Abstract

Background

Carnitine acetyltransferase (CAT) catalyses the reversible conversion of acetyl-CoA into acetylcarnitine. The aim of this study was to use the metabolic tracer hyperpolarised [2-13C]pyruvate with magnetic resonance spectroscopy (MRS) to determine if CAT facilitates carbohydrate oxidation in the heart.

Methods and Results

Ex vivo, following hyperpolarised [2-13C]pyruvate infusion, the [1-13C]acetylcarnitine MR resonance was saturated with a radiofrequency pulse and the effect of this saturation on [1-13C]citrate and [5-13C]glutamate was observed. In vivo, [2-13C]pyruvate was infused into three groups of fed male Wistar rats; (a) controls, (b) rats in which dichloroacetate enhanced PDH flux and (c) rats in which dobutamine elevated cardiac workload. In the perfused heart, [1-13C]acetylcarnitine saturation reduced the [1-13C]citrate and [5-13C]glutamate resonances by 63% and 51%, indicating rapid exchange between pyruvate-derived acetyl-CoA and the acetylcarnitine pool. In vivo, dichloroacetate increased the rate of [1-13C]acetylcarnitine production by 35% and increased the overall acetylcarnitine pool size by 33%. Dobutamine decreased the rate of [1-13C]acetylcarnitine production by 37% and decreased the acetylcarnitine pool size by 40%.

Conclusions

Hyperpolarised 13C MRS has revealed that acetylcarnitine provides a route of disposal for excess acetyl-CoA, and also a means to replenish acetyl-CoA when cardiac workload is increased. Cycling of acetyl-CoA through acetylcarnitine appears key to matching instantaneous acetyl-CoA supply with metabolic demand, thereby helping to balance myocardial substrate supply and contractile function.

Keywords: metabolic imaging, metabolism, acetylcarnitine, hyperpolarised 13C MRS

The enzyme complex pyruvate dehydrogenase (PDH) is the key enzyme involved in balancing cardiac glucose and fatty acid oxidation, catalysing the irreversible oxidation of pyruvate to form acetyl-CoA, NADH and CO2. Several PDH-mediated mechanisms exist to promote fatty acid oxidation over glucose oxidation, including phosphorylation-inhibition of PDH1 and end-product inhibition of PDH by high acetyl-CoA/CoA and NADH/NAD+ ratios2. After eating and in response to energetic stressors such as aerobic exercise or ischemia, glucose and other carbohydrates become important cardiac fuels3, 4. Additionally, mobilisation of the heart’s limited buffer stores (phosphocreatine, triacylglyceride and glycogen) help maintain ATP production for short periods of increased energetic demand or reduced substrate supply5-9.

Recently, we used hyperpolarised [2-13C]pyruvate as a metabolic tracer in the isolated perfused rat heart to observe the relationship between PDH flux and Krebs cycle metabolism in real time, using 13C magnetic resonance spectroscopy (MRS)10-12. We observed conversion of [2-13C]pyruvate into the metabolites citrate and glutamate, with a substantial fraction of pyruvate oxidised by PDH being converted to acetylcarnitine10. Acetylcarnitine is produced by carnitine acetyltransferase (CAT), an enzyme found in cardiac mitochondria13, which is stimulated by acetyl-CoA and carnitine14. Myocardial acetylcarnitine levels vary widely with species and metabolic state: in rat, acetylcarnitine levels were >20-fold higher than that of acetyl-CoA, ranging from ~180 nmoles/g of frozen heart tissue in fat-fed rats to ~380 nmoles/g of frozen heart tissue in normal and carbohydrate-fed rats15, whereas in pigs acetylcarnitine levels were between 4- and 10-fold greater than acetyl-CoA levels, ranging from 320 nmol/gdw upon inhibition of fatty acid oxidation to ~800 nmol/gdw in control pigs16. The equilibrium for the acetyl transfer reaction is maintained despite different steady-state concentrations of each reactant, as shown in equation 115, 17:

| [1] |

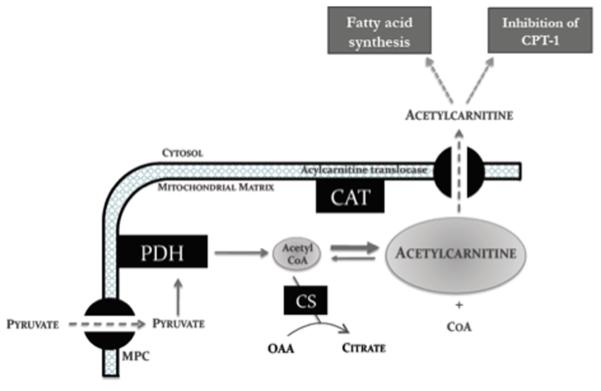

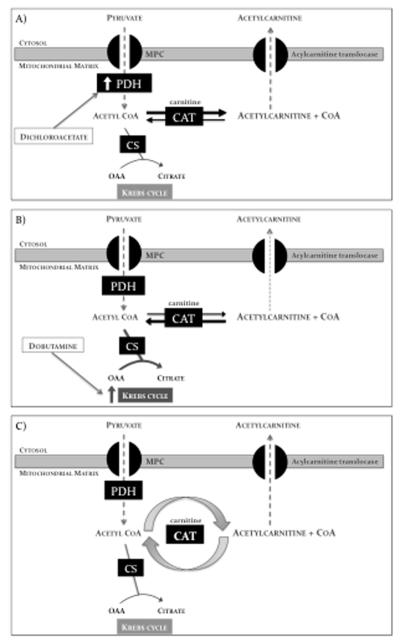

Studies performed in isolated mitochondria and in rat heart tissue have suggested three physiological roles for CAT (Figure 1). Firstly, formation of acetylcarnitine from acetyl-CoA has reduced the mitochondrial acetyl-CoA/CoA ratio15, 18, preventing end-product inhibition of PDH2 and, importantly, liberating acetylated CoA for other mitochondrial functions18. Secondly, acetylcarnitine formation enables transport of acetyl-CoA produced in the mitochondria into the cytosol17, 19, for potential use as a source of malonyl-CoA for fatty acid synthesis17 or inhibition of fatty acid oxidation via carnitine palmitoyl transferase (CPT120). Thirdly, acetylcarnitine itself may serve as an acetyl-CoA buffer within cardiomyocytes15, 16.

