Executive Summary

In August 2008, the Medical Advisory Secretariat (MAS) presented a vignette to the Ontario Health Technology Advisory Committee (OHTAC) on a proposed targeted health care delivery model for chronic care. The proposed model was defined as multidisciplinary, ambulatory, community-based care that bridged the gap between primary and tertiary care, and was intended for individuals with a chronic disease who were at risk of a hospital admission or emergency department visit. The goals of this care model were thought to include: the prevention of emergency department visits, a reduction in hospital admissions and re-admissions, facilitation of earlier hospital discharge, a reduction or delay in long-term care admissions, and an improvement in mortality and other disease-specific patient outcomes.

OHTAC approved the development of an evidence-based assessment to determine the effectiveness of specialized community based care for the management of heart failure, Type 2 diabetes and chronic wounds.

Please visit the Medical Advisory Secretariat Web site at: www.health.gov.on.ca/ohtas to review the following reports associated with the Specialized Multidisciplinary Community-Based care series.

Specialized multidisciplinary community-based care series: a summary of evidence-based analyses

Community-based care for the specialized management of heart failure: an evidence-based analysis

Community-based care for chronic wound management: an evidence-based analysis

Please note that the evidence-based analysis of specialized community-based care for the management of diabetes titled: “Community-based care for the management of type 2 diabetes: an evidence-based analysis” has been published as part of the Diabetes Strategy Evidence Platform at this URL: http://www.health.gov.on.ca/english/providers/program/mas/tech/ohtas/tech_diabetes_20091020.html

Please visit the Toronto Health Economics and Technology Assessment Collaborative Web site at: http://theta.utoronto.ca/papers/MAS_CHF_Clinics_Report.pdf to review the following economic project associated with this series:

Community-based Care for the specialized management of heart failure: a cost-effectiveness and budget impact analysis.

Objective

The objective of this evidence-based analysis was to determine the effectiveness of specialized multidisciplinary care in the management of heart failure (HF).

Clinical Need: Target Population and Condition

HF is a progressive, chronic condition in which the heart becomes unable to sufficiently pump blood throughout the body. There are several risk factors for developing the condition including hypertension, diabetes, obesity, previous myocardial infarction, and valvular heart disease.(1) Based on data from a 2005 study of the Canadian Community Health Survey (CCHS), the prevalence of congestive heart failure in Canada is approximately 1% of the population over the age of 12.(2) This figure rises sharply after the age of 45, with prevalence reports ranging from 2.2% to 12%.(3) Extrapolating this to the Ontario population, an estimated 98,000 residents in Ontario are believed to have HF.

Disease management programs are multidisciplinary approaches to care for chronic disease that coordinate comprehensive care strategies along the disease continuum and across healthcare delivery systems.(4) Evidence for the effectiveness of disease management programs for HF has been provided by seven systematic reviews completed between 2004 and 2007 (Table 1) with consistency of effect demonstrated across four main outcomes measures: all cause mortality and hospitalization, and heart-failure specific mortality and hospitalization. (4-10)

However, while disease management programs are multidisciplinary by definition, the published evidence lacks consistency and clarity as to the exact nature of each program and usual care comparators are generally ill defined. Consequently, the effectiveness of multidisciplinary care for the management of persons with HF is still uncertain. Therefore, MAS has completed a systematic review of specialized, multidisciplinary, community-based care disease management programs compared to a well-defined usual care group for persons with HF.

Evidence-Based Analysis Methods

Research Questions

What is the effectiveness of specialized, multidisciplinary, community-based care (SMCCC) compared with usual care for persons with HF?

Literature Search Strategy

A comprehensive literature search was completed of electronic databases including MEDLINE, MEDLINE In-Process and Other Non-Indexed Citations, EMBASE, Cochrane Library and Cumulative Index to Nursing & Allied Health Literature. Bibliographic references of selected studies were also searched. After a review of the title and abstracts, relevant studies were obtained and the full reports evaluated. All studies meeting explicit inclusion and exclusion criteria were retained. Where appropriate, a meta-analysis was undertaken to determine the pooled estimate of effect of specialized multidisciplinary community-based care for explicit outcomes. The quality of the body of evidence, defined as one or more relevant studies was determined using GRADE Working Group criteria. (11)

Inclusion Criteria

Randomized controlled trial

Systematic review with meta analysis

Population includes persons with New York Heart Association (NYHA) classification 1-IV HF

The intervention includes a team consisting of a nurse and physician one of which is a specialist in HF management.

The control group receives care by a single practitioner (e.g. primary care physician (PCP) or cardiologist)

The intervention begins after discharge from the hospital

The study reports 1-year outcomes

Exclusion Criteria

The intervention is delivered predominately through home-visits

Studies with mixed populations where discrete data for HF is not reported

Outcomes of Interest

All cause mortality

All cause hospitalization

HF specific mortality

HF specific hospitalization

All cause duration of hospital stay

HF specific duration of hospital stay

Emergency room visits

Quality of Life

Summary of Findings

One large and seven small randomized controlled trials were obtained from the literature search.

A meta-analysis was completed for four of the seven outcomes including:

All cause mortality

HF-specific mortality

All cause hospitalization

HF-specific hospitalization.

Where the pooled analysis was associated with significant heterogeneity, subgroup analyses were completed using two primary categories:

direct and indirect model of care; and

type of control group (PCP or cardiologist).

The direct model of care was a clinic-based multidisciplinary HF program and the indirect model of care was a physician supervised, nurse-led telephonic HF program.

All studies, except one, were completed in jurisdictions outside North America. (12-19) Similarly, all but one study had a sample size of less than 250. The mean age in the studies ranged from 65 to 77 years. Six of the studies(12;14-18) included populations with a NYHA classification of II-III. In two studies, the control treatment was a cardiologist (12;15) and two studies reported the inclusion of a dietitian, physiotherapist and psychologist as members of the multidisciplinary team (12;19).

All Cause Mortality

Eight studies reported all cause mortality (number of persons) at 1 year follow-up. (12-19) When the results of all eight studies were pooled, there was a statistically significant RRR of 29% with moderate heterogeneity (I2 of 38%). The results of the subgroup analyses indicated a significant RRR of 40% in all cause mortality when SMCCC is delivered through a direct team model (clinic) and a 35% RRR when SMCCC was compared with a primary care practitioner.

HF-Specific Mortality

Three studies reported HF-specific mortality (number of persons) at 1 year follow-up. (15;18;19) When the results of these were pooled, there was an insignificant RRR of 42% with high statistical heterogeneity (I2 of 60%). The GRADE quality of evidence is moderate for the pooled analysis of all studies.

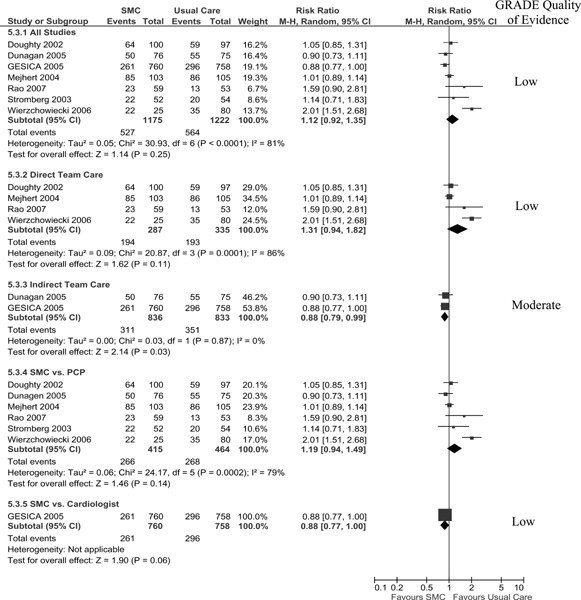

All Cause Hospitalization

Seven studies reported all cause hospitalization at 1-year follow-up (13-15;17-19). When pooled, their results showed a statistically insignificant 12% increase in hospitalizations in the SMCCC group with high statistical heterogeneity (I2 of 81%). A significant RRR of 12% in all cause hospitalization in favour of the SMCCC care group was achieved when SMCCC was delivered using an indirect model (telephonic) with an associated (I2 of 0%). The Grade quality of evidence was found to be low for the pooled analysis of all studies and moderate for the subgroup analysis of the indirect team care model.

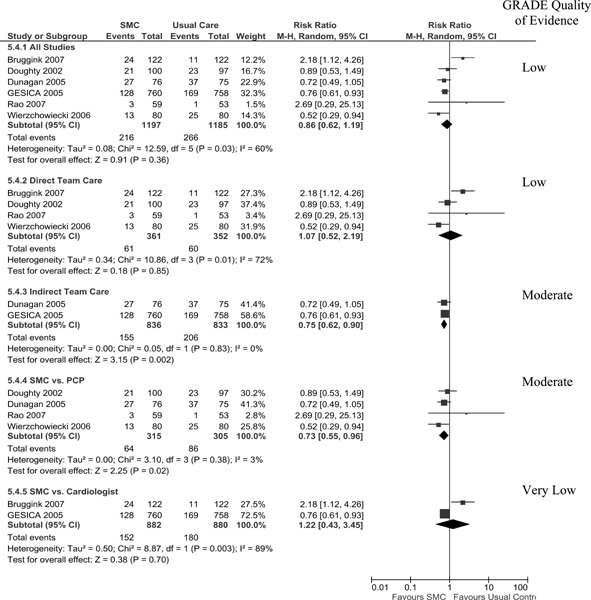

HF-Specific Hospitalization

Six studies reported HF-specific hospitalization at 1-year follow-up. (13-15;17;19) When pooled, the results of these studies showed an insignificant RRR of 14% with high statistical heterogeneity (I2 of 60%); however, the quality of evidence for the pooled analysis of was low.

