Abstract

Youth infected with HIV at birth often have sleep disturbances, neurocognitive deficits, and abnormal psychosocial function which are associated with and possibly resulted from elevated blood cytokine levels that may lead to a decreased quality of life. To identify molecular pathways that might be associated with these disorders, we evaluated 38 HIV-infected and 35 uninfected subjects over 18-months for intracellular cytokine levels, sleep patterns and duration of sleep, and neurodevelopmental abilities. HIV infection was significantly associated with alterations of intracellular pro-inflammatory cytokines (TNF-α, IFN-γ, IL-12), sleep factors (total time asleep and daytime sleep patterns), and neurocognitive factors (parent and patient reported problems with socio-emotional, behavioral, and executive functions; working memory-mental fatigue; verbal memory; and sustained concentration and vigilance. By better defining the relationships between HIV infection, sleep disturbances, and poor psychosocial behavior and neurocognition, it may be possible to provide targeted pharmacologic and procedural interventions to improve these debilitating conditions.

Keywords: pediatric HIV infection, intracellular cytokines, sleep behavior, neurodevelopment, neurocognition, path analysis

1. Introduction

HIV infection often produces altered sleep-regulating hormones and cytokine levels [1-3], sleep problems and fatigue [4,5], abnormal neurocognitive and psychosocial function, and a increased frequency of psychotic illness and early dementia [5-13], as well as impaired immune function [14-18]. In turn, poor sleep and fatigue are related to altered patterns of growth hormone secretion in children with HIV infection [19]. The one report of sleep disturbances in children with HIV infection [20] did not address a molecular mechanism or assess neurocognitive deficits that might result from these sleep disturbances. The effects of impaired sleep and increased fatigue on HIV disease progression, neurocognitive function, and psychosocial behavior in HIV-infected children can potentially impair school performance, future employment, and general quality of life. It is also unclear whether altered production of sleep-regulating hormones and cytokines is associated with the sleep abnormalities and the neuropsychological deficits seen in these children.

More than 2.5 million children and adolescents worldwide have perinatally-acquired HIV infection, and 40% of the yearly-incident 50,000 HIV infections in the U.S. occur in adolescents and young adults [21], so there is an urgency to understand the possible effects of HIV infection on immune responses, sleep patterns, and neurocognitive and psychosocial function. Such an understanding will require a multidisciplinary investigation into the clinical and physiological aspects of these symptoms, their causes and possible treatment. Entry of the estimated 20,000 newly HIV-infected U.S. youth each year into higher education and the work force have been addressed by providing flexible academic and workplace schedules, peer support groups, and balancing patients’ medical care times with educational and workplace responsibilities [22]. We report here the results of a cohort study in which HIV-infected children and uninfected children were compared for differences in cytokine production, sleep patterns, and neurocognitive function.

2. Methods and Materials

2.1. Patients and Recruitment Strategies

This study was approved by the Institutional Review Boards of Baylor College of Medicine (BCM) and Texas Children’s Hospital (TCH), Houston, Texas, and the University of Miami, Miami, Florida. Written informed consent was obtained from parents or legal guardians, and assent was obtained from children when appropriate.

Subjects were recruited from the BCM Pediatric HIV Research Clinics/Texas Children’s Hospital and from the University of Miami Pediatric HIV Research Clinic/Holtz Children’s Hospital (HCH). HIV-non-infected control subjects were selected from siblings, family members, and friends of the HIV-infected subjects. When possible, controls were matched for age, socioeconomic variables, ethnicity, HIV exposure, sex, and race of the general patient group. Individuals with sleep apnea and asthma were initially excluded from the study. After asthma developed in several subjects and controls [23-25] during the study, the asthma exclusion was lifted.

2.2. Study Overview

All subjects were admitted at a baseline and at 12-months for 24-hours to the General Clinical Research Center (GCRC) at TCH or for 12-hours (overnight) at HCH. During these visits, sleep and fatigue, and neurocognitive and psychosocial characteristics were assessed, and blood was drawn to allow serial measurement of cytokines, hormones, and HIV disease markers. At months 6 and 18 all subjects also took part in 2-hour GCRC visits during which HIV disease markers, neurocognition, psychosocial function, and sleep were assessed in a more limited evaluation.

2.3. Measurement of Cytokines

During the 24-hour visits at baseline and at 12-months, blood samples from all subjects were taken from the non-dominant arm through a peripheral venous catheter. Concentrations of spontaneous and inducible cytokines, interleukin (IL)-10, IL-12, tumor necrosis factor-alpha (TNF-α), and interferon-gamma (IFN-γ) production by lymphocytes were measured by flow cytometry on samples collected at 4 am and 4 pm, when growth hormone secretion is at its peak and trough, respectively [26-27]. At all study visits, we measured markers of HIV disease progression: CD4+ T-cell count, HIV RNA levels, and inducible cytokine production by peripheral blood lymphocytes, as previously described [28]. Intracellular cytokine synthesis by phorbol myristate acetate (PMA) and staphylococcal enterotoxin B (SEB) activated T cells (CD3+/CD69+) was determined using gating strategies for four-color, flow cytometry analysis [29].

2.4. Assessment of Sleep

To obtain measures of sleep and night-to-night variability in children with a minimum of inconvenience, we used wrist actigraphy, an accepted, cost-effective technology for measuring sleep-wake patterns over several days [30]. Wrist actigraphy (Octagonal Basic Motionlogger-L, Ambulatory Monitoring, Inc., Ardsley, NY), with the actigraph worn on the non-dominant wrist, was performed during the week before baseline and the 12-month GCRC visit and during the week after each of these visits. Analysis of the actigraphy data was performed by the software included with the actigraphs and interpreted by blinded sleep technicians and physicians. Limited polysomnography studies performed during overnight admissions validated the actigraphy results.

2.5. Neurobehavioral Tests

Neurobehavioral performance was assessed at baseline and at the 12-month visit with a battery of tests (Table 1). All the measures included in the battery are standardized, normalized and referenced tests, have strong reliability and validity, and are used widely for clinical purposes [31]. The mean and standard deviation for the normative samples are included in Table 1 and represent the standard scoring system for those measures. The individually administered performance tasks assessed neurocognitive domains known to be sensitive to the effects of fatigue or central nervous system dysfunction. The rating scales (completed by the parent and by the child) assessed socio-emotional status and executive functioning in everyday activities. The rating scales also were administered to the TCH participants at the 6-month and 18-month visits.

