Abstract

Angiotensin II contributes to myocardial tissue remodeling and interstitial fibrosis through NADPH oxidase-mediated generation of oxidative stress in the progression of heart failure. Recent data have suggested that nebivolol, a third-generation β-blocker, improves diastolic dysfunction by targeting nitric oxide (NO) and metabolic pathways that decrease interstitial fibrosis. We sought to determine if targeting NO would improve diastolic function in a model of tissue renin-angiotensin system overactivation. We used the transgenic (TG) (mRen2)27 rat, which overexpresses the murine renin transgene and manifests insulin resistance and left ventricular dysfunction. We treated 6- to 7-wk-old TG (mRen2)27 rats and age-matched Sprague-Dawley control rats with nebivolol (10 mg·kg−1·day−1) or placebo via osmotic minipumps for a period of 21 days. Compared with Sprague-Dawley control rats, TG (mRen2)27 rats displayed a prolonged diastolic relaxation time and reduced initial filling rate associated with increased interstitial fibrosis and left ventricular hypertrophy. These findings were temporally related to increased NADPH oxidase activity and subunits p47phox and Rac1 and increased total ROS and peroxynitrite formation in parallel with reductions in the antioxidant heme oxygenase as well as the phosphorylation/activation of endothelial NO synthase and PKB/Akt. Treatment with nebivolol restored diastolic function and interstitial fibrosis through increases in the phosphorylation of 5′-AMP-activated protein kinase, Akt, and endothelial NO synthase and reductions in oxidant stress. These results support that targeting NO with nebivolol treatment improves diastolic dysfunction through reducing myocardial oxidative stress by enhancing 5′-AMP-activated protein kinase and Akt activation of NO biosynthesis.

Keywords: insulin resistance, diastolic relaxation time, magnetic resonance imaging

elevations in systolic blood pressure (SBP) over time contribute to pressure-dependent left ventricular (LV) hypertrophy (LVH) and maladaptive tissue remodeling, which leads to heart failure (19, 21, 34, 53). The initial manifestations of heart failure are characterized by increases in interstitial fibrosis and diastolic dysfunction (34, 53). The reductions in initial filling rate (IFR) and increases in relaxation time that characterize diastolic dysfunction occur due to remodeling of the LV and are associated with alterations in the elastic properties driven by the development of interstitial fibrosis (38, 44). Inappropriate activation of the renin-angiotensin-aldosterone system (RAAS) plays a central role in blood pressure regulation as well as contributes to myocardial fibrosis through the generation of ROS (35, 37, 38, 43). These RAAS-induced increases in ROS are due to mitochondrial uncoupling and increased activation of NADPH oxidase (22, 40). Excess ROS contribute to reductions in bioavailable nitric oxide (NO) by the conversion of locally released NO to peroxynitritrite (ONOO−), a highly reactive species that contributes to lipid peroxidation (28, 45). NO is an essential component of endothelial function as well as several metabolic pathways that modulate growth and proliferation, such as 5′-AMP-activated protein kinase (AMPK) signaling pathways (15). Targeting NO to reduce oxidant stress and improve metabolic signaling has the potential to reduce myocardial fibrosis and to correct diastolic dysfunction (6).

β1-Adrenergic receptor blockade has been shown to improve contractile function, and recent data have suggested that nebivolol targets improvements in diastolic function in human and rodent models of heart failure (26, 49, 55). Nebivolol is a highly cardiac-selective β1-adrenergic receptor blocker that contributes to vasodilation by increasing bioavailable NO through its coupling to the β3-receptor subtype (13). It has been reported that nebivolol treatment leads to reductions in NADPH oxidase activity in the heart and vascular tissue (13, 32, 41, 43), and recent work has highlighted improvements in insulin metabolic signaling and enhancement in bioavailable NO in skeletal muscle (25) and kidney tissue (51) in a transgenic (TG) (mRen2)27 (Ren2) rat model. This Ren2 rat manifests tissue overexpression of the mouse renin gene and tissue ANG II with elevations in SBP, insulin resistance, and increases in myocardial oxidative stress and diastolic dysfunction (14, 50). The Ren2 rat provides a unique model to investigate the effects of nebivolol on hypertension/renin-angiotensin system (RAS)-induced diastolic dysfunction as a result of oxidative stress and impaired metabolic signaling. Thereby, we hypothesized that targeting reductions in myocardial interstitial fibrosis with nebivolol would correct myocardial diastolic dysfunction through improvements in metabolic signaling pathways by reducing NADPH oxidase activity and stimulation of AMPK and bioavailable NO.

METHODS

Animals and Treatments

Animal procedures were approved by the Animal Care Committees of the University of Missouri and housed according to National Institutes of Health guidelines. Male transgenic heterozygous (+/−) Ren2 and Sprague-Dawley (SD) rats were received at 5–6 wk of age from the Wake Forest University School of Medicine and Vascular Research Center (Winston-Salem, NC). Rats were randomly assigned to placebo (SD-C or Ren2-C) or nebivolol treatment (SD-N and Ren2-N) groups. Ren2-N and SD-N rats received 10 mg·kg−1·day−1 nebivolol released via an implanted osmotic minipump for 21 days (51). Insulin stimulation was performed by an intravenous injection of 2 units of insulin 5 min before euthanization to evaluate insulin-induced Akt activation.

SBP and LV Weight

Restraint conditioning was initiated on the day of initial blood pressure measurements. SBP was measured in triplicate on separate occasions throughout the day using the tail-cuff method (Student Oscillometric Recorder, Harvard Systems) before the initiation of treatment and on days 19 or 20 before euthanization. At autopsy, the LV plus septum was dissected free of the right ventricle, atria, and great vessels. The LV plus septum normalized to body weight is a commonly used index of LVH in nonobese rodent models.

In Vivo Cine-MRI

Noninvasive cine-MRI scans were performed on rats after treatment with nebivolol or vehicle using a 7-T/210-mm horizontal-bore MRI (Agilent, Palo Alto, CA) equipped with a 63-mm quad rupture detection radiofrequency coil, as previously described (55). Animals were weighed and anesthetized using 1.8–2.7% isoflurane on a nose cone nonrebreathing system supplying continuous oxygen. ECG and respiratory monitoring and gating were performed with a small animal monitoring system (SA Instruments, Stony Brook, NY). Warm air was circulated through the MRI bore to maintain body temperature. ECG/respiratory gated gradient echo sequences were acquired with 1-mm slice thickness and 65 × 45- and 45 × 45-mm2 field of views for the LV in long- and short-axis images, respectively. LV functional parameters were determined using a series of cine images of the LV in long-axis view acquired at 16 equally spaced time points throughout the entire cardiac cycle with a frame rate of 8–12 ms/frame. At each time point, the endocardial borders were traced to measure the LV chamber area using VnmrJ software (Agilent) by two experienced MRI readers. LV volumes (LVVs) at each phase were calculated with the following modified ellipsoid equation: LVV = 8A2/(3πL), where A is the endocardial area and L is the length of the LV long-axis chamber. The LVV curve was plotted as LVV versus time throughout a cardiac cycle, as shown in Fig. 1C.

