Abstract

Aims: Genomic research can produce findings unrelated to a study's aims. The purpose of this study was to examine researcher and Institutional Review Board (IRB) chair perspectives on genomic incidental findings (GIFs). Methods: Nineteen genomic researchers and 34 IRB chairs from 42 institutions participated in semi-structured telephone interviews. Researchers and chairs described GIFs within their respective roles. Few had direct experience with disclosure of GIFs. Researchers favored policies where a case by case determination regarding whether GIF disclosure would be offered after discovery, whereas IRB chairs preferred policies where procedures for disclosure would be determined prior to approval of the research. Conclusions: Researcher and IRB chair perspectives on management of GIFs overlap, but each group provides a unique perspective on decisions regarding disclosure of GIFs in research. Engagement of both groups is essential in efforts to provide guidance for researchers and IRBs regarding disclosure of GIFs in research.

Introduction

The general consensus is that an incidental finding (IF) is defined as a finding, outside the study aims, that has potential health or reproductive importance for the research participant (OBBR, 2010). The potential for incidental findings in genomic (GIF) research has increased with the use of genome wide association, microarray, whole genome sequencing, and other technologies that allow interrogation of entire genomes or at least substantial portions of an individual's genome (Caulfield et al., 2008; Kaye et al., 2010). The increased potential for IFs in genomic research coincides with the debate on disclosure of individual research results (IRRs) with health implications to genomic research participants (Wolf et al., 2008; Fabsitz et al., 2010; Meacham et al., 2010; Bredenoord et al., 2011). At this time, there is little guidance for genomic researchers or Institutional Review Boards (IRBs) on management of GIFs identified in research. The focus of our study is on genetic and genomic research and incidental findings. In this paper, for brevity, we refer to both as genomic research.

In general, considerations regarding research related IFs from any research procedures include notifying research participants if information important to clinical care is identified. However, actions regarding IFs with uncertain clinical relevance are less clear (AHC Media, 2008). Consent and confidentiality are important issues that are rooted in the principles of autonomy and beneficence. Additional disclosure issues include discussion of action plans, time to manage the findings, and potential implications for individuals, groups, or communities (Keane, 2008). Researchers may opt to inform participants that IFs with health implications will not be disclosed. However, unresolved issues for researchers include what IFs should be offered, at what time, and by whom (Cho, 2008). There may be a duty for ancillary care in medical research (Belsky and Richardson, 2004; Beskow and Burke, 2010), considered against recognition that the relationship between the researcher and research participant is different than the relationship between the clinician and patient (Cho, 2008). Additional issues in genomic research may include costs of reporting GIFs and follow-up care.

Empirical data are limited on researcher disclosure of GIFs. When researchers were asked what they would do in response to hypothetical situations involving unexpected findings in genetic research, most stated they would disclose IFs, with their decisions governed by quality of information, adherence to rules, and research participant welfare (Meacham et al., 2010). However, only about one-third of researchers who were surveyed about IRB challenges regarding human genetic research identified return of IRRs to participants as an important issue (Edwards et al., 2011).

Suggested guidelines for return of individual results from whole genome research include consideration of the relationship between the researcher and the participant, the existence of an established process, involvement of appropriately trained health professionals (Caulfield et al., 2008), and an informed consent process that addresses individual IFs (Fabsitz et al., 2010). Various options are proposed for categorizing GIFs in research and in clinical testing according to medical importance and other criteria relevant to clinical or personal meaning (Berg et al., 2011; Bredenoord et al., 2011). The U.S. National Heart Lung and Blood Institute (NHLBI) guidelines for disclosure of individual genetic research results (IGRRs) specify that results should be returned, in accordance with state laws, if there are important health implications for the participant, the finding is actionable, the test has analytic validity, and the participant has given consent to receive the IGRR (Fabsitz et al., 2010).

Recommendations have been proposed including the creation of a researcher and IRB pathway for handling IFs at the time of consent, collaboration throughout the duration of the study, and establishing protocols for how disclosure will occur (Van Ness, 2008; Meacham et al., 2010). However, gaps remain regarding how researchers and IRBs can translate these recommendations into policy and practice. The purpose of this study was to examine the current state of U.S. genome researcher and IRB chair opinions and experiences about GIF disclosure. Findings may clarify how researcher and IRB chair perspectives will inform policy development and guidelines for researchers and IRBs who have interdependent roles in protection of human subjects in research.

