Abstract

An hypothesis is developed to explain how the unique, right circular conical geometry of cone outer segments (COSs) in Xenopus laevis and other lower vertebrates is maintained during the cycle of axial shortening by apical phagocytosis and axial elongation via the addition of new basal lamellae. Extension of a new basal evagination (BE) applies radial (lateral) traction to membrane and cytoplasmic domains, achieving two coupled effects. 1), The bilayer domain is locally stretched/dilated, creating an entropic driving force that draws membrane components into the BE from the COS's distributed bilayer phase, i.e., plasmalemma and older lamellae (membrane recycling). Membrane proteins, e.g., opsins, are carried passively in this advective, bilayer-driven process. 2), With BE stretching, hydrostatic pressure within the BE cytoplasm is reduced slightly with respect to that of the axonemal cytoplasmic reservoir, allowing cytoplasmic flow into the BE. Attendant lowering of the reservoir's hydrostatic pressure facilitates the subsequent transfer of cytoplasm from lamellar domains to the reservoir (cytoplasmic recycling). The geometry of the BE reflects the membrane/cytoplasm ratio needed for its construction, and essentially specifies the ratio of components recycled from older lamellae. Length and taper angle of the COS reflect the ratio of recycled/new components constructing a new BE. The model also integrates the trajectories and dynamics of lamella open margin lattice components. Although not fully evaluated, the initial model has been assessed against the relevant literature, and three experimental predictions are derived.

Introduction

The photoreceptive outer segments of cone cells (COSs) in lower vertebrates have a distinctive, truncated conical shape (frustum) within which one region of plasmalemma (PL) has been folded into a compact axial array of paired membrane units called lamellae (1,2) (Fig. 1). Although investigators have been familiar with vertebrate cone and rod photoreceptor geometries since the 19th century (7), it gives one pause to realize that a distinctive and enduring conical geometry is very rare at the level of membranous organelles, and perhaps unique to the COS. It is not known how mature COS geometry is established or maintained, although the two processes might be quite different (2,8–12). In the ciliary photoreceptor lineage, cone cells likely evolved before rod cells (13,14). In addition, the outer segments of cones and rods appear indistinguishable during early development, with both displaying an irregular conical shape (2,9,15,16). Thus, devising a model in lower vertebrates to explain the maintenance of conical COS geometry after it has been initially established could provide insights and testable hypotheses regarding operant mechanisms, and might inform our thinking about initial construction of the mature COS geometry and its modifications during the evolution of cone and rod cells (17).

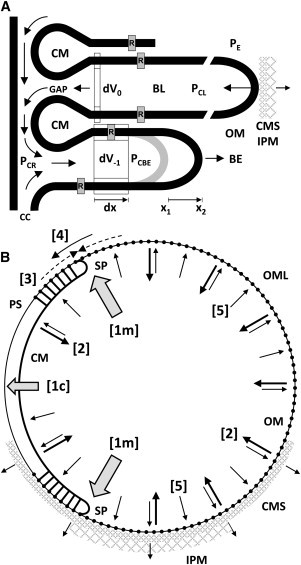

Figure 1.

Schematic views of a COS. (A) Overall COS geometry is rendered as a truncated right circular cone (frustum). The continuous membrane system has two main regions: a central stack of paired, parallel membrane units called lamellae, and a plasmalemma (PL) that partially encloses the lamellae along one side. The near side is cut into a longitudinal section (LS) to show internal relationships. The two membranes of each lamella are continuous along the open margin (OM) segment of the lamella perimeter; adjacent lamellae are continuous via closed margin (CM) or rim segments (Figs.1C). All four membrane domains are continuous at saddle points (SPs) (Figs. S2 and S3). The COS is continuous with the cone inner segment (CIS) via the connecting cilium (CC). Near the CC base, the CIS PL forms a series of ridges and grooves: the periciliary ridge complex (PRC) (3). From the CIS perimeter, calycal processes (CPs) project apically along the COS surface. A short stretch of OM lattice (OML) is indicated, extending past SPs to the PL surface. Axial elements of the OML connect adjacent lamellae; radial elements connect OMs to CPs (4,5). Developing lamellae (BE = basal evaginations) expand laterally in the space between COS and CIS (enlarged for visibility). Within the COS, paired membrane folds of smaller size (partial discs = PD) are also present. Drawing by Dr. Bradley R. Smith (adapted from (6) with permission from Elsevier). (B) Cross section through the COS. One lamella surface (Lam) is shown with OM and CM segments. These segments are continuous with the PL at SPs (Fig. S2 and Fig. S3). The cytoplasmic reservoir consists of axonemal cytoplasm (CA; ciliary matrix with microtubules) and flanking cytoplasmic sheaths (CS) of approximate constant width. The PL is similarly parsed: axonemal plasmalemma (PA) and plasmalemmal sheaths (PS). Electron micrographs ((4); their Fig. 3) show linear densities (L) spanning the CS, linking PS and CM surfaces near SPs. Line LS approximates the section planes in A and C. (C) Longitudinal section through the COS near LS, showing the changing lamella perimeter organization near an SP. CS width is ∼6.7 nm ((4); their Fig. 3A and B). Within the left CS, lines (L) depict PS-to-CM densities (4). On the right, similar lines suggest how CMs might be linked to OML elements transferred to the PS near SPs. Occasionally, cytoplasmic densities (CD) span the lamellar cytoplasm (CL) near CM and OM segments. Lamella cytoplasm is continuous with the cytoplasmic reservoir via the CM gap.

Like rod outer segment (ROS) discs, COS lamellae are subject to turnover (18), and the COS itself undergoes a cycle of shortening and lengthening during which its underlying conical parameters (basal diameter and taper angle) are retained. In animals maintained on a daily light/dark cycle, groups of apical lamellae near the COS tip are phagocytized by the overlying retinal pigment epithelium during the dark phase (19–22), and as new lamellae are added subsequently, the average length and shape of the COS are reestablished. Bok (20) articulated the mechanistic challenge posed by this pattern of renewal involving both the addition of new lamellae and reshaping of the COS. What are the “mechanisms whereby COSs remodel themselves after each shedding event? Because the most apical cone outer segment discs have a constant but smaller diameter than the basal ones in most species, how is this configuration reestablished once the terminal discs are shed? Disc fluidity could be an important factor in this remodeling process, but cytoskeletal elements may play a role as well.” His question may be called the “conical shape problem”, and forms the principal focus of this work.

