Abstract

Endoscopy plays an important role in the diagnosis and management of inflammatory bowel disease (IBD). It is useful to exclude other aetiologies, differentiate between ulcerative colitis (UC) and Crohn’s disease (CD), and define the extent and activity of inflammation. Ileocolonoscopy is used for monitoring of the disease, which in turn helps to optimize the management. It plays a key role in the surveillance of UC for dysplasia or neoplasia and assessment of post operative CD. Capsule endoscopy and double balloon enteroscopy are increasingly used in patients with CD. Therapeutic applications relate to stricture dilatation and dysplasia resection. The endoscopist’s role is vital in the overall management of IBD.

Keywords: Colonoscopy, Oesophagogastroduodenoscopy, Capsule endoscopy, Enteroscopy, Ulcerative colitis, Crohn’s disease, Dysplasia, Endoscopist

INTRODUCTION

Endoscopy is a crucial tool in the management of inflammatory bowel disease (IBD). There is a spectrum of situations when an endoscopy may be of value in IBD, extending from initial diagnosis to differentiating between Crohn’s disease (CD) and ulcerative colitis (UC) to long term management of both conditions.

Of the several endoscopic tools, colonoscopy remains the prime diagnostic tool. Gastroscopy, enteroscopy and endoanal ultrasound scan may be useful in the assessment of specific organ involvement in CD and to differentiate between UC and CD. Novel tools such as capsule endoscopy and double balloon enteroscopy have been playing an increasing role for small bowel Crohn’s disease assessments. Both CD and UC can be complicated by primary sclerosing cholangitis (PSC): ERCP previously the gold standard to diagnose PSC has broadly been superseded by magnetic resonance cholangio pancreatography[1]. This article will focus on the role of colonoscopy in IBD as this is by far the most important tool. A brief overview of other endoscopic tools will follow.

COLONOSCOPY

Over the years, improvements in colonoscope technology have led to more comfortable procedures with better quality image definition (namely narrow band imaging, chromo endoscopy, endomicroscopy and high definition screens)[2]. Training in colonoscopy has optimised the use of this instrument for various diagnostic purposes. Colonoscopy remains the first line endoscopic investigation for suspected CD. Flexible sigmoidoscopy offers a diagnostic option for UC, with colonoscopy reserved to define the disease limit in some cases. The role of colonoscopy in the management of IBD can be summarised as follows[3,4]: (1) to establish a diagnosis; (2) to assess the disease extent and activity; (3) to monitor disease activity; (4) for surveillance of dysplasia or neoplasia; (5) to evaluate ileal pouch and ileorectal anastomosis; (6) to provide endoscopic treatment, such as stricture dilation/stent placement.

COLONOSCOPY AS A DIAGNOSTIC TOOL

One of the pitfalls in diagnosing IBD is the failure to consider other diseases, which may give terminal ileal and colonic inflammation. By far the commonest cause of inflammation is infection. Infective causes[5] are outlined in Table 1; the typical features to assist diagnosis are also described. Other conditions that may mimic IBD[6] with colonic and terminal ileum (TI) inflammation are summarised in Table 2.

Table 1.

Infective causes of inflammation which mimic inflammatory bowel disease

| Infective cause | Endoscopic appearance |

| Salmonella | Friable mucosa with haemorrhages in ileum and colon |

| Shigella | Patchy intense erythema in ileum and colon |

| Campylobacter | Erythema and ulcers in colon |

| E.coli 0157:H7 | Mild to moderately severe colitis |

| Yersinia | Patchy colitis with ileal aphthoid ulcers |

| C.difficile | Pseudo membranes and predominantly left side colitis |

| Klebsiella | Haemorrhagic colitis |

| Mycobacterium | Transverse or circumferential ulcers ileum |

| Neisseria | Proctitis with ulcers and peri anal disease |

| Chlamydia | Peri anal abscess, ulcer and fistula |

| Treponema | Proctitis with ulcers and peri anal disease |

| Schistosoma | Extensive colitis, may be segmental with polyps |

| Entamoeba | Acute colitis and ulcers |

| Herpes | Proctitis with rectal ulcers and perianal disease |

| Cytomegalovirus | Colitis with punched out shallow ulcers |

| Aspergillus | Ulcers with bleeding |

| Histoplasma | Predominantly right side colitis |

Table 2.

Non infective causes of diarrhoea

| Inflammatory | Behcet’s disease |

| Drugs | Non streroidal anti inflammatory drugs |

| Gold | |

| Penicillamine | |

| Iatrogenic | Radiation colitis |

| Vascular | Vasculitis |

| Ischaemic colitis | |

| Neoplastic | Colorectal cancer |

Once these conditions have been excluded there remains the challenge of differentiating between CD and UC. This activity has important implications for disease management and prognosis. Whilst most cases are straightforward, around 5% of cases particularly with colitis, final diagnosis is evasive and the disease is defined as unclassified IBD[7].

Features of UC

The endoscopic findings of active UC range from erythema, loss of the usual vascular pattern due to oedema, granularity of the mucosa and friability/spontaneous bleeding to erosions/ulceration[8] (Figures 1 and 2).

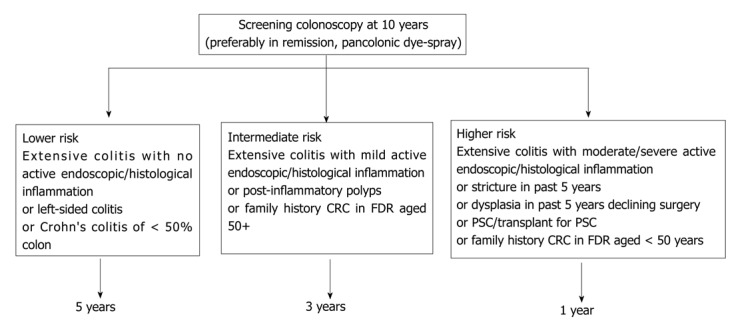

Figure 1.

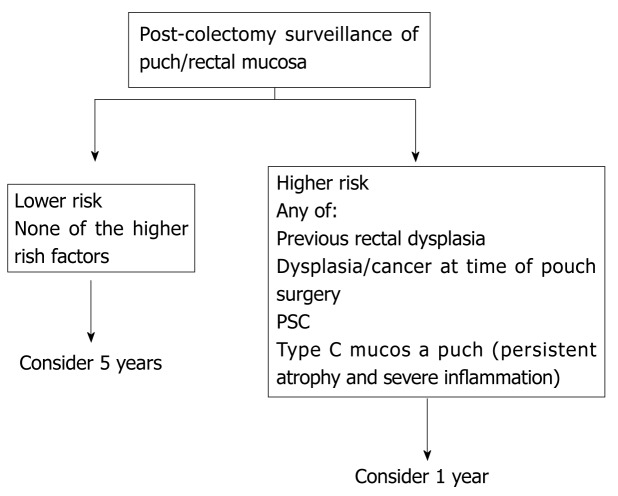

British Society of Gastroenterology guidelines on surveillance of colitis. PSC: Primary sclerosing cholangitis; CRC: Colorectal cancer.

Figure 2.

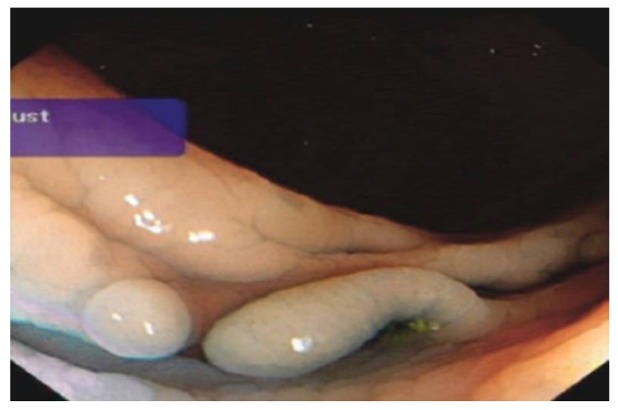

British Society of Gastroenterology surveillance recommandations post colectomy. PSC: Primary sclerosing cholangitis.