Figure 1.

The involvement of acetylcarnitine in cardiac carbohydrate metabolism. Acetyl-CoA formed from pyruvate can be incorporated into the Krebs cycle via citrate synthase or can be incorporated into the larger acetylcarnitine ‘overflow pool’ via CAT. CAT liberates free CoA and allows for cytosolic disposal of acetyl moieties in excess of demand.

Abbreviations: PDH, pyruvate dehydrogenase; MPC, mitochondrial pyruvate carrier; CAT, carnitine acetyltransferase; CPT, carnitine palmitoyltransferase; CS, citrate synthase.

In heart failure patients21, 22 and in experimental pressure-overload cardiac hypertrophy23, 24, carnitine deficiency has been implicated as a cause of disease whereas carnitine supplementation has improved cardiac function. Our observation of significant levels of [1-13C]acetylcarnitine production from [2-13C]pyruvate in the intact heart was consistent with the in vitro observation that acetylcarnitine is produced readily from pyruvate-derived acetyl-CoA25. When taken together, ex vivo hyperpolarised 13C MRS and in vitro results suggest that CAT and the acetylcarnitine pool may play an essential role in regulating cardiac energy metabolism. However, the dynamic interaction of the acetylcarnitine pool with acetyl-CoA has not been investigated, nor the real-time response of the acetylcarnitine pool to in vivo changes in cardiac substrate supply and energy demand. The aim of this study was to use hyperpolarised [2-13C]pyruvate with high temporal resolution MRS to investigate the hypothesis that acetyl-CoA produced via pyruvate dehydrogenase (PDH) must cycle through CAT into the acetylcarnitine pool prior to incorporation into the Krebs cycle. To achieve this aim, we used a novel approach of saturation transfer hyperpolarised MRS to crush the [1-13C]acetylcarnitine resonance, thus determining how much [1-13C]acetylcarnitine dynamically generated from [2-13C]pyruvate was immediately incorporated back into the acetyl-CoA pool, and subsequently into the Krebs cycle. Further, if our hypothesis proved true, our second aim was to characterise [2-13C]pyruvate metabolism in vivo with hyperpolarised MRS, and if possible, to use this technique to monitor the acetylcarnitine pool in response to increases in pyruvate oxidation and cardiac workload. Our results indicate that acetylcarnitine acts to ‘fine-tune’ acetyl-CoA availability in the heart, and further, that use of hyperpolarised [2-13C]pyruvate with MRS may enable non-invasive clinical diagnosis of cardiomyopathies involving carnitine deficiency26.

Methods

[2-13C]Pyruvate preparation

[2-13C]pyruvic acid (40 mg; Sigma, Gillingham UK), mixed with 15 mM trityl radical (OXO63, GE-Healthcare, Amersham UK) and a trace amount of Dotarem (Guerbet, Birmingham UK), was polarised and dissolved as previously described10,11. Further details are presented in the online only supplemental methods section.

Saturation transfer experiments

We chose to perform our saturation transfer MRS studies in the isolated perfused heart instead of in vivo, to ensure maximum signal to noise ratio (SNR) from all metabolites derived from [2-13C]pyruvate and to minimise Bo inhomogeneity for improved spectral saturation. Five male Wistar rat hearts (heart weight ~1 g) were perfused in the Langendorff mode, as in a published protocol10. The Krebs-Henseleit bicarbonate perfusion buffer used contained 11 mM glucose and 2.5 mM pyruvate, and was aerated with a mixture of 95% oxygen (O2) and 5% carbon dioxide (CO2), to give a final pH of 7.4 at 37 °C. Three experiments were then performed in each perfused heart: 1) control, 2) acetylcarnitine saturation, and 3) control saturation (Figure 2), as follows:

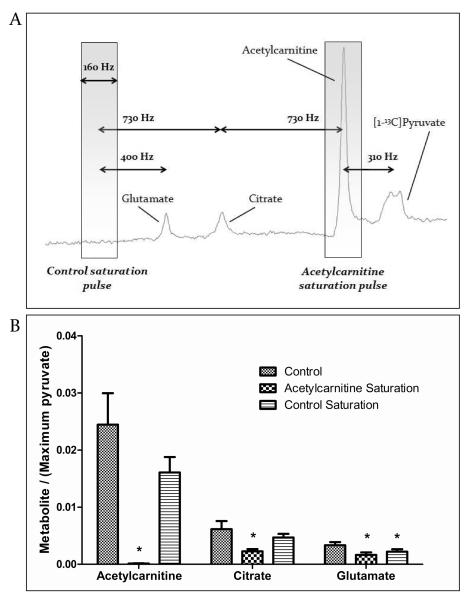

Figure 2.

Design and results of acetylcarnitine saturation experiments (n = 5). A) Control spectra were acquired to identify the exact frequency of the acetylcarnitine peak, as shown. Next, a saturation pulse (gray box: 160 Hz bandwidth) was applied continuously to the acetylcarnitine resonance, which was 730 Hz downstream of citrate. The same pulse was applied 730 Hz upstream of citrate as a control to ensure that citrate was not affected by RF saturation. B) Saturation crushed all acetylcarnitine 13C signal, and significantly reduced the citrate and glutamate peak areas. The control-saturation experiment confirmed that acetylcarnitine saturation had no effect on citrate. Glutamate, which was 330 Hz nearer to the control saturation pulse than citrate, was significantly reduced by RF effects. All data are ± SEM and statistical significance was taken at p<0.05. *p<0.05 compared with controls (in which no saturation was applied).

1) Hyperpolarised [2-13C]pyruvate was diluted to 2.5 mM, perfused into the heart, and 13C metabolites were detected, with 1 s temporal resolution over the course of 2 minutes (TR = 1 s, excitation flip angle = 30°, 120 acquisitions, 180 ppm sweep width; 4096 acquired points; frequency centred at 125 ppm). The precise frequency of the [1-13C]acetylcarnitine resonance was noted.

