Abstract

Interactions of Toll-like receptors (TLR) with non-microbial factors plays a major role in the pathogenesis of early trauma-hemorrhagic shock (T/HS)-induced organ injury and inflammation. Thus, we tested the hypothesis that TLR4 mutant (TLR4mut) mice would be more resistant to T/HS-induced gut injury and neutrophil (PMN) priming than their wild-type (WT) littermates and found that both were significantly reduced in the TLR4mut mice. Additionally, the in vivo and ex vivo PMN priming effect of T/HS intestinal lymph observed in the WT mice was abrogated in TLR4mut mice as well the TRIFmut deficient mice and partially attenuated in Myd88-/- mice suggesting that TRIF activation played a more predominant role than MyD88 in T/HS lymph-induced PMN priming. PMN depletion studies showed that T/HS lymph-induced acute lung injury (ALI) was PMN-dependent, since lung injury was totally abrogated in PMN-depleted animals. Since the lymph samples were sterile and devoid of endotoxin or bacterial DNA, we investigated whether the effects of T/HS lymph was related to endogenous non-microbial TLR4 ligands. HMGB1, heat shock protein (Hsp)-70, Hsp27 and hyaluronic acid, since all have been implicated in ischemia-reperfusion-induced tissue injury. None of these ‘danger’ proteins appeared to be involved, since their levels were similar between the sham and shock lymph samples. In conclusion, TLR4 activation is important in T/HS-induced gut injury and in T/HS lymph-induced PMN priming and lung injury. However, the T/HS-associated effects of TLR4 on gut barrier dysfunction can be uncoupled from the T/HS lymph-associated effects of TLR4 on PMN priming.

Keywords: mesenteric lymph, shock, MODS, hemorrhage, danger model

INTRODUCTION

The danger model, originally proposed by Dr Matzinger (1) to explain paradoxes in the immune system response to foreign antigens, has helped unravel the mechanisms by which sterile tissue-inducing insults or inflammatory states lead to tissue damage. In essence, the danger model proposes that endogenous host-derived molecules from damaged cells and tissues activate the immune system to cause a systemic inflammatory response. These endogenous factors, termed alarmins or danger associated molecular pattern (DAMP) molecules interact with a number of host receptors including Toll-like receptors (TLR) and the receptors for advanced glycation products (2, 3). Activation of these receptors in turn results in the production of pro-inflammatory and tissue injurious mediators (2, 3). Although the exact source of the DAMPs generated during sterile inflammatory conditions remains to be fully defined, in conditions such as trauma-hemorrhagic shock (T/HS) or burn injury, TLR4 activation has been shown to be involved in the pathogenesis of acute lung injury and the induction of a systemic inflammatory state (4-6). Our previous work (7), plus the work of others (8-10), indicated that TLR4 deficiency, but not the absence of TLR2 resulted in resistance to acute lung injury in murine T/HS models. Likewise, our previous work has documented that acute lung injury after T/HS is dependent on gut injury and the presence of biologically active intestinal lymph (11-13), which are associated with neutrophil (PMN) priming (11). Since activated PMNs are a key factor in the pathogenesis of acute lung injury (14), we performed experiments to test the hypothesis that T/HS lymph activates PMNs through a TLR4-dependent mechanism and that these activated PMNs are necessary for the induction of T/HS lymph-induced lung injury. Our results support this hypothesis since TLR4 deficient mice were more resistant to T/HS-induced gut injury and PMN priming while PMN depletion abrogated lung injury in mice challenged with T/HS lymph. Furthermore, investigation of the relative roles of the two downstream TLR4 signaling pathways (MyD88 and TRIF) on PMN priming by T/HS lymph indicated that both pathways were involved, although the TRIF pathway appeared to be the predominant PMN priming pathway. Lastly, we investigated the potential role of a number of non-microbial TLR4 ligands generated at sites of tissue damage by measuring their levels in lymph and/or plasma.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Animals

Adult male non-castrated Yorkshire minipigs, weighing 25 to 35 kg were used in this study (Animal Biotech Industries). Male 10-12 week old outbred cesarean-derived (CD-1) mice, TLR4-mutated (C3H/HeJ) mice and their wild-type (WT) mice (C3H/HeOuJ), TRIF deficient and their wild type (C57BL/6J) littermates were obtained from The Jackson Laboratory. Mice on the C57BL/6J background with a specific deletion of the MyD88 gene (MyD88-/- mice) were kindly provided by Dr. Samuel J. Leibovich (UMDNJ-New Jersey Medical School, Newark, N.J). The generation and genotyping of Myd88-/-, Myd88+/- and Myd88 +/+ WT (C57BL/6J) was described previously (15). C3H/HeJ mice have a point mutation in the TLR4 gene (16) and C57BL/6J-Ticam1Lps2/J mice have a Lps mutation in the Trif/or Ticam-1 gene that inhibit TLR4- and TRIF-dependent signaling respectively. From herein, C3H/HeJ mice will be referred to as TLR4mut and C57BL/6J-Ticam1Lps2/J mice will be referred to as TRIFmut mice. The animals were maintained in accordance with the guidelines of the National Institutes of Health Guide for Care and Use of Laboratory Animals and the experiments were approved by the Animal Care and Use Committee of the University of Medicine and Dentistry of New Jersey.

Pig trauma-hemorrhagic shock (T/HS) and lymph collection model

Pigs underwent mesenteric lymph duct cannulation, followed by T/HS or trauma sham-shock (T/SS), as described previously (17). The T/HS model involved a laparotomy with mesenteric lymph duct cannulation and withdrawal of blood in a staged fashion to a MAP of 40 mm Hg. The MAP was maintained until the base deficit reached -5 or the total shock period reached 3 hours. Animals were then resuscitated in a staged fashion to a MAP of 80-100 mm Hg. T/SS animals underwent laparotomy with lymph duct cannulation and without blood withdrawal. Mesenteric lymph was collected in sterile tubes for 30 minutes before shock, during shock and on an hourly basis during the postshock period. The collected lymph specimens were centrifuged at 500 g for 20 minutes at 4°C to remove all cellular components, tested for sterility on MacConkey and blood agar plates and aliquots were stored at -80C until used. Previously, we published that these banked lymph samples did not contain measurable levels of bacteria DNA and were devoid of endotoxin, using the limulus lysate assay (limit of detection 0.06 endotoxin units) (7).

Rat T/HS and lymph collection model

Rats were subjected to T/HS or T/SS and their mesenteric lymph collected as previously described (12). The T/HS model consisted of a trauma component (neck and groin dissections for vascular catheter placement plus a laparotomy) and a shock component (90 min of shock to a MAP ~35 mm Hg) at the end of which the rats were resuscitated with their shed blood. The shed blood was collected into a heparin-wetted syringe (100 units/kg) and kept in this syringe at room temperature until it was re-infused. Lymph specimens were collected hourly. The collected lymph specimens were centrifuged at 500 g for 20 minutes at 4°C to remove all cellular components, tested for sterility on MacConkey and blood agar plates and the aliquots were stored at -80°C until used. Plasma from these animals which had lymph diversion (LDL) were frozen and saved for HMGB1 measurements.

