Abstract

Early afterdepolarizations (EADs) are voltage oscillations that occur during the repolarizing phase of the cardiac action potential and cause cardiac arrhythmias in a variety of clinical settings. EADs occur in the setting of reduced repolarization reserve and increased inward-over-outward currents, which intuitively explains the repolarization delay but does not mechanistically explain the time-dependent voltage oscillations that are characteristic of EADs. In a recent theoretical study, we identified a dual Hopf-homoclinic bifurcation as a dynamical mechanism that causes voltage oscillations during EADs, depending on the amplitude and kinetics of the L-type Ca2+ channel (LTCC) current relative to the repolarizing K+ currents. Here we demonstrate this mechanism experimentally. We show that cardiac monolayers exposed to the LTCC agonists BayK8644 and isoproterenol produce EAD bursts that are suppressed by the LTCC blocker nitrendipine but not by the Na+ current blocker tetrodoxin, depletion of intracellular Ca2+ stores with thapsigargin and caffeine, or buffering of intracellular Ca2+ with BAPTA-AM. These EAD bursts exhibited a key dynamical signature of the dual Hopf-homoclinic bifurcation mechanism, namely, a gradual slowing in the frequency of oscillations before burst termination. A detailed cardiac action potential model reproduced the experimental observations, and identified intracellular Na+ accumulation as the likely mechanism for terminating EAD bursts. Our findings in cardiac monolayers provide direct support for the Hopf-homoclinic bifurcation mechanism of EAD-mediated triggered activity, and raise the possibility that this mechanism may also contribute to EAD formation in clinical settings such as long QT syndromes, heart failure, and increased sympathetic output.

Introduction

Early afterdepolarizations (EADs) can cause lethal arrhythmias in cardiac conditions such as congenital and acquired long QT (LQT) syndromes and heart failure, which are often potentiated by increased sympathetic output (1,2). EADs have been classically attributed to reactivation of the L-type Ca2+ channel (LTCC) as membrane voltage passes through the LTCC window voltage region (∼0 to −40 mV, where steady-state activation and inactivation curves overlap) (3,4–7). If the rate of repolarization is not sufficiently rapid through this voltage range, the LTCC can reactivate, reversing repolarization to produce the EAD upstroke. This scenario typically occurs when the repolarization reserve is reduced (8–11). In this setting, it is intuitively obvious that the increase in the magnitude of inward currents relative to outward currents will cause an increase in the action potential duration (APD) or its ECG analog, the QT interval. An increase in APD is often held to be by itself a marker for pro-arrhythmia. However, EADs are characterized by voltage oscillations, implying that time-dependent factors, such as the time constants of the steady-state activation, inactivation, and recovery from inactivation of the LTCC relative to those of K+ channels, are also critical. Specifically, in order for voltage to oscillate, the time constants of these currents have to be in resonance with each other.

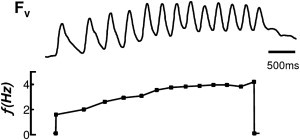

To explore how time- and voltage-dependent factors interact to cause EAD voltage oscillations, we adopted a nonlinear dynamics approach to analyze EAD formation in the Luo-Rudy I (LR1) ventricular action potential (AP) model (12). On the basis of this analysis, we theorized that EADs are generated by a Hopf bifurcation and terminated by a homoclinic bifurcation. The Hopf bifurcation is a dynamical process by which an equilibrium (in this case, the plateau voltage) becomes unstable and begins to oscillate (13), which occurs as the slopes of feedback relations are increased in the presence of an appropriate time delay. For example, the change from the nonoscillatory mode to the oscillatory mode of the sinoatrial nodal pacemaker cell has been described by a Hopf bifurcation (14). Hopf bifurcations are thought to underlie many other biological oscillations, such as the cell cycle (15), glycolytic oscillations (16), and circadian rhythms (17). In the LR1 model, we found that the Hopf bifurcation-mediated voltage oscillations at the plateau potential (i.e., EADs) can occur when the slopes of the LTCC activation and inactivation curves are steep, with properly matched time constants and window LTCC current (12). The homoclinic bifurcation is a parameter point at which the oscillatory orbit collides with the saddle point, resulting in an infinite-period orbit. After the bifurcation point, no oscillatory orbit exists. The Hopf bifurcation initiates the membrane oscillations, causing single or multiple EADs, and as the outward currents slowly activate, the system gradually approaches and passes the homoclinic bifurcation, at which point the voltage fully repolarizes, terminating the EADs. The defining feature of this process is the slowing of frequency, i.e., as the oscillatory orbit approaches the infinite period orbit, the period of the oscillations increases.

