Abstract

First-generation nanoparticles (NPs) have been clinically translated as pharmaceutical drug delivery carriers for their ability to improve on drug tolerability, circulation half-life, and efficacy. Towards the development of the next-generation NPs, researchers have designed novel multifunctional platforms for sustained release, molecular targeting, and environmental responsiveness. This review focuses on environmentally-responsive mechanisms used in NP designs, and highlights the use of pH-responsive NPs in drug delivery. Different organs, tissues, and subcellular compartments – as well as their pathophysiological states – can be characterized by their pH levels and gradients. When exposed to these pH stimuli, pH-responsive NPs respond with physicochemical changes to their material structure and surface characteristics. These include swelling, dissociating or surface charge switching, in a manner that favors drug release at the target site over surrounding tissues. The novel developments described here may revise the classical outlook that NPs are passive delivery vehicles, in favor of responsive, sensing vehicles that use environmental cues to achieve maximal drug potency.

Keywords: nanoparticles, drug delivery, responsive, pH, acid

1. Introduction

In the past decade, a myriad of nanoparticle (NP)-based drug delivery systems have been used for clinical applications that range from oncologic to cardiovascular disease.1,2 These nanomedicines improve on existing therapeutic agents through their altered pharmacokinetics and biodistribution profiles. To further improve on NP therapeutic efficacy, researchers have begun to explore the use of environmentally-responsive NPs that can, when exposed to external stimuli, produce physicochemical changes that favor drug release at the target site.3 These external stimuli include (i) physical signals such as temperature, electric field, magnetic field, and ultrasound; and (ii) chemical signals such as pH, ionic strength, redox potential, and enzymatic activities. NP systems that include liposomes, polymeric micelles, lipoplexes, and polyplexes have been developed to use these physical and chemical cues to modify drug release properties.4,5

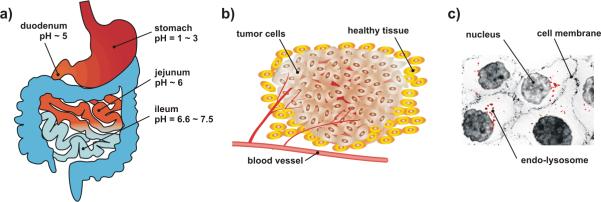

Among these environmental stimuli, pH gradients have been widely used to design novel, responsive NPs. This review assesses pH-responsive NP-based drug delivery at three levels, namely at the level of (i) organs, (ii) tissues, and (iii) within subcellular compartments (Figure 1). In particular, we will take specific examples from oral drug delivery, tumor targeting, and intracellular delivery to highlight conceptually interesting pH-responsive NP designs. At the organ level, NP-based oral delivery systems have been formulated for differential drug uptake along the gastrointestinal (GI) tract (Figure 1a).6,7 At the tissue level, NP formulations have been designed to exploit the pH gradients that exist in tumor microenvironments to achieve high local drug concentrations (Figure 1b).8,9 Finally, at the intracellular level, pH-responsive NPs have been designed to escape acidic endo-lysosomal compartments for cytoplasmic drug release (Figure 1c).10,11

Figure 1.

Design of acid-responsive NPs for selective drug release. (a) Targeting at the organ level: the GI tract is characterized by a pH gradient. (b) Targeting at the tissue level: solid tumors have a characteristic acidic extracellular environment different from healthy tissues. (c) Targeting at the cellular level: endo-lysosomes are more acidic in comparison to the cytoplasm (shown in red).

Hence, NP formulations that respond to pH gradients within the microenvironments of organs, tissues, and cell organelles may be useful additions to the spectrum of NP-based vehicles available for therapeutic drug delivery.

2. pH-responsive drug delivery at the organ level: oral drug delivery

Each segment of the gastrointestinal (GI) tract maintains its own characteristic pH level, from the acidic stomach lumen (pH 1–3) for digestion12, to the alkaline duodenum and ileum (pH 6.6–7.5) for the neutralization of chyme.13, 14 Oral delivery is an attractive drug delivery route for its convenience, patient compliance, and cost-effectiveness. However, orally-delivered drugs are exposed to strong gastric acid and presystemic enzymatic degradation, resulting in poor systemic exposure. Therefore, it has proven to be a challenge to achieve adequate and consistent bioavailability levels for orally-administered drugs.15,16 Until now, NPs formulated with biodegradable polymers have been used to improve bioavailability of easily-degraded peptide drugs such as insulin17,18, calcitonin19, and elcotonin20. More recently, newer nanomedicines have included pH-responsive mechanisms to improve systemic exposure from greater gastric retention, trans-epithelial transport, and cellular targeting with surface-functionalized ligands.21,22

One widely adopted approach to achieve organ-specific drug release is to formulate NPs that exhibit pH-dependent swelling. For example, when acrylic-based polymers such as poly(methacrylic acid) (PMAA) are used, NPs retain a hydrophobic, collapsed state in the stomach due to the protonation of carboxyl groups. After gastric passage, an increase in pH leads to NP swelling due to carboxyl ionization and hydrogen bond breakage.21 Based on these properties, PMAA–poly(ethylene glycol) (PEG) diblock co-polymers were able to achieve swelling ratios (mass of swollen polymer/mass of dry polymer) of 40–90 fold depending on copolymer composition and PEG graft length.23 When NPs were loaded with insulin, ~90% of the insulin was released at pH 7.4 within two hours in their swollen state, whereas only a small fraction (approximately 10%) of the insulin was released at pH 1.2 in their collapsed state.

