Abstract

Purpose

Respiratory infection is the most common cause for acute exacerbation of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (AE-COPD). The aim of this work was to study the etiology of the respiratory infection in order to assess the usefulness of the clinical and analytical parameters used for COPD identification.

Patients and methods

We included 132 patients over a period of 2 years. The etiology of the respiratory infection was studied by conventional sputum, paired serology tests for atypical bacteria, and viral diagnostic techniques (immunochromatography, immunofluorescence, cell culture, and molecular biology techniques). We grouped the patients into four groups based on the pathogens isolated (bacterial versus. viral, known etiology versus unknown etiology) and compared the groups.

Results

A pathogen was identified in 48 patients. The pathogen was identified through sputum culture in 34 patients, seroconversion in three patients, and a positive result from viral techniques in 14 patients. No significant differences in identifying etiology were observed in the clinical and analytical parameters within the different groups. The most cost-effective tests were the sputum test and the polymerase chain reaction.

Conclusion

Based on our experience, clinical and analytical parameters are not useful for the etiological identification of COPD exacerbations. Diagnosing COPD exacerbation is difficult, with the conventional sputum test for bacterial etiology and molecular biology techniques for viral etiology providing the most profitability. Further studies are necessary to identify respiratory syndromes or analytical parameters that can be used to identify the etiology of new AE-COPD cases without the laborious diagnostic techniques.

Keywords: respiratory viruses, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, exacerbation, diagnostic tests, hospitalization

Introduction

Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) is associated with significant morbidity and mortality, with the World Health Organization estimating its rise from being the fifth to the third leading cause of death by 2030.1 The overall prevalence of COPD in Spain is estimated to be 10.2%.2

COPD is a slow, progressive disease, with patients experiencing episodes of acute deterioration known as exacerbations,3 which increase in frequency and severity with disease progression.

The causes of acute exacerbations of COPD (AE-COPD) are multifactorial. Half of the AE-COPD cases are attributed to respiratory infections (50%), but exacerbations are also associated with pollution, temperature changes, allergens (30%), and other comorbidities (26%) such as heart failure and pulmonary thromboembolism.4

In several studies, the presence of bacteria in AE-COPD has been associated with purulence of the sputum and the presence of inflammatory markers.5,6 In recent years, emerging new diagnostic techniques have revealed a relationship with respiratory viruses.7–10 In addition, the etiology of respiratory infections in AE-COPD patients differs according to the geographic area.11

Currently, AE-COPD patients are treated with antibiotics as the first line of defense, depending on the severity of the COPD and the severity of the exacerbation itself.12 With the emergence of multidrug resistance and increased economic spending on antibiotic therapy, numerous studies have assessed the benefit of antibiotic treatment,13,14 recommending a short course of antibiotic treatment for slight exacerbations.15

Similarly, biological markers such as procalcitonin have been proposed as markers for antibiotic administration in the AE-COPD,16 allowing a reduction in antibiotic prescriptions.

The identification of respiratory viruses as a cause for AE-COPD may help reduce the use of antibiotics. Therefore, it is important to find clinical and analytical parameters that could guide us in identifying the etiology of new AE-COPD cases, especially considering the laborious diagnostic techniques currently used for diagnosis.

The aims of our study were to identify the etiology of respiratory infections in patients hospitalized for AE-COPD using different diagnostic tests and to evaluate the usefulness of the clinical and analytical parameters of the diagnostic process.

Materials and methods

We included patients who were consecutively admitted to the Hospital of Mataró with AE-COPD between April 1, 2005 and March 31, 2007. COPD was defined according to the global initiative for chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (GOLD) criteria,17 with patients exhibiting compatible spirometry measurements and a smoking history of at least ten packs/year. A diagnosis of acute exacerbation (AE) was assumed when a minimum of two Anthonisen criteria18 were present. Any patient with COPD decompensation that was caused by a noninfectious disease was excluded from the study, assuming that the selected patients presented with an upper or lower respiratory tract infection.

Identification was made based on the respiratory infection and dyspnea admission diagnoses from the International Statistical Classification of Diseases, Ninth Revision, Clinical Modification (ICD-9-CM)19,20 (491, 492, 493, 496, 518.81, 464, 465, 466, 519.11, 786.0), excluding the patients who had a known cause of respiratory failure that was different from infectious exacerbation (heart failure, pulmonary thromboembolism, pneumonia). Finally, the patients who met the inclusion criteria and none of the exclusion criteria (severe immunosuppression, the need for mechanical ventilation or admittance to the Intensive Care Unit, arrival from a nursing home, or a terminal stage of the disease) were asked for their informed consent.