Duration of Hospital Stay

Seven studies reported duration of hospital stay, four in terms of mean duration of stay in days (14;16;17;19) and three in terms of total hospital bed days (12;13;18). Most studies reported all cause duration of hospital stay while two also reported HF-specific duration of hospital stay. These data were not amenable to meta-analyses as standard deviations were not provided in the reports. However, in general (and in all but one study) it appears that persons receiving SMCCC had shorter hospital stays, whether measured as mean days in hospital or total hospital bed days.

Emergency Room Visits

Only one study reported emergency room visits. (14) This was presented as a composite of readmissions and ER visits, where the authors reported that 77% (59/76) of the SMCCC group and 84% (63/75) of the usual care group were either readmitted or had an ER visit within the 1 year of follow-up (P=0.029).

Quality of Life

Quality of life was reported in five studies using the Minnesota Living with HF Questionnaire (MLHFQ) (12-15;19) and in one study using the Nottingham Health Profile Questionnaire(16). The MLHFQ results are reported in our analysis. Two studies reported the mean score at 1 year follow-up, although did not provide the standard deviation of the mean in their report. One study reported the median and range scores at 1 year follow-up in each group. Two studies reported the change scores of the physical and emotional subscales of the MLHFQ of which only one study reported a statistically significant change from baseline to 1 year follow-up between treatment groups in favour of the SMCCC group in the physical sub-scale. A significant change in the emotional subscale scores from baseline to 1 year follow-up in the treatment groups was not reported in either study.

Conclusion

There is moderate quality evidence that SMCCC reduces all cause mortality by 29%. There is low quality evidence that SMCCC contributes to a shorter duration of hospital stay and improves quality of life compared to usual care. The evidence supports that SMCCC is effective when compared to usual care provided by either a primary care practitioner or a cardiologist. It does not, however, suggest an optimal model of care or discern what the effective program components are. A field evaluation could address this uncertainty.

Background

In August 2008, the Medical Advisory Secretariat (MAS) presented a vignette to the Ontario Health Technology Advisory Committee (OHTAC) on a proposed targeted health care delivery model for chronic care. The proposed model was defined as multidisciplinary, ambulatory, community-based care that bridged the gap between primary and tertiary care, and was intended for individuals with a chronic disease who were at risk of a hospital admission or emergency department visit. The goals of this care model were thought to include: the prevention of emergency department visits, a reduction in hospital admissions and re-admissions, facilitation of earlier hospital discharge, a reduction or delay in long-term care admissions, and an improvement in mortality and other disease-specific patient outcomes.

OHTAC approved the development of an evidence-based assessment to determine the effectiveness of specialized community based care for the management of heart failure, Type 2 diabetes and chronic wounds.

Please visit the Medical Advisory Secretariat Web site at: www.health.gov.on.ca/ohtas to review the following reports associated with the Specialized Multidisciplinary Community-Based care series.

Specialized multidisciplinary community-based care series: a summary of evidence-based analyses

Community-based care for the specialized management of heart failure: an evidence-based analysis

Community-based care for chronic wound management: an evidence-based analysis

Please note that the evidence-based analysis of specialized community-based care for the management of diabetes titled: “Community-based care for the management of type 2 diabetes: an evidence-based analysis” has been published as part of the Diabetes Strategy Evidence Platform at this URL: http://www.health.gov.on.ca/english/providers/program/mas/tech/ohtas/tech_diabetes_20091020.html

Please visit the Toronto Health Economics and Technology Assessment Collaborative Web site at: http://theta.utoronto.ca/papers/MAS_CHF_Clinics_Report.pdf to review the following economic project associated with this series:

Community-based Care for the specialized management of heart failure: a cost-effectiveness and budget impact analysis.

Objective

The objective of this evidence-based analysis was to determine the effectiveness of specialized multidisciplinary care in the management of heart failure (HF).

Clinical Need: Target Population and Condition

Heart failure (HF) is a progressive, chronic condition in which the heart is unable to sufficiently pump blood throughout the body. There are several risk factors for developing the condition including hypertension, diabetes, obesity, previous myocardial infarction and valvular heart disease.(1) Based on data from a 2005 study of the Canadian Community Health Survey (CCHS), the prevalence of congestive heart failure in Canada is approximately 1% of the population over the age of 12.(2). This figure rises sharply after the age of 45, with prevalence reports ranging from 2.2% to 12% in this age category.(3)

Extrapolating this to the Ontario population, an estimated 98,000 residents in Ontario have HF.

Symptomatic HF is associated with high morbidity and mortality. The associated 5-year mortality rate for HF is estimated to be as high as 45%-60%.(20) In the Framingham study, the median survival of symptomatic HF patients was 1.7 years for men and 3.2 years for women. (21) The major mode of death among patients with HF is sudden death (43%), followed by worsening HF (32%), other cardiovascular causes (14%), and non-cardiovascular causes of death (11%). (22)

Disease Management Programs for HF

Disease management programs are multidisciplinary approaches to care for chronic disease that coordinate comprehensive care strategies along the disease continuum and across healthcare delivery systems.(4) Evidence for the effectiveness of disease management programs for HF has been provided by seven systematic reviews completed between 2004-2007 (Table 1) with consistency of effect demonstrated across four main outcomes measures: all cause mortality and hospitalization, and heart-failure specific mortality and hospitalization (Tables 2 and 3). (4-10) Limitations of this evidence include studies with a wide range of follow-up periods (3 months to 18 months), variation in the delivery model (e.g. telephonic, clinic, home visits), poor definitions of usual and multidisciplinary care, and variation in the initiation of the programs (i.e. some were initiated pre-discharge and some post-discharge).

Table 1: Systematic Reviews of Disease Management Programs.

| Study, Year | *Search Date | # RCTs |

|---|---|---|

| Gohler, 2006 | 1966 - 2005 | 36 |

| Roccaforte, 2005 | 1980 - 2004 | 33 |

| Holland, 2005 | 1966 - 2004 | 30 |

| Taylor, 2005 | 1966 - 2003 | 21 |

| McAlister, 2004 | 1966 - 2003 | 29 |

| Gonseth, 2004 | 1966 - 2003 | 27 |

| Gwadry-Sridhar, 2004 | 1966 - 2000 | 8 |

Medline search dates

Table 2: All Cause Mortality and Hospitalization Results of Systematic Reviews of Disease Management.

| Study, Year | All Cause Mortality No. RCTs |

All Cause Mortality [RR] | I2% [p-value]* | All Cause Hospitalization No. RCTs |

All Cause Hospitalization [RR] |

I2 % [p-value]* |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gohler, 2006 | 30 | 0.81 [0.70, 0.93] | 22.0 | 32 | 0.84 [0.77, 0.91] | 57.0 |

| Roccaforte, 2005 | 28 | 0.85 [0.73, 0.99] | 31.0 | 25 | 0.84 [0.70, 1.02] | 40.0 |

| Holland, 2004 | 27 | 0.79 [0.69, 0.92] | 35.5 | 21 | 0.87 [0.79, 0.95] | 54.3 |

| McAlister, 2004 | 22 | 0.83 [0.70, 0.99] | [0.15] | 23 | 0.84 [0.75, 0.93] | [0.01] |

| Gonseth, 2004 | 16 | 0.88 [0.79, 0.97] | [0.25] | |||

| Gwadry-Sridhar, 2004 | 6 | 0.98 [0.72, 1.34] | [0.90] | 8 | 0.79 [0.68, 0.91] | [0.20] |

P-value for heterogeneity

Table 3: HF-Specific Mortality and hospitalization results of systematic reviews of disease management programs.

| Study, Year | HF-Specific Mortality No. RCT |

HF-Specific Mortality RR |

I2 %[p-value]* | HF-Specific Hospitalization No. RCT |

HF-Specific Hospitalization RR |

I2 %[p-value]* |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Roccaforte, 2005 | 4 | 0.41 [0.19, 0.90] | 54 | 20 | 0.69 [0.63, 0.77] | None |

| Holland, 2004 | 16 | 0.70 [0.61, 0.81] | [0.04] | |||

| Taylor, 2005 | 1 | 0.17 [0.06, 0.66] | NA | 9 | ||

| McAlister, 2004 | 19 | 0.73 [0.66, 0.82] | [0.36] | |||

| Gonseth, 2004 | 11 | 0.70 [0.62, 0.79] | 27.1 | |||

P-value for heterogeneity

In 2007, MAS completed a systematic review of disease management programs compared to usual care for HF with a fixed follow-up period of 1 year (unpublished work). Other inclusion criteria were:

RCTs comparing disease management programs to usual care

Persons hospitalized for HF

Reporting at least on of the following outcomes: all cause mortality, all cause hospitalization, or hospitalization due to cardiovascular symptoms

Including at least one scheduled appointment after discharge (whether clinic, phone, or home visit)

Recruiting HF patients on admission or discharge from hospital

Sample size ≥50 patients

English language studies.