In addition, PMAA copolymers that contain other components such as polyethylacrylate (PMAA–PEA) and polymethacrylate (PMAA–PMA) show pH-dependent dissolution that may be tailored to respond to the pH of different intestinal regions.24 For example, Eudragit® L100-55, a commercial formulation of PMAA–PEA, dissolves at pH > 5.5 and is therefore suitable for duodenal drug release. Similarly, Eudragit® S100, a commercial formulation of PMAA-PMA, dissolves at pH > 7.0 and is suitable for ileal drug release.25

Researchers have designed NPs that undergo a surface charge reversal after gastric passage, with the hope that drug release will occur in the alkaline intestinal tract instead. Using inorganic materials such as mesoporous silica, NPs were surface-functionalized with different densities of positively-charged trimethylammonium (TA) functional groups.26 The positively-charged TA facilitated loading and trapping of anionic drugs such as sulfasalazine (an anti-inflammatory prodrug for bowel disease) in acidic environments (pH <3). When the drug-loaded NPs were placed in physiological buffers (pH 7.4), a partial negative surface charge on the NPs was generated from the deprotonation of silanol groups; this electrostatic repulsion triggered the sustained release of loaded molecules.

pH-responsive NPs have been used to preferentially release drugs at sites of disease. Heparin-chitosan NPs were formulated and applied to treat Helicobacter pylori infections, given that the mucus layer and epithelium of the gastric lumen has a higher pH than the overall acidic environment of the stomach.27 130–300 nm NPs were formed by the mixing of heparin and chitosan at pH 1.2–2.5; the NPs maintained their stability in the gastric lumen attributable to electrostatic interactions within the structures. Upon contact with an H. pylori infection along the gastric epithelium (pH ~7.4), the deprotonation of chitosan occurs, which weakens electrostatic interactions and leads to NP collapse and heparin release. In another study, chitosan, together with poly-γ-glutamic acid, tripolyphosphate, and MgSO4, was used to formulate `multi-ion-crosslinked' NPs. The NPs were used to encapsulate insulin at < pH 6 and release it at higher pH by chitosan deprotonization and NP destabilization.28

NPs have been surface-modified with selective targeting ligands for differential retention along the GI tract. The ligands used in these studies are acid-stable and include lectin29, small peptides30,31 and vitamins.32,33 For example, chitosan, which has been shown to facilitate particle transcytosis across the intestinal epithelium, was used to formulate PMAA–chitosan–PEG NPs.34 Vitamin B-12, which enhanced NP apical-to-basal transport in Caco-2 cells35 was surface-functionalized onto dextran NPs for insulin delivery in vivo.33 In addition, RGD peptides were used to target to β1 integrins expressed on the apical side of M cells in vitro36 and in vivo.31 Novel peptides were selected using in vivo phage display to identify peptides for targeted NP delivery to the M cells and follicle-associated epithelium (FAE) of the intestines.30

Hence, the NPs described here show pH-dependent drug release properties, enhanced membrane permeability, and have been modified with selective targeting ligands. These NPs are promising delivery vehicles for differential retention and uptake along the GI tract, and ultimately, they may improve on the efficacy of orally-delivered nanomedicines.

3. pH-responsive mechanisms at the tissue level: tumor targeting

Human tumors have been shown to exhibit acidic pH states that range from 5.7–7.8 (Figure 1b).37 The acidity of tumor microenvironments is caused in-part by lactic acid accumulation in rapidly growing tumor cells owing to their elevated rates of glucose uptake but reduced rates of oxidative phosphorylation.38 This persistence of high lactate production by tumors in the presence of oxygen, termed Warburg's effect, provides growth advantage for tumor cells in vivo.39 In addition, insufficient blood supply and poor lymphatic drainage which are characteristics of most tumors also contribute to the acidity of tumor microenvironment.40 Increasingly, researchers have exploited the acidic tumor pH to achieve high local drug concentrations and to minimize overall systemic exposure.9,41 NPs have been formulated for pH-dependent drug release by using polymers that change their physical and chemical properties, such as by swelling and solubility, based on local pH levels. Particularly, NPs take these actions by responding to the acidic pH of tumor microenvironments, as apposed to those in oral drug delivery where the elevated pH is often used as trigger.

To achieve NP swelling, Griset et al. cross-linked NPs using acrylate-based hydrophobic polymers with hydroxyl groups that were masked by pH-labile protecting groups (e.g. 2,4,6-trimethoxybenzaldehyde).42 The NPs were stable at neutral pH, but the protecting group was cleaved and the hydroxyl groups were exposed at mildly acidic pH (~pH 5). This hydrophobic-to-hydrophilic transformation caused the swelling of NPs and subsequent drug release. Paclitaxel release was shown to be minimal at pH 7.4 (< 10%), whereas nearly all of the drugs were released within 24 h at pH 5. These acrylate-based, pH-sensitive NPs were shown to prevent the rapid growth of LLC tumors in C57Bl/6 mice compared to non-responsive NPs or paclitaxel in solution, suggesting that pH-responsive drug release may be beneficial for drug delivery to tumors.