In this study, we performed optical mapping experiments on cultured neonatal rat ventricular myocyte (NRVM) monolayers to determine whether EAD-mediated triggered activity in this preparation exhibits features that corroborate the theoretical mechanism described above. We induced EADs by exposing monolayers to the LTCC agonists BayK8644 and isoproterenol. We found that in cardiac monolayers, EADs exhibit the key dynamical signature of the Hopf-homoclinic bifurcation mechanism (12), namely, a gradual slowing of the frequency response before burst termination. Bursts were resistant to Na+ channel blockade (with tetrodotoxin (TTX)), depletion of SR Ca2+ (with caffeine and thapsigargin), and suppressed by Ca2+ channel blockade (with nitrendipine), consistent with the predicted central role of LTCC. Moreover, interventions that delayed entry into the LTCC window region, such as blocking the transient outward K+ channel (Ito) and other K+ currents with 4-aminopyridine (4-AP), or overexpressing a Ca2+-insensitive mutant calmodulin (CaM1234) to suppress LTCC inactivation, also suppressed EAD bursts even though they further prolonged the APD. These experimental findings were reproduced in a detailed cardiac AP model, which revealed that the frequency slowdown and burst termination were due to a slow accumulation of intracellular Na+. These results provide strong experimental evidence that the Hopf-homoclinic bifurcation mechanism of EAD-mediated triggered activity can occur in real cardiac tissue.

Materials and Methods

All protocols used in this study conform to the standards set forth by the National Institutes of Health (NIH) in the Guide for the Care and Use of Animals (NIH publication No. 85-23, revised 1996).

Cell culture

We created monolayers of NRVMs by plating 1 × 106 cells on 21-mm fibronectin-coated plastic coverslips as previously described (18). A representative example of the appearance of myocytes after 11 days in culture is shown in Fig. S1 of the Supporting Material. We confirmed the maturation of SR Ca2+ handling in NRVM cultures by recording Ca2+ transients during pacing in Tyrode solution before and after exposure to 10 mM caffeine, which depletes SR Ca2+ stores. Ca2+ transients were abolished by the addition of caffeine (Fig. S2), consistent with a mature SR Ca2+ handling phenotype, as described previously for NRVM monolayers after several days in culture (19–21).

Optical mapping

Arrhythmias were imaged by optical mapping performed after 11–14 days in culture. Coverslips were visually inspected under a microscope, and monolayers with obvious gaps in confluence and nonbeating cultures were rejected (after 7 d in culture, most NRVMs are quiescent and a dominant pacemaker is responsible for electrical activity in monolayers). The coverslips were then transferred to a custom-designed chamber, stained with 5 μmol/L di-4-ANEPPS (a voltage-sensitive dye) for 5 min or 5 μmol/L Rhod-2 AM (a Ca2+-sensitive dye) for 30 min, and then continuously superfused with warm (36.5°C) oxygenated (normal) Tyrode solution containing (in mM) 135 NaCl, 5.4 KCl, 1.8 CaCl2, 1 MgCl2, 0.33 NaH2PO4, 5 HEPES, and 5 glucose. A unipolar point electrode was used to stimulate the cells.

APs were recorded using either a custom-built contact fluorescence imaging system with 253 recording sites as previously described (18) (Fig. S3) or a CCD-based optical imaging system (Photometrics Cascade 128+, Tucson, AZ), with 128 × 128 spatial resolution at 0.6 to 5 ms per frame. Voltage and Ca2+ signals were acquired continuously over 2–15 min in the absence of pacing or during pacing at <0.5 Hz. Data were stored, displayed, and analyzed using custom software written in Visual C++ (Microsoft), Laboratory VIEW (National Instruments), and MATLAB (The MathWorks, Natick, MA).

Experimental protocols

Mode-2 gating of LTCC was induced by addition of the LTCC agonist BayK8644 (2.5 μM) and the β adrenergic receptor agonist isoproterenol (1 μM) to the perfusate. In some experiments, Na+ channels and LTCC were blocked by addition of 10 μM TTX or 5 μM nitrendipine, respectively, directly to the superfusate. To deplete SR Ca2+, some monolayers were pretreated with 10 mM caffeine and 5 μM thapsigargin for 30 min (22–25). To buffer intracellular Ca2+, some monolayers were incubated with 100 μM BAPTA-AM for 7 min. The relative Ca concentrations under these conditions are shown in Fig. S4. To create intracellular Ca2+ overload without inducing mode-2 gating of LTCC, some monolayers were superfused with Tyrode solution containing 100 μM ouabain and 3.6 mM Ca2+. To block the outward transient K+ current and other K+ currents, some monolayers were superfused with 4-AP (10 mM). To ablate Ca2+-dependent inactivation of the LTCC, some monolayers were preinfected with the adenoviral construct Ad-CaM1234 to overexpress the mutant Ca2+-insensitive calmodulin CaM1234, as previously described (26).

Data analysis

The baseline drift due to photobleaching of the potentiometric dye was reduced by subtracting a third-order polynomial best-fit curve of the optical signals. To reduce noise in the optical signals, a seven-point moving median filter was applied to the detrended data. Animations of electrical propagation were generated from signals that were low-pass filtered between 0 and 100 Hz. The activation time was defined as the instant of maximum positive slope. Burst frequency plots were computed by determining the inverse of time between upstrokes. Pseudo ECGs were computed (using the concept of the lead field) from the potential difference determined between two virtual electrodes positioned 5 mm above diametrically opposite points on the monolayer, and located parallel to the horizontal edge of the recording hexagonal area (27).

Statistics

Data were expressed as the mean ± SD and analyzed using a paired Student's t-test, with p-values < 0.05 considered to be significant.

