Abstract

The authors’ objective was to gain a better understanding of minority patients’ beliefs about hypertension and to use this understanding to develop a model to explain gaps in communication between patients and clinicians. Eighty‐eight hypertensive black and Latino adults from 4 inner‐city primary care clinics participated in focus groups to elucidate views on hypertension. Participants believed that hypertension was a serious illness in need of treatment. Participants’ diverged from the medical model in their beliefs about the time‐course of hypertension (believed hypertension was intermittent); causes of hypertension (believed stress, racism, pollution, and poverty were the important causes); symptoms of hypertension (believed hypertension was primarily present when symptomatic); and treatments for hypertension (preferred alternative treatments that reduced stress over prescription medications). Participants distrusted clinicians who prioritized medications that did not directly address their understanding of the causes or symptoms of hypertension. Patients’ models of understanding chronic asymptomatic illnesses such as hypertension challenge the legitimacy of lifelong, pill‐centered treatment. Listening to patients’ beliefs about hypertension may increase trust, improve communication, and encourage better self‐management of hypertension.

While rates of blood pressure (BP) control in the United States have improved in recent years, half of hypertensive Americans continue to have their BP above the goals set by established guidelines and one third remain uncontrolled despite treatment. 1 One major reason for the high rate of uncontrolled hypertension is suboptimal self‐management. An estimated half of hypertensive individuals do not adequately comply with medication treatment and even fewer comply with other lifestyle behaviors recommended to control hypertension. 2

Health care providers play an important role in helping patients self‐manage their hypertension. 3 Clinicians, for example, can improve adherence to antihypertensive medications by prescribing simpler medication regimens. 4 Clinicians can also positively impact patients’ self‐management through patient‐centered counseling. 5 Unfortunately, clinician‐based interventions to educate and motivate patients to improve their adherence to BP medications have, thus far, been unsuccessful. 6 , 7

One possible reason for the lack of effectiveness of clinician counseling may be a lack of understanding of the patient perspective toward hypertension. In particular, clinicians may not understand how patients’ experience living with hypertension influences their beliefs about the illness. The gap in understanding between clinicians’ and the patients’ beliefs about hypertension may be especially large when involving patients from disadvantaged minority patients groups. Beliefs about hypertension treatment have been associated with adherence to treatment in prior studies. 8

To elucidate minority patient’s beliefs about hypertension, we conducted focus groups with African American and Latino hypertensive adults. We also chose to focus on minority patients because rates of uncontrolled BP control, despite being prescribed treatment, are disproportionately high in these groups. 1 , 9 , 10 We triangulated the findings from these groups with information from the medical literature to develop a model for how laypeople understand this largely asymptomatic, life‐long condition.

Methods

Participants

Recruitment procedures are detailed elsewhere. 11 Briefly, potentially eligible participants were identified by screening medical records from 4 hospital‐affiliated clinics in East and Central Harlem and by encouraging physicians at these clinics to directly refer their hypertensive patients to the study. Among the subset of patients in whom screening was tracked, 57% of screened patients agreed to participate and common reasons for refusal included feeling too ill or scheduling conflicts. Participants were eligible if they were African American or Latino and aged 18 years or older and if they had antihypertensive medications listed in their medical record or were identified as hypertensive by their primary clinician.

Data Collection

Nine focus groups took place between May 2001 and April 2002. We chose focus groups for our methodology because qualitative research is helpful for generating new hypotheses regarding a phenomenon.12 Groups were stratified according to race/ethnicity (African American/Latino) and language (English or Spanish). Assembling groups of individuals with a homogeneous condition and race or ethnicity is especially useful for promoting sharing, expanding, and contrasting of experiences, attitudes, and ideas, particularly among persons who have been historically underserved and underevaluated. 13

Each session took 90 minutes and involved 8 to 10 participants. Groups included a trained moderator and an observer who recorded field notes. The moderator facilitated the groups with the help of a structured interview guide that was designed to explore patients’ knowledge and attitudes about BP, attitudes toward health care providers, behaviors concerning controlling BP, and barriers to controlling BP. Participants completed a brief demographic survey at the end of each session and received a cash stipend for attending. All sessions were audiotaped and transcribed. Transcripts of focus groups that took place in Spanish were translated into English. The institutional review boards of each hospital from which patients were recruited (Mount Sinai Medical Center, Metropolitan Hospital, Harlem Hospital, and North General Hospital) approved all study procedures and all participants provided written informed consent.