Mouse T/HS model

Male mice were anesthetized with pentobarbital (60-80 mg/kg IP) and under strict asepsis, a 2.5-cm midline laparotomy was performed. Isoflurane was given if needed to maintain the surgical level of anesthesia. Blood was withdrawn from the jugular vein until a mean arterial pressure (MAP) between 35-40 mmHg was obtained and maintained for 60 min. After 60 min, the mice were resuscitated with their shed blood. The shed blood was collected into a heparin-wetted syringe (100 units/kg) and kept in this syringe at room temperature until it was re-infused. Animals subjected to T/SS underwent cannulation of the femoral artery and jugular vein followed by a laparotomy; however, no blood was withdrawn and the MAP was kept within normal limits. At 3 hr, after the end of shock or sham shock period, the mice were sacrificed. Depending on the experiment, samples were obtaining for assessing gut injury, lung injury and/or PMN priming.

Lymph infusion protocol

The protocols for lymph injection with pig and rat lymph were identical except for the volume of lymph injected. The lymph-injected mice underwent laparotomy as well as internal jugular vein cannulation. The laparotomy was closed after 15 minutes using two layers of 3.0 silk suture. WT, TLR4mut, Myd88-/- and TRIFmut mice were infused with T/HS or T/SS lymph from different pigs or rats. The lymph used for each mouse was collected from an individual pig or rat (pooled fractions collected during 1-3 hr post T/SS or T/HS). Pig T/HS or T/SS lymph was infused via the jugular catheter at a rate of 10 μL/g body weight per hour for 3 hours, while rat lymph was infused at a rate of 3.3 μl/g body weight per hour. At the end of the 3 hour lymph infusion period, the mice were euthanized and samples collected.

The rationale for the lymph volume infused was based on the actual amount of lymph produced by the pigs (μL/g/hr) subjected to T/HS or T/SS over the shock and resuscitation period which was approximately 10 μL/hr/g body weight (17) plus dose-response pilot studies of pig T/HS lymph documented that lung injury occurred with doses of pig lymph as low as 10 μL/hr/g body weight (data not shown). As previously reported, rat post-T/HS lymph production averaged about 3.3 μL/hr/g body weight and this dose of T/HS lymph was sufficient to cause lung injury in naive rats and mice (12) and consequently was used in this study.

PMN depletion model

PMNs were depleted by IP injection of 0.4 ml (1:10 in normal saline) of rabbit anti-Mmouse PMN antibody (AIA31140, Accurate Chemicals and Scientific Corp) at 48 hr and 24 hr prior to T/HS or T/SS lymph infusion, as recommended by the manufacturer's instructions. The same dosing regimen and schedule was used in control mice receiving normal rabbit serum. PMN depletion was confirmed by counting the number of circulating PMN in Wright-Giemsa stained peripheral blood smears from anti-PMN antibody-, normal rabbit serum- and non- treated mice in a blinded fashion.

Intestinal Permeability assay

Ileal permeability was measured in-vivo using flourescein dextran -4 (FD-4) (Sigma) as previously described (18). At the end of the experimental period, a repeat laparotomy was performed through the previous laparotomy incision. A loop of ileum was ligated 3 cm from the ileocecal valve and 20 cm of ileum was measured in a retrograde manner. At this point, the ileum was also ligated. Just distal to the proximal suture an enterotomy was made and the intestinal loop was flushed with 1 ml of normal saline following which the enterotomy was closed. Subsequently, 1 ml of FD-4 (25 mg/ml in 0.1 M PBS pH 7.2) was injected in a retrograde fashion into the lumen of the isolated bowel segment and the bowel was returned into the abdomen and the abdominal incision was closed using 4-0 silk. After 30 minutes, a portal vein blood sample was collected. The blood sample was then centrifuged at 3000 g at 4°C for 10 min. The blood samples, along with the FD-4 standards, were read in a Bio-Tek Instruments Flx800 Microplate Fluorescence Reader at an excitation of 485/20 and an emission of 528/20. Gut permeability was expressed as the amount of FD-4 found in portal vein plasma in ug/ml.

Intestinal villous injury

A segment of the terminal ileum was obtained and processed, cut and stained with toluidine blue as previously described (18). Morphologic evidence of gut injury was quantified in five random fields with 100 to 250 villi from each animal in a blinded fashion. The overall incidence of villous damage was expressed as a percentage where the number of injured villi was divided by the total number of villi counted.

PMN priming

To assess the in vivo effects of lymph injection or actual T/HS on PMN priming, a blood sample was obtained in a heparinized syringe from each animal at 3 hours after the end of the T/SS or T/HS shock or the lymph infusion period for the measurement of respiratory burst activity, as previously described (19). The whole blood samples were treated with RBC lysis buffer (1% PharM Lyse; BD Pharmingen) and incubated for 15 minutes at room temperature to remove the RBCs. The samples were then centrifuged at 25°C and washed twice with Hank's balanced salt solution and the supernatant was discarded. The resulting pellet was suspended in Hank's balanced salt solution at a concentration of 4 ×106 cells/ml. Dihydrorhodamine (15 ng/mL) was added to 100 μL of the sample and warmed to 37°C. PMA (0.4 μmol/L) was then added to stimulate the cells for 15 minutes at 37°C. The respiratory burst was measured by flow cytometry, where the PMNs were identified by forward and side scatter analysis. The data are expressed as the mean fluorescence index (MFI). To assess the effects of the various lymph samples on PMN priming in vitro, PMNs isolated from whole blood from naive mice were incubated with Pig T/HS or T/SS lymph (10% v/v) for 5 minutes. Following this incubation period, PMA-induced respiratory burst was measured as described above.

Evans blue dye (EBD) lung permeability assay

As previously described (7), using EBD as a permeability probe, lung permeability was measured at the end of the 3 hr of T/HS or T/SS lymph infusion period.

Myeloperoxidase (MPO) assay

Frozen lung tissue was homogenized and assayed for MPO activity as previously described (20). One unit of MPO activity represents the amount of enzyme that will reduce 1 mol/min of peroxide.

Western Blot Analysis for HMGB1

For measuring HMGB1 levels in lymph or plasma samples, lymph and plasma were first concentrated by ultrafiltration using Centricon-10 (Amicon). The retained fraction was resolved on 10-20% gradient SDS-PAGE gels, transferred onto a polyvinylidene difluoride immunoblot membrane and probed with previously characterized affinity purified anti-HMGB1 antibody as described in (21). Western blots were processed with the immune-Lite Chemiluminescent assay kit (Bio-Rad Laboratories). The limit of detection was 10 ng.

HSP70 and HSP27 assays

The presence of heat shock proteins, HSP70 and HSP27 in lymph samples were measured by Western blotting as we have previously described (22). Protein concentration in lymph samples was determined by the BCA method (Pierce). Total proteins (150 μg) and positive controls (recombinant HSP70 and HSP27, 1 μg) were separated by SDS-PAGE and transferred onto a nitrocellulose membrane (400 mA for 3 h). Membranes were blocked with 5% nonfat milk in Tris-buffered saline (TBS) pH 7.4 for 0.5 h at 25°C and incubated with primary antibodies SPA-810 (HSP70) or SPA-800 (HSP27) from StressGen (1:5,000 dilutions in TBS) for 16 h at 4°C. Membranes were rinsed twice with washing solution (0.2% Tween-20 in TBS pH 7.4) and incubated with HRP-conjugated secondary antibodies (1:25,000 in TBS) for 3 h at 4°C. Proteins were detected using the SuperSignal Chemiluminescent Detection Kit (Pierce). Limits of detection for HSP70 and HSP27 were in the range of 0.6-50 pg.