pH-dependent hydrophobic-to-hydrophilic transitions may also be used to control polymer dissolution, in which the polymer matrix collapses for drug release. Wu et al. formulated NPs using PEG-poly(β-amino ester) polymers that have a pKb of ~6.5.43 At pH 6.4–6.8, amine protonation increased polymer solubility and induced a sharp micellization-demicellization transition for drug release. In another study, Criscione et al. showed that self-assembly of poly(amidoamine) dendrimers occurred at physiological pH, followed by drug release from NP dissolution at pH < 6.44

Drug molecules have been conjugated to polymer chains via pH-labile cross-linkers for pH-responsive drug release. Recently, Aryal et al. developed cisplatin–polymer conjugated NPs using hydrazone cross-linkers to achieve low pH drug release.45 Cisplatin release occurred at pH < 6 due to hydrazone hydrolysis as opposed to poly(lactic acid) (PLA) degradation; this later contributed to enhanced cellular cytotoxicity over free cisplatin in vitro. In another study, chromone conjugated to magnetic Fe3O4 NPs via a Schiff-base bond led to a four-fold improvement in chromone release at pH 5 versus at pH 7.4, an improvement in chromone solubility in buffer solutions from 2.5 to 633 μg/mL, and finally, enhanced cytotoxicity in vitro.46 For dual-drug delivery, Shen et al. formed liposome-like NPs by conjugating camptothecin to short PEG chains via an ester bond, followed by encapsulating doxorubicin, a hydrophilic drug.47 When loaded with doxorubicin salts (doxorubicin·HCl), rapid release of both doxorubicin and camptothecin occurred at pH < 5 or when an esterase was added. Likewise, Bruyère et al. synthesized a series of orthoester model compounds which had different hydrolysis rates at pH ranging from pH 4.5–7.4.48 A summary of acid labile linkers used in conjugation chemistry and their hydrolytic products are listed in Table 1.

Table 1.

Common pH-labile crosslinkers and their hydrolytic products.

To increase NP retention in tumors, NPs have been designed to reverse their surface charge from neutral/negative to positive at the tumor site. In one study, quantum dots and adenovirus-based NPs were surface-functionalized with pH-sensitive poly(L-lysine) (PLL).49 PLL amine groups were conjugated with biotin–PEG and citraconic anhydride (a pH-sensitive primary amine blocker) to generate carboxylate groups. Under acidic conditions (pH < 6.6), the citraconylated amide linkages were cleaved, resulting in the recovery of positively charged amine groups. This surface charge reversal in turn led to enhanced NP uptake and transfection of HeLa cells.

The pH-responsive mechanisms described here draw upon a general phenomenon which is the acidity of tumor microenvironments. Here, NPs maintain stability in circulation and undergo physicochemical changes that favor localized drug release.

4. pH-responsive NPs at the cellular level: intracellular delivery

Following endocytosis, rapid endosomal acidification (~2–3 min) occurs due to a vacuolar proton ATPase-mediated proton influx. As a result, the pH levels of early endosomes, sorting endosomes, and multivesicular bodies drop rapidly to < pH 6.0.63 The process of endosomal acidification can be harmful to the therapeutic molecule being delivered, especially for macromolecules such as DNA, small interfering RNA (siRNA), and proteins. However, endosomal acidification may also be used as a trigger for endosomal escape and payload release, a mechanism hypothesized to occur via a `proton sponge' effect.64 Here, NPs absorb protons at endosomal pH, leading to an increase in osmotic pressure inside the endosomal compartment, followed by plasma membrane disruption and NP release into the cytoplasm.

pH-sensitive polymers that buffer endosomal compartments have been grafted with other functional segments for intracellular delivery. For example, a NP platform termed Dynamic PolyConjugates (Mirus Bio LLC) has an amphipathic endosomolytic poly(vinyl ether) backbone composed of butyl and amino vinyl ethers. The NPs were used to conjugate and deliver siRNA through a reversible disulfide linkage, and included functional components such as PEG and targeting ligands. The Dynamic Polyconjugates provided effective knockdown of two endogenous liver genes, apolipoprotein B and peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor alpha (PPARα) in vivo. 53,65

Amine-containing monomers have been used in rational syntheses of polymers that buffer pH in endosomes. For example, an amphiphilic and cationic triblock copolymer consisting of monomethoxy PEG, poly(3-caprolactone) and poly(2-aminoethyl ethylene phosphate) (mPEG45–b–PCL100–b–PPEEA12) was designed for endosomal buffering and siRNA delivery.66 The NPs were found to effectively silence GFP expression in HEK293 cells without significant cytotoxicity. In another study, Tietze et al. developed β-propionamide-cross-linked oligoethylenimine polymers for siRNA delivery. The siRNA-encapsulated NPs knocked down nuclear Ran expression without corresponding cytotoxicity.67 Jeong et al. developed reducible poly(amido ethylenimine) (PEI) polymers by addition copolymerization of triethylenetetramine and cystamine bisacrylamide. The reducible PEI NPs were used to deliver siRNA that suppressed VEGF expression in PC3 human prostate cancer cell lines with lower cytotoxicity compared to linear PEI formulations.68

Copolymers made from pH-sensitive monomers and nonionic monomers allow fine-tuning of polymer pKa for improved endosomal escape. For example, using copolymers made from monomers with different pKa (e.g. dimethylaminoethyl methacrylate and nonionic monomer 2-hydroxyethyl methacrylate), it was possible to adjust NP pH sensitivity, DNA encapsulation efficiency, and monomer toxicity to optimize transfection efficiency.69

