Abstract

Our aim was to investigate two personality traits (i.e., stoicism and sensation seeking) that may account for well-established gender differences in suicide, within the framework of the interpersonal theory of suicide. This theory proposes that acquired capability for suicide, a construct comprised of pain insensitivity and fearlessness about death, explains gender differences in suicide. Across two samples of undergraduates (N = 185 and N = 363), men demonstrated significantly greater levels of both facets of acquired capability than women. Further, we found that stoicism accounted for the relationship between gender and pain insensitivity, and sensation seeking accounted for the relationship between gender and fearlessness about death. Thus, personality may be one psychological mechanism accounting for gender differences in suicidal behavior.

Keywords: suicide, stoicism, sensation seeking, gender differences

In nearly every nation worldwide, men die by suicide more frequently than women (World Health Organization, 2011), and they represent approximately 80% of the people who die by suicide in the United States each year (National Center for Injury Prevention and Control, 2007). To date, much of the research investigating risk factors for suicide has focused on those that do not offer plausible explanations for gender differences in suicide mortality. For example, major depressive disorder is one of the most widely studied risk factors for suicidal behavior, yet it is substantially less likely to affect men than women (e.g., Nolen-Hoeksema, Grayson, & Larson, 1999). Further, many theoretical accounts of suicide (e.g., Beck, Brown, Berchick, Stewart, & Steer, 1990; Shneidman, 1998) propose identical causal processes for non-fatal and fatal suicidal behavior. This is problematic in that men are far less likely to engage in non-fatal suicidal behavior than women (Nock et al., 2008), which suggests that there may be different causal pathways for lethal versus non-lethal suicidal behavior. There is a clear need to integrate risk factors that are differentially present in men with a comprehensive theory that accounts for the fact that there is a preponderance of women among suicide ideators and attempters and a preponderance of men among suicide decedents. The overarching goal of the current study is to investigate two personality traits that are part of the traditional male gender role (i.e., stoicism and sensation seeking) in the context of a recent theoretical conceptualization of suicidal behavior that proposes different causal processes for lethal versus non-lethal suicidal behavior (i.e., the interpersonal theory of suicide; Joiner, 2005; Van Orden et al., 2010).

The interpersonal theory of suicide introduces a novel construct known as the acquired capability for suicide, which is comprised of two facets: fearlessness about death and physical pain insensitivity. In order to die by suicide, one must face the fearsome prospect of death as well as the physical discomfort necessary to withstand the act of lethal self-injury. Without this requisite degree of fearlessness about death and pain insensitivity, a person will not be capable of inflicting lethal self-harm even if he or she strongly desires to die, according to the interpersonal theory (Joiner, 2005; Van Orden et al., 2010). The acquired capability for suicide is posited to develop relatively independently of desire for suicide. Thus, an individual could have a high level of acquired capability for suicide even if he/she has never experienced suicidal ideation (Smith, Cukrowicz, Poindexter, Hobson, & Cohen, 2010).

Viewed through the lens of the interpersonal theory, gender differences in lethal suicidal behavior may be explained by gender differences in acquired capability. Lower acquired capability for suicide among women may serve to prevent lethal self-harm in many cases, whereas higher acquired capability for suicide among men make it possible for them to enact lethal self-harm in the presence of suicidal desire. Consistent with the notion that gender differences in acquired capability may explain gender differences in suicidal behavior, men score higher than women do on a self-report measure of fearlessness about death (Ribeiro et al., 2012), and there is a large body of literature demonstrating that men have higher physical pain insensitivity than women (e.g., Berkley, 1997).

Despite this initial evidence that men have higher acquired capability for suicide than women, there has not been an empirical examination of personality traits that may explain this gender difference. The capability for fatal self-harm is posited to be acquired over time through repeated exposure and habituation to experiences that are painful and fear inducing (e.g., impulsive behaviors, past suicide attempts). Although exposure to these experiences is considered crucial in order to fully acquire the capability for suicide, the interpersonal theory allows for the possibility that certain personality traits may directly be associated with higher baseline fearlessness about death and/or pain insensitivity (Smith & Cukrowicz, 2010; Van Orden et al., 2010). If particular personality traits are more common in one gender versus another, this would lead to differential risk for developing the acquired capability for suicide and ultimately, differential risk for death by suicide.

Both stoicism and sensation seeking are personality traits that are associated with the traditional male gender role (e.g., Cheng, 1999; David & Brannon, 1976; Roberti, 2004; Zuckerman, Eysenck, & Eysenck, 1978) and share similar features with the acquired capability for suicide. Sensation seeking has been defined as the propensity toward engaging in behaviors that involve risk, including risk of death (e.g., Whiteside & Lynam, 2001; Zuckerman, 1979). Stoicism has been defined as the “denial, suppression, and control of emotion” (Wagstaff & Rowledge, 1995, p. 181). This diminished display of emotions may make an individual more capable of withstanding the emotional and physical pain involved in enacting self-harm.

An emerging literature demonstrates a link between sensation seeking and acquired capability for suicide. Anestis, Bagge, Tull, and Joiner (2011) found that sensation seeking was a significant predictor of self-reported acquired capability for suicide and physical pain insensitivity. Additionally, Bender, Gordon, Bresin, and Joiner (2011) found evidence for both indirect and direct effects of sensation seeking on acquired capability, as measured by self-report. A key limitation of the Bender et al. (2011) study, however, is that they did not examine the influence of gender in their analyses, which is notable given its known association with both sensation seeking and acquired capability for suicide. Further, the self-report measure of acquired capability utilized by both studies conflates fearlessness about death with pain insensitivity; therefore, they were unable to examine specific relationships between the two facets of acquired capability for suicide and sensation seeking.

Although stoicism has not previously been examined in relation to suicidal behavior, there are several studies indicating that there is a link between stoicism and pain insensitivity (Robinson et al., 2001; Wise et al., 2002; Yong, 2006). Witte (2009) found that the related construct of affective intensity (another trait that is associated with male gender; Thompson, Dizen, Berenbaum, 2009) was negatively associated with acquired capability among men, as measured by both self-report and physical pain insensitivity. The distinction between stoicism and affective intensity is that stoicism is defined as the resolve to not display one’s emotional state, whereas affective intensity is the trait-like level of emotional arousal one typically experiences. We propose that stoicism is a more pertinent trait for explaining gender differences in suicide rates than affective intensity because engaging in lethal suicidal behavior would likely result in intense emotional arousal even in individuals with generally low affective intensity. Thus, it is the ability to endure this inevitable distress and fear that makes lethal self-harm possible, not necessarily one’s general tendency for lower emotional arousal.

