Abstract

Background

Memantine is licensed for moderate-to-severe Alzheimer's disease (AD). National Institute for Clinical Excellence (NICE) guidance does not recommend the use of memantine in combination with cholinesterase inhibitors (acetylcholinesterase inhibitor (AChEI)). The underpinning meta-analysis was disputed by the manufacturer.

Objectives

To compare the efficacy of AChEI monotherapy with combination memantine and AChEI therapy in patients with moderate-to-severe AD and to examine the impact of including unpublished data on the results.

Design

Systematic review and meta-analysis of randomised controlled trials.

Data sources

The Cochrane Dementia Group trial register, ALOIS, searched for the last time on 3 May 2011.

Data synthesis

Data from four domains (clinical global, cognition, function, behaviour and mood) were pooled. Sensitivity analyses examined the impact on the NICE-commissioned meta-analysis of restricting data to patients with moderate-to-severe AD and of including an unpublished trial of an extended release preparation of memantine.

Results

Pooled data from the trials, which were included in the NICE-commissioned meta-analysis but which were restricted to moderate-to-severe AD only, showed a small effect of combination therapy on cognition (standardised mean difference (SMD)=−0.29, 95% CI −0.45 to −0.14). Adding data from an unpublished trial of an extended release memantine (total three trials, 1317 participants) showed a small benefit of combination therapy on global scores (SMD=−0.20, 95% CI −0.31 to −0.09), cognition (SMD=−0.25, 95% CI −0.36 to −0.14) and behaviour and mood (SMD=−0.17, 95% CI −0.32 to −0.03) but not on function (SMD=−0.04, 95% CI −0.21 to 0.13) at 6 months. No clinical data have been reported from a 1-year trial, although this found ‘no significant benefit’ on any clinical measures at 1 year.

Conclusions

These results suggest that there may be a small benefit at 6 months of adding memantine to AChEIs. However, the impact on clinical global impression depends on exactly which studies are included, and there is no benefit on function, so its clinical relevance is not robustly demonstrated. Currently available information from randomised controlled trails indicates no benefit of combination therapy over monotherapy at 1 year. Legislation on the form and content of registry posted results is needed in Europe.

Article summary

Article focus

To compare the efficacy of AChEI monotherapy with combination memantine and AChEI therapy in patients with moderate-to-severe AD.

To examine the impact of including unpublished data on the results.

Key messages

Combination AChEI and memantine therapy is of greater benefit in AD than AChEIs alone, but the clinical relevance depends on exactly which studies are included so is not robustly demonstrated.

Unpublished data in registry postings can still obscure important negative clinical findings.

International harmonisation of reporting of all clinical variables is needed.

Strengths and limitations of this study

Systematic review including sources of unpublished data.

Not all relevant data were available for meta-analysis.

Introduction

Two classes of drugs are licensed by the European Medicines Agency for the treatment of Alzheimer's disease (AD): acetylcholinesterase inhibitors (AChEIs) for mild-to-moderate disease and memantine for moderate (Mini-Mental State Examination (MMSE) 10–19) and severe disease (MMSE <10).1 Memantine is a moderate affinity non-competitive NMDA receptor antagonist, which blocks the effects of tonic pathologically elevated levels of glutamate that may lead toneuronal dysfunction. It has a small but consistent effect, but its place in therapy has been controversial in Europe.

Both National Institute for Clinical Excellence (NICE) and IQWiG (the German Institute for Quality and Efficiency in Healthcare) have revised their original conclusions that there was insufficient evidence to recommend memantine as a monotherapy for AD.2–4 Following the release of IQWiQ's original report in 2009,3 the manufacturer of ‘Axura’ memantine, Merz, submitted a responder analysis, presenting data from two previously excluded unpublished trials, IE2101 and MD-22. Despite initially stating that this analysis could not be used,5 IQWiG revised their conclusion and in 2011 reported that the new data provided proof of a benefit of memantine on cognition in AD.4

The NICE currently recommends the use of memantine in severe disease or as a second-line treatment in moderate disease for patients who are intolerant or have a contraindication to AChEIs. However, it does not recommend the use of memantine in combination with AChEIs, stating that there is ‘a lack of evidence of additional clinical efficacy compared with monotherapy’.2 This contrasts with the conclusions of a recent company-sponsored non-systematic review,6 which asserts that it is “safe, well-tolerated, and may represent the current gold standard for treatment of moderate-severe AD and possibly mild-to-moderate AD as well.” Memantine does not have a licence for mild AD, and evidence is lacking for a clinical benefit in this group.7