Biodegradable poly(β-amino ester) (PbAE) polymers contains tertiary amines that have been used for pH buffering. A combinatorial family of PbAE compounds were created by parallel-synthesis using amine- and acrylate-terminated monomers in a Michael addition reaction, without the use of specialized monomers or protection steps.70 In this study, PbAE NPs were shown to undergo rapid dissolution in acidic microenvironments (pH 6.5) which facilitated drug release. NPs based on PbAE have been applied to deliver small molecule drugs,71 DNA,72 and siRNA.73,74

Stealth PEG layers that are stable in circulation but are released in endosomes have been used to facilitate NP endosomal escape. While PEG shedding itself does not cause endosomal disruption, it may aid NP escape by reducing steric and electrostatic hindrance from the PEG layer. Several PEG-sheddable NP formulations have been developed where PEG is grafted onto NPs via pH labile cross-linkers.75 In these studies, PEG shedding was shown to both favor drug release76 and gene expression77, suggesting a general application for PEG-shedding strategies.

Finally, NP designs may contain protein transduction domains (PTDs), which are cationic, 10–30 amino acid sequences hypothesized to disrupt endosomal membranes upon endosomal acidification.78 The mechanism of PTD membrane penetration is an active research topic and PTDs have been widely used to improve intracellular delivery in oncologic-based applications.79–81 In one study, the co-administration of a free tumor-penetrating peptide (e.g. iRGD sequence) was shown to enhance the efficacy of doxorubicin (doxorubicin liposomes), paclitaxel (nab-paclitaxel), and monoclonal antibody (trastuzumab) treatments.82

However, caution must be taken when targeting is used to improve intracellular delivery, because the extent of endosomal acidification is influenced by the choice of targeting ligand used and hence the endocytic pathway taken. For example, surface-modification with folate was shown to lead to endocytosis through recycling centers characterized by near neutral pH of pH 6–7, which may make it less suitable for pH-based mechanisms.83

Hence, pH-sensitive mechanisms are also important at the stages after NPs are internalized, particularly for the release of a payload into the cytoplasm of the target cell. These mechanisms are even more crucial for payloads such as siRNA, DNA, and proteins, where denaturation in the acidic lysosomal compartment may result in a significant drop in efficacy.

5. Concluding Remarks

Novel approaches in pH-responsive NP design and engineering have resulted in improved drug delivery in pre-clinical studies. In this paper, we have reviewed recent progress made in the research and development of pH-responsive NPs for drug delivery at three levels: at the organ, tissue and subcellular levels. The mechanisms employed in these studies are briefly summarized below in Table 2. With sustained effort in tailoring NPs for environmentally-sensitive drug delivery, it is expected that environmentally-responsive approaches will result in next-generation nanomedicines that have extensive medical applications.

Table 2.

Summary of pH-responsive mechanisms used in nanoparticle designs.

| Mechanisms | References |

|---|---|

| At the organ level: oral drug delivery | |

| pH-dependent swelling and dissolve (at higher pH) | 21, 23–25, |

| pH-dependent drug release 'cap' (in porous silica nanoparticles) | 26 |

| pH-dependent drug dissociation and release | 27, 28 |

| At the tissue level: tumor targeting | |

| pH-dependent swelling and dissolve (at lower pH) | 42 – 44 |

| pH-sensitive drug-polymer conjugations | 45 – 48 |

| pH-dependent charge reversal to increase tumor retention | 49 |

| At the cellular level: intracellular delivery | |

| pH-sensitive polymer for endosomal buffering | 53, 65–74 |

| pH-labile linker to shed the stealth coating | 75-77 |

| pH-dependent cell penetration peptide | 78 – 82 |

Acknowledgments

Authors' research was supported by National Institutes of Health Grants CA119349 and EB003647 and Koch–Prostate Cancer Foundation Award in Nanotherapeutics.

Footnotes

Conflict of Interest Dr. Omid C. Farokhzad has financial interest in BIND Biosciences and Selecta Biosciences, biopharmaceutical companies developing therapeutic targeted nanoparticles.

