Abstract

BACKGROUND

Physicians may counsel patients who leave against medical advice (AMA) that insurance will not pay for their care. However, it is unclear whether insurers deny payment for hospitalization in these cases.

OBJECTIVE

To review whether insurers denied payment for patients discharged AMA and assess physician beliefs and counseling practices when patients leave AMA.

DESIGN

Retrospective cohort of medical inpatients from 2001 to 2010; cross-sectional survey of physician beliefs and counseling practices for AMA patients in 2010.

PARTICIPANTS

Patients who left AMA from 2001 to 2010, internal medicine residents and attendings at a single academic institution, and a convenience sample of residents from 13 Illinois hospitals in June 2010.

MAIN MEASURES

Percent of AMA patients for which insurance denied payment, percent of physicians who agreed insurance denies payment for patients who leave AMA and who counsel patients leaving AMA they are financially responsible.

KEY RESULTS

Of 46,319 patients admitted from 2001 to 2010, 526 (1.1%) patients left AMA. Among insured patients, payment was refused in 4.1% of cases. Reasons for refusal were largely administrative (wrong name, etc.). No cases of payment refusal were because patient left AMA. Nevertheless, most residents (68.6%) and nearly half of attendings (43.9%) believed insurance denies payment when a patient leaves AMA. Attendings who believed that insurance denied payment were more likely to report informing AMA patients they may be held financially responsible (mean 4.2 vs. 1.7 on a Likert 1–5 scale, in which 5 is “always” inform, p < 0.001). This relationship was not observed among residents. The most common reason for counseling patients was “so they will reconsider staying in the hospital” (84.8% residents, 66.7% attendings, p = 0.008)

CONCLUSIONS

Contrary to popular belief, we found no evidence that insurance denied payment for patients leaving AMA. Residency programs and hospitals should ensure that patients are not misinformed.

Electronic supplementary material

The online version of this article (doi:10.1007/s11606-012-1984-x) contains supplementary material, which is available to authorized users.

KEY WORDS: patient discharge, financial responsibility, hospital reimbursement

INTRODUCTION

Every year, approximately 500,000 patients (1–2%) leave U.S. hospitals against medical advice (AMA).1,2 Unfortunately, patients who leave AMA are more likely to die or be readmitted in 30 days.3,4

When patients leave the hospital AMA, physicians may frequently inform patients that they will be held financially liable for hospital charges.5 However, it is currently unclear whether or not insurers including Medicare and Medicaid deny payment to the hospital in these circumstances.6 In the only published study to date examining this issue, there were no instances of insurance declining payment for 104 patients who left AMA from an emergency department.5

No study has specifically examined whether insurers deny payment for hospitalized patients who leave AMA, or examined the beliefs of hospital-based physicians and whether they affect patient counseling. We aim to ascertain how often insurers refuse payment for patients who leave AMA, and to see if physician beliefs are associated with the way they counsel patients intending to leave AMA.

DESIGN

Study Design

This is a retrospective cohort study from July 2001 to March 2010 of all patients enrolled in the University of Chicago Hospitalist Study, a large ongoing study of quality of care and resource allocation for hospitalized general medicine patients.7 Trained research assistants approached newly admitted patients and asked them to participate in a brief inpatient interview and consent to review of their medical record and billing information. This study was approved by the Institutional Review Board at the University of Chicago.

Discharge Status and Billing Status

For each patient enrolled, trained research assistants abstracted the medical record to examine if the patient left AMA. A patient would be identified as leaving AMA based on physician notes, nursing notes, physician orders, or AMA forms signed by the patient. Review of a random sample of twenty patient charts categorized as “discharged AMA” was undertaken to validate this method.8 All patients in the Hospitalist Study with a discharge status of “left against medical advice” over 9 years where included in our study. This sample of encounters was then matched to billing data. Total charges, primary payer, amount paid by payer, adjustment by the hospital, and remaining balance were obtained from hospital billing data using AccountDoc and PainSir in the billing software, Centricity (IDX Systems, 2004). In cases where the patient had health insurance but no billing collections were obtained, we reviewed the reason for denial of payment.

