Abstract

Exposure of insulin-producing cells to elevated levels of the free fatty acid (FFA) palmitate results in the loss of β-cell function and induction of apoptosis. The induction of endoplasmic reticulum (ER) stress is one mechanism proposed to be responsible for the loss of β-cell viability in response to palmitate treatment; however, the pathways responsible for the induction of ER stress by palmitate have yet to be determined. Protein palmitoylation is a major posttranslational modification that regulates protein localization, stability, and activity. Defects in, or dysregulation of, protein palmitoylation could be one mechanism by which palmitate may induce ER stress in β-cells. The purpose of this study was to evaluate the hypothesis that palmitate-induced ER stress and β-cell toxicity are mediated by excess or aberrant protein palmitoylation. In a concentration-dependent fashion, palmitate treatment of RINm5F cells results in a loss of viability. Similar to palmitate, stearate also induces a concentration-related loss of RINm5F cell viability, while the monounsaturated fatty acids, such as palmoleate and oleate, are not toxic to RINm5F cells. 2-Bromopalmitate (2BrP), a classical inhibitor of protein palmitoylation that has been extensively used as an inhibitor of G protein-coupled receptor signaling, attenuates palmitate-induced RINm5F cell death in a concentration-dependent manner. The protective effects of 2BrP are associated with the inhibition of [3H]palmitate incorporation into RINm5F cell protein. Furthermore, 2BrP does not inhibit, but appears to enhance, the oxidation of palmitate. The induction of ER stress in response to palmitate treatment and the activation of caspase activity are attenuated by 2BrP. Consistent with protective effects on insulinoma cells, 2BrP also attenuates the inhibitory actions of prolonged palmitate treatment on insulin secretion by isolated rat islets. These studies support a role for aberrant protein palmitoylation as a mechanism by which palmitate enhances ER stress activation and causes the loss of insulinoma cell viability.

Keywords: apoptosis, palmitate, endoplasmic reticulum stress

over the last 20–30 years, modern lifestyles, with abundant nutrient supply and reduced physical activity, have resulted in dramatic increases in the incidence of obesity and type 2 diabetes (41, 53, 72). Obesity is associated with hyperlipidemia, and the accompanying elevated free fatty acids (FFAs) are believed to contribute to insulin resistance, impaired insulin secretion, and the progressive decline in pancreatic β-cell mass in type 2 diabetes (6, 19, 24, 58, 70, 78). Elevated plasma FFAs may provide a mechanistic link between increased fat mass, insulin resistance, and type 2 diabetes.

Chronic exposure to long-chain saturated fatty acids at concentrations found in type 2 diabetic patients is toxic to pancreatic β-cells (16, 57, 64, 70), but the mechanisms by which these fats alter β-cell function and viability are not well understood. While multiple mechanisms, including ceramide formation (45, 46, 73), oxidative stress (47, 56, 62), and inflammation (8, 32), have been proposed, there is little consensus on a mechanism to explain the loss of β-cell viability following exposure to elevated FFAs. A growing number of studies support a role for persistent endoplasmic reticulum (ER) stress in saturated fatty acid-induced β-cell death (2, 16, 35, 38, 40, 50, 51, 63, 80).

The ER is a vast membranous network responsible for the synthesis, maturation, trafficking, and quality control for a wide range of proteins. ER stress results when the load of client proteins entering the ER exceeds their capacity to be correctly folded. Cells can readjust the balance between protein production and folding by activating the unfolded protein response, but if this adaptive response fails to resolve the stress, apoptosis can ensue (29, 49). Although the enhanced secretory demand that accompanies insulin resistance probably contributes to ER stress in β-cells, ER stress can also be triggered by direct actions of saturated fatty acids on the ER (65); however, the molecular mechanisms underlying these direct effects remain unclear.

There are a number of ways to create an imbalance between protein folding and protein synthesis resulting in ER stress. Mutations in proteins that alter signal recognition or folding can induce ER stress (7, 59). Defects causing excessive or attenuated posttranslational modification of proteins are also capable of inducing ER stress (37, 49). Protein palmitoylation occurs by addition of the 16-carbon saturated palmitate group via a thioester to the sulfhydryl group on cysteine residues. This is a reversible lipid modification that affects a range of functions, including protein trafficking, protein sorting, protein stability, and protein aggregation (25, 42). In this study, we used the palmitate analog 2-bromopalmitate (2BrP) to examine whether changes in posttranslational modification of β-cell proteins may mediate palmitate-induced ER stress induction and β-cell death. We show that 2BrP, a nonmetabolizable palmitate analog that inhibits protein palmitoylation, attenuates palmitate-induced ER stress induction and cell death. These findings support the hypothesis that FFA-induced β-cell damage may be mediated by unregulated palmitoylation of proteins, resulting in the induction of ER stress and β-cell death.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Materials.

RPMI 1640 medium, l-glutamine, streptomycin, and penicillin were purchased from Invitrogen; fetal calf serum, myristate, palmitate, stearate, palmitolate, oleate, 2BrP, cerulenin, tunicamycin, and neutral red from Sigma-Aldrich (St. Louis, MO); [9,10-3H(N)]- and [1-14C]palmitate from PerkinElmer (Waltham, MA); fatty acid-free BSA from Roche; C/EBP homologous protein (CHOP) and phosphorylated eukaryotic initiation factor-2α (eIF2α) antibodies from Cell Signaling (Beverly, MA); GAPDH antibody from Ambion (Austin, TX); horseradish peroxidase-conjugated donkey anti-rabbit antibody from Jackson Immunoresearch Laboratories (West Grove, PA); and all RT-PCR primers from Integrated DNA Technologies (Coralville, IA).

Fatty acid-albumin complex preparation.

Sodium salts (20 mM) of fatty acids were prepared by heating equimolar NaOH and fatty acid at 60°C for 1 h. Sodium salt was then combined with 15% fatty acid-free BSA solution in a ratio of 2:3 and heated at 60°C for 1 h to produce 8 mM fatty acid-9% BSA complex, and pH was adjusted to 7.4.

Cell culture.

RINm5F cells were cultured in RPMI 1640 medium supplemented with 10% FBS, 2 mM l-glutamine, 1 mM sodium pyruvate, 50 U/ml penicillin, and 50 μg/ml streptomycin. Cells were maintained at 37°C under an atmosphere of 95% air-5% CO2. RINm5F cells were removed from growth flasks by treatment with 0.05% trypsin and 0.02% EDTA for 5 min at 37°C, washed with RPMI 1640 medium, and plated at indicated cell densities.

Rat islet isolation and glucose-induced insulin secretion.

Islets were isolated from male Sprague-Dawley rats (200–250 g body wt) by collagenase digestion, as previously described (52), and cultured overnight in complete CMRL-1066 medium (CMRL-1066 medium containing 2 mM l-glutamine, 10% heat-inactivated FBS, 100 U/ml penicillin, and 100 μg/ml streptomycin) under an atmosphere of 95% air-5% CO2. Groups of 120 islets were pretreated with 100 μM 2BrP for 1 h prior to the addition of 500 μM palmitate. After a 48-h culture, the islets were washed three times (3 ml per wash) in Krebs-Ringer bicarbonate buffer (in mM: 25 HEPES, 115 NaCl, 24 NaHCO3, 5 KCl, 1 MgCl2, and 2.5 CaCl2, pH 7.4) containing 3 mM d-glucose and 0.1% BSA. Groups of 15 islets were counted into 10 × 75 mm siliconized borosilicate tubes and preincubated for 30 min in 200 μl of the same buffer. The preincubation buffer was removed, glucose-stimulated insulin secretion was initiated by addition of 200 μl of fresh Krebs-Ringer bicarbonate buffer containing 3 or 20 mM d-glucose, and the preparation was incubated for 45 min. Preincubation and incubation were done under 95% air-5% CO2 at 37°C with shaking. Insulin accumulating in the incubation buffer was measured using the Human Insulin Pincer assay kit (Mediomics, St. Louis, MO) (28). The Institutional Animal Care and Use Committees at the Medical College of Wisconsin and Saint Louis University approved all animal care and experimental procedures.