COS lengthening via the addition of lamellae appears intrinsically linked with maintenance of COS shape: COSs usually appear as conical frusta of different lengths. No other geometry is typically observed to suggest, e.g., that lengthening is followed by resculpting. How lamellae are added to the COS has been an unresolved question ever since early studies showed a striking difference in spatial patterns of autoradiographic labeling between COSs and ROSs. When animals are injected with radiolabeled amino acids, COSs develop a diffuse pattern of silver grains over their full length, whereas ROSs show a distinctive basal band of labeling, in addition to some diffuse labeling of more distal regions (23,24). Progressive apical displacement of this labeled band over time established that new discs are formed at the base of the ROS. Whereas an extensive literature has developed around the mechanisms of disc renewal and their several membrane components in vertebrate ROSs (25–31,3,5,19,20), membrane dynamics in the evolutionally older cone system are less well understood (32).

In lower vertebrates, the basal evaginations (BEs) of COSs and ROSs present similar membrane shapes and topology, with continuity between the enlarging BE and the PL (2,8,25,26,31). The structural similarities of BE formation in both frog ROSs and COSs strongly suggest that new lamellae are added to the COS along its basal surface. Eckmiller (15,21,22) has proposed a second mechanism (distal invagination) operating within more distal regions of the COS. The axial distribution of these distal invaginations (also called partial discs) appears to change during the daily light cycle (22), reflecting dynamic structural processes within the COS (see the Supporting Material, Part 11).

The present model builds initially upon a BE mode of lamella formation (27), focuses primarily on Xenopus COSs, and depends strongly on the approximately linear increase in COS length observed during the light phase of the daily 12 h light/12 h dark cycle (21,22).

Model approach to the conical shape problem

If new lamellae develop at the base of the COS and removal occurs only by apical phagocytosis, a fundamental mass conservation question is then posed by the evolving conical geometry of the lamellar array (Fig. 2). When a new, maximum-diameter basal lamella (BL) is added to the COS, the number of lamellae increases from n = n0 to n = n0 + 1. However, the only net change in overall structure is the presence of an apical lamella of slightly smaller diameter. This apical lamella is the measure of mass added to the COS to lengthen it by distance d.

Figure 2.

(A) Axial section through a COS with 10 lamellae of axial spacing d = 34.6 nm (not to scale), basal radius r0 = 2.1 μm, and taper angle α = 9.5°. (B) The same COS after addition of one new BL in the model. Each preformed lamella is advanced apically by distance d. Axial positions i = [0,10] for both sets of lamellae are indicated at the right. The oblique arrow indicates lamella 4 advancing to position 5. The most basal, full-sized lamella (basal lamella; BL) is always indexed to position 0. The z coordinate of each lamella i is zi = i × d.

The total membrane area of a new BL (A0) is modeled as the sum of membrane area lost from each of the preexisting lamellae [i = 0,n0] during apical displacement by d plus the membrane area of the apical lamella (An0+1). This relationship is quantified as follows. When basal lamella i = 0 advances apically by d to position i = 1, it decreases in area: ΔA0 = A0–A1. If we sum the area differences for all [0,n0] lamellae advanced by d during the addition of a new basal lamella, we obtain the bracketed summation in Eq. 1. This {sum} represents the total membrane area removed from the initial lamellar array as it advances from positions [0,n0] to positions [1,n0 + 1]. This {sum} is also equal to the membrane area lost from lamella i = 0 if it alone were to advance from i = 0 to i = n0 + 1: {sum} = A0 – An0+1; the array format merely presents this summation as a series of incremental steps. This relationship can also be seen by expanding the bracketed summation below and cancelling terms. Thus,

| (1) |

Equation 1 is the algebraic formulation of Fig. 2. The average radius of each lamella ri = r0 – i × d × tan α, and the membrane area of each lamella Ai = 2π × ri2. This view suggests that during the formation of a new BL, there occurs a systematic redistribution of some older membrane components from preexisting lamellae via saddle points (SPs) and the COS PL to the new BL, in addition to the arrival of new components from the cone inner segment (CIS) via the connecting cilium (CC). This proposed COS redistribution mechanism is termed membrane recycling (or reflux). A coupled hydraulic process involves the redistribution of cytoplasmic components (cytoplasmic recycling).

Any integrated model of continuous lamella restructuring during axial COS growth must address several other issues: 1), maintenance of the circular (or slightly elliptical (2)) shape of individual lamellae, and 2), disassembly and reorganization of the open margin lattice (OML) that interconnects the open margin (OM) segments of lamellae, components of which extend for some distance into the plasmalemmal sheath near SPs. COS shape might also be influenced by other components in contact with its surfaces (Figs. 1 A and 3), e.g., calycal processes (CPs), the apical surface of the CIS, the cone matrix sheath (CMS), and the interphotoreceptor matrix (IPM) (33).

Figure 3.

Proposed distribution of lamella forces. (A) Differential forces and flows associated with the BL and the BE are discussed in the text. During recycling, the ratio of membrane/cytoplasmic volume lost from each lamella basically reflects the ratio demanded by the growing BE. Hydrostatic pressures: PE extracellular; PCL lamellar cytoplasm; PCR cytoplasmic reservoir; PCBE BE cytoplasm. Intracellular arrows: cytoplasmic recycling pattern. Scale: opsins (R): 75 Å long in the z direction (40). (B) Cross-sectional representation of structural changes and component flows in a lamella. The event sequence [1] → [4] is discussed in text. The outwardly directed arrows [5] represent a radial component of the small pressure increase postulated within lamella cytoplasm. Dynamic linkages between the COS surface and surrounding CMS and interphotoreceptor matrix might also oppose reduction in lamella radius and contribute to maintaining circular lamella shape. CM = closed margin; OM = open margin; OML = OM lattice; SP = saddle point. Spanning cytoplasmic sheaths near SPs, short links join the CM to PSs.

