Abstract

The Entamoeba histolytica infections result from asymptomatic colonization to variable disease outcomes. However, markers that may predict infection outcomes are not known. Here, we investigated sequence types of a non-coding tRNA-linked locus R-R to identify surrogate markers that may show association with infection outcomes. Among 112 clinical samples -21 asymptomatic, 20 diarrhea/dysentery, and 71 liver abscesses (LA), we identified 11 sequence types. Sequence type 5RR mostly associated with asymptomatic samples, and sequence type 10RR predominantly associated with the symptomatic (diarrhea/dysentery and LA) samples. This is the first report that identifies markers that may predict disease outcomes in E. histolytica.

WHO estimates up to 273 people die everyday world-wide from amebiasis (1), the second leading cause of death due to parasite infection after malaria. However, 4 out of 5 people infected with Entamoeba histolytica, the causative agent of amebiasis, remain asymptomatic (2). In the remaining 20% infections E. histolytica causes intestinal and / or extraintestinal diseases. What determines the outcome of an E. histolytica infection is not clear. Several PCR based polymorphism studies have been undertaken unsuccessfully in the past to find a possible correlation between parasite genotype and outcome of infection (3–7). However, using the tRNA gene-linked multilocus genotyping system, we have previously shown that the parasite genotype is one of the factors determining the infection outcome (8, 9). We have also shown that parasite genotypes in the intestine and in the liver of the same amebic liver abscess (ALA) patients were different from each other, strengthening our previous notion that different genotypes of E. histolytica have different virulence potential (10). However, one caveat of this genotyping system is that it identifies too many genotypes even in a small geographic location. So, a link between individual parasite genotype and the infection outcome could not be established. Here, we extended our investigation on sequence typing of a particular locus, R-R. We chose to study locus R-R, because (i) this was the only locus remained unchanged between the intestinal strain and the LA strain in the same ALA patients (10), suggesting this is more stable than the others, and (ii) it was easy to amplify from clinical samples due to its high copy number (>90) in the genome (11).

A total of 21 asymptomatic (A), 20 diarrhea/dysenteric (D), and 71 liver abscess (LA) DNAs comprised 112 samples of this study. All the A and D samples were from children from Mirpur, Dhaka, and 51 out of the 71 LA samples were from adult ALA patients admitted to different clinics and hospitals in Dhaka, and the remaining 20 LA samples were from patients admitted to the Rajshahi Medical College, Rajshahi, ~250 miles north-west of Dhaka. Amplification of locus R-R was performed using the tRNA primers (9) and PCR product was gel purified, and sequenced directly.

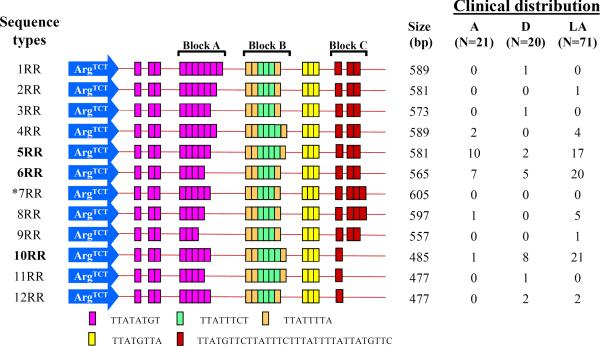

The structure and organization of short tandem repeats (STRs) in locus R-R was previously described (12). A total of 11 locus R-R sequence types (STs) were detected in this study (Fig. 1). Since the LA samples came from two locations – Dhaka and Rajshahi, we first checked the distribution of their STs separately. STs 2RR, 9RR and 12RR, found exclusively in LA samples from Dhaka. Five STs were common in both locations, but no statistically significant differences in their occurrences observed. So, we combined LA samples from both locations for comparison purposes with other clinical groups (Fig. 2). Overall, 5 STs (1RR, 2RR, 3RR, 9RR, and 11RR) were represented by one sample each, suggesting they are rare (Fig. 1). A maximum number of 32 samples displayed the same ST 6RR, which is randomly distributed across all clinical samples (e.g. A = 33.3%, D = 25%, and LA = 28.2%) (Fig. 1 and Fig. 2).

FIG. 1.

