Abstract

Norepinephrine has for many years been known to have three major effects on the pancreatic β-cell which lead to the inhibition of insulin release. These are activation of K+ channels to hyperpolarize the cell and prevent the gating of voltage-dependent Ca2+ channels that increase intracellular Ca2+ concentration ([Ca2+]i) and trigger release; inhibition of adenylyl cyclases, thus preventing the augmentation of stimulated insulin release by cyclic AMP; and a “distal” effect that occurs downstream of increased [Ca2+]i to inhibit exocytosis. All three are mediated by the pertussis toxin (PTX)-sensitive heterotrimeric Gi and Go proteins. The distal inhibitory effect on exocytosis is now known to be due to the binding of G protein βγ subunits to the synaptosomal-associated protein of 25 kDa (SNAP-25) on the soluble NSF attachment protein receptor (SNARE) complex. Recent studies have uncovered two more actions of norepinephrine on the β-cell: 1) retardation of the refilling of the readily releasable granule pool after it has been discharged, an action that is mediated by Gαi1 and/or Gαi2; and 2) inhibition of endocytosis that is mediated by Gz. Of importance also are new findings that Gαo regulates the number of docked granules in the β-cell, and that Gαo2 maintains a tonic inhibitory influence on secretion. The latter provides another explanation as to why PTX, which blocks the effect of Gαo2, was initially called “islet activating protein.” Finally, there is clear evidence that overexpression of α2A-adrenergic receptors in β-cells can cause type 2 diabetes.

Keywords: pancreatic β-cell, K+ channels, adenylyl cyclases, exocytosis, granule pools, endocytosis

norepinephrine is responsible for multiple effects in the body as it acts as a hormone after its release from the adrenal medulla along with epinephrine, and as a neurotransmitter when released by the central and sympathetic nervous systems. It has important functions on the cardiovascular system, on muscle, liver, and adipose tissue, and in the control of whole body metabolism. This review, however, focuses on the effects of norepinephrine on the pancreatic β-cell and recent advances in our knowledge. Norepinephrine has three major effects on the β-cell that lead to the inhibition of insulin release (65, 74, 102, 104). It activates K+ channels to hyperpolarize the cell. This prevents or reverses depolarization and the consequent gating of voltage-dependent Ca2+ channels that increase intracellular Ca2+ concentration ([Ca2+]i) and trigger insulin release. It inhibits adenylyl cyclases, thus preventing the augmentation of stimulated insulin release, and it has a “distal” effect that occurs downstream of increased [Ca2+]i to inhibit exocytosis similar to that of serotonin in the central nervous system (CNS) (7) and endothelin in pituitary lactotrophs (3). There are additional reports that in some clonal β-cell lines the inhibitors reduce the activity of the L-type Ca2+ channels (38, 43). However, this effect has not been reported in primary β-cells. That the α2A-adrenergic receptor is responsible for these effects was deduced originally from studies with selective receptor agonists and antagonists (4, 83) and later from data on knockout mice (44, 89). Interestingly, while there is general agreement that the α2A-adrenergic receptor is the primary mediator of the inhibitory effects of norepinephrine, there is evidence that the α2C-adrenergic receptor could play a small role (89). Whether this is direct or indirect is not known. All the effects of norepinephrine to inhibit insulin release are mediated by activation of pertussis toxin (PTX)-sensitive heterotrimeric Gi and Go proteins (52–54, 61).

The effect of PTX to block hormonal inhibition of insulin release was first demonstrated in mice sensitized to PTX during vaccination studies in the 1960s (33, 118). Since 1978 when PTX was identified as the active principal in pertussis vaccines and its action was defined (55, 56, 133), it has been widely used to define signal transduction pathways that are mediated by the Gi/Go proteins. In the case of norepinephrine, all of its α2-adrenergic effects to inhibit insulin release are blocked by the treatment of animals, tissues, or cells with PTX (61). The Gi/Go proteins are ADP-ribosylated by PTX, a modification that renders them unable to interact with their receptors, as for example the α2-adrenergic receptors. PTX was initially named “islet activating protein” because of the enhanced glucose-stimulated insulin secretion that followed PTX treatment (52–54). One explanation for this activating effect is tonic inhibition by an endogenous islet inhibitor such as ghrelin that acts via Gαi2 (16) and has its inhibitory effect blocked by PTX. However, another explanation has emerged recently from studies on mice lacking Gαo2 (127). It was found that these mice, but not mice that were lacking other G proteins such as Gαo1 or Gαi proteins, had increased insulin output in response to glucose stimulation. Whether this is tonic inhibition by another endogenous islet hormone activating Gαo2 (another because ghrelin selectively activates Gαi2) or is due solely to a constitutive inhibitory effect of Gαo2 remains to be determined.

Recently, two novel effects of norepinephrine have been uncovered. These are 1) retardation of the refilling of the readily releasable granule pool (RRP), which obviously reinforces the distal inhibitory effect (135); and 2) inhibition of endocytosis (136). Of interest is the fact that while all the previously known effects of norepinephrine, and the recently discovered effect on the RRP, are due to activation of the PTX-sensitive Gi/Go proteins, the inhibition of endocytosis is due to the activation of Gz, the only member of the Gi/Go family of G proteins to be unaffected by PTX. This article reviews the effects of norepinephrine on K+ channels, adenylyl cyclases, exocytosis, the RRP, and endocytosis in the β-cell together with the roles played by individual G proteins.

Norepinephrine Activation of K+ Channels

Activation of the α2A-adrenergic receptor in the β-cell results in hyperpolarization and increased K+ efflux. This is due to activation of K+ channels (90) and primarily to the ATP-sensitive K+ (KATP) channel. However, it has also been shown that mouse β-cell electrical activity is suppressed by activation of a sulfonylurea-insensitive low-conductance K+ channel distinct from the KATP channel but again by a G protein-dependent mechanism (98). Strong evidence for a role for ion channels other than KATP channels comes from studies with sulfonylurea receptor-1 (SUR-1) knockout mice with nonfunctional KATP channels (119). β-Cells from these mice are hyperpolarized by activation of α2-adrenergic receptors by epinephrine, again with PTX sensitivity (107). The expression and precise catecholamine control of ion channels in β-cells of these knockout mice remains to be defined (120). An additional channel that may be involved, but has not yet been shown as a target for norepinephrine, is a voltage-gated K+ (Kv) channel that is activated by ghrelin via Gαi2 (17). Considering these effects of catecholamines on the β-cell membrane potential, it is clear that they hyperpolarize the cell in a PTX-sensitive manner, but the extent to which the individual K+ channels are involved may vary in importance depending on the species and the conditions. The effect of the hyperpolarization of course is to eliminate or reduce the activation of voltage-dependent Ca2+ channels, Ca2+ entry into the cell, and stimulation of insulin secretion. That the effects of hyperpolarization are complicated was shown in a study of β-cells that exhibited oscillations of [Ca2+]i in response to glucose stimulation and β-cells that did not (101). Norepinephrine had different effects on these cells. In nonoscillators, norepinephrine caused a simple decrease in [Ca2+]i. In oscillators, norepinephrine decreased the amplitude and frequency of the oscillations. Furthermore, the onset of the effect of norepinephrine was immediate in nonoscillators but not always so in oscillators. It was shown that these different effects of norepinephrine were not due to any effect on Ca2+ channels but solely on K+ channels.

Subsequent to the finding that PTX-sensitive G proteins were involved in the control of channel activity, investigators sought to determine which G proteins and corresponding subunits were involved. The first approach was by Ribalet and Eddlestone (95), who showed that α-subunits of Gi/Go proteins activated KATP channels in HIT-T15 and RINm5F β-cell lines. While their experiments indicated that the Gi/Go proteins were likely acting directly on the channels, an indirect action could not be ruled out. For instance, a membrane-delimited sequence of reactions downstream of the G proteins could be involved. That neither changes in ATP or cyclic AMP are involved can be seen from patch-clamp experiments performed under whole cell conditions when ATP and cyclic AMP concentrations were maintained constant in the pipette solution. Under these conditions, norepinephrine still activated the KATP channels in 832/13 cells (137). While other signaling moieties could be involved, the effect of norepinephrine is membrane-delimited because with the outside-out membrane patch configuration in the presence of ATPi the open activity of the KATP channels (NPo) was doubled without any change in conductance (95, 137). Other approaches to determine the identity of the G proteins mediating the effects of inhibitors of insulin secretion on the KATP channel include the use of antibodies and blocking peptides directed against the G protein subunits (137). In the case of antibodies diffused into the cell via the pipette under whole cell conditions, a common anti-Gβ had no effect, while a common anti-Gα (against Gi,o,t,z,gust) effectively inhibited the effects of norepinephrine on membrane potential and the KATP channel (137). Following up on this, specific antibodies against various individual G protein α subunits were used. The results were intriguing because a combination of Gi and Go proteins appears to be required for the full effect of norepinephrine on the channel. Applying antibodies to either Gi or Go alone gave only partial inhibition of the norepinephrine action. According to these data, activation of KATP channels by norepinephrine requires Gαi1 and/or Gαi2 and Gαo2 proteins (137). This surprising conclusion was confirmed by studies with blocking peptides mimicking the COOH termini of the α-subunits. Applying either one of the corresponding Gαi1/2/Gαo2 blocking peptides only partially inhibited the action of norepinephrine while the application of both was fully effective. Blocking peptides for Gαi3 and Gαo1 had no effect on the action of norepinephrine. Thus activation of KATP channels by norepinephrine requires Gαi1 and/or Gαi2 and Gαo2 (137). The lack of definition at present regarding Gαi1 and Gαi2 is due to the fact that the antibodies and peptides that block the G protein receptor interactions are directed against the COOH termini of the α-subunits of the G proteins where Gαi1 and Gαi2 have the same amino acid sequence. Major questions to be answered now are why both Gi and Go are required and where they bind to produce their effects.

