Abstract

We used breath-holding during inspiration as a model to study the effect of pulmonary stretch on sympathetic nerve activity. Twelve healthy subjects (7 females, 5 males; 19–27 yrs) were tested while they performed an inspiratory breath-hold, both supine and during a 60° head-up tilt (HUT 60). Heart rate (HR), mean arterial blood pressure (MAP), respiration, muscle sympathetic nerve activity (MSNA), oxygen saturation (SaO2) and end tidal carbon dioxide (ETCO2) were recorded. Cardiac output (CO) and total peripheral resistance (TPR) were calculated. While breath-holding, ETCO2 increased significantly from 41±2 to 60±2 Torr during supine (p<0.05) and 38±2 Torr to 58±2 during HUT60 (p<0.05); SaO2 decreased from 98±1.5% to 95±1.4% supine, and from 97±1.5% to 94±1.7% during HUT60 (p=NS). MSNA showed three distinctive phases - a quiescent phase due to pulmonary stretch associated with decreased MAP, HR, CO and TPR; a second phase of baroreflex-mediated elevated MSNA which was associated with recovery of MAP and HR only during HUT60; CO and peripheral resistance returned to baseline while supine and HUT60; a third phase of further increased MSNA activity related to hypercapnia and associated with increased TPR. Breath-holding results in initial reductions of MSNA, MAP and HR by the pulmonary stretch reflex followed by increased sympathetic activity related to the arterial baroreflex and chemoreflex.

Keywords: Breath-holding, orthostatic stress, muscle sympathetic nerve activity, baroreflex, chemoreflex

Introduction

Inspiratory breath-holding is observed in disordered sleep and obstructive sleep apnea leading to increased blood pressure (BP), and heart rate (HR) [1–3]. Hemodynamic perturbations also occur during voluntary breath-holds related to central blood volume changes, vagal afferent nerve stimulation and alterations in sympathetic nervous system activity [18,24,34]. Results of studies of breath-holding have been controversial: while initial vasodilation is a common finding, heart rate changes have been variable, reporting both bradycardia and tachycardia [1,4,18,35,44] possibly related to uncertainty about glottis closure and performance of a Valsalva maneuver during breath-holding.

Prolonged inspirations also occur during upright posture and contribute to simple faint [39]. While orthostasis increases sympathoexcitation and produces vagal withdrawal [29,39,43], the effects of upright posture on the cardiovascular response to breath-holding are unknown.

Therefore, we studied breath-holding in supine and upright positions To determine effects on BP, HR, cardiac output (CO), total peripheral resistance (TPR), end tidal carbon dioxide (ETCO2) and muscle sympathetic nerve activity (MSNA) in healthy volunteer subjects We hypothesized that upright posture could augment the initial hypotension of breath-holding while decreasing heart rate compared to supine because of time-dependent changes in sympathetic nerve activity related to sequential activation of the pulmonary stretch reflex, the arterial baroreflex, and chemoreflexes.

Methods

Subjects

Twelve healthy non-smoking normotensive subjects (7 females, 5 males; 19–27 yrs) participated in the study. The study was approved by the committee for the protection of human subjects (Institutional Review Board) of New York Medical College. Informed consent was obtained from all participants.

Subjects were recruited and were screened for health status. They were excluded if they had any history of respiratory ailment or if they were taking any cardioactive or neuroactive medications. Subjects refrained from beverages containing xanthine and caffeine for at least 72 hours before testing. There were no trained competitive athletes or bedridden subjects.

Protocol

Tests began after an overnight fast. After a 30-min acclimatization period, we assessed HR, BP, respiration, oxygensaturation (SaO2), ETCO2, and MSNA during a supine baseline period. We used impedance plethysmography (IP) to continuously measure changes in thoracic blood flow as an estimate of CO [40].

After baseline data were collected, subjects first breathed rhythmically along with a metronome at a rate of 12 breaths per minute and then performed as large an inspiratory breath-hold as possible for as long as they could. In order to avoid performing a Valsalva maneuver, subjects were trained to maintain an open glottis by panting while maintaining inspiration[19]. BP, HR, MSNA, and IP were recorded continuously. After 10 minutes of rest the subjects were tilted to 60° for 10 minutes after which HUT60 control data were collected and subjects repeated the inspiratory breath-hold maneuver.