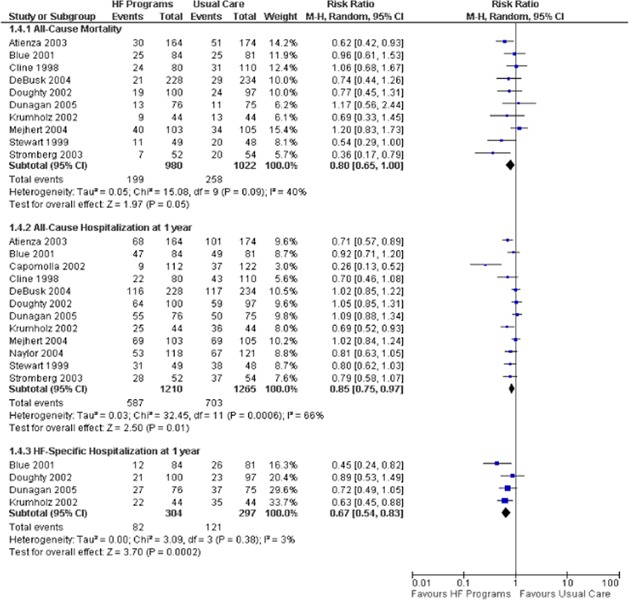

The pooled results of 12 RCTS (13;14;16;18;23-30) indicated a statistically significant, 15% relative risk reduction (RRR) in all cause hospitalization, while the results of four studies (13;14;24;28) showed a 33% RRR in HF-specific hospitalization at 1-year follow-up (Figure 1). There was a 20% RRR in all cause mortality at 1-year with the upper confidence interval (CI) at 1.00 (13;14;16;18;23;24;26-28;30). It was noted that each RCT had a unique program design in terms of the number of follow-up visits scheduled, type of visit (clinic, home, and phone), type of practitioners involved in the program, education materials provided, program duration. Inter-study differences were also noted in the age and severity of disease in the patient populations examined. These program and patient characteristics may be responsible for the heterogeneity seen in the effect estimate for all cause mortality and all cause hospitalization at 1 year.

Figure 1: Meta-analysis of HF Disease Management Programs Compared with Usual Care.

While the heterogeneity in the disease management programs creates uncertainty as to the optimal program design and execution, the results of this analysis nonetheless support the development of a disease management program. This could perhaps be employed as an “intermediate” care stage between primary and tertiary care for persons with HF to reduce the burden on hospital services, particularly emergency department visits and unplanned hospitalizations. However, while disease management programs are by definition as multidisciplinary, the published evidence lacks consistency and clarity as to the exact nature of each program, and the usual care comparator is generally ill defined. Consequently, the effectiveness of multidisciplinary care for the management of persons with HF is still somewhat uncertain. MAS, therefore, completed a systematic review of multidisciplinary care disease management programs compared to a well-defined usual care group for persons with HF.

Evidence-Based Analysis of Effectiveness

Research Question

What is the effectiveness of SMCCC compared with usual care for persons with HF?

Methods

A comprehensive literature search was completed of electronic databases including MEDLINE, MEDLINE In-Process and Other Non-Indexed Citations, EMBASE, Cochrane Library and Cumulative Index to Nursing & Allied Health Literature. Bibliographic references of selected studies were also searched. The search strategy is presented in full in Appendix 1. After a review of the title and abstracts, relevant studies were obtained and the full reports evaluated. All studies meeting explicit inclusion and exclusion criteria were retained. Where appropriate, a meta-analysis was undertaken to determine the pooled estimate of effect of specialized multidisciplinary community-based care for explicit outcomes. The quality of the body of evidence, defined as one or more relevant studies was determined using GRADE Working Group criteria.(11)

Inclusion Criteria

Randomized controlled trial

Systematic review with meta analysis

Population includes persons with New York Heart Association (NYHA) classification 1-IV HF

The intervention includes a team consisting of a nurse and physician one of which is a specialist in HF management.

The control group receives care by a single practitioner (e.g. primary care physician (PCP) or cardiologist)

The intervention begins after discharge from the hospital

The study reports 1-year outcomes

Exclusion Criteria

The intervention is delivered predominately through home-visits

Studies with mixed populations where discrete data for HF is not reported

Outcomes

All cause mortality

All cause hospitalization

HF-specific mortality

HF-specific hospitalization

All cause duration of hospital stay

HF-specific duration of hospital stay

Emergency room visits

Quality of Life

Assessment of Quality of Evidence

The quality of the body of evidence was examined according to the GRADE Working Group criteria.(11) Quality refers to criteria such as the adequacy of allocation concealment, blinding, losses to follow-up, and completion of an intention to treat analysis. Consistency refers to the similarity of effect estimates across studies. If there is important unexplained inconsistency in the results, confidence in the estimate of effect for that outcome decreases. Differences in the direction of effect, the size of the effect, and the significance of the differences guide the decision about whether an important inconsistency exists. Directness refers to the extent to which the interventions, population, and outcome measures are similar to those of interest. The GRADE Working Group uses the following definitions in grading the quality of the evidence:

| High: | Further research is very unlikely to change confidence in the estimate of effect. |

| Moderate: | Further research is likely to have an important impact on confidence in the estimate of effect and may change the estimate. |

| Low: | Further research is very likely to have an important impact on confidence in the estimate of effect and is likely to change the estimate |

| Very Low: | Any estimate of effect is very uncertain |

Results of Evidence-Based Analysis

Literature Search

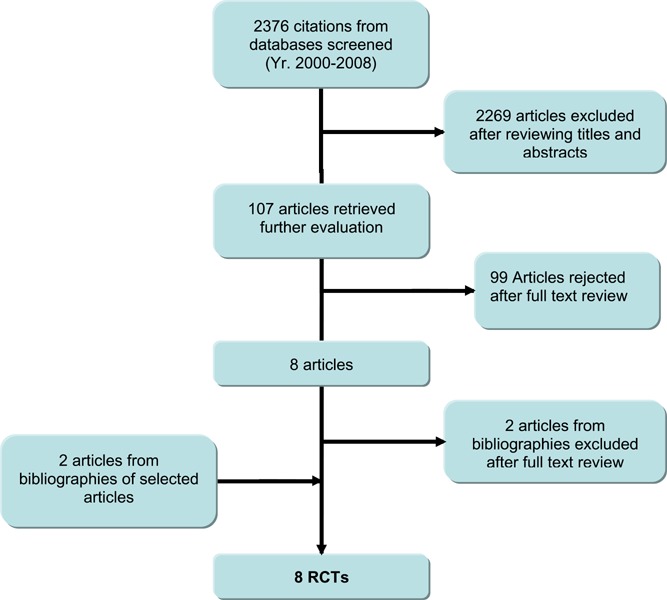

One large and seven small randomized controlled trials were obtained from the literature search (see Figure 2, and Table 4)

Figure 2: Systematic Literature Review Process and Results.

Table 4: Quality of Evidence of Included Studies*(31).

| Study Design | Level of Evidence |

Number of Eligible Studies |

|---|---|---|

| Large RCT, systematic review of RCTs | 1 | 0 |

| Large RCT unpublished but reported to an international scientific meeting | 1(g) | 1 |

| Small RCT | 2 | 7 |

| Small RCT unpublished but reported to an international scientific meeting | 2(g) | 0 |

| Non-RCT with contemporaneous controls | 3a | 0 |

| Non-RCT with historical controls | 3b | 0 |

| Non-RCT presented at international conference | 3(g) | 0 |

| Surveillance (database or register) | 4a | 0 |

| Case series (multisite) | 4b | 0 |

| Case series (single site) | 4c | 0 |

| Retrospective review, modeling | 4d | 0 |

| Case series presented at international conference | 4(g) | 0 |

g refers to grey literature; RCT, randomized controlled trial.

Characteristics of Included Studies

All studies were completed in jurisdictions outside North America (12-19), other than that done by Dunagan et al. (14) Similarly, other than the GESICA study (15), all had a sample size less than 250 persons. The mean age in the studies ranged from 65 to 77 years. Six of the studies(12;14-18) included populations with a NYHA classification of II-III, while the studies completed by Wierzchowiecki et al. (19) and Doughty et al. (13) included a proportion of NYHA classification IV study participants. In two studies, the control treatment was a cardiologist (12;15) and two studies reported the inclusion of a dietitian, physiotherapist and psychologist as members of the multidisciplinary team (12;19). Table 5 presents an overview of the characteristics of the studies included for review and Table 6 reports the methodology characteristics of each.(12-19). Complete study details are reported in Appendix 3.

Table 5: Characteristics of Studies Included for Analysis.

| Study | Country | N | Age (mean, yr) | NYHA class II and *III (%) | Treatment | Control | Other Disciplines |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Rao 2007 |

UK | 112 | 72 | 90 | HF RN, Cardiologist | PCP | n/a |

| Bruggink 2007 |

Netherlands | 240 | 71 | *96 | CV RN, HF Physician | Cardiologist | Dietitian |

| Wierzchowiecki 2006 |

Poland | 160 | 68 | 60 IV-40 |

HF RN, Cardiologist | PCP | Physiotherapist psychologist |

| Mejhert 2004 |

Sweden | 208 | 76 | 99 | Nurse, Cardiologist | PCP | n/a |

| Stromberg 2003 |

Sweden | 106 | 77 | 89 | CV RN, Cardiologist | PCP | n/a |

| Doughty 2002 |

New Zealand | 197 | 73 | *24 IV-76 |

Nurse Practitioner Cardiologist | PCP | PCP |

| Dunagan 2005 |

USA | 151 | 70 | 91 | RN, Cardiologist | PCP | n/a |

| GESICA 2005 |

Argentina | 1518 | 65 | I-19 III to IV-49; |

HF RN, Cardiologist | Cardiologist | n/a |

Table 6: Individual study methodology characteristics.

| Study | N | Adequate randomization methods |

Baseline comparable |

Adequate Allocation Concealment |

Blinding of outcome assessors |

Sample Size Calculation |

Losses to †FU (%) |

#ITT |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Rao 2007 |

112 | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ |

| Bruggink 2007 |

112 | ✓ | *†Except for gender | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | 0 | ✓ |

| Wierzchowiecki 2006 |

160 | ✓ | ✓ | Unclear | Not reported | Not reported | Not reported | Not reported |

| Mejhert 2004 |

208 | ✓ | ✓ | $✓ | ¶No | ✓ | 0 | ✓ |

| Stromberg 2003 |

106 | ✓ | * Except for the number of persons with hypertension and ‡†diabetes | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | 0 | ✓ |

| Doughty 2002 |

197 | ✓ | ✓ | Unclear | ✓ | ✓ | 0.9 | ✓ |

| Dunagan 2005 |

151 | ✓ | *† Except for mean ACE inhibitor dose | Unclear | ✓ | ✓ | 0.9 | ✓ |

| GESICA 2005 |

1518 | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | 0 | ✓ |

Significantly higher proportion or dose in treatment group

Adjusted analysis for baseline differences did not change results

Significantly higher proportion in the control group

Primary end-point was patient self administered Quality of life questionnaire

ITT is intention to treat analysis

Adequate allocation concealment methods confirmed by author

The description of the multidisciplinary treatment group in each of the eight studies was reviewed and a qualitative analysis was undertaken to determine the components of the HF program. Table 7 reports the components that were developed from the study specific descriptions.