Schematic representation of locus R-R sequence types and their distribution in clinical samples. The tRNA gene sequence is shown with arrow and the short tandem repeat sequences (STRs) are shown with colored bars. Three blocks (Block A, Block B and Block C) of STRs showed variability in number of repeats. Among all 112 samples, 11 different locus R-R sequence types were detected. *Sequence type 7RR was not detected in this study population although it was previously identified in a Japanese E. histolytica strain from an individual with unknown clinical manifestation (12). Three most common sequence types (5RR, 6RR, and 10RR) were shown in bold fonts. In the clinical distribution: A = asymptomatic; D = diarrhea/dysentery; LA = liver abscess; and N represents the total number of samples in a particular clinical population. Part of this figure is drawn similar to the Fig 4 in (12).

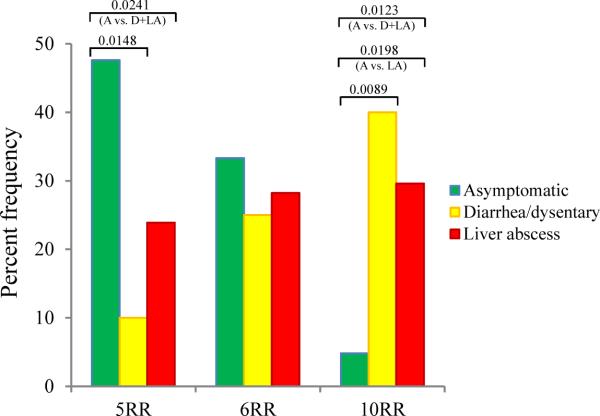

FIG. 2.

Percent frequency of the 3 major locus R-R sequence types among the clinical samples. The sequence type 5RR is significantly associated with the asymptomatic sample group (P-values between asymptomatic & diarrhea/dysentery, asymptomatic & diarrhea/dysentery plus liver abscess sample groups are 0.0148 and 0.0241, respectively). In contrast, the sequence type 10RR is significantly associated with the symptomatic sample group (i.e. diarrhea/dysentery and / or liver abscess sample groups) (P-values between asymptomatic & diarrhea/dysentery, asymptomatic & liver abscess, and asymptomatic & diarrhea/dysentery plus liver abscess sample groups are 0.0089, and 0.0198, and 0.0123, respectively). The sequence type 6RR is distributed almost evenly across all clinical sample groups. A = asymptomatic; D = diarrhea/dysentery; and LA = liver abscess.

ST 5RR was identified in 10 out of 21 (47.6%) A, 2 out of 20 (10.0%) D, and 17 out of 71 (23.9%) LA samples, making it significantly associated with the A strains of E. histolytica (Fig. 2). In contrast, ST 10RR was identified in only 1 out of 21 (4.8%) A samples, 8 out of 20 (40.0%) D, 21 out of 71 (29.6%) LA samples (i.e., 29/91 or 31.9% symptomatic samples), making it significantly associated with the symptomatic strains of E. histolytica. However, three major limitations of this study are: (i) number of A samples was low (N=21) compared to symptomatic samples (D=20 and LA=71; N=91), (ii) all the A and D samples were from 2–6 years old children – so we do not know whether they represent STs for all age groups, although no age-specific sequence or PCR patterns were ever reported in E. histolytica, and (iii) LA samples were from two different epidemiological settings – Dhaka and Rajshahi, although no significant ST differences were noticed between them.

Three major STs - 5RR, 6RR, and 10RR, represented 81.3% (91/112) of all samples. In previous study (8) we obtained 6 distinct PCR patterns in locus R-R among 111 clinical samples (A=38, D=30, and LA=43),. The above 3 STs were detected in 84.7% (94/111) samples. Similarly, in agreement with this study, the 6RR equivalent PCR pattern was the most prevalent of all patterns detected in that study too (8). However, although the 5RR and 10RR equivalent PCR patterns appeared to be proportionately more prevalent in asymptomatic and symptomatic samples, respectively, they did not show statistically significant association. This is because the PCR patterns (sizes) in the previous study were judged by eye (no sequencing was involved), so, not all size estimates were correct. Also, since same size PCR product does not necessarily represent identical sequence (Fig. 1), we believe some of the PCR patterns of previous study (8) are mixture of more than one STs.

Three STs (10RR, 11RR, and 12RR) represented 34/91 or 37.4% of all symptomatic samples, and only 1/21 or 4.8% of all A samples. Although the sample sizes were small, it is still intriguing that they are almost exclusively (34/35 or 97.1%) associated with the symptomatic strains of E. histolytica. Since the size differences of these 3 STs (10RR–12RR: 477–485 bp) to the next ST 9RR (557 bp) are 72–80 bp, a locus R-R PCR product of 485 bp or less will be indicative of a symptomatic infection of E. histolytica. Overall, we are confident that our data would improve our understanding of genotype contribution to the outcome of infection by E. histolytica. Some of STs identified in this exploratory study show promise as surrogate markers for prediction of infection outcome by category B agent of bioterrorism Entamoeba histolytica. Further investigations are required to confirm these findings using larger samples collected from diverse geographic locations.

