Abstract

Despite the importance of learning and circadian rhythms to feeding, there has been relatively little effort to integrate these separate lines of research. In this review, we focus on how light and food entrainable oscillators contribute to the anticipation of food. In particular, we examine the evidence for temporal conditioning of food entrainable oscillators throughout the body. The evidence suggests a shift away from previous notions of a single locus or neural network of food entrainable oscillators to a distributed system involving dynamic feedback among cells of the body and brain. Several recent advances, including documentation of peroxiredoxin metabolic circadian oscillation and anticipatory behavior in the absence of a central nervous system, support the possibility of conditioned signals from the periphery in determining anticipatory behavior. Individuals learn to detect changes in internal and external signals that occur as a consequence of the brain and body preparing for an impending meal. Cues temporally near and far from actual energy content can then be used to optimize responses to temporally predictable and unpredictable cues in the environment.

Keywords: Food entrainable oscillator, food anticipatory activity, learning, circadian, metabolism

1.Introduction

The temporal dynamics of foraging, eating, digestion, and metabolism are central to the understanding of energetics. Their study has been approached via research on feeding behavior and metabolism, learning, and circadian timing, although there has been relatively little integration of these areas of interest. In the context of each field, this is understandable. These disciplines have distinct historical roots, different compelling questions, and each is intuitively salient and interesting in its own right. Another reason for the lack of intersection is discrepancy between units of analysis. At the behavioral level, feeding and learning studies focus on the meal, the regulation of meal size, and motivation to obtain a meal. Work on feeding behavior itself is concerned with delineating the cues that signal meal location and time and their relative salience. Studies of the circadian timing system are focused on understanding recurrent physiology and behavior and use eating behavior or the anticipation of eating as a window into oscillator mechanisms. If, however, one considers the body as a dynamically changing system, where change in one aspect produces change in another, the interaction between feeding, circadian oscillators, and learning become significant. In that integrative spirit, we focus on findings in the literature on circadian timing that indicate new mechanisms of interaction with feeding, conditioning, and learning and memory.

The discovery of new mechanisms is always the impetus for a paradigm shift in basic research. In the realm of the circadian timing system, several identifiable shifts have emerged following a rapid series of key discoveries. These enabled exploration of the mechanisms associated with temporal organization in the performance of bodily functions. Specifically, converging studies performed in many laboratories indicated that a master circadian clock was localized to, the suprachiasmatic nucleus (SCN) of the hypothalamus [1], the genes and proteins that constitute a core cell-based circadian clock were delineated [2], and circadian oscillators were shown to occur throughout the body, rather than being restricted to the SCN master clock [3]. This led to the detection of oscillators in peripheral organs and tissues that are entrained by food-derived cues [4, 5], and highlighted a balance among multiple synchronizing signals in the environment. The discovery of peripheral oscillators also led to the identification of large cohorts of tissue-specific genes whose transcription varies with circadian time. Most recently, it has been discovered that the oscillatory mechanisms underlying circadian rhythms do not require transcriptional mechanisms. This finding is important in the present context because for many years, the great majority of studies of circadian rhythms have been focused on mechanisms associated with cell autonomous circadian oscillation based on cyclical gene and protein expression requiring transcription and translation. This was true even though several important circadian phenomena seemed inexplicable by such mechanisms [6, 7]. It is now clear, however, that there exist biochemical pathways, evolutionarily ancient and perhaps highly conserved across taxa, that can drive circadian rhythms in the absence of transcription [8-10]. As a consequence of these discoveries we are now able to explore how these different circadian clocks are linked and the key role played by feeding-associated signals and learning.

The goal of the present paper is to describe areas of overlapping interest in three domains: circadian timing systems, feeding behavior, and leaning and motivation. Our perspective is stimulated by evidence that salient cues associated with each of these systems influence circadian oscillators located throughout the body, and that these oscillators, in turn, send signals back to the brain. We do not attempt a thorough literature review, but instead point to review papers and use specific case studies as exemplars of the main points raised.

1.1. Food entrained oscillators (FEOs) and light entrained oscillators (LEOs) in historical perspective

Within the circadian timing system it is well established that in rodents, a discrete population of about 20,000 neuronal oscillators in the SCN is the locus of a master circadian clock. This clock functions to regulate the phase and period of numerous physiological and behavioral responses, and enables entrainment to daily light-dark (LD) cycles (reviewed in [11]). The evidence for a key role of the SCN derives from years of convergent studies demonstrating that SCN ablation abolishes rhythmicity in most behavioral and physiological measures, that rhythmicity within the SCN is sustained in vitro, and that transplantation of the SCN from one animal to another produces the donor period in the recipient (reviewed in [1]; Figure 1). Given this solid evidence for a master clock in the brain, it was surprising to find, in the 1970‘s, that circadian oscillation in food anticipatory behavior (FAA) survives ablation of the SCN [12]. This result led to the possibility, and even the hope that there might be a second nucleus containing a discrete population of oscillators, located within the brain but outside of the SCN, that functioned to sustain circadian rhythms following regularly recurring daily feeding schedules. These putative food entrainable oscillators (FEOs) were thought to be circadian pacemakers independent of light entrainable oscillators (LEOs) of the SCN. Several aspects of food anticipation suggested control by a circadian mechanism.

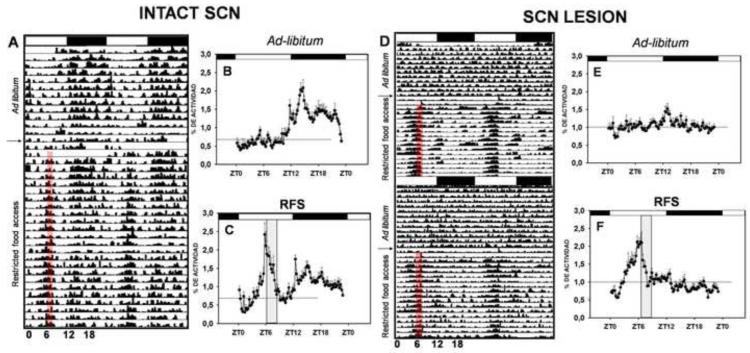

Figure 1.

Comparison of general activity of intact (A,B,C) and SCN-lesioned rats under ad lib (B, E) and food restricted (C, F) conditions. General activity of representative animals are shown in the actograms. Mean activity profiles in ad libitum feeding and during 3 weeks food restriction are displayed. Note that FAA is maintained following ablation of the SCN. Reprinted from Neuroscience, 165, Angeles-Castellanos et al., pp.1115-26, 2011, with permission from Elsevier.

