Abstract

Genome-wide data sets are increasingly being used to identify biological pathways and networks underlying complex diseases. In particular, analyzing genomic data through sets defined by functional pathways offers the potential of greater power for discovery and natural connections to biological mechanisms. With the burgeoning availability of next-generation sequencing, this is an opportune moment to revisit strategies for pathway-based analysis of genomic data. Here, we synthesize relevant concepts and extant methodologies to guide investigators in study design and execution. We also highlight ongoing challenges and proposed solutions. As relevant analytical strategies mature, pathways and networks will be ideally placed to integrate data from diverse -omics sources in order to harness the extensive, rich information related to disease and treatment mechanisms.

Keywords: pathway analysis, gene set, enrichment methods, genome-wide association study, functional annotation, complex diseases

The search for pathways in complex diseases: a seminal moment

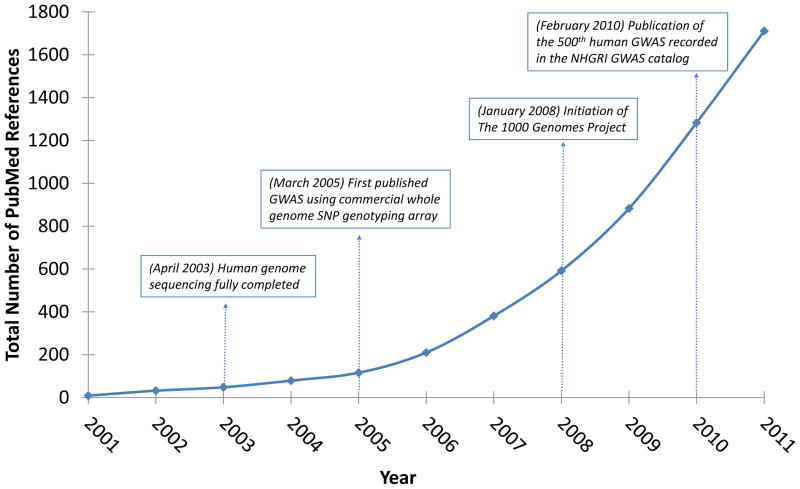

Since 2005, over 1000 human GWAS (genome-wide association study) publications have described genetic associations to a wide range of diseases and traits [1]. However, extending GWAS findings to mechanistic hypotheses about development and disease has been a major ongoing challenge. In particular, the focus on single loci has been confounded by two insights: (i) most GWAS-implicated common alleles and differentially-expressed genes on expression arrays have exhibited modest effect sizes; and (ii) genes function within biological pathways and interact within biological networks [2]. As such, genome-wide data sets are increasingly viewed as foundations for discovering pathways and networks relevant to phenotypes [3]. This trend is vital, given that pathway mechanisms are natural sources for developing strategies to diagnose, treat, and prevent complex diseases. In this context, it is not surprising that pathway-based analyses have exploded in use during the last 3–5 years (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

PubMed citations for “pathway analysis”: 2001-present. The use of pathway analysis has grown exponentially in the last 3–5 years. This explosion in use has followed major developments (shown in boxes) in characterizing the human genome and in performing genome-wide studies of complex diseases and traits. Data points represent the total number of references displayed through a PubMed search for “pathway analysis”, using date limits of January 1, 2001 and December 31 of the calendar year denoted on the x-axis.

In pathway analysis, gene sets corresponding to biological pathways (Box 1) are tested for significant relationships with a phenotype. Primary data for pathway analysis is commonly sourced from genotyping or gene expression arrays, though in theory any data elements that could be mapped to genes or gene products could be used. Importantly, analyzing genomic data through functionally-derived gene sets can reveal larger effects that are otherwise concealed from gene- or SNP-based (single nucleotide polymorphism) analysis. For example, high-profile studies in breast cancer [4], Crohn’s disease [5], and type 2 diabetes [6] demonstrate that functionally-related genes can collectively influence disease susceptibility, even if individual loci do not exhibit genome-wide significant association. As such, pathway analysis represents a potentially powerful and biologically-oriented bridge between genotypes and phenotypes.

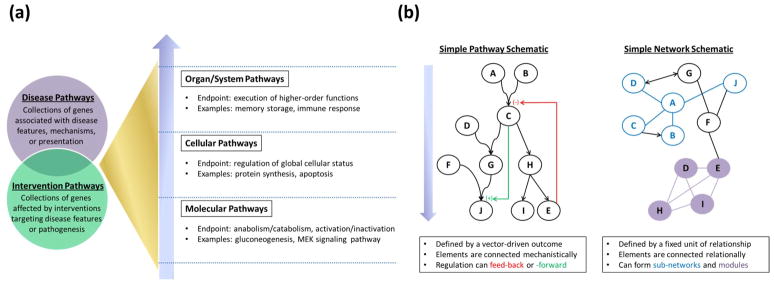

Box 1. Fundamental concepts about biological pathways and networks.

While unstated notions predate it, the first explicit description of a pathway as the events by which intermediates are processed in a defined sequence was provided in 1973 [84]. Recently, broader notions of pathways as collections of biologically-related genes [24] have attempted to fit evolving scientific theories and analyses. A systematic conceptualization of biological pathways (Figure Ia) posits that pathways are vector-driven toward an essential goal (i.e., their constituents as a whole are directed to a common, specific endpoint). Viewed this way, molecular pathways have an essential goal of basic biochemical action on molecules or compounds. Overarching this are cellular pathways that regulate global cellular status and organ/system pathways that execute broader physiological functions. The constituents of these pathways are typically connected through known or proposed mechanisms. Of note, the particular constituents of a pathway may be context-dependent – specifically, in relation to the biological outcome an investigator wishes to study.

In addition, two other types of pathways are important in the study of genetically-complex diseases (Figure Ia). Disease pathways have an essential goal of the pathogenesis of a disease and its features. For example, the Alzheimer’s disease pathway plausibly includes components from the organ/system pathway of memory, which itself has cellular and molecular underpinnings. By contrast, intervention pathways are defined within the setting of a therapy that targets disease features or pathogenesis, as in a pathway-based study of cisplatin sensitivity in ovarian cancer [85]. Importantly, disease and intervention pathways may include constituents with documented associations to a phenotype, but whose precise mechanistic roles are not yet known.

Networks can also collect genes and other biological elements for quantitative and visual assessment of relationships [86]. Unlike pathways, biological networks are not vector-driven toward an essential outcome (Figure Ib). Instead, networks are characterized by nodes that are connected by edges representing defined relationships. In a particular network, nodes may represent nearly any biological element, including genes, gene products, non-gene DNA sequences, pathways, diseases, therapies, or combinations thereof. Common examples of network relationships include binding in protein interaction networks and regulation by common factors in gene interaction networks. Finally, statistical networks display relationships, such as correlation, that are inferred from computational analyses [70]. A central outstanding question involves understanding the degree of connection between statistically-inferred networks and biological networks [87]. Software platforms for network analysis include IPA (Ingenuity Systems, http://www.ingenuity.com/) and Cytoscape (http://www.cytoscape.org/); two recent reviews discuss these and other module-based tools in detail [88, 89].