Inhibition of Adenylyl Cyclases

While there has been little research published over the past few years on the effects of norepinephrine on the activity of adenylyl cyclases in the β-cell, for completeness a brief account of the effects of norepinephrine and other inhibitors on the enzymes in the β-cell is presented here. Since the paper by Samols et al. (100) in 1965 showing that glucagon has a potentiating effect on glucose-stimulated insulin secretion, it has been clear that adenylyl cyclases and cyclic AMP are playing major roles in insulin secretion, β-cell function, and metabolic homeostasis. This observation has been succeeded by many reports on the potentiating effects of cyclic AMP via peptides such as glucagon-like peptide 1 (GLP-1), glucose-dependent insulinotropic peptide (GIP) originally known as gastric inhibitory polypeptide, vasoactive intestinal peptide (VIP), pituitary adenylate cyclase activating peptide (PACAP), and others. The effects of these peptides to potentiate stimulated insulin secretion is blocked or reduced by the effect of norepinephrine to inhibit adenylyl cyclases. The importance of these peptides is emphasized by the fact that knowledge of the effects of GLP-1 has been transformed into therapy for type 2 diabetes by the development of long-acting GLP-1 analogs and slow-release formulations, and by inhibitors of dipeptidyl peptidase 4 (DPP-4), the enzyme that rapidly breaks down GLP-1 in the body (2, 24).

Cyclic AMP in the β-cell is elevated by numerous agonists, as just described, and also by glucose (23). Its effects are to potentiate insulin secretion and to stimulate and modify gene expression controlling multiple functions. Prominent among these are insulin biosynthesis, replication, and apoptosis (23). Mediators of these effects are protein kinase A (PKA), the exchange proteins activated by cyclic AMP (Epac), and cyclic AMP response elements and other proteins in the nucleus. Consequently, norepinephrine and other inhibitors of adenylyl cyclases that decrease cyclic AMP levels also have multiple effects on β-cell function. Of the nine known isoforms of the trans-membrane adenylyl cyclases (AC I–AC IX), the following have been reported present in β-cells: AC I and VIII (93); AC V and VI (66); AC I, VI, and VIII (14); and ACs I–IV, VI, and VIII (32). There is also a soluble adenylyl cyclase (sAC) (11). The latter is distinct in that it is not controlled by heterotrimeric G proteins but by intracellular bicarbonate, calcium, and ATP (11). The Ca2+-activated adenylyl cyclases, ACs I, III, and VIII, are likely responsible for the elevation of cyclic AMP by glucose. It is not known which isoforms of adenylyl cyclase in the β-cell are inhibited by norepinephrine. However, as is the case for all the effects of norepinephrine to inhibit insulin secretion, the inhibition is mediated by the PTX-sensitive heterotrimeric Gi/Go proteins (61). While information on the individual isoforms of Gi/Go proteins that mediate the inhibition of the ACs is incomplete, it is known that Gαi2 and Gαi3 proteins mediate the inhibition of AC by galanin in the RINm5F cell (75). Future studies should focus on which individual Gi/Go protein isoforms inhibit which individual isoforms of the adenylyl cyclase family. More speculative would be to determine whether norepinephrine interferes in any way with the formation of multiprotein scaffolding proteins such as the A kinase anchoring proteins that play roles both upstream and downstream of cyclic AMP elevation (13, 15, 47, 88).

The Mechanism of Action of Norepinephrine on Exocytosis per se (the so-called Distal Site)

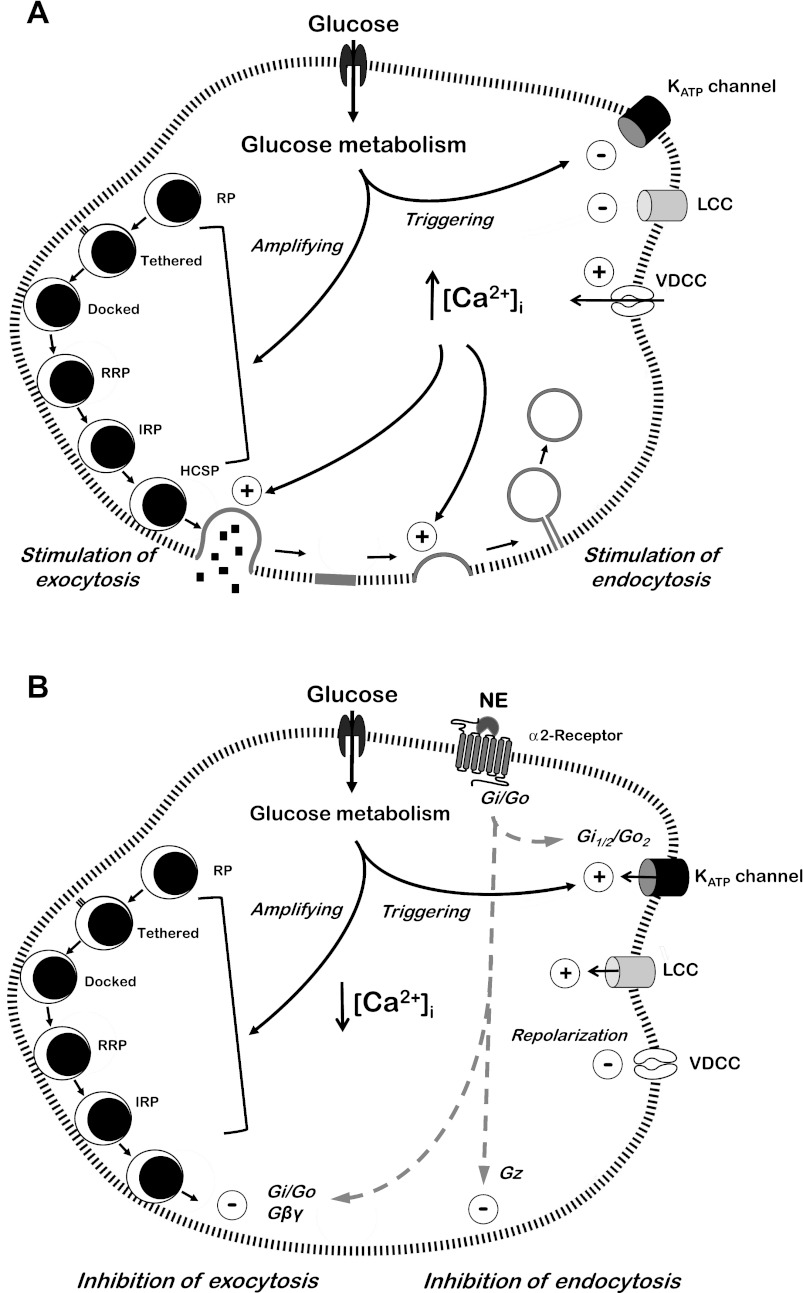

An indication that physiological inhibition of insulin secretion could be effected at a distal site was seen as early as 1977 (129) and with further evidence provided later (1, 46, 76, 105, 124). However, more than three decades would go by before the mechanism was understood and the G protein βγ subunit identified as the mediator of the inhibition by an effect to block the interaction of the Ca2+-sensor synaptotagmin with the proteins involved in exocytosis (7). In the β-cell, these proteins, the SNARE proteins, include the t-SNARES synaptosomal-associated proteins of 23 kDa (SNAP-23) and 25 kDa (SNAP-25), syntaxin isoforms at the plasma membrane, and the v-SNAREs synaptobrevin-2 (also known as vesicle-associated membrane protein-2 or VAMP-2) and cellubrevin (VAMP-3) at the granule membrane. Ca2+-stimulated exocytosis also involves the Ca2+-sensor synaptotagmin present in the granule membrane, Munc-18, and several other proteins. For reviews on this topic see references 45 and 116. A minimal description of the mechanism of exocytosis in response to glucose in the β-cell would include a rise in [Ca2+]i and Ca2+ binding to the synaptotagmins VII and IX (25). Subsequent synaptotagmin binding to SNARE complexes, comprising SNAP-23 and SNAP-25, syntaxin 1A and syntaxin 4, and VAMP-2, with the involvement of Munc-18c and other proteins initiates granule membrane/plasma membrane fusion, exocytosis, and the release of insulin. Understanding of the mechanism of the distal inhibitory effect in the β-cell came from studies on neuronal cells on the inhibition of neurotransmitter release downstream of elevated [Ca2+]i by serotonin. It was shown that the inhibitory G protein βγ subunit bound to the SNARE complex at the COOH terminus of SNAP-25. This competitively blocks the interaction between synaptotagmin and SNAP-25 and inhibits exocytosis (7, 8, 27). Furthermore, a high Ca2+ concentration enabled the Ca2-activated synaptotagmin to compete successfully with Gβγ for SNARE protein binding and overcome the inhibitory effect. Similar studies to these confirmed that this mechanism was operating in the β-cell (135). Thus, antibodies against Gβ blocked the inhibition of exocytosis by norepinephrine. The βγ-activating peptide mSIRK (31) inhibited exocytosis, and when norepinephrine and mSIRK were applied together there was no additional inhibition relative to the two applied singly. The inhibitory effects of both norepinephrine and mSIRK were overcome by a high Ca2+ concentration. Additionally, botulinum toxin A, which cleaves off a portion of the COOH terminus of SNAP-25, blocked the inhibition of exocytosis by norepinephrine. A COOH-terminal blocking peptide of SNAP-25 also prevented the inhibitory effect. Thus, the distal inhibition of exocytosis by norepinephrine in the β-cell is due to Gβγ binding to the SNARE complex, inhibition of synaptotagmin binding, and blockade of SNARE protein function (135). Additionally, it was found that the distal inhibition by norepinephrine is due to a decrease in the number of exocytotic events with no change in vesicle size or fusion pore properties (135). This confirms that the inhibition occurs at a site common to the mechanisms that trigger exocytosis following an increase in [Ca2+]i. These features of glucose stimulation and norepinephrine inhibition are shown in Fig. 1.

