Abstract

Objective

To explore the pattern of repeat pregnancies among diagnosed HIV-infected women in the UK and Ireland, estimate the rate of these sequential pregnancies, and investigate the demographic and clinical characteristics of women experiencing them.

Design

Diagnosed HIV-infected pregnant women are reported through an active confidential reporting scheme to the National Study of HIV in Pregnancy and Childhood.

Methods

Pregnancies occurring during 1990-2009 were included. Multivariable analyses were conducted fitting Cox proportional hazards models.

Results

There were 14,096 pregnancies in 10,568 women; 2737 (25.9%) had two or more pregnancies reported. The rate of repeat pregnancies was 6.7 (95% CI: 6.5-7.0) per 100 woman-years. The proportion of pregnancies in women who already had at least one pregnancy reported increased from 20.3% (32/158) in 1997 to 38.6% (565/1465) in 2009 (p<0.001).

In multivariable analysis the probability of repeat pregnancy significantly declined with increasing age at first pregnancy. Parity was also inversely associated with repeat pregnancy. Compared with women born in the UK or Ireland, those from Europe, Eastern Africa, and Southern Africa were less likely to have a repeat pregnancy, while women from Middle Africa and Western Africa were more likely to. Maternal health at first pregnancy was not associated with repeat pregnancy.

Conclusions

The number of diagnosed HIV-infected women in the UK and Ireland experiencing repeat pregnancies is increasing. Variations in the probability of repeat pregnancies, according to demographic and clinical characteristics, are an important consideration when planning reproductive health services and HIV care for people living with HIV.

Keywords: HIV, Women, Pregnancy, Surveillance, Epidemiology, United Kingdom and Ireland

Introduction

A substantial proportion of women living with Human Immunodeficiency Virus (HIV) worldwide are of reproductive age.1 Mother-to-child transmission (MTCT) of HIV can now be prevented almost entirely with interventions including antiretroviral prophylaxis and the avoidance of breastfeeding.2,3 Greatly improved AIDS-free survival in recent years,4 combined with low MTCT rates, has given HIV-infected women in developed countries a greater opportunity for childbearing.

In the United Kingdom (UK) and Ireland the number of pregnancies among HIV-infected women has increased rapidly over the last decade.5 A growing number of these women will have already experienced at least one pregnancy in which they received HIV-related care, and may have further pregnancies. Women with repeat pregnancies may have complex treatment and obstetric histories and are therefore a challenging group to manage. Robust, reliable, nationally representative data on the incidence and predictors of repeat pregnancies among HIV-infected women is important to inform decisions regarding the most appropriate obstetric and therapeutic management of current pregnancies, in light of the probability of further pregnancies, as well as the planning of reproductive health and HIV services for these women.

Little, however, is known about the demographics and health status of diagnosed HIV-infected women experiencing repeat pregnancies. In a European study using data up to 2003, factors predictive of repeat pregnancies included black African ethnicity, younger age and availability of Highly Active Antiretroviral Therapy (HAART), but the limited sample size precluded further analyses.6 Meanwhile, in the United States healthier and younger women were more likely to have repeat pregnancies.7-9

Here we examine patterns of repeat pregnancies among diagnosed HIV-infected women in the UK and Ireland, estimate the rate of these sequential pregnancies, and investigate the demographic and clinical characteristics of women experiencing them.

Methods

Data source

In the UK and Ireland, HIV-infected pregnant women are reported through an active confidential obstetric reporting scheme to the National Study of HIV in Pregnancy and Childhood (NSHPC).5 Paediatric cases of HIV infection and children born to diagnosed mothers are notified through a parallel scheme. Obstetric and paediatric reports are subsequently linked. We used NSHPC data on all pregnancies in diagnosed HIV-infected women during 1990-2009. The NSHPC collects standardised information on maternal demographic characteristics including age, country of birth, ethnicity, previous reproductive history (parity) and timing of diagnosis, clinical factors including CD4 count and presence of HIV/AIDS symptoms, use of antiretroviral therapy (ART), outcome of pregnancy and infant characteristics.