Phases of Breath-Holding

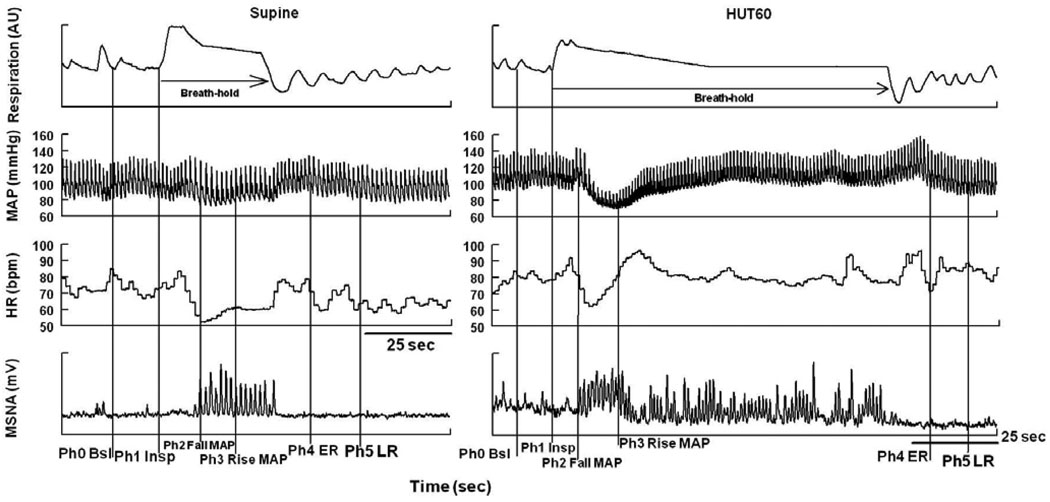

We used changes in respiratory activity and BP, determined during pilot experiments, to define phases of breath-holding both supine and HUT60 (Figure 1). The phases are: Phase 0-Baseline; the 5 min of resting baseline followed by Phase1-Inspiration; the time for deep inspiration. MAP begins to decrease shortly after inspiration is complete and defines the start of Phase2-Fall in MAP. Blood pressure recovery defines the end of Phase 2 and the start of Phase 3-Rise in MAP which initiates a period of blood pressure stability. An increase in MAP begins near the end of the breath-hold defines the start of Phase 4-early recovery (ER), and the beginning of the late recovery (LR) phase is defined by the return of MAP, HR, MSNA and ETCO2 to baseline values.

Figure 1.

Representative tracing of breath-holding during inspiration. Mean Arterial Pressure (MAP), Heart Rate (HR), Muscle Sympathetic Nerve Activity (MSNA), Baseline (Bsl), Inspiration (Insp), Early Recovery (ER), Late Recovery (LR), Phase (Ph). Within the same breath-hold, there is decrease in MAP followed by an increase in MAP, HR, and MSNA. The phases are as follows: Phase 0-Baseline; the 5 min of resting baseline followed by Phase1-Inspiration; the time for deep inspiration. MAP begins to decrease shortly after inspiration is complete defining the start of Phase2-Fall in MAP. Blood pressure recovery defines the end of Phase 2 and the start of Phase 3-Rise in MAP which initiates a period of blood pressure stability. An increase in MAP begins near the end of the breath-hold defines the start of Phase 4-early recovery (ER), and the beginning of the Phase 5-late recovery (LR) phase is defined by the return of MAP, HR, MSNA and ETCO2 to baseline values.

HR and MAP monitoring

A single ECG lead was recorded for rhythm. Upper extremity BP was continuously monitored with a finger arterial plethysmograph (Finometer, FMS, Amsterdam NE) placed on the right middle finger. A height sensor was placed at heart level. ECG and Finometer data were interfaced to a personal computer through an A/D converter (DI-720 DataQ Ind., Milwaukee, WI).

ETCO2 and SaO2 monitoring

ETCO2 was measured continuously through nasal prongs connected to a capnograph. SaO2 was measured by pulse oximetry placed on the right earlobe. ETCO2 was recorded after the last breath exhaled before breath-holding and after the first breath exhaled once breath-holding ended.

Muscle sympathetic nerve activity

Multiunit recordings of efferent postganglionic MSNA were obtained using the technique of Vallabo [41]. A unipolar tungsten microelectrode (uninsulated tip diameter 1 to 5 µm, shaft diameter 200 µm; Frederick Haer & Co., Bowdoinham ME) was inserted into the muscle nerve fascicles of the peroneal nerve posterior to the fibular head and a reference electrode was placed subcutaneously 2–3 cm from the recording electrode. Nerve activity was amplified with a total gain of 100,000, band pass filtered (0.7 to 2 kHz), and integrated using an amplifier (Model 662C-4, Biomedical Engineering Department; University of Iowa, Iowa City). After acquiring a stable recording site, resting MSNA was recorded using the integrated MSNA bursts. During HUT60, subjects were instructed to stand on the leg which was not used to record MSNA.

Changes in Blood Flow and peripheral resistance

A four-channel tetrapolar digital high-resolution impedance plethysmograph (THRIM, UFI, Morro Bay, Ca) was used to measure changes in CO. We have used these methods previously to estimate CO and regional blood flow [40]. TPR was calculated as mean arterial pressure MAP (mmHg)/ CO (L/min).

HUT-table testing

An electrically driven tilt table with a footboard was used for HUT60 (Colin Medical, San Antonio, TX). After supine measurements, the table was tilted up to 60° and maintained for 10 min. Following this the table was returned to the supine position and data was recorded until parameters returned to baseline.