Computer simulations

For computer simulations we used the ventricular AP model developed by Mahajan et al. (28) with further modifications described in Chang et al. (29). In addition, two linear background currents (ICab and INab) were added, with the corresponding conductances chosen as gB,Ca = 0.0002513 mS/μF and gB,Na = 0.0004 mS/μF, and the maximum rate of electrogenic Na+-K+ pump was decreased to gNaK = 0.8 mS/μF to give a steady-state intracellular sodium concentration of [Na]i = 10 mM. To generate the bursting behavior, we started from the EAD model of Chang et al. (29) and increased the maximum Ca2+ flux of the LTCC by 41% and the maximum conductance of the fast Ito by 45%. Although we did not attempt to reproduce the effects of BayK8644 and isoproterenol in a quantitatively exact manner, our modifications are qualitatively in line with their effects on the LTCC current. Accordingly, to induce EADs in the control model (28), we increased the LTCC current and sped up its kinetics (29). Here, we further increased LTCC to result in EAD burst. In addition, increasing Ito to potentiate burst agrees with our experimental result that blocking the transient outward current suppressed the bursting behavior. A nonlinear instantaneous BAPTA buffer with KBAPTA = 215 μM was added to simulate the presence of BAPTA-AM (see the Supporting Material for the detailed parameter changes and a study of the sensitivity and dependence of the burst duration and frequency on parameter values (Fig. S5)). All simulations were performed using the CVODE time-adaptive solver for stiff equations from the SUNDIALS package (30). The time-adaptive solver guarantees a maximum local error on all state variables, which was set to be smaller than 10−5 in relative value and 10−6 in absolute value.

Results

BayK8644 and isoproterenol induce bursts of EAD-mediated triggered activity

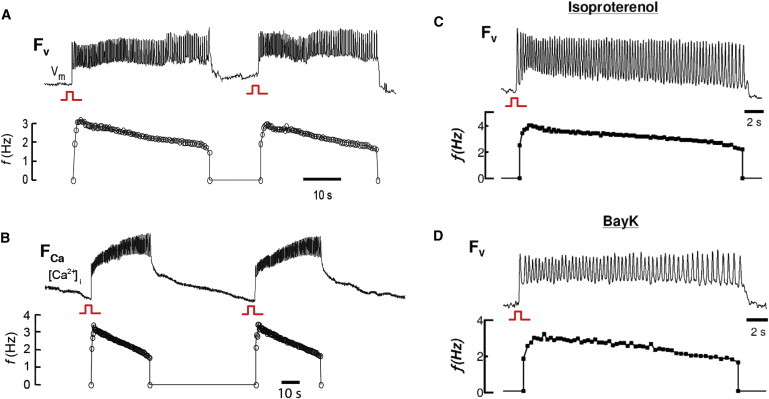

Cultured NVRM monolayers superfused with BayK8644 (2.5 μM) and isoproterenol (1 μM) developed robust synchronized bursts of electrical activity that arose abruptly during slow pacing (<0.04 Hz), as detected by either voltage or Ca2+ imaging (Fig. 1, A and B, and Fig. S2). Bursts were characterized by incomplete repolarization between beats, consistent with EAD-mediated triggered activity. Also consistent with EAD-mediated triggered activity, the bursts were focal, originating at one or more distinct sites and propagating throughout the monolayer (Fig. 2, A and B), resulting in a pseudo-electrocardiogram resembling polymorphic ventricular tachycardia (VT; Fig. 2 C). Burst episodes were self-limited and recurrent, with burst duration averaging 34 s (standard deviation (SD) 23) and the frequency of triggered activity during the burst averaging 2.6 Hz (SD 0.3; n = 9 monolayers). During individual bursts, the frequency of triggered activity decreased gradually to 45 (SD 5) % of the initial frequency (n = 9; Fig. 1 A), a classic dynamical signature of the dual Hopf-homoclinic bifurcation mechanism. Ca2+ imaging of EAD bursts exhibited frequency plots (Fig. 1 B) similar to those recorded by voltage imaging.

Figure 1.

Voltage and Ca2+ bursts induced by BayK8644 and isoproterenol. Voltage and calcium bursts (top panels of A and B, respectively) recorded by voltage (FV) or Ca2+ (FCa) optical mapping in two different monolayers, and their corresponding frequency response plots (lower panels). (C and D) Perfusion with solely isoproterenol (C) or solely BayK8644 (D) induced bursts.

Figure 2.

BayK8644 and isoproterenol induce bursts of focal activity resembling polymorphic VT. (A) Voltage maps of bursting activity reveal repetitive firing of focal activity. (B) A close-up of the initial voltage activity observed in the first burst shown in Fig. 1A, showing burst of EADs. (C) Pseudo-ECG showing polymorphic VT corresponding to the burst in panel B underlain by multiple sites of focal activity (A).

Because BayK8644 and isoproterenol directly or indirectly affect other ionic currents besides LTCC, we also tested both drugs separately. EAD bursts were observed with isoproterenol alone (Fig. 1 C) in three of eight monolayers, and with BayK8644 alone in seven of seven monolayers (Fig. 1 D). In both cases, the bursting frequencies gradually declined before burst termination occurred. Thus, unless BayK8644 and isoproterenol have overlapping off-target effects, these findings implicate altered LTCC gating properties as the common factor by which these drugs induce EAD bursting.