Case definitions

Only pregnancies in women with HIV diagnosed by the time of delivery were included. Timing of diagnosis was classified in relation to each reported pregnancy as prior to or during pregnancy. Pregnancies to women not known to be HIV-infected at the time, and those not reported to the NSHPC e.g. because the woman was not living in the UK or Ireland at the time, were not available for inclusion. ‘First pregnancy’ therefore refers to women’s first pregnancy reported to the NSHPC which is not necessarily their first ever pregnancy. Information on parity (previous live and still births) was, however, collected. Reported pregnancies were included in the analysis whatever their outcome. World regions were defined using United Nations classifications,10 with sub-Saharan Africa sub-divided due to the high proportion of HIV-infected pregnant women originating from this region.5 Pregnancy year was defined as the year of conception, based on the date of last menstrual period.

Women were grouped as those with repeat pregnancies (two or more), and those with a single pregnancy. To take account of the fact that not all women were ‘at risk’ of a repeat pregnancy during the study period, women whose first pregnancy ended on or after the end of the study period (31st December 2009) were excluded when comparing the characteristics of women with repeat pregnancies and those with a single pregnancy only, as were women who died following their first pregnancy. Women who were reported to have gone abroad before the end of their pregnancy were not excluded as they could return to the UK or Ireland at a later date.

Statistical analyses

Initial trends analyses were conducted on all pregnancies during 1990-2009. The repeat pregnancy rate was estimated per 100 woman-years. The numerator was the total number of repeat pregnancies reported including second, third and subsequent pregnancies. The denominator ‘time at risk of subsequent pregnancies’ was calculated as the sum of the time between the end date of each woman’s first pregnancy to the end of the study period, the end of reproductive life defined as turning age 50, or the date of death reported to the NSHPC – whichever occurred first. Women were not ‘at risk’ for the duration of any subsequent pregnancies during their overall time at risk. For the estimation of the rate of second pregnancies women’s time ‘at risk’ ended at the start of their second pregnancy, if they experienced one.

Kaplan–Meier analyses were used to explore the probability of repeat pregnancies. Differences between time periods were assessed with the log rank test. For this analysis women were censored at four years after their first pregnancy, rather than the end of the study period, to allow for the limited duration of time ‘at risk’ among women who had their first pregnancy during the most recent time period (2005-2009). To ensure that the Kaplan–Meier assumption of non-informative censoring was met, for this analysis, and subsequent Cox proportional hazards modelling, women were not censored at the end of their reproductive life. The proportional hazards assumption was checked by comparing the Kaplan–Meier plots with the predicted plots by time period.11

Birth spacing intervals were estimated in two ways. Birth-to-birth intervals; the duration between the dates of consecutive live birth deliveries, and birth-to-conception intervals; the duration between the date of delivery (live births only) and start of the subsequent pregnancy (regardless of the outcome).12

Analyses comparing the characteristics of women with a single pregnancy with those having repeat pregnancies were restricted to women whose first pregnancy occurred during 2000-2009 to ensure that findings were reflective of the more recent epidemiological and clinical situation, with widespread antenatal HIV testing and the availability of HAART.5,13 For the descriptive comparative analyses, the χ2 test, χ2 test for trend, and Wilcoxon-Mann-Whitney test were used as appropriate. Cox proportional hazards models were used to investigate characteristics associated with having a repeat pregnancy during 2000-2009. Multivariable models were built using a forward-fitting approach. The likelihood ratio test was used to determine whether variables improved the fit of the model using a significance level of p<0.05. Year of first pregnancy was included in the model a priori to take account of changes, for example in the management of women, over the study period. The proportional hazards assumption was assessed by examining log-log plots and analyzing the model’s Schoenfeld residuals.11 Analyses were conducted using Stata 11.0 (Stata Corp., College Station, TX, USA).

Results

In the UK and Ireland during 1990-2009 14,096 pregnancies were reported in 10,568 diagnosed HIV-infected women. In total, 2737 (25.9%) women had repeat pregnancies (2117 women had two pregnancies, 475 had three and 145 had four or more). Of the 13,355 pregnancies with a recorded outcome, 11,915 (89.2%) resulted in a live birth, 121 (0.9%) in a still birth, 1317 (9.9%) in either a miscarriage or termination, and two women (0.01%) were reported to have died. Outcome was not known for 741 pregnancies, including 146 which were continuing to term, and 183 where the woman was known to have gone abroad before delivery.

Both the number and proportion of repeat pregnancies (i.e. pregnancies to women who already had at least one pregnancy reported) increased; from 20.3% (32/158) in 1997 to 38.6% (565/1465) in 2009 (p<0.001). In 2009, 28.2% of all pregnancies were second pregnancies, 7.4% were third, and 2.9% were fourth or subsequent (figure 1).

