Abstract

Recent studies have established that amplification of the MET proto-oncogene can cause resistance to epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR) tyrosine kinase inhibitors (TKIs) in non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC) cell lines with EGFR-activating mutations. The role of non-amplified MET in EGFR-dependent signaling before TKI resistance, however, is not well understood. Using NSCLC cell lines and transgenic models, we demonstrate here that EGFR activation by either mutation or ligand binding increases MET gene expression and protein levels. Our analysis of 202 NSCLC patient specimens was consistent with these observations: levels of MET were significantly higher in NSCLC with EGFR mutations than in NSCLC with wild-type EGFR. EGFR regulation of MET levels in cell lines occurred through the hypoxia-inducible factor (HIF)-1α pathway in a hypoxia-independent manner. This regulation was lost, however, after MET gene amplification or overexpression of a constitutively active form of HIF-1α. EGFR- and hypoxia-induced invasiveness of NSCLC cells, but not cell survival, were found to be MET dependent. These findings establish that, absent MET amplification, EGFR signaling can regulate MET levels through HIF-1α and that MET is a key downstream mediator of EGFR-induced invasiveness in EGFR-dependent NSCLC cells.

Keywords: EGFR, MET, non-small cell lung cancer, HIF-1α, invasiveness

Introduction

Non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC) is the leading cause of cancer death in the United States. Epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR)-activating mutations have been described in a subset of NSCLC patients, and activated EGFR is known to influence tumor cell survival, proliferation, angiogenesis, and invasiveness (Lynch et al., 2004; Paez et al., 2004; Pao et al., 2004; Janne et al., 2005; Pao and Miller, 2005; Ciardiello and Tortora, 2008). EGFR tyrosine kinase inhibitors (TKIs) such as erlotinib and gefitinib are clinically active in 10–20% of NSCLC patients (Fukuoka et al., 2003; Kris et al., 2003; Shepherd et al., 2005; Thatcher et al., 2005). Activating mutations within the EGFR tyrosine kinase domain including an amino acid substitution at exon 21 (L858R) and in-frame deletions in exon 19 were found to be predictors of clinical response to EGFR TKIs (Lynch et al., 2004; Paez et al., 2004; Pao et al., 2004).

Recent evidence suggests that in NSCLC cells activating EGFR mutations or amplification of the MET proto-oncogene caused acquired resistance to EGFR TKIs by driving activation of the PI3K pathway (Engelman et al., 2007). The role of MET in EGFR-dependent signaling before the emergence of TKI resistance is not well understood; however, MET is regulated by hypoxia and hypoxia-inducible factor-1α (HIF-1α) and is thought to contribute to invasive tumor growth (Pennacchietti et al., 2003). The MET protein is a receptor tyrosine kinases whose activation can cause malignant transformation and tumorigenesis (Cooper et al., 1986; Park et al., 1987; Stabile et al., 2004). Upon ligand binding, MET activates downstream signaling molecules including PI3K, Src, and signal transducer and activator of transcription-3 (Rosario and Birchmeier, 2003), triggering the key metastatic steps of cell dissociation (Qiao et al., 2002), migration (Yi et al., 1998), and invasion (Bredin et al., 2003). MET is overexpressed in multiple malignancies and is associated with aggressive disease (Peruzzi and Bottaro, 2006). In NSCLC, MET levels are elevated in resected tumors compared with normal tissue (Liu and Tsao, 1993; Ichimura et al., 1996; Olivero et al., 1996), and high expression of the MET ligand hepatocyte growth factor (HGF) is associated with aggressive disease and a poor prognosis (Siegfried et al., 1998).

Recent studies have suggested a link between EGFR signaling and MET. Expression and phosphorylation of EGFR and MET correlate in multiple malignancies (Weinberger et al., 2005). Aberrant EGFR activation results in elevated MET phosphorylation in thyroid carcinoma cells (Bergstrom et al., 2000). EGFR function has been implicated in HGF-induced hepatocyte proliferation (Scheving et al., 2002) and is required for MET-mediated colon cancer cell invasiveness (Pai et al., 2003). Recent studies of phosphoprotein networks reveal an association between EGFR and MET activation (Huang et al., 2007; Guo et al., 2008), and have reported direct crosstalk between EGFR and the MET (Jo et al., 2000; Huang et al., 2007).

A plausible link between the EGFR and MET pathways is HIF-1, which has two subunits (HIF-1α and HIF-1β), and is known to contribute to tumor cell motility and invasiveness. EGF has been shown to modulate HIF-1α levels in prostate, breast, and lung cancer cell lines (Zhong et al., 2000; Phillips et al., 2005; Peng et al., 2006), and positive correlations between EGFR and HIF-1α expression have been observed in NSCLC (Hirami et al., 2004; Swinson et al., 2004).

Here, we have used clinical specimens, transgenic mouse models, and cell lines to investigate the hypothesis that EGFR signaling may regulate MET levels through HIF-1α but that MET amplification, which occurs in EGFR TKI resistance, would uncouple MET levels from EGFR regulation. We hypothesized further that EGFR-induced invasiveness, like hypoxia-induced invasiveness, is mediated downstream at least in part by the HIF-1α/MET axis.

Results

EGFR-activating mutations are associated with elevated levels of MET in NSCLC clinical samples

To investigate a possible association between EGFR activation and MET in clinical specimens, we evaluated MET levels by immunohistochemistry and assessed EGFR mutations in 202 human NSCLC clinical specimens. Out of 202 samples, 22 had detectable EGFR mutations. Specimens were immunostained for MET and scored based on an intensity score (0, 1, 2, or 3) and an extension percentage. The final score was the product of these two values. The mean score for MET expression was 39.46 ± 64.52. Therefore, a score of 40 was considered the cutoff for classifying low and high levels of MET expression. The mean MET expression score was significantly higher in specimens with mutated EGFR (73.64 ± 70.68) than in specimens with WT EGFR (48.72 ± 71.72; P = 0.04; Figure 1a). Furthermore, 37% of NSCLC tumors with WT EGFR expressed high levels of membranous MET, whereas 68% of NSCLC tumors with mutated EGFR expressed high levels of membranous MET (P = 0.005; Figure 1b). Among adenocarcinomas with EGFR-activating mutations, we did not observe any association between EGFR expression and survival. However, considering the small sample size, no definitive conclusions can be drawn.

Figure 1.

Elevated MET and HGF expression correlates with EGFR-activating mutations in NSCLC tumor samples. NSCLC clinical specimens (n = 202) were immunostained with anti-MET ab and scored (a). EGFR-activating mutations correlated with elevated levels of MET. Bars, s.e.m.; *P < 0.05. (b) Data are presented as the percentage of tumors with high MET expression; **P < 0.005. (c). Murine lung tumors driven by K-RAS or EGFR-activating mutations were immunostained with anti-MET ab, and positive staining was quantified. Weak or negative MET staining was observed in K-RAS-driven tumors, whereas tumors with EGFR-activating mutations exhibited elevated MET expression. Erlotinib treatment diminished MET expression. Representative images are shown. Columns, mean score; bars, s.e.m. *P < 0.001.

EGFR activation modulates MET expression in transgenic murine models of NSCLC

We investigated whether a similar association between EGFR-activating mutations and MET expression occurred in murine models of NSCLC. We used transgenic mice with lung tumors driven by lung-specific mutated K-RAS or activating EGFR mutation (Forsythe et al., 1996; Johnson et al., 2001). Lung tumor sections were immunostained for MET and scored as described above. K-RAS-driven lesions had an average score of 6.75, whereas tumors with EGFR-activating mutations had an average staining score of 40.65 (Figure 1c; P < 0.001). Treatment of mice bearing EGFR-driven lung tumors with the EGFR TKI erlotinib (50 mg/kg/day) for 48 h abolished MET, providing evidence that MET levels were regulated by EGFR activation.

