Abstract

Background

Experiments using Cre recombinase to study smooth muscle specific functions rely on strict specificity of Cre transgene expression. Therefore, accurate determination of Cre activity is critical to the interpretation of experiments using smooth muscle specific Cre.

Methods and Results

Two lines of smooth muscle protein 22 a-Cre (SM22a-Cre) mice were bred to floxed mice in order to define Cre transgene expression. Southern blotting demonstrated that SM22a-Cre was expressed not only in tissues abundant of smooth muscle, but also in spleen, which consists largely of immune cells including myeloid and lymphoid cells. PCR detected SM22a-Cre expression in peripheral blood and peritoneal macrophages. Analysis of SM22a-Cre mice crossed with a recombination detector GFP mouse revealed GFP expression, and hence recombination, in circulating neutrophils and monocytes by flow cytometry.

Conclusions

SM22 -Cre mediates recombination not only in smooth muscle cells, but also in myeloid cells including neutrophils, monocytes, and macrophages. Given the known contributions of myeloid cells to cardiovascular phenotypes, caution should be taken when interpreting data using SM22 -Cre mice to investigate smooth muscle-specific functions. Strategies such as bone marrow transplantation may be necessary when SM22 -Cre is used to differentiate the contribution of smooth muscle cells versus myeloid cells to observed phenotypes.

Keywords: SM22 -Cre, smooth muscle cells, myeloid cells, neutrophils, monocytes, macrophages

1. Introduction

Vascular smooth muscle cells play essential roles in development and progression of cardiovascular diseases such as atherosclerosis and hypertension. In atherosclerosis, smooth muscle cells (SMCs) proliferate and switch from a contractile phenotype to a synthetic phenotype characterized by production of extracellular matrix, adhesion molecules, and cytokines [1,2]. They also contribute to the formation of neointima, foam cells, and plaques at later stage of atherosclerosis. SMCs contribute to the vascular reactivity and remodeling changes that contribute to the pathophysiology of hypertension and its complications [3].

Myeloid cells are also important in these diseases. Inflammation is a critical factor in the progression of atherosclerosis [4]. Monocytes, macrophages, polymorphonuclear leukocytes, dendritic cells, and mast cells have been implicated in all stages of atherosclerosis, from initiation to progression to late complications [5, 6]. Monocytes and macrophages are also involved in vascular inflammation and remodeling in hypertensive animal models and reduced vascular inflammation is associated with improved blood pressure [3,7–9].

In order to study functions of genes in SMCs specifically, several Cre recombinase mouse lines have been created [10–16]. These mice have been extensively used to study functions of a variety of genes in cardiovascular diseases. The specificities of these lines were tested against different cell types and Cre recombinase was found to be expressed mostly in SMCs with different degrees of expression in cardiomyocytes in different lines. However, it has not been reported whether Cre recombinase is expressed in myeloid cells in these mouse lines. Given the importance of both SMCs and myeloid cells in vascular inflammation, it is critical to clarify this in order to determine whether SMCs are the only important target of certain gene functions in atherosclerosis or hypertension. We hypothesized that SM22 -Cre expression may not be strictly limited to SMCs. To test this, we have analyzed Cre expression in two commonly used SM22 -Cre strains available from the Jackson. In these two lines, Cre recombinase was either controlled by promoter of smooth muscle protein 22 alpha (SM22 ) or inserted into the SM22 locus [12,16].

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Animals

SM22 -Cre mice (4746 and 6878) were obtained from the Jackson Laboratory (Bar Harbor, Maine). SM22 -Cre(4746) mice were bred to floxed peroxisome-proliferator-activated-receptor- (PPAR-) mice [21] to produce smooth muscle specific PPAR- knockout (SM-PGKO; PPAR-flox/flox:Cre+) mice, littermate floxed control (LFC; PPAR-flox/flox:Crewt) mice, and littermate Cre control (LCC; PPAR-wt/wt:Cre+) mice.

Both SM22 -Cre(4746) and SM22 -Cre(6878) mice were bred to floxed dominant-negative-mastermind-like-green-fluorescent-protein (DNMAML-GFP) mice [18] to produce smooth muscle specific DNMAML-GFP (DNMAML-GFPflox/wt:Cre+) mice, and their LFC (DNMAML-GFPflox/wt:Crewt) and LCC (DNMAML-GFPwt/wt:Cre+) mice. Smooth muscle specific DNMAML-GFP mice produced using SM22 -Cre(6878) mice were designated as DNMAML1 and those using SM22 -Cre(4746) mice as DNMAML2. All animal protocols were approved by the University Committee on Use and Care of Animals of the University of Michigan (Animal Welfare Assurance Number A3114-01).