This work evaluates an initial hypothetical model of structural and dynamic aspects of advective recycling, primarily within Xenopus COSs, and its basic consequences for contiguous structures. Three experimental predictions are specified. Several aspects of a recycling mechanism have been discussed briefly in previous work (34–37,5). A related work has addressed integration of advective recycling with opsin diffusion (6).

Materials and Methods

This section is included in the Supporting Material, Part 1.

The model of COS dynamics consists of 1), a formulation of COS geometry, both static and dynamic, which is presented in the Supporting Material, Parts 2 and 3; and 2), a mechanistic model that describes forces and flows associated with recycling, as well as those maintaining circular cross-sectional lamellar shape. Core mechanisms are outlined below, with further details in the Supporting Material.

Results and Discussion

Forces and flows during recycling of COS components

The general structure of the COS can be viewed as an extensively folded membranous vesicle with a remarkably high surface area/volume ratio that is reflected primarily in the geometry of lamellae. Dynamic structural changes are conceived within this global constraint established by the cone cell. We initially assume that all lamellae have the same thickness and axial spacing.

The forces involved in COS recycling are suggested by the effects of locally applied pressure differentials on the shape of bilayer vesicles. For example, when a small suction pipette is applied to a large, unilamellar, approximately spherical bilayer vesicle, part of the vesicle is drawn into the pipette by a distance determined by the pressure differential (38,39). Intravesicular fluid is advanced in tandem along the pipette. When suction is released, the leading edge of the vesicle retracts to its resting position, as does the intravesicular fluid. This cycle can be repeated multiple times. The suction applied to the vesicle surface stretches the in-plane packing of lipid components, increasing the net exposure of hydrocarbon domains to the aqueous medium. This entropic effect is stored as potential energy in the bilayer while the pressure differential is applied. When suction is released, the surface area and thickness of the bilayer return to their original values, propelling the intravesicular fluid back to its reservoir. Such a coupling of hydraulic and entropic mechanisms is proposed as the principal mechanism whereby the elaboration of a BL from a BE leads to the recycling of membrane and cytoplasmic components from older COS lamellae during axial displacement. In the current model, such coupled entropic and hydraulic forces are derived from the mechanisms that elaborate a new BE, which are envisioned as actin-myosin-based processes that apply radial traction to the advancing margin of the BE (Figs. S2 and S12). For further development, see the Supporting Material, Part 4.

The proposed BE extension mechanism simultaneously applies radial (lateral) traction to both membrane and cytoplasmic domains (Fig. 3 A), achieving two coupled effects. 1), The bilayer domain is locally stretched/dilated, creating an entropic driving force that induces the lateral flow of membrane components into the BE from the distributed bilayer phase of the COS. BE bilayer stretching is initially propagated to the plasmalemma, and from there to lamellae, primarily via SPs. Membrane proteins, e.g., opsins, are carried passively in this advective bilayer-driven process. 2), For cytoplasm to flow into the BE, the hydrostatic pressure within the BE cytoplasm (PCBE) must be reduced slightly with respect to that of the axonemal cytoplasmic reservoir (PCR). The attendant lowering of hydrostatic pressure within the cytoplasmic reservoir facilitates the subsequent transfer of cytoplasm from lamellar cytoplasmic domains (PCR < PCL) to the reservoir. Bilayer stretching propagated to older lamellae is seen to assist in the transfer of lamella cytoplasm to the cytoplasmic reservoir. These small pressure differentials guide the recycling of cytoplasm within the COS.

When a new BL is constructed, it is approximately circular in shape and its diameter approximates that of the adjacent CIS. Because its diameter is so much greater than its thickness, the BL can be viewed initially as a two-dimensional object, whose perimeter is the minimum length needed to enclose its area. Two structural constrains apply. As the BL is subsequently displaced apically, it retains its circular shape and nominal thickness while decreasing in diameter, i.e., it retains its area (A): perimeter (P) ratio: A/P = πr2/2πr = r/2, where r = lamella radius. Second, for the three-dimensional lamella to retain its initial thickness, it must lose membrane area/volume and cytoplasmic volume in a fixed proportion. Therefore, for a change in lamella area ΔA, the membrane (M) volume removed VM = 2 × ΔA × τM, and the volume of cytoplasm (C) removed VC = ΔA × τC, where τ is domain thickness. The ratio VM/VC = 2 × τM/τC. How are both constraints achieved? The present model proposes two mechanisms (Fig. 3): one that removes (recycles) membrane and cytoplasm from lamellae in the proportion dictated by the emergent BE, and a second coupled process that controls the A/P ratio by regulating the interactions between OM and CM components near SPs.

In Fig. 3 A, the growing BE at i = −1 and the adjacent BL at i = 0 are depicted within an extracellular fluid space at pressure PE. During time t, the leading edge of the BE is extended from x1 to x2, and its associated lamella domain is increased correspondingly (dx). The new rectangular volume element dV−1 consists of both membrane and cytoplasmic layers that are parallel. Let the cross-sectional area of this volume element = ΔA = dx × dx. The bilayer stretching induced by extension of the BE margin acts to induce advective membrane flow from older lamellae [i = 0,n0]. The change in total membrane volume dVM = 2 × ΔA × τM and is provided both by recycling and by new components arriving from the CC. Similarly, the coupled change in cytoplasmic volume is = dV−1 = ΔA × τC. Thus, as the BE margin advances radially, its parallel lamellar geometry specifies the ratio of membrane/cytoplasmic volume needed for its construction: VM/VC = 2 × τM/τC. This volume ratio basically establishes the ratio of recycled components extracted from older lamellae (e.g., dV0) via forces propagated through membrane and cytoplasmic domains. The same volume ratio (or nearly so) would apply to new lamella components from the CIS. Otherwise, the lamelliform geometry of the COS array and the geometry of the axonemal region would become progressively distorted.