Statistical analysis

Data were digitized at 200 Hz, stored in a computer and analyzed off-line with custom software. MSNA data were analyzed using wavelets for noise reduction: We used Mallat’s dyadic pyramid algorithm formulation of the fast discrete wavelet transform (DWT) [20,21] to obtain a multiresolution analysis. We used the Dabauchies least asymmetric 8 mother wavelet function [5] and an extended version of the DWT to produce a “maximal overlap discrete wavelet transformation” (MODWT) [27]. We normalized sympathetic bursts as follows: the largest burst occurring during the initial control period was assigned a height value (peak to trough) of 100 and all other bursts were normalized against this standard. Bursts during baseline and bursts during breath-holding were estimated as burst frequency (bursts/min) and total MSNA activity (bursts/min*mean burst area). For analysis, muscle sympathetic bursts were advanced temporally by 1.3 s to compensate for nerve conduction delays [7,33]. Time series were analyzed by repeated measures ANOVA. using SPSS version 14.0 and graphed using GraphPad prism software version 4. Tabular and graphic results are reported as means ± SE.

Results

All subjects completed every aspect of study, without fainting or presyncopal symptoms. Supine baseline findings are shown in Table 1. Figure 1 shows changes due to breath-holding during supine and HUT60 in a representative subject.

Table 1.

Resting demographic profile of subjects

| Parameter | Mean±SE |

|---|---|

| Age (years) | 24.4±0.9 |

| Height (cm) | 165.0±1.4 |

| Weight (Kg) | 62.0±2.2 |

| BMI (Kg/m^2) | 22.6±0.5 |

| BSA (m^2) | 1.68±0.0 |

| Resting SBP (mmHg) | 116.2±5.0 |

| Resting DBP (mmHg) | 75.1±3.2 |

| Resting MAP (mmHg) | 88.8±3.6 |

| Resting HR (bpm) | 66.0±2.5 |

| Resting MSNA activity(bursts/min) | 18±3 |

| Resting MSNA activity(bursts/min*mean burst area expressed as au/min) |

418±15 |

| Resting ETCO2 (Torr) | 41.1±2.2 |

Body mass index (BMI); body surface area (BSA); systolic blood pressure (SBP); diastolic blood pressure (DBP); mean arterial pressure (MAP); muscle sympathetic nerve activity (MSNA); end tidal carbon dioxide (ETCO2).