Table 1. Neurodevelopmental Tests Administered to Youth with HIV Infection and Controls in a Study of the Relationships between HIV and Cytokine Production, Sleep Patterns, and Neurocognitive Function.

| Test | Function Assessed | Score Distribution, mean (SD) |

|---|---|---|

|

Children’s Paced-Serial Addition Test (CHIPASAT) |

Cognitive and motor speed | 100 (15) |

|

Children’s Memory Scale (CMS), Stories subtest |

Verbal memory | 10 (3) |

|

Conners’ Continuous Performance Test, 2nd Ed (CPT-II) |

Vigilance and sustained attention | 50 (10) |

|

Delis-Kaplan Executive Function System (D-KEFS) – Motor Speed Index |

Motor processing speed | 10 (3) |

|

Behavior Assessment System for Children, 2nd Ed, (BASC-II) |

Emotional and behavioral status (e.g., mood, anxiety, attention, activity level, aggression, conduct, self-efficacy, social skills, etc.). Rating scale completed by caregiver report and child self-report. |

50 (10) |

|

Behavior Rating Inventory of Executive Function (BRIEF) |

Executive function abilities in everyday life (e.g., working memory, organization and planning, self-monitoring, initiative). Rating scale completed by caregiver report and child self-report. |

50 (10) |

The scores are the set values for a normative population.

The tests were administered and scored either by a licensed psychologist or by an individual with specific education and training in psychological test administration under the direct supervision of a licensed psychologist.

2.5.1. Statistical Methods

Data collected for each subject were recorded in standard data collection forms. A study-specific relational database was designed using the standard data collection forms as a template.

2.5.2. Univariate Factor Analysis

To avoid multiple testing problems, and to increase the likelihood of detecting pathway signals from the resulting data analyses, a factor analysis was used to reduce the number of variables analyzed in the study [32]. A factor analysis was performed for each of the following groups of outcomes: cytokine variables, actigraphy variables, and neurodevelopmental variables. Factor analysis reduces a group of variables using their covariance structure to a lower number of latent variables that can be described by linear combinations of the observed variables [33].

Factor analysis with oblique rotation resulted in reducing the number of outcome variables from 53 individual cytokine, sleep and actigraphy variables to 15 factors distributed among these three areas [34]. A scree plot was used to determine the factors retained for future analyses [35]. Within a factor, observed variables with loadings (the coefficients used to create the linear combinations of observed variables) greater than 0.5 were reweighted into a clinical loading that set the weighting at full value (setting the loading to 1). Reloading for each factor was done so that an observed variable was only loaded into one clinical factor: the one with the highest loading for the observed variable. After this operation, the linear combination of the observed variables in a statistical factor was reduced to the arithmetic mean of the observed variables in the clinical factor and represented the clinical factor’s score. Once the clinical factors were developed, each clinical factor was confirmed by checking the correlation of the clinical factor with the original statistical factor score. A factor was retained if the R2 was greater than 88%. In univariate analysis, this threshold corresponds to a correlation coefficient of 0.94 or greater.

2.5.3. Bivariate Analyses of Factors

The association of HIV status with each factor was examined using Generalized Estimating Equations (GEE). Each model was adjusted for a study visit effect. The GEE approach was used to account for inter-subject correlations across the four visits where data were collected [36]. Using the methods described above, the associations within and among the neurodevelopment (ND)-related factors (NDF), intracellular cytokine-related factors (ICF), and sleeping (actigraphy)-related factors (AF) were compared. The associations showing potential statistical significance were included in the multivariate path analysis.

2.5.4. Multiple Imputation and Multivariate Path Analysis

Factors with missing data were imputed (estimated using statistical relationships with other factors) using the method of multiple imputation. Without performing this step, 46.4% of factors developed for each patient would have been missing. The missing factors were imputed five times. Multivariate analysis was performed on each “complete” factor data set using path analysis (Covariance Analysis of Linear Structural Equation) CALIS [37]. As required by path analysis, causation had to be assumed and medical experts assumed the flow of causation to go from HIV infection to intracellular cytokines to sleep patterns to neurocognition. Summary estimates were obtained by using a roll-up estimator; a statistical average of the parameter estimates obtained from each imputed dataset. Statistical significance was also inferred from the values of the roll-up estimators and their standard errors. Exploratory data analysis showed one outlying observation for AF 4 which was excluded from further analysis. Associations between HIV infection, ICF, AF, and NDF were reported as showing trend significance if P-values were < 0.10 but ≥0.05 and showing absolute significance if the P-values were < 0.05. All statistical analyses were performed with the SAS statistical software package.

3. Results

3.1. Study Population and Demographics

Between 2000 and 2004, the study enrolled 38 subjects with HIV infection and 35 uninfected controls, 22 of whom had not been exposed to HIV perinatally, 11 who had been exposed, and 2 whose exposure status was unknown.

Of the 38 children with HIV, 26 were enrolled at TCH and 12 were enrolled at HCH. All controls were enrolled at TCH; patients at TCH and HCH did not differ demographically (data not shown). All participants completed the initial enrollment visit and associated studies at baseline. Of the HIV-infected children, 28 of 34 eligible (82%) completed the 6-month visit; 28 of the 33 eligible (85%) completed the 12-month visit; and 23 of the 26 eligible (88%) completed the 18-month visits. Among the 35 controls, 35 (100%) completed the 6-month visit; 33 (94%) completed the 12-month visit; and 31 (89%) completed the 18-month visit. The 4-year study ended before all subjects could complete the data-collection visits. Thus, the effective sample size for HIV-infected subjects was 38 at baseline, 34 at 6-months, 33 at 12-months, and 26 at 18-months.

The groups did not differ by age, sex, race, ethnicity, or family income (Table 2). A diagnosis of asthma and the use of asthma medications were not significantly related to any of the outcome variables (data not shown), so children with asthma were included in subsequent analyses. As expected, mean CD4+ T cell percentages were lower in HIV-infected subjects than those in controls (P < 0.01).