The study was approved by the Consorci Sanitari del Maresme Ethics Committee of the Hospital of Mataró.

Demographic data

Upon admission, a complete clinical history and physical exam were performed. Each patient’s demographic and lifestyle characteristics, baseline dyspnea (based on the Dyspnea Scale from the Medical Research Council21), exacerbation history, history of pneumonia, and hospital admissions during the previous year were evaluated.

The contact with family members at home suffering from an upper respiratory tract infection was collected.

Clinical data

We obtained information on each patient’s upper respiratory tract (nasal congestion, rhinorrhea, and sneezing), lower respiratory tract (cough and expectoration), and constitutional symptoms (dysthermia, fever, chills, asthenia, anorexia, headache, arthromyalgia, and impaired consciousness).

Upon admission, the severity of the exacerbation was classified (depending on the presence of respiratory failure, severe cyanosis, baseline dyspnea deterioration, the utilization of accessory muscles, the worsening of blood gas levels, and a blood pH < 7.35), as were the severity of COPD (according to the GOLD criteria)17 and COPD prognosis (according to the body mass, airflow obstruction, dyspnea, and exercise capacity [BODE] multidimensional index).22

Vital signs and anthropometric data were collected from each patient, and a chest radiograph was taken to rule out pneumonia. Baseline spirometry measurements were collected, and each patient’s treatment before and during hospitalization for AE-COPD was recorded.

Analytical data

A baseline blood gas reading, a complete cell blood count (CBC), and basic biochemistry readings (AST, ALT, creatinine, urea, glucose, and electrolytes) were collected from each patient upon arrival to the emergency room. A routine blood analysis that included total protein and a protein profile was performed the following day.

Microbiological study

Conventional sputum

Upon hospital admission, the sputum was collected upon spontaneous expectoration in a conventional manner with or without using mucolytic agents. Sputa were collected before starting antibiotic treatment at the hospital. The sputa were cultured only if the quality criteria were met in a sputum Gram stain (<10 epithelial cells and >25 polymorphonuclear leukocytes).23

Paired serologies

Sera were collected from patients at admission and 4 weeks after the initial collection for a second paired serology. Passive agglutination techniques were used to detect Mycoplasma pneumoniae, and microimmunofluorescence was used to detect Chlamydia species.

Nasopharyngeal lavage (NPL)

The NPL and the nasal exudate that were collected 24 hours after admission were used for viral detection. The different techniques that were performed are detailed below.

Immunochromatography was used to rapidly detect antigens from influenza viruses A and B or respiratory syncytial virus (RSV). The BinaxNOW Influenza A and B® and BinaxNOW RSV® tests (Binax Inc, Scarborough, ME) were used according to the manufacturer’s instructions.

Immunofluorescence techniques were used to detect influenza viruses A and B, adenovirus, parainfluenza virus, and RSV.

The replication of influenza viruses A and B, adenovirus, parainfluenza, rhinovirus, and RSV was detected in cell culture.

We determined the presence of nucleic acids from influenza viruses A and B, RSV A and B, parainfluenza 1, 2, 3, and 4, coronaviruses 229E and OC43, rhinovirus, and metapneumovirus. The RealAccurate™ Respiratory RT-PCR Kit (PathoFinder, Maastricht, Netherlands) was used for the nucleic acid and respiratory virus amplification test, and the QIAamp Viral RNA Mini Kit (QIAGEN Iberia SL, Madrid, Spain) was used to extract RNA from clinical samples. The RealAccurate™ Respiratory RT-PCR kit (PathoFinder) consists of ready-to-use solutions that contain primers and TaqMan probes that were used in accordance with the conditions set by the manufacturer.

Follow-up

In a control visit performed one week after admission or coinciding with hospital discharge, we recorded the evolution of the episode with regards to clinical symptoms, physical examination, and treatment. In conjunction with the earlier episode evaluation, we identified cases of treatment failure (identified as the persistence of hemodynamic alterations, respiratory failure, severe adverse effects, or a lack of treatment response).

The length of hospital stay and possible complications were also included.

Statistical analysis

The data were collected in a Microsoft Access database and analyzed using SPSS for Windows, version 14.0 (IBM Corporation, Armonk, NY).

The qualitative variables are expressed as counts and percentages, while the quantitative variables are expressed as means and standard deviations or interquartile range. Comparisons between means were performed using the Student’s t-test for independent samples or the Mann–Whitney U test for variables that did not meet the criteria of normality. For comparisons of proportions, the Chi-square or Fisher’s exact test was used. In all cases, we considered values of P < 0.05 to indicate significant differences.