Materials and Methods

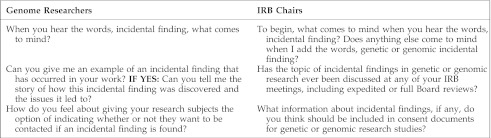

This study was a component of a large exploratory descriptive study described elsewhere (Downing et al., 2011, in preparation; Simon et al., 2011). The entire project was conducted by researchers at the University of Iowa with data collection support from the University of Northern Iowa. The larger study was approved by IRBs at both universities. Researchers and IRB chairs were recruited by letter and email from 147 GWAS-active institutions (Simon et al., 2011). Recruitment letters and/or email invitations were also sent to researchers in the American College of Medical Geneticists and the Heartland Genetics and Newborn Screening Collaborative. Data were collected through a structured interview using open- and closed ended questions (mean=28 min, range 13–52 min) (Fig. 1). Open-ended questions were used to encourage more in-depth responses based on participants' knowledge and experience. All interviews were audiotaped, transcribed, and validated by members of the University of Northern Iowa Center for Social and Behavioral Research. Data were analyzed using conventional content analysis (Hsieh and Shannon, 2005) that uses inductive category development. Two members of the research team analyzed the researcher data and two other members analyzed the IRB chair data. Findings from both analyses were audited by another team member and were regularly reviewed with the entire research team. Data were collected from March to November, 2010. The Researcher and IRB chair interview guides contained 73 and 68 questions respectively. The guides contained the same content, but formatting of items varied according to the target population. The questions were developed by the research team, after a review of the literature focused on IFs, and in consultation with experts on genetic testing, IRB process, and research ethics. Items were reviewed with the survey methodologists at the University of Northern Iowa Center for Social and Behavioral Research, which resulted in formatting edits to clarify intent of each item. Interviews were piloted with researchers and an IRB chair, and interviewers rehearsed the interviews with study team volunteers. After pilot testing, an additional question regarding the management of IFs when the subject is a child was added.

FIG. 1.

Sample interview questions. IRB, institutional review board.

Results

Sample

Fifty-three participants enrolled (Table 1). Seventy percent were male, 94% self identified as White. Although 42% of researchers had encountered GIFs and 68% of IRB chairs had discussed GIFs with their boards, only 3 (16%) researchers and 2 (6%) IRB chairs described individual decisions they had reached regarding disclosure of GIFs to individual research participants.

Table 1.

Participant Background Demographics (n=53)