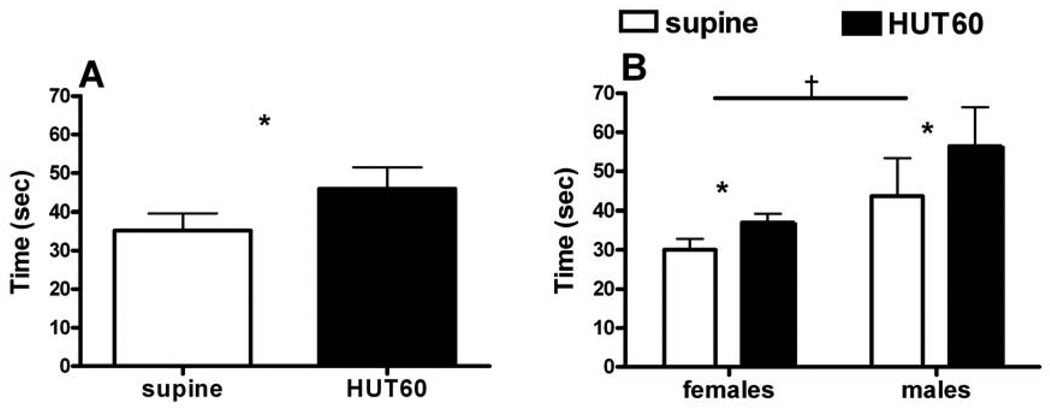

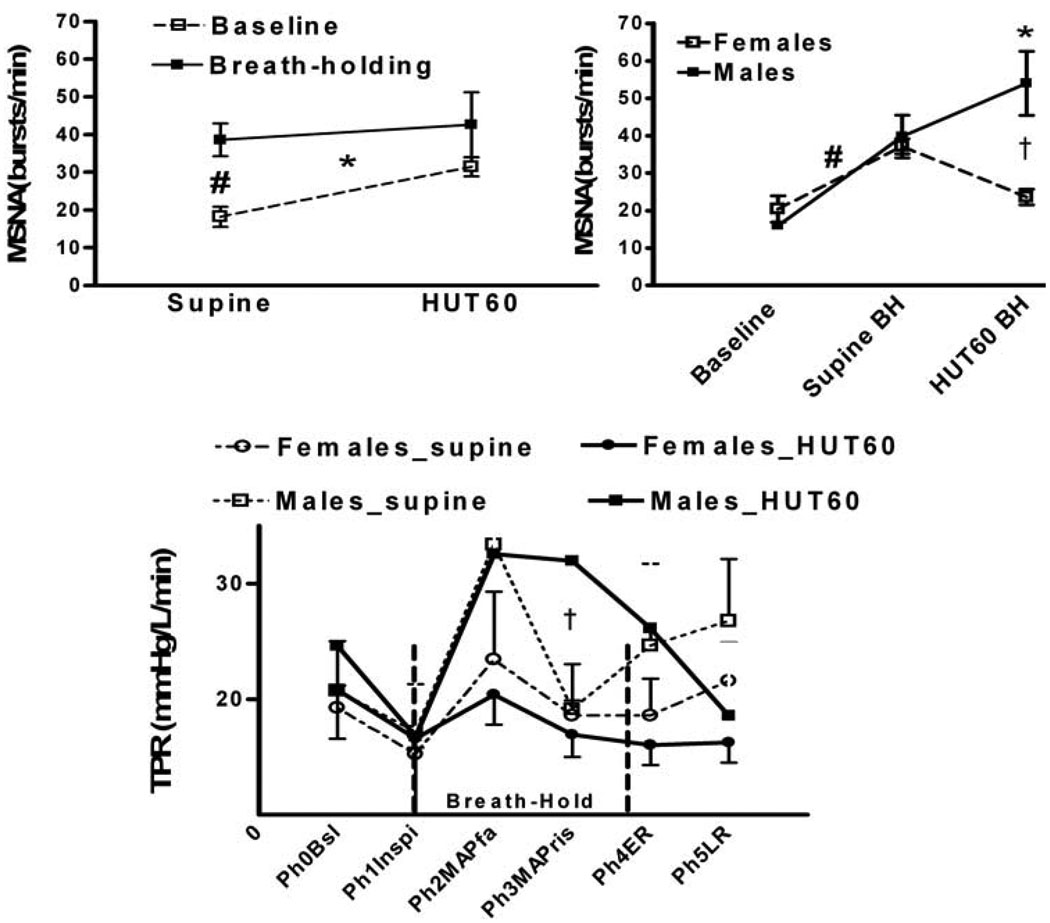

During HUT60, SBP, and HR increased (p<0.05), while CO decreased (p<0.05). As shown in Figure 2, inspiratory breath-holding time increased during HUT60 (p<0.05); males could hold their breath for longer times than females (p<0.05). As shown in Figure 3, breath-holding resulted in an increase in MSNA frequency and TPR in supine and HUT60 positions (p<0.05). Males had higher sympathetic activation and TPR than females during HUT60 breath-holding (p<0.05).

Figure 2.

Breath-holding time during inspiration in supine and HUT60 positions. The HUT60 position increases Breath-holding time. Left panel (Figure 2A) shows combined males and females data; Right panel (Figure 2B) shows gender differences in breath-holding time. Males have a higher breath-holding time than females. Data is expressed as Means±SE.

*, p<0.05, supine vs. HUT60; †, males vs. females.

Figure 3.

Posture-related gender differences in response to breath-holding. Left upper panel shows that breath-holding increases muscle sympathetic nerve activity (MSNA) in supine and HUT60. Right upper panel shows that breath-holding induced increase in MSNA frequency during HUT60 is much higher in males than in females. Lower panel shows males have higher total peripheral resistance than females during supine and HUT 60 breath-holding. Muscle sympathetic nerve activity (MSNA), head uptilt at 60° (HUT60), Breath-holding (BH), Phase (Ph); Baseline (Bsl); Inspiration (Inspi) ; MAP fall (MAPfa); MAP rise (MAPris); Early Recovery (ER); LR, Late Recovery (LR) *, p<0.05 supine vs. HUT60; #, p<0.05 supine-baseline vs. supine-breath-hold; †, p<0.05, males vs. females.

