Abstract

A long-standing critique of adolescent employment is that it engenders a precocious maturity of more adult-like roles and behaviors, including school disengagement, substance use, sexual activity, inadequate sleep and exercise, and work-related stress. Though negative effects of high-intensity work on adolescent adjustment have been found, little research has addressed whether such work experiences are associated with precocious family formation behaviors in adolescence, such as sexual intercourse, pregnancy, residential independence, and union formation. Using data from the National Longitudinal Study of Adolescent Health, we find that teenagers who spend long hours on the job during the school year are more likely to experience these family formation behaviors earlier than youth who work moderately or not at all.

A long-standing concern with adolescent employment is that it engenders a precocious maturity of more adult-like roles and problem behaviors, including school disengagement and dropout, licit and illicit drug use, sexual activity, inadequate sleep and exercise, and work-related stress (Bachman & Schulenberg, 1993; Greenberger & Steinberg, 1986; Newcomb & Bentler, 1988). Negative effects of paid work intensity (i.e., number of hours worked per week during the school year) on adolescent adjustment and achievement have been well documented (see Staff, Messersmith, & Schulenberg, 2009 for a recent review), though little research has addressed whether adolescent work experiences are associated with family formation behaviors, and if so, what explains these associations. In this paper, we address this gap by examining the link between adolescents’ paid work and precocious family formation behaviors.

Why might there be a link between adolescent work experiences and precocious family formation behaviors? Teenage workers may engage in early family formation behaviors if they work with older employees, if working compromises their school success or socioeconomic ambitions, if working leads to greater autonomy from parents, or if paid work schedules facilitate unsupervised socializing with peers. Work effects on precocious family formation behaviors may also depend on the degree to which adolescents are invested in paid work. Existing research on teenage employment has shown detrimental effects to be focused primarily among youth working intensively (i.e., more than 20 hours per week during the school year). For instance, teenagers who work intensively during the school year, when compared to youth who limit their work hours, are more likely to perform poorly in school, engage in substance use and other problem behaviors, and spend more time dating and in unsupervised leisure activities (Lee & Staff, 2007; Marsh & Kleitman, 2005; McMorris & Uggen, 2000; Monahan, Lee, & Steinberg, 2011; Mortimer, 2003; Safron, Schulenberg, & Bachman, 2001; Staff, Osgood, Schulenberg, Bachman, & Messersmith, 2010). Extending such findings to our topic, adolescents who spend long hours on the job might be more likely than their moderately working peers to engage in precocious family formation behaviors.

Furthermore, this relationship may vary depending on the type of family formation behavior examined. For this reason, we consider the association between paid work and the timing of a broad range of family formation behaviors in adolescence, including sexual initiation, pregnancy, residential independence, and union formation. We use data from the National Longitudinal Study of Adolescent Health (Add Health), a large, nationally representative data set, which allows us to consider family formation behaviors that are uncommon in adolescence, such as cohabitation, marriage, and residential independence. In addition, we control for a number of factors in an attempt to uncover explanations for the associations between paid work and precocious family formation behaviors in adolescence, including sociodemographic background and relationship history, as well as measures of problem behaviors, unstructured socializing, parental monitoring, school engagement and dropout, and friends’ substance use.

Teenage Employment, Sexual Initiation, and Family Formation

For many reasons, early experiences in paid work can be developmentally beneficial. For instance, early work experiences provide opportunities for young people to learn about the world of work and gain vocational skills and positive work ethics from adult mentors (Coleman et al., 1974; National Research Council, 1998). Adult supervisors and coworkers can provide vocational guidance by teaching young workers valuable job-related skills, by facilitating connections to adult supervisors and coworkers, or by providing references for future employment opportunities. Studies have shown that skill utilization and learning opportunities on the job promote the development of occupational values in adolescence, improve relationships with parents and peers, reduce problem behaviors, and provide long-term vocational benefits in young adulthood (Mortimer, 2003; Mortimer, Pimentel, Ryu, Nash, & Lee, 1996; Mortimer & Shanahan, 1994; Ruhm, 1997; Staff & Uggen, 2003; Wright & Cullen, 2004). In addition to the benefits of positive role models and early training opportunities, early work experiences may also provide young workers with valuable opportunities to learn how to be responsible, independent, and trustworthy, how to conduct oneself in an interview, and how to interact with customers and other coworkers (Coleman et al., 1974).

Though social scientists have noted the many vocational and developmental benefits of adolescent employment (Coleman et al., 1974; National Research Council, 1998), some scholars have expressed concern that employed adolescents, particularly those who spend long hours on the job, may take on precocious family roles and behaviors as well, such as sex initiation, pregnancy, union formation, and residence away from the parental home, before they are ready for these more adult-like roles and responsibilities (Greenberger & Steinberg, 1986). The problem behaviors associated with more intensive paid work involvement in adolescence thus represent a syndrome of precocious adult-like identity formation, influenced by prior orientations and behaviors (Bachman & Schulenberg, 1993). For instance, according to problem behavior theory (Jessor & Jessor, 1977), the coalescence of precocious work and family roles and behaviors in adolescence is a reflection of transition proneness, or variation in the young person’s desire to act like an adult. Precocious development theory (Newcomb & Bentler, 1988) posits that adolescents who exhibit problem behaviors (i.e., substance use, delinquency, school misconduct) are more likely to drop out of school and acquire a job, leave the parental home, establish residential independence, and cohabit or marry because these more adult-like social environments offer fewer restrictions on their problem behaviors. From each of these theoretical perspectives, we can hypothesize a relationship between intensive work hours and precocious family formation behaviors.

Yet, little prior research has examined the relationships between teenagers’ paid work experiences and precocious family formation behaviors, and findings have been mixed in the few studies that have examined these relationships. Bozick (2006) found that adolescents who worked intensively experienced their first sexual intercourse earlier than their peers. Likewise, Rich and Kim (2002) found that current employment status and cumulative number of months employed increased the odds of sex. Rich and Kim also found that intensive work increased the likelihood of first pregnancy by age 20, though the effect of work varied by race. Other research has reported null findings regarding the relationship between patterns of work intensity and duration during adolescence and the timing of childbearing and first marriage in young adulthood (Mortimer, 2003; Mortimer & Johnson, 1998).

Although little research has targeted this question, there are several reasons why paid work in adolescence may affect early family formation behavior, especially among teenagers who are spending long hours on the job. First, teenage workers may be more likely to engage in family formation behaviors because they come into contact with older employees, for whom such behaviors may be normative. Adolescents who are well-integrated into employment settings through intensive work may develop peer relationships with older coworkers, obscuring age differences, facilitating attitudes and opportunities favorable to family formation behaviors, and providing opportunities to act in accordance with these revised attitudes. More directly, if employment leads to an older pool of potential relationship partners, older partners may initiate teenage workers into earlier adult-like sexual behavior (Bauermeister, Zimmerman, Xue, Gee, & Caldwell, 2009).

Second, employed teenagers may be more likely to engage in family formation behaviors if working compromises their school success or long-term ambitions. Research shows that female fertility is inversely related to education (Mason, 2001), and youths who work intensively tend to have worse educational outcomes than their counterparts who work moderately or not at all. For instance, although some youth employment experiences are valuable for both education and later adult employment (Leventhal, Graber, & Brooks-Gunn, 2001; Mortimer, 2003), heavy investment in work while still in school is associated with reductions in school effort, engagement, attendance, and completed homework assignments (Monahan et al., 2011; Staff, Schulenberg, & Bachman, 2010), as well as lower grades (Marsh & Kleitman, 2005) and diminished longer-term educational attainment (Ahituv & Tienda, 2004; Bachman et al., 2011; Lee and Staff, 2007; Staff & Mortimer, 2007; Warren & Lee, 2003). Thus, poor school performance and academic disengagement may help to explain a positive association between precocious work and family roles in adolescence.