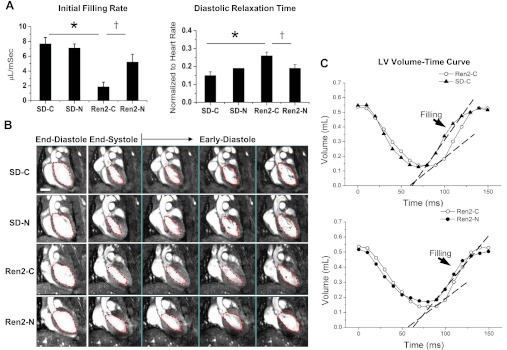

Fig. 1.

Nebivolol improves diastolic relaxation in the Ren2 heart. A: bar graph showing diastolic relaxation times normalized to heart rates and initial filling rates for the experimental groups. Sprague-Dawley (SD) and Ren2 rats were randomly assigned to placebo (SD-C or Ren2-C) or nebivolol treatment (SD-N and Ren2-N) groups. B: representative cine-MRI images showing the end-diastolic, end-systolic, and early diastole phases, as represented by frames 1, 7, and 8–10, respectively, of a total of 16 frames in a cardiac cycle. The middle bottom images show prolonged diastolic relaxation in the Ren2-C group compared with the SD-C group. The bottom images show the reduced diastolic relaxation time and increased initial filling rate in the Ren2-N group compared with the Ren2-C group. C: mean left ventricular (LV) volume-time curves for the Ren2-C and SD-C groups (top) and Ren2-N and Ren2-C groups (bottom). A mean R-R interval value is used for clarity. Diastolic filling phases are indicated by arrows. The slopes of the dashed lines represent the mean initial filling rates for each group. As shown, the initial filling rate was decreased for the Ren2-C group compared with the SD-C group and was improved after nebivolol treatemnet. Scale bar = 5 mm. *P < 0.05 vs. the SD-C group; †P < 0.05 vs. the Ren2-C group.

Septal wall thickness.

Septal wall thickness measurements were determined on the midventricular axial image immediately after the R wave and with an average of 5 measurements/heart.

LV systolic function.

LV stroke volume (SV) was calculated as follows: SV = EDV − ESV, where EDV is end-diastolic volume and ESV is end-systolic volume. LV ejection fraction (EF) was measured as follows: EF = SV/EDV × 100%. LV cardiac output (CO) was assessed as follows: CO = SV × HR, where HR is heart rate.

LV diastolic function.

First derivatives of LVV against time were calculated to extract the diastolic filling rates and relaxation time. Diastolic IFR was defined as the slope of the first four time points on the early diastolic curve (Fig. 1C). Diastolic peak filling rate (PFR) was defined as the maximum derivative of the LVV curve. Diastolic relaxation time (DRT) was defined as the time duration from the end of systolic phase to the peak filling phase. Normalized DRT, which is the ratio of DRT to the R-R interval, was used to compare LV diastolic relaxation among groups, where normalized DRT = [DRT × (HR /6,000)].

Myocardial Interstitial Fibrosis

Fixed paraffin sections of the LV were evaluated with Verhoeff-van Gieson (VVG) stain, which stains elastin (black), nuclei (blue-black), collagen (pink), and connective tissue (yellow), as previously described (14, 55). Briefly, 4-μm longitudinal and transvers sections of the LV were stained with VVG. Slides were blindly analyzed by one or two observers with a Nikon50i (Nikon, Tokyo, Japan) microscope. To keep uniformity and avoid error, each section was thoroughly checked. Five representative areas were captured with ×40 images from each section with a CoolSNAP cf camera (Roper Scientific Germany, Trenton, NJ). The areas and intensities of pink regions, which are indicative of interstitial fibrosis, were quantified on both transverse and longitudinal sections of the LV using MetaVue software (Molecular Devices, Sunnyvale, CA). The average grayscale intensity due to collagen was recorded. An average value of these intensities was determined for each animal.

Markers of Oxidative Stress

ROS formation.

Myocardial ROS was measured by chemiluminescense as previously described (55). Briefly, LV tissue sections were homogenized and centrifuged, and supernatants (whole homogenate) were then removed and placed on ice. Whole homogenate (100 μl) was added to 1.4 ml of 50 mM phosphate (KH2PO4) buffer (150 mM sucrose, 1 mM EGTA, 5 μM lucigenin, and 100 μM NADPH; pH 7.0) in dark-adapt counting vials. After dark adaptation, samples were counted on a luminometer, and all counts were averaged. Samples were then normalized to total protein in the whole homogenate.

3-Nitrotyrosine.

Briefly, 5-μm sections of the LV were incubated with 1:150 rabbit polyclonal anti-3-nitrotyrosine (3-NT) antibody overnight (Chemicon, Temecula, CA) as previously described (14, 55). Sections were then washed and incubated with secondary antibodies (biotinylated linked and streptavidin-HRP conjugated) for 30 min each. After several rinses with Tris-buffered saline-Tween 20, diaminobenzidine was applied for 8 min, and sections were then rinsed several times with distilled water, stained with hematoxylin for 80 s, dehydrated, and mounted with a permanent media. Slides were inspected under a bright-field (50i, Nikon) microscope, and ×40 images from each section were captured with a CoolSNAP cf camera. Signal intensities of brownish color, which is indicative of the 3-NT level, were quantified by MetaVue software.

NADPH oxidase activity.

NADPH oxidase activity was determined in LV plasma membrane fractions as previously described (14, 50, 55). Briefly, plasma membrane fractions were incubated with NADPH (100 mmol/l) at 37°C. Total enzyme oxidase activity was determined by measuring the conversion of Radical Detector (Cayman Chemical, Ann Arbor, MI) in the absence and presence of the NADPH inhibitor diphenyleneiodonium sulfate (500 μmol/l) using spectrophotometric (450 nm) techniques.

Immunostaining.

LV sections were immunostained for Rac1, p47phox, phosphorylated (p)-Akt (Thr308), p-endothelial NO synthase (eNOS; Ser1177), and heme oxygenase (HO) and quantitated as previously described (14, 50, 55). Briefly, 4-μm paraffin-embedded transverse sections of the LV from different treatments were dewaxed in citriSolv, rehydrated in ethanol series, and antigen retrieved in sodium citrate buffer at 95°C. Sections were then incubated with mouse anti-Rac1 antibody (1:200) in 10-fold diluted blocker and goat anti-p47phox (1:100), mouse anti-p-eNOS (Ser1177; 1:50), rabbit anti-p-Akt (Thr308; 1:50), and rabbit anti-HO (1:75) antibodies overnight at room temperature. Sections were washed, incubated with 1:300 of the appropriate secondary antibodies conjugated to a far red dye for 4 h, and viewed with a biphoton confocal laser scanning microscope. Images were acquired and signal intensities were measured by MetaVue software as average grayscale intensities.