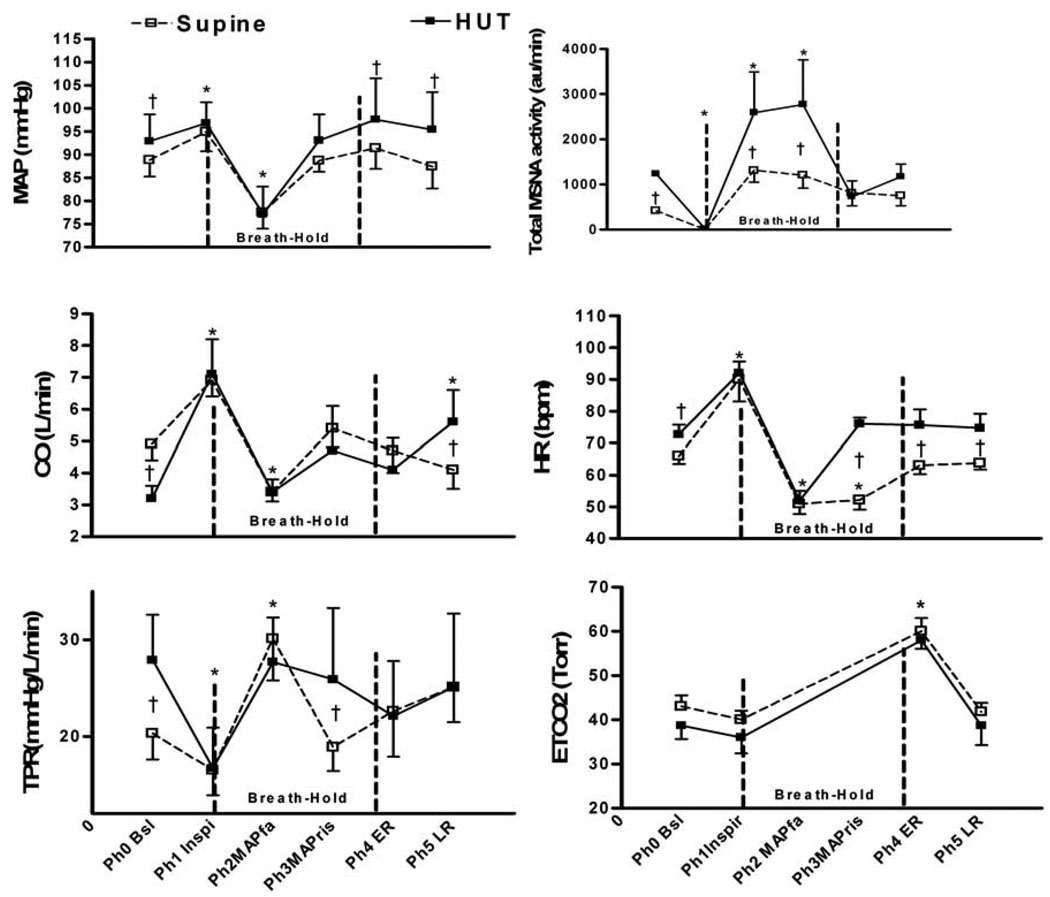

Supine hemodynamic changes that occurred during breath-holding are summarized in Figure 4. During Phase1-Inspiration: SBP, MAP, HR, and CO increased due to the mechanical effects of inspiration (p < 0.05), while MSNA and TPR decrease (p<0.05); Phase 2-Fall in MAP: SBP, DBP, MAP, HR, and CO decreased (p < 0.05), while TPR and MSNA increased. Phase 3-Rise in MAP: SBP, DBP, MAP increased, HR remained decreased, MSNA increased (p< 0.05). Also, compared to Phase 2, MSNA increased and TPR decreased in Phase 3 (p<0.05); Phase 4- Early recovery: ETCO2 was increased (p<0.05). SaO2 decreased from 98±1.5% to 95±1.4%. MSNA decreased (p<0.05) as compared to Phase 3; Phase 5 – Late recovery: Hemodynamic parameters returned towards baseline.

Figure 4.

Comparison of supine and HUT60 breath-holding in inspiration. Values are expressed as Mean±SE for mean arterial pressure (MAP); cardiac output (CO); total peripheral resistance (TPR); total muscle sympathetic nerve (MSNA) activity (bursts/min*mean burst area); heart rate (HR); and end tidal carbon dioxide (ETCO2); Phase (Ph); Baseline (Bsl); Inspiration (Inspi) ; MAP fall (MAPfa); MAP rise (MAPris); Early Recovery (ER); LR, Late Recovery (LR) *,p<0.05 vs. Baseline; †, p<0.05 Supine vs. HUT60.

Upright (HUT60) hemodynamic changes that occurred during breath-holding are also summarized in Figure 4. During Phase 0 – Baseline: MAP, HR, MSNA, and TPR increased, while CO decreased (p<0.05); Phase1-Inspiration: HR and CO increased (p<0.05), MSNA and TPR decreased (p<0.05). There were no differences between the supine and HUT60 values for any of these parameters; Phase 2-Fall in MAP: SBP, DBP, MAP, HR and CO decreased (p<0.05), and MSNA and TPR increased (p<0.05). As compared to supine position, MSNA was significantly greater (p<0.05); Phase 3-Rise in MAP: SBP, DBP, MSNA, and CO started increasing back towards baseline. Compared to the supine position, MAP and CO were not changed, while HR, TPR, and MSNA were increased (p<0.05); Phase 4- Early Recovery: SBP, DBP, MAP, HR, CO, and TPR returned to baseline. ETCO2 was increased (p<0.05). SaO2 decreased from 97 ±1.5 % to 94±1.7%. MSNA decreased (p<0.05). Phase 5 – Late Recovery: Parameters remained at baseline.

Discussion

Postural change during the prolonged inspiratory breath results in phasic changes in HR, MAP, MSNA, CO, and TPR. Initial inspiration (Phase 1), mechanically increases right atrial filling via reduced intrapleural pressure causing a small and brief increase in MAP and HR. Phase 1 is immediately followed by activation of pulmonary C-fiber afferents suppressing sympathetic activity via the pulmonary stretch reflex [18,37]. Temporally, the reflex produces bradycardia mediated by myelinated vagal efferents and later, after a lag of seconds, reductions in MAP and TPR mediated by unmyelinated sympathetic efferents [14,28,34]. MSNA silence is closely timed with the precipitous fall in HR. Bradycardia [18,30], sympathetic inhibition [24,38] and hypotension [4] have been observed during breath-holding. The decrease in MAP during Phase2 unloads the arterial baroreflex [24] which increases sympathetic activity. The unloading of the baroreceptors results in a pressor and cardiac accelerator response in the upright position but only a pressor response while supine. This difference may be due to the competitive effects of pulmonary stretch and baroreflexes. During HUT60, the increased baroreflex sensitivity and unloading predominates and both MAP and HR are restored to baseline. When supine MAP is restored by the baroreflex and HR remains decreased. This may result from vagal predominance of the pulmonary stretch reflex. Such seemingly paradoxical bradycardia has been previously demonstrated during sustained positive airway pressure [11].

