |

|---|---|---|

| PB2 | PB2-1877F§ | AACTTCTCCCCTTTGCTGCT |

| PB2-2062R§ | GATCTTCAGTCAATGCACCTG | |

|

|

PB2-2028RP |

Cy5-AACTGTAAGTCGTTTGGT-BHQ2 |

| PB1 | PB1-825F§ | ACAGTCTGGGCTCCCAGTA |

| PB1-1023R | GAACCACTCGGGTTGATTTCTG | |

|

|

PB1-863FP |

Cy5-CCAAACTGGCAAATG-BHQ2 |

| PA | PA-821F§ | GCCCCCTCAGATTGCCTG |

| PA-1239R§ | GCTTGCTAGAGATCTGGGC | |

|

|

PA-844FP |

Cy5-CCTCTTTGCCATCAGC-BHQ2 |

| HA | HA-398F§ | GAGCTCAGTGTCATCATTTGAA |

| HA-570R§ | TGCTGAGCTTTGGGTATGAA | |

|

|

HA-470FP |

Cy5-CAAAGGTGTAACGGCA-BHQ2 |

| NP | NP-593F§ | TGAAAGGAGTTGGAACAATAGCAA |

| NP-942R§ | GACCAGTGAGTACCCTTCCC | |

|

|

NP-872RP |

Cy5-AGGCAGGATTTATGTG-BHQ2 |

| NA | NA-163F§ | CATGCAATCAAAGCGTCATT |

| NA-268R§ | ACGGAAACCACTGACTGTCC | |

|

|

NA-248RP |

Cy5-AGCAGCAAAGTTGGTG-BHQ2 |

| M | M-504F§ | GGTCTCACAGACAGATGGCT |

| M-818R§ | GATCCCAATGATATTTGCTGCAATG | |

|

|

M-530FP |

Cy5-ACCAATCCACTAATCAGG-BHQ2 |

| NS | NS-252F§ | ACACTTAGAATGACAATTGCATCTGT |

| NS-345R | GCATGAGCATGAACCAGTCTCG | |

| NS-288FP | Cy5-CGCTACCTTTCTGACAT/BHQ2/ |

*PB, polymerase basic protein; PA, polymerase acidic protein; HA, hemagglutinin; NP, nucleocapsid protein; NA, neuraminidase; M, matrix protein; NS, nonstructural protein; Cy5, cyanine 5; BHQ2, Black Hole Quencher 2. †Number represents nucleotide position of the first base in the target sequence (cRNA sense). ‡Locked nucleic acid–modified bases are underlined. §Primers adapted from the assays as previously described (5,6).

Table 2. Summary of expected genotyping results of swine and human influenza viruses*.

| Virus | PB2 | PB1 | PA | HA | NP | NA† | M | NS |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pandemic (H1N1) 2009 | + + | + + | + + | + + | + + | + + | + + | + + |

| Swine Eurasian avian-like | – – | – – | – – | – – | – – | – + | – + | – – |

| Swine triple reassortant | – + | – + | – + | – + | – + | – – | – – | – + |

| Human seasonal subtypes H1 and H3 | – – | – – | – – | – – | – – | – – | – – | – – |

*PB, polymerase basic protein; PA, polymerase acidic protein; HA, hemagglutinin; NP, nucleocapsid protein; NA, neuraminidase; M, matrix protein; NS, nonstructural protein. Red symbols indicate pandemic (H1N1) 2009 virus–specific probe results; black symbols indicate SYBR Green results; gray shading indicates sister clade of pandemic (H1N1) 2009 virus for each virus segment. †N2 and some of the N1 within swine Euarasian avian-like lineage are expected to be double negative in the NA test.