The ulceration in UC has typical features: superficial ulcers, which may coalescence to large ulceration extending circumferentially. By virtue of the continuous inflammatory nature of UC, ulcers always surrounded by inflamed mucosa (Figure 3).

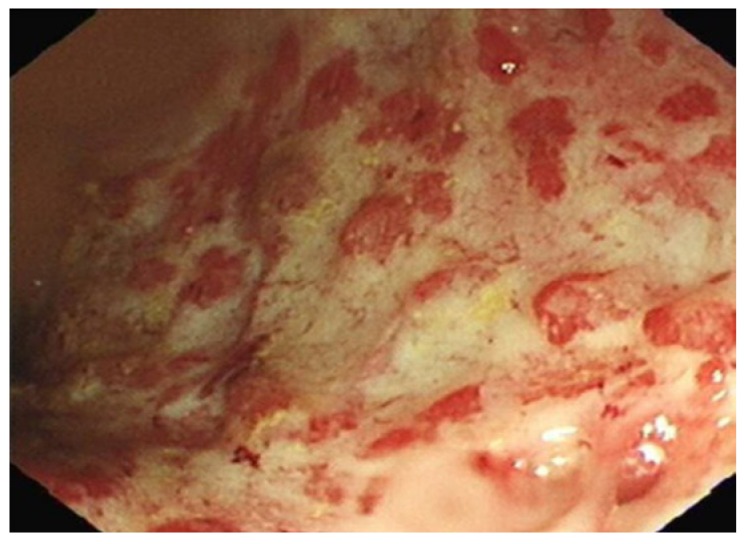

Figure 3.

Severe colitis (Sutherland score 3). Friable, granular mucosa with exudates overlying the surface, ulcers and sub mucosal oedema of rectum.

Distribution of the inflammation may be helpful in differentiating between UC and other causes of colitis particularly Crohn’s colitis. Rectal involvement is invariable with continuous disease extending proximally. Recognised variations to this pattern include rectal sparing, particularly if patients have been using topical therapy, and peri-appendiceal inflammation. Small bowel involvement may occasionally be present in the form of backwash ileitis. This appearance differs from CD: diffuse continuous erythema with no ulceration compared to typical Crohn’s appearance[9]. Endoscopic mucosal appearance alone might underestimate the extent when compared to the histological involvement.

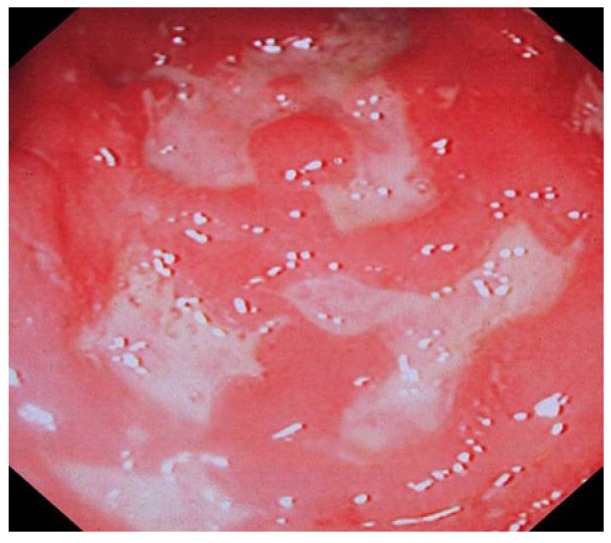

Chronic UC may display quiescent disease but changes of previous activity such as post-inflammatory polyps (Figure 4) scarring (Figure 5) and a shortened tubular colon (Figure 6) may be evident. Strictures are rare in UC; its presence heralds a fivefold risk of colorectal cancer (CRC) and such patients should be followed up with care[10].

Figure 4.

Post inflammatory polyp in transverse colon in a patient with ulcerative colitis.

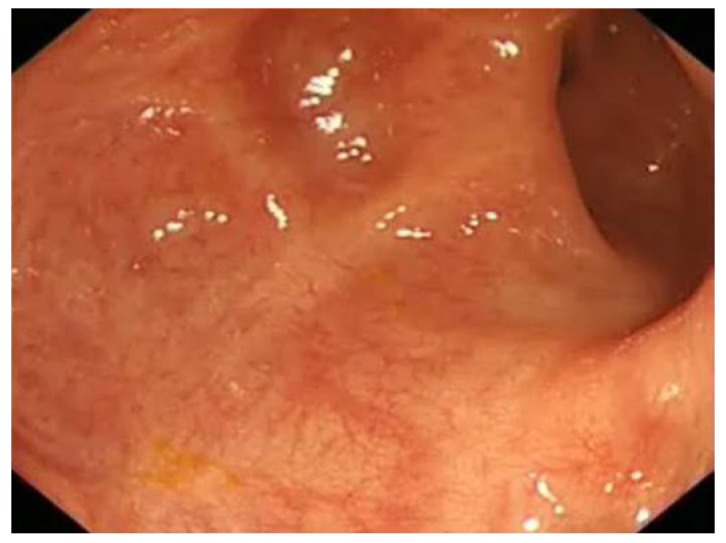

Figure 5.

Extensive scarring of sigmoid colon in a patient with long history of colitis.

Figure 6.

Shortened tubular colon in a patient with pan colitis.

Disease extent and activity influence medical management: this is reflected in the choice of medical therapy and the route of administration as well as risk stratification of colonic cancer[11]. Hence the importance of recording these finding in endoscopic report cannot be underestimated. Disease extent is recorded as the extent of inflammation from the anal verge; mucosal involvement is not static it can progress or regress over time[12]. Disease activity is recorded as mild, moderate or severe with more than 12 disease activity scoring systems reported in the literature[13]. Commonly used endoscopic indices[14-18] are summarised in Table 3. The score used in most drug studies is the Mayo endoscopic score of activity. The Mayo score ranges from 0 to 12, with higher scores corresponding with more severe disease[19]. An “optimal” scoring instrument for UC is still to be developed and will require validation before extensive use in clinical trials can be promoted13].

Table 3.

Endoscopic indices used in ulcerative colitis

| 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | |

| Sutherland | Normal | Mild friability | Moderate friability | Exudates and spontaneous haemorrhages | - |

| Schroeder | Normal or inactive disease | Mild (erythema, decreased vascular pattern) | Moderate (marked erythema, absent vascular pattern) | Severe (spontaneous bleeding, ulceration) | - |

| Baron | Normal: matt mucosa, ramifying vascular pattern, no spontaneous bleeding/to light touch | Abnormal, but non-haemorrhagic: appearances between 0-2 | Moderately haemorrhagic: bleeding to light touch, but no spontaneous bleeding | Severely haemorrhagic: spontaneous bleeding and bleeds to light touch | - |

| Feagan | Normal, smooth, glistening mucosa, with normal vascular pattern | Granular mucosa; vascular pattern not visible; not friable; hyperaemia | As 1, with a friable mucosa, but not spontaneously bleeding | As 2, but mucosa spontaneously bleeding | As 3, but clear ulceration; denuded mucosa |

| Powel- Tuck | Non haemorrhagic, no spontaneous bleeding or bleeding to light touch | Haemorrhagic, no spontaneous bleeding, but bleeding to light touch | Haemorrhagic, spontaneous bleeding ahead of instrument at initial inspection with bleeding to light touch | - | - |

| Lemann, Hanauer | Normal mucosa | Oedema, +/- loss of vascular pattern, granularity | Friability, petechiae | Spontaneous haemorrhage, visible ulcers | - |

Features of Crohn’s disease

Inflammation in CD can involve the entire gastrointestinal tract; 40%-55% of cases show inflammation in the terminal ileum and colon, 15%-25% colonic inflammation alone and in 25%-40% ileum is exclusively involved[20]. Involvement of oesophagus, stomach and proximal small bowel occurs in up to 10% of CD patients. The rectum is spared in up to 50% patients with colonic disease[6].