EGFR-activating mutations are associated with elevated HIF-1α and MET levels in NSCLC cell lines

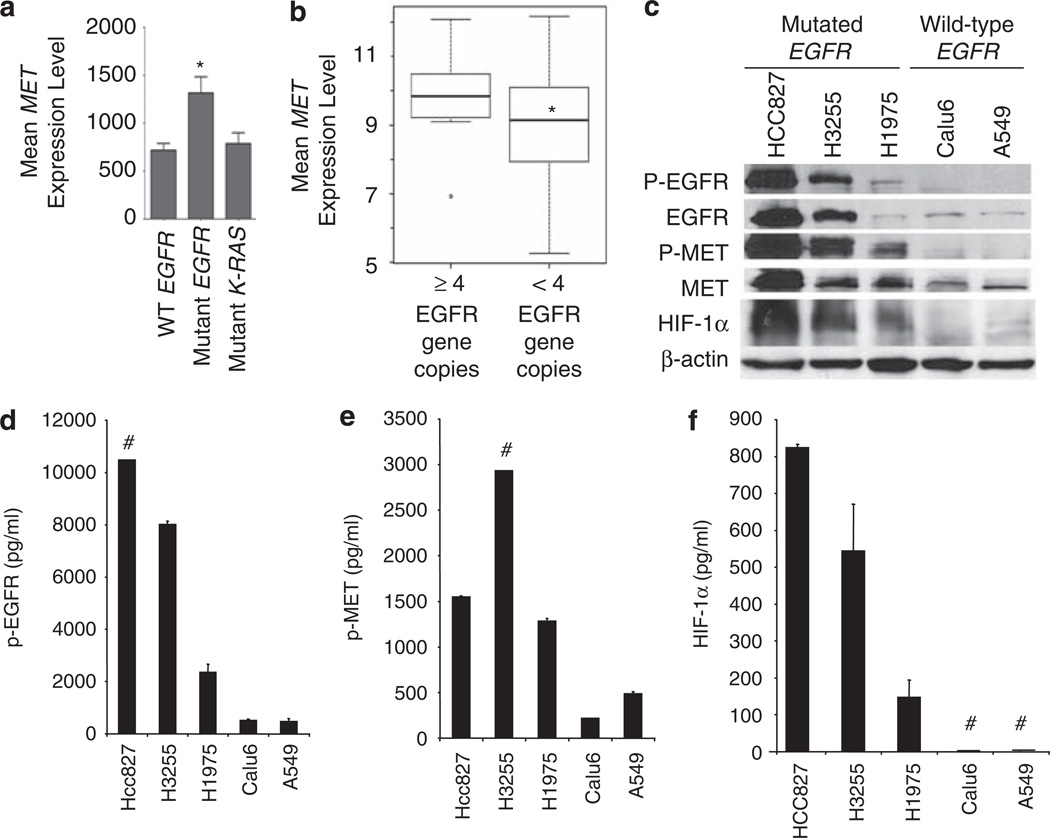

Given our finding that tumors with EGFR mutations exhibit higher MET expression, we investigated MET regulation by EGFR and its role in EGFR-mediated NSCLC invasiveness. We evaluated MET RNA levels in NSCLC cell lines by performing gene expression analysis on gene arrays of 53 previously characterized NSCLC lines (eight lines with mutated EGFR) (GEO 4824) (Zhou et al., 2006). MET RNA levels were significantly higher in EGFR-mutated cell lines than in NSCLC cell lines expressing WT EGFR (Figure 2a; P = 0.002); however, MET expression levels in cell lines with K-RAS mutations were not significantly different compared with cell lines with WT K-RAS.Moreover, we observed a significant association between EGFR gene copy number (>4 copies using RT–PCR) and levels of MET expression (P = 0.03, Figure 2b).

Figure 2.

EGFR-activating mutations are associated with elevated MET and HIF-1α levels in NSCLC cell lines. (a) Gene expression analysis was performed on gene arrays of 53 NSCLC lines. MET expression was elevated in NSCLC cell lines harboring EGFR-activating mutations; *P = 0.002. (b) MET expression in 53 NSCLC cell lines with high EGFR gene copy number (>4 copies) vs low copy number (< 4 copies); *P = 0.03. (c) Western blot was used to evaluate pEGFR, EGFR, p-MET, MET, and HIF-1α expression in NSCLC cell lines expressing WT EGFR or mutationally activated EGFR. The presence of EGFR-activating mutations was associated with increased levels of p-MET, MET, and HIF-1α. (d–f) ELISA assay was used to analyze levels of p-EGFR (d), p-MET (e), and HIF-1α (f) in NSCLC cell lines expressing WT EGFR or mutationally activated EGFR. # indicates samples that were out of range.

We evaluated MET protein levels in NSCLC with or without EGFR-activating mutations and observed constitutive EGFR phosphorylation in cell lines with mutated EGFR, which was associated with increased phosphorylated MET (p-MET) and MET expression (Figure 2c). Cell lines with EGFR-activating mutations were positive for HIF-1α expression in normoxia. HCC827 cells, which exhibited the most robust expression of p-EGFR, produced the highest levels of HIF-1α, p-MET, and MET. Western data are supported by ELISA analysis showing higher levels of p-EGFR, p-MET, and HIF-1α in cell lines with EGFR-activating mutations compared with cells with WT EGFR (Figures 2d–f).

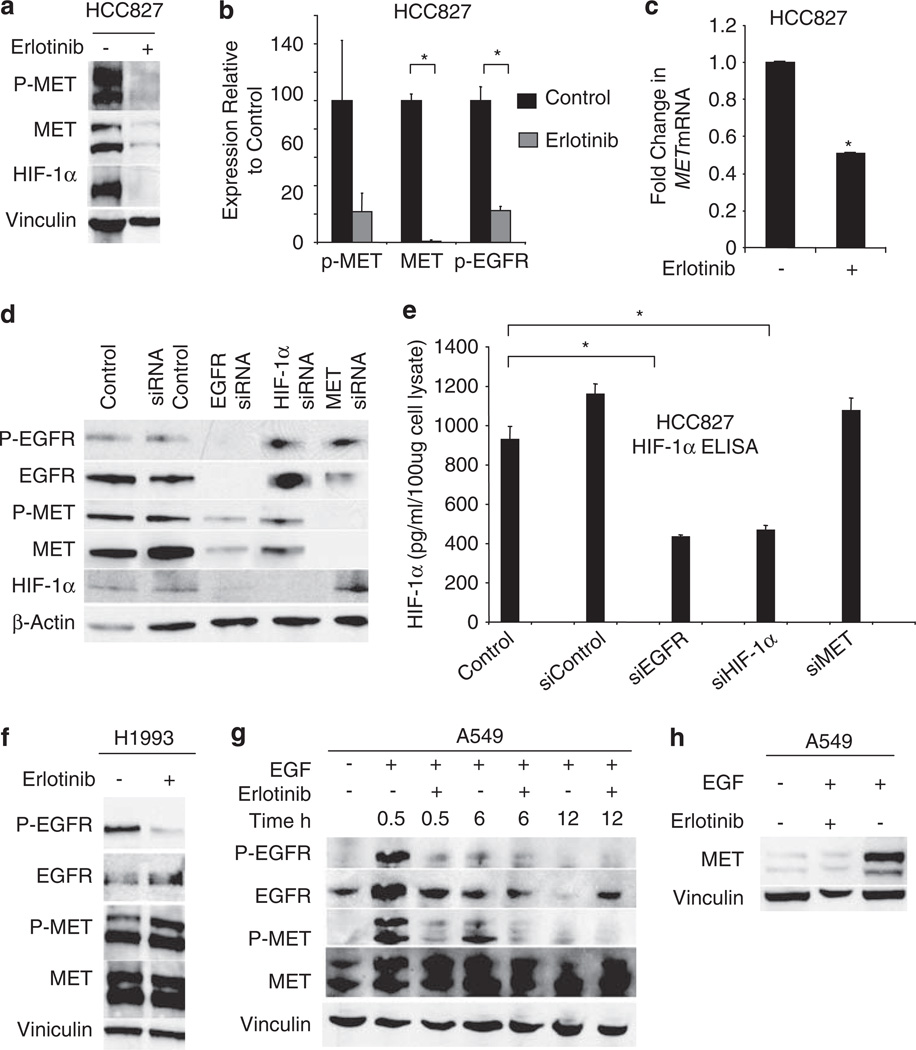

Activated EGFR modulates p-MET, MET, and HIF-1α

We treated HCC827 cells with 1 µm of erlotinib for 12 h and evaluated p-MET, MET, and HIF-1α levels. Erlotinib reduced p-MET and MET protein (Figure 3a). EGFR inhibition resulted in diminished HIF-1α levels. p-MET, MET, and p-EGFR were further analyzed by ELISA assay (Figure 3b). Consistant with data obtained by western blot, erlotinib decreased p-EGFR (P = 0.009), p-MET (P = 0.1), and MET (P = 0.001) levels. As HIF-1α is known to regulate MET transcription, we determined whether mutated EGFR would regulate MET mRNA levels. We treated HCC827 cells with or without erlotinib (1 µm) for 12 h and collected RNA for RT–PCR to evaluate changes in MET mRNA relative to GAPDH RNA. Inhibition of EGFR activity resulted in approximately a 50% decrease in MET RNA compared with control levels (Figure 3c).