The change of posture from supine to HUT60 causes a gravity-induced shift of fluid, resulting in a decrease in venous return and CO via parasympathetic withdrawal and sympathetic activation [39]. Arterial and cardiopulmonary baroreflex unloading causes an increase in TPR as we observed in an earlier study [40]. The intensity of sympathetic is much larger upright due to the combined effects of increased sympathetic baroreflex sensitivity and increased baroreflex unloading by gravity [26].

There are several potential additional causes of the observed increase in sympathetic activity during Phase 3 when upright. It is possible that larger negative intra-thoracic pressures during HUT60 preferentially affects aortic baroreceptors [18,19] more than carotid baroreceptors enhancing sympathetic activity [17]. Also, cardiopulmonary baroreceptors may play an enhanced role due to cardiac emptying during orthostasis [4]. Hormones such as angiotensin-II, norepinephrine, and epinephrine, may also potentiate physiological changes due breath-holding causing excessive sympathetic activation (>3 times more than supine position).

Hypercapnia can contribute to the increase in sympathetic activation during Phase 3 suggesting activation of chemoreflex during breath-holding. The reduction of MSNA coincides with the eucapnia which rapidly follows the end of inspiration in Phase 4. Increased ETCO2 levels develop during breath-hold because CO2 is continuously being produced and cannot diffuse out of the lungs. Since ETCO2= K * metabolic carbon dioxide production/ alveolar ventilation [42], provided that metabolic carbon dioxide production is constant, alveolar ventilation is inversely proportional to the ETCO2. We observed an increase of approximately 20 Torr in ETCO2 during breath-holding in both the supine and HUT60 position. This increase causes a break point for breathing sooner while supine than HUT60 because of a larger gas exchange area when upright [22,42]. Our results of postural change in breath-hold duration are different than that of Sebert [35], who found that subjects could hold their breath longer while supine compared to upright position. Sebert used sitting while we used upright tilt as the postural maneuver. The increase in CO2 is consistent with the previously estimated time lag of ~20 s from the beginning of accumulation of CO2 to the acidification of the medullary chemoreceptor [10]. CO2-mediated chemoreflex stimulation towards the end of Phase 3 leads to further sympathetic stimulation and hypercapnia, which acts to terminate the breath-hold. Peripheral chemoreflex stimulation may also contribute to breath-holding induced CO2-mediated sympathetic activation [23]. Chemoreflex stimulation, therefore, leads to a pressor response and further sympathetic activation. Training [7, 31] and increasing age [39] affects this break point. Shortened time to break point may be due to the effect of age and training in our subjects.

Sex differences in our study were similar to those of Sebert who found that females exhibited shorter breath-holding time than males[35]. In addition, we have observed that during breath-holding males increase their MSNA burst frequency in both supine and upright position, while females have an increase only while supine. Females may be more sensitive to orthostatic stress resulting in a successive decrease in vasoconstrictor activity. Our findings that females have a higher orthostatic intolerance are similar to those of others [13] who found that following a sympathetic stimuli 1) there is a direct linear increase in vascular resistance and sympathetic activity only in males and not in females 2) increase in vascular resistance were lower in females compared to males. However, Fu et al. did not find any gender differences in sympathetic activity and vascular resistance during orthostasis [8,9].

During the end of Phase 3 supine breath-hold, we observed an uncoupling between sympathetic activity and TPR. Similar reduced TPR during the later supine breath-holding was reported by Huesser et al. [12] and is likely due to attenuation of sympathetic vasoconstriction by direct vasodilatory effects of hypoxia-hypercapnia [16,31], and from impeded vasoconstrictor transduction induced by hypercapnia [36].

The release of breath-hold during Phase 4 while supine reduces the mechanical constraint of negative intrathoracic pressure. MAP, HR, CO and TPR recover to resting baseline levels. There is an overshoot of SBP and DBP above baseline while upright, similar to the overshoot observed during Phase IV of the Valsalva maneuver. This may be due to residual vasoconstriction and restoration of venous return and CO [6,25].

There are several limitations to our study. First, we used pulse oximetry as an estimate of oxygen saturation and capnography to estimate blood CO2 concentrations instead of arterial blood gas analysis. Thus, CO2 was only measured at the end of the breath-hold. However, we were most interested in CO2 findings at this time. Second we did not measure the changes in intrathoracic pressure during breath-holding. This could have provided further information concerning the physiology of breath-hold and would have insured that the Valsalva maneuver did not occur. However, while changes in initial MAP and HR resembled those of the Valsalva maneuver because in both cases inspiratory cardiac filling occurs, the subsequent and marked decrease in HR during open glottis inspiration is directionally opposite to the increase in HR consistently observed during the Valsalva maneuver. Third, we did not directly measure stretch reflex and baroreflex activities. This is most difficult in humans. However, pulmonary stretch and reflexive effects are clearly induced and are consistent with descriptions of the C-fiber mediated pulmonary stretch reflexes and are quite different from, for example, the Hering-Breuer reflex that prevents over-distention of full lungs [15].

In conclusion, inspiration sequentially activates pulmonary stretch depressor and vagotonic reflexes, unloads the baroreflexes producing sympathoexcitation, vagolysis and cardio-acceleration. Breath-holding also evokes chemoreflex-mediated sympathetic activation. Bradycardia occurs throughout a much shorter supine breath-hold compared to a much longer breath-hold during HUT60 associated with tachycardia. Postural changes highlight the different homeostatic mechanisms that serve to affect HR, MAP, CO and TPR. Diseases or conditions leading to partial or complete loss of baroreflex may predispose an individual to fainting while breath-holding.

