Abstract

Intrapulmonary arteriovenous anastomoses (IPAVS) directly connect the arterial and venous circulations in the lung, bypassing the capillary network. Here, we used solid, latex microspheres and isolated rat lung and intact, spontaneously breathing rat models to test the hypothesis that IPAVS are recruited by alveolar hypoxia. We found that hypoxia recruits IPAVS in the intact rat, but not the isolated lung. IPAVS are at least 70 μm in the rat and, interestingly, appear to be recruited when the mixed venous Po2 falls below 22 mmHg. These data provide evidence that large-diameter, direct arteriovenous connections exist in the lung and are recruitable by hypoxia in the intact animal.

Keywords: arteriovenous anastamoses, hypoxia, intrapulmonary shunts, lung, microspheres

inducible intrapulmonary arteriovenous anastamoses (IPAVS) are large-diameter pathways that connect the pulmonary arterial and venous circulations, bypassing the lung's capillaries. Studies using saline contrast echocardiography demonstrate that IPAVS are closed in healthy, adult humans, breathing room air [fractional inspired O2 (FiO2) = 0.21] at rest (7, 8, 15, 18, 19). However, they are recruited with exercise at ≥60% of maximal exercise capacity in most individuals (7). Indeed, transpulmonary bubble passage has been observed in ∼90% of participants tested while performing maximal exercise in our laboratory. Exercise with hypoxia (FiO2 = 0.12) causes the pathways to be recruited at lower workloads (18) than with normoxia and IPAVS can be recruited at rest in many individuals breathing an FiO2 < 0.10 (15). Hyperoxia apparently closes these pathways, preventing the passage of saline bubble contrast, even with high-intensity exercise (19).

However, saline bubble echocardiography is limited in that it provides only qualitative measurements of IPAVS recruitment (12). Furthermore, saline contrast yields no information about IPAVS diameter. Thus, although saline contrast is a useful, minimally invasive tool for making repeated measures of IPAVS recruitment in humans, there is an additional need for a model using solid particles of known diameter to investigate the mechanism of IPAVS recruitment and their impact on gas exchange. We have previously used 25-μm solid microspheres in dogs to verify the recruitment of IPAVS during normoxic exercise. Here, we aimed to establish a rat model of IPAVS recruitment in hypoxia and to determine the diameter of IPAVS in this species.

We conducted four experiments using our previously described fluorescent microsphere method to test the hypothesis that IPAVS > 50 μm are recruited by alveolar hypoxia in the rat. In the first experiment, we ventilated isolated rat lungs with normoxic (FiO2 = 0.21) or hypoxic gas (FiO2 = 0.08) and assessed whether large-diameter microspheres traverse the lung under each condition. When we found that hypoxia did not recruit IPAVS in the isolated rat lung, we conducted a second experiment in which we exposed intact, anesthetized, spontaneously breathing rats to normoxic or hypoxic gas (FiO2 = 0.12) and found evidence of transpulmonary microsphere passage in hypoxia. In the third and fourth experiments, we varied the microsphere size to determine IPAVS diameter and investigated the effect of varying the FiO2 on IPAVS recruitment.

METHODS

Male Sprague-Dawley (250–350 g) rats (Harlan Laboratories) were maintained in standard animal housing on a 12:12-h light-dark cycle and offered water and chow ad libitum. All protocols were approved by the institutional animal care and use committee at the University of Wisconsin-Madison. Each of the experiments described in detail in subsequent sections used the same general approach. Isolated lungs or intact rats were exposed to normoxic or hypoxic gas for 5 min with IPAVS recruitment assessed by quantifying the transpulmonary passage of microspheres. Blood gases were always obtained before the injection of microspheres. Additionally, we dissected, examined, and probed the atrial and ventricular septa of all rats reported in this manuscript. Two rats with evidence of an atrial-level shunt were excluded from our data set. Careful postmortem analysis of the animals included in our data set revealed no intracardiac conduit, including a patent foramen ovale, that could allow for transcardiac microsphere passage.

Experiment 1: effect of alveolar hypoxia on IPAVS recruitment in isolated lungs.

Lungs were isolated and prepared using previously well-described methods (5, 6, 20, 32). Briefly, rats were anesthetized with ketamine and xylazine (50–100 mg/kg and 5 mg/kg ip) and secured supine. A polyethylene catheter was placed in the femoral vein and infused with heparin (6,000 U/kg) to prevent lung thrombus formation during isolation. The femoral artery was then cut and blood was flushed from the animal by perfusing 10 ml isotonic phosphate-buffered saline (PBS, pH = 7.4) into the femoral vein. The trachea was isolated, cannulated with polyethylene tubing, and the lungs inflated with 5 ml of air. A midline sternotomy was performed, the chest wall removed, and fluid-filled polyethylene catheters were placed in the pulmonary artery and left atrium. Lungs were left in situ in the thorax and 3 ml PBS was added to the chest cavity to prevent dehydration and to minimize friction between the lung and chest wall. The lungs were mechanically ventilated with FiO2 = 0.08 (n = 5) or 0.21 (n = 4), balance N2, 30–45 times per minute (3–4 ml/inflation) to a peak inflation pressure of 15 cmH2O with 5 cmH2O end-expiratory pressure.