Despite their popularity and potential, strategies for pathway-based studies have progressed in the absence of guidelines, leading to ambiguity regarding optimal methods, high variability in results, and barriers to further application. With surging interest in pathway analysis and the emergence of next-generation sequencing data which will inevitably broaden its application, this is an ideal moment for a critical synthesis of current approaches and outlining targets for future development. Here, we clarify fundamental concepts about pathways and networks and their relationships to study design and execution. We also review extant strategies to detect pathway-phenotype association and highlight methodological challenges. Finally, we describe how pathways and networks are ideal vehicles for leveraging multi-omics data for discovery.

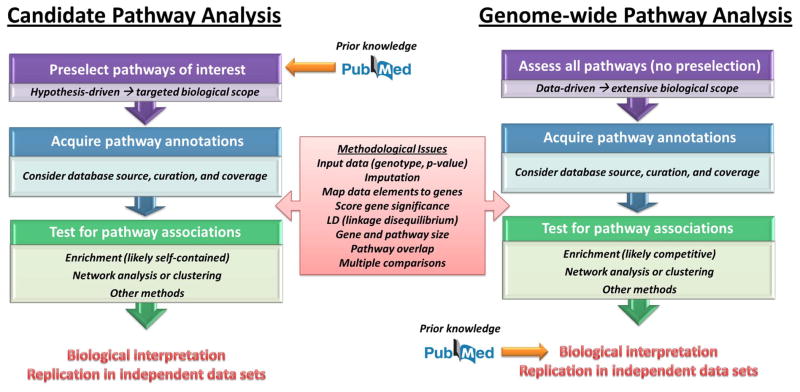

Selecting an overall study design

Broadly, there are two approaches to pathway-based genomic studies. Candidate pathway analysis is hypothesis-driven: pathways are preselected based on prior knowledge and insight. While the number of candidate pathways may vary with study goals (e.g. different effects may be seen within a large, complex pathway compared to numerous, smaller pathways), this approach is marked by its use of a biologically-targeted subset of genomic data. The other approach, genome-wide pathway analysis (GWPA), interrogates a complete genomic data set through pathways representing an extensive range of biology. Notably, the line between “targeted” and “extensive” biological coverage is not precisely drawn. While methods limited to GWPA have been used on data sets with only 1000 genes (~5% of the total number of human genes) [7], the optimal point of delineation between these two approaches warrants further examination.

There are several advantages to the candidate pathway approach. Focusing the scope of analysis can enable otherwise intensive procedures like genotype imputation and manual pathway curation; by maximizing annotation coverage and quality, these procedures can bridge differences in genotyping platforms across cohorts for replication or meta-analysis. Unfortunately, targeted biological coverage may fail to detect unexpected relationships, such as the association between inflammatory pathways and age-related macular degeneration [8]. Further, poor annotation of one pathway can be particularly limiting when only a few pathways are assessed. These traits make candidate pathway analysis most appropriate where computational resources are limited and where specific pathways are of a priori interest.

By contrast, GWPA maximally utilizes the available genomic data. As a result, this approach can more readily detect unexpected relationships, including those across diseases operating in different body systems [9]. However, GWPA is computationally intensive, requiring more stringent corrections for multiple comparisons and making procedures like imputation more challenging. While strategies to reduce the dimensionality of genome-wide data for pathway analysis are in active development [10, 11], they will need to be evaluated further ahead of widespread use. Finally, GWPA benefits from systematic follow-up to deal with the often high overlap of genes across multiple pathways and to evaluate results in view of prior knowledge.

Obtaining input genomic and pathway annotation data

Pathway analyses can utilize raw genotype data for individual subjects [6, 12, 13] or a list of p-values relating genes or SNPs to a phenotype [14–16]. Pathway-based tools for raw genotypes do not effectively include covariates but can naturally correct for linkage disequilibrium (LD) through permutation. In contrast, p-value distributions are readily accessible via other researchers and can be generated with application of covariates, but require corrections for LD based on reference populations. Investigators should consider their resources and study goals when selecting the most appropriate genomic data source.

In parallel, a pathway analysis is only as good as the functional information underlying its pathway definitions. Prominent pathway annotation databases exhibit diverse features (Table 1; also see the online resource Pathguide [17]). The ideal choice of database depends on several variables and their impact on study goals. For example, freeware databases are commonly used due to their ease of access, transparency of features, and visibility in publications. Commercial databases may require a significant investment; however, they are typically linked to user-friendly statistical analysis software and often include high-quality pathway graphics which can be exported to manuscripts. Investigators should weigh the relative importance of these factors during selection.

Table 1.

Prominent pathway annotation databases

| Name | Curationa | Major Features | URL |

|---|---|---|---|

| Biocarta | M | Driven by user input with expert review of some pathways | http://www.biocarta.com/ |

| DAVID | M/E | Augments and integrates annotations from other databases | http://david.abcc.ncifcrf.gov/ |

| Gene Ontology (GO) | M/E | Largest database; hierarchical structure; can filter data by evidence codes | http://www.geneontology.org/ |

| Ingenuity | M/E | Large collection of canonical pathways; high-quality pathway maps | http://www.ingenuity.com/ |

| Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes (KEGG) | M | Reference pathways (mosaics from several organisms) and organism-specific annotations; pathway maps link to closely-related genes | http://www.genome.jp/kegg/ |

| MetaCore | M | Extensive disease pathways; can edit pathway maps for publication | http://www.genego.com/ |

| MetaCyc | M | Metabolic pathways; can visualize connections among pathways | http://metacyc.org/ |

| Molecular Signatures Database (MSigDB) | M/E | Can download pathways from several other databases as a collection for input to analytical software; novel groupings (e.g., motif gene sets) | http://www.broadinstitute.org/gsea/msigdb/index.jsp/ |

| PANTHER | M | Can predicts protein functions from sequence and evolutionary data | http://www.pantherdb.org/ |

| Pathway Interaction Database (PID) | M/E | Broad range of cellular pathways with special focus on cancer signaling; can generate interaction maps from a list of genes | http://pid.nci.nih.gov/ |

| Reactome | M | Pathways are extensively cross-referenced to PubMed, HapMap, and other resources; can overlay expression or other data onto pathway maps | http://www.reactome.org/ReactomeGWT/entrypoint.html/ |

| ResNet Series | M/E | Regular updates through web server; optional user editing or text scanning of user documents; links to reference articles | http://www.ariadnegenomics.com/ |

Abbreviations: M = manual, M/E = manual and electronic

Pathway curation methods can also impact analyses. Most databases rely on expert review for pathway curation; however, users of these databases should be aware of their update intervals and criteria used as evidence for inclusion in pathways. Alternatively, electronic curation employs text-searching algorithms to infer functional relationships. While these inferred annotations can be useful for hypothesis generation, their accuracy is unreliable [18], making them unsuited to many pathway analyses. Finally, targeted manual curation can be particularly appropriate when an investigator has expertise in a biological realm that is poorly annotated in databases. While potentially time-consuming, manual curation can synthesize recent results with established relationships to produce novel candidate pathways [19, 20] or gene sets representing positive controls for pathway analysis [21].