Figure 3.

EGFR activation modulates levels of MET and p-MET in NSCLC cell lines. (a) HCC827 cells were treated with 1 µm erlotinib for 12 h. Protein lysates were collected after 8 h, and p-MET, MET, and HIF-1α levels were evaluated by western blot. (b) HCC827 cells were treated with 1 µm erlotinib for 12 h, and levels of p-MET, MET, and p-EGFR were evaluated by ELISA assay. *P < 0.01. (c) HCC827 cells were treated with 1 µm erlotinib for 12 h, and MET mRNA levels were evaluated by RT–PCR. Inhibition of EGFR activation decreased MET RNA. Bars, s.d.; *P < 0.001. (d) HCC827 cells were transfected with siRNA oligonucleotides directed against EGFR, HIF-1α, MET, and non-targeting control siRNA. After 72 h, protein lysates were collected and western blot was performed. (e) HIF-1α levels are decreased in HCC827 cells transfected with siRNA-targeting EGFR and HIF-1α as determined by ELISA. *P < 0.05. (f) H1993 cells, which have an amplified MET allele, were treated with 1 µm erlotinib for 12 h, and p-EGFR, EGFR, p-MET and MET expression were evaluated by immunoblot. (g) A549 cells were serum starved for 12 h and treated with EGF (60 ng/ml) with or without 1 µm erlotinib. Protein lysates were collected at the indicated times, and EGFR and MET activation were evaluated by immunoblot. (h) A549 cells were serum starved for 12 h and then stimulated with 60 ng/ml EGF with or without 1 µm erlotinib for 24 h.

To further show that EGFR signaling modulates HIF-1α and MET protein expression, we transfected HCC827 cells with control siRNA and EGFR-, HIF-1α-, and MET-targeting siRNA. Knockdown of EGFR decreased p-MET, MET, and HIF-1α levels. HIF-1α-targeting siRNA did not alter EGFR expression but reduced MET expression and activation, whereas MET siRNA reduced MET but not EGFR or HIF-1α levels (Figure 3d), indicating that HIF-1α and MET are downstream of EGFR. Similar results were obtained by HIF-1α ELISA assay. siRNA directed against EGFR but not MET decreased HIF-1α levels (P = 0.009; Figure 3e).

MET amplification has been described in a subset of NSCLC patients (Zhao et al., 2005; Engelman et al., 2007). To determine whether MET amplification would result in MET expression that was independent of EGFR, we treated H1993 NSCLC cells, which harbor an amplified MET allele (Engelman et al., 2007; Lutterbach et al., 2007), with erlotinib, and evaluated p-EGFR, EGFR, p-MET and MET levels. In contrast to the EGFR-dependent cell lines tested, pharmacological inhibition of EGFR did not diminish MET expression in this cell line (Figure 3f).

Previous studies suggested that activated EGFR can directly induce phosphorylation of MET (Bergstrom et al., 2000; Jo et al., 2000). To evaluate the effect of EGFR activation on MET in NSCLC, we stimulated A549 cells with EGF with or without erlotinib. Phosphorylated EGFR was detected 30 min after ligand stimulation, and EGFR activation was inhibited with erlotinib (Figure 3g). EGFR levels decreased 12 h after the addition of EGF, which may have been a result of receptor internalization. EGF stimulation triggered rises in p-MET levels at 30 min, suggesting that EGFR directly activated MET. p-MET levels remained detectable 6 h after EGF stimulation. Prolonged exposure (24 h) to EGF resulted in increased levels of MET protein (Figure 3h).

EGFR-mediated invasion of NSCLC cells is MET dependent

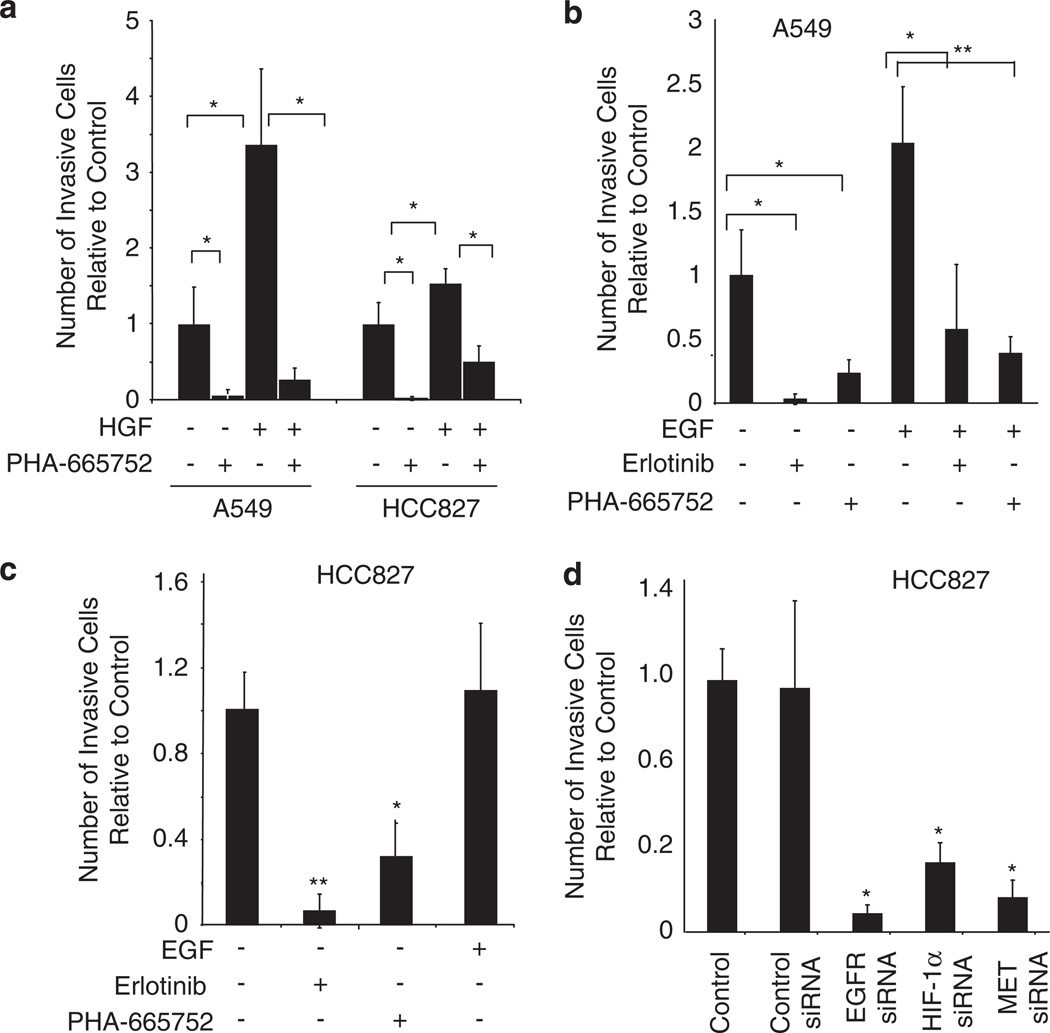

To show that MET activation increases invasiveness in NSCLC and that this can be abrogated with the MET TKI, PHA-665752, we treated A549 and HCC827 tumor cells with the MET ligand HGF alone or with PHA-66752. Cell invasion was measured using Matrigel-coated Boyden chambers. In both cell lines, HGF stimulation resulted in a significant increase in invasiveness, and this was inhibited with the addition of PHA-665752 (P < 0.05; Figure 4a). As EGFR activation has been shown to modulate tumor cell invasion in multiple cell types including NSCLC (Hamada et al., 1995; Damstrup et al., 1998), we investigated whether EGFR activation’s effect on tumor cell invasion is MET mediated. We stimulated A549 cells with EGF alone or with erlotinib or the MET TKI, PHA-665752. EGF induced a twofold increase in cell invasion compared with control (P < 0.05; Figure 4b). The addition of erlotinib or PHA-665752 reduced the number of invading cells to control levels, indicating that EGFR-driven cell invasion is MET dependent. In a similar experiment using HCC827 cells, in which EGFR is constitutively activated, EGF stimulation did not increase tumor cell invasiveness compared with control levels; however, pharmacological inhibition of EGFR or MET activation significantly reduced the number of invading cells (Figure 4c; P < 0.05).

