Abstract

OBJECTIVE

We examined the prevalence of knowledge of A1C, blood pressure, and LDL cholesterol (ABC) levels and goals among people with diabetes, its variation by patient characteristics, and whether knowledge was associated with achieving levels of ABC control recommended for the general diabetic population.

RESEARCH DESIGN AND METHODS

Data came from 1,233 adults who self-reported diabetes in the 2005–2008 National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey. Participants reported their last ABC level and goals specified by their physician (not validated by medical record data). Analysis included descriptive statistics and logistic regression.

RESULTS

Among participants tested in the past year, 48% stated their last A1C level. Overall, 63% stated their last blood pressure level and 22% stated their last LDL cholesterol level. Knowledge of ABC levels was greatest in non-Hispanic whites, lowest in Mexican Americans, and higher with more education and income (all P ≤ 0.02). Demographic associations were similar for those reporting physician-specified ABC goals at the American Diabetes Association–recommended levels (A1C <7%, blood pressure <130/80 mmHg, and LDL cholesterol <100 mg/dL). Nineteen percent of participants stated that their provider did not specify an A1C goal compared with 47% and 41% for blood pressure and LDL cholesterol goals, respectively. For people who self-reported A1C <7.0%, 83% had an actual A1C <7.0%. Otherwise, participant knowledge was not significantly associated with risk factor control, except for in those who knew their last LDL cholesterol level (P = 0.046 for A1C <7.0%). Results from logistic regression corroborated these findings.

CONCLUSIONS

Ample opportunity exists to improve ABC knowledge. Diabetes education should include behavior change components in addition to information on ABC clinical measures.

The prevalence of diabetes has increased over the past several decades, with 11% of U.S. adults currently having either diagnosed or undiagnosed diabetes (1). Diabetes has serious consequences, including microvascular, neuropathic, and macrovascular complications, translating to a large public health burden for morbidity, mortality, and economic costs (2,3). This burden would be even greater if not for improved outcomes attributed to successful management of diabetes risk factors. It is well established that improving blood glucose and/or blood pressure levels significantly reduces microvascular complications. In addition, blood pressure and lipid control significantly reduces cardiovascular disease, the major cause of morbidity and mortality for individuals with diabetes. Based on this research, the American Diabetes Association (ADA) has developed Standards of Medical Care in Diabetes, which are used by national programs for preventing and controlling diabetes (4).

The National Diabetes Education Program (NDEP) was established in 1997 to improve treatment and outcomes for people with diabetes. A key objective of the program is to increase diabetes knowledge among patients and health care providers by disseminating research-based information on risk factors, important clinical measures, and techniques for disease management (5). Consequently, the NDEP has campaigned to increase patients’ knowledge of their A1C, blood pressure, and LDL cholesterol (ABC) levels and knowledge of ABC recommendations. The ADA recommends that most people with type 2 diabetes achieve an A1C <7.0%, blood pressure <130/80 mmHg, and LDL cholesterol <100 mg/dL for optimal disease management (5). While risk factor control has improved, nationwide data show control remains suboptimal (6,7). However, there are little data on the prevalence of knowledge of ABC levels and targets among people with diabetes and whether this knowledge is associated with meeting ABC recommendations.

Randomized controlled trials aimed to increase diabetes knowledge have effectively improved clinical outcomes. Face-to-face individual and group diabetes education sessions in newly diagnosed type 2 diabetes (8), intensive management programs in patients with poorly controlled diabetes (9), and frequent phone contact (10) have all improved the ABCs compared with control subjects. These trials combined motivational/behavior change efforts with education; however, a trial that provided participants with only written A1C information showed improvements only in those with poor glucose control (11). Observational studies have been more equivocal, with one study showing no association between ABC knowledge and control (12) and another showing a positive association between A1C knowledge and accurate assessment of diabetes control (13).

Given the limited data from observational studies, we examined diabetes knowledge in a nationally representative sample to describe the prevalence of ABC knowledge and its variation by patient characteristics. To further understand the gap between knowledge and clinical outcomes, we determined multivariate associations between diabetes knowledge and achieving ABC recommendations in people with type 2 diabetes.

RESEARCH DESIGN AND METHODS

The National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES), previously described (14), is a stratified multistage probability cluster survey conducted in the noninstitutionalized population (14). The survey includes 1) an in-home interview through which demographic and basic health information are obtained and 2) a physical examination and laboratory measures taken at a mobile examination center (MEC).

Study population

Participants were adults aged ≥20 years who completed the 2005–2008 interview and MEC visit and who answered “yes” when asked whether a physician or other health care professional ever told them that they had diabetes (n = 1,251). Since there are no specific clinical guidelines for people with type 1 diabetes, participants likely to have type 1 diabetes were excluded (n = 18), based on age of diagnosis <25 years, insulin use, and initiation of insulin within 1 year of diagnosis.

