Abstract

Gastrin stimulates the growth of pancreatic cancer cells through the activation of the cholecystokinin-B receptor (CCK-BR), which has been found to be overexpressed in pancreatic cancer. In this study, we proposed that the CCK-BR drives growth of pancreatic cancer; hence, interruption of CCK-BR activity could potentially be an ideal target for cancer therapeutics. The effect of CCK-BR downregulation in the human pancreatic adenocarcinoma cells was examined by utilizing specific CCK-BR-targeted RNA interference reagents. The CCK-BR receptor expression was both transiently and stably downregulated by transfection with selective CCK-BR small-interfering RNA or short-hairpin RNA, respectively, and the effects on cell growth and apoptosis were assessed. CCK-BR downregulation resulted in reduced cancer cell proliferation, decreased DNA synthesis, and cell cycle arrest as demonstrated by an inhibition of G1 to S phase progression. Furthermore, CCK-BR downregulation increased caspase-3 activity, TUNEL-positive cells, and decreased X-linked inhibitor of apoptosis protein expression, suggesting apoptotic activity. Pancreatic cancer cell mobility was decreased when the CCK-BR was downregulated, as assessed by a migration assay. These results show the importance of the CCK-BR in regulation of growth and apoptosis in pancreatic cancer. Strategies to decrease the CCK-BR expression and activity may be beneficial for the development of new methods to improve the treatment for patients with pancreatic cancer.

Keywords: gastrin, G protein-coupled receptor, ribonucleic acid interference

pancreatic cancer ranks as the fourth most common cause of cancer-related mortality with a five-year survival rate of <1% and a median survival of 3–6 mo. Although numerous chemotherapeutic drugs have been tested in this malignancy, survival of advanced pancreatic cancer has not improved over the past several decades. Because of the lack of effective treatment options available for this disease, identification of novel targets and approaches is desperately needed. G protein-coupled receptors have been shown to play an important role in mediating tumor growth and metastasis (17). Through its interaction with gastrin, the G protein-coupled receptor, cholecystokinin-B receptor (CCK-BR), mediates the growth of several gastrointestinal cancers such as colon (29, 39, 46, 50), stomach (45, 48), and pancreas (40, 42, 43, 49).

The human CCK-BR has been shown to be upregulated in pancreatic cancer compared with normal tissues (41). The human pancreas produces gastrin during fetal development, after which gastrin expression is downregulated, and no gastrin can be detected in the healthy adult pancreas. However, gastrin is reexpressed in pancreatic tumors where it enhances proliferation through an autocrine mechanism (44). Evidence that both the receptor and ligand become upregulated in pancreatic cancer suggest it may be an important pathway involved in pancreatic cancer development and growth. Previous work has shown that stable, long-term reduction in gastrin expression through RNA interference (RNAi) techniques significantly reduces pancreatic tumor growth and metastasis in vivo (27). CCK is a ligand for both the CCK-BR and CCK-A receptor (AR), and is also reexpressed by pancreatic tumors. However, RNAi downregulation of endogenous CCK had virtually no effect on human pancreatic tumor growth (28), suggesting that the CCK-BR interaction with gastrin is the important mediator of growth in gastrointestinal malignancies.

The CCK-BR has also been reported to play an important role in carcinogenesis. Ectopic expression of the CCK-BR in a nontumorigenic, gastrin-producing colon epithelial cell line was sufficient to transform these cells into tumorigenic cells (9). Additional evidence of the CCK-BR's contribution to carcinogenesis is supported by studies involving transgenic mice (12, 21, 38). Transgenic expression of the CCK-BR in murine pancreatic acinar cells results in increased pancreas growth, transdifferentiation of acinar cells into ductal structures, and development of pancreatic cancer (12). Although overexpression of progastrin in mice induces hyperproliferation of the colon and promotes colorectal cancer (38), mice carrying CCK-BR knockout alleles have reduced gastrin-dependent colonic proliferation, fewer aberrant crypt foci, and decreased tumor size (21). Furthermore, while progastrin may play an important role in proliferation and colon carcinogenesis through its actions at the annexin A2 receptor (36), gastrin-17 is the major form of gastrin involved in pancreatic cancer growth (28, 44).

Binding of gastrin to CCK-BR activates a diverse group of intracellular signaling pathways (1, 18). In the rat exocrine pancreatic cell line AR42J, gastrin stimulation activates protein kinase B (Akt), which promotes survival by phosphorylating the proapoptotic protein BAD (33, 47). Similarly, Akt is phosphorylated in response to gastrin stimulation in human esophageal cancer cells (20). Stimulation of gastric epithelial cells with gastrin upregulates expression of the anti-apoptotic proteins Bcl-2 and survivin (22). The mitogen-activated protein kinase and Akt pathways also are involved in gastrin-induced cyclooxygenase-2 expression in colon cancer cells (13). In another gastrointestinal malignancy, gastric cancer, downregulation of the CCK-BR in cell lines increased caspase-3 expression and apoptosis (52). It was hypothesized that, since growth of pancreatic cancer cells is regulated by the interaction of gastrin with the CCK-BR, downregulation of the CCK-BR will inhibit pancreatic cancer growth and promote apoptosis. In this study, we examined the effects of downregulation of the CCK-BR on proliferation and apoptosis in human pancreatic cancer cells.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Cell lines.

Human pancreatic cancer cell lines AsPC-1, MIA PaCa-2 , and PANC-1 were purchased from the ATCC (Rockville, MD) and were maintained in appropriate media with 10% FBS (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA). In a previous study, a panel of human pancreatic cancer cell lines was evaluated for CCK-BR mRNA expression by real-time RT-PCR (28), and PANC-1 cancer cells were found to express the most CCK-BR mRNA. Therefore, further studies establishing stable clones with short-hairpin RNA (shRNA) transfection were done using PANC-1 cancer cells.

Inhibition of CCK-BR with RNAi.

Two independent CCK-BR-specific stealth small-interfering RNAs (siRNAs) [HSS189635, si849 (CCGUACUGCUGCUUCUGGUCUUGUU) and HSS141489, si564 (CCGUCAUCUGCAAGGGGGUUUCCUA)] and control siRNA (Medium GC Duplex no. 2, no. 12935–112) were obtained from Invitrogen. In addition, two independent shRNAs that targeted different regions of CCK-BR mRNA were selected based upon RNA secondary structure. The shRNA duplexes started at the following base locations in the CCK-BR RNA: GenBank no. AF441129, sites sh377 (CTGCAAGGCGGTTCCTAC) and sh1413 (GAAACTTGCGCTCGCTGC) (Oligoengine, Seattle, WA). A nonspecific shRNA control (NSC) containing a shRNA oligonucleotide duplex with no known homology to any mammalian gene sequence was used as a negative control. Each shRNA duplex was cloned into the pSuper.hygro vector, and shRNA-containing plasmids were verified by DNA sequence analysis.