Table 2. Baseline (Time 0-Months) Characteristics of Youth between 8 and 17 Years of Age with HIV Infection and Uninfected Controls.

| Characteristics | Subjects with HIV infection (n=38) |

Uninfected Controls (n=35) |

P-Valuea |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age, mean(SD), year | 13(2.5) | 13(3.2) | 0.91 |

| Boys, n (%) | 19 (50) | 17(49) | 0.99 |

| Race, n (%) | |||

| African American | 30 (79) | 27 (77) | 0.84 |

| Caucasian | 6 (16) | 5 (14) | |

| Other | 2 (5) | 3 (9) | |

| Ethnicity, n (%) | |||

| Latino | 4 (11) | 5 (14) | 0.59 |

| Non-Latino | 34 (90) | 30 (86) | |

| Family Income, n (%) | |||

| $10,000 or less | 8 (21) | 8 (23) | 0.99 |

| $10,001 - 40,000 | 20 (53 | 17 (49) | |

| > $40,000 | 5 (13) | 5 (14) | |

| Not available | 5 (13) | 5 (14) | |

| HIV Viral Loadb, mean (SD) | 2.1 (2.1) | - - - | - - - |

| CD4 %, mean (SD) | 28.7 (12.1) | 40.0 (7.4) | <0.01 |

P-value from a Chi-square, Fisher exact, or F-test statistic comparing distributions among the 2 groups (significant P-values are bolded).

HIV viral load measurements were Log10-transformed values were calculated as follows: if HIV RNA > 400 copies/mL, use formula log10 (HIV RNA + 1); assign 0 if HIV RNA ≤ 400 copies/mL.

CD4+ %, mean (SD)

3.2. Results of Immunologic, Sleep, and Neurodevelopmental Testing (Univariate Analysis)

Intracellular cytokine levels, actigraphy results, and neurodevelopmental test scores collected at the baseline (Time 0-months) study visit for HIV-infected and controls are displayed in Tables 3 through 5. The factor groupings and their definitions used in all subsequent analyses of the relationships among cytokines, actigraphy measures, and neurodevelopmental assessments are included in these tables.

Table 3. Intracellular Cytokine Levels (Averaged Across Time Points at Baseline – 0 Months) for HIV-Infected Youth and Uninfected Controls.

| Intracellular cytokine-related factor |

Measures contributing to the factor |

Subjects with HIV infection (n=38) |

Uninfected controls (n=35) |

||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean (SD) | Mean (SD) | P-Value a | Direction of score | ||

| 1 | PMA CD4+ IL-10 | 4 (2.9) | 6.3 (7.1) | 0.18 | Anti-inflammatory |

| PMA CD8+ IL-10 | 3.2 (3.5) | 5.7 (9) | 0.25 | Anti-inflammatory | |

| SEB CD4+ IL-10 | 4 (2.9) | 5.2 (6.9) | 0.42 | Anti-inflammatory | |

| SEB CD8+ IL-10 | 2.9 (3.3) | 4.5 (6.8) | 0.28 | Anti-inflammatory | |

| US CD4+ IL-10 | 2.9 (2.3) | 5.1 (8.9) | 0.28 | Anti-inflammatory | |

| US CD8+ IL-10 | 2.6 (3.1) | 5 (8) | 0.21 | Anti-inflammatory | |

| 2 | PMA CD4+ CD69+ | 76 (33.8) | 88.4 (28.3) | 0.23 | Cell Activation |

| PMA CD4+ TNF-α | 21.2 (15.2) | 27 (17.7) | 0.25 | Pro-inflammatory | |

| PMA CD8+ CD69+ | 63.9 (35.4) | 86.2 (26.4) | 0.03 | Cell Activation | |

| PMA CD8+ TNF-α | 17.4 (16.2) | 21.5 (14.4) | 0.37 | Pro-inflammatory | |

| 3 | SEB CD4+ IFN-γ | 3.4 (2.9) | 2.4 (1.6) | 0.12 | Pro-inflammatory |

| SEB CD4+ TNF-α | 5.9 (4.2) | 3.6 (2.3) | 0.01 | Pro-inflammatory | |

| SEB CD8+ IFN-γ | 5.2 (4) | 1.9 (1.1) | < 0.01 | Pro-inflammatory | |

| SEB CD8+ TNF-α | 2.5 (2.2) | 1.3 (0.8) | < 0.01 | Pro-inflammatory | |

| 4 | SEB CD8+ CD69+ | 10.3 (10.2) | 9.1 (7.2) | 0.67 | Cell Activation |

| US CD4+ CD69+ | 4.1 (6.2) | 2.5 (2.9) | 0.29 | Cell Activation | |

| US CD8+ CD69+ | 3.3 (5.2) | 3.9 (6.4) | 0.74 | Cell Activation | |

| 5 | US CD4+ IFN-γ | 2.6 (5.1) | 0.5 (0.5) | 0.07 | Pro-inflammatory |

| US CD8+ IFN-γ | 1.7 (3.4) | 0.4 (0.5) | 0.07 | Pro-inflammatory | |

| US CD8+ TNF-α | 0.4 (0.7) | 0.3 (0.4) | 0.85 | Pro-inflammatory | |

| 6 | SEB CD4+ IL-12 | 1.4 (1.3) | 1.1 (0.5) | 0.36 | Pro-inflammatory |

| SEB CD8+ IL-12 | 0.8 (1.9) | 0.9 (0.9) | 0.91 | Pro-inflammatory | |

| PMA CD4+ IL-12 | 0.9 (1.1) | 0.5 (0.5) | 0.08 | Pro-inflammatory | |

| PMA CD8+ IL-12 | 0.3 (0.2) | 0.3 (0.4) | 0.59 | Pro-inflammatory | |

P-value from an F-test statistic comparing distributions between the 2 groups (significant P-values are bolded). For individual tests, the number of HIV+ subjects ranged from 14 to 31 and that for controls ranged from 9 to 30 for controls.