Diabetes knowledge

Participants who reported having diabetes were asked to report the number of times their A1C was tested in the past year, to which respondents could report they had not heard of A1C. Participants having an A1C test in the past year or who did not know if their A1C was specifically tested in the past year were then asked for their last A1C level. Most recent blood pressure and LDL cholesterol levels were queried similarly. Reported values were not verified. Participants were also asked what their doctor or other health professional said their A1C, blood pressure, and LDL cholesterol level should be. For each knowledge item, responses were categorized by whether participants reported that their physician stated an ABC goal in accordance with ADA recommendations, by whether the reported physician-stated goal was above the ADA recommendations, by stating that their provider did not specify a goal, or by not knowing what goal the provider specified.

Clinical measures

At the MEC, blood pressure was measured using a standardized mercury sphygmomanometer after the participant rested quietly for 5 min; up to four readings were taken and averaged, excluding the first measure (15). A1C measures were standardized to those of the National Glycohemoglobin Standardization Program (15). LDL cholesterol was derived from total cholesterol, triglyceride levels, and HDL cholesterol in participants who fasted properly (8 to <24 h, n = 504) ([LDL cholesterol] = [total cholesterol] – [HDL cholesterol] – [triglycerides/5]) (16).

Statistical analysis

Descriptive statistics (percent [SE]) were used to assess prevalence of diabetes knowledge by participant characteristics and the proportion of participants who met ABC recommendations for each knowledge item. The correlations between actual ABC values measured in the NHANES and self-reported ABC values were determined among participants who were able to state their last level. Multivariable logistic regression (odds ratio [OR] [95% CI]) was used to determine the association between ABC knowledge and achieving ABC recommendations. Models were adjusted for demographics and then additionally adjusted for diabetes-related factors (all self-reported and specified in the footnote to Table 4). Statistical analyses used sample weights and accounted for the cluster design (Release 9.2, 2008; SUDAAN User’s Manual, Research Triangle Institute).

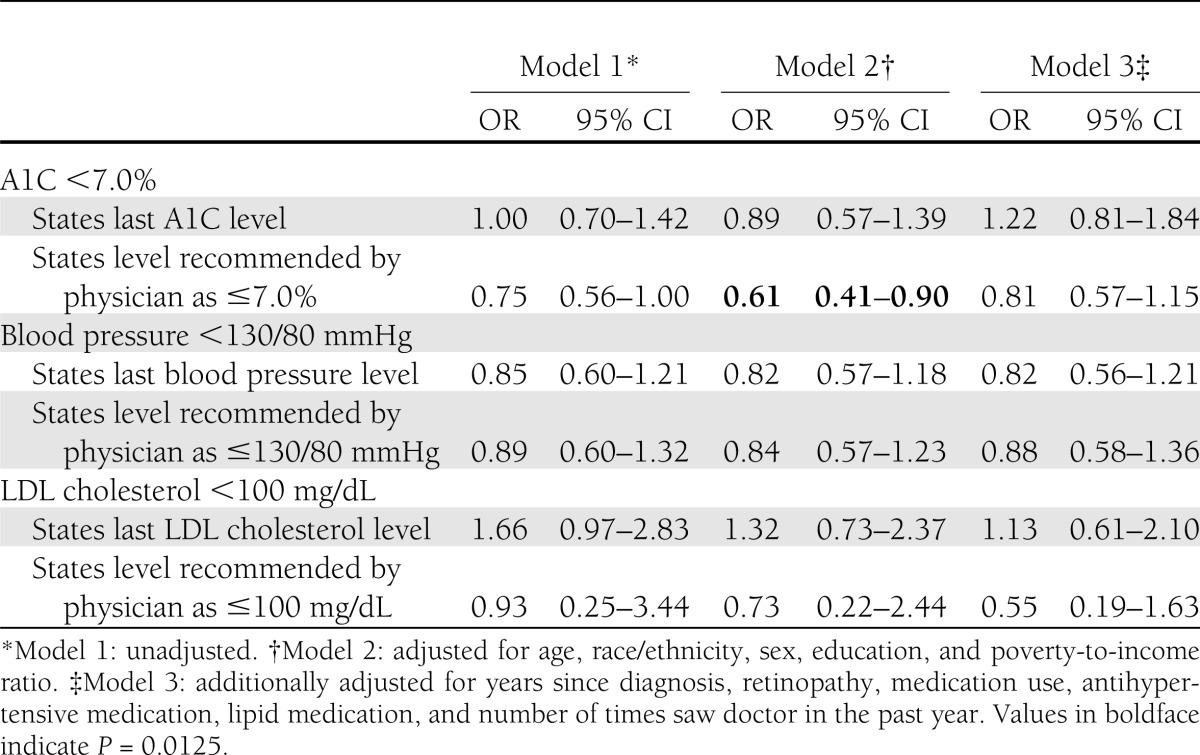

Table 4.