For the RNAi experiments, AsPC-1, MIA PaCa-2, or PANC-1 cells were transfected with CCK-BR siRNAs with Lipofectamine 2000 (Invitrogen). RNA was isolated after 48 h to evaluate mRNA downregulation. Stable PANC-1 CCK-BR shRNA-expressing clones were transfected and selected by hygromycin resistance. CCK-BR mRNA knockdown in shRNA-transfected clones was verified by real-time RT-PCR as described below.

Real-time RT-PCR analysis.

RNA was extracted using an RNAeasy kit (Qiagen, Valencia, CA), and cDNA was produced using the High-Capacity cDNA Reverse Transcriptase Kit (ABI, Carlsbad, CA) with 2 μg of RNA per reaction. Real-time PCR was carried out with 200 ng of cDNA per reaction using ABI Taqman master mix and CCK-BR primers (HS00176123_m1) or CCK-A receptor primers (HS00167891_m1) with cyclophilin A (HS99999904_m1) as the internal control. All reactions were performed in quadruplicate. PCR amplification and analysis were done with the Applied Biosystems Sequence Detection System 7900 HT using the Relative Quantification (ddCt) Plate setup. RNA levels are calculated from the mean relative quantity (RQ = 2−ΔΔCT) with a 95% confidence interval [CI; RQ = 2−(ΔΔCT ± CI)].

Receptor binding assays.

Pancreatic cancer cells (wild-type, nonspecific control clones, and CCK-BR shRNA clones) were grown to log phase. Cells were washed two times in 0.154 M NaCl, scraped with a rubber policeman, and centrifuged at 1,800 g for 10 min at 4°C. The cell pellet was resuspended in 50 mM Tris·HCl, pH 7.4, with 0.1 mM bacitracin and 1 tablet of Complete, mini, EDTA-free Protease Inhibitor Cocktail protease inhibitor cocktail/50 ml buffer (Roche, Indianapolis, IN). Cells were homogenized with a Brinkman Polytron and then centrifuged at 48,000 g for 30 min at 4°C to pellet cell membranes, and the membrane fraction was resuspended in an incubation buffer previously described (42) containing 0.1% BSA. Homogenates (total protein 200–400 μg/ml) were reacted with 125I-labeled gastrin (Perkin Elmer, Billerica, MA) for 60 min at 4°C, and the reaction was terminated by rapid filtration through Whatman GF/B filters with a Brandel harvester. Nonspecific binding was evaluated using 1 μM of unlabeled gastrin (Peninsula Laboratories, Carlsbad, CA). Radioactivity was assessed on a gamma scintillation counter with 80% efficiency, and receptor binding capacity (Bmax) was determined by using Prism Software (Graphpad). Each assay was performed in duplicate, and each sample was done in duplicate or triplicate.

Cell growth evaluation and bromodeoxyuridine assay.

PANC-1 cells were seeded onto a 12-well plate at a density of 30,000 cells/well. On the following day, cells were transfected with vehicle (Lipofectamine 2000), control siRNA, or CCK-BR siRNA. Each day following transfection, cell growth was evaluated by staining cells with trypan blue and counting viable cells on a hemocytometer. For proliferation assays, AsPC-1, MIA PaCa-2, and PANC-1 cells were seeded on a 96-well plate at a density of 2,500 cells/well and cultured for 72 h. CellTiter 96 Aqueous One Solution, an 3-(4,5-dimethylthiazol-2-yl)-5-(3-carboxymethoxyphenyl)-2-(4-sulfophenyl)-2H-tetrazolium (MTS) assay reagent (Promega, Madison, WI), was added to each well, plates were incubated at 37°C for 1 h, and absorbance was read at 490 nm. Bromodeoxyuridine (BrdU) incorporation was measured using a colorimetric enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay-based kit (Roche). Transfected cells were incubated with BrdU for the last 16 h of the 72-h treatment with siRNA, and BrdU incorporation was assessed as described in the manufacturer's protocol.

Cell cycle analysis.

For cell cycle analysis, PANC-1 cells were transfected with CCK-BR siRNA or control siRNA, and, after 72 h, cells were fixed in 75% ethanol. Cells were then stained with 50 μg/μl of propidium iodide and treated with 1 μg/μl of RNase A. Control siRNA and CCK-BR siRNA samples were run on the FACSCalibur flow cytometer (BD Biosciences, San Diego, CA), and data were analyzed with Cellquest (Verity Software, Topsham, ME).

Apoptosis assays.

Caspase-3 activity was measured using the Colorimetric CaspACE Assay (Promega). Seventy-two hours after transfection with siRNA, PANC-1 cells were collected, resuspended in cell lysis buffer at a concentration of 108 cells/ml, and lysed by freeze-thaw. The assay was performed as described in the manufacturer's protocol using 150 μg of protein/sample.

Apoptotic cells were detected using the APO-BrdU TUNEL assay kit (Invitrogen). Briefly, PANC-1 cells were collected 96 h after transfection with siRNA and immediately fixed in 1% paraformaldehyde. Cells were incubated in a DNA-labeling solution (TdT and BrdUTP) for 3 h at 37°C, washed, and incubated with anti-BrdU Alexa Fluor 488-labeled antibody for 30 min at room temperature. Samples were immediately analyzed by flow cytometry.

Protein extraction and western blot analysis.

Protein for Western blots was harvested 72 h after transfection with siRNA. Total protein was determined using a MicroBCA assay (Pierce/Thermo Fisher Scientific, Rockford, IL). Whole cell lysates (50 μg of protein/well) were mixed with Laemmli's reducing sample buffer, resolved by SDS-PAGE, and electrophoretically transferred to 0.2-μm nitrocellulose membranes. Blots were blocked in 3% nonfat dry milk or 3% ovalbumin (A7641; Sigma, St. Louis, MO) and incubated overnight (4°C) with primary antibodies. Antibodies and titers used were as follows: phosphorylated-Akt (Ser473) 1:1,000 (no. 4060; Cell Signaling Technology, Danvers, MA), Akt (pan) 1:2,000 (no. 4691; Cell Signaling Technology), X-linked inhibitor of apoptosis protein (XIAP) 1:1,000 (no. 610716; BD Biosciences), and β-actin 1:10,000 (A2228; Sigma). The blots were washed and probed with species-specific secondary antibodies coupled to horseradish peroxidase (Amersham, Piscataway, NJ), and the signal was detected using an enhanced chemiluminescence substrate (Pierce/Thermo Fisher Scientific).

Migration assay.

Pancreatic cancer cells (wild-type, nonspecific control clones, and CCK-BR shRNA clones) were seeded on 12-well plates and allowed to grow to confluency. A scratch in the monolayer was created with a 200-μl pipet tip. Phase-contrast (CKX41; Olympus, Tokyo, Japan) photographs were taken immediately following the scratch (0 h) and 24 h after the scratch. Scratch width was measured using Axio Vision (Carl Zeiss MicroImaging) software, and the percentage of the scratch area closed was calculated as (width at 0 h − width at 24 h)/width at 0 h. Results were standardized to wild type.