Qualitative Analysis

Two investigators read 4 random transcripts and associated field notes to generate a preliminary list of 40 codes. The same 2 investigators then used these codes to independently code one transcript using the qualitative analysis software program Atlas.ti, version 4.2. (Berlin, Scientific Sofware Development, 1999). The preliminary code list was then refined through consensus. The same 2 investigators then applied these revised codes to 2 additional focus group transcripts and used the results to come to a final consensus on 48 codes with specified definitions. Examples of codes were the terms “adherence,”“barriers to treatment,”“causes of hypertension,”“communication,” and “racism.” These final codes were then used to analyze transcripts from all 9 focus groups. Interrater reliablilty using these final codes was more than 90%. Once all transcripts were coded, investigators developed a list of 6 dominant themes that emerged from the analysis. The investigators then merged the codes into these overriding themes, which are described in the Results section.

Results

Participants

Eighty‐eight hypertensive adults attended 1 of 9 focus groups (4 African American and 5 Latino groups, 2 of the Latino groups in Spanish) with 8 to 12 participants per group; 98% completed a demographic survey (Table I). The majority of participants were women, one third were 65 years or older, and most (55%) had Medicaid and lived in poverty. Most patients had hypertension for more than 10 years and most (64%) of the 73% in whom clinical BP data were available had uncontrolled hypertension (≥140/90 mm Hg).

Table I.

Characteristics of Focus Group Participants (N=88)a

| Characteristic | Prevalence, % |

|---|---|

| Age ≥65 y | 34 |

| Women | 77 |

| Race/ethnicity | |

| African American | 53 |

| Latino | 47 |

| No health insurance | 5 |

| Annual household income <$15,000 | 75 |

| Uncontrolled hypertension (≥140/90 mm Hg)b | 46 |

aBased on 86 surveys; 2 participants did not complete a demographic survey. bBased on 64 participants who had their blood pressure measured by study personnel.

Beliefs About Seriousness of Hypertension

Participants generally believed that hypertension was a serious illness. Having untreated hypertension was referred to as housing a “ticking time bomb.” Medical facts that could better define the condition of high BP, such as what pressures were too high and how much variability in pressure was acceptable, were rarely mentioned.

Beliefs About Causes of Hypertension

For both African Americans and Latinos, hypertension was triggered by or fluctuated with stress. One Latina said, “I have noticed that the high BP is all mental.” Interestingly, many related situations in which clinicians reinforced this stress model of hypertension by telling them their BP was elevated because they were rushing or upset or by asking them to relax in a quiet room and then measuring a lower BP on a recheck. Those few participants who described how medicines worked said they calmed their nerves.

While the view of hypertension as linked to stress seemed natural to many participants, medical causes often ran contrary to participants’ experiences. For example, many respondents said they were healthier before they moved to New York City and modified their health habits to meet their doctors’ expectations. One black man noted, “[…salting foods]—I don’t think that plays no part in your BP. Matter of fact, that might have been helping you, because you didn’t have it back then.”

African Americans often discussed how hypertension was caused by social conditions such as poverty, pollution, racism, and stress. Echoing the statements of others in her group, a black woman said hypertension among people of color was caused by “generations of hardship.” A different black woman said: “The hypertension would be when you said the [colleague] look right through you. So natural, you would have hypertension because you’re angry… it is an anger, as I said, as African Americans we grow up with it.”

Beliefs About Symptoms of Hypertension

Many said they could determine when their BPs were elevated based on intermittent somatic symptoms such as headaches and dizziness. Few believed they had high BP between these visceral episodes. Symptom relief was proof of a pill’s effectiveness, reinforcing the perception of hypertension as transient phenomena. Those who did not link their hypertension to symptoms had difficulty in reifying a condition without any sensation or discrete physical location. An elderly black woman said: “How do you know? I don’t have any particular a feeling to know that. You put this thing on your arm and they say: ‘That means your pressure.’ I don’t feel giddy. I don’t feel anything at all. I’m still in the dark.”