The major objective of the current study was to test our hypothesis that emotional stoicism and sensation seeking account for the relationship between gender and the acquired capability for suicide. To accomplish this objective, we utilized structural equation modeling to test our hypothesis in two independent samples.

Methods

Sample 1 Characteristics

Sample 1 was comprised of 185 undergraduates (62% male) enrolled at a large university in the Southeastern United States. We oversampled for males starting approximately halfway through the data collection process in order to ensure adequate representation of males in our sample, given that the participant pool is predominantly female. Eighty-nine percent of the participants were non-Hispanic/Latino. The racial breakdown of the sample was as follows: 78% Caucasian, 17% African-American, 3% Asian, 2% American Indian/Alaska Native, and 1% Native Hawaiian/Pacific Islander, with some participants selecting more than one race. The mean age of the sample was 18.7 (SD = 1.1; range = 18-25). Participants were selected to be non-smokers because smoking has been demonstrated to reduce pain sensitivity (Pomerleau, Turk, & Fertig, 1984). In addition, participants were required to not have consumed alcoholic beverages for at least one hour prior to participation and to not have taken any analgesics for at least eight hours before participation. To reduce error due to the possibility of asymmetry in pain sensitivity (Gobel & Westphal, 1987; Pauli, Wiedemann, & Nicola, 1999; Murray & Hagan, 1973), all participants were selected to be right-handed, and all pain threshold measurements were conducted on the participants’ right hands. Five smokers were excluded, and one participant was excluded for taking an analgesic within eight hours of participation.

Although not included in our statistical model, we administered the Beck Suicide Scale (BSS; Beck and Steer, 1991) for descriptive purposes. Scores on items 1-19 of this measure can range from 0-38, with higher scores indicating more severe suicidal ideation. As would be expected in an unselected undergraduate sample, participants did not endorse severe levels of suicidal ideation. Ninety percent of our sample had a score of zero on the BSS, with all but one participant having a score of six or below. Beck and Steer do not provide clinical cutoffs for this measure; however, scores below six indicate minimal suicidality.

Sample 2 Characteristics

Sample 2 consisted of 378 undergraduate students from a university in the Midwestern region of the United States. The sample was 44% male and 52% female; gender was missing for 15 participants (4%). We excluded the 15 participants for whom gender was missing, as our method of addressing missing data (i.e., direct maximum likelihood, described in more detail below) cannot compensate for missing predictor variables. Thus, our final sample consisted of 363 participants. The majority was not Hispanic/Latino (97%). The racial composition of the sample, with some participants selecting more than one race, was: 85% Caucasian, 5% African-American/Black, 11% Asian, 2% American Indian/Alaska Native, and 0.3% Native Hawaiian/Pacific Islander. The mean age of the participants was 19.7 (SD = 2.9; range = 18-39). Similar to Study 1, participants were non-smokers, right-handed, and were instructed to refrain from consumption of alcoholic beverages or analgesics for eight hours prior to the study. As in to Sample 1, scores on the BSS (range = 0-20) were suggestive of minimal suicidality, with 93% of the sample scoring a 0 on this measure, and 99% scoring a 6 or below.

Measures

Fearlessness about death

Seven items were selected from the Acquired Capability for Suicide Scale (Van Orden et al., 2008), which is a self-report measure in a five-point Likert scale format. Our selection of these seven items was based on a recent factor analytic study (Ribeiro et al., 2012), which demonstrated that these items have appropriate convergent and discriminant validity and that this measure is invariant across males and females. In the current study, each item was used as an observed indicator of a latent fearlessness about death factor. Internal consistency in both samples was adequate (Cronbach’s alpha = .86 in Sample 1 and .75 in Sample 2). Data were available for all 185 participants for these items in Sample 1, and in Sample 2, data were available for 346 participants (95% of the sample).

Pressure Pain threshold

In Sample 1, Physical pain threshold was measured using a pressure algometer (Type II, Somedic Inc., Solletuna, Sweden). To assess pain threshold, the experimenter used the algometer to apply pressure to the index finger of the participant’s right hand. Participants were instructed to say pain when they first felt pain. At this point, the experimenter immediately retracted the algometer, which provides a digital output with the amount of pressure (in kilopascals) applied at the moment of retraction. Each participant completed five trials of pain threshold, with 90 seconds between each interval to reduce the impact of habituation (Orbach, Mikulincer, King, Cohen, & Stein, 1997). Each measurement was utilized as an indicator for a latent pain insensitivity factor. Internal consistency in our sample was good (Cronbach’s alpha = .95). Pain threshold data were available for 166 (89.7%) of our participants due to periodic malfunctioning of the algometer. This was virtually always due to the batteries needing to be replaced, which required servicing by technical support staff.

Although some studies have found that experimenter gender interacts with participant gender in the prediction of pain insensitivity (e.g., Kallai, Barke, & Voss, 2004), this was not the case in our sample. Neither the main effect of experimenter gender F [1, 165] = 0.47, p = .49) nor the interaction between experimenter and participant gender F [1, 165] = 1.37, p = .24) was a statistically significant predictor of pain threshold. Therefore, we did not control for experimenter gender in our analyses.

Thermal Pain threshold

In Sample 2, the NeuroSensory Analyzer (TSA-II, Medoc, Durham, North Carolina) was utilized to assess pain threshold. It is a computerized pain perception assessment device that utilizes a thermode to administer heat-induced pain. The thermode was placed beneath the first knuckle of the index finger on the right hand. For each trial, participants were instructed to depress a computer mouse button when they first felt pain. Once each trial started, the temperature level of the thermode increased at a rate of 1° C per second until it reached a temperature of 50.5° C or the participant pressed the mouse button. The gender of the experimenter did not appear to impact the pain ratings in the form of a main effect (F = 1.04 [1, 349], p = .31) nor did it interact with the gender of the participant to predict pain ratings (F = 0.44 [1, 349]; p = .51). Cronbach’s alpha for this sample was .95, and complete pain threshold data were available for 356 participants (98%). As with Sample 1, each trial was used as an indicator of a pain insensitivity latent variable.