The dissociation kinetics of PCR amplicons were studied by a melting curve analysis at the end of the PCR (60°C–95°C; temperature increment 0.1°C/s). We also tested various probe and SYBR green concentrations under different PCR conditions. The condition described above gave the most robust and consistent DNA amplification (data not shown). We tested 31 human pandemic (H1N1) 2009 and 63 human seasonal influenza viruses (33 subtype H1N1, 30 subtype H3N2) as controls. As expected, all human pandemic influenza viruses were double positive (i.e., positive with SYBR green and Cy5) and all seasonal influenza samples were double negative in all 8 assays.

To evaluate the sensitivity of the assays, we tested serial diluted plasmid DNA of the corresponding segments of influenza A/California/4/2009 virus as a standard. The fluorescent signals generated from the SYBR green reporter dye in all assays were highly similar to those previously reported (5), and the modified assays had a linear dynamic detection range from 102 to 108 copies/reaction (Technical Appendix Figure 2). As expected, the threshold cycle values deduced from the Cy5 reporter signal were generally higher than those from the SYBR green reporter (Technical Appendix Figure 2) (9). This finding can be partly explained by the nature of these 2 kinds of real-time PCR chemistries: a single Cy5 fluorophore of the hydrolysis probe was released from quenching for each amplicon synthesized while multiple SYBR green dyes bound to a single amplicon (10). After 35 PCR amplification cycles, the linear dynamic detection range of Cy5 signals generated from these reactions was 102 to 108 copies/reaction (data not shown). However, to avoid nonspecific SYBR green signals, we purposely limited the number of amplification cycles to 30.

