Abstract

Mast cells are important cells of the immune system and are recognized as participants in the pathogenesis of atherosclerosis. In this study, we evaluated the role of mast cells on the progression of atherosclerosis and hepatic steatosis using the apolipoprotein E-deficient (ApoE−/−) and ApoE−/−/mast cell-deficient (KitW-sh/W-sh) mouse models maintained on a high-fat diet. The en face analyses of aortas showed a marked reduction in plaque coverage in ApoE−/−/KitW-sh/W-sh compared with ApoE−/− after a 6-mo regimen with no significant change noted after 3 mo. Quantification of intima/media thickness on hematoxylin and eosin-stained histological cross sections of the aortic arch revealed no significant difference between ApoE−/− and ApoE−/−/KitW-sh/W-sh mice. The high-fat regimen did not induce atherosclerosis in either KitW-sh/W-sh or wild-type mice. Mast cells with indications of degranulation were seen only in the aortic walls and heart of ApoE−/− mice. Compared with ApoE−/− mice, the serum levels of total cholesterol, low-density lipoprotein and high-density lipoprotein were decreased by 50% in ApoE−/−/KitW-sh/W-sh mice, whereas no appreciable differences were noted in serum levels of triglycerides or very low density lipoprotein. ApoE−/−/KitW-sh/W-sh mice developed significantly less hepatic steatosis than ApoE−/− mice after the 3-mo regimen. The analysis of Th1/Th2/Th17 cytokine profile in the sera revealed significant reduction of interleukin (IL)-6 and IL-10 in ApoE−/−/KitW-sh/W-sh mice compared with ApoE−/− mice. The assessment of systemic generation of thromboxane A2 (TXA2) and prostaglandin I2 (PGI2) revealed significant decrease in the production of PGI2 in ApoE−/−/KitW-sh/W-sh mice with no change in TXA2. The decrease in PGI2 production was found to be associated with reduced levels of cyclooxygenase-2 mRNA in the aortic tissues. A significant reduction in T-lymphocytes and macrophages was noted in the atheromas of the ApoE−/−/KitW-sh/W-sh mice. These results demonstrate the direct involvement of mast cells in the progression of atherosclerosis and hepatic steatosis.

Keywords: apolipoprotein E-deficient mouse, apolipoprotein E- mast cell-deficient mouse, mast cells, atherosclerosis, hepatic steatosis

atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease causes the highest incidence of morbidity and mortality in the affluent nations of the world. The pathogenesis of atherosclerosis involves a number of inflammatory responses and is characterized by endothelial cell activation, adhesion molecule expression, leukocyte accumulation, production of cytokines, and changes in the expression of cyclooxygenase-2 (COX-2) (6, 17, 18, 34). Mast cells are normal constituents of the vessel wall and are primarily located in the connective tissue matrices. Increasing evidence suggests an important role for mast cells in vascular inflammation and atherosclerosis (4, 5, 9, 10, 12, 22). The potential involvement of mast cells in atherosclerosis is evident from the increased levels of histamine in the coronary circulation of patients with the disease (35, 40) and the function of mast cell proteases both in the formation of foam cells (25, 28) and calcification of plaques (20, 21).

Mast cells synthesize and secrete many vasoactive substances and inflammatory mediators. These include histamine, proteases (tryptase, chymase, and carboxypeptidase), prostaglandin D2, leukotrienes, heparin, and a variety of cytokines (7, 16, 33, 36, 45). The adventitia of coronary arteries of patients with atherosclerotic plaques contains an increased number of mast cells (10, 12, 20–22). An increase in the number of tissue mast cells is also found to be associated with thrombus formation (10). Mast cell granules have been identified within endothelial cells in vivo (30) and are known to cause proliferation of human microvascular endothelial cells (1). Furthermore, mast cell granule remnants have been shown to bind to low-density lipoproteins (LDL) and enhance their uptake by macrophages, leading to the development of foam cells (25, 28). Both in vivo and in vitro studies have suggested that mast cells have a role in the pathogenesis of atherosclerosis. Apolipoprotein E-null (ApoE−/−) and LDL receptor-null (LDLr−/−) mouse models are used extensively to study the pathobiology of atherosclerosis. Using the LDLr−/− KitW-sh/W-sh mouse model, which lacked both LDLr and mast cells, Sun et al. (39) demonstrated that mast cell deficiency could reduce progression of atherosclerosis, lipid deposition, and recruitment of T-lymphocyte and macrophage into the lesion area. The attenuation of atherosclerosis progression in LDLr−/−/KitW-sh/W-sh was further confirmed by Heikkila et al. (19) who showed a concomitant reduction of inflammation and decrease in soluble intercellular adhesion molecules (19). In a preliminary communication, using the ApoE−/−/KitW-sh/W-sh mouse model, we demonstrated that mast cell deficiency reduces atherosclerosis progression (38). We extended our studies in the ApoE−/− KitW-sh/W-sh mouse model to gain a better understanding of the role of mast cells in atherosclerosis progression. The results presented here demonstrate that mast cell deficiency attenuates the progression of atherosclerosis in ApoE−/− mice maintained on a high-fat diet for 6 mo. The reduction in development of atherosclerotic lesions in ApoE−/−/KitW-sh/W-sh mice was found to be associated with concomitant decreases in hepatic steatosis, serum levels of total cholesterol, LDL, high-density lipoprotein (HDL), and interleukin (IL)-6, and the recruitment of T-lymphocytes and macrophages into the lesion area. In addition, aortic COX-2 gene expression was significantly reduced in ApoE−/−/KitW-sh/-W-sh mice compared with ApoE−/− genotype.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Animals, diets, and specimen collections.

The ApoE−/−/KitW-sh/W-sh mouse model deficient in both ApoE and mast cells was generated by crossing ApoE−/− with KitW-sh/W-sh at the Jackson Laboratories (Bar Harbor, ME) per contract. Eight- to 10-wk-old male mice of both genotypes were fed ad libitum a Western diet (TD.88137, 17.3% protein, 48.5% carbohydrate, 21.2% fat, and 0.2% cholesterol by weight, and 42% kcal from fat; Harlan Teklad, Madison, WI) for 3 or 6 mo. At the beginning and the end of the regimens, 24-h urine samples were collected by placing each mouse in a metabolic cage (Tecniplast, Rochester, NY). Blood samples were collected by bleeding from the retro-orbital sinus under anesthesia, or at the time of necropsy. Mice were killed using isoflurane (Abbott, North Chicago, IL) inhalation followed by exsanguination. The dorsal aorta was perfused in situ first with PBS and then with buffered 10% formalin. The aorta was dissected out and processed for cross-sectional analyses of plaque size in the arch region, or processed for en face analyses. Heart, liver, spleen, and abdominal adipose tissue were weighed. The heart was fixed in 10% formalin and processed to obtain cross sections through the root of the aorta. All animal experiments were approved by the University of Kansas Medical Center's Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee and performed in accordance with the protocol guidelines.

Assessment of atherosclerotic plaques in the aorta.

