Abstract

MTF-1 is a sequence-specific DNA binding protein that activates the transcription of metal responsive genes. The extent of activation is dependent on the nature of the metal challenge. Here we identify separate regions within the Drosophila MTF-1 (dMTF-1) protein that are required for efficient copper- versus cadmium-induced transcription. dMTF-1 contains a number of potential metal binding regions that might allow metal discrimination including a DNA binding domain containing six zinc fingers and a highly conserved cysteine-rich C-terminus. We find that four of the zinc fingers in the DNA binding domain are essential for function but the DNA binding domain does not contribute to the metal discrimination by dMTF-1. We find that the conserved C-terminus of the cysteine-rich domain provides cadmium specificity while copper specificity maps to the previously described copper-binding region (Chen et. al., 2008). In addition, both metal specific domains are autorepressive in the absence of metal and contribute to the low level of basal transcription from metal inducible promoters.

Keywords: MTF-1, transcription, coactivator, metal, conformation, metallothionein

1. INTRODUCTION

Metal-responsive element-binding transcription factor-1 (MTF-1) is a sequence specific DNA binding protein that is conserved from insects to mammals. It binds metal response elements (MREs) in the promoter region of metal inducible genes to control metal responsive transcription activation and influence metal homeostasis. MTF-1 is an example of a tunable transcription factor. The amount of transcriptional activation, even for the same gene, depends on the nature of the signal.

Transition metals such as iron, zinc, and copper are essential nutrients and therefore transition metal homeostasis is an important aspect of cellular function. Conditions of either abnormally high or abnormally low concentrations of essential transition metals are deleterious to the cell[1, 2]. The cell must maintain the concentration of these metals within a window that supports efficient metabolic function but also protect against the damaging effects of high concentrations of these metals. In addition, non-essential transition metals such as cadmium and mercury, that play no metabolic role, must be kept in check to prevent toxicity[3]. One way a normal cell regulates transition metal concentrations is to tightly control genes involved in metal mobilization and storage, such as the metallothioneins. A large component of this regulation occurs at the level of transcription of the metallothionein genes and is dependent on the action of MTF-1[4–6].

In Drosophila, the system used in this work, there are five metallothionein genes (Mtn): MtnA, MtnB, MtnC, MtnD and MtnE [2, 7–9]. The five genes are differentially regulated in response to different metals. In Drosophila cells exposed to a high level of copper, MTF-1 activates transcription of MtnA to such a high level that the MtnA transcript becomes one of the most abundant transcripts in the cell; activation by cadmium is much less efficient indicating that the cell somehow differentiates between metal challenges and responds appropriately [10, 11]. The MtnB gene is less responsive to copper than MtnA but is highly induced when cells are challenged with cadmium[7, 12, 13]. This same type of metal specific induction of metallothioneins is also observed in mammalian cells[14–16].

The DNA binding domain of MTF-1 contains six zinc fingers with varying affinities for zinc[17, 18]. It has been proposed that in the absence of excess metal, only the high affinity zinc fingers contain zinc and MTF-1 is not competent to bind DNA. Upon exposure of the cell to metal, the excess metal displaces zinc from a metallothionein/zinc complex. The released zinc binds the low affinity zinc fingers on MTF-1, allowing nuclear translocation, DNA binding, and subsequent metal-induced transcription of target genes[19, 20].

Several observations are inconsistent with this hypothesis, however. First, although all of the Drosophila metallothionein genes require MTF-1, the response of the individual genes to transition metals is not uniform[7, 12, 13]. Second, MTF-1 is required for not only the stimulated expression but also the basal level of metallothionein expression in the absence of excess metal[21]. Third, MTF-1 activates transcription of some genes under conditions of low exogenous metal[10, 16, 21–23]. Finally, MTF-1 is bound to some promoters but does not activate the genes in the absence of metals[11]. These data are more consistent with a model of MTF-1 acting as a metal sensor to control transcription in a metal specific manner. In this study, we investigated the idea that structural changes in MTF-1 could account for the differential metal response. We find that distinct regions of Drosophila MTF-1 (dMTF-1) are required for metal specific transcriptional activation.

2. RESULTS

2.1 dMTF-1 has multiple metal sensing domains

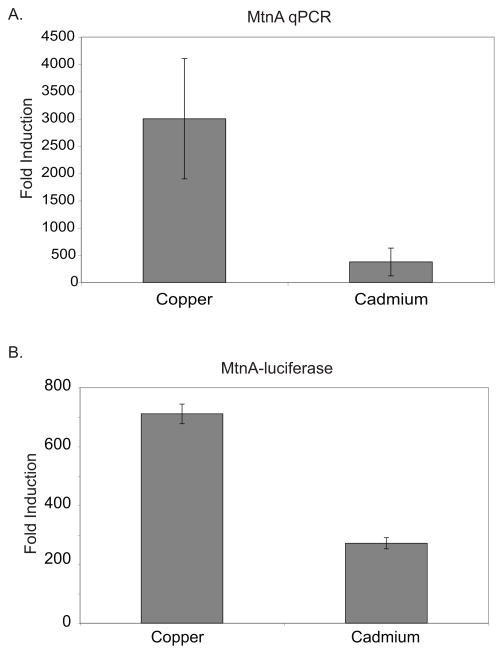

We investigated copper and cadmium induced transcription of MtnA in cultured Drosophila cells to study metal specific activation by MTF-1. The metal concentrations used here, 500 micromolar copper and 50 micromolar cadmium, were identical to concentrations used to show the differential metal response of MtnA in the fly[7] and were chosen based on preliminary experiments that indicated these concentrations lead to ½ maximal activation of the endogenous MtnA promoter. This provides the best prospect to identify changes that both increase and decrease activity of MTF-1. A subclone of Schneider line 2 cells (S2C1) were challenged with either copper or cadmium overnight and MtnA mRNA levels were quantitated by RT-qPCR. MtnA expression was induced approximately 3000-fold by copper while cadmium induction was approximately 300-fold (figure 1A). The difference in MtnA mRNA levels illustrates the differential metal response mediated by dMTF-1. We wished to recapitulate this differential metal response using an easily assayed reporter system that is compatible with mutagenesis studies. We transiently transfected a firefly luciferase reporter construct whose expression was driven by the native MtnA promoter[11], challenged the cells with copper or cadmium for four hours and measured MtnA-driven firefly luciferase levels (figure 1B). MtnA-luciferase activity was normalized to an Actin 5C promoter driving expression of renilla luciferase in all cases. MtnA activity was induced by copper approximately 700-fold. Cadmium induction was less than half that of copper. Both systems clearly illustrate that MtnA responds in a metal specific manner to copper and cadmium consistent with studies in the fly[7, 12]. Thus our transient transfection assay of the MtnA reporter construct is a good model for studying metal specificity.

Figure 1.

Metal induction of MtnA. (A) RT-qPCR analysis of copper and cadmium induced expression of MtnA in S2 cells. MtnA is normalized to RP49 and reported as fold induction (metal induced/untreated). (B) Metal induced expression of transiently transfected MtnA-firefly luciferase reporter by endogenous MTF-1 in S2 cells. Cells were induced for four hours by the addition of copper or cadmium and luciferase activity was assayed. Firefly signal was normalized to renilla signal and reported as fold induction (metal treated/untreated).