The pulmonary arterial catheter was connected to a continuous-flow reservoir system containing 5% albumin in heparinized PBS (1,000 U/l, pH = 7.4). This reservoir was supplied by a pump and had an overflow outlet so that the height of the fluid column could be maintained at a constant level. The perfusion pressure was thus determined by the height of the fluid column above the pulmonary artery, which we set to 20 cmH2O. The left atrial catheter was maintained at the level of the atrium so that the outlet pressure equaled 0 cmH2O and the entire left atrial effluent was collected. Lungs were ventilated and perfused for 5 min before beginning our study protocol.

One million 15 ± 12% μm green fluorescent microspheres (Duke Scientific) were suspended in 4 ml PBS as previously described (20) and injected in four 1-ml boluses (1/4 of 4 ml with 250,000 microspheres per bolus) via an injection port in the pulmonary artery catheter. Microspheres were injected in multiple boluses over 20 min, instead of as a single injection, to minimize the risk of microsphere clumping in large-diameter vessels. The entire left atrial effluent was vortexed and vacuum filtered through a filter with 8-μm pores (Millipore, Billerica, MA). Microspheres trapped in the filters were imaged using a fluorescent microscope and counted.

Experiment 2: effect of alveolar hypoxia on IPAVS recruitment in intact rats.

Rats were anesthetized with ketamine and xylazine (50–100 mg/kg and 5 mg/kg ip) and placed on an electric homeothermic blanket. Body temperature was measured with a rectal probe and the blanket was adjusted to maintain a body temperature of 36–38°C. Once a surgical plane of anesthesia was verified, the neck was exposed and the right carotid artery and jugular vein were isolated. A 0.5-mm microtip pressure-volume catheter (Millar Instruments, MPVS Ultra and SPR-839, Houston, TX) was introduced via the carotid artery into the left ventricle to measure left ventricular pressure and volumes. Pressure-volume data were acquired with a PowerLab data acquisition device and analyzed using the LabChart software package (AD Instruments, Colorado Springs, CO) (24). Before each use, the catheter was calibrated according to the manufacturer's instructions using a sample of each animal's own blood. The electronic pressure calibration was verified before use (Veri-Cal, Utah Medical Products, Midvale, UT).

To measure right ventricular pressure, a Tygon catheter (0.010 in. ID, 0.030 in. OD) was connected to a pressure transducer (Hospira, Lake Forest, IL) and introduced into the right ventricle via the jugular vein. The final location of the catheter was assessed by monitoring the pressure waveform during placement and was verified postmortem. A second polyethylene catheter was introduced into the superior vena cava via the same jugular vein for microsphere injection. A third polyethylene catheter was placed in the femoral artery for blood gas analysis. Rats were then sealed into a custom-built Plexiglas chamber that was equipped with inlet and outlet ports that were used to flush the condition gas through the chamber. The FiO2 in the chamber was monitored continuously at the outlet port (MiniOx I, MSA, Cranberry Township, PA). The chamber was flushed (15 l/min) with FiO2 = 0.12 or 0.21, balance N2, until the inlet and outlet FiO2 was equal. An FiO2 of 0.12 was chosen because it resulted in an alveolar Po2 (PaO2) similar to that of the isolated lungs ventilated with FiO2 = 0.08 (PaO2 = 57 mmHg in isolated lungs vs. 54 mmHg in intact rats). PaO2 in intact rats was estimated from the alveolar gas equation, based on the assumption that arterial Pco2 (PaCO2) equaled that in alveolar gas and that the respiratory quotient = 0.8.

After a 5-min exposure to either 12 (n = 6) or 21% O2 (n = 5), 1 ml of arterial blood was drawn from the femoral arterial catheter for blood gas analysis. Samples were run in duplicate (pHOx Basic, Nova Biomedical, Waltham, MA) and corrected for body temperature. A three-point calibration was done daily using manufacturer-supplied control solutions with known values of Po2, Pco2, and pH. One million 15-μm green fluorescent microspheres were then injected into the superior vena cava and the rat was euthanized by exsanguination. The kidneys were removed, embedded in Tissue-Tek, and flash-frozen in liquid nitrogen. Samples were stored at −20°C until analysis.

A single kidney was chosen at random from each intact rat studied and sliced into sections four times the thickness of the microspheres contained in the tissue. We found that this thickness allowed the microspheres to be easily visualized and that broken or damaged microspheres were seen rarely. The sections were placed on slides, imaged with a fluorescent microscope, and the number of microspheres in each slice was quantified. Every slice was imaged and counted and <5% of the slices were lost or damaged during the sectioning process. To ensure that we had accurately counted the number of microspheres in the kidney slices, we counted the front and back of 10% of the slices and found near-perfect agreement (±1 microsphere).

Experiment 3: assessment of IPAVS size.

Under anesthesia, a polyethylene catheter was placed in the femoral artery for blood gas analysis and femoral vein for microsphere injection. The rat was then placed in the previously described Plexiglas chamber and exposed to FiO2 = 0.12. After 5 min, blood gases were drawn to verify that the rat was hypoxemic. Each rat received an injection of one million microspheres of a single size (10 μm ± 18%, 25 μm ± 12%, 50 μm ± 12%, or 70 μm ± 7%, n = 4 each group, total n = 16) via the femoral catheter. Each rat received an injection of a single microsphere size. The rat was then euthanized by exsanguination and the kidneys were collected and analyzed as described.

Experiment 4: relation between FiO2 and IPAVS recruitment.