Lastly, the biological coverage of pathway annotations should be considered. Across databases, similarly-named pathways can exhibit vast differences in constitution while differently-named pathways can exhibit significant overlap. As a result, investigators should attempt to match study goals with database coverage. For example, specialized, high-granularity databases are most useful for candidate studies of intricate signaling pathways, while canonical pathway collections (representing well-established pathways) provide a broad biological scope well-suited for screening-oriented studies.

This collective diversity of features is a major factor in explaining why different databases can yield divergent results from the same input data [22]. As such, an early discussion of pathway analysis recommended the use of multiple databases for each analysis [23]. This approach can balance the relative characteristics of each database used and can yield a measure of validation when different databases yield similar results. However, this strategy is most effective when it is supplemented by a systematic review of the results. Alternatively, further analyses can reveal broader findings that drive association signals across multiple smaller pathways: for example, one study analyzed pathway sets obtained through hierarchical clustering and identified an association between the canonical RAS/RAF/MAPK signaling pathway and breast cancer [4].

Preparing data for association testing

Systematic processing of input genomic data and pathway annotation data are vital for pathway analyses. While some relevant methods are actively evolving, optimized approaches to major issues can minimize variation in results and interpretation.

Pathway size

Most pathway analyses place constraints on pathway size: small pathways can exhibit false positive associations due to large single-gene or single-SNP effects [24], whereas large pathways are more likely to show association by chance alone [22]. The most common minimum threshold for pathway size appears to be ten genes [4, 6, 13, 25]. It is important for analysts to note that this threshold may exclude highly-specific and potentially-informative functional sets, including those involving protein complexes and DNA sequence motifs. Frequently-used maximum thresholds for pathway size include 100 genes [4] and 200 genes [6, 25]. Notably, in the latter two studies, upper limits of 300 genes [6] and 400 genes [25] did not alter the results. However, larger pathways are relatively rare and often derive their size from being more general in scope; thus, their exclusion may not significantly affect analyses or downstream biological interpretation. Overall, investigators should consider their study goals when applying such thresholds and should evaluate results in that context. While future efforts might develop size-dependent statistical corrections, at present the reporting of pathway size and related summary statistics (e.g. [26]) alongside association data can aid interpretation.

Pathway overlap

Genes and their products typically act in multiple pathways [2], and each role is potentially important to a disease or treatment mechanism. As a result, analyses can expect to have some degree of pathway overlap. However, high pathway overlap can obscure the true source of an association signal. While this problem can exist with any pathway analysis, Gene Ontology (GO) annotations are particularly susceptible due to the database’s large, hierarchical structure [27]. Some studies have restricted analysis of GO terms to certain levels in the hierarchy [13, 28], while a new Bayesian method incorporates the structure of the hierarchy as prior information into its pathway association metric [29]. However, users of these approaches should be aware that the information content at particular GO levels is unpredictable [30]. Pathway overlap can also be addressed during post-analysis to prioritize related pathways for further exploration. Extant strategies include hierarchical clustering in a study of breast cancer [4], overlap-based network creation in the visualization tool Enrichment Map [31], and the listing of overlapping pathways alongside results in the analytical software PARIS [32].

Assigning data elements to genes

Genomic data has historically been integrated into pathways by mapping assayed elements to genes. For SNP-based genotyping arrays, this is not straightforward because many array SNPs are not located in known coding or regulatory regions. In one study, all SNPs that were not be mapped to a single gene through a reference genome build were discarded, but this resulted in a loss of more than 25% of assayed SNPs [33]. Alternatively, each unmapped SNP can be assigned to its nearest gene [34]. However, evolving theories suggest that sequences may not be associated to genes based on closest proximity, and may not even be solely associated to one gene [35, 36]. Hence, many studies assign unmapped SNPs to all genes within a distance window, ranging from 10 kb to 500 kb [13, 25, 26, 37]. Studies taking this approach should beware that some SNPs may not be functionally related to their assigned gene(s). In addition, SNPs that map to multiple genes in the same pathway can yield spurious pathway association. This issue is particularly important for genes (such as the MHC/HLA genes) that cluster in the genome and belong to the same pathway, because variants in those genomic regions can potentially map to all genes in the pathway. Finally, given the importance of SNP-to-gene mapping for pathway analyses, investigators should be aware that imputation can increase gene coverage by characterizing SNP genotypes that are not directly available in a particular data set. Imputation can be particularly useful for bridging differences in genotyping platforms across cohorts for replication and meta-analysis, and can also enable investigation of rare alleles and copy number variants (CNVs) that are less-represented on standard platforms [38].

Calculating gene significance and accounting for LD

Most pathway analysis tools utilize one association signal per gene. While expression arrays yield a single p-value for each gene, SNP arrays include multiple signals per gene, some of which are correlated. As such, some studies use the minimum SNP-level p-value within a gene as the operative signal [4, 25, 33, 34]; however, this approach will not detect additive effects among SNPs with moderate individual association. For methods that combine SNP-level signals, including those based on the truncated product method [14], LD must be accounted for to prevent highly-correlated SNPs from biasing gene-level significance. Strategies to accomplish this include discarding SNPs that depart from LD at a preset threshold [25, 26, 39] and adapting principal component analysis to extract the most independent signals within a gene [10, 11, 26]; unfortunately, these methods can eliminate substantial information. Alternatively, the SNP ratio test [40] and the “set-based analysis” in PLINK [41] use phenotype permutation to naturally correct for biases introduced by LD and gene size; however, these tools require raw genotype data and are computationally demanding, making them better suited for studies of candidate pathways with relatively few genes. Notably, recently-developed methods that accept p-values as input and account for LD through simulations [42, 43] or genotype permutation [32] are computationally efficient and may represent new paradigms as their power is honed and evaluated.

Analytical methods to detect pathway-phenotype relationships

Following data processing, analytical methods can be applied to test for significant pathway-phenotype relationships. Prominent examples of pathway-based analytical tools and their salient features are provided in Table 2. Notably, one class of tools employs text-mining of published abstracts to identify potential pathway-phenotype relationships. These tools query a list which may include SNPs meeting a p-value threshold, genes from candidate pathways, or pathways themselves, among other possibilities. Text-mining approaches have efficiently identified potential interactions among genes associated with neurodegenerative brain changes [20] and have equally been applied to generate a candidate pathway based on regulation or interaction with BRCA2 [44].