2.2 Transcription activation by mutants of known metal binding regions of dMTF-1

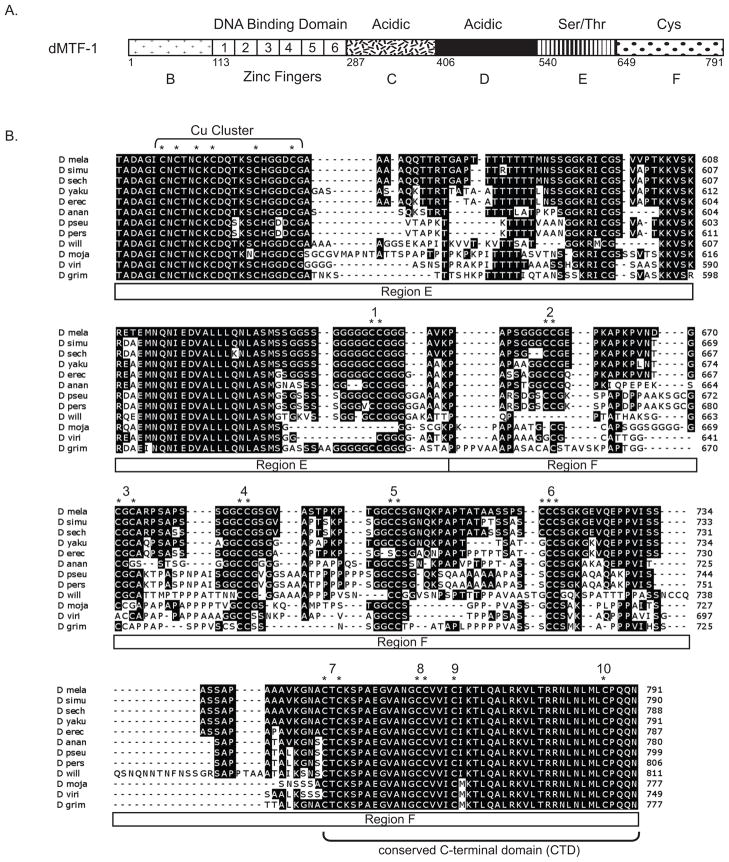

Analysis of the primary structure of dMTF-1, by comparison of Drosophila melanogaster MTF-1 with Drosophila psuedoobscura, human and mouse MTF-1, reveals a protein containing an amino-terminal region with 6 C2H2 zinc fingers (F1–F6), representing the DNA binding domain, and a carboxy–terminal region that contains a complex activation domain[6, 24] (figure 2A). The carboxy–terminus is the least conserved region of the polypeptide, but using several conserved residues as anchors, we subdivided the activation domain into 4 regions. Similar to the mouse and human homologues, the Drosophila melanogaster MTF-1 carboxy-terminus contains regions rich in acidic residues (regions C and D, amino acids 287–405 and 406–539, respectively), and serine/threonine residues (region E, amino acids 540–648)[4, 25]. In addition, dMTF-1 contains a cysteine-rich C-terminal region (region F, amino acids 649–791) not conserved in either human or mouse MTF-1. A comparison of 12 sequenced Drosophila species reveals that the cysteine residues in region F are highly conserved and the distal C-terminal domain (CTD) of region F is absolutely conserved across nine of the 12 species (figure 2B).

Figure 2.

Domains and alignment of dMTF-1. (A) Domain structure of dMTF-1. dMTF-1 can be subdivided into Regions B, C, D, E, F, and the DNA-binding domain composed of zinc fingers F1–F6. (B) Alignment of Regions E–F. dMTF-1 sequences used in the alignment were from the following species: D mela, Drosophila melanogaster; D simu, Drosophila simulans; D sech, Drosophila sechellia; D yaku, Drosophila yakuba; D erec, Drosophila erecta; D anan, Drosophila ananassae; D pseu, Drosophila pseudoobscura; D pers, Drosophila persimilis; D will, Drosophila willistoni; D moja, Drosophila mojavensis; D viri, Drosophila virilis; D grim, Drosophila grimshawi. Cysteines mutated to serine in dMTF-1 mutant constructs are indicated by asterisks.

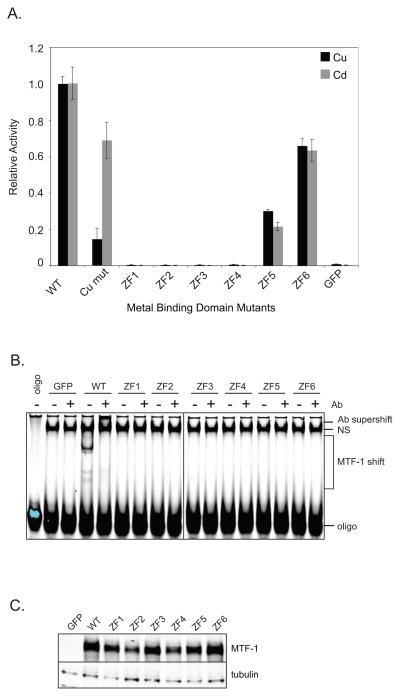

One way dMTF-1 could act as a primary metal sensor is to directly interact with transition metals via metal-liganding residues. In support of this idea, six cysteine residues (clustered in amino acids 547–565) in dMTF-1 were previously shown to function as a copper binding cluster and are required for copper activated transcription of MtnA in the fly[26]. To determine if the differential metal response of MtnA is dependent on this metal binding region, we created a copper cluster mutant by changing the cysteine residues shown to bind copper to serine. We tested this construct in our transient transfection assay to evaluate its response to both copper and cadmium, as only copper response was reported by Chen et. al.[26]. To prevent interference from endogenous dMTF-1 we first knocked down endogenous dMTF-1 using dsRNA directed against the 5′ UTR of the genomic transcript. This allowed us to express a modified dMTF-1 cDNA that is immune to the RNAi response. Under the knockdown conditions, we observe no metal dependent activation upon copper/cadmium treatment indicating that endogenous dMTF-1 was effectively depleted (figure 3A). Interestingly, we find that the copper cluster mutant retains significant transcriptional activity (70%) in the presence of cadmium while displaying a severe defect in the presence of copper (14%) on MtnA demonstrating that the copper-binding region is less important for the cadmium response (figure 3A).

Figure 3.

Transcription activation in mutants of known metal binding regions of dMTF-1. (A)MTF-1 expression vectors for WT dMTF-1 (WT), zinc finger mutants (ZF1–ZF6), and the copper cluster mutant (Cu mut) were tested for metal specific activation of MtnA. Endogenous dMTF-1 was removed by RNAi treatment and mutant dMTF-1 constructs were transiently transfected in triplicate into S2 cells with the metal inducible reporter pMtnA-Luc and a constitutively active transfection control, pMA-Ren. Transcription was induced by the addition of copper or cadmium and luciferase activity was assayed. Firefly/renilla ratios were calculated and reported as activity relative to WT; copper-treated mutants were normalized to copper-treated WT and cadmium-treated mutants were normalized to cadmium-treated WT. Transfection of GFP (no MTF-1) shows effectiveness of RNAi knock down of endogenous dMTF-1. Black bars, copper; gray bars, cadmium. (B) EMSA analysis of WT dMTF-1 and zinc finger mutants. dMTF-1 bound MRE complexes were supershifted with anti-FLAG monoclonal antibody. NS, nonspecific band. (C) Western blot analysis of transfected MTF-1 WT and zinc finger mutant expression vectors. Blot was probed with anti-MTF-1 polyclonal sera and anti-tubulin monoclonal sera for relative expression levels.

Another potential domain involved in metal sensing by MTF-1 is the zinc finger DNA binding domain. Six zinc finger mutants were tested, each containing histidine to alanine mutations in one of the six zinc fingers. Mutants of zinc fingers 1 through 4 have no detectable transcriptional activity at MtnA (figure 3A). However mutants of zinc fingers 5 and 6 exhibited approximately 25 and 60 percent activity of wild type MTF-1, respectively. No significant difference in activity was observed for copper and cadmium. These data are similar to previous experiments using mouse MTF-1 where a deletion mutant of zinc finger 1 was transcriptionally inactive but a deletion mutant of zinc fingers 5 and 6 retained partial activity [27]. The current results indicate that in Drosophila, zinc fingers 1–4 are critical for MTF-1 function while zinc finger 5 and 6 are somewhat dispensable.

All six zinc finger mutants were tested for nuclear localization and none were excluded from the nucleus (data not shown). However, all of the mutants are defective for DNA binding in electrophoretic mobility shift assays (EMSA) including mutants 5 and 6 which retained partial transcriptional activity in vivo (figure 3B). This discrepancy reflects the stringency of the in vitro binding assay. Detection in the EMSA likely requires very stable binding of MTF-1. The residual transcriptional activity of these mutants indicates that some transcription activation can occur with a transient interaction of MTF-1 with the promoter and does not require stable binding. In any case, none of the zinc finger mutants exhibited a differential metal response to either copper or cadmium indicating that the zinc finger domain is not involved in metal discrimination.