Beliefs About Medications and Alternative Treatments

Participants’ concept of hypertension as acute and episodic led to doubts that it was necessary to take daily medications. A black woman said: “That’s where I get confused with the doctors. If you go to your doctor and your BP is normal, why they don’t reduce your medication?” Doctors’ expectation for patients to take medications on an ongoing basis appeared to contradict doctors’ statements that BPs were “controlled.”

Participants described multiple concerns with taking medications every day including side effects and worries about becoming dependent on chemicals that were not “natural.” One participant related:

He [the doctor] says, well, you’ve got to live with some of the side effects, which I don’t think I have to. But until we learn how to deal with the elements that are causing these things, nothing’s going to happen—we’re going to continue to be taking these pills…I don’t agree with what we’re doing.

Beliefs that hypertension was caused by social factors rather than biological or lifestyle factors fostered distrust of medications. The introductory statement of a black woman was:

I feel that society, our way of life, is what’s causing us to have all these things. Our food, our water, our air... Because everybody’s got the same thing—how can everybody have the same thing? So, therefore, the medicine is not curing us, taking it away. It’s making it worse!

Additional barriers to taking conventional medications included fears of medical experimentation, of being treated “generically” with generic drugs, and concerns that the medications would do more harm than good. A black man said, “Any pill we take kills something else in our body.” Cost was another common barrier. Medications could cost “more than a T.V.” A black man from another group explained: “You give me all the diagnoses, but the final thing is I can’t buy the medication.” Despite these concerns, most participants described medications as a mainstay of treatment and took medication at least part of the time.

In contrast, home remedies were considered familiar, safe, and addressed beliefs that hypertension was caused by stress. Some participants simply relaxed, just as clinicians instructed them to do in their offices. Others used strategies to “cool down” to lower BP. One Spanish‐speaking woman said, “When I have high BP, I get nervous…I will place ice on my head.” Latino participants described BP lowering through placing one’s body in contact with a cool floor. Rather than challenging the benefits of this therapy, the group discussed ways a cold floor could be used most effectively.

A: This is what you do…you sit and get the cold from the feet. You don’t have to walk.

B: You don’t need to stand?

C: Yes, you can be seated…the body will receive the cold and you become calm.

Black participants also discussed how using alternative remedies bypassed profit‐driven physicians whom they distrusted and perceived as automatically dispensing costly pills.

Beliefs About Health Care Providers and the Health Care System

Many participants said hypertension could not be treated without a doctor‐patient relationship grounded in trust and respect. A doctor’s bedside manner could lead to confidence and comfort, which, in turn, reduce BP. One elderly black man responded to the question of how he controlled his BP with the following answer:

Well, I think part of that is the doctor that you get, or doctor that get you. It’s the way that he talks to you and treat you that makes you have confidence in him. Now another doctor may give and do the same thing, but he don’t, you know, like soothes you. [Others mutter agreements.]

Conversely, a Latina woman said, “I told my coworker, ‘I don’t trust this doctor and I am not going to benefit from the medications.’ ” A Latino man further explained the perceived hazards of dysfunctional health provider relationships: “Maybe the nurse wants to talk to me with good intentions but there’s confrontation and our BP goes up.”

Some participants described clinicians as not meeting their needs, not treating them as individuals, and not providing adequate follow‐up. Several stated that doctors “intimidate people, especially the elderly.” Others thought doctors marginalized them, “treat people like if you a dummy, like you don’t know nothing, you don’t have a right to ask questions,” or say, “I am the doctor and you’re just the patient.” Many participants said they felt intimidated by their providers, stating that they would not ask questions or disagree with doctors to avoid angering or turning them off. A Spanish‐speaking woman said, “We did not keep talking because he cut me off. After, I did not ask him any questions.” Both Latinos and blacks felt doctors stereotyped their eating habits and their likelihood of taking therapies based on race or ethnicity.

Frustration with health care extended beyond individual physicians to the entire medical establishment. Doctors were trained and the system geared to treat patients through dispensing pills, which simplified their work, enhanced productivity, and increased profit margins at the expense of patients. A black woman excused doctors, saying: “You can’t blame the doctors… The doctors givin’ you the pills that the pharmaceuticals are making…The doctor’s only doin’ what he been trained to do.” The following discussion ensued among 3 black men:

A: And if the Chinese can cure hypertension, can they? Why can’t Americans?

B: Big business.