Liverpool Stoicism Scale (LSS; Wagstaff & Rowledge, 1995)

The LSS is a 20-item, self-report questionnaire designed to measure stoicism. All items are formatted in a five-point Likert scale, ranging from strongly disagree to strongly agree. Sample items include I tend not to express my emotions and Expressing one’s emotions is a sign of weakness. Higher scores indicate a higher level of stoicism. Murray et al. (2008) conducted a psychometric investigation of the measure and found good test-retest reliability (r = .82) and internal consistency (Cronbach’s alpha = .83). We found good internal consistency in our sample as well (Cronbach’s alpha = .89 in Sample 1 and .83 in Sample 2). The LSS was only available for 144 (77.8%) of our participants in Sample 1 and for 266 (73%) in Sample 2, as it was added to the battery of questionnaires after data collection had already begun.

UPPS (Whiteside & Lynam, 2001)

To measure sensation seeking, we used the Sensation Seeking Subscale of the UPPS Impulsive Behavior Scale, which is comprised of 12 items on a five-point Likert scale. The subscales of the UPPS were derived from extensive exploratory and confirmatory factor analysis and have demonstrated suitable convergent and discriminant validity (Whiteside & Lynam, 2001). Sample items include I quite enjoy taking risks and I generally seek new and exciting experiences and sensations. Internal consistency in our samples was good (Cronbach’s alpha = .89 in Sample 1 and .87 in Sample 2). The Sensation Seeking subscale was available for 100% of our participants in both samples.

Procedure

Data collection procedures were similar for both samples and were approved by each university’s Institutional Review Board. Participants signed up online to participate in the research study for course credit. After giving informed consent, participants either completed the self-report questionnaires or the pain threshold task. The order that they completed these tasks was counterbalanced. We ran a series of one-way ANOVAs with condition as the independent variable and our variables of interest as the dependent variables. There was no effect of condition on any of our variables of interest in either sample (p’s all greater than .07 with the vast majority greater than .10). Thus, we did not control for counterbalancing condition in our analyses. All participants were provided with a list of mental health resources and were debriefed after their participation.

Data analytic strategy

Descriptive statistics for all observed variables in both samples can be found in Table 1. The majority of our variables approximated a normal distribution. Although there were a few exceptions to this general rule, we opted to use the maximum likelihood estimator in our analyses, as the non-normality seen in our variables was not extreme and was limited to the measurement of pain threshold. We utilized Mplus Version 6 (Muthen & Muthen, 1998-2010) for our main analyses.

Table 1.

Descriptive Statistics for Observed Variables in Samples 1 & 2

| Sample 1 | Sample 2 | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Variable | n | M (SD) | Range | Skew (SE) | n | M (SD) | Range | Skew (SE) |

| ACSS1 | 185 | 3.14 (1.34) | 1-5 | -0.14 (0.18) | 346 | 3.01(1.35) | 1-5 | -0.09 (0.13) |

| ACSS2R | 185 | 2.98 (1.29) | 1-5 | 0.10 (0.18) | 346 | 3.28 (1.31) | 1-5 | -0.18 (0.13) |

| ACSS3R | 185 | 3.40 (1.24) | 1-5 | -0.30 (0.18) | 346 | 3.40 (1.35) | 1-5 | -0.36 (0.13) |

| ACSS4 | 185 | 3.44 (1.25) | 1-5 | -0.28 (0.18) | 346 | 2.97 (1.35) | 1-5 | -0.08 (0.13) |

| ACSS5R | 185 | 3.32 (1.24) | 1-5 | -0.24 (0.18) | 346 | 3.28 (1.27) | 1-5 | -0.28 (0.13) |

| ACSS6 | 185 | 3.06 (1.33) | 1-5 | 0.02 (0.18) | 346 | 2.91 (1.35) | 1-5 | 0.05 (0.13) |

| ACSS7 | 185 | 2.77 (1.24) | 1-5 | 0.09 (0.18) | 346 | 2.88 (1.31) | 1-5 | 0.16 (0.13) |

| Threshold 1 | 166 | 241.11 kPa (162.27) | 51-1663 | 4.59 (0.19) | 356 | 46.12 °C (4.57) | 27-51 | -1.36 (0.13) |

| Threshold 2 | 166 | 216.58 kPa (113.83) | 40-755 | 1.47 (0.19) | 356 | 47.65 °C (3.95) | 28-51 | -1.85 (0.13) |

| Threshold 3 | 166 | 227.64 kPa (122.60) | 54-854 | 1.63 (0.19) | 357 | 48.14 °C (4.07) | 28-51 | -2.58 (0.13) |

| Threshold 4 | 166 | 238.16 (136.86) | 58-1012 | 2.21 (0.19) | 357 | 48.36 °C (3.94) | 29-51 | -2.76 (0.13) |

| Threshold 5 | 166 | 248.32 (147.76) | 47-1012 | 2.13 (0.19) | 356 | 48.70 °C (3.48) | 29-51 | -2.95 (0.13) |

| LSS | 144 | 55.10 (11.57) | 23-89 | -0.14 (0.20) | 266 | 52.30 (10.27) | 28-87 | 0.20 (0.15) |

| SSS | 185 | 41.55 (9.80) | 14-60 | -0.46 (0.18) | 363 | 43.68 (8.96) | 12-60 | -0.43 (0.13) |

Note. ACSS = Acquired Capability for Suicide Scale; LSS = Liverpool Stoicism Scale; SSS = Sensation Seeking Scale; kPa = kilopascals; °C = degrees Celsius.

Reverse-scored.

To determine the pattern of missing data in our samples, we conducted a missing values analysis with SPSS version 19.0. Results from this analysis suggested that our data were either missing at random (MAR; i.e., missingness is associated with variables in the model other than the missing variable) or missing completely at random (MCAR; i.e., missingness is not associated with any variables in the model). Because direct ML has been shown to result in unbiased parameter estimates for data that are MCAR and MAR (Enders, 2010), we opted to use this method to handle missing data in both samples. The proportion of complete data for each pair of variables in both studies ranged in magnitude from 68-100%; simulation studies suggest that this amount of missing data can be handled appropriately with Direct ML (e.g., Enders & Bandalos, 2001). Please see our online supplemental materials for detailed information regarding our analysis of missing data patterns.

We utilized a variety of fit indices to evaluate model fit: χ2, standardized root mean square residual (SRMR), Comparative Fit Index (CFI; Bentler, 1990), Tucker-Lewis Index (TLI; Tucker & Lewis, 1973), and root mean square error of approximation (RMSEA; Steiger, 1990). Model fit was considered adequate if RMSEA fell between .06-.08 (Browne & Cudeck, 1993; MacCallum et al., 1996), CFI and TLI values were between .90-.95 (Bentler, 1990), and SRMR values were .08 or below (Hu & Bentler, 1999).

