Abstract

Objectives

To explore potentials for avoiding humiliations in clinical encounters, especially those that are unintended and unrecognized by the doctor. Furthermore, to examine theoretical foundations of degrading behaviour and identify some concepts that can be used to understand such behaviour in the cultural context of medicine. Finally, these concepts are used to build a model for the clinician in order to prevent humiliation of the patient.

Theoretical frame of reference

Empirical studies document experiences of humiliation among patients when they see their doctor. Philosophical and sociological analysis can be used to explain the dynamics of unintended degrading behaviour between human beings. Skjervheim, Vetlesen, and Bauman have identified the role of objectivism, distantiation, and indifference in the dynamics of evil acts, pointing to the rules of the cultural system, rather than accusing the individual of bad behaviour. Examining the professional role of the doctor, parallel traits embedded in the medical culture are demonstrated. According to Vetlesen, emotional awareness is necessary for moral perception, which again is necessary for moral performance.

Conclusion

A better balance between emotions and rationality is needed to avoid humiliations in the clinical encounter. The Awareness Model is presented as a strategy for clinical practice and education, emphasizing the role of the doctor's own emotions. Potentials and pitfalls are discussed.

Keywords: Behaviour, emotions, general practice, moral obligations, physician–patient relations

We, the authors of this article, prefer to regard ourselves as reflective general practitioners, endorsing the principles of patient-centredness and trying to do our best for the benefit of our patients. Yet, we admit that our consultations have occasionally taken an unfortunate course, where our contributions apparently made things worse for the patient. Although we never meant to intimidate him or her, patients are at high risk of experiencing shame and humiliation in any medical encounter [1]. Patients with mental illness, chronic pain, or medically unexplained disorders have reported experiences of being met with scepticism and lack of comprehension, feeling rejected, ignored, and being belittled, and blamed for their condition [2–5]. Healthy individuals who discussed their risk of future disease complained about how doctors could evoke in them feelings of uncertainty and worry [6].

Exploring power issues in clinical medicine, Thesen describes how and explains why doctors may take up the role of oppressor, realizing that most episodes of intimidation are unintended and even unrecognized by the oppressor [7]. The medical encounter, like all human interaction, is unavoidably emotion laden [8]. Zinn points to the significance of self-awareness in the doctor as the key to utilizing emotional reactions to improve the doctor–patient relationship.

In this article, we shall explore potentials for avoiding humiliations in clinical encounters, especially those which are unintended and unrecognized by the doctor. We shall examine theoretical foundations of degrading behaviour and identify some concepts that can be used to understand such behaviour in the cultural context of medicine. These concepts will be used to build a model for the clinician who wants strategies to avoid humiliation of the patient.

Theoretical foundations of humiliation

Pursuing the perspectives of moral ethicists such as Levinas [9], Skjervheim, Vetlesen, and Bauman have presented philosophical and sociological analyses to explain degrading behaviour between human beings. Focusing on concepts such as objectivism, distantiation, and indifference, they all point to the rules of the cultural system, rather than accusing the individual of bad behaviour. Below, we present these positions briefly, focusing on the points we regard as most relevant to understand the cultural context of the medical profession.

Objectivism and disempowerment

According to Skjervheim, objectivism is a mode of understanding which presumes that reality exists apart from the human mind, and that the knowledge of this reality is based upon observation [10]. He referred especially to the disciplines of psychology and education, warning against a tendency to accept objectivism as a normal mode of professionalism. Communication where one person neglects the meaning of the other by taking his/her own observation as a matter of fact will suffer the loss of humanity, says Skjervheim [10].

Thesen identifies objectivism in Skjervheim's sense as the foundation of disempowerment [7], while the opposite is a principle of subjectivity where human actions are regarded as intentional. The Other is seen as conscious of a matter, and not just as the matter itself. Medical practice can involve subject–subject relationships as well as subject–object relationships. Translated to the clinical encounter, Skjervheim's objectivism concept can prevail when the doctor makes the patient into an object of study instead of meeting him/her as a fellow individual, for example by classifying the other as “a mental case”, without trusting the patient's symptom experience.