Restructuring the lamella perimeter requires a different framework. As noted previously, each lamella is a two-dimensional structure (diameter ≫ thickness), whose circular shape defines the minimum perimeter needed to enclose its area. This minimum perimeter/area ratio is retained during apical displacement. The three-dimensional correlate is that each lamella retains its surface/volume ratio. These geometrical considerations indicate that as a lamella shrinks in size, changes in membrane area and cytoplasmic volume are tightly coupled to reductions in lamellar perimeter. Otherwise, the lamella would develop additional curvatures in its axial (z) direction and/or its perimeter would develop a scalloped, lobulated shape analogous to that of ROS discs (2,29).

A sequence of five mechanistic steps is proposed below using Fig. 3 B, with additional discussion in the Supporting Material, Part 7. (step 1) The extraction of lamella membrane components via SPs [1m] and cytoplasmic components [1c] via the closed margin (CM) gap establishes an inward radial traction on CM and OM segments that (step 2) summates along the perimeter and attempts to reduce lamella radius. This inward traction also initiates tangential compression (step 3) within the ring-like perimeter support provided by interlocking OM and CM segments that opposes radius reduction. Tangential compression is transiently relieved by the transfer of OML components to the plasmalemmal sheaths (step 4). Tangential compression vectors in each segment converge on their common linkages near SPs. Due to the radial and axial offsets of CM and OM elements (Fig. 1, B and C), linkages are subjected to a tangential shearing force that triggers the following cycle during axial advancement: a), bond breaking: transient severing of links between OM, CM, and plasmalemmal sheath components, b), segmental slippage, with tangential displacement of OM components to the plasmalemmal sheath, and c), reestablishment of structural links. This progressive, linear disassembly of OML edges enables coordinated reductions in perimeter length, lamella radius, and area. The outwardly directed arrows (step 5) indicate the radial component of a small hydraulic pressure increase postulated to occur within a lamella as a result of a slight mismatch between the rates at which membrane and cytoplasmic components can be extracted (Supporting Material, Part 8).

Extraction/extrusion of cytoplasm through the CM gap is coupled to these changes in membrane relationships and cytoplasmic pressure differentials. Operating in concert, these mechanisms contribute to maintaining circular cross-sectional shape, whereas lamellae decrease linearly in diameter with apical displacement, thereby maintaining conical taper angle.

Two inferences are drawn from this perimeter-reducing mechanism: 1), the underlying molecular interactions are noncovalent in nature; and 2), the sequence of structural changes among linkages describes an escapement-like mechanism that limits the rate at which the OML can be disassembled and lamella radius reduced. This mechanism appears to be a zero-order rate process that operates uniformly along the COS.

The ability of lamellae to respond individually to bilayer stretching and hydraulic pressure differentials is limited by their connectivity via OML and CM components, which help constrain the lamellar array to an integrated, coordinated response. These same forces should also affect the transport of lipids and possibly other components into the COS from the CIS via the CC. Finally, stretching of the BE has suggested potential traction mechanisms located within the apical CIS (Part 12).

Prediction 1: a gradient of advective membrane flow occurs in the COS plasmalemma

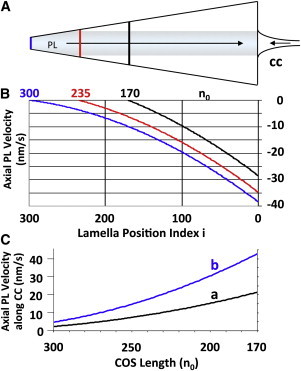

Fig. 4 presents the average velocity gradient of the PL calculated over Td at three different time points: near the beginning of light onset [n0 = 170], 6 h after light onset [n0 = 235], and just before light offset [n0 = 300]. In each case, the velocity gradient is nonlinear, ∼0 at the COS tip and maximum at its base. See Figs. S2 B, S3, and Parts 2 and 3. The velocity gradient increases during the light period as additional lamellae are added to the COS and transfer additional membrane area to the PL during apical displacement. Fig. 4 C estimates the corresponding average velocities of membrane components arriving from the CIS via the CC. Conical angle and COS length are seen as direct indicators of the degree of recycling likely to be occurring within any given COS.

Figure 4.

(A) Predicted basal flow of lamella-derived membrane components along the COS PL. New components arrive via the CC. (B) PL velocity gradient versus number of lamellae (n0 = 170, 235, and 300). (C) PL velocity of membrane components near the base of the CC versus n0. Curve a is computed using the entire circumference of the CC near its base (diameter ≈ 35 nm (3)). Because Y connectors within the CC involve about one-half of its PL, curve b reflects this reduced membrane flow area.

This arrangement of countercurrent membrane flows is striking: after 12 h in the light, plasmalemmal membrane velocity at the COS midpoint is ∼−120 Å/s and ∼−350 Å/s near its base (Fig. 4 B), whereas the apical velocity of the lamella array remains at ∼+1 Å/s (Part 1). Thus, appropriate labeling of plasmalemmal components should permit the experimental detection of membrane flow patterns along the plasmalemma, and thereby provide a means of testing the recycling feature of the present model. (Partial COS discs are discussed in Part 11.)

Prediction 2: composition of new basal lamellae changes in a systematic sequence

The fractions of new and older (recycled) components that contribute to formation of a new BL depend upon the length of the COS (Fig. 5). At the beginning of the light cycle (n0 = 170), new components contribute ∼28% of the new BL area. As the COS lengthens the percentage of recycled components increases. When n0 = 300, new components from the inner segment contribute only ∼3% to a new lamella. Thus, with axial growth, new components incorporated into the BL are increasingly diluted, a prediction amenable to autoradiographic investigation. This analysis indicates that the principal membrane transport problem to be solved within the COS is the manipulation of older membrane components. Quantitatively, influx of new membrane components via the CC, although essential, is a lesser consideration.