The extent of coverage of atherosclerotic lesions in the aorta was evaluated using en face preparations as described previously (37). Briefly, after in situ perfusion with cold PBS followed by cold buffered formalin fixation, the arch and thoracic portion of the dorsal aorta were dissected free from the thoracic cavity and heart. In selected cases, the entire aorta was isolated from the arch to the aortic-iliac bifurcation. After the adventitia and adipose tissue were removed, they were placed in 10% neutral buffered formalin overnight. The aorta was then opened lengthwise and pinned flat in a wax-bottomed dissecting pan. The tissue was stained for 15 min with 0.5% Sudan IV solution (9) in acetone and 70% ethanol (1:1). The tissue was decolorized for 5 min using 80% ethanol and then washed gently with running water for several minutes. The en face preparations were digitally photographed and then quantified using Optimas 6.5 software, and percent of plaque coverage was calculated.

Histological evaluation of specimens.

Histological sections of the arch and thoracic portions of the aorta were cut and stained with hematoxylin and eosin (H&E) or Giemsa stains as appropriate. Light microscopy was performed to evaluate the overall architecture with careful attention to atherosclerotic changes in the root, aortic arch, and the thoracic aorta, in addition to any other histopathology alterations. Glass slides were scanned using the Aperio Scanscope System (Vista, CA) to create virtual slides. All virtual slides were analyzed at the same histological magnification, to accurately evaluate plaque thicknesses by the ruler tool. The thickest area of plaque was measured on sections of the root of the aorta near the heart. Measurements of the intima thickness were normalized by the media thickness, and the mean ratio was used to determine differences between groups.

Evaluation of hepatic steatosis.

Formalin-fixed livers were embedded in paraffin, sectioned at 5 μm, and stained with H&E. Slides were examined by light microscopy by a pathologist (Tawfik) for evidence of steatosis, inflammation, fibrosis, cirrhosis, and other abnormalities. Steatosis was scored, in a blinded fashion, on a scale of zero to three (where 0 = <5%, 1 = 5–33%, 2 = 33–66%, and 3 = >66%). Micro- and macrosteatosis were also recorded for each animal.

Serum chemistry and lipid profiles.

Sera were prepared from blood samples collected from the retroorbital sinus or at the time of necropsy. Serum chemistry and lipid profiles were analyzed at the Veterinary Laboratory Resources, Physicians Reference Laboratory (Overland Park, KS). Briefly, the values for total cholesterol and triglycerides were determined by enzymatic assays, and HDL was determined by spectrophotometry. Very low density lipoprotein (VLDL) was calculated as one-fifth of the triglyceride value, and LDL was calculated by the Friedewald formula.

Serum cytokines.

Assessments of serum levels of IL-2, IL-4, IL-6, interferon (IFN) γ, tumor necrosis factor (TNF)-α, IL-17A, and IL-10 were carried out by flow cytometry using the BD Mouse Cytometric Bead Array kit for Th1/Th2/Th17 cytokine panel (BD Biosciences, San Jose, CA).

Thromboxane A2 and prostaglandin I2 metabolites in the urine.

The levels of 11-dehydrothromboxane B2 and 2,3-dinor-6-keto prostaglandin F1α in the 24-h urine samples were quantified by using competitive EIA kits to evaluate the systemic production of thromboxane (TX) A2 and prostaglandin I2 (PGI2), respectively. The values for the prostanoid metabolites in the 24-h urine samples were normalized for the creatinine content. The 2,3-dinor-6-keto prostaglandin F1α required purification and spiking protocols to obtain the final results. The creatinine assay kit (no. 500701) and EIA kits for 11-dehydrothromboxane B2 (no. 519501) and 2,3-dinor-6-keto prostaglandin F1α (no. 515121) were purchased from Cayman Chemical (Ann Arbor, MI).

Quantitative real-time RT-PCR for the expression of COX-2 and toll-like receptor 2 and 4 mRNA.

Total RNA was extracted from the aorta of three animals from each group after 6 mo on a high-fat diet using the RNeasy Mini Kit from Qiagen according to the manufacturer's manual. Total RNA was reverse transcribed into first-strand cDNA using the High-Capacity cDNA Reverse Transcription Kit following the manufacturer's procedure. Real-time RT-PCR was performed using the ABI 7500 Real-Time PCR system (Applied Biosystems). The amplification reactions were performed in 25 μl total volume containing SYBR Green PCR Master Mix with respective primers and 5 μl of cDNA of each animal. The primers were designed using Primer Express Software version 3.0 (Applied Biosystems). The sequences of the primers used are as follows: COX-2 forward: TGCCTCCCACTCCAGACTAGA, reverse: CAGCTCAGTTGAACGCCTTTT; Toll-like receptor (TLR) 2 forward: CCCTGTGCCACCATTTCC, reverse: CCCTGTGCCACCATTTCC; TLR4 forward: GCAGCAGGTGGAATTGTATCG, reverse: TGTGCCTCCCCAGAGGATT; and β-actin forward: ACCAGTTCGCCATGGATGAC, reverse: TGCCGGAGCCGTTGTC. The mRNA expression of each gene was normalized with mRNA expression of β-actin by the comparative ΔΔCT method. For each gene, the mRNA expression in one sample from the ApoE−/− group was set as unit one, and the fold changes of mRNA expression of other samples were calculated.

Immunohistochemical studies.

The presence of T cells, mast cells, and macrophages was evaluated after immunostaining of the paraffin sections with anti-CD3 (no. N1580; DAKO, Carpinteria, CA), anti-CD117 (no. 14–1172; eBioscience, San Diego, CA), and anti-CD68 (no. MS-397; Lab Vision, Freemont, CA), respectively. The level of expression of scavenger receptors CD36, LOX 1, SR-BI, and SR-A in aortic atheromas was determined after immunostaining of paraffin sections with antibodies (ab) 78054, ab85839, and ab24603 from Abcam (Cambridge, MA) and antibody sc-20660 from Santa Cruz (Santa Cruz, CA), respectively. Hematoxylin was used as a counter stain. Appropriate positive and negative controls were used for validation. Positive immunohistochemical reactions were defined as a dark brown reaction. Tissues from at least four mice per group were analyzed.

Quantification of immunohistochemical stains.

After completion of immunohistochemical staining, slides were placed on the ACIS automated imaging system (DAKO) for quantifying the tissue staining. The system consists of an automated microscope, a three-chip Sony progressive scan camera, a computer, and Windows NT 4.0 workstation software interface. Each slide was scanned by the robotic microscope. The ACIS system captures images from each slide, quantifies staining in selected regions, and presents a numerical score. It was used to quantify immunohistochemical staining of percent positive cells for CD68 and for CD3. An average score for all selected areas was then calculated for each marker. Mast cells were identified on slides stained with Giemsa and CD117 antibody and quantified by averaging the number of mast cells counted in five high-power fields. The intensity of scavenger receptor staining in aortic atheromas was graded on a scale from zero to three.

Statistical analyses.

The data are expressed as means ± SE, with a value of “n” given in the bars. Student's two-tailed t-test was used to compare two groups, and multiple groups were compared using a one-way ANOVA. In a few selected cases, the Two-Sample Mann-Whitney tests were utilized. All tests were considered significant with a “P” value ≤0.05.

RESULTS

ApoE−/−/KitW-sh/W-sh mice have reduced development of atherosclerosis lesions in the aorta.