In the meta-analysis, which informed the guidance (TA217),8 two trials are included in the analysis of combination therapy.9 10 Data for cognitive and activities of daily living (ADL)/function outcomes were controversially not pooled on the grounds that different scoring systems were used by the included trials. Pooled analyses in the other domains (global and behavioural) showed no benefit. A further source of dispute was that data from patients with mild AD in one of the trials (MD-12)10 were included despite the separate availability of data (in Winblad et al (2007)11) for just the subgroup of patients with moderate AD, which falls within the licensed indication.

As part of a Cochrane review, we conducted a systematic review, meta-analysis and sensitivity analyses to examine the impact of these issues and of the inclusion of unpublished data on the efficacy of combination memantine and AChEI therapy in moderate-to-severe AD.

Methods

Search methods

ALOIS, the Cochrane Dementia and Cognitive Improvement Group's comprehensive, free access register of trials12 that contain records from all relevant sources, was searched for the final time on 3 May 2011. The search terms used were memantine, D-145, DMAA, DRG-0267, ebixa, abixa, axura, akatinol, memox and namenda. ALOIS is maintained by the Trials Search co-ordinator and contains studies in the areas of dementia prevention, dementia treatment and cognitive enhancement in healthy participants. The studies are identified from:

Monthly searches of a number of major healthcare databases: MEDLINE, EMBASE, CINAHL, PsycINFO and LILACS.

Monthly searches of a number of national and international trial registers: ISRCTN; UMIN (Japan's Trial Registry); ICTRP/WHO portal (which covers ClinicalTrials.gov; ISRCTN; the Chinese Clinical Trials Register; the German Clinical Trials Register; the Iranian Registry of Clinical Trials and the Netherlands National Trials Register, plus others).

Quarterly search of The Cochrane Library's Central Register of Controlled Trials (CENTRAL).

Six-monthly searches of a number of grey literature sources: ISI Web of Knowledge Conference Proceedings; Index to Theses; Australasian Digital Theses.

Details of the search strategies used for the retrieval of reports of trials from the healthcare databases, from Cochrane CENTRAL and from conference proceedings can be viewed in the ‘Methods used in reviews’ section within the editorial information section of the Dementia and Cognitive Improvement Group's website.13

Additionally, the clinical trials registries of Lundbeck, Forest and the Japanese registry the Japanese Pharmaceutical Information Centre, the websites of the US Food and Drug Administration, the European Medicines Agency, NICE and press releases of manufacturers (Lundbeck, Merz, Forest, Suntori, Asubio, Daiichi) and all conference posters of studies sponsored by Merz, Lundbeck and Forest presented in 2004–2009 were studied in detail. Authors and companies were contacted directly with requests for missing information. A full account of the search strategy is available in the full Cochrane review from which this paper is drawn.

Trial inclusion criteria

Trials were included if they were (1) double-blind, parallel group, placebo-controlled randomised trials of memantine in patients with moderate-to-severe AD who were taking AChEIs, (2) sample selection criteria were specified and diagnosis used established criteria and (3) outcome instruments were specified.

Data extraction

We extracted clinical and demographic characteristics and outcome data relating to patients with moderate and severe AD from the trial reports and, where not available from primary reports, from a company-sponsored meta-analysis, which was conducted during the European regulatory review process.11 The data were extracted independently by at least two people, and discrepancies were resolved by discussion. The outcomes of interest were clinical global impression, cognitive function, functional performance in ADL and mood and behavioural disturbance. These were assessed using instruments, including the Clinician's Interview-Based Impression of Change plus caregiver's input (CIBIC-plus), the Alzheimer's Disease Assessment Scale–Cognitive subscale (ADAS-Cog) and Severe Impairment Battery (SIB), the Alzheimer's Disease Cooperative Study–Activities of Daily Living (ADCS-ADL) scale (19- and 23-item) and the Neuropsychiatric Inventory (NPI).