Physician Survey

An Internet survey was conducted of general internal medicine attending physicians to determine the degree to which they agreed with the statement: “When a patient leaves the hospital against medical advice, insurance companies do not pay for the patient’s hospitalization”. Attendings responded using a 5-point Likert Scale ranging from strongly agree to strongly disagree. Attendings were also asked: “When a patient leaves the hospital against medical advice, how often do you inform them that they may be held financially responsible for the care they received?”, to which they responded on a 5-point Likert Scale ranging from never to always. Attending were also asked why they may advise patients of potential financial liability, and where they learned this practice using a response set of potential options and an additional field to write in other responses (see online Appendix).

Internal Medicine residents at the University of Chicago were asked to complete a paper survey using the same questions during morning report, journal club and lunch conference. We also surveyed an anonymous convenience sample of residents from nearby institutions at a local American College of Physicians meeting in October of 2010 to determine whether the beliefs and practices in our hospital were unique.

Statistical Analysis

Descriptive statistics of our sample including age, gender, race, type of insurance, length of stay, total charges, and principal diagnosis (ICD9) were examined using, STATA 11.0 (College Station, TX). T-tests and two-sided Fisher’s Exact Tests were used to compare AMA patients who were denied payment to those for whom insurance paid. Wilcoxon Rank Sum tests were used to compare attending and resident survey responses. Responses of “strongly agree or agree” were defined as “believing” that AMA patients are held financially responsible and two-sided Fisher’s Exact Tests were used to analyze the association between physician belief that patients are held financially responsible when discharged AMA and the frequency with which they inform patients that they may be held financially responsible. Two-sided Fisher’s exact tests were used to compare the origins of respondents’ beliefs about AMA discharges.

AMA Form Collection

We collected copies of the AMA forms that patients are asked to sign when they leave AMA to determine if they contain statements that insurance may refuse to pay. The Fellowship and Residency Electronic Interactive Database Access System (FREIDA), an online database maintained by the American Medical Association of accredited graduate medical education programs, was used to generate a list of academic hospitals affiliated with a medical school in Chicago. The research team contacted hospitals to acquire copies of their AMA forms.

RESULTS

From July 2001 to March 2010, 526 (1%, n = 46,319) patients admitted to the general medicine service were discharged against medical advice. The majority were male (54.2%), African American (87.4%), and had government-funded insurance (50.0% Medicaid, 27.8% Medicare) or were uninsured (13.9%). Few patients had private insurance (8.4%). The mean hospital charge for these admissions was $27,840 ±1,472, of which insurance paid on average $5,970 ± $603 (see Table 1).

Table 1.

Characteristics of Study Population (n = 526)

| Characteristic | n = 526(%)* |

|---|---|

| Male | 285 (54.2) |

| African American† | 458 (87.4) |

| Age in years, mean ± SD | 45 ± 1 |

| Length of stay in hospital, median (IQR) | 21–4 |

| Insurance Type | |

| Medicaid | 263 (50.0) |

| Medicare | 146(27.8) |

| No Payer | 73(13.9) |

| Private Payer | 44 (8.4) |

| Principal Diagnosis (ICD9)‡ | |

| HBSS Disease w/ Crisis (282.62) | 38 (7.2) |

| HIV (042) | 22 (4.2) |

| Congestive heart failure, unspecified (428.0) | 20 (3.8) |

| Due to vascular device, implant, and graft (996.62) | 17 (3.2) |

| Missing | 3 (0.6) |

| Secondary Diagnosis (ICD9) | |

| Tobacco use disorder (305.1) | 148 (28.1) |

| Essential hypertension, unspecified (401.9) | 130 (24.7) |

| Substance abuse§ (305.0, 305.5, 305.6, 305.9) | 111 (21.1) |

| Psychological disorders || (295.00-302.9, 307.0-190) | 89 (16.9) |

| Diabetes mellitus (250.0) | 78 (14.8) |

*Except for mean and length of stay which are reported as mean ± SD and median (IOR)

†White 6.3%, Hispanic 1.6%

‡International Statistical Classification of Diseases and Related Health Problems (World Health Organization 1977)