Table 5. Neurodevelopment Variable Analysis from Baseline (Time 0-Months) Visit for HIV-Infected Youth and Controls. (See Table 1 for a description of these measures.).

| Subjects with HIV infection (n=38) |

Uninfected Controls (n=35) |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Neurodevelopmental Factor |

Measures contributing to the factor |

Mean (SD) | Mean (SD) | P- Value * |

Higher score is: |

|

1 (parent reported problems with socio-emotional, behavioral, and executive functioning) |

BRIEF T Score BRI | 53.9 (10.6) | 53.7 (10.3) | 0.94 | Worse |

| BRIEF T Score MI | 56.1 (9.9) | 51.9 (10.2) | 0.09 | Worse | |

| BRIEF T Score GEC | 55.5 (9.8) | 52.7 (10.5) | 0.23 | Worse | |

| BASC Parent T Externalizing | 49.5 (10.9) | 50.9 (13) | 0.64 | Worse | |

| BASC Parent T Internalizing | 50.9 (8.6) | 47.6 (10.5) | 0.18 | Worse | |

| BASC Parent T Behavior | 49.3 (11.2) | 49.1 (11.6) | 0.94 | Worse | |

| BASC Parent T Maladaptive | 55.9 (10.3) | 53.2 (11.5) | 0.33 | Worse | |

|

2 (working memory-mental fatigue) |

CHIPASAT Standard B | 92.8 (24.8) | 109 (17.3) | < 0.01 | Better |

| CHIPASAT Standard C | 95.4 (28.7) | 110.1 (21.6) | 0.02 | Better | |

| CHIPASAT Standard D | 100.7 (31.7) |

119 (24.5) | 0.01 | Better | |

| CHIPASAT Standard E | 112.9 (33.8) |

133.6 (31.1) | 0.01 | Better | |

| DELIS-KAPLAN Scaled Motor Speed |

9.5 (2.5) | 10.8 (2.6) | < 0.05 | Better | |

|

3 (self-reported problems with socio-emotional, behavioral, and executive functioning) |

BRIEF Self T BRI | 50.4 (10.8) | 46.9 (8.5) | 0.21 | Worse |

| BRIEF Self T MI | 53.8 (13.3) | 46.6 (7) | 0.02 | Worse | |

| BRIEF Self T GEC | 52.4 (11.9) | 46.6 (7.6) | 0.05 | Worse | |

| BASC Self T Emotional Symptoms | 48.1 (9) | 48.9 (9.8) | 0.72 | Worse | |

|

4 (verbal memory) |

CMS Stories Scaled Immediate | 7.8 (3.4) | 7.7 (3.1) | 0.97 | Better |

| CMS Stories Scaled Delayed | 8 (3.4) | 8 (3) | 0.98 | Better | |

| CMS Stories Scaled Recognition | 7.8 (3.3) | 8.1 (3.1) | 0.74 | Better | |

|

5 (sustained concentration and vigilance) |

CPT T Omissions | 54.8 (17.9) | 52.9 (12.8) | 0.63 | Worse |

| CPT T Hit Reaction | 54.2 (11.7) | 53.4 (12.2) | 0.78 | Worse | |

| CPT T Variability | 55.7 (11.2) | 54.1 (11.9) | 0.57 | Worse | |

P-value from an F-test statistic comparing distributions between the 2 groups. For individual tests, n=31-38 for HIV+ subjects and 21-32 for controls.

Intracellular cytokine production at 4 am versus 4 pm did not differ significantly for any of the cytokines measured, so the mean level of expression for each cytokine was used in the analyses (Table 3). Compared to controls within ICF 2, children with HIV infection had fewer CD8+ T cells expressing an activation marker (CD69) when stimulated with PMA (P = 0.03), but within ICF 3 more CD4+ and CD8+ T cells with higher percentages of expression of TNF-α with SEB stimulation (P≤0.01). SEB-stimulated CD8+ T cells in these children also had higher levels of expression of IFN-γ than did those of controls (P < 0.01). None of the other ICFs differed significantly between HIV-infected and control groups.

HIV-infected children spent somewhat less time awake in bed than did controls (P < 0.03) (AF 2), and they appeared to sleep more during the day (AF 4), but this and other differences among the other actigraphy variables in the AFs were not significant (Table 4).

Table 4. Baseline (Time 0-Months) Values of All Individual Sleep Variables for Youth with HIV and Uninfected Controls.

| Sleep actigraphy- related factors |

Measures contributing to the factor |

Subjects with HIV infection (n=27) |

Uninfected controls (n=32) |

||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean (SD) | Mean (SD) | P-Value* | Direction of score | ||

| 1 | Sleep Efficiency, % |

92.4 (6.6) | 91.1 (6.4) | 0.40 | Higher scores = a greater percentage of time in bed asleep |

| 2 | Total Time Awake at Night, minutes |

9.2 (4.1) | 12.4 (6.3) | 0.03 | Higher scores = more time spent in bed awake |

| # Times Waking at Night, n |

34 (21.1) | 42.9 (33.4) | 0.24 | Number of wakings while in bed |

|

| 3 | Total Time Asleep at Night, minutes |

336.7 (78.9) | 343.2 (49.6) | 0.69 | Higher scores = more time in bed asleep |

| Sleep Latency, minutes |

44 (65.4) | 27.4 (25.1) | 0.19 | Higher scores = more time in bed before falling asleep |

|

| 4 | Total Time Asleep in 24 hours, minutes |

378.2 (70.1) | 371.3 (43.4) | 0.59 | Higher scores = more time asleep |

| Total Day Time Sleep, minutes |

44.5 (58.7) | 28.1 (36) | 0.34 | Higher scores = more time asleep |

|

P-value from an F-test statistic comparing distributions between the 2 groups (significant P-values are bolded).

The children in the HIV group scored an average of 1 standard deviation below the scores of children in the non-infected group worse outcome on the CHIPASAT components of NDF 2 (P≤0.02) (Table 5) and also performed significantly lower on scores of motor speed (worse outcome) from the Delis-Kaplan Executive Function System (P < 0.05). Two of the three component scores of NDF 3 appeared to be worse for HIV-infected youth (P≤0.05). There were no other significant differences among the other NDFs.