OR (95% CI) of meeting A1C, blood pressure, and LDL cholesterol recommendations by diabetes knowledge

RESULTS

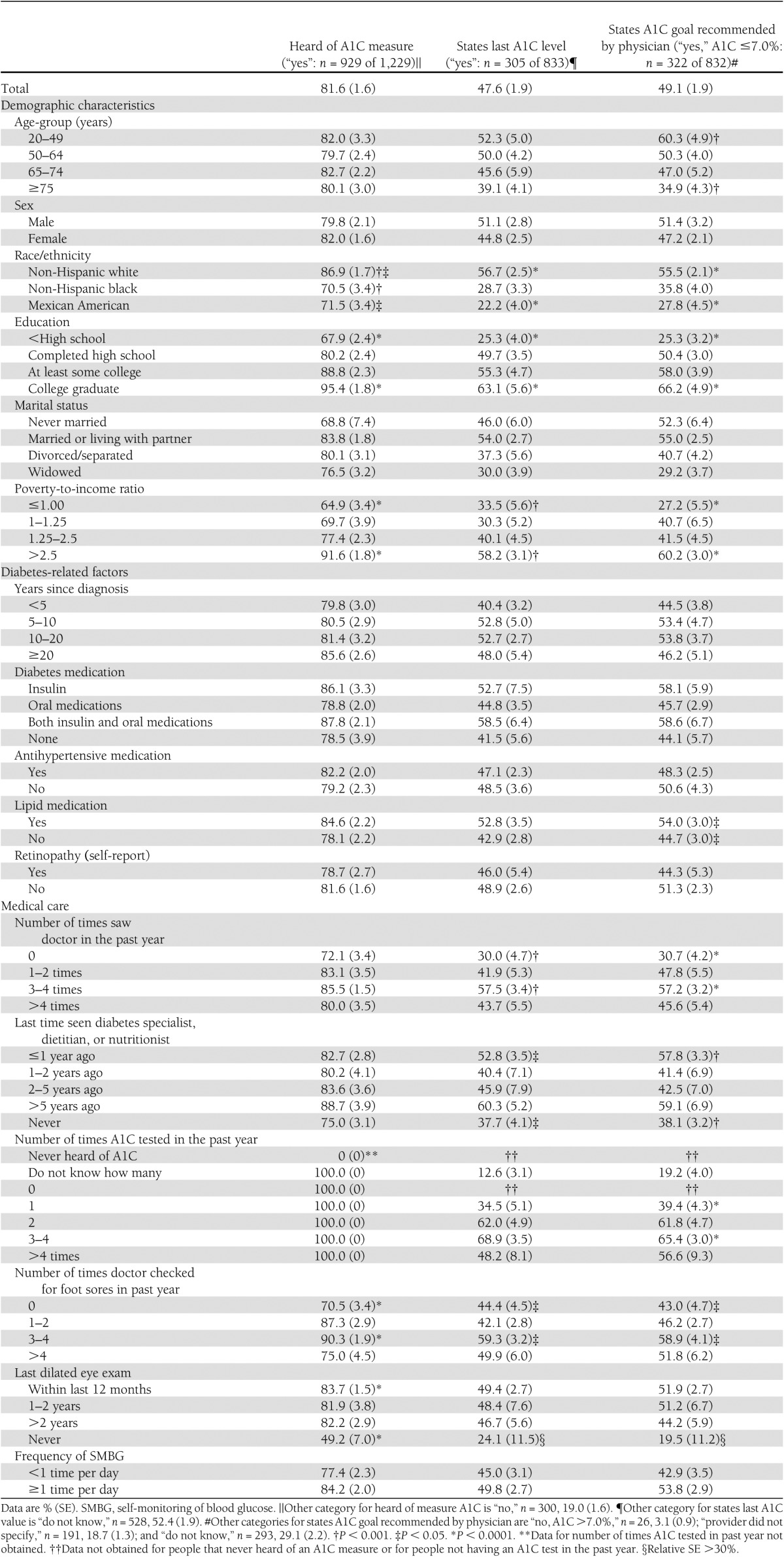

Prevalence of A1C knowledge by participant characteristics

Eighty-two percent of participants had heard of the measure A1C (Table 1). Among participants familiar with A1C and tested in the past year, 48% stated their last A1C level, although values could not be confirmed by physician records. Knowledge of A1C level was greatest in non-Hispanic whites and lowest in Mexican Americans, greater with increasing education, and greater in people with higher income. People seeing a doctor in the past year or having their A1C tested several times in the past year more frequently stated their last A1C level. Having several foot exams performed by a physician in the past year was also associated with more knowledge. However, for unknown reasons, knowledge decreased when the frequency exceeded four times per year. Similar relationships by race/ethnicity, education, marital status, and income persisted for those who reported that their physician specified an A1C goal in accordance with ADA recommendations. Few reported their physician recommending an A1C goal >7% (n = 26, 3%), and 19% stated that their provider did not specify an A1C goal (data not shown). For participants who had heard of the A1C measure, similar differences were found by race/ethnicity, education, income, and examinations for eye and foot complications. Overall, there was no significant difference in any knowledge measure by sex, years since diagnosis, glycemic medication use, or self-monitoring of blood glucose, regardless of insulin use.