§Alcohol Abuse, Opioid Abuse, Cocaine Abuse, Other Mixed or Unspecified Drug Abuse

|| Includes all ICD-9 Mental Disorders: schizophrenic disorders, bipolar disorder, depression, anxiety, etc; does not included drug induced mental disorders like alcohol withdrawal

Of the 453 (86.1%) instances in which patients left AMA and had insurance, there were only 18 cases (4.0%) when insurance did not pay. Interestingly, patients who were denied payment were significantly less likely to be African American (55.6% vs 87.8% of those for whom payment was made, p = 0.001). Of the patients who were denied payment, none had any of the three most common principal diagnoses: sickle cell anemia, HIV, and congestive heart failure.

More characteristics of patients by whether or not their insurance paid are described in Table 2. Review of billing data demonstrated that the most common reasons for denial were untimely submission of the bill, confusion about patient identity, and extended utilization review. There were no instances in which an insurance company denied payment because the patient left against medical advice.

Table 2.

Characteristics of Patients Who Left AMA by Whether Insurance Paid

| Characteristic | Denied Payment (n = 18) | Payment Made (n = 435) | P value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Demographics | |||

| Male | 7 (38.9) | 230 (52.9) | 0.34 |

| Age, mean ± SD | 43 ± 19 | 45 ± 16 | 0.71 |

| Length of Stay, median (IQR) | 1 (1–3) | 2 (1–4) | 0.14 |

| Race | |||

| African American | 10 (55.6) | 380 (87.8) | 0.001 |

| White | 3(16.7) | 26(6.0) | |

| Other* | 5 (27.8) | 27(6.2) | |

| Insurance | |||

| Government (Medicare/Medicaid) | 14(77.8) | 395(90.8) | 0.09 |

| Private Payer | 4 (22.2) | 40 (9.2) | |

| Diagnosis | |||

| Most Common Principal Diagnoses (ICD9)† | |||

| HBSS Disease w/ Crisis (282.62) | 0 (0) | 38 (8.7) | 0.39 |

| HIV (042) | 0 (0) | 22(5.1) | 1.0 |

| Congestive Heart Failure, unspecified (428.0) | 0 (0) | 20(4.6) | 1.0 |

| Secondary Diagnosis (ICD9) | |||

| Tobacco Use Disorder (305.1) | 2 (11.1) | 112 (25.8) | 0.27 |

| Substance Abuse‡ (305.0, 305.5, 305.6, 305.9) | 5 (27.8) | 83 (19.1) | 0.36 |

| Psychological Disorders§ (295.00-302.9, 307.0-190) | 3(16.7) | 80(18.4) | 1.0 |

| Costs | |||

| Total charges (mean ± SD) | $14846 ± 4087 | $29376 ± 1699 | 0.08 |

| Total paid (mean ± SD) | $0 ± 0 | $7218 ± 715 | 0.04 |

| Total cost to hospital (mean ± SD) | $14846 ± 4087 | $22158 ± 1341 | 0.27 |

*1 (5.6%) Hispanic, 1 (5.6%) Asian/Pacific Islander, 3 (16.7%) Unknown

† International Statistical Classification of Diseases and Related Health Problems (World Health Organization 1977)

‡ Alcohol Abuse, Opioid Abuse, Cocaine Abuse, Other Mixed or Unspecified Drug Abuse

§ Includes all ICD-9 Mental Disorders: schizophrenic disorders, bipolar disorder, depression, anxiety, etc; does not included drug induced mental disorders like alcohol withdrawal

||Continuous variables analyzed with t-tests; dichotomous variables analyzed with Fisher’s Exact tests