Fig. 1.

A: stimulation of insulin secretion by glucose. The metabolism of glucose stimulates insulin release by closure of ATP-sensitive K+ (KATP) channels and a low-conductance K+ channel (LCC), depolarization of the cell, and elevation of intracellular Ca2+. This is referred to as activation of the triggering pathway. The amplifying pathway is increasingly activated by glucose metabolism over time by the buildup of an as yet unknown signal or signals from the mitochondria, in conjunction with the still elevated intracellular Ca2+ concentration ([Ca2+]i). This pathway increases the flow of granules from the reserve pool (RP) to the immediately releasable state where, in an activated cell, they undergo exocytosis. The two pathways are considered responsible for the first and second phases of glucose-stimulated insulin secretion, respectively. The elevated [Ca2+]i also initiates the necessary compensatory endocytosis. RRP, readily releasable pool; IRP, immediately releasable pool; HCSP, highly Ca2+-sensitive pool; VDCC, voltage-dependent calcium channel. B: norepinephrine (NE)-induced inhibition of glucose-stimulated insulin secretion and endocytosis. NE inhibits insulin release in two ways, both of which involve the pertussis-sensitive heterotrimeric Gi and Go proteins. In one, NE opens the KATP channels to hyperpolarize the cell, and in this mechanism, Gi1/2 and Go2 are required for the full effect on the channels. In the other, NE inhibits release by the effect of Gβγ (derived from Gi and/or Go) to directly inhibit the SNARE protein involvement in exocytosis. NE inhibits endocytosis via activation of Gz (see text).

Norepinephrine Has Two New Tricks and a New G Protein Partner

Norepinephrine retards the refilling of the readily releasable pool of insulin containing granules.

Secretory cell granule pools such as the large reserve pool (RP), the readily releasable pool (RRP) (6, 26, 40, 80, 114, 115), the immediately releasable pool (IRP) (6, 26, 80, 115), and the highly Ca2+-sensitive pool (HCSP) (40), have to be carefully defined. The reason being that their names stem from studies in various cell types with different patterns of exocytosis and different control mechanisms, because of different circumstances in the same cell type, e.g., primed or not primed in the β-cell, and because of the different experimental protocols under which they have been studied. The need for careful definition is further emphasized by the fact that different researchers have used the terms IRP and RRP to describe the same pool. We (114, 115) and others (6, 26, 77) have described both an IRP and an RRP in the β-cell similar to the terminology for other cell types (29, 125) and as originally proposed in chromaffin cells (39). In this terminology, the IRP is immediately released when the cell is stimulated. Subsequently, if the stimulation is prolonged, the IRP has to be refilled from the RRP, and the RRP from the RP in order for the flow of exocytosis to continue. The IRP is equated with the first phase of glucose-stimulated insulin release, and the size of the first phase response will be an indication of the number of granules in the IRP. Of interest here is the time course of the IRP release and its relationship to the first phase of glucose-stimulated insulin release. Under conditions where exocytosis from a single cell is measured by capacitance change during depolarization, the IRP is released in milliseconds (135, 136). In the case of glucose stimulation of perfused isolated islets or perfused pancreas, the release occurs over a first phase period of ∼8 min (82, 113–115). Why then is the IRP measured on single cells equated with the first phase of insulin release? The strongest evidence is that the number of granules released per cell is similar (6, 115), and the most likely explanation for the different time course is that the depolarized single cell is activated in milliseconds and the exocytosis recorded by capacitance change in milliseconds. Cells in the intact islet are activated at different times over the 8-min period because glucose has to diffuse into the tissue and be metabolized before stimulating the cell, and then the insulin has to diffuse out before it can be measured. The rate of conversion of granules from the RRP to the IRP will determine the rate of the second phase response (115). For the purpose of this review the term RRP is also defined operationally as the pool or combination of pools from which granules are rapidly released in response to an extremely large Ca2+ stimulus under patch-clamp conditions. Furthermore, this stimulus depletes the pool so that a subsequent stimulation shortly after the first induces only a minimal response. This operational definition is used because the studies that defined the effect of norepinephrine to retard the refilling process used a large Ca2+ stimulus that depleted the pool and also prevented any inhibitory effects of norepinephrine on exocytosis. This definition of the RRP most likely encompasses all three releasable pools described thus far in the β-cell literature, the RRP, IRP, and HCSP. The effect of norepinephrine to inhibit the refilling of the RRP was discovered during capacitance studies to determine which G proteins were involved in the distal inhibition of exocytosis (135). Under whole cell conditions, an antibody against Gβ largely eliminated the inhibitory effect of norepinephrine on exocytosis when a single depolarizing pulse was applied to the cell, while an antibody common to several Gα subunits (Gi,o,t,z,gust) was without effect. This was consistent with the concept that it is the βγ subunit that mediates the distal inhibitory effect. However, when the experiments were performed with a series of consecutive stimulations, the antibody against Gβ was fully effective against the first stimulation but appeared to become less effective over time (135). A possible explanation for this is that norepinephrine, in addition to blocking exocytosis, had an effect to reduce the rate of refilling of the RRP. Thus the antibody against βγ was indeed completely blocking the exocytosis that was occurring over time, but the number of granules available for exocytosis was progressively less relative to the control cells. This was confirmed by using a two-pulse protocol to measure refilling rates directly. A depolarizing pulse providing a high Ca2+-influx over 500 ms was applied to deplete the RRP and to block the effect of norepinephrine on exocytosis. Subsequent second pulses of the same magnitude were then applied after time intervals of 1 to 40 s. The size of the exocytotic responses to the second pulse at each time point estimates the rate at which the RRP is being refilled after depletion. Under the conditions imposed, control cells were 40% refilled 2 s after the first stimulation and 80% after 30 s. In contrast, cells exposed to norepinephrine were only 10% refilled after 2 s and <40% after 30 s. Subsequently, Gαi1 and/or Gαi2 were found to be the mediators of the effect (135) (Fig. 2).

Fig. 2.

Effect of NE to retard the refilling of the RRP and reduce the number of docked granules. NE slows the refilling of the RRP via Gαi1/2. The site of action is unknown and could be at any point or multiple points between the RP and the RRP. Overexpression of the α2-adrenergic receptor decreases the number of docked granules (98) as does Go (137).