Figure 1.

Proportion of first and subsequent pregnancies by year, 1990-2009

The rate of all repeat pregnancies was 6.7 (95% CI: 6.5-7.0) per 100 woman-years (3528 repeat pregnancies during 52,676 woman-years). The rate of second pregnancies was also 6.7 (95% CI:6.5-7.0) per 100 woman-years (2737 second pregnancies during 40,760 woman-years).

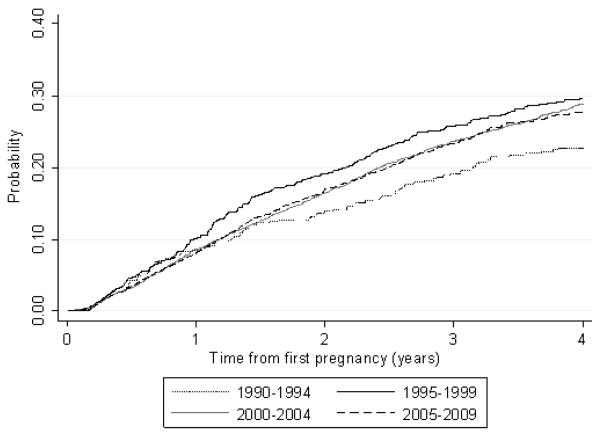

Kaplan–Meier analysis of time to second pregnancy (third and subsequent pregnancies were excluded) showed differences between calendar periods (log rank test: p=0.06). As shown in figure 2, women having their first pregnancy during the earliest time period (1990-1994) were least likely to have a second pregnancy while those whose first pregnancy occurred during 1995-1999 were most likely to. The probability of having a second pregnancy was very similar among women whose first pregnancy occurred during 2000-2004 and 2005-2009.

Figure 2.

Kaplan-Meir analysis of the probability of having a second pregnancy by time period*, 1990-2009

*Of women's first reported pregnancy

The median birth-to-birth interval among live births during 1990-2009 was 2.7 years (inter-quartile range (IQR):1.7-4.1) between first and second deliveries, 2.3 years (IQR:1.5-3.9) between second and third, and was also 2.3 years (1.5-3.7) between third and fourth deliveries. The pattern of live birth-to-conception intervals was similar; the median interval between first live birth and subsequent pregnancy was 1.9 years (IQR: 1.0-3.3), it was1.6 years (IQR: 0.7-3.0) between second live birth and subsequent pregnancy, as was the interval between the third live birth and subsequent pregnancy (1.6 years (IQR:0.7-3.0). When the analyses were restricted to women whose first live birth occurred during 2000 or later, the findings were similar; the median birth-to-birth interval between first and second delivery was 2.6 years (IQR:1.7-3.9), and the birth-to-conception interval was 1.8 years (IQR:0.9-3.1).

Analyses of the predictors of repeat pregnancy were restricted to women whose first pregnancy occurred during 2000-2009 and also excluded 651 women with a single pregnancy who were not ‘at risk’ of repeat pregnancy during the study period. A total of 11,426 pregnancies among 8661 women (2238 (25.8%) with repeat pregnancies) were thus included.

Demographic and clinical characteristics of women with and without repeat pregnancies are compared in Table 1. Women with repeat pregnancies were more likely to have had their first pregnancy earlier in the study period, they were younger (at their first reported pregnancy), and a higher proportion originated from the UK or Ireland (14.1% vs. 12.3%). Half of women with repeat pregnancies were nulliparous at their first reported pregnancy, significantly more than among women with a single pregnancy. Women with repeat pregnancies were less likely to have been diagnosed prior to their first pregnancy. There were no significant differences between the two groups with respect to reported HIV/AIDS symptoms or CD4 counts; around 45% of women in both groups had CD4 counts <350 cells/μl in their first pregnancy. However, some treatment differences were apparent, with a lower proportion of women with repeat pregnancies conceiving their first pregnancy while on treatment (among those diagnosed prior to that pregnancy). Women with missing information on any demographic variable were slightly younger, more likely to be white UK (or Ireland)-born women, and less likely to have repeat pregnancies (21.9% vs. 26.7%, p<0.001) than those with complete information.

Table 1.