Table 2.

Examples of publically-available pathway-based analytical tools

| Name | Typea | Input Data | Analytical Method | Corrections Included | Ref |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Chilibot | TM | Word List | Searches PubMed abstracts for relationships among word list; can distinguish biological concepts (e.g., activation, inhibition) | N/A | [90] |

| GenGen | C | Raw genotype data | Uses best p-value as gene-wide score and calculates rank-based Kolmogorov-Smirnov-like pathway statistic with permutation | LD, pathway size, gene size, FDR | [49] |

| GeSBAP | C | Gene or SNP p-values | Uses best p-value as gene-wide score and performs rank-based Fisher’s exact test to detect pathway enrichment | FDR | [91] |

| GRAIL | TM | SNPs or genomic regions | For multiple disease-associated regions, identifies functionally-related genes that likely highlight causal pathways | Number of genes per region | [92] |

| GRASS | SC | Raw genotype data | Uses principal component analysis to select representative eigenSNPs for each gene for pathway-based ridge regression | LD, gene size, FDR | [93] |

| GSA-SNP | C | SNP p-values | Uses -log(kth best p-value) as gene-wide score and calculates a z-score, iGSEA, or MAXMEAN statistic for the pathway | Pathway size, FDR | [52] |

| GSEA-P | C | Gene p-values | Calculates rank-based Kolmogorov-Smirnov-like pathway statistic with phenotype permutation | LD, pathway size, FDR | [94] |

| GSEA-SNP | SC | Raw genotype data | Uses all SNPs for a pathway MAX-test (maximum of Cochran-Armitage trend tests under 3 genetic models) with permutation | LD, pathway size, gene size, FDR | [50] |

| MAGENTA | C | SNP p-values | Modified approach based on GSEA-SNP for meta-analytic data | LD, gene size, FDR | [95] |

| PARIS | SC | SNP p-values | Identifies the significant genomic features within a pathway and performs genomic permutation to assess pathway significance | LD, pathway size, gene size, FDR | [32] |

| PLINK set test | SC | Raw genotype data | For SNPs passing a p-value threshold, calculates the average test statistic for the independent SNPs within a pathway | LD, pathway size, gene size, FDR | [41] |

| SNP Ratio Test | SC | Raw genotype data | Calculates the ratio of significant SNPs to all SNPs in a pathway and uses phenotype permutation to calculate empirical p-value | LD, pathway size, gene size, FDR | [40] |

Abbreviations: TM = text-mining, C = competitive enrichment, SC = self-contained enrichment

By contrast, pathway enrichment tools assess for a statistically-significant distribution of association within a pathway. Competitive enrichment methods compare the collective association within a pathway to the collective signal among genes not in the pathway [45]. As a result, competitive methods are not suitable for candidate pathway analyses that do not have an appropriate complement of data from outside of the candidate pathways. Meanwhile, self-contained enrichment methods test the signal within a pathway against simulated data sets which are expected to have no significant phenotype association [45, 46]. Self-contained methods can be challenging to use in a screening-oriented GWPA due to the computational demand of generating simulated data sets. In addition, self-contained approaches are particularly susceptible to false positives through genomic inflation, as each pathway is evaluated independently from any other data on the source assay. While one study [47] normalized all association statistics to a genomic inflation factor calculated by PLINK, best practices in this area have not yet been settled. Competitive tests are more robust in controlling genomic inflation, but they can also relinquish power in data sets with diffuse association signal [45]. As such, the optimal method depends on study goals, data set properties, and computational resources.

Among extant competitive enrichment methods, three analytical frameworks predominate. In the first of these, threshold-based approaches, hypergeometric, chi-square, or Fisher’s exact test statistics are used to identify pathways that are overrepresented among the “significant” markers under study. Notably, the threshold for “significance” is arbitrary and can affect results [48]; observed SNP-level thresholds have ranged from p < 0.05 [37] to p < 5 × 10−8 [34]. In contrast, rank-based approaches order all of the markers being studied by their significance and then test for pathways that have lower rankings than the overall distribution. While the rank-based tools GenGen [49] and GSEA-SNP [50] use a Kolmogorov-Smirnov-like running sum that gives greater weight to more significant markers, others rely on MAXMEAN-related statistics as potentially powerful and efficient alternatives [51–53]. Compared with threshold-based methods, rank-based approaches more naturally account for differences in significance among markers [24] but may also be heavily influenced by a few highly-significant markers [54]. Finally, z-score methods infer enrichment based on deviation from a normal distribution that accounts for the size of each pathway [52, 55]; while these methods are sensitive and fast, their error rates have not been well characterized. Self-contained enrichment methods employ even more diverse statistical methods to combine the p-values within a pathway into an aggregated measure (Table 2). However, in the absence of large-scale power comparisons among related methods across several well-characterized data sets, the choice of a particular enrichment tool may be less important than understanding the relative strengths and limitations of these broader categories.

An alternative to enrichment methods are module-based approaches, which examine sets defined by other biological characteristics for meaningful pathways contained therein. For example, one study used hierarchical clustering to form modules of co-expressed genes across multiple inflammatory diseases; subsequent analysis of these modules suggested a role for interferon-inducible signaling in tuberculosis [56]. Gene modules can also be defined through protein interaction networks, as in a study that associated genetic variants in glutamate pathways to brain glutamate concentration in multiple sclerosis [57]. Importantly, recent studies are combining enrichment and module-based methods to point to broader findings. For example, network analysis of enriched pathways revealed major roles for antigen presentation and interferon signaling in rheumatoid arthritis [58].

Finally, developing strategies are targeting specific pathway-based challenges. For example, machine learning approaches [11, 59] attempt to identify the most informative subsets of genes within pathways for association. Networks have been effective in studies of rare variants, as with the identification of a synaptogenesis gene network affected by rare CNVs in autism [60]. Pathway-based methods for studying rare variants using genomic-region-based mapping and self-contained tests are also evolving [61, 62]. Indeed, the appeal of pathways and networks will continue to expand as their associated tools progress to analyze a variety of data through user-friendly platforms.

Post-analysis considerations

Following pathway analysis, appropriate data reporting and interpretation are imperative. Currently, bias introduced by gene size is less commonly addressed than bias from pathway size. In particular, large genes containing many SNPs are more likely to contain significant SNPs by chance alone [63]; for analyses, this can favor pathways containing large genes. Analytical tools that employ permutations naturally control for gene size by comparing the actual association data to the distribution of association statistics generated from randomly permuted data sets expected to reflect chance-based confounding effects. Other approaches [41, 42] allow users to restrict analysis to a subset of the most significant SNPs in each gene: for large genes, this may eliminate some spuriously-associated SNPs and thus limit their impact on the pathway analysis. At minimum, studies should discuss potential impacts of gene and pathway size on their results. Other sources of bias that should be addressed include the capacity for strongly-associated markers to drive pathway association and the possible effects of SNPs being assigned to multiple genes.