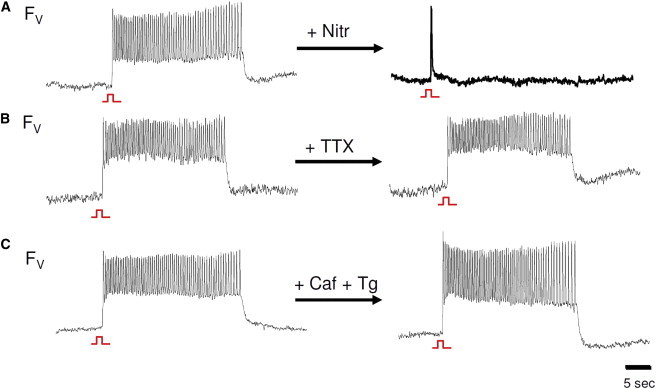

EAD bursts depend on LTCC but not on Na+ channels, SR Ca2+ cycling, or Ca2+ overload per se

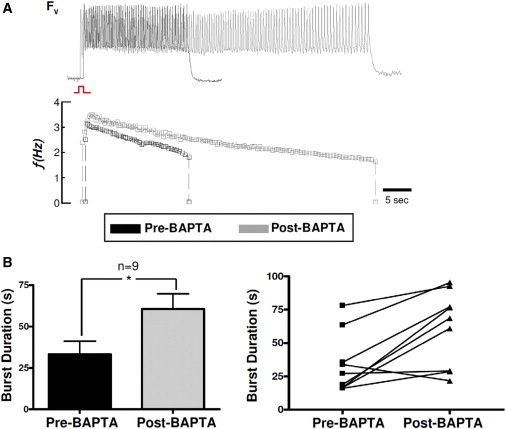

After a single stimulated AP, EAD bursts induced by BayK8644 and isoproterenol were completely suppressed by the LTCC channel blocker nitrendipine (5 μM; Fig. 3 A; n = 7). Neither Na+ channel blockade with 50 μM TTX (Fig. 3 B; n = 5 monolayers) nor suppression of SR Ca2+ cycling with caffeine and thapsigargin (Fig. 3 C) had any significant effect. In contrast, when monolayers were pretreated with BAPTA-AM to buffer intracellular Ca2+, the burst duration increased from 34 s (SD 23) to 61 s (SD 27; n = 9), without significantly affecting the bursting frequency (Fig. 4). In the presence of BAPTA-AM, the bursting frequency declined more slowly during the burst; therefore, the frequency just before burst termination was similar to that of non-BAPTA-treated monolayers.

Figure 3.

EAD bursts are abolished by Ca2+ channel blockade but occur independently of SR Ca2+ cycling and Na+ channel blockade. (A) Bursts were not observed after blockade of the L-type Ca2+ channel with 5 μM nitrendipine. (B and C) Bursts continued to occur after the Na+ channel was blocked with TTX (B), and SR Ca2+ cycling was disabled with 10 mM caffeine and 5 μM thapsigargin (C).

Figure 4.

EAD bursts are prolonged after chelation of intracellular Ca2+. (A) Representative bursts observed by voltage optical mapping before (top panel) and after (bottom panel) incubation with BAPTA-AM for 7 min. (B) Bar graph (left) and the corresponding individual plots of the average burst duration from n = 9 monolayers (right) before and after incubation with BAPTA-AM (error bars represent SDs).

To evaluate whether EAD bursts are a nonspecific consequence of intracellular Ca2+ overload, we exposed monolayers to the Na+-K+-ATPase inhibitor ouabain (100 μM) in the presence of elevated extracellular Ca2+ (3.6 mM, n = 5). In this setting, Ca2+ overload results primarily from reduced Ca2+ efflux via Na+-Ca2+ exchange, although Ca2+ entry via LTCC is also modestly potentiated by the elevated extracellular Ca2+. Under these conditions, we observed runs of activity that increased rather than decreased in frequency, but no EAD bursts (Fig. 5).

Figure 5.

EAD bursts depend on LTCC and not Ca2+ overload per se. Ouabain and high Ca2+ (3.6 mM) produced repetitive focal activity but not bursts. Frequency response plots reveal a gradual increase in bursting frequency that is inconsistent with the dual Hopf-homoclinic bifurcation mechanism. Before the drugs were administered, no spontaneous bursts were observed.