Comparison of the demographic and clinical characteristics of women with a single pregnancy and those with repeat pregnancies, 2000-2009

| Characteristic | Number of women with a single pregnancy (%) |

Number of women with repeat pregnancies (%) |

p-value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Total | 6423 (100) | 2238 (100) | - |

|

| |||

| Year | |||

| 2000-2002 | 1254 (19.5) | 815 (36.4) | <0.001 |

| 2003-2005 | 2208 (34.4) | 912 (40.8) | |

| 2006-2009 | 2961 (46.1) | 511 (22.8) | |

|

| |||

| Age (years)* (n=8618) | |||

| Median (IQR) | 29.9 (26.1-34.0) | 27.9 (24.4-31.5) | <0.001 |

|

| |||

| Ethnic group (n=8591) | |||

| White | 819 (12.9) | 287 (12.8) | 0.590 |

| Black African | 5019 (79.0) | 1754 (78.4) | |

| Other | 515 (8.1) | 197 (8.8) | |

|

| |||

| Region of birth (n=8488) | |||

| UK and Ireland | 771 (12.3) | 315 (14.1) | <0.001 |

| Europe | 209 (3.3) | 52 (2.3) | |

| Eastern Africa | 2878 (46.0) | 895 (40.0) | |

| Middle Africa | 396 (6.3) | 217 (9.7) | |

| Western Africa | 954(15.3) | 458 (20.5) | |

| Southern Africa | 576 (9.2) | 161 (7.2) | |

| Africa (unspecified) | 105 (1.7) | 10 (0.5) | |

| Elsewhere | 362 (5.8) | 129 (5.8) | |

|

| |||

| HIV risk factor (n=8060) | |||

| Injecting drug use | 138 (2.4) | 49 (2.3) | 0.793 |

| Other** | 5742 (97.7) | 2131 (97.8) | |

|

| |||

| Parity* (n=7652) | |||

| Nulliparous | 2326 (40.7) | 987 (50.9) | <0.001 |

| 1 | 2921 (33.6) | 596 (30.7) | |

| 2 | 916 (16.0) | 244 (12.6) | |

| 3+ | 547 (9.6) | 115 (5.9) | |

|

| |||

| CD4 count (cells/μl)† (n=7173) | |||

| ≥500 | 1529 (28.9) | 532 (28.3) | 0.953 |

| 350-499 | 1398 (26.4) | 493 (26.3) | |

| 200-349 | 1568 (29.6) | 562 (29.9) | |

| <200 | 800 (15.1) | 291 (15.5) | |

|

| |||

| HIV/AIDS symptoms* (n=7530) | |||

| Yes | 156 (2.8) | 59 (2.9) | 0.822 |

| No | 5358 (97.2) | 1957 (97.1) | |

|

| |||

| Timing of HIV diagnosis (n=8337) | |||

| Prior to first reported pregnancy | 2760 (43.4) | 855 (38.4) | <0.001 |

| During first reported pregnancy | 3599 (56.6) | 1373 (61.6) | |

|

| |||

| Antenatal ART*†† (n=3473) | |||

| From before conception | 1320 (49.6) | 374 (46.0) | 0.031 |

| Started during pregnancy | 1202 (45.2) | 381 (46.8) | |

| Untreated | 137 (5.2) | 59 (7.3) | |

PMTCT – Prevention of Mother-to-Child Transmission

At first reported pregnancy

Other risk includes heterosexual, ‘from a high HIV prevalence area’, and vertical transmission

Earliest CD4 count measurement during first reported pregnancy

Among women diagnosed prior to their first reported pregnancy only

In the multivariable analysis of demographic characteristics associated with having repeat pregnancies (table 2), the final model included maternal region of birth and year of pregnancy, maternal age and parity at first pregnancy. There was no association between year of first pregnancy and probability of repeat pregnancy in this model. The probability of a repeat pregnancy declined with increasing age at first pregnancy (p<0.001), and parous women were less likely to have conceived again. Compared with women born in the UK or Ireland, those from the rest of Europe, Eastern Africa, Southern Africa and Africa (unspecified) were less likely to have a repeat pregnancy, while women from Middle Africa and Western Africa were more likely to.

Table 2.