To study the relationship between the analytical and clinical parameters and the etiology of AE-COPD, three groups were categorized. Group 1 contained patients for whom a virus was detected with diagnostic tests, group 2 included the patients who exhibited the detection of bacteria only, and group 3 contained patients with unknown etiologies.

Results

During the study period, 718 consecutive patients were admitted to the hospital with a diagnosis of respiratory infection and dyspnea according to ICD-9-CM guidelines.18

We included 155 patients based on the inclusion and exclusion criteria. In six patients with the clinical criteria for chronic bronchitis, spirometry was not performed in the follow-up. Finally, 17 of the 148 remaining patients were excluded because the follow-up spirometry readings were not compatible with an infection.

Thus, we studied 132 patients with AE-COPD of a probable infectious origin who met the inclusion criteria and had no other causes of acute decompensation (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Recruitment flowchart and the identification of eligible patients.

Abbreviations: AE-COPD, acute exacetbation of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease; FVC/FEV1, forced vital capacity to forced expiratory volume in 1 second ratio.

The demographics of the patients and the baseline characteristics of AE-COPD are presented in Tables 1 and 3.

Table 1.

Patient characteristics

| Category/parameter | Total (n = 132) |

|---|---|

| Sociodemographics | |

| Age, mean (SD), years | 72.9 (8.6) |

| Male | 129 (97.7) |

| Body mass index, mean (SD) | 6.8 (4.5) |

| Smokers | 31 (23.5) |

| Occupational risk | 48 (36.4) |

| Influenza vaccination | 91 (68.9) |

| Streptococcus pneumoniae vaccination | 28 (21.2) |

| Acute COPD exacerbation in last year | 89 (67.4) |

| Hospitalization in last year | 47 (35.6) |

| Pneumonia in last year | 8 (6.1) |

| Treatment | |

| Chronic oxygen therapy | 23 (17.4) |

| Chronic antibiotherapy | 15 (11.4) |

| Antibiotics previous hospitalization | 46 (34.8) |

| Corticosteroids previous hospitalization | 44 (33.3) |

| Comorbidities | |

| Hypertension | 62 (47) |

| Diabetes mellitus | 42 (31.8) |

| Auricular fibrillation | 26 (19.7) |

| Ischemic heart disease | 19 (14.4) |

| Neoplasm | 18 (13.6) |

| Sleep apnea-hypopnea syndrome | 14 (10.6) |

| Severity | |

| Pre-bronchodilator spirometry, mean (SD) | |

| FEV1, mL | 1138 (434) |

| FVC, mL | 2415 (720) |

| FEV1, % | 41.3 (15) |

| FVC, % | 61.2 (16.6) |

| Post-bronchodilator spirometry, mean (SD) | |

| FEV1, mL | 1203 (453) |

| FVC, mL | 2565 (733) |

| FEV1/FVC, % | 46.9 (11.2) |

| COPD severity as per GOLD | |

| Mild (>80) | 3 (2.3) |

| Moderate (50–80) | 38 (29) |

| Severe (30–50) | 68 (51.9) |

| Very severe (<30) | 22 (16.8) |

| Baseline BODE score | |

| 0–2 | 43 (32.6) |

| 3–4 | 44 (33.3) |

| 5–6 | 26 (19.7) |

| 7–10 | 7 (5.3) |

Notes: Data are expressed as number (%) unless otherwise indicated. Influenza vaccination within the current influenza season; pneumococcal polysaccharide vaccination within the previous 5 years.

Abbreviations: BODE, body mass, airflow obstruction, dyspnea, and exercise capacity multidimensional index; COPD, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease; FEV1, forced expiratory volume in 1 second; FVC, forced vital capacity; GOLD, global initiative for chronic obstructive pulmonary disease.

Table 3.

Characteristics and severity of AE-COPD

| Category/parameter | Total (n = 132) | Bacterial etiology (n = 33) | Viral etiology (n = 12) | Unknown etiology (n = 84) | P value (viral versus bacterial infection) | P value (known versus unknown infection)* |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Signs and symptoms | ||||||

| Acute onset | 61 (46.2) | 17 (51.5) | 8(61.5) | 36 (43.4) | 0.54 | 0.23 |

| Cough | 114 (86.4) | 29 (87.9) | 13(100) | 70 (84.3) | 0.19 | 0.26 |

| Expectoration | 102 (77.3) | 25 (75.8) | 12 (92.3) | 63 (75.9) | 0.41 | 0.57 |

| Purulent sputum | 59 (57.8) | 15 (60) | 7 (58.3) | 35 (57.3) | 0.59 | 0.70 |

| Fever | 45 (34.1) | 9 (27.3) | 5 (38.5) | 30 (36.1) | 0.50 | 0.80 |

| Chills | 55 (41.7) | 11 (33.3) | 7 (53.8) | 37 (44.6) | 0.19 | 0.54 |

| Nasal congestion | 69 (52.3) | 12 (36.4) | 7 (53.8) | 48 (57.8) | 0.27 | 0.07 |