Quantification of AMPK and p-AMPK by Western blot analysis.

Total AMPK and p-AMPK were analyzed by Western blot analysis. Protein concentrations of tissue homogenates were measured as previously described (55). Samples (40 μg/lane) were separated by SDS-PAGE and transferred to polyvinylidene difluoride membranes (Bio-Rad Laboratories). Blots were incubated overnight at 4°C with primary antibodies against AMPK and p-AMPK (1:1,000 dilution, Cell Signaling Technology). After a rinse, blots were incubated with secondary antibodies (1:5,000 dilution of each antibody) for 1 h at room temperature. Bands were visualized by chemiluminescence, and images were recorded using a Bio-Rad ChemiDoc XRS image-analysis system. Quantitation of phosphorylated protein band density, normalized to the density of total protein for each sample, was performed using Image Lab (Bio-Rad).

Statistical Analysis

All values are expressed as means ± SE. Statistical analyses were performed with Sigma Stat (Aspire Software, Ashburn, VA) using Student's t-tests or ANOVA with Fisher's least-significant-difference test for post hoc comparisons. Significance was accepted at P < 0.05.

RESULTS

Experimental Parameters

As previously described (25, 51), SBP was elevated in the Ren2-C group compared with the SD-C group (207 ± 8 vs. 144 ± 8 mmHg, P < 0.05). Moreover, there was increase in the insulin resistance index in the vehicle-treated Ren2 model compared with the SD-C group at the end of the treatment period. Treatment with nebivolol in the Ren2 model led to reductions in SBP (183 ± 4 mmHg, P < 0.05) and the insulin resistance index compared with age-matched controls over 3 wk of treatment (51) but had no impact on total body weight.

Nebivolol Improves Diastolic Relaxation But Not Hypertrophy in the Ren2 Heart

LV systolic and diastolic functions were determined using in vivo cardiac-MRI after 2 wk of treatment with placebo or nebivolol (Table 1). There were increases in DRT along with reductions in IFR as indexes of diastolic function in the Ren2-C group compared with the SD-C group (P < 0.01; Fig. 1, A–C). Treatment with nebivolol over 2 wk led to reductions in DRT as well as increases in IFR (P < 0.05). There were no observable changes in systolic function and body weight in the Ren2-C group compared with the SD-C group, nor was there a treatment effect.

Table 1.

Effects of nebivolol on in vivo cardiac function in Ren2 and SD rats evaluated by cine-MRI

| Parameter | SD-C Group | SD-N Group | Ren2-C Group | Ren2-N Group |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sample size | 5 | 5 | 5 | 6 |

| Body weight, g | 310 ± 14 | 322 ± 23 | 273 ± 16 | 266 ± 16 |

| Heart rate and left ventricular morphology | ||||

| Heart rate, beats/min | 328 ± 14 | 342 ± 18 | 386 ± 14* | 352 ± 9 |

| Septal wall thickness, mm | 1.49 ± 0.09 | 1.46 ± 0.03 | 1.86 ± 0.05 | 1.98 ± 0.05 |

| End-diastolic volume, μl | 570 ± 24 | 592 ± 34 | 544 ± 52 | 507 ± 47 |

| End-systolic volume, μl | 123 ± 17 | 124 ± 16 | 132 ± 25 | 152 ± 25 |

| Systolic indexes | ||||

| Stroke volume, μl | 448 ± 15 | 469 ± 23 | 412 ± 30 | 354 ± 33 |

| Cardiac output, ml/min | 147 ± 5 | 160 ± 9 | 158 ± 7 | 125 ± 12 |

| Ejection fraction, % | 79 ± 2 | 79 ± 2 | 77 ± 3 | 71 ± 4 |

| Diastolic indexes | ||||

| Initial filling rate, μl/ms | 7.69 ± 0.86 | 7.12 ± 0.54 | 1.88 ± 0.6* | 5.22 ± 1.06† |

| Peak filling rate, μl/ms | 9.90 ± 1.17 | 11.40 ± 1.16 | 12.05 ± 0.64 | 9.89 ± 1.06 |

| Diastolic relaxation time, ms | 28.0 ± 3.7 | 32.9 ± 1.7 | 40.3 ± 3.1* | 31.8 ± 3.4 |

| Normalized diastolic relaxation time (to R-R interval) | 0.15 ± 0.02 | 0.19 ± 0.00 | 0.26 ± 0.02* | 0.19 ± 0.02† |

Data are means ± SE. Sprague-Dawley (SD) and mRen2 rats were randomly assigned to placebo (SD-C or Ren2-C) or nebivolol treatment (SD-N and Ren2-N) groups.

P < 0.05 vs. the SD-C group;

P < 0.05 vs. the Ren2-C group.

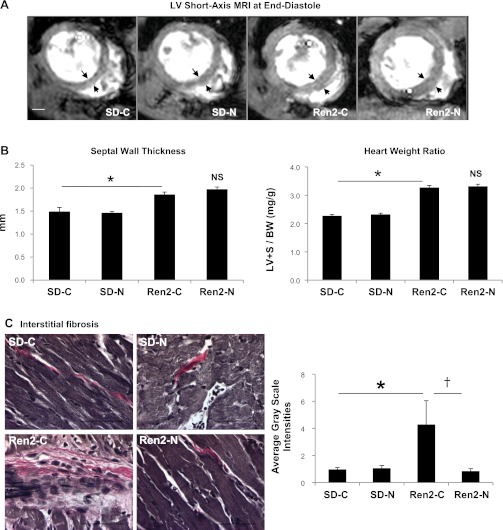

Commensurate with the observed changes in diastolic function, there were increases in measures of LV mass. There were increases in interventricular septal wall thickness on MRI as well as LV weight normalized to total body weight in Ren2-C rats compared with SD-C rats (P < 0.01; Fig. 2, A and B). Despite reducing SBP, nebivolol treatment did not improve septal wall thickness or LV weight in the Ren2-N group.

Fig. 2.

Nebivolol reduces myocardial fibrosis but not hypotrophy in the Ren2 heart. A: representative left midventricular short-axis MRI images, acquired at the end-diastolic phase, showing the thickened septum and posterior walls in the Ren2-C and Ren2-N groups compared with the SD-C and SD-N groups. Scale bar = 2 mm. B: bar graph showing septal wall thickness (left) and LV plus septum myocardial mass normalized to body weight (LV+S/BW; right) for the experimental groups. NS, not significant. C, left: light micrographs showing representative LV sections stained with Verhoeff-van Gieson stain, which stains collagen pink. Scale bar = 50 μm. Right, bar graph showing that nebivolol attenuates the increased interstitial fibrosis in the Ren2-C myocardium. *P < 0.05 vs. the SD-C group; †P < 0.05 vs. the Ren2-C group.