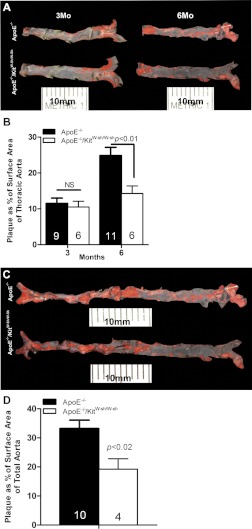

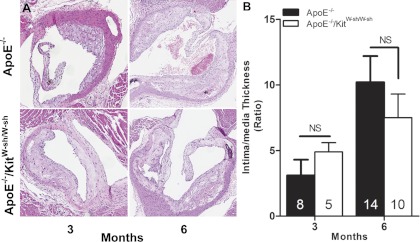

To determine the effect of mast cell deficiency on the progression of atherosclerosis, we compared the coverage of the lesion area in Sudan IV-stained en face preparations of thoracic aorta of ApoE−/− and ApoE−/−/KitW-sh/W-sh mice at the end of 3 and 6 mo of the high-fat regimen (Fig. 1, A and B). We also compared the coverage of the lesion area over the entire length of the aorta, from the arch to the iliac bifurcation, at 6 mo to verify that we were not overlooking anatomically disparate deposition of plaque (Fig. 1, C and D). In addition, we quantified the ratio of intima/media thickness of the lesion at the root of the aorta on H&E-stained histological cross sections. As shown in Fig. 1, A and B, and Fig. 2, A and B, ApoE−/− and ApoE−/−/KitW-sh/W-sh mice maintained on the high-fat regimen for 3 mo developed comparable levels of plaque as assessed by the percent coverage of total area and by the intima/media thickness. When the high-fat regimen was extended to 6 mo, there was a progressive increase in aortic plaque development in ApoE−/− mice. However, this time-dependent enhancement of the lesion development was found to be markedly reduced in ApoE−/−/KitW-sh/W-sh mice (Fig. 1, A-D). Although we did not find a significant difference in intima/media thickness of the plaque in the aortic sinus between the two genotypes of mice at 6 mo, a trend toward decreased lesion thickness was evident in ApoE−/−/KitW-sh/W-sh mice (Fig. 2B).

Fig. 1.

Development of aortic atherosclerotic lesions in apolipoprotein E-deficient (ApoE−/−) and ApoE−/−/mast cell-deficient (KitW-sh/W-sh) mice maintained on the high-fat diet for 3 or 6 mo. At necropsy, the thoracic aorta was dissected out, fixed overnight in buffered formalin, spread, and stained with Sudan IV. A: representative en face preparations of thoracic aortas from age-matched ApoE−/− and ApoE−/−/KitW-sh/W-sh mice at 3 or 6 mo on the regimen. B: quantification of the digital images of en face preparations representing percent of total area of the arch and thoracic aorta covered by plaque. C: comparison of representative en face preparations of the complete dorsal aorta from age-matched ApoE−/− and ApoE−/−/KitW-sh/W-sh mice at 6 mo on the regimen. D: quantification of the digital images of en face preparations representing percent of total area of complete aortas covered by plaque. The data presented are means ± SE. The no. of mice used per group is given in each bar.

Fig. 2.

The ratio of intima/media thickness of atheromas in the aortic root of ApoE−/− and ApoE−/−/KitW-sh/W-sh mice maintained on the high-fat diet for 3 or 6 mo. A: representative hematoxylin and eosin (H&E)-stained cross sections at the root of the aorta of ApoE−/− and ApoE−/−/KitW-sh/W-sh mice. B: H&E-stained cross sections were imaged, and the thickness of intima and media was measured at the thickest part of plaque. Original magnifications at ×100. The data presented are means ± SE with the no. of mice used per group given in each bar.

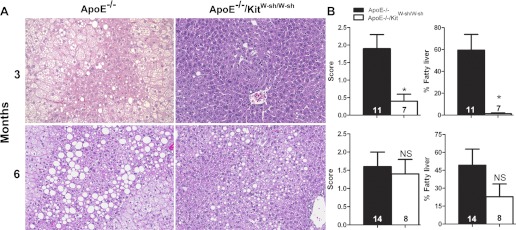

ApoE−/−/KitW-sh/W-sh mice have decreased levels of hepatic steatosis compared with ApoE−/− mice.

H&E-stained liver sections were graded on a scale of zero to three, and an estimate was made of the percentage of liver involved in combined micro- and macrovesicular steatosis. At 3 mo, ApoE−/−/KitW-sh/W-sh mice had significantly reduced levels of hepatic steatosis (Fig. 3) compared with ApoE−/− mice. However, by 6 mo, most livers of both genotypes had become heavily loaded with fat, and no significant differences were noted.

Fig. 3.

Differences in the amount of steatosis in the liver of ApoE−/− and ApoE−/−/KitW-sh/W-sh mice maintained on the high-fat diet for 3 or 6 mo. A: representative photomicrographs stained with H&E showing significantly greater amounts of lipid in the livers of ApoE−/− compared with ApoE−/−/KitW-sh/W-sh mice at 3 mo (A) and similar trend but statistically nonsignificant findings at 6 mo. B: graphic representation of combined micro- and macrovesicular hepatic steatosis as determined by severity scores from 0 to 3, and by an assessment of the percentage of liver involved in steatosis at 3 and 6 mo. Original magnifications at ×200. The data presented are means ± SE with the no. of mice used per group given in each bar. *P < 0.02.

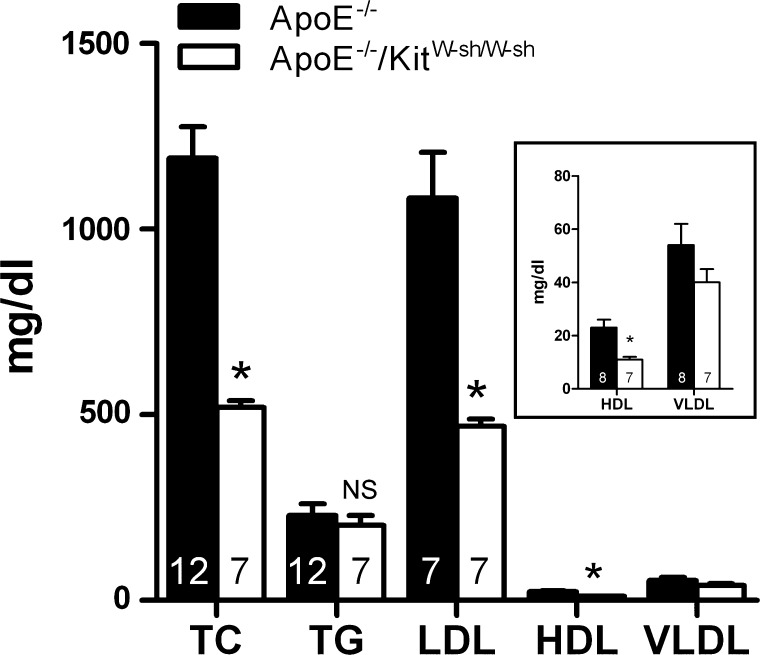

Serum lipids and chemistry.