Distantiation and moral neutralization

Bauman explores tendencies in modern culture, taking the horrors of the Holocaust as his point of departure [11]. The Holocaust would not have been possible without an extensive fascination with rational organization and the cultivation of technical skills, orderliness, and unambiguity developed by modernity, says Bauman. His reasoning draws on Milgram's experiments of obedience to authority. Milgram describes how the sense of responsibility, raised as a moral appeal, can be undermined [12]. Crucial to this is the observation of how distantiation and moral neutralization are related. It is difficult to harm a person we can touch. Bauman's analysis explains how responsibility can arise out of the proximity of the other, while the invisible other is a morally lost other. Bauman claims that the more rational the organization of action, the easier it is to cause suffering. The evils of the Holocaust cannot be inferred in the medical consultation, but the trends of rationality, efficiency, and distantiation can clearly be recognized in the medical culture. Bauman's analysis distinguishes between evil individuals and malevolence rendered possible by cultural traits. Thus, the issue of proximity may point to matters relevant to the unintended intimidations in clinical encounters.

Indifference and dissociation

Vetlesen examines the preconditions for moral performance in the individual subject [13]. In order to identify a situation as carrying moral significance, a person needs the basic emotional faculty of empathy. Thus, indifference and distance, in the sense of low emotional involvement, are a prime threat to morality, which according to Vetlesen is even more destructive for morality than hatred or resentment. Vetlesen shows how moral performance is constituted through perception, judgement, and action, with an interplay between the emotional and cognitive faculties of the person [14]. Moral perception is required to recognize the other as a moral addressee, as someone who will be affected by one's moral performance. Vetlesen argues that to feel it is necessary to see and subsequently interact morally with someone. He calls for a better balance to be achieved between rationality and emotion for moral performance. Relevant to prevention of intimidations in the clinical encounter is Vetlesen's emphasis on the essential role of emotional involvement where people remain connected to their doings. Processes of distantiation, dissociation, and abstraction, on the other hand, represent inherent perils for moral perception and performance [13].

The cultural context of medicine

The theoretical perspectives presented above point to the impact of the cultural context of medicine when doctors behave in ways perceived as humiliating by patients. We shall hence take a look at the cultural rules of the medical profession – a system conveying strong authority, which doctors would be expected to obey [10]. More specifically, we try to identify aspects of the professional identity of doctors that might legitimize and contribute to destructive processes like those described above.

The professional ideals and authority of medicine

Parsons describes the foundations of the authority exercised by professional practitioners, where the institutionalized rationality of science provides normative standpoints such as “objective truth” [15]. Since the professional role is grounded on technical competence, disinterestedness is of great functional significance to the modern professions, especially for medicine, says Parsons. Yet, objects Freidson, in his commitment to action, the medical practitioner is different from the scientist [16]. Professional ideals are often different from the operative norms of performance. Freidson concludes that the physician's attitudes are marked by a profound ambivalence. On the one side he/she has a more than ordinary sense of uncertainty and vulnerability; on the other, he/she has a sense of virtue and pride, if not superiority. Although several decades have passed since Parsons and Freidson presented these descriptions, we still observe these professional traits in modern medicine, although perhaps in more subtle ways.

The professional ideals of medicine are summarized by Epstein and Hundert [17], including communication, knowledge, technical skills, clinical reasoning, emotions, values, and reflection in daily practice for the benefits of the individual and the community. However, the integrative ability to think, feel, and act like a physician is the core competence. Epstein and Hundert call for awareness of the affective and moral domains of practice.

Becoming a doctor – professional enculturation

Professional enculturation is a fundamental part of the educational process, and all socialization involves a moral dimension. Sinclair demonstrates how attitudes, habits, and behaviours are internalized by students adopting the norms from hospital hierarchies. Students talk about how people are categorized as good and bad patients, based on their capacity to present ‘hard fact’ evidence [18]. During their educational years, medical students are probably exposed more strongly to the cultural expectations and ideals mediated by the academic professional culture than to the pragmatic adaptations of everyday practice. Good concluded after anthropological fieldwork among students at Harvard Medical School that medicine conceives of the human body and disease in a culturally distinctive fashion. The basic sciences – anatomy, histology, and biochemistry – provide a particular model of reality and a new language regarding the body, which remains with the medical student throughout his or her career [19]. We – the authors – realize that such conceptions still inhabit our minds and sometimes hamper our patient-centred intentions.