Third, teenagers may be more likely to engage in family formation behaviors if their paid work facilitates unsupervised socializing with peers, or if working leads to greater autonomy from parents. Employed youth who work long hours spend more time in unsupervised and often unstructured social activities away from the parental home, such as attending parties, going on dates, and spending nights out for fun and recreation (Osgood, 1999; Safron et al., 2001). According to routine activities theory (Osgood, Wilson, O'Malley, Bachman, & Johnston, 1996), unsupervised peer socializing increases the risk of substance use and delinquency, and it may also increase the likelihood of precocious family formation behaviors. In addition, beyond the accumulation of the necessary financial resources needed for residential independence, the experience of working may foster a sense of adult independence and a perception that they are no longer “children” in the parental home (Goldscheider & DaVanzo, 1989). Residential independence, cohabitation, and marriage can also serve as markers of such adult status. Moreover, involvement in the work force can lead to greater freedom from parental control and weaker ties to parents (Greenberger & Steinberg, 1986; Longest & Shanahan, 2007), which is associated with an increased likelihood of family formation behaviors (Longmore, Manning, & Giordano, 2001).

Finally, the effect of paid work on precocious family formation behaviors may be a spurious reflection of prior behaviors, orientations, and sociodemographic factors. Although the vast majority of high school students hold a paid job at some time during adolescence, there is a great deal of variation in the duration and intensity of the work experience (Mortimer, 2003). It could be that similarly situated teenagers choose both intensive work and early adult-like behaviors and roles. For instance, according to precocious development theory (Newcomb & Bentler, 1988), drug use and other problem behaviors may increase the risk of both precocious work and family roles. In addition, youth from disadvantaged backgrounds, for example, are both more likely to work long hours during the school year (Mortimer, 2003) and engage in family formation behavior at an earlier age than more advantaged peers (Meier & Allen, 2008; Schoen, Landale, Daniels, & Cheng, 2009). To help eliminate such potentially spurious findings, it is important to control for a variety of background factors: gender, age and physical maturity, race and ethnicity, family structure, and socioeconomic background (Landale, Schoen, & Daniels, 2010; Manning, Longmore, & Giordano, 2005). Furthermore, it could be that intensive workers are simply more social with the opposite sex; if so, an apparent association with first sex or early union formation could merely be a result of greater opportunity for such behaviors. For this reason, it is also important to control for dating history (Meier, 2003). Moreover, an observed positive relationship between intensive work and early family formation behaviors may be spurious if both are an outgrowth of an adolescent’s plan or expectation for marriage during early adulthood. Thus, we also control for the respondent’s expectation that she or he will be married by age 25.

In summary, our study contributes to the small but growing literature on adolescent employment and precocious family formation behaviors in at least two important ways: First, we use nationally representative data to examine a range of early family formation behaviors, such as first sex, pregnancy, residential independence, and union formation. By taking a multiple-outcome approach, we increase the robustness of our findings and help to clarify the scope of the association between youth employment and early family formation behaviors. Furthermore, our large sample size allows us to estimate work effects on relatively rare adolescent transitions to residential independence and union formation. Second, we control for a number of known correlates of both early work and family formation behaviors, and attempt to explain precocious work-family associations in adolescence by including measures of academic engagement, school dropout, parental monitoring, unstructured socializing, marital expectations, and problem behaviors.

Method

Participants

We use data from the first two waves of the Add Health project, a large and nationally representative study of adolescents. Add Health was created with a two-stage stratified design at Wave I, using a total of 132 core schools at the first stage. At the second stage, all students at these schools in seventh through twelfth grades completed an in-school questionnaire. Some 20,000 students, a subset of the full sample excluding twelfth graders, were selected to receive a lengthier questionnaire in their homes. These initial in-home surveys were conducted in 1994 and 1995. Follow-up in-home questionnaires constituting Wave II were administered to over 14,700 respondents in 1996, on average about 11 months after each respondent’s first survey (for greater detail on the Add Health study design, see Harris, 2005).

Our data come from the 14,738 respondents who were administered both Wave I and Wave II in-home surveys. Drawing from Wave I demographic information, half of the sample is male, and the average age at Wave I was 16.2 years. The sample is diverse by race and ethnicity, with 49% identifying as non-Hispanic white, 21% as non-Hispanic Black, 19% as Hispanic, 8% Asian, and 3% reporting some other race or ethnicity.

Research Design

Our study estimates the relationships between adolescent employment and transitions to first sex, first pregnancy, first union formation, and first residential independence. To ensure that our study focuses on early transitions to family formation behavior, we restricted the samples used in our analyses in two ways. First, because our independent variable of interest is intensive work hours, we limit our analyses to adolescents who were age 15 or older at Wave I. Prior to age 15, few participants have either worked more than 20 hours per week during the school year or experienced transitions to family formation behavior (excluding sexual intercourse). Thus, although restricting the sample to age 15 or older reduces the total sample size by 32%, younger participants do not add useful variation so this choice should have little effect on our results. Nevertheless, to test for the sensitivity of this exclusion, one of the alternative specifications of our regression models is estimated without removing these participants from the sample (see details in the Results section).

Second, we must restrict the sample to analyze transitions into family formation behaviors. We exclude from each of our analyses respondents who have already experienced the outcome variable prior to Wave I. Without this restriction, we would conflate variation in the transition to early family formation behaviors with other variation unrelated to new transitions. For instance, in our analyses of sexual initiation, we excluded the 45.4% of all cases who reported experiencing sexual intercourse by Wave I. The 8.8% of women who had been pregnant prior to Wave I were excluded from the models predicting pregnancy at Wave II, and likewise for the 1.5% and 1.6% who had been married or cohabitating or residentially independent at Wave I. An alternative specification of our models instead includes all respondents and controls for whether or not the respondent reported experiencing the transition prior to Wave I (see details in the Results section).

Measures

Binary dependent variables, family formation behaviors, are measured at Wave II. All measures of independent variables, except where otherwise noted, are derived from self-reports of the participants at Wave I.

Family Formation Behaviors

Sexual intercourse is coded 1 if the respondent answered yes to the question: “Have you ever had sexual intercourse? When we say sexual intercourse, we mean when a male inserts his penis into a female’s vagina.” Pregnancy is coded 1 for yes in response to the item “Have you ever been pregnant?” No direct questions to male respondents regarding pregnancies are available in Wave II of Add Health, and we therefore restricted all analyses of pregnancy to a female sample.

Union formation, including marriage or cohabitation, is coded 1 if the respondent is married or residing with a romantic partner. Marriage is a self-reported item, and cohabitation is determined from household relationship information where respondents reported residing with a romantic partner. Residential independence is coded 0 for those respondents living with a mother, a father, any other relative from an older generation, or, someone acting “in the place of a mother [or father] to you” at the time of the Wave II interview. Respondents who did not meet any of these criteria are coded 1, indicating residential independence.

Employment

At Wave I students were asked whether they were employed, and if so, they reported the number of hours they worked on average during the school year. Consistent with prior research showing non-linear effects of paid work hours on achievement and problem behaviors (Staff et al., 2009), we categorize the work variable into three ranges: intensive hours, 21 or more hours of work; moderate hours, 1 to 20 hours of work; and none, no work.