1.2 FAA - the phenomenon that stimulated the search for FEOs

The weight of evidence supports the view that the body uses an endogenous circadian timing system under the control of food-entrainable oscillators to predict the availability of food. These FEOs activate food-seeking behaviors and facilitate the synthesis and secretion of hormones necessary for digestion before mealtime. In the typical experimental paradigm, food is made available for a few hours daily, sufficient to ensure that the animals have no reduction in total caloric intake or body weight (reviewed in [13, 14]). The increased activity seen in anticipation of a meal serves as a convenient measure of anticipatory behavior and generally supports a role for circadian timing mechanisms. When animals are entrained to a light:dark cycle and restricted to a single meal at a fixed time each day they exhibit increased locomotor activity beginning 1–3 h prior to mealtime. This behavior is established in about a week following repeated exposure to the regularly scheduled restricted feeding times. Importantly, the timed, daily expression of FAA continues even when meals are omitted for several days, indicating a memory for the time of day. Several aspects of the response suggest that it involves a circadian but non-SCN based oscillatory mechanism (reviewed in [14]). First, when SCN-lesioned rats are shifted from a food restriction schedule to total food deprivation, the expression of FAA continues for several days and free-runs with a circadian period. Second, FAA rhythms are most readily observed in feeding schedules with periodicity in the circadian range, indicating limits of entrainment [15].

Such evidence, among other suggestive studies, led to extensive searches for an FEO outside the SCN with the hope of finding a nucleus entrained by food that was parallel to the light entrained SCN. Note that despite limits of entrainment for a single food presentation, rats with SCN lesions can anticipate 2 meals per day [16, 17]. This raises the question of the nature of the FEO. It is not clear yet whether multiple bouts per day arise from a single complex FEO or from multiple parallel circuits or systems, each of which contributes to the timing of a single FAA peak. Answering this question would be an important step towards discovering central and peripheral substrates of FEOs.

As was done prior to the discovery of the hypothalamic clock in the SCN almost 50 years ago[18], virtually each part of the brain has been lesioned in the mostly unsuccessful search for a discretely located food entrainable clock (reviewed in [19]). The search was re-invigorated with the development of molecular tools for studying cell-based oscillation in the brain and periphery [5, 20, 21]. This work led to the puzzling finding that such a clock could not be located definitively in either the central nervous system or in peripheral sites [22]. The debate was inflamed in recent years by disagreements on the interpretation of evidence for the presence or absence of FAA and rhythmic clock gene expression following lesions and subsequent rescue of gene expression in various brain regions and in various clock mutant animals [23].

While a necessary brain site for FEOs is debatable, a long history of studies has produced firm evidence that feeding cues can alter the rhythms of neuronal activity and clock-gene expression [24-26] . These data indicate that the FEO timing system may engage a distributed circuit rather than a discrete localized site in the brain [27]. In parallel, there is clear evidence of food entrained circadian oscillation in peripheral organs [28, 29]. There is also a suggestion that the FEO shares features with a methamphetamine sensitive circadian oscillator that similarly persists after SCN lesions [30, 31] with the further suggestion that such oscillators may not require canonical clock genes [32].

1.3. Characteristics of FAA

Several aspects of anticipatory responses clearly show that there is more to the underlying mechanisms than FEOs in one neural locus or in a distributed circuit. First, FAA involves learning and memory. It takes about a week to establish FAA indicating that it is a conditioned response. Once established, this learned response is remembered even after a period of ad libitum feeding. Second, we challenge the notion that because FAA involves learning and memory, it must take place in the brain and propose that anticipatory responses can occur in the absence of a brain, and is evidenced in peripheral organs. Third, studies of FAA often restrict access to food to short meal durations of 2-4 hours. We can reasonably conclude that in these conditions the animals are food deprived, with the consequence that hunger signals contribute to FAA. These short duration meals produce hunger signals with properties of interval timers, analogous to the signal that accumulates with sleep deprivation [33]. Fourth: there is a significant and possibly additive interaction between photic and food-related cues in the control of activity. The underlying mechanisms are accessible to exploration.

2. The brain and body interact to determine anticipatory behavior

We suggest a shift away from the hypothesis of a neural circuit entrained to food cues and propose that anticipatory behaviors can best be understood as part of a dynamical system involving integration of signals from oscillators in both brain and body. Such oscillators entail both the well established clock genes and the newly recognized biochemical oscillators that do not entail genetic mechanisms [8, 9]. The phase of these oscillators can be set (learned) by regularly or irregularly timed cues originating in either the body or the external environment. The phase relationships among these bodily oscillators are set by the SCN when food-derived, learned and environmental photic cues are in appropriate phase with the animal‘s activity. In contrast, the phase relationships among bodily oscillators are set by food-derived and learned signals, but not by the SCN, when these cues are out of phase with the animal‘s SCN regulated activity (Figure 2). In this view, the anticipation of food is an emergent property based on multiple phase setting cues acting on oscillators, genomic and non-genomic, throughout the body. Here we examine learning and memory and its contribution to FAA, and then to better understand the underpinnings, and present evidence for learning and conditioning to periodic events in a slime mold that lacks a central nervous system. Finally, we examine the resilience of FAA in the face of genetic ablations and what this reveals about FEO mechanisms.

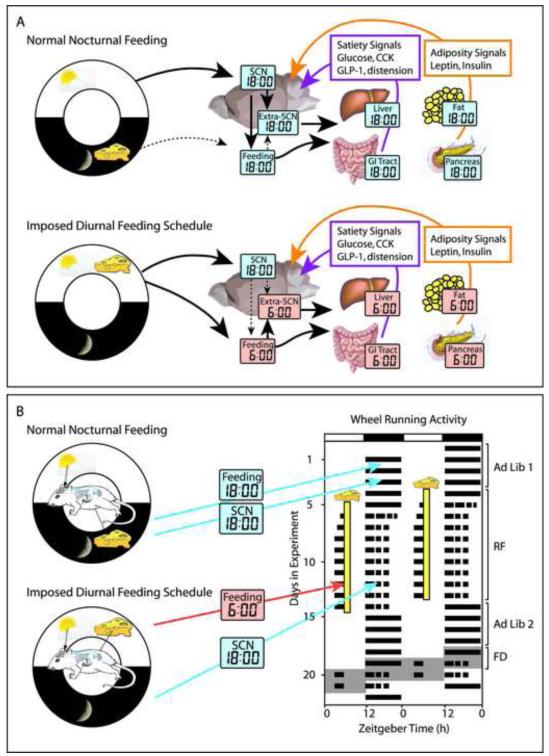

Figure 2.