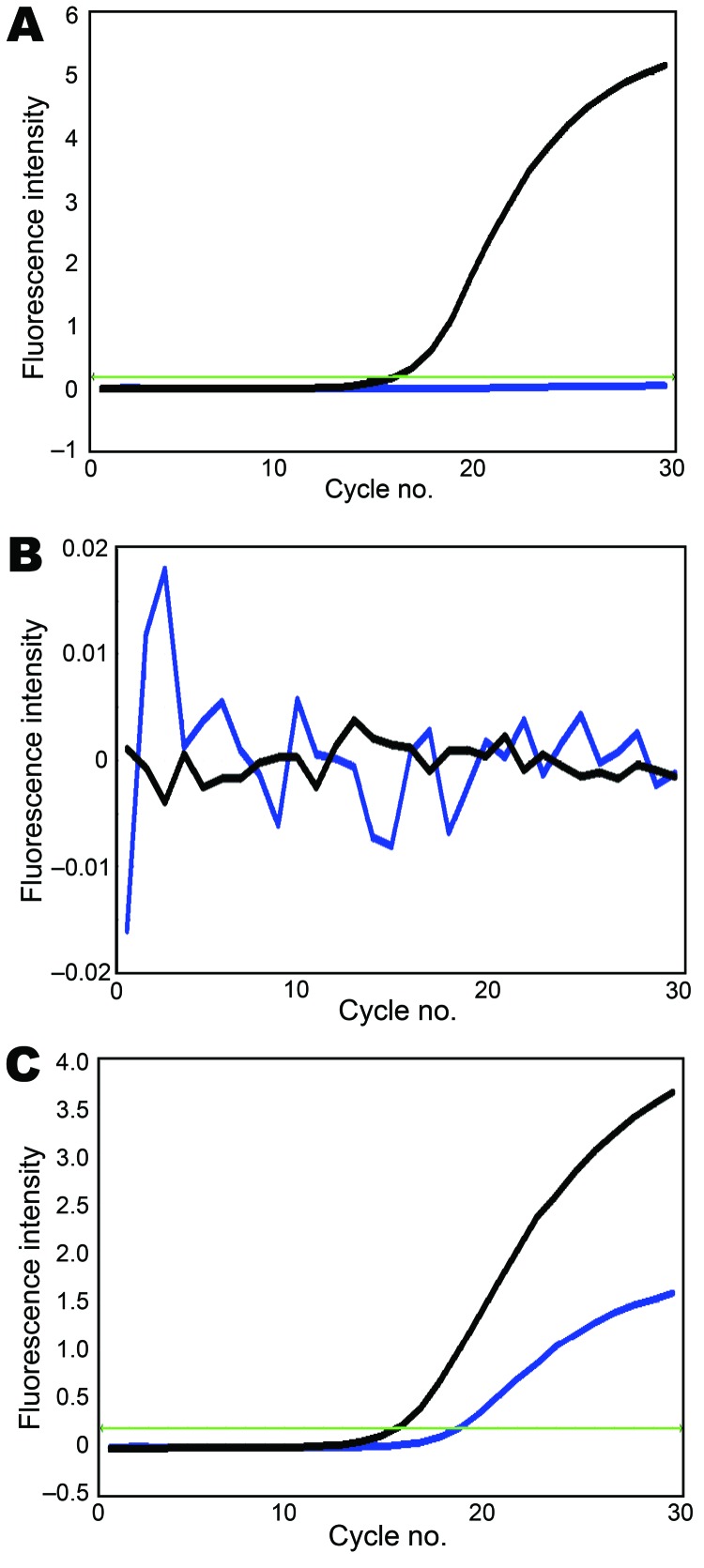

Using these assays, we tested 41 swine virus isolates collected during January 2009–January 2010. In all 8 reactions, 10 pandemic (H1N1) 2009 virus samples transmitted from humans to pigs (6) were double positive (Technical Appendix Figure 1, pink). In these assays, gene segments of another 31 swine isolates were either SYBR green positive/Cy5 negative (Technical Appendix Figure 1, yellow) or double negative (Technical Appendix Figure 1, green), indicating that these virus segments were derived from the sister clade of pandemic (H1N1) 2009 virus or other swine lineages (except NA), respectively. For example, the reassortant of pandemic (H1N1) 2009 virus (A/swine/Hong Kong/201/2010 [H1N1]) was double positive for NA, double negative for HA and matrix protein, and SYBR green positive/Cy5 negative for PB2, PB1, PA, NP, and NS (Figure; other data not shown). All genotyping results of the studied viruses were consistent with results of previous phylogenetic analyses (5,6), indicating that our modified probes and SYBR green assays can provide more accurate genotyping results. With these genotyping data, viruses with atypical positive signal patterns might suggest a novel viral reassortment event and can be highlighted for investigation with sequencing-based methods.

Figure.

Genotyping of A) polymerase acidic protein, B) hemagglutinin, and C) neuraminidase segments of A/swine/Hong Kong/201/2010 influenza (H1N1) virus. Black line, amplification signal of SYBR green dye; blue line, amplification signal of cyanine 5 dye; green line, threshold level. The x-axis denotes the cycle number of a quantitative PCR assay, and the y-axis denotes the fluorescence intensity over the background.

To demonstrate the potential use of these assays in studying swine viruses circulating in other geographic locations, we tested 7 recent swine isolates (1 pandemic influenza subtype H1N1, 4 subtype H1N2, and 2 subtype H3N2) collected in the United States. Genotyping results agreed 100% with data deduced from sequence analyses (Technical Appendix Table 1). We also analyzed all 436 contemporary (2008–2010) US swine virus segments available from the National Center for Biotechnology Information influenza virus sequence database. On the basis of the in silico analysis of sequences targeted by our primers and probes, 95% of the sequences (n = 413) are predicted to yield the expected results (Technical Appendix Table 2).

Conclusions

The emergence of pandemic (H1N1) 2009 has highlighted the need for global systematic influenza surveillance in swine. Our results demonstrated that the addition of locked nucleic acid hydrolysis probes specific for pandemic (H1N1) 2009 virus into previously established SYBR green assays can help differentiate segments of pandemic (H1N1) 2009, Eurasian avian-like, and triple reassortant virus lineages. These assays might provide a rapid and simple genotyping method for identifying viruses that need to be fully genetically sequenced and characterized. They may also help provide better understanding of the viral reassortment events and viral dynamics in pigs. Although at present, genes derived from human seasonal viruses cannot be characterized with our modified assays, the performance of our assays warrants similar investigations for genotyping human influenza viruses.