2.2. Southern blotting

Genomic DNA was extracted from a variety of tissues and digested with BamH1, separated by electrophoresis, transferred to nylon membrane, and hybridized with a 32P-labled DNA probe as described before [22,23]. The results were captured using a PhosphorImager screen (Bio-Rad Laboratories, Hercules, California).

2.3. Genotyping PCR

Tail DNA was extracted and traditional PCR was used to detect floxed or recombined allele.

2.4. Flow cytometry analysis of peripheral blood

Tail vein blood samples were collected in heparinized capillary tubes. After erythrocyte lysis, blood cells were blocked with FcBlock (BD Biosciences, San Jose, California) and stained with antibodies for flow cytometry (APC Anti-CD115, APC-Alexa750 Anti-Gr-1, and PE Anti-CD8 all from Ebioscience, San Diego, California). Cells were analyzed on a FACSCanto II system (BD Bioscience).

3.Results

3.1. SM22 -Cre is expressed in spleen, peripheral blood, and peritoneal macrophages

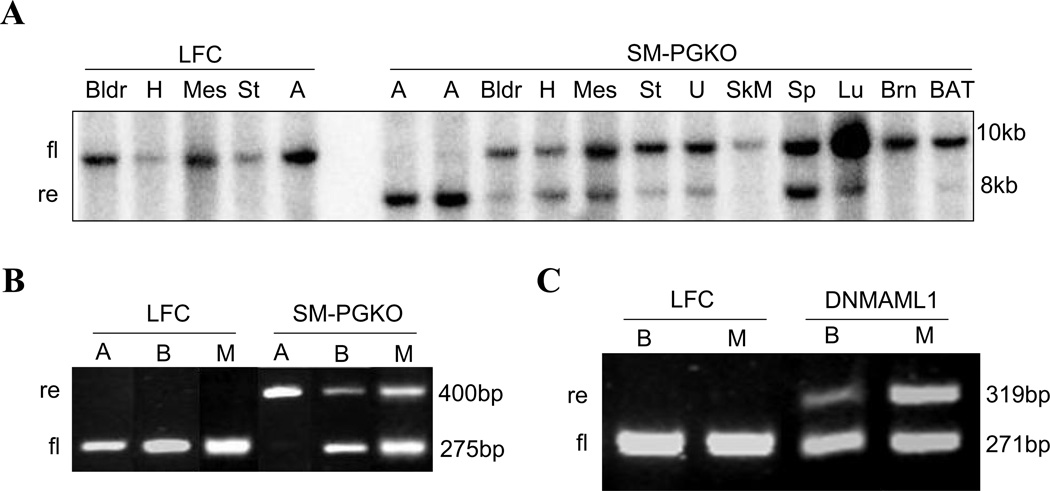

We first evaluated the specificity of SM22 -Cre in both SM-PGKO and DNMAML1 mice using Southern blotting and/or genotyping PCR. Southern blotting results showed that in SM-PGKO mice, the recombined allele was present in smooth muscle-enriched tissues such as aorta, bladder, heart, mesenteric tissue, stomach, uterus, and lungs as expected (Fig. 1A). Surprisingly, the recombined allele was also present in high percentage in the spleen, demonstrating the expression of SM22 -Cre(4746). Although the spleen does not contain large numbers of SMCs, it is capable of contraction and smooth muscle myosin has been seen in other splenic cells in addition to vascular SMCs [17]. Still, because the majority of cells in the spleen are of immune origin and high degree of recombination was detected, we investigated whether immune cells also demonstrated recombination. Genotyping PCR detected the recombined allele not only in aorta but also in the peripheral blood and peritoneal macrophages of both SM-PGKO and DNMAML1 mice, demonstrating the expression of SM22 -Cre(4746 and 6878) in these tissues/cells (Fig.1B,C).

Fig. 1.

SM22 -Cre is expressed in spleen, peripheral blood, and peritoneal macrophages. A. Southern blotting results of a variety of tissues from LFC and SM-PGKO mice produced by crossing SM22 -Cre(4746) mice with floxed PPAR- mice. LFC: littermate floxed control; SM-PGKO: smooth muscle specific PPAR- knockout; fl: floxed allele; re: recombined allele. A: aorta; BAT: brown adipose tissue; Bldr: bladder; Brn: brain; H: heart; Lu: lung; Mes: mesenteric tissue; SkM: skeletal muscle; Sp: spleen; St: stomach; U: uterus. B. PCR genotyping results of tissues from LFC and SM-PGKO mice. A: aorta; B: blood; M: macrophage (peritoneal). C. PCR genotyping results of tissues from LFC and DNMAML1 mice produced by crossing SM22 -Cre(6878) mice with floxed DNMAML-GFP mice. For all experiments similar results were obtained from 2–3 independent mice and representative analysis is shown. The results of littermate Cre control (LCC) were similar to those of LFC.