Cartoon depicting the interaction of light-dark cycle and feeding schedule in modulating circadian rhythms in SCN, extra-SCN brain sites, liver, gastrointestinal tract, fat tissue, and pancreas. The day-night cycle is shown schematically in the white and black ring bearing a sun and moon. A, upper panel. Under normal conditions, food is available and is eaten at night (represented by clocks set to mid-dark phase - zeitgeber time; ZT18). The extra-SCN oscillators in the brain and body are entrained by cues from both the SCN and from rhythmic feeding. A, bottom panel. When food is presented only during the day the phase of the SCN does not change, but that of feeding behavior and peripheral oscillators shift to the new phase (ZT6). Signals from the periphery to the brain are altered in phase. B. In parallel to effects on central and peripheral oscillators, the light-dark cycle and feeding schedules also modulate locomotor activity and FAA. This is seen in a schematic actogram on the right of a rodent showing nocturnal activity in ad lib conditions, and FAA in anticipation of diurnal food presentation during restricted feeding (RF). Upon restoration of ad libitum feeding, nocturnal activity resumes. Recovery of FAA is seen during the subsequent period of food deprivation (FD). The actogram is plotted on a 48 h scale for ease of visualization; black bars represent periods of activity, and the light-dark cycle is illustrated at the top.

2.1. FAA entails learning and memory

It takes about a week to establish regular FAA indicating that like other examples of learning, several experiences may be necessary for the learning to be complete. Additionally, when there are multiple feedings in a 24 hour period, animals come to anticipate each meal at the appropriate phase [34, 35]. Importantly, once established, this learned response is remembered even after a considerable delay. Yoshihara et al. [36] established FAA by restricting feeding to an arbitrary brief period of the day. Once FAA was established the animals were put on ad libitum feeding for as many as 10 days. During the period of free food access, there was no unusual activity during the day. However, once the animals were food deprived, anticipatory activity immediately reemerged at the time of day that had previously been associated with food availability. The memory for the phase at which food is available is an enduring one. This sort of learning is not restricted to situations where food availability is spaced 24 hours apart. Animals come to anticipate food at intervals ranging from seconds to days. In Pavlovian conditioning experiments food can follow another food at regular intervals or regularly follow an arbitrary cue after seconds or minutes [37]. As in FAA, times of food availability are learned [37, 38] and activity [39, 40] as well as feeding related signals [41] occur in anticipation. For example, Timberlake [40] has documented that when cues signal relative remoteness from food, general activity increases but as food becomes more proximal, behaviors become more and more focused on localized search and consummatory responses. Similarly, feeding signals change as the temporal proximity to food increases, including signals important for meal regulation such as insulin, ghrelin and glucagon-like peptide-1 (GLP-1) (see for [41]for review)

There is considerable debate about the mechanisms underlying timing of noncircadian intervals [42-46]. The search for a “clock” that underlies such timing has not yet yielded a specific locus. At a behavioral level, there is evidence that multiple mechanisms probably exist [44] and that some of these mechanisms have the properties of oscillators that can be reset by arbitrary cues [46, 47]. Such a view requires that there be collections of oscillators appropriate for timing of an infinite number of arbitrary intervals. Below, we suggest that recent data on timing outside of and even without a nervous system opens the possibility that the timing mechanisms do not rely on fixed period oscillators but rather become tuned to the periodic structure of environmental changes.

An example of how such mechanisms might operate is seen in the behavior of a simple organism, the slime mold.

2.2. Anticipation as a no-brainer

A notion we challenge is the assumption that the mechanisms supporting FAA are restricted to the CNS, and draw on literature from simple organisms to make this point. In order to investigate primitive forms of functions such as learning, memory, anticipation, and recall, that are most often ascribed to brain, slime mold were exposed to periodic changes in ambient conditions and behavioral responses were measured [48]. They note that “…from an evolutionary perspective, information processing by unicellular organisms might represent a simple precursor of brain dependent higher functions. Anticipating and recalling events are two such functions.”

In the study that accompanied these musings, the authors showed that plasmodia of the true slime mold Physarum could anticipate the timing of periodic events (Figure 3). They reduced their speed of movement (they crawl across agar surfaces at ~1 cm/h) when exposed to three periodic pulses of adverse conditions at constant intervals (30-90 min). When the plasmodia were subsequently subjected to favorable conditions, they spontaneously reduced their locomotive speed at the time when the next unfavorable episode would have occurred. This implied the anticipation of impending environmental change and implies that simple dynamics might be sufficient to explain its emergence. With this idea in mind, we can revisit the conceptual requirements for FEOs that might constrain and delineate the search for mechanisms mediating FAA.

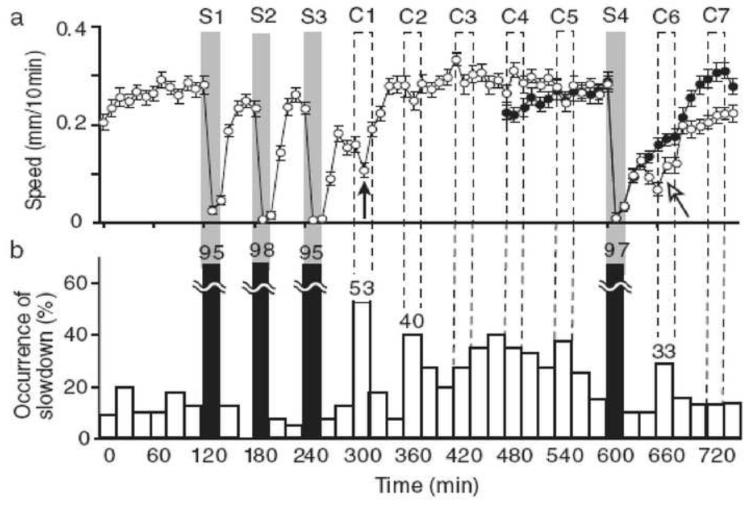

Figure 3.

When the plasmodia were subject to unfavorable conditions, they slowed their movements. When subsequently subjected to favorable conditions, they spontaneously reduced their locomotive speed at the time when the next unfavorable episode would have occurred. This implies anticipation of impending environmental change. The graphs show the average speed (a) and occurrence of slowdowns (b) . Points S1–S4 indicate the times of the real stimulations, whereas points C1–C7 indicate the times of the virtual stimulations. Reprinted with permission from Saigusa T, Tero A, Nakagaki T, Kuramoto Y. Physical Review Letters 100:018101. ©2008 by the American Physical Society.

2.3. Circadian oscillation in the absence of genes, transcription, translation

While transcription clearly plays a pivotal role in maintaining circadian clocks, over the years, there have been many phenomena indicating that circadian rhythms can occur in animals and in individual cells in the absence of transcription. Some organisms, including yeast and C. elegans have clocks but seem to lack “clock” genes. During cell division, transcriptional activity shuts down, but the clock resumes afterwards without resetting (reviewed in [49].