A: They in business. That’s all it’s about. Big business.

C: Yeah, they’re getting over like a fat rat.

A: And if they cure you, you ain’t got to come back. So that’s revenue he lose.

Suggestions for Improving Hypertension Care

Participants suggested several ways to improve care for hypertension. First, many wanted to have their BPs checked more often, either at more frequent clinic visits or through home monitoring. Interestingly, participants expected increased monitoring to verify that their BPs were elevated only episodically and that they would not need BP pills all the time. Second, participants recommended investing time into building trust in the patient‐health provider relationships. A Latino man said: “The most important thing is to know what’s going on, to assure the actual person. First look for comprehension, not confrontation.” Third, participants said that doctors should praise patients more often, as this would help instill pride in the measures they took to successfully control their own BPs. A black woman said: “[the doctor]…should compliment you. ‘Cause I think that would push us in the right direction too, to have somebody say, “Oh, you’re taking your medication, you’re doing good. It’s now 110/60, you know.”

Discussion

We conducted focus groups with black and Latino hypertensive adults to deepen the understanding of patient‐level barriers to optimal hypertension care. These adults agreed with their diagnosis of hypertension and generally believed that hypertension represented a serious health problem. However, in contrast with the typical health professional’s model, most believed this condition was episodic rather than chronic, and that it was caused, exacerbated, and evidenced by symptoms often associated with stress, racism, pollution, and poverty. Stress and emotional factors have been viewed as major causes of hypertension by lay people in prior studies of beliefs about hypertension. 14 , 15 , 16 , 17

Many participants preferred alternative remedies that directly induced cooling or calm (a goal some clinicians seemed to ratify) as these treatments logically addressed the triggers and symptoms of hypertension. Conversely, participants had trouble justifying taking daily prescription medications that did not target the etiologies of hypertension. Decisions to take medications were further influenced by perceptions that cost and side effects of medications outweighed their usefulness. This lack of congruence between the causes and treatments for hypertension fostered distrust in the patient‐doctor relationship and, as has been found in a prior study, engendered feelings of conspiracy by the health care system (Table II). 15

Table II.

Common Beliefs Associated With Dissatisfaction With Hypertension Care

| Hypertension is caused by social inequities, stress, or other psychological factors |

| Hypertension causes episodic symptoms such as headaches and dizziness |

| Medications are unnatural, addictive, and can damage the body |

| Health care providers stereotype patients and treat them generically rather than tailoring their management to the individual |

| Doctors and the health care system are motivated by financial incentives rather than altruism |

African Americans and Latinos held similar beliefs about the symptomatic, stress‐related nature of hypertension. However, blacks more commonly attributed stress to social inequity and racism, whereas Latinos were more likely to describe stress as a natural part of their everyday lives. Accordingly, blacks were more likely to distrust clinicians and prescription medications, whereas Latinos were more likely to have faith in traditional remedies that had calming effects on stress.

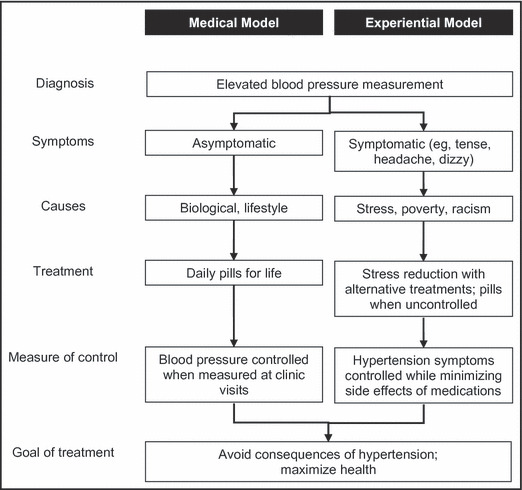

The Figure depicts a model for understanding gaps in communication about hypertension between clinicians and patients. This model includes two pathways: (1) a medical pathway (widely held by clinicians), and (2) an experiential pathway that relies on the experience of living with hypertension (widely held by participants in these focus groups). Those who ascribe to both models agree on the seriousness of the diagnosis of hypertension, that hypertension can lead to adverse health outcomes, and that the long‐term goal is to avoid these bad outcomes. However, the two paths diverge when moving from diagnosis to treatment. On the medical pathway, individuals see hypertension as a chronic, often symptom‐free condition that is mediated by biological and behavioral factors and that is best treated with daily pills for life. On the experiential pathway, individuals see hypertension as a symptomatic and stress‐related condition that is best treated episodically with pills during flares or alternative remedies that directly address the physical symptoms they link to hypertension or that address the underlying problem of stress. The precise beliefs underlying the causes and solutions to stress underlying hypertension differ according to individual patients’ personal and sociocultural context. Hence, African Americans are more likely to point to issues relating to racism and discrimination and Latinos are more likely to point to alternative remedies passed on through their families and available in local botanicas.