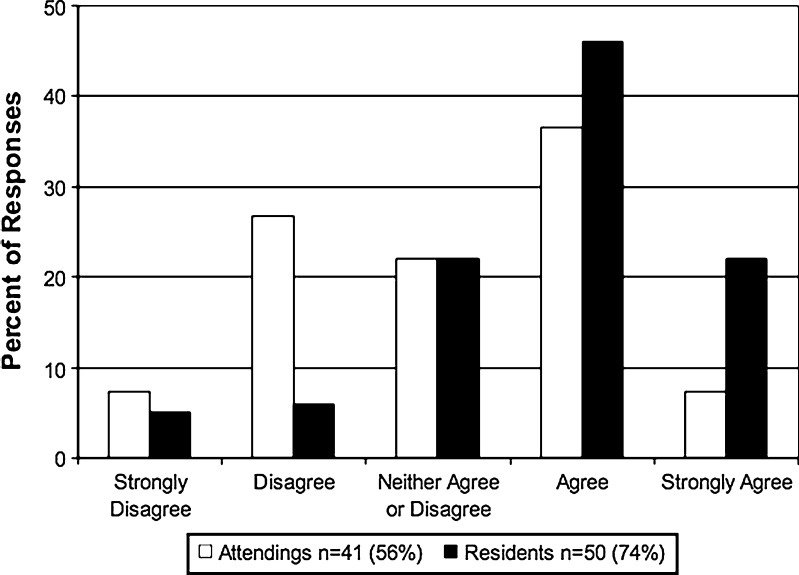

Of the general internal medicine physicians, 73.9% (51/69) of residents and 56.2% (41/73) of attending physicians completed the survey. While the resident survey was anonymous, attending responders did not differ from nonresponders with respect to gender or specialty. Most residents (68.0%) and nearly half attendings (43.9%) agreed or strongly agreed with the statement “when a patient leaves the hospital against medical advice, insurance companies do not pay for the patient’s hospitalization” (see Fig. 1). Also, most residents (70.6%) and half of attending physicians (51.2%) responded that they often or always inform patients that they may be held financially responsible if they leave AMA.

Figure 1.

Percentage of Physicians Who Believe Patients are Held Financially Responsible When They Leave AMA (difference between attending and resident responses analyzed using Wilcoxon Rank Sum test, showing residents agreed more strongly that patients are held financially responsible, p < 0.004).

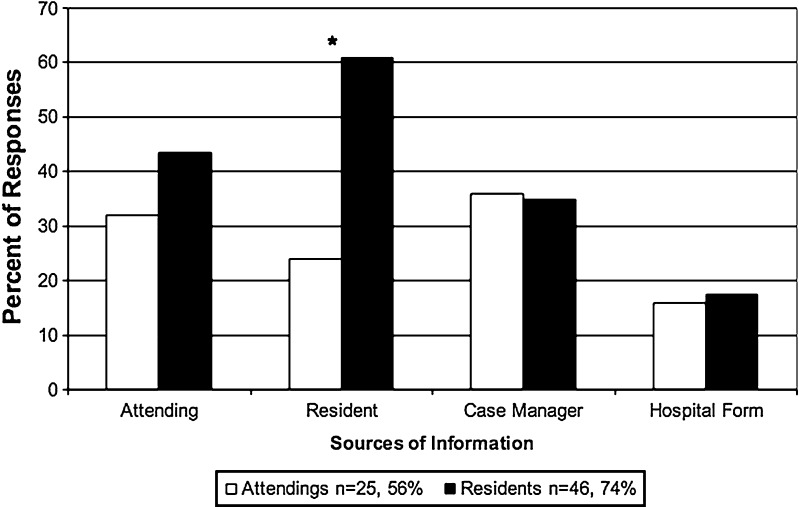

Attendings who believe insurance will not pay were more likely to report that they inform their patients that they might be held financially responsible (mean 4.2 vs. 1.7 among attendings believing insurance would not pay, on a Likert 1–5 scale, in which 5 is “always” inform, p < 0.001). Residents’ belief that insurance will not pay was not associated with a significant increase in their reported frequency of informing their patients that they might be held financially responsible (Likert mean = 4.2 believe vs. 3.75 don’t believe, p = 0.330). The most common reasons for informing patients were “so they will reconsider staying in the hospital” (84.8% residents, 66.7% attendings) and “to inform patients of their financial burden” (78.3% residents, 75.0% attendings). The most common way that doctors learned that insurance may not pay if patients leave AMA was from residents (60.9% of residents and 24.0% of attendings, p = 0.001) and case managers (34.8% residents, 36.0% attendings) (see Fig. 2). Others learned from the hospital form that is given to patients when they sign out against medical advice (17.4% residents, 16.0% attendings). A few residents (8.7%) and several attendings (24.0%) checked “other” and wrote in answers for how they learned, including “internet”, “rumor”, and “guess”.