Sociodemographic Background, Parent Relations, and Dating

We include multiple measures of sociodemographic background, parental involvement, and relationship history and outlook at Wave I that may affect both paid work and early family formation behaviors. Gender is coded as 1 = male, 0 = female. Race and ethnicity are coded as a set of five mutually exclusive categories (coded Hispanic, Black, Asian, non-Hispanic white, and other race or ethnicity). The respondent’s age in years is coded as a set of dummy variables ranging from 15 to 19 or older to assess potential non-linear effects. Family structure is assessed with four dummy variables indicating residence with: (1) both biological parents; (2) two parents at least one of whom was a step-parent; (3) one parent, whether a biological, adoptive, or step-parent; or (d) adoptive parent(s) or non-parent relative(s). Parent(s)’ highest education is coded from 1 (never attended school) to 9 (post-graduate education), obtained from the parental interview at Wave I (if available) or from respondent self-report. The natural logarithm of household income (in thousands of dollars) is also obtained from the parental interview. Finally, physical development is measured both by interviewer rating and by respondent self-report. Interviewers assessed how physically mature the respondent was compared to other adolescents of his or her age (ranging from 1 = very immature to 5 = very mature), and respondents were also asked to compare their physical development to others their age and gender (males were asked about underarm hair, facial hair, and voice pitch; females were asked about breast size, body curves, and menstruation). The gender-specific measures are an average of the four items (α = .58 for boys and for girls).

In addition, we control for the respondent’s relationship with his or her parents. Parental decision-making is a sum of six dichotomous variables (α = .60) from yes/no answers by the respondent to whether their parent(s) allow them to make decisions about friendships, clothes, watching television (e.g., amount and program type), food choices, and bedtime. We reverse-coded the scales so higher scores indicate parents that do not let the respondent make such decisions. Closeness to parents (α = .71) is coded from four questions the students were asked about their resident father and resident mother. For each parent, respondents were asked “How close do you feel to [him/her]?” and “How much do you think [he/she] cares about you?” scoring each from 1 (not at all) to 5 (very much). Parental supervision is an average of responses to six questions asking how often, from 1 (never) to 5 (always), each resident parents is home when the respondent is leaving school, returning from school, and going to bed (α = .68).

Finally, respondents reported detailed information about multiple intimate relationships (romantic and non-romantic) at Wave I and Wave II. In her analysis of sexual intercourse, Meier (2003, pp. 1039–1040) controlled for categories of dating as a way to partially control for sexual opportunities. We extend Meier’s reasoning using an identical measure: more dating involvement indicates greater availability of a partner for pregnancy, marriage, and cohabitation as well as sexual intercourse. Self-reported information on dating was coded into four exclusive categories: (a) dating the same person continuously from Wave I through Wave II, (b) dating at Wave I but not dating the same person at Wave II, (c) had dated prior to Wave I, but were not in a relationship at the time of the Wave I interview, or (d) had no such relationship involvement, current or past, at Wave I. A measure of marital expectations captures the respondent’s expectations at Wave I of marriage by age 25, from 1 (almost no chance) to 5 (almost certain).

Schooling

Though all respondents attended school during Wave I, 12% were not attending school at Wave II. They were asked why, and we created four indicator variables based upon their responses (i.e., suspension, dropout or expulsion, early graduation, or some other reason). The Add Health picture vocabulary test, a modified version of the Peabody Picture Vocabulary Test (Dunn & Dunn, 1981), was administered during the in-home interview. The standardized test score is used here as a measure of academic ability. Grade point average was computed as an average of the student’s four self-reported grades in their most recent courses in English or language arts, mathematics, history or social science, and science (α = .75). A measure of educational aspirations is coded from a single item: “On a scale of 1 to 5, where 1 is low and 5 is high, how much do you want to go to college?” Trouble at school is a three-item measure (α = .68) consisting of the adolescent’s self-reports of the frequency of getting along with teachers, paying attention, and completing homework (ranging from 0 = never to 4 = every day). Finally, school attachment is a three-item measure (α = .77) indicating the extent to which the respondent feels close to people at school, happy to be at school, and part of the school. School attachment items were reverse-coded, so that 1 represents the lowest levels of attachment and 5 the highest.

Delinquency and Peers

The measure of delinquency represents the average of eight items (α = .74) indicating the frequency of drug sales, property crime, and violent crime in the past 12 months (responses ranged from 0 = never to 3 = five or more times). Alcohol use indicates the number of days the respondent drank alcohol during the past year (ranging from 1 = never to 7 = every day or almost every day). Marijuana use is coded 1 if the respondent used marijuana in the past 30 days (and 0 otherwise). Cigarette use is a dichotomous measure coded 1 (yes) from the question: “Have you ever smoked cigarettes regularly, that is, at least 1 cigarette every day for 30 days?” We also included measures of friends’ alcohol use and friends’ marijuana use (both coded as an ordinal scale from 0 to 3, corresponding to the respondent’s answers to “Of your 3 best friends, how many drink alcohol at least once a month?” and “Of your 3 best friends, how many use marijuana at least once a month?”). Finally, hanging out with friends is a single-item variable in response to the question: “During the past week, how many times did you just hang out with friends?” Answers range from 0 (not at all) to 3 (five or more times).

Statistical Analyses

We used logistic regression models to estimate the association between work intensity and each family formation behavior measure. Rather than exclude all cases with any missing information, we applied multiple imputation to handle missing data (Rubin, 1987). Using the available information for each case, we generated five imputed datasets with varying predicted values assigned to each missing cell (using the ICE multiple imputation procedure in Stata; see Royston, 2009). In order to compensate for our use of five imputed datasets, we average regression estimates and correct standard errors across the datasets (using the MIM command in Stata; see Royston, Carlin, & White, 2009). Furthermore, because Add Health data uses a complex survey design (Chantala, 2006), the standard errors of the regression estimates required further adjustment to account for clustering by school and region (using the SVY survey adjustment command in Stata). Since the probability sampling weights are functions of predictor variables included in our analyses, following Winship and Radbill (1994), we do not use sampling weights. We do, however, report weighted regression estimates as an alternative specification of these models.

Results

Descriptive Statistics

Table 1 displays the means, standard deviations, and ranges of the outcome and predictor variables used in our analyses. The left columns of Table 1 show values prior to imputation, and the right columns show the averaged results from our five imputed data sets. As the table shows, the differences between descriptive statistics before and after imputation are minimal.

Table 1.

Descriptive Statistics for Dependent and Independent Variables

| Original Data |

Imputed Data |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean | S.D. | Range | Mean | S.D. | |