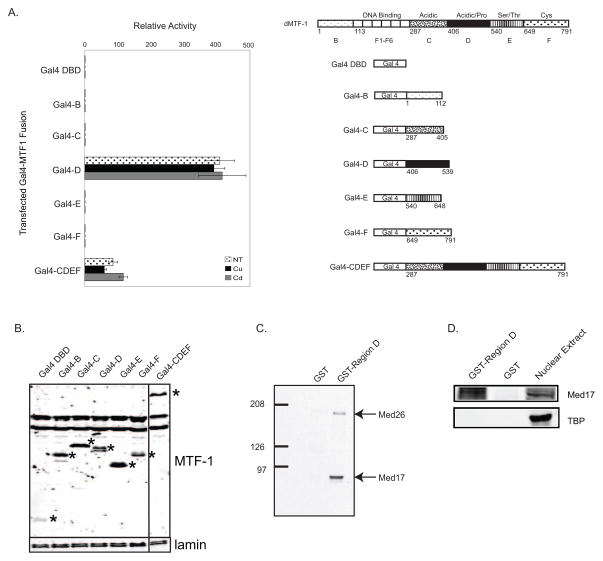

2.3 Mapping the Drosophila melanogaster MTF-1 activation domain

To evaluate the activation potential and possible metal specificity of the different regions within dMTF-1, we attached each region to the DNA binding domain from the Saccharomyces cerevisiae Gal4 protein (aa1–94). This allowed us to assay the activation potential of each piece in cultured Drosophila cells by co-transfecting a synthetic reporter containing three Gal4 binding sites and the Drosophila Rho core promoter driving expression of the firefly luciferase gene. Using this assay we identified the acidic region D as the strongest individual activation domain of dMTF-1 (Figure 4A). However, activation by region D showed no metal-dependent response for copper or cadmium. A fusion of the entire dMTF-1 activation domain (CDEF) is transcriptionally active but displays a four-fold reduction in activity compared to region D alone.

Figure 4.

Region D is the dMTF-1 activation domain and interacts with Mediator. (A) Heterologous promoter assay. Gal4 DBD-MTF-1 constructs were transiently transfected in triplicate into S2 cells with reporters pRho-Luc and pMA-Ren. Firefly/renilla activity for each metal-treated mutant was normalized to the activity of the Gal4 DNA binding domain treated with the same metal. Spotted bars, no treatment; black bars, copper induction; gray bars, cadmium induction. (B) Western blot analysis of transfected MTF-1 expression vectors. Blot was probed with anti-FLAG monoclonal sera and anti-nuclear lamin monoclonal sera for relative expression levels. Gal4-fusion proteins are indicated by *. (C) GST pulldown. GST-region D fusion protein was incubated with Drosophila embryo nuclear extract. Protein complexes were purified by glutathione affinity chromatography and interactors identified by immunoblotting for Mediator subunits Med26 and Med17. (D) GST pulldown probed for interaction with Med17 and TBP.

Previous work on dMTF-1 indicates that the conserved Mediator complex is an important co-activator for dMTF-1[11]. Because region D is the MTF-1 transactivation domain, we tested for interactions between region D and Mediator using a GST-region D fusion protein. This fusion protein was immobilized on glutathione resin and a Drosophila embryo nuclear extract was passed over the resin. Immobilized GST lacking region D was used as a negative control. The resins were washed and then the bound proteins were eluted with glutathione. Proteins eluting from the columns were analyzed by immunoblot to detect the MED26 and MED17 components of the Drosophila Mediator complex as indicators of an interaction with the complex (figure 4C). These components of the Mediator complex were detected in the GST-D fusion pulldown but not with GST alone indicating that this region is capable of interacting with Mediator. To verify that the Mediator interaction was specific and not simply an indirect interaction with the general preinitiation complex, we blotted for TBP in an independent experiment. MED17 and TBP were both detected in nuclear extract, MED17 bound to GST-region D but not with GST alone, but no interaction with TBP was observed for either region D or GST alone (figure 4D).

2.4 Identification of an inhibitory region in dMTF-1

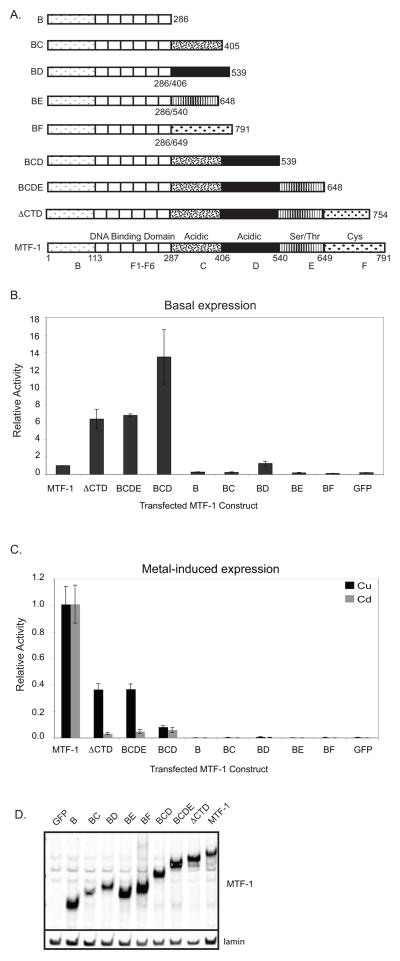

Our RNAi based system for depleting endogenous dMTF-1 allowed us to evaluate the individual regions of dMTF-1 for activation potential on the MtnA promoter. Individual regions of dMTF-1 (or subsets) were fused to amino acids 1–286 of dMTF-1 including the zinc finger DNA binding domain. Each fusion was tested for their ability to activate transcription of the MtnA reporter in the transient transfection assay. We first evaluated basal transcription (no excess metal) from the native promoter which is known to be dependent on MTF-1 (figure 5B)[21]. Region D (BD) is sufficient for uninduced levels of transcription whereas none of the other individual domains are functional, consistent with the previous results using the Gal4 system. Surprisingly, C-terminal truncations of dMTF-1 derepress transcription of MtnA. Deletion of either the CTD (ΔCTD) or region F (BCDE) increases transcription approximately 6-fold while deletion of both regions E and F increases transcription 13-fold. These data are consistent with the results from the Gal4 fusions where Gal4-CDEF showed a four-fold decrease in activity compared to region D alone. This derepression indicates that in the absence of any exogenous metal, the C-terminus of dMTF-1 is auto-inhibitory at least at the MtnA promoter.

Figure 5.

Transcriptional activation potential of dMTF-1 domains on MtnA. (A) Structure of MTF-1 mutants, (B) basal expression of MtnA and (C) metal-induced activation of MtnA. dMTF-1 domains were fused to the dMTF-1 DNA binding domain and transiently transfected in triplicate into S2 cells with reporters pMtnA-Luc and pMA-Ren. Metallothionein transcription was induced by the addition of copper or cadmium and luciferase activity was assayed. Firefly/renilla activity for each metal-treated mutant was normalized to wild type MTF-1 treated with the same metal and reported as relative activity. Transfection of GFP (no MTF-1) shows effectiveness of RNAi knock down of endogenous dMTF-1. (D) Western blot analysis of transfected MTF-1 expression vectors. Blot was probed with anti-MTF-1 polyclonal sera and anti-nuclear lamin monoclonal sera for relative expression levels.

Next we evaluated metal-induced transcription of MtnA by individual domains. In contrast to the Gal4 fusion experiments, only full-length dMTF-1 is capable of fully stimulating metal-induced transcription from the native metallothionein promoter (figure 5C). Region D (BD) is incapable of stimulating transcription although BCD displayed approximately 10 percent activity compared to full length. Addition of region E (BCDE) partially restored copper responsiveness but not cadmium responsiveness consistent with the presence of the copper binding cluster within region E. Interestingly, deletion of only the conserved C-terminal domain of region F (ΔCTD) was identical to the full deletion of region F indicating that region F is critical for cadmium induction and the CTD is absolutely required for this response.