| |

Genome researcher |

IRB chair |

||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| n | (%) | n | (%) | |

| General characteristics | ||||

| Gender | ||||

| Male | 10 | (52.6%) | 27 | (79.4%) |

| Female | 9 | (47.4%) | 7 | (20.6%) |

| Race/ethnicity | ||||

| White | 19 | (100.0%) | 31 | (91.2%) |

| Other | 0 | (0.0%) | 1 | (2.9%) |

| Missing | 0 | (0.0%) | 2 | (5.9%) |

| Highest academic degree | ||||

| Ph.D. | 10 | (52.6%) | 17 | (50.0%) |

| M.D. | 4 | (21.1%) | 10 | (29.4%) |

| M.D., Ph.D. | 1 | (5.2%) | 1 | (2.9%) |

| Other | 4 | (21.1%) | 6 | (17.6%) |

| University Type | ||||

| State-owned university | 7 | (36.8%) | 15 | (44.1%) |

| Private university | 7 | (36.8%) | 13 | (38.2%) |

| Neither/not a university | 5 | (26.4%) | 6 | (17.6%) |

| Facility Type | ||||

| Clinical | 2 | (10.7%) | 4 | (11.8%) |

| Research | 7 | (36.8%) | 6 | (17.6%) |

| Both | 8 | (42.1%) | 23 | (67.6%) |

| Neither | 1 | (5.2%) | 0 | (0.0%) |

| Missing | 1 | (5.2%) | 1 | (2.9%) |

| Financial Status | ||||

| Nonprofit | 18 | (94.7%) | 33 | (97.1%) |

| For-profit | 1 | (5.3%) | 1 | (2.9%) |

| Researcher characteristics | ||||

| Total years involved in genetic or genomic research | ||||

| >25 years | 6 | (31.6%) | — | |

| 16–25 years | 3 | (15.8%) | — | |

| 11–15 years | 7 | (36.8%) | — | |

| 5–10 years | 3 | (15.8%) | — | |

| <5 years | 0 | (0.0%) | — | |

| Type of research (respondents may check more than one | ||||

| GWAS | 4 | (23.5%) | — | |

| SNP | 6 | (31.6%) | — | |

| WGS | 1 | (05.9%) | — | |

| Molecular-based diagnostic testing | 6 | (18.8%) | — | |

| CMA/Chromosomal analysis | 13 | (40.6%) | ||

| Total GIFs encountered over past 12 months | ||||

| 11–15 | 1 | (5.3%) | — | |

| 6–10 | 3 | (15.7%) | — | |

| 1–5 | 4 | (21.1%) | — | |

| None | 11 | (57.9%) | — | |

| IRB chair characteristics | ||||

| Total years member of current IRB | ||||

| >30 years | — | 1 | (2.9%) | |

| 16–30 years | — | 5 | (14.7%) | |

| 11–15 years | — | 8 | (23.5%) | |

| 5–10 years | — | 16 | (47.1%) | |

| <5 years | 4 | (11.8%) | ||

| IRB type | ||||

| Biomedical | — | 27 | (79.4%) | |

| Behavioral | — | 1 | (2.9%) | |

| Both | — | 6 | (17.6%) | |

| Total GIF discussions at IRB meetings over past 12 months | ||||

| >25 | — | 2 | (5.9%) | |

| 6–10 | — | 2 | (5.9%) | |

| 1–5 | — | 19 | (55.9%) | |

| None | — | 9 | (26.5%) | |

| Missing | — | 2 | (5.9%) | |

IRB, institutional review board; GIF, genomic incidental finding.

Main findings

Researchers and chairs addressed GIFs through the responsibilities and principles relevant to their respective roles. Researcher responses reflected distinctions between generating clinical information and the conduct of research to produce new generalizable knowledge, and IRB chair responses reflected ethical principles and the protection of human subjects. Each had little experience in actual disclosure of GIFs. Both groups expressed opinions regarding whether disclosure should be an option in the informed consent process, and, if there is an option, what information would be considered for disclosure. Although researchers did not express a need for IRB-generated disclosure policies except in rare occasions, IRB chairs described a need for consistent policies regarding GIF disclosure. There was general agreement between the two groups on considerations to be resolved before offering an option of disclosure to research participants, and the need for communication across both groups. Further details are provided in the following paragraphs. These findings are organized by (1) Description of GIFs, (2) Disclosure of GIFs, and (3) Policy perspectives. Supportive participant quotations are provided.

Description of GIFs

Genomic researchers and IRB chairs concurred that GIFs are typically described as unexpected, unrelated to study aims, and may/may not have clinical significance to participants. However, they did not necessarily use these three terms simultaneously or consistently. Each group emphasized different aspects of GIFs. Researchers identified different types of GIFs that may be generated by specific types of tests: “in my world, incidental findings most commonly have to do with nonpaternity”; “a copy number variant that you're unsure is clinically significant or is just a simple benign finding.” IRB chairs tended to consider risks and benefits of GIF to research subjects “sometimes it's medically very important and beneficial, but more often it causes emotional distress, sometimes will cost them money to investigate it further.”

Disclosure of GIFs

Overall, researchers had little direct experience disclosing GIFs to research participants, stating that much of their research was targeted and unlikely to result in GIFs: “right now the kinds of genetic studies that we do are looking at common variants, markers that have no strong relationship to disease.” Researchers provided reasons for not disclosing GIFs. They generally emphasized that the purpose of research was to generate knowledge, and not to provide individual results to participants, including information regarding GIFs: “I wouldn't do it [this is] about research and not about providing them with information about their health”; “I think there's a great risk in going down this road of disclosure. There is a tendency to over disclose. Basically, differentiate between which is research, and medical applications that are medical.”Researchers noted that most research was not conducted in CLIA-certified labs, limiting their ability to provide results for clinical purposes: “we're not in the business of testing people for genetic diseases”; “our lab is not a CLIA (Clinical Laboratory Improvement Amendment) lab.” However, when research resulted in GIFs with clear or probable medical significance, researchers felt compelled to disclose: “We contacted the IRB to see if we could go back to the family because this is something that can sometimes be inherited and we wanted to make the family aware of this possibility.” When the significance of GIFs was unclear, the issue of disclosure was more complicated: “It's a very difficult issue and I don't know what the right answer is. You can sort of see what you would like to do in extreme situations but the majority of situations that are coming to light so far are very equivocal, and you don't know how important they are to the individual.”