Hyaluronic acid assay

Hyaluronic acid levels in lymph and plasma samples were measured using an ELISA kit purchased from Corgenix Inc as per the manufacturer's recommendations. This assay is based on using hyaluronic acid binding protein as the capture molecule to bind hyaluronic acid in the sample (23). This ELISA accurately measures hyaluronic acid levels levels between 10 – 800 ng/mL

Statistics

Analysis of variance (ANOVA) with the post hoc Tukey-Kramer multiple comparison test was used for comparisons between groups, while t-test were used for comparison between two groups. Results are expressed as mean ± SEM. P values less than 0.05 were considered statistically significant.

RESULTS

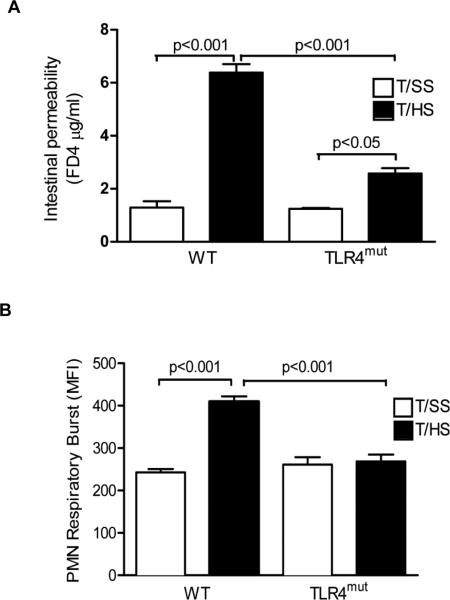

TLR4mut mice are resistant to T/HS-induced gut injury and PMN priming

To determine whether TLR4 is involved in T/HS-induced gut injury, we measured in vivo gut permeability using the permeability probe FD4. Gut permeability to FD 4 was increased about 6-fold in the WT mice subjected to T/HS as compared to the T/SS mice (Fig. 1A). In contrast to the WT mice, gut permeability was only modestly increased in the TLR4mut mice subjected to T/HS (Fig. 1A). Concomitant with increased T/HS-induced gut injury, the WT mice manifested an increase in PMN priming (Fig. 1B) as compared to the T/SS mice. The PMN priming effect of T/HS was totally abrogated in the TLR4mut mice (Fig. 1B).

Figure1. TLR4 deficiency attenuates T/HS-induced intestinal permeability and PMN priming.

WT and TLR4 mut mice were subjected to T/HS or T/SS for 60 min and 3 hr reperfusion. A, In vivo intestinal permeability was assessed by quantifying FD4 concentration (μg/ml) in the serum. In B, the effect of T/HS-induced PMN priming in lysed whole blood samples was measured in a respiratory burst flow cytometric-based assay. A and B, Data expressed as Mean ± SEM with n=4-6 mice per group.

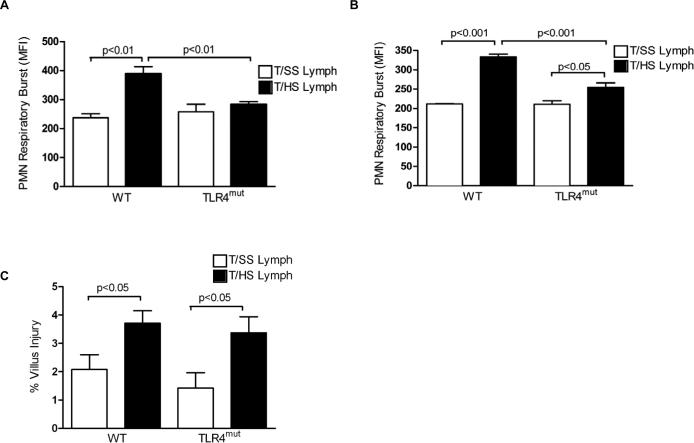

T/HS lymph primes PMNs from wild type mice, but not TLR4mut mice, for an augmented respiratory burst

Having previously documented that the in vitro incubation of naive PMNs with T/HS lymph results in priming (17), we repeated these studies using PMNs from TLR4mut mice and their WT litter mates. As expected, T/HS lymph, but not T/SS lymph primed PMNs from the WT mice for an augmented respiratory burst (Fig. 2A). In contrast, this priming effect was not observed in the PMNs from the TLR4mut mice (Fig. 2A). Since in vitro observations may not be replicated in more complex in vivo systems, we tested whether the TLR4mut mice would be resistant to priming when challenged with T/HS lymph in vivo. The injection of T/HS lymph, but not T/SS lymph primed circulating WT PMNs for an augmented respiratory burst (Fig. 2B). As was observed in the in vitro studies, T/HS lymph-induced PMN priming was blunted in the TLR4mut mice (Fig. 2B). Furthermore, the increase in PMN priming in the WT mice appeared to be directly related to the injection of the T/HS lymph and not due to T/HS lymph-induced gut injury, since the magnitude of gut injury in the T/HS lymph-injected groups was modest and similar between the two T/HS lymph-injected groups (Fig. 2C).

Figure 2. T/HS lymph increases PMN priming via TLR4.

A, Lysed whole blood samples from naïve WT or TLR4mut mice were incubated with pig T/HS or T/SS lymph (10%v/v) for 5 min. After PMA activation, the effect of T/HS or T/SS lymph on PMN priming was assessed in a respiratory burst assay. B, Lysed whole blood samples from WT and TLR4mut mice infused with porcine T/HS or T/SS lymph for 3 hr were tested for PMN priming in a respiratory burst assay. C, The percentage of villous injury in WT and TLR4mut mice infused with porcine T/HS lymph for 3 hr was quantified in hematoxylin and eosin stained distal ileal sections. By t-test (but not ANOVA) analysis, the T/HS lymph-injected mice had more gut injury that the T/SS lymph-injected mice. A-C, Data expressed as Mean ± SEM with n=4-7 mice per group.

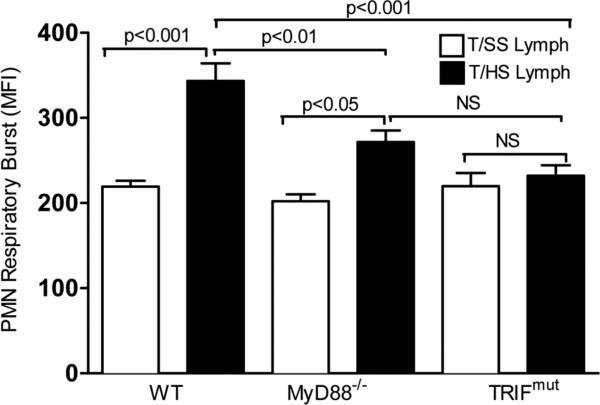

To investigate the TLR4-dependent molecular pathways activated by T/HS lymph, we repeated the in vivo lymph injection studies in MyD88-/- and TRIFmut mice, since MyD88 and TRIF are the two major downstream pathways activated by TLR4 ligands(5). These studies showed, that as expected, both the MyD88 and TRIF WT litter-mates had evidence of PMN priming after being challenged with T/HS lymph (Fig. 3). In the TRIFmut mice, T/HS lymph-induced PMN priming was completely abrogated while in the MyD88-/- mice the PMN priming effect was reduced but not completely abrogated (Fig. 3).