Supplementary Material

Genotyping results , viral sequences, and Combined SYBR green/hydrolysis probe quantitative RT-PCR assays for swine influenza virus

Acknowledgments

This study was supported by the Area of Excellence Scheme of the University Grants Committee Hong Kong (grant AoE/M-12/06), the Research Grant Council of Hong Kong (HKU 773408M to L.L.M.P.), the Seed Funding for Basic Research (Hong Kong University), Research Fund for the Control of Infectious Disease Commissioned Project Food and Health Bureau (Hong Kong), and the National Institutes of Health (National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases contract HHSN266200700005C).

Biography

Ms Mak is a postgraduate student in the Department of Microbiology, The University of Hong Kong. Her research focuses on molecular diagnosis of influenza virus.

Footnotes

Suggested citation for this article: Mak PWY, Wong CKS, Li OTW, Chan KH, Cheung CL, Ma ES, et al. Rapid genotyping of swine influenza viruses. Emerg Infect Dis [serial on the Internet]. 2011 Apr [date cited]. http://dx.doi.org/10.3201/eid1704.101726

References

- 1.Novel Swine-Origin Influenza A (H1N1) Virus Investigation Team, Dawood FS, Jain S, Finelli L, Shaw MW, Lindstrom S, et al. Emergence of a novel swine-origin influenza A (H1N1) virus in humans. N Engl J Med. 2009;360:2605–15. 10.1056/NEJMoa0903810 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Pasma T, Joseph T. Pandemic (H1N1) 2009 infection in swine herds, Manitoba, Canada. Emerg Infect Dis. 2010;16:706–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Pereda A, Cappuccio J, Quiroga MA, Baumeister E, Insarralde L, Ibar M, et al. Pandemic (H1N1) 2009 outbreak on pig farm, Argentina. Emerg Infect Dis. 2010;16:304–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Howden KJ, Brockhoff EJ, Caya FD, McLeod LJ, Lavoie M, Ing JD, et al. An investigation into human pandemic influenza virus (H1N1) 2009 on an Alberta swine farm. Can Vet J. 2009;50:1153–61. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Poon LL, Mak PW, Li OT, Chan KH, Cheung CL, Ma ES, et al. Rapid detection of reassortment of pandemic (H1N1) 2009 influenza virus. Clin Chem. 2010;56:1340–4. 10.1373/clinchem.2010.149179 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Vijaykrishna D, Poon LL, Zhu HC, Ma SK, Li OT, Cheung CL, et al. Reassortment of pandemic (H1N1) 2009 influenza A virus in swine. Science. 2010;328:1529. 10.1126/science.1189132 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Johnson MP, Haupt LM, Griffiths LR. Locked nucleic acid (LNA) single nucleotide polymorphism (SNP) genotype analysis and validation using real-time PCR. Nucleic Acids Res. 2004;32:e55. 10.1093/nar/gnh046 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Poon LL, Chan KH, Smith GJ, Leung CS, Guan Y, Yuen KY, et al. Molecular detection of a novel human influenza (H1N1) of pandemic potential by conventional and real-time quantitative RT-PCR assays. Clin Chem. 2009;55:1555–8. 10.1373/clinchem.2009.130229 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Papin JF, Vahrson W, Dittmer DP. SYBR green–based real-time quantitative PCR assay for detection of West Nile virus circumvents false-negative results due to strain variability. J Clin Microbiol. 2004;42:1511–8. 10.1128/JCM.42.4.1511-1518.2004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Buh Gašparič M, Tengs T, La Paz JL, Holst-Jensen A, Pla M, Esteve T, et al. Comparison of nine different real-time PCR chemistries for qualitative and quantitative applications in GMO detection. Anal Bioanal Chem. 2010;396:2023–9. 10.1007/s00216-009-3418-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Genotyping results , viral sequences, and Combined SYBR green/hydrolysis probe quantitative RT-PCR assays for swine influenza virus