2) After a second dose of [2-13C]pyruvate was polarised (45 min), 2.5 mM [2-13C]pyruvate was again delivered to the heart and 13C spectra were acquired as before while RF saturation was continually applied throughout the experiment (described below) exactly to the [1-13C]acetylcarnitine resonance, determined in the previous experiment (~175 ppm).

3) A third dose of 2.5 mM [2-13C]pyruvate was delivered to the heart and a control saturation experiment was performed. 13C spectra were acquired while saturation was continuously applied off resonance at ~187 ppm. The location of this pulse replicated the frequency separation between the [1-13C]citrate and [1-13C]acetylcarnitine peaks, and ensured that the RF saturation pulse bandwidth was narrow enough to prevent direct saturation of the [1-13C]citrate resonance.

To achieve the continuous saturation at the appropriate resonance frequency, a cascade of eight SNEEZE pulses27 were repeatedly applied. Each SNEEZE pulse had a time-bandwidth product of 5.82 and 100 ms duration, with 100 μs interval between pulses. No saturation was applied during signal acquisition (180 μs). The effective full-width half-maximum bandwidth was ~160 Hz when tested on a sample of acetone. An experiment in which the acetyl-CoA resonance was also saturated was not performed, as the small [1-13C]acetyl-CoA resonance at ~202 ppm (Figure 328) could not be saturated without also affecting the input [2-13C]pyruvate signal (207.8 ppm10).

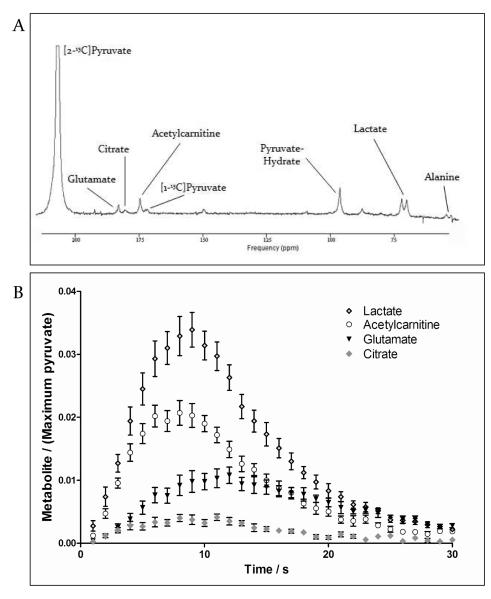

Figure 3.

Representative spectrum acquired from the heart in vivo, after hyperpolarised [2-13C]pyruvate was infused into a rat. A) For display purposes, 3 s of data were summed and a line broadening of 15 Hz was applied.

Modified from Schroeder MA, Clarke K, Neubauer S, Tyler DJ. Hyperpolarized magnetic resonance: a novel technique for the in vivo assessment of cardiovascular disease. Circulation. 2011; 124:1580-1594.26 B) Metabolic products of [2-13C]pyruvate acquired in control rat hearts (n = 8). Data are mean ± SEM.

Animal handing and in vivo MRS experiments

Investigations conformed to the Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals published by the US National Institutes of Health (NIH publication No. 85-23, revised 1996), the Home Office Guidance on the Operation of the Animals (Scientific Procedures) Act, 1986 (HMSO) and to institutional guidelines. Animals (weight ~300 g) were prepared as previously described29. DCA (n = 6, 2 mg/ml/min) was dissolved into 1.5 ml of PBS, and the solution was infused intravenously starting 15 minutes before [2-13C]pyruvate infusion. Dobutamine (n = 7, 0.1 mg/kg/min) was infused into rats intravenously starting 5 min before [2-13C]pyruvate infusion. In vivo cardiac hyperpolarised 13C MRS experiments were performed in a 7 T horizontal bore MR scanner as previously described30, with further details presented in the online only supplemental methods section.

A 1H/13C butterfly surface coil was placed over the rat chest to localise signals to the heart. It is possible that this approach may have allowed for MR signal contamination from neighbouring organs; however, due to the high rates of PDH and Krebs cycle flux in the heart compared with liver, resting skeletal muscle and blood, it is extremely likely that the MR signals measured from [1-13C]acetyl-carnitine, [1-13C]citrate and [5-13C]glutamate were predominantly from cardiac metabolism29.

MR data analysis

All cardiac 13C spectra were analysed using the AMARES algorithm in the jMRUI software package31. For acetylcarnitine saturation experiments, the first 50 spectra acquired following pyruvate arrival at the perfused heart were summed (50 s worth) to yield a single spectrum with peak heights for [1-13C]citrate, [5-13C]glutamate, [1-13C]acetylcarnitine and [2-13C]pyruvate that were well above the level of noise. These single spectra were then quantified in jMRUI and the resultant ratios of [1-13C]citrate/[2-13C]pyruvate, [5-13C]glutamate/[2-13C]pyruvate and [1-13C]acetyl-carnitine/[2-13C]pyruvate were used for subsequent analyses. Spectra were summed prior to analysis because acetylcarnitine saturation experiments had a low signal to noise ratio to the degree that accurate peak quantification of individual spectra was not feasible.

The peak areas of in vivo [2-13C]pyruvate, [1-13C]acetylcarnitine, [1-13C]citrate and [5-13C]glutamate at each time point were quantified and used as input data for a kinetic model developed for the analysis of hyperpolarised [2-13C]pyruvate MRS data32, 33, based on a model initially developed by Zierhut et al34. Firstly the change in [2-13C]pyruvate signal over the 60 s acquisition time was fit to the integrated [2-13C]pyruvate peak area data, using equation [2]:

| [2] |

In this equation, Mpyr(t) was the [2-13C]pyruvate peak area as a function of time. This equation fit the parameters kpyr, the rate constant for pyruvate signal decay (s−1), rateinj, the pyruvate arrival rate (a.u. s−1), tarrival, the pyruvate arrival time (s) and tend, the time correlating with the end of the injection (s). These parameters were used in equation [3], along with the dynamic [1-13C]acetylcarnitine, [1-13C]citrate and [5-13C]glutamate data, to calculate kpyr→X, the rate constant for exchange of pyruvate to each of its metabolites (s−1) and kX, the rate constant for signal decay of each metabolite (s−1) which was assumed to consist of metabolite T1 decay and signal loss from the 7.5° RF flip angle pulses. In equation [5], t’ = t − tdelay, where tdelay was the delay between pyruvate arrival and metabolite appearance.

| [3] |

This model was implemented in order to facilitate comparisons among experimental conditions within each metabolite pool. The calculated rate constants kpyr→X reflect the rate of 13C accumulation in each metabolite pool, not necessarily the overall amount of production of each metabolite.