Figure 3. TRIF and Myd88 deficiency fully and partially prevent T/HS lymph-induced PMN priming.

Lysed whole blood samples were collected from WT, MyD88-/- and TRIFmut mice infused with porcine T/HS or T/SS lymph for 3 hr. PMN priming was measured in a respiratory burst assay. Data expressed as Mean ± SEM with n=5-8 mice per group.

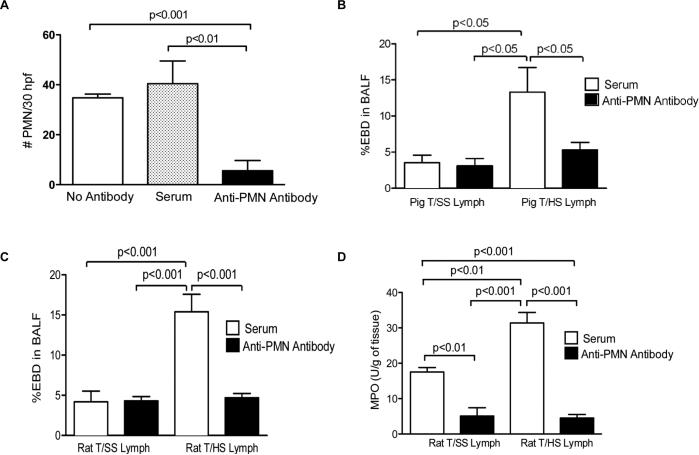

T/HS-lymph-induced acute lung injury is PMN-dependent

Since activation has been implicated in acute lung injury after trauma as well as other inflammatory states and T/HS lymph both primes PMNs and leads to lung injury (14), we tested the hypothesis that PMNs played a key role in T/HS lymph-induced acute lung injury. WT mice were injected with either rabbit anti-mouse PMN antibodies or normal rabbit serum prior to being challenged with T/HS or T/SS lymph samples. The anti-PMN antibody injected mice had greater than an 85% decrease in their circulating PMN count (Fig. 4A). As previously reported (7), porcine T/HS, but not T/SS, lymph led to acute lung injury as manifested by an increase in lung permeability to Evans blue dye (Fig. 4B). In contrast, T/HS lymph did not increase lung permeability in the PMN-depleted mice, since there was no difference in BALF Evans blue dye between the T/SS and T/HS lymph-injected groups receiving the anti- antiserum, as determined by one-way ANOVA; post hoc testing using the Tukey's multiple comparison test, 95% confidence levels. (Fig. 4B). To validate these porcine lymph injection results, the experiment was repeated in mice challenged with rat T/HS or T/SS lymph. Similar to what was observed with porcine T/HS lymph, PMN depletion fully protected against rat T/HS lymph-induced lung injury (Fig. 4C) indicating that T/HS lymph's lung injurious effects are not species-dependent. Also, as would be expected, T/HS lymph-induced PMN leukosequestration, as reflected in pulmonary myeloperoxidase levels, was reduced in the PMN-depleted mice (Fig. 4D). The degree of lung injury of the T/HS lymph-challenged mice pre-treated with normal rabbit serum was not influenced by the rabbit serum injections, since the extent of lung injury was the same as that of naive mice challenged with the lymph samples (data not shown).

Figure 4. PMN depletion attenuated T/HS lymph induced lung permeability and MPO levels.

CD1 mice were administered rabbit anti-mouse antibody or normal rabbit serum 48 and 24 hr before infusion with rat or porcine T/HS or T/SS lymph for 3 hr. A, The number of peripheral blood PMNs from mice administered anti- antibody, normal rabbit serum or no antibody was quantified in Wright-Giemsa stained blood smears using a hemacytometer. Data expressed as Mean ± SEM with n=10-29 mice per group. B, Lung permeability to EBD was performed in mice infused with porcine T/HS or T/SS lymph after the administration of anti- or serum control. % EBD in BALF refers to the percent of Evans blue dye in the bronchoalveolar lavage fluid. Data expressed as mean ± SE (n= 3-6 mice/group). C, Lung permeability to EBD and D, MPO levels (U/g) measured in lung homogenates was performed in mice infused with rat T/HS or T/SS lymph after the administration of anti- or serum control MPO levels (U/g) were measured in lung homogenates. C and D, Data expressed as mean ± SE (n= 3-6 mice/group).

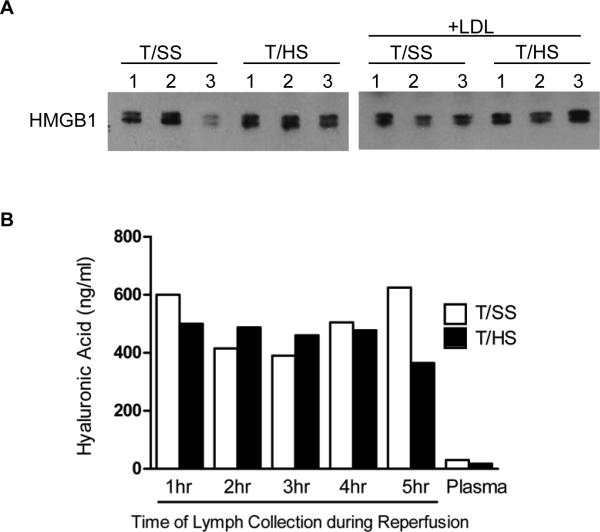

Investigation of potential non-microbial TLR4 ligands

Since we have previously, documented that the lymph samples tested were sterile, were devoid of endotoxin and did not contain bacterial DNA (7) , we investigated the role of several non-microbial TLR4 ligands. Since HMGB1 has been documented to increase after both sterile inflammatory and infectious insults (24, 25), we measured HMGB1 in both lymph and plasma samples. Minimal detectable levels of HMGB1 were found in the T/HS and T/SS lymph and plasma samples (data not shown). Since T/HS-induced gut injury or T/HS lymph could have resulted in an increase in plasma HMGB1 levels, we measured plasma HMGB1 levels in rats subjected to T/HS or T/SS with and without lymph diversion (LDL). LDL was utilized to examine the effect of T/HS on the plasma HMGB1 response in the absence of gut lymph, since LDL prevents T/HS lymph from reaching the systemic circulation. As shown, in Figure 5A, the HMGB1 levels did not differ among the groups, strongly suggesting that the PMN effects observed after actual T/HS or after the injection of T/HS lymph were not being modulated by HMGB1. Since certain heat shock proteins (Hsp) have been documented to be TLR4 ligands (26), we measured HSP70 and HSP27 levels in both pig and rat T/HS and T/SS samples. No detectable amounts were observed in either the T/HS or the T/SS samples (data not shown).