Figure 5.

Predicted basal lamella composition due to advective flows only (no diffusion corrections (6)): flow rates and fractional contributions from NEW (via CC) and OLDER (recycled) components versus COS length. The composition ordinate applies to both membrane area and cytoplasmic volume.

How might this smooth, continuous adjustment of BL composition be coordinated with CC transport processes? A mechanical sensor of bilayer stretching (41) associated with the CC would be well positioned to regulate the active transport of opsins and other components into the COS, and the tension developed in the growing BE. Linkages between OM segments and CPs might also serve to monitor membrane stretching, as might CM-OML links near SPs.

Prediction 3: OML components have defined surface trajectories

The paths of OML components along the COS surface are illustrated in Fig. 6. With apical advancement, each lamella will have continuously changing positional and linkage relationships with CPs and CMS/IPM components. Part 5 (Figs. S4–S6) contains particle velocity data, with application to the formation and apical advancement of the OML and, by inference, COS lamellae (Part 13).

Figure 6.

Predicted trajectories of open margin particles (dots and arrowheads on trajectories j = ±100 indicate directions of movement). (A) Z-axis projection. This COS has n0 = 300 lamellae. Basal (i = 0) and apical perimeters (i = 300; tip) are labeled. The SP line separates PL and OM surfaces. Trajectories (blue) are plotted for a subset of OM particles: j = ± 4,25,50,75,…,250,265. CPs = 0–9 are shown on one side at 20° intervals. Each CP projects from COS base to tip. Most OM particles will interact with several CPs. (B) Lateral view with +j OM particle trajectories shown in orthographic projection. PL contour lines indicate axial intervals of 30 lamellae. Five CPs are included: +[2–6]. Z-axis scale: z′ = 0.785 × z.

Variations in taper angle

In this model, COS length and taper angle reflect the variable ratio of BE components derived from recycling versus the CIS (e.g., Eq. 1; Figs. 2, 3 A, 4, and 5, Fig. S2). Consider the geometry in Figs. 3 A and Fig. S2 B. As local hydraulic and entropic forces propagate from the BE toward the CC, the flows induced will depend on the effective resistance presented by the COS and by the CIS/CC complex. These flows are considered passive with respect to applied BE forces. However, active transport along the CC could augment any passively induced flows into the basal COS. To the extent that active transport satisfies the compositional demands of the BE mechanism, the forces available for recycling will be reduced. Less recycling implies a smaller taper angle (Part 10). The nearly cylindrical shapes of mammalian COSs (42,5,32) might reflect a predominance of active transport mechanisms along the CC, with little or no recycling.

Conclusion

This model for maintaining the right circular conical geometry of COSs involves the orchestration of an ensemble of interacting components and processes. The mechanism of BE formation plays a central role in recycling in that its own structure basically establishes the ratio of membrane/-cytoplasmic volume that governs the extraction of these components from older lamellae. The entropic and hydraulic forces that originate at the leading edge of the BE are propagated to older COS lamellae via bilayer and cytoplasmic phases, respectively. These forces will also affect the transfer of components from the CIS to the COS, and would work in concert with active vectorial transport along the CC.

Acknowledgments

I especially thank Richard D. Fetter for valuable comments and permission to quote from his work; Ewa Worniałło for consummate technical skills and advice; and Bradley R. Smith for his rendering of COS structure (Fig. 1 A). For valuable discussions and suggestions, many thanks to Thomas J. McIntosh, Laurens E. Howle, Paul W. Weber, Barry E. Knox, Peter D. Calvert, Medhi Najafi, Mohammad Haeri, Joseph C. Besharse, and Beth Burnside.

This work was supported in part by the National Eye Institute (EY04922) and by internal transition funding from the Duke University School of Medicine (391-1377).