In vitro measurement of acetylcarnitine pool size

A spectrophotometric assay was performed on heart tissue extracts to quantify acetylcarnitine levels in four separate groups of rats, by the methods of Marquis and Fritz35 and Grizard et al36. In one of these groups, acetylcarnitine levels were measured in normal heart tissue, without pyruvate infusion (n = 4). The other three groups were prepared identically to the groups of rats studied in vivo with hyperpolarised [2-13C]pyruvate: one group received 0.25 mmol/kg of aqueous pyruvate alone (n = 7), a second group received DCA at 2 mg/ml/min for 15 min prior to 0.25 mmol/kg pyruvate infusion (n = 4), and a third group received dobutamine at 0.1 mg/kg/min for 5 min prior to 0.25 mmol/kg pyruvate infusion (n = 4). After each intervention, the heart from each rat was rapidly removed from the body cavity, at a time point chosen to correspond with the time of maximum [1-13C]acetylcarnitine MR signal during in vivo data acquisition. Details of the protocols used for tissue dissection and for the acetylcarnitine assay are described in the online only supplemental methods section.

Statistical methods

Values are mean ± SEM and all analyses were performed in GraphPad Prism (GraphPad, La Jolla, California). Statistical significance was considered at p < 0.05.

For ex vivo MRS experiments in which three experiments were performed sequentially in the same heart, one-way repeated measures ANOVA with a Tukey’s multiple comparison test was used to identify statistical differences among groups. For in vivo MRS experiments and in vitro measurements of acetylcarnitine levels, in which each experimental group was comprised of independent subjects, one-way ANOVA was used to identify statistical differences. For the groups in which a significant difference was detected, t-tests were performed with a Holm-Sidak correction for multiple comparisons.

Results

Acetylcarnitine saturation experiments

In spectra acquired from the isolated perfused rat heart, the acetylcarnitine resonance was selectively saturated to crush the MR signal in all nuclei incorporated into the acetylcarnitine pool. The effect of acetylcarnitine saturation on the citrate resonance area qualitatively distinguished the fractions of [2-13C]pyruvate-derived acetyl-CoA that were 1) converted immediately into citrate, 2) converted into acetylcarnitine and stored, and 3) converted into acetylcarnitine prior to rapid re-conversion to acetyl-CoA and incorporation into the Krebs cycle (Figure 2).

The acetylcarnitine saturation pulse reduced the acetylcarnitine peak area by 99.5±0.2% compared with control experiments in which no saturation was applied. Further, the control saturation experiments confirmed that the saturation pulse had a sufficiently low bandwidth to avoid RF effects on the citrate peak. The control saturation pulse did, however, affect the glutamate peak, which was 300 Hz closer to the control saturation pulse than was citrate (Figure 2).

Selective saturation of the acetylcarnitine resonance reduced the magnitude of the citrate resonance by 63% (Figure 2), compared with control experiments in which no saturation was applied. When compared with the control experiments in which saturation was applied off-resonance, acetylcarnitine saturation reduced the magnitude of the citrate resonance by 51%. This indicated that, of all the [2-13C]pyruvate-derived acetyl-CoA that was incorporated into the Krebs cycle over 50 s, approximately half was initially converted into acetylcarnitine, prior to release from the acetylcarnitine pool as acetyl-CoA and incorporation into the Krebs cycle. The remaining [1-13C]citrate, unaffected by saturation, was produced from [2-13C]pyruvate-derived acetyl-CoA that immediately condensed with citrate synthase. This effect was also observed as a 51% reduction in the magnitude of the glutamate resonance, compared with control experiments in which no saturation was applied.

In vivo metabolism of hyperpolarised [2-13C]pyruvate

Peaks relating to the infused [2-13C]pyruvate, as well as the metabolic products [1-13C]acetylcarnitine (175 ppm), [1-13C]citrate (181 ppm), [5-13C]glutamate (183 ppm), [2-13C]lactate (71 ppm), and [2-13C]alanine (53 ppm), were clearly observed in vivo. A broad, low signal-to-noise resonance corresponding with [1-13C]acetyl-CoA was detectable ~202 ppm, as previously described28. A representative spectrum is shown in Figure 3, with an example of the time course of the primary metabolic products.

The effects of increased PDH activity, caused by dichloroacetate (DCA) infusion, or increased cardiac workload, caused by dobutamine infusion, on [1-13C]citrate, [5-13C]glutamate and [1-13C]acetylcarnitine production are shown in Figure 4. In control rat hearts, the rate constant for the conversion of [2-13C]pyruvate to [1-13C]citrate (kpyr→cit) obtained from the in vivo data, was 0.0012±0.0002 s−1. This value did not change with either metabolic intervention. The mean kpyr→glu in control rats was 0.0025±0.0003 s−1, and this also did not change in response to dichloroacetate or dobutamine infusions.

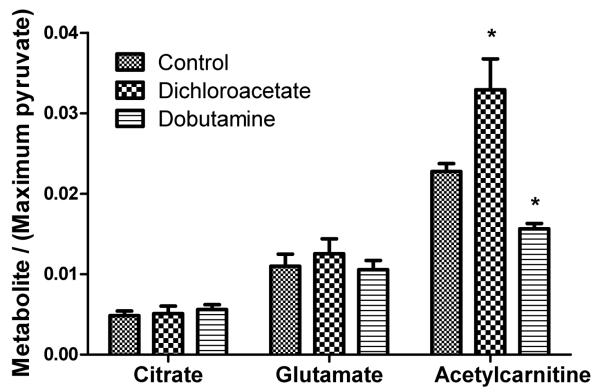

Figure 4.