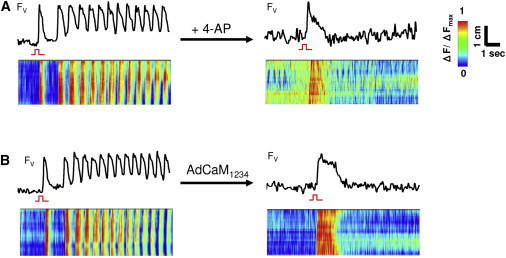

Excessively decreased repolarization reserve suppresses EADs

Another prediction of the dual Hopf-homoclinic bifurcation mechanism is that EADs occur only when the balance between the reactivation kinetics of LTCC and the kinetics of repolarizing K+ currents fall within a critical range (12), irrespective of the repolarization reserve per se. This leads to the prediction that when EADs are present, a further reduction in the repolarization reserve may suppress rather than exacerbate the EADs. To test this prediction, we examined the effects of two interventions designed to further reduce the repolarization reserve in the presence of BayK8644 and isoproterenol. In the first case, we blocked the K+ currents using 4-AP (10 mM). The BayK8644- and isoproterenol-induced EAD bursts were consistently terminated by 4-AP, even though the drug further prolonged the APD (Fig. 6 A; n = 7). This also agrees with a recent study in which H2O2-induced EADs in adult rabbit ventricular myocytes were suppressed by blockade of Ito (31). In the second case, we preinfected monolayers with the adenoviral construct Ad-CaM1234 to overexpress the mutant Ca2+-insensitive calmodulin CaM1234 (26,32). By displacing endogenous CaM, CaM1234 blocks Ca2+-CaM-dependent inactivation of LTCC, thereby further reducing the repolarization reserve and prolonging the APD. The Ad-CaM1234-treated monolayers all exhibited marked AP prolongation, which increased further after exposure to BayK8644 and isoproterenol. However, no EAD bursts occurred either before or after addition of BayK8644 and isoproterenol in seven monolayers (Fig. 6 B). These findings indicate that when EAD bursts were induced by BayK8644 and isoproterenol, a further reduction in the repolarization reserve by two different methods suppressed rather than facilitated EAD bursts, in line with theoretical predictions.

Figure 6.

EAD bursts abolished by reducing repolarization reserve. Blocking the K+ currents with 4-AP (10 mM) (A) or overexpressing the mutant Ca-insensitive calmodulin CaM1234 with AdCaM1234 (B) abolished bursts (top panels). Line scans (bottom panels) show that after addition of 4-AP or AdCaM1234, only focal activity due to the stimulus was observed.

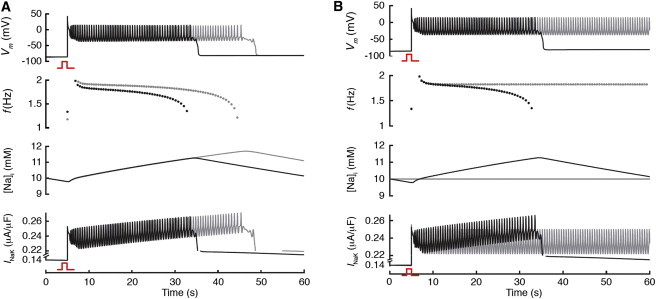

EAD bursting in a detailed AP model

To provide insight into the ionic mechanisms underlying EAD bursting behavior, we carried out computer simulations using the UCLA rabbit ventricular AP model (33), which includes detailed Ca2+ cycling and ionic fluxes. The model reproduced the behavior of EAD bursts as observed in the experiments (Fig. 7 A): 1), the frequency of voltage oscillations gradually declined before termination occurred; and 2), the EAD bursts were unaffected by Na+ channel blockade or disabling of SR Ca2+ cycling. Bursts were also significantly prolonged in duration when intracellular Ca2+ was buffered (Fig. 7 A, gray trace). The model revealed that intracellular Na+ accumulated progressively during the EAD burst, suggesting that this parameter may play a role in burst termination. We confirmed this by clamping intracellular Na+ in the model to 10 mmol/L (Fig. 7 B, gray trace), which caused the bursting to continue indefinitely. The mechanism by which intracellular Na+ accumulation caused burst termination was related to stimulation of the electrogenic Na+-K+ pump, whose outward current eventually increased the repolarization reserve sufficiently to allow full repolarization. This finding correlated with the prolongation of EAD burst duration when intracellular Ca2+ was buffered, which elevated the threshold value of intracellular Na+ accumulation required to induce full repolarization (Fig. 7 A). The dependence of the burst duration and frequency on BAPTA-AM concentration, Ito conductance, and LTCC conductance is shown in Fig. S5.

Figure 7.

Computer simulation of EAD bursts in a detailed AP model. (A) Voltage, bursting frequency (f), Na+ concentration, and INaK versus time for control (black traces) and when intracellular Ca2+ buffer was increased (gray traces). Consistent with experiments, intracellular Ca2+ buffering significantly prolonged burst duration and decreased the rate of frequency decline. During bursts, there is a slow rise in intracellular Na+ that peaks with burst termination, and a gradual increase in the peak Na+-K+ outward current. (B) The same as A, except that the gray traces indicate when intracellular Na+ was clamped to 10 mM, at which point the bursts failed to terminate because the Na+-K+ current failed to accumulate as in the control.

Discussion

In this study, we provide experimental support for the previous theoretically proposed mechanism of EAD formation involving a dual Hopf-homoclinic bifurcation (12). Specifically, we show that in NRVM monolayers exposed to BayK8644 and isoproterenol, bursts of EAD-mediated triggered activity exhibited the predicted dynamical signatures of the dual Hopf-homoclinic bifurcation mechanism. If this mechanism proves to be important in both real and cultured cardiac tissues, it may shed new light on the dynamical mechanism whereby EADs arise and self-terminate, and suggest new avenues for arrhythmia treatment and risk assessment.