3.2. SM22 -Cre is expressed in neutrophils and monocytes in peripheral blood

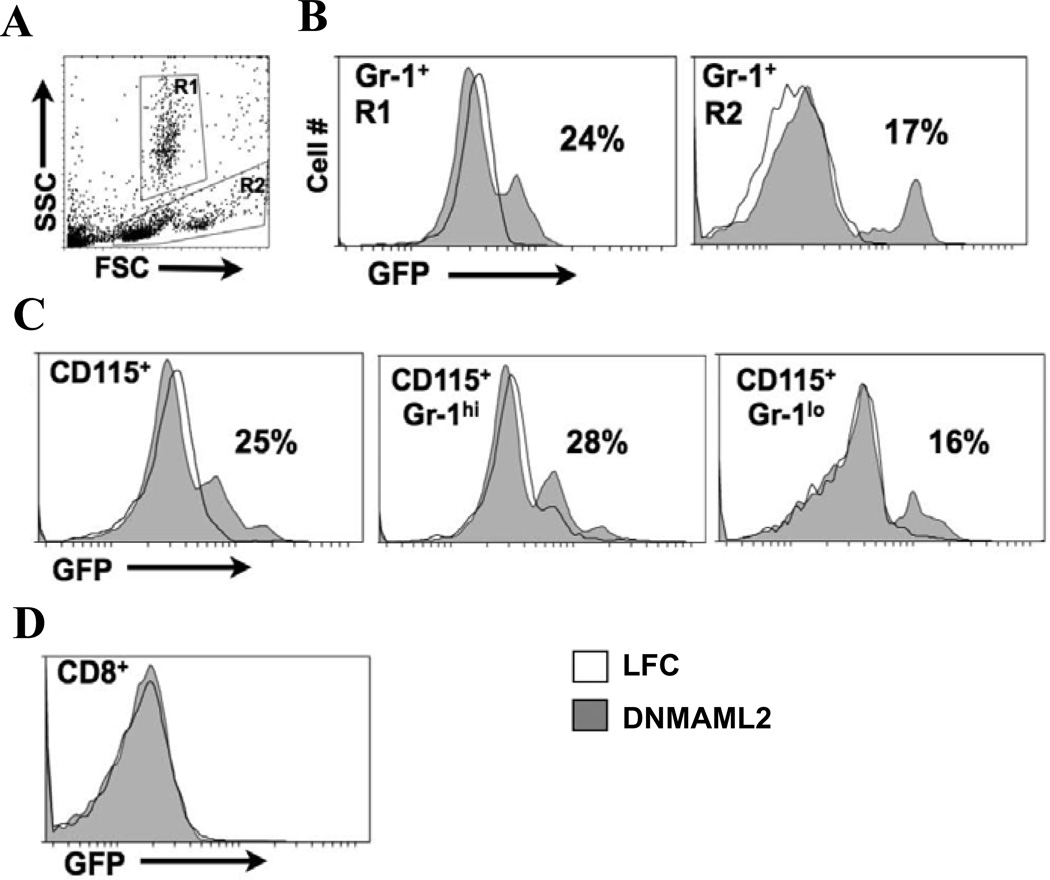

To identify which populations of peripheral blood cells express SM22 -Cre(4746), we used flow cytometry to examine the expression of GFP in blood samples from DNMAML2 and their control mice. The floxed DNMAML-GFP is ubiquitously expressed because Rosa 26 locus was used to generate the floxed mice [18,19]. Therefore, any cell type that expresses the Cre will have GFP expression to show recombination. Initial analysis showed that a portion of Gr-1+ neutrophils and monocytes/lymphocytes in the circulation were GFP+ in DNMAML2 mice (Fig. 2A, B). LFC and LCC mice did not show GFP expression in either of these cell populations. To determine whether SM22 -Cre(4746) is expressed in peripheral monocytes or lymphocytes, we used CD115 to label monocytes specifically and detected GFP expression in CD115+ cells, demonstrating the expression of SM22 -Cre in this subpopulation (Fig. 2C). Further analysis showed that SM22 -Cre(4746) was activated in a subset of Gr-1hi and Gr-1lo monocytes in DNMAML2 mice. However, GFP was not expressed in CD8+ lymphocytes from DNMAML2 mice, indicating that SM22 -Cre(4746) was not expressed in this population (Fig. 2D).