Figure FIGURE.

Conceptual models for typical health providers’ medical model and hypertensive patient’s experiential model of hypertension. In the medical model and experiential model, providers and patients agree on diagnosis and have a goal to mitigate consequences of disease. However, the models diverge in their understanding of symptoms, causes, treatments, and measures of control.

Although we developed this model for understanding gaps in communication between patients and doctors by enrolling only black and Latinos from one underserved inner‐city community, there is evidence from other studies suggesting that similar models may apply to other communities. An anthropologic study of African Americans in the rural southern United States elucidated similar lay beliefs regarding the symptomatic nature and stress‐related etiology of hypertension as participants in our study. 17 Preference for alternative remedies and beliefs that hypertension is caused by stress and treatable with “cold” therapies has been previously noted in Latinos. 18 A survey of 189 patients and 45 primary care providers from Veterans Administration clinics revealed that almost all Veteran patients and physicians agreed on the seriousness of hypertension and the importance of controlling hypertension to prevent strokes and heart attacks. 19 But interestingly, 38% of physicians in this study felt that reducing strokes and heart attacks was not very important to their patients. This misunderstanding of patients’ goals may have resulted from clinicians’ misinterpreting nonadherence to prescribed medications as lack of concern in their patients; yet, based on our model, lack of adherence to pill‐based treatment may instead result from a different understanding of the causes and solutions, not the perceived seriousness. In another study of 46 patients, beliefs about hypertension were elicited among native Dutch and African immigrants to Holland. 20 Again, patients from all groups agreed with the concept that hypertension was a serious illness. The majority also believed that stress played a major role. Yet, the sources of stress and solutions to stress differed among the groups, with immigrants most likely to refer to difficulties with migrating and integrating into Dutch society as important factors.

The asymptomatic nature of hypertension is a key factor complicating communication about the disorder between patients and clinicians. Traditional behavioral theory states that symptoms are a primary reason people take action to control an illness. 22 Indeed, symptoms are the most common reason for initiating medical care and being healthy is often equated with being symptom‐free. 23 Interestingly, according to the experiential pathway, patients either ascribe symptoms to hypertension or are confused by its lack of symptoms. Yet, according to the medical pathway, hypertension infrequently has symptoms as cues to action. When patients perceive hypertension as asymptomatic, they need to take a leap of faith in heeding their doctor’s advice to take potentially noxious, costly, daily pills for years, especially when the effectiveness of this treatment is neither immediate nor guaranteed. Encounters where the doctor prioritizes their agenda to treat risk factors over the patients’ agenda to treat symptoms may damage the patient‐doctor relationship and hinder care.

Asymptomatic conditions are prevalent, and clinicians increasingly focus on screening for asymptomatic illnesses (ie, cancer screening) and on “virtual” problems that patients cannot feel or attribute to a specific body part, including hypertension and hyperlipidemia. 24 This focus on symptom‐free conditions is occurring despite mounting evidence that an inadequate focus on alleviating symptoms causes patients (and doctors) frustration and dissatisfaction. 25 As research expands, our capacity to identify biological markers that precede clinically apparent illnesses and the trend to treat markers, rather than symptoms, will likely continue. To date, there is too little research on patients’ views of asymptomatic conditions and their commitment to caring for them.