The current study had three main aims. First, we aimed to replicate findings that men have higher levels of both facets of acquired capability (i.e. pain insensitivity and fearlessness about death). Second, we aimed to determine whether the relationship between gender and acquired capability is explained by sensation seeking and emotional stoicism. We hypothesized that there would be an indirect effect of gender on each facet of acquired capability for suicide, through the personality traits of sensation seeking and emotional stoicism (i.e., statistical mediation). Last, we aimed to determine whether sensation seeking and emotional stoicism are differentially related to fearlessness about death and pain insensitivity. Absent prior research on the two facets of acquired capability and their relationship among other factors, we deemed this aim as exploratory in Sample 1, with the goal of replicating any obtained findings in Sample 2.

There are several different tactics that be utilized to test statistical mediation. Although Baron and Kenny’s (1986) causal chain approach is one of the most common approaches in the social sciences, it has not typically performed well in simulation studies (e.g., MacKinnon, Lockwood, Hoffman, West, & Sheets, 2002) compared to other approaches. Unlike Baron and Kenny’s approach, most other strategies for testing mediation focus on testing whether there is a non-zero indirect effect of the predictor variable on the criterion variable through the mediator (Preacher & Hayes, 2008). There are multiple formulas that can be utilized to estimate the standard error of the product of coefficients. We opted to use the one that performs the best in simulation studies, which is known as the bias-corrected bootstrapping procedure (BC bootstrapping). This procedure re-samples (with replacement) repeatedly from the data set and estimates the indirect effect with each re-sampling. This allows for the approximation of the sampling distribution of the indirect effect, making it possible to calculate confidence intervals. We followed Preacher and Hayes’ (2008) recommendation to conduct 5,000 re-samplings.

Results

Preliminary analyses

See Tables S1 and S2 in the online supplemental materials for bivariate correlations between all observed indicators in our models. First, we opted to conduct a CFA of the two latent variables in our model (i.e., fearlessness about death and pain insensitivity). All indicators were congeneric, and we did not estimate covariance between any of the residuals. In Sample 1, our model fit was generally adequate (χ2 = 120.22, df = 53, p < .001; RMSEA = .08 CFI = .96, TLI = .95; SRMR = .05). In contrast, in Sample 2 this initial model demonstrated poor fit according to most (χ2 = 333.35, df = 53, p < .001; RMSEA = .12; TLI = .88;), but not all (CFI = .90, SRMR = .05) of our fit indices. Examination of the modification indices for areas of strain in the model revealed a large value (i.e. χ2 =176.47), suggesting improved fit if we were to estimate the correlation between pain threshold 1 and threshold 2. Rather than making this modification to the model, which would have increased its complexity, we opted to drop threshold 1 from our analyses and to use threshold measurements 2-5 as indicators of our pain insensitivity latent construct. Doing so resulted in a model with adequate fit (χ2 = 162.56, df = 43, p < .001; RMSEA = .09; CFI = .95; TLI = .93; SRMR = .05).

Examination of the model parameters in both samples revealed that, with the exception of ACSS 4 (It does not make me nervous when people talk about death; standardized loading = .23 in Sample 2), all observed indicators had standardized loadings that were greater than 0.30 in magnitude, and all loadings were statistically significant. R-square values (i.e., communalities) ranged from .06-.88, the majority of which were greater than .32. The correlation between the latent variables was statistically significant but modest in magnitude in Sample 1 (r = 0.22, p = .01) and was not statistically significant in Sample 2 (r = 0.05, p = .42).

Although not necessary in order to demonstrate statistical mediation (LeBreton, Wu, & Bing, 2009), we ran a model with to examine the total effect of gender (males = 0; females = 1) on the latent variables (i.e. fearlessness about death and pain insensitivity). This model demonstrated adequate fit in both samples (Sample 1 χ2 = 142.46, df = 63, p < .001; RMSEA = .08, CFI = .95, TLI = .94, SRMR = .05; Sample 2 χ2 = 177.91, df = 52, p < .001; RMSEA = .08, CFI = .95, TLI = .93, SRMR = .05). Because gender is a binary variable, we report the standardized, as opposed to completely standardized, parameter estimates (designated as StdY in Mplus; Muthen & Muthen, 1998-2010). This means that paths between gender and other variables in the model represent differences in standardized scores between males and females and may have values greater than 1.0 (B. Muthen, personal communication, February 17, 2011). As anticipated, gender was significantly associated with fearlessness about death (Sample 1 standardized beta = -.69, p < .001; Sample 2 standardized beta = -.33, p <.01) and pain insensitivity (Sample 1 standardized beta = -.76, p < .001; Sample 2 standardized beta = -.38, p < .001), with men displaying significantly higher levels of both.

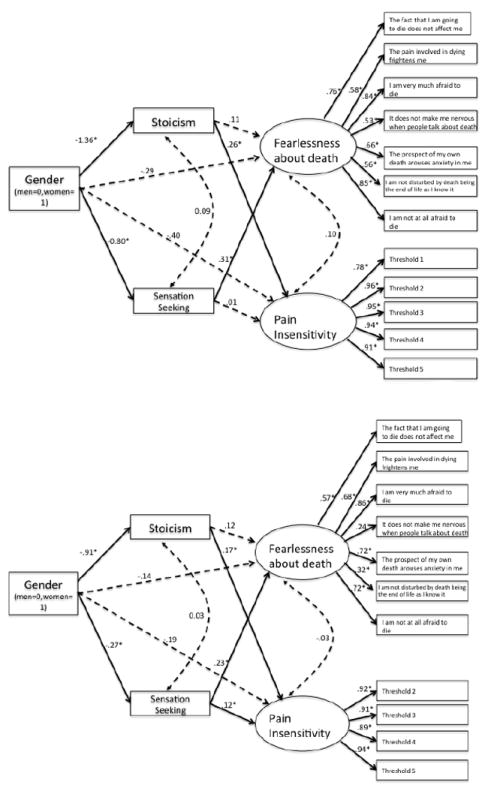

Sample 1 Indirect Effects Model1

To accomplish our primary aim, we constructed a model that examined the indirect effects of gender on both facets of acquired capability, through sensation seeking and stoicism (see Figure 1). To handle scale dependency in this model, we used the indicators with the largest r-square from the measurement model as marker variables. Our model fit was adequate (χ2 = 168.33, df = 83, p < .001; RMSEA = .08, TLI = .94, CFI = .95, SRMR = .05).