Statistics.

Results are expressed as means ± SE. Statistical comparisons were made using the two-tailed Student's t-test. A P value of <0.05 was considered to be statistically significant, and a modified Bonferroni method was used to correct for multiple comparisons. For the real-time data, pairwise Student's t-tests were performed on the normalized mean ΔCT values for each group.

RESULTS

CCK-BR RNAi effectively decreases receptor expression.

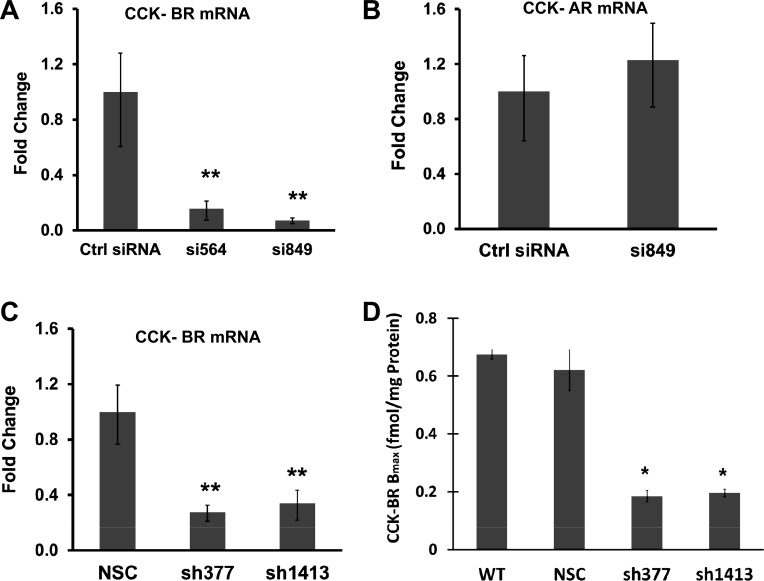

Two CCK-BR-specific siRNAs (targeted to different regions of CCK-BR mRNA) were tested for their ability to downregulate the receptor in PANC-1 cells. Both siRNAs, si564 and si849, were effective in decreasing CCK-BR mRNA as demonstrated by real-time RT-PCR (Fig. 1A). Because CCK-BR si849 was highly effective in downregulating CCK-BR expression in PANC-1 cells >90%, si849 was used to downregulate CCK-BR in all subsequent siRNA experiments. The CCK-BR siRNA (si849)-transfected cells did not have altered expression of the CCK-AR (Fig. 1B), indicating the specificity of this siRNA for the CCK-BR. Similarly, CCK-BR mRNA expression was decreased in PANC-1 cells stably transfected with the sh377 or sh1413 construct (Fig. 1C). Although si849, sh377, and sh1413 each target separate regions of the CCK-BR mRNA, all were highly effective in knocking down CCK-BR mRNA. The CCK-BR mRNA was also decreased in siRNA-treated AsPC-1 and MIA PaCa-2 cancer cells (data not shown).

Fig. 1.

Downregulation of the cholecystokinin-B receptor (CCK-BR) in cells treated with small-interfering RNA (siRNA) and short-hairpin RNA (shRNA). A: real-time RT-PCR analysis of two independent CCK-BR-targeted siRNA (si564 and si849) were examined for their ability to downregulate the CCK-BR mRNA. siRNA-treated cells were standardized to the control siRNA (Ctrl siRNA), n = 6. B: expression of CCK-A receptor (CCK-AR) mRNA in cells treated with si849 is unchanged compared with control siRNA. C: two independent shRNA CCK-BR-targeted sequences (sh377 and sh1413) were examined by real-time RT-PCR for their ability to downregulate CCK-BR mRNA. CCK-BR shRNA cells were standardized to nonspecific shRNA control (NSC) cells, n = 4. For all real-time RT-PCR data, columns represent the fold change in mRNA levels calculated from the mean relative quantity (RQ = 2−ΔΔCT), and bars represent a 95% confidence interval [CI; RQ = 2−(ΔΔCT ± CI)]. wwwD: receptor binding assay for CCK-BR shRNA clones. Columns represent median receptor binding capacity (Bmax) in fmol/mg protein of various shRNA clones compared with the wild-type (WT) controls and the clones transfected with NSC, n = 3. *P ≤ 0.05 and **P < 0.01.

To confirm that the downregulation of the CCK-BR mRNA resulted in decreased receptor protein, receptor-binding assays were performed on the PANC-1 CCK-BR shRNA clones, NSCs, and wild-type cells with 125I-labeled gastrin-17. Receptor binding affinity was in the nanomolar range, comparable with the physiological range previously determined to stimulate growth (44). There was no difference in receptor number of the wild-type cells compared with the PANC-1 nonspecific control shRNA clones (Fig. 1D). The Bmax was significantly decreased by 73 and 71%, respectively, in sh377 and sh1413 clones compared with wild-type and nonspecific control clones.

Downregulation of the CCK-BR decreases proliferation.

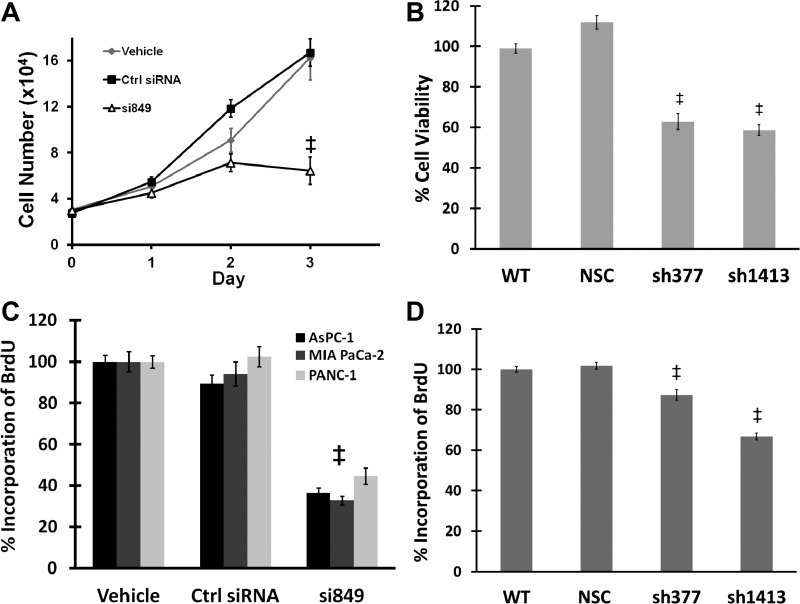

At 72 h after transfection, CCK-BR siRNA-treated PANC-1 cells displayed a significant decrease in cell number. Growth of CCK-BR siRNA-treated PANC-1 cells was reduced by 73% compared with cells treated with control siRNA and by 69% compared with vehicle-treated cells (P < 0.001, Fig. 2A). A decrease in cell viability was also seen in both (sh377 and sh1413) stable CCK-BR shRNA clones compared with wild-type and nonspecific control shRNA cells (Fig. 2B) as measured by the MTS cell proliferation assay. The decrease in cell growth upon downregulation of the CCK-BR suggests that CCK-BR inactivation may block DNA synthesis, and this finding was confirmed by BrdU labeling (Fig. 2C) in three pancreatic cancer cell lines, AsPC-1, MIA PaCa-2, and PANC-1. All cancer cell lines treated with siRNA CCK-BR had decreased BrdU incorporation compared with control siRNA-treated cells and vehicle-treated cells. CCK-BR sh377 clones and sh1413 clones had significantly less BrdU incorporation compared with wild-type and nonspecific control clones (P < 0.001; Fig. 2D). These findings support the relationship between the CCK-BR and proliferation in pancreatic cancer.