Table 7: HF Program Components.

| Components | Description |

|---|---|

| Disease specific education | The program provided education about the sings and symptoms and aetiology of HF |

| Medication Education | The program provided education about the side effects of HF medication, the relationship of medication to HF management and the importance of medication compliance |

| Medication Titration | The program titrated the dose of at least the diuretics and possible other HF specific medication (ACEI, Beta-blockers) |

| Diet Counselling | The program provided counselling on sodium and fluid restricted diets |

| Physical Activity Counselling | The program provided counselling on physical activity such as walking, and working and leisure activities. |

| Lifestyle Counselling | The program provided counselling on smoking cessation and alcohol intake |

| Self care support behaviours | The program encouraged the patient to monitor his/her daily weights, HF symptoms and or self manage the diuretic titration |

| Self-care tools | The program offered patient dairies for daily weight, diet and or symptom recording |

| Evidence-based guidelines | The program followed evidence based guidelines for medication management or other HF specific education and/or counselling |

| Regular follow-up (F/U) | The program offered regular follow-up visits between the beginning and end of the treatment phase |

The study components were further categorized using the Wagener’s model of Chronic Care (Table 8). (32) All studies included a decision support component in their program and seven of the eight studies also included a self management component. Only two studies (13;18) reported using evidence-based guidelines and five studies included scheduled follow-up visits (12-14;16;19). Disease specific education and diet counselling the program components most often carried out by the multidisciplinary treatment team.

Table 8: Components of Specialized Multidisciplinary Disease Management Program, Wagner’s Chronic Care Model.

| Study | Wagner’s Chronic Care Model | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| *Decision Support | *Self-Management | *Delivery System Design | |||||||||

| Disease specific education |

Education about medication |

Titration of medication |

Diet counselling |

Physical activity counselling |

Lifestyle counselling |

Self-care support behaviour |

Self-care tools |

Evidence-based guidelines used |

Regular F/U |

||

| Rao 2007 |

✓ | ✓ | ✓ | Diary | |||||||

| Bruggink 2007 |

✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | Diary | ✓ | |||||

| Wierzchowiecki 2006 |

✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | Diary | ✓ | |||

| Mejhert 2004 |

✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | |||||

| Stromberg 2003 |

✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ||||

| Doughty 2002 |

✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | Diary | ✓ | ✓ | |||

| Dunagan 2005 |

✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | |||||||

| GESICA 2005 |

✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ||||

Components of Wagner’s Chronic Care Model

Summary of Existing Evidence

A meta-analysis was completed for 4 of the 7 outcomes including:

All cause mortality

HF-specific mortality

All cause hospitalization

HF-specific hospitalization.

Where the pooled analysis was associated with significant heterogeneity, subgroup analyses were completed using two primary categories:

direct and indirect model of care; and

type of control group (PCP or cardiologist).

The direct model of care was a clinic-based multidisciplinary HF program and the indirect model of care was a physician supervised, nurse-led telephonic HF program. Appendix 4 reports the GRADE evidence profiles for each of these four outcomes.

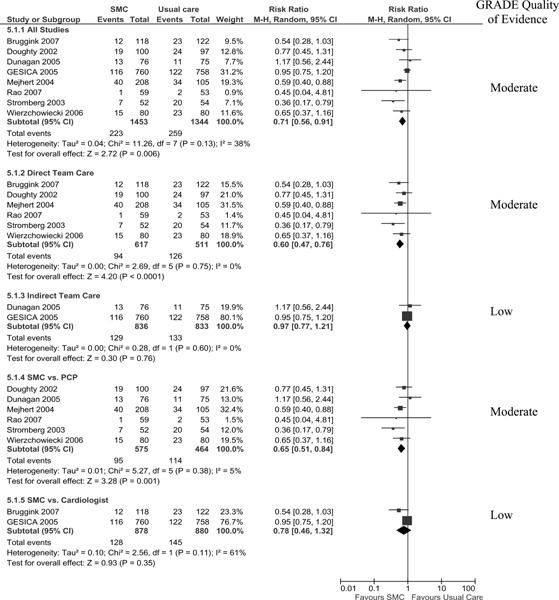

All Cause Mortality

Eight studies reported all cause mortality (number of persons) at 1 year follow-up (Figure 3). (12-19) When the results of all eight studies are pooled, there is a statistically significant RRR of 29% with moderate heterogeneity (I2 of 38%). The results of the subgroup analyses indicate a significant RRR of 40% in all cause mortality when SMCCC is delivered through a direct team model (clinic) and a 35% RRR when SMCCC is compared with a primary care practitioner.

Figure 3: Meta-analysis for Outcome of All-Cause Mortality.

The GRADE quality of evidence is moderate for the pooled analysis of all studies and for the subgroup analysis of the direct team model.

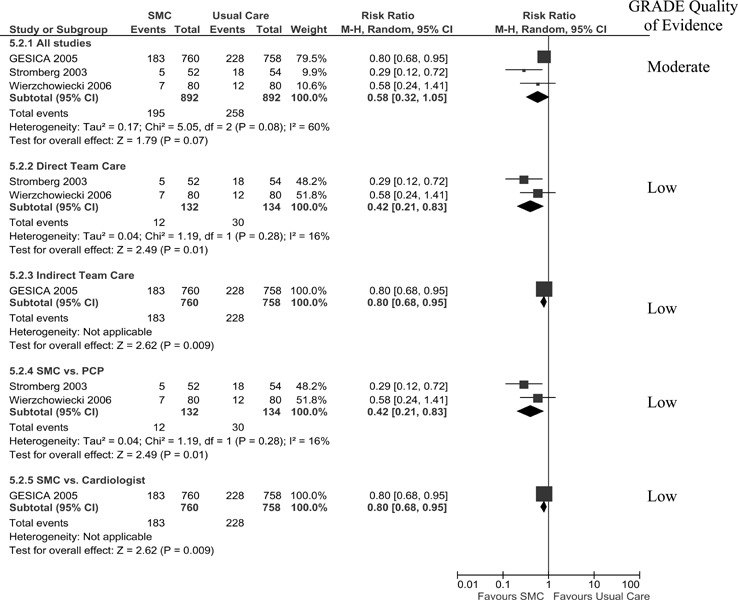

HF-Specific Mortality

Three studies reported HF-specific mortality (number of persons) at 1 year follow-up (Figure 4). (15;18;19) When the results of these studies are pooled, there is an insignificant RRR of 42% with high statistical heterogeneity (I2 of 60%). The results of subgroup analyses, however, indicate a significant 58% RRR in HF-specific mortality when SMCCC is delivered through a direct team model (clinic) but only a 20% RRR when delivered through an indirect model (telephonic model). A similar RRR occurred with the direct team model when SMCCC is compared to a primary care physician, as well with the indirect model when SMCCC was compared to a cardiologist. This is because the same studies are used in both subgroup analyses. It cannot, therefore, be determined from the subgroup analyses whether the effect is due to the type of model (direct or indirect) or the type comparator (PCP or cardiologist). The GRADE quality of evidence is moderate for the pooled analysis of all studies.

Figure 4: Meta-analysis for Outcome of HF-Specific Mortality.

All Cause Hospitalization

Seven studies reported all cause hospitalization (number of persons) at 1-year follow-up (13-15;17-19). As displayed in Figure 5, a significant RRR of 12% in all cause hospitalization was only achieved when SMCCC was delivered using an indirect model (telephonic). All other analyses resulted in an insignificant risk reduction. The Grade quality of evidence was found to be low for the pooled analysis of all studies and moderate for the subgroup analysis of the indirect team care model.

Figure 5: Meta-analysis for Outcome of All-Cause Hospitalization.

HF-Specific Hospitalization

Six studies reported HF-specific hospitalization (number of persons) at 1 year follow-up (Figure 6) (13-15;17;19). When the results of these studies were pooled, there was an insignificant RRR of 14% with high statistical heterogeneity (I2 of 60%). The results of subgroup analyses indicate a significant 25% RRR when SMCCC is delivered through an indirect team model (telephonic) and a 27% RRR when SMCCC is compared with a primary care practitioner. The quality of the evidence for the pooled analysis of all studies is low and moderate for the subgroup analyses of an indirect team care model and SMCCC compared with a primary care practitioner.

Figure 6: Meta-analysis for Outcome of HF-Specific Hospitalization.

Duration of Hospital Stay (All cause and HF-specific)

Seven studies reported duration of hospital stay, four in terms of mean duration of stay in days (14;16;17;19) and three in terms of total hospital bed days (12;13;18). Most studies reported all cause duration of hospital stay except for Wierzchowiecki et al., and Doughty et al., who also reported HF-specific duration of hospital stay. These data were not amenable to meta-analyses as standard deviations were not provided in the reports.

In general, and except for the study by Rao et al.(17), it appears that persons receiving SMCCC had shorter hospital stays, whether measured as mean days in hospital or total hospital bed days.