Rats were instrumented with left heart, right heart, femoral artery, and superior vena cava catheters as described. They were then placed in the Plexiglas chamber and the chamber was ventilated such that each rat was exposed to a single FiO2 within the range of 0.03–0.21 (n = 24 total). Blood was drawn from the right ventricular and femoral arterial catheters (1 ml total volume) and blood gases were analyzed as described. One million 25-μm microspheres were injected into the superior vena cava catheter. The animals were euthanized and the kidneys were collected and analyzed as described.

Data analysis.

Hemodynamic and blood gas data were analyzed using a Student's t-test and significance set at P < 0.05 with a Bonferroni correction to account for multiple comparisons. The effect of oxygen tension on microsphere passage was assessed using a nonparametric Mann-Whitney test with significance set at P < 0.05 (Minitab, State College, PA). Linear regression was used to evaluate the relation between microsphere passage and FiO2, PvO2, and PaO2. Data are reported as means ± SD.

RESULTS

Experiment 1: effect of alveolar hypoxia on IPAVS recruitment (isolated lungs).

The number of microspheres found in the venous effluent of isolated rat lungs with normoxic and hypoxic ventilation was equal and trivial (78 ± 62 vs. 61 ± 46, P = 0.90), translating to mean transpulmonary microsphere passage <0.01% (Table 1). Perfusate flow was higher in normoxia ventilated isolated lungs (8.9 ± 1.3 ml/min) than hypoxia ventilated lungs (5.1 ± 1.3 ml/min, P = 0.005) and tended to decline, although not significantly, as a result of the injection of 1 × 106 microspheres (7.5 ± 1.5 ml/min in normoxia, P = 0.16 vs. 2.8 ± 1.8 ml/min in hypoxia, P = 0.08).

Table 1.

The effect of fractional inspired oxygen on the transpulmonary passage of 15-μm microspheres in isolated rat lungs

| Group 1: Normoxia (FiO2 = 0.21) | Group 2: Hypoxia (FiO2 = 0.08) | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Lung 1 | 35 | Lung 1 | 20 |

| Lung 2 | 71 | Lung 2 | 25 |

| Lung 3 | 14 | Lung 3 | 112 |

| Lung 4 | 173 | Lung 4 | 87 |

| Lung 5 | 95 | ||

| Mean ± SD | 78 ± 62 | Mean ± SD | 61 ± 46 |

Hypoxia did not enhance the transpulmonary passage of microspheres. FiO2, fractional inspired oxygen.

Experiment 2: effect of alveolar hypoxia on IPAVS recruitment (intact rats).

As expected, hypoxia (FiO2 = 0.12) depressed arterial Po2 relative to normoxia (28.8 ± 6.9 vs. 65.4 ± 4.4 mmHg, P < 0.001), although rats exposed to normoxia still demonstrated arterial hypoxemia that may have been caused by regional lung atelectasis in these spontaneously breathing animals. There was no difference in arterial Pco2 (23.8 ± 7.7 vs. 28.1 ± 7.7 mmHg, P = 0.43) or pH (7.41 ± 0.19 vs. 7.38 ± 0.15, P = 0.79). Hypoxia increased the number of 15-μm microspheres that bypassed the pulmonary circulation and lodged in the kidney (0 ± 1 vs. 1,119 ± 1,925, P = 0.008) (see Table 2). More than 100 microspheres were observed in the single kidneys of five of six rats exposed to hypoxia. Two microspheres were observed in the kidney of only a single rat exposed to normoxia. No microspheres were observed in the kidneys of the remaining four rats. Again, we note the passage of 100 microspheres as important because, assuming the kidney receives 10% of the cardiac output, this translates to 0.1% of the microspheres having bypassed the lung.

Table 2.

Number of 15-μm microspheres found in the kidneys of intact, spontaneously breathing rats exposed to normoxia or hypoxia

| Group 1: Normoxia (FiO2 = 0.21) | Group 2: Hypoxia (FiO2 = 0.12) | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Rat 1 | 0 | Rat 1 | 11 |

| Rat 2 | 0 | Rat 2 | 204 |

| Rat 3 | 0 | Rat 3 | 5,004 |

| Rat 4 | 2 | Rat 4 | 380 |

| Rat 5 | 0 | Rat 5 | 859 |

| Rat 6 | 254 | ||

| Mean ± SD | 0 ± 1 | Mean ± SD | 1,119 ± 1,925* |

Exposure to FiO2 = 0.08 increased the number of microspheres found in the kidney compared with exposure to FiO2 = 0.21 (* P = 0.008).

The effects of hypoxia and microsphere injection on cardiopulmonary hemodynamics are given in Table 3. As expected, hypoxia elevated the right ventricular systolic pressure and, consequently, the total pulmonary vascular resistance relative to normoxia. Rats exposed to hypoxia demonstrated no hemodynamic changes in response to microsphere injection. Microsphere injection in normoxia caused a transient 10-mmHg increase in right ventricular systolic pressure (P = 0.005) that resolved at the termination of the injection, but no other hemodynamic changes were noted.

Table 3.