Hopf bifurcation mechanism of EAD formation

In nonlinear dynamics, a bifurcation is a change in the qualitative behavior of a system as one or more of its parameters pass a critical value (such as the change from a stable equilibrium to an oscillating behavior). Hopf bifurcation is the classic dynamical mechanism that many systems undergo when they begin to oscillate, ranging from cardiac pacemaking (34) to the fatal oscillations of the Tacoma Narrows Bridge, a wind-induced Hopf bifurcation (35).

A previous theoretical analysis using the LR1 AP model revealed that EADs were initiated by a Hopf bifurcation and terminated by a homoclinic bifurcation (12). The Hopf bifurcation that initiates the EADs not only requires a fine balance between the inward and outward currents to maintain the voltage in the LTCC window voltage range, it also places strict requirements on the timing and kinetics of these currents, which must be balanced in the right range to cause the voltage oscillations during the EAD.

To induce EADs in cardiac monolayers, we used BayK8644 and isoproterenol, which have complex effects on LTCC properties. In addition to increasing LTCC amplitude by promoting mode 2 gating and recruiting quiescent channels, BayK8644 and isoproterenol also affect many other parameters, including the voltage dependence and steepness of steady-state LTCC activation and inactivation curves; the kinetics of activation, inactivation, and recovery from inactivation; and the late (noninactivating) LTCC current component (36–38). Moreover, these agents also influence other ionic currents either directly (e.g., IKs regulation by isoproterenol) or indirectly (by increasing intracellular Ca2+, e.g., through Na+-Ca2+ exchange and activating Ca2+-CaM kinase II). Although it is difficult to pinpoint the exact role of each of these factors, the general effect is to increase the maximal value of the LTCC window current (5). This makes more inward current available when the membrane voltage repolarizes into the LTCC window voltage range, which can reverse repolarization if it is sufficiently large. In support of the critical and essential role of the LTCC in EAD bursts induced by BayK4688 and isoproterenol, bursts were abolished by the Ca2+ channel blocker nitrendipine, but not the Na+ channel blocker TTX, excluding an important role of Na+ currents (including late Na+ current). Also, EAD bursts still occurred when SR Ca2+ cycling was disabled with caffeine/thapsigargin or BAPTA-AM, which excludes spontaneous SR Ca2+ release as the cause of EADs in our experimental system. Thus, our findings provide direct experimental support for the prediction that the interaction of the LTCC with repolarizing currents is sufficient to explain EAD formation and bursting by the Hopf-homoclinic bifurcation mechanism (12), without requiring other factors such as intracellular Ca2+ cycling. However, this does not exclude that possibility that EADs can also be caused by other mechanisms, such as spontaneous SR Ca2+ release, under different conditions or in different tissues.

A key prediction of the Hopf-homoclinic bifurcation mechanism (12) is that, during the early repolarization phase, the repolarization speed has to be sufficient to bring the voltage into the LTCC window region and facilitate the Hopf bifurcation and EAD burst. This was demonstrated in the experiments with 4-AP and CaM1234 shown in Fig. 6. Because Ito is a transient current that occurs mainly during the early repolarization phase of the AP, blocking Ito reduces the repolarization speed in the early repolarization phase, delaying the time it takes for the voltage to enter the window region. Similarly, overexpression of CaM1234 slows the inactivation of LTCC, which also delays the time it takes for voltage to enter the window region. According to our previous study (31), EADs are promoted only in a certain range of Ito conductance, because too much Ito causes a too-fast repolarization, which also prevents EADs. Therefore, in addition to a reduced repolarization reserve in the later repolarization phase of the AP, a proper repolarization reserve in the early repolarization phase is needed for EADs to occur.

Spontaneous termination of EAD bursts

Analysis of the physiologically detailed rabbit ventricular AP model showed that the termination of EAD bursting was due to Na+ accumulation, which gradually increased the outward Na+-K+ pump current until it became sufficiently large to promote full repolarization. The model reproduced the observed pharmacologic responses that buffering intracellular Ca2+ prolonged burst duration by shifting the homoclinic bifurcation point to occur at a higher intracellular Na+ concentration. This is different from the previous theoretical analysis using the simpler LR1 model, in which the termination of the EADs was caused by the slow activation of the slow component of the delayed rectifier K+ current. However, the underlying dynamical mechanism remained the same, i.e., the oscillations are terminated by the homoclinic bifurcation. Thus, in both cases, the bursting frequency gradually decreases before EAD termination occurs. In addition, full activation of the delayed rectifier K+ current only takes several seconds, whereas accumulation of Na+ takes much longer, up to minutes (39), in agreement with the long duration of EAD bursts observed in our experiments. Our study demonstrates that although the specific current responsible for EAD termination may be different under different conditions, the underlying dynamical mechanisms may be still the same, which is important for a unified understanding of the EAD dynamics in different cardiac diseases.