| Outcomes | |||||

| First sex | 25.7% | 0–1 | 25.7% | ||

| First pregnancy (female only) | 8.7% | 0–1 | 8.7% | ||

| First union formation | 2.4% | 0–1 | 2.4% | ||

| First residential independence | 3.9% | 0–1 | 3.9% | ||

| Lagged Outcomes (Wave I) | |||||

| Sex | 45.4% | 0–1 | 45.4% | ||

| Pregnancy (female only) | 8.8% | 0–1 | 8.8% | ||

| Union formation | 1.5% | 0–1 | 1.5% | ||

| Residential independence | 1.6% | 0–1 | 1.6% | ||

| Work | |||||

| Moderate (1 to 20 hours) | 38.3% | 0–1 | 38.3% | ||

| Intensive (21 or more hours) | 13.7% | 0–1 | 13.7% | ||

| Demographics | |||||

| Male | 50.0% | 0–1 | 50.0% | ||

| Race and ethnicity | |||||

| Black | 21.4% | 0–1 | 21.4% | ||

| Hispanic | 18.8% | 0–1 | 18.8% | ||

| Asian | 7.8% | 0–1 | 7.8% | ||

| Other race/ethnicity | 2.7% | 0–1 | 2.7% | ||

| Age | 16.2 | (1.04) | 15–21 | 16.2 | (1.04) |

| Physical development | |||||

| Interviewer-rated | 3.4 | (.82) | 1–5 | 3.4 | (.82) |

| Male self-reported | 3.2 | (.75) | 1–5 | 3.2 | (.74) |

| Female self-reported | 3.9 | (.73) | 1–5 | 3.9 | (.73) |

| Family Structure | |||||

| Adoptive or stepparent | 13.0% | 0–1 | 13.0% | ||

| Single-parent | 29.6% | 0–1 | 29.6% | ||

| Other family structure | 7.0% | 0–1 | 6.9% | ||

| Parents’ education | 4.7 | (1.64) | 1–7 | 4.7 | (1.64) |

| Household income | 3.5 | (.95) | −1.0–6.9 | 3.4 | (.95) |

| Dating | |||||

| Dated prior to Wave I | 32.6% | 0–1 | 32.6% | ||

| Dating at Wave I | 16.8% | 0–1 | 16.7% | ||

| Dating through Wave II | 23.0% | 0–1 | 23.0% | ||

| Expectation of marriage | 3.2 | (1.11) | 1–5 | 3.2 | (1.11) |

| Parents | |||||

| Parental decision-making | 1.7 | (1.53) | 0–7 | 1.7 | (1.53) |

| Attachment to parents | 4.6 | (.58) | 1–5 | 4.6 | (.59) |

| Parental supervision | 3.3 | (.89) | 1–5 | 3.3 | (.89) |

| Schooling | |||||

| Post-secondary at Wave II | 3.7% | 0–1 | 3.7% | ||

| Out of school at Wave II | |||||

| Suspended | 0.2% | 0–1 | 0.2% | ||

| Dropped out or expelled | 4.7% | 0–1 | 4.7% | ||

| Graduated | 4.6% | 0–1 | 4.6% | ||

| Other reason | 2.5% | 0–1 | 2.5% | ||

| Picture vocabulary test | 99.4 | (15.08) | 13–131 | 99.4 | (15.07) |

| Estimated grade point average | 2.7 | (.77) | 1–4 | 2.7 | (.77) |

| Educational aspirations | 4.4 | (1.08) | 1–5 | 4.4 | (1.09) |

| Trouble at school | 1.1 | (.80) | 0–4 | 1.1 | (.80) |

| Attachment to school | 3.7 | (.87) | 1–5 | 3.7 | (.88) |

| Delinquency and Peers | |||||

| Delinquency | −0.3 | (.90) | −1.0–2.1 | −0.3 | (.90) |

| Alcohol use | 1.2 | (1.50) | 0–6 | 1.2 | (1.50) |

| Marijuana use | 16.8% | 0–1 | 17.2% | ||

| Cigarette use | 22.5% | 0–1 | 22.4% | ||

| Hanging out with friends | 2.0 | (1.00) | 0–3 | 2.0 | (1.00) |

| Friends’ alcohol use | 1.2 | (1.18) | 0–3 | 1.2 | (1.18) |

| Friends’ marijuana use | 0.7 | (1.04) | 0–3 | 0.7 | (1.04) |

| N | 14,738 | 73,690 (5 data sets) | |||

Regression Models

Our initial findings regarding the associations between adolescent work and precocious family formation behaviors are displayed in Table 2. The results indicate statistically significant associations between intensive work and first sex (odds ratio = 2.01), first pregnancy (odds ratio = 1.56), first residential independence (odds ratio = 1.88), and first union formation (odds ratio = 1.66), even after controlling for gender, race or ethnicity, age, physical development and maturity, family structure, parents’ education and household income, dating history and outlook, and parents’ decision-making, as well as the respondent’s attachment to and supervision by parents. We find no statistically significant differences between moderate workers and non-workers in their odds of precocious family formation behaviors. The associations between early work experience and family formation behaviors do not appear to be spurious due to preexisting differences in demographics or socioeconomic background, nor are they merely reflective of varying parental involvement or dating.

Table 2.

Logistic Regression Estimates for Associations Between Adolescent Work and Family Formation Behaviors

| Sexual Intercourse (n = 5,390) |

Pregnancy (n = 4,561) |

Union Formation (n = 9,866) |

Residential Independence (n = 9,862) |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| O.R. | t | O.R. | t | O.R. | t | O.R. | t | |

| Work Hours (vs. no Work) |

||||||||

| Moderate (1–20 hrs.) | 1.068 | 0.91 | 1.047 | 0.32 | 1.110 | 0.60 | 0.915 | −0.57 |

| Intensive (21+ hrs.) | 2.014 | 6.56*** | 1.555 | 2.52* | 1.885 | 3.09** | 1.657 | 3.60*** |

Note: Each model controls for respondent’s gender, race/ethnicity, age, physical development, family structure, parental education and income, dating experience and outlook, and parental measures (decision-making, closeness, and supervision). Analyses adjusted for complex survey design with Stata SVY command.

Significance: * p < .05;

p < .01;

p < .001.

These initial models provide a baseline from which to examine potential explanations for the observed links between precocious work and family formation behaviors. The models shown in Table 3 include all variables described above, accounting for background and demographic factors, relationship history, and parental involvement, as well as school status, test scores, GPA, educational attachment and aspirations, trouble at school, the respondent’s own delinquency and substance use, involvement in unstructured “hanging out” with peers, and friends’ substance use. We thereby control for a variety of indicators of precocious maturity. If intensive work coefficients are substantially reduced in the full models including precocious maturity, it would suggest that differences in precocious maturity account for the relationship between intensive work and early family formation behaviors.

Table 3.

Logistic Regression Estimates for Associations Between Adolescent Work and Family Formation Behaviors: Full Models Including Measures of Schooling, Peers and Delinquency

| Sexual Intercourse (n = 5,390) |

Pregnancy (n = 4,561) |

Union Formation (n = 9,866) |

Residential Independence (n = 9,862) |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| O.R. | t | O.R. | t | O.R. | t | O.R. | t | |

| Work Hours (vs. no work) | ||||||||

| Moderate (1–20 hrs.) | 1.038 | 0.49 | 1.133 | 0.81 | 1.204 | 1.03 | 0.983 | −0.10 |

| Intensive (21+ hrs.) | 1.758 | 4.74*** | 1.445 | 1.96† | 1.703 | 2.32* | 1.394 | 2.24* |

| Demographics | ||||||||

| Male (vs. Female) | 0.784 | −0.89 | 1.628 | 0.75 | 0.862 | −0.27 | ||

| Race/ethnicity (vs. White) | ||||||||

| Black | 0.999 | −0.01 | 0.717 | −1.81 | 0.929 | −0.26 | 1.083 | 0.48 |

| Hispanic | 1.693 | 5.20*** | 1.447 | 2.47* | 0.306 | −3.46*** | 1.108 | 0.56 |

| Asian | 0.731 | −2.44* | 0.858 | −0.47 | 0.772 | −0.68 | 0.853 | −0.70 |

| Other race/ethnicity | 1.160 | 0.73 | 1.654 | 1.59 | 0.923 | −0.15 | 1.383 | 0.89 |

| Age (vs. 15 years old) | ||||||||

| 16 | 1.176 | 1.89 | 1.328 | 1.95 | 1.678 | 2.00* | 2.900 | 4.76*** |

| 17 | 1.370 | 2.88** | 1.538 | 2.52* | 2.239 | 2.81** | 5.237 | 7.27*** |

| 18 | 1.310 | 1.40 | 1.716 | 2.14* | 2.748 | 3.14** | 6.165 | 6.39*** |

| 19+ | 1.389 | 1.02 | 1.776 | 1.31 | 5.372 | 4.41*** | 8.941 | 5.70*** |

| Physical development | ||||||||

| Interviewer-rated | 1.029 | 0.76 | 1.139 | 1.81 | 1.010 | 0.11 | 1.148 | 1.65 |

| Male self-reported | 1.186 | 2.54* | 0.999 | −0.01 | 1.023 | 0.23 | ||

| Female self-reported | 1.051 | 0.92 | 0.921 | −0.96 | 1.327 | 2.37* | 1.057 | 0.52 |