Univariable and multivariable analyses of demographic characteristics associated with having a repeat pregnancy, 2000-2009

| Characteristic | N(%)* | Univariable analysis | Multivariable analysis (n=7525) |

||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||||

| HR (95% CI) | p-value | aHR (95% CI) | p-value | ||

| Year of first reported pregnancy | |||||

| Change per year | - | 1.00 (0.98-1.02) | 0.929 | 1.02 (1.00-1.04) | 0.134 |

|

| |||||

| Age at first reported pregnancy | |||||

| <25 years | 1860 (35.2) | 1 | 1 | ||

| 25-29 years | 2829 (28.8) | 0.82 (0.74-0.90) | <0.001 | 0.86 (0.77-0.97) | 0.010 |

| 30-34 years | 2469 (23.1) | 0.68 (0.61-0.76) | <0.001 | 0.73 (0.64-0.83) | <0.001 |

| 35+ years | 1460 (13.4) | 0.40 (0.34-0.47) | <0.001 | 0.44 (0.37-0.53) | <0.001 |

|

| |||||

| Region of birth | |||||

| UK and Ireland | 1086 (29.0) | 1 | 1 | ||

| Europe | 261 (19.9) | 0.69 (0.51-0.92) | 0.012 | 0.73 (0.54-0.98) | 0.038 |

| Eastern Africa | 3773 (23.7) | 0.76 (0.67-0.86) | <0.001 | 0.83 (0.72-0.95) | 0.006 |

| Middle Africa | 613 (35.4) | 1.18 (0.99-1.40) | 0.058 | 1.29 (1.07-1.55) | 0.008 |

| Western Africa | 1412 (32.4) | 1.13 (0.98-1.31) | 0.089 | 1.16 (1.00-1.36) | 0.056 |

| Southern Africa | 737 (21.9) | 0.68 (0.56-0.82) | <0.001 | 0.62 (0.51-0.77) | <0.001 |

| Africa (unspecified) | 115 (8.7) | 0.24 (0.13-0.46) | <0.001 | 0.24 (0.11-0.51) | <0.001 |

| Elsewhere | 491 (26.3) | 0.80 (0.65-0.98) | 0.035 | 0.85 (0.69-1.06) | 0.147 |

|

| |||||

| Parity at first reported pregnancy | |||||

| Nulliparous | 3313 (30.0) | 1 | 1 | ||

| 1 | 2517 (23.7) | 0.75 (0.68-0.83) | <0.001 | 0.83 (0.75-0.93) | 0.001 |

| 2 | 1160 (21.0) | 0.65 (0.56-0.75) | <0.001 | 0.79 (0.68-0.91) | 0.002 |

| 3+ | 662 (17.4) | 0.50 (0.41-0.60) | <0.001 | 0.65 (0.53-0.80) | <0.001 |

HR – Hazard Ratio, aHR – Adjusted Hazard Ratio

N is the total of number women, and the proportion of those women who had repeat pregnancies is shown in brackets

Using Cox proportional hazards modeling there was no univariable association between repeat pregnancies and either CD4 count (<350 cells/μl vs. ≥350 cells/μl hazard ratio (HR):1.02, 95% CI:0.93-1.11, p=0.72), or the presence of HIV/AIDS symptoms (HR in women with symptoms compared with those without: 0.94, 95%CI:0.73-1.22, p=0.66).

Discussion

A substantial and increasing proportion of pregnancies in diagnosed HIV-infected women are occurring in those who have already received HIV-related care in one or more previous pregnancies. The main demographic characteristics independently associated with repeat pregnancies were younger age at first reported pregnancy, being nulliparous (or, if parous, having had fewer previous births), and being born in Middle or Western Africa (compared with the UK and Ireland). Maternal health at first pregnancy was not associated with repeat pregnancy.

The NSHPC is a large, well established, surveillance system which has been running for over 20 years, and reporting of pregnancies in women with diagnosed HIV is comprehensive.5 Due to the routine offer and high uptake of antenatal HIV testing since 2000, the number of pregnant women with undiagnosed HIV by the time of delivery is low.14 Since the NSHPC has national coverage it provided reliable denominators for estimating the rate of repeat pregnancies in this study, and allowed the investigation of factors associated with repeat pregnancies on a much larger scale than previous studies in other countries. To our knowledge, this is the first European study to estimate the rate of repeat pregnancies among diagnosed HIV-infected women.