The in vivo effects of infusing DCA (n = 6) and dobutamine (n = 8) on the production of [1-13C]citrate, [5-13C]glutamate, and [1-13C]acetylcarnitine following infusion of [2-13C]pyruvate. Data are ± SEM and statistical significance was taken at p<0.05.

In control rats, the rate constant for the production of [1-13C]acetylcarnitine (kpyr→AC) was 0.0075±0.0007 s−1, approximately 3-fold higher than that of [5-13C]glutamate production and 6-fold higher than the rate constant of [1-13C]citrate production. DCA infusion caused a significant, 35% increase in the rate of 13C label incorporation into the acetylcarnitine pool (kpyr→AC = 0.010±0.001 s−1, p=0.043). Dobutamine infusion caused a 37% decrease in the rate of 13C label incorporation into the acetylcarnitine pool (kpyr→AC = 0.0047±0.0007 s−1, p=0.014).

Spectra, acquired with 0.5 s temporal resolution, revealed that the 13C label appeared (defined as the time tdelay) in the [5-13C]glutamate pool 3.1±0.4 s after the arrival of [2-13C]pyruvate and 1.6 s after the 13C label appeared in the [1-13C]citrate pool. There were no differences between the time of appearance of [1-13C]citrate at 1.5±0.5 s and [1-13C]acetylcarnitine at 2.0±0.3 s.

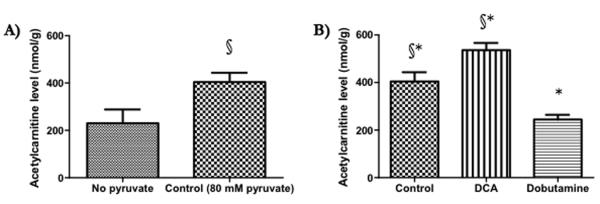

Acetylcarnitine in cardiac extracts

Infusion of 0.25 mmol/kg pyruvate, using the same protocol as was used for in vivo hyperpolarised 13C MRS experiments, increased myocardial acetylcarnitine levels by 76% compared with tissue that received no pyruvate (from 230±60 to 400±40 nmol/g wet weight tissue, Figure 5A). In rats that had received 0.25 mmol/kg pyruvate and were thus identical to the rats studied in vivo with hyperpolarised 13C MRS (Figure 5B), DCA infusion caused a significant, 33% increase in the size of the myocardial acetylcarnitine pool (540±30 nmol acetylcarnitine/gww). Dobutamine infusion caused a 40% decrease in the size of the myocardial acetylcarnitine pool (240±20 nmol acetylcarnitine/gww).

Figure 5.

A) The effect of infusing 0.25 mmol/kg pyruvate into a living rat (n = 4 vs. n = 7), as per our in vivo hyperpolarised 13C MRS experiments, on myocardial acetylcarnitine levels. B) The effects of DCA (n = 4) and dobutamine (n = 4) on myocardial acetylcarnitine levels. All data are ± SEM and statistical significance was taken at p<0.05. §p<0.05 compared with tissue not exposed to pyruvate, *p<0.05 compared with controls (that were exposed to 80 μmol pyruvate).

Discussion

The maintenance of near-equilibrium in the CAT reaction, such that myocardial acetylcarnitine content remains approximately one order of magnitude greater than myocardial acetyl-CoA content, suggests both high enzyme activity and a role for acetylcarnitine as an acetyl-CoA buffer. Therefore, in this study, we hypothesized that CAT was dynamically involved in pyruvate oxidation by means of rapid cycling of acetyl-CoA generated from pyruvate through the acetylcarnitine pool. Use of saturation transfer 13C MRS with hyperpolarised [2-13C]pyruvate uniquely provided the temporal resolution necessary to test our hypothesis in the ex vivo heart10.

Saturating the MR signal of the [1-13C]acetylcarnitine resonance reduced the magnitudes of the Krebs cycle-derived [1-13C]citrate and [5-13C]glutamate resonances by 63% and 51%, respectively, over a 50 s period in the isolated perfused heart. Therefore, in the healthy heart, approximately half of the PDH-derived acetyl-CoA that contributes to ATP production cycles through CAT into the acetylcarnitine pool, prior to re-conversion to acetyl-CoA and incorporation into the Krebs cycle. Constant acetylcarnitine/acetyl-CoA turnover may allow the cardiomyocyte to respond to multiple stimuli that may affect mitochondrial acetyl-CoA content, analogous to rapid turnover of other energetic buffer pools. For example, cardiac triacylglyceride turnover maintains homeostasis of free fatty acids in the cytosol6, 37 and the rapid conversion of phosphocreatine to ATP prevents altered cardiac ATP content9.

The second aim of this study was to determine if hyperpolarised [2-13C]pyruvate metabolism could be followed in vivo with MRS, and if so, to use the technique to monitor the acetylcarnitine pool in response to altered substrate supply and energy demand. Using a protocol similar to that applied previously in living rats to follow hyperpolarised [1-13C]pyruvate metabolism29, we detected the conversions of [2-13C]pyruvate into [1-13C]citrate, [5-13C]glutamate, and [1-13C]acetyl-carnitine with 0.5 s temporal resolution. A delay between the appearance of 13C in the citrate and glutamate pools of ~1.5 s was measured, marking the first in vivo assessment of instantaneous rates of flux though the first span of the Krebs cycle and the oxoglutarate-malate carrier (OMC). The result indicates the potential utility of our hyperpolarised 13C MRS protocol to contribute to real time metabolic models.

A limitation of the applied protocol was that the infused pyruvate dose raised plasma pyruvate levels to approximately 250 μM, 25% higher than physiological levels, 30 s after infusion33. This increased PDH flux, manifested as a 76% increase in cardiac acetylcarnitine content to 400 nmol/gww (a value still within the physiological range). However, the elevation in plasma pyruvate was minor compared with the physiological disturbances typical of ex vivo or in vitro preparations. Further, physiological acetylcarnitine levels vary widely under normal physiological conditions15, 16, and in vivo DCA and dobutamine experiments confirmed that the acetylcarnitine pool remained sensitive to metabolic perturbation.