Figure 5. HMGB1 and hyaluronic acid are not endogenous TLR4 ligands in T/HS lymph.

A. Rat plasma HMGB1 levels in rats subjected to T/HS or T/SS with and without lymph diversion (LDL) was measured by western blot analysis (n= 3 rats per group). Each lane represents individual lymph. B, Hyaluronic acid levels in rat T/HS or T/SS lymph or plasma samples were measured using an ELISA (mean value of n=2 rats per group for each time point).

Since hyaluronic acid is both present in the ground substance of the intestinal interstitium and has been identified as a TLR4 ligand (26), we measured lymph and plasma hyaluronic acid levels. While the levels of hyaluronic acid were greatly increased in the T/HS lymph samples as compared to their plasma levels, the levels were similar to that observed in the T/SS lymph samples (Fig.5B).

DISCUSSION

Extensive clinical and preclinical studies have documented thr importance of PMNs in the pulmonary inflammatory response that characterizes the development of ALI (14, 27, 28). Progress has been made in clarifying the intracellular signaling pathways induced in these activated PMNs as well as the mechanisms by which these activated PMNs cause tissue injury (14). Numerous pro-inflammatory factors, including cytokines, lipid mediators, activated complement components as well as bacteria and their products have been demonstrated to prime and/or activate PMNs (14, 29) thereby, augmenting the magnitude of the inflammatory response after T/HS. However, their production, release and activation appear secondary to tissue injury or the shocked state and none appear to be the initial inducers of systemic PMN priming observed after T/HS. Since our earlier work has documented that non-microbial factors in T/HS lymph were capable of recreating lung injury via TLR4 activation (7), our current work extends these findings by demonstrating that factors in T/HS lymph prime PMNs via TLR4 activation.

One aspect of this study has focused on the gut lymph, since clinical studies have implicated the gut as the motor of ARDS and MODS (30) and preclinical studies have shown that gut ischemia-reperfusion induces PMN priming/activation and ALI (27, 31, 32). Additionally, our studies investigating the gut lymph hypothesis of MODS have shown that T/HS mesenteric (gut) lymph is necessary for PMN priming and ALI, since animals whose mesenteric lymph ducts have been ligated (prevents lymph from reaching the systemic circulation) do not develop ALI or PMN activation after T/HS or superior mesenteric artery occlusion (17). These in vivo studies were supported by ex vivo studies documenting that lymph collected from rats, pigs or primates subjected to T/HS (17, 33-35) as well as rats subjected to SMAO prime naive PMNs(36). Yet these T/HS lymph specimens were sterile and did not contain detectable levels of endotoxin or bacterial DNA (7) and their PMN-priming effects did not appear to be related to cytokines (37). On the other hand, tissue injury-induced non-microbial DAMPs have been documented to cause a sterile inflammatory response by activating the same germ-line pattern recognition receptors as microbial products (2, 3, 5, 26). Thus, we tested the hypotheses that TLR4 signaling controls PMN priming as well as pulmonary leukosequestration and that TLR4-mediated PMN priming plays an important role in the pathogenesis of ALI. This hypothesis is supported by emerging studies documenting a role for Toll-like receptors in T/HS-induced organ injury and systemic inflammation (5-10).

To test our hypotheses, we believed that it was important to utilize both actual T/HS as well as in vivo and ex vivo T/HS lymph injection models, since, in this way, gut-specific as well as lymph-specific effects could be investigated. That is, if the TLR4mut mice were resistant to gut injury, then biologically active T/HS lymph would not be generated. Thus, the failure to observe PMN priming could be related to the failure of the PMNs to be exposed to active T/HS lymph as opposed to being resistant to biologically active T/HS lymph priming. Thus, based on both the actual T/HS and the T/HS lymph injection results, one key set of conclusions are that T/HS-induced PMN priming is mediated by T/HS lymph, does not require gut injury, and occurs through a TLR4-dependent pathway which is mediated to a greater extent by the TRIF than the MyD88 signaling pathway. To our knowledge this is the first evidence explaining the mechanism and signaling pathways by which T/HS lymph leads to PMN priming. This conclusion was based on the following observations. 1) TLR4mut, but not WT mice, were resistant to actual T/HS-induced PMN priming in vivo and this was associated with abrogated gut injury (manifested as increased gut permeability); 2) in vitro exposure of naive whole blood to T/HS lymph primed PMNs from WT but not TLR4mut mice; 3) the in vivo injection of T/HS lymph primed WT but not TLR4mut PMNs; and 4) TRIFmut mice were totally resistant to in vivo PMN priming after being injected with T/HS lymph, while MyD88 -/- mice were only partly resistant to the in vivo PMN priming effects of T/HS lymph.

The notion that TLR4, as well as other members of the TLR family, can respond to endogenous non-microbial as well as microbial products has expanded the role of pattern recognition receptors beyond that of sensors of microbial invasion (1-3). This concept also helps explain the physiologic similarities between the host's septic response and the response to non-microbial inflammatory conditions such as shock-trauma. Our novel observations that T/HS lymph leads to lung injury (7) and now PMN priming through a TLR4-dependent mechanism are consistent with other studies showing that hemorrhagic shock-induced lung injury (10) and liver injury (8) are reduced in TLR4 deficient animals. Furthermore, it appears that these immune-activating and tissue-injurious effects of TLR4 activation may be a common denominator to diverse shock and tissue-injury states, since TLR4 deficient mice are resistant to the systemic consequences of other non-infectious models of injury, such as femoral fracture (38, 39) and thermal injury (40). Although there are multiple studies documenting the importance of TLR4 activation in the pathogenesis of organ injury in non-infectious conditions, the relative contributions of the TRIF and MyD88 pathways seem to vary based on the tissues tested and the nature of the insult. For example, MyD88 signaling was found to be crucial in the pathogenesis of infract size and PMN recruitment after myocardial ischemia (41), while the TRIF pathway was implicated in acid aspiration-induced lung injury (42). This variability in TLR4 signaling pathways is not unexpected since the specificity of the TLR4 response to various agonists is regulated by the selective recruitment of the MyD88/TIRAP and the TRIF/TRAM adaptor systems and their subsequent downstream signaling pathways. More work is needed to define the pathogenic role of TLR4 in various non-infectious models of ischemia-reperfusion injury as well as compare the TLR4-dependent mechanisms in the context of tissue/organ injured and the nature of the insult.