Figure 1.

Structural equation model for Sample 1 (top) and Sample 2 (bottom), depicting the indirect relationship between gender and fearlessness about death and pain threshold. Parameters in the model represent standardized coefficients (StdY in Mplus). Although they were estimated in our model, we do not present residual variances in order to simplify the visual presentation. *p < .05. Dashed lines represent paths that are not statistically significant.

In Table 2, we provide unstandardized and standardized values for the direct, total indirect, and specific indirect effects of our model, along with 95% confidence intervals around these parameters. Unstandardized and standardized values for all parameters in this model can be found in our supplemental materials (Table S3). As predicted, there were significant total indirect effects of gender on both latent variables. More specifically, there was a statistically significant indirect effect from gender on fearlessness about death through sensation seeking (standardized indirect effect = -.25, p < .01) and a statistically significant indirect effect from gender on pain insensitivity through stoicism (standardized indirect effect = -.35, p =.02). After controlling for stoicism and sensation seeking, neither the direct path from gender to fearlessness about death nor from gender to pain insensitivity was statistically significant (p’s >.10). This model accounted for 20% of the variance in fearlessness about death and 17% of the variance in pain insensitivity.

Table 2.

Unstandardized and Standardized Total indirect, specific indirect, and direct effects for the SEM Model for Samples 1 and 2

| SAMPLE 1 | SAMPLE 2 | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Estimate (95% CI) | S.E. | StdY | p | Estimate (95% CI) | S.E. | StdY | p | |

| Effects from Gender to Fearlessness about | ||||||||

| Death | ||||||||

| Direct | -0.31 (-0.75 to 0.10) | 0.22 | -.29 | .16 | -0.13 (-0.39 to 0.12) | 0.13 | -.14 | .30 |

| Total Indirect | -0.41 (-0.74 to -0.10) | 0.16 | -.39 | .01 | -0.16 (-0.32 to -0.03) | 0.07 | -.18 | .02 |

| Specific Indirect for Stoicism | -0.16 (-0.46 to 0.13) | 0.15 | -.15 | .30 | -0.11 (-0.25 to 0.01) | 0.06 | -.11 | .11 |

| Specific Indirect for Sensation Seeking | -0.26 (-0.44 to -0.13) | 0.08 | -.25 | <.01 | -0.06 (-0.13 to -0.02) | 0.03 | -.06 | .04 |

| Effects from Gender to Pain Insensitivity | ||||||||

| Direct | -43.35 (-92.89 to 23.45) | 29.47 | -.40 | .14 | -0.62 (-1.42 to 0.22) | 0.41 | -.19 | .14 |

| Total Indirect | -39.15 (-78.34 to -9.59) | 17.20 | -.36 | .02 | -0.61 (-1.04 to -0.27) | 0.19 | -.19 | <.01 |

| Specific Indirect for Stoicism | -38.05 (-79.15 to -10.83) | 16.79 | -.35 | .02 | -0.50 (-0.90 to -0.16) | 0.19 | -.16 | <.01 |

| Specific Indirect for Sensation Seeking | -1.10 (-15.47 to 12.81) | 7.31 | -.01 | .88 | -0.11 (-0.29 to -0.01) | 0.07 | -.03 | .10 |

Sample 2 Indirect Effects Model

Next, we sought to replicate the finding that gender would exert an indirect effect on fearlessness of death via sensation seeking and would influence pain insensitivity via stoicism. Our model fit was adequate (χ2 = 209.62, df = 70, p < .001; RMSEA = .07; CFI = .94, TLI = .92; SRMR = .05); see Figure 1 for a graphical depiction of this model.

In Table 2, we provide unstandardized and standardized values for the direct, total indirect, and specific indirect effects of our model, along with 95% confidence intervals around the unstandardized effects. Unstandardized and standardized values for all parameters in this model can be found in our supplemental materials (Table S3). Similar to Sample 1, the indirect effects of gender on fearlessness about death through sensation seeking and gender on pain insensitivity through emotional stoicism were both statistically significant. One relatively minor difference compared to sample 1 is that the relationship between sensation seeking and pain insensitivity in Sample 2 was statistically significant; however, the magnitude of this association was small, and the indirect effect from gender on pain insensitivity through sensation seeking was not statistically significant. This model accounted for 9% of the variance in fearlessness about death and 7% of the variance in pain insensitivity.

Alternative Model

In an SEM framework, it is important to consider plausible alternative models that may account for our pattern of results. One such alternative model is a model that proposes pain insensitivity as a mediator between gender and our other three variables (i.e., sensation seeking, stoicism, and fearlessness about death). Detailed results from this analysis can be found in the online supplemental materials (Table S4). Briefly, although this model provided an adequate fit to the data in both samples, the direct effect from gender to all of the criterion variables remained statistically significant after accounting for pain insensitivity. This suggests that pain insensitivity did not fully account for the relationship between gender and our outcome variables. This is in contrast to what we found in our proposed model. Further, the only consistent indirect effect found in both samples was for the relationship between gender and stoicism through pain insensitivity. This provides support for a specific relationship between pain insensitivity and stoicism, which is consistent with our original model. Finally, our proposed model accounted for substantially more variance in our main outcome variables of fearlessness about death and pain insensitivity than did this alternative model (see supplemental tables S3 and S4).

General Discussion

The primary objective of the current study was to test our hypothesis that the personality traits of emotional stoicism and sensation seeking account for gender differences in the acquired capability for suicide. We found that men demonstrated significantly greater levels of both facets of acquired capability: fearlessness of death and physical pain insensitivity. However, the effect of gender on these facets was indirect and operated through separate mechanisms, with stoicism accounting for the relationship between gender and pain insensitivity, and sensation seeking accounting for the relationship between gender and fearlessness about death. We consistently found evidence of the specificity of these indirect effects, as stoicism did not account for the relationship between gender and fearlessness about death, and sensation seeking did not account for the relationship between gender and pain insensitivity.

There were few discrepancies between Samples 1 and 2, providing strong support for the role of sensation seeking and stoicism in the development of the acquired capability for suicide. The studies described here are the first that specifically focus on personality traits that explain the relationship between gender and different facets of acquired capability for suicide. Our approach was rigorous in that we utilized different modalities to assess each facet of acquired capability (i.e., behavioral for pain insensitivity and self-report for fearlessness about death). We also employed a data analytic approach that allowed us to examine a comprehensive model with all mediators and criterion variables included.