Infusion of DCA, an acetate analogue that stimulates PDH activity without affecting cardiac workload38, caused a 35% increase in the production of [1-13C]acetylcarnitine from [2-13C]pyruvate, alongside a 33% increase in the myocardial acetylcarnitine pool size measured in frozen tissue. However, despite the increase in PDH flux and resultant increase in 13C incorporated into the acetyl-CoA pool33, the rate of 13C label incorporation into [1-13C]citrate and [5-13C]glutamate was unchanged. Taken together, these observations suggest that in vivo, if acetyl-CoA is formed from PDH in excess of the energetic demand, then mitochondrial CAT continually recovers free CoA whilst allowing for the disposal of the excess acetyl moieties to maintain a low acetyl-CoA/CoA ratio (Figure 6A). This is the first study demonstrating CAT-mediated acetyl-CoA disposal in real time, and in vivo.

Figure 6.

A) In the presence of dichloroacetate (DCA), PDH flux is increased, in turn increasing mitochondrial acetyl-CoA levels. Under these conditions excess acetyl-CoA is converted into acetylcarnitine by CAT, to liberate CoA. B) In the presence of dobutamine, cardiac workload and thus Krebs cycle demand are increased. Under these conditions, mitochondrial acetylcarnitine acts as an extra source of energetic substrate. C) This study has revealed that acetyl-CoA rapidly cycles through the acetylcarnitine pool. It is likely that acetyl-CoA/acetylcarnitine cycling enables myocytes to ‘fine-tune’ the supply of mitochondrial acetyl-CoA, to ensure constant provision of energetic substrate without potentially inhibitory acetyl-CoA accumulation.

Abbreviations: PDH, pyruvate dehydrogenase; MPC, mitochondrial pyruvate carrier; CAT, carnitine acetyltransferase; CS, citrate synthase; OAA, oxaloacetate.

Dobutamine, a selective β-agonist known to increase flux through PDH and flux through the Krebs cycle39, 40, was used to acutely increase myocardial workload in rats in vivo. Five minutes after in vivo dobutamine infusion, we observed a 37% decrease in the production of [1-13C]acetylcarnitine from [2-13C]pyruvate, alongside a 40% decrease in the size of the myocardial acetylcarnitine pool itself. The decreased rate of [1-13C]acetylcarnitine production and acetylcarnitine pool size, particularly in the context of increased PDH flux39, strongly indicated that acetylcarnitine itself was consumed in vivo to buffer myocardial acetyl-CoA levels, in response to increased ATP demand (Figure 6B).

A second limitation to this study was that acetyl-CoA and free CoA levels were not measured alongside acetylcarnitine levels, due to the technical difficulties in accurately assessing CoA ester content in in vivo myocardial tissue. In future, our conclusions regarding the role of acetylcarnitine to reduce acetyl-CoA/CoA could be confirmed by measuring these quantities in response to pathophysiological perturbations of cardiac substrate supply and energy demand.

Also of interest was the unaltered production rate of [1-13C]citrate and [5-13C]glutamate following dobutamine infusion, despite the documented/observed effects of the β-agonist on PDH, CAT and Krebs cycle fluxes. A previous steady-state, ex vivo 13C MRS study revealed that following dobutamine stimulation, 13C-glutamate production was reduced due to elevated flux through the Krebs cycle enzyme α-ketoglutarate dehydrogenase (αKGDH) compared with flux through the OMC40. A similar mechanism may have influenced our instantaneous hyperpolarised 13C MRS measurements, preventing alteration to the observed [5-13C]glutamate production in spite of increased Krebs cycle flux. In addition, balanced increases to [1-13C]citrate production by citrate synthase and [1-13C]citrate consumption by the next Krebs cycle enzyme, aconitase, may have masked any differences to alterations in the rate of [1-13C]citrate production. Further mathematical modelling is warranted to fully characterise how various pathophysiological conditions affecting Krebs cycle and OMC fluxes also influence the [1-13C]citrate and [5-13C]glutamate resonances.

To summarise, the results of this study suggest that acetyl-CoA produced from pyruvate dynamically cycles through the acetylcarnitine pool, ‘fine-tuning’ the instantaneous acetyl-CoA supply from carbohydrates to match Krebs cycle demand (Figure 6C). This buffering may enable acetyl moiety storage to encourage constant rates of oxidative ATP production. Further, acetyl-CoA:acetylcarnitine cycling may prevent static acetyl-CoA accumulation and its associated inhibitory effects.

Significance of the Work

Carnitine deficiency has been reported is numerous pathophysiological conditions in which cardiac energetics are also depleted, including old age41, pressure-overload hypertrophy23 and heart failure21, 42. Generally, it has been assumed that carnitine deficiency compromises myocardial energy metabolism by limiting fatty acid translocation across the mitochondrial membrane, thus decreasing fatty acid oxidation24. However, there is preliminary evidence that carnitine deficiency may also have a negative impact on glucose oxidation: for example, in the aged heart, acetyl-L-carnitine supplementation increases rates of overall ATP production, pyruvate uptake and mitochondrial pyruvate oxidation41, whereas, in the hypertrophic heart, proprionyl-L-carnitine supplementation improved contractility by means of a 2-fold increase in the contribution of glucose oxidation to overall ATP production24. Our work, alongside studies of carnitine depletion and repletion in disease, suggests that acetyl-CoA:acetylcarnitine cycling ‘fine-tunes’ mitochondrial acetyl-CoA availability in the heart, which appears key for maintenance of optimal cardiac function and energetics. We have demonstrated that hyperpolarised [2-13C]pyruvate metabolism can be measured in vivo with sub-second temporal resolution. Further studies with hyperpolarised [2-13C]pyruvate and MRS may help to clarify the mechanism by which carnitine deficiency contributes to heart failure in patients21, and potentially, to enable non-invasive clinical diagnosis of cardiomyopathies involving carnitine deficiency26. The impact of understanding and diagnosing carnitine deficiency in humans could be high, given the ease by which treatment, by normalising carnitine stores via oral supplementation, can already be achieved22.

Supplementary Material

Clinical Perspective.