Correction for multiple comparisons must also be applied to pathway p-values to control for false positives. As in other areas of statistical genomics, optimizing methods for correction is a work in progress. Bonferroni-related methods seem too conservative for pathway analyses because they do not allow for dependence across pathways. False discovery rate (FDR) approaches [64] are frequently-applied in pathway analyses [6, 26, 48], while newer FDR-based [65] and bootstrapping [39] methods that permute on raw genotypes can better account for pathway overlap but require large computational capacity.

Fundamentally, these approaches to bias are best complemented by replication of pathway analysis findings in independent data sets. Strategies for pathway analyses can flexibly adapt to differences across data sets, and while these differences might impact SNP- or gene-level statistics [66], legitimately-associated pathways would be expected to exhibit significance or a strongly-trending signal across multiple studies. In this effort, a systematic framework illustrating key choices in pathway analyses (Figure 2) will limit major contributors of variance across studies and will guide investigators in selecting approaches that fit their study goals.

Figure 2.

An Informed Guide to Pathway Analysis. Broadly, there are two approaches to pathway analysis. In candidate pathway analysis, prior knowledge is used to select pathways hypothesized to have a relationship with a phenotype. In contrast, genome-wide pathway analysis is designed to uncover significant pathway-phenotype relationships within a large data set; insight and prior knowledge are then used to interpret the findings. In both approaches, care must be taken in acquiring pathway annotations and in selecting an appropriate analytical test for association. In addition, other methodological issues (red box) guide the choice of approach and impact strategies for confounding factors. Finally, replication of pathway analysis findings in independent data sets is imperative in validating results to extend their impact.

Future developments in genomic data analysis

Development of methods and tools related to pathway analysis is ongoing and dynamic. In particular, because pathways are of broad interest, targeted adaptations to their associated databases would expand their utility for investigators from a variety of backgrounds. These adaptations might include simpler search and download mechanisms, consistency in pathway names and classifications, and methods for describing pathway overlap. In addition, a universal format for annotation files might encourage interoperability among analytical tools, allowing investigators flexibility to precisely match their databases and statistical methods of choice.

Two recent trends among databases are also promising. Specialized disease databases, such as AlzGene [67] and the UCSC Cancer Genomics Browser [68], can aggregate salient information from diverse studies on a particular disease. These targeted resources are particularly up-to-date and can facilitate collaboration within highly-investigated diseases. Functional annotation of genes is also becoming prominent. These annotations draw on experimental data that indicates function, location of action, or physiological region of association [69], and can allow investigators to develop candidate pathways related to localized anatomical or physiological derangements. Extensions of this concept across disciplines will likely be a prime area of advancement.

In future pathway analysis platforms, computational efficiency will be highly-valued given the impressive granularity of next-generation sequencing data. In addition, investigators may wish to use different genomic data sets, pathway annotation databases, and analytical parameters depending on study resources and goals; as such, tools that are flexible to various study approaches will maximize their impact. Finally, given that genes constitute only 1–2% of the human genome, strategies to leverage both genic and non-genic data for pathway analysis may provide increased power to detect meaningful functional sets.

Meanwhile, complementary methods can extend the biological reach of pathway-based results. For example, it is not yet understood whether gene interactions are more likely within a given pathway or across different pathways in a network. A comparative study of epistasis in pathways and networks, perhaps utilizing novel techniques for its detection within population data [70–73], could inform future strategies in this area. A related area of development involves using known protein interactions to generate subnetworks from enriched pathways; these subnetworks can highlight novel candidate genes [74] or regulatory relationships [75] from significant pathways.

Nevertheless, the ongoing development of pathway-based tools would benefit from further empirical evaluation of current approaches. For example, a creative meta-analysis might examine how various association metrics affect the likelihood of replication of findings. In addition, testing association methods against well-calibrated positive and negative control datasets might illuminate their relative capabilities. Notably, one study employed multiple pathway analysis algorithms using an extensively-explored Crohn’s disease data set [76]; however, the algorithms chosen were highly-disparate in their null hypotheses and approaches to LD, making it difficult to uniformly compare their results. Alternatively, multi-site collaborations might simultaneously analyze several large data sets using a small number of analytical tools in the same conceptual category; comparisons of the results would advance the underlying science and critically evaluate tools against closely-related options.

Finally, methods for integrating different types of association signals are developing. A nascent view proposes that combining genome-wide expression and genotyping data into a joint quantitative signal can increase power for discovery [6, 37, 77, 78]. One particularly attractive feature of this view is that it augments structure (genotype) with function (expression). Indeed, one study demonstrated that SNPs correlated with gene expression changes (expression quantitative trait loci = eQTLs) were more likely to show disease association than other SNPs from a GWAS array [79]. Relatedly, visualization tools can graphically overlay association metrics onto other data in order to prioritize markers. Visualization has been used to integrate SNP association with quantitative imaging phenotypes [80], among other examples.

Pathways and networks: bridging multi-omics data

As pathway analysis of genomic data has exploded in use, its methods have matured, its results are beginning to meet its potential, and points of consensus are emerging for its continued application and future development. In the coming years, we anticipate that pathways and networks will assume a farther-reaching role in view of the need to integrate multi-omics data through systems biology approaches [81, 82]. A variety of large-scale strategies are being used to study complex diseases, including genomic, transcriptomic, proteomic, and metabolomic approaches, and data from all of these sources can be analyzed through pathways and networks representing coordinated functions and relationships. Importantly, while gene associations do not always indicate therapeutic targets [83], pathways and networks implicated by analyses at multiple levels would be prime targets for therapies. Integrating large-scale data assayed through diverse strategies related to structure and function would provide a fertile process for exploring connections between replicable, statistical association and meaningful biology. As such, the role of pathways and networks as the hub for this integration will be vital in the years to come.

Figure I.

A primer on biological pathways and networks. (a) The major types of biological pathways are shown along with a representation of their relationships among each other. Each type of pathway is defined by its essential goal. Molecular pathways have an essential goal of basic biochemical action (biosynthesis, biodegradation, translocation, transformation, activation, or inactivation) on molecules or compounds. Cellular pathways regulate global cellular status, while organ/system pathways execute higher-order physiological functions. (b) Pathways and networks, while complementary sets of biological elements, differ in key respects. Pathways can include directional regulation (shown in red and green) and branching, but are nevertheless vector-driven to an essential outcome. While elements in pathways are typically connected mechanistically, network elements are connected through shared relationships that may not indicate an action. As such, networks are not vector-driven from a starting point to an essential outcome. Networks can be divided into subnetworks (shown in blue) exhibiting all elements connected to a central node (“A” in this example) or into modules (shown in purple) that exhibit a high density of connections.