Though the general pattern of results was similar between the samples, there were some differences. First, ACSS item 4 (It does not make me nervous when people talk about death) did not perform as well in our second sample as it did in our first. We retained it in our model because it did approach a magnitude of .30, was still statistically significant, and performed adequately in prior research (Ribeiro et al., 2012). Second, the two latent factors were not correlated in the second sample. This may be a result of using a thermal pain measurement rather than the pressure pain measurement that was used in Sample 1. Indeed, a recent study (Ribeiro et al., 2012) found that fearlessness about death was more strongly correlated with a measure of pressure pain than a measure of thermal pain. Ribeiro and colleagues noted that pressure pain may be a more suitable indicator of capability for suicide, given that the most common methods of suicide (e.g., jumping from a height, firearm, hanging; Ajaccio-Gross et al., 2008) involve mechanical pain rather than thermal pain. However, even in Sample 1, the correlation between fearlessness about death and pain insensitivity was modest (r = .22), and was not statistically significant after controlling for other variables in the model. Though the interpersonal theory of suicide posits that an individual must have high levels of both fearlessness about death and the ability to tolerate pain to be capable of suicide (Van Orden et al., 2010), these constructs are not necessarily presumed to be highly correlated or components of a higher construct. Finally, the variance accounted for in our outcome variables was smaller in Sample 2 compared to Sample 1. This may have been due to differences between the two samples (e.g., Sample 1 had a larger proportion of males, whereas the opposite is true of Sample 2) or the utilization of a different pain assessment task.

There are several limitations of the current study that warrant discussion. First, in addition to the alternative model we tested, there are other models that are mathematically equivalent or nearly equivalent to our proposed model. Given the cross-sectional nature of our data, we cannot empirically confirm the directionality of the meditational model, which is crucial for establishing a causal relationship (James, Mulaik, & Brett, 1982). Nevertheless, from a logical and theoretical standpoint, we propose that the directionality implied by our model is more plausible than equivalent models. Sensation seeking has been proposed as a longstanding trait with a genetic basis (e.g., Campbell et al., 2010). Similarly, stoicism is proposed as a trait-like construct that is due to early learning history and socialization into the traditional male role (Mogil & Bailey, 2010), with test-retest reliability similar in magnitude to other personality constructs that are generally accepted as trait-like (e.g., Murray et al., 2008). In contrast, fearlessness about death and pain insensitivity are purportedly acquired over time and therefore less stable than typical personality traits (Joiner, 2005; Van Orden et al., 2010). Clearly, however, longitudinal studies are needed in order to confirm this proposition.

Despite our inability to confirm the directionality of these relationships, our study makes a contribution insofar as it establishes that there is a correlational relationship between the constructs that we investigated, which is one of the first steps for establishing a causal relationship (e.g., Haynes, Huland, & Oliveira, 1993). We also have satisfied other criteria for establishing a meditational model, such as replicating the effects across independent samples and demonstrating specificity of the relationship between mediators and outcomes (Hill, 1971; MacKinnon, 2008).

Second, though Van Orden et al. (2010) described tolerance for physical pain as integral to the acquired capability for suicide, we measured pain threshold. Nevertheless, our results are consistent with previous studies that have utilized a pain tolerance task (e.g., Anestis et al., 2011). Third, the magnitude of the relationships and the proportions of variance explained in the factors of acquired capability described here were modest. This may have resulted from our study of a non-clinical sample in which life experiences associated with the development of acquired capability (e.g., trauma, previous suicide attempts) were limited. Fourth, we did not examine these constructs in relation to suicidal behavior due to low levels of suicidality in these non-clinical samples. Nevertheless, our results provide a firm foundation for this crucial next step in the validation of the acquired capability construct. Finally, in both samples, we did not have complete data from all participants. Although Direct ML has been recommended as an optimal approach to handling missing data (Enders, 2010), no methodologist would argue that the use of this technique is preferable to having complete data for all cases. Despite this, we are confident that our results are not solely due to biased parameter estimates, given their consistency across two independent samples with different patterns of missing data.

Despite these limitations, our results have both theoretical and clinical implications. First, our finding that key aspects of the male gender role account for gender differences in acquired capability for suicide serves to inform our understanding of why men die by suicide at such dramatically higher rates than women do. Second, our findings generate testable hypotheses for future examinations of the relationship between these personality traits and suicidal behavior. For example, according to the hypotheses proposed by Van Orden et al. (2010), fearlessness about death has a specific relationship with suicidal intent, whereas pain insensitivity has a specific relationship with medical lethality of a suicide attempt. Our results suggest that sensation seeking should have a significant association with suicidal intent (due to its relationship with fearlessness about death), whereas stoicism should have a significant association with medical lethality of attempt (due to its relationship with pain threshold).

Our findings also inform future research studies on the importance of stoicism and sensation seeking in predicting suicidal behavior in at-risk populations. For example, stoicism may be especially relevant to the etiology of suicide in older adults, as stoicism has been shown to be positively associated with age (Murray et al., 2008), and older adults have the highest suicide rates compared to any other age group (Centers for Disease Control, 2010). Our study also indicates the importance of including stoicism and sensation seeking in suicide risk assessments. Although most suicide risk assessment frameworks emphasize the importance of assessing for impulsivity (e.g., Joiner, Walker, Rudd, & Jobes, 1999; Linehan, 2007), sensation seeking has been proposed as a distinct construct from impulsivity (e.g., Steinberg, 2008) and is not typically included in suicide risk assessments. Our results and the results of Bender et al. (2011) suggest that sensation seeking has a reliable relationship with acquired capability for suicide. Further, Bender et al. (2011) demonstrated that this relationship was more robust than the relationship between acquired capability for suicide and other measures of impulsivity. With regard to stoicism, a great deal of clinical attention tends to be devoted to emotionally dysregulated presentations; our results suggest the importance of attending to the other end of the continuum of affective dysregulation, as a stoical disposition may make it possible for an at-risk individual to engage in lethal suicidal behavior. The current study also has implications for intervention. Although the acquired capability for suicide has been proposed to be stable over time and not amenable to clinical interventions, it is possible that interventions could address stoicism and sensation seeking, thereby mitigating their effect on pain insensitivity and fearlessness about death. Finally, our results have implications for basic personality research on stoicism and sensation seeking, as it adds to the literature of negative behavioral outcomes for these personality constructs. In conclusion, our results provide important preliminary information regarding the link between gender and acquired capability for suicide that are theoretically and clinically important and provide ample avenues for future research on this topic.

Supplementary Material

HIGHLIGHTS.