| Family structure (vs. intact) |

||||||||

| Adoptive or stepparent | 1.240 | 2.01* | 1.519 | 1.89 | 1.356 | 1.33 | 1.436 | 2.00* |

| Single-parent | 1.522 | 3.69*** | 1.388 | 1.74 | 1.507 | 2.06* | 1.605 | 2.75** |

| Other family structure | 1.614 | 2.24* | 1.793 | 2.03* | 3.082 | 4.77*** | 4.053 | 7.49*** |

| Parents’ education | 0.910 | −3.75*** | 0.893 | −2.36* | 0.924 | −1.62 | 0.923 | −1.77 |

| Household income | 0.965 | −0.65 | 1.013 | 0.16 | 0.864 | −1.81 | 0.856 | −1.97* |

| Parents | ||||||||

| Parental decision-making | 1.004 | 0.21 | 0.950 | −1.14 | 0.938 | −1.04 | 1.029 | 0.69 |

| Attachment to parents | 1.018 | 0.32 | 0.967 | −0.34 | 1.012 | 0.13 | 0.952 | −0.59 |

| Parental supervision | 0.988 | −0.20 | 0.825 | −2.32* | 0.930 | −0.70 | 0.741 | −3.86*** |

| Dating (vs. no current or prior dating) |

||||||||

| Dated prior to Wave I | 2.158 | 7.91*** | 1.985 | 3.80*** | 2.194 | 2.06* | 1.326 | 1.58 |

| Dating at Wave I | 3.177 | 11.88*** | 2.539 | 4.87*** | 3.305 | 3.06** | 1.630 | 2.24* |

| Dating through Wave II | 4.584 | 12.13*** | 3.461 | 7.99*** | 4.789 | 4.34*** | 1.643 | 2.75** |

| Expectation of marriage | 0.959 | −1.24 | 0.997 | −0.07 | 1.325 | 4.23*** | 1.162 | 2.87** |

| Schooling (vs. currently attending high school) |

||||||||

| Post-secondary at Wave II | 1.625 | 2.21* | 0.808 | −0.85 | 0.722 | −0.85 | 2.374 | 3.69*** |

| Out of school at Wave II | ||||||||

| Suspended | 0.671 | −0.31 | 1.326 | 0.23 | 3.867 | 1.21 | 1.381 | 0.27 |

| Dropped out/expelled | 2.520 | 4.99*** | 2.240 | 3.86*** | 3.871 | 5.10*** | 3.643 | 6.54*** |

| Graduated | 1.097 | 0.50 | 0.971 | −0.10 | 2.999 | 4.66*** | 3.738 | 7.93*** |

| Other reason | 0.910 | −0.35 | 2.251 | 2.37* | 2.830 | 2.74** | 4.499 | 4.43*** |

| Picture vocabulary test | 0.993 | −2.36* | 0.978 | −4.46*** | 0.986 | −2.83** | 0.995 | −1.14 |

| Estimated GPA | 0.883 | −2.46* | 0.834 | −1.90 | 0.990 | −0.08 | 1.108 | 1.08 |

| Educational aspirations | 0.953 | −1.17 | 0.911 | −1.65 | 0.849 | −2.68** | 0.885 | −2.73** |

| Trouble at school | 1.026 | 0.49 | 0.977 | −0.29 | 0.905 | −1.01 | 1.071 | 0.90 |

| Attachment to school | 0.907 | −2.01* | 0.986 | −0.22 | 0.866 | −1.85 | 0.819 | −3.07** |

| Delinquency and Peers | ||||||||

| Delinquency | 1.108 | 2.00* | 1.214 | 2.57* | 0.945 | −0.56 | 0.934 | −0.94 |

| Alcohol use | 1.168 | 4.31*** | 1.013 | 0.28 | 1.008 | 0.16 | 1.014 | 0.30 |

| Marijuana use | 1.532 | 3.15** | 0.949 | −0.24 | 0.776 | −1.12 | 0.657 | −2.67** |

| Cigarette use | 1.463 | 3.43*** | 1.194 | 1.20 | 1.186 | 0.81 | 1.589 | 3.28** |

| Hanging out with friends | 1.097 | 2.54* | 0.946 | −1.11 | 1.002 | 0.03 | 0.964 | −0.55 |

| Friends’ alcohol use | 1.118 | 2.73** | 1.031 | 0.45 | 0.983 | −0.20 | 1.052 | 0.90 |

| Friends’ marijuana use | 1.040 | 0.60 | 1.215 | 2.66** | 1.011 | 0.13 | 0.972 | −0.35 |

Note: Analyses adjusted for complex survey design with Stata SVY command.

Significance: † p = .052

p < .05;

p < .01;

p < .001.

As shown in the first column of Table 3, moderate workers during the school year show no statistically significant difference from non-workers in the odds of first sexual intercourse. However, the odds of students who reported working more than 20 hours per week during school at Wave I to initiate first sex by Wave II were 76% higher than the odds of non-workers. The likelihood of first sex also varies significantly by age, race or ethnicity, parent’s education, family structure, and dating history. School engagement, including higher GPA and higher school attachment, appears to have a protective effect, while almost all delinquency measures are associated with higher odds of engaging in first sex. High school dropouts are substantially more likely to have first sex compared to youth still in school. The inclusion of measures of academic disengagement, substance use, and delinquency reduces the coefficient of intensive work by 19% from Table 2 to Table 3.

Column 2 shows that, among the female subsample, the odds of first pregnancy appear to be roughly 45% higher among women who worked intensively compared to their non-working counterparts; however, this result is at borderline significance (p = .052). Similar to the model predicting first sex, Hispanic respondents and those from single parent families or with lower parental education are more likely to report first pregnancy. Moreover, dropouts are more likely to be pregnant than youth currently in school. Ongoing relationships predict pregnancy, as does delinquency and friends’ drug use. The coefficient for intensive work in the pregnancy model is reduced by 17% from Table 2 to Table 3.

Table 3 also shows the results of two binary logistic regression models predicting first union formation and residential independence for both women and men. Compared to non-work, intensive work increases the odds of first union formation by 70% and first residential independence by 40%. Compared to non-work, moderate hours of work show no significant associations with either outcome. Hispanics and respondents whose parents had low levels of education are less likely to be married or cohabiting. Respondents from non-two-parent families are more likely to become residentially independent or enter a cohabitation or marriage, as are respondents who left school for any reason. Overall, inclusion of the explanatory measures reduces the magnitude of the intensive work coefficient by 34% for the residential independence outcome and 16% for the union formation outcome; nonetheless, both coefficients remain statistically significant. These results show an overarching association between intensive work and the transition to adult-like residential and relationship responsibilities.