Nebivolol Improves Interstitial Fibrosis in the Ren2 Heart

To determine whether the improvement in diastolic relaxation in nebivolol-treated Ren2 was attributable to fibrosis rather than hypertrophy, we evaluated myocardial fibrosis by VVG staining (for collagen). There were increases in interstitial fibrosis in the Ren2-C group compared with the SD-C group (P < 0.05). This increase in collagen content and interstitial fibrosis was reduced with nebivolol treatment in the Ren2-N group (Fig. 2C).

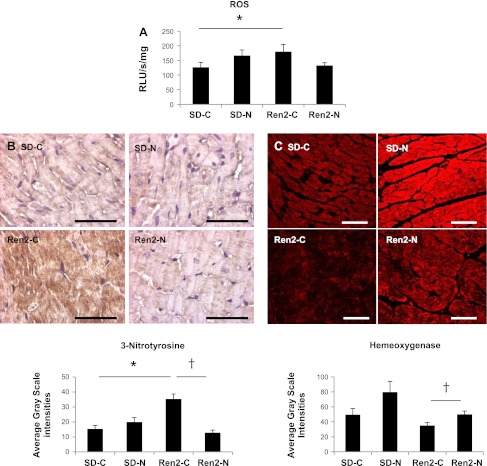

Nebivolol Reduces Oxidative Stress in the Ren2 Heart

An imbalance in redox status and “oxidant stress” contributes to the development of fibrosis. In this context, ROS are important signaling molecules that activate many redox signaling pathways, and nitrosylation of tyrosine residues (3-NT) can alter protein functions. There were increases in total ROS formation as well as 3-NT content in the Ren2-C group compared with the SD-C group (P < 0.05; Fig. 3, A and B). Treatment with nebivolol led to improvements in 3-NT content to a greater extent than total ROS formation. HO catalyzes a multistep reaction to release Fe(III) and the antioxidant biliverdin (5). There was a trend of reductions in HO compared with the SD-C group, which was significantly increased with nebivolol treatment in the Ren2-N group (P < 0.05; Fig. 3C).

Fig. 3.

Nebivolol improves oxidative stress in the Ren2 heart. A: bar graph demonstrating increased formation of ROS in the myocardium of the Ren2-C group relative to the SD-C group (P < 0.05). Nebivolol reduced ROS formation in the Ren2-N myocardium compared with the Ren2-C myocardium (P = 0.05). RLU, relative light units. B, top: representative photomicrographs showing 3-nitrotyrosine (3-NT) immunostaining in the myocardium of Ren2 and SD rats. Bottom, bar graph showing average grayscale intensity measures of the 3-NT staining, demonstrating that nebivolol reduced the increase in 3-NT levels in the Ren2 myocardium. Scale bar = 50 μm. *P < 0.05 vs. the SD-C group; †P < 0.05 vs. the Ren2-C group. C, top: representative confocal images showing immunofluorescence for heme oxygenase (HO) immunostaining in the myocardium of Ren2 and SD rats. Bottom, bar graph showing average grayscale intensity measures of the HO staining, demonstrating that nebivolol increased levels of HO in the Ren2 myocardium. Scale bar = 50 μm. †P < 0.05 vs. the Ren2-C group.

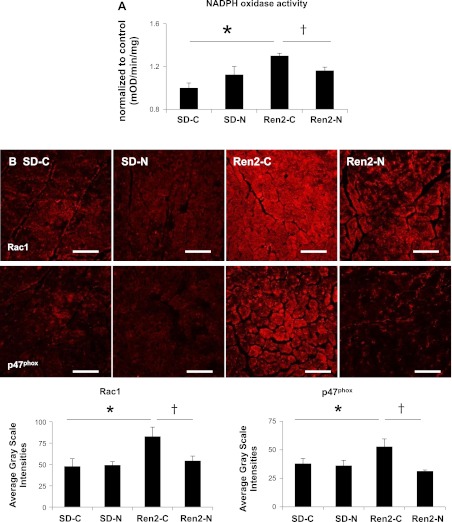

Nebivolol Reduces NADPH Oxidase in the Ren2 Heart

NADPH oxidase is a major source of ROS in the myocardium, and it generates ROS through the assembly of a multisubunit protein complex including the cytoplasmic subunit p47phox and the GTP-binding protein Rac1. There were increases in total NADPH oxidase activity in the Ren2-C myocardium compared with the SD-C myocardium (P < 0.05; Fig. 4A), and this increased activity was attenuated by nebivolol treatment for 3 wk (P < 0.05). Commensurate with total enzyme activity, there were increases in NADPH oxidase subunits p47phox and Rac1 in Ren2 rats, which were similarly improved with nebivolol treatment (Fig. 4B).

Fig. 4.

Nebivolol reduces NADPH oxidase activity and NADPH oxidase subunit protein expression in the Ren2 heart. A: bar graph demonstrating increased NADPH oxidase activity in the myocardium of Ren2-C rats relative to SD-C rats (P < 0.05). Nebivolol reduced NADPH oxidase activity in the Ren2-N myocardium compared with the Ren2-C myocardium (P < 0.05). OD, optical density units. B, top: representative confocal images showing immunofluorescence for the NADPH oxidase subunits Rac1 (left) and p47phox (right). Bottom, bar graphs showing average grayscale intensities for the NADPH oxidase subunits Rac1 (left) and p47phox (right). *P < 0.05 vs. the SD-C group; †P < 0.05 vs. the Ren2-C group.

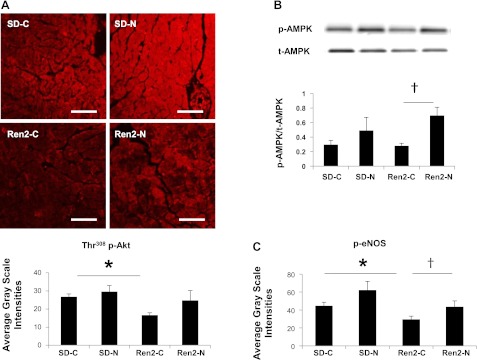

Nebivolol Increases p-eNOS in the Ren2 Heart

Nebivolol treatment resulted in a substantial reduction in 3-NT content, a marker for ONOO− formation. The ONOO− radical is a highly ROS that can be formed endogenously by the interaction of NO and O2−. Thus, to ascertain whether nebivolol induces eNOS activation in the Ren2 heart, Ser1177 phosphorylation of eNOS (activation) was measured. p-eNOS (Ser1177) was diminished in the Ren2-C group compared with the SD-C group (P < 0.05) and was significantly increased with nebivolol treatment in the Ren2 myocardium (P < 0.05; Fig. 5A).

Fig. 5.

Nebivolol enhances insulin-induced Akt activation, phosphorylation of 5′-AMP-activated protein kinase (AMPK), and phosphorylation of endothelial nitric oxide synthase (eNOS) in the Ren2 heart. A: representative confocal images (top) showing phosphorylated (p-)Akt (Thr308) immunofluorescence in the myocardium of Ren2 and SD rats with representative measures (bottom). Scale bar = 50 μm. *P < 0.05 vs. the SD-C group; †P < 0.05 vs. the Ren2-C group. B, top: representative Western blots showing p-AMPK and total (t-)AMPK bands. Bottom, bar graph showing the ratio of p-AMPK to t-AMPK, demonstrating that nebivolol enhanced AMPK phosphorylation in the myocardium of Ren2 rats. †P < 0.05 vs. the Ren2-C group. C: bar graph showing average grayscale intensity measures of p-eNOS (Ser1177) immunofluorescence. *P < 0.05 vs. the SD-C group; †P < 0.05 vs. the Ren2-C group.