Data synthesis and analysis

Data from each of the four clinical domains were pooled separately, and a random-effects model (DerSimonian-Laird) was used to estimate differences between groups. Effect sizes were presented as standardised mean differences (SMDs)—the absolute mean difference divided by the SD—with 95% CIs and p values, calculated using Revman V.5.0 software.14 This meant that data could be pooled when different rating scales (eg, SIB and ADAS-Cog) were used to assess the same outcome. In the TA217 assessment report, all effect sizes were presented as weighted mean differences (WMDs), and data were not pooled when included trials used different rating scales. In this review, we have replicated the findings of the TA217 report for comparison, presenting them first as WMDs (as in the original report) in analysis 1a, and then as SMDs in analysis 1b.

Sensitivity analyses were performed to examine the effect sizes in the NICE-commissioned assessment report8 in comparison with those derived from all available data, which are as follows:

1a. Replication of TA217 assessment report analysis, presented as WMDs.

1b. Replication of TA217 assessment report analysis, presented as SMDs for comparison.

2. Pooled data from trials included in the TA217 assessment report, presented as SMDs, excluding data from patients with mild disease.

3. As in 2, but from all trials meeting our inclusion criteria.

Results

Description of studies

Five trials were identified (MD-02,9 MD-12,10 MD-50,15 Lu1011216 and DOMINO-AD17) that met inclusion criteria, of which three (MD-02,9 MD-1210 and MD-5015) were included in this meta-analysis. Of these, MD-02 and MD-12 were included in the TA217 assessment report analysis of memantine combination therapy.9 10 One trial (MD-029) was of patients with moderate-to-severe disease (MMSE range 5–14, average score 10.0) and another trial (MD-1210) was of mild-to-moderate disease (MMSE range 10–22, average score 16.9). Data for the subgroup of patients in MD-12 with moderate AD were available through a published company-sponsored meta-analysis.11 MD-5015 studied an extended release (ER) preparation of 28 mg/day, which has recently been granted a licence by the US Food and Drug Administration18 but is not currently marketed in the USA, is not licensed in Europe and would have been ineligible for inclusion in the NICE meta-analysis.

Two 12-month trials (Lu1011216 and DOMINO-AD17) of combination therapy that met trial inclusion criteria were excluded from this review. First, a randomised controlled trial (Lu1011216) of 277 patients with moderate AD in which the primary was an imaging outcome, and in which 72% of patients were taking an AChEI, was completed in February 2009. A conference poster in September 200919 and a registry posting in May 201016 did not report details of important clinical data (ADAS-Cog, Neuropsychiatric Inventory, time to institutionalisation) but reported that there was no significant benefit of memantine on these measures at 12 months. The cut-off point for inclusion in the TA217 meta-analysis was March 2010.8 Total brain atrophy rates were greater in those taking combination therapy than in those taking memantine alone.19 Second, data were not yet available from the DOMINO-AD trial,17 which includes comparison of monotheraphy and combination therapy and is due to report shortly.

Participants

The total number of participants was 1317. All patients were diagnosed with AD, classed as mild, moderate or severe disease based on their MMSE score. Table 1 shows the baseline characteristics of participants.

Table 1.

Characteristics of included studies (including baseline characteristics of participants)

| Trial | MMSE inclusion range (mean score) | Trial duration (weeks) | Total no. of patients | No. of patients in placebo + AChEI and memantine + AChEI groups |

Mean age | Mean cognitive score (score used) | Mean function score (score used) | Mean behaviour/mood score (NPI) | Outcomes measured | Scores used | |

| MD-02/Tariot et al (2004)9 | Moderate-to-severe AD, 5–14 (10.0) | 24 | 403 | Placebo + AChEI | 203 | 75.5 | 80.0 (SIB) | 35.8 (ADCS-ADL19) | 13.4 |

|

CIBIC-plus, SIB, ADCS-ADL19, NPI |

| Memantine + AChEI | 201 | 75.5 | 78.0 (SIB) | 35.5 (ADCS-ADL19) | 13.4 | ||||||

| MD-12/Porsteinsson et al (2008)10 | Mild-to-moderate AD, 10–22 (16.9) | 24 | 433 | Placebo + AChEI | 216 | 76.0 | 26.8 (ADAS-Cog) | 54.8 (ADCS-ADL23) | 12.3 |