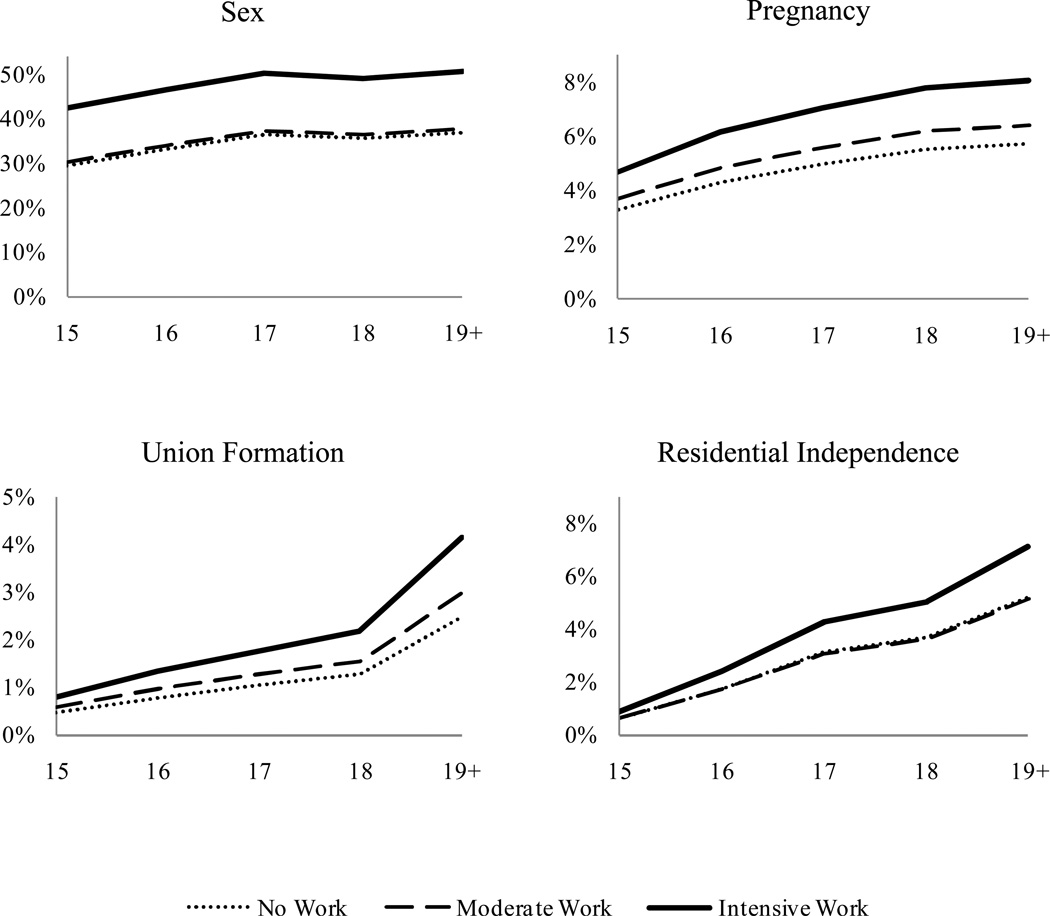

Age showed strong, non-linear effects on family formation behaviors in all the models in Table 3. To help the reader better understand these relationships, we calculated predicted probabilities for each outcome based upon age and work status (i.e., intensive, moderate, or non-worker). As shown in Figure 1, adolescents working fewer than 20 hours are estimated to be almost identical in their likelihood to experience transitions to these family formation behaviors and roles, net of controls. Those working more than 20 hours, however, are consistently predicted to be “ahead” of their ages, often by a year or more. They are more adult-like insofar as they are more likely to experience their first sex, pregnancy, marriage or cohabitation, and residential independence – behaviors and roles that become more normative in adulthood.

Figure 1.

Predicted Probability of Family Behavior Outcomes by Age and Amount of Work

Alternative Specifications of Regression Models

To assess the robustness of intensive work effects on precocious family formation behaviors, we considered several alternative specifications of the models shown in Table 3. The full results of these alternative models are not displayed, but are available by request. First, we estimated our models using the probability weights included in Add Health. The weighted results were very similar to the main results. For instance, the effect of intensive work on first sex is reduced slightly when probability weights are included in our analyses (odds ratio = 1.48), whereas the residential independence estimate increases modestly (odds ratio = 1.52). The estimated effects of intensive work on first pregnancy and union formation remain nearly identical with and without weighting.

Second, since 45.4% of respondents had already experienced sexual intercourse by Wave I (see Table 1), and were thus not included in our previous models of sexual initiation, in alternative models we included these respondents in our analyses and incorporated a lagged measure indicating previous sexual intercourse by Wave I. In this model specification, intensive workers are still more likely than non-workers to have sexual intercourse, with 52% increased odds. The inclusion of lagged measures of a previous pregnancy, union formation, and residential independence (though these outcomes had fewer Wave I reports) similarly reduce the effects of intensive work on these precocious family roles (odds of pregnancy = 1.31; odds of union formation = 1.54; odds of residential independence = 1.29).

Third, to assess whether estimates of work effects varied by gender, we estimated separate models for women and men, and then compared work effects between models with a z-test of coefficient invariance (Clogg, Petkova, & Haritow, 1995). No differences between women and men in the work estimates are statistically significant for any of the four outcomes. As a second approach to this alternative specification, we kept participants of both genders together in one model and created an interaction between work indicators (moderate and intensive) and gender indicators. Again, we observed no statistically significant difference (p < .05) by gender in the associations between work and precocious family formation behaviors.

Fourth, as some researchers have found variation in work effects by race (Rich & Kim, 2002), we also considered race and ethnicity as potential moderators. Our additional analyses included interactions of the four race or ethnicity categories with the 3 categories of paid work, but only 3 of 32 interactions were statistically significant (p < .05). Since we found no consistent pattern in the results, and a Bonferroni correction (α = .05/32 = .0016) would render them not statistically significant, we concluded that the association between work hours and precocious family formation does not appear to vary by race or ethnicity.

Fifth, we estimated models that included the third of respondents (32%) who were between the ages of 11 and 14 at Wave I. With few students working long hours or reporting family formation behaviors at such young ages, they contribute little to the intensive work coefficient estimates. It is therefore not surprising that the relationships reported in Table 3 are nearly identical to models that included respondents who are younger than age 15.

Finally, due to the importance of age as a developmental variable, we tested a number of interactions between age and work, varying our measurement approaches. Though the sample is limited to those aged 15 or older, it is certainly conceivable that the effect of working during school could vary among respondents of different ages. We tested three age-by-work interaction approaches – categorical, linear, and curvilinear – but found no indication that the observed relationship between intensive work and family formation behavior varies by age. For the categorical specification, we added four interaction variables of age by intensive work to each full model. Of these sixteen interactions across the four models, none are statistically significant. A linear specification replaced these categorical interactions with a linear measure of age and a multiplied age by intensive work interaction; none of the four interactions are significant. Finally, the curvilinear specification added squared age terms and squared age by work interaction terms. Again, the results include no significant interactions between intensive work and age. In sum, no interactions between work and age are found. To the extent that work accelerates transitions to family formation behavior, it appears to do so consistently across the mid-to-late teenage years.

Discussion

The percentage of employed teenagers in the United States has declined in recent years (Johnston, Bachman, & O’Malley, 2010, p. 25), but most youth still work at some point during adolescence (Staff et al., 2009). Though scholars continue to show both benefits and harms of teenage work experiences on academic achievement, problem behaviors, and social development (Apel et al., 2007; Bachman et al., 2011; Marsh & Kleitman, 2005; Staff & Mortimer, 2007; Monahan et al., 2011), little research has considered whether early work experiences influence precocious family formation behaviors. In this study, we used nationally representative data to examine paid work effects on first sex as well as pregnancy, residential independence, and union formation. To increase the robustness of our findings, we used a multiple-outcome approach and controlled for a number of known correlates of precocious work and family formation behaviors. We also included numerous measures in the school, family, and peer domains to help assess whether working teenagers engage in precocious family formation behaviors because work is compromising school and long-term ambitions, increasing autonomy from parents, or facilitating unstructured and unsupervised socializing with peers.

Our study shows a consistent pattern of paid work effects across a broad range of precocious family roles and behaviors, including sexual debut, pregnancy, the transition to residential independence, and the steps toward an adolescent’s own family via union formation (e.g., marriage and cohabitation). Even after imposing stringent controls for factors that have been shown to affect early family formation behaviors, such as parental closeness, supervision, and decision making, socioeconomic background, family structure, and relationship history and outlook (Longmore et al., 2001; Manning et al., 2005; Meier, 2003; Meier & Allen, 2008; Schoen et al., 2009), we found that youth who worked intensively during the school year were more likely to begin engaging in family formation behavior than youth who worked fewer hours or not at all. Importantly, moderate hours of paid work had little or no effect on adolescent family formation behaviors.