Figure 2.

How Physicians Learned that Patients Leaving AMA May be Financially Responsible (physicians were instructed to check all response options that applied). *p = 0.006 by Fisher’s Exact test showing that among residents, other residents were more likely source of information regarding insurance denying payment for AMA patients compared to attendings. Fewer responses were noted for nurse, hospital administrator, medical school, hospital staff, and other.

Our convenience sample included 114 responses from residents representing 13 different Illinois internal medicine residency programs. Of the convenience sample, 40.4% (46) agreed or strongly agreed that insurance does not pay for AMA patients. In addition, 43.0% (49) indicated they often or always inform patients that they may be held financially responsible if they leave AMA.

AMA forms were obtained from 94.4% (17/18) of hospitals with internal medicine residency programs in the Chicago metropolitan area. Of note, only the AMA forms from two of the seventeen hospitals contained language about any possible financial consequences. One stated “I agree to be responsible for any part of the hospital bill not covered by insurance because I left the hospital,” the other, “I understand that some insurance companies refuse to pay for care provided during a stay ending in discharge against medical advice. In such instances, the patient becomes directly responsible for the entire bill.”

DISCUSSION

This is the first study of hospitalized patients demonstrating that physicians believe that patients are held financially responsible when a patient leaves AMA, despite little evidence of this in 9 years of billing data. Considering no instances were found in which third party payers refused to reimburse for an AMA discharge, it is surprising that the majority of residents and nearly half of attending physicians reported they believe that insurance will not pay when a patient leaves AMA and thus counsel patients accordingly. Our survey of residents at other institutions suggests this is not a single institution myth, but a pervasive “medical urban legend.”

Although no claims were denied by insurance because of AMA discharges, there was a small group of claims that were denied for administrative reasons. Patients in that group were less likely to be African American, which is particularly interesting because African American patients were more likely to leave AMA in this study. Considering that white patients in our sample were significantly more likely to have private insurance, this finding is likely explained by the fact that private insurance plans were more likely to deny payment for any reason. In future work, it is important to understand more about the practices of private insurers with respect to patients discharged AMA.

It appears that residents and case managers are the main sources through which this belief is propagated. However, many residents and attendings cited other sources including other attendings, nurses, medical school, the internet, hospital staff, and even the AMA form itself. These results are consistent with knowledge of how information passes through the densely connected social and professional networks in hospitals.9 Based on our results and previous studies on the development of practice styles,10 it is reasonable to assume that many, if not most, residents joining our network will quickly adopt this belief and practice.

Not surprisingly, resident and attending beliefs about what happens to patients that leave AMA are tightly linked to their behaviors, suggesting the importance of a targeted educational intervention. Education is especially important since when a patient is threatening to leave AMA and their physician is warning them about financial consequences, there has already been a breakdown in the patient–doctor relationship. Existing literature indicates that a patient-centered approach would involve meeting promptly with your patient, hearing their concerns and attempting to reach compromise that is safe and acceptable for the patient.20,21 Because a compromise that is acceptable to both parties cannot always be reached, there are indeed situations when physicians need to respect patient autonomy. While we understand physicians may want to inform patients of potential financial concern, it is not ethical to scare patients with misleading information. Therefore, hospitals should ensure that employees understand the financial responsibility of patients discharged AMA. Statements made by staff or written on hospital AMA forms threatening financial responsibility should be modified to reflect what actually happens. Our data indicate that many physicians, especially residents, inform patients they may be held financially liable for leaving AMA to make them reconsider staying in the hospital. Therefore, effective interventions should include education on what to do when a patient wants to leave AMA.11,12

This study has several limitations. First, our study was conducted predominantly at a single institution calling into question the generalizability of our findings to other centers. It is important to note that residents and attendings from our institution represent a broad sample of medical schools all over the country. In addition, the convenience sample includes an even broader sample of residency programs, including those who train predominantly international medical graduates. In attempting to explore whether this phenomenon was more widespread, we have encountered many anecdotal reports of beliefs or questions regarding this issue, highlighting the confusion of doctors and patients.14–17