Table 1.

Prevalence of knowledge about A1C among the U.S. population aged ≥20 years with diabetes (NHANES 2005–2008) by demographic characteristics, diabetes-related factors, and medical care (n = 1,233)

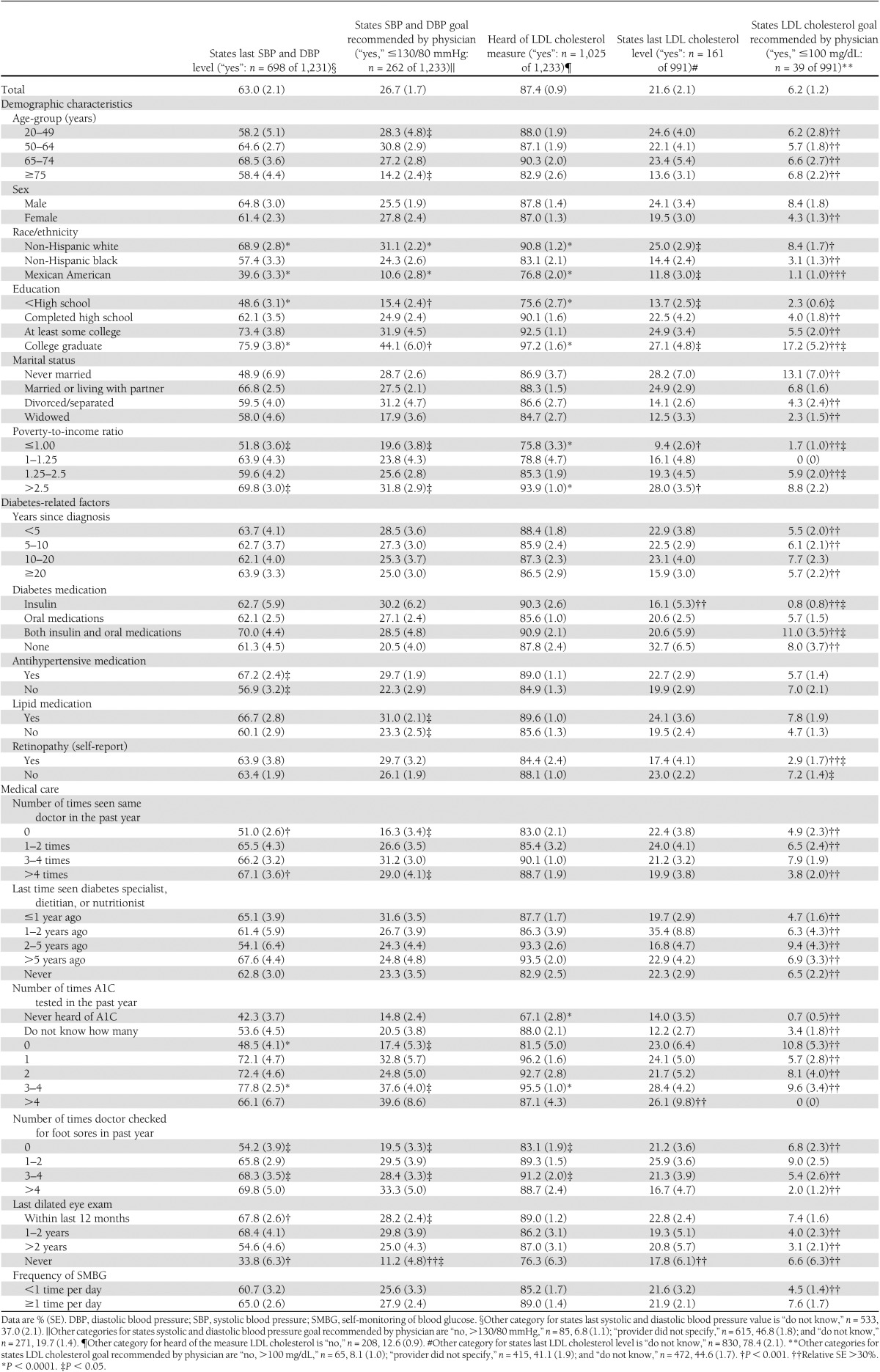

Prevalence of blood pressure and LDL cholesterol knowledge by participant characteristics