Right heart pressure and cardiac output in intact, spontaneously breathing rats exposed to normoxia (n = 5) or hypoxia n = 6)

| Heart Rate, beats/min | Stroke Volume, μl | Cardiac Output, ml/min | RV Systolic Pressure, mmHg | RV Diastolic Pressure, mmHg | Resistance, mmHg · ml−1 · min* | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Group 1: FiO2 =0.21 | ||||||

| Preinjection | 319 ± 123 | 90.8 ± 28.7 | 29 ± 9 | 19 ± 3 | 3 ± 5 | 0.7 ± 0.4 |

| Injection | 289 ± 16 | 126.9 ± 34.6 | 36 ± 8 | 29 ± 1† | 5 ± 4 | 0.8 ± 0.2 |

| Postinjection | 323 ± 30 | 98.9 ± 30.0 | 32 ± 10 | 22 ± 1 | 4 ± 5 | 0.8 ± 0.3 |

| Group 2: FiO2 = 0.12 | ||||||

| Preinjection | 283 ± 47 | 73 ± 18 | 21 ± 7 | 44 ± 11† | 3 ± 7 | 2.3 ± 0.9† |

| Injection | 268 ± 32 | 94 ± 30 | 25 ± 7 | 48 ± 11 | 6 ± 7 | 2.1 ± 0.9 |

| Postinjection | 265 ± 27 | 78 ± 29 | 21 ± 9 | 45 ± 14 | 6 ± 7 | 2.4 ± 1.1 |

Values are means ± SD.

Right ventricular systolic pressure is used as a surrogate for pulmonary artery systolic pressure. Thus total pulmonary vascular resistance is approximated as the quotient of the right ventricular systolic pressure and cardiac output.

P < 0.05 compared with preinjection in normoxia, adjusted for multiple comparisons.

Experiment 3: assessment of IPAVS size.

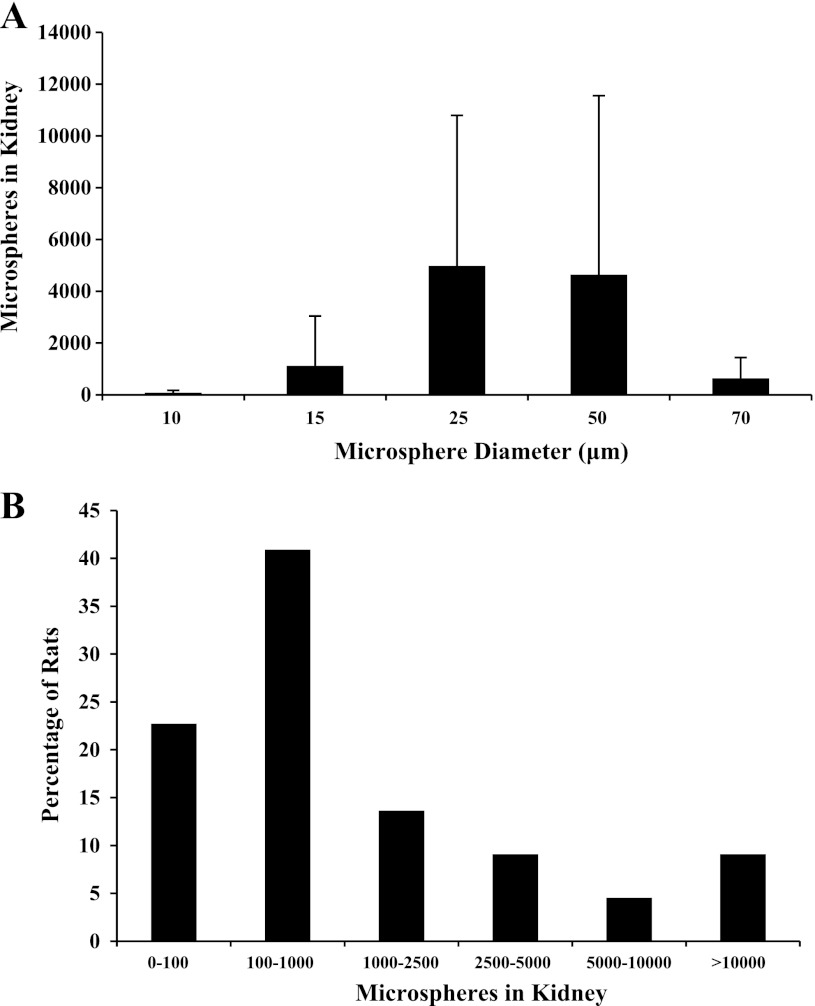

More than 100 microspheres were found in the single kidney of two of four hypoxemic rats injected with 10-μm microspheres (79 ± 93), five of six rats injected with 15-μm microspheres (1,119 ± 1,925, data from experiment 2), three of four rats injected with 25-μm microspheres (4,979 ± 5,815), three of four rats injected with 50-μm microspheres (4,641 ± 6,913), and four of four rats injected with 70-μm microspheres (637 ± 801) (Fig. 1A). The injection of 70-μm microspheres within the range of microsphere numbers that could be injected reproducibly (2.5 × 105 to 2 × 106) resulted in death within 5 min of injection. For that reason, larger sizes were not attempted in intact animals. Although the mean number of microspheres lodged in the kidney appears higher for the 25- and 50-μm spheres, the SD is also quite high. The higher mean is the result of one rat in each group with a very large number of microspheres (>10,000) and one rat in each group with <100 microspheres. An ANOVA revealed no overall effect of sphere size on the number of microspheres lodged in the kidney (P = 0.27). Therefore, data were pooled and are shown in Fig. 1B. Assuming that the each kidney receives 10% of the cardiac output, and that this is unchanged by hypoxia, this translates to 2.2 ± 4.1% of the microspheres having bypassed the pulmonary circulation in the hypoxic condition. This is certainly an underestimation given that exposure to hypoxia decreases the renal blood flow ∼40% in the anesthetized rat (22).