Figure 4.

MET is required for EGFR-driven invasiveness of NSCLC cell lines. (a) A549 and HCC827 cells were seeded onto Matrigel-coated invasion chambers. Cells were treated with HGF (40 ng/ml) with or without PHA-663225 (1 µm) and incubated for 48 h. Migrating cells were quantified by bright-field microscopy. Bars, % s.d.; *P < 0.05. (b) A549 cells were seeded onto Matrigel-coated invasion chambers. Cells were treated with EGF (60 ng/ml), erlotinib (1 µm), or PHA-663225 (1 µm) and incubated for 24 h. EGF significantly enhanced cell invasion, and EGFR and MET inhibitors abrogated EGF-induced invasion. Bars, % s.d.; *P < 0.05; **P < 0.001. (c) HCC827 cells were treated with EGF, erlotinib, or PHA-663225 and tumor cell invasion was evaluated by Boyden chamber assay. Bars, % s.d.; *P < 0.05; **P < 0.001. (d) HCC8827 cells were transfected with control siRNA or siRNA-targeting EGFR, HIF-1α, or MET, and tumor cell invasion was evaluated by Boyden chamber assay. Bars, % s.d.; *P < 0.001.

To further elucidate the mechanism by which EGFR-activating mutations drive tumor cell invasion, we transfected HCC827 cells with EGFR-, HIF-1α-, or MET-targeting siRNA and evaluated cell invasion. Knockdown of EGFR, HIF-1α, or MET resulted in decreased invasive capacity (Figure 4d; P < 0.001), whereas control siRNA did not affect invasive capacity. To confirm that decreases in the number of invasive cells after erlotinib or siRNA treatment was indeed do to changes in the invasive capacity of tumor cells and not because of changes in cell viability or proliferation, we separately performed a similar study in which the number of invasive cells was normalized to the number of cells that did not invade through the chamber (Supplemental Figure 1). These data were in agreement with the findings shown above.

To determine whether MET inhibition impacted cellular growth, we conducted MTS (3-(4,5-dimethylthiazol-2-yl)-5-(3-carboxymethoxyphenyl)-2-(4-sulfophenyl)-2H-tetrazolium, inner salt) assays in the presence of increasing concentrations of erlotinib or PHA-665752. HCC827 cells were sensitive to the EGFR inhibitor erlotinib (IC50 < 10 nm), whereas H1993 and A549 cells were less sensitive (Supplemental Figure 2). None of the three cell lines were sensitive to PHA-665752 at concentrations as high as 10 µm. This suggested that invasiveness but not cell survival was MET dependent in these cell lines.

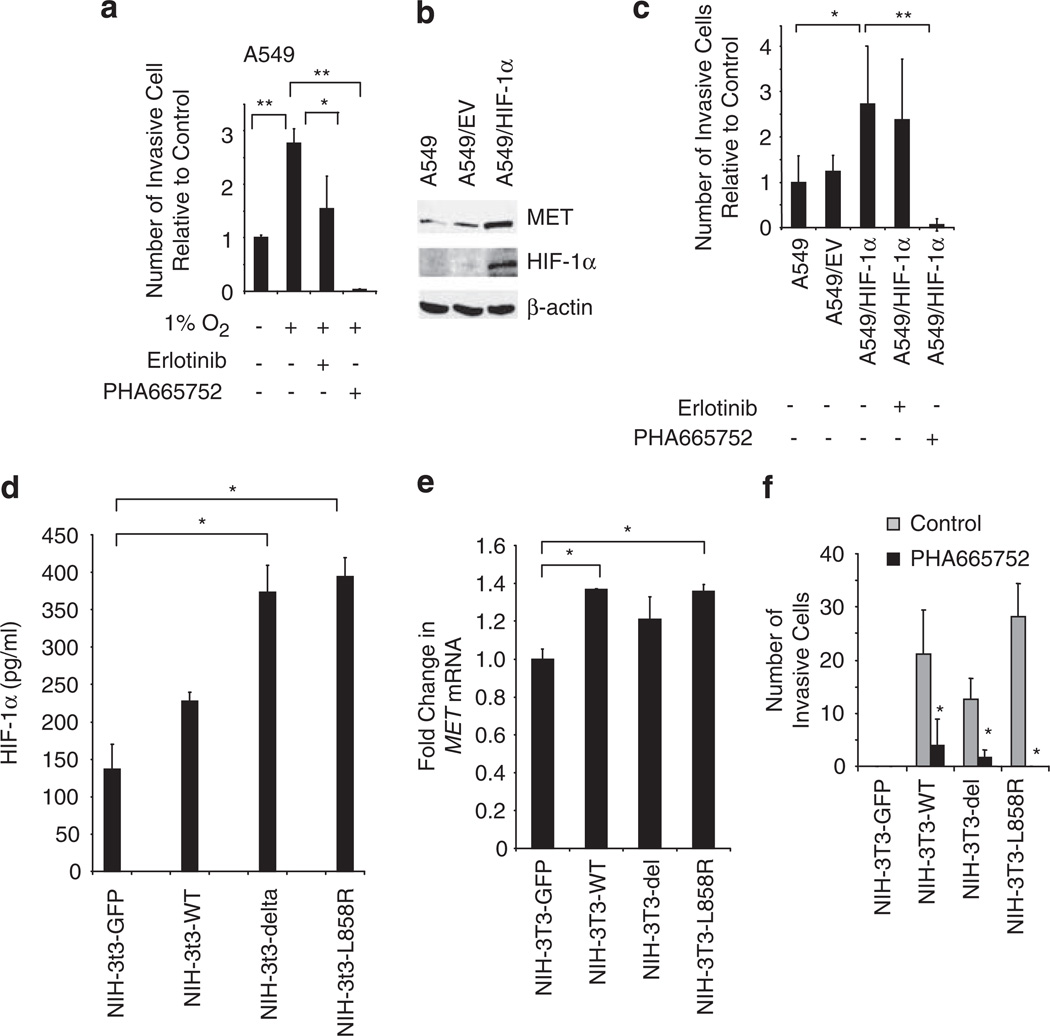

Hypoxia-induced invasiveness of NSCLC cells is MET dependent

Previous studies show that hypoxia increases the invasive capacity of tumor cells (Cuvier et al., 1997). Therefore, we investigated whether MET activation mediates hypoxia-induced invasiveness of tumor cells. A549 cells were plated in Matrigel-coated Boyden chambers and incubated in normoxia (21% oxygen) or hypoxia (0.1% oxygen) with or without erlotinib or PHA-665752. Hypoxia enhanced tumor cell invasion more than 2.5-fold (P < 0.001). Erlotinib caused a moderate decrease in tumor cell invasiveness, whereas MET inhibition reduced hypoxia-induced tumor cell invasion to levels below baseline (Figure 5a; P < 0.001).

Figure 5.

Hypoxia-induced tumor cell invasion is MET dependent. (a) A549 cells were seeded onto growth factor-reduced Matrigel-coated invasion chambers and incubated in normoxia or hypoxic (1% O2) conditions with or without erlotinib (1 µm) or PHA-663225 (1 µm) for 24 h, and the number of invading cells was quantified. Hypoxia-induced invasion was MET dependent but EGFR independent. Bars, % s.d.; *P < 0.05; **P < 0.001. (b) A549 cells were transfected to overexpress a degradation-resistant HIF-1α variant (HA- HIF-1α P402A;P564A), as shown by immunoblot. Increased HIF-1α was associated with enhanced MET expression. (c) A549 cells and A549 cells transfected with empty vector (EV) or plasmid containing the HIF1α mutant were evaluated for changes in invasive capacity in media with or without erlotinib (1 µm) or PHA-663225 (1 µm). After 24 h the number of invading cells was quantified. Bars,%s.d.; *P < 0.05; **P = 0.006. (d) NIH-3T3 cells expressing GFP, WT EGFR, or EGFR bearing the L858R mutation or the deletion mutant ΔL747-S752del were evaluated for HIF-1α levels by ELISA. *P < 0.05. (e) MET mRNA expression was evaluated by RT–PCR in NIH-3T3 cells expressing WT EGFR and EGFR-activating mutations. *P < 0.05. (f) NIH-3T3 cells expressing GFP, WT EGFR, or EGFR bearing the L858R mutation or the deletion mutant ΔL747-S752del were allowed to migrate through Matrigel-coated invasion chambers for 24 h with or without PHA-663225 (1 µm). Bars, s.d.; *P < 0.05.