Men die by suicide more than women do

Acquired capability for suicide (ACS) may explain gender differences in suicide

Stoicism and sensation seeking mediate the relationship between gender and ACS

Acknowledgments

This research was supported, in part, by grant F31 MH077386 from the National Institute of Mental Health to Tracy K. Witte and Thomas E. Joiner, Jr., a grant EPS-081442 from the North Dakota Experimental Program to Stimulate Competitive Research to Kathryn H. Gordon, and grant T32 MH20061 from the National Institute of Mental Health to Yeates Conwell.

Footnotes

In Sample 1, participants also completed a measure of affective intensity. We ran our indirect effects model with the addition of this measure, and results suggested that stoicism, rather than the intensity of affect, accounted for our obtained results. A detailed description of this analysis is available in our online supplemental materials.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Contributor Information

Tracy K. Witte, Department of Psychology, Auburn University

Kathryn H. Gordon, Department of Psychology, North Dakota State University

Phillip N. Smith, Department of Psychology, University of South Alabama

Kimberly A. Van Orden, Department of Psychiatry, University of Rochester Medical Center

References

- Ajdacic-Gross V, Weiss MG, Ring M, Hepp U, et al. Methods of suicide: International suicide patterns derived from the WHO mortality database. Bulletin of the World Health Organization. 2008;86:726–732. doi: 10.2471/BLT.07.043489. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anestis MS, Bagge CL, Tull MT, Joiner TE. Clarifying the role of emotion dysregulation in the interpersonal-psychological theory of suicidal behavior in an undergraduate sample. Journal of Psychiatric Research. 2011;45:603–611. doi: 10.1016/j.jpsychires.2010.10.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baron RM, Kenny DA. The moderator-mediator variable distinction in social psychological research: Conceptual, strategic and statistical considerations. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 1986;51:1173–1182. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.51.6.1173. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beck AT, Brown G, Berchick RJ, Stewart BL, Steer RA. Relationship between hopelessness and ultimate suicide: A replication with psychiatric outpatients. American Journal of Psychiatry. 1990;147:190–195. doi: 10.1176/ajp.147.2.190. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beck AT, Steer RA. Beck Scale for Suicide Ideation. San Antonio: The Psychological Corporation; 1991. [Google Scholar]

- Bender TW, Gordon KH, Bresin K, Joiner TE., Jr Impulsivity and suicidality: The mediating role of painful and provocative experiences. Journal of Affective Disorders. 2011;129:301–307. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2010.07.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bentler PM. Comparative fit indices in structural models. Psychological Bulletin. 1990;107:238–246. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.107.2.238. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berkley KJ. Sex differences in pain. Behavioral and Brain Sciences. 1997;20:371–380. doi: 10.1017/s0140525x97221485. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Browne MW, Cudeck R. Alternate ways of assessing model fit. In: Bollen KA, Long JS, editors. Testing structural equation models. Newbury Park, CA: Sage; 1993. pp. 136–162. [Google Scholar]

- Campbell BC, Dreber A, Apicella CL, Eisenberg DTA, Gray PB, Little AC, Lum JK, et al. Testosterone exposure, domapminergic reward, and sensation-seeking in young men. Physiology and Behavior. 2010;99:451–456. doi: 10.1016/j.physbeh.2009.12.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) Web-based Injury Statistics Query and Reporting System (WISQARS) National Center for Injury Prevention and Control, CDC (producer) 2010 Retrieved from http://www.cdc.gov/injury/wisqars/index.html.

- Cheng C. Marginalized masculinities and hegemonic masculinity: An introduction. Journal of Men’s Studies. 1999;7:295. [Google Scholar]

- David D, Brannon R, editors. The forty-nine percent majority: The male sex role. Reading, MA: Addison-Wesley; 1976. [Google Scholar]

- Enders CK. Applied Missing Data Analysis. New York, NY: The Guilford Press; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Enders CK, Bandalos DL. The relative performance of full information maximum likelihood estimation for missing data in structural equation models. Structural Equation Modeling: A Multidisciplinary Journal. 2001;8:430–457. [Google Scholar]

- Gobel H, Westphal W. Die lateral asymmetrie der menschilchen Schmerzempfindlichkeit. Der Schmerz. 1987;1:114–121. doi: 10.1007/BF02527738. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haynes SN, Huland SE, Oliveira J. Identifying causal relationships in clinical assessment: Treatment implications of psychological assessment. Psychological Assessment. 1993;5:281–291. [Google Scholar]

- Hill AB. Principles of Medical Statistics. 9. New York: Oxford: 1971. [Google Scholar]

- Hu LT, Bentler PM. Cutoff criteria for fit indexes in covariance structure analysis: Conventional criteria versus new alternatives. Structural Equation Modeling. 1999;6:1–55. [Google Scholar]

- James LR, Mulaik SA, Brett JM. Causal analysis: Assumptions, models, and data. Beverly Hills, CA: Sage; 1982. [Google Scholar]

- Joiner TE. Why People Die by Suicide. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Joiner TE, Walker R, Rudd MD, Jobes D. Scientizing and routinizing the assessment of suicdiality in outpatient practice. Professional Psychology: Research and Practice. 1999;30:447–453. [Google Scholar]

- Kallai I, Barke A, Voss U. The effects of experimenter characteristics on pain reports in women and men. Pain. 2004;112:142–147. doi: 10.1016/j.pain.2004.08.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- LeBreton JM, Wu J, Bing MN. The truth(s) on testing for mediation inn the social and organizational sciences. In: Lance CE, Vandenberg RJ, editors. Statistical and Methodological Myths and Urban Legends. New York, NY: Routledge Taylor and Francis Group; 2009. pp. 107–137. [Google Scholar]

- Linehan MM. Imminent suicide risk and serious self-injury protocol. University of Washington; Seattle: 2007. Unpublished manuscript. [Google Scholar]

- MacCallum RC, Browne MW, Sugawara HM. Power analysis and determination of sample size for covariance structure modeling. Psychological Methods. 1996;1:130–149. [Google Scholar]

- MacKinnon DP. Introduction to Statistical Mediation Analysis. New York: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- MacKinnon DP, Lockwood CM, Hoffman JM, West SG, Sheets V. A comparison of methods to test mediation and other intervening variables effects. Psychological Methods. 2002;7:83–104. doi: 10.1037/1082-989x.7.1.83. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mogil JS, Bailey AL. Sex and gender differences in pain and analgesia. Progress in Brain Research. 2010;186:141–157. doi: 10.1016/B978-0-444-53630-3.00009-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murray FS, Hagan BC. Pain threshold and tolerance of hands and feet. Journal of Comparative and Physiological Psychology. 1973;84:639–643. doi: 10.1037/h0034836. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murray G, Judd F, Jackson H, Fraser C, Komiti A, Pattison P, Robins G, et al. Big boys don’t cry: An investigation of stoicism and its mental health outcomes. Personality and Individual Differences. 2008;44:1369–1381. [Google Scholar]

- Muthen LK, Muthen BO. Mplus User’s Guide. Sixth Edition. Los Angeles, CA: Muthen & Muthen; 1998-2010. [Google Scholar]

- National Center for Injury Prevention and Control. United States Injury Deaths and Rates per 100,000. 2007 Retrieved on January 4, 2011, from http://webappa.cdc.gov/cgi-bin/broker.exe.