While the medical model discounts the ability of patients to experience symptoms from hypertension unless BP is extremely elevated, patients’ common‐sense model attributes episodic symptoms to hypertension and patients often take treatments episodically for these symptoms. Patients who believe they can monitor their pressure symptomatically may be more likely to stop medication treatment if the clinician does not address this belief. 20 In contrast, patients who believe BP medications have beneficial effects on their symptoms are more likely to comply with medications and to have their BP controlled. 26 There is a danger that doctors will foster distrust in their patients if they discount their patients’ experiences of these symptoms. In one study, patients with unexplained symptoms contrasted their own sensory and therefore infallible experience of symptoms, with doctors’ indirect and fallible knowledge. By providing explanations that devalued patients’ symptoms, doctors were perceived as incompetent and inexpert. 27 Recognition of these factors can be part of programs to improve BP control. 11 In one pilot study, when clinicians had greater sensitivity to patients’ beliefs about their hypertension, patients modified their beliefs and action plans to be more concordant with the medical model. 28 , 29

Limitations

There were several limitations to our findings. Focus groups were conducted in two adjacent urban neighborhoods and included a relatively small number of participants. However, this was a qualitative study that was designed to generate new hypotheses rather than to define the prevalence of beliefs in a population. Focus groups were limited to minority populations. Yet, many of the themes identified have also been found in nonminority populations, thus supporting the generalizability of the model to other populations. 30 , 31 Those who agreed to participate may not be representative of other members of their groups; however, more than 50% of those approached agreed to participate, and culturally competent recruiters were used to encourage participation by all potentially eligible participants.

Conclusions and Implications

There is a need for research that tests interventions addressing discordances between lay and clinical beliefs about asymptomatic conditions. Until that time, several strategies informed by our focus groups may prove beneficial. Clinicians could directly elicit patients’ views on hypertension and its treatment, especially when there appear to be problems with medication adherence or BP control. Rather than merely trying to correct discordant lay beliefs, clinicians might accommodate these beliefs. 32 Similarly, instead of disagreeing with patients’ use of alternative treatments for hypertension, clinicians might encourage the use of safe alternatives as compliments to medications and lifestyle modifications. Clinicians might validate the views of hypertensive patients who believe they can sense when their BP is high by agreeing that their BP rises from stress, but that their BP remains high even in lower‐stress situations like when waking up. Clinicians might encourage patients to use home BP monitors to test this point. Finally, clinicians should consider choosing regimens with a favorable patient‐centered risk‐benefit profile and praise patients when their BP is under control.

Acknowledgments

Acknowledgements and disclosures: We gratefully acknowledge Sheneta Latchoo, Desiree Maldonado, and Erica Spiegel for their help in arranging the focus groups and tabulating and collating the results. We also thank Mary Rojas for conducting some of the focus groups and we thank the focus group participants for sharing their ideas with us. Dr Kronish received support from the National Heart, Lung and Blood Institute (K23 HL098359). Dr Horowitz received support from the National Institute of Minority Health and Health Disparities (P60MD00270) and the National Center for Research Resources (UL1RR029887). The funders played no role in the study design, data collection, analysis or interpretation of data, or writing or submission of the manuscript.

References

- 1. Egan BM, Zhao Y, Axon RN. US trends in prevalence, awareness, treatment, and control of hypertension, 1988–2008. JAMA. 2000;303:2043–2050. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Vrijens B, Vincze G, Kristanto P, et al. Adherence to prescribed antihypertensive drug treatments: longitudinal study of electronically compiled dosing histories. BMJ. 2008;336:1114–1117. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Hill MN, Miller NH, DeGeest S. ASH position paper: adherence and persistence with taking medication to control high blood pressure. J Clin Hypertens (Greenwich). 2010;12:757–764. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Schroeder K, Fahey T, Ebrahim S. Interventions for improving adherence to treatment in patients with high blood pressure in ambulatory settings. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2004;4:CD004804. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Schoenthaler A, Chaplin WF, Allegrante JP, et al. Provider communication effects medication adherence in hypertensive African Americans. Patient Educ Couns. 2009;75:185–191. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. McDonald HP, Garg AX, Haynes RB. Interventions to enhance patient adherence to medication prescriptions: scientific review. JAMA. 2002;288:2868–2879. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Haynes RB, Ackloo E, Sahota N, et al. Interventions for enhancing medication adherence. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2008;2:CD000011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Ross S, Walker A, MacLeod MJ. Patient compliance in hypertension: role of illness perceptions and treatment beliefs. J Hum Hypertens. 2004;18:607–613. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Giles T, Aranda JM Jr, Suh DC, et al. Ethnic/racial variations in blood pressure awareness, treatment, and control. J Clin Hypertens (Greenwich). 2007;9:345–354. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Redmond N, Baer HJ, Hicks LS. Health behaviors and racial disparity in blood pressure control in the national health and nutrition examination survey. Hypertension. 2011;57:383–389. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Horowitz CR, Tuzzio L, Rojas M, et al. How do urban African Americans and Latinos view the influence of diet on hypertension? J Health Care Poor Underserved. 2004;15:631–644. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Lincoln YS. Cuba EG. Naturalistic Inquiry. Beverly Hills, CA: Sage Publications; 1985. [Google Scholar]