The results depicted in Fig. 4 illustrate the serum lipid profile for ApoE−/− and ApoE−/−/KitW-sh/W-sh mice. In regard to serum lipids, mast cell deficiency led to ∼50% reduction in the levels of total cholesterol, LDL, and HDL in ApoE−/− mice, but no differences were noted in the levels of triglycerides or VLDL. With respect to the serum chemistry, we did not find any significant differences in the serum levels of glucose, blood urea nitrogen, amylase, or lipase between ApoE−/− and ApoE−/−/KitW-sh/W-sh mice (data not shown). It is noteworthy that both genotypes were found to be hyperglycemic (ApoE−/− =253 ± 32 vs. ApoE−/−/KitW-sh/W-sh = 338 ± 14 mg/dl) compared with wild-type C57 Bl/6J male mice on a normal diet (61 ± 9 mg/dl). Compared with to ApoE−/− mice, ApoE−/−/KitW-sh/W-sh mice presented with significantly decreased levels of alkaline phosphatase (ApoE−/− = 83 ± 4 U/l vs. ApoE−/−/KitW-sh/W-sh = 65 ± 7 U/l) and alanine aminotransferase (ApoE−/− = 227 ± 54 U/l vs. ApoE−/−/KitW-sh/W-sh = 51 ± 7 U/l), with the latter being reduced by 78% in the genotype that lacked mast cells.

Fig. 4.

Serum lipid profile of ApoE−/− and ApoE−/−/KitW-sh/W-sh mice. Animals were allowed to consume the high-fat diet ad libitum for a period of 3 mo. Serum lipid profiles were analyzed at a commercial laboratory. Each value presented is the mean ± SE with the no. of animals used given in each bar. Data presented in the inset are an enlarged depiction of the high-density lipoprotein (HDL) and very low density lipoprotein (VLDL) histogram. TC, total cholesterol; TG, triglycerides; LDL, low-density lipoprotein. *P ≤ 0.01.

ApoE−/−/KitW-sh/W-sh mice have reduced levels of serum IL-6 and IL-10.

Changes in the levels of inflammatory cytokines are known to influence vascular inflammation and atherosclerosis. Therefore, to determine whether mast cell deficiency alters cytokine levels in ApoE−/− mice, we measured the serum levels of IL-2, IL-4, IL-6, IL-10, IL-17A, IFNγ, and TNF-α. Compared with ApoE−/− mice, the serum levels of IL-6 and IL-10 were significantly lower in ApoE−/−/KitW-sh/W-sh (Table 1). Although not statistically significant, a trend toward a decreased concentration of IL-17A was also noted in ApoE−/−/KitW-sh/W-sh mice. Mast cell deficiency did not alter the serum levels of IL-2, IL-4, IFNγ and TNF-α in ApoE−/− mice.

Table 1.

Serum cytokine levels in ApoE−/− and ApoE−/−/KitW-sh/W-sh mice maintained on the high-fat diet regimen for 6 mo

| Serum Cytokine, pg/ml | ApoE−/− | n | ApoE−/−/KitW-sh/W-sh | n |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| IL-2 | 10.5 ± 0.4 | 8 | 10.1 ± 0.5 | 7 |

| IL-4 | 9.1 ± 1.3 | 8 | 7.6 ± 0.4 | 7 |

| IL-6 | 17.3 ± 1.5 | 8 | 11.0 ± 1.4* | 6 |

| IL-10 | 111.9 ± 14.4 | 8 | 74.9 ± 14.2* | 7 |

| IL-17A | 16.0 ± 3.0 | 8 | 12.7 ± 1.2 | 7 |

| IFNγ | 11.9 ± 0.6 | 8 | 11.4 ± 0.9 | 7 |

| TNFα | 29.5 ± 1.9 | 8 | 36.3 ± 3.2 | 7 |

Values are means ± SE; n, no. animals. ApoE−/−, apolipoprotein E-deficient; ApoE−/−/KitW-sh/W-sh, ApoE−/−/mast cell-deficient; IL, interleukin; IFN, interferon; TNF, tumor necrosis factor.

P < 0.05 compared with ApoE−/−.

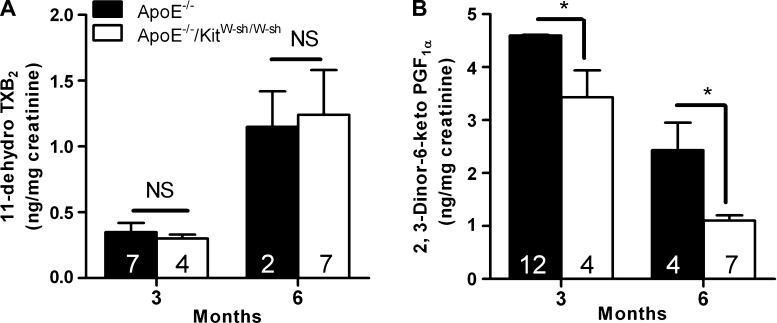

Mast cell deficiency did not alter urinary levels of TXA2 but decreased PGI2 metabolites in ApoE−/− mice.

Previous studies have shown that TXA2 promotes and PGI2 attenuates the initiation and progression of atherogenesis in ApoE−/− mice (24, 37). Results presented in Fig. 5A show that the mast cell deficiency did not alter the urinary levels of 11-dehydrothromboxane B2 in ApoE−/− mice at either 3 or 6 mo. However, an approximately threefold increase in urinary TXB2 levels was noted in both ApoE−/− and ApoE−/−/KitW-sh/W-sh mice when the high-fat regimen was extended to 6 mo. In the case of PGI2, the urinary levels of its stable metabolite, 2,3-dinor-6-keto prostaglandin F1α, were significantly lower in ApoE−/−/KitW-sh/W-sh mice compared with ApoE−/− mice at both time points (Fig. 5B). It is noteworthy that an increase in the systemic production of TXA2 with concomitant decrease in PGI2 was evident in both genotypes as the disease progressed.

Fig. 5.

Levels of stable metabolites of thromboxane (TX) A2 and prostaglandin (PG) I2 in the 24-h urine samples of ApoE−/− and ApoE−/−/KitW-sh/W-sh mice. Animals were allowed to consume the high-fat diet ad libitum for a period of 3 or 6 mo. Twenty-four-hour urine samples were collected housing each mouse in a metabolic cage. 11-Dehydro TXB2 (A) and 2,3-dinor-6-keto PGF1α (B) were analyzed by using EIA kits. Results are expressed as ng/mg creatinine. Each value presented is the mean ± SE with the no. of animals given in each bar. *P < 0.01 between ApoE−/− and ApoE−/−/KitW-sh/W-sh mice for PGI2 metabolites at both 3 and 6 mo.