To examine the role of HIF-1α in this pathway, we stably transfected A549 cells with a variant form of HIF-1α (HA- HIF-1α P402A;P564A) that is constitutively stabilized in normoxia because of proline to alanine substitutions at the VHL binding site critical for HIF-1α polyubiquitination and degradation (Masson et al., 2001; Hu et al., 2003; Kim et al., 2006). Expression of the HIF-1α variant augmented MET production (Figure 5b) and was associated with enhanced tumor cell invasion (P < 0.05; Figure 5c). PHA-665752, but not erlotinib, reduced the number of invading cells to below baseline values (P < 0.05). These findings were consistent with MET being a downstream mediator of HIF-1α-mediated invasiveness in thse cells.

We examined the impact of WT and mutated EGFR, and the role of MET, on invasiveness in NIH-3T3 cells. NIH-3T3 cells were stably transfected with control GFP plasmid, WT EGFR or EGFR bearing the L858R mutation or the deletion mutant ΔL747-5752del. A greater than twofold increase in HIF-1α levels was observed in cells bearing the ΔL747-5752del deletion (P = 0.02) or the L858R mutation (P = 0.01) compared with GFP transfected controls (Figure 5d). RT–PCR analysis revealed that NIH-3T3 cells expressing L858R expressed increased MET mRNA levels compared with GFP transfected controls (P = 0.02; Figure 5e). NIH-3T3 cells stably transfected with control GFP plasmid, WT EGFR, or EGFR bearing the L858R mutation or the deletion mutant ΔL747-5752del were allowed to invade Matrigel-coated Boyden chambers with or without PHA-66752. Cells expressing WT or activated EGFR had enhanced invasive capacity compared with cells transfected with GFP vector, and inhibition of MET significantly reduced the number of invasive cells to near baseline values (Figure 5f).

Discussion

This study offers new insights into the mechanisms by which EGFR mediates its tumorigenic effects and provides new evidence that the HIF-1α/MET axis is critical to regulating invasiveness induced not only by hypoxia but by EGFR as well, thus illustrating the convergence of two pathways known to drive invasive tumor growth. In NSCLC cells, we showed that EGFR activation, by either EGFR kinase mutations or ligand binding, increased MET levels through a hypoxia-independent mechanism involving expression of HIF-1α. MET was uncoupled from EGFR regulation, however, in a cell line with MET amplification, a finding consistent with the recently described role of MET amplification in EGFR TKI resistance (Engelman et al., 2007). Overexpression of a constitutively active form of HIF-1α also abrogated the regulation of MET levels by EGFR. Therefore, though this study shows that EGFR signaling can regulate MET levels and that MET can be downstream mediator of EGFR-induced invasiveness, it also suggests that there are ways by which this pathway may be bypassed.

We initially investigated MET levels in tumor specimens from 202 NSCLC patients by immunohistochemistry and observed increased levels of MET in tumors with EGFR-activating mutations compared with tumors with WT EGFR. Consistent with these findings, we observed elevated levels of MET in a previously described transgenic murine model of NSCLC with lung-specific expression of an EGFR-activating mutation. MET levels decreased significantly after treatment with the EGFR inhibitor erlotinib. We also observed that NSCLC cell lines expressing mutated EGFR exhibited elevated MET gene expression and protein levels compared with cells with WT EGFR, and these levels could be reduced by pharmacologically inhibiting EGFR or with siRNA directed against EGFR. The addition of an EGFR inhibitor decreased MET mRNA, indicating that in NSCLC cells, EGFR-activating mutations augment MET expression at the transcriptional level. Collectively, these results provide evidence that activated EGFR has a critical role in regulating MET expression in NSCLC tumor cells.

MET amplification has been described in the setting of gastric cancers (Smolen et al., 2006) and NSCLC (Engelman et al., 2007). Engelman et al. (2007) reported that among lung cancers with EGFR-activating mutations, MET amplification occurred in 22% of tumors that developed resistance to gefitinib or erlotinib. Overall, MET amplification occurs in only 4%of all NSCLC cases (Zhao et al., 2005), whereas high levels of MET and p-MET are detectable in 36 and 21% of NSCLC cases, respectively (Nakamura et al., 2007). MET expression also has been shown to be regulated by hypoxia (Pennacchietti et al., 2003). Here, we found evidence that EGFR is a key regulator of MET levels in cells without MET amplification, and that this occurs through hypoxia-independent regulation of HIF-1α. By contrast, in H1993 cells bearing MET gene amplification, EGFR blockade did not result in a reduction in MET levels, suggesting that MET amplification resulted in an uncoupling of MET protein levels from EGFR regulation.

Ligand-induced phosphorylation of EGFR has been shown to induce rises in HIF-1α in a cell type-specific manner. We observed that HIF-1α levels were elevated in NSCLC cell lines bearing EGFR mutations even in the absence of added ligand, and that treatment with an EGFR inhibitor diminished HIF-1α expression. Although this study did not specifically address the regulation of angiogenic factors such as VEGF, these findings are consistent with recent studies that EGFR regulates angiogenic factors, at least in part, through HIF-1α-dependent mechanisms (Swinson et al., 2004; Luwor et al., 2005; Pore et al., 2006; Swinson and O’Byrne, 2006). Studies designed to elucidate the mechanism by which EGFR-activating mutations regulate HIF-1α levels are ongoing.

In addition to enhancing MET levels, EGFR activation resulted in increases in MET receptor phosphorylation within 30 min of EGF stimulation, an effect blocked by erlotinib. Similar observations have been made with other cell types (Bergstrom et al., 2000; Jo et al., 2000); these and other published data support the idea that EGFR may directly phosphorylate MET (Bergstrom et al., 2000; Jo et al., 2000). Hypoxia is a known regulator of HGF, presumably through HIF-1α (Ide et al., 2006). It is feasible that EGFR-activating mutations promote HGF production through HIF-1α. Collectively, these data suggest that EGFR/HIF-1α activation may not only regulate MET levels, but may also impact MET signal transduction through other mechanisms.

We investigated the consequences of EGFR-regulated MET. We observed that the invasiveness (Figure 4) but not survival (Supplemental Figure 2) of NSCLC cells bearing EGFR-activating mutations was MET dependent, as pharmacological inhibition or siRNA directed against MET abrogated cell invasion. Invasiveness and MET levels were reduced by siRNA knockdown of HIF-1α, whereas EGFR levels were unaffected; indicating that MET is downstream of HIF-1α and EGFR. We observed that EGF- and hypoxia-induced invasiveness were both MET dependent, and that heterologous expression of a constitutively active form of HIF-1α induced invasiveness that was independent of EGF stimulation but remained MET dependent (Figure 5). Furthermore, heterologous expression of wild-type or mutated EGFR in NIH 3T3 fibroblasts increased invasiveness in an MET-dependent manner, providing further evidence that EGFR-mediated invasiveness is mediated at least in part by MET. These results support a model in which either hypoxia or EGFR activation can drive invasiveness by converging on a common HIF/MET pathway, which appears to be separable from EGFR-induced survival and proliferation. MET amplification appears to provide one route for circumventing this pathway. Others will likely emerge, and these findings do not exclude the likelihood that other pathways contribute to the invasive phenotype.

Our findings that EGFR can regulate MET levels through hypoxia-independent regulation of HIF-1α, and that MET is a downstream mediator of both EGFR- and hypoxia-induced invasivenss, have important clinical and biological implications. Even for tumors thought to be primarily driven by the EGFR pathway (that is with activating EGFR mutations), targeting of the MET pathway in combination with EGFR blockade may further reduce tumor invasiveness beyond the effect of EGFR inhibition alone, in addition to the previously noted potential benefit of preventing the emergence of resistance through MET amplification (Engelman et al., 2007). It also raises the question of whether other tyrosine kinases may regulate MET in a similar manner in NSCLC and other diseases. Finally, the observation that the EGFR and hypoxia converge on the HIF-1α/MET axis suggests that there may be additional overlap in the mechanisms by which EGFR and hypoxia promote malignant behavior and therapeutic resistance.