3.3. Bivariate Analyses of Factors: HIV Infection versus ICF, AF, or NDF

All time points (0, 6, 12, and 18-months) were averaged since no significant effects of time were discerned (data not shown). Children with HIV infection had higher levels of ICF-3, which encompasses IFN-γ and TNF-α expression of SEB-stimulated CD4+ and CD8+ T cells, than those of controls (P < 0.01, Table 6). The groups did not differ significantly in sleep factors, but children with HIV infection performed worse than controls in NDF 2 (P < 0.01) and in NDF 3 (P = 0.02). Associations of ICFs with AFs and NDFs and also AFs with NDFs were examined, and potentially significant relationships were subsequently included in the multivariate path analysis (Appendix A.1., A.2., A.3.).

Table 6. Bivariate Analysis: Relationships between HIV Infection, Cytokines, Neurodevelopmental, and Sleep Factors in Adolescents with HIV Infection (Time 0, 6, 12, 18-Months Data).

| Factors | Factor Components | Coefficient | P-Value* |

|---|---|---|---|

| Intracellular cytokine-related factor | |||

| 1 | PMA CD4+ IL-10, PMA CD8+ IL-10, SEB CD4+ IL-10, SEB CD8+ IL-10, US CD4+ IL-10 and US CD8+ IL-10 |

−1.564 | 0.16 |

| 2 | PMA CD4+ 69, PMA CD4+ TNF-α, PMA CD8+ 69 and PMA CD8+ TNF-α |

−5.097 | 0.29 |

| 3 | SEB CD4+ IFN-γ , SEB CD4+ TNF-α, SEB CD8+ IFN-γ and SEB CD8+ TNF-α |

1.283 | < 0.01 |

| 4 | SEB CD8+ 69, US CD4+ 69 and US CD8+ 69 | −0.618 | 0.61 |

| 5 | US CD4+ IFN-γ, US CD8+ IFN-γ and US CD8+ TNF-α | 0.777 | 0.10 |

| 6 | PMA CD4+ IL-12, PMA CD8+ IL-12, SEB CD4+ IL-12 and SEB CD8+ IL-12 |

0.975 | 0.16 |

| Sleep actigraphy-related factors | |||

| 1 | Sleep Efficiency | 1.351 | 0.41 |

| 2 | Average of Number of Awakenings During Night and Total Time Awake at Night |

−5.658 | 0.15 |

| 3 | Difference of Total Time Asleep at Night and Sleep Latency | −16.008 | 0.56 |

| 4 | Average of Total Time Asleep and Total Daytime Sleep | 10.177 | 0.37 |

| Neurodevelopmental factors | |||

| 1 | BRIEF T BRI/MI/GEC & BASC Parent T Externalizing/Internalizing/Behavior/Adaptive |

3.611 | 0.28 |

| 2 | CHIPASAT B/C/D/E & DELIS-KAPLAN Motor Speed | −15.095 | < 0.01 |

| 3 | BRIEF Self T BRI/MI/GEC, BASC Self T Emotional | 8.179 | 0.02 |

| 4 | CMS Stories Immediate/Delayed/Recognition | −0.759 | 0.83 |

| 5 | CPT T Omissions/Hit Reaction/Variability | 2.260 | 0.56 |

Significant P values are bolded

3.4. Multivariate Path Analysis

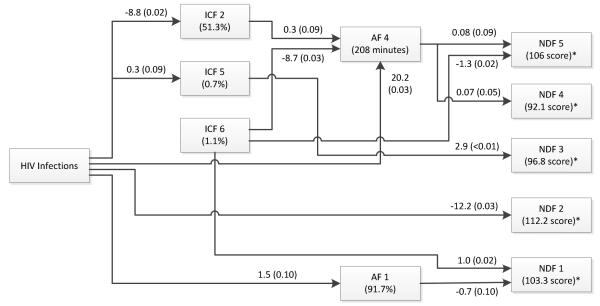

For the multivariate path analysis, assuming that HIV produces immunologic changes that may then affect sleep and neurodevelopmental assessment, the resulting associations were made (Figure 1). Coefficients of change were indicated next to the directional arrows with significance factors (P < 0.10*; P < 0.05**) (see Legend to Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Multivariate path analysis showing the significance of associations between HIV infection and cytokine, sleep, and neurodevelopment factors in HIV-infected youth using all data across all time points (0, 6, 12, and 18-months). Factor associations are indicated by directional arrows that describe the induced changes per unit with the level of significance indicated by P-values in parentheses. For example, HIV infection is associated with a 1) 8.8% decrease in ICF 2 (CD4+ and CD8+ TNF-α), 2) a 20.2 minute increase in AF 4 (total 24 hour sleep and day time sleep), and 3) a 12-point decrease in NDF 2 performance (working memory-mental fatigue). Numbers in parentheses in boxes are the averaged mean values of HIV-infected and control patients. P-values in this Figure have no direct relationship to those in Tables 3-5, but rather to Table 6 and the tables in the Appendix. *Neurodevelopmental test scores normalized to 100. (See Results: Multivariate Path Analysis Section).

HIV infection was associated with decreased** ICF 2 (stimulated CD4+, CD8+ T cell TNF-α and CD69 activation marker expression) and increased* ICF 5 (unstimulated CD4+, CD8+ T cell IFN-γ, TNF-α). HIV infection was also associated with increased** AF 4 (total time asleep and daytime sleep) and increased* AF 1 (sleep efficiency). HIV infection was also linked to worse performance** on the components of NDF 2 (working memory and mental fatigue). ICF 2 was associated with increased* AF 4 and ICF 5 was associated with increased problems** on the components included in NDF 3 (self-reported problems). By itself ICF 6 (stimulated CD4+, CD8+ T cell IL-12) was associated with decreased** AF 4, improved performance** on NDF 5 (sustained concentration and vigilance); and worse performance** on NDF 1 (parent reported problems). In turn, AF 4 was associated with worse performance* on NDF 5 and improved performances** on NDF 4 (verbal memory). AF 1 was associated with fewer problems* on NDF 1.