Acknowledgments

Support for this work was provided by the Indiana University Medical Scientist Training Program grant NIGMS GM077229-02 (VKR), the National Science Foundation grant IIS-1117335 (LS), and the National Institutes of Health grants AG024904 (AJS), AG032984 (AJS), AG036535 (AJS), AG10133 (AJS), AG19771 (AJS), LM010098 (JHM), LM009012 (JHM), and AI59694 (JHM). The authors would also like to thank the two anonymous reviewers for their thoughtful comments and suggestions to improve the manuscript.

Glossary

- Bootstrapping

a method that assesses the uncertainty of a statistical estimate through recalculation of the statistic using repeated, random sampling of the original data set

- Commercial pathway database

a collection of pathway annotation data that is available for private purchase by investigators

- Covariate

a variable that is possibly predictive of the outcome under study; for example, genetic analyses often attempt to account for the effects of variables such as age and gender in order to precisely determine statistical relationships between genetic factors and phenotypes

- Freeware pathway database

a collection of pathway annotation data that is publically available without cost to the user

- Genome-wide association study (GWAS)

a large-scale study that assays genetic variants across the entire genome along with quantitative or categorical phenotype status in order to detect genotype-phenotype associations

- Genomic inflation

the systematic increase of association statistics from a genome-wide study due to population stratification or other confounding factors

- Genotype imputation

the process of probabilistically predicting genotypes that are not directly assayed (by not being represented on that genotyping platform or via localized experimental failure) with a particular array

- Granularity

a description of the scale or level of detail in a set of data

- Linkage disequilibrium (LD)

the non-random association of alleles at two or more loci; in other words, the occurrence of combinations of alleles at different frequencies than would be expected through a random formation of haplotypes

- Permutation

the process of calculating the distribution of a test statistic under the null hypothesis through repeatedly rearranging the labels in a dataset; for example, in case-control studies, phenotype statuses of subjects are randomly rearranged in order to assess the distribution of an association statistic under the null hypothesis of no significant association between a marker and phenotype status

- Replication

the repetition of a research study in an independent sample in order to verify firstline results and to determine whether effects can be generalized beyond the initial sample