Materials and methods

Cell lines

Drs John Minna and Adi Gazdar (UT Southwestern Medical School, Dallas, TX, USA) provided H3255, H1975, H1993, and HCC827 cells. A549 and Calu-6 were obtained from the ATCC (Rockville, MD, USA). NIH-3T3 cells expressing WT EGFR or EGFR bearing the L858R mutation or the deletion mutant ΔL747-S752del (Shimamura et al., 2005) were obtained from Dr Jeffrey Engelman (Dana-Farber Cancer Institute) and were maintained in 10% FBS DMEM containing 1 mg/ml puromycin.

Mice

Animals were treated in accordance with the guidelines of the US Department of Agriculture and the NIH. KrasLA1 mice (Johnson et al., 2001) were obtained from Dr Tyler Jacks (Massachusetts Institute of Technology, Cambridge, MA, USA). CCSP-rtTA transgenic mice (obtained from J Whitsett at The University of Cincinnati, Cincinnati, OH, USA) were bred with Tet-op-hEGFR L858R-Luc to yield mice with lung tumors driven by EGFR activation (Ji et al., 2006). At 6 months of age, lungs were collected. Animals bearing EGFR-driven lung tumors were treated with vehicle (1% Tween-80; Sigma-Aldrich, St Louis, MO, USA), or erlotinib (50 mg/kg/day) by gavage for 48 h.

Gene expression analysis

Affymetrix GeneChip Human Genome U133A (HG-U133A) was used to perform gene expression analysis on 53 gene arrays of NSCLC cell lines prepared by John Minna and colleagues (UT Southwestern, Dallas, TX, USA; (Zhou et al., 2006). CEL-type data files were obtained from NCBI-GEO dataset GSE4824 (NCBI-GEO, 2007). CHIP (2007) software (http://biosun1.harvard.edu/complab/dchip/) was used to generate probe-level gene expression, median intensity, percentage of probe set outliers, and percentage of single probe outliers (Lin et al., 2004). Information files, including the HG-U133A gene information files and Chip Description Files, were downloaded from the Affymetrix web site. CEL and other data files were extracted. Array images were inspected for contamination and bad hybridization. Normalization was performed using the invariant-set normalization method (Li and Hung Wong, 2001). Model-based expression and background subtraction using the 5th percentile of region (perfect match only) was completed by checking for single, array, and probe outliers. In the array analysis and clustering, array outliers were treated as missing values and no log transformation was performed. Comparison within dCHIP of the WT EGFR vs mutated EGFR groups using a more than 1.2-fold change in gene expression, a 90% confidence interval for fold change, and a 90% present call yielded one probeset for MET (203510_at). Data were further analyzed using GraphPad software (version 5, GraphPad Software Inc., La Jolla, CA, USA).

Detection of HIF-1α, MET, and EGFR

Protein lysates were extracted using RIPA buffer (50mm Tris–HCl, pH 7.4, 150 mm NaCl, 1 mm EDTA, 1% Triton X-100, 1% sodium deoxycholate, and 0.1% SDS, and protease inhibitors. Protein (60 µg) was used for western blotting. Antibodies against EGFR (Y1068, Cell Signaling Technology Inc., Danvers, MA, USA), EGFR (Santa Cruz Biotechnology Inc., Santa Cruz, CA, USA) MET (Santa Cruz), HIF-1α (Pharmingen, San Diego, CA, USA), β-actin (Sigma), and vinculin (Sigma) were used. HIF-1α, p-EGFR, MET, and p-MET ELISAs were obtained from R&D systems (Minneapolis, MN, USA).

RNA isolation and RT–PCR

HCC827 cells were treated with complete media with or without 1 µm erlotinib for 12 h. Total RNA was extracted using Trizol (Life Technologies, Carlsbad, CA, USA), and purified with the RNeasy kit (Qiagen, Hilden, Germany). We used SuperScriptTM III RNase H-Reverse Transcriptase (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA, USA) to convert RNA into cDNA. The oligonucleotide primers used were published previously (Shimazaki et al., 2003).

Plasmids and transfections

HIF-1α cDNA (OriGene Technologies Inc., Rockville, MD, USA) was subcloned into the pcDNA3.1 vector with a flag tagged in the N-terminal, and the HIF-1α mutant with proline to alanine substitutions positions 402 and 564 (HA- HIF-1α P402A;P564A), which are known VHL-binding sites, was constructed as described (Kim et al., 2006). This form is stabilized in normoxia because of the loss of VHL-mediated polyubiquitination and subsequent degradation (Masson et al., 2001; Hu et al., 2003). For siRNA transfections, HCC827 cells were transfected with siRNA targetting EGFR, MET, HIF-1α and control siRNA at a final concentration of 100 nm using Dharmafect 1 transfection reagent (Dharmacon, Lafayette, CO, USA). Protein was isoloated after 72 h. Transfected cells were plated for invasion assays after 48 h.

Invasion assay

We seeded 2.5 × 104 cells in the upper chamber of 24-well BD Biocoat growth factor reduced Matrigel invasion chambers (8.0 µm pore, Becton Dickinson, Bedford, MA, USA) with 0% FBS media and added media containing 10% FBS to the lower chamber. After 24 h, cells in the upper chamber were removed by scraping. Cells that migrated to the lower chamber were stained and counted using bright-field microscopy under a low-power (× 40) objective. PHA-663225 was obtained from Pfizer (New York, NY, USA).

Clinical specimens

Tissue specimens from 202 surgically resected lung carcinomas were obtained from the Lung Cancer Specialized Program of Research Excellence (SPORE) Tissue Bank at The University of Texas MD Anderson Cancer Center (Houston, TX, USA). Two hundred and two specimens had known EGFR status. Microarrays for each specimen were created with three cores from formalin-fixed, paraffin-embedded blocks. All specimens were of pathologic TNM stages I–IV according to the revised International System for Staging Lung Cancer (Beadsmoore and Screaton, 2003).

Immunohistochemistry staining

Using paraffin-embedded tissue sections, antigen retrieval was performed by steaming in citrate buffer (pH 6.0). Endogenous peroxidases were blocked using 3% H2O2. After protein blocking, slides were incubated with anti-HGFR (1:50; R&D Systems), washed, and incubated with a Universal LSAB + Kit/HRP, visualization kit (DakoCytomation, Carpinteria, CA, USA). For tumor sections from transgenic animals, antigen retrieval and blocking was performed as above. Slides were incubated in 1:100 anti-mouse MET antibodies (Santa Cruz) and then in secondary antibody (Jackson Research Laboratories, Bar Harbor, ME, USA). NSCLC specimens were used as positive controls for MET staining. As a negative control, we followed the above procedure omitting the primary antibodies. For quantification, each specimen was evaluated using an intensity score (0, 1, 2, or 3) and an extension percentage (Yang et al., 2008). The final staining score was the product of these two values. An average from the three cores was obtained for each specimen.

Statistics

Student’s t-tests were performed using two-tailed tests with unequal variance for Gaussian distributed data. For statistical analysis of clinical specimens, Wilcoxon rank-sum tests were used when comparing continuous variables between mutation groups. To correlate mutation and other discrete covariates, we used a chi-square test or Fisher’s exact test. Two-sided P-values ≤0.05 were considered significant.

Accession numbers

SNP and CGH raw data are available in the Gene Expression Omnibus (GEO) database: GEO accession GSE4824 (http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/geo/).

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

We thank Drs Mien-Chie Hung, Scott Lippman, and Kian Ang for their critical review, Dr Jeffrey Engelman for the EGFR-transfected NIH 3T3 cell lines, and Joseph Munch for editorial assistance. Supported in part by the NIH Lung Cancer SPORE grant P50 CA70907, NIH Grant P01 CA06294, Department of Defense Grant W81XWH-07-1-0306 01, awards from the Metastasis Foundation, the Physician-Scientist Program, and the American Society for Clinical Oncology Career Development Award (JVH). JVH is a Damon Runyon-Lilly Clinical Investigator supported in part by the Damon Runyon Cancer Research Foundation (CI 24-04).