Conclusions

An important limitation of this study is the potential off-target effects of the pharmacological agents used in the experiments. In addition, the NRVM monolayer preparation, despite its advantages for optical mapping, has important electrophysiological differences in comparison with human myocardium. Optical mapping also has limited spatial and temporal resolution, although it permits genuine tissue-level arrhythmias to be characterized and distinguished from nonpropagating EADs. An important caveat is that the experimental model and computer models represented different species. On the other hand, the observation that the experimental model (NRVM) and two different mathematical models (the LR1 guinea pig ventricular model and the UCLA rabbit ventricular model representing different species and levels of physiological detail) yielded consistent results increases our confidence that these findings are generally relevant to EAD-mediated arrhythmias. Whether they will ultimately prove to be clinically relevant is unclear, but the certain similarities are intriguing. For example, the optical mapping of NRVM monolayers revealed that EAD bursts originated from one or more distinct focal sites and produced a pseudo-ECG resembling polymorphic VT, which is the most common form of VT clinically observed in heart failure, LQT syndromes such as Timothy syndrome (LQT8), and increased catecholamines. Finally, the dynamical understanding of EADs may suggest a new paradigm for antiarrhythmic drug development to prevent cardiac arrhythmias by targeting the kinetics rather than the amplitudes of ion channels, such as LTCC, as determinants of EAD formation.

Acknowledgments

We thank Guillaume Calmettes for technical assistance.

This study was supported by a Scientist Development Grant from the American Heart Association (M.R.A.); the Donald W. Reynolds Foundation; NIH grants R01 HL66239 (L.T.), P01 HL078931 (J.W, A.G, and Z.Q), R01 HL103622 (J.W and Z.Q), T32GM008042 (M.G.C), and T32GM065823 (M.G.C); a fellowship award for advanced researchers from the Swiss Foundation for Grants in Biology and Medicine (E.D.L); and the Laubisch and Kawata endowments (J.W.).

Contributor Information

Zhilin Qu, Email: zqu@mednet.ucla.edu.

M. Roselle Abraham, Email: mabraha3@jhmi.edu.

Supporting Material

References

- 1.Kossmann C.E. The long Q-T interval and syndromes. Adv. Intern. Med. 1987;32:87–110. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Vermeulen J.T. Mechanisms of arrhythmias in heart failure. J. Cardiovasc. Electrophysiol. 1998;9:208–221. doi: 10.1111/j.1540-8167.1998.tb00902.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Marban E., Robinson S.W., Wier W.G. Mechanisms of arrhythmogenic delayed and early afterdepolarizations in ferret ventricular muscle. J. Clin. Invest. 1986;78:1185–1192. doi: 10.1172/JCI112701. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Luo C.H., Rudy Y. A dynamic model of the cardiac ventricular action potential. II. Afterdepolarizations, triggered activity, and potentiation. Circ. Res. 1994;74:1097–1113. doi: 10.1161/01.res.74.6.1097. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hirano Y., Moscucci A., January C.T. Direct measurement of L-type Ca2+ window current in heart cells. Circ. Res. 1992;70:445–455. doi: 10.1161/01.res.70.3.445. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Shorofsky S.R., January C.T. L- and T-type Ca2+ channels in canine cardiac Purkinje cells. Single-channel demonstration of L-type Ca2+ window current. Circ. Res. 1992;70:456–464. doi: 10.1161/01.res.70.3.456. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.January C.T., Riddle J.M. Early afterdepolarizations: mechanism of induction and block. A role for L-type Ca2+ current. Circ. Res. 1989;64:977–990. doi: 10.1161/01.res.64.5.977. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Roden D.M. Long QT syndrome: reduced repolarization reserve and the genetic link. J. Intern. Med. 2006;259:59–69. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2796.2005.01589.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kannankeril P.J., Roden D.M. Drug-induced long QT and torsade de pointes: recent advances. Curr. Opin. Cardiol. 2007;22:39–43. doi: 10.1097/HCO.0b013e32801129eb. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Michael G., Xiao L., Nattel S. Remodelling of cardiac repolarization: how homeostatic responses can lead to arrhythmogenesis. Cardiovasc. Res. 2009;81:491–499. doi: 10.1093/cvr/cvn266. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Roden D.M. Taking the “idio” out of “idiosyncratic”: predicting torsades de pointes. Pacing Clin. Electrophysiol. 1998;21:1029–1034. doi: 10.1111/j.1540-8159.1998.tb00148.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Tran D.X., Sato D., Qu Z. Bifurcation and chaos in a model of cardiac early afterdepolarizations. Phys. Rev. Lett. 2009;102:258103. doi: 10.1103/PhysRevLett.102.258103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Strogatz S.H. Addison-Wesley; Reading, MA: 1994. Nonlinear Dynamics and Chaos: With Applications to Physics, Biology, Chemistry, and Engineering. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Guevara M.R., Jongsma H.J. Three ways of abolishing automaticity in sinoatrial node: ionic modeling and nonlinear dynamics. Am. J. Physiol. 1992;262:H1268–H1286. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.1992.262.4.H1268. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Qu Z., MacLellan W.R., Weiss J.N. Dynamics of the cell cycle: checkpoints, sizers, and timers. Biophys. J. 2003;85:3600–3611. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(03)74778-X. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Goldbeter A., Lefever R. Dissipative structures for an allosteric model. Application to glycolytic oscillations. Biophys. J. 1972;12:1302–1315. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(72)86164-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Goldbeter A. A model for circadian oscillations in the Drosophila period protein (PER) Proc. Biol. Sci. 1995;261:319–324. doi: 10.1098/rspb.1995.0153. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Abraham M.R., Henrikson C.A., Marbán E. Antiarrhythmic engineering of skeletal myoblasts for cardiac transplantation. Circ. Res. 2005;97:159–167. doi: 10.1161/01.RES.0000174794.22491.a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Eschenhagen T., Didié M., Zimmermann W.H. Cardiac tissue engineering. Transpl. Immunol. 2002;9:315–321. doi: 10.1016/s0966-3274(02)00011-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Husse B., Wussling M. Developmental changes of calcium transients and contractility during the cultivation of rat neonatal cardiomyocytes. Mol. Cell. Biochem. 1996;163-164:13–21. doi: 10.1007/BF00408636. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Zimmermann W.H., Schneiderbanger K., Eschenhagen T. Tissue engineering of a differentiated cardiac muscle construct. Circ. Res. 2002;90:223–230. doi: 10.1161/hh0202.103644. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Goldhaber J.I., Xie L.H., Weiss J.N. Action potential duration restitution and alternans in rabbit ventricular myocytes: the key role of intracellular calcium cycling. Circ. Res. 2005;96:459–466. doi: 10.1161/01.RES.0000156891.66893.83. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Dipla K., Mattiello J.A., Houser S.R. The sarcoplasmic reticulum and the Na+/Ca2+ exchanger both contribute to the Ca2+ transient of failing human ventricular myocytes. Circ. Res. 1999;84:435–444. doi: 10.1161/01.res.84.4.435. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Negretti N., O'Neill S.C., Eisner D.A. The effects of inhibitors of sarcoplasmic reticulum function on the systolic Ca2+ transient in rat ventricular myocytes. J. Physiol. 1993;468:35–52. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1993.sp019758. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Lukyanenko V., Viatchenko-Karpinski S., Györke S. Dynamic regulation of sarcoplasmic reticulum Ca2+ content and release by luminal Ca2+-sensitive leak in rat ventricular myocytes. Biophys. J. 2001;81:785–798. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(01)75741-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Mahajan A., Sato D., Weiss J.N. Modifying L-type calcium current kinetics: consequences for cardiac excitation and arrhythmia dynamics. Biophys. J. 2008;94:411–423. doi: 10.1529/biophysj.106.98590. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Malmivuo J., Plonsey R. Oxford University Press; New York: 1995. Bioelectromagnetism. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Mahajan A., Shiferaw Y., Weiss J.N. A rabbit ventricular action potential model replicating cardiac dynamics at rapid heart rates. Biophys. J. 2008;94:392–410. doi: 10.1529/biophysj.106.98160. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Chang M.G., Sato D., Qu Z. Bi-stable wave propagation and early afterdepolarization-mediated cardiac arrhythmias. Heart Rhythm. 2012;9:115–122. doi: 10.1016/j.hrthm.2011.08.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Cohen S.D., Hindmarsh A.C. CVODE, a stiff/nonstiff ODE solver in C. Comput. Phys. 1996;10:138–143. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Xie Y., Zhao Z., Xie L.-H. The transient outward current Ito promotes early afterdepolarizations. Biophys. J. 2010;98:531a. (abstract) [Google Scholar]