Unlike researchers whose responses focused on reasons for and against disclosing GIFs, IRB chairs focused their responses on the consent process and study protocol. They endorsed the idea that researchers should anticipate GIFs prior to study implementation: “I think the better plan would be to have thought about this ahead of time, and this would be part of the informed consent process”; “we're going to try to be proactive and demand that any protocol that has potential for incidental findings come up with a plan that they have to stipulate from the outset as a precondition of approval of their protocol through the IRB, so hopefully we can set the wheels in motion and force the investigators and researchers to have a plan in place, so that when something does come up it doesn't necessarily have to come back through the IRB to get our blessing on how to deal with it”; “I think the IRB should be proactive at the study design stage. I don't think the IRB should be managing individual findings at a result stage.”

However, some would override the subject's wishes if medical opinion determined that disclosure or nondisclosure would be better for the participant from a risk management standpoint”: if somebody has[a] preventable, actionable, and it's a clear cut reproducible finding, then they're going to be told one way or the other. Or, if it's a paternity issue, then they're not going to be told.”

Chairs referred to ethical principles in addressing what should be done: “what comes to mind more, are basic principles of IRBs, in terms of protection of subjects and beneficence, rather than trying to follow a certain policy guideline”; “you've got a moral dilemma and an ethical dilemma, do you respect the person's right not to know or do you tell them?”; “the main drawback is going to be the confidentiality issue.” IRB chairs addressed the participants' right to know information: “If you don't tell the participant it's like the Tuskegee situation where syphilitic patients were not told they could get penicillin, you have to tell the participants everything.” However, like the researchers in this study, IRB chairs also endorsed situations for no disclosure: “the information may not be of any relevance to the individual's health, it may not have CLIA laboratory certification, and therefore is not going to be shared with the individual.”

Policy perspectives

Each group described current or future options regarding IRB institutional policies on disclosure of GIFs. Researchers reported a range of ideas regarding policies. Researchers in this study neither report having formal policies for GIF disclosure, nor did they think policies were necessary if research was unlikely to generate GIFs: “I don't think it would be absolutely completely relevant to what we're doing right now.” Researchers who might encounter GIFs and did not have a policy, thought one would be useful: “I feel like we're working in the dark…It'd be useful to have some sort of codified guidelines to help us.” Some did not anticipate GIFs prior to conducting research: “at the time the consent forms were created, we didn't anticipate that we would be identifying anything that might impact someone's life.” Others had a policy to disclose medically significant GIFs when discovered in research: “we contact the IRB, explain what we found, what might have medical importance. If the IRB grants permission, we send the family a letter offering to meet with them.”

In some cases, IRB chairs reported having a policy that is applied for any IF: “I think honestly there should not be any difference from what we already have, as issues with incidental findings.” Others have no policy: “at this point we don't require anything for genetic incidental findings”; “I think it would be situational, depend a lot on the level of certainty, seriousness of the disease, availability of possible treatment”; “We've sort of been stymied because we've been looking for literature for guidance and to try to come up with…try to adopt a way for some sort of national position or standards to be developed and there really hasn't been.” When asked what should be considered, each group offered topics for GIF disclosure policies (Fig. 2).

FIG. 2.

Researcher and IRB chair topics GIF disclosure policies. GIF, genomic incidental finding.