Fig. 2.

Proliferation is decreased after downregulation of the CCK-BR. A: growth of CCK-BR siRNA-transfected PANC-1 cells. Cells transfected with CCK-BR-targeted siRNA demonstrated a significant decrease in growth compared with the control siRNA and vehicle, n = 9. B: cell viability of the CCK-BR shRNA clones is reduced compared with controls as measured by 3-(4,5-dimethylthiazol-2-yl)-5-(3-carboxymethoxyphenyl)-2-(4-sulfophenyl)-2H-tetrazolium (MTS) assay. Results are standardized to WT, n = 10. C: bromodeoxyuridine (BrdU) assay of CCK-BR siRNA-transfected AsPC-1, MIA PaCa-2, and PANC-1 cells. Cells with downregulation of CCK-BR incorporated less BrdU compared with controls. Results are standardized to vehicle, n = 10. D: BrdU assay of the CCK-BR shRNA clones. Cells with downregulation of CCK-BR incorporated less BrdU than WT cells, n = 10. ‡P < 0.001.

Downregulation of the CCK-BR inhibits G1/S progression.

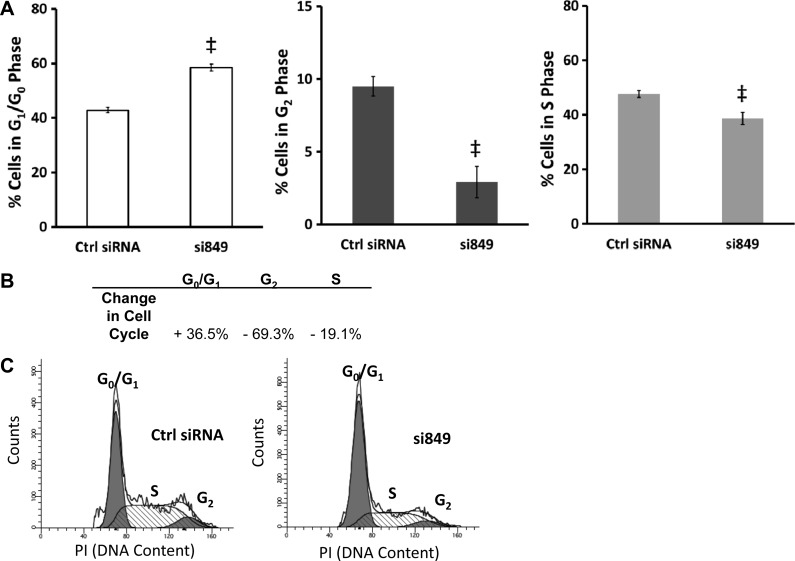

Cell cycle analysis performed on cells with downregulation of the CCK-BR confirmed the reduction in DNA synthesis and cell growth observed in CCK-BR siRNA-transfected PANC-1 cells. CCK-BR siRNA-treated PANC-1 cells had a 36% increase in cells residing in G1/G0 phase compared with control siRNA-transfected cells (Fig. 3). Correspondingly, CCK-BR downregulation led to 69% fewer cells in G2 phase and 19% fewer cells in S phase compared with control siRNA (Fig. 3). Taken together, these data indicate that downregulation of the CCK-BR results in an inhibition of G1/S progression.

Fig. 3.

CCK-BR downregulation decreases G1/S phase progression. Cell cycle analysis by propidium iodide (PI) staining and flow cytometry in cells with CCK-BR knockdown compared with control siRNA. A: percentage of cells in G1/G0, G2, and S phase, n = 8. ‡P < 0.001. B: change in cell cycle phase of CCK-BR siRNA-transfected cells relative to control siRNA. C: representative cell cycle histograms demonstrating the change in cell cycle.

Alteration of apoptotic markers with downregulation of the CCK-BR.

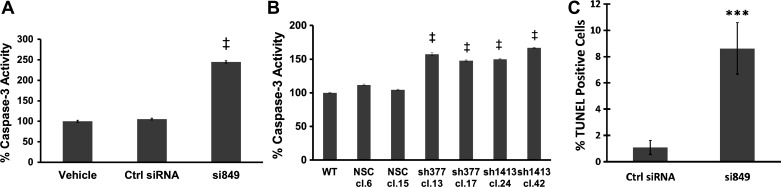

Although downregulation of the CCK-BR inhibits proliferation, is it sufficient to promote apoptosis? To answer this question, several markers of apoptosis were analyzed in PANC-1 cells with downregulation of the CCK-BR either by siRNA or shRNA. CCK-BR downregulation resulted in an increase in caspase-3 activity compared with vehicle and control siRNA-treated cells (P < 0.001, Fig. 4A). Similar results were observed with the CCK-BR shRNA clones, where all sh377 and sh1413 clones had higher capase-3 activity than untransfected cells or NSC clones (P < 0.001, Fig. 4B). In addition to increased caspase-3 activity, the effect of downregulation of CCK-BR on the apoptotic cell population was confirmed by TUNEL assay. PANC-1 cells treated with CCK-BR siRNA displayed a significant increase in TUNEL-positive cells compared with control siRNA-treated cells (P < 0.005, Fig. 4C).

Fig. 4.

Apoptotic activity increases with downregulation of the CCK-BR. A: caspase-3 activity increases in cells transfected with CCK-BR siRNA. Results are standardized to vehicle, n = 7. B: caspase-3 activity is increased in CCK-BR shRNA clones. Results are standardized to WT, n = 5. C: percentage of TUNEL-positive cells measured by flow cytometry is increased in cells transfected with CCK-BR siRNA, n = 5. ***P < 0.005 and ‡P < 0.001.