Cell viability.

Cell viability was determined using the neutral red dye uptake assay, as described previously (9, 66, 76). After treatment of RINm5F cells (2.0 × 105 cells/400 μl RPMI 1640 medium), the culture medium was supplemented with neutral red (40 μg/ml), and the cells were incubated for 1 h at 37°C. The supernatant was removed by aspiration and discarded, and the cells were washed and fixed with a 1% formaldehyde-1% CaCl2 solution. Neutral red was extracted from the cells in 200 μl of 50% ethanol-1% acetic acid. The optical density of neutral red was determined at 540 nm. The percentage of dead cells was determined by comparison of neutral red uptake of treated samples with neutral red uptake of the untreated control (set at 100%).

Caspase assay.

Caspase-3/7 activity was measured using a protocol published by Carrasco et al. (13). After treatment of RINm5F cells (2.0 × 105 cells/400 μl RPMI 1640 medium), 200 μl of 3× caspase assay buffer (150 mM HEPES, 450 mM NaCl, 150 mM KCl, 30 mM MgCl2, 1.2 mM EGTA, 1.5% Nonidet P-40, 0.3% CHAPS, 30% sucrose, 0.2 mM PMSF, 2 mM DTT, and 10 μM DEVD-7-amidino-4-methylcoumarin) were added to the cells in a 24-well plate, and the preparation was incubated for 1 h at 37°C. Proteolytic release of the fluorochrome was measured by spectroscopy at an excitation of 360 nm and an emission of 460 nm.

PCR.

Isolation of RNA from insulinoma cells was accomplished using the RNeasy kit according to the manufacturer's specifications (Qiagen). Samples were then digested with DNase (TURBO DNA-free kit, Ambion), and cDNA synthesis was performed using oligo(dT) and reverse transcriptase SuperScript Preamplification System according to the manufacturer's instructions (Invitrogen). Real-time PCR was performed using a LightCycler 480 (Roche Applied Biosciences) to detect SYBR Green fluorescence according to the manufacturer's instructions. Fold increases in CHOP, spliced X-box binding protein 1 [XBP1(s)], and activating transcription factor 3 (ATF3) mRNA accumulation were each normalized to β-actin mRNA. Primer sequences were as follows: 5′-AAATAACAGCCGGAACCTGA-3′ (forward) and 5′-GGGATGCAGGGTCAAGAGTA-3′ (reverse) for CHOP, 5′-TGAGTCCGCAGCAGGTG-3′ (forward) and 5′-CAGCGTCAGAATCCATGGGAA-3′ (reverse) for XBP1(s), 5′-GCTGGAGTCAGTCACCATCA-3′ (forward) and 5′-ACACTTGGCAGCAGCAATTT-3′ (reverse) for ATF3, and 5′-CACCCGCGAGTACAACCTTC-3′ (forward) and 5′-CCCATACCCACCATCACACC-3′ (reverse) for β-actin.

Western blot analysis.

RINm5F cells were washed with PBS and lysed in immunoprecipitation lysis buffer [20 mM Tris, pH 7.5, 150 mM NaCl, 2 mM EDTA, 2 mM EGTA, 0.5% Nonidet P-40, 1 mM sodium orthovanadate, 0.1 mM PMSF, 50 mM NaF, and protease inhibitor cocktail (Sigma, St. Louis, MO)]. The lysates were disrupted by sonication and then cleared by centrifugation (16,000 g for 15 min). Protein concentrations were determined by the Bradford assay (Pierce, Rockford, IL). Samples were mixed with Laemmli sample buffer (2% SDS) and boiled for 5 min. Proteins were resolved by SDS-PAGE and transferred to nitrocellulose, and the membranes were incubated overnight with primary antibody (1:1,000 dilution) at 4°C and then for 1 h with horseradish peroxidase-conjugated donkey anti-rabbit or donkey anti-mouse secondary antibody (1:10,000 dilution), and antigen was detected by chemiluminescence.

Metabolic labeling of palmitoylated proteins.

RINm5F cells (2.0 × 106 cells/2 ml RPMI 1640 medium) were pretreated with 100 μM 2BrP for 3 h, [9,10-3H(N)]palmitate was added, and culture was continued for 4 h. To avoid dilution of label, the ratio of [3H]palmitate to cold palmitate was held constant at 1.6 μCi of [3H]palmitate per nanomole of palmitate across the different palmitate treatment conditions. At this ratio, 160 μCi of [3H]palmitate was added to cells treated with 100 μM cold palmitate. The cells were washed in PBS and lysed [20 mM Tris, pH 7.5, 150 mM NaCl, 1% Nonidet P-40, 0.5% Na-deoxycholate, 1 mM EDTA, 0.1% SDS, 1 mM Na3VO4, 0.1 mM PMSF, 50 mM NaF, and protease inhibitor cocktail (Sigma-Aldrich)]. After removal of insoluble material by centrifugation, proteins were precipitated with 10% trichloroacetic acid (TCA), washed with ice-cold ether to remove the TCA, and then solubilized in Laemmli buffer (without β-mercaptoethanol). Protein was separated by SDS-PAGE, and labeled proteins were visualized by fluorography (Autofluor, National Diagnostics).

Palmitate esterification and oxidation.

Fatty acid oxidation in RINm5F cells, treated for 5 h with 400 μM palmitate + 5 μCi of [1-14C]palmitate with or without 100 μM 2BrP or 200 μM etomoxir, was determined by measurement of [14C]CO2 released according to the method of Parker et al. (60).

Statistics.

Statistical analyses were performed using one-way ANOVA with Tukey-Kramer post hoc test or two-way ANOVA with Bonferroni's post hoc test. Values are means ± SE.

RESULTS

Unsaturated 16- and 18-carbon fatty acids are toxic to β-cells.

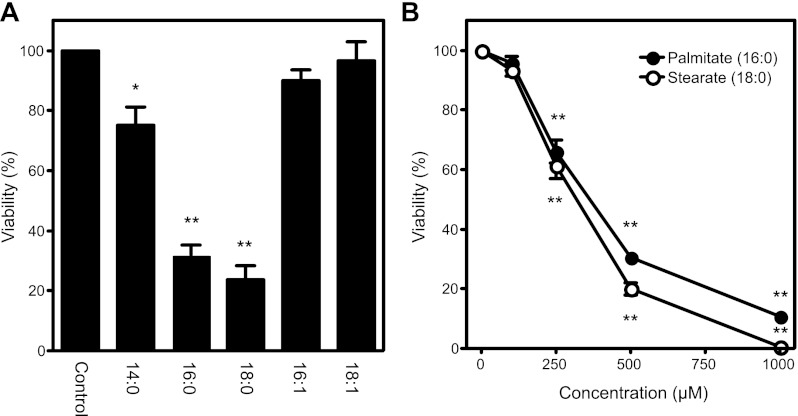

The effects of saturated and unsaturated fatty acid treatment on the viability of RINm5F cells were evaluated using the neutral red assay (Fig. 1A). Consistent with previous reports (82), differences in the length and saturation of fatty acids have profound effects on toxicity. Treatment of RINm5F cells with the long-chain saturated fatty acids palmitate (C16:0) and stearate (C18:0) results in significant cell death following 24 h of incubation at 500 μM. In contrast, monounsaturated fatty acids of equivalent length, palmoleate (C16:1) and oleate (C18:1), are not toxic to RINm5F cells. Myristate (C14:0) is a shorter-chain saturated fatty acid that is much less toxic than longer-chain (C16 and C18) fatty acids (∼70% and ∼30% viability, respectively) but more toxic than monounsaturated fatty acids. The toxic effect of palmitate and stearate (0–1,000 μM) on RINm5F cell viability is concentration-dependent, with half-maximal death at FFA concentrations of ∼300 μM (Fig. 1B).