To understand the relevance of such findings to the problem of food anticipation and FEOs, consider the behavior of animals bearing mutations in core clock genes, such that they no longer show circadian rhythms in locomotor activity. The question is whether a functioning genetic clock is necessary for FEOs. In the first of such studies of clock mutant animals, we reported that food-entrained circadian rhythms are sustained in arrhythmic Clk/Clk mutant mice [50] (Figure 4). The Clk mutation is a dominant negative that dimerizes with other clock genes and binds DNA normally, but does not initiate transcription [51, 52]. Furthermore, Clk/Clk mutant mice exhibit FAA, even though at the same time, their circadian locomotor behavior is arrhythmic (Figure 4). As in wildtype controls, FAA in Clk/Clk mutants persists after temporal feeding cues are removed for several cycles, indicating that the FEO is a circadian timer. We noted that “This is the first demonstration that the Clock gene is not necessary for the expression of a circadian, food-entrained behavior and suggests that the FEO is mediated by a molecular mechanism distinct from that of the SCN” (emphasis added). While the idea had experimental support, there seemed to be no plausible way to pursue such a hypothesis at the time of the study. Numerous other studies of mice bearing mutations in the clock genes and proteins and clock controlled genes have been done since that initial work (reviewed in [25]). We also note that clock mutants have no difficulty anticipating feeding at much shorter intervals between opportunities [53]. The weight of evidence indicates that food anticipation can continue in clock mutant animals and in the absence of a functional circadian clock.

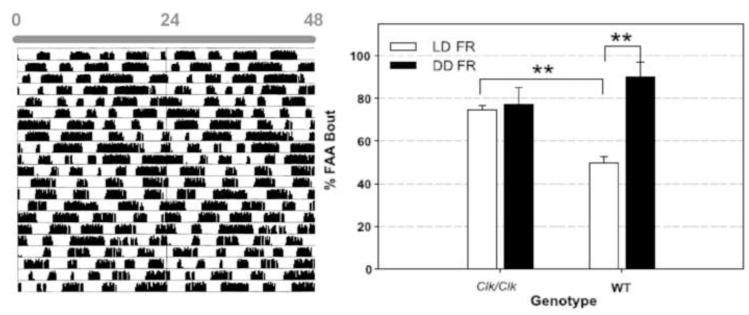

Figure 4.

Left panel. Actogram depicts wheel-running of an arrhythmic Clk/Clk mutant mouse when housed in constant darkness (DD). Right panel. Even though the animal is arrhythmic in DD, Clk/Clk animals, like their wild type counterparts show FAA under food restricted (FR) conditions. Note that Clk/Clk animals FAA is not affected by the light:dark (LD) cycle, while that of wild type animals is reduced in LD. From Pitts S, Perone E, Silver R (2003) Food-entrained circadian rhythms are sustained in arrhythmic Clk/Clk mutant mice. American Journal of Physiology. 285:R57-67. Am Physiol Soc, used with permission.

The breakthrough that may enable examination of how circadian timing in mammals can persist even when clock genes are not transcribed into RNA has now been reported [8, 9]. Such mechanisms had been described previously in cyanobacteria, but until this year, they were thought to be restricted to bacteria [54]. Human red blood cells (RBC‘s) lack a nucleus and therefore have no genes to transcribe. RBC‘s have antioxidant proteins called peroxiredoxins that control levels of reactive oxygen species (ROS). Pairs of peroxiredoxin proteins bind and separate with a circadian rhythm. This cycle can be entrained to temperature cycles, is maintained in constant conditions and is temperature compensated (period is unchanged regardless of temperature). ATP levels in red blood cells are also rhythmic, suggesting a relationship to metabolic pathways. Cells from mice with mutated clock genes have altered peroxiredoxin rhythms, and conversely, cell lines in which expression of peroxiredoxins is disrupted have distorted circadian rhythms. These studies provide key evidence that the genetic and metabolic clock regulators interact (Figure 5). Given that these proteins are highly conserved across major phylogenic kingdoms (eukaryotes, archaea, and bacteria), they may be poised to play a fundamental role in regulating circadian clocks.

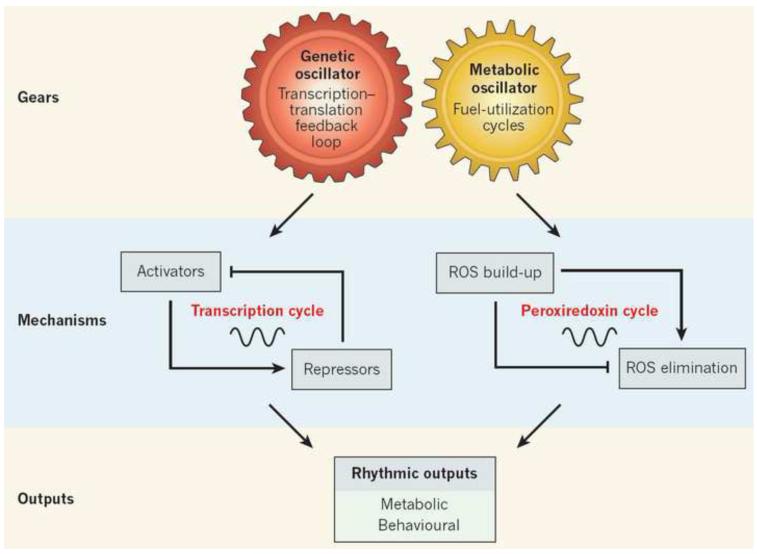

Figure 5.

Cartoon depicts two coupled circadian oscillator, genetic and metabolic, maintain synchrony between the light–dark environment and internal biochemical processes. The metabolic oscillators, which are involved in fuel-utilization cycles and consist of the cycle of oxidation and reduction of peroxiredoxin enzymes. The two oscillator types both drive rhythmic outputs in synchrony with Earth’s rotation. ROS, reactive oxygen species. Reprinted by permission from Macmillan Publishers Ltd: Nature, Bass and Takahashi, Circadian rhythms: redox redux, ©2011.