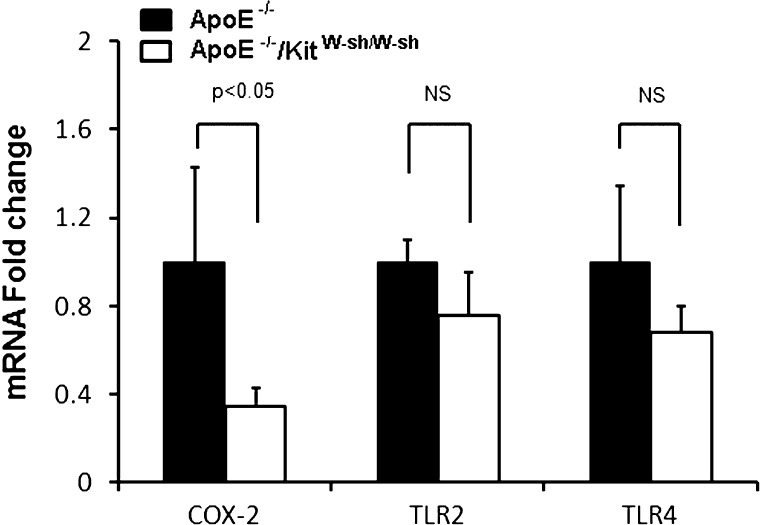

Mast cell deficiency resulted in decreased expression of COX-2 mRNA in the aorta.

Histamine, a major product of the mast cell, has been shown to enhance the expression of COX-2, TLR2, and TLR4 in endothelial cells (41, 42). In the present study, the expression of COX-2 mRNA was significantly reduced in the aorta of ApoE−/−/KitW-sh/W-sh mouse compared with the ApoE−/− mouse at 6 mo (Fig. 6). Although modest decreases in the expression of both TLR2 and TLR4 mRNA were also noted in the ApoE−/−/KitW-sh/W-sh mouse, the changes were not found to be statistically significant.

Fig. 6.

Mast cell deficiency decreases the expression of cyclooxygenase-2 (COX-2) mRNA in the aorta of ApoE−/− mice. After 6 mo on the high-fat regimen, aortas were analyzed for mRNA expression of COX-2, Toll-like receptor (TLR) 2, and TLR4 by real-time qRT-PCR. Data presented are means ± SE of 3 mice/group.

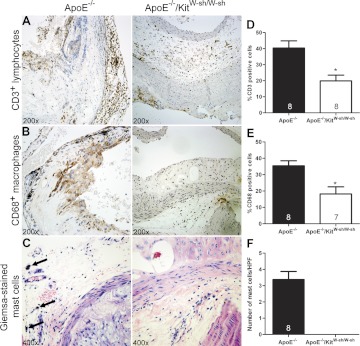

Plaques in ApoE−/−/KitW-sh/W mice had reduced number of T-lymphocytes and macrophages, and no mast cells.

To determine the relative densities of T-lymphocytes, macrophages, and mast cells in atheromas, the cross sections at the aortic root were stained with antibodies against CD3, CD68, and CD117, respectively. For mast cell enumeration, Giemsa-stained slides were used. As shown in Fig. 7, the tissues from ApoE−/−/KitW-sh/W-sh had ∼50% fewer numbers of T-lymphocytes and macrophages than ApoE−/− mice. Although approximately three mast cells were found per high-power field in the aortic tissues of ApoE−/− mice, as expected, no mast cells were found in ApoE−/−/KitW-sh/W-mice.

Fig. 7.

Mast cell deficiency reduces the recruitment of T lymphocytes and macrophages in the atherosclerotic lesions in ApoE−/− mice. Representative images of immunohistochemically stained sections and the graphic representation of cell counts depict reduced numbers of T lymphocytes (A and D) and macrophages (B and E) in ApoE−/−/KitW-sh/W-sh mice, as well as the presence and absence of mast cells in the ApoE−/− and ApoE−/−/KitW-sh/W-sh mice, respectively (C and F). Arrows depict degranulated mast cell in a Giemsa-stained section. Original magnification for T lymphocytes and macrophages is ×200. C: the magnification for mast cells is ×400. Data presented are means ± SE. The no. of mice used per group is given in each bar. *p < 0.05 compared with ApoE−/− mice (Student's t-test). No mast cell was seen in ApoE−/−/KitW-sh/W-sh mice (F).

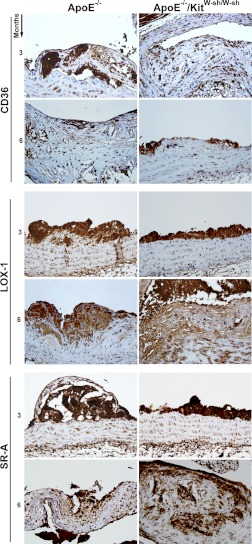

Intensity of staining for scavenger receptors CD36, LOX -1, SR-A, and SR-BI in atheromas of the aortic root were similar in both genotypes.

Histological sections of the aortic root from four mice in each group were stained for scavenger receptors CD36, LOX 1, SR-A, and SR-BI using specific antibodies. In the case of CD36, LOX-1, and SR-A, the average scoring of the staining in aortic atheromas was similar in both ApoE−/−/KitW-sh/W-sh and ApoE−/− mice at both time periods (Fig. 8). Interestingly, SR-BI staining was not detected in the atheromas of either genotype after the 3- or 6-mo high-fat regimen, but staining was present in the livers (data not shown), which validates that the reagents and techniques were optimal.

Fig. 8.

No differences were observed in the intensity of staining for scavenger receptors CD36, LOX 1, and SR-A in the atherosclerotic lesions located at the root of the aorta in both genotypes of mice. Representative images of immunohistochemically stained sections using antibodies against CD36, LOX-1, and SR-A showing intensity of stain in atheromas of ApoE−/− and ApoE−/−/KitW-sh/W-sh mice at 3 and 6 mo. Staining on sections from four mice was scored on a scale from 0 to 3. No differences in staining could be discerned between ApoE−/− and ApoE−/−/KitW-sh/W-sh mice at either 3 or 6 mo. The antibody against SR-BI did not stain cells of the atheromas in the root of the aortas in any of the mice (data not shown). Original magnification at X40.

DISCUSSION

Mast cells are important cells of the immune system, and they synthesize and secrete a wide variety of proinflammatory and anti-inflammatory mediators. Increasing evidence now suggests a role for mast cells in vascular inflammation and atherosclerosis. In this study, we evaluated the involvement of mast cells in the progression of atherosclerosis using the ApoE−/−/KitW-sh/W-sh model, which is deficient in both ApoE and mast cells. Because the ApoE−/− mouse model is extensively used to evaluate the pathophysiology of atherosclerosis (3–5, 31), the ApoE−/−/KitW-sh/W-sh model is a useful tool to examine the involvement of mast cells in atherosclerosis. Although these animals develop aortic atherosclerosis spontaneously when maintained on a normal rodent diet, the disease progression is accelerated by the high-fat regimen (29). Based on our previous studies, serum levels of total cholesterol and LDL are at least twofold higher in both wild-type and ApoE−/− mice when maintained on a high-fat diet compared with a normal chow diet (data not shown), thus lending support to the contention that dietary fat increases total serum cholesterol, which in turn increases the progression of atherosclerosis in susceptible mice. The results of the present study demonstrate that mast cell deficiency significantly reduces the progression of atherosclerosis in ApoE−/− mice maintained on a high-fat diet for 6 mo as assessed by the area of plaque coverage in the aorta. The fact that the plaque coverage was comparable in ApoE−/− and ApoE−/−/KitW-sh/W-sh mice at 3 mo suggests that the atherosclerosis progression was at the same pace in both genotypes during the early stages. It is noteworthy that the reduction in the development of atherosclerotic lesions in ApoE−/− mice due to mast cell deficiency was found to be associated with significant reduction in hepatic steatosis and serum levels of cholesterol, LDL, and HDL. In concordance with the reduced aortic plaques in ApoE−/−/KitW-sh/W-sh mice, there was a significant decline in the number of T-lymphocytes and macrophages. Furthermore, ApoE−/−/KitW-sh/W-sh mice also presented with significant reduction in serum IL-6 and IL-10.