Fig. 1.

Loss of viability of insulinoma cells treated with free fatty acids (FFAs). A: RINm5F cells were treated for 24 h with 500 μM myristate (14:0), 500 μM palmitate (16:0), 500 μM stearate (18:0), 500 μM palmitolate (16:1), or 500 μM oleate (18:1). B: RINm5F cells were treated for 24 h with palmitate or stearate (0–1,000 μM), and cell viability was determined using the neutral red uptake assay. Values are means ± SE of 3 individual experiments. Statistically significant loss of viability: *P < 0.05; **P < 0.001.

Inhibition of de novo ceramide synthesis does not attenuate β-cell death.

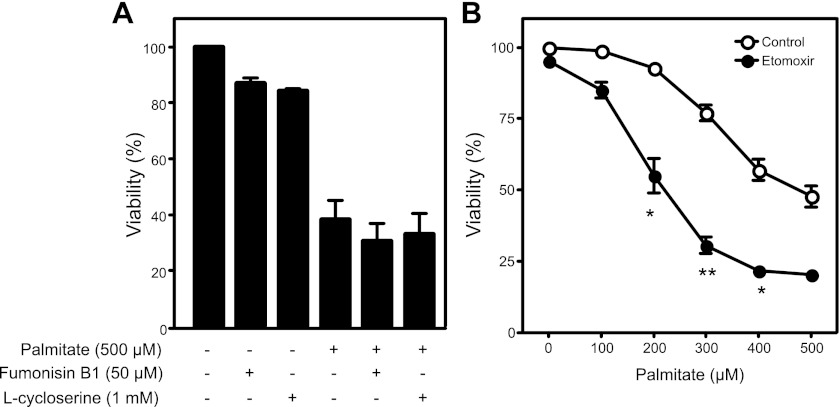

The sphingolipid ceramide, a signaling molecule known to induce apoptosis, has been proposed as a mediator of palmitate-induced β-cell toxicity (61, 73). The observation that saturated FFAs with >14 carbons induce apoptosis is consistent with this hypothesis, as the rate-limiting step in de novo ceramide synthesis is catalyzed by serine palmitoyltransferase, an enzyme with a marked substrate preference for palmitoyl-CoA (43). Thus ceramide production may be expected to increase in cells exposed to excess palmitate. To examine the potential role of ceramide induction in palmitate-induced death, chemical inhibitors of de novo ceramide synthesis were employed. Pharmacological blockade of ceramide-generating enzymes with l-cycloserine, an inhibitor of serine palmitoyltransferase, or fumonisin B1, an inhibitor of ceramide synthase, does not attenuate palmitate-mediated RINm5F cell death (Fig. 2A). These findings are consistent with previous reports showing that inhibition of ceramide generation does not modify FFA-mediated β-cell death (54, 82).

Fig. 2.

Role of ceramide synthesis and β-oxidation in palmitate-induced cell toxicity. A: RINm5F cells were treated for 24 h with the ceramide synthesis inhibitors fumonisin B1 (50 μM) or l-cycloserine (1 mM) with or without palmitate (500 μM). B: RINm5F cells were treated for 24 h with 0–500 μM palmitate with or without 0.2 mM etomoxir, an inhibitor of mitochondrial long-chain fatty acid oxidation, and cell viability was determined using the neutral red uptake assay. Values are means ± SE of 3 individual experiments. Statistically significant loss of viability: *P < 0.05; **P < 0.001.

Carnitine palmitoyltransferase 1 inhibition enhances palmitate-induced β-cell death.

Chronic hyperglycemia increases glucose metabolism through oxidative phosphorylation, resulting in mitochondrial dysfunction and production of reactive oxygen species (ROS) (11, 77). Similarly, β-oxidation of FFAs may produce ROS via increased oxidative phosphorylation. Therefore, it is possible that inhibition of ROS production via inhibition of β-oxidation may protect β-cells from palmitate toxicity (69). Carnitine palmitoyltransferase 1 (CPT1) is responsible for the transport of long-chain FFAs into the mitochondria; therefore, inhibition of CPT1 should attenuate mitochondrial oxidation of long-chain FFA substrates. Across a range of palmitate concentrations (100–500 μM), inhibition of CPT1 with etomoxir (200 μM) fails to attenuate palmitate-mediated β-cell death (Fig. 2B). In fact, etomoxir exaggerates β-cell death at each concentration of palmitate examined, achieving statistical significance at ≥200 μM palmitate. Similar results have been obtained using INS 832/13 cells and with additional inhibitors of CPT1 (data not shown). The enhanced toxicity of palmitate in CPT1-inhibited cells is consistent with previous studies (22, 27) and suggests that β-oxidation of FFAs does not contribute to palmitate toxicity but may provide protection from excess FFA (22, 27).

2BrP attenuates palmitate-induced β-cell death.

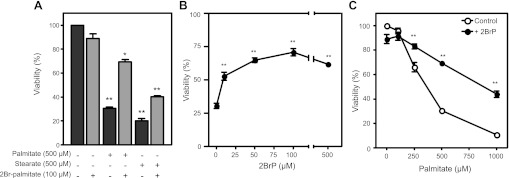

2BrP, an analog of palmitate that is not metabolized, has been used as a classical inhibitor of G protein signaling because of its ability to attenuate palmitoylation of the Gα subunit (33, 67). Pretreatment of RINm5F cells with 100 μM 2BrP more than doubles the number of viable cells after 24 h of treatment with 500 μM palmitate (Fig. 3A). 2BrP treatment also attenuates death induced by the longer saturated FFA stearate (Fig. 3A). The beneficial actions of 2BrP are concentration-related, with 100 μM 2BrP providing maximal protection (Fig. 3B). In addition, 2BrP is effective at attenuating cell death at all toxic concentrations of palmitate employed (Fig. 3C). These findings suggest that aberrant protein palmitoylation may contribute to FFA toxicity of β-cells.

Fig. 3.

2-Bromopalmitate (2BrP) attenuates saturated FFA-induced cell death. A: RINm5F cells were treated with palmitate (500 μM) with or without 2BrP (100 μM) or with stearate (500 μM) with or without 2BrP (100 μM) for 24 h, and cell viability was examined. B: concentration-dependent effects of 2BrP on palmitate-induced cell death following a 24-h incubation. C: concentration-dependent effects of 24-h incubation with palmitate on RINm5F cell viability in the presence and absence of 2BrP (100 μM). Cell viability was determined using the neutral red uptake assay. Values are means ± SE of 3 individual experiments. Statistically significant loss of viability compared with control, untreated cells: *P < 0.05; **P < 0.001. Enhanced viability of cells treated with 50 vs. 10 μM 2BrP and with 100 vs. 10 μM 2BrP achieved statistical significance (P < 0.05).

2BrP does not attenuate β-oxidation.