4. Discussion

The present study of children with HIV infection revealed statistically significant direct and indirect relationships between HIV infection, intracellular cytokine production, sleep duration and efficiency, and neurocognitive and psychosocial function. Greater production of the pro-inflammatory cytokines IFN-γ, IL-12, and TNF-α was associated with alterations in sleep duration which in turn was associated with the ability of HIV-infected patients to perform on neurodevelopment and neurocognitive testing. These interactions between sleep and pro-inflammatory cytokines have also been altered in healthy young adults after acute sleep deprivation or chronic disrupted sleep [38,39]. The central roles of TNF-α, IFN-γ, IL-12, and IL-10 (cytokines measured in our report) in the HIV-induced disorders sleep and subsequent neurocognitive function suggest a potential role of designer drugs that alter their expression (40,41).

In contrast to the one study examining sleep duration in children with HIV infection [21], our study suggests that these patients spent less time awake at night than did controls; however, both studies indicate that these patients have more daytime sleep than do controls. The path analysis also reflected these findings, showing greater sleep efficiency and total time asleep in 24-hours for children with HIV infection. Our data are consistent with other observations that individuals with chronic diseases sleep more than do healthy individuals [4]. Numerous studies have documented the neurocognitive and psychological abnormalities in children with HIV, particularly abnormalities with activated blood lymphocytes, a biomarker for generalized immune activation [42]. The most pronounced differences in this study were seen in working/memory mental fatigue and motor speed (NDF 2). HIV-infected children also had significantly greater difficulty with overall executive functioning particularly in the domain of metacognition (e.g., initiative, working memory, planning, organization, self-monitoring), which is consistent with other reports [43,44].

In the path analysis HIV infection was associated with worse performance on the neurodevelopmental tests included within NDF 2 (memory and mental fatigue). Increased sleep efficiency (AF 1) was associated with fewer problems reported on the components in NDF 1 (parent reported problems). Increased total sleep (AF 4) was associated with worse scores on the tests of sustained concentration and vigilance included in NDF 5 but better performance on verbal memory assessments included in NDF 4. Increased intracellular IL-12 production (ICF 6) was also associated with improved scores on the tests included in NDF 5 (i.e., concentration and vigilance), perhaps countering the opposing effects of AF4.

4.1. Strengths and Weaknesses of the Study

The relatively small number of subjects and 1-year duration of study were adequate for studying the primary endpoints we used (alterations in sleep patterns, cytokine concentrations and neurodevelopment test results). The 4-year period of study did not permit more than a 1-year follow-up of the entire cohort. With these limitations, we included associations between study factors with trend significance (P < 0.10 to P = 0.05) as well as absolute significance (P < 0.05) to indicate the total potential relationship between study factors.

Another drawback to this analysis was that the directional flow of “causation” had to be reasoned by the investigators. This directional flow is necessary to develop the causal model framework for the path analysis. Our findings are important in that we can now begin to hypothesize whether interventions to change cytokine levels and sleep performance can disrupt the impact HIV infection has on neurodevelopmental factors. In some cases, this intervention will be directly on a causal pathway, such as modulating ICF factors and sleep factors. In other cases, manipulating cytokines, such as those in the ICF 6 group (e.g., IL-12) might improve neurodevelopmental endpoints, even though ICF 6 is not directly affected by HIV. Our measurements describe sequential changes in cytokines, sleep disorders, and neurological development and neurocognitive performance that are plausible and consistent with separate studies of these factors in HIV infection. Our multidisciplinary approach has identified possible target areas of therapeutic interventions. Our findings hold pertinence not only for millions of perinatally HIV-infected worldwide youth, but also for the thousands of behaviorally HIV-infected children in developed countries.

4.2. Conclusions of Study

In spite of the limitations of the present study, we propose that there are interconnecting pathways of cytokines, sleep habits, and neurocognitive function in youth with HIV infection (Figure 2). Although treatments of any type were not addressed in this study, it is tempting to believe that they might improve survival and quality of life. At the center of these factor intersections is HIV infection in youth that has associations with inflammatory cytokine responses, altered sleep duration and efficiency, and decreased neurocognition. Each factor, in turn, is associated with alteration with other factors, e.g., inflammatory immune responses with sleep and decreased neurocognition. Preventive treatment strategies could include improved adherence to antiretroviral therapy in order to reduce pro-inflammatory cytokine activation [45-47]. Perhaps a reduction of TNF-α and IFN-γ production would in turn affect total time asleep and improve neurocognition.

Figure 2.

Proposed overall associations between HIV infection, immune responses, sleep disorders, and neurocognition. Assumption of the flow of causation is indicated by the thick (HIV-dependent) arrows. HIV-dependent, immune response-independent and HIV-independent events that influence factors downstream are indicated by the thin arrows at the top of the figure.

Another treatment strategy might be to promote increased sleep duration and alertness among HIV-infected youth. HIV-infected youth appear to require more sleep and to experience more daytime sleepiness than do controls. Promoting good sleep habits to ensure adequate sleep time and providing scheduled naps during the day may diminish the tendency for inappropriate daytime sleep at school or employment, and improve daytime alertness. It is possible that medications promoting alertness might be studied in this population to assess for improvement of daytime neurocognitive function.

Highlights.

HIV infection is associated with changes in cytokines, sleep, and neurocognition.

TNF-α, IFN-γ, and IL-12 appear to impact sleep duration in youth with HIV.

Youth with HIV infection seem to require more daytime sleep than controls.

HIV infection, cytokines and increased sleep may worsen neurocognitive measures

Adherence to HIV drugs and better sleep habits may be treatment strategies for youth.

Acknowledgements

We thank the following for their support of this study: National Institutes of Health National Heart, Lung & Blood Institute (grant RO1-HL075933); The General Clinical Research Center RR-00188 at Texas Children’s Hospital; Texas Children’s Hospital Immunology Research Fund; Christine Cambrice, RN, BSN, Michelle Del Ray, RN, Rene Ali, CCRP, Lawrence Angelina, BS, CPA, Lisa Himic, BA, Louis Pruitt, M.S., Janelle Allen, Janice Hopkins, M. Whitney Ward, M.S., Irene Delgado, M.S., and the parents and children in the study.