It is well-recognized that the serum levels of cholesterol, triglycerides, and LDL are elevated in atherogenic mouse models maintained on a high-fat regimen (8, 37). Here, we present evidence to show that mast cell deficiency reduces the serum levels of total cholesterol, LDL, and HDL by ∼50% in ApoE−/− mice maintained on the high-fat diet for 3 mo. Although we were unable to determine the serum lipid profile at the end of 6 mo because of insufficient amounts of serum samples, the pattern of reduced serum levels of cholesterol, LDL, HDL, and alanine aminotransferase was seen in LDLr−/−/KitW-sh/W-sh mice (19). Taken together, we can conclude that mast cell deficiency reduces hypercholesterolemia in both ApoE−/− and LDLr−/− mouse models. Triglycerides and VLDL were not significantly different in our mouse models at 3 mo, suggesting that ApoE and mast cells differently affect triglyceride and cholesterol levels. In this regard, mast cell chymase has been implicated in the promotion of LDL cholesterol uptake by macrophages (19). It is plausible that the overall cholesterol absorption from the gut may also be decreased in mast cell-deficient animals, suggesting that mast cells play a major role in lipid homeostasis.

Increasing evidence indicates an association between fatty liver disease and cardiovascular disease (43). Mast cells are present in normal livers, and their numbers are increased in fatty liver disease (13, 14, 26). In agreement with these finding, ApoE−/−/KitW-sh/W-sh presented with significantly reduced hepatic steatosis during the first 3 mo of the high-fat regimen. However, by 6 mo, both genotypes of mice developed comparable levels of hepatic steatosis. To our surprise, the lack of significant difference in hepatic steatosis at 6 mo did not coincide with the significant differences in plaque development at this time point. We speculate that, although mast cells are involved in serum lipid homeostasis, atherosclerosis, and hepatic steatosis, their kinetics seem to be distinct. It is apparent that the hepatic steatosis takes place at a relatively faster rate in ApoE−/− mice and attains a plateau between 3 and 6 mo of the regimen, whereas, in the case of ApoE−/−/KitW-sh/W-sh mice, hepatic steatosis progresses at a slower pace but merges with the plateaued level of ApoE−/− mice by around 6 mo. Therefore, the degree of hepatic steatosis became indistinguishable at 6 mo between the groups. We speculate that the deficiency of mast cell-derived proteases or other unidentified factors leads to reduced LDL uptake by macrophages and decreased foam cell formation in ApoE−/−/KitW-sh/W-sh. This leads to reduced hepatic steatosis and atherogenesis in the ApoE−/−/KitW-sh/W-sh mouse model. The marked reduction in the serum levels of alanine aminotransferase (78%) in ApoE−/−/KitW-sh/W-sh mice confirms a lesser degree of steatosis-associated liver damage in this genotype at 3 mo. Indeed, this was supported by the finding of significantly decreased micro- and macrovesicular steatosis in the livers of ApoE−/−/KitW-sh/W-sh mice compared with ApoE−/− mice at 3 mo. Surprisingly, there was no apparent difference in the wet weight of the liver between the genotypes at either 3 or 6 mo (data not shown).

TXA2 and PGI2 are products of the cyclooxygenase pathway and have been implicated in the process of atherosclerosis in humans (2, 11) and mouse models (24, 32). It is generally agreed that PGI2 reduces, and TXA2 enhances, the initiation and progression of atherogenesis through their opposing effects in the regulation of vasodilatation, platelet aggregation, and leukocyte-endothelial cell interactions (24). Because PGI2 and TXA2 are important players in the regulation of endothelial functions, a tightly regulated PGI2/TXA2 homeostasis is critical for the prevention of cardiovascular disease. In this regard, an increased systemic generation of TXA2 with reduced production of PGI2 was found to be associated with enhanced atherosclerotic lesion development in female ApoE−/− mice (37). Although the atherosclerotic lesion formation was reduced by ∼50% in ApoE−/−/KitW-sh/W-sh mice after the 6-mo regimen, to our surprise, there was no significant reduction in the urinary levels of TXA2 metabolites (Fig. 5A). In addition, the production of PGI2 in ApoE−/−/KitW-sh/W-sh mice was found to be significantly lower than in ApoE−/− mice by 25 and 53% at the end of 3 and 6 mo of the high-fat regimen, respectively (Fig. 5B). The reduced levels of PGI2 production in ApoE−/−/KitW-sh/W-sh mice were correlated with the decreased expression of COX-2 mRNA in the aortic tissues determined at 6 mo. These results suggest that differences in the systemic production of TXA2 and PGI2 are not a contributing factor in the reduced progression of atherosclerosis in ApoE−/−/KitW-sh/W-sh mice. In agreement with the current concept of the relative production of TXA2 and PGI2 during atherosclerosis progression, we observed a three- to fourfold increase in the production of TXA2 with a reduction in PGI2 by 47 and 68% in ApoE−/− and ApoE−/−/KitW-sh/W-sh mice, respectively, as the high-fat regimen was continued to 6 mo. Mast cells are known to synthesize and secrete a variety of prostanoids and leukotrienes, some of which have proinflammatory effects. Therefore, it is reasonable to postulate that deficiency of mast cells will reduce proinflammatory pathways in the vasculature and reduce atherosclerosis in ApoE−/− mice.

Activated mast cells, macrophages, and T-lymphocytes recruited to the vessel wall during atherogenesis generate many cytokines (15). To determine whether the decreased atherogenesis in ApoE−/−/KitW-sh/W-sh mice is associated with differences in the systemic production of cytokines, we analyzed the serum levels of selected cytokines. Among the panel of cytokines tested, we found only IL-6 and IL-10 to be significantly decreased in ApoE−/−/KitW-sh/W-sh mice. In a previous report, reconstitution of bone marrow-derived mast cells from wild-type C57BL6 control to LDLr−/−/KitW-sh/W-sh mice, but not from IL-6−/− or IFN−/− mice, reversed the decreased lesion formation to the levels in LDLr−/− mice, suggesting a role for mast cell-derived IL-6 and IFNγ in atherosclerosis progression (39). Although our results showing reduced serum IL-6 levels in ApoE−/−/KitW-sh/W-sh mice support the potential role of IL-6 in the atherosclerotic lesion development, we did not find any evidence that suggested a role for mast cell-derived IFNγ in the disease progression in the ApoE−/− mouse. This contention is supported by the finding that serum levels of IFNγ in ApoE−/−/KitW-sh/W-sh mice were comparable to that of ApoE−/− (Table 1). We recognize that this inference is based on the serum cytokine levels in these genotypes and not based on the effect of mast cell reconstitution experiments, as shown by Sun et al. (39). Conversely, since they have not determined the serum levels of cytokines, one cannot ascertain the systemic production of these cytokines in the LDLr−/− and LDLr−/−/KitW-sh/W-sh mice. In regard to the reduced levels of IL-10 in ApoE−/−/KitW-sh/W-sh mice, we speculate that the absence of mast cells and reduced number of T-lymphocytes in the vessel wall cause this reduction.