Increasingly, changes in metabolic substrate utilisation and depleted myocardial energetics are considered to be causes, rather than consequences, of heart failure. Recent experimental studies have demonstrated that monitoring hyperpolarized 13C-labelled tracers with magnetic resonance spectroscopy (MRS) offers a new non-invasive method to investigate cardiac metabolism, and that the technology may be useful to determine diagnosis, prognosis, and optimize management in patients with heart disease. In the present study, we used the metabolic tracer hyperpolarised [2-13C]pyruvate with MRS to show that in healthy hearts, acetyl-CoA formed from pyruvate rapidly cycles through the mitochondrial acetylcarnitine pool. Further, we demonstrated that the acetylcarnitine pool functions in vivo to continually ‘fine-tune’ mitochondrial acetyl-CoA levels, providing an overflow pool to prevent potentially deleterious acetyl-CoA accumulation and a source of energetic substrate in response to rapidly increased cardiac workload. Many physiological and pathological conditions, including ageing, hypertrophy and heart failure, are characterised by depleted myocardial carnitine stores and energy depletion. Non-invasive assessment of the acetylcarnitine pool and other metabolic processes using hyperpolarised 13C MRS may advance our understanding of carnitine’s importance in heart failure, related abnormalities in heart failure and targeted metabolic treatments.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank Dr. Richard Veech, Dr. Rhys Evans, and Dr. Jan Henrik Ardenkjær-Larsen for their helpful suggestions.

Sources of Funding This work was supported by the National Institutes of Health (grant #1-F31-EB006692-01A1), the Wellcome Trust (MS was supported by a Sir Henry Wellcome Post-doctoral Fellowship), the Medical Research Council (MRC Grant G0601490), the British Heart Foundation (BHF Grants FS/10/002/28078 & PG/07/070/23365) and by GE-Healthcare.

Footnotes

Disclosures This study received research support from GE-Healthcare.