- 32.Alseikhan B.A., DeMaria C.D., Yue D.T. Engineered calmodulins reveal the unexpected eminence of Ca2+ channel inactivation in controlling heart excitation. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2002;99:17185–17190. doi: 10.1073/pnas.262372999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Sato D., Xie L.H., Qu Z. Synchronization of chaotic early afterdepolarizations in the genesis of cardiac arrhythmias. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2009;106:2983–2988. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0809148106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Landau M., Lorente P., Jalife J. Bistabilities and annihilation phenomena in electrophysiological cardiac models. Circ. Res. 1990;66:1658–1672. doi: 10.1161/01.res.66.6.1658. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Holmes P., Marsden J.E. Bifurcations of dynamical systems and nonlinear oscillations in engineering systems. In: Chadam J.M., editor. Nonlinear Partial Differential Equations and Applications. Vol. 648. Springer-Verlag; New York: 1978. pp. 163–206. (Lecture Notes in Mathematics). [Google Scholar]

- 36.January C.T., Riddle J.M., Salata J.J. A model for early afterdepolarizations: induction with the Ca2+ channel agonist Bay K 8644. Circ. Res. 1988;62:563–571. doi: 10.1161/01.res.62.3.563. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Kass R.S. Voltage-dependent modulation of cardiac calcium channel current by optical isomers of Bay K 8644: implications for channel gating. Circ. Res. 1987;61:I1–I5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Sanguinetti M.C., Krafte D.S., Kass R.S. Voltage-dependent modulation of Ca channel current in heart cells by Bay K8644. J. Gen. Physiol. 1986;88:369–392. doi: 10.1085/jgp.88.3.369. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Faber G.M., Rudy Y. Action potential and contractility changes in [Na+](i) overloaded cardiac myocytes: a simulation study. Biophys. J. 2000;78:2392–2404. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(00)76783-X. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.