The positive relationship between teenage work hours and precocious family formation behaviors is consistent with research showing that youth who spend long hours on the job are more likely to engage in behaviors that are normative for adults but deviant for adolescents, such as smoking cigarettes and drinking alcohol (Bachman et al., 2011; Longest & Shanahan, 2007; McMorris and Uggen, 2001; Monahan et al., 2011). Compared to non- or moderately working teenagers, research also shows that those youth who work intensively perform worse in school, are less engaged in school, spend less time in extracurricular and other activities organized for adolescents, and are less likely to complete high school, matriculate to college, or graduate with a four-year degree (Bachman et al., 2011; Staff & Mortimer, 2007; Mortimer, 2003). Taken as a whole, the early adoption of family formation behaviors should be considered as additional risk factors associated with intensive work hours during adolescence (Bachman & Schulenberg, 1993; Jessor & Jessor, 1977; Newcomb & Bentler, 1988).

We considered a number of plausible reasons for these precocious work-family associations in adolescence, but found only weak support that school disengagement and failure, increased autonomy from parents, problem behaviors, and unsupervised socializing explained why intensive workers were more likely to engage in family formation behaviors than other youth. We found that between 16% and 34% of the differences between intensive workers and non-workers, net of the initial controls, were accounted for by these explanatory variables. Intensive workers were more likely to experience first sex, pregnancy, residential independence, and union formation earlier than their moderately and non-working counterparts, even after accounting for the behaviors and orientations that might explain these relationships.

Although we include a set of stringent controls, it is difficult to know whether the associations between paid work and family formation behaviors we find in this study are indeed causal. Precocious development theory, in particular, posits that these precocious work-family relationships results from prior orientations and behaviors (Newcomb & Bentler, 1988). For example, for youth who have a strong desire to spend long hours on the job, the orientation to work, rather than their work investments per se, may predict both work and family roles (Staff et al., 2010). Similarly, the precocious work-family relationships may reflect a strong desire for adult-like independence (Bachman & Schulenberg, 1993). Orientations toward future family roles might also predict both work investments and family formation behaviors (Manning, Longmore, & Giordano, 2007), an issue partly addressed through our inclusion of a control for the respondent’s marital expectations at Wave I. Nonetheless, teenage employment could both reflect and encourage self-perceptions of maturity, leading to adult-like transitions. Direct measures of pre-existing attitudes or maturity were, unfortunately, not available in our data. We were therefore unable to isolate the direct effect of work net of prior orientations toward family roles and an overall strive for adult independence.

An additional limitation of the present study is that we did not include childbearing as an outcome. The primary reason for this is that only a short time elapsed between the Wave I and Wave II surveys, between 8 and 13 months for most respondents. Of the few adolescents in the sample who became parents by Wave II, some of them would have already been pregnant at Wave I, making it difficult to establish temporal ordering, since they would have been pregnant prior to making decisions about how much to work at Wave I. Our analysis of Wave II pregnancy therefore provides a better estimate of the association between work and fertility behaviors than Wave II childbearing. Though the teenage birthrate in the United States is historically low (Hamilton, Martin, & Ventura, 2010), future research should examine the relationship between intensive work hours and teenage childbearing.

Future research should also examine whether the effect of adolescent paid work on family formation behaviors depends on the quality of the job. For example, minimum wage service jobs may not provide enough support to allow youth to establish residential independence from their parents. Higher-wage jobs may also allow some teenage workers to invest more of their income in relationships with peers and romantic partners. As noted earlier, teenagers who work with older coworkers may be more likely to engage in precocious family formation behaviors. On the other hand, young workers in high-quality jobs may delay family formation so as not to jeopardize their career development. Though Add Health does not contain detailed information on the type, age-structure, or quality of work, these work conditions might help to explain the statistically significant associations we show in this study, and are worthwhile avenues for future research.

In sum, our study provides evidence that youth involvement in paid work is associated with early family formation behaviors that are pivotal in determining the life course trajectories of youth as they transition to adulthood. While we cannot be certain of the causal centrality of paid work in the family formation processes examined here, our results clearly support the view that youth involved in intensive work are “at risk” for engaging in behaviors that may lead to early—or, some might say, premature—family formation. Youth entering the paid labor force, therefore, may gain from the additional attention of parents, school personnel, and perhaps employers. It is in the interest of these adults, and the students themselves, that adolescent work experiences contribute to long-term well-being rather than lead to involvement in behaviors that jeopardize the quality of their later adult lives.

Acknowledgements

This research uses data from Add Health, a program project designed by J. Richard Udry, Peter S. Bearman, and Kathleen Mullan Harris, and funded by a grant P01-HD31921 from the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development, with cooperative funding from 17 other agencies. Special acknowledgment is due Ronald R. Rindfuss and Barbara Entwisle for assistance in the original design. Persons interested in obtaining data files from Add Health should contact Add Health, Carolina Population Center, 123 W. Franklin Street, Chapel Hill, NC 27516-2524 (addhealth@unc.edu). No direct support was received from grant P01-HD31921 for this analysis. Jeremy Staff is grateful for support from a Mentored Research Scientist Development Award in Population Research from the National Institute of Child Health and Human Development (HD054467).

Footnotes

A previous version of this paper was presented at the 2010 Meeting of the Population Association of America.

Contributor Information

Jeremy Staff, Email: jus25@psu.edu, Department of Sociology, Pennsylvania State University, 211 Oswald Tower, University Park, PA 16802-6207.

Matthew VanEseltine, Department of Sociology, Bowling Green State University, Bowling Green, OH 43403.

April Woolnough, Department of Sociology, Pennsylvania State University, 211 Oswald Tower, University Park, PA 16802-6207.

Eric Silver, Department of Sociology, Pennsylvania State University, 211 Oswald Tower, University Park, PA 16802-6207.

Lori Burrington, Department of Sociology, Pennsylvania State University, 211 Oswald Tower, University Park, PA 16802-6207.

References

- Ahituv A, Tienda M. Employment, motherhood, and school continuation decisions of youth White, Black, and Hispanic women. Journal of Labor Economics. 2004;22:115–158. [Google Scholar]

- Apel R, Bushway S, Brame R, Haviland AM, Nagin DS, Paternoster R. Unpacking the relationship between adolescent employment and antisocial behavior: A matched samples comparison. Criminology. 2007;45:67–97. [Google Scholar]

- Bachman JG, Schulenberg J. How part-time work intensity relates to drug use, problem behavior, time use, and satisfaction among high school seniors: Are these consequences or merely correlates? Developmental Psychology. 1993;29:220–235. [Google Scholar]

- Bachman JG, Staff J, O’Malley P, Schulenberg JE, Freedman-Doan P. Student work intensity: New evidence on links to educational attainment and problem behaviors. Developmental Psychology. 2011;47:344–363. doi: 10.1037/a0021027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bauermeister JA, Zimmerman M, Xue Y, Gee GC, Caldwell CH. Working, sex partner age differences, and sexual behavior among African American youth. Archives of Sexual Behavior. 2009;38:802–813. doi: 10.1007/s10508-008-9376-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bozick R. Precocious behaviors in early adolescence: Employment and the transition to first sexual intercourse. The Journal of Early Adolescence. 2006;26:60–86. [Google Scholar]

- Chantala K. Guidelines for analyzing Add Health data. Carolina Population Center, University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill; 2006. Retrieved September 16, 2009, from http://www.cpc.unc.edu/projects/addhealth/data/using/guides. [Google Scholar]