The endoscopic hallmark of CD is the heterogeneous patchy nature of inflammation or skip lesions (areas of inflammation interposed between normal mucosa). Ulceration in CD commonly occurs on a background of minimal inflammation[5].

CD ulcers tend to be longitudinal, polycyclic ulcers (snail track) associated with cobblestone appearance of ileum, fistulous tract and strictures either in the colonic or ileum. Circumferential inflammation is rare in CD. The ulcers are deep when compared to superficial ulcers in UC[6] (Figure 7).

Figure 7.

Deep ulcers, sub mucosal oedema and haemorrhages in the sigmoid colon in a patient with Crohn’s colitis.

The presence of small ulcerations on the ileocaecal valve or within the TI in a symptomatic individual is highly suggestive of CD (Figure 8); the possibility of tuberculosis and nonsteroidal antiinflammatory drug induced ileal ulcers should be considered[21,22]. Young people may have benign aphthous ulceration related to lymphoid hyperplasia which should not be diagnosed as CD[23].

Figure 8.

Multiple linear, deep ulcers with normal islands of intervening mucosa in the terminal ileum indicates severe Crohn’s disease.

Several activity indices for CD are in use. Most of them are complicated and time consuming. A simple scoring system suitable for clinicians is the simple endoscopic score of CD (SES-CD) which came into use recently. Table 4 summarises the features of SES-CD[24].

Table 4.

Simple endoscopic score for Crohn’s disease

| Variable | Simple endoscopic score | |||

| 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | |

| Size of ulcers | None | Aphthous ulcers | Large ulcers | Very large ulcers |

| Ulcerated surface | None | < 10% | 10%-30% | > 30% |

| Affected surface | Unaffected segment | < 50% | 50%-75% | > 75% |

| Presence of narrowing | None | Single, scope passable | Multiple, scope passable | Scope impassable |

Biopsy specimens should be taken from ulcerated mucosa as well as from normal mucosa adjacent to inflammatory areas, in order to demonstrate the skip phenomenon. Biopsy specimens taken from the edges of ulcers and aphthous erosions maximize the yield of identifying granulomas. The practice of collecting biopsies from macroscopically normal rectal mucosa allows the differentiation between a diagnosis of UC in suspected colonic CD[21,22,25]. Table 5 summarises the prime endoscopic differences between UC and CD[26].

Table 5.

Differences in the macroscopic appearance between Crohn’s disease and ulcerative colitis

| Macroscopic features | UC | CD |

| Erythema | +++ | ++ |

| Loss of vascular pattern | +++ | + |

| Granularity of mucosa | +++ | + |

| Cobble stone appearance | - | ++ |

| Pseudo polyps | +++ | +++ |

| Aphthous ulcers | + | +++ |

| Deep ulcers | - | +++ |

| Patchy inflammation | - | +++ |

| Ileal ulcers | - | +++ |

| Rectal involvement | ++++ | ++ |

UC: Ulcerative colitis; CD: Crohn’s disease.

MONITORING DISEASE ACTIVITY

The use of colonoscopy as a diagnostic tool is non-contentious. Its value in disease monitoring is an evolving indication for the procedure. The thrust in this direction comes from the more recent focus on mucosal healing or reducing inflammatory activity in IBD. The prognostic implications of mucosal healing include reduced surgical intervention[27], prolonged remission[27], and reduced risk of colorectal cancer[10].

Patients with quiescent disease may have a relatively normal appearing mucosa with a distorted vascular pattern but without friability. Mild disease might appear oedematous and granular with distortion of the vascular markings, moderate activity is defined by the presence of a coarse granular pattern, erosions and friability of the mucosa. Severe disease displays gross ulcerations and areas bleed spontaneously[5]. The presence of severe ulceration is usually associated with refractory disease and increased frequency of complications such as perforation[5].

SURVEILLANCE FOR DYSPLASIA OR NEOPLASIA

Several studies have reported an increased risk for colorectal cancer in UC and Crohn’s colitis. This risk has been examined with respect to disease duration and extent[28,29]. The cumulative risk for colorectal cancer was estimated as 1.6%, 8.3% and 18.4% after 10, 20 and 30 years of disease respectively[28]. The associated risk for extent was reported in a population based study as standardised incidence ratio of 2.8 for left sided colitis and 14.8 for pan-colitis[30]. Risk assessment of CRC also critically relies on endoscopic appearance of the severity of disease activity: both endoscopic and histological inflammation was shown to be associated with increased risk[10,31]. Conversely, in a macroscopically normal colonoscopy the associated cancer risk was observed to be similar to age and sex-matched controls[10]. PSC is an independent risk factor for cancer with an odd ratio for developing cancer of 4.49 (95% CI: 3.58-6.41) compared to patients without PSC[32].

As a consequence of the above observations, colonoscopic surveillance for neoplasia is recommended by most gastroenterology and endoscopic societies. The purpose of surveillance colonoscopy is to identify early pre-malignant lesions indicative of an enhanced risk of CRC. The original literature focused on dysplasia-associated lesions/masse (DALM), however we now have evidence that neoplasia may be flat and subtle. The endoscopic techniques for improving dysplasia detection are discussed here in the later section.

FLEXIBLE SIGMOIDOSCOPY

One of the limitations of colonoscopy is the need for oral bowel preparation to enhance adequate mucosal views. In some situations a limited examination of the left colon with flexible sigmoidoscopy may suffice. The procedure may be undertaken following an enema or sometimes-unprepared procedure. Sigmoidoscopy provides useful information in many situations particularly: (1) when colonoscopy is considered high risk or contraindicated e.g., acute severe colitis or fulminant colitis[13]; (2) to define the severity of the disease in established colitis; (3) to exclude superimposed infection with cytomegalovirus (CMV) and C.Difficile; and (4) to exclude other causes for symptoms when there is poor response to therapy e.g., ischaemic colitis.