|

CIBIC-plus, ADAS-Cog, ADCS-ADL23 NPI |

| Memantine + AChEI | 217 | 74.9 | 27.9 (ADAS-Cog) | 54.7 (ADCS-ADL23) | 11.8 | ||||||

| MD-12/Porsteinsson et al (2008)10—subgroup with moderate disease, from Winblad et al (2007)11 | Moderate AD | 24 | 302 | Placebo + AChEI | 148 | Not known* | Not known* | Not known* | Not known* | ||

| Memantine + AChEI | 154 | Not known* | Not known* | Not known* | Not known* | ||||||

| MD-50/Grossberg et al (2008)15 | Moderate-to-severe AD, 3–14 (10.8) | 24 | 697 | Placebo + AChEI | 355 | Not known† | Not known† | Not known† | Not known† |

|

CIBIC-plus, SIB, ADCS-ADL19, NPI |

| Memantine + AChEI | 342 | Not known† | Not known† | Not known† | Not known† | ||||||

The global score, CIBIC-plus, is a measure of change from baseline, so baseline scores are not given as they are not applicable.

The data from the subgroup of patients with moderate disease is taken from the meta-analysis by Winblad et al (2007),11 which does not present the baseline characteristics for this subgroup.

The baseline characteristics of patients in this unpublished study are not given.

AChEI, acetylcholinesterase inhibitor; AD, Alzheimer's disease.

Interventions

MD-02 and MD-12 compared the efficacy and safety of adding 20 mg/day memantine with placebo in patients receiving stable treatment with donepezil (an AChEI). MD-50 compared the efficacy and safety of adding an ER preparation of 28 mg/day memantine, equivalent to 20 mg daily, with placebo in patients receiving a stable dose of any cholinesterase inhibitor.

Outcome measures

The primary outcomes of interest were clinical global impression, cognitive function, functional performance in ADL and behavioural and mood disturbance.

Quality of included studies

The commercially sponsored studies conducted after 1993 are likely to have conformed to International Conference on Harmonisation Good Clinical Practice standard and to have been at low risk of bias with regards their sequence generation, allocation concealment and methods of blinding. In the included studies, the characteristics of the treatment and placebo groups were well balanced at baseline (table 1). The risk of bias of the included studies was judged to be low as indicated in the ‘risk of bias’ tables in the main Cochrane Review from which this systematic review is derived.

Results of individual studies

Of the three included studies, MD-029 showed a significant benefit of combination therapy (memantine plus AChEI) compared with AChEI monotherapy on cognition, ADL, global outcome and behaviour. Combination therapy was well tolerated. MD-1210 showed no advantage of combination therapy compared with AChEI monotherapy in any domain in the overall group of patients with mild as well as moderate disease. There were no significant differences in safety or tolerability between the two groups. Data from the subset of patients in MD-1210 with moderate disease were taken from the meta-analysis by Winblad et al (2007).11 MD-5015 showed a statistically significant improvement from combination memantine ER plus AChEI therapy compared with AChEI monotherapy ER on cognition, global improvement and behaviour, but not on function, after 6 months. Memantine ER was well tolerated.

Results of synthesis of studies

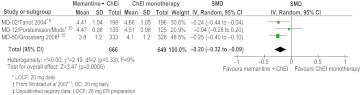

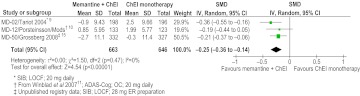

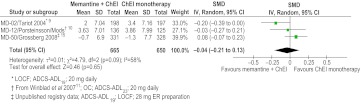

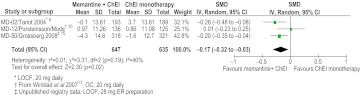

The synthesis of data from trials of memantine combination therapy is summarised in table 2 and figures 1–4. Analysis 1a shows the analysis conducted in TA127. Analysis 1b shows that had TA127 pooled cognitive and functional data across different instruments using standardisation; there would still have been no domains where combination therapy was significantly better than AChEI monotherapy. Analysis 2 shows the impact of excluding data from patients with mild disease: there was a small (SMD=−0.29, 95% CI −0.45 to −0.14) significant benefit of memantine combination therapy on cognition but not on any other outcome. Analysis 3, the most inclusive analysis, shows that when data from the memantine ER trial (MD-5015) was also pooled, the small benefit on cognition persisted (SMD=−0.25, 95% CI −0.36 to −0.14), and there were also small significant benefits of combination therapy on the global improvement score (SMD=−0.20, 95% CI −0.32 to −0.09) and on behaviour and mood (SMD=−0.17, 95% CI −0.32 to −0.03) but not on function (SMD=−0.04, 95% CI −0.21 to 0.13).