Table 9: Duration of All Cause and †HF-Specific Hospital Stay.

| Study | Duration of Stay (mean days ± SD) |

Total Hospital Bed Days (mean) |

||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| SMCCC | Usual Care | SMCCC | Usual Care | |

| Rao 2007 | 12±16 | 11.7±14 | ||

| Wierzchowiecki 2006 |

*9.3 †*9.5 |

12.5 13.9 |

||

| Mejhert 2004 | 3.7 | 4.1 | ||

| Dunagan 2005 | 13.3 | 14.5 | ||

| Bruggink 2007 | ¶359 | 644 | ||

| Stromberg 2003 | 688 | 976 | ||

| Doughty 2002 | 1074 †353 |

1170 561 |

||

P <0.05

RR 0.56, 95% CI 0.49-0.64

Emergency Room Visits

Only one study, Dunagan et al., reported emergency room visits. (14) This was presented as a composite of readmissions and ER visits and the authors reported that 77% (59/76) of the SMCCC group and 84% (63/75) in the usual care group were either readmitted or had an ER visit within the 1 year follow-up period (P=0.029).

Quality of Life

Quality of life was reported in five studies using the Minnesota Living with HF Questionnaire (MLHFQ) (12-15;19) and in one study using the Nottingham Health Profile Questionnaire. (16) The MLHFQ results are reported in our analysis (Table 10). The questionnaire is positively scored such that a higher score indicates a worsening quality of life and a negative change value indicates an improvement in quality of life from baseline to 1 year follow-up. Two studies reported the mean score at 1 year follow-up, although did not provide the standard deviation of the mean in their report. One study reported the median and range scores at 1 year follow-up in each group. Two studies reported the change scores of the physical and emotional subscales of the MLHFQ. Doughty et al. (13), but not Dunagan et al. (14), reported a statistically significant change from baseline to 1 year follow-up between treatment groups in favour of the SMCC group in the physical sub-scale. However, neither Doughty et al. (13) nor Dunagan et al. (14) reported a significant change in the emotional subscale scores from baseline to 1 year follow-up in the treatment groups.

Table 10: Minnesota Living with Heart Failure Questionnaire Scores.

| Study | Score at 1 year (mean ± standard deviation) |

Significant improvement in SMCC group? |

|

|---|---|---|---|

| SMCC | Usual Care | ||

| Bruggink 2007 | 30.2 | 34.5 | Yes |

| Gesica 2005 | 30.6 | 35.0 | Yes |

| Wierzchowiecki 2006 |

*14 (4.5, 2.6) |

*30 (20, 45) |

Yes |

| Doughty 2002 †Physical Scale †Emotional Scale |

-11.1 -3.3 |

-5.8 -3.3 |

Yes No |

| Dunagan 2005 †Physical Scale †Emotional Scale |

8.6 ± 11.4 1.5 ± 6.6 |

7.2 ± 12.0 2.9 ± 7.1 |

No No |

Median (25th, 75th percentile)

Change scores

Conclusion

There is moderate quality evidence that SMCC:

i) Reduces all cause mortality by 29-40%

ii) Reduces all cause hospitalization by 12 %

iii) Reduction HF-specific hospitalization by 25-27%

There is low quality evidence that SMCC:

i) Reduces HF-specific mortality by 58%

ii) Contributes to a shorter duration of hospital stay

iii) Improves QoL compared to usual care

The evidence supports that SMCC is effective when compared to usual care provided by either a primary care practitioner or cardiologist. It does not, however, suggest an optimal model of care or discern what the effective program components are. A field evaluation could address this uncertainty.

Appendices

Appendix 1: Literature Search Strategies

Search date: October 3, 2008

Databases searched: OVID MEDLINE, MEDLINE In-Process and Other Non-Indexed Citations, EMBASE, Cochrane Library, CINAHL, INAHTA/CRD

Database: Ovid MEDLINE(R) <1996 to September Week 4 2008>

Search Strategy:

exp Intermediate Care Facilities/ (224)

(intermedia* adj2 care).ti,ab. (515)

exp ambulatory care/ (15708)

exp Ambulatory Care Facilities/ (14913)

exp Outpatients/ (3640)

((outpatient* or ambulatory) adj2 (care* or service* or clinic* or facility or facilities)).ti,ab. (15903)

exp Patient Care Team/ (22174)

exp Nursing, Team/ (624)

exp Cooperative Behaviour/ (12391)

exp Interprofessional Relations/ (20840)

exp "Delivery of Health Care, Integrated"/ (5255)

team*.ti,ab. (33700)

(multidisciplin$ or multi-disciplin$ or interdisciplin$ or inter-disciplin$ or collaborat$ or cooperat$ or co-operat$ or multi?special$).ti,ab. (92766)

(integrat$ or share or shared or sharing).ti,ab. (168525)

exp Community Health Services/ (181506)

exp Program Evaluation/ (30090)

exp "episode of care"/ (912)

exp Professional Role/ (36081)

exp Primary Health Care/ (34220)

exp "Continuity of Patient Care"/ (6209)

exp Disease Management/ (6030)

disease management program*.ti,ab. (796)

(patient care adj2 manage$).ti,ab. (245)

exp Case Management/ or exp Subacute Care/ (6518)

(care adj2 model*).ti,ab. (2972)

exp Program Development/ (11557)

or/1-26 (565973)

limit 27 to yr="2000 - 2008" (425540)

limit 28 to (english language and humans) (319291)

limit 29 to (controlled clinical trial or meta analysis or randomized controlled trial) (14488)

exp Technology Assessment, Biomedical/ or exp Evidence-based Medicine/ (34149)

(health technology adj2 assess$).mp. [mp=title, original title, abstract, name of substance word, subject heading word] (617)

(meta analy$ or metaanaly$ or pooled analysis or (systematic$ adj2 review$)).mp. or (published studies or published literature or medline or embase or data synthesis or data extraction or cochrane).ab. (64522)

exp Random Allocation/ or random$.mp. [mp=title, original title, abstract, name of substance word, subject heading word] (368010)

exp Double-Blind Method/ (52776)

exp Control Groups/ (702)

exp Placebos/ (9187)

(RCT or placebo? or sham?).mp. [mp=title, original title, abstract, name of substance word, subject heading word] (93365)

or/30-38 (474587)

29 and 39 (38798)

((heart failure or cardiac failure or coronary failure or ventricular failure or myocardial failure) adj2 (program* or clinic* or center* or centre*)).mp. [mp=title, original title, abstract, name of substance word, subject heading word] (981)

limit 41 to (english language and humans and yr="2000 - 2008") (689)

39 and 42 (168)

exp Heart Failure/ (30045)

40 and 44 (443)

45 or 43 (553)

Database: EMBASE <1980 to 2008 Week 39>

Search Strategy:

(intermedia* adj2 care).ti,ab. (631)

exp ambulatory care/ (12187)

exp Outpatient Department/ (9466)

exp outpatient care/ (12499)

((outpatient* or ambulatory) adj2 (care* or service* or clinic* or facility or facilities)).ti,ab. (20467)

exp TEAM NURSING/ (6)

exp Cooperation/ (13299)

exp TEAMWORK/ or team*.ti,ab. (41041)

exp Integrated Health Care System/ (231)

(multidisciplin$ or multi-disciplin$ or interdisciplin$ or inter-disciplin$ or collaborat$ or cooperat$ or co-operat$ or multi?special$).ti,ab. (116921)

(integrat$ or share or shared or sharing).ti,ab. (208598)

exp Case Management/ (454)

exp Rehabilitation Care/ (2739)

exp community care/ (23465)

exp Social Care/ (34975)

exp ambulatory care nursing/ (5)

exp primary health care/ (41469)

*Disease Management/ (254)

disease management program*.ti,ab. (869)

(patient care adj2 manage$).ti,ab. (196)

exp Program Development/ (753)

(care adj2 model*).ti,ab. (2336)

exp Health Program/ (53182)

or/1-23 (511612)

limit 24 to (human and english language and yr="2000 - 2009") (194121)

Randomized Controlled Trial/ (162835)

exp Randomization/ (26273)

exp RANDOM SAMPLE/ (1261)

exp Biomedical Technology Assessment/ or exp Evidence Based Medicine/ (292930)

(health technology adj2 assess$).mp. [mp=title, abstract, subject headings, heading word, drug trade name, original title, device manufacturer, drug manufacturer name] (645)

(meta analy$ or metaanaly$ or pooled analysis or (systematic$ adj2 review$) or published studies or published literature or medline or embase or data synthesis or data extraction or cochrane).ti,ab. (61896)

Double Blind Procedure/ (70620)

exp Triple Blind Procedure/ (12)

exp Control Group/ (2245)

exp PLACEBO/ or placebo$.mp. or sham$.mp. [mp=title, abstract, subject headings, heading word, drug trade name, original title, device manufacturer, drug manufacturer name] (207387)

(random$ or RCT).mp. [mp=title, abstract, subject headings, heading word, drug trade name, original title, device manufacturer, drug manufacturer name] (420855)

(control$ adj2 clinical trial$).mp. [mp=title, abstract, subject headings, heading word, drug trade name, original title, device manufacturer, drug manufacturer name] (279987)

or/26-37 (778561)

38 and 25 (36604)

((heart failure or cardiac failure or coronary failure or ventricular failure or myocardial failure) adj2 (program* or clinic* or center* or centre*)).ti,ab. (1310)

limit 40 to (human and english language and yr="2000 - 2009") (651)

38 and 41 (231)

exp Heart Failure/ (115679)

39 and 43 (1181)

42 or 44 (1336)

CINAHL

# Query Limiters/Expanders Last Run Via Results

S43 (S42 and S39)

Search Screen - Advanced Search

Database - CINAHL;Pre-CINAHL 272

S42 (S41 or S40)

Search Screen - Advanced Search

Database - CINAHL;Pre-CINAHL 12707

S41 heart failure or cardiac failure or coronary failure or ventricular failure or myocardial failure

Search Screen - Advanced Search

Database - CINAHL;Pre-CINAHL 12700

S40 (MH "Heart Failure, Congestive+")