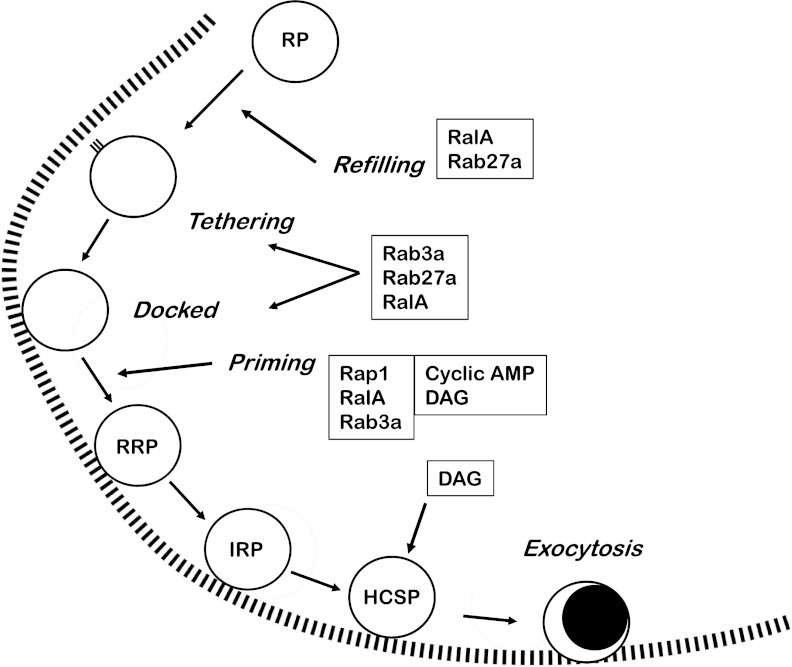

In seeking the mechanism by which norepinephrine slows the refilling process, all the steps involved must be considered. Thus translocation of granules from the RP to the plasma membrane, tethering, docking with the membrane, and priming for release (either biochemical, locational or both) all have the potential to be rate limiting. Note that these steps apply to both the conventional ideas of granule docking and being prepared for release at docked sites on the membrane to the more recent idea of “newcomers” moving rapidly from the RP to exocytosis (84, 85). From capacitance studies it was concluded that the rate of refilling of the RRP is dependent on the metabolism of glucose in the absence of any changes in Ca2+ influx (22, 94). A change in cellular ATP levels was identified as one possible reason for this, but other signals derived from glucose metabolism are not ruled out. Activation of protein kinase C (PKC) also increases the size of a highly Ca2+-sensitive vesicle pool (134). Treatment of cells with phorbol esters, which activate both PKC and diacylglycerol (DAG)-binding proteins, increases both the size and refilling rate of RRPs (29, 64, 109, 112, 126, 130) and potentiates insulin secretion by increasing the total number of vesicles that are available for release. The DAG-binding protein Munc-13 (10) has a role in priming vesicles and increasing RRP pool size (64). Consequently, it is likely that the effects of phorbol esters are mainly due to activation of Munc-13. Direct interactions of PKA and PKC with the secretory machinery have also been suggested in other cell types, such as chromaffin cells and hippocampal neurons, where the size of the RRP and its rate of replenishment is increased (109, 112). While inhibition of DAG-binding proteins and PKC could be involved in the retarding effect of norepinephrine, there is no evidence in the β-cell literature for an inhibitory effect of norepinephrine on DAG-binding proteins or PKC. PKA-dependent and Epac-dependent effects of cyclic AMP on RRP refilling and size are known and have been extensively reviewed (36, 37, 48, 51, 103). Epac signals through the low-molecular-weight G protein Rap1 (106). Despite these data, the well-characterized effect of norepinephrine to inhibit adenylyl cyclases and lower cyclic AMP levels is not responsible for the retarded refilling of the RRP because the patch-clamp experiments in which the effect was demonstrated were buffered with a maximally effective concentration of cyclic AMP in the intracellular (pipette) solution (135). Nevertheless, low-molecular-weight G proteins have been implicated in the control of granule translocation, tethering, docking, and the size and refilling of the rapidly releasable pool. They will be mentioned here only briefly for two reasons: 1) their roles in the control of insulin secretion have been comprehensively reviewed recently (62, 128) and 2) as yet there is no apparent mechanism to connect them to an effect of norepinephrine via Gαi1/2 to retard the refilling of the pool. Despite this, given that heterotrimeric G proteins do signal to low-molecular-weight G proteins (70, 123), a connection may be found in the future. It should be noted that some of the implications that the low-molecular-weight G proteins affect one or other of the various steps between translocation and exocytosis are derived from indirect evidence. An effect of a low-molecular-weight G protein on the first phase of glucose-stimulated insulin release or on a response to a depolarizing concentration of KCl has been interpreted as an effect on the size of the RRP even though the pool size may not have been measured directly. An effect on the second phase of release has been interpreted as an effect on the rate of refilling of the RRP because the RRP has to be refilled from the RP in order for the flow to the IRP and exocytosis to continue. This includes several factors, including the rates of granule translocation, tethering, docking, and priming. Only when these events are measured individually will there be any certainty as to the precise targets and actions of the low-molecular-weight G proteins. With that proviso, there are reports that low-molecular-weight G proteins affect all these necessary aspects of secretion. Examples include RalA (67, 68), Rab3a (77), and Rab27a (30, 49, 50, 77, 132), all three of which are associated with tethering and docking. Priming and pool size are reportedly controlled by Rap1 (106), RalA (68), and Rab3a (77, 131); exocytosis by Rab3a (77) and Rab11 (117); and the refilling of the pool after exocytosis by Rab27a (30, 49) and RalA (68). The effect of the α2-adrenergic receptor (99) and the effect of Gαo (138) on the number of docked granules is discussed later in this review (Fig. 3).

Fig. 3.

Low-molecular-weight G proteins and second messengers that are involved in the control of granule movement, number, and preparedness for exocytosis. Important players shown here are RalA, Rab3a, Rab27a, Rap1, cyclic AMP [via PKA and exchange proteins activated by cyclic AMP (Epac)], and diacylglycerol (DAG) (via PKC and DAG-binding proteins). All are involved in controlling the number of granules in the RRP. Their actions and references to them are given in the main text.

The IRP in the β-cell that is released by glucose stimulation during the first phase of insulin secretion (114, 115) is a subset of the RRP and is of great importance for at least three reasons: 1) a diminished first phase response is a feature of type 2 diabetes and occurs even before the onset of overt symptoms of the disease (19, 28, 60); 2) in glucose-induced biphasic insulin secretion, the size of the IRP determines the size of the first phase; and 3) the rate of refilling of the IRP after the first phase of release is an effector of the glucose-amplifying pathway and determines the rate and magnitude of the second phase response (80, 114, 115). It does this by time-dependently accelerating a rate-limiting step in the refilling of the IRP to induce the rise to the second phase plateau—at which point the conversion rate of granules from the RRP to the IRP is maximal and equal to the rate of exocytosis (114, 115). Physiologically, it is of interest now that norepinephrine inhibits both of the major pathways by which glucose induces biphasic insulin secretion. The first phase of glucose-stimulated release is due to the KATP channel-dependent or “triggering” pathway that involves closure of the KATP channels, depolarization of the β-cell, increased Ca2+ influx, and increased [Ca2+]i. This is blocked by the effect of norepinephrine to activate the KATP channels and thereby hyperpolarize the cell (104). The second phase of release is due to the K+ channel-independent or “amplifying” pathway and is caused, as just described, by an increased rate of refilling of the IRP (114, 115). This refilling is restrained by norepinephrine. The mechanism of action of Gαi1/2 to slow the refilling of the RRP remains to be worked out but is also important as a future potential therapeutic target, e.g., for the reduction of insulin release in the various forms of hyperinsulinism (20).

Norepinephrine inhibits endocytosis via activation of Gz.

Recently, it was found that norepinephrine exerted an inhibitory effect on endocytosis (136). This finding was novel but could have been anticipated as both exocytosis and endocytosis are stimulated by increased [Ca2+]i. Therefore, as norepinephrine can inhibit exocytosis, even in the face of increased [Ca2+]i, endocytosis would not be needed and must be prevented. An example of such a situation would be stimulation of insulin release by arginine after a high-protein meal. Norepinephrine would inhibit exocytosis but would not inhibit the arginine-induced increase in [Ca2+]i. In this way, the two events, inhibition of exocytosis and inhibition of endocytosis, are coordinated. Also completely novel was the finding that the PTX-insensitive heterotrimeric G protein Gz mediates the effect. While Gz has not previously been linked to norepinephrine, it is present in the β-cell and is activated by PGE1 (57, 58). The probable reason why this effect of norepinephrine has been hidden for so long is that as norepinephrine inhibits exocytosis, there was little need to look for an effect on endocytosis. Only when the effect of norepinephrine to inhibit exocytosis was blocked by high Ca2+ influx was the effect on endocytosis apparent (135, 136). Evidence that normal control of endocytosis is important for the β-cell is as follows. 1) Cyclosporine and tacrolimus, powerful inhibitors of calcineurin and consequently endocytosis, are used extensively after organ transplantation and are associated with posttransplant diabetes mellitus. Furthermore, while insulin resistance plays a role in the development of posttransplant diabetes mellitus, reduced insulin secretion appears to have the major role (34). 2) Tacrolimus inhibits insulin gene expression, insulin mRNA levels, and insulin secretion (92). 3) The dominant interfering dynamin mutant DynK44A or siRNA knockdown of dynamin inhibit insulin release (79). While the mechanism(s) involved in the development of posttransplant diabetes mellitus are not known in detail, and are likely multifaceted, the inhibition of endocytosis by cyclosporine and tacrolimus and the resultant deleterious effects on insulin secretion should certainly be subject to serious investigation. Endocytosis, first documented in the β-cell by Orci et al. in 1973 (87), has received considerable interest in the past decade (35, 42, 59, 63, 71, 72, 81, 86, 122). The term applies to several mechanisms that exist to remove cell membrane components. Among these are receptor internalization, phagocytic processes, retrieval of plasma membrane constituents for renewal and, of direct relevance to the β-cell, the endocytosis of vesicles, vesicle proteins, lipids, and other constituents after exocytosis, i.e., compensatory endocytosis. In general, there are five possible ways in which granules can undergo endocytosis (96): 1) “kiss and run” retrieval; 2) the collapse of a granule and its retrieval by clathrin-mediated endocytosis; 3) bulk retrieval of membrane components; 4) the collapse of a granule followed by dispersal into patches of membrane that are subsequently retrieved; and 5) the collapse of a granule followed by complete dispersal of the granule membrane and retrieval of the individual components (96). Obviously, distinct mechanisms will be involved to facilitate these disparate processes. Therefore, important to understanding the endocytosis that follows exocytosis in the β-cell are the types of exocytosis taking place. Whether exocytosis occurs by full fusion of the granules or partial fusion (kiss and run) is critical, because the former requires retrieval of granule membrane components from the plasma membrane and the latter requires retrieval of the essentially intact granule membrane. The extent to which the two processes occur is a matter of debate (71, 73), but the evidence in favor of the simultaneous operation of both mechanisms in the β-cell is strong. Endocytosis is stimulated by increased [Ca2+]i in β-cells (21, 91) as in other cells and occurs in two phases, similar to the two phases of endocytosis in chromaffin cells (110). Increased [Ca2+]i sets in motion a series of reactions beginning with the activation of calcineurin, dephosphorylation of the dephosphins, and the subsequent involvement of dynamin (12, 69, 108) and other players. Calcineurin inhibitors such as deltamethrin, tacrolimus, and cyclosporin A block the initiating step in the sequence of events that lead to Ca2+-induced endocytosis. As a result, they block endocytosis by reducing the number of events without any effects on later steps such as vesicle size, fission kinetics, or other aspects of the mechanisms involved. Norepinephrine also inhibits endocytosis by reducing the frequency of endocytotic events and without changing the size of the vesicles. However, unlike the calcineurin inhibitors, it does affect the kinetics and Gz is assumed to act at a late stage of endocytosis (136). This action of norepinephrine to inhibit endocytosis is novel, as is its activation of Gz. However, it is likely that this effect will be found in many other cells in which agonists inhibit exocytosis downstream of elevated [Ca2+]i. Two such agonists are serotonin (7, 8, 27) and endothelin (3).

The Roles of Go in the Control of Insulin Release

Regulation of the number of docked granules.