A second important finding of this work is that T/HS lymph-induced acute lung injury is PMN- dependent. This conclusion is based on the observations that PMN-depleted mice did not develop ALI after challenge with pig or rat T/HS lymph. These T/HS lymph results are consistent with earlier experimental studies showing that PMN depletion reduces lung injury in gut ischemia-reperfusion models (14, 43, 44). However, we cannot rule out the possibility that the attenuation of T/HS lymph-induced lung injury was solely dependent on the depletion of PMN. It is possible that the anti-PMN antibody used in our PMN depletion study affected other cell populations by cross-reacting with Gr-1+ -monocytes and plasmacytoid dendritic cells as reported in mice treated with anti-Gr-1 mAb RB6-8C5 (45) or that the depletion of PMN prevented the recruitment of other inflammatory cells into the lung. It is clear that other cell populations such as pulmonary endothelial cells and macrophages also contribute to the pathogenesis of ALI in a number of conditions. Our observation that PMN priming after T/HS or T/HS lymph is TLR4-dependent needs to be considered in the context of the other cell populations involved in ALI. Although the data is just emerging, it appears that cross-talk between TLR4 as well as TLR2 expressed on endothelial cells, macrophages as well as PMN work in concert to facilitate pulmonary PMN infiltration (10). Thus, it is likely that additional TLR-dependent relationships among various cell populations will be discovered as we continue to unravel the mechanisms of sterile inflammatory ALI. Nonetheless, the notion that the stressed gut is the initial source of factors that trigger the systemic inflammatory cascade leading to PMN priming and lung injury in conditions like hemorrhagic shock has a long history. In fact, it has been over a decade since Moore's group (27) proposed that in conditions associated with decreased splanchnic blood flow, such as shock, the post-ischemic splanchnic vascular bed is a site for priming circulating PMNs, which when activated provoke distant organ injury.

While it appears clear that T/HS intestinal lymph is a key factor in inducing early ALI, PMN priming and other pro-inflammatory and tissue injurious consequences of T/HS (11), the exact nature of the factors in lymph that are responsible for its in vivo effects remain difficult to determine. However, the putative factors do not appear to be microbial in nature, since the T/HS lymph samples were sterile and we had previously documented that aliquots of the stored porcine lymph samples used in this study did not contain detectable levels of endotoxin or bacterial DNA (7). Likewise, we have previously reported that rat lymph did not contain measurable levels of endotoxin and that its biologic activity was not abrogated by polymxin B (46). Since there are many microbes that may not grow in vitro and there are important biologically active nonendotoxin molecules, such as peptidoglycan, the fact that PCR analysis of these lymph specimens failed to identify bacterial DNA becomes important in concluding that the biologic effects of T/HS are not being mediated via microbial products. Likewise, the biologic activity of T/HS lymph does not appear to be cytokine-mediated or due to other potentially toxic factors such as xanthine oxidase (37, 46). On the other hand, T/HS lymph has been shown to contain biologically active non-microbial protein and lipid species, which remain to be fully defined (47-49). Since a number of endogenous TLR4 ligands, such as HMGB1, heat shock proteins and hyaluronic acid have been implicated in non-infectious models of tissue injury, we assayed whether these TLR4 ligands were increased in our T/HS lymph samples. The results of these studies did not identify any of these putative TLR4 agonists as being responsible for T/HS lymph's in vivo or in vitro biologic activity. Several studies have implicated HMGB1 as being involved in the pathogenesis of sterile inflammatory conditions leading to organ injury including trauma and shock with plasma elevations occurring in some studies as early as 2 hrs and in others at 6 or more hours after trauma-shock (24, 50, 51). Since our HMGB1 measurements were made at 3 hours after the end of the shock period, it is possible that our failure to find differences in HMGB1 levels between the T/HS and T/SS animals or lymph samples could be related to the early time point at which the samples were obtained. On the other hand, neither HMGB1 nor other well-described TLR4 protein agonists have been identified as being elevated in proteomic studies of mesenteric lymph. These included studies of mesenteric lymph from animals subjected to hemorrhagic shock (52-54) or pancreatitis (55) as well as lymph collected from human patients (56). Similarly, extracellular heat shock proteins, which has been implicated in the activation of the immune system (57), did not appears to play a role in the biological effect of lymph after T/HS. The inability to isolate and characterize the putative mediators in T/HS lymph is a major impediment to clarifying the pathogenesis of early shock-induced PMN priming and ALI. We believe solving this question will require complex fractionation and isolation studies that go beyond simple descriptive proteomic and lipidomic studies.

In conclusion, since ALI/ARDS is the earliest manifestation of organ failure/dysfunction after T/HS and its development appears to be an important prelude to the development of MODS, studies into its pathogenesis assume clinical as well as biologic importance. Our study documents a major role for T/HS lymph in mediating the effects of actual T/HS on PMN priming. Furthermore, we found that TLR4 activation was necessary for PMN priming and that the TRIF pathway appears to be more dominant than the MyD88 pathway in this process. Since primed/activated PMNs are important players in the pathogenesis of ALI, these results solve another piece to the puzzle of how a hemodynamic shock event is transduced into a systemic inflammatory event.

Acknowledgments

Supported by NIH grants P50-GM069790 (RF and EAD), T32-GM069330 (DCR and SUS) and RO1 GM 059841 (EAD)