Discussion

This study reports opinions and experiences of genomic researchers and IRB Chairs regarding descriptions of GIFs, GIF disclosure options, and policies regarding disclosure of GIFs to research subjects. Researchers and IRB chairs each have useful information that can contribute to the development of guidelines for return of GIFs to individual research subjects. Description of GIFs by each group suggests that researchers and IRB chairs may consider different aspects of GIFs when determining whether or how to disclose. Findings from this study provide evidence regarding current viewpoints of researchers in which a plan for disclosure of IRRs may be contingent on the genotyping method, medical significance of the specific finding, the participant preferences, and viewpoints of IRB chairs on need for guidance for disclosure of GIFs from genetic research studies. This evidence builds on the findings from Edwards et al. (2011) in which return of results was not a common finding. Edwards et al. also noted that those researchers who had served on IRBs were more likely to report positive consequences of IRB review. Findings from the current study support a need to create opportunities for collaboration among researchers, IRB chairs, and IRB professionals when examining policies regarding disclosure of GIFs. Clarity in definitions of terms and issues surrounding disclosure are topics for which collaborative efforts, as suggested by Lemke et al. (2010), may yield positive results.

Results from our study identify topics that require further examination. First, whether statements regarding GIF disclosure procedures should be described in the informed consent process prior to IRB review. Researchers expressed a wide range of views on whether a plan was needed and if so, what the elements should contain. In some instances, researchers may prefer to look at what genomic research method is used, or prefer to evaluate individual cases after a GIF is identified, rather than plan for a policy for return of GIFs across genomic research studies. However, IRB chairs were in general agreement on the need for a plan regarding disclosure of GIFs that would be included in the informed consent process. Within a disclosure protocol, IRB chairs generally supported allowing research participants to make the decision of whether to receive the information about GIFs. Other topics will need to be addressed in the plan, beyond the act of disclosure, to address referrals for additional services to provide follow-up evaluation and health care related to the results, and to address cost and access to these services. These topics may be an important starting point for communication at the institutional level regarding potential disclosure of GIFs in genomic research.

Second, at what point disclosure is to be discussed with research participants, and how this would occur. Findings from IRB chairs in this study endorse the goal that a GIF disclosure plan be included in the informed consent process (Simon et al., 2011). However, even if the subject agrees that s/he would like to receive GIFs, other issues such as who would be best qualified to discuss the GIF with a research subject may require attention.

One limitation of this study was that interview questions did not specifically request information on the multiple, different research contexts within which GIFs may arise. Management of GIFs continues to be examined by numerous scholars (Dressler, 2009; Beskow and Burke, 2010; Ramoni et al., 2011; Wolf, 2011). Beskow and Burke (2010) propose assessing the depth of the relationship and the vulnerability of the research subjects. Wolf (2011) notes that researcher relationships can include more immediate contact with research subjects when they conduct the informed consent process and/or analyze the specimens themselves, or a more distant relationship such as when the researcher has had no personal contact with the research subject, for example when conducting secondary analyses.

Strengths of this study include the use of selected open-ended questions that elicited participant perspectives, language, and exemplars, in addition to specific issues regarding disclosure of GIFs from genomic researchers and IRB chairs. Another strength was that the sample exceeded that needed to reach data saturation, which is the primary determinate of sample size in qualitative analysis. However, the sample may not be representative of the larger genomic research or IRB chair communities.

Conclusion

This study highlights the need for communication across stakeholder groups to clarify policies and guidelines for management of GIFs. While there was some agreement on issues between researchers and IRB chairs, efforts are needed to address differences in their viewpoints as a means to reach consensus. Throughout this process, the viewpoints of research participants will also be needed.

Acknowledgments

The study was supported by the National Human Genome Institute (RC1HG005786). The authors thank the American College of Medical Genetics and the Heartland Regional Genetics and Newborn Screening Collaborative for assistance in recruitment; and the University of Northern Iowa Center for Social and Behavioral Research for data collection.

Disclosure Statement

No competing financial interests exist for all authors. This publication was made possible by Grant Number TL1RR024981 (training support for DB) from the National Center for Research Resources (NCRR), a part of the National Institutes of Health (NIH). Its contents are solely the responsibility of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official views of the CTSA or NIH.