Christakis & Feudtner reflect on the interplay of social and emotional forces in the ethical lives of medical trainees [20]. They point to the problems that the evanescent nature of medical students’ relationships with others create in their lives, the strategies they often use to address these problems, and the deleterious consequences these strategies may have on their behaviour and ethical development. Students spend much of their training engaged in transient, time-limited relationships with patients, families, and other care providers. The students prize “efficiency”, avoid intimacy, float above commitment, and show undue deference to authority [20]. Discussing the professional development of the doctor, Hafferty & Franks describe medical school as a moral community where the values, attitudes, beliefs, and related behaviours are observed and internalized [21]. Most of the critical determinants of physician identity operate in a subtle, barely officially recognized “hidden curriculum” where a distinctive medical morality is transmitted. Medical training involves learning new and often conflicting rules about feelings (supposedly detached) and about uncertainty and ambiguity (supposedly not present). Hafferty & Franks call for reorientation of a professional culture where normative issues are not made explicit although they rule professional development [21].

The Awareness Model – a strategy for the clinical encounter

The above review has revealed that medicine is a cultural system with strong authority. Normative standpoints inherited from science such as objectivism, distantiation, and indifference may contribute to the foundations of degrading behaviour between human beings in clinical practice. Obeying the professional values of the system, doctors can compromise their preconditions for moral performance. Being efficient, trusting rationality, and keeping emotions away, moral perception declines while the capacity to harm other people increases.

Yet, we do not lapse into pessimism. The moral systems of medicine also include a strong commitment to humanist values, clearly visible in the ambiguity of normative standpoints presented above [16], [17]. According to the theories we have reviewed, such values could be accessed by developing a better balance between rationality and emotions in the medical culture.

For this purpose, we present the Awareness Model, which is intended to point towards strategies for the clinician who wants to prevent humiliation of the patient.

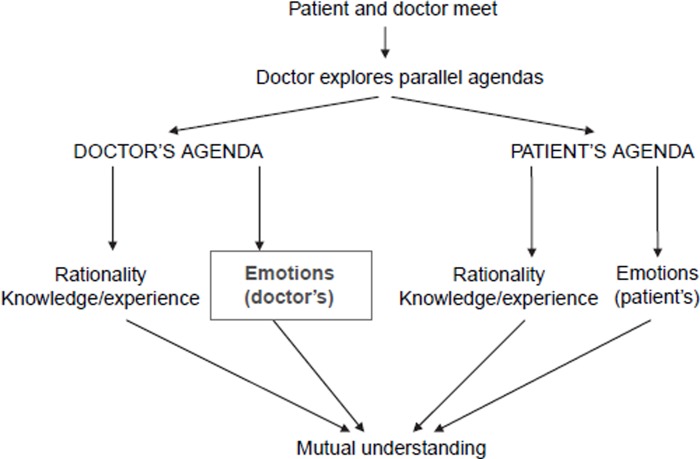

Our point of departure is the model for the patient-centred clinical method, originally presented by Levenstein et al. [22], where the tasks of the doctor are to identify and pursue the medical agenda as well as the patient's agenda (expectations and emotions). However, according to our theoretical elaboration above, awareness of the doctor's emotions is also essential. Hence, we propose a shift of attention from the doctor's rationality, including professional knowledge and experience, towards an emphasis on the doctor's own emotions. We underline the necessity of including parallel agendas, where neither the perspectives of rationality nor emotions are omitted. However, we readily acknowledge that the Awareness Model is meant to provide a tool for shifting the focus of the practitioner from rationality to emotional awareness in the doctor herself or himself. Providing a better balance between vulnerable issues such as emotions – not only on the patient's side – and rationality – not only on the doctor's side – will serve to challenge the inherent threats of objectivism, distantiation, and indifference. Emotions as well as rationality should be recognized as adequate sources for a patient-centred consultation.

We do not intend to prescribe procedures for application beyond the principles presented here. However, the relevance and feasibility of the model – its pragmatic validity – needs to be explored in clinical practice and teaching.

Potentials and pitfalls

Our theoretical review provides strong arguments for a shift in the doctor's attention from rationality to emotion. Exploring the theoretical foundations of humiliation, we have drawn on theories developed to explain horrors far worse that what may occur in a medical consultation [11], [13]. We do not claim that the disempowerment experienced by patients [4], [23] can be compared to the atrocities of the Holocaust. Yet, there is something to learn from the analyses of how unintended intimidation can happen even from the best intentions of the oppressor, who might be a pretty normal person, comparable to ourselves. The structures of power between doctor and patient remind us that the participants are not allowed to claim authority equally in the rhetorical space of the medical consultation [24], [25].