Progression of atherosclerosis involves increased recruitment of macrophages, T lymphocytes, and mast cells (27) and subsequent generation of proinflammatory cytokines, chemokines, and proteases (23, 39, 44). In agreement with this concept, we found a substantial number of T-lymphocytes (CD3+) and macrophages (CD68+) in the atherosclerotic lesions of the ApoE−/− mice. In addition, a number of intact and degranulating mast cells were present in the adventitia of the vessel wall of these mice. In contrast, the number of T-lymphocytes and macrophages was significantly lower in the lesions of ApoE−/−/KitW-sh/W-sh mice. As expected, no mast cells were found in the vessel wall of the KitW-sh/W-sh mice. These findings are in agreement with an earlier report demonstrating reduction in the number of T-lymphocytes and macrophages in the atheromas of LDLr−/−/KitW-sh/W-sh mice compared with LDLr−/− mice (39). The immunohistochemical staining for scavenger receptors CD36, LOX-1, and SR-A was found to be similar in the atheromas at the root of the aorta in both ApoE−/− and ApoE−/−/KitW-sh/W-sh mice. Although immunohistochemical staining for SR-BI was not observed in the aortic atheromas, positive staining was noted in the livers of both genotypes.

In summary, the present study shows that mast cell deficiency significantly reduces progression of atherosclerosis in the ApoE−/− mice maintained on a high-fat diet for 6 mo as assessed by the area of plaque coverage in the aorta. The reduction in the atherosclerotic lesion development in ApoE−/−/KitW-sh/W-sh mice was associated with a marked decrease in hepatic steatosis, reduced serum levels of cholesterol, LDL, and HDL, and significant decline in the number of T-lymphocytes and macrophages in atheromas. Furthermore, ApoE−/−/KitW-sh/W-sh mice also had significantly lower circulating levels of IL-6 and IL-10 than ApoE−/− mice with no changes in the levels of IL-2, IL-4, IL-17, IFNγ and TNF-α. It is noteworthy that mast cell deficiency did not alter systemic production of TXA2 in ApoE−/− mice but led to significant reduction in the production of PGI2. Because the level of COX-2 mRNA expression in the aortic tissues of ApoE−/−/KitW-sh/W-sh mice was also found to be significantly lower than that in ApoE−/− mice, it is reasonable to postulate that mast cells play a role in the prostanoid homoeostasis. In this regard, the ability of histamine, a major product of the mast cell, to induce COX-2 expression and PGI2 production in human coronary artery endothelial cells, and the markedly reduced expression of COX-2 mRNA in the aorta of histidine decarboxylase-null mouse (42) emphasize the importance of mast cells in vascular inflammation. Taken together, it is believed that the marked reduction of hypercholesterolemia and vascular inflammation due to mast cell deficiency leads to attenuation of atherosclerosis progression in ApoE−/−/KitW-sh/W-sh mice.

GRANTS

This work was supported by National Institutes of Health Grants R01-HL-070101 and 3R01-HL-070101–04S1, the Joseph and Elizabeth Carey Arthritis Fund, the Audrey E Smith Medical Research Endowment Fund, and the Department of Internal Medicine Research Office, University of Kansas Medical Center.

DISCLOSURES

No conflicts of interest are declaredby the authors.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

D.D.S., X.T., and O.T. performed experiments; D.D.S., X.T., V.V.R., O.T., and K.N.D. analyzed data; D.D.S., X.T., V.V.R., O.T., D.J.S., and K.N.D. interpreted results of experiments; D.D.S., X.T., V.V.R., and O.T. prepared figures; D.D.S. and K.N.D. drafted manuscript; D.D.S., X.T., V.V.R., O.T., and K.N.D. edited and revised manuscript; D.D.S., X.T., V.V.R., O.T., and K.N.D. approved final version of manuscript; D.J.S. and K.N.D. conception and design of research.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank Dennis Friesen for photographic work and scanning the digital slides for measurement of plaque thickness; Marsha Danley for performing immunohistochemistry protocols; Marilyn Davis for scanning immunohistochemistry slides on the ACIS system; Dr. Joyce Slusser for assistance with flow cytometry analyses of the serum cytokines; Dr. Michael Brimacombe for statistical analyses of selected data sets; and Dr. Xiaomei Yao for assistance in analyzing digitized images of en face preparations.

REFERENCES

- 1. Atkinson JB, Harlan CW, Harlan GC, Virmani R. The association of mast cells and atherosclerosis: a morphologic study of early atherosclerotic lesions in young people. Hum Pathol 25: 154–159, 1994 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Belton O, Byrne D, Kearney D, Leahy A, Fitzgerald DJ. Cyclooxygenase-1 and -2-dependent prostacyclin formation in patients with atherosclerosis. Circulation 102: 840–845, 2000 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Belton OA, Duffy A, Toomey S, Fitzgerald DJ. Cyclooxygenase isoforms and platelet vessel wall interactions in the apolipoprotein E knockout mouse model of atherosclerosis. Circulation 108: 3017–3023, 2003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Bot I, de Jager SC, Zernecke A, Weber C, van Berkel TJ, Biessen EA. Mast cell activation promotes leukocyte recruitment and adhesion to the atherosclerotic plaque. Circulation 116: 242, 2007 [Google Scholar]

- 5. Bot I, de Jager SCA, Zernecke A, Lindstedt KA, van Berkel TJC, Weber C, Biessen EAL. Perivascular mast cells promote atherogenesis and induce plaque destabilization in apolipoprotein E-deficient mice. Circulation 115: 2516–2525, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Davies MJ. The composition of coronary-artery plaques. N Engl J Med 336: 1312–1314, 1997 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. DeSchryver-Kecskemeti K, Williamson JR, Jakschik BA, Clouse RE, Alpers DH. Mast cell granules within endothelial cells: a possible signal in the inflammatory process? Mod Pathol 5: 343–347, 1992 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Dileepan KN, Simpson KM, Lynch SR, Stechschulte DJ. Dismutation of eosinophil superoxide by mast cell granule superoxide dismutase. Biochem Arch 5: 153–160, 1989 [Google Scholar]

- 9. Dvorak AM. Mast-cell degranulation in human hearts. N Engl J Med 315: 969–970, 1986 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Fernex M. The Mast-Cell System: Its Relationship to Atherosclerosis, Fibrosis and Eosinophils. Baltimore, MD: Williams & Wilkins, 1968 [Google Scholar]