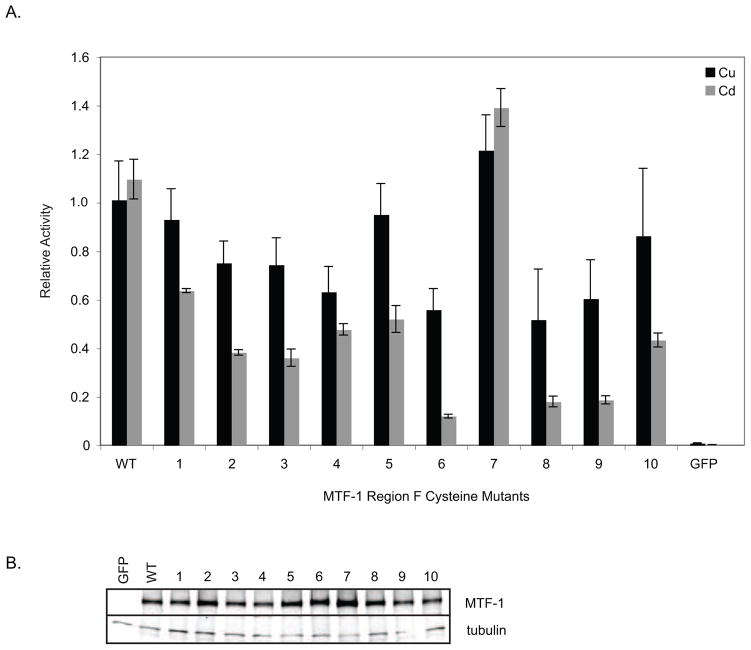

2.5 Cysteine residues within the C-terminal domain of dMTF-1 are required for cadmium specific activation

Because deletion of cysteine-rich region F abolished cadmium-induced transcription, we mutated possible metal-liganding cysteine residues within region F and tested a panel of ten mutants for their ability to activate transcription in the presence of copper or cadmium (figure 6A). Ten mutants encompassing seventeen cysteine residues in region F and two residues at the C-terminus of region E were constructed with cysteine to serine mutations. Cysteines were changed either singly or multiply mutated for closely space residues (see figure 2B for mutations). Nine out of the ten mutants display a cadmium specific defect (P-value <0.001). Mutant 9 is of particular interest because mutation of a single conserved cysteine (amino acid 766) within the CTD results in a phenotype nearly identical to the copper cluster mutant but with the opposite metal specificity i.e. severe cadmium defect but modest copper defect (figure 7A). These data indicate that separate domains modulate the metal specific activation of MtnA by dMTF-1 and that the copper cluster in region E confers copper specificity while cadmium specificity is conferred by region F.

Figure 6.

Cysteine residues within region F are required for cadmium-induced transcription of MtnA. (A) Metal-induced expression of region F mutants. dMTF-1 mutant constructs containing cysteine to serine point mutations in region F were transiently transfected in triplicate into S2 cells with the metal inducible reporter pMtnA-Luc and a constitutively active transfection control, pMA-Ren. Metallothionein transcription was induced by the addition of copper or cadmium and luciferase activity was assayed. Firefly/renilla activity for each metal-treated mutant was normalized to WT dMTF-1 treated with the same metal and reported as relative activity. (B) Western blot analysis of transfected MTF-1 expression vectors. Blot was probed with anti-MTF-1 polyclonal sera and anti-tubulin monoclonal sera for relative expression levels.

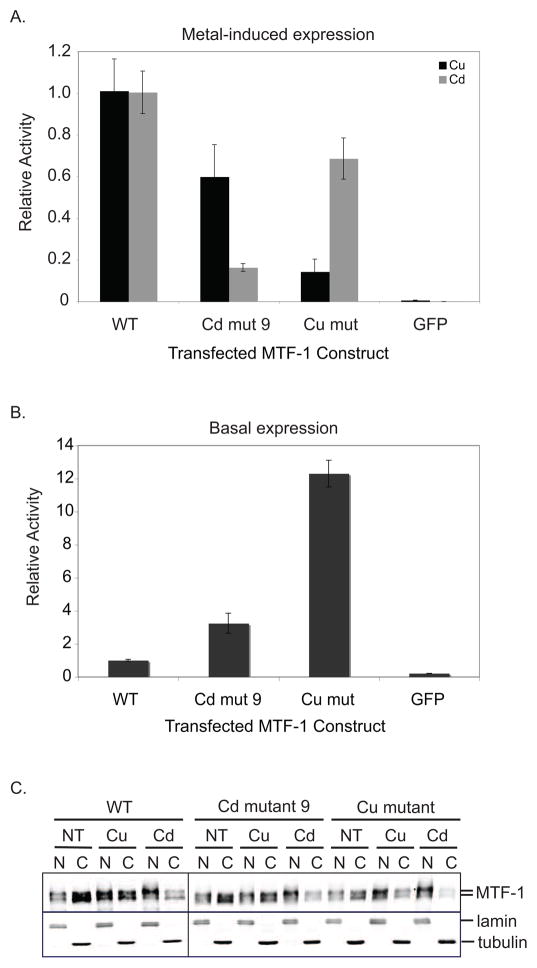

Figure 7.

Metal-specific activation of MtnA maps to separate domains of MTF-1. (A) Comparison of the metal-induced expression of MtnA-luciferase by the region F cadmium mutant 9 and the region E copper mutant. Copper mutant data from figure 2 and cadmium mutant 9 data from figure 6 are shown together for comparison. Firefly/renilla activity for each metal-treated mutant was normalized to WT dMTF-1 treated with the same metal and reported as relative activity. (B) MtnA-luciferase basal expression by the cadmium and copper mutants. Firefly/renilla activity for each mutant was normalized to WT dMTF-1. (C) Subcellular localization of mutants. WT and mutant dMTF-1 were transiently transfected into S2 cells and challenged with copper or cadmium. Nuclear and cytoplasmic extracts were prepared and immunoblotted for dMTF-1, nuclear lamin, and tubulin. N, nuclear extract; C, cytosolic extract; NT, no treatment; Cu, copper induction; Cd, cadmium induction.

We also evaluated the copper cluster mutant and region F cadmium mutant 9 for effects on basal MtnA transcription (figure 7B). The cadmium mutant is 3 times more active than wild type MTF-1 while the region E copper mutant is 12 times more active then wild type. These results mimic the basal activity we observe for the region F deletion and the combined deletion of regions E and F (BCDE and BCD, respectively; figure 5B). Thus, the autorepression in the absence of metal conferred by regions E and F is dependent on the same cysteine residues required for metal-activated transcription.

2.6 Metal specific mutations do not inhibit nuclear translocation or DNA binding

Although MTF-1 is present in the nucleus in the absence of metal, additional MTF-1 accumulates in the nucleus upon metal challenge[11, 28]. To verify that the metal specific mutations are only affecting transcriptional activity of dMTF-1 and not subcellular localization, we transiently transfected cultured Drosophila cells with dMTF-1 mutants, challenged the cells with either copper or cadmium, and prepared nuclear and cytosolic extracts. Immunoblot analysis of the fractions shows that both the cadmium mutant and the copper cluster mutant translocate to the nucleus in the presence of either copper or cadmium (figure 7C). This indicates that the transcriptional defect is not due to nuclear exclusion of the mutants.

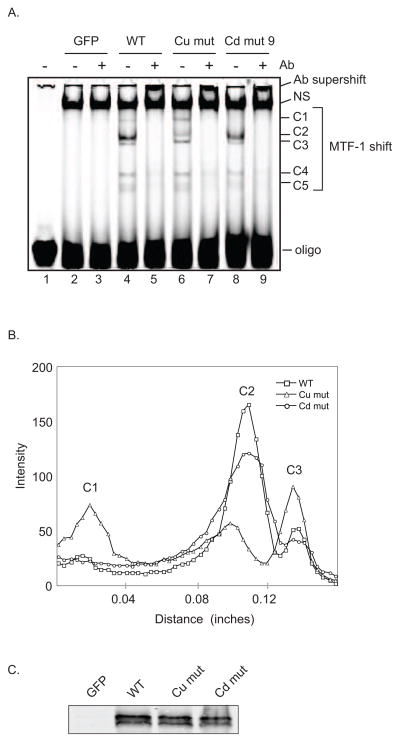

We also evaluated the dMTF-1 mutants for their ability to bind DNA. Extracts from transiently transfected Drosophila cells were subjected to electrophoretic mobility shift assays using a fluorescently-labeled oligo containing a single MRE site from MtnA known to bind dMTF-1 (unpublished results, M. Marr). Five dMTF-1 specific bands (C1–C5) are observed indicating that multiple complexes of MTF-1 are present (figure 8A). The prevalence of C1–C3 varies for the different MTF-1 mutants. All three complexes supershift with a monoclonal anti-FLAG antibody (M2) directed against the N- and C-terminal FLAG tags on the recombinant MTF-1. Unfortunately, the bands supershift into the wells but the antibody specific loss of the MTF-1/MRE complexes indicates that transfected MTF-1 is responsible for the shift. The distribution of MTF-1 into the 3 variable complexes depends on the status of the copper binding cluster and region F possibly indicating conformational differences between wild type and both mutants (figure 8B). The copper binding cluster mutant shows all three of the major complexes although the relative abundance of each is changed relative to wild type. The cadmium mutant contains only two of the observed complexes. Western blot analysis of extracts (figure 8C) shows that the three proteins were expressed at similar levels and the differences in the shifted bands are not due to changes in protein concentration. Additionally, multiple bands could arise from cleavage products of MTF-1 however western blot analysis of wild type and mutant extracts does not show any difference in protein banding pattern indicating that the differences in DNA binding are likely not due to proteolytic degradation. Human MTF-1 can form a homodimer [29] and it is possible that the multiple complexes of dMTF-1 represent a heterogenous population of monomers and dimers that vary between wildtype and mutants. Alternatively, tertiary and quaternary structural changes caused by the mutations could also explain the presence of multiple complexes.