Fig. 1.

Number of microspheres observed in the kidney as a function of microsphere size (A) and distribution of transpulmonary microsphere passage (B) (n = 22). Transpulmonary microsphere passage was observed in 17/22 rats and microsphere size was not related to the number of microspheres found in the kidney (P = 0.27). In the total population, 2,170 ± 4,118 microspheres were found in the kidney.

Experiment 4: relation between FiO2 and IPAVS recruitment.

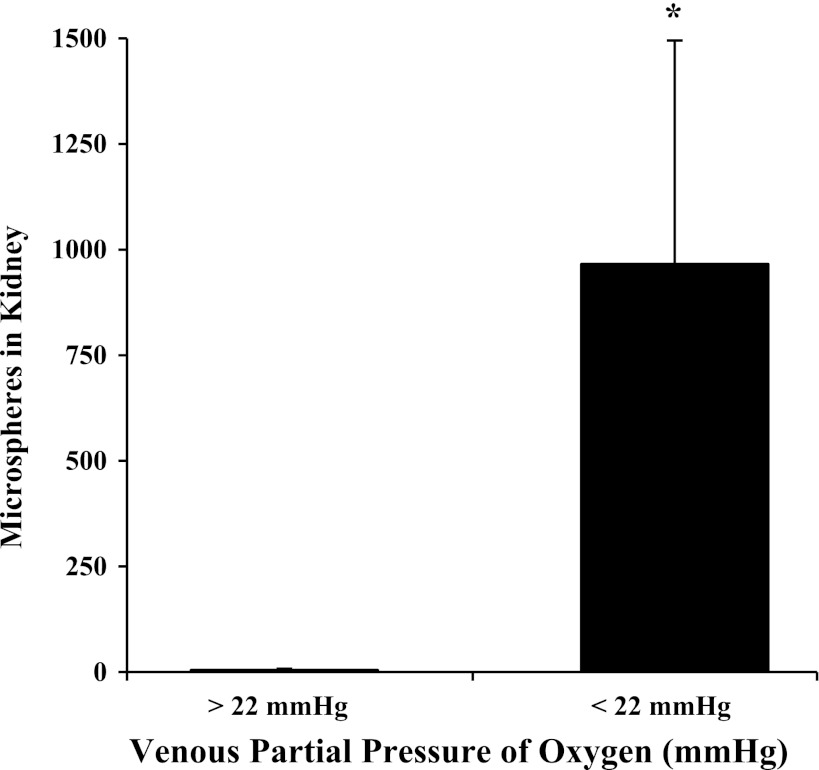

As expected, PaO2 (R2 = 0.88, P < 0.001), PvO2 (R2 = 0.52, P < 0.001), and PaCO2 (R2 = 0.54, P < 0.001) decreased with decreasing FiO2. However, decreasing FiO2 had no effect on PvCO2 (R2 = 0.07, P = 0.20). Very few 25-μm microspheres were found in the kidneys of rats with PaO2 > 30 mmHg and PvO2 > 22 mmHg (5 ± 3 microspheres, n = 16). However, more than 100 microspheres were found in the kidneys of six of eight rats with PaO2 < 30 mmHg and PvO2 < 22 mmHg (966 ± 529, P < 0.001) (see Fig. 2). There was no linear correlation between the number of microspheres found in the kidneys of hypoxic rats and FiO2, PvO2, or PaO2 (r2 < 0.10 and P > 0.05 for each comparison).

Fig. 2.

Number of 25-μm microspheres traversing the pulmonary circulation and lodging in the kidney in rats, divided based on the venous partial pressure of oxygen (PvO2). More than 100 microspheres were found in the kidneys of animals with PvO2 < 22 mmHg (n = 8, P < 0.001). Transpulmonary passage of microspheres was not seen in rats with PvO2 > 22 mmHg (n = 16).

DISCUSSION

We postulated that alveolar hypoxia would be sufficient to recruit IPAVS in isolated rat lungs and intact rats. Surprisingly, even a severe hypoxic stress that routinely recruits IPAVS in humans failed to recruit IPAVS in isolated lungs. This apparent negative finding, however, may provide insight into the anatomic location or regulation of IPAVS in the rat. In the intact rat, we found that hypoxia recruits IPAVS when PaO2 was <30 mmHg and PvO2 was <22 mmHg. Further, we show that IPAVS are at least 70 μm in diameter.

Why does hypoxia fail to recruit IPAVS in the isolated rat lung?

As we have done previously (32), we used both isolated lungs and intact animals to investigate IPAVS recruitment. We found transpulmonary microsphere passage in isolated lungs ventilated with normoxia, although the number of traversing microspheres was very low (0.008%). This is similar to our findings in baboon (0.01%), human (0.06%), and dog lungs (0.001%) (20, 32). Microsphere passage was not enhanced by hypoxia. There are several key differences between the intact animal and isolated lung that may explain our findings.

The lack of IPAVS recruitment in the isolated lung may provide clues about the anatomic location of these pathways. The isolated lung is perfused exclusively between the pulmonary artery and left atrium and lacks an intact bronchial circulation. Although we have generally referred to these pathways as “intrapulmonary” arteriovenous pathways, they may contain an intrabronchial component. The bronchial circulation contains both pre- and postcapillary anastomoses to the pulmonary circulation (30, 34) and the short, muscular Sperr arteries that anastomose the pulmonary arteries to the bronchial arteries may provide a site of active control. These connections are 35–100 μm in diameter in the neonatal lung and appear to functionally close after birth. They remain present in the adult lung and it is hypothesized that there may be physiological or pathological conditions that could lead to their reopening (10).