There are, however, several reasons why information on the full reproductive history of women following their HIV diagnosis may be incomplete, thus leading to an under-estimation of both the number and proportion of repeat pregnancies. The majority of HIV-infected pregnant women in the UK and Ireland originate from abroad. Many of these women may already be part way through their childbearing on arrival in the UK or Ireland, and others may return to their country of origin or elsewhere at some stage thus any further pregnancies in these women will not be captured. Meanwhile, the probable under-ascertainment of early terminations and miscarriages in diagnosed women may lead to an under-estimation of the number and rate of pregnancies, and over-estimation of pregnancy spacing intervals. Information on contraceptive use is not collected by the NSHPC; studies elsewhere in Europe indicate that around half of pregnancies in HIV-infected women are unplanned,15,16 suggesting a potential unmet need for contraception.

A wide range of biological, social and cultural factors influence reproductive decision-making and fertility among women. These include existing family size, cultural factors, age, childbearing desires, partner’s views and family expectations. Among HIV-infected women additional factors also come into play including health status, issues of disclosure, concerns regarding their future health, the perceived risk of MTCT, and the attitudes of and information provided by health care providers.8,15,17-24 The increase in repeat pregnancies over the last two decades is likely to reflect a combination of factors including the accumulation of diagnosed HIV-infected women who have already had a pregnancy and are therefore ‘at risk’ of further pregnancies. Major improvements in quality of life and AIDS-free survival of people living with HIV,4 and substantial reductions in the risk of MTCT25,26 are also likely to have had an impact. Indeed, during the early years of the HIV epidemic, and before the introduction of effective interventions for the prevention of MTCT, a decline in pregnancy rates and increase in terminations among HIV-infected women was documented but since HAART became available pregnancy rates have increased, and terminations decreased.5,8,27,28 When considering the variation in likelihood of future pregnancies by calendar period, the substantial changes in the demographics of the population of HIV-infected women in the UK and Ireland since the early years of the epidemic should also in borne in mind.5 The probability of repeat pregnancy among women whose first pregnancy occurred towards the end of the study period may be an underestimate due to lack of time for a subsequent pregnancy, as well as delays in the reporting of pregnancies.

That younger age at first pregnancy was associated with an increased probability of further pregnancies is both logical and consistent with other studies.6-8 The association between nulliparity at first reported pregnancy and repeat pregnancies was also observed in the US,7 but not in Europe.6 Among women who had already had a baby at the time of their first reported pregnancy, the probability of repeat pregnancy was inversely associated with the number of previous births. The lower probability of repeat pregnancies among women born elsewhere in Europe compared with those born in the UK or Ireland may reflect the current low fertility rates in some European countries.29 European women may also be more likely than those born in Africa, for example, to return home during their reproductive life. There were marked variations in the probability of repeat pregnancy among women from different regions of sub-Saharan Africa even after adjusting for maternal age, parity and year of first pregnancy; the probability was higher among those from Middle and Western Africa, though the latter was borderline significant, and lower among those from Eastern and Southern Africa. This pattern is likely to reflect a complex range of cultural, behavioural and migratory factors such as fertility patterns in women’s countries of origin and the demographics of women who migrate from different regions.

Women with repeat pregnancies were less likely to have been diagnosed prior to their first pregnancy (during 2000-2009), which may reflect the fact that these women were more likely to have their first pregnancy earlier in the study period when HIV testing was less widespread.30 We found no association between maternal health status at first pregnancy and the probability of repeat pregnancy. Although women with repeat pregnancies were less likely to have conceived their first pregnancy whilst on ART this may reflect issues such as access to treatment rather than the actual health status of the women. Data from the US has shown that healthier women were more likely to have repeat pregnancies, 7,9 but in the previous European study there was no association.6

In conclusion, the number of diagnosed HIV-infected women in the UK and Ireland having more than one pregnancy has increased substantially and is likely to continue to grow. It is thus important that the epidemiology of these repeat pregnancies is thoroughly understood. Variations in the probability of repeat pregnancies, according to demographic characteristics, are an important consideration when planning reproductive health services and HIV care for people living with HIV.

Acknowledgements

National surveillance of obstetric and paediatric HIV is undertaken through the NSHPC in collaboration with the Health Protection Agency Centre for Infections and Health Protection Scotland. We gratefully acknowledge the contribution of the midwives, obstetricians, genitourinary physicians, paediatricians, clinical nurse specialists and all other colleagues who report to the NSHPC through the British Paediatric Surveillance Unit of the Royal College of Paediatrics and Child Health, and the obstetric reporting scheme run under the auspices of the Royal College of Obstetricians and Gynaecologists.