OESOPHAGO-GASTRODUODENOSCOPY

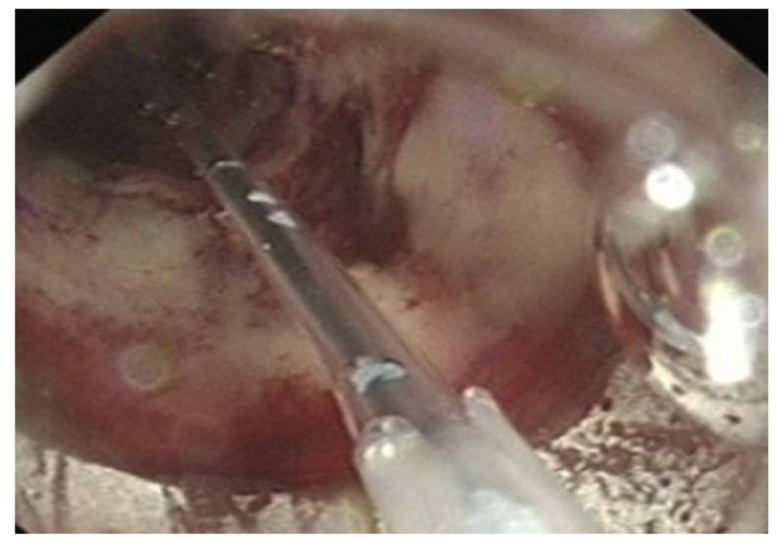

Oesophagogastroduodenoscopy (OGD) in suspected IBD are recommended in paediatric population where differentiating between UC and CD can be challenging[33]. In adult IBD, there are no specific recommendations. Symptoms of dyspepsia, abdominal pain, vomiting or findings of nutritional deficiency in CD warrant an OGD. Upper gastrointestinal (GI) tract involvement occurs in up to 13% of patients with CD[34]. Moreover a minority of UC patients may also have upper GI tract inflammation, manifesting as diffuse duodenitis or gastritis, characterised by oedema, erythema, erosions, and thickened mucosal folds[35]. OGD with small bowel biopsy in patients with IBD include evaluation of concomitant coeliac disease and small bowel adenocarcinoma[36]. There are therapeutic applications of OGD in patients suffering from CD; symptomatic duodenal or pyloric strictures (Figure 9) can be successfully treated with endoscopic balloon dilation[37] (Figure 10).

Figure 9.

Linear pyloric ulcer and surrounding sub mucosal oedema-pyloric Crohn’s disease.

Figure 10.

Balloon dilatation of Crohn’s stricture.

CAPSULE ENDOSCOPY

Small bowel capsule endoscopy (SBCE) was first introduced in 2001. Over the last decade it has evolved as a sensitive modality for the detection of small bowel lesions including CD. The main advantage of SBCE is the potential to visualise the entire length of the small bowel. It is less invasive and better tolerated. When compared to radiological investigations (CT or MR enterography) it is very sensitive to detect early mucosal lesions. Recent study showed the sensitivity for diagnosis of CD of the terminal ileum 100% by SBCE, 81% MR enterography, and 76% by CT enterography, respectively[38,39].

Recent meta-analysis suggested that SBCE has the highest diagnostic yield in non-stricturing CD (69% SBCE vs 30% small bowel Barium follow through) and is significantly superior to the conventional endoscopy or CT/MR enterography for lesion detection. It is particularly useful in patients with established CD to detect disease recurrence[40]. There are drawbacks of SBCE. The main disadvantage is the lack of tissue sampling option. Non-diagnostic mucosal abnormalities may thereafter need to be followed by more invasive (enteroscopy) procedures for histological sampling. Additional drawbacks include obscured view due to debris, non-suitability for patients with delayed transit and the risk of capsule retention in severe stricturing disease[40].

Despite the limitations experts propose capsule endoscopy for monitoring of patients with known diagnosis of Crohn’s disease and in detecting post surgical disease recurrence[41,42]. Costs and availability may however mitigate its value in repetitive testing.

ENTEROSCOPY

Double balloon enteroscopy allows a more complete evaluation of the small intestine than single balloon enteroscopy[43-45]. It complements capsule endoscopy particularly when the diagnosis of IBD is uncertain and biopsies are required and for therapeutic interventions namely dilation of small bowel strictures[43,44].

A recent study examined the value of intra-operative enteroscopy to define mucosal inflammation extent as a means of minimising resection length[46]. Intra operative small bowel endoscopy was performed on 33 occasions in 31 patients with CD to compare intraluminal to external inflammation. Endoscopic findings influenced surgical decisions on 20 of the 33 occasions reducing the length of planned resection in 14 cases.

ROLE OF ENDOSCOPY IN SPECIAL SITUATIONS

Endoscopic surveillance

Surveillance for CRC is indicated for patients with IBD: the risks for UC are similar to Crohn’s colitis of equal colonic extent and disease duration. Endoscopic appearances are a valuable predictor of future dysplasia and CRC[2]. Rutter et al[10] showed that post-inflammatory polyps, strictures, shortened colons and tubular colons were associated with increased risk for future neoplasia with respective odds ratios of 2.14 (95% confidence interval 1.24-3.70), 4.22 (1.08-15.54), 10 (1.17-85.6) and 2.03 (1.00-4.08). No significant association was found with the presence of backwash ileitis, scarring, or a featureless colon.

The British Society of Gastroenterology (BSG) guidelines propose that patients with UC or Crohn’s colitis should have a colonoscopy 10 years after the initial diagnosis to define the extent and activity of the disease[7]. Surveillance colonoscopy should be undertaken preferably in remission. The following risk factors dictated the risk and frequency of future surveillance procedures: disease duration and extent associated primary sclerosing cholangitis, family history of sporadic colorectal cancer, young age at diagnosis and endoscopic and histological appearance during colonoscopy[5,9,10]. Screening interval depends on the above risk factors and according to the national and international guidance. Figures 1 and 2 illustrates the summary of current BSG guidelines[7].

Several studies have shown improved detection rates for dysplasia and cancer if targeted biopsies are taken rather than random biopsies[10]. This approach may serve to mitigate the poor clinician compliance to endoscopic protocols for random biopsies every 10 cm[47]. Narrow band imaging has been shown to be no better than standard white light colonoscopy and hence cannot be recommended as an alternative to chromo endoscopy[7]. Although confocal endomicroscopy may enhance the in vivo characterisation of lesions, it requires prior lesion detection by other means before confocal endomicroscopy can be deployed[2]. Therefore pan colonic dye spray (either with methylene blue or indigo carmine) with targeted biopsies is now recommended[7]. Intuitively such an approach may be expected to be time consuming however the colonoscopy duration was not shown to differ to standard colonoscopy[10]. A recent study by Saunders et al[48] described a time-saving technique using a washer pump for dye spray application: indigo carmine was successfully applied to the entire mucosal surface and reduced the procedural time by several minutes while optimising mucosal views and biopsy access.

Most cancers arise with pan colitis; there is little or no increased risk associated with proctitis and left-sided colitis carries an intermediate cancer risk[13]. There is evidence to indicate that colorectal cancer is also more likely to develop with persistent colonic inflammation even in microscopic level[2]. Hence, active inflammation noted at surveillance colonoscopy, is an indication for escalation of medical treatment.