Of related interest to the effect of norepinephrine to slow the rate of refilling of the RRP are two recent findings. The first is that humans, with a single-nucleotide polymorphism in the α2A-adrenergic receptor gene who exhibit overexpression of α2A-adrenergic receptors with reduced insulin secretion and increased risk of type 2 diabetes, had a decrease in the number of docked β-cell granules (99). This study is discussed in more detail in the Clinical Implications section of this review, which deals with the potential clinical implications of the α2-adrenergic receptors. The second finding is that Gαo has a controlling influence on the number of docked granules in the β-cell (138). In this study, the authors used a tissue-specific β-cell knockout of Gαo in the mouse and studied granule docking with transmission electron microscopy (TEM), with quantitative morphometry, and with total internal reflection fluorescence microscopy (TIRFM). They found that the number of docked granules in the β-cell was significantly increased relative to wild-type controls, indicating that Gαo maintains a suppressive effect on the number of docked granules. With TEM, the number of docked granules, defined as those in contact with the plasma membrane, was twice that of the wild type. Using TIRFM, the number of docked granules was increased by one third. TEM and TIRFM detect docked granules differently, but regardless of this both techniques detected a significant increase in the number of docked granules in the β-cells of the Gαo−/− mutant mice. In further studies, no differences were detected in granule trafficking or in the numbers of “newcomer granules” in the absence of Gαo in the β-cell. It is clear from this study and others that control over the refilling rate and the number of granules in the RRP is a complex of several overlapping functions.

The mechanism underlying the name “islet activating protein.”

PTX increases plasma insulin levels and enhances stimulated insulin secretion. It was because of these findings that it was first named islet-activating protein (53, 121). The reasons for these tonic and enhancing effects have remained unknown until recently, but now two explanations have been put forward. In the first, it is proposed that ghrelin, an endogenous ligand for the growth hormone secretagogue receptor (41), is responsible. While ghrelin is produced mainly in the stomach (5), it is present in the islet (17). There are several lines of evidence in favor of the idea that ghrelin is responsible for the islet-activating effect of PTX. Ghrelin inhibits insulin secretion in vivo and in vitro (18). There is an inverse relationship between fasting insulin levels and ghrelin concentrations in blood (17, 18). In addition, antiserum against ghrelin increases insulin release and lastly, PTX blocks the effects of ghrelin (18). Antisense oligonucleotides against Gαi2, but not those against Gαi1 or Gαi3, block the effect of ghrelin to inhibit glucose-stimulated insulin release and identify Gαi2 as the G protein mediator of the effects of ghrelin. Ghrelin gene knockout blocked the insulin release-enhancing effect of PTX by 70–80%, indicating that much of the islet-activating effect of PTX was due to ghrelin (17, 18). In the second, more recent explanation, it is reported that Gαo2 is responsible for the tonic inhibition that is lifted by PTX. Mice lacking Gαo2 but not those lacking Gαo1 or any of the Gi subunits handle glucose loads more efficiently than wild-type mice and do so by increased insulin release (127). In this study, the authors generated Gαo1 and Gαo2 knockout mice. In glucose tolerance tests using these mice and the wild-type controls, the responses of wild-type and Gαo1−/− mice were similar. However, the response of the Gαo2−/− mice was much different, with a lower peak glucose level and more rapid decline to baseline values. As normalized insulin tolerance tests were similar in wild-type and the Gαo2−/− mice, it was concluded that the difference in the glucose tolerance tests was likely due to differences in insulin secretion, with the Gαo2−/− mice secreting more insulin in response to glucose. This was confirmed by experiments on isolated islets from these mice. It was further shown that somatostatin failed to inhibit insulin secretion in the Gαo2−/− mice. Norepinephrine was not tested. It remains to be seen how these two convincing explanations for islet activation by PTX can be reconciled. In one, the activation is due to Gαi2 in response to endogenous ghrelin, and in the other, Gαo2 is acting either constitutively or in response to hormones that inhibit insulin secretion via Gαo2. While both mechanisms are likely to be involved, further studies will be required to resolve the issue.

Clinical Implications

α2-Adrenergic receptor involvement in diabetes.

Research into the various causes of type 2 diabetes has usually focused on the combination of insufficient insulin secretion to control blood glucose levels and insulin resistance. Most of the emphasis on the β-cell has been on the mechanisms of stimulation of insulin secretion and how they might be impaired or inadequate. There has been less interest in the physiological inhibitory mechanisms of insulin secretion despite the knowledge that excessive inhibition of insulin secretion could well be a cause of diabetes. An early indication of this was the finding that clonal β-cells overexpressing the α2-adrenergic receptor exhibited tonic inhibition of insulin secretion. The authors suggested that “abnormalities in expression or function of such receptors could be a contributory factor in the impaired insulin secretion present in type 2 diabetes” (97). Studies on α2A-adrenergic receptor knockout C57BL/6J mice provided further evidence of receptor-induced tonic inhibition. When these knockout mice were compared with their wild-type controls, they showed lower blood glucose levels and higher plasma insulin levels. Their glucose tolerance was also significantly better than the wild type (111). In an early study on polymorphism of the α2A-adrenergic receptor, genomic DNA was isolated from 147 hypertensive patients. Genotypes at the α2A-adrenergic receptor were identified and studied in relation to hypertension, and lipid and glucose metabolism (78). While no association of α2A-adrenergic receptor polymorphism with hypertension was found, there was a significant reduction in the amounts of hemoglobin A1, hemoglobin A1c, and total cholesterol in blood from patients with the D allele of the receptor. Similar trends were seen for glucose, triglycerides, and low-density lipoprotein cholesterol, but they failed to achieve statistical significance. The data from this polymorphism study did not suggest that it confers an increased risk of diabetes. Nevertheless, these and other genetic studies (9) stress the importance of reevaluating the α2A-adrenergic receptor in the causation of some forms of diabetes. This is especially important since, more recently, overexpression of α2A-adrenergic receptors was shown to contribute to type 2 diabetes (99). In the Goto-Kakizaki (GK) rat, with its diabetes susceptibility locus that includes the α2A-adrenergic receptor gene, there was a decrease in the number of docked granules, as estimated by quantitative morphometric analysis, associated with reduced insulin secretion. Blockade of the α2A-adrenergic receptor by yohimbine reversed the defects so that normal function was restored. This identified the defect at the level of the α2A-adrenergic receptor. When variants of the human α2A-adrenergic receptor gene were studied, polymorphisms around the α2A-adrenergic receptor were connected to decreased insulin secretion and increased risk of type 2 diabetes. In vitro studies with human islets confirmed that islets from humans with the risk-carrying α2A-adrenergic receptor polymorphism had increased numbers of the α2A-adrenergic receptors, lower numbers of docked granules, and reduced insulin secretion in response to glucose stimulation. These were reversed by α2A-adrenergic receptor blockade. It seems likely that the reduced docking and insulin secretion result from the overexpressed α2A-adrenergic receptors.

Summary

The actions of norepinephrine on the pancreatic β-cell include activation of K+ channels, inhibition of adenylyl cyclases, direct inhibition of exocytosis, retardation of the refilling of the RRP, and inhibition of endocytosis. Only the latter effect of norepinephrine, mediated by Gz, is not via the PTX-sensitive Gi and Go proteins. By virtue of its effects on K+ channels and the RRP, norepinephrine inhibits the two major pathways involved in glucose-stimulus secretion coupling (114), the triggering and amplifying pathways, respectively. Its effect to inhibit exocytosis of course blocks both pathways. Augmentation of stimulated insulin secretion by agonists such as GLP-1, GIP, and PACAP is blocked by the effect of norepinephrine to inhibit the activity of adenylyl cyclases. Recently, discovered effects of Go proteins include a suppressive effect of Gαo on the number of docked granules, and a tonic inhibition of insulin release by Gαo2. Overexpression of the α2-adrenergic receptor leads to reduced insulin secretion and a form of type 2 diabetes.

Future Perspectives

Despite decades of work that have uncovered the physiological effects of norepinephrine, much remains to be done. In the clinical area it would seem that polymorphisms of the receptors for all the physiological inhibitors of insulin secretion, for example, somatostatin, ghrelin, and prostaglandins, could be associated with the development of type 2 diabetes. The possible role of inhibited endocytosis in posttransplant diabetes mellitus is also an area for study. The mechanism by which norepinephrine and presumably other inhibitors retard the refilling of the RRP needs to be understood because it should provide useful targets for the treatment of hyperinsulinism. Are increased expression levels of all the Gi and Go proteins associated with a form of type 2 diabetes? In the area of basic research, we need to investigate the mechanisms of norepinephrine action in greater detail to answer several questions. How are the G proteins and the isoforms of their αβγ subunits interacting with the effectors of the inhibition of insulin secretion i.e., K+ channels, adenylyl cyclases, and the SNARE complexes? Does norepinephrine affect SNARE protein function only in exocytosis and endocytosis or does it affect fusion processes in organelles like the endoplasmic reticulum, Golgi, and lysosomes where other subsets of SNARE proteins are active? What protein(s) does Gz interact with to inhibit endocytosis? Both early and recent findings on the effects of norepinephrine and other inhibitors of insulin secretion indicate the need for further detailed investigation.

GRANTS

This work was supported by National Institutes of Health Grant R01 DK-54243.

DISCLOSURES

No conflicts of interest, financial or otherwise, are declared by the author(s).

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

S.G.S. prepared the figures; S.G.S. and G.W.G.S. drafted the manuscript; S.G.S. and G.W.G.S. edited and revised the manuscript; S.G.S. and G.W.G.S. approved the final version of the manuscript.