References

- 1.Zhang L, Gu FX, Chan J, Wang AZ, Langer R, Farokhzad OC. Nanoparticles in Medicine: Therapeutic Applications and Developments. Clin. Pharmacol. Ther. 2008;83:761–769. doi: 10.1038/sj.clpt.6100400. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Farokhzad OC, Langer R. Impact of Nanotechnology on Drug Delivery. ACS Nano. 2009;3:16–20. doi: 10.1021/nn900002m. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Stuart MAC, Huck WTS, Genzer J, Müller M, Ober C, Stamm M, Sukhorukov GB, Szleifer I, tsukruk VV, Urban M, Winnik F, Zauscher S, Luzinov I, Minko S. Emerging Applications of Stimuli-Responsive Polymer Materials. Nat. Mater. 2010;9:101–113. doi: 10.1038/nmat2614. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Muthu MS, Rajesh CV, Mishra A, Singh S. Stimulus-Responsive Targeted Nanomicelles for Effective Cancer Therapy. Nanomedicine. 2009;4:657–667. doi: 10.2217/nnm.09.44. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Li YY, Dong HQ, Wang K, Shi DL, Zhang XZ, Zhuo RX. Stimulus-Responsive Polymeric Nanoparticles for Biomedical Applications. Science China Chemistry. 2010;53:447–457. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Rajput G, Majmudar F, Patel J, Thakor R, Rajgor NB. Stomach-Specific Mucoadhesive Microsphere as a Controlled Drug Delivery System. Sys. Rev. Pham. 2010;1:70–78. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Davis SS, Wilding EA, Wilding IR. Gastrointestinal Transit of a Matrix Tablet Formulation: Comparison of Canine and Human Data. Int. J. Pharm. 1993;94:235–238. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Asokan A, Cho MJ. Exploitation of Intracellular Ph Gradient in the Cellular Delivery of Macromolecules. J. Pharm. Sci. 2002;91:903–913. doi: 10.1002/jps.10095. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Gerweck LE, Vijayappa S, Kozin S. Tumor Ph Controls the in Vivo Efficacy of Weak Acid and Base Chemotherapeutics. Mol. Cancer. Ther. 2006;5:1275–1279. doi: 10.1158/1535-7163.MCT-06-0024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Whitehead KA, Langer R, Anderson DG. Knocking Down Barriers: Advances in Sirna Delivery. Nat. Rev. Drug Discov. 2009;8:129–138. doi: 10.1038/nrd2742. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Dominska M, Dykxhoorn DM. Breaking Down the Barriers: Sirna Delivery and Endosome Escape. J. Cell. Sci. 2010;123:1183–1189. doi: 10.1242/jcs.066399. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Dressman JB, Berardi RR, Dermentzoglou LC, Russell TL, Schmaltz SP, Barnett JL, Jarvenpaa KM. Upper Gastrointestinal (Gi) Ph in Young, Healthy Men and Women. Pharm. Res. 1990;7:756–761. doi: 10.1023/a:1015827908309. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Read NW, Sugden K. Gastrointestinal Dynamics and Pharmacology for the Optimum Design of Controlled-Release Oral Dosage Forms. CRC Critical Reviews in Therapeutic Drug Carrier Systems. 1998;4:221–263. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kararli TT. Comparison of the Gastrointestinal Anatomy, Physiology, and Biochemistry of Humans and Commonly Used Laboratory Animals. Biopharm. Drug Dispos. 1995;16:351–380. doi: 10.1002/bdd.2510160502. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Morishita M, Peppas NA. Is the Oral Route Possible for Peptide and Protein Drug Delivery? Drug Discov. Today. 2006;11:905–910. doi: 10.1016/j.drudis.2006.08.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Yamanaka YJ, Leong KW. Engineering Strategies to Enhance Nanoparticle-Mediated Oral Delivery. J. Biomater. Sci. Polymer Edn. 2008;19:1549–1570. doi: 10.1163/156856208786440479. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Delie F, Blanco-Príeto MJ. Polymeric Particulates to Improve Oral Bioavailability of Peptide Drugs. Molecules. 2005;10:65–80. doi: 10.3390/10010065. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Sarmento B, Ribeiro A, Veiga F, Ferreira D, Neufeld R. Oral Bioavailability of Insulin Contained in Polysaccharide Nanoparticles. Biomacromolecules. 2007;8:3054–3060. doi: 10.1021/bm0703923. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lamprecht A, Yamamoto H, Takeuchi H, Kawashima Y. Ph-Sensitive Microsphere Delivery Increases Oral Bioavailability of Calcitonin. J. Control. Release. 2004;98:1–9. doi: 10.1016/j.jconrel.2004.02.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kawashima Y, Yamamoto H, Takeuchi H, Kuno Y. Mucoadhesive Dl-Lactide/Glycolide Copolymer Nanospheres Coated with Chitosan to Improve Oral Delivery of Elcatonin. Pharm. Dev. Technol. 2000;5:77–85. doi: 10.1081/pdt-100100522. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Colombo P, Sonvico F, Colombo G, Bettini R. Novel Platforms for Oral Drug Delivery. Pharm. Res. 2009;26:601–611. doi: 10.1007/s11095-008-9803-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Roger E, Lagarce F, Garcion E, Benoit J. Biopharmaceutical Parameters to Consider in Order to Alter the Fate of Nanocarriers after Oral Delivery. Nanomedicine. 2010;5:287–306. doi: 10.2217/nnm.09.110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Peppas NA. Devices Based on Intelligent Biopolymers for Oral Protein Delivery. Int. J. Pharm. 2004;277:11–17. doi: 10.1016/j.ijpharm.2003.03.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Dai S, Tam KC, Jenkins RD. Aggregation Behavior of Methacrylic Acid/Ethyl Acrylate Copolymer in Dilute Solutions. Eur. Polym. J. 2000;36:2671–2677. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Dai J, Nagai T, Wang X, Zhang T, Meng M, Zhang Q. Ph-Sensitive Nanoparticles for Improving the Oral Bioavailability of Cyclosporine A. Int. J. Pharm. 2004;280:229–240. doi: 10.1016/j.ijpharm.2004.05.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Lee C, Lo L, Mou C, Yang C. Synthesis and Characterization of Positive-Charge Functionalized Mesoporous Silica Nanoparticles for Oral Drug Delivery of an Anti-Inflammatory Drug. Adv. Funt. Mater. 2008;18:3283–3292. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Lin Y, Chang C, Wu Y, Hsu Y, Chiou S, Chen Y. Development of Ph-Responsive Chitosan/Heparin Nanoparticles for Stomach-Specific Anti-Helicobacter Pylori Therapy. Biomaterials. 2009;30:3332–3342. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2009.02.036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Lin Y, Sonaje K, Lin KM, Juang J, Mi F, Yang H, Sung H. Multi-Ion-Crosslinked Nanoparticles with Ph-Responsive Characteristics for Oral Delivery of Protein Drugs. J. Control. Release. 2008;132:141–149. doi: 10.1016/j.jconrel.2008.08.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Akande J, Yeboah KG, Addo RT, Siddig A, Oettinger CW, D'Souza MJ. Targeted Delivery of Antigens to the Gut-Associated Lymphoid Tissues: 2. Ex Vivo Evaluation of Lectin-Labelled Albumin Microspheres for Targeted Delivery of Antigens to the M-Cells of the Peyer's Patches. J. Microencapsul. 2010;27:325–336. doi: 10.3109/02652040903191834. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Higgins LM, Lambkin I, Donnelly G, Byrne D, Wilson C, Dee J, Smith M, O'Mahony DJ. In Vivo Phage Display to Identify M Cell–Targeting Ligands. Pharm. Res. 2004;21:695–705. doi: 10.1023/b:pham.0000022418.80506.9a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Garinot M, Fiévez V, Pourcelle V, Stoffelbach F, Rieux A, Plapied L, Theate I, Freichels H, Jérôme C, Marchand-Brynaert J, Schneider Y, Préat V. Pegylated Plga-Based Nanoparticles Targeting M Cells for Oral Vaccination. J. Control. Release. 2007;120:195–204. doi: 10.1016/j.jconrel.2007.04.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Zhang Z, Feng S. Self-Assembled Nanoparticles of Poly(Lactide)–Vitamin E Tpgs Copolymers for Oral Chemotherapy. Int. J. Pharm. 2006;324:191–198. doi: 10.1016/j.ijpharm.2006.06.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Chalasani KB, Russell-Jones GJ, Jain AK, Diwan PV, Jain SK. Effective Oral Delivery of Insulin in Animal Models Using Vitamin B12-Coated Dextran Nanoparticles. J. Control. Release. 2007;122:141–150. doi: 10.1016/j.jconrel.2007.05.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Sajeesh S, Sharma CP. Novel Ph Responsive Polymethacrylic Acid-Chitosan-Polyethylene Glycol Nanoparticles for Oral Peptide Delivery. J. Biomed. Mater. Res. B. 2006;76B:298–305. doi: 10.1002/jbm.b.30372. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Russell-Jones GJ, Arthur L, Walker H. Vitamin B-12-Mediated Transport of Nanoparticles across Caco-2 Cells. Int. J. Pharm. 1999;179:247–255. doi: 10.1016/s0378-5173(98)00394-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Gullberg E, Keita ÅV, Salim SY, Andersson M, Caldwell KD, Soderholm JD, Artursson P. Identification of Cell Adhesion Molecules in the Human Follicle-Associated Epithelium That Improve Nanoparticle Uptake into the Peyer's Patches. J. Pharmcol. Exp. Ther. 2006;319:632–639. doi: 10.1124/jpet.106.107847. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Vaupel P. Tumor Microenvironmental Physiology and Its Implications for Radiation Oncology. Semi. Radiat. Oncol. 2004;14:198–206. doi: 10.1016/j.semradonc.2004.04.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Kim J, Dang CV. Cancer's Molecular Sweet Tooth and the Warburg Effct. Cancer Res. 2006;66:8927–8930. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-06-1501. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Christofk HR, Heiden MGV, Harris MH, Ramanathan A, Gerszten RE, Wei R, Fleming MD, Schreiber SL, Cantley LC. Them2splice Isoform of Pyruvate Kinase Is Important for Cancer Metabolism and Tumour Growth. Nature. 2008;452:230–234. doi: 10.1038/nature06734. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Brahimi-Horn M, Pouyssegur J. Oxygen, a Source of Life and Stress. FEBS Letters. 2007;581:3582–3591. doi: 10.1016/j.febslet.2007.06.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Lee E, Gao Z, B Y. Recent Progress in Tumor Ph Targeting Nanotechnology. J. Control. Release. 2008;132:164–170. doi: 10.1016/j.jconrel.2008.05.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Griset AP, Walpole J, Liu R, Gaffey A, Colson YL, Grinstaff MW. Expansile Nanoparticles: Synthesis, Characterization, and in Vivo Efficacy of an Acid-Responsive Polymeric Drug Delivery System. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2009;131:2469–2471. doi: 10.1021/ja807416t. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Wu XL, Kim JH, Koo H, Bae SM, Shin H, Kim MS, Lee B, Park R, Kim I, Choi K, Kwon IC, Kim K, Lee DS. Tumor-Targeting Peptide Conjugated Ph-Responsive Micelles as a Potential Drug Carrier for Cancer Therapy. Bioconjugate. Chem. 2010;21:208–213. doi: 10.1021/bc9005283. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Criscione JM, Le BL, Stern E, Brennan M, Rahner C, Papademetris X, Fahmy TM. Self-Assembly of Ph-Responsive Fluorinated Dendrimer-Based Particulates for Drug Delivery and Noninvasive Imaging. Biomaterials. 2009;30:3946–3955. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2009.04.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Aryal S, Hu CJ, Zhang L. Polymer-Cisplatin Conjugate Nanoparticles for Acid-Responsive Drug Delivery. ACS Nano. 2010;4:251–258. doi: 10.1021/nn9014032. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Wang B, Xu C, Xie J, Yang Z, Sun S. Ph Controlled Release of Chromone from Chromone-Fe3o4 Nanoparticles. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2008;130:14436–14437. doi: 10.1021/ja806519m. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Shen Y, Jin E, Zhang B, Murphy CJ, Sui M, Zhao J, Wang J, Tang J, Fan M, Kirk EV, Murdoch WJ. Prodrugs Forming High Drug Loading Multifunctional Nanocapsules for Intracellular Cancer Drug Delivery. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2010;132:4259–4265. doi: 10.1021/ja909475m. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Bruyère H, Westwell AD, Jones AT. Tuning the Ph Sensitivities of Orthoester Based Compounds for Drug Delivery Applications by Simple Chemical Modification. Bioorgan. Med. Chem. 2010;20:2200–2203. doi: 10.1016/j.bmcl.2010.02.035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Mok H, Park JW, Park TG. Enhanced Intracellular Delivery of Quantum Dot and Adenovirus Nanoparticles Triggered by Acidic Ph Via Surface Charge Reversal. Bioconjugate. Chem. 2008;19:797–801. doi: 10.1021/bc700464m. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Sengupta S, Eavarone D, Capila I, Zhao G, Watson N, Kiziltepe T, Sasisekharan R. Temporal Targeting of Tumour Cells and Neovasculature with a Nanoscale Delivery System. Nature. 2005;436:568–572. doi: 10.1038/nature03794. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Tong R, Cheng J. Ring-Opening Polymerization-Mediated Controlled Formulation of Polylactide-Drug Nanoparticles. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2009;131:4744–4754. doi: 10.1021/ja8084675. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Banerjee SS, Chen D. Multifunctional Ph-Sensitive Magnetic Nanoparticles for Simultaneous Imaging, Sensing and Targeted Intracellular Anticancer Drug Delivery. Nanotechnology. 2008;19:505104–8. doi: 10.1088/0957-4484/19/50/505104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Rozema DB, Lewis DL, Wakefield DH, Wong SC, Klein JJ, Roesch PL, Bertin SL, Reppen TW, Chu Q, Blokhin AV, Hagstrom JE, Wolff JA. Dynamic Polyconjugates for Targeted in Vivo Delivery of Sirna to Hepatocytes. P. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2007;104:12982–12987. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0703778104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Liu R, Zhang Y, Zhao X, Agarwal A, Mueller LJ, Feng P. Ph-Responsive Nanogated Ensemble Based on Gold-Capped Mesoporous Silica through an Acid-Labile Acetal Linker. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2010;132:1500–1501. doi: 10.1021/ja907838s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Huang X, Du F, Cheng J, Dong Y, Liang D, Ji S, Lin S, Li Z. Acid-Sensitive Polymeric Micelles Based on Thermoresponsive Block Copolymers with Pendent Cyclic Orthoester Groups. Macromolecules. 2009;42:783–790. [Google Scholar]