Nebivolol Improves Insulin-Induced Akt Activation in the Ren2 Heart

There were decreases in p-Akt (Thr308) in the Ren2-C heart compared with the SD-C heart (P < 0.05), and Akt activation was restored by nebivolol treatment in the Ren2 heart (P < 0.05; Fig. 5B).

Nebivolol Increases p-AMPK in the Ren2 Heart

Next, we sought to determine whether nebivolol treatment could increase AMPK activation. While there were no differences in p-AMPK (Thr172) over total AMPK in the Ren2-C group compared with the SD-C group, there was a substantial increase in p-AMPK after treatment with nebivolol for 3 wk (P < 0.05; Fig. 5C).

DISCUSSION

Herein, we demonstrated that nebivolol treatment reduced myocardial indexes of oxidative stress associated with increased tissue RAS in the Ren2 rat. Indeed, 3 wk of treatment with a cardioselective β-blocker substantially reduced NADPH oxidase activity, as previously reported in skeletal muscle (25) and kidney tissue (51). Nebivolol treatment also increased myocardial HO levels. Since HO catalyzes a multistep reaction to release Fe(III) and the antioxidant biliverdin (5), this may have contributed to the reduced myocardial ROS and 3-NT after treatment with the β-blocker. Ren2 heart tissue displayed reduced AMPK and eNOS activity as well as reduced insulin-mediated Akt activation. Significant increases in the levels of p-AMPK (Thr172), p-eNOS (Ser1177), and p-Akt (Thr308) (Fig. 5), indicative of stimulatory phosphorylation and activation of these proteins in the Ren2 myocardium after nebivolol treatment are consistent with our observations of improved insulin metabolic signaling, increased bioavailable NO, and reduced interstitial fibrosis in the Ren2 myocardium. Moreover, these effects of nebivolol treatment are consistent with the protective effects of nebivolol observed in the heart, skeletal muscle (25), and kidneys of Zucker obese rats (51). Our findings extend previous work from preclinical and clinical work suggesting that nebivolol improves heart failure associated with preserved EF, an important finding given the paucity of effectiveness of current treatment approaches for the correction of diastolic dysfunction (8, 13, 26, 41, 49, 55).

The finding in the present investigation of reduced filling rate and increases in diastolic relaxation of LV on cine-MRI are consistent with observations of diastolic dysfunction in this TG model (14, 50). Noninvasive cardiac MRI has superior spatial and temporal resolution that permits the visualization of the entire heart, enabling an accurate estimation of cardiac dimensions and volumes over time (1, 42, 48, 54, 55). Volume-time curves on cine-MRI provide a determination of filling rates derived from changes of LVV during early diastole and have demonstrated great accuracy compared with echocardiography in preclinical and clinical models (1, 17, 42). Although a faster frame rate is preferred to increase the accuracy of measurements, the present frame rate of 8–12 ms/frame is sufficient for the analysis of the heart in the rat, as shown in Fig. 1, B and C. In the present study, the diastolic function parameters were derived based on the estimation of LVV and HR. Therefore, we presented normalized DRT (to R-R interval; Table 1 and Fig. 1A) to eliminate effects on this parameter from variations of HR. We made the same treatment for IFR and PFR; the HRs did not show any effects on these results. Diastolic dysfunction is associated with deceased filling rates and increased diastolic relaxation. The presence of diastolic dysfunction is a critical prognosticator for the future loss of systolic function. That our findings occurred in a model of tissue RAS overactivation extends previous work on the impact of metabolic heart disease on the initiation and progression of heart failure (14, 50). Thereby, the finding that the RAS, when inappropriately activated, initiates changes in myocardial tissue relaxation complements previous work done in obese rodent models such as the Zucker obese rat and db/db mouse (54, 55). Furthermore, our observation that nebivolol improves diastolic function in this RAS-dependent model is novel.

Myocardial interstitial deposition of the extracellular matrix (ECM) is a critical remodeling event associated with functional alterations in diastolic relaxation. Our observation of interstitial fibrosis in the Ren2 heart with VVG staining, which demonstrates excess interstitial collagen deposition, further supports the relationship between interstitial fibrosis and diastolic dysfunction in this model. ANG II has been shown to enhance collagen deposition and contributes to stiffening of the myocardium, reductions in elasticity, and associated impairments in relaxation and filling (3, 19, 21, 27). This enhanced deposition of ECM proteins has also been observed in a variety of rodent models in which cardiac hypertrophy develops as a result of hypertension associated with the activation of the RAAS (34). The observation that hypertrophy occurred in parallel with interstitial fibrosis in the Ren2 heart further refines this relationship. However, our finding that nebivolol improved interstitial fibrosis but not hypertrophy is novel and suggests that this compound has a specific impact on metabolic signaling pathways that influence collagen turnover mechanisms.

Recent work has suggested that oxidative stress is associated with interstitial fibrosis in the progression of heart failure (44) through the generation of the superoxide anion by the enzyme complex NADPH oxidase (38). The balance between ROS production and elimination plays a key role in preserving cardiac function. In the present study, transgenic Ren2 rats exhibited increases in NADPH oxidase enzyme activity and expression of the subunits p47phox and Rac1 in the myocardium associated with reductions in the antioxidant HO and increases in ROS production, as determined by total ROS production and ONOO− formation. Our finding that nebivolol improved HO suggests that targeting bioavailable NO leads to improvements in antioxidant mechanisms. In this regard, the data suggest that NO stabilizes and increases HO expression in vascular smooth muscle cells and in the myocardium (7, 9). Moreover, an increase in ONOO− formation was observed in the Ren2 myocardium, which was significantly reduced by nebivolol treatment. Reduction in ONOO− formation in the Ren2 myocardium by nebivolol treatment appears to be particularly important in that superoxide may react with NO released by eNOS to generate ONOO−, further supporting a direct role for nebivolol in improving bioavailable NO, antioxidant mechanisms, and diastolic function. ONOO− is a potent oxidizing agent implicated in several pathologies. ONOO− can modify proteins by nitration of tyrosine residues, which modulate the catalytic activity of the enzyme or prevent protein phosphorylation of the OH moiety on the tyrosine residue. These modifications result in alterations of function and promote a biological effect (36). Recently, a proteomic approach identified a total of 48 putative cardiac proteins containing nitrotyrosine that undergo age-dependent protein tyrosine nitration (20). However, investigators recently have demonstrated that among these proteins, MnSOD, a key mitochondrial antioxidant enzyme, and sarco (endo)plasmic reticulum Ca2+-ATPase type 2 are nitrated at one or more tyrosine residues and implicated in different pathological condition, including diabetes, atherosclerosis, and ANG II-induced hypertension (52).