Search Screen - Advanced Search

Database - CINAHL;Pre-CINAHL 9671

S39 S37 OR S38 Limiters - Published Date from: 200001-200912; Language: English; Year of Publication from: 2000-2009

Search Screen - Advanced Search

Database - CINAHL;Pre-CINAHL 10781

S38 (MH "Cardiovascular Care")

Search Screen - Advanced Search

Database - CINAHL;Pre-CINAHL 487

S37 (S36 and S23)

Search Screen - Advanced Search

S36 (S35 or S34)

Search Screen - Advanced Search

S35 (S33 or S32 or S31 or S30 or S29)

Search Screen - Advanced Search

S34 S28 or S27 or S26 or S25 or S24

Search Screen - Advanced Search

S33 control* N2 clinical trial*

Search Screen - Advanced Search

S32 (MH "Control (Research)+")

Search Screen - Advanced Search

S31 (MH "Placebos")

Search Screen - Advanced Search

S30 (MH "Double-Blind Studies") or (MH "Single-Blind Studies") or (MH "Triple-Blind Studies")

Search Screen - Advanced Search

S29 meta analy* or metaanaly* or pooled analysis or (systematic* N2 review*) or published studies or medline or embase or data synthesis or data extraction or cochrane Search modes -Boolean/Phrase Interface - EBSCOhost

Search Screen - Advanced Search

S28 (MH "Cochrane Library") or (MH "Systematic Review")

Search Screen - Advanced Search

S27 (MH "Meta Analysis")

Search Screen - Advanced Search

S26 health technology N2 assess*

Search Screen - Advanced Search

S25 random* or sham* or RCT*

Search Screen - Advanced Search

S24 (MH "Random Assignment") or (MH "Random Sample+")

Search Screen - Advanced Search

S23 (S22 or S21 or S20 or S19 or S18 or S17 or S16 or S15 or S14 or S13 or S12 or S11 or S10 or S9 or S8 or S7 or S6 or S5 or S4 or S3 or S2 or S1) Limiters - Published Date from: 200001-200912; Language: English

Search Screen - Advanced Search

S22 multidisciplin* or multi-disciplin* or interdisciplin* or inter-disciplin* or collaborat* or cooperat* or co-operat* or multi-special* or multispecial*

Search Screen - Advanced Search

S21 (MH "Nurse-Managed Centers")

Search Screen - Advanced Search

S20 team*

Search Screen - Advanced Search

S19 care N2 model*

Search Screen - Advanced Search

S18 (MH "Professional Role+")

Search Screen - Advanced Search

S17 (MH "Subacute Care")

Search Screen - Advanced Search

S16 (MH "Case Management")

Search Screen - Advanced Search

S15 disease management program*

Search Screen - Advanced Search

S14 (MH "Disease Management")

Search Screen - Advanced Search

S13 (MH "Continuity of Patient Care")

Search Screen - Advanced Search

S12 (MH "Primary Health Care")

Search Screen - Advanced Search

S11 (MH "Community Health Services")

Search Screen - Advanced Search

S10 (MH "Health Care Delivery, Integrated")

Search Screen - Advanced Search

S9 (MH "Teamwork")

Search Screen - Advanced Search

S8 (MH "Interprofessional Relations+") or (MH "Collaboration")

Search Screen - Advanced Search

S7 (MH "Cooperative Behaviour")

Search Screen - Advanced Search

S6 (MH "Multidisciplinary Care Team+") or (MH "Team Nursing")

Search Screen - Advanced Search

S5 outpatient* care* or outpatient* service* or outpatient* clinic* or outpatient* facility or outpatient* facilities

Search Screen - Advanced Search

S4 ambulatory care* or ambulatory service* or ambulatory clinic* or ambulatory facility or ambulatory facilities

Search Screen - Advanced Search

S3 (MH "Outpatients") or (MH "Outpatient Service")

Search Screen - Advanced Search

S2 (MH "Ambulatory Care") or (MH "Ambulatory Care Facilities+") or (MH "Ambulatory Care Nursing")

Search Screen - Advanced Search

S1 intermedia* N2 care

Search Screen - Advanced Search

Appendix 2: Included Studies

| BRUGGINK 2007 | |

|---|---|

| Methods | A parallel group RCT. |

| Participants | Hospitalized persons or persons visiting a cardiology outpatient clinic with a NYHA class of II or IV HF were enrolled in the study. |

| Interventions | Randomized by computer generated allocation to either intensive follow-up at a HF outpatient clinic (in addition to usual care) led by a HF physician and a cardiovascular nurse. Intervention started within a week after hospital discharge or referral from the outpatient clinic, Weeks 1 and 3 visit to HF clinic: verbal and written comprehensive education was given about the disease, medication, compliance and possible adverse events. Advice was also given on diet, salt and fluid restriction, weight control, early recognition of worsening HF, physical exercise and rest, and when to seek help. A patient diary was given and appointments with a dietician were made Follow-up visits were at weeks 5 and 7, as well as at 3, 6, 9, and 12 months after study enrolment. At follow-up, a cardiovascular nurse provided counselling, check up, and reinforcement of education and a short physical examination. At the 6 and 9 months visit, the physician assessed the condition of the patient, optimized treatment, and performed an overall assessment with the nurse. Components of Program: disease specific education, education regarding medication, advice on diet, physical exercise. A patient diary was also used Usual care group was managed by a cardiologist according to the guidelines of the European Society of Cardiology (version 2001). All patients seen at an outpatient clinic. |

| Outcomes | An external clinical end-point committee of three experienced cardiologists blinded to the allocation status of the patient adjudicated all causes of hospitalization and health. Primary end-point was the composite of incidence of hospitalization for worsening HF and/or all cause mortality. Additional end-points were: Left ventricular ejection fraction’, NYHA class, quality of life, NT-proBNP, and self-care behaviour. Time to death, use of HF medication and costs of care were determined. |

| Notes | Other disciplines included dietician No losses to follow-up Baseline characteristics comparable between groups except for gender. The treatment group was 66% male and the control group was 79% male. Adjustment for baseline difference in gender did not alter the results of the study. |

| Allocation Concealment | Randomized computer generated allocation was used |

| DOUGHTY 2002 | |

| Methods | Randomized controlled single-centre study Cluster randomization using the general practitioner as the unit of randomization was carried out. Patients assigned to groups based on the randomization of their GP. |

| Participants | Patients admitted to general medical wards at Auckland Hospital with a primary diagnosis of HF. |

| Interventions | Treatment group: patients were scheduled for an outpatient clinical review with the study team within 2 weeks of discharge from hospital, as well as six weekly visits alternating between the GP and the HF clinic. Patients were free to see their GP as they wished. Program components: disease specific education (signs and symptoms of HF), advice for dietary and exercise, patient diary for daily weights, medication record, clinical notes and appointments, as well as an education booklet were provided. Control group: care was provided by the general practitioner |

| Outcomes | Primary end-points were a combination of death, hospital readmission (time to first event), and quality of life questionnaire. Secondary end-points included all cause hospital readmissions, all cause hospital bed days and readmissions for worsening HF. |

| Notes | Computer- randomization was used to allot GPs to treatment or control groups. The decision to request admission rested with the GP The authors stated that contamination of the control group management may have occurred if a general practitioner had patients in both groups, but this is unlikely as the unit of randomization was the general practitioner. Sample size was predicated on a 30% reduction in the combined end-point of death or hospital readmission [alpha 0.05 (2-tailed), and 80% power]. The influence of clustering was determined to be insignificant so the data was analyzed using the unit of randomization assumed to be the individual. The data was also analyzed by the clustering unit (GP). |

| Allocation Concealment | Not reported. |

| DUNAGAN 2005 | |

| Methods | An RCT with a randomly permuted bloc design with a 1:1 randomization of patients allocated to randomly selected blocks of 2, 4, or 6 patients. |

| Participants | Patients greater than or equal to 21 years of age with one sign or symptom of HF exacerbation and that have evidence of left ventricular systolic or diastolic dysfunction by echocardiogram, cardiac catheterization, or radionuclide imaging. Patients were NYHS class II, III, or IV at time of enrolment. Enrolment occurred during patient index hospitalization or just after discharge. |

| Interventions | Treatment: usual care plus enrolment in the disease management program. Study nurses provided additional education by telephone. Twenty patients received one or more home visits. Patients were called within 3 days after hospital discharge or study enrolment and then at least once a week for 2 weeks. Thereafter, the program nurses adjusted call frequency based on clinical status and self-management abilities. Patients were also given regularly scheduled telephonic monitoring by specially-trained nurses. Program components: self-management skills, diet counselling, and adherence to prescribed therapy. Usual care provided by their primary physician. Patients received education packages describing the causes of HF, principles of treatment, patient role in care and monitoring, and strategies for managing HF exacerbations. |

| Outcomes | Primary: Time to hospital readmission or emergency department visit (any cause). Other outcomes included time to all cause hospital readmission and time to HF-specific readmission, mortality, change in NYHA class, changes in quality of life and functional status outcomes as measures, total number of hospital encounters, hospital readmissions and hospital days and the cost of inpatient care during the follow-up period. |

| Notes | Sample size: study was designed to detect a 10% difference in readmission rates with an alpha of 0.05, and power of 80% and assuming a baseline readmission rate of 25% |

| Allocation Concealment | Not described |

| GESICA 2005 | |

| Methods | Multi-centre RCT comparing centralized telephone intervention with usual care. |

| Participants | Persons with HF who are in ambulatory care defined as no admissions in the previous 2 months, not needing more than 1 clinic visit per month, and on optimal HF treatment not modified for at least 2 months before enrolment. |