References

- AHC Media. Does your IRB have a plan for handling incidental findings? IRB Advisor [newsletter] 2008;8:1–4. [Google Scholar]

- Belsky L. Richardson HS. Medical researchers' ancillary clinical care responsibilities. BMJ. 2004;328:1494–1496. doi: 10.1136/bmj.328.7454.1494. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berg JS. Khoury MJ. Evans JP. Deploying whole genome sequencing in clinical practice and public health: meeting the challenge one bin at a time. Genet Med. 2011;13:499–504. doi: 10.1097/GIM.0b013e318220aaba. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beskow LM. Burke W. Offering individual genetic research results: context matters. Sci Transl Med. 2010;2:1–5. doi: 10.1126/scitranslmed.3000952. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bredenoord AL. Kroes HY. Cuppen E, et al. Disclosure of individual genetic data to research participants: the debate reconsidered. Trends Genet. 2011;27:41–47. doi: 10.1016/j.tig.2010.11.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Caulfield T. McGuire AL. Cho M, et al. Research ethics recommendations for whole-genome research: consensus statement. PLoS Biol. 2008;6:e73. doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.0060073. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cho MK. Understanding incidental findings in the context of genetics and genomics. J Law Med Ethics. 2008;36:280–285. doi: 10.1111/j.1748-720X.2008.00270.x. 212. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dressler LG. Disclosure of research results from cancer genomic studies: state of the science. Clin Cancer Res. 2009;15:4270–4276. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-08-3067. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Edwards KL. Lemke AA. Trinidad SB, et al. Attitudes toward genetic research review: results from a survey of human genetics researchers. Public Health Genomics. 2011;14:337–345. doi: 10.1159/000324931. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fabsitz RR. McGuire A. Sharp RR, et al. Ethical and practical guidelines for reporting genetic research results to study participants: updated guidelines from a National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute working group. Circ Cardiovasc Genet. 2010;3:574–580. doi: 10.1161/CIRCGENETICS.110.958827. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hsieh HF. Shannon SE. Three approaches to qualitative content analysis. Qual Health Res. 2005;15:1277–1288. doi: 10.1177/1049732305276687. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaye J. Boddington P. de Vries J, et al. Ethical implications of the use of whole genome methods in medical research. Eur J Hum Genet. 2010;18:398–403. doi: 10.1038/ejhg.2009.191. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Keane MA. Institutional review board approaches to the incidental findings problem. J Law Med Ethics. 2008;36:352–355. doi: 10.1111/j.1748-720X.2008.00279.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lemke AA. Trinidad SB. Edwards KL, et al. Attitudes toward genetic research review: results from a national survey of professionals involved in human subjects protection. J Empir Res Hum Res Ethics. 2010;5:83–91. doi: 10.1525/jer.2010.5.1.83. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meacham MC. Starks H. Burke W, et al. Researcher perspectives on disclosure of incidental findings in genetic research. J Empir Res Hum Res Ethics. 2010;5:31–41. doi: 10.1525/jer.2010.5.3.31. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Office of Biorepositiories and Biospecimen Research [OBBR] Workshop on release of research results to participants in biospecimen studies. 2010. http://biospecimens.cancer.gov/global/pdfs/NCI_Return_Research_Results_Summary_Final-508.pdf. [Jul 25;2011 ]. http://biospecimens.cancer.gov/global/pdfs/NCI_Return_Research_Results_Summary_Final-508.pdf

- Ramoni R. McGuire A. Morley D, et al. Attitudes and Practices of Genome Investigators Regarding Return of Individual Genetic Test Results. Paper presented at: presentation exploring the ELSI universe: ethical, legal, & social implications; Apr 12–14;; Chapel Hill, NC. 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Simon C. Williams JK. Shinkunas L, et al. Informed consent and genomic incidental findings: IRB chair perspectives. J Empir Res Hum Research Ethics. 2011;6:53–67. doi: 10.1525/jer.2011.6.4.53. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van Ness B. Genomic research and incidental findings. J Law Med Ethics. 2008;36:292–297. doi: 10.1111/j.1748-720X.2008.00272.x. 212. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wolf SM. New Developments in Governance and Oversight [plenary]. Paper presented at: presentation exploring the ELSI universe: ethical, legal, & social implications; Apr 12–14;; Chapel Hill, NC. 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Wolf SM. Lawrenz FP. Nelson CA, et al. Managing incidental findings in human subjects research: analysis and recommendations. J Law Med Ethics. 2008;36:219–248. doi: 10.1111/j.1748-720X.2008.00266.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]