| Rhinorrhea | 63 (47.7) | 11 (33.3) | 7 (53.8) | 43 (51.8) | 0.19 | 0.16 |

| Sore throat | 29 (22) | 7 (21.2) | 6 (46.2) | 15 (18.1) | 0.14 | 0.17 |

| Headache | 35 (26.5) | 10 (30.3) | 2 (15.4) | 22 (26.8) | 0.46 | 0.92 |

| Arthromyalgia | 46 (34.8) | 8 (24.2) | 4 (30.8) | 32 (39) | 0.71 | 0.13 |

| Sneezing | 67 (50.8) | 13 (39.4) | 8 (61.5) | 45 (54.2) | 0.17 | 0.35 |

| Tearing eyes | 30 (22.7) | 7 (21.2) | 3 (23.1) | 20 (24.1) | 0.89 | 0.76 |

| Hoarseness | 87 (65.9) | 22 (66.7) | 9 (69.2) | 55 (66.3) | 0.86 | 0.89 |

| Asthenia | 104 (78.8) | 28 (84.8) | 11 (84.6) | 63 (76.8) | 0.98 | 0.28 |

| Anorexia | 60 (45.5) | 16 (48.5) | 8 (61.5) | 34 (41.5) | 0.42 | 0.24 |

| Contact with illness | 40 (30.3) | 10 (30.3) | 4 (30.8) | 25 (30.9) | 0.97 | 0.96 |

| Contact with children | 28 (21.2) | 4 (12.1) | 5 (38.5) | 19 (23.2) | 0.92 | 0.63 |

| Contact with ill child | 17 (12.9) | 3 (9.1) | 3 (23.1) | 11 (13.4) | 0.33 | 0.95 |

| Cardiac pulse, mean (SD) | 97.1 (18) | 88.9 (16) | 96.7 (14) | 99.8 (18) | 0.1 | 0.015 |

| Respiration rate, mean (SD) | 28.4 (7.3) | 27.9 (8.3) | 27.2 (6.1) | 28.7 (7) | 0.98 | 0.37 |

| Analytical tests, mean (SD) | ||||||

| pH | 7.42 (0.06) | 7.44 (0.05) | 7.44 (0.04) | 7.4 (0.6) | 0.98 | 0.002 |

| PaCO2, mmHg | 44.1 (9.2) | 43.1 (8) | 40.5 (5.9) | 45 (9.9) | 0.53 | 0.16 |

| PO2, mmHg | 57.4 (14.3) | 58 (9.8) | 63 (8.2) | 56.7 (16) | 0.10 | 0.048 |

| SatO2, % | 88.2 (7) | 89.7 (4.8) | 92.2 (2.9) | 87.2 (7.6) | 0.08 | 0.006 |

| Leukocytes, ×103/mm | 12994 (5) | 11991 (5) | 10590 (3) | 13293 (5) | 0.29 | 0.04 |

| Lymphocytes, % | 11.3 (7) | 13.8 (8.8) | 9.3 (7) | 10.7 (5.9) | 0.034 | 0.40 |

| Alanine transferase, U/L | 22.4 (12.5) | 24.1 (10) | 23.9 (11.4) | 21.7 (13) | 0.64 | 0.03 |

| Creatinine, mg/dL | 1.03 (0.9) | 0.84 (0.2) | 0.93 (0.3) | 1.11 (1) | 0.24 | 0.03 |

| Gamma globulin, % | 12.8 (4) | 13.8 (4.8) | 11.4 (2.4) | 12.6 (3.8) | 0.05 | 0.25 |

| AE-COPD severity | ||||||

| Post-BD FEV1, % predicted | 44.1 (15) | 39.4 (13.6) | 44.3 (15) | 46.4 (15) | 0.15 | 0.045 |

| Hospitalization last 6 months | 45 (34.1) | 13 (39.4) | 4 (30.8) | 28 (33.3) | 0.74 | 0.67 |

| Disease duration, mean (SD), d | 7.8 (7.5) | 8 (7.6) | 8.15 (8.7) | 7.7 (7.4) | 0.91 | 0.88 |

| Hospital stay, mean (SD), d | 9.2 (6.8) | 11.7 (7.8) | 7.5 (4) | 8.4 (6.4) | 0.05 | 0.015 |

Notes: Data are expressed as number (%) unless otherwise indicated.