Footnotes

Conflict of interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Supplementary Information accompanies the paper on the Oncogene website (http://www.nature.com/onc)

References

- Beadsmoore CJ, Screaton NJ. Classification, staging and prognosis of lung cancer. Eur J Radiol. 2003;45:8–17. doi: 10.1016/s0720-048x(02)00287-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bergstrom JD, Westermark B, Heldin NE. Epidermal growth factor receptor signaling activates met in human anaplastic thyroid carcinoma cells. Exp Cell Res. 2000;259:293–299. doi: 10.1006/excr.2000.4967. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bredin CG, Liu Z, Klominek J. Growth factor-enhanced expression and activity of matrix metalloproteases in human non-small cell lung cancer cell lines. Anticancer Res. 2003;23:4877–4884. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ciardiello F, Tortora G. EGFR antagonists in cancer treatment. N Engl J Med. 2008;358:1160–1174. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra0707704. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cooper CS, Tempest PR, Beckman MP, Heldin CH, Brookes P. Amplification and overexpression of the met gene in spontaneously transformed NIH3T3 mouse fibroblasts. EMBO J. 1986;5:2623–2628. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1986.tb04543.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cuvier C, Jang A, Hill RP. Exposure to hypoxia, glucose starvation and acidosis: effect on invasive capacity of murine tumor cells and correlation with cathepsin (L + B) secretion. Clin Exp Metastasis. 1997;15:19–25. doi: 10.1023/a:1018428105463. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Damstrup L, Rude Voldborg B, Spang-Thomsen M, Brunner N, Skovgaard Poulsen H. In vitro invasion of small-cell lung cancer cell lines correlates with expression of epidermal growth factor receptor. Br J Cancer. 1998;78:631–640. doi: 10.1038/bjc.1998.553. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Engelman JA, Zejnullahu K, Mitsudomi T, Song Y, Hyland C, Park JO, et al. MET amplification leads to gefitinib resistance in lung cancer by activating ERBB3 signaling. Science. 2007;316:1039–1043. doi: 10.1126/science.1141478. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Forsythe JA, Jiang BH, Iyer NV, Agani F, Leung SW, Koos RD, et al. Activation of vascular endothelial growth factor gene transcription by hypoxia-inducible factor 1. Mol Cell Biol. 1996;16:4604–4613. doi: 10.1128/mcb.16.9.4604. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fukuoka M, Yano S, Giaccone G, Tamura T, Nakagawa K, Douillard JY, et al. Multi-institutional randomized phase II trial of gefitinib for previously treated patients with advanced non-small-cell lung cancer (The IDEAL 1 Trial) [corrected] J Clin Oncol. 2003;21:2237–2246. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2003.10.038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guo A, Villen J, Kornhauser J, Lee KA, Stokes MP, Rikova K, et al. Signaling networks assembled by oncogenic EGFR and c-Met. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2008;105:692–697. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0707270105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hamada J, Nagayasu H, Takayama M, Kawano T, Hosokawa M, Takeichi N. Enhanced effect of epidermal growth factor on pulmonary metastasis and in vitro invasion of rat mammary carcinoma cells. Cancer Lett. 1995;89:161–167. doi: 10.1016/0304-3835(95)03686-q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hirami Y, Aoe M, Tsukuda K, Hara F, Otani Y, Koshimune R, et al. Relation of epidermal growth factor receptor, phosphorylated-Akt, and hypoxia-inducible factor-1alpha in non-small cell lung cancers. Cancer Lett. 2004;214:157–164. doi: 10.1016/j.canlet.2004.04.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hu CJ, Wang LY, Chodosh LA, Keith B, Simon MC. Differential roles of hypoxia-inducible factor 1alpha (HIF-1alpha) and HIF-2alpha in hypoxic gene regulation. Mol Cell Biol. 2003;23:9361–9374. doi: 10.1128/MCB.23.24.9361-9374.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang PH, Mukasa A, Bonavia R, Flynn RA, Brewer ZE, Cavenee WK, et al. Quantitative analysis of EGFRvIII cellular signaling networks reveals a combinatorial therapeutic strategy for glioblastoma. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2007;104:12867–12872. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0705158104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ichimura E, Maeshima A, Nakajima T, Nakamura T. Expression of c-met/HGF receptor in human non-small cell lung carcinomas in vitro and in vivo and its prognostic significance. Jpn J Cancer Res. 1996;87:1063–1069. doi: 10.1111/j.1349-7006.1996.tb03111.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ide T, Kitajima Y, Miyoshi A, Ohtsuka T, Mitsuno M, Ohtaka K, et al. Tumor-stromal cell interaction under hypoxia increases the invasiveness of pancreatic cancer cells through the hepatocyte growth factor/c-Met pathway. Int J Cancer. 2006;119:2750–2759. doi: 10.1002/ijc.22178. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Janne PA, Engelman JA, Johnson BE. Epidermal growth factor receptor mutations in non-small-cell lung cancer: implications for treatment and tumor biology. J Clin Oncol. 2005;23:3227–3234. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2005.09.985. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ji H, Li D, Chen L, Shimamura T, Kobayashi S, McNamara K, et al. The impact of human EGFR kinase domain mutations on lung tumorigenesis and in vivo sensitivity to EGFR-targeted therapies. Cancer Cell. 2006;9:485–495. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2006.04.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jo M, Stolz DB, Esplen JE, Dorko K, Michalopoulos GK, Strom SC. Cross-talk between epidermal growth factor receptor and c-Met signal pathways in transformed cells. J Biol Chem. 2000;275:8806–8811. doi: 10.1074/jbc.275.12.8806. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnson L, Mercer K, Greenbaum D, Bronson RT, Crowley D, Tuveson DA, et al. Somatic activation of the K-ras oncogene causes early onset lung cancer in mice. Nature. 2001;410:1111–1116. doi: 10.1038/35074129. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim WY, Safran M, Buckley MR, Ebert BL, Glickman J, Bosenberg M, et al. Failure to prolyl hydroxylate hypoxia-inducible factor alpha phenocopies VHL inactivation in vivo. EMBO J. 2006;25:4650–4662. doi: 10.1038/sj.emboj.7601300. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kris MG, Natale RB, Herbst RS, Lynch TJ, Jr, Prager D, Belani CP, et al. Efficacy of gefitinib, an inhibitor of the epidermal growth factor receptor tyrosine kinase, in symptomatic patients with non-small cell lung cancer: a randomized trial. JAMA. 2003;290:2149–2158. doi: 10.1001/jama.290.16.2149. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li C, Hung Wong W. Model-based analysis of oligonucleotide arrays: model validation, design issues and standard error application. Genome Biol. 2001;2 doi: 10.1186/gb-2001-2-8-research0032. RESEARCH0032. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lin M, Wei LJ, Sellers WR, Lieberfarb M, Wong WH, Li C. dChipSNP: significance curve and clustering of SNP-array-based loss-of-heterozygosity data. Bioinformatics. 2004;20:1233–1240. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/bth069. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu C, Tsao MS. In vitro and in vivo expressions of transforming growth factor-alpha and tyrosine kinase receptors in human non-small-cell lung carcinomas. Am J Pathol. 1993;142:1155–1162. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lutterbach B, Zeng Q, Davis LJ, Hatch H, Hang G, Kohl NE, et al. Lung cancer cell lines harboring MET gene amplification are dependent on Met for growth and survival. Cancer Res. 2007;67:2081–2088. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-06-3495. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luwor RB, Lu Y, Li X, Mendelsohn J, Fan Z. The antiepidermal growth factor receptor monoclonal antibody cetuximab/C225 reduces hypoxia-inducible factor-1 alpha, leading to transcriptional inhibition of vascular endothelial growth factor expression. Oncogene. 2005;24:4433–4441. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1208625. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lynch TJ, Bell DW, Sordella R, Gurubhagavatula S, Okimoto RA, Brannigan BW, et al. Activating mutations in the epidermal growth factor receptor underlying responsiveness of non-small-cell lung cancer to gefitinib. N Engl J Med. 2004;350:2129–2139. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa040938. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Masson N, Willam C, Maxwell PH, Pugh CW, Ratcliffe PJ. Independent function of two destruction domains in hypoxia-inducible factor-alpha chains activated by prolyl hydroxylation. EMBO J. 2001;20:5197–5206. doi: 10.1093/emboj/20.18.5197. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nakamura Y, Niki T, Goto A, Morikawa T, Miyazawa K, Nakajima J, et al. c-Met activation in lung adenocarcinoma tissues: An immunohistochemical analysis. Cancer Sci. 2007;98:1006–1013. doi: 10.1111/j.1349-7006.2007.00493.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- NCBI-GEO. 2007 http://www ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/geo/.