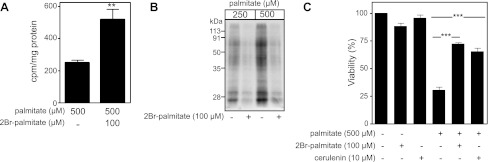

Since 2BrP has been described as an inhibitor of protein palmitoylation and mitochondrial β-oxidation, the effects of this analog on both events were evaluated. Several studies have used the brominated analog of palmitate as an inhibitor of fatty acid oxidation (14, 15); however, the decrease in RINm5F cell viability in the presence of palmitate and etomoxir, a known inhibitor of CPT1, suggests that 2BrP does not provide protection by blocking mitochondrial β-oxidation (Fig. 2B). With use of [14C]palmitate, β-oxidation in palmitate-treated RINm5F cells with and without 2BrP was measured. At a concentration that attenuates palmitate-induced cell death (100 μM), 2BrP fails to attenuate the β-oxidation of [14C]palmitate (Fig. 4A). In fact, 2BrP enhances mitochondrial β-oxidation by nearly twofold. These findings are consistent with previous studies (60) and suggest that palmitate-induced β-cell damage is not mediated by mitochondrial oxidation of long-chain fatty acids.

Fig. 4.

2BrP inhibits protein S-acylation. A: 14CO2 end products from fatty acid oxidation of [1-14C]palmitate in RINm5F cells after 5 h of culture with or without 2BrP (100 μM). B: RINm5F cells were pretreated with or without 2BrP (100 μM) for 3 h before addition of [3H]palmitate and incubation for another 4 h. Cells were lysed, and proteins were separated by SDS-PAGE and visualized by fluorography. Data are representative of results from 2 independent experiments. C: RINm5F cells were treated with or without palmitate (500 μM) in the presence of 2BrP (100 μM) or cerulenin (10 μM) for 24 h, and cell viability was determined using the neutral red uptake assay. Values are means ± SE of 3 individual experiments. Statistically significant changes: *P < 0.01; ***P < 0.001.

Since 2BrP is effective at preventing cell death in response to palmitate and this occurs in the absence of an inhibition of β-oxidation, the effects of 2BrP on protein palmitoylation were examined. For these studies, RINm5F cells were labeled with [3H]palmitate in the presence and absence of cold 2BrP, proteins were precipitated using TCA, and [3H]palmitate incorporation into protein was determined by gel electrophoresis and visualized by fluorography. As shown in Fig. 4B, 2BrP attenuates [3H]palmitate incorporation into RINm5F cell protein at palmitate concentrations known to induce β-cell death. These findings establish an association between the inhibition of palmitate-induced cell death by 2BrP and the inhibition of protein palmitoylation. This protective effect of 2BrP on cell viability suggests that enhanced or unregulated posttranslational modifications of proteins may be one mechanism by which palmitate is toxic to insulinoma cells. To further address this issue, the effects of an additional inhibitor of protein palmitoylation on palmitate-induced RINm5F cell death were examined. Cerulenin (2,3-epoxy-4-oxo-7,10-dodecadienoylamide) is a structurally independent inhibitor of protein palmitoylation (17, 34, 39) that functions much like 2BrP, as it attenuates RINm5F cell death induced by 500 μM palmitate (Fig. 4C). These findings suggest that the loss of β-cell viability in response to palmitate treatment may be associated with increased levels of posttranslational protein palmitoylation.

2BrP attenuates induction of palmitate-induced ER stress.

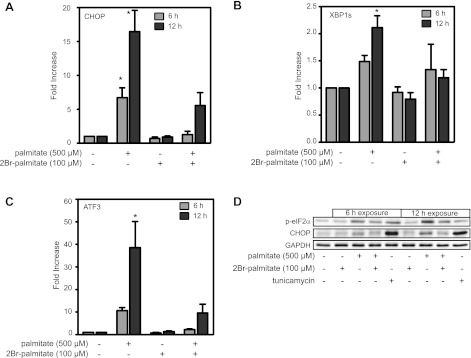

Several studies have suggested that ER stress may promote apoptosis in response to elevated FFAs (18, 35, 38). ER stress can be induced by a number of pathways, including impaired protein folding or unregulated posttranslational modifications such as palmitoylation. Since studies have identified ER stress in FFA-treated β-cells and inhibition of protein palmitoylation protects RINm5F cells from palmitate-induced death, the effects of 2BrP on the induction of ER stress markers in palmitate-treated RINm5F cells were examined. Consistent with previous studies, treatment of RINm5F cells with 500 μM palmitate results in the accumulation of CHOP and ATF3 mRNA and the splicing of XBP1 mRNA following 6 and 12 h of incubation (Fig. 5, A–C). Consistent with the protection from palmitate-induced toxicity, 2BrP attenuates ER stress gene mRNA accumulation and XBP1 splicing.

Fig. 5.

2BrP attenuates induction of endoplasmic reticulum (ER) stress in FFA-treated cells. A–C: RINm5F cells were treated with palmitate (500 μM) and/or 2BrP (100 μM) for 6 and 12 h. Total RNA was isolated, and C/EBP homologous protein (CHOP, A), spliced X-box binding protein-1 (XBP1, B), or activating transcription factor-3 (ATF3, C) mRNA accumulation was detected by real-time PCR and normalized to β-actin levels. Values are means ± SE of 3 individual experiments. Statistically significant changes in mRNA accumulation: *P < 0.05. D: under conditions similar to those described for A–C, palmitate induces CHOP expression and eukaryotic initiation factor-2α (eIF2α) phosphorylation (p-eIF2α) as determined by Western blot analysis. Tunicamycin (2 μg/ml) was used as a positive control for induction of ER stress. Data are representative of results from 3 individual experiments.

The induction of ER stress was also examined at the protein level. In response to palmitate, there are increased levels of CHOP accumulation and enhanced phosphorylation of eIF2α in RINm5F cells, and these effects are attenuated by 2BrP (Fig. 5D). These findings confirm that ER stress is induced by palmitate and suggest that 2BrP mediated improvement in cell viability by preventing palmitate-induced ER stress.