- 13. Folch‐Lyon E, Trost JF. Conducting focus group sessions. Stud Fam Plann. 1981;12:443–449. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Boutin‐Foster C, Ogedegbe G, Ravenell JE, et al. Ascribing meaning to hypertension: a qualitative study among African Americans with uncontrolled hypertension. Ethn Dis. 2007;17:29–34. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Lukoschek P. African Americans’ beliefs and attitudes regarding hypertension and its treatment: a qualitative study. J Health Care Poor Underserved. 2003;14:566–587. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Ogedegbe G, Harrison M, Robbins L, et al. Barriers and facilitators of medication adherence in hypertensive African Americans: a qualitative study. Ethn Dis. 2004;14:3–12. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Schoenberg NE, Drew EM. Articulating silences: experiential and biomedical constructions of hypertension symptomatology. Med Anthropol Q. 2002;16:458–475. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Perez‐Stable EJ, Salazar R. Issues in achieving compliance with antihypertensive treatment in the Latino population. Clin Cornerstone. 2004;6:49–61; discussion 2–4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Kaboli PJ, Shivapour DM, Henderson MS, et al. Patient and provider perceptions of hypertension treatment: do they agree? J Clin Hypertens (Greenwich). 2007;9:416–423. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Beune EJ, Haafkens JA, Schuster JS, Bindels PJ. ‘Under pressure’: How Ghanaian, African‐Surinamese and Dutch patients explain hypertension. J Hum Hypertens. 2006;20:946–955. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Leventhal H, Halm E, Horowitz C, et al. In: Sutton A, Johnston M, eds. Handbook of Health Psychology. London, UK: Sage Publishing; 2004:197–240. [Google Scholar]

- 22. Horowitz CR, Rein SB, Leventhal H. A story of maladies, misconceptions and mishaps: effective management of heart failure. Soc Sci Med. 2004;58:631–643. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Rose LE, Kim MT, Dennison CR, Hill MN. The contexts of adherence for African Americans with high blood pressure. J Adv Nurs. 2000;32:587–594. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Durack‐Bown I, Giral P, d’Ivernois JF, et al. Patients’ and physicians’ perceptions and experience of hypercholesterolaemia: a qualitative study. Br J Gen Pract. 2003;53:851–857. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Jackson JL, Chamberlin J, Kroenke K. Predictors of patient satisfaction. Soc Sci Med. 2001;52:609–620. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Meyer D, Leventhal H, Gutmann M. Common‐sense models of illness: the example of hypertension. Health Psychol. 1985;4:115–135. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Peters S, Stanley I, Rose M, Salmon P. Patients with medically unexplained symptoms: sources of patients’ authority and implications for demands on medical care. Soc Sci Med. 1998;46:559–565. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. de Ridder DT, Theunissen NC, van Dulmen SM. Does training general practitioners to elicit patients’ illness representations and action plans influence their communication as a whole? Patient Educ Couns. 2007;66:327–336. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Theunissen NC, de Ridder DT, Bensing JM, Rutten GE. Manipulation of patient‐provider interaction: discussing illness representations or action plans concerning adherence. Patient Educ Couns. 2003;51:247–258. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Wilson RP, Freeman A, Kazda MJ, et al. Lay beliefs about high blood pressure in a low‐ to middle‐income urban African‐American community: an opportunity for improving hypertension control. Am J Med. 2002;112:26–30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Connell P, McKevitt C, Wolfe C. Strategies to manage hypertension: a qualitative study with black Caribbean patients. Br J Gen Pract. 2005;55:357–361. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Leininger M. Culture, Care, Diversity, and Universality. Boston, MA: Hones and Barelett; 2001. [Google Scholar]