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors maybe discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Hindorff LA, et al. A Catalog of Published Genome-Wide Association Studies. National Human Genome Research Institute; 2011. http://www.genome.gov/gwastudies. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Schadt EE. Molecular networks as sensors and drivers of common human diseases. Nature. 2009;461:218–223. doi: 10.1038/nature08454. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hirschhorn JN. Genomewide Association Studies — Illuminating Biologic Pathways. New England Journal of Medicine. 2009;360:1699–1701. doi: 10.1056/NEJMp0808934. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Menashe I, et al. Pathway Analysis of Breast Cancer Genome-Wide Association Study Highlights Three Pathways and One Canonical Signaling Cascade. Cancer Research. 2010;70:4453–4459. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-09-4502. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Wang K, et al. Analysing biological pathways in genome-wide association studies. Nat Rev Genet. 2010;11:843–854. doi: 10.1038/nrg2884. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Zhong H, et al. Integrating pathway analysis and genetics of gene expression for genome-wide association studies. Am J Hum Genet. 2010;86:581–591. doi: 10.1016/j.ajhg.2010.02.020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Abatangelo L, et al. Comparative study of gene set enrichment methods. BMC Bioinformatics. 2009;10:275. doi: 10.1186/1471-2105-10-275. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Telander DG. Inflammation and Age-Related Macular Degeneration (AMD) Seminars in Ophthalmology. 2011;26:192–197. doi: 10.3109/08820538.2011.570849. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Eleftherohorinou H, et al. Pathway Analysis of GWAS Provides New Insights into Genetic Susceptibility to 3 Inflammatory Diseases. PLoS One. 2009;4:e8068. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0008068. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Chen X, et al. Pathway-based analysis for genome-wide association studies using supervised principal components. Genetic Epidemiology. 2010;34:716–724. doi: 10.1002/gepi.20532. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Zhao J, et al. Pathway-based analysis using reduced gene subsets in genome-wide association studies. BMC Bioinformatics. 2011;12:17. doi: 10.1186/1471-2105-12-17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Chen M, et al. Incorporating Biological Pathways via a Markov Random Field Model in Genome-Wide Association Studies. PLoS genetics. 2011;7:e1001353. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1001353. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Wang K, et al. Pathway-based approaches for analysis of genomewide association studies. Am J Hum Genet. 2007;81:1278–1283. doi: 10.1086/522374. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Askland K, et al. Ion channels and schizophrenia: a gene set-based analytic approach to GWAS data for biological hypothesis testing. Human Genetics. 2011:1–19. doi: 10.1007/s00439-011-1082-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lascorz J, et al. Consensus pathways implicated in prognosis of colorectal cancer identified through systematic enrichment analysis of gene expression profiling studies. PLoS One. 2011;6:e18867. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0018867. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Peng G, et al. Gene and pathway-based second-wave analysis of genome-wide association studies. Eur J Hum Genet. 2010;18:111–117. doi: 10.1038/ejhg.2009.115. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Bader GD, et al. Pathguide: a Pathway Resource List. Nucleic Acids Research. 2006;34:D504–D506. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkj126. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Camon EB, et al. An evaluation of GO annotation retrieval for BioCreAtIvE and GOA. BMC Bioinformatics. 2005:6. doi: 10.1186/1471-2105-6-S1-S17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Swaminathan S, et al. Amyloid pathway-based candidate gene analysis of [(11)C]PiB-PET in the Alzheimer’s Disease Neuroimaging Initiative (ADNI) cohort. Brain Imaging Behav. 2011 doi: 10.1007/s11682-011-9136-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Sloan CD, et al. Genetic pathway-based hierarchical clustering analysis of older adults with cognitive complaints and amnestic mild cognitive impairment using clinical and neuroimaging phenotypes. American Journal of Medical Genetics Part B: Neuropsychiatric Genetics. 2010;153B:1060–1069. doi: 10.1002/ajmg.b.31078. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Zhang M, et al. Pathway Analysis for Genome-Wide Association Study of Basal Cell Carcinoma of the Skin. PLoS One. 2011;6:e22760. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0022760. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Elbers CC, et al. Using genome-wide pathway analysis to unravel the etiology of complex diseases. Genetic Epidemiology. 2009;33:419–431. doi: 10.1002/gepi.20395. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Cantor RM, et al. Prioritizing GWAS results: A review of statistical methods and recommendations for their application. Am J Hum Genet. 2010;86:6–22. doi: 10.1016/j.ajhg.2009.11.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Holmans P. Statistical methods for pathway analysis of genome-wide data for association with complex genetic traits. Advances in genetics. 2010;72:141–179. doi: 10.1016/B978-0-12-380862-2.00007-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Perry JR, et al. Interrogating type 2 diabetes genome-wide association data using a biological pathway-based approach. Diabetes. 2009;58:1463–1467. doi: 10.2337/db08-1378. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ballard D, et al. Pathway analysis comparison using Crohn’s disease genome wide association studies. BMC Medical Genomics. 2010;3:25. doi: 10.1186/1755-8794-3-25. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Yon Rhee S, et al. Use and misuse of the gene ontology annotations. Nat Rev Genet. 2008;9:509–515. doi: 10.1038/nrg2363. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Higareda-Almaraz JC, et al. Proteomic patterns of cervical cancer cell lines, a network perspective. BMC systems biology. 2011;5:96. doi: 10.1186/1752-0509-5-96. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Zhang S, et al. GO-Bayes: Gene Ontology-based overrepresentation analysis using a Bayesian approach. Bioinformatics. 2010;26:905–911. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btq059. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Alterovitz G, et al. Ontology engineering. Nat Biotech. 2010;28:128–130. doi: 10.1038/nbt0210-128. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Merico D, et al. Enrichment Map: A Network-Based Method for Gene-Set Enrichment Visualization and Interpretation. PLoS One. 2010;5:e13984. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0013984. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Yaspan B, et al. Genetic analysis of biological pathway data through genomic randomization. Human Genetics. 2011;129:563–571. doi: 10.1007/s00439-011-0956-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Askland K, et al. Pathways-based analyses of whole-genome association study data in bipolar disorder reveal genes mediating ion channel activity and synaptic neurotransmission. Hum Genet. 2009;125:63–79. doi: 10.1007/s00439-008-0600-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Sawcer S, et al. Genetic risk and a primary role for cell-mediated immune mechanisms in multiple sclerosis. Nature. 2011;476:214–219. doi: 10.1038/nature10251. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Kapranov P, et al. Genome-wide transcription and the implications for genomic organization. Nat Rev Genet. 2007;8:413–423. doi: 10.1038/nrg2083. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Portin P. The elusive concept of the gene. Hereditas. 2009;146:112–117. doi: 10.1111/j.1601-5223.2009.02128.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Edwards YJ, et al. Identifying consensus disease pathways in Parkinson’s disease using an integrative systems biology approach. PLoS One. 2011;6:e16917. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0016917. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Marchini J, Howie B. Genotype imputation for genome-wide association studies. Nat Rev Genet. 2010;11:499–511. doi: 10.1038/nrg2796. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Holmans P, et al. Gene ontology analysis of GWA study data sets provides insights into the biology of bipolar disorder. Am J Hum Genet. 2009;85:13–24. doi: 10.1016/j.ajhg.2009.05.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.O’Dushlaine C, et al. The SNP ratio test: pathway analysis of genome-wide association datasets. Bioinformatics. 2009;25:2762–2763. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btp448. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Purcell S, et al. PLINK: a tool set for whole-genome association and population-based linkage analyses. Am J Hum Genet. 2007;81:559–575. doi: 10.1086/519795. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Liu JZ, et al. A Versatile Gene-Based Test for Genome-wide Association Studies. American Journal of Human Genetics. 2010;87:139–145. doi: 10.1016/j.ajhg.2010.06.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Huang H, et al. Gene-Based Tests of Association. PLoS genetics. 2011;7:e1002177. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1002177. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Gaudet MM, et al. Common genetic variants and modification of penetrance of BRCA2-associated breast cancer. PLoS genetics. 2010;6:e1001183. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1001183. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Goeman JJ, Bühlmann P. Analyzing gene expression data in terms of gene sets: methodological issues. Bioinformatics. 2007;23:980–987. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btm051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Fridley BL, et al. Self-contained gene-set analysis of expression data: an evaluation of existing and novel methods. PLoS One. 2010:5. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0012693. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Moskvina V, et al. Gene-wide analyses of genome-wide association data sets: evidence for multiple common risk alleles for schizophrenia and bipolar disorder and for overlap in genetic risk. Mol Psychiatry. 2009;14:252–260. doi: 10.1038/mp.2008.133. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Lambert JC, et al. Implication of the immune system in Alzheimer’s disease: evidence from genome-wide pathway analysis. Journal of Alzheimer’s disease : JAD. 2010;20:1107–1118. doi: 10.3233/JAD-2010-100018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Wang K, et al. Diverse genome-wide association studies associate the IL12/IL23 pathway with Crohn Disease. Am J Hum Genet. 2009;84:399–405. doi: 10.1016/j.ajhg.2009.01.026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Holden M, et al. GSEA-SNP: applying gene set enrichment analysis to SNP data from genome-wide association studies. Bioinformatics. 2008;24:2784–2785. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btn516. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Tintle N, et al. Comparing gene set analysis methods on single-nucleotide polymorphism data from Genetic Analysis Workshop 16. BMC proceedings. 2009;3:S96. doi: 10.1186/1753-6561-3-s7-s96. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Nam D, et al. GSA-SNP: a general approach for gene set analysis of polymorphisms. Nucleic Acids Research. 2010;38:W749–W754. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkq428. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Wang L, et al. Gene set analysis of genome-wide association studies: Methodological issues and perspectives. Genomics. 2011;98:1–8. doi: 10.1016/j.ygeno.2011.04.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Hung J-H, et al. Gene set enrichment analysis: performance evaluation and usage guidelines. Briefings in Bioinformatics. 2011 doi: 10.1093/bib/bbr049. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Kim SY, Volsky D. PAGE: Parametric Analysis of Gene Set Enrichment. BMC Bioinformatics. 2005;6:144. doi: 10.1186/1471-2105-6-144. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Berry MPR, et al. An interferon-inducible neutrophil-driven blood transcriptional signature in human tuberculosis. Nature. 2010;466:973–977. doi: 10.1038/nature09247. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Baranzini SE, et al. Genetic variation influences glutamate concentrations in brains of patients with multiple sclerosis. Brain. 2010;133:2603–2611. doi: 10.1093/brain/awq192. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Lee HM, et al. Abnormal networks of immune response-related molecules in bone marrow cells from patients with rheumatoid arthritis as revealed by DNA microarray analysis. Arthritis research & therapy. 2011;13:R89. doi: 10.1186/ar3364. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Pang H, et al. Pathway-based identification of SNPs predictive of survival. Eur J Hum Genet. 2011;19:704–709. doi: 10.1038/ejhg.2011.3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Gilman SR, et al. Rare de novo variants associated with autism implicate a large functional network of genes involved in formation and function of synapses. Neuron. 2011;70:898–907. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2011.05.021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Yang HC, Chen CW. Region-based and pathway-based QTL mapping using a p-value combination method. BMC proceedings. 2011;5:S43. doi: 10.1186/1753-6561-5-S9-S43. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.McLean CY, et al. GREAT improves functional interpretation of cis-regulatory regions. Nat Biotech. 2010;28:495–501. doi: 10.1038/nbt.1630. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Hong MG, et al. Strategies and issues in the detection of pathway enrichment in genome-wide association studies. Human Genetics. 2009;126:289–301. doi: 10.1007/s00439-009-0676-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Benjamini Y, Hochberg Y. Controlling the False Discovery Rate - a Practical and Powerful Approach to Multiple Testing. J Roy Stat Soc B Met. 1995;57:289–300. [Google Scholar]