- Clogg CC, Petkova E, Haritou A. Statistical methods for comparing regression coefficients between models. American Journal of Sociology. 1995;100:1261–1293. [Google Scholar]

- Coleman J, Bremner R, Clark B, Davis J, Eichorn D, Griliches Z, et al. Youth: Transition to adulthood. Chicago: University of Chicago Press; 1974. [Google Scholar]

- Dunn LM, Dunn LM. Peabody Picture Vocabulary Test—Revised. Circle Pines, MN: American Guidance Service; 1981. [Google Scholar]

- Goldscheider FK, DaVanzo J. Pathways to independent living in early adulthood: Marriage, semiautonomy, and premarital residential independence. Demography. 1989;26:597–614. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Greenberger E, Steinberg L. When teenagers work: The psychological and social costs of adolescent employment. New York: Basic Books; 1986. [Google Scholar]

- Hamilton BE, Martin JA, Ventura SJ. Births: Preliminary data for 2008. National Vital Statistics Reports. 2010;58:1–16. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harris KM. Design features of Add Health. Carolina Population Center, University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Jessor R, Jessor S. Problem behavior and psychosocial development: A longitudinal study of youth. New York: Academic Press; 1977. [Google Scholar]

- Johnston LD, Bachman JG, O’Malley PM. Monitoring the Future: Questionnaire responses from the nation's high school seniors, 2009. Ann Arbor, MI: Institute for Social Research; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Landale NS, Schoen R, Daniels K. Early family formation among White, Black, and Mexican American women. Journal of Family Issues. 2010;31:445–474. doi: 10.1177/0192513X09342847. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee JC, Staff J. When work matters: The varying impact of adolescent work intensity on high school drop-out. Sociology of Education. 2007;80:158–178. [Google Scholar]

- Leventhal T, Graber JA, Brooks-Gunn J. Adolescent transitions to young adulthood: Antecedents, correlates, and consequences of adolescent employment. Journal of Research on Adolescence. 2001;11:297–323. [Google Scholar]

- Longest KC, Shanahan MJ. Adolescent work intensity and substance use: The mediational and moderational roles of parenting. Journal of Marriage and the Family. 2007;69:703–720. [Google Scholar]

- Longmore MA, Manning WD, Giordano PC. Preadolescent parenting strategies and teens’ dating and sexual initiation: A longitudinal analysis. Journal of Marriage and Family. 2001;63:322–333. [Google Scholar]

- Manning WD, Longmore MA, Giordano PC. The changing institution of marriage: Adolescents’ expectations to cohabit and marry. Journal of Marriage and Family. 2007;69:559–575. [Google Scholar]

- Manning WD, Longmore MA, Giordano PC. Adolescents’ involvement in non-romantic sexual activity. Social Science Research. 2005;34:384–407. [Google Scholar]

- Marsh HW, Kleitman S. Consequences of employment during high school: Character building, subversion of academic goals, or a threshold? American Educational Research Journal. 2005;42:331–369. [Google Scholar]

- Mason KO. Gender and family systems in the fertility transition. Population and Development Review. 2001;27:160–176. [Google Scholar]

- McMorris BJ, Uggen C. Alcohol and employment in the transition to adulthood. Journal of Health and Social Behavior. 2000;41:276–294. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meier A, Allen G. Intimate relationship development during the transition to adulthood: Differences by social class. New Directions for Child and Adolescent Development. 2008;119:25–40. doi: 10.1002/cd.207. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meier A. Adolescents’ transition to first intercourse, religiosity and attitudes about sex. Social Forces. 2003;81:1031–1052. [Google Scholar]

- Monahan KC, Lee JM, Steinberg L. Revisiting the impact of part-time work on adolescent adjustment: Distinguishing between selection and socialization using propensity score matching. Child Development. 2011;82:96–112. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.2010.01543.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mortimer J. Working and growing up in America. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Mortimer JT, Johnson M. New perspectives on adolescent work and the transition to adulthood. In: Jessor R, editor. New perspectives on adolescent risk behavior. New York: Cambridge University Press; 1998. pp. 425–496. [Google Scholar]

- Mortimer JT, Pimentel EE, Ryu S, Nash K, Lee C. Part-time work and occupational value formation in adolescence. Social Forces. 1996;74:1405–1418. [Google Scholar]

- Mortimer JT, Shanahan MJ. Adolescent work experience and family relationships. Work and Occupations. 1994;21:369–384. [Google Scholar]

- National Research Council. Protecting youth at work: Health, safety, and development of working children and adolescents in the United States. Washington, DC: National Academy Press; 1998. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Newcomb MD, Bentler PM. Consequences of adolescent drug use: Impact on the lives of young adults. Newbury Park, CA: Sage; 1988. [Google Scholar]

- Osgood DW. Having the time of their lives: All work and no play? In: Booth A, Crouter AC, Shanahan MJ, editors. Transitions to adulthood in a changing economy: No work, no family, no future? Westport, CT: Praeger; 1999. pp. 176–186. [Google Scholar]

- Osgood DW, Wilson JK, O’Malley PM, Bachman JG, Johnston LD. Routine activities and individual deviant behavior. American Sociological Review. 1996;61:635–655. [Google Scholar]

- Rich LM, Kim S. Employment and the sexual and reproductive behavior of female adolescents. Perspectives on Sexual and Reproductive Health. 2002;34:127–134. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Royston P. Multiple imputation of missing values: Further update of ICE, with an emphasis on categorical variables.". Stata Journal. 2009;9:466–477. [Google Scholar]

- Royston P, Carlin JB, White IR. Multiple imputation of missing values: New features for MIM.". Stata Journal. 2009;9:252–264. [Google Scholar]

- Rubin DB. Multiple imputation for nonresponse in surveys. New York: Wiley; 1987. [Google Scholar]

- Ruhm C. Is high school employment consumption or investment? Journal of Labor Economics. 1997;15:735–776. [Google Scholar]

- Safron DJ, Schulenberg JE, Bachman JG. Part-time work and hurried adolescence: The links among work intensity, social activities, health behaviors, and substance use. Journal of Health and Social Behavior. 2001;42:425–449. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schoen R, Landale NS, Daniels K, Cheng YA. Social background differences in early family behavior. Journal of Marriage and Family. 2009;71:384–395. [Google Scholar]

- Staff J, Messersmith EE, Schulenberg JE. Adolescents and the world of work. In: Lerner R, Steinberg’s L, editors. Handbook of Adolescent Psychology. 3rd ed. New York: John Wiley and Sons; 2009. pp. 270–313. [Google Scholar]

- Staff J, Mortimer JT. Educational and work strategies from adolescence to early adulthood: Consequences for educational attainment. Social Forces. 2007;85:1169–1194. doi: 10.1353/sof.2007.0057. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Staff J, Osgood DW, Schulenberg JE, Bachman JG, Messersmith EE. Explaining the relationship between employment and juvenile delinquency. Criminology. 2010;48:1101–1131. doi: 10.1111/j.1745-9125.2010.00213.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Staff J, Schulenberg JE, Bachman JG. Adolescent work intensity, school performance, and academic engagement. Sociology of Education. 2010;83:183–200. doi: 10.1177/0038040710374585. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Staff J, Uggen C. The fruits of good work: Early work experiences and adolescent deviance. Journal of Research in Crime and Delinquency. 2003;40:263–290. [Google Scholar]

- Warren JR, Lee JC. The impact of adolescent employment on high school dropout: Differences by individual and labor-market characteristics. Social Science Research. 2003;32:98–128. [Google Scholar]

- Winship C, Radbill L. Sampling weights and regression analysis. Sociological Methods & Research. 1994;23:230–257. [Google Scholar]

- Wright JP, Cullen FT. Employment, peers, and life-course transitions. Justice Quarterly. 2004;21:183–205. [Google Scholar]