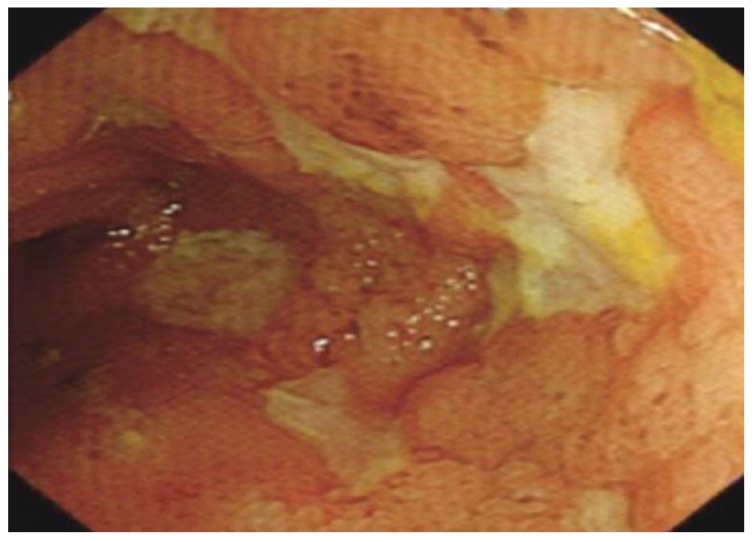

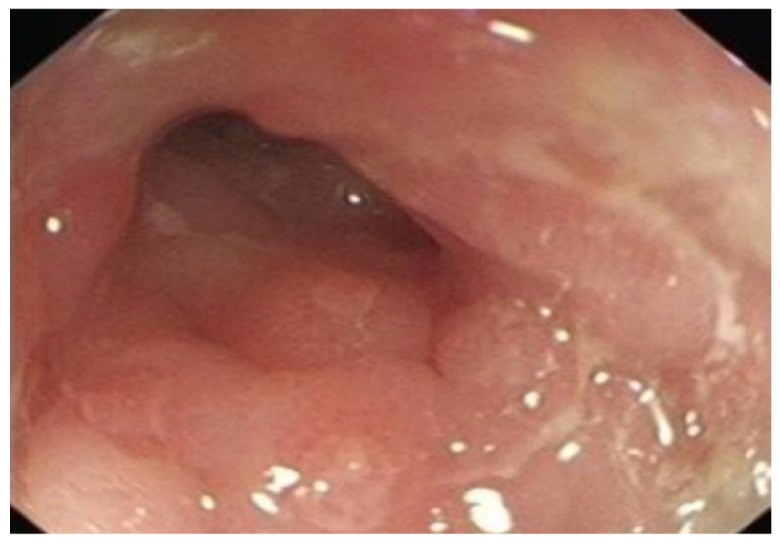

When a dysplastic polyp is detected, it is essential to biopsy the adjacent flat mucosa at the base of the dysplastic polyp to assess the extent of disease and also to detect dysplasia in the surrounding (macroscopically normal) flat mucosa. This may help to differentiate between adenoma-like lesions (ALM) or the traditionally described DALMs[49] (Figures 11 and 12). The swathe of literature pertaining to the management of dysplastic lesions has been summarised in several review articles and lies beyond the scope of this article.

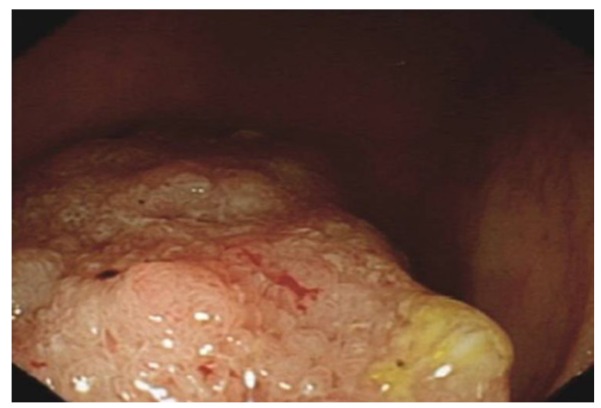

Figure 11.

Dysplasia-associated lesions/masse in caecal pole in a patient with a long history of pancolitis.

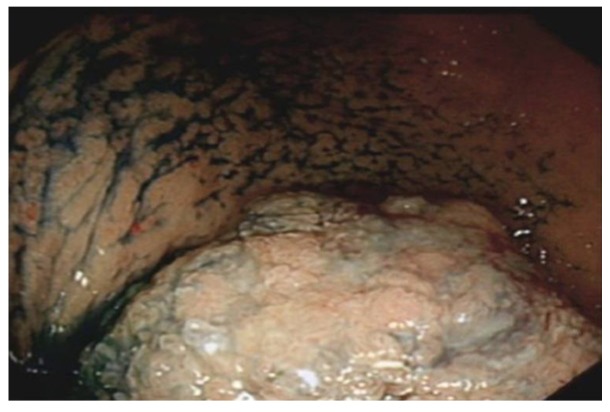

Figure 12.

Dysplasia-associated lesions/masse in caecal pole after dye spray.

Endoscopic assessment of pouchitis

Pouchitis has been reported as a complication of restorative proctocolectomy for UC in as many as 40%-50% of patients[50]. There are no specific symptoms and signs for pouchitis, which may be similar to other pouch complications such as cuffitis, irritable pouch and CD of the pouch. Furthermore, severity of symptoms does not always correlate with the endoscopic or histological findings and the disease activity is variable with time. Therefore a cumulative assessment of clinical, endoscopic and histological assessment is needed to make the diagnosis of pouchitis[51,52].

Pouch endoscopy (pouchoscopy) provides crucial information with respect to the severity and extent of mucosal inflammation, pre-pouch ileitis and CD of pouch and cuffitis. It also demonstrates other abnormalities such as polyps, strictures, sinuses and fistula. Supplemental information from histology may reveal granulomas, CMV inclusion bodies and dysplasia[51,53-59]. Several diagnostic criteria are available and the commonest in clinical use is the pouch disease activity index[60].

Postsurgical crohns disease

Ileal or ileocolonic CD (Montreal L1 or L3) affects 75% of the Crohn’s population[6,20]. In this selected group of patients remission may be achieved by medical or surgical means with a right hemi-colectomy. The latter procedure may also be required for complications particularly strictures and penetrating disease with fistula formation.

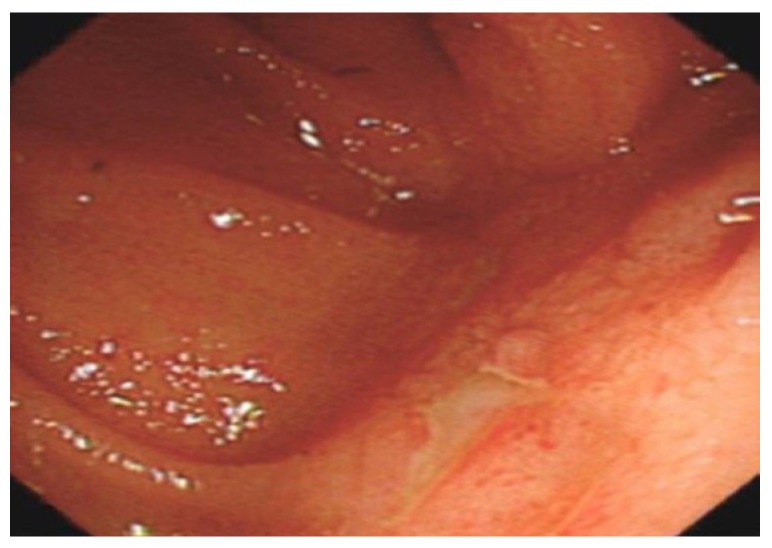

Disease recurrence in the neo-terminal ileum is invariable. Rutgeerts’ group reported endoscopic, clinical and surgical recurrence rates of 73%, 20% and 5% at 1 year respectively[12]. We reported similar rates at our centre for clinical and surgical recurrence in a retrospective series of 99 patients following surgery (28% clinical and 5% surgical recurrence at 1 year)[61]. The Rutgeerts scoring system is proposed as a means to predict post-surgical recurrence risk[62] (Table 6). The predictability of future clinical recurrence was based on neo-terminal ileal endoscopic appearances (Figure 13) at one year, with a greater risk for scores > i2[12].

Table 6.

Rutgeerts scoring system to monitor post surgery Crohn’s disease activity

| Score | Endoscopic features |

| i0 | Absence of any lesions at anastomosis and in the neo terminal ileum |

| i1 | Less than 5 aphthous ulcers (< 5 mm) |

| i2 | More than 5 ulcers with normal intervening mucosa or large patchy lesions, or lesions confined to anastomosis (< 1 cm) |

| i3 | Diffuse aphthous ileitis with diffuse inflammation of the ileal mucosa |

| i4 | Diffuse ileitis with large ulcers, nodularity and stenosis. |

Figure 13.