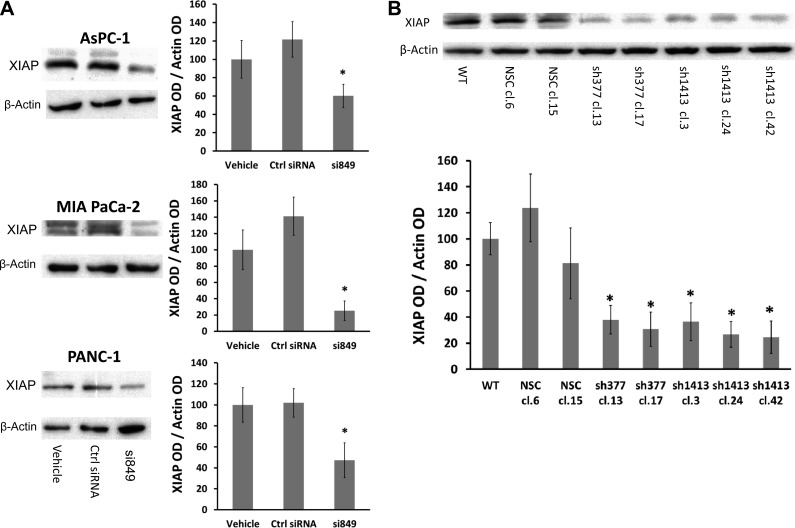

Expression of XIAP is known to be upregulated in pancreatic cancer (25, 37, 37). XIAP binds to active caspase-3 (15, 16) and blocks the increased capase-3 activity induced during apoptosis. XIAP expression in CCK-BR siRNA-treated cells and CCK-BR shRNA clones was examined. After downregulation of the CCK-BR with siRNA in AsPC-1, MIA PaCa-2, and PANC-1 cells, XIAP expression was significantly lower than in control siRNA- and vehicle-treated cells (P < 0.05, Fig. 5A). The reduction in XIAP expression also occurred in the CCK-BR shRNA clones. XIAP levels were reduced in both shRNA 377 and shRNA 1413 clones compared with wild-type and NSC clones (P < 0.05, Fig. 5B).

Fig. 5.

X-linked inhibitor of apoptosis protein (XIAP) expression decreases with downregulation of the CCK-BR. A: representative Western blot of XIAP in CCK-BR siRNA-transfected AsPC-1, MIA PaCa-2, and PANC-1 cells and quantification of XIAP by densitometry. Results are standardized to vehicle. B: representative Western blot of XIAP in CCK-BR shRNA clones and quantification of XIAP by densitometry. Results are expressed as a percentage and standardized to WT. The ratio of XIAP to each corresponding β-actin band was calculated, n = 3. *P < 0.05.

Downregulation of the CCK-BR decreases Akt phosphorylation and migration.

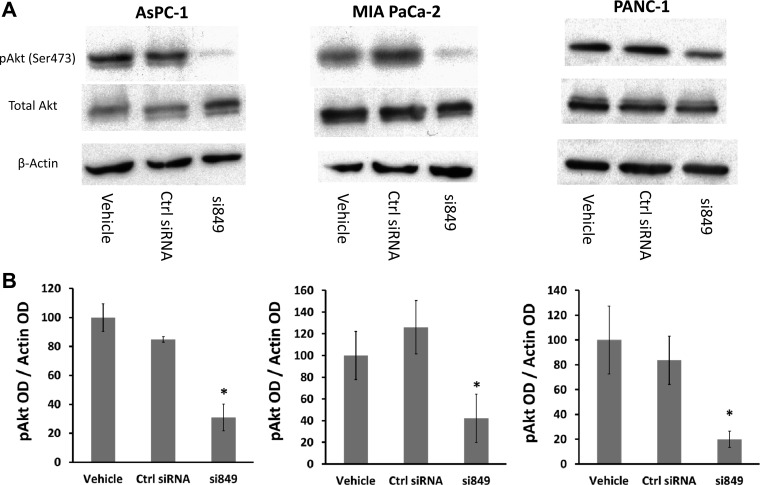

The prosurvival signaling protein Akt is known to be phosphorylated and activated as a result of normal interaction of gastrin with the CCK-BR (47). Akt phosphorylation leads to increased XIAP levels by blocking ubiquitination and proteasomal degradation of XIAP (14). Because downregulation of the CCK-BR drastically reduces XIAP levels, we would predict that downregulation of CCK-BR would also cause a reduction in Akt phosphorylation. Although total Akt levels were unchanged in CCK-BR siRNA-treated cells, Akt phosphorylation at Ser473, which is important for the activation of Akt, was significantly decreased by CCK-BR siRNA treatment in AsPC-1, MIA PaCa-2, and PANC-1 cells (P < 0.05, Fig. 6).

Fig. 6.

Downregulation of the CCK-BR inhibits protein kinase B (Akt) phosphorylation. A: representative Western blot of Akt phosphorylation in CCK-BR siRNA-transfected AsPC-1, MIA PaCa-2, and PANC-1 cells. B: quantification of phosphorylated (p) Akt by densitometry. The ratio of pAkt to each corresponding β-actin band was calculated. Results are expressed as a percentage and standardized to vehicle, n = 3. *P < 0.05.

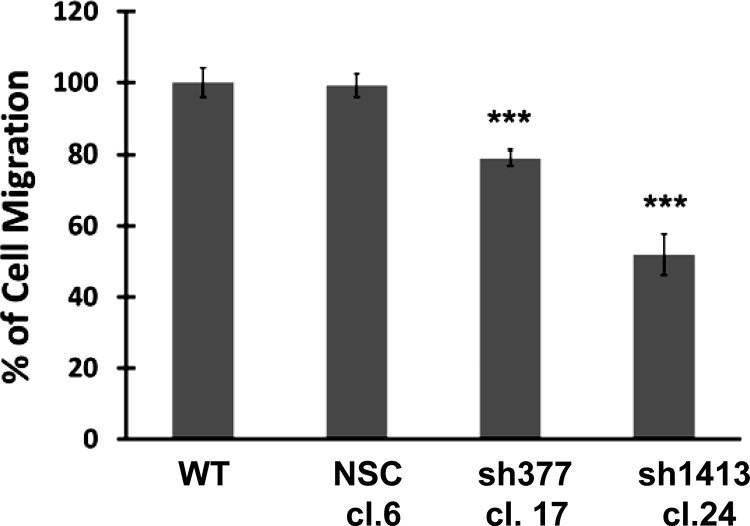

Because the phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase (PI3K) pathway and Akt phosphorylation are known to mediate cell migration (4), scratch-wound assays were performed to assess cell migration in response to downregulation of the CCK-BR. Compared with untransfected wild-type cells or NSC clones, both CCK-BR shRNA clones demonstrated a decrease in migration (P < 0.005, Fig. 7).

Fig. 7.

Downregulation of the CCK-BR decreases cell migration by scratch-wound assay. Migration in CCK-BR shRNA clones is expressed as a percentage of wound repair and standardized to WT, n = 6. ***P < 0.005.