2.4. Anticipatory responses in peripheral cells

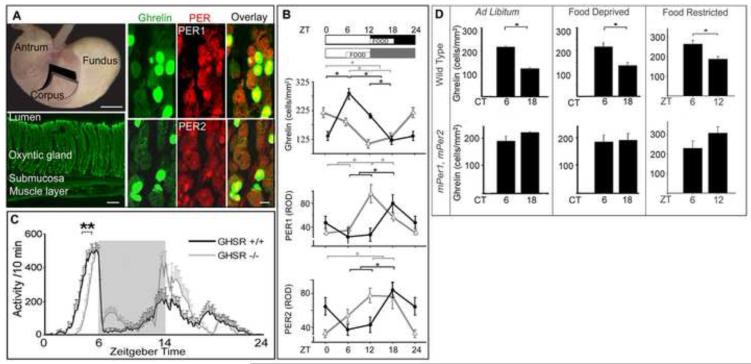

Peripheral cells and organs can anticipate periodic events. A change in the time of feeding can reset the phase of peripheral oscillators in the stomach, liver, kidney, pancreas and heart [4, 55, 56]. Our studies of ghrelin point to the kind of information that we can glean by regulating the time of food access. Ghrelin is a hormone secreted primarily by the stomach and small intestine. Plasma levels of ghrelin fluctuate diurnally, with a peak in the day and a trough at night in rats [57] and superimposed on a diurnal rhythm are smaller acute peaks that anticipate meals. Ghrelin‘s physiological role as a stimulant of food intake has been extensively studied [58-60]. It is released in anticipation of meals, and exogenous administration increases hunger and meal size. Because of the periodic ghrelin peaks that precede meals and the presence of ghrelin receptors in the brain, we investigated the role of ghrelin in regulating food anticipatory activity. Ghrelin cells of the oxyntic glands of the stomach contain clock genes, and both ghrelin content and clock gene expression are rhythmic. Importantly, the phase of rhythmic expression is controlled by feeding time rather than by the light-dark cycle (Fig 6). Data from ghrelin receptor knockout mice supports a role for ghrelin in communicating food availability timing to the brain. The anticipatory wheel running activity in these animals is attenuated under a food restriction paradigm; they also begin their food anticipatory activity later than do wild type animals of the same strain (Fig 6). The rhythm in stomach ghrelin content is abolished in clock deficient (mPER1-mPER2 mutant) mice, demonstrating the importance of clock genes in the regulation of ghrelin content, and presumably its secretion, in the gastric oxyntic cells [55]. Ghrelin‘s orexigenic effects may be due to increased gastrointestinal mobility and decreased insulin secretion [61]. Most studies indicates that ghrelin is greatly reduced in patients with bariatric surgery compared to those who are lean, normal weight, overweight, or obese [62]. While we have focused here on ghrelin, timing mechanisms can engage a multitude of bodily oscillators to regulate food anticipation.

Figure 6.

Circadian rhythms of ghrelin and clock gene expression in oxyntic cells. A, Top left. Image of the mouse stomach, indicating the corpus region where tissue was harvested (upper panel, scale bar = 500μm). Bottom left. Photomicrograph of a cross section of the stomach wall (lower panel, scale bar = 100 μm). Right panels: Photomicrographs of the stomach oxyntic gland stained for ghrelin, PER1 (upper panel) or PER2 (lower panel) and the overlay in optical sections (z axis=2 μm, scale bar = 10 μm). B. The time of food availability determines the phase of ghrelin, PER1 and PER2 rhythm. The schematic shows the 12:12 LD cycle and the time of food availability. The graphs show level of oxyntic cells expression of ghrelin, PER1 and PER2 respectively for animals fed at either ZT12-18 (black) or ZT6-12 (grey). * p<0.01. C. Group activity profiles show amount of wheel running during the last 7 days of restricted feeding in GSHR+/+ (black) and GSHR -/- mice (grey). The data are plotted in10min bins (mean ± SEM). ** p=0.002, difference between GSHR+/+ and GSHR-/- in onset time of activity. D. Comparison of ghrelin levels in wild type and mPer1, mPer2 clock mutant animals lacking circadian rhythms. Number of oxyntic cells expressing ghrelin in animals housed in LD and then placed in DD for 2 days and either fed ad libitum (left panels) or food deprived 24h (middle panels) or during food restriction (right panels). Wild type animals are shown in upper panels and mPer1, mPer2 animals in bottom panels. *p<0.05, **p<0.01. Adapted from [55].

While the circadian oscillations of oxyntic cells and their secretory product is interesting, many other peripheral factors produced by cells and tissues bearing circadian oscillators contribute food-derived signals that influence food anticipation and eating behavior. The circadian rhythm of adrenal corticoid secretion is a well studied example of control by oscillators both centrally in the SCN and peripherally in the adrenal (summarized in [63]). The SCN activates rhythmic release of corticotrophin-releasing hormone from the paraventricular nucleus (PVN) that evokes circadian adrenocorticotropin hormone (ACTH) release from hypophyseal adrenocorticotrophs [64]. ACTH, in turn, regulates circadian corticoid release from the adrenal cortex. Neuronal signals generated by the SCN propagate through the autonomic nervous system to the adrenal cortex to contribute to the circadian regulation of glucocorticoid production [65]. The adrenal cortex exhibits a daily rhythm in sensitivity to ACTH as measured by corticosterone secretion [66]. Adrenal corticosterone levels are rhythmic and peak before dark onset, in anticipation of feeding [67]. Animals with food available in the daytime show a phase advance in corticoid peak levels to the pre-feeding time [67, 68]. Corticosterone in turn has a stimulatory effect on food intake, and in the presence of insulin, on preference for fat intake [69].

Other examples of peripheral oscillators include apolipoprotein A-IV (apo A-IV) and insulin. Apo A-IV, synthesized by both the intestine and liver in rodents, [70], has a circadian pattern of release with secretion increasing just before feeding at dark onset and peaking midway through the dark period [71]. Intestinal release of apo A-IV is controlled by the timing of meals, with levels increasing before meal onset. Insulin concentrations showed diurnal fluctuations in rats [72]. Insulin levels increase during the meal [72], although there is also a fast insulin response to food presentation known as the cephalic phase [73-75]

2.5. Interaction between photic and food-related cues in FAA

Important in the present context is the fact that the light and food differ in their effects on peripheral vs. central oscillators. The circadian phases of clock genes in peripheral tissues are mainly dominated by food cues [4, 56, 76], though simultaneously shifting the feeding schedule and the light:dark cycle markedly enhances the feeding-induced resetting of peripheral clocks [77]. Another indication that daily activity is regulated by signals related to both food and light, perhaps additively, is seen in records of wheel-running prior to and following imposition of restricted food availability. The amount of activity stays approximately constant, though it following food restriction, a portion is shifted to the daytime interval associated with food anticipation (Fig. 7). Though they have been constrained by the absence of evidence on the nature of FEOs, numerous strategies have been applied to the exploring interactions between light and food entrained oscillators. In one study of intact rats, food access was scheduled at the different phases of the LD cycle [78]. Both food and light provided entraining signals, and coupling was assessed by removal of one Zeitgeber (time giver, synchronizing cue), or by phase shifting of one Zeitgeber and removing the other, or by phase shifting both Zeitgebers, and measuring phase displacements and changes in the period of activity rhythms. The results supported the idea of internal coupling, albeit asymmetric, between separate food and light entrained circadian pacemaking systems. Subsequent work supports this general view. When food is available ad libitum, animals are entrained to the LD cycle. When all photic cues are removed, in constant darkness, the FEO predominates, and behavior is entrained to the time of feeding [79, 80].

