Abstract

The Canadian Digestive Health Foundation initiated a scientific program to assess the incidence, prevalence, mortality and economic impact of digestive disorders across Canada in 2009. The current article presents the updated findings from the study concerning celiac disease.

Keywords: Burden of disease, Canada, Celiac disease, Chronic disease, Digestive disease, Epidemiology

Abstract

En 2009, la Fondation canadienne pour la promotion de la santé digestive a lancé un programme scientifique pour évaluer l’incidence, la prévalence, la mortalité et les conséquences économiques des maladies digestives au Canada. Le présent article expose les observations mises à jour de l’étude sur la maladie cœliaque.

The Canadian Digestive Health Foundation (CDHF) launched a scientific project to define incidence, prevalence, mortality and economic impact of digestive disorders across Canada. Detailed information was compiled on 19 digestive disorders through systematic reviews, government documents and websites. This information was published as Establishing Digestive Health as a Priority for Canadians, The Canadian Digestive Health Foundation National Digestive Disorders Prevalence and Impact Study Report, and released to the press and government in late 2009 (www.CDHF.ca). The CDHF Public Impact Series presents a full compilation of the available statistics for the impact of digestive disorders in Canada.

Previous studies have indicated that celiac disease is a prevalent, chronic and costly disease representing a considerable burden to health care systems, the individual and, by extension, their families. Although data are available, this information has not been extrapolated to the Canadian context in an accessible format. Written to inform both medical professionals and patients, the present review will increase awareness of celiac disease through a comprehensive overview of disease incidence and prevalence, and the Canadian implications for our health care system and socioeconomics.

METHODS

A systematic literature review was conducted to retrieve peer-reviewed, scholarly literature written in English using the databases PubMed, MEDLINE, EMBASE, and Scopus. The search term used was “celiac disease”, with a specific focus on epidemiology and economic studies from developed countries. Additional information was retrieved from government sources and not-for-profit organizations.

INCIDENCE

In a study of newborns from Denver, Colorado (USA), who were uniformly tested for celiac disease, the predicted incidence of celiac disease potentially affecting the cohort by five years of age was one in 104 (0.9%) (1). European studies of pediatric disease suggest that some countries may have incidence rates as high as one in 300 (2). In the absence of any Canadian data, assuming a conservative 0.9% incidence rate implies that there are 16,540 Canadian children younger than five years of age potentially affected by celiac disease (3).

Delays in the diagnosis of celiac disease (and failure to comply with a gluten-free diet) leads to complications later in life: chronic, nonspecific gastrointestinal complaints; refractory iron-deficiency anemia; infertility; osteoporosis; intestinal lymphoma; and, possibly, the development of other autoimmune diseases (eg, type 1 diabetes) (4,5).

PREVALENCE

The average prevalence of celiac disease in western countries is 1% of the population according to serology studies (range 0.152% to 2.67%) (6). Prevalence, determined by biopsies, is lower, with a range of 0.152% to 1.87%. In North America, the original prevalence rate was estimated to be as low as 33 in 100,000 not-at-risk people. A recent study provides good evidence for a higher prevalence of 949 cases in 100,000 or 1% (6). However, when considering the incidence rate to be at least 0.9%, the 1% prevalence rate is likely to be much higher. By modern standards, celiac disease is considered to be a common medical condition in North America for both adults and children (5,6). In 2011, the Canadian Celiac Association had 28 affiliated chapters and 30 satellite groups (7).

Longitudinal data regarding the increasing prevalence of celiac disease is available for Finland, where large cohorts (eg, 8000 participants) were specifically tested. From 1978 to 1980, the prevalence rate was 1.05% and subsequently increased to 1.99% in 2000 to 2001 (8). A second study conducted in 2010 found that the prevalence rate in adults 30 to 64 years of age was as high as 2.4% (range 2.0% to 2.8%) (9). The high prevalence of celiac disease in Finland is not mirrored in other European countries such as Germany (0.3%) and Italy (0.7%) (9). On average, celiac disease affects 1.0% of the European population and it is not well understood why there are significant regional variations.

A cross-sectional study (n=1200) conducted in the United Kingdom (UK) between 1999 and 2001 (10), found that the prevalence rates of celiac disease were higher in individuals with irritable bowel syndrome (3.3%), iron-deficiency anemia (4.7%) or fatigue (3.3%) compared with the primary care population (1%). Other populations considered to be at-risk for developing celiac disease are first-degree relatives of celiac patients (20%), individuals with symptomatic iron-deficiency anemia (9% to 14%) and those with osteoporosis (1% to 3%) (6,10). Although a previous study found that type 1 diabetes patients had a 3% to 6% increased prevalence of celiac disease compared with the general population, a serology and biopsy study of pediatric type 1 diabetic patients in British Columbia found a prevalence rate that was even higher (7.7%) (6,11). An American study of a pediatric cohort diagnosed with celiac disease (2) found that several patients had thyroiditis, short stature and Down syndrome; the centre now routinely screens these at-risk patients.