Table 2.

Memantine combination therapy (results of synthesis of data)

| Analysis no. and description, trials included—code (LOCF/OC data) | Efficacy domain |

|||||||

| Clinical global |

Cognition |

Function |

Behaviour + mood |

|||||

| SMD/WMD (95% CI) | p Value | SMD (95% CI) | p Value | SMD/WMD (95% CI) | p Value | SMD/WMD (95% CI) | p Value | |

| Analysis 1a: trials included in the TA217 assessment report, data presented as WMDs | ||||||||

| MD-029 (LOCF data) | WMD=−0.140 (−0.346 to 0.066) | 0.182 | Data not pooled | Data not pooled | WMD=−1.715 (−5.733 to 2.302) | 0.403 | ||

| MD-1210 (LOCF data) | ||||||||

| Analysis 1b: trials included in the TA217 assessment report, data presented as SMDs | ||||||||

| MD-029 (LOCF data) | SMD=−0.14 (−0.33 to 0.06) | 0.16 | SMD=−0.16 (−0.54 to 0.23) | 0.43 | SMD=−0.10 (−0.28 to 0.08) | 0.27 | SMD=−0.13 (−0.42 to 0.17) | 0.41 |

| MD-1210 (LOCF data) | ||||||||

| Analysis 2: trials included in the TA217 assessment report. Data from patients with mild AD excluded. Data pooled within domains (SMDs) | ||||||||

| MD-029 (LOCF data) | SMD=−0.15 (−0.35 to 0.04) | 0.12 | SMD=−0.29 (−0.45 to −0.14) | 0.0002 | SMD=−0.13 (−0.29 to 0.03) | 0.11 | SMD=−0.14 (−0.42 to 0.14) | 0.32 |

| MD-12 (OC data, from Winblad et al 200711) | ||||||||

| Analysis 3: all trials meeting our inclusion criteria, data from patients with mild disease excluded | ||||||||

| MD-029 (LOCF data) | SMD=−0.20 (−0.32 to −0.09) | 0.0005 | SMD=−0.25 (−0.36 to −0.14) | <0.00001 | SMD=−0.04 (−0.21 to 0.13) | 0.65 | SMD=−0.17 (−0.32 to −0.03) | 0.02 |

| MD-12 (OC data, from Winblad et al 200711) | ||||||||

| MD-5015 (LOCF data) | ||||||||

AD, Alzheimer's disease; LOCF, last observation carried forward; OC, observed case; SMD, standardised mean difference; WMD, weighted mean differences.

Figure 1.

Clinical global (CIBIC-plus). ChEI, cholinesterase inhibitor; ER, extended release; LOCF, last observation carried forward; OC, observed case; SMD, standardised mean difference.

Figure 2.

Cognition (ADAS-Cog and SIB). ChEI, cholinesterase inhibitor; ER, extended release; LOCF, last observation carried forward; OC, observed case; SMD, standardised mean difference.

Figure 3.

Function (ACDS-ADL19 and ADCS-ADL23). ChEI, cholinesterase inhibitor; ER, extended release; LOCF, last observation carried forward; OC, observed case; SMD, standardised mean difference.

Figure 4.

Behaviour and mood (NPI). ChEI, cholinesterase inhibitor; ER, extended release; LOCF, last observation carried forward; OC, observed case; SMD, standardised mean difference.

Discussion

This systematic review and meta-analysis suggests a small but significant benefit of memantine combination therapy on cognitive, global and behaviour measures, but not on function/ADL, when data from all included trials, including one trial of ER memantine, were pooled. When data from the trials included in the TA217 meta-analysis, but from patients with moderate-to-severe disease only, were pooled, there was a small, significant benefit of combination therapy on cognition (SMD=0.29). This effect size is comparable to that seen for memantine monotherapy. However, since the impact on clinical global impression depends on exactly which studies are included, and there is no benefit on function, the clinical relevance of combination therapy is not robustly demonstrated.