Our patient cohort is also from a single institution because we only had access to billing data from our own hospital. Because insurance policies differ from state to state, our results may not apply to certain insurers in other states. Also, most patients in this study had government insurance, which is consistent with previous studies of patients that leave AMA.1,13 However, this limits our knowledge of how private insurance handles patients discharged AMA. Several sources, including a representative from Medicare, have confirmed that Medicare has no policy to deny payment of hospital charges to patients who leave AMA.18 Payments are made based on a determination of whether care was medically necessary, regardless of how the patient is discharged. Furthermore, we are unaware of any private insurance carrier policies to deny payment of hospital charges for patients signing out against medical advice. Lastly, the 1990 case of Arkansas Blue Cross and Blue Shield v Loretta Long is very relevant to this discussion. In this case, Arkansas Blue Cross attempted to exercise an exclusion policy against Loretta Long for an inpatient hospital stay that ended in discharge against medical advice. The Supreme Court of Arkansas ruled that Blue Cross Blue Shield were bound to pay for services incurred prior to discharge, regardless of discharge AMA, because a such an exclusion policy would “divest the insured of benefits already accrued, for which no reasonable basis exists” and was therefore “against public policy”.19 However, it is unclear how this ruling would affect insurer attempts to deny payment for rapid readmission for the same diagnosis. For these reasons, we believe a larger national survey of insurers would be critical to truly elucidate the industry standards regarding this topic.

Nevertheless, this study reveals that despite the widespread belief among inpatient physicians at one large academic institution that patients are held financially liable when patients leave AMA, there were no actual instances of insurance failing to pay hospital charges on this basis in a nine year cohort at the same institution. Education of health care workers, particularly physicians and case-workers, is needed to ensure physicians have accurate information when they are negotiating with a patient wanting to leave AMA. We are currently working to improve clinician communication with patients who want to leave against medical advice through the use of an educational video and website with resources.22 In addition to clarifying information about financial responsibility, the focus of our educational program is to highlight patient-centered strategies for negotiating the care of patients that want to leave AMA. Through formal training in communication, we hope to change future practice and improve outcomes.

Electronic supplementary material

(DOC 63 kb)

Acknowledgments

Contributors

We would like to acknowledge Debra Massi for facilitating contact with billing and clarifying data, Kimberly Beiting, Meryl Prochaska, and Paul Staisiunas for their administrative support, the Pritzker Scholarship and Discovery Quality and Safety Track and Pritzker Summer Research Program for encouraging this research.

Funding

We would like to acknowledge funding from AHRQ CERT Grant 1U18HS016967-01and NIA T35 Grant 5T35AG029795-02.

Prior Presentations

This research was presented as a poster at the 2011 American College of Physicians Meeting, April 8–10 in San Diego, CA, and the 2011 Society of Hospital Medicine Meeting, May 11–13 in Dallas, TX.

Conflict of Interest

Gabrielle R. Schaefer reports no potential conflict of interest. Heidi Matus reports no potential conflict of interest. John H. Schumann reports no potential conflict of interest. Keith Sauter reports no potential conflict of interest. Ben Vekhter reports no potential conflict of interest. David O. Meltzer reports a consultancy position at the Congress and Budget Office and grants from the NIH, RWJ, and AHRQ. Vineet Arora reports grants from the NIA, AHRQ, ACGME, and the ABIM Foundation.

Statement of Exemption

This study was determined to be exempt by the University of Chicago Biological Sciences Division Institutional Review Board.