Sixty-three percent of participants stated their last blood pressure level; 87% had heard of the measure LDL cholesterol, but only 22% stated their last LDL cholesterol level (Table 2). Reported blood pressure and LDL cholesterol levels could not be verified. Similar to results for A1C, stating last blood pressure and LDL cholesterol level was greatest in non-Hispanic whites compared with Mexican Americans and higher with more education and income. Participants who reported taking antihypertensive medications or reported having several A1C tests, a dilated eye exam, or several foot exams in the past year had more knowledge of their last blood pressure level. Similar to A1C, relationships by demographics, medication use, and A1C testing frequency and having examinations for eye complications persisted for those who reported their physician-specified blood pressure and LDL cholesterol goals in accordance with ADA recommendations. Few participants reported their physician recommending a blood pressure goal >130/80 mmHg (n = 85, 7%) or LDL cholesterol goal >100 mg/dL (n = 65, 8%) (data not shown). Forty-seven percent and 41% of participants reported that their provider did not specify a goal for blood pressure or LDL cholesterol, respectively. Similar to A1C, having heard of the LDL cholesterol measure was greatest in non-Hispanic whites and higher in people with more income and education and in those with more A1C tests in the past year.

Table 2.

Prevalence of diabetes knowledge about blood pressure and LDL cholesterol among the U.S. population aged ≥20 years (NHANES 2005–2008) by demographic characteristics, diabetes-related factors, and medical care (n = 1,233)