Comparing two pediatric celiac disease studies conducted within Canada, it appears that children nowadays are presenting with a greater range of symptoms and signs of the disease and, potentially, at a later age. A study conducted in Toronto (Ontario) in 1969 reported an average age of diagnosis of 2.6 years compared with 4.8 years in the 2005 study (5). This latter onset of noticeable symptoms and signs of celiac disease is also mirrored in an American study. In 153 Wisconsin (USA) children diagnosed with celiac disease, the age at diagnosis was 5.32 years between 1986 and 1995, and 8.70 years for those diagnosed in 1995 through to 2003 (2).

Although a preliminary indicator of celiac disease is a straightforward serum test, the realistic prevalence in Canadian society is likely to be much lower for several reasons. First, the clinical symptoms and signs of celiac disease are widespread, with significant variation between patients and are often unrelated to the gut, such as eczema, bone/joint pain, mouth ulcers and muscle cramps. Several common complaints are only now being associated with celiac disease, such as anemia, mood swings, constipation, extreme weakness and depression (5). In fact, the presence of gastrointestinal symptoms and being underweight, the traditional hallmarks of celiac disease, are usually indicators of more severe disease in children (2,12). Second, the availability of less-expensive celiac disease screening tests was limited within Canada in 2005 (5). Finally, physician and public awareness of the disease has been increasing in the past decade but may still be a barrier to prompt testing. The median time to diagnosis of celiac disease from the onset of symptoms is one year (range zero to 12 years) (5). Even now, there is no medical practice guideline on this topic available in the Canadian Journal of Gastroenterology, although celiac disease guidelines do exist for celiac disease through the North American Society for Pediatric Gastroenterology, Hepatology and Nutrition.

MORTALITY

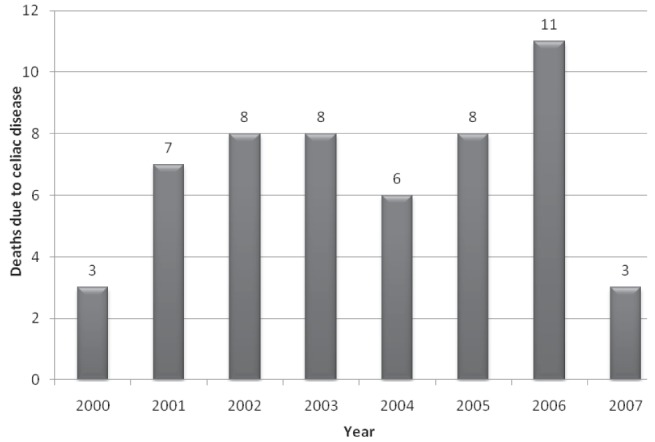

The average number of deaths attributed to celiac disease from 2000 through to 2007 was seven per year (Figure 1) (13).

Figure 1).

Canadian deaths primarily attributed to celiac disease

ECONOMICS

Direct costs

Historically, celiac disease was not believed to be a common disease within North America, and only the most persistent and ill patients were diagnosed. Although the situation is changing, one-third of Canadian families report having to see two or more pediatric physicians before having their child diagnosed with celiac disease (5). Assuming an average charge of CAD$50 for each visit, this delay in diagnosis itself represents a cost of $400,000. Of concern are the results from a longitudinal, pediatric UK study (n=5470) published in 2007 (14). Of the 1% of children who were positive for celiac disease, only 10% had been formally diagnosed by a physician. In combination, the wide variety of nongastrointestinal symptoms and the known protracted delay in obtaining a diagnosis increase the socioeconomic burden of disease because patients are at increased risk for developing complications later in life: chronic nonspecific gastrointestinal complaints; refractory iron-deficiency anemia; infertility; osteoporosis; intestinal lymphoma; and, possibly, the development of other autoimmune diseases (eg, type 1 diabetes) (4,5).