Figure 8.

Loss of transcriptional activation by dMTF-1 mutants is not due to loss of DNA binding ability. (A) EMSA. WT dMTF-1 and mutants were transiently transfected into S2 cells. Two days post transfection, cell extracts were prepared and EMSA performed. dMTF-1 bound MRE complexes were supershifted with anti-FLAG antibody M2. (A) Lane 1, oligo alone; 2, GFP; 3, GFP + Ab; 4, MTF-1; 5, MTF-1 + Ab; 6, Cu mutant; 7, Cu mutant + Ab; 8, Cd mutant; 9, Cd mutant + Ab; NS, nonspecific band. (B) Plot profile of the MTF-1 shifted region from (A). Lane 4-MTF-1, squares; lane 6-cu mutant, triangles; lane 8-cd mutant, circles. (C) Immunoblot analysis. Equal volumes of EMSA extracts were analyzed by western blotting using dMTF-1 specific antibody. No endogenous dMTF-1 is detectable in the GFP control transfection.

2.7 Limited proteolysis reveals metal specific conformational changes

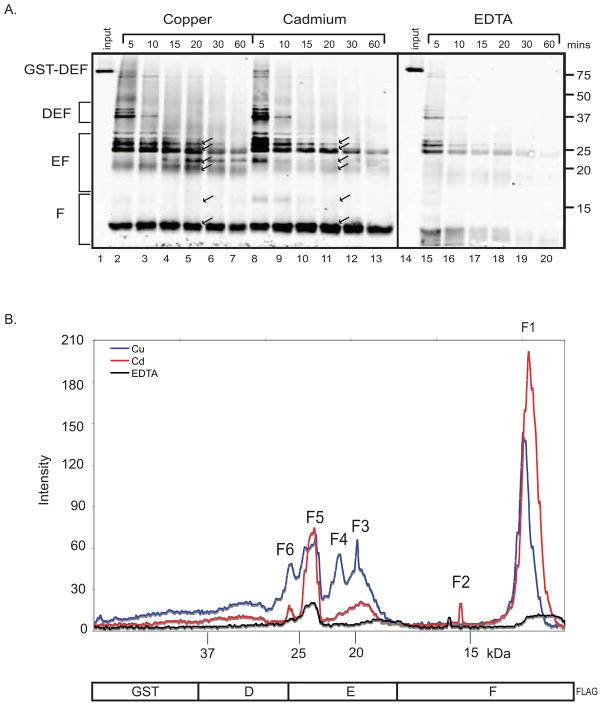

To investigate whether metal-specific conformational changes occur in the carboxy-terminus of dMTF-1, we performed limited proteolysis in the presence of EDTA, copper, or cadmium on a GST fusion protein containing the C-terminal activation domains (DEF) of dMTF-1 (figure 9A). Limited proteolysis is a well established technique for probing protein conformation by virtue of the fact that proteases can only cleave a protein within accessible loop regions while a tightly folded compact structure is resistant to cleavage[30]. The GST-DEF protein contains a FLAG-tag at the C-terminus, allowing western blot analysis of only C-terminal fragments using a FLAG-specific antibody (the DEF-FLAG domain is 42 kDa in size; EF-FLAG, 28 kDa; F-FLAG, 17 kDa). To maximize the identification of conformational changes we chose the aggressive protease proteinase K because of its broad substrate specificity. Rapid proteolysis was observed in the EDTA treated samples. However protection was specifically conferred by the presence of both copper and cadmium (figure 9A) but not for magnesium or calcium (supplemental data A). In addition a metal specific difference in cleavage pattern was evident between the copper and cadmium digests. The blot was analyzed using ImageJ software and an overlay of the plot profiles of all three digests is shown for the 20-minute time point to illustrate the metal specific differences (figure 9B). Fragment F1, representing the CTD of region F appeared rapidly in both digests and persisted throughout the entire time course, indicating that this is a very stable structure in the presence of metal. Intensity measurements of this band reveal that although it is protected from cleavage by both copper and cadmium, the band is more stable and persists longer in the presence of cadmium. At 20 minutes, there is nearly 2 times more of fragment F1 in the cadmium digest and at 60 minutes there is still 1.5 times more. Another region F specific fragment, F2, was evident early in the cadmium digest but disappeared rapidly with very little remaining at 20 minutes. Multiple region EF specific fragments (F3, F4, and F6) predominated specifically in the copper digest indicating a copper specific conformational change in region E. F5, another fragment containing both regions E and F, persisted throughout the entire time course for both metals (and degraded rapidly in the absence of metal) indicating that the C-terminus of dMTF-1 is a very stable structure when bound to metal. The differences in cleavage patterns indicate that MTF-1 assumes different conformations depending on the metal species bound.

Figure 9.

Interaction with metal alters dMTF-1 conformation. (A) Time course of partial proteolytic cleavage of GST-DEF. Western blot probed with anti-FLAG antibody. Lanes 1–7, copper digest; 8–13, cadmium digest; 15–20, EDTA digest. Reactions were removed and quenched after incubating for 5, 10, 15, 20, 30, and 60 minutes. Undigested GST-DEF (10%) loaded in lanes 1 and 14. Proteolytic fragments (F1–F6) identified in (B) are indicated with arrows; fragments are numbered numerically from smallest to largest. (B) Overlay of plot profiles at the 20-minute time point. Blue line, copper digest; red line, cadmium digest; black line, EDTA digest.

3. DISCUSSION

MTF-1 is a complex transcriptional activator that functions at multiple promoters in response to an array of signals. Transcriptional activation by dMTF-1 appears to be an intricate interplay of domains within the protein. Here we show that efficient copper- and cadmium-dependent activation require separate regions of MTF-1. Mutation of a single cysteine residue within the conserved C-terminal domain (amino acid 766) inhibits cadmium induction while maintaining copper responsiveness on MtnA. Likewise, copper induction by the copper cluster mutant is inhibited while maintaining cadmium responsiveness. These two mutants demonstrate that the metal specificity of dMTF-1 for MtnA lies within separate domains.

It has been shown that dMTF-1 binds copper within region E and it was hypothesized that binding of cadmium or zinc to the copper cluster might alter promoter specificity and thus transcriptional output[26]. Our results, however, indicate that the copper cluster mutant is capable of cadmium-stimulated transcription and it is residues within region F that are critical for cadmium activity. Partial proteolytic cleavage of the activation domains of dMTF-1 indicate that cadmium is likely binding and altering the conformation of MTF-1, presumably within region F.

While metal-liganding domains display specificity for particular metals, other metals can often bind with lower affinities[31]. The zinc fingers of MTF-1 bind six zinc ions, but recombinant hMTF-1 contains 7–8 mol equivalents of zinc indicating that zinc is binding outside the zinc finger domain[32]. In dMTF-1, the copper cluster in region E binds four molecules of copper with high affinity, but the same region can also bind both zinc and cadmium, albeit with lower affinity and in a stoichiometric 1:1 complex. The region appears to have little or no stable structure in the absence of metal[26]. In vivo, this region may bind zinc or cadmium in the absence of copper and alter the promoter specificity of dMTF-1. Our data show that the copper cluster mutant has slightly reduced transcriptional activation on MtnA in the presence of cadmium, indicating that this structural stabilization by other metals may play a role in dMTF-1 function. Our partial proteolysis results are consistent with this hypothesis. Binding of both copper and cadmium protected similar fragments from proteolytic cleavage in both regions E and F which could indicate that both of these regions can bind either metal in vitro. However there is a clear difference in the stability of these fragments under each metal condition, possibly reflecting binding affinities in these regions.