Figure 7.

Left. Wheel running activity of a mouse in a light:dark cycle fed ad libitum and then given access to food for 6 h/day. Time of food availability indicated by grey shading. Following food restriction, the distribution of activity changes. Right. There is no significant difference in the amount of daily activity when mice are shifted from ad libitum to the restricted feeding condition (n=9; t8 = 1.15, p=0.3; data are averaged over 6 days in each condition).

While the evidence supports an interaction of two kinds of oscillators in regulating activity rhythms, disentangling the contributions of LEO and FEO, and sorting out direct and indirect effects on activity of these separate Zeitgebers is difficult. Light can alter the output measure indirectly, by altering the amount of activity. Increased light intensity inhibits activity in nocturnal animals, a process termed masking [81]. As such the light intensity during activity recording can affect the amplitude of the underlying response [25]. For example, constant light enhances apparent rhythmicity in genetically arrhythmic mice [82]. Conversely, change in food alters behavioral rhythmicity: food and water restriction rescues activity rhythms in animals rendered arrhythmic by constant light [83]. Another confound rests on the fact that the amount of wheel running can alter the energetics of the animal and alters hunger signals and circulating metabolic markers. The discovery of peroxiredoxin rhythms and their possible use as markers for FEOs may help to disentangle these parameters.

3. Summary

Individuals detect changes in internal and external signals that occur as a consequence of the brain and body preparing for an impending meal, and interpret those changes as “hunger.” These responses are based on dynamic brain-body interactions. Signals that reliably precede food organize behavioral and physiological responses that prepare the animal for food seeking, procurement, consumption and ultimately for the extraction of energy following ingestion. We now have new opportunities to study the mechanisms whereby metabolic, circadian and photic factors interact. It is an open question as to whether there is a single common pathway for output modulated by all signals.

Highlights.

Learning and circadian oscillators underlie the development of food anticipatory behavior

There are two circadian oscillator mechanisms, metabolic and transcriptional

Anticipatory behavior occurs in the absence of nervous systems

Cues from peripheral oscillators comprise a major component of entrainment to food

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by grants MH075045, NS37919 (to RS), and MH068073 (to PDB).

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- [1].Weaver DR. The suprachiasmatic nucleus: a 25-year retrospective. J. Biol. Rhythms. 1998;13:100–12. doi: 10.1177/074873098128999952. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [2].Ko CH, Takahashi JS. Molecular components of the mammalian circadian clock. Hum. Mol. Genet. 2006;15(Spec No 2):R271–7. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddl207. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [3].Schibler U, Sassone-Corsi P. A web of circadian pacemakers. Cell. 2002;111:919–22. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(02)01225-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [4].Damiola F, Le Minh N, Preitner N, Kornmann B, Fleury-Olela F, Schibler U. Restricted feeding uncouples circadian oscillators in peripheral tissues from the central pacemaker in the suprachiasmatic nucleus. Genes Dev. 2000;14:2950–61. doi: 10.1101/gad.183500. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [5].Schibler U, Ripperger J, Brown SA. Peripheral circadian oscillators in mammals: time and food. J Biol Rhythms. 2003;18:250–60. doi: 10.1177/0748730403018003007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [6].Lakin-Thomas PL. Transcriptional feedback oscillators: maybe, maybe not. J Biol Rhythms. 2006;21:83–92. doi: 10.1177/0748730405286102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [7].Roenneberg T, Merrow M. Life before the clock: modeling circadian evolution. J Biol Rhythms. 2002;17:495–505. doi: 10.1177/0748730402238231. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [8].O’Neill JS, Reddy AB. Circadian clocks in human red blood cells. Nature. 2011;469:498–503. doi: 10.1038/nature09702. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [9].O’Neill JS, van Ooijen G, Dixon LE, Troein C, Corellou F, Bouget FY, et al. Circadian rhythms persist without transcription in a eukaryote. Nature. 2011;469:554–8. doi: 10.1038/nature09654. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [10].Johnson CH, Mori T, Xu Y. A cyanobacterial circadian clockwork. Curr Biol. 2008;18:R816–R25. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2008.07.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [11].Klein DC, Moore RY, Reppert SM. The Mind’s Clock. Oxford University Press; New York: 1991. Suprachiasmatic Nucleus. [Google Scholar]

- [12].Stephan FK, Swann JM, Sisk CL. Anticipation of 24-hr feeding schedules in rats with lesions of the suprachiasmatic nucleus. Behav Neural Biol. 1979;25:346–63. doi: 10.1016/s0163-1047(79)90415-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [13].Mistlberger RE. Circadian food-anticipatory activity: formal models and physiological mechanisms. Neuroscience and biobehavioral reviews. 1994;18:171–95. doi: 10.1016/0149-7634(94)90023-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [14].Stephan FK. The“other” circadian system: food as a Zeitgeber. J Biol Rhythms. 2002;17:284–92. doi: 10.1177/074873040201700402. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [15].Stephan F. Limits of entrainment to periodic feeding in rats with suprachiasmatic lesions. J Comp Physiol. 1981;143:401–10. [Google Scholar]