We thank Janet Masters (Study Co-ordinator), Icina Shakes (Study Assistant), and Hiwot Haile-Selassie (Research Assistant) for their essential contributions to the NSHPC.

Funding: The National Study of HIV in Pregnancy and Childhood (NSHPC) receives core funding from the Health Protection Agency (grant number GHP/003/ 013/003). This work was undertaken at the Centre for Paediatric Epidemiology and Biostatistics which benefits from funding support from the MRC in its capacity as the MRC Centre of Epidemiology for Child Health (grant number G0400546). The University College London Institute of Child Health receives a proportion of funding from the Department of Health’s National Institute for Health Research Biomedical Research Centres funding scheme. Clare French is funded by a Medical Research Council PhD studentship. Claire Thorne is funded by a Wellcome Trust Career Development Research Fellowship.

Footnotes

Ethics The NSHPC has London Multi-Centre Research Ethics Committee approval (MREC/04/2/009).

Conflicts of Interest: We declare that we have no conflicts of interest.

Parts of the (preliminary) analyses were presented previously at the XVIII International AIDS Conference, July 2010 (abstract 9258).

This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Joint United Nations Programme on HIV/AIDS (UNAIDS) World Health Organization (WHO) 2009 AIDS Epidemic Update. 2009 Available at: http://www.unaids.org/en/media/unaids/contentassets/dataimport/pub/report/2009/jc1700_epi_update_2009_en.pdf.

- 2.de Ruiter A, Mercey D, Anderson J, et al. British HIV Association and Children’s HIV Association guidelines for the management of HIV infection in pregnant women 2008. HIV Med. 2008 Aug;9(7):452–502. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-1293.2008.00619.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Sturt AS, Dokubo EK, Sint TT. Antiretroviral therapy (ART) for treating HIV infection in ART-eligible pregnant women. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2010;3:CD008440. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD008440. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Gange SJ, Barron Y, Greenblatt RM, et al. Effectiveness of highly active antiretroviral therapy among HIV-1 infected women. J Epidemiol Community Health. 2002 Feb;56(2):153–159. doi: 10.1136/jech.56.2.153. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Townsend CL, Cortina-Borja M, Peckham CS, Tookey PA. Trends in management and outcome of pregnancies in HIV-infected women in the UK and Ireland, 1990-2006. BJOG. 2008;115(9):1078–1086. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-0528.2008.01706.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Agangi A, Thorne C, Newell ML. Increasing likelihood of further live births in HIV-infected women in recent years. BJOG. 2005 Jul;112(7):881–888. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-0528.2005.00569.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bryant AS, Leighty RM, Shen X, et al. Predictors of repeat pregnancy among HIV-1-infected women. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2007 Jan 1;44(1):87–92. doi: 10.1097/01.qai.0000243116.14165.52. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Blair JM, Hanson DL, Jones JL, Dworkin MS. Trends in pregnancy rates among women with human immunodeficiency virus. Obstet Gynecol. 2004 Apr;103(4):663–668. doi: 10.1097/01.AOG.0000117083.33239.b5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Minkoff H, Hershow R, Watts DH, et al. The relationship of pregnancy to human immunodeficiency virus disease progression. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2003;189(2):552–559. doi: 10.1067/s0002-9378(03)00467-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.United Nations Composition of macro geographical (continental) regions, geographical sub-regions, and selected economic and other groupings. 2010 Available at: http://unstats.un.org/unsd/methods/m49/m49regin.htm.

- 11.Therneau TM, Grambsch PM. Modeling Survival Data. In: Dietz K, Gail M, Krickeberg K, Tsiatis A, Samet J, editors. Statistics for Biology and Health. Springer; New York: 2000. pp. 127–148. [Google Scholar]

- 12.World Health Organisation Report of a WHO Technical Consultation on Birth Spacing. 2005 Available at: http://www.who.int/making_pregnancy_safer/documents/birth_spacing.pdf.

- 13.National Institute for Clinical Excellence Antenatal Care—Routine Care for the Healthy Pregnant Woman. Clinical guideline 6. 2003 Available at: http://www.nice.org.uk/nicemedia/pdf/CG062NICEguideline.pdf.