Supporting Material

References

- 1.Moody M.F., Robertson J.D. The fine structure of some retinal photoreceptors. J. Biophys. Biochem. Cytol. 1960;7:87–92. doi: 10.1083/jcb.7.1.87. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Nilsson S.E.G. The ultrastructure of the receptor outer segments in the retina of the leopard frog (Rana pipiens) J. Ultrastruct. Res. 1965;12:207–231. doi: 10.1016/s0022-5320(65)80016-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Peters K.-R., Palade G.E., Papermaster D.S. Fine structure of a periciliary ridge complex of frog retinal rod cells revealed by ultrahigh resolution scanning electron microscopy. J. Cell Biol. 1983;96:265–276. doi: 10.1083/jcb.96.1.265. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Fetter R.D., Corless J.M. Morphological components associated with frog cone outer segment disc margins. Invest. Ophthalmol. Vis. Sci. 1987;28:646–657. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Corless J.M., Worniałło E., Fetter R.D. Modulation of disk margin structure during renewal of cone outer segments in the vertebrate retina. J. Comp. Neurol. 1989;287:531–544. doi: 10.1002/cne.902870410. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Weber P.W., Howle L.E., Murray M.M., Corless J.M. A simplified mass-transfer model for visual pigments in amphibian retinal-cone outer segments. Biophys. J. 2011;100:525–534. doi: 10.1016/j.bpj.2010.11.085. S1–S11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Schultze M. Concerning rods and cones of the retina. Arch. Mikroskop. Anat. 1867;3:215–247. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Nilsson S.E.G. Receptor cell outer segment development and ultrastructure of the disk membranes in the retina of the tadpole (Rana pipiens) J. Ultrastruct. Res. 1964;11:581–602. doi: 10.1016/s0022-5320(64)80084-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kinney M.S., Fisher S.K. The photoreceptors and pigment epithelium of the larval Xenopus retina: morphogenesis and outer segment renewal. Proc. R. Soc. Lond. B Biol. Sci. 1978;201:149–167. doi: 10.1098/rspb.1978.0037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kinney M.S., Fisher S.K. The photoreceptors and pigment epithelim of the adult Xenopus retina: Morphogenesis and outer segment renewal. Proc. R. Soc. Lond. B Biol. Sci. 1978;201:149–167. doi: 10.1098/rspb.1978.0037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Obata S., Usukura J. Morphogenesis of the photoreceptor outer segment during postnatal development in the mouse (BALB/c) retina. Cell Tissue Res. 1992;269:39–48. doi: 10.1007/BF00384724. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Usukura J., Obata S. Morphogenesis of photoreceptor outer segments in retinal development. Prog. Retin. Eye Res. 1995;15:113–125. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lamb T.D., Collin S.P., Pugh E.N., Jr. Evolution of the vertebrate eye: opsins, photoreceptors, retina and eye cup. Nat. Rev. Neurosci. 2007;8:960–976. doi: 10.1038/nrn2283. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Fain G.L., Hardie R., Laughlin S.B. Phototransduction and the evolution of photoreceptors. Curr. Biol. 2010;20:R114–R124. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2009.12.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Eckmiller M.S. Cone outer segment morphogenesis: taper change and distal invaginations. J. Cell Biol. 1987;105:2267–2277. doi: 10.1083/jcb.105.5.2267. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Eckmiller M.S. Outer segment growth and periciliary vesicle turnover in developing photoreceptors of Xenopus laevis. Cell Tissue Res. 1989;255:283–292. doi: 10.1007/BF00224110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kawamura S., Tachibanaki S. Rod and cone photoreceptors: molecular basis of the difference in their physiology. Comp. Biochem. Physiol. A Mol. Integr. Physiol. 2008;150:369–377. doi: 10.1016/j.cbpa.2008.04.600. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Young R.W. Visual cells and the concept of renewal. Invest. Ophthalmol. Vis. Sci. 1976;15:700–725. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Young R.W. The daily rhythm of shedding and degradation of cone outer segment membranes in the lizard retina. J. Ultrastruct. Res. 1977;61:172–185. doi: 10.1016/s0022-5320(77)80084-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Bok D. Retinal photoreceptor-pigment epithelium interactions. Friedenwald lecture. Invest. Ophthalmol. Vis. Sci. 1985;26:1659–1694. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Eckmiller M.S. Distal invaginations and the renewal of cone outer segments in anuran and monkey retinas. Cell Tissue Res. 1990;260:19–28. doi: 10.1007/BF00297486. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Eckmiller M.S. Morphogenesis and renewal of cone outer segments. Prog. Ret. Eye Res. 1997;16:401–441. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Young R.W. An hypothesis to account for a basic distinction between rods and cones. Vision Res. 1971;11:1–5. doi: 10.1016/0042-6989(71)90201-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Bok D., Young R.W. The renewal of diffusely distributed protein in the outer segments of rods and cones. Vision Res. 1972;12:161–168. doi: 10.1016/0042-6989(72)90108-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Besharse J.C., Hollyfield J.G., Rayborn M.E. Turnover of rod photoreceptor outer segments. II. Membrane addition and loss in relationship to light. J. Cell Biol. 1977;75:507–527. doi: 10.1083/jcb.75.2.507. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Hollyfield J.G., Rayborn M.E. Membrane assembly in photoreceptor outer segments: progressive increase in ‘open’ basal discs with increased temperature. Exp. Eye Res. 1982;34:115–119. doi: 10.1016/0014-4835(82)90013-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Steinberg, R. H., S. K. Fisher, and D. H. Anderson. 1980. Disc morphogenesis in vertebrate photoreceptors. J. Comp. Neurol. 190:501–508. http://www.csmd.ucsb.edu/movie/. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 28.Sung C.-H., Chuang J.-Z. The cell biology of vision. J. Cell Biol. 2010;190:953–963. doi: 10.1083/jcb.201006020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Corless J.M., Fetter R.D. Structural features of the terminal loop region of frog retinal rod outer segment disk membranes: III. Implications of the terminal loop complex for disk morphogenesis, membrane fusion, and cell surface interactions. J. Comp. Neurol. 1987;257:24–38. doi: 10.1002/cne.902570104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Reference deleted in proof.

- 31.Besharse J.C., Pfenninger K.H. Membrane assembly in retinal photoreceptors I. Freeze-fracture analysis of cytoplasmic vesicles in relationship to disc assembly. J. Cell Biol. 1980;87:451–463. doi: 10.1083/jcb.87.2.451. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Mustafi D., Engel A.H., Palczewski K. Structure of cone photoreceptors. Prog. Retin. Eye Res. 2009;28:289–302. doi: 10.1016/j.preteyeres.2009.05.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Garlipp, M., and F. Gonzalez-Fernandez. 2010. Light-dependent interaction of interphotoreceptor retinoid-binding protein (IRBP) with Xenopus cone outer segments. 2010 ARVO Meeting Abstracts. Invest. Ophthalmol. Vis. Sci. 51:E-Abstract 1896.

- 34.Corless, J. M., R. D. Fetter, and E. Worniałło. 1988. The modulation of disk margin structure and lamellar membrane area during renewal of vertebrate cone outer segments (COSs). 8th International Congress of Eye Research, San Francisco, CA, 4–8 September. Meeting Abstracts, 162.

- 35.Corless J.M., Worniałło E. The integration of disk renewal, patterns of connectivity and shape determination in frog cone outer segments (COSs). 1989 ARVO Meeting Abstracts. Invest. Ophthalmol. Vis. Sci. 1989;30(3, Suppl):156. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Corless J.M., Worniałło E., Schneider T.G. Three-dimensional membrane crystals in amphibian cone outer segments: 2. Crystal type associated with the saddle point regions of cone disks. Exp. Eye Res. 1995;61:335–349. doi: 10.1016/s0014-4835(05)80128-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Corless, J. M. (2011) How do cone outer segments (COSs) maintain their conical shapes? 2011 ARVO Meeting Abstracts. Invest. Ophthalmol. Vis. Sci. 52:E-Abstract 5428.