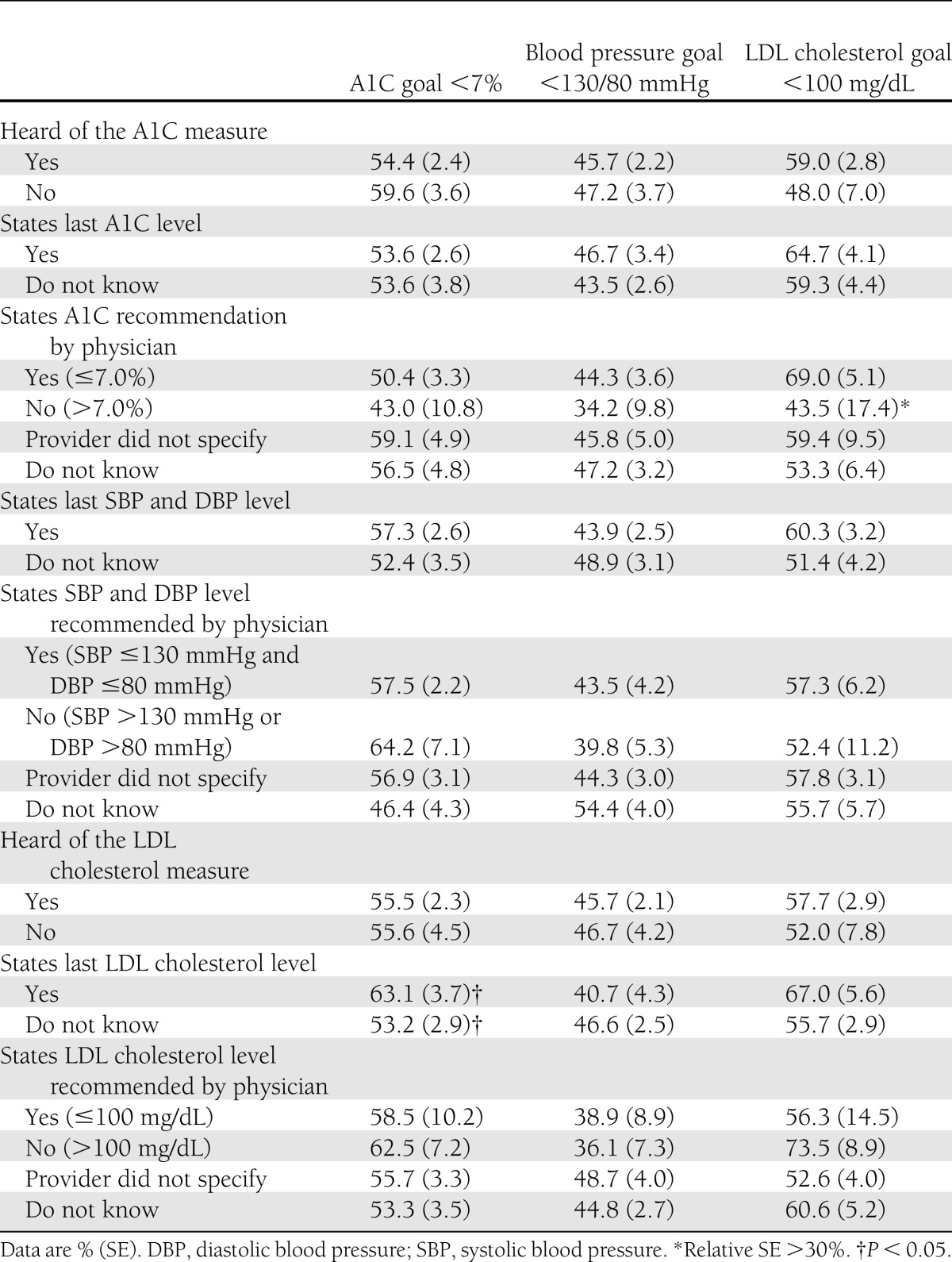

Diabetes knowledge and percent meeting ABC recommendations

Participant knowledge of their last ABC level was not associated with meeting ABC goals, with the exception of people who knew their last LDL cholesterol level (63% vs. no, 53% for A1C <7.0%; P = 0.046) (Table 3). Having knowledge of A1C goals was more favorably associated with meeting LDL cholesterol recommendations than meeting A1C recommendations (69 vs. 50%, respectively).

Table 3.

Percent meeting recommended A1C, blood pressure, and LDL cholesterol goals by measure of diabetes knowledge among the U.S. population aged ≥20 years with diabetes: NHANES 2005–2008

Correlation between self-reported and actual ABC levels

Among people who self-reported good glucose control (A1C <7.0%), 83% had an actual A1C <7.0%; 15% had an actual A1C 7–7.9% (correlation analysis, data not shown). The respective correlations for those who reported good blood pressure control were 66% for systolic blood pressure and 85% for diastolic blood pressure; for those who reported good LDL cholesterol control, the respective correlation was 90%. Among all participants, 38% reported that they had good control and had an actual A1C measure <7.0%. The respective correlations were 39% for systolic blood pressure, 63% for diastolic blood pressure, and 39% for LDL cholesterol.

Impact of diabetes knowledge on meeting ABC recommendations by logistic regression

In general, ABC knowledge was not significantly associated with meeting ABC clinical recommendations in multivariable logistic regression analysis (Table 4). Participants who reported that their physician specified an A1C <7.0% goal were significantly less likely to have an actual A1C <7.0% after adjusting for demographic characteristics (OR 0.61 [95% CI 0.41–0.90]). This relationship became statistically nonsignificant after adjustment for disease severity and diabetes-related factors (0.81 [0.57–1.15]). Interaction terms between knowledge and disease severity were not significant.

CONCLUSIONS

The National High Blood Pressure Education Program was established in 1972, the National Cholesterol Education Program in 1985, and the NDEP in 1997 (17–19). These programs all have a “know your numbers” component addressing targets for risk factor control. Despite these efforts, few nationally representative studies have examined knowledge about the ABCs and its association with patient characteristics and risk factor control. We found that ABC knowledge was greatest among non-Hispanic whites and those with higher education and income. In addition, routine foot checks by a regular doctor, which may be a proxy for quality of care, were significantly associated with more A1C knowledge. Although we did not conduct an intervention study, the lack of a significant association between knowledge and meeting ABC recommendations suggests that the “know your numbers” campaigns by themselves may make limited contributions to improving risk factor control.

Cardiovascular disease is the major cause of morbidity and mortality in people with diabetes. Despite much stronger evidence for cardiovascular disease risk reduction with blood pressure and LDL cholesterol control than glycemic control, 49% of people reported being given an A1C target in accordance with ADA recommendations by their physician compared with only 27% for blood pressure and 6% for LDL cholesterol. It is also striking that nearly three times as many could state their blood pressure than their LDL cholesterol, with only 22% knowing their last LDL cholesterol result despite 87% having heard of LDL cholesterol. In another high-risk population that included patients hospitalized with coronary artery disease, only 8% knew their last LDL cholesterol and 5% knew their LDL cholesterol target (20). These patients, of whom 31% had diabetes, were similar to our diabetes population, with 66% recalling their blood pressure level (versus 63% in our study); 49% knew their target value, while 27% did in our study.

Previous studies of knowledge of A1C have yielded inconsistent findings. In the study by Iqbal et al. (11), only those with poorly controlled glucose who were unfamiliar with the term A1C at baseline showed improvements in their A1C level after a diabetes information session (−1.2%, P = 0.04), whereas for most in the study there was no significant association. However, almost one-half of the patients in the study by Iqbal et al. had type 1 diabetes, where A1C control may be more challenging than it is for type 2 diabetes. Similarly, patients who gained knowledge after diabetes self-management education but who initially had poor knowledge were significantly more likely to achieve the A1C target compared with those who showed no improvement in knowledge; again, the study sample was not representative of the U.S. population, as it was hospital based and included mainly minorities with poorly controlled diabetes (21). Sánchez et al. (12) found no correlation between diabetes risk factor knowledge and A1C or LDL cholesterol control for patients with diabetes admitted to the hospital with acute coronary syndrome. Comparison with our study is difficult owing to differences in the knowledge questionnaire and the highly selective study population. In a small hospital-based prospective study, those who knew the A1C goal had better control several years after an education session and repeated follow-up visits where health providers emphasized the goal; nevertheless, almost one-half did not recognize the term A1C and less than one-quarter knew the A1C target (22). Finally, Heisler et al. (13) reported that among an ethnically diverse sample of adults with diabetes, those who knew their last A1C values were more likely to accurately assess their diabetes control (OR 1.59 [95% CI 1.05–2.42]). However, the central study questions differed; Heisler et al. addressed diabetes control using perceived and objective measures of A1C, whereas in our study, only objective clinical measures of control were used. Despite these inconsistent findings, controlled trials that have aimed to increase diabetes knowledge, including interventions focused on diabetes self-management education, have been effective in improving clinical outcomes (8–10,23,24). Nevertheless, effective interventions have included several educational and behavioral components; ABC knowledge alone may not be sufficient to improve risk factor control. Solutions translating these short-term gains into lifetime control are needed for people with diabetes.