- 56.Gu J, Cheng W, Liu J, Lo S, Smith D, Qu X, Yang Z. Ph-Triggered Reversible 'Stealth' Polycationic Micelles. Biomacromolecules. 2008;9:255–262. doi: 10.1021/bm701084w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Ali MM, Oishi M, Nagatsugi F, Mori K, Nagasaki Y, Kataoka K, Sasaki S. Intracellular Inducible Alkylation System That Exhibits Antisense Effects with Greater Potency and Selectivity Than the Natural Oligonucleotide. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2006;45:3136–3140. doi: 10.1002/anie.200504441. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Oishi M, Nagatsugi F, Sasaki S, Nagasaki Y, Kataoka K. Smart Polyion Complex Micelles for Targeted Intracellular Delivery of Pegylated Antisense Oligonucleotides Containing Acid-Labile Linkages. CHEMBIOCHEM. 2005;6:718–725. doi: 10.1002/cbic.200400334. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Li Y, Lee PI. A New Bioerodible System for Sustained Local Drug Delivery Based on Hydrolytically Activated in Situ Macromolecular Association. Int. J. Pharm. 2010;383:45–52. doi: 10.1016/j.ijpharm.2009.09.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Xu Z, Gu W, Chen L, Gao Y, Zhang Z, Li Y. A Smart Nanoassembly Consisting of Acid-Labile Vinyl Ether Peg-Dope and Protamine for Gene Delivery: Preparation and in Vitro Transfection. Biomacromolecules. 2008;9:3119–3126. doi: 10.1021/bm800706f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Jeong JH, Kim SW, Park TG. Novel Intracellular Delivery System of Antisense Oligonucleotide by Self-Assembled Hybrid Micelles Composed of DNA/Peg Conjugate and Cationic Fusogenic Peptide. Bioconjugate. Chem. 2003;14:473–479. doi: 10.1021/bc025632k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Yang L, Chen L, Zeng R, Li C, Qiao R, Hu L, Li Z. Synthesis, Nanosizing and in Vitro Drug Release of a Novel Anti-Hiv Polymeric Prodrug: Chitosan-OIsopropyl-5'-O-D4t Monophosphate Conjugate. Bioorgan. Med. Chem. 2010;18:117–123. doi: 10.1016/j.bmc.2009.11.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Murphy RF, Powers S, Cantor CR. Endosome Ph Measured in Single Cells by Dual Fluorescence Flow Cytometry: Rapid Acidification of Insulin to Ph 6. J. Cell. Biol. 1984;98:1757–1762. doi: 10.1083/jcb.98.5.1757. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Behr JP. The Proton Sponge: A Trick to Enter Cells the Viruses Did Not Exploit. CHIMIA. 1997;51:34–36. [Google Scholar]