- 65.Sabatti C. Avoiding False Discoveries in Association Studies. In: Collins AR, editor. Methods in Molecular Biology: Linkage Disequilibrium and Association Mapping. Humana Press; 2007. pp. 195–211. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Luo L, et al. Genome-wide gene and pathway analysis. Eur J Hum Genet. 2010;18:1045–1053. doi: 10.1038/ejhg.2010.62. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Bertram L, et al. Systematic meta-analyses of Alzheimer disease genetic association studies: the AlzGene database. Nat Genet. 2007;39:17–23. doi: 10.1038/ng1934. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Zhu J, et al. The UCSC Cancer Genomics Browser. Nat Meth. 2009;6:239–240. doi: 10.1038/nmeth0409-239. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Brown SDM, et al. The Functional Annotation of Mammalian Genomes: The Challenge of Phenotyping. Annual Review of Genetics. 2009;43:305–333. doi: 10.1146/annurev-genet-102108-134143. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Hu T, et al. Characterizing genetic interactions in human disease association studies using statistical epistasis networks. BMC Bioinformatics. 2011;12:364. doi: 10.1186/1471-2105-12-364. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Cowper-Sallari R, et al. Layers of epistasis: genome-wide regulatory networks and network approaches to genome-wide association studies. Wiley Interdisciplinary Reviews: Systems Biology and Medicine. 2011;3:513–526. doi: 10.1002/wsbm.132. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.McKinney BA, Pajewski NM. Six Degrees of Epistasis: Statistical Network Models for GWAS. Frontiers in genetics. 2011;2:109. doi: 10.3389/fgene.2011.00109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Bandyopadhyay S, et al. Rewiring of Genetic Networks in Response to DNA Damage. Science. 2010;330:1385–1389. doi: 10.1126/science.1195618. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Sun J, et al. Application of systems biology approach identifies and validates GRB2 as a risk gene for schizophrenia in the Irish Case Control Study of Schizophrenia (ICCSS) sample. Schizophrenia research. 2011;125:201–208. doi: 10.1016/j.schres.2010.12.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Edvardsson K, et al. Estrogen receptor beta induces antiinflammatory and antitumorigenic networks in colon cancer cells. Mol Endocrinol. 2011;25:969–979. doi: 10.1210/me.2010-0452. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Gui H, et al. Comparisons of seven algorithms for pathway analysis using the WTCCC Crohn’s Disease dataset. BMC Research Notes. 2011;4:386. doi: 10.1186/1756-0500-4-386. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Gorlov IP, et al. GWAS Meets Microarray: Are the Results of Genome-Wide Association Studies and Gene-Expression Profiling Consistent? Prostate Cancer as an Example. PLoS One. 2009;4:e6511. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0006511. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Myers AJ, et al. A survey of genetic human cortical gene expression. Nat Genet. 2007;39:1494–1499. doi: 10.1038/ng.2007.16. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Nicolae DL, et al. Trait-Associated SNPs Are More Likely to Be eQTLs: Annotation to Enhance Discovery from GWAS. PLoS genetics. 2010;6:e1000888. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1000888. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Liang WS, et al. Alzheimer’s disease is associated with reduced expression of energy metabolism genes in posterior cingulate neurons. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 2008;105:4441–4446. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0709259105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Le-Niculescu H, et al. Convergent functional genomics of genome-wide association data for bipolar disorder: comprehensive identification of candidate genes, pathways and mechanisms. Am J Med Genet B Neuropsychiatr Genet. 2009;150B:155–181. doi: 10.1002/ajmg.b.30887. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Ala-Korpela M, et al. Genome-wide association studies and systems biology: together at last. Trends in Genetics. 2011;27:493–498. doi: 10.1016/j.tig.2011.09.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Penrod NM, et al. Systems genetics for drug target discovery. Trends in pharmacological sciences. 2011;32:623–630. doi: 10.1016/j.tips.2011.07.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Jarvik J, Botstein D. A genetic method for determining the order of events in a biological pathway. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1973;70:2046–2050. doi: 10.1073/pnas.70.7.2046. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Marchion DC, et al. BAD phosphorylation determines ovarian cancer chemo-sensitivity and patient survival. Clinical Cancer Research. 2011 doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-11-0735. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Newman MEJ. Networks: an introduction. Oxford University Press; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 87.Price ND, Shmulevich I. Biochemical and statistical network models for systems biology. Current Opinion in Biotechnology. 2007;18:365–370. doi: 10.1016/j.copbio.2007.07.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Ghosh S, et al. Software for systems biology: from tools to integrated platforms. Nat Rev Genet. 2011;12:821–832. doi: 10.1038/nrg3096. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Thomas S, Bonchev D. A survey of current software for network analysis in molecular biology. Human genomics. 2010;4:353–360. doi: 10.1186/1479-7364-4-5-353. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Chen H, Sharp B. Content-rich biological network constructed by mining PubMed abstracts. BMC Bioinformatics. 2004;5:147. doi: 10.1186/1471-2105-5-147. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Medina I, et al. Gene set-based analysis of polymorphisms: finding pathways or biological processes associated to traits in genome-wide association studies. Nucleic Acids Res. 2009;37:W340–344. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkp481. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Raychaudhuri S, et al. Identifying relationships among genomic disease regions: predicting genes at pathogenic SNP associations and rare deletions. PLoS genetics. 2009;5:e1000534. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1000534. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Chen LS, et al. Insights into colon cancer etiology via a regularized approach to gene set analysis of GWAS data. Am J Hum Genet. 2010;86:860–871. doi: 10.1016/j.ajhg.2010.04.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Subramanian A, et al. Gene set enrichment analysis: a knowledge-based approach for interpreting genome-wide expression profiles. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2005;102:15545–15550. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0506580102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Segrè AV, et al. Common Inherited Variation in Mitochondrial Genes Is Not Enriched for Associations with Type 2 Diabetes or Related Glycemic Traits. PLoS genetics. 2010;6:e1001058. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1001058. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]