While previous studies in people with diabetes are inconclusive, our findings are consistent with studies of knowledge of blood pressure and LDL cholesterol in a coronary artery disease population, which also found few associations between knowledge and meeting risk factor targets (20,25). There may be several reasons for not finding an association. First, poorly controlled patients may be more likely to receive education from physicians and referral to diabetes educators compared with patients with well-controlled ABC levels; however, even with ABC knowledge, these patients may not be biologically able to achieve goals. We found that participants who reported that their physician recommended an A1C goal <7% were significantly less likely to achieve an A1C <7%. After adjustment for several proxies of disease severity, this association became nonsignificant, which suggests that disease severity may confound the association between knowledge and achieving the A1C goal. Second, education about risk factors without a behavioral change component may be ineffective. Diabetes education that additionally addresses barriers to self-care and personal motivators may increase the number of patients who reach ABC targets.

We found that a greater proportion of those who reported lower A1C values did so accurately compared with those who reported higher A1C values. Among participants who reported that their A1C was <7.0%, 83% had an actual A1C measure of <7.0%. In contrast, among participants who reported an A1C ≥10%, only 37% actually had an A1C measure in that range. A similar variation was found in an ethnically diverse sample of patients with type 2 diabetes (13) and by blood pressure and LDL cholesterol in our study. In another study, 67% of patients reporting an A1C value were within 1.0% of the actual value that was documented within the last year in their medical record (26). These findings have implications for interpretation of surveys of control using self-reported measures. In addition, validity may be much higher for those reporting good control compared with those reporting poor control.

A major strength of our study was the use of a nationally representative sample, allowing generalization to the U.S. adult noninstitutionalized population. Multiple clinical outcomes were analyzed using standardized procedures, which provided a comprehensive look at the ABCs. Our study is limited in that only a few items were used to characterize diabetes knowledge and the cross-sectional data impede the ability to verify any causal relationships. Since few people reported a physician-specified LDL cholesterol goal, most estimates had relative SEs >30%; nevertheless, we found significant values by medication use and retinopathy and found similar trends by demographics. Self-reported ABC levels could not be verified, but in a small subanalysis, correlation analysis suggested that among those with good control, participants were generally correct in assessing their control. In addition, reported versus actual A1C values that were documented up to a year prior were found to be very similar in the study by Harwell et al. (26). Finally, variation in laboratory calibration methods and the time period between self- reported and NHANES tests for A1C may increase error in correlation analysis.

Given the enormous public health burden of diabetes, future work should delineate factors associated with meeting ABC recommendations using a multifaceted approach. While a patient’s ABC knowledge may be important, it is unlikely that this alone would profoundly improve diabetes control. New strategies extending beyond a “know your numbers” approach must be developed to translate research on the benefits of risk factor control into better outcomes for patients with diabetes. Understanding the interaction between demographics, knowledge, and other diabetes-related factors may provide insight for improving diabetes control and reducing diabetes complications. In addition, the communication that physicians, health care professionals, and diabetes educators have with patients is important for improved diabetes outcomes.

Acknowledgments

This work was financially supported by the National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases (HHSN267200700001G).

No potential conflicts of interests relevant to this article were reported.

The findings and conclusions in this report are those of the authors and do not necessarily represent the views of the National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, or National Institute on Deafness and Other Communication Disorders.

S.S.C. contributed to the research design, analyzed data, and wrote, reviewed, and edited the manuscript. N.R.B. contributed to the discussion and reviewed and edited the manuscript. L.S.G. and K.E.B. researched data and reviewed and edited the manuscript. J.E.F. contributed to the discussion and reviewed and edited the manuscript. C.C.C. contributed to the research design and the discussion and reviewed and edited the manuscript. S.S.C. is the guarantor of this work and, as such, had full access to all the data in the study and takes responsibility for the integrity of the data and the accuracy of the data analysis.

Parts of this study were presented in abstract form at the 71st Scientific Sessions of the American Diabetes Association, San Diego, California, 24–28 June 2011.