| Interventions | Treatment group received an education booklet. Nurses trained in the management of HF made frequent telephone follow-up calls to educate and monitor patients. Components of the program: adherence to diet and drug treatment, monitoring of symptoms, control of signs of hydrosaline retention, and daily physical activity. Nurses could adjust the dose of diuretic or recommend non-schedules medical or emergency visits. Usual care: provided by cardiologist. |

| Outcomes | Primary end-point was all cause mortality or admission to hospital for worsening HF. Secondary end-points included total mortality, all cause hospital admission, admission for worsening HF, cardiovascular admission, quality of life, all cause mortality or overall admissions and combined end-point of all cause mortality or cardiovascular admission. |

| Notes | Clinical events committee was blinded to the patient groups and adjudicated all outcomes. |

| Allocation Concealment | Concealed randomization lists used |

| MEJHERT 2004 | |

| Methods | Randomized prospective study of patients hospitalized with HF. |

| Participants | Persons 60 years of age and older with a NYHA class II-IV and left ventricular systolic dysfunction by echocardiology. Persons with an acute myocardial infarction or unstable angina pectoris within the previous three months, valvular stenosis, dementia, or a severe concomitant disease were excluded. |

| Interventions | Intervention: nurse monitored management programmed supervised by a senior cardiologist in an outpatient clinic. Regular visits were made to the clinic to meet with the nurse and at 6, 12, and 18 months to meet with the cardiologist for clinical examinations. Program components: Medication titration, disease-specific education (signs and symptoms of early deterioration), advice on diet (sodium, fluid, and alcohol intake). Education booklets and computerized education programs were also used. Usual Care group: persons in this group were managed by primary care physician. |

| Outcomes | Primary end-point was quality of life. Secondary end-points included function, medication, hospitalization and mortality. |

| Notes | None |

| Allocation Concealment | Allocation concealment methods not reported |

| RAO 2007 | |

| Methods | A prospective randomized trial. |

| Participants | Patients with suspected HF from either a primary care of secondary care setting. Newly Diagnosed HF patients |

| Interventions | Patients were randomized by age and sex to either specialist care or care provided by their general practitioner using a random number schedule. Persons randomized to specialist care were managed in a dedicated HF clinic by a cardiology registrar and a HF nurse either in the community or in a hospital. HF nurses in the specialist care group titrated medication to maximum tolerated dosage and provided HF disease-specific education. An information booklet was also provided. Program components: titration of medication and disease-specific education. Patients were encouraged to keep a symptom diary. Usual care was by patients’ general practitioners in primary care. |

| Outcomes | The primary outcome was prescription of optimum medication for HF. Definitions for optimal medication were provided by the authors. Secondary end-points were a composite of death and/or hospital admission for any reason. Also reported were hospital admission for worsening HF and number of days in hospital. |

| Notes | Treatment group (cardiologist and HF nurse in HF clinic): n=59 Control group (general practitioner) n=53 Sample size: Alpha of 0.05, power of 80% for a 25% reduction in death/readmission from 50% to 25%. Analysis was by intention to treat. No losses to follow-up Nineteen patients crossed-over between the groups. Ten patients randomized to usual care were referred to the cardiologist and nine patients randomized to specialist care requested follow-up by their general practitioner. |

| Allocation Concealment | Adequate |

| STROMBERG 2003 | |

| Methods | Prospective randomized study with a 12 month follow-up |

| Participants | Persons hospitalized due to HF having a NYHA class II-IV. Inclusion criteria were diagnosed HF either by echocardiography, radiographic evidence of pulmonary congestion, or typical symptoms and signs of HF. |

| Interventions | Treatment group: nurse led HF clinic staffed by experienced cardiac nurses. Nurses had delegated responsibility for making protocol led changes in medications. Program was initiated 2-3 weeks after discharge. Patients remained in the care of the HF clinic until they were stable. Thereafter, care responsibility returned to the primary health care practitioner. Program components: Disease education (signs and symptoms), medication titration, diet counselling, lifestyle changes (smoking), exercise advice. Usual Care group: conventional follow-up in primary health care. No specialized HF nurses, no standardized education or structured follow-up for patients with HF was provided. |

| Outcomes | Outcomes were assessed by a nurse blinded to the intervention and not involved in the care of the patient. The primary end-point was all cause mortality or all cause hospital admission after 12 months. Secondary end-points were mortality, number of readmissions for any reason, number of days in the hospital, and self-care behaviour. |

| Notes | Sample size was predicated on a 50% difference in the total rate of readmission or death between the groups with a 25% event-free survival in the control group [alpha of 0.05 (2-sided) and power of 80%]. |

| Allocation Concealment | Randomization was blinded and used a computer-generated list of random numbers and sealed envelopes. |

| WIERZCHOWIECKI 2006 | |

| Methods | RCT to determine the influence of a 1-year SMCC program for persons with CHF. |

| Participants | Hospitalized persons diagnosed with congestive heart failure (CHF) and on optimal medical treatment. |

| Interventions | Participation between a cardiologist, HF nurse, physiotherapist and a psychologist in a HF clinic. The intervention was initiated 14 days after discharge from hospital and continued at 1,3,6, and 12 months post discharge. Follow-up visits included consultation with the cardiologist, HF nurse, physiotherapist and the psychologist. For patients with advanced HF who were unable to come to the HF clinic, the HF nurse arranged a home visit. Components of the program included: medication titration, disease specific education, dietary advice, and lifestyle advice. Patient diaries were also used for data collection and a patient brochure on HF was provided. Telephone counselling by nurse was also available to HF patients. The primary care physician cared for the patient between visits to the clinic. Usual care: by primary care physician only |

| Outcomes | Mortality, frequency of readmissions, length of hospital stays during readmission, quality of life, and level of self care. |

| Notes | A physiotherapist set up exercise rehabilitation programs, teaching and monitoring exercise. A psychologist presented advice on how to cope with the disease and performed psychotherapy on persons with a high level of trait anxiety. |

| Allocation Concealment | Unclear |

Appendix 3: GRADE Evidence Profiles

| Quality assessment | Summary of findings | Importance | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No of patients | Effect | Quality | ||||||||||

| No of studies | Design | Limitations | Inconsistency | Indirectness | Imprecision | Other | Specialized Multidiscip. Care |

Usual Care | Relative (95% CI) | Absolute | ||

| All Cause Mortality | ||||||||||||

| 8 | RCTs | no serious limitations |

no serious inconsistency |

serious | no serious imprecision |

none | 223/1453 (15.3%) |

259/1344 (19.3%) |

RR 0.71 (0.56 to 0.91) |

56 fewer per 1000 (from 17 fewer to 85 fewer) |

⊕⊕⊕Ο MODERATE |

CRITICAL |

| All Cause Mortality Direct Team Care | ||||||||||||

| 6 | RCTs | no serious limitations |

no serious inconsistency |

serious1 | no serious imprecision |

none | 94/617 (15.2%) |

126/511 (24.7%) | RR 0.60 (0.47 to 0.76) | 99 fewer per 1000 (from 59 fewer to 131 fewer) | ⊕⊕⊕Ο MODERATE |

CRITICAL |

| All Cause Mortality Indirect Team Care | ||||||||||||

| 2 | RCTs | no serious limitations |

no serious inconsistency |

serious2 | serious3 | none | 129/836 (15.4%) | 133/833 (16%) | RR 0.97 (0.77 to 1.21) | 5 fewer per 1000 (from 37 fewer to 34 more) | ⊕⊕ΟΟ LOW |

CRITICAL |

| All Cause Mortality SMCC vs. PCP | ||||||||||||

| 6 | RCTs | no serious limitations |

no serious inconsistency |

serious4 | no serious imprecision |

none | 95/575 (16.5%) |

114/464 (24.6%) |

RR 0.65 (0.51 to 0.84) |

86 fewer per 1000 (from 39 fewer to 120 fewer) | ⊕⊕⊕Ο MODERATE |

CRITICAL |

| All Cause mortality SMCC vs. Cardiologist | ||||||||||||

| 2 | RCTs | no serious limitations |

no serious inconsistency |

serious5 | serious6 | none | 128/878 (14.6%) |

145/880 (16.5%) |

RR 0.78 (0.46 to 1.32) |

36 fewer per 1000 (from 89 fewer to 53 more) | ⊕⊕ΟΟ LOW |

CRITICAL |

| HF-Specific Mortality | ||||||||||||

| 3 | RCTs | no serious limitations |

no serious inconsistency |

serious7 | no serious imprecision |

none | 195/892 (21.9%) |

258/892 (28.9%) |

RR 0.58 (0.32 to 1.05) |

121 fewer per 1000 (from 197 fewer to 14 more) | ⊕⊕⊕Ο MODERATE |

IMPORTANT |

| HF-Specific Mortality Direct Team Care | ||||||||||||

| 2 | RCTs | no serious limitations |

no serious inconsistency |

serious8 | serious9 | none | 12/132 (9.1%) |

30/134 (22.4%) |

RR 0.42 (0.21 to 0.83) |

130 fewer per 1000 (from 38 fewer to 177 fewer) | ⊕⊕ΟΟ LOW |

IMPORTANT |

| HF-Specific Mortality Indirect Team Care | ||||||||||||

| 1 | RCTs | no serious limitations |

no serious inconsistency |

serious10 | serious11 | none | 183/760 (24.1%) |

228/758 (30.1%) |

RR 0.80 (0.68 to 0.95) |

60 fewer per 1000 (from 15 fewer to 96 fewer) | ⊕⊕ΟΟ LOW |

IMPORTANT |

| HF-Specific Mortality SMCC vs. PCP | ||||||||||||

| 2 | RCTs | no serious limitations |

no serious inconsistency |

serious8 | serious9 | none | 12/132 (9.1%) |

30/134 (22.4%) |

RR 0.42 (0.21 to 0.83) |

130 fewer per 1000 (from 38 fewer to 177 fewer) | ⊕⊕ΟΟ LOW |

IMPORTANT |

| HF-Specific Mortality SMCC vs. Cardiologist | ||||||||||||

| 1 | RCTs | no serious limitations | no serious inconsistency | serious10 | serious11 | none | 183/760 (24.1%) |