- Nock MK, Borges G, Bromet EJ, Alonso J, Angermeyer M, Beautrais, Williams D, et al. Cross-national prevalence and risk factors for suicidal ideation, plans, and attempts. The British Journal of Psychiatry. 2008;192:98–105. doi: 10.1192/bjp.bp.107.040113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nolen-Hoeksema S, Grayson C, Larson J. Explaining the gender differences in depressive symptoms. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 1999;77:1061–1072. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.77.5.1061. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Orbach I, Mikulincer M, King R, Cohen D, Stein D. Threshold and tolerance of physical pain in suicidal and nonsuicidal adolescents. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 1997;65:646–652. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.65.4.646. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pauli P, Wiedemann G, Nicola M. Pressure pain thresholds as asymmetry in lef- and right-handers: Associations with behavioural measures of cerebral laterality. European Journal of Pain. 1999;3:151–156. doi: 10.1053/eujp.1999.0108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pomerleau OF, Turk DC, Fertig JB. The effects of cigarette smoking on pain and anxiety. Addictive Behaviors. 1984;9:265–271. doi: 10.1016/0306-4603(84)90018-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Preacher KJ, Hayes AF. Asymptotic and resampling strategies for assessing and comparing indirect effects in multiple mediator models. Behavior Research Methods. 2008;40:879–891. doi: 10.3758/brm.40.3.879. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ribeiro JD, Witte TK, Van Orden KA, Selby EA, Gordon KH, Bender TW, Joiner TE. Fearlessness about death: Psychometric properties and construct validity of the Fearlessness about Death subscale of the Acquired Capability for Suicide Scale. 2012 doi: 10.1037/a0034858. Manuscript submitted for publication. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roberti JW. A review of behavioral and biological correlates of sensation seeking. Journal of Research in Personality. 2004;38:256–279. [Google Scholar]

- Robinson ME, Riley JL, Myers CD, Papas RK, Wise EA, Waxenberg LB, Filingim RB. Gender role expectations of pain: Relationship to sex differences in pain. The Journal of Pain. 2001;2:251–257. doi: 10.1054/jpai.2001.24551. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shneidman ES. Perspectives on suicidology: Further reflections on suicide and psychache. Suicide and Life-Threatening Behavior. 1998;28:245–250. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith PN, Cukrowicz KC. Capable of suicide: A functional model of the acquired capability component of the interpersonal-psychological theory of suicide. Suicide & Life-Threatening Behavior. 2010;30:266–275. doi: 10.1521/suli.2010.40.3.266. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith PN, Cukrowicz KC, Poindexter EK, Hobson V, Cohen LM. The acquired capability for suicide: A comparison of suicide attempters, suicide ideators, and non-suicidal controls. Depression & Anxiety. 2010;27:871–877. doi: 10.1002/da.20701. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Steiger JH. Structural model evaluation and modification: An interval estimation approach. Multivariate Behavioral Research. 1990;25:173–180. doi: 10.1207/s15327906mbr2502_4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Steinberg L. A social neuroscience perspective on adolescent risk-taking. Developmental Review. 2008;28:78–106. doi: 10.1016/j.dr.2007.08.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thompson RJ, Dizen M, Berenbaum H. The unique relations between emotional awareness and facets of affective instability. Journal of Research in Personality. 2009;43:875–879. doi: 10.1016/j.jrp.2009.07.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tucker LR, Lewis C. A reliability coefficient for maximum likelihood factor analysis. Psychometrika. 1973;38:1–10. [Google Scholar]

- Van Orden KA, Witte TK, Gordon KH, Bender TW, Joiner TE. Suicidal desire and the capability for suicide: Tests of the interpersonal-psychological theory of suicidal behavior among adults. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2008;76:72–83. doi: 10.1037/0022-006X.76.1.72. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van Orden KA, Witte TK, Cukrowicz KC, Braithwaite SR, Selby EA, Joiner TE. The interpersonal theory of suicide. Psychological Review. 2010;117:575–600. doi: 10.1037/a0018697. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wagstaff GF, Rowledge AM. Stoicism: Its relation to gender, attitudes toward poverty, and reactions to emotive material. Journal of Social Psychology. 1995;135:181–184. doi: 10.1080/00224545.1995.9711421. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Whiteside SP, Lynam DR. The five factor model and impulsivity: Using a structural model of personality to understand impulsivity. Personality and Individual Differences. 2001;30:669–689. [Google Scholar]

- Wise EA, Price DD, Myers DC, Heft WM, Robinson EM. Gender role expectations of pain: Relationship to experimental pain perception. Pain. 2002;96:335–342. doi: 10.1016/s0304-3959(01)00473-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Witte TK. Impulsivity, affective lability, and affective intensity: Distal risk factors for suicidal behavior (Doctoral dissertation) 2009 Retrieved from Florida State University Electronic Theses, Treatises, and Dissertations database (URN ETD-08262009-130534) [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization. Suicide Rates per 100,000 by Country, Year, and Sex. 2011 Retrieved on January 4, 2011, from http://www.who.int/mental_health/prevention/suicide_rates/en/index.htm.

- Yong HH. Can attitudes of stoicism and cautiousness explain observed age-related variation in levels of self-rated pain, mood disturbance, and functional interference in chronic pain patients? European Journal of Pain. 2006;10:399–407. doi: 10.1016/j.ejpain.2005.05.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zuckerman M, Eysenck S, Eysenck HJ. Sensation seeking in England and America: Cross-cultural, age, and sex comparisons. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 1978;46:139–149. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.46.1.139. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zuckerman M. Sensation seeking: Beyond the optimal level of arousal. Hillsdale, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum; 1979. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.