Clinical data from a negative 1-year trial, which would have been available at the time of the NICE meta-analysis, remain unpublished. The DOMINO study17 is due to report shortly. Whether pooling of these 1-year studies would show a robust effect on clinical global remains to be seen.

Data for patients with moderate AD from one trial10 were only available as observed case data,11 and it was necessary to pool these with the last observation carried forward data from the other trials,9 15 which is not methodologically ideal. In the full Cochrane review, this strategy was shown to have no material effect on results. The last observation carried forward treatment of missing data is a conservative approach because dropout rates are equivalent or slightly favour memantine. Consideration of the cost-effectiveness of combination AChEI and memantine was outside the scope of this review.

To the extent that we found a significant benefit of combination therapy on cognition, our analyses of the available data contrast with the findings of the TA217 report,8 which found no evidence of additional benefit of combination therapy. The explanations given by the Peninsula Technology Assessment Group (PenTAG) for not pooling data from the same clinical domain (“it is not valid to synthesise these data on their original scales”8) or for not restricting analyses to data from the licensed patient subgroup (“The upper range of the MMSE scores for the participants of this study was 20.37… …this was only minimally over the threshold of 20 (so we) include(d) this study…”)20 remain controversial.

The inclusion of unpublished registry data on the ER preparation extends the evidence of benefit of combination therapy at 6 months. The dose of 28 mg memantine in this preparation was designed to be equivalent to 20 mg daily of the currently marketed preparation.21 However, the trend for an adverse effect on ADL may account for the fact that these data have not been published in peer review literature. Although there is biological plausibility to the possibility of dose-related adverse effects of memantine22 and memantine is associated with more rapid neurological decline in cognitively impaired patients with multiple sclerosis,23 24 memantine is well tolerated over 6 months, with slightly fewer dropouts in the memantine than placebo arms, and long-term open-label follow-up studies do not suggest an obvious safety signal.25–27 There are no long-term, randomised placebo-controlled studies to address this issue directly.

Nevertheless, we find the benefit of combination therapy to be less convincing than other reviewers,6 primarily because important data are missing from registry posting of trial results. Posting of clinical data is not mandatory for trials sponsored by companies who are not the Marketing Authorisation Holder in the USA. However, the fact that clinical data have not been released from the 12-month trial, Lu10112,16 is disturbing for two reasons. First, cerebral atrophy rates were greater in those taking combination therapy than in those taking memantine alone.19 While the presented analysis suggests that this unexpected finding of increased atrophy was attributable to the AChEI rather than the memantine, there is no information about whether this is reflected in the clinical domains. Second, the reason given for not posting the clinical data is revealing: sponsors who are not marketing authorisation holders in the USA are not obligated by US public law 110-85. This law mandates the posting of defined clinical data items on registries within a year of study completion.

The greatest benefit of registries is ensuring the timeliness of the release of results. Without this, there are obvious incentives to delay the release of negative data until as close to the end of patent life as possible. However, registries are likely to become the preferred repository of incomplete or negative data. This makes it particularly important that harmonising legislation specifies in detail which clinical data must be posted. Furthermore, until there is harmonisation onto a single registry, such as clinicaltrials.gov, systematic reviews should routinely include comprehensive searches across all registries.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We gratefully acknowledge the support of Sue Marcus and Anna Noel-Storr of CDCIG for their support in the production of the review.

Footnotes

To cite: Farrimond LE, Roberts E, McShane R. Memantine and cholinesterase inhibitor combination therapy for Alzheimer's disease: a systematic review. BMJ Open 2012;2:e000917. doi:10.1136/bmjopen-2012-000917

Contributors: LEF and RM contributed to drafting, analysis and design. ER extracted data and contributed to drafting and conclusions. RM is the guarantor.

Funding: This research received no specific grant from any funding agency in the public, commercial or not-for-profit sectors.

Competing interests: None.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data sharing statement: As this is a systematic review, there are no original data.

References

- 1.EMEA Committee for Medicinal Products for Human Use October 2005 Plenary Meeting Monthly Report. European Medicines Agency Website. http://www.emea.europa.eu/pdfs/human/press/pr/36234805en.pdf (accessed 17 Nov 2005).