Acknowledgement

Supported by 0735603T American Heart Association, 1RO1HL66007 and 1R01HL074873 from the National Heart Lung and Blood Institute of the National Institutes of Health.

Footnotes

Disclosures: The authors have nothing to disclose to the CAR Publications Office concerning any potential conflict of interest (e.g., consultancies, stock ownership, equity interests, patent-licensing arrangements, lack of access to data, or lack of control of the decision to publish).

Reference List

- 1.Sleep-related breathing disorders in adults: recommendations for syndrome definition and measurement techniques in clinical research. The Report of an American Academy of Sleep Medicine Task Force. Sleep. 1999:667–689. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bhadriraju S, Kemp CR, Jr, Cheruvu M, Bhadriraju S. Sleep apnea syndrome: implications on cardiovascular diseases. Crit Pathw. Cardiol. 2008:248–253. doi: 10.1097/HPC.0b013e31818ae644. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bradley TD, Floras JS. Obstructive sleep apnoea and its cardiovascular consequences. Lancet. 2009:82–93. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(08)61622-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Daly DM. Interactions between respiration and circulation. In: Cherniack NS, Widdicombe JG, editors. Handbook of physiology: the respiratory system. vol 2. Bethesda, MD: American Physiological Society; 1986. pp. 529–594. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Daubechies I. Orthonormal bases of compactly supported wavelets. Comm Pure Appl Math. 2006:909–996. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Denq JC, O'Brien PC, Low PA. Normative data on phases of the Valsalva maneuver. J Clin Neurophysiol. 1998:535–540. doi: 10.1097/00004691-199811000-00013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Fagius J, Wallin BG. Sympathetic reflex latencies and conduction velocities in normal man. J Neurol. Sci. 1980:433–448. doi: 10.1016/0022-510x(80)90098-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Fu Q, Okazaki K, Shibata S, Shook RP, VanGunday TB, Galbreath MM, Reelick MF, Levine BD. Menstrual cycle effects on sympathetic neural responses to upright tilt. J Physiol. 2009:2019–2031. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2008.168468. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Fu Q, Witkowski S, Levine BD. Vasoconstrictor reserve and sympathetic neural control of orthostasis. Circulation. 2004:2931–2937. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.0000146384.91715.B5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Gardner WN. The pattern of breathing following step changes of alveolar partial pressures of carbon dioxide and oxygen in man. J Physiol. 1980:55–73. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1980.sp013151. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hayashi KD. Responses of systemic arterial pressure and heart rate to increased intrapulmonary pressure in anesthetized dogs. Proc. Soc. Exp. Biol. Med. 1969:426–429. doi: 10.3181/00379727-131-33893. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Heusser K, Dzamonja G, Tank J, Palada I, Valic Z, Bakovic D, Obad A, Ivancev V, Breskovic T, Diedrich A, Joyner MJ, Luft FC, Jordan J, Dujic Z. Cardiovascular regulation during apnea in elite divers. Hypertension. 2009:719–724. doi: 10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.108.127530. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hogarth AJ, Mackintosh AF, Mary DA. Gender-related differences in the sympathetic vasoconstrictor drive of normal subjects. Clin Sci (Lond) 2007:353–361. doi: 10.1042/CS20060288. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Jiang C, Lipski J. Synaptic inputs to medullary respiratory neurons from superior laryngeal afferents in the cat. Brain Res. 1992:197–206. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(92)90895-g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kaufman MP, Iwamoto GA, Ashton JH, Cassidy SS. Responses to inflation of vagal afferents with endings in the lung of dogs. Circ. Res. 1982:525–531. doi: 10.1161/01.res.51.4.525. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lahana A, Costantopoulos S, Nakos G. The local component of the acute cardiovascular response to simulated apneas in brain-dead humans. Chest. 2005:634–639. doi: 10.1378/chest.128.2.634. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lenard Z, Studinger P, Kovats Z, Reneman R, Kollai M. Comparison of aortic arch and carotid sinus distensibility in humans--relation to baroreflex sensitivity. Auton. Neurosci. 2001:92–99. doi: 10.1016/S1566-0702(01)00309-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Looga R. Reflex cardiovascular responses to lung inflation: a review. Respir. Physiol. 1997:95–106. doi: 10.1016/s0034-5687(97)00049-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Macefield VG. Sustained activation of muscle sympathetic outflow during static lung inflation depends on a high intrathoracic pressure. J Auton. Nerv. Syst. 1998:135–139. doi: 10.1016/s0165-1838(97)00129-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Mallat SG. Multiresolution approximations and wavelet orthonormal bases of L2(R) Trans Am Math Soc. 1989:69–87. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Mallat SG. A theory for multiresolution signal decomposition: the waveletrepresentation. IEEE Trans Pattern Anal Mach Intell. 1989:674–693. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Miyashita M, Suzuki-Inatomi T, Hirai N. Respiratory control during postural changes in anesthetized cats. J Vestib. Res. 2003:57–64. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Morgan BJ, Crabtree DC, Palta M, Skatrud JB. Combined hypoxia and hypercapnia evokes long-lasting sympathetic activation in humans. J Appl Physiol. 1995:205–213. doi: 10.1152/jappl.1995.79.1.205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Morgan BJ, Denahan T, Ebert TJ. Neurocirculatory consequences of negative intrathoracic pressure vs. asphyxia during voluntary apnea. J Appl Physiol. 1993:2969–2975. doi: 10.1152/jappl.1993.74.6.2969. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Nishimura RA, Tajik AJ. The Valsalva maneuver and response revisited. Mayo Clin Proc. 1986:211–217. doi: 10.1016/s0025-6196(12)61852-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.O'Leary DD, Kimmerly DS, Cechetto AD, Shoemaker JK. Differential effect of head-up tilt on cardiovagal and sympathetic baroreflex sensitivity in humans. Exp. Physiol. 2003:769–774. doi: 10.1113/eph8802632. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Percival DB, Walden AT. Wavelet Methods for Time Series Analysis. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Pilowsky P, Arnolda L, Chalmers J, Llewellyn-Smith I, Minson J, Miyawaki T, Sun QJ. Respiratory inputs to central cardiovascular neurons. Ann. N. Y. Acad. Sci. 1996:64–70. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.1996.tb26707.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Qingyou Z, Karmane SI, Junbao D. Physiologic neurocirculatory patterns in the head-up tilt test in children with orthostatic intolerance. Pediatr. Int. 2008:195–198. doi: 10.1111/j.1442-200X.2008.02556.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Raper AJ, Richardson DW, Kontos HA, Patterson JL., Jr Circulatory responses to breath holding in man. J Appl Physiol. 1967:201–206. doi: 10.1152/jappl.1967.22.2.201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Richardson DW, Wasserman AJ, Patterson JL., Jr General and regional circulatory responses to change in blood pH and carbon dioxide tension. J Clin Invest. 1961:31–43. doi: 10.1172/JCI104234. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Rowell LB. Human cardiovascular control. New York, NY: Oxford University Press; 1993. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Rudas L, Crossman AA, Morillo CA, Halliwill JR, Tahvanainen KU, Kuusela TA, Eckberg DL. Human sympathetic and vagal baroreflex responses to sequential nitroprusside and phenylephrine. Am. J Physiol. 1999:H1691–H1698. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.1999.276.5.h1691. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Seals DR, Suwarno NO, Dempsey JA. Influence of lung volume on sympathetic nerve discharge in normal humans. Circ. Res. 1990:130–141. doi: 10.1161/01.res.67.1.130. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Sebert P, Sanchez J. Sexual and postural differences in cardioventilatory responses during and after breath holding at rest. Eur J Appl Physiol Occup. Physiol. 1981:209–222. doi: 10.1007/BF00422467. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Simmons GH, Minson CT, Cracowski JL, Halliwill JR. Systemic hypoxia causes cutaneous vasodilation in healthy humans. J Appl Physiol. 2007:608–615. doi: 10.1152/japplphysiol.01443.2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.St Croix CM, Morgan BJ, Wetter TJ, Dempsey JA. Fatiguing inspiratory muscle work causes reflex sympathetic activation in humans. J Physiol. 2000:493–504. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7793.2000.00493.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Steinback CD, O'Leary DD, Bakker J, Cechetto AD, Ladak HM, Shoemaker JK. Carotid distensibility, baroreflex sensitivity, and orthostatic stress. J Appl Physiol. 2005:64–70. doi: 10.1152/japplphysiol.01248.2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Taneja I, Medow MS, Glover JL, Raghunath NK, Stewart JM. Increased vasoconstriction predisposes to hyperpnea and postural faint. Am. J Physiol Heart Circ. Physiol. 2008:H372–H381. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00101.2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Taneja I, Moran C, Medow MS, Glover JL, Montgomery LD, Stewart JM. Differential effects of lower body negative pressure and upright tilt on splanchnic blood volume. Am. J Physiol Heart Circ. Physiol. 2007:H1420–H1426. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.01096.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Vallbo AB, Hagbarth KE, Torebjork HE, Wallin BG. Somatosensory, proprioceptive, and sympathetic activity in human peripheral nerves. Physiol Rev. 1979:919–957. doi: 10.1152/physrev.1979.59.4.919. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Wagner PD, West JB. Ventilation, Blood Flow, and Gas Exchange. In: Mason RJ, Murray JF, Boaddus VC, Nadel JA, editors. Murray & Nadel's Textbook of Respiratory Medicine. Saunders, PA: Elsiever; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Wyller VB, Barbieri R, Thaulow E, Saul JP. Enhanced vagal withdrawal during mild orthostatic stress in adolescents with chronic fatigue. Ann. Noninvasive. Electrocardiol. 2008:67–73. doi: 10.1111/j.1542-474X.2007.00202.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Zbrozyna AW, Westwood DM. Cardiovascular responses elicited by simulated diving and their habituation in man. Clin Auton. Res. 1992:225–233. doi: 10.1007/BF01819543. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]