Supported by National Institutes of Health grant HL079533, AI36211, RR0188 and the Immunology Research Fund, Texas Children’s Hospital.

ABBREVIATIONS

- AF

actigraphy factor

- BCM

Baylor College of Medicine

- GCRC

General Clinical Research Center

- HCH

Holtz Children’s Hospital

- HIV

human immunodeficiency virus type-1

- ICF

intracellular cytokine factor

- IFN-γ

interferon gamma

- IL

interleukin

- NDF

neurodevelopment factor

- PMA

phorbol myristate acetate

- SEB

staphylococcal enterotoxin B

- TCH

Texas Children’s Hospital

- TNF-α

tumor necrosis factor-alpha

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

The authors declare no conflicts of interest with respect to the contents of this manuscript.

References

- [1].Sondergaard SR, Ostrowski K, Ullum H, et al. Changes in plasma concentrations of interleukin-6 and interleukin-1 receptor antagonists in response to adrenaline infusion in humans. Eur J Applied Physiol. 2000;83:95–8. doi: 10.1007/s004210000257. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [2].Borges-Almeida E, Milanez HM, Vilela MM, et al. The impact of maternal HIV infection on cord blood lymphocyte subsets and cytokine profile in exposed non-infected newborns. BMC Infect Dis. 2011;11:38. doi: 10.1186/1471-2334-11-38. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [3].Wilk A, Urbanska K, Yang S, et al. Insulin-like growth factor-I-forkhead box O transcription factor 3a counteracts high glucose/tumor necrosis factor--mediated neuronal damage: implications for human immunodeficiency virus encephalitis. J Neurosci Res. 2011;89:183–98. doi: 10.1002/jnr.22542. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [4].Cruess DG, Antoni MH, Gonzalez J, et al. Sleep disturbance mediates the association between psychological distress and immune status among HIV-positive men and women on combination antiretroviral therapy. J Psychosom Res. 2003;54:185–9. doi: 10.1016/s0022-3999(02)00501-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [5].Omonuwa TS, Goforth HW, Preud’homme X, et al. The pharmacologic management of insomnia in patients with HIV. J Clin Sleep Med. 2009;5:251–62. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [6].Schouten J, Cinque P, Gisslen M, et al. HIV-1 infection and cognitive impairment in the cART era: a review. AIDS. 2011;25:561–75. doi: 10.1097/QAD.0b013e3283437f9a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [7].Heaton RK, Clifford DB, Franklin DR, Jr, et al. HIV-associated neurocognitive disorders persist in the era of potent antiretroviral therapy: CHARTER Study. Neurology. 2010;75:2087–96. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0b013e318200d727. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [8].Chase C, Ware J, Hittleman J, et al. Women and Infants Transmission Study Group Early cognitive and motor development among infants born to women infected with human immunodeficiency virus. Pediatrics. 2000;106:E25. doi: 10.1542/peds.106.2.e25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [9].Steele RG, Nelson TD, Cole BP. Psychosocial functioning of children with AIDS and HIV infection: review of the literature from a socioecological framework. J Dev Behav Pediatr. 2007;28:58–69. doi: 10.1097/DBP.0b013e31803084c6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [10].Puthanakit T, Aurpibul L, Louthrenoo O, et al. Poor cognitive functioning of school-aged children in Thailand with perinatally acquired HIV infection taking antiretroviral therapy. AIDS Patient Care STDs. 2010;24:141–146. doi: 10.1089/apc.2009.0314. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [11].Wood SM, Shah SS, Steenhoff AP, et al. The impact of AIDS diagnoses on long-term neurocognitive and psychiatric outcomes of surviving adolescents with perinatally acquired HIV. AIDS. 2009;23:1859–65. doi: 10.1097/QAD.0b013e32832d924f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [12].Heaton RK, Franklin DR, Ellis RJ, et al. HIV-associated neurocognitive disorders before and during the era of combination antiretroviral therapy: differences in rates, nature and predictors. J Neurovirol. 2011;17:3–16. doi: 10.1007/s13365-010-0006-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [13].Shanbhag MD, Rutstein RM, Zaoutis T, et al. Neurocognitive functioning in pediatric human immunodeficiency virus infection: effects of combined therapy. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 2005;159:651–6. doi: 10.1001/archpedi.159.7.651. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [14].Pohling J, Zipperlen K, Hollett NA, et al. Human immunodeficiency virus type I-specific CD8+ T cell subset abnormalities in chronic infection persist through effective antiretroviral therapy. BMC Infect Dis. 2010;10:129. doi: 10.1186/1471-2334-10-129. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [15].Yadav A, Fitzgerald P, Sajadi MM, et al. Increased expression of suppressor of cytokine signaling-1 (SOCS-1): A mechanism for dysregulated T helper-1 responses in HIV-1 disease. Virology. 2009;385:126–33. doi: 10.1016/j.virol.2008.11.039. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [16].Hudson LL, Markert ML, Devlin BH, et al. Human T cell reconstitution in DiGeorge syndrome and HIV-1 infection. Semin Immunol. 2007;19:297–309. doi: 10.1016/j.smim.2007.10.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [17].Cagigi A, Mowafi F, Phuong Dang LV, et al. Altered expression of the receptor-ligand pair CXCR5/CXCL13 in B cells during chronic HIV-1 infection. Blood. 2008;112:4401–10. doi: 10.1182/blood-2008-02-140426. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [18].Singh KK, Barroga CF, Hughes MD, et al. Genetic influence of CCR5, CCR2, and SDF1 variants on human immunodeficiency virus 1 (HIV-1)-related disease progression and neurological impairment, in children with symptomatic HIV-1 infection. J Infect Dis. 2003;188:1461–72. doi: 10.1086/379038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [19].Vigano A, Saresella M, Trabattoni D, et al. Growth hormone in T-lymphocyte thymic and postthymic development: a study in HIV-infected children. J Pediatr. 2004;145:542–8. doi: 10.1016/j.jpeds.2004.06.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [20].Franck LS, Johnson LM, Lee K, et al. Sleep disturbances in children with human immunodeficiency virus infection. Pediatrics. 1999;104:e62. doi: 10.1542/peds.104.5.e62. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [21].UNAIDS report on the global AIDS epidemic 2010 Joint United Nations Programme on HIV/AIDS (UNAIDS) 2010 [Google Scholar]