- 2.National Institute for Clinical Excellence (NICE) Donepezil, Galantamine, Rivastigmine and Memantine for the Treatment of Alzheimer's Disease. NICE Technology Appraisal Guidance 217 (Review of NICE Technology Appraisal Guidance 111). National Institute for Clinical Excellence, 2011. http://publications.nice.org.uk/donepezil-galantamine-rivastigmine-and-memantine-for-the-treatment-of-alzheimers-disease-ta217/guidance (accessed 23 Mar 2012). [Google Scholar]

- 3.Institute for Quality and Efficiency in Healthcare (IQWiG) Memantine in Alzheimer's Disease. Executive Summary of Final Report A05–19C. Institute for Quality and Efficiency in Healthcare (IQWiG), 2009. https://www.iqwig.de/download/A05-19C_Executive_Summary_Memantine_in_Alzheimers_disease.pdf (Translation of the executive summary of the final report “Memantin bei Alzheimer Demenz”) (accessed 23 Mar 2012). [Google Scholar]

- 4.Institute for Quality and Efficiency in Health Care (IQWiG) Federal Joint Committee. Responder Analyses on Memantine in Alzheimer's Disease: Executive Summary of Rapid Report A10–06. Institute for Quality and Efficiency in Healthcare (IQWiG), 2011. https://www.iqwig.de/download/A10-06_Executive-summary_Responder_analyses_on_memantine_in_Alzheimers_disease.pdf (accessed 23 Mar 2012). [Google Scholar]

- 5.Institute for Quality and Efficiency in Healthcare (IQWiG) Press Release: Memantine in Alzheimer's Disease: Reliable Analyses are Required. Institute for Quality and Efficiency in Healthcare (IQWiG), 2010. https://www.iqwig.de/memantine-in-alzheimer-s-disease-reliable.1079.en.html (accessed 23 Mar 2012). [Google Scholar]

- 6.Patel L, Grossberg GT. Combination therapy for Alzheimer's disease. Drugs Aging 2011;28:539–46 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Schneider LS, Dagerman KS, Higgins JPT, et al. Lack of evidence for the efficacy of memantine in mild Alzheimer disease. Arch Neurol 2011;68:991–8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bond M, Rogers G, Peters J, et al. The Effectiveness and Cost-Effectiveness of Donepezil, Galantamine, Rivastigmine and Memantine for the Treatment of Alzheimer's Disease (Review of TA111): A Systematic Review and Economic Model. NIHR HTA Programme Project Number 09/87/01. National Institute for Clinical Excellence, 2010. http://guidance.nice.org.uk/TA/WaveR111/1/AssessmentReport (accessed 23 Mar 2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Tariot P, Farlow M, Grossberg T, et al. For the memantine study group. Memantine treatment in patients with moderate to severe Alzheimer disease already receiving donopezil. A randomized controlled trial. JAMA 2004;291:317–24 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Porsteinsson AP, Grossberg GT, Mintzer J, et al. Memantine treatment in patients with mild to moderate Alzheimer's disease already receiving a cholinesterase inhibitor: a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Curr Alzheimer Res 2008;5:83–9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Winblad B, Jones RW, Wirth Y, et al. Memantine in moderate to severe Alzheimer's disease: a meta-analysis of randomised clinical trials. Dement Geriatr Cogn 2007;24:20–7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.The Cochrane Dementia and Cognitive Improvement Group (CDCIG) ALOIS: A Comprehensive Register of Dementia Studies. ALOIS; http://www.medicine.ox.ac.uk/alois/ (accessed 23 Mar 2012). [Google Scholar]

- 13.McShane R, Marcus S; Cochrane Dementia and Cognitive Improvement Group About The Cochrane Collaboration (Cochrane Review Groups (CRGs). Cochrane Dementia and Cognitive Improvement Group (CDCIG), 2010:4 http://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/o/cochrane/clabout/articles/DEMENTIA/frame.html (accessed 23 Mar 2012). [Google Scholar]

- 14.Review Manager (RevMan) [Computer Program]. Version 5.0. Copenhagen, Denmark: The Nordic Cochrane Centre, The Cochrane Collaboration, 2008 [Google Scholar]