- 38.Olbrich K., Rawicz W., Evans E. Water permeability and mechanical strength of polyunsaturated lipid bilayers. Biophys. J. 2000;79:321–327. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(00)76294-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Rawicz W., Olbrich K.C., Evans E. Effect of chain length and unsaturation on elasticity of lipid bilayers. Biophys. J. 2000;79:328–339. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(00)76295-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Teller D.C., Okada T., Stenkamp R.E. Advances in determination of a high-resolution three-dimensional structure of rhodopsin, a model of G-protein-coupled receptors (GPCRs) Biochemistry. 2001;40:7761–7772. doi: 10.1021/bi0155091. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Sachs F. Stretch-activated ion channels: what are they? Physiology (Bethesda) 2010;25:50–56. doi: 10.1152/physiol.00042.2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Borwein B. The retinal receptor: a description. In: Enoch J.M., Tobey F.L. Jr., editors. Vertebrate Photoreceptor Optics. Springer-Verlag; New York: 1981. pp. 11–81. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Chabre M. X-ray diffraction studies of retinal rods. I. Structure of the disc membrane, effect of illumination. Biochim. Biophys. Acta. 1975;382:322–335. doi: 10.1016/0005-2736(75)90274-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Blaurock A.E., Wilkins M.H.F. Structure of frog photoreceptor membranes. Nature. 1969;223:906–909. doi: 10.1038/223906a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Chabre M., Cavaggioni A. Light induced changes in ionic flux in the retinal rod. Nat. New Biol. 1973;244:118–120. doi: 10.1038/newbio244118a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Webb N.G. X-ray diffraction from outer segments of visual cells in intact eyes of the frog. Nature. 1972;235:44–46. doi: 10.1038/235044a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Najafi M., Maza N.A., Calvert P.D. Steric volume exclusion sets soluble protein concentrations in photoreceptor sensory cilia. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2012;109:203–208. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1115109109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Blaurock A.E. What x-ray and neutron diffraction contribute to understanding the structure of the disk membrane. In: Barlow H.B., Fatt P., editors. Vertebrate Photoreception. Academic Press; New York: 1977. pp. 61–76. [Google Scholar]

- 49.Sardet C., Tardieu A., Luzzati V. Shape and size of bovine rhodopsin: a small-angle x-ray scattering study of a rhodopsin-detergent complex. J. Mol. Biol. 1976;105:383–407. doi: 10.1016/0022-2836(76)90100-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Nagle J.F., Tristram-Nagle S. Structure of lipid bilayers. Biochim. Biophys. Acta. 2000;1469:159–195. doi: 10.1016/s0304-4157(00)00016-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Needham D., Nunn R.S. Elastic deformation and failure of lipid bilayer membranes containing cholesterol. Biophys. J. 1990;58:997–1009. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(90)82444-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Rawicz W., Smith B.A., Evans E. Elasticity, strength, and water permeability of bilayers that contain raft microdomain-forming lipids. Biophys. J. 2008;94:4725–4736. doi: 10.1529/biophysj.107.121731. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Arikawa K., Molday L.L., Williams D.S. Localization of peripherin/rds in the disk membranes of cone and rod photoreceptors: relationship to disk membrane morphogenesis and retinal degeneration. J. Cell Biol. 1992;116:659–667. doi: 10.1083/jcb.116.3.659. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Boesze-Battaglia K., Goldberg A.F.X. Photoreceptor renewal: a role for peripherin/rds. Int. Rev. Cytol. 2002;217:183–225. doi: 10.1016/s0074-7696(02)17015-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Kedzierski W., Moghrabi W.N., Travis G.H. Three homologs of rds/peripherin in Xenopus laevis photoreceptors that exhibit covalent and non-covalent interactions. J. Cell Sci. 1996;109:2551–2560. doi: 10.1242/jcs.109.10.2551. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Conley S.M., Naash M.I. Focus on molecules: RDS. Exp. Eye Res. 2009;89:278–279. doi: 10.1016/j.exer.2009.03.023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Papermaster D.S., Reilly P., Schneider B.G. Cone lamellae and red and green rod outer segment disks contain a large intrinsic membrane protein on their margins: an ultrastructural immunocytochemical study of frog retinas. Vision Res. 1982;22:1417–1428. doi: 10.1016/0042-6989(82)90204-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Molday R.S. ATP-binding cassette transporter ABCA4: molecular properties and role in vision and macular degeneration. J. Bioenerg. Biomembr. 2007;39:507–517. doi: 10.1007/s10863-007-9118-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Yatsenko A.N., Wiszniewski W., Lupski J.R. Evolution of ABCA4 proteins in vertebrates. J. Mol. Evol. 2005;60:72–80. doi: 10.1007/s00239-004-0118-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Moritz O.L., Molday R.S. Molecular cloning, membrane topology, and localization of bovine rom-1 in rod and cone photoreceptor cells. Invest. Ophthalmol. Vis. Sci. 1996;37:352–362. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Rattner A., Smallwood P.M., Nathans J. A photoreceptor-specific cadherin is essential for the structural integrity of the outer segment and for photoreceptor survival. Neuron. 2001;32:775–786. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(01)00531-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Rattner A., Chen J., Nathans J. Proteolytic shedding of the extracellular domain of photoreceptor cadherin. Implications for outer segment assembly. J. Biol. Chem. 2004;279:42202–42210. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M407928200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Maw M.A., Corbeil D., Denton M.J. A frameshift mutation in prominin (mouse)-like 1 causes human retinal degeneration. Hum. Mol. Genet. 2000;9:27–34. doi: 10.1093/hmg/9.1.27. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Corbeil D., Röper K., Huttner W.B. Prominin: a story of cholesterol, plasma membrane protrusions and human pathology. Traffic. 2001;2:82–91. doi: 10.1034/j.1600-0854.2001.020202.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Yang Z., Chen Y., Zhang K. Mutant prominin 1 found in patients with macular degeneration disrupts photoreceptor disk morphogenesis in mice. J. Clin. Invest. 2008;118:2908–2916. doi: 10.1172/JCI35891. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Jászai J., Fargeas C.A., Corbeil D. Focus on molecules: prominin-1 (CD133) Exp. Eye Res. 2007;85:585–586. doi: 10.1016/j.exer.2006.03.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Zacchigna S., Oh H., Carmeliet P. Loss of the cholesterol-binding protein prominin-1/CD133 causes disk dysmorphogenesis and photoreceptor degeneration. J. Neurosci. 2009;29:2297–2308. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.2034-08.2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Andrews L.D., Cohen A.I. Freeze-fracture evidence for the presence of cholesterol in particle-free patches of basal disks and the plasma membrane of retinal rod outer segments of mice and frogs. J. Cell Biol. 1979;81:215–228. doi: 10.1083/jcb.81.1.215. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Andrews L.D., Cohen A.I. Freeze-fracture studies of photoreceptor membranes: new observations bearing upon the distribution of cholesterol. J. Cell Biol. 1983;97:749–755. doi: 10.1083/jcb.97.3.749. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Wensel, T. G., J. C. Gilliam, …, W. Chiu. (2011) Electron cryo-tomography of cilia-associated structures of rod photoreceptors. 2011 ARVO Meeting Abstracts. Invest. Ophthalmol. Vis. Sci. 52: E-Abstract 4403.