Annual check-ups are recommended to assess the nutritional status and disease progression of the patient. The North American Society for Pediatric Gastroenterology, Hepatology and Nutrition, which includes Canadian physicians, also recommends annual serology tests for tissue transglutaminase antibody (tTG) (15). Interestingly, monitoring the body mass index of patients is an important consideration when studies report that patients gain weight after switching to a gluten-free diet. For example, in an American study (n=188), after two years on a gluten-free diet, 81% of patients experienced weight gain, 4% had no change and 15% had weight loss (12). For patients who were overweight at baseline, 82% gained additional weight.

From an author response regarding serological tests for celiac disease, the cost for a single antibody test was US$50 while the entire panel (immunoglobulin [Ig]A tTG, IgG tTG, endomysial IgA antibodies (EMA) and IgA/G antigliadin antibodies) was US$250 in 2006 (16). However, the article stated that it was more cost effective to begin screening with IgA tTG or IgA EMA, then proceed if only these were positive. A Finnish firm has a home celiac disease testing kit (Biocard Celiac Test, ANIbiotech, Finland) that was approved for sale in Canada (CAD$50) in 2009 (17).

An important consideration of the direct costs of celiac disease is that patients have a 30% increased risk for developing a malignancy compared with the general population; the most common is non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma (4). However, it should be noted that this value may be inflated due to the under-recognition of ‘silent’ or asymptomatic celiac disease cases, which are only identified in large-scale screening studies (4). Typically, the health care costs associated with non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma are $10,650 per patient per year (18).

The scholarly literature is replete with articles describing or calling for cost-effective, population-wide, celiac disease screening. General population testing strategies or targeting high-risk individuals are also being debated. Population screening in the community of six-year-old children by primary care nurses was considered to be a viable approach for identifying individuals who were not identified in the clinical environment. The inexpensive cost, ease of use and rapid results afforded by the Biocard kit makes such an approach feasible (19).

Indirect costs

Presently, the recommended treatment for celiac disease is for the patient to adhere to a gluten-free diet throughout his or her life. This adds to the individual’s food costs and can be inconvenient (20). A recent Canadian study assessed the prices of 56 gluten-free products with similar gluten-containing products (21). The average costs of the gluten-free items were 242% more expensive than their gluten-containing counterparts. If the average weekly food cost for a family of four living in Toronto was $185.44, and assuming that it is easier to cook for the entire family instead of a single person, the food bill would be $448.76 per week (22).

More than one-half of the surveyed members of the Canadian Celiac Association reported extreme difficulty finding gluten-free foods and often encountered poorly labelled food items (5). When asked to rate the two most important areas that would improve a families’ quality of life, better labelling of gluten-containing and gluten-free products was rated the highest at 63% (5,19). Dietary restrictions negatively influenced family activities such as travel or dining out. Fortunately, Health Canada has proposed regulatory amendments to food allergen labelling to encourage manufacturers to clearly state the sourse of gluten in foodstuffs (eg, barley, oats, rye, triticale, or wheat including kamut or spelt) (23).

Celiac disease patients can claim gluten-free foods as a medical expense. The necessary documents required from the physician as proof of celiac disease are associated with a fee. However, these forms are required to be completed only once. For tax filing, the cost of the gluten-free food and the comparable gluten-containing product need to be inventoried and accompanied by receipts. The difference between the two totals represents the allowable medical expense. However, if only one person in the family has celiac disease, and the foodstuffs are purchased for family dinners, only the portion consumed by the patient is eligible. The medical expenses are tallied with other personal deductions and the final amount claimed depends on the claimant’s annual income (24). Reports from celiac disease patients from an online forum indicate that the process is arduous and requires the paid assistance of an accountant. The deduction amount is variable, but for one individual it was $600, which is a trivial amount compared with $60 spent a week on dried blueberries as a gluten-free ‘snack’ (25).

The side effects of celiac disease, such as diarrhea, headaches, fatigue, bloating and abdominal discomfort (6), likely increase an employee’s absence from work. However, no studies have been completed to provide a financial impact of celiac disease in the workforce.

REFERENCES

- 1.Hoffenberg EJ, MacKenzie T, Barriga KJ, et al. A prospective study of the incidence of childhood celiac disease. J Pediatr. 2003;143:308–14. doi: 10.1067/s0022-3476(03)00282-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Telega G, Bennet TR, Werlin S. Emerging new clinical patterns in the presentation of celiac disease. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 2008;162:164–8. doi: 10.1001/archpediatrics.2007.38. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Statistics Canada . Population estimates by sex and age group as of July 1, 2009, Canada. < www.statcan.gc.ca/daily-quotidien/091127/t091127b2-eng.htm> (Accessed April 11, 2011). [Google Scholar]

- 4.Silvester JA, Rashid M. Long-term follow-up of individuals with celiac disease: An evaluation of current practice guidelines. Can J Gastroenterol. 2007;21:557–64. doi: 10.1155/2007/342685. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Rashid M, Cranney A, Zarkadas M, et al. Celiac disease: Evaluation of the diagnosis and dietary compliance in Canadian children. Pediatrics. 2005;116:e754–9. doi: 10.1542/peds.2005-0904. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Dube C, Rostom A, Sy R, et al. The prevalence of celiac disease in average-risk and at-risk Western European populations: A systematic review. Gastroenterology. 2005;128:S57–S67. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2005.02.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Canadian Celiac Association About CCA. < www.celiac.ca/about.php> (Accessed April 11, 2011).