Recent work has suggested that hearts with hypertrophy due to pressure overload are characterized by alterations in AMPK activity (46). AMPK is a stress-activated protein kinase that works as a metabolic sensor of cellular ATP levels and is a critical intermediary in myocardial energetics. AMPK activation plays a cardioprotective role by improving LV function and survival in heart failure (2, 12). Alternatively, deficiency in AMPK has been shown to exacerbate cardiac hypertrophy and contractile dysfunction (47). There is increasing interest in the cross talk between NO and AMPK (23), a kinase that generally downregulates oxidant and fibrotic pathways. Previous studies have demonstrated that AMPK stimulates the production of endothelium-derived NO, and targeting activation of AMPK by pharmacological intervention reduces agonist-stimulated protein synthesis in cultured cardiac myocytes via an Akt-dependent pathway (16, 18, 33, 46), thereby suggesting that AMPK may be a critical energy modulator of interstitial fibrosis and LV function. Further work supports that AMPK enhances eNOS activity by direct Ser1177 phosphorylation and increases NO bioavailability (45). Our finding that nebivolol restored p-AMPK in the Ren2 rat support that nebivolol actions on NO may occur in an AMPK-dependent mechanism. Furthermore, our observation that insulin-stimulated p-Akt was improved with nebivolol suggests the cross talk with AMPK and Akt. AMPK is known to regulate insulin-dependent pathways in skeletal muscle and heart tissue (24). AMPK activation has also been shown to regulate insulin-dependent activation of PKB/Akt in cardiac tissue glucose uptake as well as maladaptive tissue remodeling (4, 11, 16, 29). In this context, recent reports have suggested that the activation of AMPK is dependent, in part, on ANG II activation of H2O2 production, suggesting that AMPK is a redox-sensitive kinase (4, 29).

The Ren2 model develops cardiac hypertrophy that leads to adaptive alterations in the level of the contractile filaments (56). The increase in β-myosin heavy chain expression (56) may partially be responsible for the observed LV diastolic dysfunction in the Ren2 heart. A small shift from the α- to β-myosin heavy chain isomer could cause functional dysfunctions or heart failure in the human heart (30) and animal models (48). However, the unique feature of this β-blocker, and what we have observed, is that nebivolol does not impact hypertrophy but rather corrects fibrotic abnormalities. The present work supports that nebivolol improves diastolic dysfunction by targeting NO and reducing myocardial oxidative stress, which decrease interstitial fibrosis. Future work is needed on exploring the other potential mechanisms of action of nebivolol, such as effects on sarcomere proteins, in improving heart function.

Limitations

Our data indicate that targeting increases in bioavailable NO using nebivolol may play a role in improving diastolic dysfunction in Ren-2 rats. It should be noted that while there is no direct evidence linking bioavailable NO to diastolic dysfunction, there are correlative data in humans suggesting that nebivolol improves diastolic function and reduces mortality in elderly patients with heart failure (10, 31, 49). However, further studies are required to elucidate this mechanism. Moreover, the observation that nebivolol led to modest reductions in weight deserves mention as traditional β-blockers promote modest weight gain. It is possible that putative β3-agonist properties of nebivolol mediate modest weight loss by inducing the transdifferentiation of white adipose tissue into brown adipose tissue. Indeed, in rodents and humans, β3-receptor agonists stimulate the oxidation of fats, reduce fat weight, improve insulin sensitivity, and spare lean body mass (39). However, we did not include a comparator to confirm that all the beneficial effects of nebivolol are through its ability to increase bioavailable NO and not via its β-blocking effect. Our data on weight loss in Ren-2 rats, although interesting, should also be explored further to determine weight loss may be mitigating a portion of this response. It is possible the modest weight loss contributed to the improvements in diastolic function.

Summary

In summary, our observations support that targeting NO improves diastolic function through AMPK/Akt and reduced NADPH oxidase generation of ROS and improved HO. Biochemical alterations are associated with interstitial fibrosis in this model of RAAS overactivation.

GRANTS

This work was supported by National Institutes of Health Grants R01-HL-73101 and R01-HL-107910 (to J. R. Sowers), R03-AG-040638 (to A. Whaley-Connell), and HL-051952 (to C. M. Ferrario). There was also support from Veterans Affairs Merit System Grant 0018 (to J. R. Sowers) as well as CDA-2 (to A. Whaley-Connell) and the ASN-ASP Junior Development Grant in Geriatric Nephrology (to A. Whaley-Connell) supported by a T. Franklin Williams Scholarship Award. Funding was also provided by Atlantic Philanthropies, Incorported, the John A. Hartford Foundation, the Association of Specialty Professors, and the American Society of Nephrology.

DISCLOSURES

J.R.S. received investigator-initiated support from the Forest Research Institute.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

Author contributions: L.M., L.P., A.T.W.-C., C.M.F., and J.R.S. conception and design of research; L.M., R.G., J.H., and M.Y. performed experiments; L.M., R.G., J.H., and M.Y. analyzed data; L.M., J.H., M.Y., L.P., A.T.W.-C., C.M.F., and J.R.S. interpreted results of experiments; L.M., R.G., J.H., L.P., and A.T.W.-C. prepared figures; L.M., R.G., M.Y., L.P., A.T.W.-C., C.M.F., and J.R.S. drafted manuscript; L.M., R.G., J.H., A.T.W.-C., C.M.F., and J.R.S. edited and revised manuscript; L.M., R.G., J.H., M.Y., L.P., A.T.W.-C., C.M.F., and J.R.S. approved final version of manuscript.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

Exceptional support was provided by the Veterans Affairs Biomolecular Imaging Center of the Harry S. Truman Veterans Affairs Hospital. The authors acknowledge the technical contributions of Rebecca Schneider, Nathan Rehmer, and Mona Garro as well as students Safwan Hyder and Bennett Krueger. The authors thank Brenda Hunter for assistance in preparing the manuscript.