It is also possible that there are factors missing from the isolated lung that are necessary for IPAVS recruitment. For example, the sympathetic nervous system is activated by both exercise and hypoxia, and catecholamine-mediated vasodilation could explain IPAVS recruitment in both of these conditions. In dogs and humans, epinephrine infusion causes intrapulmonary shunting. This hypoxemia is reduced by 100% O2 breathing or propranolol infusion (2, 3). Furthermore, epinephrine infusion causes the transpulmonary passage of albumin microspheres in the dog (23). We have noted the passage of albumin macroaggregates in exercising humans and the cessation of transpulmonary bubble passage with 100% O2 breathing (17, 19). If a functional sympathetic nervous system is required, hypoxia would not recruit IPAVS in our isolated lung model that lacks innervation and circulating humoral factors.

As in our previous studies, the isolated lungs in these experiments were positive-pressure ventilated and perfused in situ with a room temperature 5% albumin solution that was exposed to the ambient environment. This albumin solution has a high Po2, low Pco2, and nonphysiological temperature. It is possible that these nonphysiological conditions prevented IPAVS recruitment in the isolated lung. Each of these variables may have an independent effect on IPAVS recruitment.

What recruits intrapulmonary arteriovenous anastomoses with hypoxia and exercise?

Although the original purpose of these experiments was to test the question of whether exposure to a hypoxia recruits IPAVS, our findings in the intact rat lend additional insight into the mechanism by which IPAVS are recruited. During exercise, especially at workloads where we have observed IPAVS recruitment, PvCO2 is elevated. However, PvCO2 did not change with hypoxia exposure in our experiments, providing evidence that elevated PvCO2 is not required for IPAVS recruitment. Also, the fact that the cardiac output was not elevated by hypoxia in our experiments suggests that increased pulmonary blood flow is also not required for IPAVS recruitment.

As expected, we did observe elevations in pulmonary vascular pressure with hypoxia exposure and cannot rule out the possibility that IPAVS recruitment is mediated by elevations in pulmonary artery pressure. Evidence in humans in support of pressure-mediated recruitment of these pathways is conflicting. For example, Stickland et al. (33) found that elevating pulmonary artery pressure had minimal impact on IPAVS recruitment in exercising humans. Laurie et al. (15) also found no causal relationship between the onset of IPAVS recruitment and ultrasound-assessed pulmonary artery pressure in human volunteers exposed to hypoxia. However, lower pulmonary artery pressures have been observed in exercising humans with evidence of IPAVS recruitment compared with those without (14).

We examined the effect of altering FiO2 on IPAVS recruitment and, as expected, arterial Po2 declined as a function of decreasing FiO2 and, interestingly, IPAVS recruitment occurred only with PaO2 < 30 mmHg and PvO2 < 22 mmHg. This PaO2 is much lower than those observed in humans with transpulmonary bubble passage (18) and, although we cannot rule out the potential confounding effect of anesthesia, we speculate that the signal for IPAVS recruitment may be on the venous side of the circulation. It is interesting that the PvO2 observed in our study when IPAVS were recruited is similar to the PvO2 during exercise and simulated altitude (27), although direct measurements of PvO2 and IPAVS recruitment have not been made simultaneously in humans or animals. Future studies in large-animal models, where the venous and arterial oxygen tensions can be isolated and controlled individually, would be valuable in testing this mechanism further.

How large are intrapulmonary arteriovenous anastomoses?

We used 15-μm microspheres to assess the fraction of blood flow bypassing the pulmonary capillary bed and traveling through direct intrapulmonary arteriovenous anastomoses. The rationale for choosing this size microsphere was based on data suggesting that greatest mean capillary diameter observed in greyhound lungs perfused at 37–74 mmHg is 6.5 μm and the largest capillaries observed were no larger than 13 μm (9). Still, we appreciate that one possible interpretation of the transpulmonary passage of 15-μm microspheres is passage through distended corner capillaries ≈20 μm (9, 28, 29). Rosenweig et al. (29) demonstrated the these corner capillaries are extensively recruited in zone 1, allowing arterially perfused dye to enter the pulmonary veins. To verify that we were observing the recruitment of true arteriovenous anastamoses and not the passage of microspheres through corner capillaries, we tested microspheres up to 70-μm diameter in intact rats exposed to hypoxia. The Strahler model of the rat vascular tree places 70-μm vessels at the level of fifth-generation pulmonary arteries (13). Assuming a corner capillary diameter of 20 μm, a 2% change in diameter per mmHg increase in capillary transmural pressure (11, 16, 26), and an initial transmural pressure equal to half the pulmonary artery (20 mmHg) and left atrial pressures (5 mmHg), 140 mmHg transmural pressure would be required to distend a corner capillary sufficiently to allow the passage of a 70-μm particle. Distension of a 6.5-μm alveolar capillary to 70 μm would require 488 mmHg transmural pressure. Thus it seems impossible that these large-diameter microspheres are passing through distended capillaries.

What are the clinical and pathological consequences of recruiting intrapulmonary arteriovenous anastomoses?