Aphthous ulcer in the neo terminal ileum in a patient who had ileorectal anastomosis( indicates recurrence of Crohn’s disease). Note healthy surrounding mucosa.

Other clinical and histological risk factors for disease recurrence have been identified. The evidence for smoking is the most compelling[63]. Additional clinical factors are disease behaviour with perforating disease and previous resection for CD. Plexitis in the proximal margin of resection specimens implies more aggressive disease and greater recurrence risk[64].

Post-surgical colonoscopic examination of ileo-colonic anastomosis (Figure 14) is a valuable predictor for risk of recurrence and may identify patients in need of medical therapy escalation. The optimal time interval between surgery and colonoscopy is not known. At our centre we undertake the first colonoscopy at 6 mo. We also proposed a risk stratification of patients based on their risk, with prophylactic medical therapy directed at the risk[65-70]. Figure 3 illustrates the proposed postoperative surveillance strategy.

Figure 14.

Pin hole stricture in the neo terminal ileum (Crohn’s disease).

ROLE OF THE ENDOSCOPIST

Ultimately, it is the endoscopist’s interpretation of endoscopic findings that underpins clinical decisions and not endoscopic technological advances. Other than the appropriate choice of endoscopic test to answer the relevant clinical questions, there is an additional responsibility on the endoscopist to recognise and comprehensively record mucosal abnormalities. By assimilating these findings with the clinical presentation a diagnosis is often achieved and a management plan generated. Emphasis on clear, accurate and systematic reporting is paramount particularly when the endoscopist is not the treating physician. Therefore to ensure accurate communication of findings, a simple check list for reporting diagnostic or prognostic colonoscopies should include the following descriptions.

Mucosal appearance

Appearance should be described in detail focusing on loss of vascular pattern, ulcers size, depth and extent of circumference, haemorrhages and fistula. Distribution of abnormal mucosa should include description of continuous or patchy inflammation, rectal and non-rectal involvement, peri-appendiceal involvement and TI changes.

Disease extent

Describe the extent of disease involvement for instance in UC it is expressed as inflammation distance from the anal verge and in CD length of inflamed segments.

Image labelling

Capture appropriate images of abnormal mucosa and label correctly.

Specimen collection

Collect and correctly label histology specimen. Ensure adequate number of biopsies are taken to increase the yield of histological diagnosis: current consensus is at least two biopsies from five sites including ileum and rectum[7]. Biopsies should be taken from areas of inflammation and the adjacent mucosa proximal to the area of inflammation.

When colonoscopy is undertaken for refractory or acute severe disease the following points must be considered: Alternative diagnosis (ischemia, drug induced, vasculitis, un-related infection); Complications of CD or UC (CMV or Clostridium difficile colitis or neoplasia or fistula formation).

Finally, good communication between endoscopist and histopathologist is mandatory for final decision on diagnosis. This may be achieved through regular multidisciplinary team meeting or attaching the detailed colonoscopy report to all pathology requests.

CONCLUSION

Colonoscopy is one of the most important diagnostic and prognostic tools in the diagnosis and management of IBD. Other endoscopic procedures usually supplement colonoscopy for additional information or treatment of the disease. Management relies on interpretation of endoscopic findings, therefore good knowledge of the various mucosal appearances, descriptions and the implication of each finding, with careful attention to recording each finding is crucial to the optimal management of patients. Surveillance roles for colonoscopy involve optimising the procedure particularly in cancer surveillance and post-operative CD. Therapeutic applications of endoscopy are related to excision of dysplastic lesions and dilatation of strictures.

Footnotes

Peer reviewers: Sherman M Chamberlain, Associate Professor of Medicine, Section of Gastroenterology, BBR-2538, Medical College of Georgia, Augusta, GA 30912, United States; Oscar Tatsuya Teramoto-Matsubara, Med Center, Av. Paseo de las Palmas 745-102, Lomas de Chapultepec, México, 11000, México; Sanjiv Mahadeva, MBBS, MRCP, CCST, MD, Associate Professor, Department of Medicine, Faculty of Medicine, University of Malaya, Kuala Lumpur 50603, Malaysia