How, then, can the role of the doctor be modified so that it can include intersubjectivity (and not only objectivism), proximity (instead of distantiation), and emotions (not only indifference)? The Awareness Model presented above is intended as a tool for this purpose. The model is elaborated from the patient-centred clinical method, well known among general practitioners for decades [22]. This approach was originally proposed to shift the doctor's attention towards the patient's agenda, including his or her experiences, expectations, and emotions. The model does call attention to the doctor's own emotions. Emotional involvement by the doctor is a fundamental precondition for the empathy taken for granted in the patient-centred clinical method. In 1986, Levenstein et al. wrote:

Entry into the patient's world is a difficult art, requiring of the physician human qualities of empathy, non-judgemental acceptance, congruence and honesty. It also requires a skill in the practice of certain techniques, and it is our conviction that these techniques can be learned and taught. Moreover, the physician cannot be patient-centred unless he has self-knowledge and is prepared to make the changes in attitude and behaviour needed for such an approach. [20]

The Awareness Model proposes that the doctor's agenda, based on a rationality drawn from medical knowledge and clinical experience, needs to be complemented by more than the patient's agenda. Without a reflexive look at his or her own emotions, the doctor runs the risk of creating and re-creating humiliations, irrespective of the best intentions.

Figure 1.

The Awareness Model – a better balance between doctors’ emotions and rationality in the clinical encounter.

Our intention has been to systematize and emphasize resourceful patterns of clinical behaviour, rather than to invent something completely new. We have previously pointed towards another balance necessary to keep in mind during the consultation – the balance between risks and resources. For the purpose of moving towards a better balance between risk thinking and resource thinking, we presented a similar model, the Surplus Model, inviting the practitioner to identify the patients’ self-assessed health resources [26]. These models can complement each other, promoting attitudes and behaviours where vulnerability can be transformed into strength [27].

Farber et al. call attention to the doctor–patient relationship that has become “overly distant” or the opposite “overly involved emotional” and call for a discussion of the balance between clinical objectivity and bonding with the patient [28]. We want to warn against an interpretation of the Awareness Model where emotions are always given priority over rationality. This is not what we advocate. Our starting point after the theoretical review is that awareness of the doctor's own emotions is necessary for the moral perception required for moral performance. Yet, we do not recommend to the doctor such a level of self-awareness that he or she neglects the patient's agenda. Our model states that emotions and rationality are both needed for responsible clinical performance in order to avoid humiliation.

We have previously explored the issue of the doctor's vulnerability in a qualitative study of clinical events when doctors exposed their vulnerability towards patients in a potentially beneficial way [29]. Nevertheless, disclosure of emotions can also be inappropriate as a doctor's behaviour. Discussing this issue, Farber et al. claim that self-disclosure through empathetic validation is not a boundary violation, but helps establish rapport and builda a stronger doctor–patient relationship, while self-protective “self-disclosure” must be condemned [28]. In a study of 589 primary care visits, Beach et al. identified doctors’ disclosure in 17% [30], [31]. They conclude that such self-disclosure encompasses complex and varied communication behaviours, while inadequately intimate self-disclosing statements are rare. For our purposes, we have a stronger belief in empathy-based moral performance, as distinct from unconditional emotional disclosure.

Concluding remarks

The culture of medicine needs to admit and counteract the experiences of humiliation reported by patients [5]. Moral performance rests on moral perception, in the sense of identifying a situation as carrying moral significance. Awareness in the doctor towards his or her own feelings is a foundation for the moral perception needed to prevent unintended degrading behaviour in the clinical encounter. Yet, since the roots of the evil acts can be traced back to the rules of the system, as Bauman remarks [11], a corresponding shift of balance in the medical culture is urgently needed.