- 14.Townsend CL, Cliffe S, Tookey PA. Uptake of antenatal HIV testing in the United Kingdom: 2000-2003. J Public Health (Oxf) 2006 Sep;28(3):248–252. doi: 10.1093/pubmed/fdl026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Fiore S, Heard I, Thorne C, et al. Reproductive experience of HIV-infected women living in Europe. Hum Reprod. 2008 Sep;23(9):2140–2144. doi: 10.1093/humrep/den232. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Floridia M, Ravizza M, Tamburrini E, et al. Diagnosis of HIV infection in pregnancy: data from a national cohort of pregnant women with HIV in Italy. Epidemiol Infect. 2006 Oct;134(5):1120–1127. doi: 10.1017/S0950268806006066. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Bedimo AL, Bessinger R, Kissinger P. Reproductive choices among HIV-positive women. Soc Sci Med. 1998 Jan;46(2):171–179. doi: 10.1016/s0277-9536(97)00157-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Craft SM, Delaney RO, Bautista DT, Serovich JM. Pregnancy decisions among women with HIV. AIDS Behav. 2007 Nov;11(6):927–935. doi: 10.1007/s10461-007-9219-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Finocchario-Kessler S, Sweat MD, Dariotis JK, et al. Understanding High Fertility Desires and Intentions Among a Sample of Urban Women Living with HIV in the United States. AIDS Behav. 2010 Oct;14(5):1106–1114. doi: 10.1007/s10461-009-9637-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Heard I, Sitta R, Lert F. Reproductive choice in men and women living with HIV: evidence from a large representative sample of outpatients attending French hospitals (ANRS-EN12-VESPA Study) AIDS. 2007 Jan;21(Suppl 1):S77–82. doi: 10.1097/01.aids.0000255089.44297.6f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kirshenbaum SB, Hirky AE, Correale J, et al. “Throwing the dice”: pregnancy decision-making among HIV-positive women in four U.S. cities. Perspect Sex Reprod Health. 2004 May-Jun;36(3):106–113. doi: 10.1363/psrh.36.106.04. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Loutfy MR, Hart TA, Mohammed SS, et al. Fertility desires and intentions of HIV-positive women of reproductive age in Ontario, Canada: a cross-sectional study. PLoS One. 2009;4(12):e7925. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0007925. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ogilvie GS, Palepu A, Remple VP, et al. Fertility intentions of women of reproductive age living with HIV in British Columbia, Canada. AIDS. 2007 Jan;21:S83–S88. doi: 10.1097/01.aids.0000255090.51921.60. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Wilcher R, Cates W. Reproductive choices for women with HIV. Bull World Health Organ. 2009 Nov;87(11):833–839. doi: 10.2471/BLT.08.059360. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Duong T, Ades AE, Gibb DM, Tookey PA, Masters J. Vertical transmission rates for HIV in the British Isles: estimates based on surveillance data. BMJ. 1999 Nov 6;319(7219):1227–1229. doi: 10.1136/bmj.319.7219.1227. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Townsend CL, Cortina-Borja M, Peckham CS, de Ruiter A, Lyall H, Tookey PA. Low rates of mother-to-child transmission of HIV following effective pregnancy interventions in the United Kingdom and Ireland, 2000-2006. AIDS. 2008 May 11;22(8):973–981. doi: 10.1097/QAD.0b013e3282f9b67a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Stephenson JM, Griffioen A. The effect of HIV diagnosis on reproductive experience. Study Group for the Medical Research Council Collaborative Study of Women with HIV. AIDS. 1996 Dec;10(14):1683–1687. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.van Benthem BH, de Vincenzi I, Delmas MC, Larsen C, van den Hoek A, Prins M. Pregnancies before and after HIV diagnosis in a european cohort of HIV-infected women. European Study on the Natural History of HIV Infection in Women. AIDS. 2000 Sep 29;14(14):2171–2178. doi: 10.1097/00002030-200009290-00014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Billari FC, Kohler HP. Patterns of low and lowest-low fertility in Europe. Popul Stud (Camb) 2004;58(2):161–176. doi: 10.1080/0032472042000213695. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.British HIV Association UK National Guidelines for HIV Testing. 2008 Available at: http://www.bhiva.org/documents/Guidelines/Testing/GlinesHIVTest08.pdf.