DISCUSSION

The present study demonstrates that the CCK-BR is a potential target for developing novel strategies for the treatment of pancreatic cancer and further defines pathways affected by CCK-BR signaling. This study establishes that downregulation of the CCK-BR increases apoptotic activity, and decreases proliferation, XIAP expression, Akt activation, and migration, suggesting that the CCK-BR is an important receptor regulating growth of pancreatic cancer. Although AsPC-1, MIA PaCA-2, and PANC-1 cells have different levels of CCK-BR mRNA expression (28), with expression highest in PANC-1 cells, downregulation of the receptor decreased BrdU incorporation, XIAP expression, and Akt phosphorylation to a similar level in all three cell lines regardless of CCK-BR expression or degree of differentiation.

In addition to decreasing cellular proliferation, G1/S progression is inhibited with downregulation of the CCK-BR, suggesting that downregulating this receptor induces cell cycle arrest. Cyclins that control G1/S transition have been found to be influenced by gastrin. Gastrin increases transcription of cyclin D1, D3, and E in a human gastric adenocarcinoma cell line and Swiss 3T3 cells that express the CCK-BR (31, 53). Therefore, it is possible that downregulation of the CCK-BR may reduce cyclin D transcription and result in cell cycle dysfunction.

The increase in caspase-3 activity in PANC-1 cells treated with CCK-BR siRNA or in cells with stable shRNA-mediated downregulation of CCK-BR is consistent with other studies (27, 52). Herein, our results demonstrated for the first time that XIAP expression is decreased when the CCK-BR is downregulated. Many pancreatic cancer cell lines exhibit constitutive activation of Akt mediated through dysregulated phosphatase and tensin homolog (PTEN) expression (2, 3). Gastrin stimulation activates Akt phosphorylation through the CCK-BR (47), and this study demonstrates that downregulation of the CCK-BR in PANC-1 cells inhibits phosphorylation of Akt. Activated Akt is known to regulate XIAP by phosphorylation at Ser87. Phosphorylation of XIAP by Akt protects XIAP against ubiquitination and proteasomal degradation (14). The decrease in XIAP expression observed upon CCK-BR downregulation is consistent with the decrease in activated Akt brought on by the CCK-BR siRNA treatment.

Akt, an integral part of the PI3K pathway, is involved in mediation of cell migration. We demonstrated that CCK-BR downregulation inhibits Akt phosphorylation and cell migration. Others have demonstrated that signaling pathways activated by the CCK-BR can regulate cellular adhesion by gastrin-induced modifications of p120, α- and β-catenins, and E-cadherin in intestinal epithelial cells (19). More recently, in pancreatic cancer cells, the CCK-BR has been shown to regulate β1- and αv-integrins, which are involved in modulation of cell adhesion via the PI3K pathway (7, 8).

Gemcitabine, the current standard of care treatment for pancreatic cancer, offers a low response rate, and only increases survival time by a mean of six months. Given alone, most therapeutic agents that target cancer cell-signaling pathways, particularly tyrosine kinase receptor-signaling pathways, are not effective in decreasing pancreatic tumor growth and metastasis (32). Even small molecule inhibitors of the PI3K/Akt pathway have failed to demonstrate efficacy in clinical trials with pancreatic cancer patients (34). Unfortunately, the approach of “one size fits all” has not been effective in treating pancreatic cancer. Recently, a set of genes identified as “driver genes” have been described in pancreatic cancer (23). Among these, Carter et al. (6) describe a PI3K suppressor gene SNP (PIK3CG/R839C), which has the second highest scoring predicted driver mutation among these genes in pancreatic cancer. Because PI3Kγ transmits signals downstream from G protein-coupled receptors, Korc (23) suggested that there may be a connection between mutations in PIK3CG and activation of the CCK-BR. Knowing this is a key pathway in pancreatic cancer growth, interruption of the CCK-BR signaling pathway may lead to advances in the treatment of pancreatic cancer. Therapies directed toward Kras, another driver mutation, which is mutated early on in the development of pancreatic cancer in the precursor pancreatic intraepithelial neoplasms lesions, have not improved survival (26), suggesting that Kras alone is not controlling growth of pancreatic cancer. Moreover, recent studies suggest that G protein-coupled receptor signaling systems play a critical role in mitogenic signaling and are implicated in the growth of multiple solid tumors, including the pancreas (35, 51). Because the CCK-BR promotes growth primarily in gastrointestinal cancers like pancreatic cancer and downregulation of the CCK-BR blocks pancreatic cancer cell growth, targeting the CCK-BR as a possible pancreatic cancer therapy is promising.

Although many CCK-BR antagonists have been identified, there are no drugs targeting the CCK-BR in clinical use because of their poor biodistribution and pharmacokinetics (5). Two pharmacological agents that target the CCK-BR have been evaluated in clinical trials for treatment of pancreatic cancer. The first compound, gastrazole, is a high-affinity CCK-BR antagonist. When compared with placebo, pancreatic cancer patients treated with gastrazole showed a slight increase in survival (10). Unfortunately, the very low oral bioavailability of gastrazole required that the drug be administered intravenously. Z-360, a more recently developed orally active CCK-BR antagonist, was evaluated in phase Ib/IIa clinical trials in combination with gemcitabine (30). Although a trend toward reduced pain and increased survival were observed, these differences were not statistically significant. However, in both trials that compared CCK-BR antagonists with conventional therapeutics, Z-360 and gastrazole had low toxicity and high tolerability. The results of tolerability of these drugs agree with previous work where the CCK-BR was knocked out in mice.

Although the potential for CCK-BR-targeted therapies is evident, the current pharmacological antagonists for the CCK-BR are inadequate. The development of an RNAi-based approach to selectively downregulate CCK-BR expression holds promise for a more efficient therapy. Previous work examining CCK-BR knockout mice demonstrated that these animals had few phenotypic differences from wild-type mice. CCK-BR-deficient mice had increased gastric pH, more G cells, and a decrease in the thickness of the oxyntic mucosa of the stomach (11, 24). Evidence from the CCK-BR knockout mouse model and the CCK-BR antagonist clinical trials supports the idea that targeting the CCK-BR as a therapeutic strategy can be effective and well tolerated. Our current studies indicate that the development of targeted therapeutics against the CCK-BR, including RNAi-based therapies, for pancreatic cancers and for other gastrin-dependent malignancies will be an important new direction in treating these diseases.

GRANTS

This work was supported National Cancer Institute Grant R01 CA-117926 to J. P. Smith.

DISCLOSURES

No conflicts of interest, financial or otherwise, are declared by the authors.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

Author contributions: K.K.F., G.L.M., C.O.M., E.L.G., and J.P.S. performed experiments; K.K.F. and C.O.M. analyzed data; K.K.F. and J.P.S. interpreted results of experiments; K.K.F. prepared figures; K.K.F. drafted manuscript; K.K.F., G.L.M., and J.P.S. edited and revised manuscript; K.K.F., G.L.M., C.O.M., E.L.G., and J.P.S. approved final version of manuscript; J.P.S. conception and design of research.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We acknowledge the technical assistance of the following members of the Section of Research Resources, Pennsylvania State College of Medicine: David Stanford and Nate Scheaffer in the Cell Science Flow Cytometry Core, Joe Bednarczyk in the DNA Sequencing Core, and Rob Brucklacher and Georgina Bixler in the Functional Genomics Core. We appreciate the expert assistance of John Harms, Messiah College, in designing the CCK-BR shRNAs.