- Olivero M, Rizzo M, Madeddu R, Casadio C, Pennacchietti S, Nicotra MR, et al. Overexpression and activation of hepatocyte growth factor/scatter factor in human non-small-cell lung carcinomas. Br J Cancer. 1996;74:1862–1868. doi: 10.1038/bjc.1996.646. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paez JG, Janne PA, Lee JC, Tracy S, Greulich H, Gabriel S, et al. EGFR mutations in lung cancer: correlation with clinical response to gefitinib therapy. Science. 2004;304:1497–1500. doi: 10.1126/science.1099314. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pai R, Nakamura T, Moon WS, Tarnawski AS. Prostaglandins promote colon cancer cell invasion; signaling by cross-talk between two distinct growth factor receptors. FASEB J. 2003;17:1640–1647. doi: 10.1096/fj.02-1011com. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pao W, Miller V, Zakowski M, Doherty J, Politi K, Sarkaria I, et al. EGF receptor gene mutations are common in lung cancers from ‘never smokers’ and are associated with sensitivity of tumors to gefitinib and erlotinib. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2004;101:13306–13311. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0405220101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pao W, Miller VA. Epidermal growth factor receptor mutations, small-molecule kinase inhibitors, and non-small-cell lung cancer: current knowledge and future directions. J Clin Oncol. 2005;23:2556–2568. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2005.07.799. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Park M, Dean M, Kaul K, Braun MJ, Gonda MA, Vande Woude G. Sequence of MET protooncogene cDNA has features characteristic of the tyrosine kinase family of growth-factor receptors. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1987;84:6379–6383. doi: 10.1073/pnas.84.18.6379. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peng XH, Karna P, Cao Z, Jiang BH, Zhou M, Yang L. Cross-talk between epidermal growth factor receptor and hypoxia-inducible factor-1alpha signal pathways increases resistance to apoptosis by up-regulating survivin gene expression. J Biol Chem. 2006;281:25903–25914. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M603414200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pennacchietti S, Michieli P, Galluzzo M, Mazzone M, Giordano S, Comoglio PM. Hypoxia promotes invasive growth by transcriptional activation of the met protooncogene. Cancer Cell. 2003;3:347–361. doi: 10.1016/s1535-6108(03)00085-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peruzzi B, Bottaro DP. Targeting the c-Met signaling pathway in cancer. Clin Cancer Res. 2006;12:3657–3660. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-06-0818. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Phillips RJ, Mestas J, Gharaee-Kermani M, Burdick MD, Sica A, Belperio JA, et al. Epidermal growth factor and hypoxia-induced expression of CXC chemokine receptor 4 on non-small cell lung cancer cells is regulated by the phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase/PTEN/AKT/mammalian target of rapamycin signaling pathway and activation of hypoxia inducible factor-1alpha. J Biol Chem. 2005;280:22473–22481. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M500963200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pore N, Jiang Z, Gupta A, Cerniglia G, Kao GD, Maity A. EGFR tyrosine kinase inhibitors decrease VEGF expression by both hypoxia-inducible factor (HIF)-1-independent and HIF1-dependent mechanisms. Cancer Res. 2006;66:3197–3204. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-05-3090. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Qiao H, Hung W, Tremblay E, Wojcik J, Gui J, Ho J, et al. Constitutive activation of met kinase in non-small-cell lung carcinomas correlates with anchorage-independent cell survival. J Cell Biochem. 2002;86:665–677. doi: 10.1002/jcb.10239. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rosario M, Birchmeier W. How to make tubes: signaling by the Met receptor tyrosine kinase. Trends Cell Biol. 2003;13:328–335. doi: 10.1016/s0962-8924(03)00104-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scheving LA, Stevenson MC, Taylormoore JM, Traxler P, Russell WE. Integral role of the EGF receptor in HGF-mediated hepatocyte proliferation. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2002;290:197–203. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.2001.6157. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shepherd FA, Rodrigues Pereira J, Ciuleanu T, Tan EH, Hirsh V, Thongprasert S, et al. Erlotinib in previously treated non-small-cell lung cancer. N Engl J Med. 2005;353:123–132. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa050753. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shimamura T, Lowell AM, Engelman JA, Shapiro GI. Epidermal growth factor receptors harboring kinase domain mutations associate with the heat shock protein 90 chaperone and are destabilized following exposure to geldanamycins. Cancer Res. 2005;65:6401–6408. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-05-0933. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shimazaki K, Yoshida K, Hirose Y, Ishimori H, Katayama M, Kawase T. Cytokines regulate c-Met expression in cultured astrocytes. Brain Res. 2003;962:105–110. doi: 10.1016/s0006-8993(02)03975-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Siegfried JM, Weissfeld LA, Luketich JD, Weyant RJ, Gubish CT, Landreneau RJ. The clinical significance of hepatocyte growth factor for non-small cell lung cancer. Ann Thorac Surg. 1998;66:1915–1918. doi: 10.1016/s0003-4975(98)01165-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smolen GA, Sordella R, Muir B, Mohapatra G, Barmettler A, Archibald H, et al. Amplification of MET may identify a subset of cancers with extreme sensitivity to the selective tyrosine kinase inhibitor PHA-665752. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2006;103:2316–2321. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0508776103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stabile LP, Lyker JS, Huang L, Siegfried JM. Inhibition of human non-small cell lung tumors by a c-Met antisense/U6 expression plasmid strategy. Gene Ther. 2004;11:325–335. doi: 10.1038/sj.gt.3302169. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Swinson DE, Jones JL, Cox G, Richardson D, Harris AL, O’Byrne KJ. Hypoxia-inducible factor-1 alpha in non small cell lung cancer: relation to growth factor, protease and apoptosis pathways. Int J Cancer. 2004;111:43–50. doi: 10.1002/ijc.20052. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Swinson DE, O’Byrne KJ. Interactions between hypoxia and epidermal growth factor receptor in non-small-cell lung cancer. Clin Lung Cancer. 2006;7:250–256. doi: 10.3816/CLC.2006.n.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thatcher N, Chang A, Parikh P, Rodrigues Pereira J, Ciuleanu T, von Pawel J, et al. Gefitinib plus best supportive care in previously treated patients with refractory advanced non-small-cell lung cancer: results from a randomised, placebo-controlled, multi-centre study (Iressa Survival Evaluation in Lung Cancer) Lancet. 2005;366:1527–1537. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(05)67625-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weinberger PM, Yu Z, Kowalski D, Joe J, Manger P, Psyrri A, et al. Differential expression of epidermal growth factor receptor, c-Met, and HER2/neu in chordoma compared with 17 other malignancies. Arch Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2005;131:707–711. doi: 10.1001/archotol.131.8.707. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang Y, Wislez M, Fujimoto N, Prudkin L, Izzo JG, Uno F, et al. A selective small molecule inhibitor of c-Met, PHA-665752, reverses lung premalignancy induced by mutant K-ras. Mol Cancer Ther. 2008;7:952–960. doi: 10.1158/1535-7163.MCT-07-2045. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yi S, Chen JR, Viallet J, Schwall RH, Nakamura T, Tsao MS. Paracrine effects of hepatocyte growth factor/scatter factor on non-small-cell lung carcinoma cell lines. Br J Cancer. 1998;77:2162–2170. doi: 10.1038/bjc.1998.361. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhao X, Weir BA, LaFramboise T, Lin M, Beroukhim R, Garraway L, et al. Homozygous deletions and chromosome amplifications in human lung carcinomas revealed by single nucleotide polymorphism array analysis. Cancer Res. 2005;65:5561–5570. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-04-4603. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhong H, Chiles K, Feldser D, Laughner E, Hanrahan C, Georgescu MM, et al. Modulation of hypoxia-inducible factor 1alpha expression by the epidermal growth factor/phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase/PTEN/AKT/FRAP pathway in human prostate cancer cells: implications for tumor angiogenesis and therapeutics. Cancer Res. 2000;60:1541–1545. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhou BB, Peyton M, He B, Liu C, Girard L, Caudler E, et al. Targeting ADAM-mediated ligand cleavage to inhibit HER3 and EGFR pathways in non-small cell lung cancer. Cancer Cell. 2006;10:39–50. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2006.05.024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.