- 11. FitzGerald GA, Smith B, Pedersen AK, Brash AR. Increased prostacyclin biosynthesis in patients with severe atherosclerosis and platelet activation. N Engl J Med 310: 1065–1068, 1984 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Forman MB, Oates JA, Robertson D, Robertson RM, Roberts LJ, 2nd, Virmani R. Increased adventitial mast cells in a patient with coronary spasm. N Engl J Med 313: 1138–1141, 1985 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Franceschini B, Ceva-Grimaldi G, Russo C, Dioguardi N, Grizzi F. The complex functions of mast cells in chronic human liver diseases. Dig Dis Sci 51: 2248–2256, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Franceschini B, Russo C, Dioguardi N, Grizzi F. Increased liver mast cell recruitment in patients with chronic C virus-related hepatitis and histologically documented steatosis. J Viral Hepatitis 14: 549–555, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Galkina E, Ley K. Immune and inflammatory mechanisms of atherosclerosis. Annu Rev Immunol 27: 165–197, 2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Galli SJ. New concepts about the mast cell. N Engl J Med 328: 257–265, 1993 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Glass CK, Witztum JL. Atherosclerosis: the road ahead. Cell 104: 503–516, 2001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Hansson GK, Libby P, Schonbeck U, Yan ZQ. Innate and adaptive immunity in the pathogenesis of atherosclerosis. Circ Res 91: 281–291, 2002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Heikkila HM, Trosien J, Metso J, Jauhiainen M, Pentikainen MO, Kovanen PT, Lindstedt KA. Mast cells promote atherosclerosis by inducing both an atherogenic lipid profile and vascular inflammation. J Cell Biochem 109: 615–623, 2010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Jeziorska M, McCollum C, Woolley DE. Calcification in atherosclerotic plaque of human carotid arteries: associations with mast cells and macrophages. J Pathol 185: 10–17, 1998 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Jeziorska M, McCollum C, Woolley DE. Mast cell distribution, activation, and phenotype in atherosclerotic lesions of human carotid arteries. J Pathol 182: 115–122, 1997 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Kalsner S, Richards R. Coronary arteries of cardiac patients are hyperreactive and contain stores of amines: a mechanism for coronary spasm. Science 223: 1435–1437, 1984 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Kleemann R, Zadelaar S, Kooistra T. Cytokines and atherosclerosis: a comprehensive review of studies in mice. Cardiovasc Res 79: 360–376, 2008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Kobayashi T, Tahara Y, Matsumoto M, Iguchi M, Sano H, Murayama T, Arai H, Oida H, Yurugi-Kobayashi T, Yamashita JK, Katagiri H, Majima M, Yokode M, Kita T, Narumiya S. Roles of thromboxane A2 and prostacyclin in the development of atherosclerosis in apoE-deficient mice. J Clin Invest 114: 784–794, 2004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Kokkonen JO, Vartiainen M, Kovanen PT. Low density lipoprotein degradation by secretory granules of rat mast cells. Sequential degradation of apolipoprotein B by granule chymase and carboxypeptidase A. J Biol Chem 261: 16067–16072, 1986 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Koruk ST, Ozardali I, Dincoglu D, Bitiren M. Increased liver mast cells in patients with chronic hepatitis C. Indian J Pathol Microbiol 54: 736–740, 2011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Li M, Kuo L, Stallone JN. Estrogen potentiates constrictor prostanoid function in female rat aorta by upregulation of cyclooxygenase-2 and thromboxane pathway expression. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 294: H2444–H2455, 2008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Lindstedt KA. Inhibition of macrophage-mediated low density lipoprotein oxidation by stimulated rat serosal mast cells. J Biol Chem 268: 7741–7746, 1993 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Ma Z, Choudhury A, Kang SA, Monestier M, Cohen PL, Eisenberg RA. Accelerated atherosclerosis in ApoE deficient lupus mouse models. Clin Immunol 127: 168–175, 2008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Marks RM, Roche WR, Czerniecki M, Penny R, Nelson DS. Mast cell granules cause proliferation of human microvascular endothelial cells. Lab Invest 55: 289–294, 1986 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Olszanecki R, Jawien J, Gajda M, Mateuszuk L, Gebska A, Korabiowska M, Chlopicki S, Korbut R. Effect of curcumin on atherosclerosis in apoE/LDLR-double knockout mice. J Physiol Pharmacol 56: 627–635, 2005 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Pratico D, Cyrus T, Li H, FitzGerald GA. Endogenous biosynthesis of thromboxane and prostacyclin in 2 distinct murine models of atherosclerosis. Blood 96: 3823–3826, 2000 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Reynolds DS, Gurley DS, Stevens RL, Sugarbaker DJ, Austen KF, Serafin WE. Cloning of cDNAs that encode human mast cell carboxypeptidase A, and comparison of the protein with mouse mast cell carboxypeptidase A and rat pancreatic carboxypeptidases. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 86: 9480–9484, 1989 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Ross R. Atherosclerosis–an inflammatory disease. N Engl J Med 340: 115–126, 1999 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Sakata Y, Komamura K, Hirayama A, Nanto S, Kitakaze M, Hori M, Kodama K. Elevation of the plasma histamine concentration in the coronary circulation in patients with variant angina. Am J Cardiol 77: 1121–1126, 1996 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Schwartz LB, Irani AM, Roller K, Castells MC, Schechter NM. Quantitation of histamine, tryptase, and chymase in dispersed human T and TC mast cells. J Immunol 138: 2611–2615, 1987 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Smith DD, Tan X, Tawfik O, Milne G, Stechschulte DJ, Dileepan KN. Increased aortic atherosclerotic plaque development in female apolipoprotein E-null mice is associated with elevated thromboxane A2 and decreased prostacyclin production. J Physiol Pharmacol 61: 309–316, 2010 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Smith DD, Tan X, Tawfik O, Stechschulte DJ, Dileepan KN. Mast cell deficiency attenuates atherosclerosis in Apolipoprotein E-deficient mice. FASEB J 22: 1065.32: 2008. 18039928 [Google Scholar]

- 39. Sun J, Sukhova GK, Wolters PJ, Yang M, Kitamoto S, Libby P, MacFarlane LA, Mallen-St Clair J, Shi GP. Mast cells promote atherosclerosis by releasing proinflammatory cytokines. Nat Med 13: 719–724, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Takagishi T, Sasaguri Y, Nakano R, Arima N, Tanimoto A, Fukui H, Morimatsu M. Expression of the histamine H1 receptor gene in relation to atherosclerosis. Am J Pathol 146: 981–988, 1995 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Talreja J, Kabir MH, Filla MB, Stechschulte DJ, Dileepan KN. Histamine induces Toll-like receptor 2 and 4 in endothelial cells and enhances sensitivity to Gram-positive and Gram-negative bacterial cell wall components. Immunology 113: 224–233, 2004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Tan X, Essengue S, Talreja J, Reese J, Stechschulte DJ, Dileepan KN. Histamine directly and synergistically with lipopolysaccharide stimulates cyclooxygenase-2 expression and prostaglandin I(2) and E(2) production in human coronary artery endothelial cells. J Immunol 179: 7899–7906, 2007 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Targher G, Day CP, Bonora E. Risk of Cardiovascular Disease in Patients with Nonalcoholic Fatty Liver Disease. N Engl J Med 363: 1341–1350, 2010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Vanderlaan PA, Reardon CA. Thematic review series: the immune system and atherogenesis. The unusual suspects:an overview of the minor leukocyte populations in atherosclerosis. J Lipid Res 46: 829–838, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Vanderslice P, Ballinger SM, Tam EK, Goldstein SM, Craik CS, Caughey GH. Human mast cell tryptase: multiple cDNAs and genes reveal a multigene serine protease family. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 87: 3811–3815, 1990 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]