REFERENCES

- 1. Aly A, Shulkes A, Baldwin GS. Gastrins, cholecystokinins and gastrointestinal cancer. Biochim Biophys Acta 1704: 1–10, 2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Asano T, Yao Y, Zhu J, Li D, Abbruzzese JL, Reddy SA. The PI 3-kinase/Akt signaling pathway is activated due to aberrant Pten expression and targets transcription factors NF-kappaB and c-Myc in pancreatic cancer cells. Oncogene 23: 8571–8580, 2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Bondar VM, Sweeney-Gotsch B, Andreeff M, Mills GB, McConkey DJ. Inhibition of the phosphatidylinositol 3'-kinase-AKT pathway induces apoptosis in pancreatic carcinoma cells in vitro and in vivo. Mol Cancer Ther 1: 989–997, 2002 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Cain RJ, Ridley AJ. Phosphoinositide 3-kinases in cell migration. Biol Cell 101: 13–29, 2009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Calatayud S, Alvarez A, Victor VM. Gastrin: an acid-releasing, proliferative and immunomodulatory peptide? Mini Rev Med Chem 10: 8–19, 2010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Carter H, Samayoa J, Hruban RH, Karchin R. Prioritization of driver mutations in pancreatic cancer-specific high-throughput annotation of somatic mutations (CHASM). Cancer Biol Ther 10: 582–587, 2011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Cayrol C, Bertrand C, Kowalski-Chauvel A, Daulhac L, Cohen-Jonathan-Moyal E, Ferrand A, Seva C. Alpha v integrin: A new gastrin target in human pancreatic cancer cells. World J Gastroenterol 17: 4488–4495, 2011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Cayrol C, Clerc P, Bertrand C, Gigoux V, Portolan G, Fourmy D, Dufresne M, Seva C. Cholecystokinin-2 receptor modulates cell adhesion through beta 1-integrin in human pancreatic cancer cells. Oncogene 25: 4421–4428, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Chao C, Han X, Ives K, Park J, Kolokoltsov AA, Davey RA, Moyer MP, Hellmich MR. CCK2 receptor expression transforms non-tumorigenic human NCM356 colonic epithelial cells into tumor forming cells. Int J Cancer 126: 864–875, 2010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Chau I, Cunningham D, Russell C, Norman AR, Kurzawinski T, Harper P, Harrison P, Middleton G, Daniels F, Hickish T, Prendeville J, Ross PJ, Theis B, Hull R, Walker M, Shankley N, Kalindjian B, Murray G, Gillbanks A, Black J. Gastrazole (JB95008), a novel CCK2/gastrin receptor antagonist, in the treatment of advanced pancreatic cancer: results from two randomised controlled trials. Br J Cancer 94: 1107–1115, 2006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Chen DA, Zhao CM, Al Haider W, Hakanson R, Rehfeld JF, Kopin AS. Differentiation of gastric ECL cells is altered in CCK2 receptor-deficient mice. Gastroenterology 123: 577–585, 2002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Clerc P, Leung-Theung-Long S, Wang TC, Dockray GJ, Bouisson M, Delisle MB, Vaysse N, Pradayrol L, Fourmy D, Dufresne M. Expression of CCK2 receptors in the murine pancreas: proliferation, transdifferentiation of acinar cells, and neoplasia Gastroenterology 122: 428–437, 2002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Colucci R, Blandizzi C, Tanini M, Vassalle C, Breschi MC, Del Tacca M. Gastrin promotes human colon cancer cell growth via CCK-2 receptor-mediated cyclooxygenase-2 induction and prostaglandin E2 production. Br J Pharmacol 144: 338–348, 2005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Dan HC, Sun M, Kaneko S, Feldman RI, Nicosia SV, Wang HG, Tsang BK, Cheng JQ. Akt phosphorylation and stabilization of X-linked inhibitor of apoptosis protein (XIAP). J Biol Chem 279: 5405–5412, 2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Deveraux QL, Roy N, Stennicke HR, Van Arsdale T, Zhou Q, Srinivasula SM, Alnemri ES, Salvesen GS, Reed JC. IAPs block apoptotic events induced by caspase-8 and cytochrome c by direct inhibition of distinct caspases. EMBO J 17: 2215–2223, 1998 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Deveraux QL, Takahashi R, Salvesen GS, Reed JC. X-linked IAP is a direct inhibitor of cell-death proteases. Nature 388: 300–304, 1997 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Dorsam RT, Gutkind JS. G-protein-coupled receptors and cancer. Nat Rev Cancer 7: 79–94, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Dufresne M, Seva C, Fourmy D. Cholecystokinin and gastrin receptors. Physiol Rev 86: 805–847, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Ferrand A, Kowalski-Chauvel A, Bertrand C, Pradayrol L, Fourmy D, Dufresne M, Seva C. Involvement of JAK2 upstream of the PI 3-kinase in cell-cell adhesion regulation by gastrin. Exp Cell Res 301: 128–138, 2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Harris JC, Clarke PA, Awan A, Jankowski J, Watson SA. An antiapoptotic role for gastrin and the gastrin/CCK-2 receptor in Barrett's esophagus. Cancer Res 64: 1915–1919, 2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Jin G, Ramanathan V, Quante M, Baik GH, Yang X, Wang SS, Tu S, Gordon SA, Pritchard DM, Varro A, Shulkes A, Wang TC. Inactivating cholecystokinin-2 receptor inhibits progastrin-dependent colonic crypt fission, proliferation, and colorectal cancer in mice. J Clin Invest 119: 2691–2701, 2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Konturek PC, Kania J, Kukharsky V, Ocker S, Hahn EG, Konturek SJ. Influence of gastrin on the expression of cyclooxygenase-2, hepatocyte growth factor and apoptosis-related proteins in gastric epithelial cells. J Physiol Pharmacol 54: 17–32, 2003 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Korc M. Driver mutations: a roadmap for getting close and personal in pancreatic cancer. Cancer Biol Ther 10: 588–591, 2010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Langhans N, Rindi G, Chiu M, Rehfeld JF, Ardman B, Beinborn M, Kopin AS. Abnormal gastric histology and decreased acid production in cholecystokinin-B/gastrin receptor-deficient mice. Gastroenterology 112: 280–286, 1997 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Lopes RB, Gangeswaran R, McNeish IA, Wang Y, Lemoine NR. Expression of the IAP protein family is dysregulated in pancreatic cancer cells and is important for resistance to chemotherapy. Int J Cancer 120: 2344–2352, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Macdonald JS, Mccoy S, Whitehead RP, Iqbal S, Wade JL, Giguere JK, Abbruzzese JL. A phase II study of farnesyl transferase inhibitor R115777 in pancreatic cancer: a Southwest oncology group (SWOG 9924) study. Invest New Drugs 23: 485–487, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Matters GL, Harms JF, McGovern CO, Jayakumar C, Crepin K, Smith ZP, Nelson MC, Stock H, Fenn CW, Kaiser J, Kester M, Smith JP. Growth of human pancreatic cancer is inhibited by down-regulation of gastrin