References

- 1.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention National Diabetes Fact Sheet: National Estimates and General Information on Diabetes and Prediabetes in the United States, 2011. Atlanta, GA, U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 2011 [Google Scholar]

- 2.American Diabetes Association Economic costs of diabetes in the U.S. in 2007. Diabetes Care 2008;31:596–615 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. National Diabetes Surveillance System [article online]. Available from http://apps.nccd.cdc.gov/DDTSTRS/NationalSurvData.aspx Accessed 10 April 2011

- 4.American Diabetes Association Standards of medical care in diabetes—2011. Diabetes Care 2011;34(Suppl. 1):S11–S61 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.National Institutes of Health and Centers for Disease Control and Prevention National Diabetes Education Program. Bethesda, MD, U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, 2010 [Google Scholar]

- 6.Cheung BM, Ong KL, Cherny SS, Sham PC, Tso AW, Lam KS. Diabetes prevalence and therapeutic target achievement in the United States, 1999 to 2006. Am J Med 2009;122:443–453 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Saydah SH, Fradkin J, Cowie CC. Poor control of risk factors for vascular disease among adults with previously diagnosed diabetes. JAMA 2004;291:335–342 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Rickheim PL, Weaver TW, Flader JL, Kendall DM. Assessment of group versus individual diabetes education: a randomized study. Diabetes Care 2002;25:269–274 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Rothman RL, Malone R, Bryant B, et al. A randomized trial of a primary care-based disease management program to improve cardiovascular risk factors and glycated hemoglobin levels in patients with diabetes. Am J Med 2005;118:276–284 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Coberley CR, McGinnis M, Orr PM, et al. Association between frequency of telephonic contact and clinical testing for a large, geographically diverse diabetes disease management population. Dis Manag 2007;10:101–109 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Iqbal N, Morgan C, Maksoud H, Idris I. Improving patients’ knowledge on the relationship between HbA1C and mean plasma glucose improves glycaemic control among persons with poorly controlled diabetes. Ann Clin Biochem 2008;45:504–507 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Sánchez CD, Newby LK, McGuire DK, Hasselblad V, Feinglos MN, Ohman EM. Diabetes-related knowledge, atherosclerotic risk factor control, and outcomes in acute coronary syndromes. Am J Cardiol 2005;95:1290–1294 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Heisler M, Piette JD, Spencer M, Kieffer E, Vijan S. The relationship between knowledge of recent HbA1C values and diabetes care understanding and self-management. Diabetes Care 2005;28:816–822 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, National Center for Health Statistics. National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey Hyattsville, MD, U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 2008 [Google Scholar]

- 15.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, National Center for Health Statistics National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey Examination Protocol. Hyattsville, MD, Department of Health and Human Services, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 2008 [Google Scholar]

- 16.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, National Center for Health Statistics National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey Laboratory Protocol: Cholesterol and Triglycerides. Hyattsville, MD, U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 2008 [Google Scholar]

- 17.National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute. National High Blood Pressure Education Program [article online], 2011. Available from http://www.nhlbi.nih.gov/about/nhbpep/nhbp_pd.htm Accessed 15 September 2011

- 18.National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute. National Cholesterol Education Program [article online], 2011. Available from http://www.nhlbi.nih.gov/about/ncep/ Accessed 15 September 2011

- 19.National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. National Diabetes Education Program [article online], 2011. Available from http://www.ndep.nih.gov Accessed 15 September 2011

- 20.Cheng S, Lichtman JH, Amatruda JM, et al. Knowledge of cholesterol levels and targets in patients with coronary artery disease. Prev Cardiol 2005;8:11–17 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Berikai P, Meyer PM, Kazlauskaite R, Savoy B, Kozik K, Fogelfeld L. Gain in patients’ knowledge of diabetes management targets is associated with better glycemic control. Diabetes Care 2007;30:1587–1589 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Agrawal V, Korb P, Cole R, et al. Patients who know the A1c goal have better glycemic control (Abstract). Diabetes 2005;54(Suppl. 1):A74 [Google Scholar]

- 23.Norris SL, Engelgau MM, Narayan KM. Effectiveness of self-management training in type 2 diabetes: a systematic review of randomized controlled trials. Diabetes Care 2001;24:561–587 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Norris SL, Lau J, Smith SJ, Schmid CH, Engelgau MM. Self-management education for adults with type 2 diabetes: a meta-analysis of the effect on glycemic control. Diabetes Care 2002;25:1159–1171 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Cheng S, Lichtman JH, Amatruda JM, et al. Knowledge of blood pressure levels and targets in patients with coronary artery disease in the USA. J Hum Hypertens 2005;19:769–774 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Harwell TS, Dettori N, McDowall JM, et al. Do persons with diabetes know their (A1C) number? Diabetes Educ 2002;28:99–105 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]