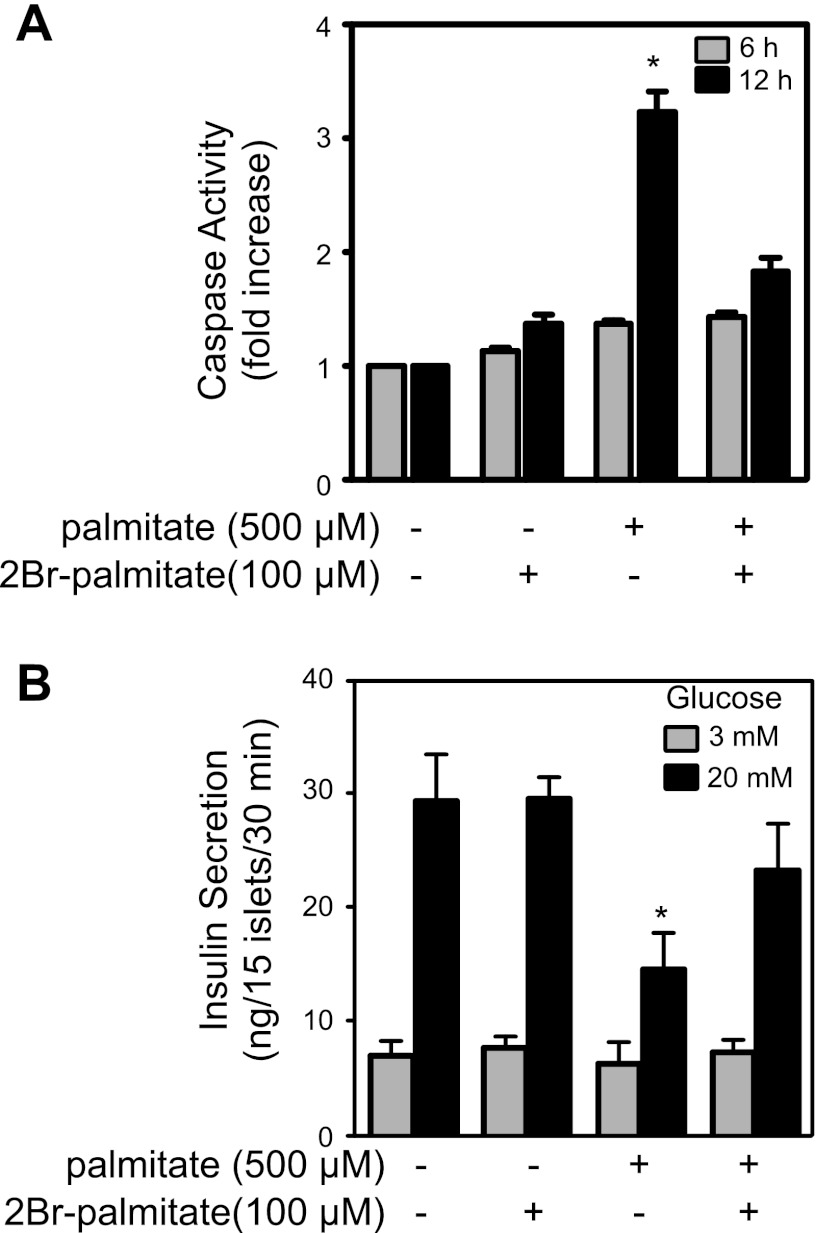

2BrP inhibits palmitate-induced caspase-3/7 activity.

A consequence of prolonged ER stress activation is the induction of apoptotic cascades, which are mediated by the activation of caspases. Caspase-3 and caspase-7 are executioner caspases responsible for the proteolytic cleavage of a broad spectrum of cellular targets, leading to apoptotic death. To determine whether the increased expression of ER stress markers is associated with the induction of apoptosis, the effects of palmitate treatment on caspase-3 and caspase-7 activity was examined. Treatment of RINm5F cells for 12 h with palmitate results in a 3.4-fold increase in caspase-3/7 activity (Fig. 6A). The palmitoylation inhibitor 2BrP, which prevents palmitate-induced ER stress induction and RINm5F cell death, also prevents palmitate-induced caspase-3/7 activation (Fig. 6A).

Fig. 6.

2BrP attenuates FFA induction of caspase-3/7 activity and inhibition of insulin secretion. A: RINm5F cells were treated with palmitate (500 μM) in the presence or absence of 2BrP (100 μM) for 6 and 12 h, cells were lysed, and caspase-3/7 activity was measured. Values are means ± SE of 3 individual experiments containing 3 replicates per condition. B: isolated rat islets were treated with palmitate (500 μM) and/or 2BrP (100 μM) for 48 h, and glucose-stimulated insulin secretion was examined. Values are means ± SE of 3 independent rat islet isolations. *P < 0.05.

2BrP attenuates palmitate-induced suppression of insulin secretion by rat islets.

Similar to the protective actions of 2BrP on the viability of insulinoma cells treated with palmitate, this inhibitor of protein palmitoylation also attenuates the inhibitory actions of palmitate on glucose-induced insulin secretion. A 48-h incubation of isolated rat islets with palmitate (500 μM) does not modify basal insulin secretion (3 mM glucose) but inhibits insulin secretion in response to elevated concentration (20 mM) of glucose (Fig. 6B). Alone, 2BrP (100 μM) does not modify glucose-stimulated insulin secretion under basal or stimulatory conditions. However, 2BrP attenuates the inhibitory actions of 500 μM palmitate on insulin in response to a maximal concentration of glucose (Fig. 6B).

DISCUSSION

Elevated FFA levels are apparent in overweight and obese individuals prior to the onset of hyperglycemia, and accumulating evidence suggests that prolonged exposure to elevated lipid concentrations is detrimental to pancreatic β-cells. Upon entry into cells, palmitate is thioesterified to coenzyme A by fatty acyl-CoA synthase, yielding palmitoyl-CoA. This activated fatty acid is available for oxidation, triglyceride formation, ceramide conversion, and as a substrate for posttranslational modification of proteins. Storage of excess fatty acid as triglyceride has been positively and negatively correlated with fatty acid-induced death of β-cells (10, 12, 23, 74). Elevated FFA may also serve as substrate driving an increase in β-oxidation, which may enhance ROS production, and uncoupling protein-2 expression, which leads to a deterioration in islet function and β-cell viability (43, 71, 81). Other reports suggest that increased mitochondrial oxidation of fatty acids does not cause β-cell lipotoxicity (22, 27). In this report, we show that etomoxir-mediated inhibition of β-oxidation exaggerates palmitate toxicity, a finding that is consistent with a potential protective role for mitochondrial palmitoyl-CoA oxidation.

The ability of β-cells to oxidize fatty acyl-CoAs or incorporate them into triglycerides may protect against the toxic actions of FFAs by reducing the concentration of palmitoyl-CoA available for protein palmitoylation. Protein palmitoylation is the posttranslational process in which fatty acids, primarily the saturated 16-carbon palmitate, are bound to cysteine residues via a thioester linkage. Attachment of this long-chain fatty acid increases a protein's hydrophobicity, allowing for membrane association, in addition to its function as a lipid membrane anchor (25). Palmitoylation also influences protein trafficking between cellular compartments, protein movement between membrane microdomains, protein stability, protein activity, and protein-protein interaction (26, 31, 67, 75). Unlike other lipid protein modifications, palmitoylation is highly dynamic, and palmitoylation and depalmitoylation cycles can regulate protein function and localization (83).

While protein palmitoylation is believed to be catalyzed by a family of palmitoyltransferases, early biochemical studies failed to isolate proteins with palmitoyltransferase activity (3, 36, 44), and a consensus sequence for the modification site has yet to be identified (4). Furthermore, proteins containing target cysteine residues can be autoacylated in vitro in the presence of palmitoyl-CoA (5, 21, 79). The spontaneous nature of this modification (20) suggests that autoacylation of proteins may increase in the presence of elevated donor groups, and studies examining acylation-dependent trafficking of peripheral membrane proteins suggest that the selection of substrates by the cellular palmitoylation machinery may be indiscriminate (30, 68). On the basis of these studies, it has been proposed that any mammalian protein that contains a surface-exposed cysteine and has transient access to a Golgi membrane may be qualified for palmitoylation (30, 68).

Since protein palmitoylation influences protein trafficking, protein stability, and protein aggregation, aberrant or uncontrolled protein palmitoylation could disrupt many of these events, including anterograde and endocytic trafficking of membrane proteins, inappropriate lateral segregation of proteins into membrane lipid microdomains, or interference with palmitate anchors in heterotrimeric G protein subunit recycling. Under conditions of uncontrolled protein palmitoylation, each one of these events could introduce ER stress in cells. Furthermore, disruptions in protein turnover can result from enhanced palmitoylation by attenuating degradation by interfering with ubiquitinylation (1). Therefore, if removal of palmitoyl groups is necessary for proteasomal degradation, the aberrant palmitoylation or mispalmitoylation could introduce ER stress via inappropriate protein turnover. Indiscriminate attachment of hydrophobic fatty acids to surface cysteine residues could also conceivably present a population of sticky molecules primed to aggregate and drive ER stress.