- 15.Forest Laboratories Study No MEM-MD-50: A Randomized, Double-Blind, Placebo-Controlled Evaluation of the Safety and Efficacy of Memantine in Patients with Moderate-to-Severe Dementia of the Alzhiemer's Type. Forest Laboratories Clinical Trials Registry, 2008. http://www.forestclinicaltrials.com/CTR/CTRController/CTRViewPdf?_file_id=scsr/SCSR_MEM-MD-50_final.pdf (accessed 23 Mar 2012). [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lundbeck Trials Clinical Trial Report Summary: Study 10112. A 1-Year Randomised, Double-Blind, Placebo-Controlled Study to Evaluate the Effects of Memantine on the Rate of Brain Atrophy in Patients With Alzheimer's Disease. H. Lundbeck A/S, 2012. http://www.lundbecktrials.com/Data/PDFs/10112_Final%20CTRS_28May2010.pdf (accessed 23 Mar 2012). [Google Scholar]

- 17.Study ID: NCT00866060 Donepezil and Memantine in Moderate to Severe Alzheimer's Disease (DOMINO-AD). Clinicaltrials.gov. http://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/NCT00866060?term=DOMINO&rank=3 (accessed 14 Aug 2011).

- 18.Forest Laboratories Forest and Merz Announce FDA Approval of NAMENDA XR for the Treatment of Moderate to Severe Dementia of the Alzheimer's Type. Forest Laboratories, Inc, 2010. http://news.frx.com/press-release/product-news/forest-and-merz-announce-fda-approval-namenda-xr-treatment-moderate-sever (accessed 23 Mar 2012). [Google Scholar]

- 19.Wilkinson D, Fox N, Barkhof F, et al. Evaluating the effect of memantine on the rate of brain atrophy in patients with Alzheimer's disease: a multicentre imaging study using a patient enrichment strategy. Poster Presented at: 14th International Congress of the International Psychogeriatric Association; 1–5 September 2009, Montréal, Canada: H. Lundbeck A/S, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Peninsula Technology Assessment Group (PenTAG), University of Exeter AChEIs and Memantine for Alzheimer's Disease: PenTAG Responses to Consultee Comments. National Institute for Clinical Excellence; http://www.nice.org.uk/nicemedia/live/12248/51068/51068.pdf (accessed 17 Aug 2010). [Google Scholar]

- 21.Periclou A, Hu Y. Extended-release memantine capsule (28 mg, once daily): a multiple dose, open-label study evaluating steady-state pharmacokinetics in healthy volunteers [abstract from poster presentation]. Presented at the 11th International Conference on Alzheimer's Disease; 26–31 July 2008. Chicago, IL, USA: Forest Laboratories Inc; 2008 [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hardingham GE, Bading H. Synaptic versus extrasynaptic NMDA receptor signalling: implications for neurodegenerative disorders. Nat Rev Neurosci 2010;11:682–96 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lovera JF, Frohman E, Brown TR, et al. Memantine for cognitive impairment in multiple sclerosis: a randomized placebo-controlled trial. Mult Scler 2010;16:715–23 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Villoslada P, Arrondo G, Sepulcre J, et al. Memantine induces reversible neurologic impairment in patients with MS. Neurology 2009;72:1630–3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Reisberg B, Doody R, Stoffler A, et al. A 24-week open-label extension study of memantine in moderate to severe Alzheimer disease. Arch Neurol 2006;63:49–54 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Forest Laboratories Inc An Open-Label Evaluation of the Safety of Memantine in Patients with Moderate-to-Severe Dementia of the Alzheimer's Type. Forest Laboratories Clinical Trials Registry, 2005. http://www.forestclinicaltrials.com/CTR/CTRController/CTRViewPdf?_file_id=scsr/SCSR_MEM-MD-51_final.pdf (accessed 23 Mar 2012). [Google Scholar]

- 27.Forest Laboratories Inc An Open-Label Extension Study Evaluating the Safety and Tolerability of Memantine in Patients with Moderate-to-Severe Dementia of the Alzheimer's Type. Forest Laboratories Clinical Trials Registry, 2009. http://www.forestclinicaltrials.com/CTR/CTRController/CTRViewPdf?_file_id=scsr/SCSR_MEM-MD-54_final.pdf (accessed 23 Mar 2012). [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.