REFERENCES

- 1. Amundsen BH, Ericsson M, Seland JG, Pavlin T, Ellingsen Ø, Brekken C. A comparison of retrospectively self-gated magnetic resonance imaging and high-frequency echocardiography for characterization of left ventricular function in mice. Lab Anim 45: 31–37, 2011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Beauloye C, Bertrand L, Horman S, Hue L. AMPK activation, a preventive therapeutic target in the transition from cardiac injury to heart failure. Cardiovasc Res 90: 224–233, 2011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Berk BC, Fujiwara K, Lehoux S. ECM remodeling in hypertensive heart disease. J Clin Invest 117: 568–575, 2007 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. de Oliveira UO, Belló-Kein A, de Oliveira AR, Kuchaski LC, Machado UF, Irigoyen MC, Schaan BD. Insulin alone or with captopril: effects on signaling pathways (AKT and AMPK) and oxidative balance after ischemia-reperfusion in isolated hearts. Fundam Clin Pharmacol; doi:10.1111/j.1472-8206.2011.00995.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Ding B, Gibbs PE, Brookes PS, Maines MD. The coordinated increased expression of biliverdin reductase and heme oxygenase-2 promotes cardiomyocyte survival: a reductase-based peptide counters β-adrenergic receptor ligand-mediated cardiac dysfunction. FASEB J 25: 301–313, 2011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Dixon LJ, Morgan DR, Hughes SM, McGrath LT, El-Sherbeeny NA, Plumb RD, Devine A, Leahey W, Johnston GD, McVeigh GE. Functional consequences of endothelial nitric oxide synthase uncoupling in congestive cardiac failure. Circulation 107: 1725–1728, 2003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Durante W, Kroll MH, Christodoulides N, Peyton KJ, Schafer AI. Nitric oxide induces heme oxygenase-1 gene expression and carbon monoxide production in vascular smooth muscle cells. Circ Res 80: 557–564, 1997 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Fang Y, Nicol L, Harouki N, Monteil C, Wecker D, Debunne M, Bauer F, Lallemand F, Richard V, Thuillez C, Mulder P. Improvement of left ventricular diastolic function induced by β-blockade: a comparison between nebivolol and metoprolol. J Mol Cell Cardiol 51: 168–176, 2011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Farhangkhoee H, Khan ZA, Mukherjee S, Cukiernik M, Barbin YP, Karmazyn M, Chakrabarti S. Heme oxygenase in diabetes-induced oxidative stress in the heart. J Mol Cell Cardiol 35: 1439–1448, 2003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Ghio S, Magrini G, Serio A, Klersy C, Fucili A, Ronaszeki A, Karpati P, Mordenti G, Capriati A, Poole-Wilson PA, Tavazzi L. Effects of nebivolol in elderly heart failure patients with or without systolic left ventricular dysfunction: results of the SENIORS echocardiographic substudy. Eur Heart J 27: 562–568, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Ginion A, Auquier J, Benton CR, Mouton C, Vanoverschelde JL, Hue L, Horman S, Beauloye C, Bertrand L. Inhibition of the mTOR/p70S6K pathway is not involved in the insulin-sensitizing effect of AMPK on cardiac glucose uptake. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 301: H469–H477, 2011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Gundewar S, Calvert JW, Jha S, Toedt-Pingel I, Ji SY, Nunez D, Ramachandran A, Anaya-Cisneros M, Tian R, Lefer DJ. Activation of AMP-activated protein kinase by metformin improves left ventricular function and survival in heart failure. Circ Res 104: 403–411, 2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Gupta S, Wright HM. Nebivolol: a highly selective β1-adrenergic receptor blocker that causes vasodilation by increasing nitric oxide. Cardiovasc Ther 26: 189–202, 2008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Habibi J, DeMarco VG, Ma L, Pulakat L, Rainey WE, Whaley-Connell A, Sowers JR. Mineralocorticoid receptor blockade improves diastolic function independent of blood pressure reduction in transgenic model of RAAS overexpression. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 300: H1484–H1491, 2011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Harrison DG. Cellular and molecular mechanisms of endothelial cell dysfunction. J Clin Invest 100: 2153–2157, 1997 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Hwang YP, Kim HG, Hien TT, Jeong MH, Jeong TC, Jeong HG. Puerarin activates endothelial nitric oxide synthase through estrogen receptor-dependent PI3-kinase and calcium-dependent AMP-activated protein kinase. Toxicol Appl Pharmacol 257: 48–58, 2011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Ibrahimz el-SH, Miller AB, White RD. The relationship between aortic stiffness and E/A filling ratio and myocardial strain in the context of left ventricular diastolic dysfunction in heart failure with normal ejection fraction: insights from magnetic resonance imaging. Magn Reson Imaging 29: 1222–1234, 2011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Kahn BB, Alquier T, Carling D, Hardie DG. AMP-activated protein kinase: ancient energy gauge provides clues to modern understanding of metabolism. Cell Metab 1: 15–25, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Kane GC, Karon BL, Mahoney DW, Redfield MM, Roger VL, Burnett JC, Jr, Jacobsen SJ, Rodeheffer RJ. Progression of left ventricular diastolic dysfunction and risk of heart failure. JAMA 306: 856–63, 2011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Kanski J, Behring A, Pelling J, Schoneich C. Proteomic identification of 3-nitrotyrosine-containing rat cardiac proteins: effects of biological aging. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 288: H371–H381, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Kitzman DW, Little WC, Brubaker PH, Anderson RT, Hundley WG, Stewart KP, Marburger CT, Brosnihan B, Morgan TM, Wesley DJ. Pathophysiological characterization of isolated diastolic heart failure in comparison to systolic heart failure. JAMA 288: 2144–2150, 2002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Li JM, Gall NP, Grieve DJ, Chen M, Shah AM. Activation of NADPH oxidase during progression of cardiac hypertrophy to failure. Hypertension 40: 477–484, 2002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Lira VA, Soltow QA, Long JHD, Betters JL, Sellman JE, Criswell DS. Nitric oxide increases GLUT4 expression and regulates AMPK signaling in skeletal muscle. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab 293: E1062–E1068, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Long YC, Cheng Z, Copps KD, White MF. Insulin receptor substrates Irs1 and Irs2 coordinate skeletal muscle growth and metabolism via the Akt and AMPK pathways. Mol Cell Biol 31: 430–441, 2011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Manrique C, Lastra G, Habibi J, Pulakat L, Schneider R, Durante W, Tilmon R, Rehmer J, Hayden MR, Ferrario CM, Whaley-Connell A, Sowers JR. Nebivolol improves insulin sensitivity in the TGR(Ren2)27 rat. Metabolism 60: 1757–1766, 2011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Marazzi G, Volterrani M, Caminiti G, Iaia L, Massaro R, Vitale C, Sposato B, Mercuro G, Rosano G. Comparative long term effects of nebivolol and carvedilol in hypertensive heart failure patients. J Card Fail 17: 703–709, 2011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Martos R, Baugh J, Ledwidge M, O'Loughlin C, Conlon C, Patle A, Donnelly SC, McDonald K. Diastolic heart failure: evidence of increased myocardial collagen turnover linked to diastolic dysfunction. Circulation 115: 888–895, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Munzel T, Daiber A, Ullrich V, Mulsch A. Vascular consequences of endothelial nitric oxide synthase uncoupling for the activity and expression of the soluble guanylyl cyclase and the cGMP-dependent protein kinase. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol 25: 1551–1557, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Nagata D, Takeda R, Sata M, Satonaka H, Suzuki E, Nagano T, Hirata Y. AMP-activated protein kinase inhibits angiotensin II-stimulated vascular smooth muscle cell proliferation. Circulation 110: 444–451, 2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Nakao K, Minobe W, Roden R, Bristow MR, Leinwand LA. Myosin heavy chain gene expression in human heart failure. J Clin Invest 100: 2362–2370, 1997 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Nodari S, Metra M, Dei CL. Beta-blocker treatment of patients with diastolic heart failure and arterial hypertension. A prospective, randomized, comparison of the long-term effects of atenolol vs nebivolol. Eur J Heart Fail 5: 621–627, 2003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Oelze M, Daiber A, Brandes RP, Hortmann M, Wenzel P, Hink U, Schulz E, Mollnau H, von Sandersleben A, Kleschyov AL, Mülsch A, Li H, Förstermann U, Münzel T. Nebivolol inhibits superoxide formation by NADPH oxidase and endothelial dysfunction in angiotensin II-treated rats. Hypertension 48: 677–684, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Ramamurthy S, Ronnett GV. Developing a head for energy sensing: AMP-activated protein kinase as a multifunctional metabolic sensor in the brain. J Physiol 574: 85–93, 2006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Redfield MM. Understanding “diastolic” heart failure. N Engl J Med 350: 1930–1931, 2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Sawyer DB, Siwik DA, Xiao L, Pimentel DR, Singh K, Colucci WS. Role of oxidative stress in myocardial hypertrophy and failure. J Mol Cell Cardiol 34: 379–388, 2002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Schopfer FJ, Baker PRS, Freeman BA. NO-dependent protein nitration: a cell signaling event or an oxidative inflammatory response? Trends Biochem Sci 28: 646–654, 2003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Sciarretta S, Paneni F, Palano F, Chin D, Tocci G, Rubattu S, Volpe M. Role of the renin-angiotensin-aldosterone system and inflammatory processes in the development and progression of diastolic dysfunction. Clin Sci (Lond) 116: 467–477, 2009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Shahbaz AU, Sun Y, Bhattacharya SK, Ahokas RA, Gerling IC, McGee JE, Weber KT. Fibrosis in hypertensive heart disease: molecular pathways and cardioprotective strategies. J Hypertens 28, Suppl 1: S25–S32, 2010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Solak Y, Atalay H. Nebivolol in the treatment of metabolic syndrome: making the fat more brownish. Med Hypotheses 74: 614–615, 2010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Sorescu D, Griendling KK. Reactive oxygen species, mitochondria, and NAD(P)H oxidases in the development and progression of heart failure. Congest Heart Fail 8: 132–140, 2002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Sorrentino SA, Doerries C, Manes C, Speer T, Dessy C, Lobysheva I, Mohmand W, Akbar R, Bahlmann F, Besler C, Schaefer A, Hilfiker-Kleiner D, Lüscher TF, Balligand JL, Drexler H, Landmesser U. Nebivolol exerts beneficial effects on endothelial function, early endothelial progenitor cells, myocardial neovascularization, and left ventricular dysfunction early after myocardial infarction beyond conventional β1-blockade. J Am Coll Cardiol 57: 601–611, 2011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Stuckey DJ, Carr CA, Tyler DJ, Clarke K. Cine-MRI versus two-dimensional echocardiography to measure in vivo left ventricular function in rat heart. NMR Biomed 21: 765–772, 2008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Sun Y, Ramires FJA, Zhou G, Ganjam VK, Weber KT. Fibrous tissue and angiotensin II. J Mol Cell Cardiol 29: 2001–2012, 1997 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Swynghedauw B. Molecular mechanisms of myocardial remodeling. Physiol Rev 79: 215–262, 1999 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Takimoto E, Kass DA. Role of oxidative stress in cardiac hypertrophy and remodeling. Hypertension 49: 241–248, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Tian R, Musi N, D'Agostino J, Hirshman MF, Goodyear LJ. Increased adenosine monophosphate-activated protein kinase activity in rat hearts with pressure-overload hypertrophy. Circulation 104: 1664–1669, 2001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Turdi S, Fan X, Li J, Zhao J, Huff AF, Du M, Ren J. AMP-activated protein kinase deficiency exacerbates aging-induced myocardial contractile dysfunction. Aging Cell 9: 592–606, 2010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Tsika RW, Ma L, Kehat I, Schramm C, Simmer G, Morgan B, Fine DM, Hanft LM, McDonald KS, Molkentin JD, Krenz M, Yang S, Ji J. TEAD-1 overexpression in the mouse heart promotes an age-dependent heart dysfunction. J Biol Chem 285: 13721–35, 2010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. van Veldhuisen DJ, Cohen-Solal A, Böhm M, Anker SD, Babalis D, Roughton M, Coats AJ, Poole-Wilson PA, Flather MD; SENIORS Investigators Beta-blockade with nebivolol in elderly heart failure patients with impaired and preserved left ventricular ejection fraction: data From SENIORS (Study of Effects of Nebivolol Intervention on Outcomes and Rehospitalization in Seniors With Heart Failure). J Am Coll Cardiol 53: 2150–2158, 2009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Whaley-Connell A, Govindarajan G, Habibi J, Hayden MR, Cooper SA, Wei Y, Ma L, Qazi M, Karuparthi PR, Stump C, Ferrario C, Sowers JR. Angiotensin-II mediated oxidative stress promotes myocardial tissue remodeling in the transgenic TG (mRen2) 27 Ren2 rat. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab 293: E355–E363, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Whaley-Connell A, Habibi J, Johnson M, Tilmon R, Rehmer N, Rehmer J, Wiedmeyer C, Ferrario CM, Sowers JR. Nebivolol reduces proteinuria and renal NADPH oxidase-generated reactive oxygen species in the transgenic Ren2 rat. Am J Nephrol 30: 354–360, 2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Xu S, Ying J, Jiang B, Guo W, Adachi T, Sharov V, Lazar H, Menzoian J, Knyushko TV, Bigelow D, Schöneich C, Cohen RA. Detection of sequence-specific tyrosine nitration of manganese SOD and SERCA in cardiovascular disease and aging. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 290: H2220–H2227, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Yu CM, Lin H, Yang H, Kong SL, Zhang Q, Lee SW. Progression of systolic abnormalities in patients with “isolated” diastolic heart failure and diastolic dysfunction. Circulation 105: 1195–1201, 2002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Zhang H, Morgan B, Potter BJ, Ma L, Dellsperger KC, Ungvari Z, Zhang C. Resveratrol improves left ventricular diastolic relaxation in type 2 diabetes by inhibiting oxidative/nitrative stress: in vivo demonstration with magnetic resonance imaging. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 299: H985–H994, 2010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Zhou X, Ma L, Habibi J, Whaley-Connel AT, Hayden MR, Tilmon RD, Brown AN, DeMarco VG, Sowers JR. Nebivolol improves diastolic dysfunction and myocardial tissue remodeling through reductions in oxidative stress in the Zucker obese rat. Hypertension 55: 880–888, 2010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Zobel C, Zavidou-Saroti P, Bölck B, Brixius K, Reuter H, Frank K, Diedrichs H, Müller-Ehmsen J, Bloch W, Schwinger RH. Altered tension cost in (TG(mREN-2)27) rats overexpressing the mouse renin gene. Eur J Appl Physiol 99: 121–132, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]