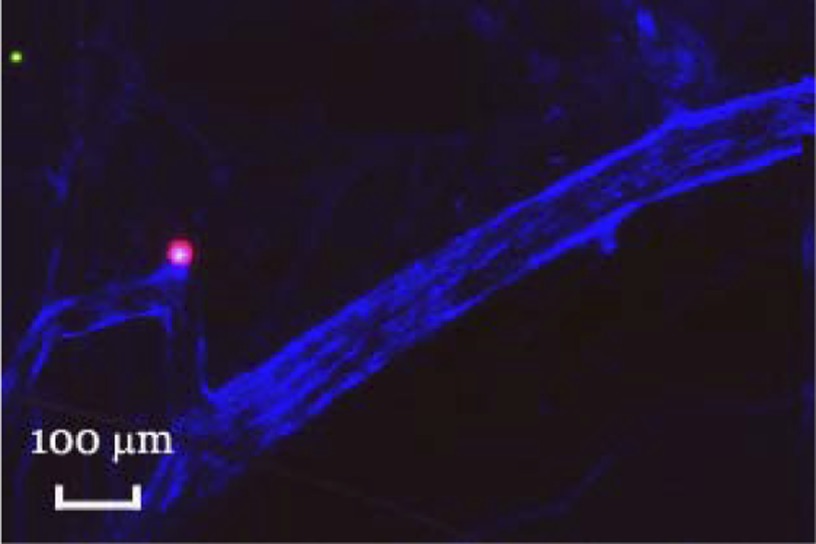

The ability to modulate IPAVS may have important clinical consequences. In addition to its role in gas exchange, the lung is an important biological filter and IPAVS provide a route by which large-diameter particles can bypass this filter. Fifty percent of pediatric strokes are cryptogenic, occurring in the absence of hypercoagulative state, trauma, infection, or apparent cardiovascular disease (4, 21). Paradoxical embolism (an arterial embolism caused by a thrombus with a venous origin) has been considered as a possible mechanism, but only 45% of stroke patients have a patent foramen ovale to allow these thrombi to bypass the lung filter (1). Direct arteriovenous connections may serve as an alternative pathway to allow potentially dangerous blood clots, air bubbles, fat particles, or parasites to bypass the lung filter and reach the brain. It is particularly relevant that emboli similar in size to our 70-μm microspheres cause function performance deficits when injected into the cerebral circulation in rats (25). We examined the brains of a small subset of rats and found cerebral embolization by our microspheres (Fig. 3).

Fig. 3.

Transverse section through the base of a rat brain. One million 15 (green)- and 33 (red)-μm spheres were injected into the superior vena cava, followed by 100 μl Evan's Blue dye to label the remaining patent vasculature. The brain was removed, embedded in Tissue Tek, sliced, and imaged confocally. Note that embolization by the 33-μm microsphere has disrupted perfusion.

Summary.

We demonstrate that IPAVS at least 70 μm in diameter are recruited by hypoxia in the intact rat. These findings support previous observations made in human research participants. Microspheres do not traverse the isolated hypoxic lung, but are found in the systemic circulation of intact, hypoxemic rats. Although the mechanism of recruitment remains unknown, microsphere passage is observed at PvO2 < 22 mmHg, suggesting a role for the mixed venous Po2 in IPAVS recruitment.

GRANTS

This work was supported by grants from the National Institutes of Health (5R01-HL-086897 and 5T32-HL-007654) and a postdoctoral fellowship from the American Heart Association.

DISCLOSURES

No conflicts of interest, financial or otherwise, are declared by the author(s).

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

Author contributions: M.L.B., B.R.F., E.T.F., A.D., D.F.P., R.L.C., and M.W.E. conception and design of research; M.L.B., B.R.F., A.D., and D.F.P. performed experiments; M.L.B., B.R.F., A.D., and M.W.E. analyzed data; M.L.B., E.T.F., D.F.P., R.L.C., and M.W.E. interpreted results of experiments; M.L.B. and M.W.E. prepared figures; M.L.B. and M.W.E. drafted manuscript; M.L.B., B.R.F., E.T.F., A.D., D.F.P., R.L.C., and M.W.E. edited and revised manuscript; M.L.B., B.R.F., E.T.F., A.D., D.F.P., R.L.C., and M.W.E. approved final version of manuscript.

REFERENCES

- 1. Ballerini L, Cifarelli A, Ammirati A, Gimigliano F. Patent foramen ovale and cryptogenic stroke. A critical review. J Cardiovasc Med 8: 34–38, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Berk JL, Hagen JF. Reduction of epinephrine-induced pulmonary shunt by oxygen breathing. Clin Res 26: A443–A443, 1978 [Google Scholar]

- 3. Berk JL, Hagen JF, Koo R. Effect of alpha and beta adrenergic blockade on epinephrine induced pulmonary insufficiency. Ann Surg 183: 369–376, 1976 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Carlin TM, Chanmugam A. Stroke in children. Emerg Med Clin North Am 20: 671, 2002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Conhaim RL, Harms BA. Perfusion of alveolar septa in isolated rat lungs in zone-1. J Appl Physiol 75: 704–711, 1993 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Conhaim RL, Watson KE, Heisey DM, Leverson GE, Harms BA. Thromboxane receptor analog, U-46619, redistributes pulmonary microvascular perfusion in isolated rat lungs. J Appl Physiol 96: 245–252, 2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Eldridge MW, Dempsey JA, Haverkamp HC, Lovering AT, Hokanson JS. Exercise-induced intrapulmonary arteriovenous shunting in healthy humans. J Appl Physiol 97: 797–805, 2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Elliott JE, Choi Y, Laurie SS, Yang X, Gladstone IM, Lovering AT. Effect of initial gas bubble composition on detection of inducible intrapulmonary arteriovenous shunt during exercise in normoxia, hypoxia or hyperoxia. J Appl Physiol 110: 35–54, 2010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Glazier JB, Hughes JM, Maloney JE, West JB. Measurements of capillary dimensions and blood volume in rapidly frozen lungs. J Appl Physiol 26: 65–76, 1969 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Hayek HV. The Human Lung. New York: Hafner, 1960, p. 372 [Google Scholar]