Acknowledgements

We are grateful to all the study participants and / or their legal guardians for providing the samples. We thank Dr. C. Graham Clark, London School of Hygiene and Tropical Medicine, for critical reading of the manuscript, and constructive comments and suggestions.

This work was supported by a NIH grant R01 AI043596 to WAP.

Footnotes

Transparency Declaration The authors declare no conflict of interest of any nature.

References

- 1.Anonymous WHO/PAHO/UNESCO report. A consultation with experts on amoebiasis. Mexico City, Mexico 28–29 January, 1997. Epidemiol Bull. 1997;18(1):13–4. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Haque R, Mondal D, Karim A, Molla IH, Rahim A, Faruque AS, et al. Prospective case-control study of the association between common enteric protozoal parasites and diarrhea in Bangladesh. Clinical infectious diseases : an official publication of the Infectious Diseases Society of America. 2009;48(9):1191–7. doi: 10.1086/597580. Epub 2009/03/28. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ayeh-Kumi PF, Ali IK, Lockhart LA, Gilchrist CA, Petri WA, Jr., Haque R. Entamoeba histolytica: genetic diversity of clinical isolates from Bangladesh as demonstrated by polymorphisms in the serine-rich gene. Experimental parasitology. 2001;99(2):80–8. doi: 10.1006/expr.2001.4652. Epub 2001/12/26. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ghosh S, Frisardi M, Ramirez-Avila L, Descoteaux S, Sturm-Ramirez K, Newton-Sanchez OA, et al. Molecular epidemiology of Entamoeba spp.: evidence of a bottleneck (Demographic sweep) and transcontinental spread of diploid parasites. Journal of clinical microbiology. 2000;38(10):3815–21. doi: 10.1128/jcm.38.10.3815-3821.2000. Epub 2000/10/04. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Haghighi A, Kobayashi S, Takeuchi T, Masuda G, Nozaki T. Remarkable genetic polymorphism among Entamoeba histolytica isolates from a limited geographic area. Journal of clinical microbiology. 2002;40(11):4081–90. doi: 10.1128/JCM.40.11.4081-4090.2002. Epub 2002/11/01. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Haghighi A, Kobayashi S, Takeuchi T, Thammapalerd N, Nozaki T. Geographic diversity among genotypes of Entamoeba histolytica field isolates. Journal of clinical microbiology. 2003;41(8):3748–56. doi: 10.1128/JCM.41.8.3748-3756.2003. Epub 2003/08/09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Zaki M, Clark CG. Isolation and characterization of polymorphic DNA from Entamoeba histolytica. Journal of clinical microbiology. 2001;39(3):897–905. doi: 10.1128/JCM.39.3.897-905.2001. Epub 2001/03/07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ali IK, Mondal U, Roy S, Haque R, Petri WA, Jr., Clark CG. Evidence for a link between parasite genotype and outcome of infection with Entamoeba histolytica. Journal of clinical microbiology. 2007;45(2):285–9. doi: 10.1128/JCM.01335-06. Epub 2006/11/24. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ali IK, Zaki M, Clark CG. Use of PCR amplification of tRNA gene-linked short tandem repeats for genotyping Entamoeba histolytica. Journal of clinical microbiology. 2005;43(12):5842–7. doi: 10.1128/JCM.43.12.5842-5847.2005. Epub 2005/12/08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ali IK, Solaymani-Mohammadi S, Akhter J, Roy S, Gorrini C, Calderaro A, et al. Tissue invasion by Entamoeba histolytica: evidence of genetic selection and/or DNA reorganization events in organ tropism. PLoS neglected tropical diseases. 2008;2(4):e219. doi: 10.1371/journal.pntd.0000219. Epub 2008/04/10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Clark CG, Ali IK, Zaki M, Loftus BJ, Hall N. Unique organisation of tRNA genes in Entamoeba histolytica. Molecular and biochemical parasitology. 2006;146(1):24–9. doi: 10.1016/j.molbiopara.2005.10.013. Epub 2005/11/26. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Tawari B, Ali IK, Scott C, Quail MA, Berriman M, Hall N, et al. Patterns of evolution in the unique tRNA gene arrays of the genus Entamoeba. Molecular biology and evolution. 2008;25(1):187–98. doi: 10.1093/molbev/msm238. Epub 2007/11/03. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]