- [16].Boulos Z, Logothetis DE. Rats anticipate and discriminate between two daily feeding times. Physiol Behav. 1990;48:523–9. doi: 10.1016/0031-9384(90)90294-e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [17].Stephan FK. Entrainment of activity to multiple feeding times in rats with suprachiasmatic lesions. Physiol Behav. 1989;46:489–97. doi: 10.1016/0031-9384(89)90026-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [18].Richter CP. Sleep and activity: their relation to the 24-hour clock. Res Publ Assoc Res Nerv Ment Dis. 1967;45:8–29. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [19].Davidson AJ. Lesion studies targeting food-anticipatory activity. Eur J Neurosci. 2009;30:1658–64. doi: 10.1111/j.1460-9568.2009.06961.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [20].Davidson AJ. Search for the feeding-entrainable circadian oscillator: a complex proposition. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol. 2006;290:R1524–6. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.00073.2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [21].Hastings MH. Central clocking. Trends Neurosci. 1997;20:459–64. doi: 10.1016/s0166-2236(97)01087-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [22].Davidson AJ, Poole AS, Yamazaki S, Menaker M. Is the food-entrainable circadian oscillator in the digestive system? Genes Brain Behav. 2003;2:32–9. doi: 10.1034/j.1601-183x.2003.00005.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [23].Fuller PM, Lu J, Saper CB. Differential rescue of light- and food-entrainable circadian rhythms. Science. 2008;320:1074–7. doi: 10.1126/science.1153277. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [24].Escobar C, Cailotto C, Angeles-Castellanos M, Delgado RS, Buijs RM. Peripheral oscillators: the driving force for food-anticipatory activity. Eur J Neurosci. 2009;30:1665–75. doi: 10.1111/j.1460-9568.2009.06972.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [25].Challet E, Mendoza J, Dardente H, Pevet P. Neurogenetics of food anticipation. Eur J Neurosci. 2009;30:1676–87. doi: 10.1111/j.1460-9568.2009.06962.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [26].Verwey M, Amir S. Food-entrainable circadian oscillators in the brain. Eur J Neurosci. 2009;30:1650–7. doi: 10.1111/j.1460-9568.2009.06960.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [27].Carneiro BT, Araujo JF. The food-entrainable oscillator: a network of interconnected brain structures entrained by humoral signals? Chronobiol Int. 2009;26:1273–89. doi: 10.3109/07420520903404480. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [28].Silver R, Lesauter J. Circadian and homeostatic factors in arousal. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2008;1129:263–74. doi: 10.1196/annals.1417.032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [29].Mendoza J, Challet E. Brain clocks: from the suprachiasmatic nuclei to a cerebral network. Neuroscientist. 2009;15:477–88. doi: 10.1177/1073858408327808. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [30].Honma K, Honma S. The SCN-independent clocks, methamphetamine and food restriction. Eur J Neurosci. 2009;30:1707–17. doi: 10.1111/j.1460-9568.2009.06976.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [31].Pezuk P, Mohawk JA, Yoshikawa T, Sellix MT, Menaker M. Circadian organization is governed by extra-SCN pacemakers. J Biol Rhythms. 2010;25:432–41. doi: 10.1177/0748730410385204. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [32].Mohawk JA, Baer ML, Menaker M. The methamphetamine-sensitive circadian oscillator does not employ canonical clock genes. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2009;106:3519–24. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0813366106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [33].Borbely AA. A two process model of sleep regulation. Hum Neurobiol. 1982;1:195–204. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [34].Bolles RC, Moot SA. The rat’s anticipation of two meals a day. J Comp Physiol Psychol. 1973;83:510–4. doi: 10.1037/h0034666. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [35].Edmonds SC, Adler NT. The multiplicity of biological oscillators in the control of circadian running activity in the rat. Physiol Behav. 1977;18:921–30. doi: 10.1016/0031-9384(77)90202-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [36].Yoshihara T, Honma S, Mitome M, Honma K. Independence of feeding-associated circadian rhythm from light conditions and meal intervals in SCN lesioned rats. Neurosci Lett. 1997;222:95–8. doi: 10.1016/s0304-3940(97)13353-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [37].Balsam P, Sanchez-Castillo H, Taylor K, Van Volkinburg H, Ward RD. Timing and anticipation: conceptual and methodological approaches. Eur J Neurosci. 2009;30:1749–55. doi: 10.1111/j.1460-9568.2009.06967.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [38].Balsam PD, Gallistel CR. Temporal maps and informativeness in associative learning. Trends Neurosci. 2009;32:73–8. doi: 10.1016/j.tins.2008.10.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [39].Kirkpatrick K, Church RM. Tracking of the expected time to reinforcement in temporal conditioning procedures. Learning & Behavior. 2003;31:3–21. doi: 10.3758/bf03195967. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [40].Timberlake W. Motivational modes in behavior systems. In: Klein RRMaSB., editor. Handbook of contemporary learning theories. Erlbaum Associates; Hillsdale NJ: 2001. Hillsdale NJ: Erlbaum Associates. [Google Scholar]

- [41].Vahl TP, Drazen DL, Seeley RJ, D’Alessio DA, Woods SC. Meal-anticipatory glucagon-like peptide-1 secretion in rats. Endocrinology. 2010;151:569–75. doi: 10.1210/en.2009-1002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [42].Buhusi CV, Meck WH. What makes us tick? Functional and neural mechanisms of interval timing. Nature Reviews Neuroscience. 2005;6:755–65. doi: 10.1038/nrn1764. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [43].Crystal JD. Nonlinearities in sensitivity to time: Implications for oscillator-based representations of interval circadian clocks. In: Meck WH, editor. Functional and neural mechanisms of interval timing. CRC Press; New York: 2003. pp. 61–76. [Google Scholar]