- 65.Wakefield DH, Klein JJ, Wolff JA, Rozema DB. Membrane Activity and Transfection Ability of Amphipathic Polycations as a Function of Alkyl Group Size. Bioconjugate. Chem. 2005;16:1204–1208. doi: 10.1021/bc050067h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Sun T, Du J, Yan L, Mao H, Wang J. Self-Assembled Biodegradable Micellar Nanoparticles of Amphiphilic and Cationic Block Copolymer for Sirna Delivery. Biomaterials. 2008;29:4348–4355. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2008.07.036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Tietze N, Pelisek J, Philipp A, Roedl W, Merdan T, Tarcha P, Ogris M, Wagner E. Induction of Apoptosis in Murine Neuroblastoma by Systemic Delivery of Transferrin-Shielded Sirna Polyplexes for Downregulation of Ran. Oligonucleotides. 2008;18:161–174. doi: 10.1089/oli.2008.0112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Jeong JH, Christensen LV, Yockman JW, Zhong Z, Engbersen JFJ, Kim WJ, Feijen J, Kim SW. Reducible Poly(Amido Ethylenimine) Directed to Enhance Rna Interference. Biomaterials. 2007;28:1912–1917. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2006.12.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.You J, Auguste DT. Nanocarrier Cross-Linking Density and Ph Sensitivity Regulate Intracellular Gene Transfer. Nano Letters. 2009;9:4467–4473. doi: 10.1021/nl902789s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Little SR, Kohane DS. Polymers for Intracellular Delivery of Nucleic Acids. J. Mater. Chem. 2008;18:832–841. [Google Scholar]

- 71.Ko J, Park K, Kim Y, Kim MS, Han JK, Kim K, Park R, Kim I, Song HK, Lee DS, Kwon IC. Tumoral Acidic Extracellular Ph Targeting of Ph-Responsive Mpeg-Poly (B-Amino Ester) Block Copolymer Micelles for Cancer Therapy. J. Control. Release. 2007;123:109–115. doi: 10.1016/j.jconrel.2007.07.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Little SR, Lynn DM, Ge Q, Anderson DG, Puram SV, Chen J, Eisen HN, Langer R. Poly-B Amino Ester-Containing Microparticles Enhance the Activity of Nonviral Genetic Vaccines. P. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2004;101:9534–9539. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0403549101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Tseng S, Tang S. Development of Poly(Amino Ester Glycol Urethane)/Sirna Polyplexes for Gene Silencing. Bioconjugate. Chem. 2007;18:1383–1390. doi: 10.1021/bc060382j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Jere D, Xu C, Arote R, Yun C, Cho M, Cho C. Poly(B-Amino Ester) as a Carrier for Si/Shrna Delivery in Lung Cancer Cells. Biomaterials. 2008;29:2535–2547. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2008.02.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Romberg B, Hennink WE, Storm G. Sheddable Coatings for Long-Circulating Nanoparticles. Pharm. Res. 2008;25:55–71. doi: 10.1007/s11095-007-9348-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Cerritelli S, Velluto D, Hubbell JA. Peg-Ss-Pps: Reduction-Sensitive Disulfide Block Copolymer Vesicles for Intracellular Drug Delivery. Biomacromolecules. 2007;8:1966–1972. doi: 10.1021/bm070085x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Takae S, Miyata K, Oba M, Ishii T, Nishiyama N, Itaka K, Yamasaki Y, Koyama H, Kataoka K. Peg-Detachable Polyplex Micelles Based on Disulfide-Linked Block Catiomers as Bioresponsive Nonviral Gene Vectors. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2008;130:6001–6009. doi: 10.1021/ja800336v. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Lundberg M, Wikstrom S, Johansson M. Cell Surface Adherence and Endocytosis of Protein Transduction Domains. Molecular Therapy. 2003;8:143–150. doi: 10.1016/s1525-0016(03)00135-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Lindgren M, Hällbrink M, Prochiantz A, Langel Ü. Cell-Penetrating Peptides. TiPS. 2000;21:99–103. doi: 10.1016/s0165-6147(00)01447-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Gupta B, Levchenko TS, Torchilin VP. Intracellular Delivery of Large Molecules and Small Particles by Cell-Penetrating Proteins and Peptides. Adv. Drug. Deliver. Rev. 2005;57:637–651. doi: 10.1016/j.addr.2004.10.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Meade BR, Dowdy SF. Enhancing the Cellular Uptake of Sirna Duplexes Following Noncovalent Packaging with Protein Transduction Domain Peptides. Adv. Drug. Deliver. Rev. 2008;60:530–536. doi: 10.1016/j.addr.2007.10.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Sugahara KN, Teesalu T, Karmali PP, Kotamraju VR, Agemy L, Greenwald DR, Ruoslahti E. Coadministration of a Tumor-Penetrating Peptide Enhances the Efficacy of Cancer Drugs. Science. 2010;328:1031–1035. doi: 10.1126/science.1183057. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Yang J, Chen H, Vlahov IR, Cheng J, Low PS. Characterization of the Ph of Folate Receptor-Containing Endosomes and the Rate of Hydrolysis of Internalized Acid-Labile Folate-Drug Conjugates. J. Pharmcol. Exp. Ther. 2007;321:462–468. doi: 10.1124/jpet.106.117648. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]