We attempted to probe conformational changes caused by the cadmium-specific mutation (C766S) using partial proteolysis. Only subtle changes were observed (supplemental data B). Although the cadmium-induced transcriptional activity was impaired by mutation of cysteine 766 within the CTD, region F contains 17 cysteine residues that can all potentially be involved in metal-liganding (and 9 of the 10 mutants we tested preferentially affected cadmium transcription). The copper cluster mutant was shown to retain partial activity when only 2 or 4 of the 6 cysteines were mutated indicating that partial metal binding was still present[26]. Thus it is likely that cysteine residues throughout region F contribute to metal binding and the point mutant retains partial metal binding capabilities. In support of this, a region F mutant containing mutations of the last four cysteines was severely impaired for transcription and when we attempted to purify this mutant from E. coli, it was rapidly degraded indicating that multiple cysteine mutations were highly deleterious and the last four cysteines are critical for both transcriptional activity and structural stabilization (data not shown).

The Gal4 fusion results presented here are similar to those observed for murine MTF-1[25]. Region D alone is a strong transactivator in the context of a gal4 system, but a fusion of all the transactivation domains was less active than region D alone. However, we did not observe transactivation potential for any domains other than D. This contrasts results with murine MTF-1 where all transactivation domains were at least partially functional in the Gal4 context. Unlike the situation with both mouse and human MTF-1, deletion of regions F or both E and F did not abolish dMTF-1 activity on the native MtnA promoter, indicating that Drosophila MTF-1 may detect metal differently than its mammalian counterparts.

Analysis of individual MTF-1 domains in the context of the native MtnA promoter revealed that, although independent domains confer metal specificity, important global interactions between transactivation domains are critical for transcriptional activity of dMTF-1. Region D alone is a strong transactivator in the context of a Gal4 system and region D fused to the MTF-1 DNA binding domain has a similar non-induced level of transcription compared to wild type dMTF-1 on the native MtnA promoter. Deleting regions E and F significantly increased basal transcription as did the presence of the copper- and cadmium-specific mutations. Very recently Gunther et. al. [33] published a study of Drosophila MTF-1 deletion mutants in the fly similar to some of the mutants presented here. They also identified regions E and F as autorepressive in the absence of metal and identified region D as a strong activation domain similar to our findings. Thus, although regions E and F are critical for metal-induced activity, their presence in the apo form of dMTF-1 are inhibitory and mask the transactivation potential of region D. This inhibitory effect is consistent with the fact that dMTF-1 is bound to the MtnA promoter in the absence of metal but is not highly transcriptionally active [11].

Transcriptional activation by dMTF-1 is a complex interplay of multiple domains. Neither the region F nor the EF deletion retained greater than 40% of metal-induced activity (and less than 5% of cadmium induced activity). In addition, the cadmium mutant (region F mutant 9) retained only 60% copper activity and the copper cluster mutant only retained 70% cadmium activity. It would appear that cooperativity between the metal-specific domains is required for full activity of dMTF-1. Mutations in either region may affect the global conformation of dMTF-1 which could alter protein multimerization, promoter binding or physical interactions with co-activators.

Unlike the prokaryotic metal sensing transcriptional regulators which function as on/off switches between apo and metal-bound forms[31], dMTF-1 appears more similar to the nuclear receptor (NR) superfamily of transcription factors, including estrogen receptor and glucocorticoid receptor. The NRs consist of three functional domains: transactivation domain, DNA binding domain and ligand binding domain (LBD) with the LBD containing a second transactivation domain. Binding of ligand to the LBD results in a conformational change which allows dimerization and interaction of the transactivation domains with coactivators and chromatin-remodeling complexes[34, 35]. Binding of antagonist to the LBD results in a different conformation that can interact with co-repressor proteins. This allows a tuning of the activation potential of NRs. Perhaps metal induced conformational changes in MTF-1 behave in a similar manner.

Sequence analysis of regions E and F reveal that there are fourteen glycine residues within a twenty-seven amino acid stretch at the border between regions E and F. This string of glycines should render this area highly flexible allowing movement between the domains. Our data support a model where dMTF-1 is MRE bound under normal metal load but assumes a conformation, with regions E and F blocking the activation domain within region D, thus preventing interaction with Mediator and recruitment of RNA polymerase. In the presence of metal, conformational changes within region E and F allow region D to interact with Mediator, recruit RNA polymerase, and initiate transcription in a metal dependent manner. Cadmium binding to region F results in a functional conformation favorable for cadmium-specific transcription while copper binding to the copper cluster in region E results in a conformation favorable for copper-specific output.

4. MATERIALS & METHODS

4.1 dMTF-1 mutations

All mutant dMTF-1 sequences were cloned into a Flag-tagged MTF-1 expression vector driven by a 445bp version of the Drosophila Actin 5C promoter (pAC-dMTF1). WT, full length dMTF-1; mutant 1, C642S, C643S; mutant 2, C657S, C658S; mutant 3, C671S, C673S; mutant 4, C684S, C685S; mutant 5, C699S, C700S; mutant 6, C718S, C719S, C720S; mutant 7, C748S, C750S; mutant 8, C761S, C762S; mutant 9, C766S; mutant 10, C787S; CTD combines mutants 8, 9, and 10, C761S, C762S, C766S, C787S; Δctd, deletion of amino acids 755–791; cu cluster mutant, C547S, C549S, C552S, C554S, C560S, C565S. ZF1, H134A, H128A; ZF2, H164A; ZF3, H194A, H198A; ZF4, H221A, H225A; ZF5, H251A; ZF6, H281A, H285A. Nuclear localization and DNA binding ability was verified for all mutants. Only the zinc finger mutants were found to be defective for DNA binding.

4.2 Cell culture, RNAi and transient transfections

Endogenous MTF-1 was depleted from all transfection assays by RNAi knockdown. Drosophila Schneider line 2 cells (S2 cells) were maintained at 27°C in Schneider’s Insect Medium containing 10% fetal bovine serum (Sigma). RNAi was carried out essentially as described by Clemens et. al. using 13 μg/ml dsRNA[36]. For the transient transfection experiments, cells were treated with dsRNA for 1 hour in the absence of serum followed by the addition of Chelex 100 treated complete medium containing 10% serum and transfection reagents. Cells were transfected using Effectene (Qiagen) according to manufacturers directions. Transfection mixes for 1.5×106 cells contained 23 ng of reporter and control plasmids (pMtnA-luc, containing 422bp of the MtnA promoter driving firefly expression [11] and pMA-Ren, containing 445bp of the constitutively active Actin 5C promoter driving expression of renilla luciferase), 2 ng of pAC-dMTF1 (or dMTF-1 mutants), and 2 μg of pAC-GFP as carrier DNA. Two days post-transfection cells were treated with 0.5 mM CuSO4 or 0.05 mM CdCl2 for 4 hours and luciferase assays were performed using the Dual-Luciferase Reporter Assay (Promega) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Metal induced expression of firefly luciferase was normalized to expression of renilla luciferase from a Drosophila Actin 5C promoter driving renilla expression.

4.3 Quantitative PCR

S2 cells were induced overnight with 0.5 mM CuS04 or 0.05 mM CdCl2. Cells were harvested by scraping, pelleted, and washed one time with 1X PBS. Total RNA was extracted using Qiagen RNeasy Mini kits according to manufacturer’s instructions. First strand cDNA synthesis was performed using MMLV RT (New England Biolabs) with random hexamers, and the RNA was digested using RNaseH (New England Biolabs). qPCR reactions were run on diluted cDNAs using iQ SYBR Green Supermix (Bio-Rad) with specific primers (75 nM) directed against the Drosophila MtnA (CTCGGAGCAGCCGCAGGCGG and GCCTTGCCCATGCGGAAGC) and Rp49 (CCACCAGTCGGATCGATATGC and CTCTTGAGAACGCAGGCGACC) transcripts on a Chromo4 Four-Color Real-Time PCR Detection System (Bio-Rad). MtnA expression was normalized to the ribosomal protein transcript RP49.

4.4 Partial proteolytic cleavage

A GST-DEF fusion was expressed and purified from E. coli using Glutathione Sepharose 4B (GE Healthcare) according to manufacturer’s instructions. Protein was stored in 2 mM EDTA to remove metals. Proteinase cleavage reactions contained 1 micromolar protein, 50 mM HEPES pH 7.4, 1 mM TCEP, 4 mM sodium ascorbate, and 5 mM CaCl2. Ascorbate is present in the reaction to convert Cu (II) to the biologically relevant form Cu(I)[37]. Reaction mixes were preincubated with 50 μM CuSO4, 50 μM CdCl2, or 10 mM EDTA for 10 minutes at room temperature. Cleavage was initiated by the addition of proteinase K at a substrate to enzyme mass ratio of 1/470 and incubated at 37°C for 15 minutes. Reactions were quenched by the addition of 1mM PMSF. Samples were electrophoresed on 15% SDS-PAGE gels, transferred to nitrocellulose, and probed with anti-FLAG antibody and fluorescent secondary antibody (Goat Anti-Mouse IgG, DyLight 800 Conjugated (Pierce)). Blots were scanned on an Odyssey infrared imaging system (LI-COR Biotechnology).