This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Linn TC, Pettit FH, Reed LJ. Alpha-keto acid dehydrogenase complexes. X. Regulation of the activity of the pyruvate dehydrogenase complex from beef kidney mitochondria by phosphorylation and dephosphorylation. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1969;62:234–241. doi: 10.1073/pnas.62.1.234. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hansford RG, Cohen L. Relative importance of pyruvate dehydrogenase interconversion and feed-back inhibition in the effect of fatty acids on pyruvate oxidation by rat heart mitochondria. Arch Biochem Biophys. 1978;191:65–81. doi: 10.1016/0003-9861(78)90068-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Collins-Nakai RL, Noseworthy D, Lopaschuk GD. Epinephrine increases atp production in hearts by preferentially increasing glucose metabolism. The American journal of physiology. 1994;267:H1862–1871. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.1994.267.5.H1862. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Owen OE, Mozzoli MA, Boden G, Patel MS, Reichard GA, Jr., Trapp V, Shuman CR, Felig P. Substrate, hormone, and temperature responses in males and females to a common breakfast. Metabolism. 1980;29:511–523. doi: 10.1016/0026-0495(80)90076-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Cross HR, Opie LH, Radda GK, Clarke K. Is a high glycogen content beneficial or detrimental to the ischemic rat heart? A controversy resolved. Circulation research. 1996;78:482–491. doi: 10.1161/01.res.78.3.482. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Saddik M, Lopaschuk GD. Myocardial triglyceride turnover and contribution to energy substrate utilization in isolated working rat hearts. The Journal of biological chemistry. 1991;266:8162–8170. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kreisberg RA. Effect of diabetes and starvation on myocardial triglyceride and free fatty acid utilization. The American journal of physiology. 1966;210:379–384. doi: 10.1152/ajplegacy.1966.210.2.379. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kreisberg RA. Effect of epinephrine on myocardial triglyceride and free fatty acid utilization. The American journal of physiology. 1966;210:385–389. doi: 10.1152/ajplegacy.1966.210.2.385. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Neubauer S. The failing heart--an engine out of fuel. The New England journal of medicine. 2007;356:1140–1151. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra063052. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Schroeder MA, Atherton HJ, Ball DR, Cole MA, Heather LC, Griffin JL, Clarke K, Radda GK, Tyler DJ. Real-time assessment of krebs cycle metabolism using hyperpolarized 13c magnetic resonance spectroscopy. Faseb J. 2009;23:2529–38. doi: 10.1096/fj.09-129171. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ardenkjaer-Larsen JH, Fridlund B, Gram A, Hansson G, Hansson L, Lerche MH, Servin R, Thaning M, Golman K. Increase in signal-to-noise ratio of > 10,000 times in liquid-state nmr. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2003;100:10158–10163. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1733835100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Golman K, in’t Zandt R, Thaning M. Real-time metabolic imaging. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2006;103:11270–11275. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0601319103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Abbas AS, Wu G, Schulz H. Carnitine acetyltransferase is not a cytosolic enzyme in rat heart and therefore cannot function in the energy-linked regulation of cardiac fatty acid oxidation. J Mol Cell Cardiol. 1998;30:1305–1309. doi: 10.1006/jmcc.1998.0693. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Friedman S, Fraenkel G. Reversible enzymatic acetylation of carnitine. Arch Biochem Biophys. 1955;59:491–501. doi: 10.1016/0003-9861(55)90515-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Pearson DJ, Tubbs PK. Carnitine and derivatives in rat tissues. Biochem J. 1967;105:953–963. doi: 10.1042/bj1050953. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Renstrom B, Liedtke AJ, Nellis SH. Mechanisms of substrate preference for oxidative metabolism during early myocardial reperfusion. The American journal of physiology. 1990;259:H317–323. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.1990.259.2.H317. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Fritz IB, Schultz SK, Srere PA. Properties of partially purified carnitine acetyltransferase. The Journal of biological chemistry. 1963;238:2509–2517. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lysiak W, Lilly K, DiLisa F, Toth PP, Bieber LL. Quantitation of the effect of l-carnitine on the levels of acid-soluble short-chain acyl-coa and coash in rat heart and liver mitochondria. The Journal of biological chemistry. 1988;263:1151–1156. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Fritz IB, Yue KT. Effects of carnitine on acetyl-coa oxidation by heart muscle mitochondria. The American journal of physiology. 1964;206:531–535. doi: 10.1152/ajplegacy.1964.206.3.531. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Saddik M, Gamble J, Witters LA, Lopaschuk GD. Acetyl-coa carboxylase regulation of fatty acid oxidation in the heart. The Journal of biological chemistry. 1993;268:25836–25845. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Paulson DJ. Carnitine deficiency-induced cardiomyopathy. Mol Cell Biochem. 1998;180:33–41. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Waber LJ, Valle D, Neill C, DiMauro S, Shug A. Carnitine deficiency presenting as familial cardiomyopathy: A treatable defect in carnitine transport. J Pediatr. 1982;101:700–705. doi: 10.1016/s0022-3476(82)80294-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Reibel DK, Uboh CE, Kent RL. Altered coenzyme a and carnitine metabolism in pressure-overload hypertrophied hearts. The American journal of physiology. 1983;244:H839–843. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.1983.244.6.H839. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Schonekess BO, Allard MF, Lopaschuk GD. Propionyl l-carnitine improvement of hypertrophied heart function is accompanied by an increase in carbohydrate oxidation. Circulation research. 1995;77:726–734. doi: 10.1161/01.res.77.4.726. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Lysiak W, Toth PP, Suelter CH, Bieber LL. Quantitation of the efflux of acylcarnitines from rat-heart, brain, and liver-mitochondria. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 1986;261:3698–3703. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Schroeder MA, Clarke K, Neubauer S, Tyler DJ. Hyperpolarized magnetic resonance: A novel technique for the in vivo assessment of cardiovascular disease. Circulation. 2011;124:1580–1594. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.111.024919. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Freeman R. Shaped radiofrequency pulses in high resolution nmr. Journal of Progress in Nuclear Magnetic Resonance Spectroscopy. 1998;32:59–106. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Jensen PR, Peitersen T, Karlsson M, In ’t Zandt R, Gisselsson A, Hansson G, Meier S, Lerche MH. Tissue-specific short chain fatty acid metabolism and slow metabolic recovery after ischemia from hyperpolarized nmr in vivo. The Journal of biological chemistry. 2009;284:36077–36082. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M109.066407. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Schroeder M, Cochlin L, Heather L, Clarke K, Radda G, Tyler D. In vivo assessment of pyruvate dehydrogenase flux in the heart using hyperpolarized carbon-13 magnetic resonance. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences USA. 2008;105:12051–12056. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0805953105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Tyler D, Schroeder M, Cochlin L, Clarke K, Radda G. The application of hyperpolarized magnetic resonance in the study of cardiac metabolism. Applied Magnetic Resonace. 2008;34:523–531. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Naressi A, Couturier C, Castang I, de Beer R, Graveron-Demilly D. Java-based graphical user interface for mrui, a software package for quantitation of in vivo/medical magnetic resonance spectroscopy signals. Comput Biol Med. 2001;31:269–286. doi: 10.1016/s0010-4825(01)00006-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Atherton HJ, Dodd MS, Heather LC, Schroeder MA, Griffin JL, Radda GK, Clarke K, Tyler DJ. Role of pyruvate dehydrogenase inhibition in the development of hypertrophy in the hyperthyroid rat heart: A combined magnetic resonance imaging and hyperpolarized magnetic resonance spectroscopy study. Circulation. 2011 doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.110.011387. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Atherton HJ, Schroeder MA, Dodd MS, Heather LC, Carter EE, Cochlin LE, Nagel S, Sibson NR, Radda GK, Clarke K, Tyler DJ. Validation of the in vivo assessment of pyruvate dehydrogenase activity using hyperpolarised 13c mrs. NMR in biomedicine. 2011;24:201–208. doi: 10.1002/nbm.1573. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Zierhut ML, Yen YF, Chen AP, Bok R, Albers MJ, Zhang V, Tropp J, Park I, Vigneron DB, Kurhanewicz J, Hurd RE, Nelson SJ. Kinetic modeling of hyperpolarized 13c1-pyruvate metabolism in normal rats and tramp mice. J Magn Reson. 2010;202:85–92. doi: 10.1016/j.jmr.2009.10.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Marquis NR, Fritz IB. The distribution of carnitine, acetylcarnitine, and carnitine acetyltransferase in rat tissues. The Journal of biological chemistry. 1965;240:2193–2196. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Grizard G, Lombard-Vignon N, Boucher D. Changes in carnitine and acetylcarnitine in human semen during cryopreservation. Hum Reprod. 1992;7:1245–1248. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.humrep.a137835. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.O’Donnell JM, Zampino M, Alpert NM, Fasano MJ, Geenen DL, Lewandowski ED. Accelerated triacylglycerol turnover kinetics in hearts of diabetic rats include evidence for compartmented lipid storage. American journal of physiology. 2006;290:E448–455. doi: 10.1152/ajpendo.00139.2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Lewandowski ED, Damico LA, White LT, Yu X. Cardiac responses to induced lactate oxidation: Nmr analysis of metabolic equilibria. The American journal of physiology. 1995;269:H160–168. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.1995.269.1.H160. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Sharma N, Okere IC, Brunengraber DZ, McElfresh TA, King KL, Sterk JP, Huang H, Chandler MP, Stanley WC. Regulation of pyruvate dehydrogenase activity and citric acid cycle intermediates during high cardiac power generation. The Journal of physiology. 2005;562:593–603. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2004.075713. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.O’Donnell JM, Kudej RK, LaNoue KF, Vatner SF, Lewandowski ED. Limited transfer of cytosolic nadh into mitochondria at high cardiac workload. American journal of physiology. Heart and circulatory physiology. 2004;286:H2237–2242. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.01113.2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Shigenaga MK, Hagen TM, Ames BN. Oxidative damage and mitochondrial decay in aging. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1994;91:10771–10778. doi: 10.1073/pnas.91.23.10771. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Pierpont ME, Foker JE, Pierpont GL. Myocardial carnitine metabolism in congestive heart failure induced by incessant tachycardia. Basic Res Cardiol. 1993;88:362–370. doi: 10.1007/BF00800642. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.