Because recent studies have associated ER stress with lipotoxicity and unregulated palmitoylation could be a potent activator of ER stress, the effects of inhibitors of protein palmitoylation on insulinoma cell viability were examined. The classical inhibitor of protein palmitoylation, 2BrP, significantly attenuates the toxicity of the long-chain saturated fatty acids palmitate and stearate. Importantly, stearate has been identified as an additional species involved in S-palmitoylation of proteins (42, 55); thus the protection from stearate toxicity afforded by 2BrP is consistent with a palmitoylation mechanism. The effects of 2BrP on palmitate-induced ER stress were also examined. Consistent with previous studies, we found that palmitate induces the accumulation of mRNA of the ER stress response genes CHOP and ATF3, phosphorylation of eIF2α, and the increased splicing of XBP1, actions that are attenuated by treatment with 2BrP. Because prolonged ER stress can culminate in programmed cell death, we examined the effect of 2BrP on palmitate-induced caspase-3 activity. Palmitate treatment significantly enhanced caspase-3 activity in RINm5F cells following 6- and 12-h exposures. Consistent with the attenuation of ER stress, the presence of 2BrP inhibited palmitate-stimulated caspase-3 activity. Using primary rodent islets, we also show that 2BrP attenuates the inhibitory actions of palmitate on glucose-stimulated insulin secretion.

2BrP has been described as a promiscuous inhibitor (15), characterized as an inhibitor of mitochondrial β-oxidation (14, 48), in addition to its inhibition of palmitoylation. To address the specificity of this inhibitor, we examined 2BrP's effect on the incorporation of activated fatty acids into cellular proteins, as well as its effects on FFA oxidation. We show that 2BrP functions as an effective inhibitor of palmitate incorporation into β-cell proteins. Importantly, 2BrP does not inhibit mitochondrial oxidation of palmitate; if anything, 2BrP appears to increase oxidation of palmitate, a result consistent with a palmitoyl-CoA pool further increased by preventing its consumption via acylation. These findings suggest that the protective effects of 2BrP on palmitate-induced toxicity may be mediated by moderating uncontrolled palmitoylation, a finding that is consistent with the protective effects of a second lipid-based inhibitor of protein palmitoylation, cerulenin.

We have examined a number of potential mechanisms to explain palmitate toxicity in insulinoma cells and rat islets. Consistent with many previous studies, we find that palmitate is toxic to β-cells and that this toxicity is associated with enhanced ER stress. Inhibition of palmitate oxidation appears to enhance cell death, while inhibition of protein palmitoylation protects against palmitate-induced toxicity. On the basis of these observations, we propose a novel mechanism to explain the toxicity of FFA. This mechanism suggests that palmitate-induced toxicity is a consequence of uncontrolled protein palmitoylation, resulting in ER stress and apoptosis.

GRANTS

This work was supported by National Institutes of Health Grants DK-52194 and AI-44458 (J. A. Corbett).

DISCLOSURES

No conflicts of interest, financial or otherwise, are declared by the authors.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

A.C.B., L.K.O., M.A.M., and J.A.C. are responsible for conception and design of the research; A.C.B., C.D.G., L.K.O., and M.A.M. performed the experiments; A.C.B., C.D.G., L.K.O., M.A.M., and J.A.C. analyzed the data; A.C.B., C.D.G., L.K.O., M.A.M., and J.A.C. interpreted the results of the experiments; A.C.B., M.A.M., and J.A.C. prepared the figures; A.C.B. and J.A.C. drafted the manuscript; A.C.B., L.K.O., and J.A.C. edited and revised the manuscript; A.C.B., L.K.O., M.A.M., and J.A.C. approved the final version of the manuscript.