We compared the patients with known diagnostic (33 as bacterial, 12 as viral, 2 as mixed viral and bacterial, and 1 as Mycobacterium spp.) and unknown diagnostic.

Abbreviations: AE-COPD, acute chronic obstructive pulmonary disease exacerbation; CRP, C-reactive protein; NAT, nucleic acid amplification test; PaCO2, partial pressure of carbon dioxide; PO2, partial pressure of oxygen; Post-BD FEV1, post-bronchodilator forced expiratory volume in the first second; SatO2, saturated oxygen; SD, standard deviation; U/L, units per litre.

The patients were hospitalized in the following departments: Internal Medicine (48.5%), Pneumology (33.3%), and the Short Stay Unit (18.2%).

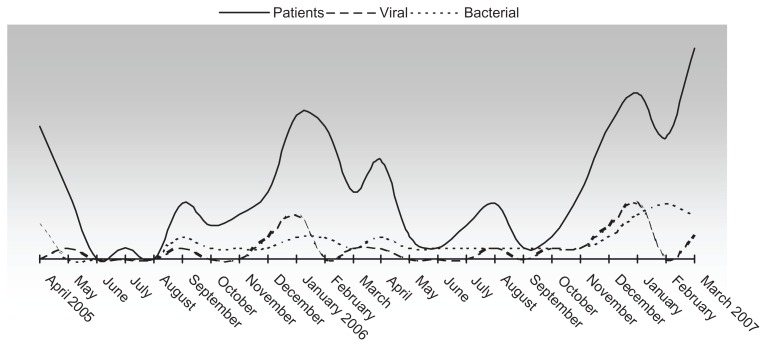

Over the course of two years, the admissions peaks coincided with seasonal variations, exhibiting two annual peaks (spring and winter) (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Patient inclusion and bacterial and viral diagnoses during the study period (April 1, 2005 to March 31, 2007).

Note: The mixed cases included the following pathogens: Chlamydia pneumoniae plus Haemophilus influenzae, Escherichia coli plus influenza A virus, Pseudomonas aeruginosa plus coronavirus, and Streptococcus pneumoniae plus Streptococcus marcescens.

A total of 51 pathogens were isolated. Of these, 37 were bacterial and 14 were viral.

Of the 73 sputum samples surveyed, 19 were Gram-positive, 17 were Gram-negative, and 37 contained polymorphonuclear cells without bacteria. In addition, Ziehl–Neelsen staining was performed in 26 samples, all of which had a negative result. The culture results were positive in 34 patients (Table 2), with higher numbers of patients exhibiting H. influenzae and P. aeruginosa.

Table 2.

Diagnostic test results and yields

| Etiology | Detection method | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

|||||||

| Sputum | Serology | RIT | DFA | Viral culture | NAT | Total detected | |

| Bacterial | |||||||

| Streptococcus pneumoniae | 2 | – | – | – | – | – | 2 |

| Haemophilus influenza | 11 | – | – | – | – | – | 11 |

| Moraxella catarrhalis | 3 | – | – | – | – | – | 3 |

| Pseudomonas aeruginosa | 13 | – | – | – | – | – | 13 |

| Escherichia coli | 3 | – | – | – | – | – | 3 |

| Streptococcus marcescens | 1 | – | – | – | – | – | 1 |

| Mycobacterium spp. | 1 | – | – | – | – | – | 1 |

| Chlamydophila pneumoniae | – | 1 | – | – | – | – | 1 |

| Mycoplasma pneumoniae | – | 2 | – | – | – | – | 2 |

| Viral | |||||||

| Respiratory syncytial virus | – | – | – | 3 | 0 | 2 | 4 |

| Rhinovirus | – | – | – | – | 1 | 1 | 2 |

| Parainfluenza virus | – | – | – | 1 | 1 | 1 | 2 |

| Human metapneumovirus | – | – | – | – | – | 2 | 2 |

| Coronavirus | – | – | – | – | – | 2 | 2 |

| Adenovirus | – | – | – | – | 1 | – | 1 |

| Influenza A virus | – | – | – | 1 | – | – | 1 |

| Total (positive test/total test) | 34/73 | 3/131 | 0/130 | 5/130 | 3/128 | 8/30 | 51 |

Notes: Mixed cases included the following pathogens: Chlamydophila pneumoniae plus Haemophilus influenzae, Escherichia coli plus influenza A virus, Pseudomonas aeruginosa plus coronavirus, Streptococcus pneumoniae plus Streptococcus marcescens.