S- Editor Yang XC L- Editor A E- Editor Yang XC

References

- 1.Angulo P, Pearce DH, Johnson CD, Henry JJ, LaRusso NF, Petersen BT, Lindor KD. Magnetic resonance cholangiography in patients with biliary disease: its role in primary sclerosing cholangitis. J Hepatol. 2000;33:520–527. doi: 10.1034/j.1600-0641.2000.033004520.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kiesslich R, Goetz M, Lammersdorf K, Schneider C, Burg J, Stolte M, Vieth M, Nafe B, Galle PR, Neurath MF. Chromoscopy-guided endomicroscopy increases the diagnostic yield of intraepithelial neoplasia in ulcerative colitis. Gastroenterology. 2007;132:874–882. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2007.01.048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hommes DW, van Deventer SJ. Endoscopy in inflammatory bowel diseases. Gastroenterology. 2004;126:1561–1573. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2004.03.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Chutkan RK, Scherl E, Waye JD. Colonoscopy in inflammatory bowel disease. Gastrointest Endosc Clin N Am. 2002;12:463–83, viii. doi: 10.1016/s1052-5157(02)00007-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Fefferman DS, Farrell RJ. Endoscopy in inflammatory bowel disease: indications, surveillance, and use in clinical practice. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2005;3:11–24. doi: 10.1016/s1542-3565(04)00441-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Nikolaus S, Schreiber S. Diagnostics of inflammatory bowel disease. Gastroenterology. 2007;133:1670–1689. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2007.09.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Mowat C, Cole A, Windsor A, Ahmad T, Arnott I, Driscoll R, Mitton S, Orchard T, Rutter M, Younge L, et al. Guidelines for the management of inflammatory bowel disease in adults. Gut. 2011;60:571–607. doi: 10.1136/gut.2010.224154. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kiesslich R, Fritsch J, Holtmann M, Koehler HH, Stolte M, Kanzler S, Nafe B, Jung M, Galle PR, Neurath MF. Methylene blue-aided chromoendoscopy for the detection of intraepithelial neoplasia and colon cancer in ulcerative colitis. Gastroenterology. 2003;124:880–888. doi: 10.1053/gast.2003.50146. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Shen B. Endoscopic, imaging and histologic evaluation of Crohn’s disease and ulcerative colitis. Am J Gastroenterol. 2007;102:S41–S45. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Rutter MD, Saunders BP, Wilkinson KH, Rumbles S, Schofield G, Kamm MA, Williams CB, Price AB, Talbot IC, Forbes A. Cancer surveillance in longstanding ulcerative colitis: endoscopic appearances help predict cancer risk. Gut. 2004;53:1813–1816. doi: 10.1136/gut.2003.038505. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Florén CH, Benoni C, Willén R. Histologic and colonoscopic assessment of disease extension in ulcerative colitis. Scand J Gastroenterol. 1987;22:459–462. doi: 10.3109/00365528708991491. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Rutgeerts P, Geboes K, Vantrappen G, Beyls J, Kerremans R, Hiele M. Predictability of the postoperative course of Crohn's disease. Gastroenterology. 1990;99:956–963. doi: 10.1016/0016-5085(90)90613-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.D'Haens G, Sandborn WJ, Feagan BG, Geboes K, Hanauer SB, Irvine EJ, Lémann M, Marteau P, Rutgeerts P, Schölmerich J, et al. A review of activity indices and efficacy end points for clinical trials of medical therapy in adults with ulcerative colitis. Gastroenterology. 2007;132:763–786. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2006.12.038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Sutherland LR, Martin F, Greer S, Robinson M, Greenberger N, Saibil F, Martin T, Sparr J, Prokipchuk E, Borgen L. 5-Aminosalicylic acid enema in the treatment of distal ulcerative colitis, proctosigmoiditis, and proctitis. Gastroenterology. 1987;92:1894–1898. doi: 10.1016/0016-5085(87)90621-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.An oral preparation of mesalamine as long-term maintenance therapy for ulcerative colitis. A randomized, placebo-controlled trial. The Mesalamine Study Group. Ann Intern Med. 1996;124:204–211. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-124-2-199601150-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Baron JH, Connell AM, Lennard-jones JE. Variation between observers in describing mucosal appearances in proctocolitis. Br Med J. 1964;1:89–92. doi: 10.1136/bmj.1.5375.89. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Feagan BG, Greenberg GR, Wild G, Fedorak RN, Paré P, McDonald JW, Dubé R, Cohen A, Steinhart AH, Landau S, et al. Treatment of ulcerative colitis with a humanized antibody to the alpha4beta7 integrin. N Engl J Med. 2005;352:2499–2507. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa042982. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Classen M, Tytgat G N J, Lightdale C J. Endoscopy in inflammatory bowel disease. Gastroenterological endoscopy. 2010;2:625–638. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Schroeder KW, Tremaine WJ, Ilstrup DM. Coated oral 5-aminosalicylic acid therapy for mildly to moderately active ulcerative colitis. A randomized study. N Engl J Med. 1987;317:1625–1629. doi: 10.1056/NEJM198712243172603. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Freeman HJ. Natural history and clinical behavior of Crohn's disease extending beyond two decades. J Clin Gastroenterol. 2003;37:216–219. doi: 10.1097/00004836-200309000-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Pötzi R, Walgram M, Lochs H, Holzner H, Gangl A. Diagnostic significance of endoscopic biopsy in Crohn's disease. Endoscopy. 1989;21:60–62. doi: 10.1055/s-2007-1012901. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ramzan NN, Leighton JA, Heigh RI, Shapiro MS. Clinical significance of granuloma in Crohn's disease. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2002;8:168–173. doi: 10.1097/00054725-200205000-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ganly I, Shouler PJ. Focal lymphoid hyperplasia of the terminal ileum mimicking Crohn's disease. Br J Clin Pract. 1996;50:348–349. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Daperno M, D'Haens G, Van Assche G, Baert F, Bulois P, Maunoury V, Sostegni R, Rocca R, Pera A, Gevers A, et al. Development and validation of a new, simplified endoscopic activity score for Crohn's disease: the SES-CD. Gastrointest Endosc. 2004;60:505–512. doi: 10.1016/s0016-5107(04)01878-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Korelitz BI, Sommers SC. Rectal biopsy in patients with Crohn's disease. Normal mucosa on sigmoidoscopic examination. JAMA. 1977;237:2742–2744. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Llano RC. The role of ileocolonoscopy in inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) Rev Col Gastroenterol. 2010;25:279–80. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Shen B, Fazio VW, Remzi FH, Delaney CP, Bennett AE, Achkar JP, Brzezinski A, Khandwala F, Liu W, Bambrick ML, et al. Comprehensive evaluation of inflammatory and noninflammatory sequelae of ileal pouch-anal anastomoses. Am J Gastroenterol. 2005;100:93–101. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2005.40778.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Eaden JA, Abrams KR, Mayberry JF. The risk of colorectal cancer in ulcerative colitis: a meta-analysis. Gut. 2001;48:526–535. doi: 10.1136/gut.48.4.526. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Ekbom A, Helmick C, Zack M, Adami HO. Increased risk of large-bowel cancer in Crohn's disease with colonic involvement. Lancet. 1990;336:357–359. doi: 10.1016/0140-6736(90)91889-i. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Ekbom A, Helmick C, Zack M, Adami HO. Ulcerative colitis and colorectal cancer. A population-based study. N Engl J Med. 1990;323:1228–1233. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199011013231802. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Gupta RB, Harpaz N, Itzkowitz S, Hossain S, Matula S, Kornbluth A, Bodian C, Ullman T. Histologic inflammation is a risk factor for progression to colorectal neoplasia in ulcerative colitis: a cohort study. Gastroenterology. 2007;133:1099–105; quiz 1340-1. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2007.08.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Soetikno RM, Lin OS, Heidenreich PA, Young HS, Blackstone MO. Increased risk of colorectal neoplasia in patients with primary sclerosing cholangitis and ulcerative colitis: a meta-analysis. Gastrointest Endosc. 2002;56:48–54. doi: 10.1067/mge.2002.125367. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Bousvaros A, Antonioli DA, Colletti RB, Dubinsky MC, Glickman JN, Gold BD, Griffiths AM, Jevon GP, Higuchi LM, Hyams JS, et al. Differentiating ulcerative colitis from Crohn disease in children and young adults: report of a working group of the North American Society for Pediatric Gastroenterology, Hepatology, and Nutrition and the Crohn's and Colitis Foundation of America. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 2007;44:653–674. doi: 10.1097/MPG.0b013e31805563f3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Wagtmans MJ, van Hogezand RA, Griffioen G, Verspaget HW, Lamers CB. Crohn's disease of the upper gastrointestinal tract. Neth J Med. 1997;50:S2–S7. doi: 10.1016/s0300-2977(96)00063-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Valdez R, Appelman HD, Bronner MP, Greenson JK. Diffuse duodenitis associated with ulcerative colitis. Am J Surg Pathol. 2000;24:1407–1413. doi: 10.1097/00000478-200010000-00011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Gillberg R, Dotevall G, Ahrén C. Chronic inflammatory bowel disease in patients with coeliac disease. Scand J Gastroenterol. 1982;17:491–496. doi: 10.3109/00365528209182237. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Matsui T, Hatakeyama S, Ikeda K, Yao T, Takenaka K, Sakurai T. Long-term outcome of endoscopic balloon dilation in obstructive gastroduodenal Crohn's disease. Endoscopy. 