- [22].Wiener LS, Hawes JF, Ng YKW. Psychosocial challenges in pediatric HIV infection. In: Shearer WT, Hanson IC, editors. Medical Management of AIDS in Children. Saunders; Philadelphia: 2003. pp. 373–394. [Google Scholar]

- [23].Foster SB, McIntosh K, Thompson B, et al. Increased incidence of asthma in HIV-infected children treated with highly active antiretroviral therapy in the National Institutes of Health Women and Infants Transmission Study. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2008;122:159–65. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2008.04.043. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [24].Foster SB, Lu M, Thompson B, et al. Association between HLA inheritance and asthma medication use in HIV positive children. AIDS. 2010;24:2133–5. doi: 10.1097/QAD.0b013e32833cba08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [25].Siberry GK, Leister E, Jackson DL, et al. Increased risk of asthma and atopic dermatitis in perinatally HIV-infected children and adolescents. Clin Immunol. 2012;142:201–208. doi: 10.1016/j.clim.2011.10.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [26].Birmaher B, Dahl RE, Williamson DE, et al. Growth hormone secretion in children and adolescents at high risk for major depressive disorder. Arch Gen Psychiatr. 2000;57:867–72. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.57.9.867. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [27].Spiegel K, Leproult R, Colecchia EF, et al. Adaptation of the 24-h growth hormone profile to a state of sleep debt. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol. 2000;279:R874–83. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.2000.279.3.R874. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [28].Reuben JM, Lee BN, Paul M, et al. Magnitude of IFN-gamma production in HIV-1-infected children is associated with virus suppression. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2002;110:255–61. doi: 10.1067/mai.2002.125979. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [29].Lee BN, Follen M, Shen DY, et al. Depressed type 1 cytokine synthesis by superantigen-activated CD4+ T cells of women with HPV related high-grade squamous intraepithelial lesions. Clin Diagn Lab Immunol. 2004;11:239–44. doi: 10.1128/CDLI.11.2.239-244.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [30].Littner M, Kushida CA, Anderson WM, et al. Practice parameters for the role of actigraphy in the study of sleep and circadian rhythms: an update for 2002. Sleep. 2003;26:337–341. doi: 10.1093/sleep/26.3.337. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [31].Lindsey JC, O’Donnell K, Brouwers PM. Methodological issues in analyzing psychological test scores in pediatric clinical trials. J Dev Behav Pediatr. 2000;21:141–151. doi: 10.1097/00004703-200004000-00010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [32].Kline RB. Principles and practice: structural equation modeling. Guilford Press; New York: 1998. [Google Scholar]

- [33].MacCallum R, Browne M, Sugawara H. Power analysis and determination of sample size for covariance structure modeling. Psychol Meth. 1996;1:130–149. [Google Scholar]

- [34].Guttman L. Image theory for the structure of quantitative variables. Psychometrika. 1953;18:277–96. [Google Scholar]

- [35].Kaiser HF, Rice J. Little Jiffy, Mark IV. Edu Psychol Measure. 1974;34:111–117. [Google Scholar]

- [36].Liang KY, Zeger SL. Longitudinal data analysis using generalized linear models. Biometrika. 1986;73:13–22. [Google Scholar]

- [37].Hatcher L. A step-by-step approach to using SAS for factor analysis and structural equation modeling. SAS Institute Inc.; Cary, NC: 1994. pp. 343–436. [Google Scholar]

- [38].Shearer WT, Reuben JM, Mullington JM, et al. Soluble TNF-alpha receptor 1 and IL-6 plasma levels in humans subjected to the sleep deprivation model of spaceflight. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2001;107:165–70. doi: 10.1067/mai.2001.112270. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [39].Shearer WT, Lee BN, Cron SG, et al. Suppression of human anti-inflammatory plasma cytokines IL-10 and IL-1RA with elevation of proinflammatory cytokine IFN-γ during the isolation of the Antarctic winter. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2002;109:854–7. doi: 10.1067/mai.2002.123873. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [40].Besedovsky L, Lange T, Born J. Sleep and immune function. Pflugers Arch - Eur J Physiol. 2012;463:121–37. doi: 10.1007/s00424-011-1044-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [41].Li X, Han X, Llano J, et al. Mammalian target of papamycin inhibition in macrophages of asympotomatic HIV+ persons reverses the decrease in TLR-4–Mediated TNF-α release through P\prolongation of MAPK pathway action. J Immunol. 2011;187:6052–58. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1101532. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [42].Paul ME, Mao C, Charurat M, et al. Women and Infants Transmission Study Predictors of immunologic long-term non-progression in HIV-infected children: implications for initiating therapy. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2005;115:848–55. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2004.11.054. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [43].Ettenhofer ML, Foley J, Behdin N, et al. Reaction time variability in HIV-positive individuals. Arch Clin Neuropsychol. 2010;25:791–8. doi: 10.1093/arclin/acq064. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [44].Sacktor N, Skolasky RL, Cox C, et al. Longitudinal psychomotor speed performance in human immunodeficiency virus-seropositive individuals: impact of age and serostatus. J Neurovirol. 2010;16:335–41. doi: 10.3109/13550284.2010.504249. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [45].Volberding PA, Deeks SG. Antiretroviral therapy and management of HIV infection. Lancet. 2010;376:49–62. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(10)60676-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [46].Malee K, Williams PL, Montepiedra G, et al. The role of cognitive functioning in medication adherence of children and adolescents with HIV infection. J Pediatr Psychol. 2009;34:164–175. doi: 10.1093/jpepsy/jsn068. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [47].Mellins CA, Tassiopoulos K, Malee K, et al. Behavioral health risks in perinatally HIV-exposed youth: co-occurrence of sexual and drug use behavior, mental health problems, and non-adherence to antiretroviral treatment. AIDS Patient Care STDS. 2011;25:413–422. doi: 10.1089/apc.2011.0025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]