228/758 (30.1%) |

RR 0.80 (0.68 to 0.95) |

60 fewer per 1000 (from 15 fewer to 96 fewer) | ⊕⊕ΟΟ LOW |

IMPORTANT |

| All Cause Hospitalization | ||||||||||||

| 7 | RCTS | no serious limitations |

serious12 | serious13 | no serious imprecision |

none | 527/1175 (44.9%) |

564/1222 (46.2%) |

RR 1.12 (0.92 to 1.35) |

55 more per 1000 (from 37 fewer to 162 more) | ⊕⊕ΟΟ LOW |

IMPORTANT |

| All Cause Hospitalization Direct Team Care | ||||||||||||

| 5 | RCTs | no serious limitations |

serious14 | serious15 | no serious imprecision |

none | 194/287 (67.6%) |

193/335 (57.6%) |

RR 1.31 (0.94 to 1.82) |

179 more per 1000 (from 35 fewer to 472 more) | ⊕⊕ΟΟ LOW |

IMPORTANT |

| All Cause Hospitalization Indirect Team Care | ||||||||||||

| 2 | RCTs | no serious limitations |

no serious inconsistency |

serious16 | no serious imprecision |

none | 311/836 (37.2%) |

351/833 (42.1%) |

RR 0.88 (0.79 to 0.99) |

51 fewer per 1000 (from 4 fewer to 88 fewer) | ⊕⊕⊕Ο MODERATE |

IMPORTANT |

| All Cause Hospitalization SMCC vs. PCP | ||||||||||||

| 6 | RCTs | no serious limitations |

serious17 | serious18 | no serious imprecision |

none | 266/415 (64.1%) |

268/464 (57.8%) |

RR 1.19 (0.94 to 1.49) |

110 more per 1000 (from 35 fewer to 283 more) | ⊕⊕ΟΟ LOW |

IMPORTANT |

| All Cause Hospitalization SMCC vs. Cardiologist | ||||||||||||

| 1 | RCTs | no serious limitations |

no serious inconsistency |

serious10 | serious11 | none | 261/760 (34.3%) |

296/758 (39.1%) |

RR 0.88 (0.77 to 1) |

47 fewer per 1000 (from 90 fewer to 0 more) | ⊕⊕ΟΟ LOW |

IMPORTANT |

| HF-Specific Hospitalization | ||||||||||||

| 6 | RCTs | no serious limitations |

serious19 | serious20 | no serious imprecision |

none | 216/1197 (18%) |

266/1185 (22.4%) |

RR 0.86 (0.62 to 1.19) | 31 fewer per 1000 (from 85 fewer to 43 more) | ⊕⊕ΟΟ LOW |

IMPORTANT |

| HF-Specific Hospitalization Direct Team care | ||||||||||||

| 4 | RCTs | no serious limitations |

serious21 | serious20 | no serious imprecision |

none | 61/361 (16.9%) |

60/352 (17%) |

RR 1.07 (0.52 to 2.19) |

12 more per 1000 (from 82 fewer to 203 more) | ⊕⊕ΟΟ LOW |

IMPORTANT |

| HF-Specific Hospitalization Indirect Team Care | ||||||||||||

| 2 | RCTs | no serious limitations |

no serious inconsistency |

serious16 | no serious imprecision |

none | 156/836 (18.7%) |

206/833 (24.7%) |

RR 0.75 (0.62 to 0.9) |

62 fewer per 1000 (from 25 fewer to 94 fewer) | ⊕⊕⊕Ο MODERATE |

IMPORTANT |

| HF-Specific Hospitalization SMCC vs. PCP | ||||||||||||

| 4 | RCTs | no serious limitations |

no serious inconsistency22 |

serious23 | no serious imprecision |

none | 64/315 (20.3%) |

86/305 (28.2%) |

RR 0.73 (0.55 to 0.96) |

76 fewer per 1000 (from 11 fewer to 127 fewer) | ⊕⊕⊕Ο MODERATE |

IMPORTANT |

| HF-Specific Hospitalization SMCC vs. Cardiologist | ||||||||||||

| 2 | RCTs | no serious limitations |

serious24 | serious25 | serious26 | none | 152/882 (17.2%) |

180/880 (20.5%) |

RR 1.22 (0.43 to 3.45) |

45 more per 1000 (from 117 fewer to 501 more) | ⊕ΟΟΟ VERY LOW |

IMPORTANT |

1 study completed in New Zealand, 1 in Netherlands, 2 in Sweden, 1 in the United Kingdom and 1 study in Poland

1 study completed in Argentina and 1 study completed in the USA

Predominately one large study contributing to the estimate of effect

2 studies completed in Sweden, 1 in New Zealand, 1 in the United Kingdom, 1 in Poland and 1 in the USA

1 study completed in The Netherlands and 1 in Argentina

1 large study contributing 77% to the estimate of the effect

1 study from Argentina, 1 from Sweden, and one from Poland

1 study from Poland and one from Sweden

Sample size of both studies small

Study completed in Argentina

Only 1 study contributing to estimate of effect

Inconsistency in direction of effect, confidence intervals do not over lap, magnitude of effect ranges from RR of 0.90 to 2.01

Studies completed in New Zealand, USA, Argentina, 2 in Sweden, UK, and Poland

Studies vary in direction of effect and magnitude of effect ranges from a RR of 1.01 to 2.01, confidence intervals do not overlap

Studies completed in New Zealand, Sweden, UK and Poland

Studies completed in Argentina and USA

Estimates of effect vary in direction, size and confidence intervals do not overlap

Studies from New Zealand, USA, Sweden (2), UK and Poland

Studies vary in size and direction of effect. RR ranges from 0.52 to 2.18

Studies from The Netherlands, New Zealand, USA, Argentina, UK and Poland

Inconsistency in magnitude and direction of effect. RR ranges from 0.52 to 2.67

This evidence was not downgraded for inconsistency because there was only one small study contributing to 2.8% of effect size with a RR of 2.69, which is opposite in direction and magnitude of effect to the other 3 studies in the evidence profile.

Studies from Poland, UK, US and New Zealand

Magnitude and direction of studies differ, confidence intervals do not overlap

Studies completed in The Netherlands and Argentina

One large study contributing approximately 73% to the effect size

Suggested Citation

This report should be cited as follows:

Medical Advisory Secretariat. Community-based care for the specialized management of heart failure: an evidence-based analysis. Ontario Health Technology Assessment Series 2009;9(17).

Permission Requests

All inquiries regarding permission to reproduce any content in the Ontario Health Technology Assessment Series should be directed to MASinfo.moh@ontario.ca.

How to Obtain Issues in the Ontario Health Technology Assessment Series

All reports in the Ontario Health Technology Assessment Series are freely available in PDF format at the following URL: www.health.gov.on.ca/ohtas.

Print copies can be obtained by contacting MASinfo.moh@ontario.ca.

Conflict of Interest Statement

All analyses in the Ontario Health Technology Assessment Series are impartial and subject to a systematic evidence-based assessment process. There are no competing interests or conflicts of interest to declare.

Peer Review

All Medical Advisory Secretariat analyses are subject to external expert peer review. Additionally, the public consultation process is also available to individuals wishing to comment on an analysis prior to finalization. For more information, please visit http://www.health.gov.on.ca/english/providers/program/ohtac/public_engage_overview.html.

Contact Information

The Medical Advisory Secretariat

Ministry of Health and Long-Term Care

20 Dundas Street West, 10th floor

Toronto, Ontario

CANADA

M5G 2C2

Email: MASinfo.moh@ontario.ca

Telephone: 416-314-1092

ISSN 1915-7398 (Online)

ISBN 978-1-4435-0390-7 (PDF)

About the Medical Advisory Secretariat

The Medical Advisory Secretariat is part of the Ontario Ministry of Health and Long-Term Care. The mandate of the Medical Advisory Secretariat is to provide evidence-based policy advice on the coordinated uptake of health services and new health technologies in Ontario to the Ministry of Health and Long-Term Care and to the healthcare system. The aim is to ensure that residents of Ontario have access to the best available new health technologies that will improve patient outcomes.

The Medical Advisory Secretariat also provides a secretariat function and evidence-based health technology policy analysis for review by the Ontario Health Technology Advisory Committee (OHTAC).

The Medical Advisory Secretariat conducts systematic reviews of scientific evidence and consultations with experts in the health care services community to produce the Ontario Health Technology Assessment Series.

About the Ontario Health Technology Assessment Series

To conduct its comprehensive analyses, the Medical Advisory Secretariat systematically reviews available scientific literature, collaborates with partners across relevant government branches, and consults with clinical and other external experts and manufacturers, and solicits any necessary advice to gather information. The Medical Advisory Secretariat makes every effort to ensure that all relevant research, nationally and internationally, is included in the systematic literature reviews conducted.

The information gathered is the foundation of the evidence to determine if a technology is effective and safe for use in a particular clinical population or setting. Information is collected to understand how a new technology fits within current practice and treatment alternatives. Details of the technology’s diffusion into current practice and input from practising medical experts and industry add important information to the review of the provision and delivery of the health technology in Ontario. Information concerning the health benefits; economic and human resources; and ethical, regulatory, social and legal issues relating to the technology assist policy makers to make timely and relevant decisions to optimize patient outcomes.

If you are aware of any current additional evidence to inform an existing evidence-based analysis, please contact the Medical Advisory Secretariat: MASinfo.moh@ontario.ca. The public consultation process is also available to individuals wishing to comment on an analysis prior to publication. For more information, please visit http://www.health.gov.on.ca/english/providers/program/ohtac/public_engage_overview.html.

Disclaimer