4.5 Preparation of nuclear and cytosolic extracts

1.25×106 cells were transfected with 0.5 μg of dMTF-1 expression plasmid. Two days post-transfection, cells were induced with 0.5 mM CuSO4 or 0.1 mM CdCl2 for 4 hours and harvested by scraping. Cells were pelleted and washed one time with 1x PBS. Cells were resuspended in 50 μl of cold hypotonic buffer (10 mM HEPES pH 7.6, 10 mM KCl, 1.5 mM MgCl2, 1 mM DTT and 1X SIGMAFAST protease inhibitor (Sigma)) and Triton X-100 was added to a final concentration of 0.5%. Following a 15-minute incubation on ice, nuclei were pelleted at 6000xG for 10 minutes at 4 °C. Cytoplasmic fraction was transferred to a fresh tube and nuclei were resuspended in 50 μl hypotonic buffer containing 0.5% Triton X-100. SDS load dye was added to both fractions and samples were electrophoresed on 6% SDS-PAGE gels, transferred to nitrocellulose membrane, and immunoblotted with anti-dMTF-1 polyclonal sera, anti-nuclear lamin monoclonal, or anti-tubulin monoclonal antibody.

4.6 GST pulldown

Sequences encoding region D of MTF-1 were cloned in frame into pGEX2TK (GE Healthcare). Both GST and the GST-MTF-1 fusion protein were purified from E. coli using Glutathione Sepharose 4B (GE Healthcare) according to manufacturers instructions except the proteins were left on the resin. Nuclear extract derived from 0–12 hour Drosophila embryos was incubated with the resin at 4°C overnight with constant mixing. The resin was washed three times with Wash buffer (20mM HEPES pH7.6, 500mM NaCl, 1mM DTT, 0.1mM EDTA, 0.1% NP-40, 1mM Glutamine, 10% Glycerol, PMSF, Aprotinin) and eluted in Wash buffer with 25mM glutathione and 40mM Tris pH7.9 (figure 4C) or 2X SDS loading buffer (figure 4D). Samples of the elution were separated by SDS page and probed with antibodies against MED17, MED26, and TBP[11].

4.7 Electrophoretic mobility shift assay (EMSA)

5×106 cells were transfected with 1 μg of dMTF-1 expression plasmid and harvested by scraping two days post-transfection. Cells were pelleted for 10 minutes at 1000xG and washed with 1x PBS. Cell pellet was resuspended in 50 μl of lysis buffer (50 mM Tris pH 7.5, 1 mM DTT, 1 mM sodium metabisulfite, 0.4 M potassium glutamate, 10% glycerol, 0.5% Triton X-100), incubated on ice 30 minutes, and centrifuged for 15 minutes at 4 °C. Extracts (3 μl) were incubated in a total volume of 10 μl for 15 minutes at room temperature in binding buffer (10 mM Tris pH 7.5, 5 mM MgCl2, 5 mM DTT, 0.5% Tween-20, 100 μM zinc acetate, and 10% glycerol) with 10 nM double-stranded Cy5.5 end labeled MRE oligo (top strand, 5′CY5.5-AGCTTCTGCACACGTCTCCACTCGAATTTGG; bottom strand, 5′CY5.5-AGCTCCAAATTCGAGTGGAGACGTGTGCAGA) and non-specific competitor (25 ng salmon sperm DNA and 50 ng BSA). 50 ng of anti-FLAG affinity-purified monoclonal antibody (M2, Sigma) was added and incubated an additional 15 minutes. Protein-DNA complexes were separated electrophoretically at 4 °C in 5% acrylamide containing 1xTGE (25 mM Tris, 190 mM glycine, 1 mM EDTA), 4 mM MgCl2, 100 μM zinc acetate and 2.5% glycerol. Gels were scanned on the 700 channel of an Odyssey infrared imaging system (LI-COR Biotechnology).

4.8 Immunoblotting

Protein extracts were separated on 6% SDS-PAGE gels, transferred to nitrocellulose, and probed with anti-dMTF-1 polyclonal sera or anti-FLAG monoclonal antibody (Sigma) and fluorescent secondary antibody (Goat Anti-Rabbit IgG, DyLight 800 Conjugated or Goat Anti-Mouse IgG, DyLight 800 Conjugated (Pierce)). Blots were scanned on an Odyssey infrared imaging system (LI-COR Biotechnology). MTF-1 is post-translationally modified and runs as a doublet on low percentage gels.

Supplementary Material

(A) Partial proteolytic cleavage of GST-DEF in the presence of non-specific metals. Reactions containing 50 μM copper sulfate (Cu), magnesium chloride (Mg), calcium chloride (Ca) or EDTA were removed and quenched after a 15 minute digestion with proteinase K. Western blot probed with anti-FLAG antibody. (B) Partial proteolytic cleavage of GST-DEF containing metal-specific mutations. GST-DEF proteins containing the copper cluster cysteine mutations (Cu mut) or the region F cadmium specific cysteine 766 mutation were compared to wild type (WT) in the presence of copper (Cu), cadmium (Cd) or EDTA. Reactions were quenched after a 5 minute digestion. Samples were subjected to SDS-PAGE on both 15% and 12% acrylamide gels. Undigested GST-DEF (10%) was loaded as a control (input).

Highlights.

Separate domains of dMTF-1 confer metal specificity.

The metal-binding domains are autorepressive in the absence of metal.

Mutations in the conserved CTD affect cadmium- but not copper-induced transcription.

Mutations in the copper cluster have little effect on cadmium-induced transcription.

Metal specific conformational changes of dMTF-1.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank Anuja Mehta for construction of the zinc finger mutants. This work was supported by R01GM085250 from the National Institute Of General Medical Sciences and a Basil O’Connor Starter Scholar Research Award from the March of Dimes (#5-FY09-122).