Abbreviations: DFA, direct fluorescent test; NAT, nucleic acid amplification test; RIT, rapid immunochromatographic test.

We obtained two positive serologies for Mycoplasma pneumoniae (1.5%) and one for Chlamydia pneumoniae (0.8%).

An NPL was collected from all patients to detect a possible viral etiology. We identified a positive result in 14 patients and found herpes virus type-1 in two patients. The detection of herpes virus type-1 was attributed to contamination. So then, we identified a positive result from viral techniques in 12 patients.

An etiological agent was identified in 48 of the patients (36.3%), and an unknown AE-COPD etiology was assigned to 84 patients (63.7%).

A bacterial agent was identified as the etiological agent in 33 patients (24.1%), with mixed bacterial etiology in two patients (S. pneumoniae plus S. marcescens and H. influenzae and C. pneumoniae). We identified a positive result to Mycobacterium spp. by sputum.

A virus was isolated in 12 patients (9%); and two patients exhibited exacerbations attributable to a mixed etiology (1.5%), E. coli plus influenza A virus and P. aeruginosa plus coronavirus.

The efficiencies of the diagnostic tests are shown in Table 2.

We compared the characteristics of the patients using bacterial and viral isolation. When we assessed the clinical and analytical parameters of AE-COPD according to etiological diagnoses, no significant differences were observed, with the exception of the lymphocyte count for the patients whose AE-COPD was attributed to a virus (Table 3).

We obtained statistically significant differences between the analytical datasets for the patients with known and unknown etiologies. In patients with an unknown etiology, we observed a greater decrease in the pH and pO2 in the baseline arterial blood gas upon arrival at the emergency room, as well as a greater leukocytosis and increased heart rate (Table 3).

Evaluation of AE-COPD

The evaluation of AE-COPD after a week of hospital admission revealed clinical improvement in the majority of patients (92.3%). Treatment failure was observed in seven patients (5.4%), and no positive changes were observed in three patients (2.3%). Treatment failure was evidenced by the worsening of respiratory failure in three patients, severe adverse effects in two patients, and a lack of treatment response in four patients.

Only one patient died during hospitalization.

Discussion

This prospective observational study of patients admitted for AE-COPD (VIR-AE) included a 2-year follow-up period and was intended to identify the infectious etiology of COPD exacerbations (whether viral or bacterial), as well as to describe the clinical features and analytical variables used to differentiate the cause of exacerbation.

An infectious cause was identified in 48 of the 132 patients included in this study (36.3%). A bacterial etiology was identified in 33 patients, a viral infection was observed in 12 patients, and two patients had mixed etiology. A higher sensitivity was observed with the conventional sputum analysis and the polymerase chain reaction technique (PCR) for the NPL analysis.

The clinical and laboratory variables that were evaluated for the diagnosis were practically the same for the bacterial and viral etiology cases, with the exception of a relative lymphocyte count that was lower in the group with viral etiology and a longer hospitalization period in patients with bacterial infections. We attributed the longer hospital stay to parenteral treatment after finding multiresistant bacteria in some patients with bacterial etiology.

Other studies have identified clinical symptoms such colds or a sore throat upon the isolation of rhinovirus,8 or even when rhinorrhea was associated with a bacterial etiology.24 However, we have not identified any clinical symptom as indicative of a viral etiology in this study, probably because of the sample size.

We have also identified a greater involvement of baseline arterial blood gas (a decrease in pH and PO2) in the group with an unknown etiology, as well as increased leukocytosis and heart rate, which could mean that a bronchospasm component contributes to the AE-COPD within this group.

In addition to bronchospasm, other causes of AE-COPD such as heart failure or pulmonary thromboembolism were likely to be excluded from our study due to the fact that we only selected a population with a highly suspicious respiratory infection. Similarly, we excluded patients coming from residential centers, patients admitted to the hospital in the 30 days prior to their current admission, and patients transferred from the intensive care unit in order to eliminate any hospital-acquired infections. This comprehensive selection of patients may limit the external validity of our results.

We observed a mean age of 73 years (range 51–88 years) and a smoking history in all of our patients (23.5% were active smokers), which is probably due to the high percentage of men in our study.