REFERENCES

- 1.Abel KB, Lehr S, Ullrich S. Adrenaline-, not somatostatin-induced hyperpolarization is accompanied by a sustained inhibition of insulin secretion in INS-1 cells. Activation of sulphonylurea K+ATP channels is not involved. Pflügers Arch 432: 89–96, 1996 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ahrén B. The future of incretin-based therapy: novel avenues-novel targets. Diabetes Obes Metab 13, Suppl 1: 158–166, 2011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Andric SA, Zivadinovic D, Gonzalez-Iglesias AE, Lachowicz A, Tomic M, Stojilkovic SS. Endothelin-induced, long lasting, and Ca2+ influx-independent blockade of intrinsic secretion in pituitary cells by Gz subunits. J Biol Chem 280: 26896–26903, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Angel I, Niddam R, Langer SZ. Involvement of α-2 adrenergic receptor subtypes in hyperglycemia. J Pharmacol Exp Ther 54: 877–882, 1990 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ariyasu H, Takaya K, Tagami T, Ogawa Y, Hosoda K, Akamizu T, Suda M, Koh T, Natsui K, Toyooka S, Shirakami G, Usui T, Shimatsu A, Doi K, Hosoda H, Kojima M, Kangawa K, Nakao K. Stomach is the major source of circulating ghrelin, and feeding state determines plasma ghrelin-like immunoreactivity levels in humans. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 86: 4753–4758, 2001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Barg S, Eliasson L, Renström E, Rorsman P. A subset of 50 secretory granules in close contact with L-type Ca2+ channels accounts for first-phase insulin secretion in mouse β-cells. Diabetes 51, Suppl 1: S74–S82, 2002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Blackmer T, Larsen EC, Takahashi M, Martin TF, Alford S, Hamm HE. G protein βγ subunit-mediated presynaptic inhibition: regulation of exocytotic fusion downstream of Ca2+ entry. Science 292: 293–297, 2001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Blackmer T, Larsen EC, Takahashi M, Martin TF, Alford S, Hamm HE. G protein βγ directly regulates SNARE protein fusion machinery for secretory granule exocytosis. Nat Neurosci 8: 421–425, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Boesgaard TW, Grarup N, Jorgenson T, Borch-Johnsen KMeta-Analysis of Glucose and Insulin-Related Trait Consortium (MAGIC) Hansen T, Pedersen O. Variants at DGKB/TMEM195, ADRA2A, GLIS3 and C2CD4B loci are associated with reduced glucose-stimulated β-cell function in middle-aged Danish people. Diabetologia 53: 1647–1655, 2010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Brose N, Rosenmund C. Move over protein kinase C, you've got company: alternative cellular effectors of diacylglycerol and phorbol esters. J Cell Sci 115: 4399–4411, 2002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Buck J, Levin LR. Physiological sensing of carbon dioxide/bicarbonate/pH via cyclic nucleotide signaling. Sensors (Basel) 11: 2112–2128, 2011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Cousin MA, Robinson PJ. The dephosphins: dephosphorylation by calcineurin triggers synaptic vesicle endocytosis. Trends Neurosci 24: 659–665, 2001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Delint-Ramirez I, Willoughby D, Hammond GV, Ayling LJ, Cooper DM. Palmitoylation targets AKAP79 protein to lipid rafts and promotes its regulation of calcium-sensitive adenylyl cyclase type 8. J Biol Chem 286: 32962–32975, 2011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Delmeire D, Flamez D, Hinke SA, Cali JJ, Pipeleers D, Schuit F. Type VIII adenylyl cyclase in rat β-cells: coincidence signal detector/generator for glucose and GLP-1. Diabetologia 46: 1383–1393, 2003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Dessauer CW. Adenylyl cyclase–A-kinase anchoring protein complexes: the next dimension in cAMP signaling. Mol Pharmacol 76: 935–941, 2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Dezaki K, Hosoda H, Kakei M, Hashiguchi S, Watanabe M, Kangawa K, Yada T. Endogenous ghrelin in pancreatic islets restricts insulin release by attenuating Ca2+ signaling in β-cells: implication in the glycemic control in rodents. Diabetes 53: 3142–3151, 2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Dezaki K, Kakei M, Yada T. Ghrelin uses Gai2 and activates voltage-dependent K+ channels to attenuate glucose-induced Ca2+ signaling and insulin release in islet β-cells: novel signal transduction of ghrelin. Diabetes 56: 2319–2327, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Dezaki K, Sone H, Yada T. Ghrelin is a physiological regulator of insulin release in pancreatic islets and glucose homeostasis. Pharmacol Ther 118: 239–249, 2008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Dornhorst A. Insulinotropic meglitinide analogues. Lancet 358: 1709–1716, 2001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Dunne MJ, Cosgrove KE, Shepherd RM, Aynsley-Green A, Lindley KJ. Hyperinsulinism in infancy: from basic science to clinical disease. Physiol Rev 84: 239–275, 2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Eliasson L, Proks P, Ammälä C, Ashcroft FM, Bokvist K, Renström E, Rorsman P, Smith PA. Endocytosis of secretory granules in mouse pancreatic β-cells evoked by transient elevation of cytosolic calcium. J Physiol 493: 755–767, 1996 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Eliasson L, Renström E, Ding WG, Proks P, Rorsman P. Rapid ATP-dependent priming of secretory granules precedes Ca2+-induced exocytosis in mouse pancreatic β-cells. J Physiol 503: 399–412, 1997 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Furman B, Ong WK, Pyne NJ. Cyclic AMP Signaling in Pancreatic Islets. Adv Exp Med Biol 654: 281–304, 2010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Gallwitz B. Glucagon-like peptide-1 analogues for Type 2 diabetes mellitus: current and emerging agents. Drugs 71: 1675–1688, 2011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Gauthier BR, Wollheim CB. Synaptotagmins bind calcium to release insulin. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab 295: E1279–E1286, 2008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ge Q, Dong YM, Hu ZT, Wu ZX, Xu T. Characteristics of Ca2+-exocytosis coupling in isolated mouse pancreatic β-cells. Acta Pharmacol Sin 27: 933–938, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Gerachshenko T, Blackmer T, Yoon EJ, Bartleson C, Hamm HE, Alford S. Gβγ acts at the C terminus of SNAP-25 to mediate presynaptic inhibition. Nat Neurosci 8: 597–605, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Gerich JE. Is reduced first-phase insulin release the earliest detectable abnormality in individuals destined to develop type 2 diabetes? Diabetes 51: S117–S121, 2002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Gillis KD, Mossner R, Neher E. Protein kinase C enhances exocytosis from chromaffin cells by increasing the size of the readily releasable pool of secretory granules. Neuron 16: 1209–1220, 1996 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Gomi H, Mizutani S, Kasai K, Itohara S, Izumi T. Granuphilin molecularly docks insulin granules to the fusion machinery. J Cell Biol 171: 99–109, 2005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Goubaeva F, Ghosh M, Malik S, Yang J, Hinkle PM, Griendling KK, Neubig RR, Smrcka AV. Stimulation of cellular signaling and G protein subunit dissociation by G protein βγ subunit-binding peptides. J Biol Chem 278: 19634–19641, 2003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Guenifi A, Portela-Gomez GM, Grimelius L, Efendić S, Abdel-Halim SM. Adenylyl cyclase isoform expression in non-diabetic and diabetic Goto-Kakizaki (GK) rat pancreas. Evidence for distinct overexpression of type-8 adenylyl cyclase in diabetic GK rat islets. Histochem Cell Biol 113: 81–89, 2000 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Gulbenkian A, Schobert L, Nixon C, Tabachnick A. Metabolic effects of pertussis sensitization in mice and rats. Endocrinology 83: 885–892, 1968 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Hagen M, Hjelmesaeth J, Jenssen T, Morkrid L, Hartmann A. A 6-year prospective study on new onset diabetes mellitus, insulin release and insulin sensitivity in renal transplant recipients. Nephrol Dial Transplant 18: 2154–2159, 2003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Hanna ST, Pigeau GM, Galvanovskis J, Clark A, Rorsman P, MacDonald PE. Kiss-and-run exocytosis and fusion pores of secretory vesicles in human β-cells. Pflügers Arch 457: 1343–1350, 2009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Holz GG. New insights concerning the glucose-dependent insulin secretagogue action of glucagon-like peptide in pancreatic β-cells. Horm Metab Res 36: 787–794, 2004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Holz GG. Epac: a new cAMP-binding protein in support of glucagon-like peptide-1 receptor-mediated signal transduction in the pancreatic β-cell. Diabetes 53: 5–13, 2004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Homaidan FR, Sharp GWG, Nowak LM. Galanin inhibits a dihydropyridine-sensitive Ca2+ current in the RINm5f cell line. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 88: 8744–8748, 1991 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Horrigan FT, Bookman RJ. Releasable pools and the kinetics of exocytosis in adrenal chromaffin cells. Neuron 13: 1119–1129, 1994 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Hou JC, Min L, Pessin JE. Insulin granule biogenesis, trafficking and exocytosis. Vitam Horm 80: 473–506, 2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Howard AD, Feighner SD, Cully DF, Arena JP, Liberator PA, Rosenblum CL, Hamelin M, Hreniuk DL, Palyha OC, Anderson J, Paress PS, Diaz C, Chou M, Liu KK, McKee KK, Pong SS, Chaung LY, Elbrecht A, Dashkevicz M, Heavens R, Rigby M, Sirinathsinghji DJ, Dean DC, Melillo DG, Patchett AA, Nargund R, Griffin PR, DeMartino JA, Gupta SK, Schaeffer JM, Smith RG, Van der Ploeg LH. A receptor in pituitary and hypothalamus that functions in growth hormone release. Science 273: 974–977, 1996 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Høy M, Efanov AM, Bertorello AM, Zaitsev SV, Olsen HL, Bokvist K, Leibiger B, Leibiger B, Leibiger IB, Zwiller J, Berggren PO, Gromada J. Inositol hexakisphosphate promotes dynamin 1-mediated endocytosis. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 99: 6773–6777, 2002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Hsu WH, Xiang HD, Rajan AS, Boyd AE., 3rd Activation of α2-adrenergic receptors decreases Ca2+ influx to inhibit insulin secretion in a hamster β-cell line: an action mediated by a guanosine triphosphate-binding protein. Endocrinology 128: 958–964, 1991 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Hu X, Friedman D, Hill S, Caprioli R, Nicholson W, Powers AC, Hunter L, Limbird LE. Proteomic exploration of pancreatic islets in mice null for the α2A adrenergic receptor. J Mol Endocrinol 35: 73–88, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Jewell JL, Oh E, Thurmond DC. Exocytosis mechanisms underlying insulin release and glucose uptake: conserved roles for Munc18c and syntaxin 4. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol 298: R517–R531, 2010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Jones PM, Fyles JM, Persaud SJ, Howell SL. Catecholamine inhibition of Ca2+-induced insulin secretion from electrically permeabilised islets of Langerhans. FEBS Lett 219: 139–144, 1987 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Josefsen K, Lee YC, Thams P, Efendic S, Nielsen JH. AKAP 18 alpha and gamma have opposing effects on insulin release in INS-1E cells. FEBS Lett 584: 81–85, 2010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Kang G, Joseph JW, Chepurny OG, Monaco M, Wheeler MB, Bos JL, Schwede F, Genieser HG, Holz GG. Epac-selective cAMP analog 8-pCPT-2′-O-Me-cAMP as a stimulus for Ca2+-induced Ca2+ release and exocytosis in pancreatic β-cells. J Biol Chem 278: 8279–8285, 2003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Kasai K, Fujita T, Gomi H, Izumi T. Docking is not a prerequisite but a temporal restraint for fusion of secretory granules. Traffic 9: 1191–1203, 2008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Kasai K, Ohara-Imaizumi M, Takahashi N, Mizutani S, Zhao S, Kikuta H, Kasai H, Nagamatsu S, Gomi H, Izumi T. Rab27a mediates the tight docking of insulin granules onto the plasma membrane during glucose stimulation. J Clin Invest 115: 388–399, 2005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Kashima Y, Miki T, Shibasaki T, Ozaki N, Miyazaki M, Yano H, Seino S. Critical role of cAMP-GEFII-Rim2 complex in incretin-potentiated insulin secretion. J Biol Chem 276: 46046–46053, 2001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Katada T, Tamura M, Ui M. The A protomer of islet-activating protein, pertussis toxin, as an active peptide catalyzing ADP-ribosylation of a membrane protein. Arch Biochem Biophys 224: 290–298, 1983 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Katada T, Ui M. Effect of in vivo pretreatment of rats with a new protein purified from Bordetella pertussis on in vitro secretion of insulin: role of calcium. Endocrinology 104: 1822–1827, 1979 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Katada T, Ui M. Slow interaction of islet-activating protein with pancreatic islets during primary culture to cause reversal of α-adrenergic inhibition of insulin secretion. J Biol Chem 255: 9580–9588, 1980 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Katada T, Ui M. Direct modification of the membrane adenylate cyclase system by islet-activating protein due to ADP-ribosylation. Proc Nat1 Acad Sci USA 79: 3129–3133, 1982 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Katada T, Ui M. ADP ribosylation of the specific membrane protein of C6 cells by islet-activating protein associated with modification of adenylate cyclase activity. J Biol Chem 257: 7210–7216, 1982 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Kimple ME, Joseph JW, Bailey CL, Fueger PT, Hendry IA, Newgard CB, Casey PJ. Gαz negatively regulates insulin secretion and glucose clearance. J Biol Chem 283: 4560–4567, 2008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Kimple ME, Nixon AB, Kelly P, Bailey CL, Young KH, Fields TA, Casey PJ. A role for Gz in pancreatic islet β-cell biology. J Biol Chem 280: 31708–31713, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Kimura T, Kaneko Y, Yamada S, Ishihara H, Senda T, Iwamatsu A, Niki I. The GDP-dependent Rab27a effector coronin 3 controls endocytosis of secretory membrane in insulin-secreting cell lines. J Cell Sci 121: 3092–3098, 2008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Knowler WC, Narayan KM, Hanson RL, Nelson RG, Bennett PH, Tuomilehto J, Scherstén B, Pettitt DJ. Preventing non-insulin-dependent diabetes. Diabetes 44: 483–488, 1995 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Komatsu M, McDermott AM, Gillison SL, Sharp GWG. Time course of action of pertussis toxin to block the inhibition of stimulated insulin release by norepinephrine. Endocrinology 136: 1857–1863, 1995 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Kowluru A. Small G proteins in islet β-cell function. Endocr Rev 31: 52–78, 2010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Kuliawat R, Kalinina E, Bock J, Fricker L, McGraw TE, Kim SR, Zhong J, Scheller R, Arvan P. Syntaxin-6 SNARE involvement in secretory and endocytic pathways of cultured pancreatic β-cells. Mol Biol Cell 15: 1690–1701, 2004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Kwan EP, Xie L, Sheu L, Nolan CJ, Prentki M, Betz A, Brose N, Gaisano HY. Munc13–1 deficiency reduces insulin secretion and causes abnormal glucose tolerance. Diabetes 55: 1421–1429, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Lang J. Molecular mechanisms and regulation of insulin exocytosis as a paradigm of endocrine secretion. Eur J Biochem 259: 3–17, 1999 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Leech CA, Castonguay MA, Habener JF. Expression of adenylyl cyclase subtypes in pancreatic β-cells. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 2: 703–706, 1999 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Ljubicic S, Bezzi P, Vitale N, Regazzi R. The GTPase RalA regulates different steps of the secretory process in pancreatic β-cells. PLos One 4: e7770, 2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Lopez JA, Kwan EP, Xie L, He Y, James DE, Gaisano HY. The RalA GTPase is a central regulator of insulin exocytosis from pancreatic islet β-cells. J Biol Chem 283: 17939–17945, 2008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Lu J, He Z, Fan J, Xu P, Chen L. Overlapping functions of different dynamin isoforms in clathrin-dependent and -independent endocytosis in pancreatic β-cells. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 371: 315–319, 2008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Luttrell LM, van Biesen T, Hawes BE, Koch WJ, Krueger KM, Touhara K, Lefkowitz RJ. G-protein-coupled receptors and their regulation: activation of the MAP kinase signaling pathway by G-protein-coupled receptors. Adv Second Messenger Phosphoprotein Res 31: 263–277, 1997 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Ma L, Bindokas VP, Kuznetsov A, Rhodes C, Hays L, Edwardson JM, Ueda K, Steiner DF, Philipson LH. Direct imaging shows that insulin granule exocytosis occurs by complete vesicle fusion. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 101: 9266–9271, 2004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.MacDonald PE, Eliasson L, Rorsman P. Calcium increases endocytotic vesicle size and accelerates membrane fission in insulin-secreting INS-1 cells. J Cell Sci 118: 5911–5920, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.MacDonald PE, Rorsman P. The ins and outs of secretion from pancreatic β-cells: control of single-vesicle exo- and endocytosis. Physiology 22: 113–121, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.McDermott AM, Sharp GWG. Inhibition of insulin secretion: a fail-safe system. Cell Signal 5: 229–234, 1993 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.McDermott AM, Sharp GWG. Gi2 and Gi3 proteins mediate the inhibition of adenylyl cyclase by galanin in the RINm5F cell. Diabetes 44: 453–459, 1995 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Mandarino L, Itoh M, Blanchard W, Patton G, Gerich JE. Stimulation of insulin release in the absence of extracellular calcium by isobutylmethylxanthine and its inhibition by somatostatin. J Endocrinol 106: 430–433, 1980 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Merrins MJ, Stuenkel EL. Kinetics of Rab27a-dependent actions on vesicle docking and priming in pancreatic β-cells. J Physiol 586: 5367–5381, 2008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Michel MC, Plogmann C, Philipp T, Brodde OE. Functional correlates of α2A-adrenoceptor gene polymorphism in the HANE study. Nephrol Dial Transplant 14: 2657–2663, 1999 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Min L, Leung YM, Tomas A, Watson RT, Gaisano HY, Halban PA, Pessin JE, Hou JC. Dynamin is functionally coupled to insulin granule exocytosis. J Biol Chem 282: 33530–33536, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Mourad NI, Nenquin M, Henquin JC. Metabolic amplifying pathway increases both phases of insulin secretion independently of β-cell actin microfilaments. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol 299: C389–C398, 2010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Nagamatsu S, Nakamichi Y, Watanabe T, Matsushima S, Yamaguchi S, Ni J, Itagaki E, Ishida H. Localization of cellubrevin-related peptide, endobrevin, in the early endosome in pancreatic β cells and its physiological function in exo-endocytosis of secretory granules. J Cell Sci 114: 219–227, 2001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Nesher R, Cerasi E. Modeling phasic insulin release: immediate and time-dependent effects of glucose. Diabetes 51, Suppl 1: S53–S59, 2002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Niddam R, Angel I, Bidet S, Langer SZ. Pharmacological characterization of alpha-2 adrenergic receptor subtype involved in the release of insulin from isolated rat pancreatic islets. J Pharmacol Exp Ther 254: 883–887, 1990 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Ohara-Imaizumi M, Aoyagi K, Nakamichi Y, Nishiwaki C, Sakurai T, Nagamatsu S. Pattern of rise in subplasma membrane Ca2+ concentration determines type of fusing insulin granules in pancreatic beta cells. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 385: 291–295, 2009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Ohara-Imaizumi M, Fujiwara T, Nakamichi Y, Okamura T, Akimoto Y, Kawai J, Matsushima S, Kawakami H, Watanabe T, Akagawa K, Nagamatsu S. Imaging analysis reveals mechanistic differences between first- and second-phase insulin exocytosis. J Cell Biol 177: 695–705, 2007 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Ohara-Imaizumi M, Nakamichi Y, Tanaka T, Katsuta H, Ishida H, Nagamatsu S. Monitoring of exocytosis and endocytosis of insulin secretory granules in the pancreatic β-cell line MIN6 using pH-sensitive green fluorescent protein (pHluorin) and confocal laser microscopy. Biochem J 363: 73–80, 2002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Orci L, Malaisse-Lagae F, Ravazzola M, Amherdt M, Renold AE. Exocytosis-endocytosis coupling in the pancreatic β-cell. Science 181: 561–562, 1973 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Ostrom RS, Bogard AS, Gros R, Feldman RD. Choreographing the adenylyl cyclase signalosome: sorting out the partners and the steps. Naunyn Schmiedebergs Arch Pharmacol 385: 5–12, 2012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Peterhoff M, Sieg A, Brede M, Chao CM, Hein L, Ullrich S. Inhibition of insulin secretion via distinct signaling pathways in α2-adrenoceptor knockout mice. Eur J Endocrinol 149: 343–350, 2003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Petit P, Loubatières-Mariani MM. Potassium channels of the insulin-secreting β cell. Fundam Clin Pharmacol 6: 123–134, 1992 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Proks P, Ashcroft FM. Effects of divalent cations on exocytosis and endocytosis from single mouse pancreatic β-cells. J Physiol 487: 465–477, 1995 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Redmon JB, Olson LK, Armstrong MB, Greene MJ, Robertson RP. Effects of tacrolimus (FK506) on human insulin gene expression, insulin mRNA levels, and insulin secretion in HIT-T15 cells. J Clin Invest 98: 2786–2793, 1996 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Régnauld KL, Leteurtre E, Gutkind SJ, Gespach CP, Emami S. Activation of adenylyl cyclases, regulation of insulin status, and cell survival by Gαolf in pancreatic β-cells. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol 282: R870–R880, 2002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Renström E, Eliasson L, Rorsman P. Protein kinase A-dependent and -independent stimulation of exocytosis by cAMP in mouse pancreatic β-cells. J Physiol 502: 105–118, 1997 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Ribalet B, Eddlestone GT. Characterization of the G protein coupling of a somatostatin receptor to the K+ATP channel in insulin secreting mammalian HIT and RIN cell lines. J Physiol 485: 73–86, 1995 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Rizzoli SO, Jahn R. Kiss-and-run, collapse and “readily retrievable” vesicles. Traffic 8: 1137–1144, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Rodriguez-Pena MS, Collins R, Woodard C, Spiegel AM. Decreased insulin content and secretion in RIN-1046–38 cells over-expressing α2-adrenergic receptors. Endocrine 7: 255–260, 1997 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Rorsman P, Bokvist K, Ammala C, Arkhammar P, Berggren PO, Larsson O, Wahlander K. Activation by adrenaline of a low-conductance G protein dependent K+ channel in mouse pancreatic β-cells. Nature 349: 77–79, 1991 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Rosengren AH, Jokubka R, Tojjar D, Granhall C, Hansson O, Li DQ, Nagaraj V, Reinbothe TM, Tuncel J, Eliasson L, Groop L, Rorsman P, Salehi A, Lyssenko V, Luthman H, Renström E. Overexpression of α2A-adrenergic receptors contributes to type 2 diabetes. Science 327: 217–220, 2010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Samols E, Marrii G, Marks V. Promotion of insulin secretion by glucagon. Lancet 2: 415–416, 1965 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Schermerhorn T, Sharp GWG. Norepinephrine acts on the KATP channel and produces different effects on [Ca2+]i in oscillating and non-oscillating HIT-T15 cells. Cell Calcium 27: 163–173, 2000 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Seaquist ER, Walseth TF, Redmon JB, Robertson RP. G-protein regulation of insulin secretion. J Lab Clin Med 123: 338–345, 1994 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Seino S, Shibasaki T. PKA-dependent and PKA-independent pathways for cAMP- regulated exocytosis. Physiol Rev 85: 1303–1342, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Sharp GWG. Mechanisms of inhibition of insulin release. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol 271: C1781–C1799, 1996 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Sharp GWG, Le Marchand-Brustel Y, Yada T, Russo LL, Bliss CR, Cormont M, Monge L, Van Obberghen E. Galanin can inhibit insulin release by a mechanism other than membrane hyperpolarization or inhibition of adenylate cyclase. J Biol Chem 264: 7302–7309, 1989 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Shibasaki T, Takahashi H, Miki T, Sunaga Y, Matsumara K, Yamanaka M, Zhang C, Tamamoto A, Satoh T, Miyazaki J, Seino S. Essential role of Epac2/Rap1 signaling in regulation of insulin granule dynamics by cAMP. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 104: 19333–19338, 2007 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Sieg A, Su J, Munoz A, Buchenau M, Nakazaki M, Aguilar-Bryan L, Bryan J, Ullrich S. Epinephrine-induced hyperpolarization of islet cells without KATP channels. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab 286: E463–E471, 2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108.Smillie KJ, Cousin MA. Dynamin 1 phosphorylation and the control of synaptic vesicle endocytosis. Biochem Soc Symp 72: 87–97, 2005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109.Smith C, Moser T, Xu T, Neher E. Cytosolic Ca2+ acts by two separate pathways to modulate the supply of release-competent vesicles in chromaffin cells. Neuron 20: 1243- 1253, 1998 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110.Smith C, Neher E. Multiple forms of endocytosis in bovine adrenal chromaffin cells. J Cell Biol 139: 885–894, 1997 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 111.Sovantus E, Fagerholm V, Rahkonen O, Scheinin M. Reduced blood glucose levels, increased insulin levels and improved glucose tolerance in α2A-adrenergic receptor knockout mice. Eur J Pharmacol 578: 359–364, 2008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 112.Stevens CF, Sullivan JM. Regulation of the readily releasable vesicle pool by protein kinase C. Neuron 21: 885–893, 1998 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 113.Straub SG, Shanmugam G, Sharp GWG. Stimulation of insulin release by glucose is associated with an increase in the number of docked granules in the β-cells of rat pancreatic islets. Diabetes 53: 3179–3183, 2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 114.Straub SG, Sharp GWG. Glucose-stimulated signaling pathways in biphasic insulin secretion. Diabetes Metab Res Rev 18: 451–463, 2002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 115.Straub SG, Sharp GWG. Hypothesis: one rate-limiting step controls the magnitude of both phases of glucose-stimulated insulin secretion. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol 287: C565–C571, 2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 116.Südhof TC, Rothman JE. Membrane fusion: grappling with SNARE and SM proteins. Science 323: 474–477, 2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 117.Sugawara K, Shibasaki T, Mizoguchi A, Saito T, Seino S. Rab11 and its effector Rip11 participate in regulation of insulin granule exocytosis. Genes Cells 14: 445–456, 2009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 118.Szentivanyi A, Fishel CW, Talmadge DW. Adrenal mediation of histamine and serotonin hyperglycemia in normal mice and the absence of adrenal-induced hyperglycemia in pertussis sensitized mice. J Infect Dis 113: 86–91, 1963 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 119.Szollosi A, Nenquin M, Aguilar-Bryan L, Bryan J, Henquin JC. Glucose stimulates Ca2+ influx and insulin secretion in 2-week-old β-cells lacking ATP-sensitive K+ channels. J Biol Chem 282: 1747–1756, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 120.Szollosi A, Nenquin M, Henquin JC. Pharmacological stimulation and inhibition of insulin secretion in mouse islets lacking ATP-sensitive K+ channels. Br J Pharmacol 159: 669–677, 2010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 121.Toyota T, Kakizaki M, Kimura K, Yajima M, Okamoto T, Ui M. Islet activating protein (IAP) derived from the culture supernatant fluid of Bordetella pertussis: effect on spontaneous diabetic rats. Diabetologia 14: 319–323, 1978 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 122.Tsuboi T, McMahon HT, Rutter GA. Mechanisms of dense core vesicle recapture following “kiss and run” (“cavicapture”) exocytosis in insulin-secreting cells. J Biol Chem 279: 47115–47124, 2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 123.Turner JH, Garnovskaya MN, Raymond JR. Serotonin 5-HT1A receptor stimulates c-Jun N-terminal kinase and induces apoptosis in Chinese hamster ovary fibroblasts. Biochim Biophys Acta 1773: 391–399, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 124.Ullrich S, Wollheim CB. Expression of both α1 and α2-adrenoceptors in an insulin-secreting cell line. Parallel studies of cytosolic free Ca2+ and insulin release. Mol Pharmacol 28: 100–106, 1985 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 125.Voets T, Neher E, Moser T. Mechanisms underlying phasic and sustained secretion in chromaffin cells from mouse adrenal slices. Neuron 23: 607–615, 1999 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 126.Wan QF, Dong Y, Yang H, Lou X, Ding J, Xu T. Protein kinase activation increases insulin secretion by sensitizing the secretory machinery to Ca2+. J Gen Physiol 124: 653–662, 2004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 127.Wang Y, Park Bajpayee NS S, Nagaoka Y, Boulay G, Birnbaumer L. Augmented glucose-induced insulin release in mice lacking Go2, but not Go1 or Gi proteins. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 108: 1693–1698, 2011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]