- 11. Hillier SC, Godbey PS, Hanger CC, Graham JA, Presson RG, Okada O, Linehan JH, Dawson CA, Wagner WW. Direct measurement of pulmonary microvascular distensibility. J Appl Physiol 75: 2106–2111, 1993 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Hopkins SR, Olfert IM, Wagner PD. Point:Counterpoint: Exercise-induced intrapulmonary shunting is imaginary vs. real. J Appl Physiol 107: 993–994, 2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Jiang ZL, Kassab GS, Fung YC. Diameter-defined Strahler system and connectivity matrix of the pulmonary arterial tree. J Appl Physiol 76: 882–892, 1994 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. La Gerche A, MacIsaac AI, Burns AT, Mooney DJ, Inder WJ, Voigt JU, Heidbüchel H, Prior DL. Pulmonary transit of agitated contrast is associated with enhanced pulmonary vascular reserve and right ventricular function during exercise. J Appl Physiol 109: 1307–1317, 2010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Laurie SS, Yang X, Elliott JE, Beasley KM, Lovering AT. Hypoxia-induced intrapulmonary arteriovenous shunting at rest in healthy humans. J Appl Physiol 109: 1072–1079, 2010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Linehan JH, Haworth ST, Nelin LD, Krenz GS, Dawson CA. A simple distensible vessel model for interpreting pulmonary vascular pressure-flow curves. J Appl Physiol 73: 987–994, 1992 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Lovering AT, Haverkamp HC, Romer LM, Hokanson JS, Eldridge MW. Transpulmonary passage of 99mTc macroaggregated albumin in healthy humans at rest and during maximal exercise. J Appl Physiol 106: 1986–1992, 2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Lovering AT, Romer LM, Haverkamp HC, Pegelow DF, Hokanson JS, Eldridge MW. Intrapulmonary shunting and pulmonary gas exchange during normoxic and hypoxic exercise in healthy humans. J Appl Physiol 104: 1418–1425, 2008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Lovering AT, Stickland MK, Amann M, Murphy JC, O'Brien MJ, Hokanson JS, Eldridge MW. Hyperoxia prevents exercise-induced intrapulmonary arteriovenous shunt in healthy humans. J Physiol 586: 4559–4565, 2008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Lovering AT, Stickland MK, Kelso AJ, Eldridge MW. Direct demonstration of 25- and 50-μm arteriovenous pathways in healthy human and baboon lungs. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 292: H1777–H1781, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Lynch JK, Han CJ. Pediatric stroke: What do we know and what do we need to know? Semin Neurol 25: 410–423, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Marshall JM, Metcalfe JD. Effects of systemic hypoxia on the distribution of cardiac output in the rat. J Physiol 426: 335–353, 1990 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Nomoto S, Berk JL, Hagen JF, Koo R. Pulmonary anatomic arteriovenous shunting caused by epinephrine. Arch Surg 108: 201–204, 1974 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Pacher P, Nagayama T, Mukhopadhyay P, Batkai S, Kass DA. Measurement of cardiac function using pressure-volume conductance catheter technique in mice and rats. Nat Protoc 3: 1422–1434, 2008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Rapp JH, Pan XM, Yu B, Swanson RA, Higashida RT, Simpson P, Saloner D. Cerebral ischemia and infarction from atheroemboli <100 μm in size. Stroke 34: 1976–1980, 2003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Reeves JT, Linehan JH, Stenmark KR. Distensibility of the normal human lung circulation during exercise. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol 288: L419–L425, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Richardson RS, Noyszewski EA, Kendrick KF, Leigh JS, Wagner PD. Myoglobin O2 desaturation during exercise. Evidence of limited O2 transport. J Clin Invest 96: 1916–1926, 1995 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Rosenzweig DY, Hughes JM, Glazier JB. Effects of transpulmonary and vascular pressures on pulmonary blood volume in isolated lung. J Appl Physiol 28: 553–560, 1970 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Schraufnagel DE, Pearse DB, Mitzner WA, Wagner EM. 3-Dimensional structure of the bronchial microcirculation in the sheep. Anat Rec 243: 357–366, 1995 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Stickland MK, Lovering AT, Eldridge MW. Exercise-induced arteriovenous intrapulmonary shunting in dogs. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 176: 300–305, 2007 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Stickland MK, Lovering AT, Eldridge MW. Exercise-induced arteriovenous intrapulmonary shunting in dogs. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 176: 300–305, 2007 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Stickland MK, Welsh RC, Haykowsky MJ, Petersen SR, Anderson WD, Taylor DA, Bouffard M, Jones RL. Effect of acute increases in pulmonary vascular pressures on exercise pulmonary gas exchange. J Appl Physiol 100: 1910–1917, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Wagner EM, Mitzner W, Brown RH. Site of functional bronchopulmonary anastomoses in sheep. Anat Rec 254: 360–366, 1999 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]