The diagnosis of COPD exacerbation is a matter of debate. The most frequent cause of COPD exacerbation is considered to be viral or bacterial bronchial infection.25 This fact is based on the regular presence of purulent coughing and bacterial isolation from the cough of more than half of the patients with exacerbations.26 In addition, up to 30% of patients with stable COPD had evidence of bronchial bacterial colonization in the absence of AE-EPOC.6 However, authors such as Sethi et al have demonstrated that pathogen colonization is not responsible for the exacerbation, as for Haemophilus, where infection with an additional bacterial strain is necessary to elicit an exacerbation.27

The identification of a bacterial etiology for AE-COPD is primarily obtained through the study of sputum. We obtained sputum in 65% of patients, which shows the difficulty of obtaining it in clinical practice. A mixed respiratory flora was obtained in 37% of these patients and was diagnostic in 24.2%, with the samples exhibiting a predominance of H. influenzae and P. aeruginosa. It is important to note that our patients had severe COPD exacerbations that caused respiratory failure and required hospital admission. H. influenzae and P. aeruginosa were detected mainly in the patients with severe COPD, which could explain the inability to isolate bacteria such as Pneumococcus and viruses, as severe COPD benefits the enterobacteria and P. aeruginosa.

The routine use of serology is not useful for the diagnosis of acute Mycoplasma pneumoniae or Chlamydia infection.

From the point of view of viral etiology, PCR techniques have been performed on the bronchial exudate of COPD patients, with a virus being detected in 23% of the exacerbations.28 In our study, the result was lower, as we detected a virus in 10% of all the AE-COPD cases, with little evidence of influenza virus in our sample. This could be explained due to the fact that an influenza epidemic was not identified during the study period.29

The discrepancies between our data and the data from other studies could also be explained by the different samples and techniques used. For example, higher percentage were obtained of sputum samples than NPL samples (47% and 31%, respectively).9 In reference to the literature, we probably could have obtained better results by analyzing the sputum rather than obtaining the NPL for virological diagnostic techniques.

Even so, based on the results obtained, we can state that viral infections could be the cause of AE-COPD. We should have this in mind at the time of prescribing antibiotics, especially in a slightly sick patient who presents no purulent sputum.

Viral disease has a seasonal distribution, and therefore, efforts to confirm the diagnosis in routine clinical practice are to be reserved for situations in which viruses are present in the community; otherwise, this diagnosis could lead to a significant economic cost. Rapid viral antigen detection with immunochromatography tests has a low diagnostic sensitivity, is not very useful, and is too expensive to be used in nonepidemic situations.30

Conclusion

In conclusion, we stress that differentiating the etiology of AE-COPD on the basis of clinical and laboratory data is difficult in common clinical practice.

In our experience, the most profitable diagnostic tests to identify the possible cause of the acute decompensation of a patient with COPD are the conventional sputum test for bacteria and molecular biology techniques for viruses.

Acknowledgments/disclosure

The authors report no conflicts of interest in this work.

This project was funded by a Mataró TV3 Foundation grant (042710).

Our thanks to the Pneumology Department of the Hospital de Mataró for its assistance with this research and Agustí Viladot for the bibliographic revision.

References

- 1.World Health Organization. Burden of COPD. [Accessed November 9, 2011]. Available from: http://www.who.int/respiratory/copd/burden/en/index.html.