- 71.Hibbeler R.C. 3rd ed. Prentice Hall; Upper Saddle River, NJ: 1997. Mechanics of Materials. Appendix C. Slopes and Deflections of Beams, 804–805. [Google Scholar]

- 72.Liebman P.A. Microspectrophotometry of photoreceptors. In: Dartnall H.J.A., editor. Photochemistry of Vision. Springer-Verlag; New York: 1972. pp. 481–528. [Google Scholar]

- 73.Stell W.K., Hárosi F.I. Cone structure and visual pigment content in the retina of the goldfish. Vision Res. 1976;16:647–657. doi: 10.1016/0042-6989(76)90013-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Röhlich P., Szél A. Photoreceptor cells in the Xenopus retina. Microsc. Res. Tech. 2000;50:327–337. doi: 10.1002/1097-0029(20000901)50:5<327::aid-jemt2>3.3.co;2-g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Corless J.M., Worniałło E., Fetter R.D. Three-dimensional membrane crystals in amphibian cone outer segments. 1. Light-dependent crystal formation in frog retinas. J. Struct. Biol. 1994;113:64–86. doi: 10.1006/jsbi.1994.1033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Reference deleted in proof.

- 77.Liang Y.D., Fotiadis D., Engel A. Organization of the G protein-coupled receptors rhodopsin and opsin in native membranes. J. Biol. Chem. 2003;278:21655–21662. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M302536200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Eckmiller M.S. Shifting distribution of autoradiographic label in cone outer segments and its implications for renewal. J. Hirnforsch. 1993;34:179–191. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Nagle B.W., Okamoto C., Burnside B. The teleost cone cytoskeleton. Localization of actin, microtubules, and intermediate filaments. Invest. Ophthalmol. Vis. Sci. 1986;27:689–701. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Alberts, B., A. Johnson, …, P. Walter (editors). 2008. Molecular Biology of the Cell, 5th ed. Garland Science, New York. 1036-1041.

- 81.Chaitin M.H., Schneider B.G., Papermaster D.S. Actin in the photoreceptor connecting cilium: immunocytochemical localization to the site of outer segment disk formation. J. Cell Biol. 1984;99:239–247. doi: 10.1083/jcb.99.1.239. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Chaitin M.H., Burnside B. Actin filament polarity at the site of rod outer segment disk morphogenesis. Invest. Ophthalmol. Vis. Sci. 1989;30:2461–2469. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Arikawa K., Williams D.S. Organization of actin filaments and immunocolocalization of alpha-actinin in the connecting cilium of rat photoreceptors. J. Comp. Neurol. 1989;288:640–646. doi: 10.1002/cne.902880410. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Williams D.S. Actin filaments and photoreceptor membrane turnover. Bioessays. 1991;13:171–178. doi: 10.1002/bies.950130405. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Kwok M.C.M., Holopainen J.M., Molday R.S. Proteomics of photoreceptor outer segments identifies a subset of SNARE and Rab proteins implicated in membrane vesicle trafficking and fusion. Mol. Cell. Proteomics. 2008;7:1053–1066. doi: 10.1074/mcp.M700571-MCP200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Fetter, R. D. 1986. Studies on the structure of frog retinal photoreceptor outer segments and disk morphogenesis. PhD thesis. Duke University, Durham, NC.

- 87.Maerker T., van Wijk E., Wolfrum U. A novel Usher protein network at the periciliary reloading point between molecular transport machineries in vertebrate photoreceptor cells. Hum. Mol. Genet. 2008;17:71–86. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddm285. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Dosé A.C., Hillman D.W., Burnside B. Myo3A, one of two class III myosin genes expressed in vertebrate retina, is localized to the calycal processes of rod and cone photoreceptors and is expressed in the sacculus. Mol. Biol. Cell. 2003;14:1058–1073. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E02-06-0317. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Pagh-Roehl K.E.W., Wang E., Burnside B. Shortening of the calycal process actin cytoskeleton is correlated with myoid elongation in teleost rods. Exp. Eye Res. 1992;55:735–746. doi: 10.1016/0014-4835(92)90178-u. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Hale I.L., Fisher S.K., Matsumoto B. The actin network in the ciliary stalk of photoreceptors functions in the generation of new outer segment discs. J. Comp. Neurol. 1996;376:128–142. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1096-9861(19961202)376:1<128::AID-CNE8>3.0.CO;2-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Vaughan D.K., Fisher S.K. The distribution of F-actin in cells isolated from vertebrate retinas. Exp. Eye Res. 1987;44:393–406. doi: 10.1016/s0014-4835(87)80173-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Williams D.S., Hallett M.A., Arikawa K. Association of myosin with the connecting cilium of rod photoreceptors. J. Cell Sci. 1992;103:183–190. doi: 10.1242/jcs.103.1.183. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.