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

REFERENCES

- 1.Matzinger P. The danger model: A renewed sense of self. Science. 2002;296:301–305. doi: 10.1126/science.1071059. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bianchi ME. Damps, pamps and alarmins: All we need to know about danger. J Leukoc Biol. 2007;81:1–5. doi: 10.1189/jlb.0306164. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kono H, Rock KL. How dying cells alert the immune system to danger. Nat Rev Immunol. 2008;8:279–289. doi: 10.1038/nri2215. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Paterson HM, Murphy TJ, Purcell EJ, Shelley O, Kriynovich SJ, Lien E, Mannick JA, Lederer JA. Injury primes the innate immune system for enhanced toll-like receptor reactivity. J Immunol. 2003;171:1473–1483. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.171.3.1473. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Mollen K, Anand R, Tsung A, Prince J, Levy R, Billiar T. Emerging paradigm: Toll-like receptor 4-sentinel for the detection of tissue damage. Shock. 2006;26:430–437. doi: 10.1097/01.shk.0000228797.41044.08. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Fan J, Kapus A, Marsden PA, Li YH, Oreopoulos G, Marshall JC, Frantz S, Kelly RA, Medzhitov R, Rotstein OD. Regulation of toll-like receptor 4 expression in the lung following hemorrhagic shock and lipopolysaccharide. J Immunol. 2002;168:5252–5259. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.168.10.5252. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Reino DC, Pisarenko V, Palange D, Doucet D, Bonitz RP, Lu Q, Colorado I, Sheth SU, Chandler B, Kannan KB, Ramanathan M, Xu DZ, Deitch EA, Feinman R. Trauma hemorrhagic shock-induced lung injury involves a gut-lymph-induced TLR4 pathway in mice. PLoS One. 2011;6:e14829. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0014829. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Prince JM, Levy RM, Yang R, Mollen KP, Fink MP, Vodovotz Y, Billiar TR. Toll-like receptor-4 signaling mediates hepatic injury and systemic inflammation in hemorrhagic shock. J Amer Coll Surg. 2006;202:407–417. doi: 10.1016/j.jamcollsurg.2005.11.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Chen C, Wang Y, Zhang Z, Wang C, Peng M. Toll-like receptor 4 regulates heme oxygenase-1 expression after hemorrhagic shock induced acute lung injury in mice: Requirement of p38 mitogen-activated protein kinase activation. Shock. 2009;31:486–492. doi: 10.1097/SHK.0b013e318188f7e1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Fan J. TLR cross-talk mechanism of hemorrhagic shock-primed pulmonary neutrophil infiltration. Open Crit Care Med J. 2010;2:1–8. doi: 10.2174/1874828700902010001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Deitch EA, Xu D, Lu Q. Gut lymph hypothesis of early shock and trauma-induced multiple organ dysfunction: A new look at gut origin of sepsis. J Org Dys. 2006;2:70–70. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Senthil M, Watkins A, Barlos D, Xu D, Lu Q, Abungu B, Caputo F, Feinman R, Deitch EA. Intravenous injection of trauma-hemorrhagic shock mesenteric lymph causes lung injury that is dependent upon activation of the inducible nitric oxide synthase pathway. Ann Surg. 2007;246:822–830. doi: 10.1097/SLA.0b013e3180caa3af. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Condon M, Senthil M, Xu D, Mason L, Sheth S, Spolarics Z, Feketova E, Machiedo G, Deitch EA. Intravenous injection of mesenteric lymph produced during hemorrhagic shock decreases RBC deformability in the rat. J Trauma. 2011;70:489–495. doi: 10.1097/TA.0b013e31820329d8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Abraham E. Neutrophils and acute lung injury. Crit Care Med. 2003;31:S195–S199. doi: 10.1097/01.CCM.0000057843.47705.E8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Adachi O, Kawai T, Takeda K, Matsumoto M, Tsutsui H, Sakagami M, Nakanishi K, Akira S. Targeted disruption of the MyD88 gene results in loss of IL-1- and IL-18-mediated function. Immunity. 1998;9:143–150. doi: 10.1016/s1074-7613(00)80596-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Poltorak A, He X, Smirnova I, Liu M-Y, Huffel CV, Du X, Birdwell D, Alejos E, Silva M, Galanos C, Freudenberg M, Ricciardi-Castagnoli P, Layton B, Beutler B. Defective LPS signaling in C3H/HeJ and C57BL/10ScCr mice: Mutations in Tlr4 gene. Science. 1998;282:2085–2088. doi: 10.1126/science.282.5396.2085. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Senthil M, Brown M, Xu D, Lu Q, Feketeova E, Deitch EA. Gut-lymph hypothesis of systemic inflammatory response syndrome/multiple-organ dysfunction syndrome: Validating studies in a porcine model. J Trauma. 2006;60:958–965. doi: 10.1097/01.ta.0000215500.00018.47. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Caputo F, Rupani B, Watkins A, Barlos D, Vega D, Senthil M, Deitch EA. Pancreatic duct ligation abrogates the trauma hemorrhage-induced gut barrier failure and the subsequent production of biologically active intestinal lymph. Shock. 2007;28:441–446. doi: 10.1097/shk.0b013e31804858f2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Doucet DR, Bonitz RP, Feinman R, Colorado I, Ramanathan M, Feketeova E, Condon M, Machiedo GW, Hauser CJ, Xu DZ, Deitch EA. Estrogenic hormone modulation abrogates changes in red blood cell deformability and neutrophil activation in trauma hemorrhagic shock. J Trauma. 2010;68:35–41. doi: 10.1097/TA.0b013e3181bbbddb. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Magnotti L, Upperman J, Xu D, Lu Q, Deitch EA. Gut-derived mesenteric lymph but not portal blood increases endothelial permeability and potentiates lung injury following hemorrhagic shock. Ann Surg. 1998;228:518–527. doi: 10.1097/00000658-199810000-00008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ulloa L, Ochani M, Yang H, Tanovic M, Halperin D, Yang R, Czura CJ, Fink MP, Tracey KJ. Ethyl pyruvate prevents lethality in mice with established lethal sepsis and systemic inflammation. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2002;99:12351–12356. doi: 10.1073/pnas.192222999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Vega V, Charles W, De Maio A. A new feature of the stress response: Increase in endocytosis mediated by hsp70. Cell Stress and Chaperones. 2010;15:517–527. doi: 10.1007/s12192-009-0165-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lindqvist U, Chichibu K, Delpech B, Goldberg RL, Knudson W, Poole AR, Laurent TC. Seven different assays of hyaluronan compared for clinical utility. Clinical Chemistry. 1992;38:127–132. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Wang H, Yang H, Czura C, Sama A, Tracey K. HMGB1 as a late mediator of lethal systemic inflammation. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2001;164:1768–1773. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm.164.10.2106117. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Wang H, Bloom O, Zhang M, Vishnubhakat JM, Ombrellino M, Che J, Frazier A, Yang H, Ivanova S, Borovikova L, Manogue KR, Faist E, Abraham E, Andersson J, Andersson U, Molina PE, Abumrad NN, Sama A, Tracey KJ. HMG-1 as a late mediator of endotoxin lethality in mice. Science. 1999;285:248–251. doi: 10.1126/science.285.5425.248. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Piccinini AM, Midwood KS. Dampening inflammation by modulating TLR signalling. Mediators of Inflammation. 2010:2010. doi: 10.1155/2010/672395. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Moore E, Moore F, Franciose R, Kim F, Biffl W, Banerjee A. The postischemic gut serves as a priming bed for circulating neutrophils that provoke multiple organ failure. J Trauma. 1994;37:881–887. doi: 10.1097/00005373-199412000-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Abraham E, Carmody A, Shenkar R, Arcaroli J. PMNs as early immunologic effectors in hemorrhage- or endotoxemia-induced acute lung injury. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol. 2000;279:L1137–L1145. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.2000.279.6.L1137. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Mantovani A, Cassatella MA, Costantini C, Jaillon S. Neutrophils in the activation and regulation of innate and adaptive immunity. Nat Rev Immunol. 2011;11:519–531. doi: 10.1038/nri3024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Leaphart CL, Tepas JJ., III The gut is a motor of organ system dysfunction. Surgery. 