- 2.Miravitlles M, Soriano JB, Garcia-Rio F, et al. Prevalence of COPD in Spain: impact of undiagnosed COPD on quality of life and daily life activities. Thorax. 2009;64(10):863–868. doi: 10.1136/thx.2009.115725. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Rodriguez-Roisin R. Toward a consensus def inition for COPD exacerbations. Chest. 2000;117(5 Suppl 2):398S–401S. doi: 10.1378/chest.117.5_suppl_2.398s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Connors AF, Dawson NV, Thomas C, et al. Outcomes following acute exacerbation of severe chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 1996;154(4 Pt 1):959–967. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm.154.4.8887592. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Miravitlles M. Exacerbations of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: when are bacteria important? Eur Respir J Suppl. 2002;36:9s–19s. doi: 10.1183/09031936.02.00400302. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Monso E, Ruiz J, Rosell A, et al. Bacterial infection in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. A study of stable and exacerbated outpatients using the protected specimen brush. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 1995;152(4 Pt 1):1316–1320. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm.152.4.7551388. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Greenberg SB, Allen M, Wilson J, Atmar RL. Respiratory viral infections in adults with and without chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2000;162(1):167–173. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm.162.1.9911019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Seemungal T, Harper-Owen R, Bhowmik A, et al. Respiratory viruses, symptoms, and inflammatory markers in acute exacerbations and stable chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2001;164(9):1618–1623. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm.164.9.2105011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Rohde G, Wiethege A, Borg I, et al. Respiratory viruses in exacerbations of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease requiring hospitalisation: a case-control study. Thorax. 2003;58(1):37–42. doi: 10.1136/thorax.58.1.37. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Papi A, Bellettato CM, Braccioni F, et al. Infections and airway inflammation in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease severe exacerbations. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2006;173(10):1114–1121. doi: 10.1164/rccm.200506-859OC. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Mohan A, Chandra S, Agarwal D, et al. Prevalence of viral infection detected by PCR and RT-PCR in patients with acute exacerbation of COPD: a systematic review. Respirology. 2010;15(3):536–542. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1843.2010.01722.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Peces-Barba G, Barberà JA, Agustí A, et al. Diagnosis and management of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: joint guidelines of the Spanish Society of Pulmonology and Thoracic Surgery (SEPAR) and the Latin American Thoracic Society (ALAT) Arch Bronconeumol. 2008;44(5):271–281. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Saint S, Bent S, Vittinghoff E, Grady D. Antibiotics in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease exacerbations. A meta-analysis. JAMA. 1995;273(12):957–960. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ram FS, Rodriguez-Roisin R, Granados-Navarrete A, et al. Antibiotics for exacerbations of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2006;(2):CD004403. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD004403.pub2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.El Moussaoui R, Roede BM, Speelman P, Bresser P, Prins JM, Bossuyt PM. Short-course antibiotic treatment in acute exacerbations of chronic bronchitis and COPD: a meta-analysis of double-blind studies. Thorax. 2008;63(5):415–422. doi: 10.1136/thx.2007.090613. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Stolz D, Christ-Crain M, Bingisser R, et al. Antibiotic treatment of exacerbations of COPD: a randomized, controlled trial comparing procalcitonin-guidance with standard therapy. Chest. 2007;131(1):9–19. doi: 10.1378/chest.06-1500. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.The Global Initiative for Obstructive Lung Disease home page. [Accessed November 9, 2011]. Available from: http://www.goldcopd.com.

- 18.Anthonisen NR, Manfreda J, Warren CP, Hershfield ES, Harding GK, Nelson NA. Antibiotic therapy in exacerbations of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Ann Intern Med. 1987;106(2):196–204. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-106-2-196. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Servei Català de la Salut. Catàleg de diagnòstics i procediments. [Accessed November 9, 2011]. Available from: http://www10.gencat.net/catsalut/cat/prov_catdiag.htm.

- 20.Ginde AA, Tsai CL, Blanc PG, Camargo CA., Jr Positive predictive value of ICD-9-CM codes to detect acute exacerbation of COPD in the emergency department. Jt Comm J Qual Patient Saf. 2008;34(11):678–680. doi: 10.1016/s1553-7250(08)34086-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Bestall J, Paul E, Garrod R, Garnham R, Jones P, Wedzicha J. Usefulness of the Medical Research Council (MRC) dyspnoea scale as a measure of disability in patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Thorax. 1999;54(7):581–586. doi: 10.1136/thx.54.7.581. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Celli BR, Cote CG, Marin JM, et al. The body-mass index, airflow obstruction, dyspnea, and exercise capacity index in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. N Engl J Med. 2004;350(10):1005–1012. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa021322. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Murray PR, Washington JA. Microscopic and bacteriologic analysis of expectorated sputum. Mayo Clin Proc. 1975;50(6):339–344. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hutchinson AF, Black J, Thompson MA, et al. Identifying viral infections in vaccinated Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease (COPD) patients using clinical features and inflammatory markers. Influenza Other Respi Viruses. 2010;4(1):33–39. doi: 10.1111/j.1750-2659.2009.00113.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Anthonisen NR. Bacteria and exacerbations of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. N Engl J Med. 2002;347(7):526–527. doi: 10.1056/NEJMe020075. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.White AJ, Gompertz S, Stockley RA. Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. 6: the aetiology of exacerbations of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Thorax. 2003;58(1):73–80. doi: 10.1136/thorax.58.1.73. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Sethi S, Evans N, Grant B, Murphy T. New strains of bacteria and exacerbations of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. N Engl J Med. 2002;347(7):465–471. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa012561. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Seemungal TAR, Harper-Owen R, Bhowmik A, Jeffries DJ, Wedzicha JA. Detection of rhinovirus in induced sputum at exacerbation of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Eur Respir J. 2000;16(4):677–683. doi: 10.1034/j.1399-3003.2000.16d19.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.System of influenza surveillance in Spain. [Accessed November 9, 2011]. Available from: http://vgripe.isciii.es/gripe/inicio.do.

- 30.Uyeki TM, Prasad R, Vukotich C, et al. Low sensitivity of rapid diagnostic test for influenza. Clin Infect Dis. 2009;48(9):e89–e92. doi: 10.1086/597828. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]