References

- 1.Lazare A. Shame and humiliation in the medical encounter. Arch Intern Med. 1987;147:1653–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Thesen J. Being a psychiatric patient in the community – reclassified as the stigmatized “other”. Scand J Public Health. 2001;29:248–55. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Johansson EE, Hamberg K, Lindgren G, Westman G. “I've been crying my way”: Qualitative analysis of a group of female patients' consultation experiences. Fam Pract. 1996;13:498–503. doi: 10.1093/fampra/13.6.498. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Werner A, Isaksen LW, Malterud K. “I am not the kind of woman who complains of everything”: Illness stories on self and shame in women with chronic pain. Soc Sci Med. 2004;59:1035–45. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2003.12.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Malterud K. Humiliation instead of care? Lancet. 2005;366:785–6. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(05)67031-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hvas L, Reventlow S, Malterud K. Women's needs and wants when seeing the GP in relation to menopausal issues. Scand J Prim Health Care. 2004;22:118–21. doi: 10.1080/02813430410005964. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Thesen J. From oppression towards empowerment in clinical practice: Offering doctors a model for reflection. Scand J Public Health. 2005;66(Suppl):47–52. doi: 10.1080/14034950510033372. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Zinn WM. Doctors have feelings too. JAMA. 1988;259:3296–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lévinas E, Hand S. The Levinas reader. Oxford: Blackwell; 1989. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Skjervheim H. Objectivism and the study of man. Oslo: Universitetsforlaget; 1959. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bauman Z. Modernity and the Holocaust. Cambridge: Polity Press; 1989. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Milgram S. Obedience to authority: an experimental view. London: Tavistock; 1974. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Vetlesen A-J. Perception, empathy, and judgment: An inquiry into the preconditions of moral performance. University Park: Penn State University Press; 1994. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Vetlesen A-J. Why does proximity make a moral difference? Praxis International. 1993;12:371–86. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Parsons T. Essays in sociological theoryRev. ed. New York: Free Press; 1964. pp. 34–49. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Freidson E. Profession of medicine: A study of the sociology of applied knowledge. New York: Harper & Row; 1970. pp. 158–84. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Epstein RM, Hundert EM. Defining and assessing professional competence. JAMA. 2002;287:226–35. doi: 10.1001/jama.287.2.226. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Sinclair S. Making doctors: An institutional apprenticeship. Oxford and New York: Berg; 1997. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Good BJ. Medicine, rationality, and experience: An anthropological perspective. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press; 1994. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Christakis DA, Feudtner C. Temporary matters: The ethical consequences of transient social relationships in medical training. JAMA. 1997;278:739–43. doi: 10.1001/jama.278.9.739. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hafferty FW, Franks R. The hidden curriculum, ethics teaching, and the structure of medical education. Acad Med. 1994;69:861–71. doi: 10.1097/00001888-199411000-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Levenstein JH, McCracken EC, McWhinney IR, Stewart MA, Brown JB. The patient-centred clinical method, 1: A model for the doctor–patient interaction in family medicine. Fam Pract. 1986;3:24–30. doi: 10.1093/fampra/3.1.24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Asbring P, Narvanen AL. Women's experiences of stigma in relation to chronic fatigue syndrome and fibromyalgia. Qual Health Res. 2002;12:148–60. doi: 10.1177/104973230201200202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Waitzkin H. The politics of medical encounters: How patients and doctors deal with social problems. New Haven, CT: Yale University Press; 1991. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Code L. Rhetorical spaces: Essays on gendered locations. New York: Routledge; 1995. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Hollnagel H, Malterud K. Shifting attention from objective risk factors to patients' self-assessed health resources: A clinical model for general practice. Fam Pract. 1995;12:423–9. doi: 10.1093/fampra/12.4.423. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Malterud K, Solvang P. Vulnerability as a strength: Why, when, and how? Scand J Public Health. 2005;66(Suppl):3–6. doi: 10.1080/14034950510033291. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Farber NJ, Novack DH, O'Brien MK. Love, boundaries, and the patient–physician relationship. Arch Intern Med. 1997;157:2291–4. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Malterud K, Hollnagel H. The doctor who cried: A qualitative study about the doctor's vulnerability. Ann Fam Med. 2005;3:348–52. doi: 10.1370/afm.314. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Beach MC, Roter D, Larson S, Levinson W, Ford DE, Frankel R. What do physicians tell patients about themselves? A qualitative analysis of physician self-disclosure. J Gen Intern Med. 2004;19:911–16. doi: 10.1111/j.1525-1497.2004.30604.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Beach MC, Roter D, Rubin H, Frankel R, Levinson W, Ford DE. Is physician self-disclosure related to patient evaluation of office visits? J Gen Intern Med. 2004;19:905–10. doi: 10.1111/j.1525-1497.2004.40040.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]