- 8.Lohi S, Mustalahti K, Kaukinen K, et al. Increasing prevalence of coeliac disease over time. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2007;26:1217–25. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2036.2007.03502.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Mustalahti K, Catassi C, Reunanen A, et al. The prevalence of celiac disease in Europe: Results of a centralized, international mass screening project. Ann Med. 2010;42:587–95. doi: 10.3109/07853890.2010.505931. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Sanders DS, Patel D, Stephenson TJ, et al. A primary care cross-sectional study of undiagnosed adult coeliac disease. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2003;15:407–13. doi: 10.1097/00042737-200304000-00012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Gillett PM, Gillett HR, Israel DM, et al. High prevalence of celiac disease in patients with type 1 diabetes detected by antibodies to endomysium and tissue transglutaminase. Can J Gastroenterol. 2001;15:297–301. doi: 10.1155/2001/640796. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Dickey W, Kearney N. Overweight in celiac disease: Prevalence, clinical characteristics, and effect of a gluten-free diet. Am J Gastroenterol. 2006;101:2356–9. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2006.00750.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Statistics Canada Table 102-0531 – Deaths, by cause, Chapter XI: K00 to K93, age group and sex, Canada, 2000–2007. CANSIM. < http://cansim2.statcan.gc.ca> (Acccessed April 11, 2011).

- 14.Ravikumara M, Nootigattu VK, Sandhu BK. Ninety percent of celiac disease is being missed. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 2007;45:497–9. doi: 10.1097/MPG.0b013e31812e5710. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Guideline for the diagnosis and treatment of celiac disease in children: Recommendations of the North American Society for Pediatric Gastroenterology, Hepatology and Nutrition. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 2005;40:1–19. doi: 10.1097/00005176-200501000-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Fu B. The most reliable testing option is also the most cost-effective. J Fam Pract (epub) 2006. p. 55.

- 17.2G Pharma Inc Do you have celiac disease? < http://celiachometest.com/> (Accessed April 11, 2011).

- 18.Canadian Institute for Health Information . The Cost of Acute Care Hospital Stays by Medical Condition in Canada: 2004–2005. Ottawa: Canadian Institute for Health Information; 2008. pp. 1–155. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Korponay-Szabo IR, Szabados K, Pusztai J, et al. Population screening for coeliac disease in primary care by district nurses using a rapid antibody test: Diagnostic accuracy and feasibility study. BMJ. 2007;335:1244–7. doi: 10.1136/bmj.39405.472975.80. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Freeman HJ. Pearls and pitfalls in the diagnosis of adult celiac disease. Can J Gastroenterol. 2008;22:273–80. doi: 10.1155/2008/905325. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Stevens L, Rashid M. Gluten-free and regular foods: A cost comparison. Can J Diet Pract Res. 2008;69:147–50. doi: 10.3148/69.3.2008.147. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Heart and Stroke Foundation of Canada Heart and Stroke Foundation’s Annual Report on Canadian Health. < www.newswire.ca/en/releases/archive/February2009/09/c6632.html> (Accessed February 9, 2009).

- 23.Health Canada Health Canada urges food manufacturers to label priority food allergens, gluten sources and added sulphites in the pre-publication period of the Food Allergen Labeling Regulatory Amendments. < www.hc-sc.gc.ca/fn-an/label-etiquet/allergen/guide_ligne_direct_indust-eng.php> (Accessed February 2, 2009).

- 24.Canada Revenue Agency Celiac disease – Medical expense. < www.cra-arc.gc.ca/tx/ndvdls/tpcs/ncm-tx/rtrn/cmpltng/ddctns/lns300-350/330/clc-eng.html> (Acccessed April 11, 2011).

- 25.Celiac Disease and Gluten-Free Forum. Canadian Tax Credit. < www.celiac.com/gluten-free/lofiversion/index.php/t37748.html> (Acccessed April 19, 2012).