REFERENCES

- 1.Ibrahim SA, Kwoh CK, Krishnan E. Factors associated with patients who leave acute-care hospitals against medical advice. Am J Public Health. 2007;97(12):2204–8. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2006.100164. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Aliyu ZY. Discharge against medical advice: sociodemographic, clinical and financial perspectives. Int J Clin Pract. 2002;56(5):325–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Glasgow JM, Vaughn-Sarrazin M, Kaboli PJ. Leaving against medical advice (AMA): risk of 30-day mortality and hospital readmission. J Gen Intern Med. 2010;25(9):926–9. doi: 10.1007/s11606-010-1371-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Southern W, Nahvi S, Arnsten J. Increased mortality and readmission among patients discharged against medical advice. J Hosp Med. 2010;5(3):S72–73. doi: 10.1016/j.amjmed.2011.12.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Wigder HN, Propp DA, Leslie K, Mathew A. Insurance companies refusing payment for patients who leave the emergency department against medical advice is a myth. Ann Emerg Med. 2010;55(4):393. doi: 10.1016/j.annemergmed.2009.11.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Matthews JL. (2008–10). Will going against medical advice cause medicare to deny coverage?. Available at: http://www.caring.com/questions/medicare-against-medical-advice. Accessed December 2011.

- 7.Meltzer D, Manning WG, Morrison J, et al. Effects of physician experience on costs and outcomes on an academic general medicine service: results of a trial of hospitalists. Ann Intern Med. 2002;137(11):866–74. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-137-11-200212030-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Arora VM, Johnson M, Olson J, et al. Using ACOVE quality indicators to measure quality of hospital care for vulnerable elders. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2007;55(11):1705–11. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2007.01444.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Meltzer D, Chung J, Khalili P, et al. Exploring the use of social network methods in designing health care quality improvement teams. Soc Sci Med. 2010;71(6):1119–30. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2010.05.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Chung PJ, Chung J, Shah MN, Meltzer DO. How do residents learn? The development of practice styles in a residency program. Ambul Pediatr. 2003;3(4):166–172. doi: 10.1367/1539-4409(2003)003<0166:HDRLTD>2.0.CO;2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Alfandre DJ. "I'm going home": discharges against medical advice. Mayo Clin Proc. 2009;84(3):255–60. doi: 10.4065/84.3.255. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Monico EP, Schwartz I. Leaving against medical advice: facing the issue in the emergency department. J Health Risk Manag. 2009;29(2):6,9, 13, 15. doi: 10.1002/jhrm.20009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ding R, Jung JJ, Kirsch TD, Levy F, McCarthy ML. Uncompleted emergency department care: patients who leave against medical advice. Acad Emerg Med. 2007;14(10):870–6. doi: 10.1111/j.1553-2712.2007.tb02320.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Arora V. Future docs blog: Help debunk a medical myth about patients leaving AMA [Internet]. Available at: http://futuredocsblog.com/2011/07/11/help-debunk-a-medical-myth-about-patients-leaving-ama/. Accessed December 2011.

- 15.The happy hospitalist: Will my insurance pay if I leave against medical advice (AMA)? Stop spreading the myth! [Internet]. Available at: http://thehappyhospitalist.blogspot.com/2011/05/will-my-insurance-pay-if-i-leave.html. Accessed December 2011.

- 16.DiNapoli M. M.D. to be: leaving the hospital against medical advice [Internet]. Available at: http://blog.timesunion.com/mdtobe/leaving-the-hospital-against-medical-advice/1191/. Accessed December 2011.

- 17.Yahoo answers: will your insurance cover services if you leave a hospital against medical advice? [Internet]. Available at: http://answers.yahoo.com/question/index?qid=20110807173519AALdsPW. Accessed December 2011.

- 18.Caring.com: will going against medical advice cause medicare to deny coverage? [Internet]. Available at: http://www.caring.com/questions/medicare-against-medical-advice. Accessed: December 2011.

- 19.Arkansas Blue Cross & Blue Shield v. Long 792 Ark. S.W. 2d 602. 1990.

- 20.Hertz BT. Act quickly and listen a lot what to do when a patient wants to leave AMA. American College of Physicians, Hospitalist, March 2010. Available at: http://www.acphospitalist.org/archives/2010/03/against.htm. Accessed December 2011.

- 21.Hwang SW. Discharge against medical advice. Web M & M, Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality, May 2005. Available at: http://www.webmm.ahrq.gov/case.aspx?caseID=96. Accessed December 2011.

- 22.Schaefer GR, Matus H, Schumann JH, Arora VM. Squidoo: leaving against medical advice. [Internet]. Available at: http://www.squidoo.com/discharge-ama. Accessed December 2011.

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

(DOC 63 kb)