REFERENCES

- 1.Abrami L, Leppla SH, van der Goot FG. Receptor palmitoylation and ubiquitination regulate anthrax toxin endocytosis. J Cell Biol 172: 309–320, 2006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bachar E, Ariav Y, Ketzinel-Gilad M, Cerasi E, Kaiser N, Leibowitz G. Glucose amplifies fatty acid-induced endoplasmic reticulum stress in pancreatic β-cells via activation of mTORC1. PLos One 4: e4954, 2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Berthiaume L, Resh MD. Biochemical characterization of a palmitoyl acyltransferase activity that palmitoylates myristoylated proteins. J Biol Chem 270: 22399–22405, 1995 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bijlmakers MJ, Marsh M. The on-off story of protein palmitoylation. Trends Cell Biol 13: 32–42, 2003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bizzozero OA, Bixler HA, Pastuszyn A. Structural determinants influencing the reaction of cysteine-containing peptides with palmitoyl-coenzyme A and other thioesters. Biochim Biophys Acta 1545: 278–288, 2001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Boden G, Chen X, Ruiz J, White JV, Rossetti L. Mechanisms of fatty acid-induced inhibition of glucose uptake. J Clin Invest 93: 2438–2446, 1994 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bonapace G, Waheed A, Shah GN, Sly WS. Chemical chaperones protect from effects of apoptosis-inducing mutation in carbonic anhydrase IV identified in retinitis pigmentosa 17. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 101: 12300–12305, 2004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Boni-Schnetzler M, Boller S, Debray S, Bouzakri K, Meier DT, Prazak R, Kerr-Conte J, Pattou F, Ehses JA, Schuit FC, Donath MY. Free fatty acids induce a proinflammatory response in islets via the abundantly expressed interleukin-1 receptor I. Endocrinology 150: 5218–5229, 2009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Borenfreund E, Puerner JA. Toxicity determined in vitro by morphological alterations and neutral red absorption. Toxicol Lett 24: 119–124, 1985 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Briaud I, Harmon JS, Kelpe CL, Segu VB, Poitout V. Lipotoxicity of the pancreatic β-cell is associated with glucose-dependent esterification of fatty acids into neutral lipids. Diabetes 50: 315–321, 2001 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Brownlee M. Biochemistry and molecular cell biology of diabetic complications. Nature 414: 813–820, 2001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Busch AK, Gurisik E, Cordery DV, Sudlow M, Denyer GS, Laybutt DR, Hughes WE, Biden TJ. Increased fatty acid desaturation and enhanced expression of stearoyl coenzyme A desaturase protects pancreatic β-cells from lipoapoptosis. Diabetes 54: 2917–2924, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Carrasco RA, Stamm NB, Patel BK. One-step cellular caspase-3/7 assay. Biotechniques 34: 1064–1067, 2003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Chase JF, Tubbs PK. Specific inhibition of mitochondrial fatty acid oxidation by 2-bromopalmitate and its coenzyme A and carnitine esters. Biochem J 129: 55–65, 1972 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Coleman RA, Rao P, Fogelsong RJ, Bardes ES. 2-Bromopalmitoyl-CoA and 2-bromopalmitate: promiscuous inhibitors of membrane-bound enzymes. Biochim Biophys Acta 1125: 203–209, 1992 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Cunha DA, Hekerman P, Ladriere L, Bazarra-Castro A, Ortis F, Wakeham MC, Moore F, Rasschaert J, Cardozo AK, Bellomo E, Overbergh L, Mathieu C, Lupi R, Hai T, Herchuelz A, Marchetti P, Rutter GA, Eizirik DL, Cnop M. Initiation and execution of lipotoxic ER stress in pancreatic β-cells. J Cell Sci 121: 2308–2318, 2008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.DeJesus G, Bizzozero OA. Effect of 2-fluoropalmitate, cerulenin and tunicamycin on the palmitoylation and intracellular translocation of myelin proteolipid protein. Neurochem Res 27: 1669–1675, 2002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Diakogiannaki E, Morgan NG. Differential regulation of the ER stress response by long-chain fatty acids in the pancreatic β-cell. Biochem Soc Trans 36: 959–962, 2008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Diakogiannaki E, Welters HJ, Morgan NG. Differential regulation of the endoplasmic reticulum stress response in pancreatic β-cells exposed to long-chain saturated and monounsaturated fatty acids. J Endocrinol 197: 553–563, 2008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Dietrich LE, Ungermann C. On the mechanism of protein palmitoylation. EMBO Rep 5: 1053–1057, 2004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Duncan JA, Gilman AG. Autoacylation of G protein α-subunits. J Biol Chem 271: 23594–23600, 1996 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.El-Assaad W, Buteau J, Peyot ML, Nolan C, Roduit R, Hardy S, Joly E, Dbaibo G, Rosenberg L, Prentki M. Saturated fatty acids synergize with elevated glucose to cause pancreatic β-cell death. Endocrinology 144: 4154–4163, 2003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.El-Assaad W, Joly E, Barbeau A, Sladek R, Buteau J, Maestre I, Pepin E, Zhao S, Iglesias J, Roche E, Prentki M. Glucolipotoxicity alters lipid partitioning and causes mitochondrial dysfunction, cholesterol, and ceramide deposition and reactive oxygen species production in INS832/13 ss-cells. Endocrinology 151: 3061–3073, 2010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Gordon RS., Jr Metabolism of serum-free fatty acids. Fed Proc 19 Suppl 5: 120–121, 1960 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Greaves J, Chamberlain LH. Palmitoylation-dependent protein sorting. J Cell Biol 176: 249–254, 2007 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Greaves J, Prescott GR, Gorleku OA, Chamberlain LH. The fat controller: roles of palmitoylation in intracellular protein trafficking and targeting to membrane microdomains. Mol Membr Biol 26: 67–79, 2009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Hellemans K, Kerckhofs K, Hannaert JC, Martens G, Van Veldhoven P, Pipeleers D. Peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor α-retinoid X receptor agonists induce β-cell protection against palmitate toxicity. FEBS J 274: 6094–6105, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Heyduk E, Moxley MM, Salvatori A, Corbett JA, Heyduk T. Homogeneous insulin and C-peptide sensors for rapid assessment of insulin and C-peptide secretion by the islets. Diabetes 59: 2360–2365, 2010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Hotamisligil GS. Endoplasmic reticulum stress and the inflammatory basis of metabolic disease. Cell 140: 900–917, 2010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Hou H, John Peter AT, Meiringer C, Subramanian K, Ungermann C. Analysis of DHHC acyltransferases implies overlapping substrate specificity and a two-step reaction mechanism. Traffic 10: 1061–1073, 2009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Huang K, El-Husseini A. Modulation of neuronal protein trafficking and function by palmitoylation. Curr Opin Neurobiol 15: 527–535, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Igoillo-Esteve M, Marselli L, Cunha DA, Ladriere L, Ortis F, Grieco FA, Dotta F, Weir GC, Marchetti P, Eizirik DL, Cnop M. Palmitate induces a pro-inflammatory response in human pancreatic islets that mimics CCL2 expression by beta cells in type 2 diabetes. Diabetologia 53: 1395–1405, 2010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Jiang X, Benovic JL, Wedegaertner PB. Plasma membrane and nuclear localization of G protein coupled receptor kinase 6A. Mol Biol Cell 18: 2960–2969, 2007 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Jochen AL, Hays J, Mick G. Inhibitory effects of cerulenin on protein palmitoylation and insulin internalization in rat adipocytes. Biochim Biophys Acta 1259: 65–72, 1995 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Karaskov E, Scott C, Zhang L, Teodoro T, Ravazzola M, Volchuk A. Chronic palmitate but not oleate exposure induces endoplasmic reticulum stress, which may contribute to INS-1 pancreatic β-cell apoptosis. Endocrinology 147: 3398–3407, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Kasinathan C, Grzelinska E, Okazaki K, Slomiany BL, Slomiany A. Purification of protein fatty acyltransferase and determination of its distribution and topology. J Biol Chem 265: 5139–5144, 1990 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Kaufman RJ. Stress signaling from the lumen of the endoplasmic reticulum: coordination of gene transcriptional and translational controls. Genes Dev 13: 1211–1233, 1999 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Kharroubi I, Ladriere L, Cardozo AK, Dogusan Z, Cnop M, Eizirik DL. Free fatty acids and cytokines induce pancreatic β-cell apoptosis by different mechanisms: role of nuclear factor-κB and endoplasmic reticulum stress. Endocrinology 145: 5087–5096, 2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Lawrence DS, Zilfou JT, Smith CD. Structure-activity studies of cerulenin analogues as protein palmitoylation inhibitors. J Med Chem 42: 4932–4941, 1999 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Laybutt DR, Preston AM, Akerfeldt MC, Kench JG, Busch AK, Biankin AV, Biden TJ. Endoplasmic reticulum stress contributes to beta cell apoptosis in type 2 diabetes. Diabetologia 50: 752–763, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Lazar MA. How obesity causes diabetes: not a tall tale. Science 307: 373–375, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Linder ME, Deschenes RJ. Palmitoylation: policing protein stability and traffic. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol 8: 74–84, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Listenberger LL, Ory DS, Schaffer JE. Palmitate-induced apoptosis can occur through a ceramide-independent pathway. J Biol Chem 276: 14890–14895, 2001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Liu L, Dudler T, Gelb MH. Purification of a protein palmitoyltransferase that acts on H-Ras protein and on a C-terminal N-Ras peptide. J Biol Chem 271: 23269–23276, 1996 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Lupi R, Dotta F, Marselli L, Del Guerra S, Masini M, Santangelo C, Patane G, Boggi U, Piro S, Anello M, Bergamini E, Mosca F, Di Mario U, Del Prato S, Marchetti P. Prolonged exposure to free fatty acids has cytostatic and pro-apoptotic effects on human pancreatic islets: evidence that β-cell death is caspase mediated, partially dependent on ceramide pathway, and Bcl-2 regulated. Diabetes 51: 1437–1442, 2002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Maedler K, Oberholzer J, Bucher P, Spinas GA, Donath MY. Monounsaturated fatty acids prevent the deleterious effects of palmitate and high glucose on human pancreatic β-cell turnover and function. Diabetes 52: 726–733, 2003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Maestre I, Jordan J, Calvo S, Reig JA, Cena V, Soria B, Prentki M, Roche E. Mitochondrial dysfunction is involved in apoptosis induced by serum withdrawal and fatty acids in the β-cell line INS-1. Endocrinology 144: 335–345, 2003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Mahadevan S, Sauer F. Effect of bromo-palmitate on the oxidation of palmitic acid by rat liver cells. J Biol Chem 246: 5862–5867, 1971 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Malhotra JD, Kaufman RJ. Endoplasmic reticulum stress and oxidative stress: a vicious cycle or a double-edged sword? Antioxid Redox Signal 9: 2277–2293, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Marchetti P, Bugliani M, Lupi R, Marselli L, Masini M, Boggi U, Filipponi F, Weir GC, Eizirik DL, Cnop M. The endoplasmic reticulum in pancreatic beta cells of type 2 diabetes patients. Diabetologia 50: 2486–2494, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Martinez SC, Tanabe K, Cras-Meneur C, Abumrad NA, Bernal-Mizrachi E, Permutt MA. Inhibition of Foxo1 protects pancreatic islet β-cells against fatty acid and endoplasmic reticulum stress-induced apoptosis. Diabetes 57: 846–859, 2008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.McDaniel ML, Colca JR, Kotagal N, Lacy PE. A subcellular fractionation approach for studying insulin release mechanisms and calcium metabolism in islets of Langerhans. Methods Enzymol 98: 182–200, 1983 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Mokdad AH, Ford ES, Bowman BA, Dietz WH, Vinicor F, Bales VS, Marks JS. Prevalence of obesity, diabetes, and obesity-related health risk factors, 2001. JAMA 289: 76–79, 2003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Moore PC, Ugas MA, Hagman DK, Parazzoli SD, Poitout V. Evidence against the involvement of oxidative stress in fatty acid inhibition of insulin secretion. Diabetes 53: 2610–2616, 2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Nadolski MJ, Linder ME. Protein lipidation. FEBS J 274: 5202–5210, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Newsholme P, Haber EP, Hirabara SM, Rebelato EL, Procopio J, Morgan D, Oliveira-Emilio HC, Carpinelli AR, Curi R. Diabetes associated cell stress and dysfunction: role of mitochondrial and non-mitochondrial ROS production and activity. J Physiol 583: 9–24, 2007 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Newsholme P, Keane D, Welters HJ, Morgan NG. Life and death decisions of the pancreatic β-cell: the role of fatty acids. Clin Sci (Lond) 112: 27–42, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Oprescu AI, Bikopoulos G, Naassan A, Allister EM, Tang C, Park E, Uchino H, Lewis GF, Fantus IG, Rozakis-Adcock M, Wheeler MB, Giacca A. Free fatty acid-induced reduction in glucose-stimulated insulin secretion: evidence for a role of oxidative stress in vitro and in vivo. Diabetes 56: 2927–2937, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Oyadomari S, Koizumi A, Takeda K, Gotoh T, Akira S, Araki E, Mori M. Targeted disruption of the Chop gene delays endoplasmic reticulum stress-mediated diabetes. J Clin Invest 109: 525–532, 2002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Parker SM, Moore PC, Johnson LM, Poitout V. Palmitate potentiation of glucose-induced insulin release: a study using 2-bromopalmitate. Metab Clin Exp 52: 1367–1371, 2003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Paumen MB, Ishida Y, Muramatsu M, Yamamoto M, Honjo T. Inhibition of carnitine palmitoyltransferase I augments sphingolipid synthesis and palmitate-induced apoptosis. J Biol Chem 272: 3324–3329, 1997 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Piro S, Anello M, Di Pietro C, Lizzio MN, Patane G, Rabuazzo AM, Vigneri R, Purrello M, Purrello F. Chronic exposure to free fatty acids or high glucose induces apoptosis in rat pancreatic islets: possible role of oxidative stress. Metab Clin Exp 51: 1340–1347, 2002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Poitout V, Amyot J, Semache M, Zarrouki B, Hagman D, Fontes G. Glucolipotoxicity of the pancreatic beta cell. Biochim Biophys Acta 1801: 289–298, 2010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Poitout V, Robertson RP. Glucolipotoxicity: fuel excess and β-cell dysfunction. Endocr Rev 29: 351–366, 2008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Preston AM, Gurisik E, Bartley C, Laybutt DR, Biden TJ. Reduced endoplasmic reticulum (ER)-to-Golgi protein trafficking contributes to ER stress in lipotoxic mouse beta cells by promoting protein overload. Diabetologia 52: 2369–2373, 2009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Repetto G, del Peso A, Zurita JL. Neutral red uptake assay for the estimation of cell viability/cytotoxicity. Nat Protoc 3: 1125–1131, 2008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Resh MD. Palmitoylation of ligands, receptors, and intracellular signaling molecules. Science STKE 2006: re14, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Rocks O, Gerauer M, Vartak N, Koch S, Huang ZP, Pechlivanis M, Kuhlmann J, Brunsveld L, Chandra A, Ellinger B, Waldmann H, Bastiaens PI. The palmitoylation machinery is a spatially organizing system for peripheral membrane proteins. Cell 141: 458–471, 2010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Rolo AP, Palmeira CM. Diabetes and mitochondrial function: role of hyperglycemia and oxidative stress. Toxicol Appl Pharmacol 212: 167–178, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Sabin MA, Stewart CE, Crowne EC, Turner SJ, Hunt LP, Welsh GI, Grohmann MJ, Holly JM, Shield JP. Fatty acid-induced defects in insulin signalling, in myotubes derived from children, are related to ceramide production from palmitate rather than the accumulation of intramyocellular lipid. J Cell Physiol 211: 244–252, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Schaffer JE. Lipotoxicity: when tissues overeat. Curr Opin Lipidol 14: 281–287, 2003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Shaw JE, Sicree RA, Zimmet PZ. Global estimates of the prevalence of diabetes for 2010 and 2030. Diabetes Res Clin Pract 87: 4–14, 2010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Shimabukuro M, Higa M, Zhou YT, Wang MY, Newgard CB, Unger RH. Lipoapoptosis in β-cells of obese prediabetic fa/fa rats. Role of serine palmitoyltransferase overexpression. J Biol Chem 273: 32487–32490, 1998 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Shimabukuro M, Zhou YT, Levi M, Unger RH. Fatty acid-induced beta cell apoptosis: a link between obesity and diabetes. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 95: 2498–2502, 1998 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Smotrys JE, Linder ME. Palmitoylation of intracellular signaling proteins: regulation and function. Annu Rev Biochem 73: 559–587, 2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Steer SA, Scarim AL, Chambers KT, Corbett JA. Interleukin-1 stimulates β-cell necrosis and release of the immunological adjuvant HMGB1. PLoS Med 3: e17, 2006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Tanaka Y, Gleason CE, Tran PO, Harmon JS, Robertson RP. Prevention of glucose toxicity in HIT-T15 cells and Zucker diabetic fatty rats by antioxidants. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 96: 10857–10862, 1999 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Unger RH. Lipotoxicity in the pathogenesis of obesity-dependent NIDDM. Genetic and clinical implications. Diabetes 44: 863–870, 1995 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Veit M, Sachs K, Heckelmann M, Maretzki D, Hofmann KP, Schmidt MF. Palmitoylation of rhodopsin with S-protein acyltransferase: enzyme catalyzed reaction versus autocatalytic acylation. Biochim Biophys Acta 1394: 90–98, 1998 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Wang H, Kouri G, Wollheim CB. ER stress and SREBP-1 activation are implicated in β-cell glucolipotoxicity. J Cell Sci 118: 3905–3915, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Wang X, Li H, De Leo D, Guo W, Koshkin V, Fantus IG, Giacca A, Chan CB, Der S, Wheeler MB. Gene and protein kinase expression profiling of reactive oxygen species-associated lipotoxicity in the pancreatic β-cell line MIN6. Diabetes 53: 129–140, 2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Welters HJ, Tadayyon M, Scarpello JH, Smith SA, Morgan NG. Mono-unsaturated fatty acids protect against β-cell apoptosis induced by saturated fatty acids, serum withdrawal or cytokine exposure. FEBS Lett 560: 103–108, 2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Yanai A, Huang K, Kang R, Singaraja RR, Arstikaitis P, Gan L, Orban PC, Mullard A, Cowan CM, Raymond LA, Drisdel RC, Green WN, Ravikumar B, Rubinsztein DC, El-Husseini A, Hayden MR. Palmitoylation of Huntington by HIP14 is essential for its trafficking and function. Nat Neurosci 9: 824–831, 2006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]