2007;141:563–569. doi: 10.1016/j.surg.2007.01.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Caruso JMFE, Dayal SD, Hauser CJ, Deitch EA. Factors in intestinal lymph after shock increase neutrophil adhesion molecule expression and pulmonary leukosequestration. J Trauma. 2003;55:727–733. doi: 10.1097/01.TA.0000037410.85492.77. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Zallen G, Moore E, Johnson J, Tamura D, Ciesla D, Silliman C. Posthemorrhagic shock mesenteric lymph primes circulating neutrophils and provokes lung injury. J Surg Res. 1999;83:83–88. doi: 10.1006/jsre.1999.5569. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Deitch EA, Forsythe R, Anjaria D, Livingston D, Lu Q, Xu D, Redl H. The role of lymph factors in lung injury, bone marrow suppression, and endothelial cell dysfunction in a primate model of trauma-hemorrhagic shock. Shock. 2004;22:221–228. doi: 10.1097/01.shk.0000133592.55400.83. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Deitch EA, Feketeova E, Adams J, Forsythe R, Xu D, Itagaki K, Redl H. Lymph from a primate baboon trauma hemorrhagic shock model activates human neutrophils. Shock. 2006;25:460–463. doi: 10.1097/01.shk.0000209551.88215.1e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Dayal S, Hauser C, Feketeova E, Fekete Z, Adams J, Lu Q, Xu D, Zaets S, Deitch EA. Shock mesenteric lymph-induced rat polymorphonuclear neutrophil activation and endothelial cell injury is mediated by aqueous factors. J Trauma. 2002;52:1048–1055. doi: 10.1097/00005373-200206000-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Deitch EA, Feketeova E, Lu Q, Zaets S, Berezina T, Machiedo G, Hauser C, Livingston D, Xu D. Resistance of the female, as opposed to the male, intestine to ischemia reperfusion-mediated injury is associated with increased resistance to gut-induced distant organ injury. Shock. 2008;29:78–83. doi: 10.1097/shk.0b013e318063e98a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Davidson MT, Deitch EA, Lu Q, Osband A, Feketeova E, Németh ZH, Haskó G, Xu DZ. A study of the biologic activity of trauma-hemorrhagic shock mesenteric lymph over time and the relative role of cytokines. Surgery. 2004;136:32–41. doi: 10.1016/j.surg.2003.12.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Levy RM, Prince JM, Yang R, Mollen KP, Liao H, Watson GA, Fink MP, Vodovotz Y, Billiar TR. Systemic inflammation and remote organ damage following bilateral femur fracture requires toll-like receptor 4. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol. 2006;291:R970–R976. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.00793.2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Mollen KP, Levy RM, Prince JM, Hoffman RA, Scott MJ, Kaczorowski DJ, Vallabhaneni R, Vodovotz Y, Billiar TR. Systemic inflammation and end organ damage following trauma involves functional TLR4 signaling in both bone marrow-derived cells and parenchymal cells. J Leukoc Biol. 2008;83:80–88. doi: 10.1189/jlb.0407201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Breslin J, Wu M, Guo M, Reynoso R, Yuan S. Toll-like receptor 4 contributes to microvascular inflammation and barrier dysfunction in thermal injury. Shock. 2008;29:197–216. doi: 10.1097/shk.0b013e3181454975. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Feng Y, Zhao H, Xu X, Buys ES, Raher MJ, Bopassa JC, Thibault H, Scherrer-Crosbie M, Schmidt U, Chao W. Innate immune adaptor MyD88 mediates PMN recruitment and myocardial injury after ischemia-reperfusion in mice. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2008;295:H1311–H1318. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00119.2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Imai Y, Kuba K, Neely GG, Yaghubian-Malhami R, Perkmann T, van Loo G, Ermolaeva M, Veldhuizen R, Leung YHC, Wang H, Liu H, Sun Y, Pasparakis M, Kopf M, Mech C, Bavari S, Peiris JSM, Slutsky AS, Akira S, Hultqvist M, Holmdahl R, Nicholls J, Jiang C, Binder CJ, Penninger JM. Identification of oxidative stress and Toll-like receptor 4 signaling as a key pathway of acute lung injury. Cell. 2008;133:235–249. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2008.02.043. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Simpson R, Alon R, Kobzik L, Valeri CR, Shepro D, Hechtman HB. Neutrophil and non-neutrophil-mediated injury in intestinal ischemia-reperfusion. Ann Surg. 1993;218:444–454. doi: 10.1097/00000658-199310000-00005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Hill J, Lindsay T, Valeri CR, Shepro D, Hechtman HB. A CD18 antibody prevents lung injury but not hypotension after intestinal ischemia-reperfusion. J Appl Physiol. 1993;74:659–664. doi: 10.1152/jappl.1993.74.2.659. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Daley JM, Thomay AA, Connolly MD, Reichner JS, Albina JE. Use of ly6g-specific monoclonal antibody to deplete neutrophils in mice. J Leukoc Biol. 2008;83:64–70. doi: 10.1189/jlb.0407247. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Adams J, Charles A, Xu DZ, Lu Q, Deitch EA. Factors larger than 100 kd in post-hemorrhagic shock mesenteric lymph are toxic for endothelial cells. Surgery. 2001;129:351–363. doi: 10.1067/msy.2001.111698. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Kaiser V, Sifri Z, Dikdan G, Berezina T, Zaets S, Lu Q, Xu D, Deitch EA. Trauma-hemorrhagic shock mesenteric lymph from rat contains a modified form of albumin that is implicated in endothelial cell toxicity. Shock. 2005;23:417–425. doi: 10.1097/01.shk.0000160524.14235.6c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Gonzalez R, Moore E, Biffl W, Ciesla D, Silliman C. The lipid fraction of post-hemorrhagic shock mesenteric lymph (PHSML) inhibits neutrophil apoptosis and enhances cytotoxic potential. Shock. 2002;14:404–448. doi: 10.1097/00024382-200014030-00028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Deitch EA, Qin X, Sheth S, Tiesi G, Palange D, Dong W, Lu Q, Xu D, Feketeova E, Feinman R. Anticoagulants influence the in vitro activity and composition of shock lymph but not its in vivo activity. Shock. 2011;36:177–183. doi: 10.1097/SHK.0b013e3182205c30. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Cai B, Deitch EA, Grande D, Ulloa L. Anti-inflammatory resuscitation improves survival in hemorrhage with trauma. J Trauma. 2009;66:1632–1640. doi: 10.1097/TA.0b013e3181a5b179. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Peltz E, Moore E, Eckels P, Damle S, Tsuruta Y, Johnson J, Sauaia A, Silliman C, Banerjee A, Abraham E. HMGB1 is markedly elevated within 6 hours of mechanical trauma in humans. Shock. 2009;32:17–22. doi: 10.1097/shk.0b013e3181997173. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Peltz ED, Moore EE, Zurawel AA, Jordan JR, Damle SS, Redzic JS, Masuno T, Eun J, Hansen KC, Banerjee A. Proteome and system ontology of hemorrhagic shock: Exploring early constitutive changes in postshock mesenteric lymph. Surgery. 2009;146:347–357. doi: 10.1016/j.surg.2009.02.022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Fang J, Shih L, Yuan K, Fang K, Hwang T, Hsieh S. Proteomic analysis of post-hemorrhagic shock mesenteric lymph. Shock. 2010;34:291–298. doi: 10.1097/SHK.0b013e3181ceef5e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Mittal A, Middleditch M, Ruggiero K, Loveday B, Delahunt B, Jüllig M, Cooper G, Windsor J, Phillips A. Changes in the mesenteric lymph proteome induced by hemorrhagic shock. Shock. 2010;34:140–149. doi: 10.1097/SHK.0b013e3181cd8631. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Mittal A, Phillips A, Middleditch M, Ruggiero K, Loveday B, Delahunt B, Cooper G, Windsor J. The proteome of mesenteric lymph during acute pancreatitis and implications for treatment. JOP. 2009;10:130–142. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Dzieciatkowska M, Wohlauer M, Moore E, Damle S, Peltz E, Campsen J, Kelher M, Silliman C, Banerjee A, Hansen K. Proteomic analysis of human mesenteric lymph. Shock. 2011;35:331–338. doi: 10.1097/SHK.0b013e318206f654. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.De Maio A. Extracellular heat shock proteins, cellular export vesicles, and the stress observation system: A form of communication during injury, infection, and cell damage. Cell Stress and Chaperones. 2011;16:235–249. doi: 10.1007/s12192-010-0236-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]