- [44].Ivry RB, Schlerf JE. Dedicated and intrinsic models of time perception. Trends Cogn Sci. 2008;12:273–80. doi: 10.1016/j.tics.2008.04.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [45].Ivry RB, Spencer RM. The neural representation of time. Curr Opin Neurobiol. 2004;14:225–32. doi: 10.1016/j.conb.2004.03.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [46].Matell MS, Meck WH. Cortico-striatal circuits and interval timing: coincidence detection of oscillatory processes. Brain Res Cogn Brain Res. 2004;21:139–70. doi: 10.1016/j.cogbrainres.2004.06.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [47].Crystal JD. Theoretical and conceptual issues in time-place discrimination. The European journal of neuroscience. 2009;30:1756–66. doi: 10.1111/j.1460-9568.2009.06968.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [48].Saigusa T, Tero A, Nakagaki T, Kuramoto Y. Amoebae anticipate periodic events. Phys Rev Lett. 2008;100:018101. doi: 10.1103/PhysRevLett.100.018101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [49].Johnson CH, Stewart PL, Egli M. The Cyanobacterial Circadian System: From Biophysics to Bioevolution. Annu Rev Biophys. 2010 doi: 10.1146/annurev-biophys-042910-155317. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [50].Pitts S, Perone E, Silver R. Food-entrained circadian rhythms are sustained in arrhythmic Clk/Clk mutant mice. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol. 2003;285:R57–67. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.00023.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [51].Vitaterna MH, King DP, Chang AM, Kornhauser JM, Lowrey PL, McDonald JD, et al. Mutagenesis and mapping of a mouse gene, Clock, essential for circadian behavior. Science. 1994;264:719–25. doi: 10.1126/science.8171325. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [52].Gekakis N, Staknis D, Nguyen HB, Davis FC, Wilsbacher LD, King DP, et al. Role of the CLOCK protein in the mammalian circadian mechanism. Science. 1998;280:1564–9. doi: 10.1126/science.280.5369.1564. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [53].Cordes S, Gallistel CR. Intact interval timing in circadian CLOCK mutants. Brain Res. 2008;1227:120–7. doi: 10.1016/j.brainres.2008.06.043. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [54].Kondo T. A cyanobacterial circadian clock based on the Kai oscillator. Cold Spring Harb Symp Quant Biol. 2007;72:47–55. doi: 10.1101/sqb.2007.72.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [55].LeSauter J, Hoque N, Weintraub M, Pfaff DW, Silver R. Stomach ghrelin-secreting cells as food-entrainable circadian clocks. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2009;106:13582–7. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0906426106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [56].Stokkan KA, Yamazaki S, Tei H, Sakaki Y, Menaker M. Entrainment of the circadian clock in the liver by feeding. Science. 2001;291:490–3. doi: 10.1126/science.291.5503.490. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [57].Bodosi B, Gardi J, Hajdu I, Szentirmai E, Obal F, Jr., Krueger JM. Rhythms of ghrelin, leptin, and sleep in rats: effects of the normal diurnal cycle, restricted feeding, and sleep deprivation. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol. 2004;287:R1071–9. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.00294.2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [58].Castaneda TR, Tong J, Datta R, Culler M, Tschop MH. Ghrelin in the regulation of body weight and metabolism. Front Neuroendocrinol. 2010;31:44–60. doi: 10.1016/j.yfrne.2009.10.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [59].Horvath TL, Diano S, Sotonyi P, Heiman M, Tschop M. Minireview: ghrelin and the regulation of energy balance--a hypothalamic perspective. Endocrinology. 2001;142:4163–9. doi: 10.1210/endo.142.10.8490. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [60].Saper CB, Chou TC, Elmquist JK. The need to feed: homeostatic and hedonic control of eating. Neuron. 2002;36:199–211. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(02)00969-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [61].Cummings DE, Overduin J. Gastrointestinal regulation of food intake. J Clin Invest. 2007;117:13–23. doi: 10.1172/JCI30227. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [62].Beckman LM, Beckman TR, Earthman CP. Changes in gastrointestinal hormones and leptin after Roux-en-Y gastric bypass procedure: a review. J Am Diet Assoc. 2010;110:571–84. doi: 10.1016/j.jada.2009.12.023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [63].Silver R, Balsam P. Oscillators entrained by food and the emergence of anticipatory timing behaviors. Sleep Biol Rhythms. 2010;8:120–36. doi: 10.1111/j.1479-8425.2010.00438.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [64].Simpson ER, Waterman MR. Regulation of the synthesis of steroidogenic enzymes in adrenal cortical cells by ACTH. Annu Rev Physiol. 1988;50:427–40. doi: 10.1146/annurev.ph.50.030188.002235. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [65].Buijs RM, Wortel J, Van Heerikhuize JJ, Feenstra MG, Ter Horst GJ, Romijn HJ, et al. Anatomical and functional demonstration of a multisynaptic suprachiasmatic nucleus adrenal (cortex) pathway. Eur J Neurosci. 1999;11:1535–44. doi: 10.1046/j.1460-9568.1999.00575.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [66].Ungar F, Halberg F. Circadian rhythm in the in vitro response of mouse adrenal to adrenocorticotropic hormone. Science. 1962;137:1058–60. doi: 10.1126/science.137.3535.1058. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [67].Shen L, Ma LY, Qin XF, Jandacek R, Sakai R, Liu M. Diurnal changes in intestinal apolipoprotein A-IV and its relation to food intake and corticosterone in rats. Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol. 2005;288:G48–53. doi: 10.1152/ajpgi.00064.2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [68].Honma KI, Honma S, Hiroshige T. Critical role of food amount for prefeeding corticosterone peak in rats. Am J Physiol. 1983;245:R339–44. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.1983.245.3.R339. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [69].Dallman MF, la Fleur SE, Pecoraro NC, Gomez F, Houshyar H, Akana SF. Minireview: glucocorticoids--food intake, abdominal obesity, and wealthy nations in 2004. Endocrinology. 2004;145:2633–8. doi: 10.1210/en.2004-0037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [70].Wu AL, Windmueller HG. Relative contributions by liver and intestine to individual plasma apolipoproteins in the rat. J Biol Chem. 1979;254:7316–22. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [71].Fukagawa K, Gou HM, Wolf R, Tso P. Circadian rhythm of serum and lymph apolipoprotein AIV in ad libitum-fed and fasted rats. Am J Physiol. 1994;267:R1385–90. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.1994.267.5.R1385. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [72].La Fleur SE, Kalsbeek A, Wortel J, Buijs RM. A suprachiasmatic nucleus generated rhythm in basal glucose concentrations. J Neuroendocrinol. 1999;11:643–52. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2826.1999.00373.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [73].Berthoud HR, Bereiter DA, Trimble ER, Siegel EG, Jeanrenaud B. Cephalic phase, reflex insulin secretion. Neuroanatomical and physiological characterization. Diabetologia. 1981;20(Suppl):393–401. doi: 10.1007/BF00254508. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [74].Powley TL, Berthoud HR. Diet and cephalic phase insulin responses. Am J Clin Nutr. 1985;42:991–1002. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/42.5.991. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [75].Sadacca LA, Lamia KA, deLemos AS, Blum B, Weitz CJ. An intrinsic circadian clock of the pancreas is required for normal insulin release and glucose homeostasis in mice. Diabetologia. 54:120–4. doi: 10.1007/s00125-010-1920-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [76].Hara R, Wan K, Wakamatsu H, Aida R, Moriya T, Akiyama M, et al. Restricted feeding entrains liver clock without participation of the suprachiasmatic nucleus. Genes Cells. 2001;6:269–78. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2443.2001.00419.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [77].Wu T, Jin Y, Ni Y, Zhang D, Kato H, Fu Z. Effects of light cues on re entrainment of the food-dominated peripheral clocks in mammals. Gene. 2008;419:27–34. doi: 10.1016/j.gene.2008.04.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [78].Stephan FK. Coupling between feeding- and light-entrainable circadian pacemakers in the rat. Physiol Behav. 1986;38:537–44. doi: 10.1016/0031-9384(86)90422-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [79].Mendoza J, Angeles-Castellanos M, Escobar C. A daily palatable meal without food deprivation entrains the suprachiasmatic nucleus of rats. Eur J Neurosci. 2005;22:2855–62. doi: 10.1111/j.1460-9568.2005.04461.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [80].Castillo MR, Hochstetler KJ, Tavernier RJ, Jr., Greene DM, Bult-Ito A. Entrainment of the master circadian clock by scheduled feeding. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol. 2004;287:R551–5. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.00247.2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [81].Mrosovsky N. Masking: history, definitions, and measurement. Chronobiol. Int. 1999;16:415–29. doi: 10.3109/07420529908998717. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [82].Spoelstra K, Oklejewicz M, Daan S. Restoration of self-sustained circadian rhythmicity by the mutant clock allele in mice in constant illumination. J Biol Rhythms. 2002;17:520–5. doi: 10.1177/0748730402238234. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [83].Mistlberger RE. Effects of scheduled food and water access on circadian rhythms of hamsters in constant light, dark, and light:dark. Physiol Behav. 1993;53:509–16. doi: 10.1016/0031-9384(93)90145-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]