1997;29:640–645. doi: 10.1055/s-2007-1004271. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Dionisio PM, Gurudu SR, Leighton JA, Leontiadis GI, Fleischer DE, Hara AK, Heigh RI, Shiff AD, Sharma VK. Capsule endoscopy has a significantly higher diagnostic yield in patients with suspected and established small-bowel Crohn's disease: a meta-analysis. Am J Gastroenterol. 2010;105:1240–128; quiz 1249. doi: 10.1038/ajg.2009.713. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Jensen MD, Nathan T, Rafaelsen SR, Kjeldsen J. Diagnostic accuracy of capsule endoscopy for small bowel Crohn's disease is superior to that of MR enterography or CT enterography. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2011;9:124–129. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2010.10.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Cheifetz AS, Kornbluth AA, Legnani P, Schmelkin I, Brown A, Lichtiger S, Lewis BS. The risk of retention of the capsule endoscope in patients with known or suspected Crohn's disease. Am J Gastroenterol. 2006;101:2218–2222. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2006.00761.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Triester SL, Leighton JA, Leontiadis GI, Gurudu SR, Fleischer DE, Hara AK, Heigh RI, Shiff AD, Sharma VK. A meta-analysis of the yield of capsule endoscopy compared to other diagnostic modalities in patients with non-stricturing small bowel Crohn's disease. Am J Gastroenterol. 2006;101:954–964. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2006.00506.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Lashner BA. Sensitivity-specificity trade-off for capsule endoscopy in IBD: is it worth it? Am J Gastroenterol. 2006;101:965–966. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2006.00513.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Pera A, Bellando P, Caldera D, Ponti V, Astegiano M, Barletti C, David E, Arrigoni A, Rocca G, Verme G. Colonoscopy in inflammatory bowel disease. Diagnostic accuracy and proposal of an endoscopic score. Gastroenterology. 1987;92:181–185. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Mensink PB, Groenen MJ, van Buuren HR, Kuipers EJ, van der Woude CJ. Double-balloon enteroscopy in Crohn's disease patients suspected of small bowel activity: findings and clinical impact. J Gastroenterol. 2009;44:271–276. doi: 10.1007/s00535-009-0011-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Pohl J, May A, Nachbar L, Ell C. Diagnostic and therapeutic yield of push-and-pull enteroscopy for symptomatic small bowel Crohn's disease strictures. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2007;19:529–534. doi: 10.1097/MEG.0b013e328012b0d0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Smedh K, Olaison G, Nyström PO, Sjödahl R. Intraoperative enteroscopy in Crohn's disease. Br J Surg. 1993;80:897–900. doi: 10.1002/bjs.1800800732. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.van Rijn AF, Fockens P, Siersema PD, Oldenburg B. Adherence to surveillance guidelines for dysplasia and colorectal carcinoma in ulcerative and Crohn's colitis patients in the Netherlands. World J Gastroenterol. 2009;15:226–230. doi: 10.3748/wjg.15.226. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Tsiamoulos ZP, Saunders BP. Easy dye application at surveillance colonoscopy: modified use of a washing pump. Gut. 2011;60:740. doi: 10.1136/gut.2010.228296. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Odze RD, Farraye FA, Hecht JL, Hornick JL. Long-term follow-up after polypectomy treatment for adenoma-like dysplastic lesions in ulcerative colitis. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2004;2:534–541. doi: 10.1016/s1542-3565(04)00237-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Fazio VW, Ziv Y, Church JM, Oakley JR, Lavery IC, Milsom JW, Schroeder TK. Ileal pouch-anal anastomoses complications and function in 1005 patients. Ann Surg. 1995;222:120–127. doi: 10.1097/00000658-199508000-00003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Schaus BJ, Fazio VW, Remzi FH, Bennett AE, Lashner BA, Shen B. Clinical features of ileal pouch polyps in patients with underlying ulcerative colitis. Dis Colon Rectum. 2007;50:832–838. doi: 10.1007/s10350-006-0871-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Moskowitz RL, Shepherd NA, Nicholls RJ. An assessment of inflammation in the reservoir after restorative proctocolectomy with ileoanal ileal reservoir. Int J Colorectal Dis. 1986;1:167–174. doi: 10.1007/BF01648445. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Borjesson L, Willen R, Haboubi N. The risk of dysplasia and cancer in the ileal pouch mucosa after restorative proctocolectomy for ulcerative proctocolitis is low: a long-term follow-up study. Colorectal Dis. 2004;6:494–8. doi: 10.1111/j.1463-1318.2004.00716.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.O'Riordain MG, Fazio VW, Lavery IC, Remzi F, Fabbri N, Meneu J, Goldblum J, Petras RE. Incidence and natural history of dysplasia of the anal transitional zone after ileal pouch-anal anastomosis: results of a five-year to ten-year follow-up. Dis Colon Rectum. 2000;43:1660–1665. doi: 10.1007/BF02236846. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Gorgun E, Remzi FH, Manilich E, Preen M, Shen B, Fazio VW. Surgical outcome in patients with primary sclerosing cholangitis undergoing ileal pouch-anal anastomosis: a case-control study. Surgery. 2005;138:631–67; discussion 631-67;. doi: 10.1016/j.surg.2005.07.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Setti Carraro P, Talbot IC, Nicholls RJ. Longterm appraisal of the histological appearances of the ileal reservoir mucosa after restorative proctocolectomy for ulcerative colitis. Gut. 1994;35:1721–1727. doi: 10.1136/gut.35.12.1721. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Veress B, Reinholt FP, Lindquist K, Löfberg R, Liljeqvist L. Long-term histomorphological surveillance of the pelvic ileal pouch: dysplasia develops in a subgroup of patients. Gastroenterology. 1995;109:1090–1097. doi: 10.1016/0016-5085(95)90566-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Gullberg K, Ståhlberg D, Liljeqvist L, Tribukait B, Reinholt FP, Veress B, Löfberg R. Neoplastic transformation of the pelvic pouch mucosa in patients with ulcerative colitis. Gastroenterology. 1997;112:1487–1492. doi: 10.1016/s0016-5085(97)70029-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Coull DB, Lee FD, Henderson AP, Anderson JH, McKee RF, Finlay IG. Risk of dysplasia in the columnar cuff after stapled restorative proctocolectomy. Br J Surg. 2003;90:72–75. doi: 10.1002/bjs.4007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Sandborn WJ, Tremaine WJ, Batts KP, Pemberton JH, Phillips SF. Pouchitis after ileal pouch-anal anastomosis: a Pouchitis Disease Activity Index. Mayo Clin Proc. 1994;69:409–415. doi: 10.1016/s0025-6196(12)61634-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Ng SC, Lied GA, Arebi N, Phillips RK, Kamm MA. Clinical and surgical recurrence of Crohn's disease after ileocolonic resection in a specialist unit. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2009;21:551–557. doi: 10.1097/MEG.0b013e328326a01e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Rutgeerts P, Geboes K, Vantrappen G, Kerremans R, Coenegrachts JL, Coremans G. Natural history of recurrent Crohn's disease at the ileocolonic anastomosis after curative surgery. Gut. 1984;25:665–672. doi: 10.1136/gut.25.6.665. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Reese GE, Nanidis T, Borysiewicz C, Yamamoto T, Orchard T, Tekkis PP. The effect of smoking after surgery for Crohn's disease: a meta-analysis of observational studies. Int J Colorectal Dis. 2008;23:1213–1221. doi: 10.1007/s00384-008-0542-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Ng SC, Lied GA, Kamm MA, Sandhu F, Guenther T, Arebi N. Predictive value and clinical significance of myenteric plexitis in Crohn's disease. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2009;15:1499–1507. doi: 10.1002/ibd.20932. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Ng SC, Kamm MA. Management of postoperative Crohn's disease. Am J Gastroenterol. 2008;103:1029–1035. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2008.01795.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Yamamoto T, Umegae S, Matsumoto K. Impact of infliximab therapy after early endoscopic recurrence following ileocolonic resection of Crohn's disease: a prospective pilot study. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2009;15:1460–1466. doi: 10.1002/ibd.20915. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Sorrentino D, Paviotti A, Terrosu G, Avellini C, Geraci M, Zarifi D. Low-dose maintenance therapy with infliximab prevents postsurgical recurrence of Crohn's disease. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2010;8:591–9.e1; quiz e78-9. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2010.01.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Regueiro M, Schraut W, Baidoo L, Kip KE, Sepulveda AR, Pesci M, Harrison J, Plevy SE. Infliximab prevents Crohn's disease recurrence after ileal resection. Gastroenterology. 2009;136:441–50.e1; quiz 716. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2008.10.051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Sorrentino D, Terrosu G, Avellini C, Maiero S. Infliximab with low-dose methotrexate for prevention of postsurgical recurrence of ileocolonic Crohn disease. Arch Intern Med. 2007;167:1804–1807. doi: 10.1001/archinte.167.16.1804. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Sands BE, Anderson FH, Bernstein CN, Chey WY, Feagan BG, Fedorak RN, Kamm MA, Korzenik JR, Lashner BA, Onken JE, et al. Infliximab maintenance therapy for fistulizing Crohn's disease. N Engl J Med. 2004;350:876–885. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa030815. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]