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.DiDonato M, Sarkar B. Copper transport and its alterations in Menkes and Wilson diseases. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1997;1360:3–16. doi: 10.1016/s0925-4439(96)00064-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Harris ED. Basic and clinical aspects of copper. Crit Rev Clin Lab Sci. 2003;40:547–586. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Martelli A, Rousselet E, Dycke C, Bouron A, Moulis JM. Cadmium toxicity in animal cells by interference with essential metals. Biochimie. 2006;88:1807–1814. doi: 10.1016/j.biochi.2006.05.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Brugnera E, Georgiev O, Radtke F, Heuchel R, Baker E, Sutherland GR, Schaffner W. Cloning, chromosomal mapping and characterization of the human metal-regulatory transcription factor MTF-1. Nucleic Acids Res. 1994;22:3167–3173. doi: 10.1093/nar/22.15.3167. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Radtke F, Heuchel R, Georgiev O, Hergersberg M, Gariglio M, Dembic Z, Schaffner W. Cloned transcription factor MTF-1 activates the mouse metallothionein I promoter. EMBO J. 1993;12:1355–1362. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1993.tb05780.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Zhang B, Egli D, Georgiev O, Schaffner W. The Drosophila homolog of mammalian zinc finger factor MTF-1 activates transcription in response to heavy metals. Mol Cell Biol. 2001;21:4505–4514. doi: 10.1128/MCB.21.14.4505-4514.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Egli D, Domenech J, Selvaraj A, Balamurugan K, Hua H, Capdevila M, Georgiev O, Schaffner W, Atrian S. The four members of the Drosophila metallothionein family exhibit distinct yet overlapping roles in heavy metal homeostasis and detoxification. Genes Cells. 2006;11:647–658. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2443.2006.00971.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Guirola M, Naranjo Y, Capdevila M, Atrian S. Comparative genomics analysis of metallothioneins in twelve Drosophila species. J Inorg Biochem. 2011;105:1050–1059. doi: 10.1016/j.jinorgbio.2011.05.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Atanesyan L, Gunther V, Celniker SE, Georgiev O, Schaffner W. Characterization of MtnE, the fifth metallothionein member in Drosophila. J Biol Inorg Chem. 2011;16:1047–1056. doi: 10.1007/s00775-011-0825-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Egli D, Selvaraj A, Yepiskoposyan H, Zhang B, Hafen E, Georgiev O, Schaffner W. Knockout of ‘metal-responsive transcription factor’ MTF-1 in Drosophila by homologous recombination reveals its central role in heavy metal homeostasis. EMBO J. 2003;22:100–108. doi: 10.1093/emboj/cdg012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Marr MT, 2nd, Isogai Y, Wright KJ, Tjian R. Coactivator cross-talk specifies transcriptional output. Genes Dev. 2006;20:1458–1469. doi: 10.1101/gad.1418806. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Egli D, Yepiskoposyan H, Selvaraj A, Balamurugan K, Rajaram R, Simons A, Multhaup G, Mettler S, Vardanyan A, Georgiev O, Schaffner W. A family knockout of all four Drosophila metallothioneins reveals a central role in copper homeostasis and detoxification. Mol Cell Biol. 2006;26:2286–2296. doi: 10.1128/MCB.26.6.2286-2296.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Silar P, Theodore L, Mokdad R, Erraiss NE, Cadic A, Wegnez M. Metallothionein Mto gene of Drosophila melanogaster: structure and regulation. J Mol Biol. 1990;215:217–224. doi: 10.1016/S0022-2836(05)80340-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Murata M, Gong P, Suzuki K, Koizumi S. Differential metal response and regulation of human heavy metal-inducible genes. J Cell Physiol. 1999;180:105–113. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1097-4652(199907)180:1<105::AID-JCP12>3.0.CO;2-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Sadhu C, Gedamu L. Regulation of human metallothionein (MT) genes. Differential expression of MTI-F, MTI-G, and MTII-A genes in the hepatoblastoma cell line (HepG2) J Biol Chem. 1988;263:2679–2684. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Wang Y, Lorenzi I, Georgiev O, Schaffner W. Metal-responsive transcription factor-1 (MTF-1) selects different types of metal response elements at low vs. high zinc concentration. Biol Chem. 2004;385:623–632. doi: 10.1515/BC.2004.077. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Chen X, Agarwal A, Giedroc DP. Structural and functional heterogeneity among the zinc fingers of human MRE-binding transcription factor-1. Biochemistry. 1998;37:11152–11161. doi: 10.1021/bi980843r. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Chen X, Chu M, Giedroc DP. MRE-Binding transcription factor-1: weak zinc-binding finger domains 5 and 6 modulate the structure, affinity, and specificity of the metal-response element complex. Biochemistry. 1999;38:12915–12925. doi: 10.1021/bi9913000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Giedroc DP, Chen X, Apuy JL. Metal response element (MRE)-binding transcription factor-1 (MTF-1): structure, function, and regulation. Antioxid Redox Signal. 2001;3:577–596. doi: 10.1089/15230860152542943. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Andrews GK. Cellular zinc sensors: MTF-1 regulation of gene expression. Biometals. 2001;14:223–237. doi: 10.1023/a:1012932712483. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Heuchel R, Radtke F, Georgiev O, Stark G, Aguet M, Schaffner W. The transcription factor MTF-1 is essential for basal and heavy metal-induced metallothionein gene expression. EMBO J. 1994;13:2870–2875. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1994.tb06581.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Selvaraj A, Balamurugan K, Yepiskoposyan H, Zhou H, Egli D, Georgiev O, Thiele DJ, Schaffner W. Metal-responsive transcription factor (MTF-1) handles both extremes, copper load and copper starvation, by activating different genes. Genes Dev. 2005;19:891–896. doi: 10.1101/gad.1301805. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Wang Y, Wimmer U, Lichtlen P, Inderbitzin D, Stieger B, Meier PJ, Hunziker L, Stallmach T, Forrer R, Rulicke T, Georgiev O, Schaffner W. Metal-responsive transcription factor-1 (MTF-1) is essential for embryonic liver development and heavy metal detoxification in the adult liver. FASEB J. 2004;18:1071–1079. doi: 10.1096/fj.03-1282com. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Balamurugan K, Egli D, Selvaraj A, Zhang B, Georgiev O, Schaffner W. Metal-responsive transcription factor (MTF-1) and heavy metal stress response in Drosophila and mammalian cells: a functional comparison. Biol Chem. 2004;385:597–603. doi: 10.1515/BC.2004.074. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Radtke F, Georgiev O, Muller HP, Brugnera E, Schaffner W. Functional domains of the heavy metal-responsive transcription regulator MTF-1. Nucleic Acids Res. 1995;23:2277–2286. doi: 10.1093/nar/23.12.2277. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Chen X, Hua H, Balamurugan K, Kong X, Zhang L, George GN, Georgiev O, Schaffner W, Giedroc DP. Copper sensing function of Drosophila metal-responsive transcription factor-1 is mediated by a tetranuclear Cu(I) cluster. Nucleic Acids Res. 2008;36:3128–3138. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkn103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Bittel DC, Smirnova IV, Andrews GK. Functional heterogeneity in the zinc fingers of metalloregulatory protein metal response element-binding transcription factor-1. J Biol Chem. 2000;275:37194–37201. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M003863200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Smirnova IV, Bittel DC, Ravindra R, Jiang H, Andrews GK. Zinc and cadmium can promote rapid nuclear translocation of metal response element-binding transcription factor-1. J Biol Chem. 2000;275:9377–9384. doi: 10.1074/jbc.275.13.9377. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Gunther V, Davis AM, Georgiev O, Schaffner W. A conserved cysteine cluster, essential for transcriptional activity, mediates homodimerization of human metal-responsive transcription factor-1 (MTF-1) Biochim Biophys Acta. 2012;1823:476–483. doi: 10.1016/j.bbamcr.2011.10.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Hubbard SJ. The structural aspects of limited proteolysis of native proteins. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1998;1382:191–206. doi: 10.1016/s0167-4838(97)00175-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Pennella MA, Giedroc DP. Structural determinants of metal selectivity in prokaryotic metal-responsive transcriptional regulators. Biometals. 2005;18:413–428. doi: 10.1007/s10534-005-3716-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Chen X, Zhang B, Harmon PM, Schaffner W, Peterson DO, Giedroc DP. A novel cysteine cluster in human metal-responsive transcription factor 1 is required for heavy metal-induced transcriptional activation in vivo. J Biol Chem. 2004;279:4515–4522. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M308924200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Gunther V, Waldvogel D, Nosswitz M, Georgiev O, Schaffner W. Dissection of Drosophila MTF-1 reveals a domain for differential target gene activation upon copper overload vs. copper starvation. Int J Biochem Cell Biol. 2012;44:404–411. doi: 10.1016/j.biocel.2011.11.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Celik L, Lund JD, Schiott B. Conformational dynamics of the estrogen receptor alpha: molecular dynamics simulations of the influence of binding site structure on protein dynamics. Biochemistry. 2007;46:1743–1758. doi: 10.1021/bi061656t. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Nicolaides NC, Galata Z, Kino T, Chrousos GP, Charmandari E. The human glucocorticoid receptor: molecular basis of biologic function. Steroids. 2010;75:1–12. doi: 10.1016/j.steroids.2009.09.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Clemens JC, Worby CA, Simonson-Leff N, Muda M, Maehama T, Hemmings BA, Dixon JE. Use of double-stranded RNA interference in Drosophila cell lines to dissect signal transduction pathways. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2000;97:6499–6503. doi: 10.1073/pnas.110149597. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Fabisiak JP, Tyurin VA, Tyurina YY, Borisenko GG, Korotaeva A, Pitt BR, Lazo JS, Kagan VE. Redox regulation of copper-metallothionein. Arch Biochem Biophys. 1999;363:171–181. doi: 10.1006/abbi.1998.1077. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

(A) Partial proteolytic cleavage of GST-DEF in the presence of non-specific metals. Reactions containing 50 μM copper sulfate (Cu), magnesium chloride (Mg), calcium chloride (Ca) or EDTA were removed and quenched after a 15 minute digestion with proteinase K. Western blot probed with anti-FLAG antibody. (B) Partial proteolytic cleavage of GST-DEF containing metal-specific mutations. GST-DEF proteins containing the copper cluster cysteine mutations (Cu mut) or the region F cadmium specific cysteine 766 mutation were compared to wild type (WT) in the presence of copper (Cu), cadmium (Cd) or EDTA. Reactions were quenched after a 5 minute digestion. Samples were subjected to SDS-PAGE on both 15% and 12% acrylamide gels. Undigested GST-DEF (10%) was loaded as a control (input).