Fig. 2.

SM22 -Cre is expressed in neutrophils and monocytes in peripheral blood. A. Forward (FSC) and side scatter (SSC) plots from peripheral blood with gates used for neutrophils and monocytes/lymphocytes. B. GFP expression in Gr-1+ cells in neutrophils (R1) or monocytes/lymphocytes (R2) gates from blood of LFC and DNMAML2 mice produced by crossing SM22 -Cre(4746) mice with floxed DNMAML-GFP mice. Percentage of GFP+ cells in DNMAML2 mice is shown. LFC: littermate floxed control. C. GFP expression in CD115+ cells demonstrates SM22 -Cre expression in circulating monocytes. CD115+ cells were further assessed for Gr-1 expression delineating monocyte subtypes. hi: high; lo: low. D. GFP is not expressed in CD8+ lymphocytes. For all experiments similar results were obtained from 2–3 independent mice and representative analysis is shown. The results of littermate Cre control (LCC) were similar to those of LFC.

4. Discussion

Smooth muscle specific Cre is an important tool to study gene functions in smooth muscle cells [10–16]. However, its specificity has not been fully investigated, although expression in cardiomyocytes and epithelial cells had been noticed [11,15, 16,20]. In this study, we have demonstrated that SM22 -Cre, a frequently used smooth muscle specific Cre, is expressed in a portion of myeloid cells including neutrophils, monocytes, and macrophages. Such expression will lead to genetic changes in these cells, as well as in SMCs, when SM22 -Cre is used in combination with floxed mice. In this circumstance, therefore, it will be impossible to unequivocally attribute the resulting phenotypes to changes in SMCs, myeloid cells or both. Given the importance of both cell types in vascular development and cardiovascular disease, this is a critical distinction. In order to circumvent this potential problem and restrict genetic changes to SMCs, bone marrow transplantation may be useful to replace the recombined circulating myeloid cells to determine if they contribute to the resultant phenotypes.

Acknowledgments

This work was funded by grants R01HL083201 from the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute, NIH and 1-08-RA-137 from American Diabetes Association (to R.M. Mortensen), as well as grants from institute for Nutritional Sciences, Shanghai Institutes for Biological Sciences, Chinese Academy of Sciences, the National Natural Science Foundation of China (31171133), and Xuhui Central Hospital, Shanghai, China (CRC2011003) (to S.Z. Duan).