gene expression. Pancreas 38: e151–e161, 2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Matters GL, McGovern C, Harms JF, Markovic K, Anson K, Jayakumar C, Martenis M, Awad C, Smith JP. Role of endogenous cholecystokinin on growth of human pancreatic cancer. Int J Oncol 38: 593–601, 2011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. McGregor DB, Jones RD, Karlin DA, Romsdahl MM. Trophic effects of gastrin on colorectal neoplasms in the rat. Ann Surg 195: 219–223, 1982 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Meyer T, Caplin ME, Palmer DH, Valle JW, Larvin M, Waters JS, Coxon F, Borbath I, Peeters M, Nagano E, Kato H. A phase Ib/IIa trial to evaluate the CCK2 receptor antagonist Z-360 in combination with gemcitabine in patients with advanced pancreatic cancer. Eur J Cancer 46: 526–533, 2010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Pradeep A, Sharma C, Sathyanarayana P, Albanese C, Fleming JV, Wang TC, Wolfe MM, Baker KM, Pestell RG, Rana B. Gastrin-mediated activation of cyclin D1 transcription involves beta-catenin and CREB pathways in gastric cancer cells. Oncogene 23: 3689–3699, 2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Preis M, Korc M. Kinase signaling pathways as targets for intervention in pancreatic cancer. Cancer Biol Ther 9: 754–763, 2010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Ramamoorthy S, Stepan V, Todisco A. Intracellular mechanisms mediating the anti-apoptotic action of gastrin. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 323: 44–48, 2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Richards DA, Kuefler PR, Becerra C, Wilfong LS, Gersh RH, Boehm KA, Zhan F, Asmar L, Myrand SP, Hozak RR, Zhao LP, Gill JF, Mullaney BP, Obasaju CK, Nicol SJ. Gemcitabine plus enzastaurin or single-agent gemcitabine in locally advanced or metastatic pancreatic cancer: results of a Phase II, randomized, noncomparative study. Invest New Drugs 29: 144–153, 2011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Rozengurt E, Sinnett-Smith J, Kisfalvi K. Crosstalk between insulin/insulin-like growth factor-1 receptors and G protein-coupled receptor signaling systems: a novel target for the antidiabetic drug metformin in pancreatic cancer. Clin Cancer Res 16: 2505–2511, 2010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Sarkar S, Swiercz R, Kantara C, Hajjar KA, Singh P. Annexin A2 mediates up-regulation of NF-kappaB, beta-catenin, and stem cell in response to progastrin in mice and HEK-293 cells. Gastroenterology 140: 583–595, 2011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Satoh K, Kaneko K, Hirota M, Masamune A, Satoh A, Shimosegawa T. Expression of survivin is correlated with cancer cell apoptosis and is involved in the development of human pancreatic duct cell tumors. Cancer 92: 271–278, 2001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Singh P, Velasco M, Given R, Wargovich M, Varro A, Wang TC. Mice overexpressing progastrin are predisposed for developing aberrant colonic crypt foci in response to AOM. Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol 278: G390–G399, 2000 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Sirinek KR, Levine BA, Moyer MP. Pentagastrin stimulates in vitro growth of normal and malignant human colon epithelial cells. Am J Surg 149: 35–39, 1985 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Smith JP, Fantaskey AP, Liu G, Zagon IS. Identification of gastrin as a growth peptide in human pancreatic cancer. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol 268: R135–R141, 1995 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Smith JP, Hamory MW, Verderame MF, Zagon IS. Quantitative analysis of gastrin mRNA and peptide in normal and cancerous human pancreas. Int J Mol Med 2: 309–315, 1998 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Smith JP, Liu G, Soundararajan V, McLaughlin PJ, Zagon IS. Identification and characterization of CCK-B/gastrin receptors in human pancreatic cancer cell lines. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol 266: R277–R283, 1994 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Smith JP, Rickabaugh CA, McLaughlin PJ, Zagon IS. Cholecystokinin receptors and PANC-1 human pancreatic cancer cells. Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol 265: G149–G155, 1993 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Smith JP, Shih A, Wu Y, McLaughlin PJ, Zagon IS. Gastrin regulates growth of human pancreatic cancer in a tonic and autocrine fashion. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol 270: R1078–R1084, 1996 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Smith JP, Shih AH, Wotring MG, McLaughlin PJ, Zagon IS. Characterization of CCK-B/gastrin-like receptors in human gastric carcinoma. Int J Oncol 12: 411–419, 1998 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Smith JP, Stock EA, Wotring MG, McLaughlin PJ, Zagon IS. Characterization of the CCK-B/gastrin-like receptor in human colon cancer. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol 271: R797–R805, 1996 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Todisco A, Ramamoorthy S, Witham T, Pausawasdi N, Srinivasan S, Dickinson CJ, Askari FK, Krametter D. Molecular mechanisms for the antiapoptotic action of gastrin. Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol 280: G298–G307, 2001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Watson S, Durrant L, Morris D. Gastrin: growth enhancing effects on human gastric and colonic tumor cells. Br J Cancer 59: 554–558, 1989 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Weinberg DS, Ruggeri B, Barber MT, Biswas S, Miknyocki S, Waldman SA. Cholecystokinin A and B receptors are differentially expressed in normal pancreas and pancreatic adenocarcinoma. J Clin Invest 100: 597–603, 1997 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Winsett OE, Townsend CM, Jr, Glass EJ, Thompson JC. Gastrin stimulates growth of colon cancer. Surgery 99: 302–307, 1986 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Young SH, Rozengurt E. Crosstalk between insulin receptor and G protein-coupled receptor signaling systems leads to Ca(2+) oscillations in pancreatic cancer PANC-1 cells. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 401: 154–158, 2010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Zhou JJ, Chen ML, Zhang QZ, Zao Y, Xie Y. Blocking gastrin and CCK-B autocrine loop affects cell proliferation and apoptosis in vitro. Mol Cell Biochem 343: 133–141, 2010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Zhukova E, Sinnett-Smith J, Wong H, Chiu T, Rozengurt E. CCK(B)/gastrin receptor mediates synergistic stimulation of DNA synthesis and cyclin D1, D3, and E expression in Swiss 3T3 cells. J Cell Physiol 189: 291–305, 2001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]