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Disclosures

None

References

- 1.Cai W, Schaper W. Mechanisms of arteriogenesis. Acta. Biochim. Biophys. Sin. (Shanghai) 2008;40:681–692. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Doran AC, Meller N, McNamara CA. Role of smooth muscle cells in the initiation and early progression of atherosclerosis. Arterioscler. Thromb. Vasc. Biol. 2008;28:812–819. doi: 10.1161/ATVBAHA.107.159327. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Savoia C, Schiffrin EL. Inflammation in hypertension. Curr. Opin. Nephrol. Hypertens. 2006;15:152–158. doi: 10.1097/01.mnh.0000203189.57513.76. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ross R. Atherosclerosis--an inflammatory disease. N. Engl. J. Med. 1999;340:115–126. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199901143400207. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Soehnlein O, Weber C. Myeloid cells in atherosclerosis: initiators and decision shapers. Semin. Immunopathol. 2009;31:35–47. doi: 10.1007/s00281-009-0141-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Shimada K. Immune system and atherosclerotic disease: heterogeneity of leukocyte subsets participating in the pathogenesis of atherosclerosis. Circ. J. 2009;73:994–1001. doi: 10.1253/circj.cj-09-0277. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Nava M, Quiroz Y, Vaziri N, Rodriguez-Iturbe B. Melatonin reduces renal interstitial inflammation and improves hypertension in spontaneously hypertensive rats. Am. J. Physiol. Renal. Physiol. 2003;284:F447–F454. doi: 10.1152/ajprenal.00264.2002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Liao TD, Yang XP, Liu YH, Shesely EG, Cavasin MA, Kuziel WA, Pagano PJ, Carretero OA. Role of inflammation in the development of renal damage and dysfunction in angiotensin II-induced hypertension. Hypertension. 2008;52:256–263. doi: 10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.108.112706. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Duan SZ, Usher MG, Mortensen RM. PPARs: the vasculature, inflammation and hypertension. Curr. Opin. Nephrol. Hypertens. 2009;18:128–133. doi: 10.1097/MNH.0b013e328325803b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kuhbandner S, Brummer S, Metzger D, Chambon P, Hofmann F, Feil R. Temporally controlled somatic mutagenesis in smooth muscle. Genesis. 2000;28:15–22. doi: 10.1002/1526-968x(200009)28:1<15::aid-gene20>3.0.co;2-c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Regan CP, Manabe I, Owens GK. Development of a smooth muscle-targeted cre recombinase mouse reveals novel insights regarding smooth muscle myosin heavy chain promoter regulation. Circ. Res. 2000;87:363–369. doi: 10.1161/01.res.87.5.363. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Holtwick R, Gotthardt M, Skryabin B, Steinmetz M, Potthast R, Zetsche B, Hammer RE, Herz J, Kuhn M. Smooth muscle-selective deletion of guanylyl cyclase-A prevents the acute but not chronic effects of ANP on blood pressure. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2002;99:7142–7147. doi: 10.1073/pnas.102650499. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Xin HB, Deng KY, Rishniw M, Ji G, Kotlikoff MI. Smooth muscle expression of Cre recombinase and eGFP in transgenic mice. Physiol. Genomics. 2002;10:211–215. doi: 10.1152/physiolgenomics.00054.2002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Miano JM, Ramanan N, Georger MA, de Mesy Bentley KL, Emerson RL, Balza RO, Jr, Xiao Q, Weiler H, Ginty DD, Misra RP. Restricted inactivation of serum response factor to the cardiovascular system. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2004;101:17132–17137. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0406041101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lepore JJ, Cheng L, Min Lu M, Mericko PA, Morrisey EE, Parmacek MS. High-efficiency somatic mutagenesis in smooth muscle cells and cardiac myocytes in SM22alpha-Cre transgenic mice. Genesis. 2005;41:179–184. doi: 10.1002/gene.20112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Zhang J, Zhong W, Cui T, Yang M, Hu X, Xu K, Xie C, Xue C, Gibbons GH, Liu C, Li L, Chen YE. Generation of an adult smooth muscle cell-targeted Cre recombinase mouse model. Arterioscler. Thromb. Vasc. Biol. 2006;26:e23–e24. doi: 10.1161/01.ATV.0000202661.61837.93. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Pinkus GS, Warhol MJ, O'Connor EM, Etheridge CL, Fujiwara K. Immunohistochemical localization of smooth muscle myosin in human spleen, lymph node, and other lymphoid tissues. Unique staining patterns in splenic white pulp and sinuses, lymphoid follicles, and certain vasculature, with ultrastructural correlations. Am. J. Pathol. 1986;123:440–453. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Tu L, Fang TC, Artis D, Shestova O, Pross SE, Maillard I, Pear WS. Notch signaling is an important regulator of type 2 immunity. J. Exp. Med. 2005;202:1037–1042. doi: 10.1084/jem.20050923. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Soriano P. Generalized lacZ expression with the ROSA26 Cre reporter strain. Nat. Genet. 1999;21:70–71. doi: 10.1038/5007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Proweller A, Tu L, Lepore JJ, Cheng L, Lu MM, Seykora J, Millar SE, Pear WS, Parmacek MS. Impaired notch signaling promotes de novo squamous cell carcinoma formation. Cancer Res. 2006;66:7438–7444. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-06-0793. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Akiyama TE, Sakai S, Lambert G, Nicol CJ, Matsusue K, Pimprale S, Lee YH, Ricote M, Glass CK, Brewer HB, Jr, Gonzalez FJ. Conditional disruption of the peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor gamma gene in mice results in lowered expression of ABCA1, ABCG1, and apoE in macrophages and reduced cholesterol efflux. Mol. Cell Biol. 2002;22:2607–2619. doi: 10.1128/MCB.22.8.2607-2619.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Duan SZ, Ivashchenko CY, Russell MW, Milstone DS, Mortensen RM. Cardiomyocyte-specific knockout and agonist of peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor-gamma both induce cardiac hypertrophy in mice. Circ. Res. 2005;97:372–379. doi: 10.1161/01.RES.0000179226.34112.6d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Duan SZ, Ivashchenko CY, Whitesall SE, D'Alecy LG, Duquaine DC, Brosius FC, 3rd, Gonzalez FJ, Vinson C, Pierre MA, Milstone DS, Mortensen RM. Hypotension, lipodystrophy, and insulin resistance in generalized PPARgamma-deficient mice rescued from embryonic lethality. J. Clin. Invest. 2007;117:812–822. doi: 10.1172/JCI28859. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]